Significance

Most genetic studies and clinical genetic testing do not look for the possibility of mosaic variation. The genetic form of long-QT syndrome (LQTS) can result in life-threatening arrhythmias, but 30% of patients do not have a genetic diagnosis. We performed deep characterization of a mosaic variant in an infant with perinatal LQTS and developed a computational model showing how abnormal cellular repolarization in only 8% of heart cells may cause arrhythmia. Finally we looked at the prevalence of mosaicism among patients with LQTS; in a population of 7,500 individuals we found evidence of pathogenic early somatic mosaicism in approximately 0.17% of LQTS patients without a genetic diagnosis. Together these data establish an unreported mechanism for LQTS and other genetic arrhythmias.

Keywords: mosaicism, arrhythmia, genomics, computational modeling, single cell

Abstract

Somatic mosaicism, the occurrence and propagation of genetic variation in cell lineages after fertilization, is increasingly recognized to play a causal role in a variety of human diseases. We investigated the case of life-threatening arrhythmia in a 10-day-old infant with long QT syndrome (LQTS). Rapid genome sequencing suggested a variant in the sodium channel NaV1.5 encoded by SCN5A, NM_000335:c.5284G > T predicting p.(V1762L), but read depth was insufficient to be diagnostic. Exome sequencing of the trio confirmed read ratios inconsistent with Mendelian inheritance only in the proband. Genotyping of single circulating leukocytes demonstrated the mutation in the genomes of 8% of patient cells, and RNA sequencing of cardiac tissue from the infant confirmed the expression of the mutant allele at mosaic ratios. Heterologous expression of the mutant channel revealed significantly delayed sodium current with a dominant negative effect. To investigate the mechanism by which mosaicism might cause arrhythmia, we built a finite element simulation model incorporating Purkinje fiber activation. This model confirmed the pathogenic consequences of cardiac cellular mosaicism and, under the presenting conditions of this case, recapitulated 2:1 AV block and arrhythmia. To investigate the extent to which mosaicism might explain undiagnosed arrhythmia, we studied 7,500 affected probands undergoing commercial gene-panel testing. Four individuals with pathogenic variants arising from early somatic mutation events were found. Here we establish cardiac mosaicism as a causal mechanism for LQTS and present methods by which the general phenomenon, likely to be relevant for all genetic diseases, can be detected through single-cell analysis and next-generation sequencing.

There is growing recognition that somatic mosaicism, i.e., genetic variation within an individual that arises from errors in DNA replication during early development, may play a role in a variety of human diseases other than cancer (1). However, the extent to which cellular heterogeneity contributes to disease is minimally understood. One report suggests that 6.5% of de novo mutations presumed to be germline in origin may instead have arisen from postzygotic mosaic mutation events (2), and recent genetic investigations directly interrogating diseased tissues in brain malformations, breast cancer, and atrial fibrillation have revealed postzygotic causal mutations absent from germline DNA (3–6). Pathogenic mosaic structural variation is also detectable in children with neurodevelopmental disorders (7). However, a consequential category of genetic variation has not been surveyed systematically in clinical or research studies of other human diseases.

The pathophysiological basis of long-QT syndrome (LQTS) is prolongation of cardiac ventricular repolarization by acquired factors such as drug exposure or genetic variation in the proteins controlling transmembrane ion-concentration gradients (8, 9); parental gonadal mosaicism is an infrequently described phenomenon in LQTS (10–12). Knowledge of the molecular subtyping of disease in LQTS has provided a foundation for genotype-specific risk stratification and treatment strategies (8, 9, 13, 14). However, nearly 30% of probands remain undiagnosed using standard commercial gene-panel testing, suggesting there is unrecognized genetic variation (genic, regulatory, or otherwise) yet to be associated with disease (15).

In its most severe form, LQTS may occur in the neonatal period with bradycardia and functional 2:1 AV block that occur secondary to a severely prolonged ventricular refractory period greater than the short R–R interval characteristic of a normal heart rate in infancy (16). Patients of all ages presenting with LQTS are predisposed to torsades de pointes (TdP), a life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia, with patients presenting in infancy showing particularly poor outcomes (13, 16–18). In this study, we applied rapid-turnaround whole-genome sequencing (WGS) on day of life (DOL) 3 in a premature infant with perinatal LQTS and life-threatening arrhythmia and investigated the contribution of a discovered mosaic variant to abnormal cardiac electrophysiology at the molecular and tissue levels. Additionally we surveyed 7,500 individuals already tested for genetic arrhythmias, allowing us to estimate the prevalence of mosaicism in an unbiased population sample.

Results

Deep Sequencing Identifies Mosaic Variation in SCN5A in an Infant with a Prolonged QT Interval and Arrhythmia.

A near-term 2.5-kg female infant of Asian ancestry with prenatally diagnosed 2:1 AV block was delivered by caesarean section at 36-wk gestation. At 1 h of life the infant developed intermittent 2:1 AV block with multiple episodes of TdP with a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 542 ms (Fig. 1), which were relieved by placement of a dual-chamber epicardial implantable cardioverter/defibrillator (ICD) accompanied by a bilateral stellate ganglionectomy. A standard commercially available genetic panel for LQTS was sent on DOL 1 (13, 17), and WGS was performed on DOL 3. At 6 mo of age the patient developed dilated cardiomyopathy and subsequently received an orthotopic heart transplant.

Fig. 1.

Representative electrocardiograms from DOL 1 show a prolonged QT interval and 2:1 atrioventricular block. (A) A rhythm strip from lead II of a 12-lead ECG before treatment shows a prolonged QTc of 542 ms estimated by Bazett’s formula. (B) A rhythm strip showing 2:1 atrioventricular block secondary to prolongation of the QT interval. (C) A rhythm strip demonstrating polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

WGS yielded a 39.76 mean read depth, and coverage across the coding regions of known LQTS and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) genes was 99.93% at 10× or greater (Table S1). The rapid RTG pipeline detected a mutation in the 28th exon of the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.5 encoded by SCN5A NM_000335: c.5284G > T, which predicts p.(V1762L) within the alpha subunit of NaV1.5, which was not present in the two additional call sets originating from Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA)/Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) or Issac (Issac Genome Alignment Software and Variant Caller) pipelines. All three pipelines detected rs41261344, a polymorphism in SCN5A common in Han Chinese NM_000335: c.3575G > A, which predicts p.R1193Q (22).

Table S1.

Sequencing coverage across DCM and LQTS genes for the WGS and Personalis exome sequencing suggests adequate depth to call all coding variants

| Included sequence | % bases <20× | % bases <10× | Minimum read depth (bases) | |

| 23 DCM genes | ||||

| WGS | One transcript, all exons | 1.130 | 0.030 | 9 |

| Personalis exome | One transcript, all exons | 0.840 | 0.230 | 0 |

| Personalis exome | All transcripts, CDS only | 0.170 | 0.070 | 0 |

| Intersection of WGS and exome | 0.002 | 0.000 | 16 | |

| 17 LQTS genes | ||||

| WGS | One transcript, all exons | 2.83 | 0.07 | 9 |

| Personalis exome | One transcript, all exons | 2.02 | 0.57 | 0 |

| Personalis exome | All transcripts, CDS only | 1.84 | 0.05 | 0 |

| Intersection of WGS and exome | 0.32 | 0.000 | 10 | |

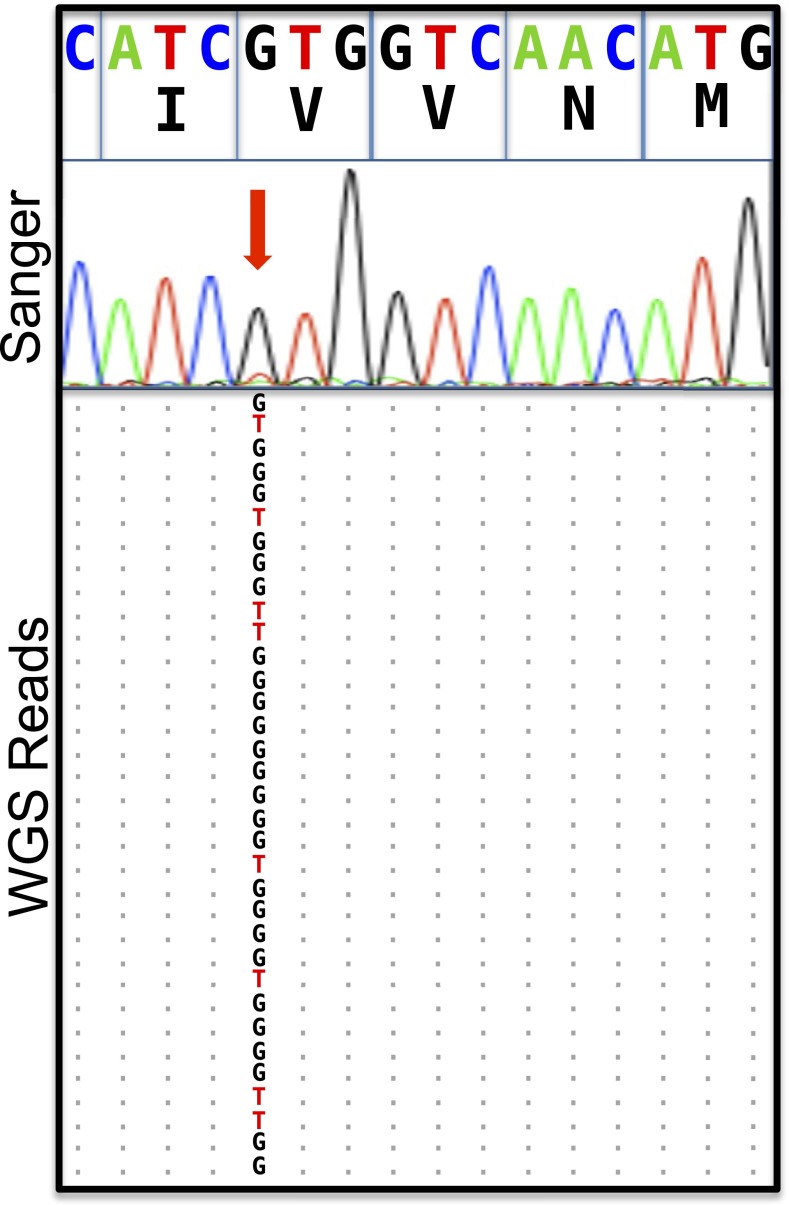

Given the discrepant results between the WGS pipelines, we performed Sanger sequencing of PCR amplicons derived from proband blood and saliva that did not show the T allele coding for the p.(V1762L) mutation. Inspection of raw reads and Sanger electropherograms suggested a low abundance of the mutant T allele (eight reads) compared with the G allele (26 reads) (Fig. 2). Because the reads supporting the 23.5% mutant allele fraction displayed good sequence quality and were without evidence of strand bias, and because manual inspection and remapping of the mutant reads confirmed their optimal mapping to SCN5A despite the paralogous evolutionary relationship of SCN5A to other ion channels, we elected to perform exome sequencing of the family trio using a second proband blood sample and saliva samples from each parent. Deep augmented exome sequencing confirmed the presence of the T allele uniquely in the proband sample at a ratio of 17 mutant T allele reads to 210 G allele reads, a mutant allele fraction of 7.5%. Deleterious variation in the SCN5A gene is associated with a spectrum of interrelated cardiac disorders including LQTS and DCM (23, 24), and no additional Mendelian or somatic variants causative for LQTS or cardiomyopathy were discovered on exome sequencing or WGS (SI Methods and Table S2 and Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Mosaicism in the SCN5A locus is suggested by rapid genome sequencing and confirmed by augmented deep-exome sequencing. Alignments of next-generation sequencing reads from the SCN5A gene on chromosome 3 derived from rapid genome sequencing, with a cartoon alignment of the reverse complement of next-generation sequencing reads covering base pairs 38, 592, 565–38, 592, and 580 and a Sanger electropherogram suggestive of mosaicism indicated by the red arrow. Coordinates are from the hg19 assembly of the human genome. The allelic balance by genome sequencing (26 G, 8 T) is unlikely to arise from a 50:50 balance at a heterozygous locus (one-sided binomial test, P = 0.001), and the allelic balance observed by exome sequencing (210 G, 17 T) effectively rules out a variant with Mendelian inheritance at this position.

Table S2.

Coding variants in 23 DCM genes

| Chromosome | Start position | End position | Reference allele | Alternate allele | Father genotype | Mother genotype | Patient genotype | Gene | Exonic function | Gene model and amino acid change | MAF ESP 6500 | MAF 1,000 Genomes AFR | MAF 1,000 Genomes AMR | MAF 1,000 Genomes ASN | dbSNP137 | PolyPhen2 score | PolyPhen2 prediction | GERP score |

| Chr1 | 236,899,900 | 236,899,900 | TC | T | 1/0 | 1/0 | 1|1 | ACTN2 | Frameshift deletion | uc001hyg.2:c.91delC:p.P31fs | . | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.51 | rs150406169 | . | . | . |

| Chr1 | 236,910,983 | 236,910,983 | G | A | 1/0 | 0/0 | 1|0 | ACTN2 | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc010pxu.1:c.G490A:p.D164N | 0.000231 | . | . | 0.09 | rs80257412 | 0.006 | B | 5.68 |

| Chr10 | 121,436,286 | 121,436,286 | C | T | 0/0 | 0/1 | 0|1 | BAG3 | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc001lel.3:c.C1217T:p.P406L | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.24 | rs3858340 | 0.652641 | NA | 5.59 |

| Chr10 | 112,572,458 | 112,572,458 | G | C | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1|1 | RBM20 | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc001kzf.2:c.G2303C:p.W768S | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | 1 | rs1417635 | . | . | . |

| Chr10 | 112,595,719 | 112,595,719 | G | C | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1|1 | RBM20 | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc001kzf.2:c.G3667C:p.E1223Q | 0.76 | 0.41 | 0.8 | 0.77 | rs942077 | . | . | . |

| Chr3 | 38,616,876 | 38,616,876 | C | T | 0/0 | 0/1 | 0|1 | SCN5A | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021wvw. 1:c.G2408A:p.R803Q | 0.000846 | . | 0.0028 | 0.04 | rs41261344 | . | . | . |

| Chr3 | 38,674,712 | 38,674,712 | T | C | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0|1 | SCN5A | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021wvx. 1:c.A95G:p.Q32R | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.68 | rs6599230 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,444,768 | 179,444,768 | C | G | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.G40051C:p.A13351P | 1 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | rs4145333 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,615,887 | 179,615,887 | T | C | 1/1 | 1/0 | 1|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc002unb.2:c.A11240G:p.D3747G | 0.82 | 0.6 | 0.73 | 0.77 | rs922984 | 0.563193 | NA | 4.55 |

| Chr2 | 179,615,931 | 179,615,931 | C | G | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc002unb.2:c.G11196C:p.L3732F | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1 | 1 | rs922985 | 0.411494 | NA | 3.92 |

| Chr2 | 179,620,951 | 179,620,951 | C | T | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vsz. 1:c.G10739A:p.G3580D | 0.9 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.77 | rs7585334 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,621,477 | 179,621,477 | C | T | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vsz. 1:c.G10213A:p.A3405T | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | rs6433728 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,623,758 | 179,623,758 | C | T | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc002umz. 1:c.G239A:p.S80N | 0.9 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.78 | rs2291310 | 0.209507 | NA | −2.9 |

| Chr2 | 179,629,461 | 179,629,461 | C | T | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vsz. 1:c.G9643A:p.V3215M | 0.9 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.78 | rs2291311 | 0.41084 | NA | 4.32 |

| Chr2 | 179,644,035 | 179,644,035 | G | A | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vsz. 1:c.C3746T:p.S1249L | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.87 | rs1552280 | 0.350141 | NA | 5.29 |

| Chr2 | 179,432,185 | 179,432,185 | A | G | 0/1 | 0/0 | 1|0 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.T51479C:p.I17160T | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.04 | rs12463674 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,481,602 | 179,481,602 | G | C | 1/0 | 0/0 | 1|0 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.C20819G:p.T6940R | . | . | . | . | rs557711303 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,545,859 | 179,545,859 | C | T | 0/1 | 0/0 | 1|0 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc002umz. 1:c.G19538A:p.R6513H | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.04 | rs36051007 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,644,855 | 179,644,855 | T | C | 1/0 | 0/0 | 1|0 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vsz. 1:c.A3463G:p.K1155E | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.6 | 0.2 | rs10497520 | 0.383601 | NA | 4.18 |

| Chr2 | 179,397,561 | 179,397,561 | C | T | 0/0 | 0/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.G76586A:p.R25529H | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.41 | rs3829747 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179406191 | 179406191 | C | T | 0/0 | 0/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.G70418A:p.R23473H | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.42 | rs3731749 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,421,694 | 179,421,694 | A | G | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.T60992C:p.I20331T | 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.67 | rs9808377 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,427,536 | 179,427,536 | T | C | 1/0 | 1/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.A56128G:p.I18710V | 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.67 | rs3829746 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,436,020 | 179,436,020 | G | A | 0/0 | 1/0 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.C47644T:p.R15882C | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.42 | rs744426 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,436,532 | 179,436,532 | T | C | 0/0 | 1/0 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.A47132G:p.K15711R | . | . | . | . | rs530190665 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,438,273 | 179,438,273 | G | A | 0/0 | 1/0 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.C45391T:p.R15131C | . | . | . | 0.0017 | rs185626486 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,451,420 | 179,451,420 | G | A | 1/0 | 1/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.C37013T:p.T12338I | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.68 | rs2042996 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,457,147 | 179,457,147 | G | A | 0/0 | 1/0 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.C32390T:p.P10797L | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.43 | rs16866406 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,458,591 | 179,458,591 | C | T | 0/0 | 0/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.G31241A:p.R10414H | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.43 | rs2288569 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,464,527 | 179,464,527 | T | C | 1/0 | 1/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.A28906G:p.N9636D | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.69 | rs1001238 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,558,366 | 179,558,366 | T | C | 1/0 | 1/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc010fre. 1:c.A1165G:p.I389V | 0.33 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.53 | rs2042995 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,582,537 | 179,582,537 | G | T | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0|1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc002umz. 1:c.C11315A:p.A3772E | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.64 | rs2627043 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,444,939 | 179,444,939 | C | T | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc021vtb. 1:c.G39880A:p.V13294I | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.2 | 0.6 | rs2303838 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,554,305 | 179,554,305 | C | T | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc010fre. 1:c.G1465A:p.G489R | 0.43 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.15 | rs2244492 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,582,327 | 179,582,327 | C | T | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc002umz. 1:c.G11525A:p.S3842N | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.42 | rs13390491 | . | . | . |

| Chr2 | 179,587,130 | 179,587,130 | C | G | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | TTN | Nonsynonymous SNV | uc002umz. 1:c.G8635C:p.D2879H | 0.16 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.43 | rs12693166 | . | . | . |

ESP, Exome Sequencing Project; GERP, Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling.

Table S3.

Noncoding variants in 23 DCM genes

| Chromosome | Position | dbSNP137 | Reference allele | Alternate allele | Patient genotype | Regulome DB score | Functional analysis | Roadmap epigenomics cardiac tissue chromatin evidence | Transcription factor binding sites | Gene one (distance) | If intergenic, gene two (distance) | Noncoding function | Repeatmasker name | Repeatmasker class |

| Chr6 | 13,3513,253 | . | GTG | G | 1/0 | 2b | Repetitive region | . | . | LINC00326 (85,537) | EYA4 (48,481) | Intergenic | (TG)n | Simple_repeat |

| Chr15 | 63,345,889 | rs138123255 | TTTG | T,TT | 1/2 | 2b | Repetitive region | . | . | TPM1 | . | Intronic | AluSg | SINE |

| Chr15 | 63,405,268 | rs11350481 | GA | G | 1/1 | 2b | Repetitive region | . | . | TPM1 (41,156) | LACTB (8,730) | Intergenic | AluSg7 | SINE |

| Chr10 | 112,511,649 | . | G | T | 0/1 | 2b | Repetitive region | . | . | RBM20 | . | Intronic | L1MC1 | LINE |

| Chr15 | 63,146,064 | rs5813179 | GT | G | 1/0 | 2b | Repetitive region | . | . | TLN2 (9,236) | TPM1 (188,773) | Intergenic | MER58C | DNA |

| Chr15 | 63,397,044 | rs2729833 | G | A | 1/1 | 2b | Repetitive Region | . | . | TPM1 (32,931) | LACTB (16,955) | Intergenic | MLT1B | LTR |

| Chr15 | 63,397,047 | rs2729834 | G | C | 1/1 | 2b | Repetitive region | . | . | TPM1 (32,934) | LACTB (16,952) | Intergenic | MLT1B | LTR |

| Chr1 | 201,346,931 | . | T | G | 1/0 | 2b | Absence of chromatin evidence | Weak/repressed/inactive | . | TNNT2 | . | Upstream | . | . |

| Chr10 | 121,438,608 | rs11460195 | G | GA | 0/1 | 2b | AP1 transcription factors may regulate BAG3 | Open chromatin fetal heart | MAFK, FOS, MYC, POL2RA, | BAG3 (1,279) | INPP5F (46,951) | Intergenic | . | . |

| Chr10 | 88,431,323 | rs57702354 | C | G | 0/1 | 2b | No evidence of transcriptional regulation | Active transcriptional start site in multiple tissues | HNF4a | LDB3 | . | Intronic | . | . |

| Chr14 | 23,861,882 | . | T | G | 1/0 | 2b | No evidence of transcriptional regulation | Transcriptional chromatin state in multiple cardiac tissues | RAD21 | MYH6 | . | Intronic | . | . |

| Chr15 | 63,315,787 | rs35798724 | G | GAA | 0/1 | 2b | Absence of chromatin evidence | Weak/repressed/inactive | . | TLN2 (178,958) | TPM1 (19,051) | Intergenic | . | . |

| Chr15 | 63,322,669 | rs35102434 | C | CAA | 1/1 | 2b | No evidence of transcriptional regulation | Transcriptional chromatin state in multiple cardiac tissues | CEBPB | TLN2 (185,840) | TPM1 (12,169) | Intergenic | . | . |

| Chr15 | 63,182,663 | rs34295763 | A | AT | 0/1 | 2b | Distant from DCM gene | . | . | TLN2 (45,834) | TPM1 (152,175) | Intergenic | . | . |

| Chr15 | 63,188,280 | rs143517671 | AT | A | 1/0 | 2b | Distant from DCM gene | . | . | TLN2 (51,452) | TPM1 (146,557) | Intergenic | . | . |

| Chr15 | 63,347,226 | rs33918146 | T | TA | 1/1 | 2b | No evidence of transcriptional regulation | Transcriptional chromatin state in left ventricular tissue | POLR2A, GATA2, GATA1, GATA3, TCF12, TCF7L2 | TPM1 | . | Intronic | . | . |

| Chr15 | 63,358,032 | rs58304847 | CT | C | 1/0 | 2b | No evidence of transcriptional regulation | Transcriptional chromatin state in multiple cardiac tissues | POLR2A, RFX3, NR3C1 | TPM1 | . | Intronic | . | . |

| Chr15 | 63,390,176 | . | GA | G | 1/0 | 2b | Absence of chromatin evidence | Weak/repressed/inactive | . | TPM1 (26,064) | LACTB (23,822) | Intergenic | . | . |

| Chr3 | 38,609,218 | rs200767733 | A | C | 0/1 | 2b | Absence of chromatin evidence | Weak/repressed/inactive | . | SCN5A | . | Intronic | . | . |

| Chr6 | 133,569,835 | . | TG | CA,CG | 1/2 | 2b | Absence of chromatin evidence | Weak/repressed/inactive | . | EYA4 | . | Intronic | . | . |

| Chr1 | 201,317,506 | . | G | GGTGGGAG | 0/1 | 2b | Absence of chromatin evidence | Weak/repressed/inactive | . | PKP1 (15,385) | TNNT2 (10,636) | Intergenic | . | . |

The V1762L Channel Displays Profoundly Abnormal Late Sodium Current with a Dominant Effect.

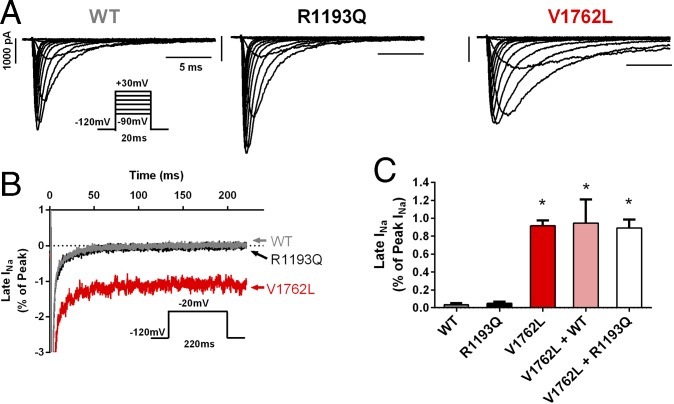

The valine residue 1762 occurs within a highly conserved transmembrane helix of NaV1.5. In a previously reported case of perinatal LQTS, a methionine mutation caused by a single-nucleotide variant at the identical genomic position (rs199473631, c.5284G > A predicting p.V1762M) showed a late sustained sodium current (INa) and rapid recovery from inactivation compared with the WT channel (25). In representative whole-cell INa recorded from human tsA201 cells, the V1762L mutant channel exhibited delayed INa inactivation compared with the WT channel and resulted in the expression of a large late INa (Fig. 3A). Full inactivation of the INa within a 220-ms interval, as seen in the WT and R1193Q channels, was not observed in the V1762L channel (Fig. 3B), and the late INa was significantly greater than in WT channels [0.92 ± 0.06% (SEM) of peak INa, n = 6 versus 0.03 ± 0.02% of peak INa; n = 6, respectively; P < 0.001] (Fig. 3C). The persistent late INa seen in the V1762L construct was unchanged when cotransfected with either WT SCN5A or the common R1193Q variant channel, suggesting a dominant effect of V1762L on the action potential (Fig. 3C). The abnormal inactivation observed for the V1762L construct is expected to be particularly severe because it combines both a slowed time course of inactivation and large non-inactivating INa. The R1193Q variant did not exhibit a functional defect compared with WT channels, as is consistent with its predicted role as a benign or weakly modifying common variant. The profoundly abnormal late INa displayed by the V1762L construct in vitro is strongly consistent with the pathogenic mechanism of LQTS.

Fig. 3.

p.(V1762L) mutant channel exhibits defective INa inactivation consistent with a LQT3 phenotype. (A) Representative whole-cell INa traces recorded from cells expressing WT (Left), the common variant R1193Q (Center), or the mutant V1762L (Right). Note the delayed INa inactivation in the V1762L channel. (B) Extended voltage-step protocols reveal a late (sustained) INa conducted by V1762L (red trace), which was absent in both the WT and R1193Q channels. The dotted line indicates zero current. (C) The average late INa conducted by V1762L was significantly greater than that in WT (0.92 ± 0.06% of peak INa, n = 6, versus 0.03 ± 0.02% of peak INa, n = 6, respectively; *P < 0.001). No late INa was seen with the R1193Q mutation. The V1762L construct exerted a strongly dominant effect when cotransfected with either the WT channel (V1762L + WT) or R1193Q mutant (V1762L + R1193Q), maintaining a profoundly abnormal late INa.

Mosaicism of the p.(V1762L) Variant Is Present in Multiple Tissues and Is Expressed in Cardiomyocytes.

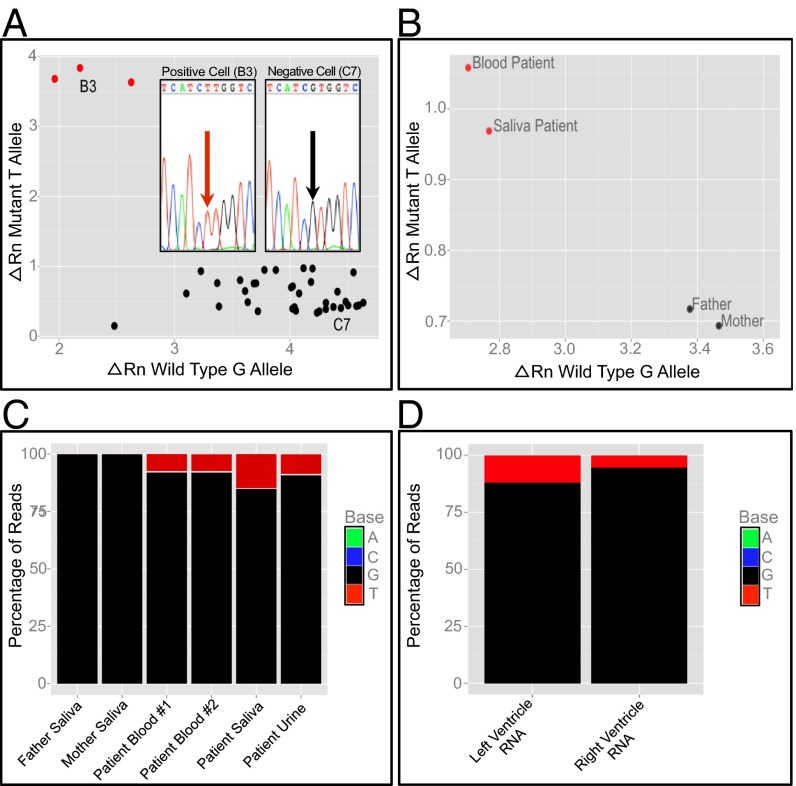

To verify the mosaicism of p.(V1762L) at the single-cell level, individual peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a third blood draw were isolated, lysed, and genotyped with a custom assay following whole-genome amplification. We detected the p.(V1762L) variant in amplified DNA from 3 of 36 isolated cells (Fig. 4A). Direct Sanger sequencing of cloned PCR products derived from these single cells confirmed the genotyping assay (Fig. 4A, Inset). We repeated the TaqMan genotyping assay in standard fashion on proband and parental DNA and again detected the T allele uniquely in the proband sample only (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Single-cell genotyping and targeted resequencing suggest that a mutation event causing mosaicism occurred before gastrulation. (A) qPCR genotyping of amplified DNA from 36 individual peripheral blood mononuclear cells identifies a subpopulation of three cells (red) that contain the T allele encoding the p.(V1762L) variant. A positive cell (B3) and negative cell (C7) are identified for the purposes of Sanger sequencing of cloned PCR products, respectively confirming the presence and absence of the mutant T allele (Inset). For each axis, the ΔRn value represents the magnitude of the signal generated from annealing of the allele-specific fluorescent probe to either the mutant or the WT allele relative to a signal generated from a passive reference dye during PCR amplification. (B) qPCR genotyping of DNA from proband blood, proband saliva, and parental saliva demonstrates the presence of the T allele only in proband samples. (C) Resequencing of PCR amplicons from four separate proband and both parental samples demonstrates that the frequency of the mutation is similar in proband blood (7.9%), urine (9.1%), and saliva (14.8%) samples, but the mutation is absent in both parental samples. (D) RNA sequencing of patient heart samples from the left and right ventricles identifies SCN5A reads containing the mutant allele.

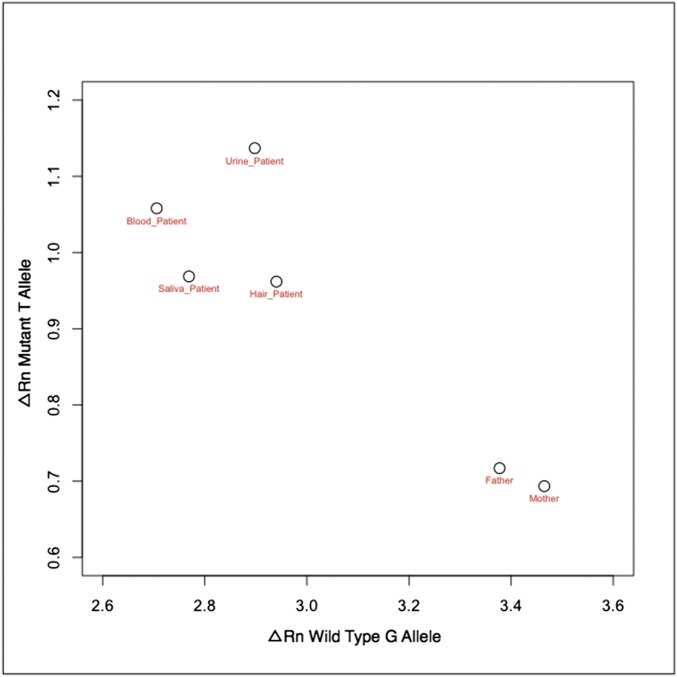

The timing of a mutation event during early embryogenesis would significantly affect the abundance and tissue lineages of clonal subpopulations of cells containing a variant. To determine when the mutation event occurred and to quantify the extent of mosaicism directly, we performed next-generation sequencing of PCR amplicons derived from proband DNA sources representing cellular lineages originating from the three primordial germ layers: blood (mesoderm), urine (endoderm), and saliva (endoderm and ectoderm). Tissue representing all three lineages revealed that the T allele comprised 7.9–14.8% of all high-quality reads and was absent from parental samples (Fig. 4C); a quantitative PCR (qPCR) genotyping assay confirmed the presence of the T allele uniquely in all proband DNA samples (Fig. S1). The presence of the allele in all primordial germ layers suggested that the mutation occurred during the cell divisions expanding the blastocyst before gastrulation and that the presence of the mutation was not limited to hematopoietic derivatives. To confirm this finding, two separate ventricular myocardial samples were obtained at the time of heart transplant; RNA sequencing revealed expression of the mutant allele in 5.4–11.8% of all SCN5A transcripts (Fig. 4D).

Fig. S1.

TaqMan genotyping of DNA from proband tissues originating from all germ layers and both parental samples suggests the presence of the mutant T allele only in the proband samples.

A Computational Model of Cardiac Electrophysiology Links Mosaicism in the Conduction Tissue to Arrhythmia.

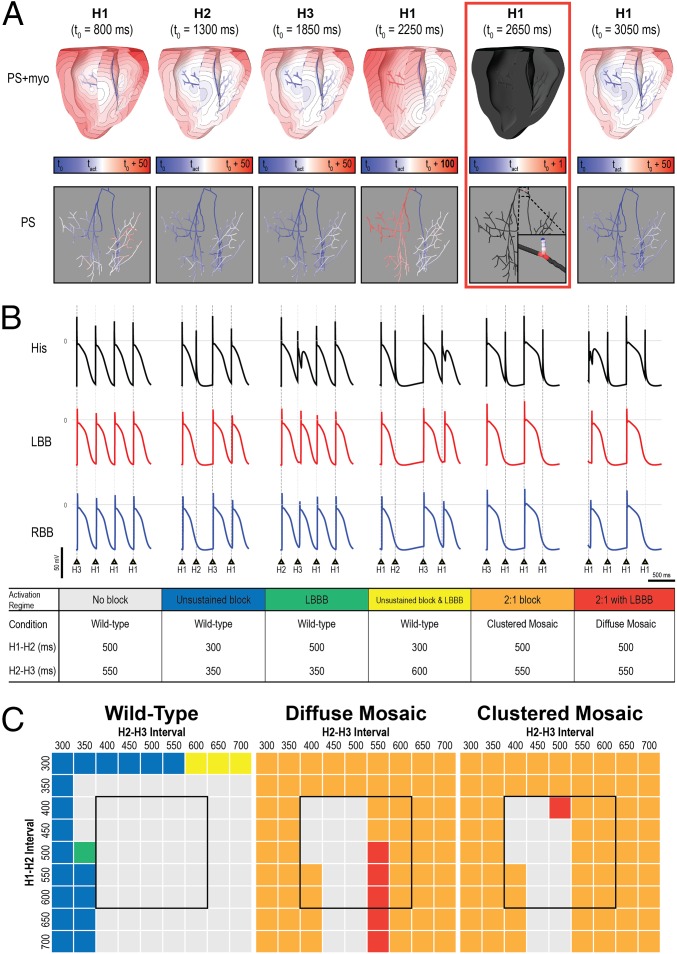

To explore the mechanism by which a small proportion of cells with persistent late INa in mosaic expression patterns could give rise to the observed clinical phenotype (2:1 block and/or proarrhythmic activation sequence), we performed simulations using a biophysically detailed 3D model of the ventricles including the Purkinje system. We considered two possible patterns of mosaicism (Fig. S2): diffuse and clustered. Mosaicism in ventricular cardiomyocytes alone did not recapitulate the 2:1 block or arrhythmia-prone phenotype observed in our patient. However, when mosaicism also was incorporated in the Purkinje fibers, a subset of pacing sequences resulted in 2:1 block (i.e., every other His bundle stimulus produced no ventricular activation) (Fig. 5A). With the three models of cellular distribution (WT, diffuse mosaic, clustered mosaic), the simulations showed six distinct ventricular activation regimes resulting from the 81 different pacing sequences tested (Fig. 5B). Highly arrhythmogenic behavior (i.e., 2:1 block with or without left bundle branch block, LBBB) was observed for the majority of pacing sequences in both the diffuse mosaic model (in which arrhythmogenic behavior was observed for 79% of pacing configurations) and the clustered mosaic model (in which arrhythmogenic behavior was observed in 80% of pacing configurations) but never in the WT model (Fig. 5C). Notably, pacing sequences with coupling intervals within the physiological range for resting neonatal heart rates (400- to 600-ms cycle length; black boxes in Fig. 5C) led to 2:1 block in 48% of the simulations conducted with the diffuse mosaic model and in 52% of the simulations conducted with the clustered mosaic model. For the same pacing sequences, no instances of conduction block or LBBB were observed in the WT model.

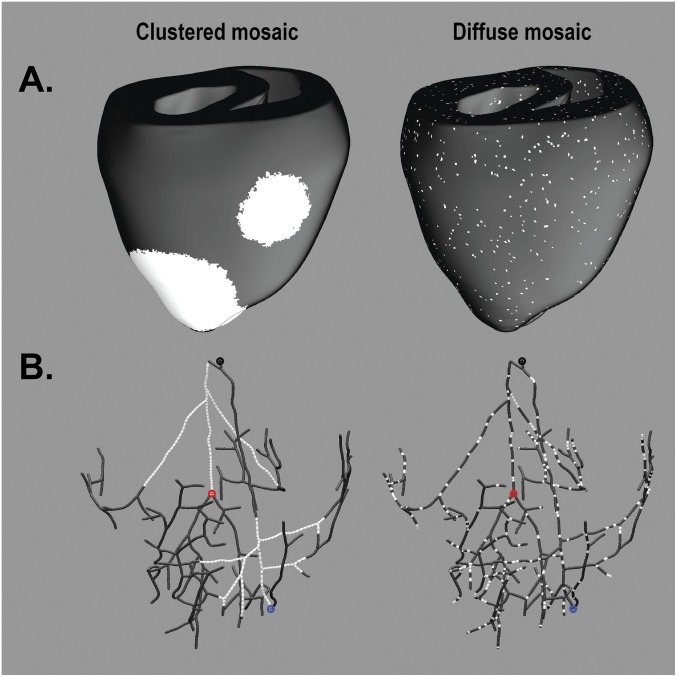

Fig. S2.

Visualization of diffuse and clustered mosaic models. (A) Images of clustered (Left) and diffuse (Right) distribution of V1762L-positive cells (white) in the ventricular myocardial walls (black). (B) As in A, but for the Purkinje system. Points in B indicate locations from which action potential traces were extracted in Fig. 5 for the His-bundle (His; black), LBB (red), and RBB (blue) activations.

Fig. 5.

Mosaic expression of the V1762L mutation in a 3D computational model of fetal ventricles and the Purkinje system leads to 2:1 block and LBBB. (A) Activation maps for six consecutive His bundle stimuli (delivered at t0 shown for each map) for the diffuse mosaic model; cutaway (Upper) and Purkinje-only (Lower) views are shown. Activation time scales are relative to t0 and vary for the different beats. Panel 4 shows an LBBB excitation sequence; excitation of the left side of the Purkinje system was caused by retrograde conduction from ventricular tissue. Panel 5 (red box) shows a conduction block in the His bundle, which initiated the 2:1 block activation regime. (B) Representative action potential sequences from the His bundle and the left/right bundle branches (LBB and RBB) for the six distinct activation regimes observed in response to different pacing protocol configurations: no blocked sinus beats; single blocked beat (i.e., no 2:1 block), without or with LBBB; LBBB with no blocked beats; and 2:1 block without or with LBBB. In cases with LBBB, action potential onset in the LBB was delayed (rightward shift), and late excitation of the His bundle caused by retrograde conduction was observed as a bump during repolarization. Fig. S2B shows the exact Purkinje locations from which action potential traces were extracted. (C) Summary of outcomes for all 243 unique simulations (81 pacing sequences in three models); the color of each entry corresponds to one of the activation regimes in B. Black boxes highlight the range of coupling intervals associated with the normal resting sinus rate for human infants.

Early Somatic Mosaicism Is Detectable in Patient Populations with LQTS.

Having established a plausible mechanism by which a percentage of cells with abnormal late INa might significantly alter the cardiac action potential, we sought to determine more broadly the prevalence of early somatic mosaicism among individuals with a genetic arrhythmia. We looked for evidence of mosaicism among a group of 7,500 samples submitted to a commercial testing company for one or more next-generation sequencing panel tests for genetic arrhythmias (up to 30 genes tested). Among the 7,500 individuals, four affected individuals, i.e., 0.05% of all cases, displayed apparent mosaicism within a gene causing LQTS. In studies of panel genetic testing, a causal genetic variant is typically identified in ∼70% of individuals undergoing genetic testing for genetic arrhythmia, leaving 30% without a diagnosis (15); our results suggest a prevalence of mosaicism in ∼0.17% of undiagnosed cases. Of the four individuals with mosaic variants, one was an infant, and none displayed another Mendelian LQTS variant that explained the arrhythmia phenotype. Three additional individuals with pathogenic mosaic variants in LQTS genes appeared to be founders, because they were identified when undergoing family testing for an affected relative with a Mendelian LQTS variant. These data confirm that early somatic mutation events occurring before gastrulation are a relatively uncommon occurrence and that early mosaicism represents a rare but recurrent cause of genetic arrhythmias.

Discussion

Although LQTS has long been considered a Mendelian disorder, deep characterization of a single patient and population-scale data suggest that early somatic mosaicism is a rare cause of human arrhythmias. Here we present an integrative computational simulation of the cardiac action potential that illustrates a pathogenic mechanism by which mosaicism within the specialized conducting tissue alters the predisposition to arrhythmia; this mechanism is missing from previous reports of other arrhythmias caused by somatic mosaicism (3, 6). Together these data link a small amount of cellular heterogeneity to disordered cardiac rhythm.

To explore the fundamental mechanism by which a profound derangement in a small percentage of cells within the heart might cause a severe phenotype, we developed an organ-level computational simulation of the cardiac action potential integrating mosaicism at the cellular level with generic representations of an infant-sized heart. Given the absence of primary electrophysiological data from neonatal human cardiomyocytes, the parameters for ion flux do not account for immature calcium handling unique to newborn cardiac physiology.

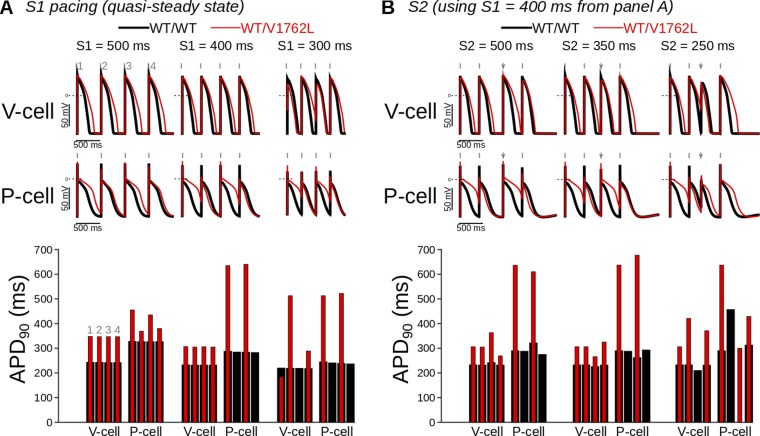

Nevertheless, the finite model simulation suggested that somatic mosaicism within the Purkinje system can lead to abnormal electrophysiological propagation consistent with LQTS, offering a potential explanation for the development of an arrhythmia-prone substrate. Previous computational and experimental work has also suggested that the Purkinje system may play a primary role in arrhythmias related to LQTS (26, 27). Our simulations demonstrated significantly prolonged action potential duration resulting from increased late INa (Fig. S3), which increased the propensity for block occurring in the Purkinje system. Both the diffuse and clustered mosaic models showed 2:1 AV block at physiological heart rates observed in the infant and are consistent with the clinical observation of immediate improvement in cardiac conduction parameters with dual-chamber pacing. When combined with the clinical and genetic observations, the simulation data provide additional support for the pathological role of the Purkinje system in arrhythmias and suggest a mechanism by which even a small amount cardiac mosaicism may result in clinically significant arrhythmia.

Fig. S3.

Simulated pacing-induced single-cell ventricular myocyte and Purkinje action potential traces (WT vs. V1762L-positive) highlight mutant contributions to irregular excitation and repolarization. WT and mutant action potentials are in black and red, respectively. Shown are action potential traces (Upper) and corresponding action potential durations (Lower) (calculated at 90% repolarization time). (A) Single-cell pacing (S) at the cycle lengths of 500, 400, and 300 ms resulted in 1:1 capture in ventricular cells (V-cell) but not in Purkinje cells (P-cell), where long action potentials were followed by skipped beats. (B) Cell responses to pacing at S1 = 400 ms (gray tick marks) followed for a premature or delayed S2 stimulus (S2 = 500, 350, and 250 ms; gray arrows). Among mutant cases (i.e., model configurations including the V1762L mutation), Purkinje cell responses showed inconsistent stimulus capture, whereas ventricular cells responded to all stimuli except those at the shortest coupling interval tested.

The association of early somatic mosaicism with LQTS adds to the developing framework describing the contribution of postzygotic mutations to human genetic variation. In a recently proposed model of human germline mutation rates derived from exome sequencing of a large autozygous population, the contribution of postzygotic mutations to germline mutation rates was below the threshold of detection (28). In an alternative empirical approach tracing the origin of de novo mutations in 50 trios undergoing WGS, only 0.1% of de novo mutations were derived from low-level parental gonadal mosaicism (2). However, in the same study, 6.5% of presumed de novo mutations displayed allelic imbalance, suggesting a postzygotic mutation event (2). Modeling of postzygotic mutation rates in a third family-based study suggests different rates over the course of embryonic development and postnatal life, with mutation rates peaking during the rapid cell divisions underlying organogenesis following gastrulation (29). Although the prevalence of mosaic variation in our population-based sample of 7,500 individuals appears relatively low, at 0.05%, this conservative estimate accounts only for the detection of early mutation events occurring in all tissues throughout the body (and thus detectable in blood or saliva) during approximately the first four postzygotic cell divisions. To ascertain the possibility of disease-causing tissue-specific mutation events occurring later during development, when mutation rates may be higher (29), systematic surveys of DNA obtained directly from diseased tissues or cell-free DNA are necessary.

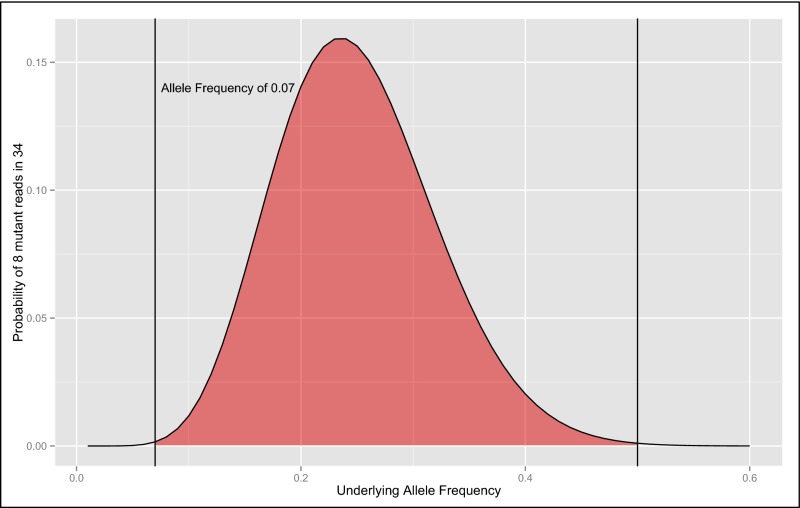

Conspicuously, the commercial gene-panel test for this patient returned a negative result, and somatic mutations of relatively low abundance are not universally reported by commercial gene-panel testing. For detection of early mosaic mutation events (occurring during the 10 cell divisions after fertilization before gastrulation), the count of individual molecules derived from next-generation sequencing-by-synthesis chemistries enables a simple likelihood estimation of the underlying allelic balance. The observation of exactly 8 of 34 (23.5%) variants containing reads from a heterozygous locus (Fig. 2) was strongly suggestive of an underlying imbalance of alleles (Fig. S4). When tuned to detect mosaicism, simple analytical schema based on the binomial distribution are adaptable to sequencing reads from gene-panel, exome, or whole-genome tests to detect mutations present in all tissues arising from early somatic mutation events. Although secondary confirmation has previously been the gold standard for confirming mosaicism, next-generation sequencing technologies are fundamentally more sensitive than Sanger sequencing in the detection of low-level mosaicism (2, 30). The accuracy of likelihood estimates and thus the sensitivity for detecting mosaicism in next-generation sequencing are related directly to the number of reads, thus strongly supporting the use of higher read-depth sequencing for clinical and research studies focused on detecting novel variants.

Fig. S4.

The exact probability of sampling 8 of 34 mutant reads varied by underlying allele frequency. The red area represents allele frequencies for which the probability of sampling 8 of 34 reads is greater than the probability arising from a heterozygous 50% allele ratio (P = 0.00106) by a one-sided binomial test. The maximal probability is an underlying mosaic allele frequency of ∼25% (P = 0.1564).

The discovery of a mosaic SCN5A variant affirms that rapid genetic diagnosis of neonatal disease by WGS may offer an alternative to standard gene-panel testing (31–33). In our view, rapid comprehensive genetic testing (WGS or whole-exome sequencing) should be used as a primary diagnostic inquiry in infants with life-threatening illness of unclear or suspected genetic etiology. Although the sensitivity and specificity for Mendelian variation have been the focus of applied and technical reports of clinical WGS (31, 34, 35), the discrepant results of the three WGS pipelines suggest that the predictive characteristics of WGS for somatic mosaicism are dependent on the informatics strategies used. Guidelines for detecting, confirming, and reporting mosaic variants in genes causing Mendelian disease in genetic diagnostics have yet to be addressed by professional organizations (36–38).

In summary, for a single case of perinatal LQTS we conclude that a mosaic variant, p.(V1762L), is pathogenic, demonstrating abnormal late INa, low-level mosaicism in multiple tissues throughout the body, and expression in cardiac tissue. A computational model of disease suggested a clear mechanism of pathogenesis linked to mosaicism in the conduction tissue. Finally, we show that early somatic mosaicism displays a low-level prevalence at a population scale. These data illustrate that somatic mosaicism represents a mechanism by which causal variation is missed in studies of genetic disease such as LQTS. However, our estimates of the prevalence of somatic mosaicism are limited to ascertaining early mutation events detectable in blood or saliva; events occurring later in development that are detectable only within cardiac tissue may constitute additional, as yet unmeasured genetic risk for LQTS. More broadly, our findings exemplify how careful scrutiny of WGS data and computational modeling of a single patient may serve as the foundation for new insights into human pathophysiology; such deep explorations will form the heart of precision medicine as applied to cardiovascular disease (39).

Methods

Genome sequencing was performed by Illumina Corporation, and exome sequencing, targeted sequencing, and RNA sequencing were performed by Personalis, Inc. Cellular patch-clamp measurements of INa were performed in human tsA201 cells using an Axoclamp 200B amplifier, Digidata 1400 digitizer, and pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated and loaded onto a prepared C1 small whole-genome amplification (WGA) microfluidic chip (Fluidigm Corporation), which performed lysis and whole-genome amplification on all viable cells. Computational simulations were conducted in a biophysically detailed 3D computational model of the heart calibrated to represent the size and geometry of the neonatal human ventricles, including representations of the Purkinje system and the muscle fiber orientation, using a validated software platform (19–21). Additional details may be found in SI Methods and Figs. S1–S7.

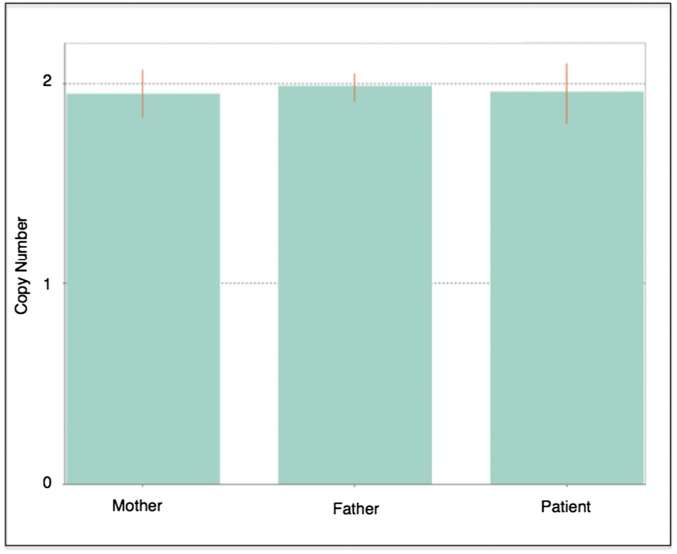

Fig. S7.

TaqMan CNV genotyping at a locus 279 bp distant from the p.V1762L variant does not reveal a microduplication of exon 28. The location of the probe on hg19 chromosome 3 is 38,592,297, whereas the p.V1762L variant occurs at chr3 38,592,576. SE measurements for each sample are denoted by the vertical orange lines.

All research presented here was conducted under the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Stanford Administrative Panels for the Protection of Human Subjects. On behalf of themselves and their infant daughter, the parents provided written informed consent for participation in this study. The parents also received genetic counseling from genetic counselors and physicians regarding the risks and benefits of genome sequencing. In the written consent process (as a checkbox on the consent form) and verbally, the parents expressed a preference to abstain from the report of incidentally discovered genetic information regarding long-term risks of other diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, or cardiovascular disease.

SI Methods

DNA Isolation.

DNA was isolated with the QiaAmp DNA-Investigator Kit (Qiagen) from 3–5 mL of whole blood with the QiaAmp Blood Mini Kit, from 5 mL of a bagged urine sample, and from a small clipping of hair. Saliva was collected with the Oragene Discover kit, and DNA was extracted from parental and proband samples using the Prep2It reagent (DNA Genotek, Inc.). All DNA samples were quantified with a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer using the dsDNA broad-range kit (Life Technologies, Inc.).

Next-Generation Sequencing Analysis.

Whole-genome sequencing.

CLIA-certified rapid WGS was performed as described previously (31). Briefly a library was prepared with a TruSeq PCR-free protocol, and DNA was sequenced at 2 × 100 bp paired-end read length on a HiSeq 2500 (Illumina Corporation). WGS yielded 120-Gb purity-filtered sequence data containing >80% of bases with a minimum quality value of 30. Raw sequence data were aligned and single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indel variants were called with three separate bioinformatic pipelines. A rapid and sensitive commercial software package, RTG Variant version 1.0.2 (Real Time Genomics, Inc.), was applied to the raw data for mapping, variant calling, and genotype filtration (40). A second Illumina pipeline used the Isaac genome alignment and variant-calling software (41). A third custom analysis pipeline developed at Personalis, Inc. was also used to call the variants using the BWA and the GATK (42, 43). The unprocessed whole-genome sequence data passing quality control, totaling 1,263,948,282 reads of 100-bp length, were received on DOL 8 ∼100 h after the blood draw. Read mapping with RTG to the University of California Santa Cruz human genome reference sequence (hg19) took 544 min, aligning 91% of the reads to yield a mean read depth of 39.76. SNP variant calling with RTG required 91 min, and filtering called sites with a read depth of 8 and an automated variant recalibration score of 0.02 yielded 4,434,585 variants with a transition-to-transversion ratio of 2.07. Additional postprocessing and annotation took 188 min. Finished data from the Illumina pipeline totaling 3,851,534 variants were received on a hard drive on DOL 9.

For the primary arrhythmia phenotype with a prolonged QT interval, we examined 17 genes associated with LQTS including AKAP9, ANK2, CACNA1C, CALM1, CALM2, CALM3, CAV3, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNH2, KCNJ2, KCNJ5, KCNQ1, SCN4B, SCN5A, SNTA1, and TRDN. To examine variants consistent with a rare disease-inheritance pattern (either a de novo mutation or variants inherited in a recessive fashion), variants occurring in pseudogenes or within a segmental duplication were excluded, and the remaining 404 coding variants were filtered by a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.02 or less in the 1,000 Genomes April, 2012 release (44). Filtration revealed the proband to be heterozygous for five rare exonic variants, including two variants in SCNA5: rs41261344 and a variant at chromosome 3 altering a G to T and thus causing a valine-to-leucine substitution described in the main text (SCN5A NM_000335: c.5284G > T, which predicts p.V1762L). The variant rs41261344 is a common polymorphism in Han Chinese NM_000335: c.3575G > A (p.R1193Q), with a MAF of 0.12, and has been reported to have a modest impact on the risk of LQTS (22). Sequence assessment of the cDNA change NM_000335: c.5284G > T did not suggest the creation of a new splice site (45, 46).

Exome sequencing.

Exome sequencing was performed on the trio consisting of the proband, mother, and father. DNA was isolated from blood (proband) and saliva (mother and father), and accuracy- and content-enhanced (ACE) whole-exome sequencing was performed at Personalis, Inc. Sequencing was performed to high depth, attaining a mean sequence read depth of 200×. ACE Exome data were aligned, and variants were called and annotated using the Personalis Pipeline. The trio’s data were analyzed through the Personalis Disease Variant Discovery Service, which identified and verified that c.5284G > T was present in 8% (17/210) of the sequence reads in the proband as a de novo event that was not present in either parent and did not identify any additional likely candidate variants in the exome.

Coding and noncoding analysis of DCM genes.

Analysis was limited to the 23 genes known to cause DCM (CMT2B1, MYH7, MYH6, SCN5A, MYBPC3, TNNT2, BAG3, ANKRD1, RBM20, LDB3, LGMD2G, TPM1, TNNI3, TNNC1, ACTC1, ACTN2, CSRP3, PSEN1, PSEN2, EYA4, DSG2, TAZ, and TTN) and was performed on both the exome and whole-genome sequence data.

Within TTN there were 32 protein-altering variants, whereas in the other 22 DCM genes there were seven protein-altering variants, all of which were common variants observed in multiple populations and thus were unlikely to be causative of severe and early DCM. There were two additional TTN variants, rs557711303 and rs530190665, observed previously in frequencies less than 1% MAF in Asian populations. However, all coding variants in the 23 DCM genes were inherited from an unaffected parent (Table S2).

Regulatory variants can be difficult to evaluate, and we used the multiple sources of information gathered by RegulomeDB to produce a useful scoring schema (47). Assuming that common noncoding variants have a small or negligible effect on the profound phenotypes observed, we filtered out common noncoding variants displaying a MAF greater than 1% in three HapMap populations [Americans of African ancestry in the Southwest United States (ASW), Han Chinese in Beijing (CHB), and Japanese in Tokyo (JPT)] along with four 1,000 Genomes populations [individuals of northern European ancestry (EUR), African ancestry (AFR), ad-mixed American (AMR), and individuals of East Asian ancestry (ASN)], leaving 727 remaining variants. Of the 727 noncoding variants in the 23 genes, the 21 highest-scoring variants were categorized as 2b, “likely to affect transcription factor binding” (Table S3) (47). The parents received whole-exome sequencing, and thus the functional impact of these variants cannot be filtered using inheritance information. Seven of the variants were observed to occur in repetitive regions and were unlikely to be causal of highly penetrant disease, and two variants were more than 100,000 bp distant from the DCM gene of interest and cannot definitively be associated with the gene.

Of the 14 remaining noncoding variants we examined the predicted state of local chromatin in cardiac tissue from the Roadmap Epigenomics project using available data (aorta, fetal heart, left ventricle, right atrium, right ventricle) as reported by RegulomeDB (accessed January 22, 2016). Of the six variants occurring in regions suggestive of open chromatin and/or transcriptional activity in one or more cardiac tissues, we performed a pathway analysis using the MetaCore software database (Thomson Reuters Corporation) to look for evidence of direct regulation of the transcription factor (a disrupted binding site predicted by RegulomeDB) and the DCM gene of interest; the included evidence was limited to experimentally observed data originating from cardiac-related tissue. The variant at chr10:121,438,608 disrupts an AP-1 site, a family of transcription factors that has been shown to regulate BAG3 (48); however, members of the AP-1 family of transcription factors (JUN, FOS, and ATF) typically function as secondary cofactors in regulating a diverse set of cellular processes (49–51), and the loss of a single binding site for a cofactor would not be strongly suggestive of causal association with the severe onset of DCM during infancy. The variant at chr10:88,431,322 disrupts an HNF4a-binding site; this disruption has no documented direct transcriptional effect upon LDB3 in cardiac-related tissues. The variant at chr14:23,861,882 disrupts a RAD21-binding site that has no documented direct transcriptional effect upon MYH6 in cardiac-related tissues. The variant at chr15:63,322,669 disrupts a CEBPB-binding site which has no documented direct transcriptional effect upon TPM1 in cardiac-related tissues. The variants at chr6:63,358,032 and chr6:63,347,226 disrupt multiple binding sites, none of which have documented direct transcriptional effects upon TPM1 in cardiac-related tissues. Thus, other than the SCN5A variant described in the main text, no coding or noncoding variants strongly suggestive of causality for DCM were discovered.

Targeted sequencing.

For targeted sequencing, three sets of staggered PCR primers (Fig. S6B) were synthesized and pooled to amplify the 28th exon of SCN5A from DNA originating from the first and second proband blood samples, proband urine, hair, and saliva, maternal saliva, and paternal saliva. AmpliTaq (Life Technologies, Inc.) was used per the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplification from proband hair did not yield a PCR product; all other amplicons were barcoded and prepared for sequencing at 250-bp read length on a MiSeq (Illumina Corporation). Raw fastq files were filtered for a quality score ≥35 for 90% of the read with the FastX-Toolkit software package and analyzed via custom shell scripts. The reported percentages arise from a minimum of 676,279 individual reads per sample.

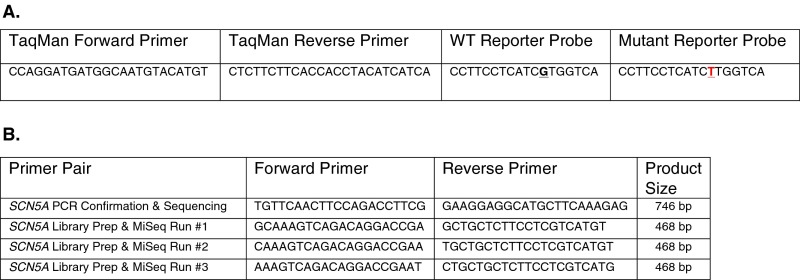

Fig. S6.

Primer and probe sequences for TaqMan (A) and PCR (B) experiments.

Whole-Cell Patch Clamping.

Expression of mutant channels.

Mutant constructs were created using a pcDNA3.1 vector containing the human WT SCN5A ORF (α5, NM_000335). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange II XL mutagenesis system (Stratagene) to create R1193Q and V1762L constructs. WT, R1193Q, or V1762L constructs were expressed with human β1 (NM_001037.4) in human tsA201 cells using PolyFect (Qiagen). Cells were grown in 60-mm tissue-culture dishes at 37 °C/5% CO2 in DMEM high-glucose medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Transfection complexes were made using 300 fmol of α5 and 150 fmol of β1. A plasmid encoding GFP (20 fmol, pEGFP-N1; Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) was included to mark positively transfected cells. Transfected cells were grown for 48–72 h before experimentation.

Electrophysiology.

All experiments were performed at room temperature using an Axoclamp 200B amplifier, Digidata 1400 digitizer, and pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). Patch electrodes (1.5–2 MOhm) were fabricated from borosilicate glass capillary tubes (World Precision Instruments) using a DMZ-Universal Puller (Zeitz Instruments GmbH). Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Unless otherwise noted, data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software), and statistical comparisons were made in reference to the WT channel.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed as described previously (52, 53). Human tsA201 cells were transfected and grown for 48–72 h before whole-cell patch clamping using an Axoclamp 200B amplifier, Digidata 1400 digitizer, and pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). Cells were allowed to stabilize for 10 min after establishment of the whole-cell configuration before current was measured. For all voltage-clamp experiments, series resistance was compensated 75% to minimize voltage error. Leak currents were subtracted by using an online P/4 procedure, and all currents were low-pass Bessel filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 50 kHz. Specific voltage-clamp protocols were used as depicted in figure insets. The bath solution consisted of (in mM): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 dextrose, 10 Hepes, with a pH of 7.4 (NaOH) and osmolarity of 310 mOsmol/kg (sucrose). The pipette solution consisted of (in mM) 105 CsF, 10 NaF, 20 CsCl, 2 EGTA, 10 Hepes, with a pH of 7.35 (CsOH) and osmolarity of 300 mOsmol/kg (sucrose).

Single-Cell Microfluidics, TaqMan Genotyping, and Sanger Sequencing.

A 3-mL whole-blood sample was drawn into a heparin-containing cell preparation tube and spun at 400 relative centrifugal force (RCF) at 24 °C for 30 min. Plasma was removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS before freezing with Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium and DMSO in liquid nitrogen. Cells were rewarmed quickly in a 37 °C water bath and resuspended in 5 mL of warm medium added drop by drop, followed by an additional 10 mL of warm medium, and were mixed by gentle pipetting. The cells were spun at 250 RCF for 5 min; then the medium was removed leaving a volume of approximately 1 mL. The cell pellet then was washed five times with 1 mL WGA wash buffer with a final spin of 1,500 RCF. The cells were resuspended carefully and thoroughly in resuspension buffer and counted with a manual hemacytometer, and the suspension was adjusted to a concentration of 500 cells/mL. Six microliters of the resuspension were removed and added to an additional 4 µL of resuspension buffer which then was loaded onto a prepared C1 small WGA microfluidics chip (Fluidigm Corporation) per the manufacturer’s protocol.

The cells were loaded in the C1 small WGA chip using the standard protocol, followed by LIVE/DEAD staining (Life Technologies, Inc.). The captured stained cells were imaged with a 100× objective, and manual inspection of micrographs from the 96 chambers showed that 36 contained a single cell that displayed a viable staining pattern. The chip was then returned to the C1 Single-Cell Auto Prep System (Fluidigm Corporation) using the manufacturer’s protocol with the GenomiPhi V2 multiple displacement amplification kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Amplification products were flushed and rearrayed on a 96-well plate, and DNA concentrations were quantified against a known DNA standard using the PicoGreen reagent (Life Technologies, Inc.) with a Tecan Fluorometric plate reader (Tecan Group, Ltd.) using standard techniques. Reflecting the absence of cellular genomic DNA, empty chambers displayed significantly less DNA amplification product than chambers with a cell displaying a viable signal or a viable and membrane-permeable signal; no wells contained a cell with only a membrane-permeable signal (Fig. S5). The DNA amplification products from the 36 wells corresponding to the flow chambers with visualized cells then were rearrayed to a 96-well plate and diluted to a concentration of 4.4 ng/µL.

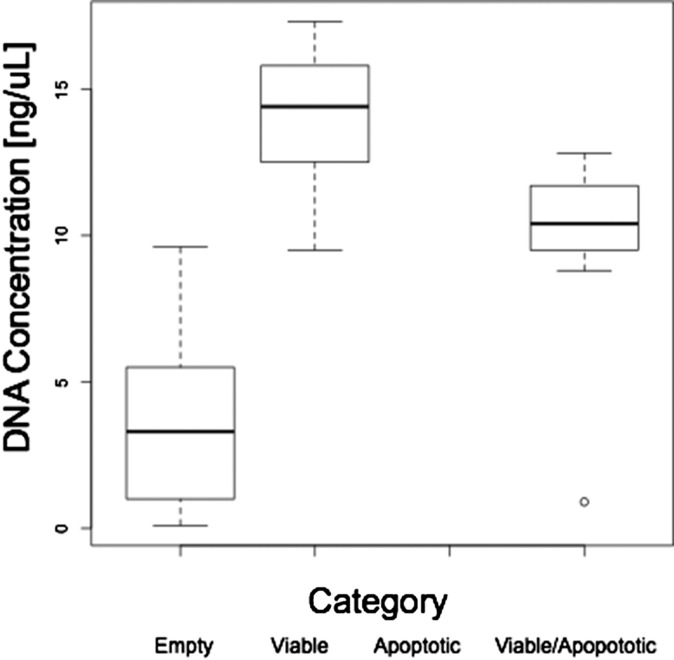

Fig. S5.

Cellular viability impacts DNA yield after single-cell isolation and whole-genome amplification. By staining category, dark lines represent the mean concentration, the boxes represent the first and third quartiles, whiskers represent the full range of included values, and round data points represent outliers not included in the calculations. Note that no individual cells stained uniquely for the apoptosis signal. The DNA detected in the empty wells may represent amplification of cell-free DNA or nonspecific amplification/polymerization of primer sequences from the WGA reaction.

Reactions were prepared using a custom TaqMan genotyping reagent (Fig. S6A) per the manufacturer’s instructions at a reaction volume of 5 µL containing DNA (either 20 ng amplified DNA from the single-cell isolation or 10 ng genomic DNA isolated from the parents and proband), 0.25 µL custom target assay, and 2.5 µL TaqMan Universal Genotyping Master Mix (Life Technologies, Inc.). The assay was run on a ViiA 7 real-time PCR system (Life Technologies, Inc.) for 40 cycles under standard reaction conditions. Genotyping data were analyzed with the manufacturer’s software and were exported to R for graphical representation using the ggplot2 package (54). No template controls were included with each genotyping experiment; each sample was run in duplicate or triplicate, and a mean was calculated for each displayed sample data point.

To rule out the possibility that the mutant reads originated from an undescribed pseudogene or microduplication containing the G-to-T mutation, we performed a qPCR (TaqMan) copy number variant (CNV) assay confirming that the 28th exon of the SCN5A gene existed within the proband genome in only two copies (Fig. S7). CNV genotyping was performed with a custom assay 279 bp downstream from the p.V1762L variant (probe: chr3:38,592,297; p.V1762L chr3:38,592,576). The CNV genotyping assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Inc.) with 10 ng of DNA against the RNaseP CNV reference assay. The assay was run on a ViiA 7 real-time PCR system for 40 cycles under standard reaction conditions, and CNV genotypes were called with the CopyCaller software (55).

PCR products were cloned into the pCR4Topo vector per the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Inc.), and single colonies from each well were subjected to rolling circle amplification before Sanger sequencing. All Sanger sequencing was performed on an ABI 3730xl DNA analyzer (Life Technologies, Inc.).

Computational Methodology.

Simulations were conducted in a biophysically detailed 3D computational model of the heart calibrated to represent the size/geometry of the neonatal human ventricles. The geometric structure and fiber orientations were based on a previously published rabbit heart, in which Purkinje system architecture was additionally incorporated (19, 21, 56, 57). Membrane kinetics in ventricular cardiomyocytes were represented by a human ventricular action potential model [O’Hara–Rudy model (58) with modifications for organ-scale simulations using fast INa from Ten Tusscher et al. (59)]. In the Purkinje system, we also used a human Purkinje cell action model (60). Excitation propagation in both types of tissue was governed by the monodomain formulation, as implemented in the CARP software package (CardioSolv LLC, Johns Hopkins University, and Université de Bordeaux) (61–63). Conductivity values in the Purkinje system and ventricular tissue were calibrated in such a way that His-ventricular and QRS intervals were consistent with literature values for normal neonates and infants (15 ms and 36 ms, respectively) (64, 65). Simulated cells positive for the V1762L mutation had a 10-fold increased late INa; this increase was based on the electrophysiological experiments in the present paper, which showed a dominant ∼10-fold increase for V1762L heterozygous (i.e., V1762L/WT) expression (Fig. 3). Simulations were executed either with WT conditions (normal late INa) or with 20% mosaic expression of V1762L (diffuse or clustered patterns). The 20% rate was chosen because experiments showed that mutant T alleles and transcripts comprised roughly 10% of total allelic and RNA populations, meaning that ∼20% of cells were heterozygous for the mutation. Spatial distributions of mutant cells for the two mosaic models were generated using a stochastic approach (density parameter = 0.2 for both cases; clustering parameter = 0 for the diffuse pattern and 0.95 for the clustered pattern) (66). Initial conditions were achieved by pacing ventricular and Purkinje action potential models to steady state with a basic cycle length of 400 ms, which corresponds to the normal resting fetal heart rate (65); then steady-state sinus rhythm in the whole-heart model was implemented by pacing the distal His bundle at a cycle length (H1–H1 interval) of 400 ms (65). Steady-state pacing was interrupted by consecutive, variably timed stimuli (H2 and H3); each stimulus was either premature or delayed, and stimuli were delivered at a variety of physiologically relevant coupling intervals (H1–H2 and H2–H3) ranging from 300–700 ms in 50-ms steps. Altogether, the pacing sequence (nine stimuli delivered as three H1 stimuli, followed by H2 and H3, and then four more H1 stimuli) was used to determine whether 2:1 block occurred.

SI Results

Clinical Presentation.

At 1 h of life the infant developed multiple episodes of TdP with a QTc of 542 ms (Fig. 1). Despite sedation and i.v. esmolol and magnesium, marked prolongation of the QTc to 740 ms was observed, with episodes of 2:1 AV block with an atrial rate of 120 beats per minute (bpm). Maternal and paternal ECGs were normal with a QTc of 413 ms and 406 ms, respectively. A standard commercially available genetic panel for LQTS was sent on DOL 1 (13, 17), and WGS was performed on DOL 3. Following 24 h of intermittent 2:1 AV block and transient episodes of TdP accompanied by hypotension, a dual-chamber epicardial ICD was inserted, and a bilateral stellate ganglionectomy was performed. After surgical intervention there was resolution of the arrhythmia with dual chamber (DDD) 1:1 AV-sequential pacing at 130 bpm. The echocardiogram showed an ejection fraction (EF) of 68% near hospital discharge on DOL 42. At 6 mo of age, the patient received two appropriate ICD discharges for sustained TdP. Echocardiogram revealed a markedly reduced EF of 24%, with subsequent decompensation requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support transitioned to a biventricular assist device (Berlin Heart, Inc.) followed by orthotopic heart transplant. Although the clinical presentation and available data are suggestive of a common genetic origin for both LQTS and DCM, we cannot exclude the possibility that the decreased EF was a rare complication of ventricular pacing (67).

Nominal Costs of Genetic and Genomic Testing.

A useful analysis of the cost-effectiveness of WGS as a diagnostic tool is not possible for a single case, but here we present the institutional costs of WGS and gene-panel testing. Although we describe extensive characterization and modeling of the genetic lesion in the main text, the initial diagnosis of mosaicism was derived from CLIA-certified rapid WGS. Excluding the fixed costs of computational infrastructure, analytical tools, and a care team with the capability of rapid interpretation of genomic data (31, 68), the nominal cost of data delivery for rapid clinical WGS was $11,400, or 1% of the median charge of $1,108,071.15 for an initial hospitalization of an infant with perinatal long-QT syndrome at our institution. In proportion to the price of a prolonged resource-intensive hospitalization, the cost of rapid WGS to establish a molecular diagnosis expediently is similar to the $3,375 institutional price for a standard commercial LQTS gene-panel test, which failed to identify the mosaic p.(V1762L) variant or any other clinically significant variant in this patient.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tina Hambuch; Marc Laurent at Illumina Corporation; Brian Hillbush and Len Trigg at Real Time Genomics; Christian Haudenschild at Personalis; and Justin Zook and Robert Dickson for discussions of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Grants DP2-OD006511 and U01-HG007708-03 (to E.A.A.) and R01 HL103428 and DP1 HL123271 (to N.A.T.). J.R.P. was supported by NIH Grants K12-HD000850 and K99-HL130523, and F.E.D. and M.V.P. were supported by NIH Grant T32-HL094274.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: At the time of this work K.M.K., S.R., and L.B. were employed by Gilead Sciences. M.J.C., S.T.K.G., S.B., J.W., and R.C. were employed by Personalis, Inc. J.W. and E.A.A. are founders of Personalis, Inc. which offers clinical genetic testing but does not offer Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified rapid-turnaround whole-genome sequencing. N.A.T. is a co-founder of CardioSolv LLC.

5Mercy Children’s Hospital, Kansas City, MO 64108.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1607187113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Biesecker LG, Spinner NB. A genomic view of mosaicism and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(5):307–320. doi: 10.1038/nrg3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acuna-Hidalgo R, et al. Post-zygotic point mutations are an underrecognized source of de novo genomic variation. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thibodeau IL, et al. Paradigm of genetic mosaicism and lone atrial fibrillation: Physiological characterization of a connexin 43-deletion mutant identified from atrial tissue. Circulation. 2010;122(3):236–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.961227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruark E, et al. Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Collaboration Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Mosaic PPM1D mutations are associated with predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer. Nature. 2013;493(7432):406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature11725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamuar SS, et al. Somatic mutations in cerebral cortical malformations. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(8):733–743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gollob MH, et al. Somatic mutations in the connexin 40 gene (GJA5) in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(25):2677–2688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King DA, et al. Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study Mosaic structural variation in children with developmental disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(10):2733–2745. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu JT, Kass RS. Recent progress in congenital long QT syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25(3):216–221. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32833846b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giudicessi JR, Ackerman MJ. Genotype- and phenotype-guided management of congenital long QT syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2013;38(10):417–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufendach KA, Giudicessi JR, Boczek NJ, Ackerman MJ. Maternal mosaicism confounds the neonatal diagnosis of type 1 Timothy syndrome. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e1991–e1995. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller TE, et al. Recurrent third-trimester fetal loss and maternal mosaicism for long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2004;109(24):3029–3034. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130666.81539.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etheridge SP, et al. Somatic mosaicism contributes to phenotypic variation in Timothy syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(10):2578–2583. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuneo BF, et al. Arrhythmia phenotype during fetal life suggests long-QT syndrome genotype: Risk stratification of perinatal long-QT syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6(5):946–951. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priori SG, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: Document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(12):1932–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lieve KV, et al. Results of genetic testing in 855 consecutive unrelated patients referred for long QT syndrome in a clinical laboratory. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17(7):553–561. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell JL, et al. Fetal heart rate predictors of long QT syndrome. Circulation. 2012;126(23):2688–2695. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.114132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aziz PF, et al. Congenital long QT syndrome and 2:1 atrioventricular block: An optimistic outcome in the current era. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(6):781–785. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crotti L, et al. Long QT syndrome-associated mutations in intrauterine fetal death. JAMA. 2013;309(14):1473–1482. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyle PM, Veenhuyzen GD, Vigmond EJ. Fusion during entrainment of orthodromic reciprocating tachycardia is enhanced for basal pacing sites but diminished when pacing near Purkinje system end points. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(3):444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez B, Li L, Eason JC, Efimov IR, Trayanova NA. Differences between left and right ventricular chamber geometry affect cardiac vulnerability to electric shocks. Circ Res. 2005;97(2):168–175. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000174429.00987.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyle PM, Massé S, Nanthakumar K, Vigmond EJ. Transmural IK(ATP) heterogeneity as a determinant of activation rate gradient during early ventricular fibrillation: Mechanistic insights from rabbit ventricular models. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(11):1710–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang HW, et al. R1193Q of SCN5A, a Brugada and long QT mutation, is a common polymorphism in Han Chinese. J Med Genet. 2005;42(2):e7–author reply e8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.027995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi R, et al. The cardiac sodium channel mutation delQKP 1507-1509 is associated with the expanding phenotypic spectrum of LQT3, conduction disorder, dilated cardiomyopathy, and high incidence of youth sudden death. Europace. 2008;10(11):1329–1335. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chockalingam P, Wilde A. The multifaceted cardiac sodium channel and its clinical implications. Heart. 2012;98(17):1318–1324. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang C-C, et al. A novel SCN5A mutation manifests as a malignant form of long QT syndrome with perinatal onset of tachycardia/bradycardia. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64(2):268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iyer V, Sampson KJ, Kass RS. Modeling tissue- and mutation- specific electrophysiological effects in the long QT syndrome: Role of the Purkinje fiber. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e97720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben Caref E, Boutjdir M, Himel HD, El-Sherif N. Role of subendocardial Purkinje network in triggering torsade de pointes arrhythmia in experimental long QT syndrome. Europace. 2008;10(10):1218–1223. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narasimhan VM, et al. A direct multi-generational estimate of the human mutation rate from autozygous segments seen in thousands of parentally related individuals. 2016 bioRxiv:059436. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahbari R, et al. UK10K Consortium Timing, rates and spectra of human germline mutation. Nat Genet. 2016;48(2):126–133. doi: 10.1038/ng.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck TF, Mullikin JC, Biesecker LG. NISC Comparative Sequencing Program Systematic evaluation of Sanger validation of next-generation sequencing variants. Clin Chem. 2016;62(4):647–654. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.249623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Priest JR, et al. Molecular diagnosis of long QT syndrome at 10 days of life by rapid whole genome sequencing. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(10):1707–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saunders CJ, et al. Rapid whole-genome sequencing for genetic disease diagnosis in neonatal intensive care units. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(154):154ra135. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talkowski ME, et al. Clinical diagnosis by whole-genome sequencing of a prenatal sample. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2226–2232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dewey FE, et al. Clinical interpretation and implications of whole-genome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1035–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller NA, et al. A 26-hour system of highly sensitive whole genome sequencing for emergency management of genetic diseases. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0221-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rehm HL, et al. Working Group of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Laboratory Quality Assurance Commitee ACMG clinical laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15(9):733–747. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Directors ABO. ACMG Board of Directors ACMG policy statement: Updated recommendations regarding analysis and reporting of secondary findings in clinical genome-scale sequencing. Genet Med. 2015;17(1):68–69. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hehir-Kwa JY, et al. Towards a European consensus for reporting incidental findings during clinical NGS testing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(12):1601–1606. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah SH, et al. Opportunities for the cardiovascular community in the Precision Medicine Initiative. Circulation. 2016;133(2):226–231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reumers J, et al. Optimized filtering reduces the error rate in detecting genomic variants by short-read sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;30(1):61–68. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raczy C, et al. Isaac: Ultra-fast whole-genome secondary analysis on Illumina sequencing platforms. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(16):2041–2043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenna A, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bentley DR, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456(7218):53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reese MG, Eeckman FH, Kulp D, Haussler D. Improved splice site detection in Genie. J Comput Biol. 1997;4(3):311–323. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1997.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dogan RI, Getoor L, Wilbur WJ, Mount SM. SplicePort–an interactive splice-site analysis tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W285–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyle AP, et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H-Q, et al. Involvement of JNK and NF-κB pathways in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced BAG3 expression in human monocytic cells. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitfield TW, et al. Functional analysis of transcription factor binding sites in human promoters. Genome Biol. 2012;13(9):R50. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]