Significance

Oxysterols promote tumor growth directly or through the dampening of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Whether oxysterols contribute to pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET) development and how they are generated within the pNET microenvironment are currently unknown. Here, we show that the 24S-hydroxycholesterol (24S-HC) oxysterol-generating enzyme Cyp46a1 is overexpressed during the angiogenic switch in rat insulin promoter 1–T-antigen 2 (RIP1-Tag2) pNET formation. Moreover, we report that Cyp46a1 overexpression requires hypoxia inducible factor-1a (HIF-1α). Importantly, we show that pharmacologic blockade and genetic inactivation of 24S-HC delays angiogenic switch and therefore tumor formation in RIP1-Tag2. Overexpression of Cyp46a1 transcripts in some human pNET samples suggests that targeting this axis in patients affected by pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors may be an effective therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: oxysterols, HIF-1α, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, angiogenic switch, neutrophils

Abstract

Cells in the tumor microenvironment may be reprogrammed by tumor-derived metabolites. Cholesterol-oxidized products, namely oxysterols, have been shown to favor tumor growth directly by promoting tumor cell growth and indirectly by dampening antitumor immune responses. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms governing oxysterol generation within tumor microenvironments remain elusive. We recently showed that tumor-derived oxysterols recruit neutrophils endowed with protumoral activities, such as neoangiogenesis. Here, we show that hypoxia inducible factor-1a (HIF-1α) controls the overexpression of the enzyme Cyp46a1, which generates the oxysterol 24-hydroxycholesterol (24S-HC) in a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET) model commonly used to study neoangiogenesis. The activation of the HIF-1α–24S-HC axis ultimately leads to the induction of the angiogenic switch through the positioning of proangiogenic neutrophils in proximity to Cyp46a1+ islets. Pharmacologic blockade or genetic inactivation of oxysterols controls pNET tumorigenesis by dampening the 24S-HC–neutrophil axis. Finally, we show that in some human pNET samples Cyp46a1 transcripts are overexpressed, which correlate with the HIF-1α target VEGF and with tumor diameter. This study reveals a layer in the angiogenic switch of pNETs and identifies a therapeutic target for pNET patients.

Recent studies have highlighted the diversity of metabolic pathways altered between normal and tumor cells (1, 2). Activation of specific metabolic pathways within tumors is believed to derive from an intricate connection among intrinsic and extrinsic factors, such as oncogenic signaling, stromal-derived molecules, and hypoxia (3). Tumor hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factor-1a (HIF-1α) activation have been linked to increased glucose metabolism and cancer progression in a number of tumor types (4). Whether HIF-1α signaling regulates other metabolic products in tumor cells or during tumorigenesis remains only partially understood.

The differential regulation of tumor metabolism and the relative abundance of some tumor-derived metabolites have also been shown to condition the tumor microenvironment, with particular emphasis on immune cell components (5). For example, metabolic products like pyruvic acid and lactic acid induce hypoxia-independent stabilization of HIF-1α in tumor-associated macrophages (6). These products, especially lactic acid, are products of the so-called Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) (7) and mainly require the enzymatic activity of the pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), an isoform expressed by tumor cells and associated with the production of high amounts of pyruvate and lactate (8). More recently cholesterol metabolism, oxysterols, and liver X receptors (LXRs) have been shown to be important players in tumor metabolism (9, 10), due to their dual involvement in tumor and immune cell biology (11–13). This dual involvement makes the LXR/oxysterol axis an attractive target for tumor therapies. Whether and how the LXR/oxysterol axis is governed by tissue determinants present within tumor microenvironments, such as hypoxia and tumor-specific metabolic regulations, remain elusive.

We recently showed that oxysterols recruit protumor neutrophils within the tumor microenvironment in an LXR-independent, CXCR2-dependent manner (14). Tumor-recruited neutrophils are endowed with proangiogenic activities, as they secrete MMP9 and Bv8 proangiogenic factors (14). We asked whether this axis was also active in a model of spontaneous pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET), i.e., the rat insulin promoter 1–T-antigen 2 (RIP1-Tag2) model (15), which is commonly used to investigate neoangiogenesis and to test the effectiveness of anti-angiogenic therapies (16). RIP1-Tag2 transgenic mice develop pancreatic β-cell tumors through the progressive transformation of beta cell islets from hyperplastic toward angiogenic islets. Then, a small fraction of angiogenic islets progresses to tumors (15, 17). MMP9+ myeloid cells sustain the angiogenic switch in this tumor model (18). Accordingly, the depletion of neutrophils releasing the proangiogenic factors MMP9 and Bv8 in RIP1-Tag2 mice greatly reduces the number of angiogenic islets (19, 20). In the present study, we investigated whether the neutrophil-dependent angiogenic switch occurring during RIP1-Tag2 pNET formation was dependent on oxysterols and attempted to define tissue conditions regulating oxysterol generation.

Results

Expression of Cholesterol Hydroxylases During pNET Tumorigenesis.

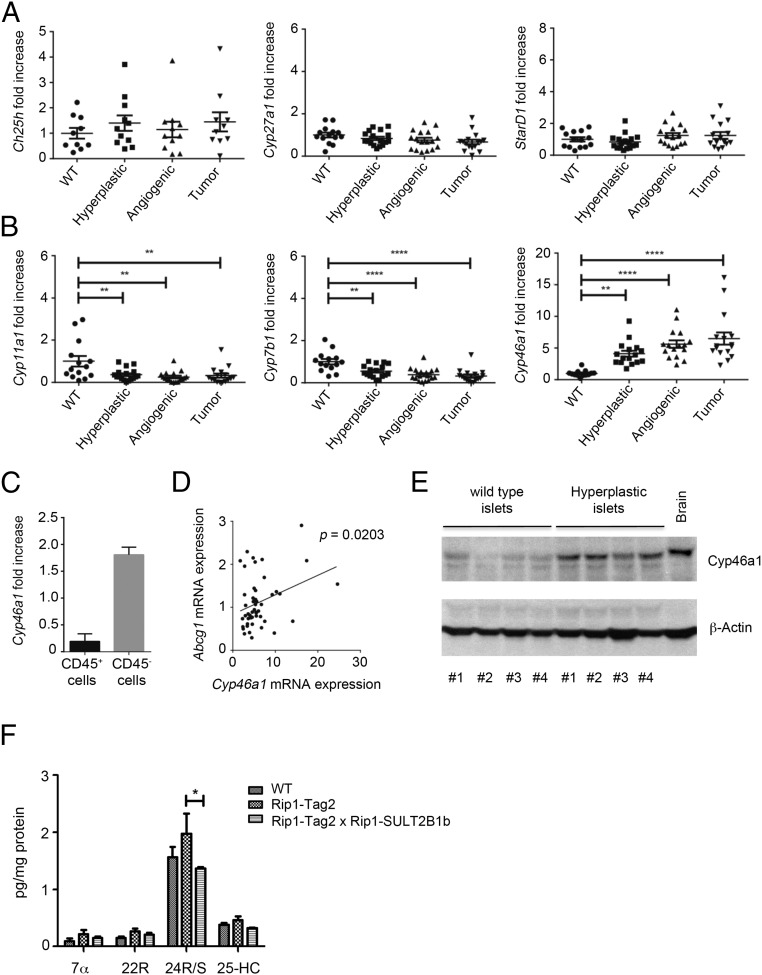

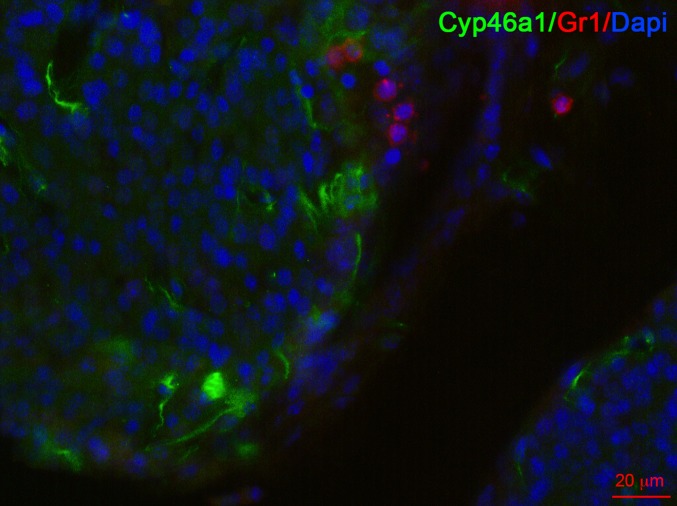

Oxysterols can be generated through autoxidation, by means of reactive oxygen species and through the activity of specific enzymes such as cholesterol 24-hydroxylase (Cyp46a1), cholesterol 27-hydroxylase (Cyp27a1), cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (Ch25h), Cyp7b1, Cyp3a4, and Cyp11a1 (21, 22). To determine the potential involvement of cholesterol hydroxylases in pNET, we first analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) the expression of their transcripts at various stages of pNET tumorigenesis. Ch25h, Cyp27a1, and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StarD1) transcripts (the latter encoding a cellular cholesterol transporter) were expressed by WT islets and by hyperplastic, angiogenic, and tumor islets at similar levels (Fig. 1A). Cyp11a1 and Cyp7b1 transcripts slightly decreased in all tumorigenic phases compared with WT islets (Fig. 1B), whereas the Cyp46a1 transcript, whose product forms 24S-hydroxycholesterol (24S-HC), was significantly and increasingly up-regulated during pNET tumorigenesis (Fig. 1B). The Cyp46a1 transcript was mainly expressed by the CD45− tumor fraction, which includes bona fide tumor cells, an observation in agreement with Cyp46a1 mRNA expression by βTC3, a tumor cell line arising from RIP1-Tag2 insulinomas (Fig. 1C and see Fig. 5A) (23). We found a statistically significant association between Cyp46a1 and Abcg1 mRNA expression during pNET tumorigenesis (Fig. 1D), the latter being a target gene of oxysterol-engaged LXRs. In agreement with Cyp46a1 transcript up-regulation, we also observed overexpression of the Cyp46a1 protein in hyperplastic islets from RIP1-Tag2 mice compared with WT islets from age-matched controls (Fig. 1E). Finally, we detected a higher amount of 24S-HC by LC-MS analysis in RIP1-Tag2 compared with WT pancreata, although it was not statistically significant (Fig. 1F). The other oxysterols detected were negligible (Fig. 1F). We have previously showed that 24S-HC oxysterol induces neutrophil migration (14). By performing immunofluorescence analyses of pancreata from 11-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 mice, we observed Gr1+ neutrophils in close proximity to 24S-HC–producing Cyp46a1+ cells (Fig. S1), thus indicating a preferential localization of the neutrophils close to the cells releasing 24S-HC oxysterol.

Fig. 1.

Expression of Cyp46a1 during RIP1-Tag2 tumorigenesis. (A) qPCR analysis for Ch25h, Cyp27a1, and StarD1 transcripts of WT, hyperplastic, angiogenic, and tumor islets purified from pancreata of 10-wk-old WT or RIP1-Tag2 mice. (B) qPCR analysis for Cyp11a1, Cyp7b1, and Cyp46a1 transcripts of WT, hyperplastic, angiogenic, and tumor islets purified from pancreata of 10-wk-old WT or RIP1-Tag2 mice. Each symbol corresponds to a single mouse, and the line represents the mean value: **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001. (C) qPCR analysis for Cyp46a1 mRNA of CD45+ and CD45− cells purified from tumor islets of pancreata of 10-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 mice. (D) Positive correlation between Cyp46a1 and Abcg1 mRNA expression (P = 0.0203 by Pearson test). (E) Western blot analysis for Cyp46a1 protein of WT and hyperplastic islets from 8-wk-old WT or RIP1-Tag2 mice. Brain was used as positive control. (F) Characterization and quantification of oxysterols purified from 11-wk-old WT, RIP1-Tag2, and RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b double transgenic mice; *P < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

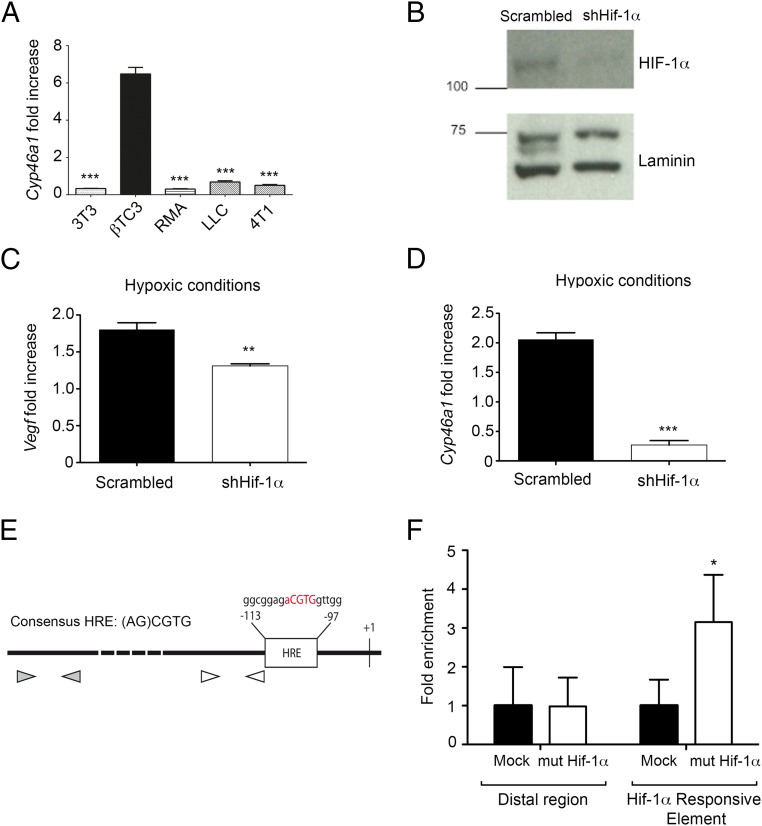

HIF-1α activates Cyp46a1 up-regulation in insulinomas derived from RIP1-Tag2 mice. (A) qPCR analysis for Cyp46a1 mRNA of NIH 3T3, βTC3, RMA, LLC, and 4T1 cell lines. Mean ± SEM of three experiments; ***P < 0.001. (B) Western blot analysis showing a marked decrease of HIF-1α protein levels in Hif-1α–silenced-βTC3 cells compared with scrambled βTC3 cells. One of three independent experiments with similar results is shown. (C) qPCR analysis for Vegf mRNA of scrambled- and Hif-1α–silenced-βTC3 cells. Mean ± SEM of three experiments; **P < 0.01. (D) qPCR analysis for Cyp46a1 mRNA of scrambled- and Hif-1α-silenced-βTC3 cells. Mean ± SEM of three experiments; ***P < 0.001. (E) A Hif-1α responsive element (HRE) in the Cyp46a1 promoter is shown. White arrowheads represent qPCR primers proximal to HRE region, whereas gray arrowheads represent qPCR primers located in Cyp46a1 promoter distal region (about −800 bp from transcription start). (F) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay on βTC3 cells transduced with a vector encoding a mutant stable form of HIF-1α. The selective enrichment of Hif-1α responsive element in the Cyp46a1 promoter of βTC3 cells expressing the mutant stable form of HIF-1α is shown. Mean ± SEM of two experiments; *P < 0.05.

Fig. S1.

Immunofluorescence analysis of pancreas from RIP1-Tag2 mice stained with anti-Cyp46a1 (green), anti-Gr1 (red) mAbs, and DAPI (blue), showing some neutrophils in close proximity of cells overexpressing Cyp46a1 protein. One of three independent experiments is shown. (Scale bar, 20 μm.)

Pharmacologic and Genetic Inactivation of 24S-HC Oxysterol Interferes with the Angiogenic Switch During pNET Tumorigenesis.

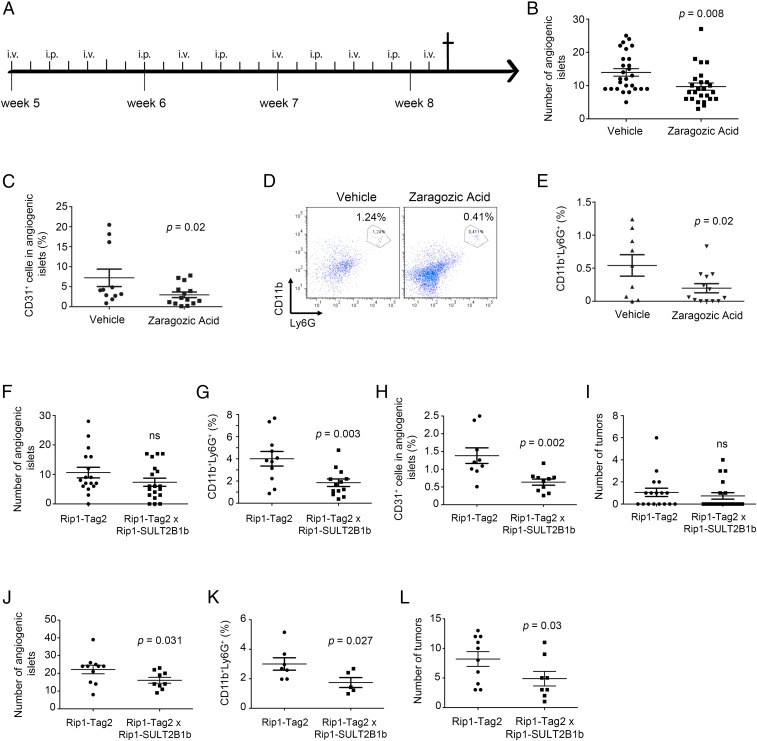

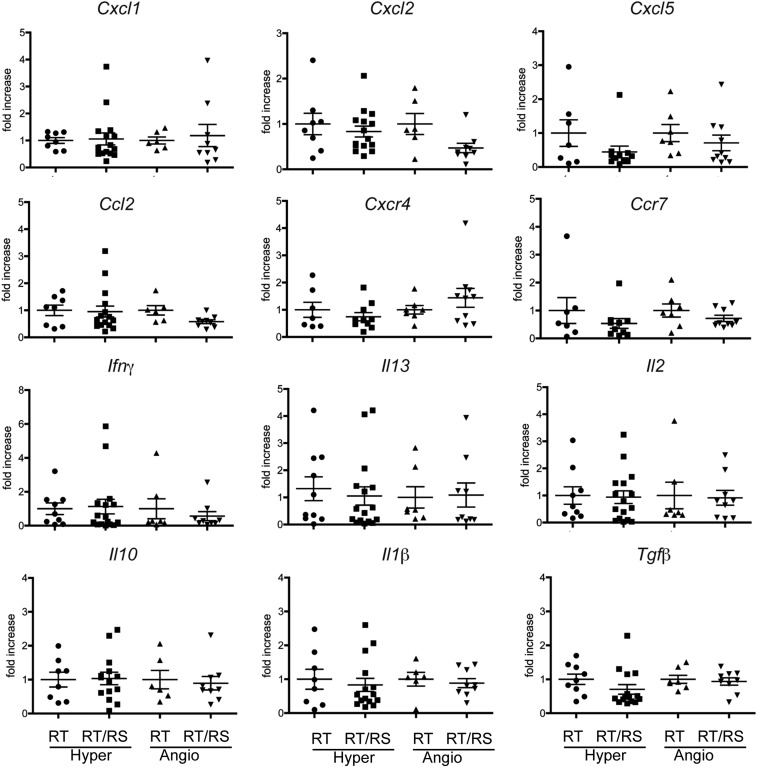

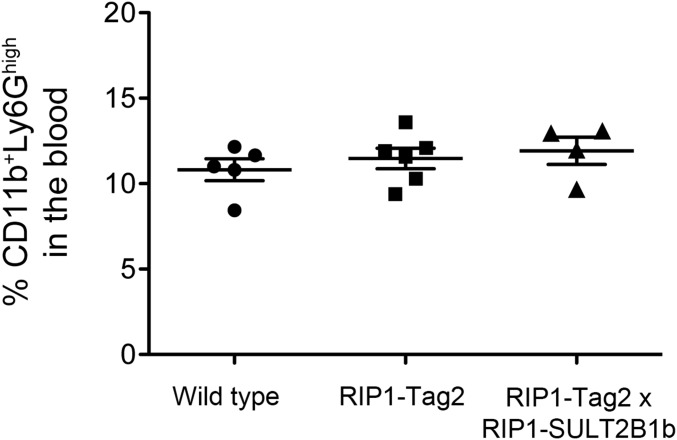

We first examined the role of 24S-HC in the tumorigenic process by treating mice with the cholesterol/oxysterol inhibitor zaragozic acid (ZA) (24). Five-week-old RIP1-Tag2 mice were treated with ZA (16) (Fig. 2A), and we observed a significant reduction in the number of angiogenic islets following ZA treatment (Fig. 2B) and a lower percentage of CD31+CD45− endothelial cells and CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils (Fig. 2 C–E) compared with vehicle-treated RIP1-Tag2 mice, suggesting that the blockade of cholesterol/oxysterol formation delays the tumorigenic process due to the reduction of angiogenic islets. Because we could not rule out the possibility that ZA might induce off-target effects ultimately leading to tumor growth control, we generated a transgenic mouse, in which the expression of the mouse oxysterol-inactivating enzyme sulfotransferase SULT2B1b (SULT2B1b) (25, 26) is driven by the rat insulin promoter (RIP1) in pancreatic β cells (Fig. S2A). The ULT2B1b transgene was highly expressed in the pancreas of RIP1-SULT2B1b transgenic mice compared with WT mice, as evaluated by qPCR (Fig. S2B). We then evaluated pNET tumorigenesis in RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b double transgenic mice (hereafter referred to as double transgenic mice). Double transgenic mice analyzed at early time points (8 wk) showed a lower number of angiogenic islets, albeit not significantly (Fig. 2F), and a lower percentage of CD31+CD45− endothelial cells and CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in angiogenic islets (Fig. 2 G and H), compared with RIP1-Tag2 mice. We did not notice any significant difference in the number of tumor islets, possibly due to the low frequency of tumor formation at this time point (Fig. 2I). At 11 wk, we observed a significant reduction of angiogenic islets (Fig. 2J), neutrophils (Fig. 2K), and tumor islets (Fig. 2L). In agreement with these results, we observed a lower amount of 24S-HC in pancreata of double transgenic mice compared with RIP1-Tag2 mice (Fig. 1F). Additionally, we did not observe any difference in the expression of common chemoattractive and inflammatory cytokines between pancreata of RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice (Fig. S3), strongly suggesting a predominant role of 24S-HC in the local recruitment of proangiogenic neutrophils, as evidenced by immunofluorescence analysis showing neutrophils close to 24S-HC–producing Cyp46a1+ cells (Fig. S1). Of note, we also evaluated the percentage of neutrophils in the blood of 8-wk-old WT, RIP1-Tag2, and double transgenic mice to rule out granulopoiesis promotion as a consequence of cholesterol/oxysterol alterations (27) in transgenic and double transgenic mice. However, we failed to detect any difference in the blood of the above-reported groups of mice (Fig. S4), further supporting the involvement of the local recruitment of neutrophils to the RIP1-Tag2 neoplastic islets.

Fig. 2.

Pharmacologic and genetic inactivation of oxysterols in RIP1-Tag2 mice inhibits angiogenic and tumor islet formation. (A) Zaragozic acid (ZA) treatment study design (Prevention trial). (B) Number of angiogenic islets in RIP1-Tag2 mice treated with vehicle or ZA; P = 0.008. (C) Percentage of CD31+CD45− endothelial cells in angiogenic islets of RIP1-Tag2 mice treated with vehicle or ZA; P = 0.02. (D) CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in angiogenic islets of RIP1-Tag2 mice treated with vehicle or ZA. FACS analysis of one representative experiment is reported. (E) Percentage of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in angiogenic islets of RIP1-Tag2 mice treated with vehicle or ZA; P = 0.02. (F) Number of angiogenic islets collected from pancreata of 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b (double transgenic) mice. Ns, not significant. (G) Percentage of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils collected from angiogenic islets of 8-wk-old pancreata of RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice; P = 0.003. (H) Percentage of CD31+CD45− endothelial cells in angiogenic islets collected from pancreata of 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice; P = 0.002. (I) Number of tumor islets collected from pancreata of 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice. Ns, not significant. (J) Number of angiogenic islets collected from pancreata of 11-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice; P = 0.031. (K) Percentage of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils collected from pancreata of 11-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice; P = 0.027. (L) Number of tumor islets collected from pancreata of 11-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice; P = 0.03. Each symbol corresponds to a single mouse, and the line represents the mean value ± SEM.

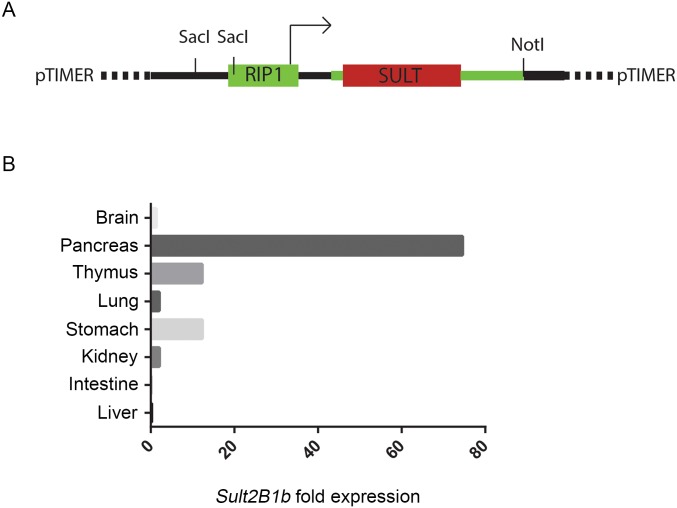

Fig. S2.

pTIMER plasmid used to generate RIP1-SULT2B1b transgenic mice and analysis of the expression of Sult2B1b in distinct organs from RIP1-SULT2B1b transgenic mice. (A) RIP1-Timer plasmid was linearized by NotI enzyme. DsRed1-E5 cDNA was replaced with SULT1B2b cDNA to generate RIP1-SULT2B1b pTIMER plasmid. (B) qPCR for Sult2B1b mRNA expression in distinct organs collected from a RIP1-SULT2B1b transgenic mouse. As expected, the highest expression of Sult2B1b transcripts was observed in the pancreas of RIP1-SULT2B1b transgenic mice. One of three independent experiments carried out in three RIP1-SULT2B1b transgenic mice is shown.

Fig. S3.

qPCR analysis of transcripts encoding different sets of chemokines and cytokines in hyperplastic and angiogenic islets collected from pancreata of 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b double transgenic mice. No major differences were observed between hyperplastic and angiogenic islets from pancreata of RIP1-Tag2 mice and RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b double transgenic mice. Hyper and Angio stand for hyperplastic and angiogenic islets, respectively. RT and RT/RS stand for RIP1-Tag2 mice and RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b mice, respectively.

Fig. S4.

FACS analysis to quantify CD11b+Ly6Ghigh neutrophils in the blood of WT, RIP1-Tag2, and RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b transgenic and double transgenic mice, respectively. The percentage of neutrophils in the blood was similar among the three groups of mice, ruling out effects of the SULT2B1b enzymatic activity on the granulopoiesis.

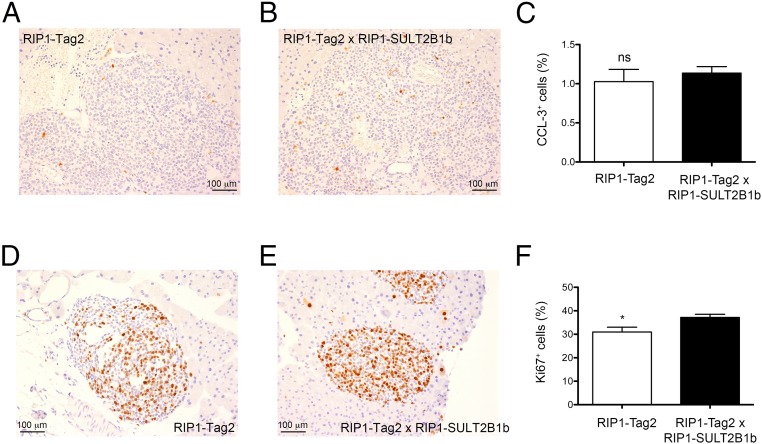

Delayed pNET Progression in RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b Double Transgenic Mice Is Independent of Intrinsic Effects of SULT2B1b Expression.

To rule out possible intrinsic cellular effects played by sulfated oxysterols, we analyzed proliferation and apoptosis, evaluated as Ki67 and cleaved caspase-3 (CCL-3), an activated form of caspase-3, respectively, in tumors from 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice. CCL-3 staining rates were similar between RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice (Fig. 3 A–C), whereas we observed increased proliferation in the tumors of double transgenic mice (Fig. 3 D–F). These results are in agreement with data reporting a proliferative advantage of mouse hepatocytes over-expressing SULT2B1b (28). In addition, given the delay of angiogenic and tumor islet formation in the double transgenic mice, these results suggest a predominant role of 24S-HC oxysterol on neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis in the RIP1-Tag2 model.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of cell proliferation and apoptosis of tumor islets from RIP1-Tag2 mice and RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b double transgenic mice. (A and B) Cleaved caspase-3 (CCL-3) immunohistochemical analysis of pancreata from 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice. One representative image from pancreata of RIP1-Tag2 (A) and double transgenic mice (B) is shown. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (C) Quantification of CCL-3+ cells in transformed islets of RIP1-Tag2 (n = 6 mice) and double transgenic mice (n = 7 mice). (D and E) Ki67 immunohistochemical analysis of pancreata from 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 and double transgenic mice. One representative image from pancreata of RIP1-Tag2 (D) and double transgenic mice (E) is shown. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (F) Quantification of Ki67+ cells in transformed islets of RIP1-Tag2 (n = 4 mice) and double transgenic mice (n = 6 mice); *P < 0.05.

Tissue Determinants Involved in Cyp46a1 Overexpression During pNET Tumorigenesis.

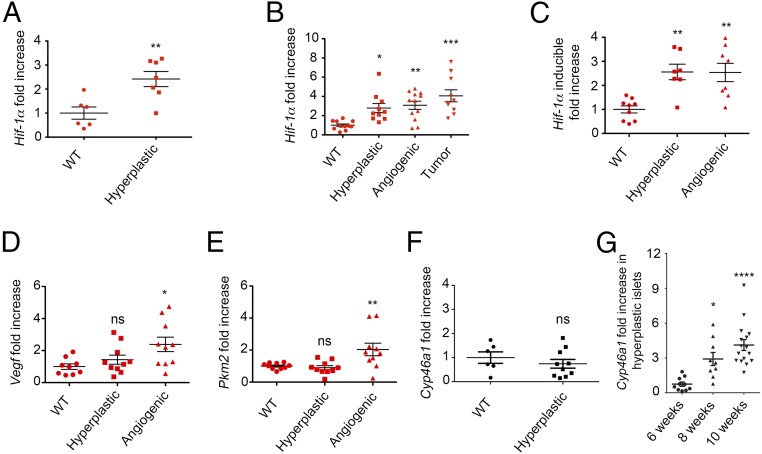

We sought to identify the determinants responsible for the up-regulation of Cyp46a1 enzyme in transformed cells of RIP1-Tag2 pancreata. We first investigated the role played by hypoxia in the angiogenic switch (29) but failed to detect HIF-1α protein in pancreata, as well as in isolated pancreatic islets from RIP1-Tag2 mice, although we used several commercially available anti–HIF-1α antibodies and different staining methods. Because transcriptional regulation of HIF-1α has also been recently reported in tumors (30), we carried out qPCR analysis to evaluate the expression of Hif-1α transcripts at different times during RIP1-Tag2 tumorigenesis. We observed the up-regulation of Hif-1α in hyperplastic islets of 6-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 mice (Fig. 4A). At 10 wk, Hif-1α transcripts were increased in hyperplastic, as well as angiogenic and tumor, islets (Fig. 4B). Remarkably, we observed the up-regulation of the inducible form of Hif-1α (31) (Fig. 4C), an observation recently reported in mouse macrophages (6). HIF-1α stabilization leads to the transcriptional activation of the bona fide HIF-1α targets Vegf and the enzyme pyruvate kinase isoform M2 (Pkm2) (32). Therefore, we analyzed Vegf and Pkm2 transcripts at different stages of RIP1-Tag2 tumorigenesis. Vegf and Pkm2 were found significantly up-regulated in angiogenic islets of 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 mice (Fig. 4 D and E). The up-regulation of Vegf mRNA was also observed in hyperplastic islets in addition to angiogenic and tumor islets of 10-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 mice (Fig. S5). Of note, the up-regulation of Pkm2 transcripts (Fig. 4E) suggests a possible relationship between the glycolytic metabolic switch and Hif-1α up-regulation during pNET tumorigenesis (33). Because hypoxia is one of the major drivers of HIF-1α stabilization, we carried out in vivo studies with the hydroxyprobe pimonidazole and detected hypoxic transformed islets in pancreata from 8-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 mice (Fig. S6). To evaluate whether Cyp46a1 was expressed concomitantly or after Hif-1α up-regulation, we carried out qPCR for Cyp46a1 at different times during pNET tumorigenesis. We failed to detect Cyp46a1 up-regulation at 6 wk (Fig. 4F), whereas it was significantly increased at later times (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

Tissue determinants associated with the up-regulation of Cyp46a1 transcripts during RIP1-Tag2 tumorigensis. (A) qPCR analysis for Hif-1α mRNA of WT and hyperplastic islets purified from pancreata of 6-wk-old WT and RIP1-Tag2 mice, respectively; **P < 0.01. (B) qPCR analysis for Hif-1α mRNA of WT, hyperplastic, angiogenic, and islets purified from pancreata of 10-wk-old WT and RIP1-Tag2 mice; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (C) qPCR analysis for the inducible form of Hif-1α mRNA of WT, hyperplastic, and angiogenic islets purified from pancreata of 8-wk-old WT and RIP1-Tag2 mice; **P < 0.01. (D) qPCR analysis for Vegf mRNA of WT, hyperplastic, angiogenic, and islets purified from pancreata of 10-wk-old WT and RIP1-Tag2 mice; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (E) qPCR analysis for Pkm2 mRNA of WT, hyperplastic, and angiogenic islets purified from pancreata of 8-wk-old WT and RIP1-Tag2 mice; Ns, not significant; **P < 0.01. (F) qPCR analysis for Cyp46a1 transcripts of WT and hyperplastic islets purified from pancreata of 6-wk-old WT or RIP1-Tag2 mice, respectively; Ns, not significant. (G) qPCR analysis for Cyp46a1 mRNA of hyperplastic islets purified from pancreata of 6-, 8-, and 10-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 mice; *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001. Each symbol corresponds to a single mouse, and the line represents the mean value ± SEM.

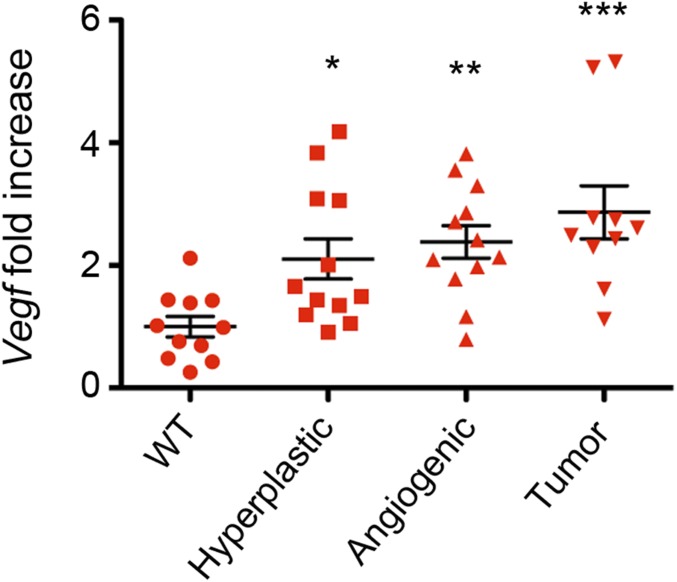

Fig. S5.

qPCR analysis for Vegf mRNA of WT, hyperplastic, angiogenic, and tumor islets purified from pancreata of 10-wk-old WT and RIP1-Tag2 mice. Each symbol corresponds to a single mouse, and the line represents the mean value ± SEM: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

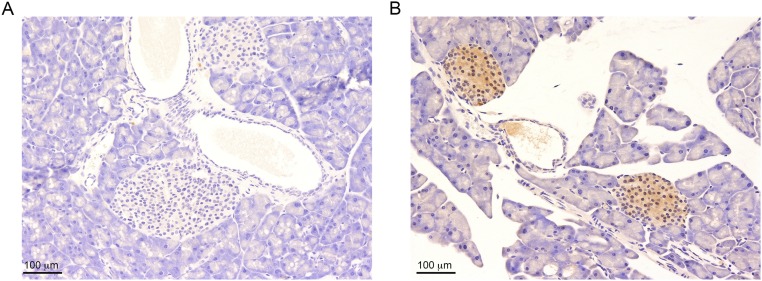

Fig. S6.

Pimonizadole staining of pancreas from RIP1-Tag2 mice. Pimonidazole adducts were detected with the Hypoxyprobe TM-1 kit. (A) Pancreas from RIP1-Tag2 mice incubated only with HRP-linked anti-FITC rabbit antibody and then developed with DAB with H2O2 and counterstained with hematoxylin (Ctrl). (B) Pancreas from RIP1-Tag2 mice incubated with FITC-conjugated mAb-1 and then as reported in A. Two pimonoidazole positive islets are readily detectable in B. One of four independent experiments is shown. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

HIF-1α Activates Cyp46a1 Overexpression in pNET-Derived Cells.

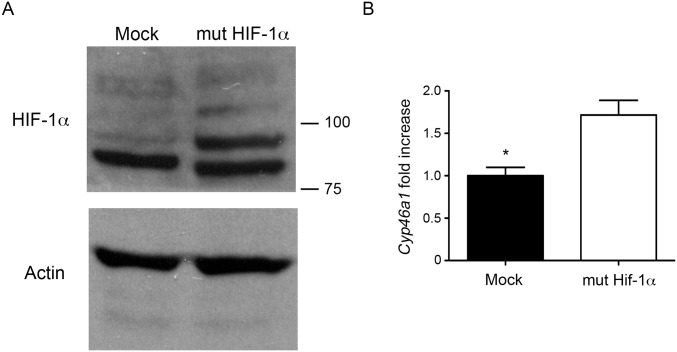

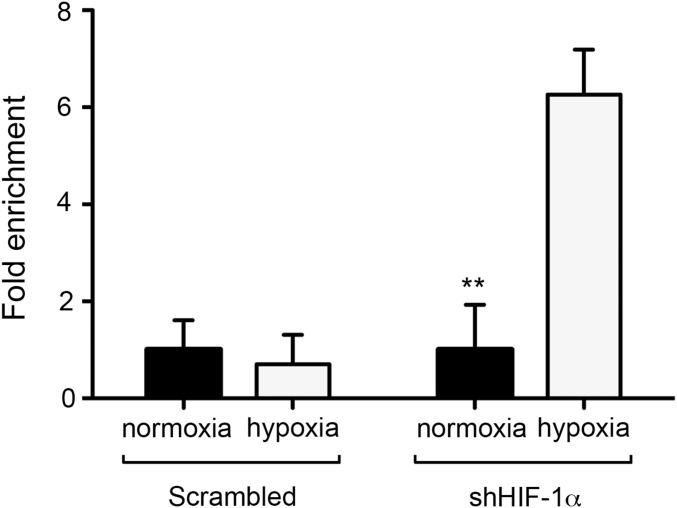

The results reported thus far point to a direct role of HIF-1α in the transcriptional activation of Cyp46a1 expression. To test this, we used βTC3 cells, a RIP1-Tag2–derived cell line (23). βTC3 cells express higher levels of Cyp46a1 transcripts compared with NIH 3T3 and other mouse tumor cell lines analyzed, such as RMA lymphoma, Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC), and 4T1 breast carcinoma (Fig. 5A). We treated βTC3 cells with an shRNA specific for Hif-1α, as demonstrated by Western blot analysis for HIF-1α (Fig. 5B) and analyzed the expression of transcripts encoding Cyp46a1 and Vegf in hypoxic culture conditions. Besides a modest decrease of Vegf expression, Hif-1α–silenced hypoxic βTC3 cells showed significantly reduced Cyp46a1 levels (Fig. 5 B and C), suggesting a direct role of HIF-1α in Cyp46a1 activation. To demonstrate a direct regulation of Cyp46a1 by HIF-1α, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed in βTC3 cells on expression of a mutant stable form of HIF-1α (34), as confirmed by Western blot analysis for HIF-1α (Fig. S7A) and qPCR analysis for Cyp46a1 transcripts (Fig. S7B). Increased recruitment of HIF-1α to its putative consensus-binding site located in the Cyp46a1 promoter and not to a distal region (Fig. 5D) was observed in βTC3 cells stably expressing HIF-1α, compared with mock-expressing cells (Fig. 5E). Similar experiments with 4T1 tumor cells confirmed recruitment of HIF-1α to the Cyp46a1 promoter in another cell context (Fig. S8).

Fig. S7.

Western blotting of HIF-1α and qPCR for Cyp46a1 expression on lentivirally transduced βTC3 cells. (A) Western blot analysis showing a marked expression of HIF-1α protein by βTC3 cells expressing the mutant stable form of HIF-1α (mut HIF-1α) compared with mock-transduced βTC3 cells (Mock). One of three independent experiments with similar results is shown. (B) qPCR analysis for Cyp46a1 showing the overexpression of Cyp46a1 transcripts by bTC3 cells expressing the mutant stable form of HIF-1α (mut HIF-1α) compared with mock-transduced βTC3 cells (Mock). Mean ± SEM of three experiments; **P < 0.05 (Student t test).

Fig. S8.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay on scrambled- and Hif-1α–silenced 4T1 cells kept in normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Increased recruitment of HIF-1α to its putative consensus-binding site located in the Cyp46a1 promoter was observed only in hypoxic Hif-1α–silenced 4T1 cells. Mean ± SEM of two experiments; *P < 0.01.

Altogether, these results indicate that in pancreatic islets undergoing large T antigen-mediated transformation, HIF-1α up-regulates the expression of Cyp46a1, which in turn produces the oxysterol 24S-HC that positions neutrophils in close proximity to hypoxic areas before the occurrence of the angiogenic switch.

Expression of Cyp46a1, VEGF, and HIF-1α Transcripts in Human pNET Samples.

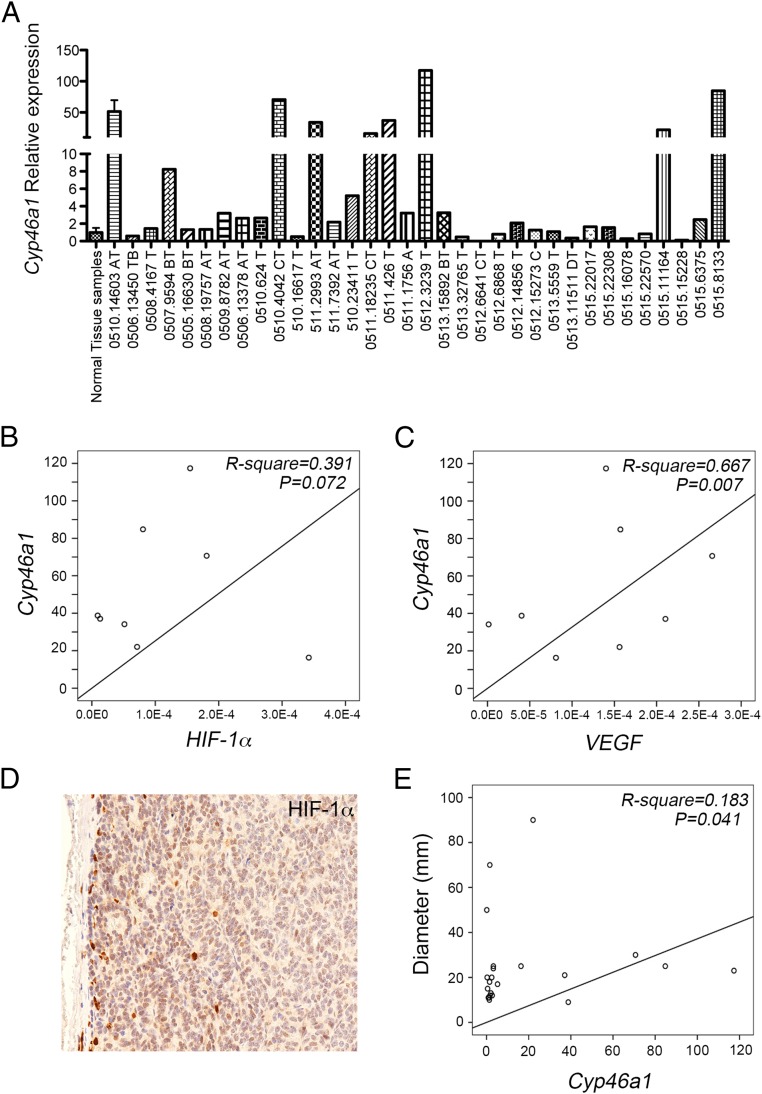

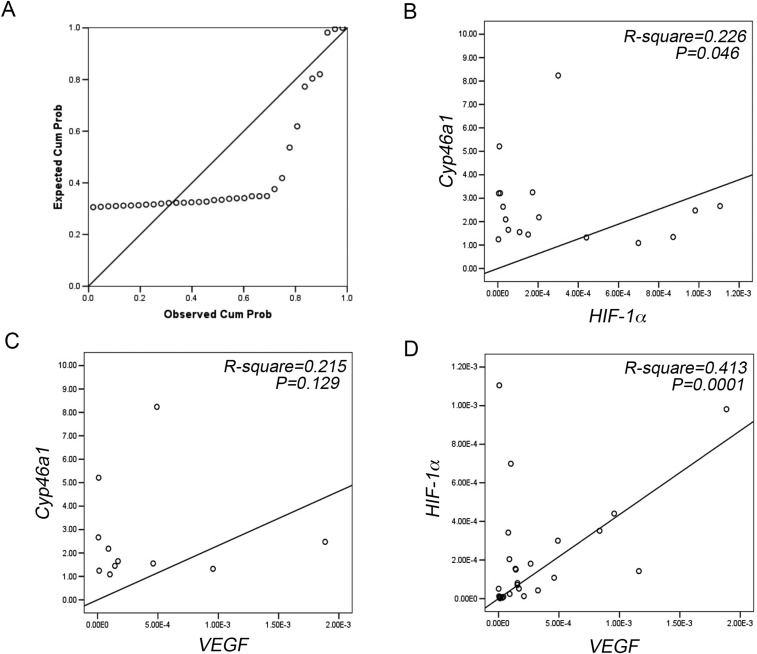

Finally, we investigated whether Cyp46a1 was also expressed in human pNETs and whether a link among Cyp46a1, VEGF, and HIF-1α expression was present in human pNETs. The distribution of Cyp46a1 expression is shown in Fig. 6A, with median, minimum, and maximum values being 2.137, 0.165, and 117.367, respectively. As Cyp46a1 expression values in eight specimens were far from a normal distribution, they were grouped together (i.e., “high expressors,” relative expression >10); remaining values were divided into two groups (<1 and ≥1) according to the relative Cyp46a1 mRNA expression above or below that of normal samples (P-P plot; Fig. S8A). We then performed linear regression analyses to evaluate the association between Cyp46a1 and HIF-1α or Cyp46a1 and VEGF in the above-reported three groups. We did not find any statistical association between Cyp46a1 and HIF-1α or Cyp46a1 and VEGF in the <1 group (P = 0.308 and P = 0.215, respectively). We found only a trend in the >1 group both for HIF-1α and VEGF (Fig. S9 B and C), which failed to achieve significance. We found a trend between Cyp46a1 and HIF-1α (Fig. 6B; R2 = 0.391, P = 0.072, n = 8) and a significant association between Cyp46a1 and VEGF in the high expressors group (Fig. 6C; R2 = 0.667, P = 0.007, n = 8). We also detected HIF-1α protein by immunohistochemistry in one available pNET sample in the high expressors group (i.e., 0511.2993AT; Fig. 6D), thus corroborating the results obtained at mRNA levels. As expected, we found a significant association between HIF-1α and VEGF (Fig. S7D). Because most pNET samples overexpressing Cyp46a1 transcripts were grade 1 (G1) (Table S1), we analyzed a possible correlation between tumor diameter and Cyp46a1 expression in 22 patients affected by G1 pNETs. We found a correlation between tumor diameter and Cyp46a1 overexpression (Fig. 6E; R2 = 0.183, P = 0.042, n = 22). Altogether, these results suggest a possible role of Cyp46a1 also in human pNET tumorigenesis. In the near future, we will investigate the correlation between Cyp46a1 and HIF-1α at mRNA and protein levels on a larger cohort of pNET patients and will define the role of Cyp46a1 overexpression in human pNETs to establish whether this overexpression correlates with tumor progression and metastasis or with response to therapy in pNET patients.

Fig. 6.

Expression of Cyp46a1, HIF-1α, and VEGF transcripts by human pNET samples and correlation studies. (A) qPCR analysis for the expression of Cyp46a1 mRNA in human pNET samples. (B and C) Linear regression analyses between Cyp46a1 expression and HIF-1α (Β) or VEGF expression (C). (D) Immunohistochemistry for HIF-1α in a pNET sample in the “high expressors” group. Original magnification, 200×. (E) Linear regression analyses between Cyp46a1 expression and tumor diameter.

Fig. S9.

(A) P-P plot analysis showing abnormal distribution of Cyp46a1 expression in eight samples. (B and C) Linear regression analyses between Cyp46a1 and HIF-1α expression (B) and Cyp46a1 and VEGF expression (C) in the >1 Cyp46a1 relative expression group. Linear regression analyses show only a trend of correlation in both groups. (D) Linear regression analysis between HIF-1α and VEGF expression.

Table S1.

Clinical features of analyzed pNET samples

| pNET sample | Grade | Diameter | Hormone production |

| 0511.426.T | G1 | 2.1 | Insulin |

| 0511.1756A | G1 | 2.4 | NF |

| 0511.18235C | G1 | 2.5 | Insulin/Glucagon |

| 0512.6641C | G3 NEC | 6.0 | NF |

| 0510.14603A | G1 | 0.9 | NF |

| 0510.16617T | G1 | 1.5 | Insulin |

| 0511.2993AT | G2 | 6.5 | NF |

| 0511.7392AT | G2 | 8.0 | NF |

| 0512.6868AT | G2 | 1.7 | NF |

| 0510.23411T | G1 | 1.7 | NF |

| 0506.13450TB | G2 | 10 | NF |

| 0508.4167T | G1 | 1.8 | Insulin |

| 0507.9584 | G2 | 7.0 | NF |

| 0505.16630BT | G2 | 10 | NF |

| 0508.19757AT | G1 | 1.0 | NF |

| 0509.8782AT | G2 | 2.5 | NF |

| 0506.13378AT | G2 | NF | |

| 0510.624T | G1 | 1.2 | NF |

| 0510.4042CT | G1 | 3.0 | NF |

| 0512.3239T | G1 | 2.3 | NF |

| 0512.14856T | G1 | 1.3 | Somatostatin |

| 0512.15273C | G1 | 1.1 | NF |

| 0513.5559T | G2 | 1.9 | NF |

| 0513.11511DT | G2 | 7.0 | NF |

| 0513.15892BT | G1 | 2.5 | Glucagon |

| 0513.32765T | G2 | 10 | NF |

| 0515.22017 | G1 | 1.2 | Insulin |

| 0515.22308 | G1 | 7.0 | NF |

| 0515.16078 | G1 | 2.0 | NF |

| 0515.8133 | G1 | 2.5 | NF |

| 0515.22570 | G1 | 1.1 | Insulin |

| 0515.11164 | G1 | 9.0 | NF |

| 0515.15228 | G1 | 5.0 | NF |

| 0515.6375 | G1 | 2.0 | NF |

N,: nonfunctioning; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Discussion

The role of oxysterols and LXRs in tumor development and progression is greatly debated due to contrasting evidence possibly related to the multiple roles played by oxysterols and LXRs within the tumor microenvironment (9, 10, 12). The different outcomes observed following the treatment of tumors with molecules stimulating or interfering with LXR/LXR ligands should take into account the tumor models used, the presence of an intact immune system, the distinct isoforms of LXRs engaged, and the intrinsic biologic ability of oxysterols to bind receptors different from LXRs (12, 35). Therefore, appropriate models dissecting how LXR/LXR ligands operate within the tumor microenvironment are required. We recently studied the function of LXR/oxysterols during the growth of transplantable mouse tumors and observed that they exert protumoral functions through neutrophils recruitment and induction of an angiogenic switch (14).

Here, we analyzed the role of oxysterols in spontaneous tumor models, in particular during the development of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in RIP1-Tag2 mice. We show that during pNET tumorigenesis the transcript encoding the Cyp46a1 enzyme is specifically up-regulated. This up-regulation occurs concomitantly to the onset of tumor hypoxia in transformed islets of RIP1-Tag2 pancreata and increased expression of bona fide HIF-1α target genes Vegf and Pkm2. PKM2 is activated during aerobic glycolysis and regulates the production of pyruvate and lactate, which have been described to stabilize HIF-1α through hypoxia-independent mechanisms in a self-enforcing circle (6, 36). We find that Cyp46a1 is an HIF-1α target gene, as stabilized HIF-1α binds HREs in the Cyp46a1 promoter in a pNET-derived cell line. Increased expression of Cyp46a1 leads to increased synthesis of the oxysterol 24S-HC in transformed RIP1-Tag2 islets, concomitantly with the expression of other bona fide HIF-1α target genes involved in angiogenesis and metabolic adaptation. In addition, consistently with previous results, 24S-HC accumulation leads to the positioning of neutrophils close to hypoxic regions that require formation of neo-vessels.

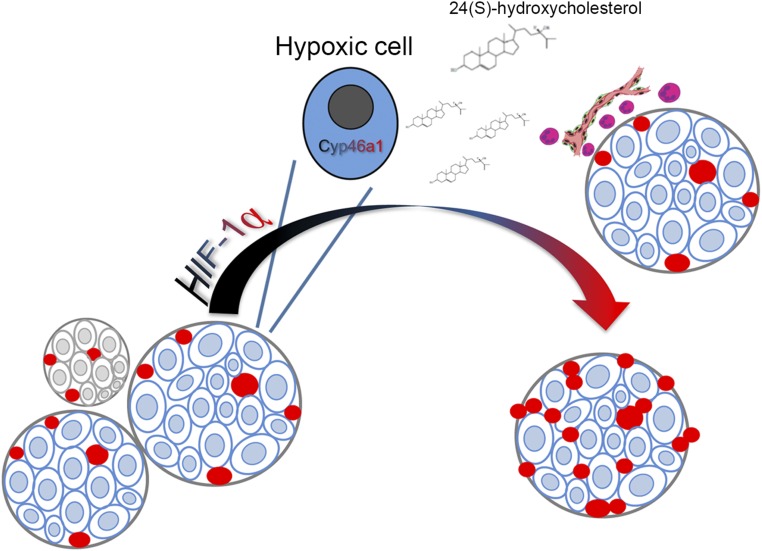

With our work, we identify a mechanism leading to oxysterols accumulation in tumors, and we position oxysterols synthesis downstream HIF signaling in tumors. These findings unveil a complex network leading to tumor angiogenesis in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: on one hand, HIF-1α up-regulation leads to VEGF transcription and direct induction of neoangiogenesis; on the other hand, 24S-HC accumulation and neutrophils recruitment further supports neovessels formation (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of the mechanism linking HIF-1α, 24S-HC, and neutrophils in the pNET angiogenic switch. In hyperplastic islets, HIF-1α induces the overexpression of Cyp46a1 enzyme, which in turn produces the oxysterol 24S-HC that positions neutrophils in close proximity to hypoxic areas, thus favoring the angiogenic switch.

The importance of oxysterol accumulation in this tumor model was demonstrated by pharmacological and genetic studies. RIP1-Tag2 mice treated with the squalene synthase inhibitor ZA showed a significant reduction of proangiogenic neutrophils and angiogenic islets, confirming the previously described link between cholesterol metabolism and neutrophil-mediated angiogenesis (14). Moreover, the involvement of oxysterols, specifically 24S-HC, in neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis is further corroborated by the results obtained in a transgenic mouse model in which the enzyme SULT2B1b is expressed constitutively by pancreatic islets. The choice of this transgenic model is based upon the possibility to inactivate all of the oxysterols generated within the microenvironment of RIP1-Tag2 pNET, including those produced by nonradical reactive oxygen species or by inorganic free radical species (37). Double transgenic mice displayed a delay in pNET tumorigenesis development (reduced number of angiogenic and tumor islets), which was independent of intrinsic effects (apoptosis and/or proliferation), whereas it was correlated with the reduced percentage of proangiogenic neutrophils infiltrating transformed islets.

Angiogenic switch in the RIP1-Tag2 pNET model has been closely correlated to MMP-9+- and Bv8-releasing neutrophils (19, 20). In this context, we observed that decreased 24S-HC accumulation accompanied reduced numbers of neutrophils in pancreata of double transgenic mice compared with RIP1-Tag2 mice, whereas we detected similar expression of transcripts encoding CXCR2-driven chemokines, such as Cxcl1, Cxcl2, and Cxcl5, usually involved in neutrophil migration (38). These results along with the observations that neutrophils are found close to cells of transformed islets overexpressing Cyp46a1 and that 24S-HC was shown to induce neutrophil migration in vitro (14) reinforce the idea that 24S-HC oxysterol might be crucially involved in vivo in the positioning of proangiogenic neutrophils in the proximity of cells releasing high amounts of 24S-HC. The concept that oxysterols may behave as short-range chemoattractants has recently been described for the oxysterol 7α, 25-HC, which controls cell positioning within specific areas of lymphoid organs (39). The positioning role of 24S-HC in physiologic conditions deserves further investigations.

Because ZA-treated mice and double transgenic mice showed only a delay of the tumorigenic process (reduced angiogenic and tumor islets), it is likely that other mechanisms concur to the development of pNET tumorigenesis or that compensatory mechanisms occur during the course of the treatments.

Recent findings that some molecular and metabolic features of human pNETs are also present in the RIP1-Tag2 model makes our observations clinically relevant (40). This observation is further corroborated by our preliminary results showing Cyp46a1 overexpression in some human pNET samples and suggesting a linear correlation among Cyp46a1, VEGF, and tumor diameter in G1 pNET patients. This model could represent a useful tool to test combination therapies of drugs currently used in pNET patients and cholesterol-lowering compounds endowed with a well-established pharmacologic profile (e.g., statins) (41).

Altogether, these results reveal an early mechanism underlying the angiogenic switch responsible for the subsequent tumor stage progression in the pNET model RIP1-Tag2. Moreover, these results provide the basis for the exploitation of compounds endowed with a similar mechanism of action for antitumor therapies.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Models and Treatments.

RIP1-Tag2 mice were maintained on the C57BL/6N background (Charles River). To obtain RIP1-Tag2 × RIP1-SULT2B1b double transgenic mice, RIP1-Tag2 males were crossed with RIP1-SULT2B1b females. Offsprings were tested by PCR for both the transgenes using the following primers: forward, gctctgctgacatagaagaatgg; reverse, gtactcattcatggtgactattccag. Five-week old RIP1-Tag2 mice were treated with ZA A (Sigma Aldrich) with alternating i.v. (200 μg/mouse) and i.p. (100 μg/mouse) infusions. Islet analyses were carried out after 3 wk of treatment. Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the San Raffaele Scientific Institute.

Generation of the RIP1-SULT2B1b Transgenic Mouse Model.

RIP1-Timer plasmid (Addgene plasmid #15109, DM#285) was linearized by NotI. DsRed1-E5 cDNA was replaced with SULT2B1b cDNA, obtained by PCR using the In-Fusion PCR cloning kit (Clontech Laboratories). Primers to clone SULT2B1b from SULT2B1b-ΔNGFr lentiviral vector (42) were designed according to In-Fusion kit instructions. HbaI linearized plasmid was then microinjected into donor FVB pronuclei and subsequently transplanted in pseudopregnant acceptor CD1 mice. Transgenic mice were generated by our Institutional CFCM facility. RIP1-SULT2B1b founders were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for five generations. pNET analysis was performed in F4/F5 double transgenic mice. RIP1-SULT2B1b mice were typed with the following primers: RipSult FW 5′-gggaatgatgtggaaaaatg-3′ and RipSultREV 5′-gcacgttgctagtgttctca-3′.

ChIP Assay.

Harvested cells were fixed for 10 min at room temperature with 1% formaldehyde. Cross-linking was terminated by the addition of 125 mM glycine. Cells were rinsed with PBS and centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Pellets were resuspended in 50 nM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% Triton X-100, and leupeptin-pepstatinA-aprotinin at 5 μg/mL (pH 8.1). Nuclei were collected by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C), resuspended in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, and leupeptin-pepstatinA-aprotinin at 5 μg/mL (pH 8.1), and rotated for 10 min at 4 °C. Washed nuclei were centrifuged, resuspended in 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 0.5% N-sauroylsarconsin, and leupeptin-pepstatinA-aprotinin at 5 μg/mL (pH 8.1), and then sonicated to generate DNA fragment sizes of 0.2–0.8 kb, using the Diagenode Bioruptor twin (20 cycles, 30 s on/off, maximum power). Samples were cleared by centrifugation at 16,100 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Ten percent of the cleared supernatant was used as input, and the remaining volume was immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal antibody anti–HIF-1α (Clone H1α67; Novus Biologicals). Quantification of the precipitated DNA regions was performed by qPCR (Table S2).

Table S2.

List of primers used in this study

| Transcripts | Primers for qPCR (syber-green) |

| mCyp7b1 FWD | TCAGGAAAGGCAAGATCTGCTGA |

| mCyp7b1 REV | CCTGTTGACTGCAGGAAACTGTCA |

| mCyp11a1 FWD | AACATCCAGGCCAACATTAC |

| mCyp11a1 REV | GGTCATGGAGGTCGTGTC |

| mCh25h FWD | CTGCCTGCTGCTCTTCGACA |

| mCh25h REV | CCGACAGCCAGATGTTAATCA |

| mCyp27a1 FWD | GACCTCCAGGTGCTGAAC |

| mCyp27a1 REV | CTCCTGTCTCATCACTTGCTC |

| mCyp46a1 FWD | GTGTGCTCCAAGATGTGTTTCT |

| mCyp46a1 REV | ACACAGTCTGAAGCGCGCGGT |

| Stard1 FWD | TCTCTGCTTGGTTCTCAACTG |

| Stard1 REV | CCTTCCTGGTTGTTGAGTATG |

| mRPL13a FWD | TCAAGGTTGTTCGGCTGAAG |

| mRPL13a REV | GCCCCAGGTAAGCAAACTTT |

| mHIF1a inducible FWD | AATACATTTTCTCTGCCAGTTTTCTG |

| mHIF1a inducible REV | TTGCTGCATCTCTAGACTTTTCTTTT |

| mPkm2 FWD | AGGATGCCGTGCTGAATG |

| mPkm2 REV | TAGAAGAGGGGCTCCAGAGG |

| mCXCL1 FWD | CTGGGATTCACCTCAAGAACATC |

| mCXCL1 REV | CAGGGTCAAGGCAAGCCTC |

| mCXCL2 FW | CACCAACCACCAGGCTACA |

| mCXCL2 REV | GCTTCAGGGTCAAGGCAAAC |

| mCXCL5 FW | GCTGCCCCTTCCTCAGTCAT |

| mCXCL5 REV | CACCGTAGGGCACTGTGGAC |

| mCCL2 FWD | AGGTGTCCCAAAGAAGCTGTA |

| mCCL2 REV | ATGTCTGGACCCATTCCTTCT |

| mCXCR4 FWD | TTGTCCACGCCACCAACAGTCA |

| mCXCR4 REV | TGAAACACCACCATCCACAGGC |

| mCCR7 FWD | CACGCTGAGATGCTCACTGG |

| mCCR7 REV | CCATCTGGGCCACTTGGA |

| mIFNg FWD | ATGAACGCTACACACTGCATC |

| mIFNg REV | CCATCCTTTTGCCAGTTCCTC |

| mIL13 FWD | GCAACATCACACAAGACCAGA |

| mIL13 REV | GTCAGGGAATCCAGGGCTAC |

| mIL2 FWD | TGAGCAGGATGGAGAATTACAGG |

| mIL2 REV | GTCCAAGTTCATCTTCTAGGCAC |

| mIL10 FWD | CTGGACAACATACTGCTAACCG |

| mIL10 REV | GGGCATCACTTCTACCAGGTAA |

| mIL1b FWD | GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT |

| mIL1b REV | ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT |

| mTGFb FWD | CGGCAGTGGCTGAACCAAGGA |

| mTGFb REV | CGTTTGGGGCTGATCCCGTTGA |

| hCyp46a1 FWD | AAGAAGTTCCTGATGTCAACCA |

| hCyp46a1 REV | ACTCTCCGCTGCTTGTGCCAGC |

| hGAPDH FWD | ACATCATCCCTGCCTCTACTG |

| hGAPDH REV | ACCACCTGGTGCTCAGTGTA |

| ChIP primers | |

| Cyp46p HRE FWD | GCCAGGTTGTGATTGGTGAATAC |

| Cyp46p HRE REV | CCTCCAGCCCTAGCTCTCAG |

| Cyp46 CTR FWD | CCCTCCAGGACCTAACCAAG |

| Cyp46 CTR REV | AGTGCTCCTCACTTCCGAGTTTC |

Statistical Analysis.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed for significance by ANOVA with Dunnet’s, Bonferroni’s, or Tukey’s multiple comparison test, by ANOVA with Pearson correlation, or by Student t test. The analysis was performed with Prism software.

SI Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

βTC3, RMA, and 4T1 cell lines were grown in RPMI, 10% (vol/vol) FBS. 3T3 and LLC were grown in DMEM, 10% (vol/vol) FBS. Tumor cell lines were transduced by pGIPZ shCNTR and shHIF1α vectors. βTC3 cells expressing the mutant stable form of HIF1α were obtained by taking advantage of a lentiviral vector encoding the mutant stable form as previously described (34). Hypoxic conditions were obtained by using an InVivO2 300 incubator (Baker Ruskinn) set to 1% O2; 5% (vol/vol) CO2. Cells in hypoxia and relative controls medium were supplemented with 2% Hepes (GIBCO) to buffer any variation in CO2 percentage.

Recovery of Normal and Transformed Islets.

Pancreatic ducts were exposed, and the ampulla of Vater was occluded using vessel-sealing forceps. We injected 2.5 mL of a solution containing collagenase IV (0.7 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), DNase (20 ng/mL; Roche), and Dispase (1.8 U/mL; Gibco) in RPMI, through the pancreatic duct using a 30- to 32-gauge needle. Pancreata were then recovered and put in 5 mL enzymatic solution for 10–20 min at 37 °C in a rotating rack. Islets in suspension were washed with PBS selected and counted, as described in ref. 43. In particular, we defined as tumor islets those with a diameter superior to 1 mm. Angiogenic islets were identified as those that exhibited a red hemorrhagic appearance with a diameter inferior to 1 mm. Hyperplastic and WT islets were identified by staining with Dithizone (Sigma-Aldrich).

Purification of CD45+ and CD45− Cells from Tumor Islets.

To obtain a single cell suspension, islets and tumors were cut (when needed) into small fragments and digested for 45–60 min at 37 °C with a 1.4 mg/mL collagenase A, B, and D (Roche) mixture in RPMI medium containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS. Cell suspension of tumors from 10-wk-old RIP1-Tag2 mice were pooled and stained with anti–CD45-PE antibody and anti-PE MicroBeads (Miltenyi). Purified CD45-positive and -negative cells were then collected and further processed.

RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and qPCR Analysis.

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) for in vivo samples or TRIzol (Invitrogen) for cell lines. Genomic DNA (gDNA) digestion, using the RNase free DNase set (Qiagen) or DNA-free DNA removal kit (Ambion), was mandatory for Ch25h analysis. Reverse transcription was performed with 1–2 μg total RNA using Moloney leukemia virus (MLV)-RT (Promega). RNA obtained from CD45+ and CD45− cells was retrotranscribed and amplified with the QuantiTect whole transcriptome kit (Qiagen). We performed qRT-PCR using TaqMan Gene Expression assay (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for Hif1α (Mm00468869_m1), Vegf (Mm01281449_m1), and mRPL13a (Mm01612987_g1). We analyzed the other targets using SyberGreen technology with custom primers for StarD1, Ch25h, Cyp7b1, Cyp11a1, Cyp27a1, and Cyp46a1 (Table S2).

qPCR Analysis of Human pNETs for Cyp46a1, VEGF, and HIF-1α.

Human pNET samples were obtained by the Pathology Unit of San Raffaele Scientific Institute following written informed consent. Total RNA was extracted as reported above. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR analysis were carried out as reported above. We analyzed Cyp46a1, VEGF, and HIF-1α expression by using human primers, as described in Table S2. For Cyp46a1 analysis, 2-ΔCt data were first normalized based on average target expression (to reduce interexperimental variability) and then on normal tissue expression. Cyp46a1 expression was analyzed using SyberGreen technology with custom primers (Table S2). We performed qPCR using TaqMan Gene Expression assay (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for HIF-1α (Hs00936371_m1), VEGFA (Hs00173626_m1), and 18S (Hs03003631_g1).

Cyp46a1, VEGF, and HIF-1α Analysis on Human Samples.

Values of Cyp46a1 from each sample are shown in a bar chart (Fig. 6A). Median, minimum, and maximum values were 2.137, 0.165, and 117.367 respectively. Because the eight upper specimens exhibited values far from a normal distribution, they were grouped together (i.e., “high expressors,” relative expression >10); remaining values were divided into two groups (<1 and ≥1) according to the Cyp46a1 relative expression above and below that of the normal samples. The regression analyses provided the correlation coefficient (R2) together with corresponding P value and number of subjects. All analyses were computed using SPSS v13.0 for Windows.

FACS Analysis and Antibodies.

Single cell suspensions from pancreatic islets were washed and labeled with Live/Dead fixable near-IR Dead Cell Stain (Life Technologies) for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing, the cells were incubated for 5 min at room temperature with Fc 10 μg/mL mouse Fc Block (BD Biosciences) in PBS and labeled with anti-CD45.2 PacificBlue, Ly6G-FITC, anti-CD11b PerCP, and anti–CD31-PE (BioLegend). To quantify neutrophils in peripheral blood of mice, blood was collected in heparinized tubes. Red blood cells were lysed with with RBC Lysis Buffer (Biolegend) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Cells were stained with anti-CD45.2 FITC, anti–CD11b-PE, anti–Ly6G-PerCPCy5.5, and anti–Ly6C-PECy7 (BioLegend). Samples were run on a Canto II flow cytometer (BD) and analyzed by FlowJo software, gating on live cells.

Immunofluorescence.

Pancreata were fixed overnight in 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution followed by graded sucrose (10%–20%–30%; vol/vol) over the next 3–4 d. The samples were then embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Teck), frozen by cold fumes generated by dry ice, and stored at −80 °C. Samples were sectioned using a Leica cryostat. Pancreata were cut into 10-μm-thick sections; cryostatic sections were washed in PBS for 10 min and then blocked for 1 h with 10% (vol/vol) FBS in PBS containing 5% (vol/vol) BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies (Abs) diluted in blocking solution. We used the following antibodies: rabbit anti-Cyp46A1 (Sigma-Aldrich) and rat anti-Gr1 (clone RB6-8CS; BD Pharmingen). Secondary antibodies were anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488/Alexa Fluor 568 and anti-rat Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images were acquired with an AxioImager M2m (Zeiss).

Immunohistochemistry and Quantification by Aperio.

Eight-week-old RIP1-Tag2 mice were injected i.p. with 2 mg pimonidazole (PIMO) HCl (Hypoxyprobe) to reveal hypoxic areas. After 1 h, mice were killed, and pancreata were collected and analyzed for pimonidazole staining. Pimonizadole adducts were detected with the Hypoxyprobe TM-1 Plus kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, deparaffinized and rehydrated slides were pretreated with pronase (5 min at room temperature), followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated mAb-1 (1 h), and incubation with HRP-linked anti-FITC rabbit antibody (30 min), and then developed with DAB with H2O2 and counterstained with hematoxylin. Extensive buffer washing followed all of the steps indicated above. For CCL3 and Ki67 staining, deparaffinized and rehydrated slides were pretreated with 10 mM Tris–1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0, solution for antigen retrieval and, after quenching with endogenous peroxidase with 3% (vol/vol) H2O2, incubated with cleaved caspase-3 diluted 1/100 (Cell Signaling) or with Ki67 diluted 1/400 (Cell Signaling). The reaction was visualized using an anti-rabbit on rodent HRP polymer kit (Biocare RMR622) and developed with DAB and H2O2 as chromogen. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Immunostained slides were scanned using the Aperio Scan Scope instrument (Leica-Microsystems). CCL3 and Ki67 staining was analyzed with the AperioImageScope Nuclear Alghoritm version 9, after selecting islets and excluding the exocrine component. A minimum of 10 islets per pancreas was analyzed, and the percentage of positive stained cells, recorded in the Aperio Spectrum database, was used for statistical analysis. Immunohistochemistry of human pNET samples was performed using rabbit monoclonal anti–HIF‐1α (clone EP1215Y; Abcam) antibodies. Antigen retrieval was performed using Tris-EDTA, pH 9.0, at 95 °C for 30 min and the nonbiotin polymer UV Quanto HRP-DAB Detection Kit (ThermoFisher).

Oxysterol Quantification.

Oxysterols were prepared from tissues using a modified version of the protocol described by Griffiths et al. (44), consisting in an alcoholic extraction and a double round of reverse-phase (RP) solid-phase extraction (SPE). Briefly, pancreata were homogenized in ice cold PBS using a TissueLyser (QIAGEN). Four hundred to 500 mg tissue was put in a 2-mL test tube with two stainless steel beads and 1 mL ice-cold PBS, and then homogenized at 30 freq/s for 3 min. The tissue debris were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C; 20 pmol of each deuterated standard was spiked into each sample before further processing. Proteins were precipitated with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol followed by a centrifugation for 30 min at 14,000 × g at 4 °C. The raw extract was applied to a preconditioned Sep-Pak tC18 cartridge. The oxysterol-containing flow-through was collected, together with the first 70% (vol/vol) ethanol wash. The collected oxysterols were vacuum-evaporated and reconstituted in 100% (vol/vol) isopropanol, diluted in 50 mM phosphate buffer, and oxidized by cholesterol oxidase addition. The reaction was stopped by methanol. Reactive oxysterols were then derivatized by Girard P reagent and further purified by reverse phase chromatography using a Sep-Pak tC18 cartridge to eliminate the excess of GirardP reagent. Purified oxysterols were diluted in 60% (vol/vol) methanol and 0.1% formic acid. Eight microliters of sample was resolved by nano-HPLC on a reverse phase C18, using a 12-min gradient from 20% to 100% of solvent B [63.3% (vol/vol) methanol, 31.7% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid], where solvent A is composed of 33.3% methanol, 16.7% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid. Eluting oxysterols were acquired on a QExactive mass spectrometer (Thermo), where the survey spectrum was recorded at high resolution (R = 140,000 @200 m/z) and the five most intense peaks were further fragmented to check for reporter ions such as the known −79- and −107-Da neutral losses. The identification of the oxysterols species was made by comparing the retention times of the analytes with those of the synthetic, deuterated standards previously run on the same system in the same chromatographic conditions. The quantification was achieved by means of stable-isotope dilution MS using internal standards. The total ion current for derivatized oxysterols was extracted for each acquisition, areas of the peaks were integrated manually using Xcalibur software, and the absolute amount of oxysterols was determined by comparing their areas with those of the internal standards, using the following equation:

Western Blot Analysis.

Lysates were prepared in Tris 10 mM, pH 8.0, NaCl 150 mM, Nonidet P-40 1%, SDS 0.1%, EDTA 10 mM, and protease inhibitors (Complete, EDTA free; Roche) and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. For Western blot analyses, equal amounts of proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE and transferred onto Immobilon-P (Millipore). After Ponceau S staining, membranes were saturated in Tris⋅HCl 20 mM, pH 7.6, NaCl 150 mM (Tris-buffered saline) containing nonfat milk 5% (wt/vol), and Tween 20 0.1%. Antigens were detected using mouse monoclonal anti-Cyp46a1 (kindly provided by David W. Russell, Departments of Molecular Genetics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) (45) rabbit polyclonal anti–HIF‐1α (Novus Biologicals NB 100-134), and mouse monoclonal anti-actin (Purified Mouse Anti-Actin Ab-5; BD Biosciences) antibodies. Primary antibodies were revealed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences) and a chemiluminescence kit (ECL; Amersham Biosciences). Concerning Western blot analyses for HIF-1α in hypoxic βTC3 cells, nuclear extract was prepared as follows: cells were resuspended in the cell lysis buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 8, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet‐40, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and the protease inhibitors] and allowed to swell on ice for 15–20 min with intermittent mixing. Eppendorf tubes were then centrifuged at 700 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The pelleted nuclei were washed twice with the cell lysis buffer and then resuspended in the RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors. Nuclear extracts were collected by centrifugation at 13,400 × g for 15 min at 4 °C.

Acknowledgments

Anti-Cyp46a1 mAb was a generous gift of Dr. David W. Russell (Departments of Molecular Genetics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center). We thank Elena Tiziano, Simona Porcellini, and Claudia Asperti for technical help and Lorenzo Piemonti and Valeria Corti for providing mRNA from donor-derived pancreatic islets. This work was supported from the Italian Association for Cancer Research Grants IG 12876 and IG 15452 (to V.R. and C.B.) and from the Italian Ministry of Health Grant RF2009 (to V.R.). M.S. was supported by grants from the Association International for Cancer Research, UK. J.-Å.G. was supported by the Swedish Research Council and by grants from the Robert A. Welch Foundation (E-0004).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1613332113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(2):85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBerardinis RJ, Thompson CB. Cellular metabolism and disease: What do metabolic outliers teach us? Cell. 2012;148(6):1132–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bensaad K, Harris AL. Hypoxia and metabolism in cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;772:1–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-5915-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semenza GL. HIF-1 mediates metabolic responses to intratumoral hypoxia and oncogenic mutations. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(9):3664–3671. doi: 10.1172/JCI67230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villalba M, et al. From tumor cell metabolism to tumor immune escape. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(1):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colegio OR, et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 2014;513(7519):559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christofk HR, et al. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 2008;452(7184):230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin CY, Gustafsson JA. Targeting liver X receptors in cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(4):216–224. doi: 10.1038/nrc3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bovenga F, Sabbà C, Moschetta A. Uncoupling nuclear receptor LXR and cholesterol metabolism in cancer. Cell Metab. 2015;21(4):517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bensinger SJ, Tontonoz P. Integration of metabolism and inflammation by lipid-activated nuclear receptors. Nature. 2008;454(7203):470–477. doi: 10.1038/nature07202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traversari C, Sozzani S, Steffensen KR, Russo V. LXR-dependent and -independent effects of oxysterols on immunity and tumor growth. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44(7):1896–1903. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spann NJ, Glass CK. Sterols and oxysterols in immune cell function. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(9):893–900. doi: 10.1038/ni.2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raccosta L, et al. The oxysterol-CXCR2 axis plays a key role in the recruitment of tumor-promoting neutrophils. J Exp Med. 2013;210(9):1711–1728. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanahan D. Heritable formation of pancreatic beta-cell tumours in transgenic mice expressing recombinant insulin/simian virus 40 oncogenes. Nature. 1985;315(6015):115–122. doi: 10.1038/315115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergers G, Javaherian K, Lo KM, Folkman J, Hanahan D. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on multistage carcinogenesis in mice. Science. 1999;284(5415):808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folkman J, Watson K, Ingber D, Hanahan D. Induction of angiogenesis during the transition from hyperplasia to neoplasia. Nature. 1989;339(6219):58–61. doi: 10.1038/339058a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergers G, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(10):737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nozawa H, Chiu C, Hanahan D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(33):12493–12498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601807103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shojaei F, Singh M, Thompson JD, Ferrara N. Role of Bv8 in neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis in a transgenic model of cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(7):2640–2645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712185105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Björkhem I. Do oxysterols control cholesterol homeostasis? J Clin Invest. 2002;110(6):725–730. doi: 10.1172/JCI16388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell DW. Oxysterol biosynthetic enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1529(1-3):126–135. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Efrat S, et al. Beta-cell lines derived from transgenic mice expressing a hybrid insulin gene-oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(23):9037–9041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergstrom JD, et al. Zaragozic acids: A family of fungal metabolites that are picomolar competitive inhibitors of squalene synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(1):80–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuda H, Javitt NB, Mitamura K, Ikegawa S, Strott CA. Oxysterols are substrates for cholesterol sulfotransferase. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(6):1343–1352. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700018-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falany CN, Rohn-Glowacki KJ. SULT2B1: Unique properties and characteristics of a hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase family. Drug Metab Rev. 2013;45(4):388–400. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2013.835609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drechsler M, Megens RT, van Zandvoort M, Weber C, Soehnlein O. Hyperlipidemia-triggered neutrophilia promotes early atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1837–1845. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.961714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren S, Ning Y. Sulfation of 25-hydroxycholesterol regulates lipid metabolism, inflammatory responses, and cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306(2):E123–E130. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00552.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86(3):353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Görlach A. Regulation of HIF-1alpha at the transcriptional level. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(33):3844–3852. doi: 10.2174/138161209789649420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenger RH, Rolfs A, Spielmann P, Zimmermann DR, Gassmann M. Mouse hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is encoded by two different mRNA isoforms: Expression from a tissue-specific and a housekeeping-type promoter. Blood. 1998;91(9):3471–3480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo W, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a PHD3-stimulated coactivator for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;145(5):732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semenza GL. HIF-1: Upstream and downstream of cancer metabolism. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guarnerio J, et al. Bone marrow endosteal mesenchymal progenitors depend on HIF factors for maintenance and regulation of hematopoiesis. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;2(6):794–809. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cyster JG, Dang EV, Reboldi A, Yi T. 25-Hydroxycholesterols in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(11):731–743. doi: 10.1038/nri3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu H, Forbes RA, Verma A. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation by aerobic glycolysis implicates the Warburg effect in carcinogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(26):23111–23115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202487200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy RC, Johnson KM. Cholesterol, reactive oxygen species, and the formation of biologically active mediators. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):15521–15525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700049200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim ND, Luster AD. The role of tissue resident cells in neutrophil recruitment. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(9):547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi T, et al. Oxysterol gradient generation by lymphoid stromal cells guides activated B cell movement during humoral responses. Immunity. 2012;37(3):535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadanandam A, et al. A Cross-Species Analysis in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Reveals Molecular Subtypes with Distinctive Clinical, Metastatic, Developmental, and Metabolic Characteristics. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(12):1296–1313. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Statin use and reduced cancer-related mortality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1792–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villablanca EJ, et al. Tumor-mediated liver X receptor-alpha activation inhibits CC chemokine receptor-7 expression on dendritic cells and dampens antitumor responses. Nat Med. 2010;16(1):98–105. doi: 10.1038/nm.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parangi S, Dietrich W, Christofori G, Lander ES, Hanahan D. Tumor suppressor loci on mouse chromosomes 9 and 16 are lost at distinct stages of tumorigenesis in a transgenic model of islet cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1995;55(24):6071–6076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffiths WJ, et al. Analytical strategies for characterization of oxysterol lipidomes: Liver X receptor ligands in plasma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;59:69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramirez DM, Andersson S, Russell DW. Neuronal expression and subcellular localization of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase in the mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2008;507(5):1676–1693. doi: 10.1002/cne.21605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]