Abstract

Objectives

Squamous metaplasia is commonly detected in pancreatic parenchyma, however primary pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a rare malignancy with unknown incidence and unclear prognosis.

Methods

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries were examined identifying pancreatic SCC and adenocarcinoma cases from 2000 to 2012. Age-adjusted incidence rates were calculated. Patients with SCC versus adenocarcinoma were compared by clinical features and relative survival outcomes.

Results

We identified 214 patients with SCC and 72,860 with adenocarcinoma. For SCC, incidence rates tripled between 2000 and 2012. Significantly higher SCC incidence rates were observed in older age groups, blacks and males. Greater proportion of patients with SCC than adenocarcinoma had poorly differentiated histology (73.0% versus 43.7%, p<0.001). In both subtypes, majority of patients had stage IV disease, 59.0% for adenocarcinoma versus 62.6% SCC. The 1-year and 2-year relative survival rate was significantly lower in patients with SCC versus adenocarcinoma. The 1-year relative survival was 14.0% (95% confidence interval (CI) =9.5-19.4) for SCC, compared with 24.5% (95%CI=24.2-24.8) for adenocarcinoma.

Conclusions

Although primary pancreatic SCC is a rare neoplasm, incidence rates for this subtype are increasing. Relative to adenocarcinoma, pancreatic SCC is characterized by poorly differentiated histology and worse survival.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma, pancreas, carcinoma, squamous cancer, squamous metaplasia

Introduction

Although the pancreas is an organ without squamous cell differentiation in its normal state, parenchymal squamous metaplasia is commonly detected in pancreatic specimens. During autopsy studies squamous metaplasia is observed in 17-48% of cases.1,2 and its presence in biopsies is associated with chronic pancreatitis3 and pancreatic duct stent placement.4 Despite the relatively high frequency of squamous metaplasia, pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a rare primary pancreatic malignancy. The available published data on squamous subtype of pancreatic cancer is very limited, mostly presented as individual case reports or small case series studies.5-11 As a result, the epidemiology and clinical course of pure squamous cell pancreatic carcinoma remains poorly understood.

In the gastrointestinal tract, squamous carcinomas are commonly diagnosed in the esophagus and anal canal, where squamous epithelium is normally present. How primary squamous cancer develops in organs without squamous epithelium is unknown, but possibilities include development from a progenitor cell, squamous transformation of adenocarcinoma or malignant transformation of squamous metaplasia.12 Published studies of squamous carcinoma patterns in colorectum,13 prostate14,15 and breast,16 which are all organs without squamous cells in their normal physiologic state, reported a poor prognosis for squamous histologic subtype. In previous case series of patients with primary pancreatic malignancies squamous cell carcinoma denoted poor survival outcomes.9,11 No comparison group was used in these analyses however, and, thus, more information is needed to determine whether squamous pancreatic cancer has a more aggressive clinical course compared to classical pancreatic adenocarcinoma (AC).

The studies on pancreatic cancer epidemiology report an increased risk of pancreatic cancer with black race,17 males18 and older age.18 These findings mainly apply to pancreatic adenocarcinoma which accounts for approximately 90% of all primary pancreatic malignancies.19 It is assumed, but not established, that squamous cell carcinoma follows similar epidemiological patterns as adenocarcinoma.

We hypothesize that squamous histology of pancreatic cancer has similar epidemiological features to adenocarcinoma but has more aggressive clinicopathologic characteristics and inferior survival. Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, we conducted an analysis to determine epidemiological characteristics of pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma relative to adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, to clarify a clinical course of squamous carcinoma, we compared clinical features and survival of patients with squamous pancreatic cancer to those with classical pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Methods

Data source

Data for this study were obtained from SEER research database available online from the National Cancer Institute. Information included in the SEER database is collected by review of medical records with standard for case ascertainment rate set at 98% for new cancer cases. The SEER 18 registries identify new cancer cases diagnosed within 18 geographic regions in 14 states covering approximately 28% of the US population and include the Atlanta, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, San Francisco-Oakland, Seattle-Puget Sound, Utah, Los Angeles, San Jose and Monterrey, Rural Georgia, the Alaska Native Tumor Registry, Greater California, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, and Greater Georgia. Because of the impact hurricane Katrina had on Louisiana’s population from July to December 2005, SEER excluded Louisiana patients diagnosed for that time interval. Furthermore, the population included in the SEER-18 database is adjusted population for the shifts due to hurricanes Katrina/Rita for 62 counties in Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi and Texas.

Study cases

Cancer types were coded according to the International Classification of Disease-Oncology (ICD-O), third edition. Topography code C25 (pancreas) was used to identify primary pancreatic cancer cases from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2012. Patients with reported diagnose source from autopsy or death certificate were excluded. Only patients with histologically confirmed disease were included in our study. Morphology codes (ICD9-0-3) used were squamous cell carcinoma (8052-8053, 8070-8078, 8083-8084), and adenocarcinoma20 (8140, 8141, 8143, 8211 and 8480–8481). Patients with mixed adenosquamous histology were excluded from our analysis. The detailed description of ICD9-0-3 histology codes included in this study is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical Methods

1) Incidence rates per 100,000 age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population with corresponding rate ratio 95% CIs21 were calculated by using SEER*Stat for squamous carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the pancreas diagnosed from 2000 to 2012 for all patients as well as by demographic characteristics including race (White, Black), ethnicity (North American Association of Central Cancer Registries Hispanic Identification Algorithm (NHIA) defined Non- Hispanics and Hispanics) and age (under 40, 40-64, 65+). The annual percent change (APC) was analyzed from 2000 to 201222 and percent change was calculated between 2000 and 2012. 2) We compared patients with squamous carcinoma to those with adenocarcinoma of pancreas by location of primary tumor (head and body/tail), stage of disease based on American Joint Committee on Cancer 6th edition (AJCC6)-derived classification (I, II, III, IV), by tumor (T1-T2 and T2-T3), nodal (N1 and N0) and distant metastases (M1 and M0), extent of disease (locoregional and distant metastatic) and by histologic grade (good/moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated and anaplastic). Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. The 1-year and 2-year relative survival rates and their corresponding 95% CI were estimated using Kaplan-Meir method, observed survival curves was compared using logrank test, 1- and 2-year relative survival were compared using Z-test23 with corresponding p values. Significance was set at 0.05. The statistical system SEER*Stat version 8.2.1 and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jollla, Calif) was used to conduct these analyses.

Results

We identified 217 cases of primary pancreatic SCC and 75,759 cases of pancreatic AC diagnosed between 2000 and 2010 in the SEER 18 registries database. Of these 98.6% (214) with SCC and 96.4% (73,013) with pancreatic AC were histologically confirmed. Patients with a death certificate or autopsy as a diagnostic source were excluded from our study (153 patients with AC and 0 patients with SCC). Consequently, our case selection resulted in analysis of total of 214 patients with primary pancreatic SCC and 72,860 patients with AC.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the study population and incidence rates by histologic type of carcinoma are listed in Table 1. Most cases with SCC (63.1 %) were diagnosed in patients 65 years and older, similar to 63.5 % of AC cases. In both groups, majority of patients were males, whites, non-Hispanics, and residing in metropolitan areas. The age-adjusted incidence rates for pancreatic SCC was substantially lower than AC, 0.02 per 100, 000 for SCC (95% CI, 0.018 −0.024) compared to 6.9 per 100,000 for AC (95% CI, 6.85-6.95), p<0.0001.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and incidence rates by histological subtype of primary pancreatic cancer: squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

Adenocarcinoma |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| % Pancreatic cancers | 0.2 | 73.3 | ||

|

| ||||

| Total Patients | 214 | 100.0 | 72,860 | 100.0 |

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 68.1 | 13.0 | 68.4 | 11.7 |

| Age groups | ||||

| < 40 | 4 | 1.9 | 616 | 0.8 |

| 40-64 | 75 | 35.0 | 25,969 | 35.6 |

| ≥ 65 | 135 | 63.1 | 46,275 | 63.5 |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 121 | 56.5 | 37,441 | 51.4 |

| Female | 93 | 43.5 | 35,419 | 48.6 |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White | 157 | 73.4 | 58,885 | 80.8 |

| Black | 32 | 15.0 | 8,823 | 12.1 |

| Other/Unknown | 25 | 11.7 | 5,152 | 7.1% |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 203 | 94.9 | 66,132 | 90.8 |

| Hispanic | 11 | 5.1 | 6,728 | 9.2 |

|

| ||||

| Residence | ||||

| Metropolitan | 187 | 87.4 | 64,112 | 88.0 |

| Urban | 23 | 10.7 | 7,613 | 10.4 |

| Rural | 4 | 1.9 | 1,043 | 1.4 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0 | 92 | 0.1 |

|

| ||||

| Incidence rates1 | ||||

| Overall, (95% CI) | 0.02 | 0.02-0.02 | 6.90 | 6.85-6.95 |

Age-adjusted incidence rates per 100,000

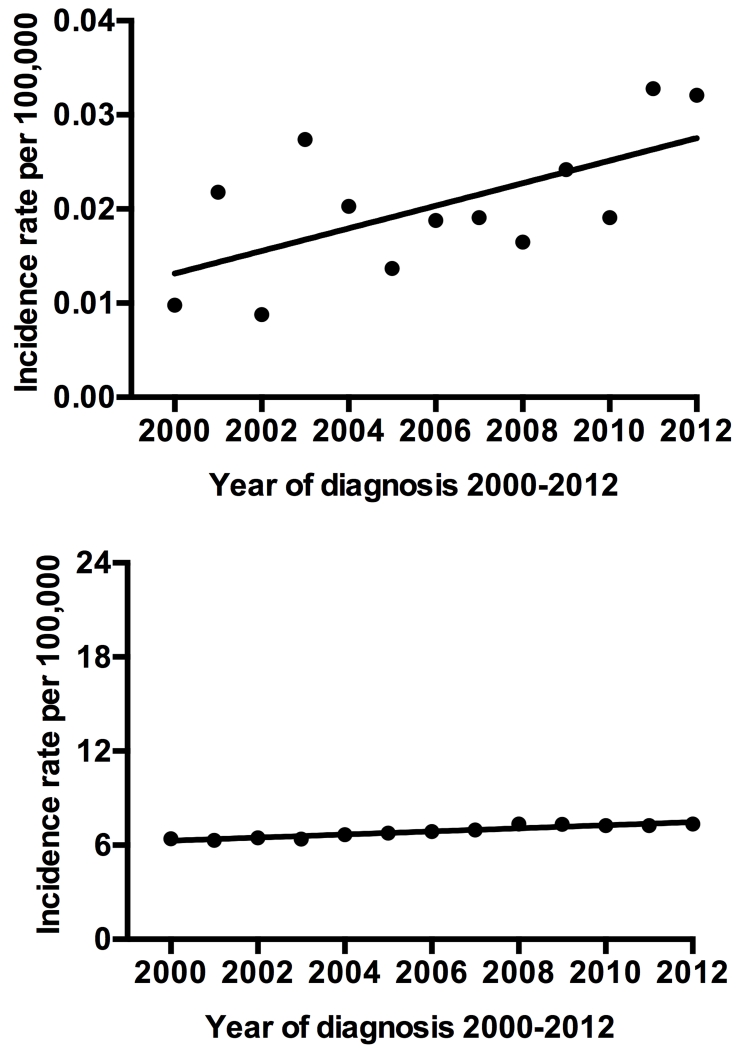

Over time, the incidence rates for SCC varied but with a significantly overall increasing trend (Figure1a). The incidence percent increase for SCC was 228.7% between 2000 and 2012 and annual percent increase was of 5.5% (95% CI, 0.5 −10.7, p=0.03). In the same time frame, AC percent increase was only 14.9% and annual percent increase was 1.4% (95% CI, 1.1-1.8, p<0.001) (Figure1b). Similarly to AC, the incidence rate for primary pancreatic SCC differed by gender, race and ethnicity (Table 2). There was a significant increase in the age-adjusted incidence rate in men relative to women: RR=1.6 (95% CI, 1.2-2.2) for SCC and RR= 1.3 (95% CI, 1.3 −1.3) for AC, p< 0.001. When analyzed by race, the age-adjusted incidence rates of SCC and AC were higher in blacks relative to whites: RR=1.7 (95% CI, 1.1-2.5, p=0.013) for SCC and RR=1.3 (95% CI, 1.3-1.3, p<0.001) for AC. Furthermore, in both histological subtypes increased risk was observed for older age groups. For SCC, 65 years and older patients had RR of 141.1 relative to people under 40 and 5.1 when compared to age group 40-64, p <0.001.

Figure 1.

a) Age-adjusted incidence rates for primary pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma by year of diagnosis from 2000 to 2012. b) Age-adjusted incidence rates for pancreatic adenocarcinoma by year of diagnosis from 2000 to 2012.

Table 2.

Incidence rates and rate ratios of patients with primary pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma by age (under 40, 40-64, 65+), sex, race and ethnicity.

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate per 100,000 | RR (95% CI) | P | Rate per 100,000 | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age groups | ||||||

| <40 (ref) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) | 0.11 (0.10-0.12) | ||||

| 40 -64 | 0.02 (0.02-0.03) | 27.46 (10.59-103.45) | <0.001 | 7.08 (7.00-7.17) | 65.08 (60.07-70.62) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 65 | 0.11 (0.09-0.13) | 141.06 (55.39-525.22) | <0.001 | 37.08 (36.74- 37.42) |

340.60 (314.55-369.44) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female (ref) | 0.02 (0.01-0.02) | 6.05 (5.99-6.12) | ||||

| Male | 0.03 (0.02-0.03) | 1.63 (1.23-2.17) | <0.001 | 7.94 (7.86-8.03) | 1.31 (1.29-1.33) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White (ref) | 0.02 (0.02-0.02) | 6.84(6.79-6.90) | ||||

| Black | 0.03 (0.02-0.05) | 1.72 (1.12-2.53) | 0.01 | 8.94(8.75-9.13) | 1.31 (1.28-1.34) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic (ref) | 0.02 (0.02-0.03) | 6.99(6.94-7.05) | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | 0.43 (0.20-0.79) | 0.004 | 6.24 (6.08-6.40) | 0.89 (0.87-0.92) | <0.001 |

Ref indicates reference

Next we compared clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with SCC and AC (Table 3). As compared to AC a greater proportion of patients with SCC had poorly differentiated histology, 30.4 vs. 15.8, p<0.001, however for majority of patients (64.0% AC and 58.4% SCC) differentiation pattern was not recorded. Among patients with known histological differentiation, the percentage of poorly differentiated histology was 73.0% for SCC vs. 43.7% for AC and well/moderately differentiated was 23.6% for SCC and 54.6% for AC, p<0.001. AJCC6 stage was recorded for 90.2 % patients with SCC (N=147) and 92.0% with AC (N=49,537) diagnosed between 2004 and 2012. In contrast to histological differentiation, no significant difference was detected in stage of tumor between SCC and AC. The majority patients with SCC as well as AC presented with distant metastatic disease. Among patients with known disease stage, stage IV was diagnosed in 62.6% SCC and 59.0% AC, locally advanced disease (stage III) constituted approximately 10% of each histological subtype, stage II disease was in 21.1% of SCC patients and 24.9% of those with AC, and node negative tumors confined to pancreas (stage I) were diagnosed in minority of patients with each subtype, only in 4.8% SCC and 5.9% AC cases. Furthermore, no statistically significant difference was observed for tumor location in pancreas between patients with SCC and AC; our analysis showed that patients with both histological subtypes were most frequently diagnosed with tumors located in the pancreatic head rather than pancreatic body or tail.

Table 3.

Tumor characteristics for patients with squamous carcinoma relative to patients with classical adenocarcinoma of pancreas.

| Tumor characteristics | Squamous cell carcinoma |

Adenocarcinoma | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Differentiation | |||||

|

| |||||

| Well/moderately differentiated | 21 | 9.8 | 14,339 | 19.7 | <0.001 |

| Poorly differentiated | 65 | 30.4 | 11,488 | 15.8 | |

| Anaplastic | 3 | 1.4 | 434 | 0.6 | |

| Unknown | 125 | 58.4 | 46,599 | 64.0 | |

|

| |||||

| Primary tumor location | |||||

|

| |||||

| Head of pancreas | 102 | 47.7 | 36,674 | 50.3 | 0.48 |

| Body/Tail of pancreas | 58 | 27.1 | 17,191 | 23.6 | |

| Unknown | 54 | 25.2 | 18,995 | 26.1 | |

|

| |||||

| Extent of disease | |||||

|

| |||||

| Locoregional | 70 | 32.7 | 27,145 | 37.3 | 0.33 |

| Distant | 132 | 61.7 | 42,450 | 58.3 | |

| Unknown | 12 | 5.6 | 3,265 | 4.5 | |

|

| |||||

| Stage1, 2004+ | |||||

|

| |||||

| I | 7 | 4.3 | 2,903 | 5.4 | 0.66 |

| II | 31 | 19.0 | 12,336 | 22.9 | |

| III | 17 | 10.4 | 5,070 | 9.4 | |

| IV | 92 | 56.4 | 29,228 | 54.3 | |

| Unknown | 16 | 9.8 | 4,314 | 8.0 | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor1, 2004+ | |||||

|

| |||||

| T0-Tis | 0 | 0.0 | 408 | 0.8 | 0.42 |

| T1-T2 | 29 | 17.8 | 10,833 | 20.1 | |

| T3-T4 | 99 | 60.7 | 29,874 | 55.5 | |

| TX | 35 | 21.5 | 12,736 | 23.7 | |

|

| |||||

| Lymph node status1, 2004+ | |||||

|

| |||||

| N0 | 66 | 40.5 | 25,867 | 48.0 | 0.06 |

| N1 | 64 | 39.3 | 16,631 | 30.9 | |

| NX | 33 | 20.2 | 11,353 | 21.1 | |

|

| |||||

| Distant metastases1, 2004+ | |||||

|

| |||||

| M0 | 58 | 35.6 | 21,906 | 40.7 | 0.14 |

| M1 | 92 | 56.4 | 29,228 | 54.3 | |

| MX | 13 | 8.0 | 2,717 | 5.0 | |

Total 163 patients with SCC and 53,851 with ACC diagnosed 2004+ were included in AJCC6 –derived stage and TNM analysis

Bold value are statistically significant.

The vast majority of patients with both histological subtypes were managed with palliative intent. Only a small percentage of patients with SCC (10.3%, N=22) and AC (14.2%, N=10,353) received potentially curative surgery. The observed overall survival was significantly lower in patients with SCC compared AC in the overall study population, and in those managed with palliative care, but the difference was not statistically significant in surgical patients (Figure 2). Survival adjusted for age, race, sex, and date such as relative survival was in concordance with observed survival. In the overall study population, the 1-year and 2-years relative survival rates were significantly shorter in patients with SCC relative to AC (Table 4). For an example, 1-year survival was 14.0% (95%CI 9.5-19.4) for patients with SCC vs 24.5% (95%CI 24.2-24.8) for AC, p<0.001. The receipt of surgery substantially improved relative survival in both groups. Analysis of surgical patients showed that the disparity in survival between SCC and AC was evident at 1 year, but no statistically significant difference was observed for 2-year survival. The 1-year RS was 63.9% for surgical patients with AC (95% CI 62.9-64.9) vs. 45.3% for patients with SCC (95%CI 23.6-64.9), p=0.03. A small number of patients at risk (N=6 patient alive) was observed for surgically treated patients with SCC at the 2 year time point and difference in survival 35.2% for SCC and 37.2 for AC was not significant, p=0.28. For patients managed with palliative intent 1-year RS was 17.9% (95%CI 17.6-18.2) for AC and 10.3% (95%CI 6.2-15.4) for SCC, p<0.001 and statistically significant inferior survival for SCC was also observed at 2 years. Out of all 214 patients with SCC 91.6% (196) had traced record of vital status, 9 patients were reported to be alive at 3 years and only 1 patient with SCC treated with surgery was at risk at the 5 year time point.

Figure 2.

Observed survival primary pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma compared to pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a) overall study population b) patients treated with palliative intent c) patients treated with surgery

Table 4.

Median, 1 -year and 2-year relative survival of patients with pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma compared to classical pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

| Relative Survival | Squamous cell carcinoma |

Adenocarcinoma | Z-score | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median, months | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overall | 4 | 6 | ||

| Palliative cohort | 3 | 5 | ||

| Surgical cohort | 10 | 18 | ||

|

| ||||

| 1-year, % (95%CI) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overall | 14.0 (9.5-19.4) | 24.5 (24.2-24.8) | 4.888 | <0.001 |

| Palliative cohort | 10.3 (6.2-15.4) | 17.9 (17.6-18.2) | 4.050 | <0.001 |

| Surgical cohort | 45.3 (23.6-64.9) | 63.9 (62.9 -64.9) | 2.196 | 0.028 |

|

| ||||

| 2-year, % (95%CI) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overall | 7.0 (3.8-11.5) | 9.8 (9.5-10.0) | 4.367 | <0.001 |

| Palliative cohort | 3.7 (1.4-7.6) | 5.1 (4.9-5.3) | 3.801 | <0.001 |

| Surgical cohort | 35.2 (15.0-56.3) | 37.2 (36.2-38.3) | 1.076 | 0.282 |

Discussion

In general, the term pancreatic cancer is used interchangeably with and reflective of a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma, the most common histologic subtype of primary pancreatic malignancies. Less common subtypes include neuroendocrine and acinar neoplasms, which have a different prognosis and management. The presence of primary pancreatic squamous carcinoma was first described by Lowry et.al in 194924 , however the implications in terms of incidence and prognosis of squamous histology are still unknown. We report an apparent rising incidence of squamous pancreatic carcinoma, rare subtype of pancreatic cancer. Our study found that, similarly to classical pancreatic adenocarcinoma, males, blacks and older age groups had increased incidence of primary squamous pancreatic cancer. As compared to pancreatic adenocarcinoma we found that patients with squamous cell pancreatic cancer are characterized by higher proportion of poorly differentiated histology and inferior survival.

Our study is the first population-based study to report epidemiology of primary pancreatic SCC. Although the age-adjusted incidence rates of SCC remained low relative to AC, our study showed that SCC incidence has significantly increased with an annual percent increase of 5.5% from 2000 to 2012. As expected, our analysis showed a slow increase in incidence for AC (1.4%), the finding is consistent with nationwide reports25,26 . For an example, the most recent data published by National Cancer Institute SEER cancer statistic reports a small annual increase for pancreatic cancer by 0.8% from 2002 to 201226. For pancreatic cancer control, targeting the pancreatic cancer risk factors may be of benefit as part of a multi-level strategy. The previous studies of pancreatic cancer evolution associated chronic inflammatory states27,28 such as chronic pancreatitis29 with increased risk for this tumor type. Risk factors for primary SCC are unknown, but detection of squamous metaplasia in patients with chronic pancreatitis3 and after pancreatic stent placement4 suggest that chronic inflammation can increase risk for SCC subtype. In view of these facts, the research focusing on prevention or suppression of chronic inflammatory response in pancreatic parenchyma can have a positive effect on SCC as well as AC incidence. Additionally, our study showed that, similar to AC, males, blacks and older age are at higher risk for SCC; thus, strategies for pancreatic cancer prevention can be tailored to take in account these vulnerable groups.

The analysis of clinicopathologic characteristics of SCC in comparison to AC showed differences in histological differentiation, but not in tumor stage at diagnosis. Our study reports that approximately two-thirds of SCC patients with known differentiation pattern had poorly differentiated tumors. In contrast to this finding, the majority of patients with primary pancreatic AC had well or moderately differentiated neoplasms. In view of poorly differentiated pattern of SCC and rarity of primary pancreatic SCC, a thorough evaluation is required to rule out metastatic disease from another primary site9,12 prior to declaring primary squamous cell pancreatic cancer as the diagnosis. With respect to tumor stage, our study found that the majority of patients with both histologic subtypes of primary pancreatic cancer had T3-T4 tumors and stage IV disease on initial presentation. This is perhaps not surprising given that pancreatic cancer as an entity tends to present at an advanced stage, for a number of reasons, including the absence of established screening methods, anatomical reasons and the aggressive natural course of pancreatic cancer resulting in rapid disease progression from early to advanced stages. Rapid pancreatic cancer progression was reported in a recently published study estimating 1.3 years difference between patients with stage I and stage IV pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma30. Therefore, screening modalities directed on identification of pancreatic cancer precursor lesions or very small tumors are needed to shift the diagnostic patterns toward early, potentially curative disease. The new methods evaluated for pancreatic cancer screening include detection of mutant tumor protein p53 (TP53) in pancreatic juice samples31, detection of circulating tumor DNA32 and incorporation of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) as a screening modality in high risk population33.

The previous population-based studies for patients with adenosquamous pancreatic cancer reported inconsistent survival outcomes and prognosis34,35. Our study excluded mixed adenosquamous histological subtype resulting in a more homogeneous study population of patients diagnosed with pure squamous histology. In absence of population-based studies for SCC the evidence for SCC survival comes from case series reports9,11,36-39. The case series studies for patients with SCC reported median survival of 3 months38 in patients treated with palliative intent and survival of 7 months9 in patients who received potentially curative surgery. In agreement with these case series studies, our population-based analysis showed a median observed survival of 3 months in patients treated with palliative intent and median observed survival of 9 months in patients treated with surgery. Furthermore, we showed that observed and relative survival was significantly worse in patients with SCC than AC in the overall study population and in the subgroup treated with palliative intent. For patients managed with surgery only, relative survival at 1 year was statistical significant, however, the comparison was limited by small number of patients in the surgical subgroup (N=22). Our observation that patients with SCC had inferior overall and relative survival compared to AC has implications for our effort at treating squamous cell pancreatic cancer with novel experimental therapies and radiation.

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis is based on routinely captured SEER cancer registries data, without individual chart review to confirm the pathologic diagnosis, although, we included only patients with histologically confirmed diagnoses. Second, there is potential for misclassification of primary site of origin during reporting or misdiagnosis of SCC as pancreatic primary when in fact it is metastatic disease from head/neck or esophageal cancer. Third, in our analysis of incidence, possible variations in data recording and migration of patients out of SEER Registry areas should be taking in account. Furthermore, this study did not control for lifestyle habits or environmental risk factors which can impact cancer incidence rates.

Despite these limitations, our findings are important, particularly as prior studies consisted of review of literature, case-series reports with limited sample size, no control group, and absent epidemiological data. Conversely, this study is the largest study to date that reports incidence data for SCC as well as clinicopathologic characteristics and survival analysis. To account for deaths secondary to unknown comorbid conditions, we used relative survival, which is a survival measure estimating cancer survival in the absence of other causes of death, in addition to observed survival.

In conclusion, our study we define epidemiology of squamous pancreatic cancer; a rare cancer with rising incidence and increased risk for males, blacks and with older age. Our results showed that squamous pancreatic cancer has epidemiological features similar to classical adenocarcinoma suggesting the common risk factors for these diseases. The devastating finding that majority of patients with both histological subtypes were diagnosed with stage IV disease indicate the urgent need for new screening modalities. Relative to pancreatic adenocarcinoma, patients with pancreatic squamous cancer appear to have a worse survival; and, thus, the role of novel therapies needs to be explored.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mukada T, Yamada S. Dysplasia and carcinoma in situ of the exocrine pancreas. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1982;137:115–124. doi: 10.1620/tjem.137.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pour PM, Sayed S, Sayed G. Hyperplastic, preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions found in 83 human pancreases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982;77:137–152. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/77.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cylwik B, Nowak HF, Puchalski Z, et al. Epithelial anomalies in chronic pancreatitis as a risk factor of pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:528–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Layfield LJ, Cramer H, Madden J, et al. Atypical squamous epithelium in cytologic specimens from the pancreas: cytological differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25:38–42. doi: 10.1002/dc.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colarian J, Fowler D, Schor J, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with cystic degeneration. South Med J. 2000;93:821–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brayko CM, Doll DC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas associated with hypercalcemia. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:1297–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bringel RW, Souza CP, Araujo SE, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with gastric metastasis. Case report. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 1996;51:195–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bralet MP, Terris B, Bregeaud L, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma and lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:569–572. doi: 10.1007/s004280050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown HA, Dotto J, Robert M, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:915–919. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000180636.74387.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raghavapuram S, Vaid A, Rego RF. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Pancreas: Mystery and Facts. J Ark Med Soc. 2015;112:42–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben Kridis W, Khanfir A, Toumi N, et al. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2015;54:1357–1359. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bixler HA, Castro MJ, Stewart J., 3rd Cytologic differentiation of squamous elements in the pancreas. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:536–539. doi: 10.1002/dc.21479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozuner G, Aytac E, Gorgun E, et al. Colorectal squamous cell carcinoma: a rare tumor with poor prognosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:127–130. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malik RD, Dakwar G, Hardee ME, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate. Rev Urol. 2011;13:56–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parwani AV, Kronz JD, Genega EM, et al. Prostate carcinoma with squamous differentiation: an analysis of 33 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:651–657. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200405000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennessy BT, Krishnamurthy S, Giordano S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7827–7835. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.9589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman DT, Hoover RN, Brown LM, et al. Why do Black Americans have a higher risk of pancreatic cancer than White Americans? Epidemiology. 2003;14:45–54. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200301000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Epidemiology and prevention of pancreatic cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:238–244. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cascinu S, Jelic S. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl 4):37–40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ngamruengphong S, Swanson KM, Shah ND, et al. Preoperative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration does not impair survival of patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2015;64:1105–1110. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15:547–569. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown CC. The statistical comparison of relative survival rates. Biometrics. 1983;39:941–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowry CC, Whitaker HW, Jr., Greiner DJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. South Med J. 1949;42:753–757. doi: 10.1097/00007611-194909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Pancreas Cancer [database online] National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2015. Updated October 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrow B, Evers BM. Inflammation and the development of pancreatic cancer. Surg Oncol. 2002;10:153–169. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(02)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jura N, Archer H, Bar-Sagi D. Chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic adenocarcinoma and the black box in-between. Cell Res. 2005;15:72–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. International Pancreatitis Study Group Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J, Blackford AL, Dal Molin M, et al. Time to progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma from low-to-high tumour stages. Gut. 2015;64:1783–1789. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanda M, Sadakari Y, Borges M, et al. Mutant TP53 in duodenal samples of pancreatic juice from patients with pancreatic cancer or high-grade dysplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:719–730. e715. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra224. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brune K, Abe T, Canto M, et al. Multifocal neoplastic precursor lesions associated with lobular atrophy of the pancreas in patients having a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1067–1076. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd CA, Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, et al. 415 patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas: a population-based analysis of prognosis and survival. J Surg Res. 2012;174:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz MHG, Taylor TH, Al-Refaie WB, et al. Adenosquamous Versus Adenocarcinoma of the Pancreas: A Population-Based Outcomes Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1378-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beyer KL, Marshall JB, Metzler MH, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Report of an unusual case and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:312–318. doi: 10.1007/BF01308190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anagnostopoulos GK, Aithal GP, Ragunath K, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: report of a case and review of the literature. JOP. 2006;7:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kodavatiganti R, Campbell F, Hashmi A, et al. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:295. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas D, Shah N, Shaaban H, et al. An interesting clinical entity of squamous cell cancer of the pancreas with liver and bone metastases: a case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2014;45(Suppl 1):88–90. doi: 10.1007/s12029-013-9560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.