Abstract

The cholesterol synthesis inhibitor simvastatin, which is used to treat cardiovascular diseases, has severe collateral effects. We decided to comprehensively study the effects of simvastatin in zebrafish development and in myogenesis, because zebrafish has been used as a model to human diseases, due to its handling easiness, the optical clarity of its embryos, and the availability of physiological and structural methodologies. Furthermore, muscle is an important target of the drug. We used several simvastatin concentrations at different zebrafish developmental stages and studied survival rate, morphology, and physiology of the embryos. Our results show that high levels of simvastatin induce structural damage whereas low doses induce minor structural changes, impaired movements, and reduced heart beating. Morphological alterations include changes in embryo and somite size and septa shape. Physiological changes include movement reduction and slower heartbeat. These effects could be reversed by the addition of exogenous cholesterol. Moreover, we quantified the total cell number during zebrafish development and demonstrated a large reduction in cell number after statin treatment. Since we could classify the alterations induced by simvastatin in three distinct phenotypes, we speculate that simvastatin acts through more than one mechanism and could affect both cell replication and/or cell death and muscle function. Our data can contribute to the understanding of the molecular and cellular basis of the mechanisms of action of simvastatin.

Keywords: Animal model of human disease, cholesterol, muscle differentiation, cell proliferation, zebrafish embryo, simvastatin

Introduction

The cholesterol synthesis inhibitor simvastatin, which is used to treat cardiovascular diseases, causes varied collateral effects, including myotoxic consequences. We decided to comprehensively study the effects of simvastatin in zebrafish development, because zebrafish has been used as a model to human diseases.

Muscle is a highly responsive tissue, which reacts both at short term with contractions and at long term by adapting to physiological demands. Due to a great deal of research, each step in myogenesis has been studied and well characterized, particularly in cell cultures.1 Unfortunately, cell cultures are adaptations that necessarily are different from the actual in vivo situation. Studies in cell cultures lack the structural and chemical complexity of the actual in vivo development. Therefore, we, and others, have been using zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio) to study myogenesis.2–4 These embryos are transparent and undergo rapid development ex utero, allowing detailed structural analysis of muscle development as well as physiological studies both in situ and in vivo. We have previously characterized the sequence of expression and distribution of cytoskeletal, adhesion, and extracellular matrix proteins during myogenesis in this model.3

A particularly important molecule in myogenesis is cholesterol. Cholesterol has several roles in cellular metabolism. It is the key molecule of cell membrane microdomains, also called lipid rafts, which themselves have several functions in cell biology.5 At the same time, high levels of cholesterol in the blood are one of the most common causes of human heart diseases.6 We have shown that treatment of embryonic chick primary cultures of skeletal muscle cells with the compound methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MCD) enhances muscle differentiation with the involvement of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway.7–9 MCD is highly efficient in extracting cholesterol from cell membranes and thus allows the investigation of cellular and molecular mechanisms associated with cholesterol enriched-membrane microdomains disorganization. These experiments suggest that cholesterol role in myogenesis could be structural, organizing membrane microdomains, and/or in signaling.

In order to study the role of cholesterol in zebrafish myogenesis, we decided to interfere with the cells ability to synthesize its own cholesterol, using the drug simvastatin. Simvastatin is one of the most used drugs to prevent high cholesterol in humans.10 It blocks cellular cholesterol synthesis through the inhibition of the enzyme hydroxyl-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoAR). HMG-CoAR is the rate-limiting enzyme of the mevalonate pathway that leads to the endogenous production of cholesterol and isoprenoids.11 Statins are capable of lowering patient serum lipids and significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.12 Despite its advantages, it provokes undesirable side effects. Among other tissues, muscles are importantly affected with statin therapy, and statins induce myotoxic effects ranging in severity from statin-induced myopathy to potentially fatal rhabdomyolysis.13,14 The clinical manifestations of statin-associated myopathy include pain, muscle weakness, muscle cramping, soreness, fatigue and, in rare cases, rapid muscle breakdown that can lead to death.

Studies of simvastatin using zebrafish have shown that it affects myogenesis, but the studies do not follow the tissue-specific structural or physiological effects of the drug, nor they unravel their mechanisms of action. Accordingly, it was shown by Gjini et al.15 that 1-mM statin treatment causes vessel rupture and hemorrhage. Besides bleeding, no other consequence of statin treatment was described in their work. Hanai et al.16 showed that the knockdown of atrogin, an ubiquitin ligase, is capable of compensating the affected phenotype of HMG-CoA reductase knockdown and the effects of lovastatin treatment. Cao et al.17 report that the statin effects on muscle could be rescued by mevalonate and by geranylgeranol, but not by farnesol. Mevalonate is a precursor of cholesterol, but geranylgeranol is a precursor of protein prenylation and is not a cholesterol precursor. They conclude that cholesterol itself is not necessarily involved in the statin-induced myotoxicity. The hypothesis that statins do not act directly through cholesterol restriction but through prenylation is also supported by Wagner et al.18 who could dissect the pathway and isolate substances that suppress statin myopathy.

We tried to study in a more comprehensive approach the structural and physiological consequences of zebrafish simvastatin treatment, particularly on muscle development. Our results show that simvastatin, used at different developmental stages, induces important and varied alterations in zebrafish embryos, in a dose-dependent manner. We analyzed the total number of cells in the embryos and could show that the overall cell number is reduced with simvastatin, again in a dose-dependent way. Furthermore, low-dose simvastatin-treated embryos showed impaired movements and reduced heartbeat, without gross structural damage. Contributing to the understanding of the mechanism of action of the drug, we show that simvastatin effects were rescued with cholesterol treatment. These results highlight the potential use of zebrafish as an important vertebrate model for the study of cholesterol related myopathies and add to the comprehension of the mechanisms of action of the statins.

Material and methods

Zebrafish maintenance

Adult wild-type Danio rerio fish were kept in a 14-h light cycle in system water at 28℃, according to standard procedures.19 We developed our own zebrafish system, with several independent 7-L tanks, central water processing, and with mechanical, biological, and active carbon filters. Temperature was controlled by air-conditioning and water heaters. Embryos were collected from our wild-type colony, bleached with 0.05% NaOCl for 3 min and raised in system water. Fishes were from the Fish Facility in the Institute of Biomedical Sciences of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, and all the procedures were approved by the Health Sciences Center Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals in Research Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais em Pesquisa do Centro de Ciências da Saúde, CEUA-CCS, da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro [Health Sciences Center Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals in Research Federal University of Rio de Janeiro]) with the number: DAHEICB 012.

Simvastatin treatment

Embryos were dechorionated at 6 hpf (hours post-fertilization) and 11 hpf and placed in 100-mm Petri dishes filled with 50 mL of egg water (60 mg/l sea salts and 0.15% methylene blue). Embryos were treated with the following different concentrations of simvastatin: 0.3 nM, 3 nM, 6 nM, 0.375 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.75 μM, 1 μM, 2 μM, and 10 μM. Embryos were treated with simvastatin for 18 h or 13 h at 28℃ until they completed 24 hpf and then they were processed as necessary. Simvastatin was dissolved in ethanol (final concentration of 0.02%). For each treatment, we estimated the lethal concentration (LC50) as the simvastatin concentration in which 50% of the embryos were killed.

Cholesterol–low-density lipoprotein treatment

Embryos at 6 hpf were dechorionated and placed in 100-mm Petri dishes filled with 50 mL of egg water. Embryos were divided in the following four groups of treatments:

Embryos were placed in egg water only;

Embryos were placed in egg water containing 10% low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Ratio of 1:1500 molecules between LDL:cholesterol;

Embryos were placed in egg water containing 0.3 nM simvastatin;

Embryos were placed in egg water containing 0.3 nM simvastatin and 10% LDL. Ratio of 1:1500 molecules between LDL:cholesterol.

All solutions were replaced by fresh egg water when embryos completed 24 hpf. After 24 h, when embryos were 48 hpf, all groups were submitted to functional analysis.

Cholesterol measurement

Control and simvastatin-treated embryos were transferred to a phosphate-buffered saline solution with protease inhibitors: AEBSF 2 mM, aprotinin 0.3 μM, bestatin 130 μM, EDTA 1 mM, E-64 14 μM, leupeptin 1 μM, and PMSF 1 mM (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). They were sonicated three times for 10 s with 3-s intervals between the cycles. The protein concentration was quantified according to Lowry,20 to serve as reference to the cholesterol dosage. Cholesterol concentration was measured with the Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit (Invitrogen, USA).

Optical microscopy and imaging

Embryos were visualized in a Zeiss Axiovert 100 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Images were acquired with an Olympus DP71 high-resolution camera (Olympus, Japan). Images were analyzed and processed with the ImageJ software, based on the public domain NIH Image program (developed at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). The curvature index (CI) was calculated as the ratio between Feret diameter and tail length (a straight line has a CI of 1). Plates were prepared using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Incorporated, USA).

Scanning electron microscopy

Embryos were dechorionated, anesthetized by lowering the temperature, washed gently in warm phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.2, and then they were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, washed in buffer and then post-fixed for 1 h in 1% OsO4, dehydrated in crescent grades of ethanol, critical point dried with liquid/gas CO2, and sputter-coated with 15-nm-thick gold-palladium. The samples were examined in a JEOL 5800 scanning electron microscope (Jeol, Japan) using acceleration voltage of 25 KV. The images were manually colored using Adobe Photoshop.

Cell counting by isotropic fractionation

The total number of cells present in zebrafish embryos was determined using the isotropic fractionation method.21 Control and simvastatin-treated zebrafish embryos of different ages were immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer for seven days. Embryos were processed in 4 groups of 10 individuals per experimental condition. Suspensions of nuclei were obtained through mechanical dissociation of each group of 10 fixed embryos in a dissociation solution (40 mM sodium citrate and 1% Triton X-100), using a 1-mL glass Tenbroeck tissue homogenizer, in a final volume of 500 µL of the dissociation solution containing 1 mg/L of DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride; Molecular Probes, USA). Complete homogenization was achieved by grinding until the smallest visible fragments are dissolved. When performed on fixed tissue, this procedure lyses the plasmalemma but preserves the nuclear envelope intact. Four aliquots of the homogenate were collected directly from the homogenizer and loaded into a hemocytometer (Neubauer Improved) for quantification. The total number of nuclei was determined by counting the density of nuclei per milliliter in a hemocytometer under a fluorescence microscope and multiplying it by 0.5 (the total volume of the suspension of free nuclei). Suspensions were considered homogeneous when the coefficient of variation across aliquots of a same sample was smaller than 15% (typically 3–8%). The vast majority of nuclei had intact nuclear membranes, and only these nuclei were counted. Total numbers of nuclei in each group were then divided by 10 to obtain the average number of nuclei per embryo per condition. Assuming that all cells in the embryo contain one and only one nucleus, the average number of nuclei per embryo corresponds to the average number of cells per embryo.

Functional analysis

Embryos with 48 hpf were placed at the center of a 100-mm Petri dish filled with 50 mL of egg water. Embryos movements were recorded with a video camera using the software VirtualDub. Embryos were touched with a glass needle to stimulate their movements immediately before the recording. Movies were analyzed by the Manual Tracking Plugin in the public domain program ImageJ. All movies were recorded with a 0.2-s time interval between the frames. The following parameters were calculated from the movies: average speed, total distance and duration of the movement.

The movements and heartbeat of 48 hpf embryos was recorded after treatment in different conditions: control, simvastatin 0.3 nM, cholesterol, and simvastatin and cholesterol. To analyze the regularity of the beating, Z sections were cut along selected lines, and the kymogram was plotted for each experimental condition. To calculate the frequency of the beating, the distance of the first periodical spot in fast Fourier transform (FFT) was measured.

Statistical analysis

All the values were represented as the means ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons were performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparisons between more than two groups and unpaired t-test for comparisons between two groups. In some cases, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons was used to analyze the differences between each group. Statistical significance was defined as either P < 0.01 or P < 0.05 as indicated.

Results

Dose–effect relationship

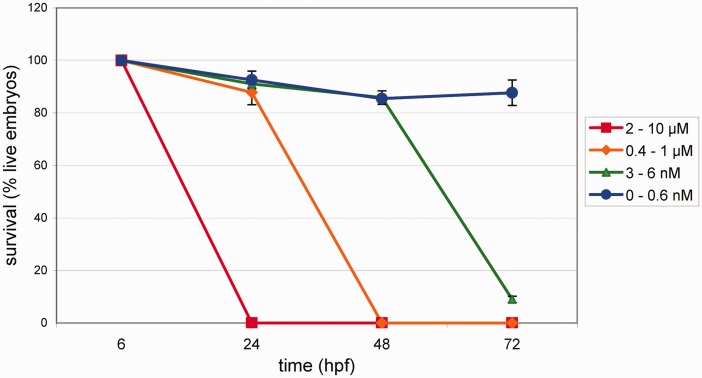

To study the effects of simvastatin in zebrafish, we first analyzed the survival of embryos after simvastatin was added to the tank water. Zebrafish embryos at 6 hpf (early gastrulation period) were treated with several simvastatin concentrations from 0.3 nM to 10 μM in egg water. Embryos were treated with simvastatin for 18 h at 28℃ until they completed 24 hpf. They were analyzed under bright field microscopy after varying time periods and the proportion of live embryos was measured (Figure 1). The 24 hpf embryonic stage was chosen since it has all the 32 somites formed. Since simvastatin is first dissolved in ethanol, before being added to the tank water, control embryos were treated with 0.02% ethanol for 18 h, and neither increase in lethality nor morphological changes were observed. This amount of ethanol corresponds to the highest amount of ethanol used in the experiments, when preparing the 10 μM simvastatin solution. Simvastatin at 2 μM to 10 μM induced the death of all embryos after 18 h of treatment, while the majority of the embryos survived in all other drug concentrations (from 3 nM to 1 μM) at this time point. Embryos treated with 3 nM to 6 nM of simvastatin showed an 85–90% survival rate after 42 h of treatment, while all embryos treated with 0.375 μM to 1 μM died. After 66 h of treatment with 3 nM of simvastatin, only 8% of the embryos survived. Taken together, these data show that simvastatin concentrations above 2 μM have a fast lethal effect in zebrafish embryos, and simvastatin concentrations below 2 μM induce survival rates that vary with time after treatment. Based on these results, we calculated the LC50 at 18 h to be 1.5 μM, at 42 h LC50 = 40 nM, and at 66 h, LC50 = 0.4 nM. Simvastatin in concentrations of 0.3 nM for 18 h showed almost no lethality up to 15 days after treatment: the embryos displayed phenotypes that were almost normal, although showing physiological alterations (see below).

Figure 1.

Survival rates of zebrafish embryos after simvastatin treatment. The number of live embryos in various times (18, 42, and 66 h) after treatment (hpt), corresponding to 24, 48, and 72 h after fertilization (hpf), with different simvastatin concentrations. At high concentrations, embryos die quickly, while at lower doses (<0.3 nM) they survive longer. Each point represents average and standard deviation. We estimated the LC50 at 18 h to be 1.5 μM, at 42 h LC50 = 40 nM, and at 66 h, LC50 = 0.4 nM. At least 90 embryos were used in each different simvastatin concentration. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

To confirm that simvastatin was actually decreasing the availability of cholesterol, we measured the cholesterol level in the embryos, and we were able to demonstrate that the treatment of embryos with 0.75 μM of simvastatin reduces the overall cholesterol in the embryo, not considering the yolk, from 1.5 ± 0.1 µg/mL of cholesterol to 0.9 ± 0.02 µg/mL (n = 3, P < 0.05, paired T-test). This result is in agreement with previous works that have shown that simvastatin actually reduces cholesterol.22

Morphological alterations induced by simvastatin

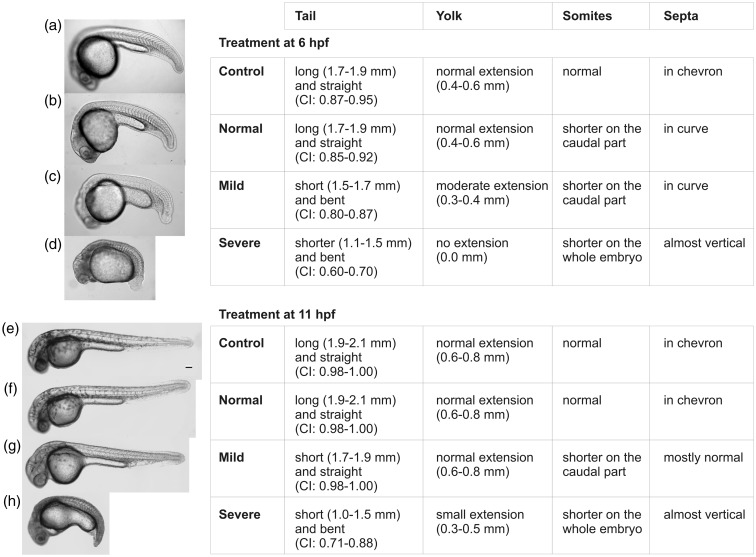

Next, because we wanted to analyze the effects of simvastatin in the myotomes, the major muscles of the embryo, we analyzed the phenotypes induced in zebrafish embryos treated at 6 hpf and 11 hpf with simvastatin at several concentrations and fixed at 24 hpf or 30 hpf (Figure 2(a)–(h)). Based on the results, we divided the resulting treated phenotypes in three major categories: normal, mild (caused by concentrations up to 6 nM), and severe (caused by concentrations over 0.375 μM). The classification of these phenotypes was based in four morphological parameters of the embryos: tail, somites, septa, and yolk. Each of these parameters was measured for every embryo, which enabled us to define the intervals of values shown in the Figure 2. Six hpf embryos treated with 0.3–0.6 nM showed no conspicuous morphological alterations (Figure 2(b)) and were classified as having a normal phenotype. Embryos with a mild phenotype have a shorter tail than control embryos, their somites are shorter in the caudal region, their septa were not in a chevron pattern, and the extension of the yolk was smaller (Figure 2(c)). Embryos with a severe phenotype have a short and bent tail, their somites are shorter along the whole embryo anterior–posterior axis than moderate phenotype embryos, their septa displayed an angle close to 180°, and their yolk showed no extension (Figure 2(d)). The same categories were observed with embryos treated at 11 hpf, although with less intensity (Figure 2(e)–(h)). In none of the conditions we observed a reduction in the number of somites, as can be seen in the Figure 2 and in accordance to our previous results.23 Afterwards, we consider “high doses” the simvastatin concentrations that induce conspicuous morphological changes and “low doses” the concentrations where no gross morphological changes were observed up to 24 or 30 hpf, respectively, after treatment at 6 or 11 hpf.

Figure 2.

Classification of simvastatin induced-phenotypes at different developmental times. Embryos were treated at 6 hpf and fixed at 24 hpf (a–d) and at 11 hpf and fixed at 30 hpf (e–h). For each time point, a representative image of each class of embryonic effect is shown over the parameters used to classify them (tail length, yolk length, and CI: Curvature Index). Zebrafish embryos were treated with the following simvastatin concentrations: Control (a, e): no simvastatin; Normal phenotype (b, f): up to 0.3 nM; Mild phenotype (c, g): from 3 to 6 nM; Severe phenotype (d, h): from 0.375 to 1 μM. Scale bar corresponds to 100 µm

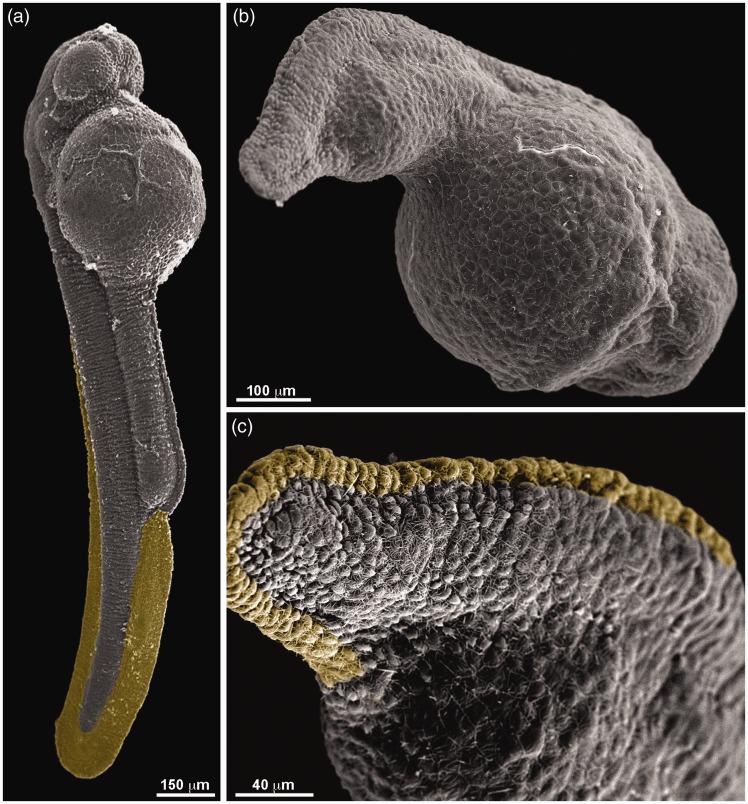

Structural analysis of severe phenotypes induced by high-dose simvastatin treatment: Scanning microscopy

To better characterize the affected phenotype, we decided to analyze in more detail the morphology of the severely affected, high-dose simvastatin treated embryos, using scanning electron microscopy. In control embryos, the tail is somewhat straight and cylindrical, and the yolk sack is large (Figure 3(a)). Embryos treated for 18 h, fixed with 24 hpf, have a short bent tail that extends a little beyond the yolk, which is also less present in the tail. The tail is not cylindrical but flattened (Figure 3(b)). The fin rudiment (colored with yellow) is conspicuous in the control, but highly reduced in the treated embryo (Figure 3(c)). No conspicuous changes were observed by scanning microscopy in low-dose simvastatin treatment.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy of zebrafish embryos treated with simvastatin. Ultrastructural features are observed in control embryos (a), which show a somewhat straight body with prominent caudal fin (labeled with yellow). High-dose simvastatin-treated embryos (b–c) have a reduced body length, with a bent tail. The caudal fin, seen more clearly in the higher magnification in (c), is drastically reduced. Scale bars: a = 150 µm, b = 100 µm, and c = 40 µm. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

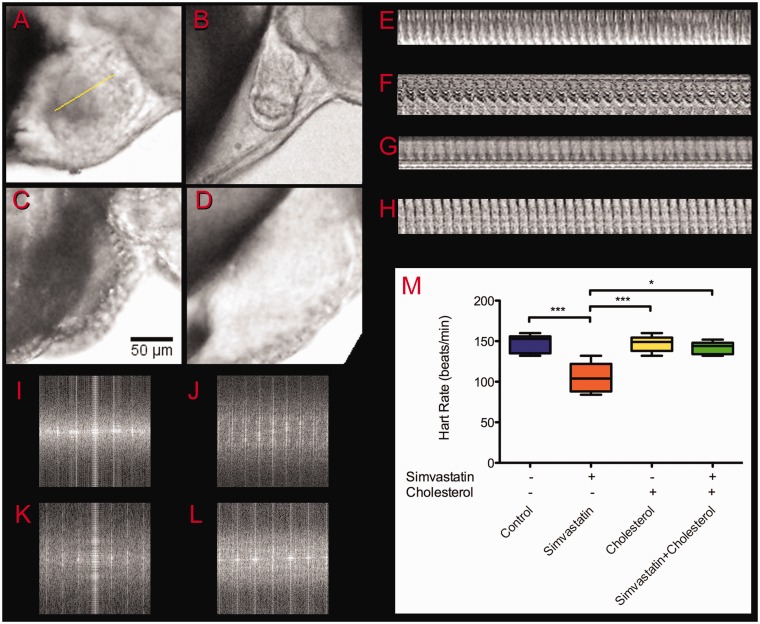

Physiological analysis of low-dose simvastatin treatment: Heartbeat

We decided to investigate if the embryos treated with low simvastatin doses (0.3–0.6 nM) that had apparently normal morphology were also physiologically normal. Embryos treated with higher concentrations (>3 nM) had several structures altered and died shortly after treatment, and therefore were not suited to these analysis. First, we analyzed the effects of simvastatin in their heartbeat frequencies. Embryos were treated with 0.3 nM or 0.6 nM simvastatin for 18 h, and 42 hafterward, at 48 hpf, they were observed in the microscope, when their heartbeats were manually registered and recorded in video (Figure 4 and Additional File 1). No significant differences between 0.3 nM and 0.6 nM simvastatin treatment were observed. Control embryos showed, at 48 hpf, a rate of 148 ± 11 beats/minute, which is in accordance with previous data described by Stainier et al.24 Heartbeat rate of low-dose simvastatin-treated embryos showed a statistically significant slower rate of 108 ± 20 beats/minute (Figure 4(m)). Furthermore, in the low-dose-treated embryos at this time, 48 hpf, the heart structure is altered, and around 30% of the embryos show a pericardial edema (Figure 4(b)). We hypothesized that heart frequency is affected by the cholesterol reduction, since simvastatin inhibits the HMG-CoAR, which is the key enzyme of the mevalonate pathway that leads to the production of cholesterol. On the other hand, statins are known to interfere with other pathways besides the synthesis of cholesterol, such as mevalonate synthesis and the prenylation of proteins.11,12 In order to investigate how much of the simvastatin effects were caused directly by cholesterol depletion, we decided to evaluate whether the simvastatin phenotype could be rescued by excess cholesterol. To reintroduce cholesterol in the embryos, we used isolated LDL. Embryos in which cholesterol was added together with low-dose simvastatin showed a heart rate of 140 ± 9 beats/minute, which was not significantly different than control embryos. Our results suggest that the simvastatin action in the zebrafish embryos involves the availability of cholesterol. Considering that cholesterol by itself can induce cardiac problems, we treated embryos with cholesterol alone, and they showed, again, a frequency not significantly different than control (147 ± 10 beats/minute). To avoid sampling mistakes, heart rate was measured using FFT (Figure 4(i)–(l)) of kymograms (Figure 4(e)–(h)).

Figure 4.

Heartbeat frequency analysis. The heartbeat of 48 hpf embryos was recorded after treatment in different conditions: control (a), simvastatin 0.3 nM (b), cholesterol alone (c), and simvastatin and cholesterol (d). To analyze the regularity of the beating, Z sections were cut along selected lines as shown in (a) and the kymograms were plotted for control (e), simvastatin 0.3 nM (f), cholesterol (g), and simvastatin and cholesterol (h). To calculate the frequency of the beating, we measured the distance of the first periodical spot in FFT analysis of control (i), simvastatin 0.3 nM (j), cholesterol (k), and simvastatin and cholesterol (l). The frequencies calculated from the videos were coincident with frequencies directly observed, plotted in (m). Scale bar in (c) corresponds to 50 µm. The average value for simvastatin is significantly different from all other conditions (P < 0.01; ANOVA), while no other condition is significantly different from any other. At least 10 embryos were used in each different experimental condition. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

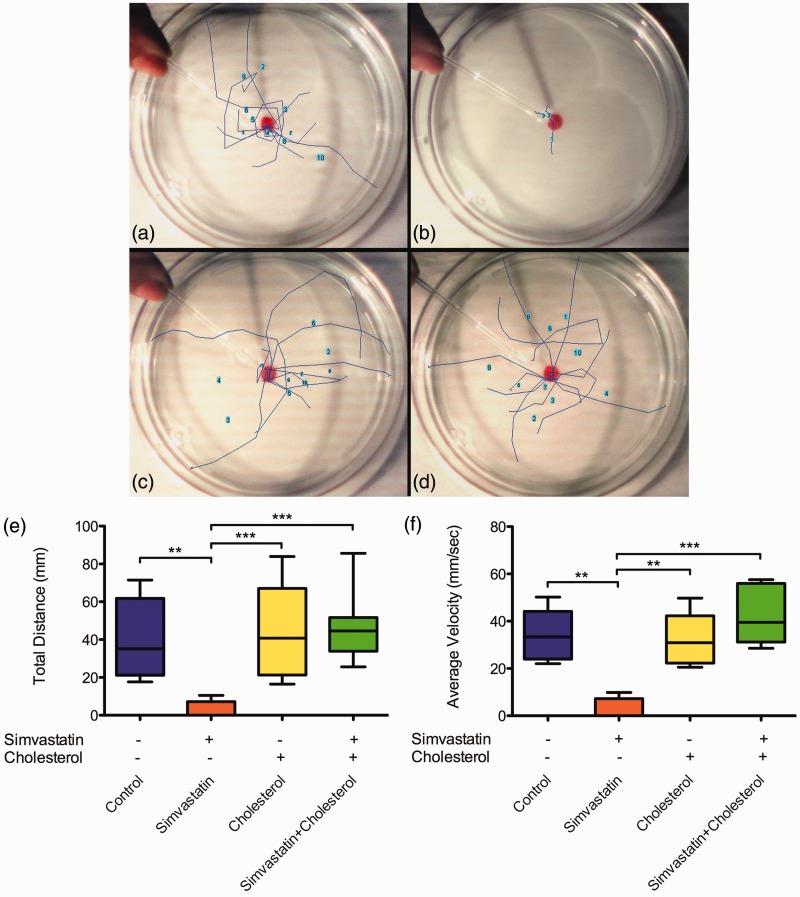

Physiological analysis of low-dose simvastatin treatment: Movement

Another physiological parameter we analyzed was the swimming capacity of low-dose simvastatin-treated embryos. Embryos were treated with 0.3 nM simvastatin for 18 h and their movements, after mechanical stimulation, were recorded in video after 42 h of treatment (Figure 5, Additional File 2). The path that each embryo followed in each movie was manually plotted as a colored line over the Petri dish for each condition: control (Figure 5(a)), simvastatin-treated (Figure 5(b)), cholesterol-treated (Figure 5(c)), and simvastatin-treated, cholesterol-rescued (Figure 5(d)). We measured from the movies and respective paths the following parameters: average speed, total distance, and duration of the movement. Simvastatin-treated embryos showed almost no movements. These results show that simvastatin significantly impairs the swimming capacity of zebrafish embryos in concentrations that do not induce death (Figure 5(e) and (f)). In embryos treated with cholesterol together with simvastatin, the movement was normal. Only the embryos treated with simvastatin alone showed statistically significant differences from all other conditions in the quantitative parameters we used to analyze movements. It is possible to say that, while low-dose simvastatin alone impairs the movement of the embryos, cholesterol was able to compensate for the effects of simvastatin in the swimming ability of embryos. Cholesterol alone, at least in the concentration we used, did not affect the movement of the embryos.

Figure 5.

Alterations in embryo movement induced by simvastatin. Zebrafish embryos were placed in a Petri dish and mechanically stimulated with a pipette in varying conditions: control (a), simvastatin 0.3 nM (b), cholesterol alone (c), and simvastatin and cholesterol (d). The escaping movement was recorded and traced on top of a slow-motion video afterwards. For each one of 10 embryos, we traced and plotted the average total distance (e) and average velocity (f). The average value for simvastatin is significantly different from all other conditions (distance: P < 0.01, velocity: P < 0.01; ANOVA), while no other condition is significantly different from any other. At least 10 embryos were used in each different experimental condition. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

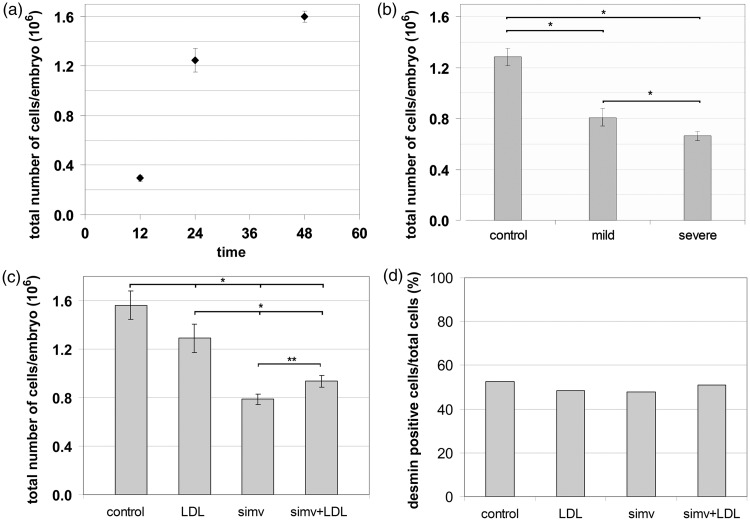

Changes in total cell number induced by simvastatin

We next examined whether the large reduction in body length of the altered phenotypes induced by simvastatin was related to changes in the total number of cells in the embryo. Embryos were fixed for one week in paraformaldehyde. After fractionation, we estimated the total number of nuclei in Neubauer chambers. First, we analyzed the precision of the methodology adopted to measure the growth in cell and nuclei number during zebrafish development. Total average numbers of cells per embryo quadrupled from 12 hpf to 24 hpf (from 29,438 ± 2337 cells to 124,656 ± 9773 cells, respectively), then increased by nearly 30% between 24 and 48 hpf (159,812 ± 4601 cells). Next, we observed at 24 hpf the changes in cell number caused by simvastatin treatment. Embryos treated with 6 nM of simvastatin, which led to mild phenotypes, suffered a 37% reduction in the average number of cells per embryo compared to age-matched control embryos. In comparison, embryos treated with a higher dose of 0.75 μM simvastatin, which showed a more severe phenotype, suffered a larger, 48% reduction in the average number of cells per embryo compared to age-matched controls (Figure 6(b)). These numbers indicate that simvastatin affects the total number of cells in embryonic development and suggest a relationship between simvastatin dosage, severity of the effect of the treatment, and cell number. To analyze if the addition of cholesterol together with simvastatin compensates cell loss, we did the nuclei isotropic fractionation in the same four different conditions mentioned before: (a) control, (b) with simvastatin (0.3 µM), (c) with cholesterol alone, and (d) with simvastatin and cholesterol. We observed a large and significant 50% reduction in total cell number in simvastatin-treated embryos, but a small significant 17% reduction in the total cell number in embryos treated with cholesterol alone, and 40% reduction in the total cell number in embryos treated with simvastatin together with cholesterol, which implies that cholesterol (together with simvastatin) caused a 20% increase in cell number relative to simvastatin alone (Figure 6(c)). Although simvastatin induces a reduction on the total cell number, we did not know if any tissue was more affected than other. Therefore, we decided to further investigate if the effects of simvastatin in cell number are related to muscle. Since we previously have shown25 that there is a perinuclear desmin network around muscle nuclei, we calculated the muscle/nonmuscle cell ratio using whole fixed embryos, immunostained for desmin, in which the nuclei were isolated and Dapi stained using the isotropic fractionation protocol. We estimated the number of desmin-positive cells to be approximate 52% of the total cells of the embryos at 48 hpf (Figure 6(b)). Simvastatin-treated embryos, cholesterol-treated embryos, and embryos treated with both cholesterol and simvastin all showed similar proportions of desmin-positive cells to untreated embryos (Figure 6(d)). The fact that the reduction in cell number observed in muscle is not significantly different than the changes in the whole embryo suggests that muscle is not particularly affected. Further studies will be needed to evaluate how much of this reduction is due to inhibition of cell proliferation and how much is due to cell death, and how much of the cell number reduction is specific to muscle. One important limitation of the technique is that we are actually counting nuclei number, and fast muscles in the embryos are multinucleated: it is difficult to speculate how different is the actual cell number from the nuclei number we are measuring.

Figure 6.

Embryo total cell number analysis. The total number of nuclei in the embryo was measured in different times after fertilization (a). Total cell number is reduced by simvastatin treatment (b). Embryos (6 hpf) treated with 6 nM simvastatin for 18 h (mild phenotype) showed a 37% reduction in total nuclei number compared to the control, while embryos treated with 0.75 μM (severe phenotype) showed a 48% of reduction in total nuclei. Comparison of nuclei number in control, simvastatin-treated (50% reduction), cholesterol alone (17% reduction), and simvastatin and cholesterol (40% reduction) (c). The number of desmin-positive cells is approximate 52% of the total cells of the embryos at 48 hpf (d). Simvastatin-treated embryos, cholesterol-treated embryos, and embryos treated with both cholesterol and simvastin all showed similar proportions of desmin-positive cells to untreated embryos. Statistically significant differences are marked with *(P < 0.01; ANOVA) or with **(P < 0.05; ANOVA). At least 40 embryos were used in each different simvastatin concentration

Discussion

Statins are lipid-lowering drugs that significantly reduce the risk of initial and recurrent cardiovascular events in humans. However, many patients report some form of myalgia during statin treatment. Skeletal muscle side effects that are associated with statin use involve muscle cramping, soreness, fatigue, and weakness.12–14 Statin-induced myopathy has been described as multifactorial, being the result of impaired signal transduction, protein synthesis, prenylation and glycosylation, improper calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondrial dysfunction.26,27

Many studies have been carried out to test the effects of statins in the structure and physiology of adult muscle, in humans and animal models, but our study is one of the first to test the effects of statins during early embryonic developmental stages. Although some studies16,17 show effects of statins in zebrafish embryos with 24 hpf, they do not focus on earlier developmental stages. Thorpe et al.28 studied developmental times earlier than 24 hpf, but they focus on germ cell migration, and they do not study how statins affect the initial development of skeletal muscle. Furthermore, the previous studies on statins on zebrafish did not evaluate muscle function changes. To fill these gaps, we tested the effects of simvastatin in zebrafish embryos in stages 6 hpf, before the commitment of precursors cells and cardiac and skeletal muscle formation, and in stage 11 hpf, when new somites are being formed while others are completing their maturation. These time points cover the major events in myogenesis.

We were able to establish a dose-response relationship, where concentrations above 6 nM induce rapid death of the embryos, and lower concentrations induce proportionally less damage to the embryos. Furthermore, we could classify the phenotypes obtained with the simvastatin treatment in three discrete categories (normal, mild, and severe phenotypes). These three categories could be observed both with embryos treated at 6 hpf and at 11 hpf, although the later were less affected than the former, probably because younger embryos have less committed cells, and therefore, a higher proportion of cells susceptible to the effects of simvastatin. Once a precursor cell is affected in a younger embryo, the disturbances are more intense and the long-term consequences larger than when the treatment happens in older embryos which have already formed the main organs and body structures. This classification in discrete phenotypes could be valuable for further studies. Embryos classified as normal showed no gross structural alterations, but physiological disturbances. In the severe phenotypes, there is a large reduction in embryo size. Several mutant or knockdown zebrafish exhibit shortened body axis, such as Wnt/beta-catenin and Shh.

We tested the cholesterol concentration in the embryos, and we could show an approximate 40% reduction in its level.

Following carefully the total nuclei number in the embryos, we observed a significant reduction in cell number with treatment that was proportional to the simvastatin concentration used. To our knowledge, this is the first calculation of total cell number of zebrafish embryos at 12, 24, and 48 hpf. The isotropic fractionation approach21 we used is more appropriate to larger cell numbers than techniques such as individual nuclei observation with optical microscopy.29 In a recently published manuscript,23 we also found many apoptotic nuclei in the somites of treated embryos, suggesting that simvastatin induces cell death in the zebrafish tissues. Many studies have shown that statins may promote apoptosis in a variety of cell types, including skeletal30 and cardiac cells.31 The simvastatin-induced cell death we observed could explain the severe and mild phenotypes, but since embryos treated with low simvastatin concentrations probably had normal cell number (since they seem phenotypically normal) and still showed affected movements, and reduction in cell number is not the only effect of simvastatin.

Simvastatin-treated embryos showed impaired movements. The movement deficiency could be caused by damage to the muscles or to the nerve. We cannot rule out the possibility that nerves are also affected, but in a recent study, we could show that the myofibrils are affected even in the low-dose treatment.23 We think that the structural damage is sufficient to cause the reduced motility. To test if simvastatin effects observed were caused by cholesterol withdrawal and not by other molecules, we sought to rescue the statin-induced phenotype with cholesterol. Exogenous cholesterol restored the movements and the structure of somites and septa. We could show that concentrations of cholesterol that do not seem to have adverse effects on the embryos are enough to recover the damage caused by simvastatin. It will be interesting to use zebrafish as a hypercholesterolemia model, and to see the effects of simvastatin in these animals. Further experiments should be done to test the role of other end results in the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway, such as mevalonate and glycosylation inhibition.

Furthermore, we found alterations on overall heart structure and in heartbeat frequency of simvastatin-treated embryos. These alterations could be caused by impaired signaling in the heart formation, caused by simvastatin-induced cholesterol lowering. Since statins are prescribed for the prevention of coronary heart problems through the reduction of blood cholesterol levels and protection of heart irrigation, it was unexpected to find major alterations in the heart of the zebrafish embryos. We can conclude from these results that cholesterol availability is crucial for normal heart development, and inhibition of cholesterol synthesis leads to major changes in heart morphology and function. Further studies are necessary in order to fully understand the molecular and cellular changes involved in the simvastatin-induced alterations in the heart of zebrafish embryos. It is worth mentioning that although the changes in movement induced by simvastatin could be caused by changes in innervation, this mechanism could not account for changes in heartbeat.

Simvastatin is prescribed in humans in doses that vary from 20 to 80 mg per day. Since humans have an average weight of 70 kg, we can estimate that simvastatin is used in humans in a proportion of 1 mg/kg. Zebrafish embryos have an average weight of 1 mg, and in this work, we treated the embryos with simvastatin in concentrations that ranged from 0.3 nM to 10 μM. For a concentration of simvastatin of 1 μM, we incubated the embryos with 21 µg of simvastatin in 50 mL of egg water. Assuming that the embryos have a volume of approximately 1 μl, we are treating embryos with 0.42 mg/kg. Although the delivery and absorption of the drug to embryos and humans are very different, and the susceptibility of embryos and adults are quite different, we could roughly compare the human dosage with zebrafish. In this way, we estimate that the concentrations that induce severe phenotype in zebrafish embryos are proportionally similar to that used in patients and that the concentrations that have mild effects on embryos’ structure and significant impact in heartbeat and movement are lower than the range used in hypercholesterolemic patients. Few studies have addressed the teratogenic effects of statins in humans, but mal formations, particularly structural defects in central nervous system and limbs, have been described.32

Simvastatin-induced effects in the muscle of zebrafish embryos could be related to alterations in the formation and stabilization of cholesterol enriched-membrane microdomains (lipid rafts). It has been shown that major alterations takes place in the sarcolemma microdomains during skeletal muscle differentiation.33 Changes in the availability of cholesterol, caused by simvastatin treatment, could induce alterations in the sarcolemma microdomains, which could lead to muscle defects. It is also possible that simvastatin is acting through inhibition of RhoGTPases, which are prenylated, and therefore downstream from HMG-CoAR. On the other hand, simvastatin affects several tissues, and we should take in account that simvastatin causes unspecific toxic effects.

Conclusions

We could show that simvastatin treatment in different concentrations and at different developmental stages induces morphological and physiological alterations in zebrafish embryos that could be classified in three distinct phenotypes. Interestingly, embryos treated at concentrations that caused no gross morphological damage still had deficit in muscle function, including movement reduction and slower heartbeat. These phenotypes could be rescued with cholesterol. Moreover, we could calculate the total cell number during zebrafish development and demonstrate a large reduction in cell number after statin treatment. We could speculate that simvastatin acts through more than one mechanism and could affect cell replication in general and muscle differentiation particularly.

These results demonstrate the impact of statins in the development of muscle and the suitability of the zebrafish model for the study of cholesterol diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientıfico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Apoio à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ). We thank Sandra Regina Enrique Castro for handling the fish.

Authors contributions

LMC performed the experiments, including data acquisition and analysis. EAR helped with data acquisition and analysis. LG helped to perform the experiments and analyze the data. VM and MB performed the scanning and transmission electron microscopy experiments, including data acquisition and analysis. GCA helped to plan and performs the cholesterol purification and embryo treatment. SHH helped to plan and perform the embryo nuclei quantification, including data acquisition and analysis. CSM helped to conceive the study and analyze the data. MLC conceived the study, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the whole project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Costa ML. Cytoskeleton and adhesion in myogenesis. ISRN Develop Biol 2014; 2014: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa ML, Escaleira RC, Rodrigues VB, Manasfi M, Mermelstein CS. Some distinctive features of zebrafish myogenesis based on unexpected distributions of the muscle cytoskeletal proteins actin, myosin, desmin, alpha-actinin, troponin and titin. Mech Dev 2002; 116: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa ML, Escaleira RC, Jazenko F, Mermelstein CS. Cell adhesion in zebrafish myogenesis: distribution of intermediate filaments, microfilaments, intracellular adhesion structures and extracellular matrix. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2008; 65: 801–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henry CA, McNulty IM, Durst WA, Munchel SE, Amacher SL. Interactions between muscle fibers and segment boundaries in zebrafish. Dev Biol 2005; 287: 346–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons K, Sampaio JL. Membrane organization and lipid rafts. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011; 3: a004697–a004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 2007; 370: 1829–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mermelstein CS, Portilho DM, Medeiros RB, Matos AR, Einicker-Lamas M, Tortelote GG, Vieyra A, Costa ML. Cholesterol depletion by methyl-beta-cyclodextrin enhances myoblast fusion and induces the formation of myotubes with disorganized nuclei. Cell Tissue Res 2005; 319: 289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mermelstein CS, Portilho DM, Mendes FA, Costa ML, Abreu JG. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation and myogenic differentiation are induced by cholesterol depletion. Differentiation 2007; 75: 184–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portilho DM, Soares CP, Morrot A, Thiago LS, Butler-Browne G, Savino W, Costa ML, Mermelstein C. Cholesterol depletion by methyl-β-cyclodextrin enhances cell proliferation and increases the number of desmin-positive cells in myoblast cultures. Eur J Pharmacol 2012; 694: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tobert JA. Lovastatin and beyond: the history of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003; 2: 517–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein J, Brown M. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature 1990; 343: 425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Stasi SL, MacLeod TD, Winters JD, Binder-Macleod SA. Effects of statins on skeletal muscle: a perspective for physical therapists. Phys Ther 2010; 90: 1530–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker SK, Tarnopolsky MA. Statin myopathies: pathophysiologic and clinical perspectives. Clin Invest Med 2001; 24: 258–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA 2003; 289: 1681–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gjini E, Hekking LH, Küchler A, Saharinen P, Wienholds E, Post J, Alitalo K, Schulte-Merker S. Zebrafish tie-2 shares a redundant role with tie-1 in heart development and regulates vessel integrity. Dis Model Mech 2011; 4: 57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanai J, Cao P, Tanksale P, Imamura S, Koshimizu E, Zhao J, Kishi S, Yamashita M, Phillips PS, Sukhatme VP, Lecker SH. The muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1/mafbx mediates statin-induced muscle toxicity. J Clin Invest 2007; 117: 3940–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao P, Hanai J, Tanksale P, Imamura S, Sukhatme VP, Lecker SH. Statin-induced muscle damage and atrogin-1 induction is the result of a geranylgeranylation defect. FASEB J 2009; 23: 2844–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner BK, Gilbert TJ, Hanai J, Imamura S, Bodycombe NE, Bon RS, Waldmann H, Clemons PA, Sukhatme VP, Mootha VK. A small-molecule screening strategy to identify suppressors of statin myopathy. ACS Chem Biol 2011; 6: 900–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westerfield M. The zebrafish book. A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio), Eugene: University of Oregon Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 1951; 193: 265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herculano-Houzel S, Lent R. Isotropic fractionator: a simple, rapid method for the quantification of total cell and neuron numbers in the brain. J Neurosci 2005; 25: 2518–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baek JS, Fang L, Li AC, Miller YI. Ezetimibe and simvastatin reduce cholesterol levels in zebrafish larvae fed a high-cholesterol diet. Cholesterol 2012; 2012: 564705–564705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campos LM, Rios EA, Midlej V, Atella GC, Herculano-Houzel S, Benchimol M, Mermelstein C, Costa ML. Structural analysis of alterations in zebrafish muscle differentiation induced by simvastatin and their recovery with cholesterol. J Histochem Cytochem 2015; 63: 427–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stainier DY, Lee RK, Fishman MC. Cardiovascular development in the zebrafish. I. Myocardial fate map and heart tube formation. Development 1993; 119: 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mermelstein CS, Andrade LR, Portilho DM, Costa ML. Desmin filaments are stably associated with the outer nuclear surface in chick myoblasts. Cell Tissue Res 2006; 323: 351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prendergast GC, Oliff A. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors: antineoplastic properties, mechanisms of action, and clinical prospects. Semin Cancer Biol 2000; 10: 443–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Donk NWCJ, Lokhorst HM, Nijhuis EHJ, Kamphuis MMJ, Bloem AC. Geranylgeranylated proteins are involved in the regulation of myeloma cell growth. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 429–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorpe JL, Doitsidou M, Ho S, Raz E, Farber SA. Germ cell migration in zebrafish is dependent on hmgcoa reductase activity and prenylation. Dev Cell 2004; 6: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller PJ, Schmidt AD, Wittbrodt J, Stelzer EHK. Reconstruction of zebrafish early embryonic development by scanned light sheet microscopy. Science 2008; 322: 1065–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dirks AJ, Jones KM. Statin-induced apoptosis and skeletal myopathy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006; 291: C1208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Copaja M, Venegas D, Aránguiz P, Canales J, Vivar R, Catalán M, Olmedo I, Rodríguez AE, Chiong M, Leyton L, Lavandero S, Díaz-Araya G. Simvastatin induces apoptosis by a rho-dependent mechanism in cultured cardiac fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2011; 255: 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edison RJ, Muenke M. Mechanistic and epidemiologic considerations in the evaluation of adverse birth outcomes following gestational exposure to statins. Am J Med Genet A 2004; 131: 287–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Draeger A, Sanchez-Freire V, Monastyrskaya K, Hoppeler H, Mueller M, Breil F, Mohaupt MG, Babiychuk EB. Statin therapy and the expression of genes that regulate calcium homeostasis and membrane repair in skeletal muscle. Am J Pathol 2010; 177: 291–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.