Abstract

Objectives

A critical mission of acute care hospitals is to reduce hospital readmissions to improve patient care and avoid monetary penalties. We speculated that stroke patients with enteral tube feeding are high-risk patients and sought to evaluate their hospital readmissions.

Methods

We analyzed archival hospital billing data from stroke patients discharged from acute care hospitals in Florida in 2012 for 30- and 60-day readmission rates, 30-day readmission rates by discharge destination, most frequent primary readmission diagnoses, and predictors of 30-day readmissions. We conducted univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses.

Results

We analyzed 26,774 discharge records. Within 30 days after discharge, 21.06% (N = 299) of stroke patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement were rehospitalized. Of those readmissions, 11.71% (N = 35) were preventable. Among stroke patients with a PEG tube placement, 53.80% were discharged to skilled nursing facilities and 27.88% were rehospitalized within 30 days. Septicemia was the most frequent primary readmission diagnosis. Comorbidities, stroke type, length of hospital stay, and discharge destinations were predictive for 30-day readmissions (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was .81).

Conclusions

Stroke patients with a PEG tube placement during their index hospital stay are twice as likely to be readmitted within 30 days compared to stroke patients without PEG tube placements. The primary readmission diagnosis for some patients was directly linked to PEG tube complications. We have identified risk factors that can be used to focus resources for readmission prevention.

Keywords: Stroke, enteral nutrition, patient readmission, risk factors, complications

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act has authorized the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program, wherein acute care hospitals are penalized for 30-day all-cause “preventable” readmissions that exceed the national mean of hospital readmissions. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) “defined readmission as an admission to a subsection(d) hospital within 30 days of a discharge from the same or another subsection(d) hospital”.1 Reducing readmission rates has a clear monetary incentive, because the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that 78% of all hospitals will be penalized with a total amount of $428 million in penalty payments in the fiscal year 2015.2 Further, readmissions are often used as a surrogate for quality of care and hospital performance, making readmission reduction efforts important to patients as well.

CMS plans to include patients with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke in readmission measures.3 It has been previously shown that approximately 14% of all stroke patients are readmitted within 30 days4,5 and subsequent admissions are associated with higher mortality.6 However, only around 12% of these readmissions were preventable and, therefore, a possible target for quality of care improvements. To successfully prevent patients from being hospitalized, it is crucial to know which patients are at risk for readmission and why they are at risk. Previous studies have attempted to identify factors that are associated with readmissions for ischemic stroke patients but failed to agree on consistent risk factors.7 This might in part be due to the heterogeneity of the ischemic stroke population. Thus, investigating specific populations might identify more consistent factors related to readmissions. Lichtman et al recommend that hospital-level programs should target high-risk patients if their goal is a reduction in all-cause readmissions and costs.5 One group of high-risk stroke patients includes patients who receive a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. Short- and long-term complications have been commonly reported in this patient group.8 Furthermore, a retrospective cohort study of stroke patients seen in an academic medical center found that enteral tube feeding is an independent predictor for rehospitalizations from their inpatient rehabilitation unit to an acute care hospital.9 However, to the best of our knowledge, it has not been investigated whether PEG tube placements are related to readmissions as they are defined by CMS (30-day acute care hospital readmissions). More importantly, little is known about potential strategies to reduce readmissions of stroke patients with PEG tubes. Therefore, we sought to evaluate acute care hospital readmissions of stroke patients with a PEG tube placement during their acute hospital stay and identify potential avenues for reducing readmissions. The objectives of our study were (1) to determine the 30- and 60-day readmission rates and the proportion of preventable readmissions, (2) to identify 30-day readmissions per discharge destination, (3) to evaluate the primary readmission diagnoses, and (4) to build a prediction model for 30-day readmissions of stroke patients with PEG tube placement. By better understanding factors related to readmissions, we can use factors that are modifiable to proactively prevent readmissions and use factors that are nonmodifiable to optimize the care for patients at risk for readmissions (e.g., by early resource allocation).

Methods

A retrospective analysis of hospital billing data was conducted using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Florida State Inpatient Database from 2012. This database includes all inpatient discharge records from acute care community hospitals in Florida for the year. We identified a stroke inception cohort consisting of patients with a primary diagnosis of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes that have been shown to be the most accurate and highly specific: 434.xx and 431.xx.10 PEG tube placement during the index hospital stay was identified through the ICD-9-CM procedure code 43.11. We excluded all patients who were younger than 18 years or who died during the index admission. We used the prevention quality indicators (PQIs) provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to calculate the proportion of preventable readmissions (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infection, dehydration, diabetes complications, hypertension).11

We investigated readmissions after patients’ discharge from the index hospital stay for (1) total and preventable 30- and 60-day readmission rates for all stroke patients, stroke patients with PEG tube placement, and stroke patients without PEG tube placement; (2) readmission rates by discharge destination for stroke patients with PEG tube placement; and (3) the 5 most frequent primary diagnoses for 30-day readmissions of stroke patients with PEG tube placement and stroke patients without PEG tube placement. Finally, we modeled the risk of 30-day readmissions for stroke patients with PEG tubes.

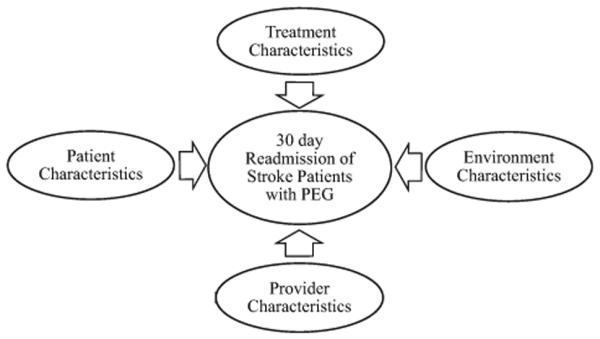

For the prediction model, we identified risk factors from 4 domains that represented our underlying conceptual model (Fig 1). The selection of risk factors followed 2 criteria: (1) previous evidence suggesting an impact on clinical outcomes and/or the likelihood of rehospitalization,7 and (2) availability in the dataset. The model domain “Patient Characteristics” included the following factors: age, black race, Hispanic race (black race and Hispanic race were tested against white race), female, hospital length of stay (LOS, used as binary variable with a median LOS of 11 days as the cutoff point), admission on weekends, hemorrhagic stroke, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI is a validated index to predict 1-year mortality based on a patient’s comorbidities.12 We applied the most recently updated CCI coding algorithm.13,14 The domain “Provider Characteristics” encompassed specific factors of the admitting hospital. These factors were annual volume of admitted stroke patients, volume of PEG tube placements in stroke patients, volume of tissue plasminogen activator treatment in stroke patients, and volume of weekend admissions (with all variables being expressed in quartiles). The domain “Environment Characteristics” included the following factors: estimated median household income in patients’ zip code area, county of residence (rural versus urban), discharge to home, inpatient rehabilitation, hospice, or other destinations (such as intermediate care facilities and Medicare certified longterm care hospitals). All discharge destinations were tested against discharge to nursing facilities (skilled nursing facility (SNF), nursing facility certified by Medicaid, etc.). The fourth domain, “Treatment Characteristics,” consisted of patient-specific factors describing treatment procedures, including tissue plasminogen activator, endovascular mechanical thrombectomy, ventilator dependency, and tracheostomy.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for predicting 30-day readmissions of stroke patients with PEG tubes. Abbreviation: PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Univariate analyses were conducted for patient descriptions (age, gender, race, stroke type, and CCI), readmission rates, readmission diagnoses, and mortality during readmissions. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to model 30-day readmissions in stroke patients with PEG tubes by identifying, first, significant predictors in each of the four domains separately, and, second, significant predictors across all remaining predictors. To determine the variables in the final model, we applied manual backward selection regression with P values of the covariates greater than .05 and increased Akaike information criterion. We determined the discriminatory capacity for differentiating patients who will and will not be readmitted within 30 days by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. We assessed model fit with the Hosmer and Lemeshow test. All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). After review, our institutional review board deemed the study not human subjects research.

Results

Patient Characteristics

In total, 34,552 discharge records were coded with the primary diagnoses of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. After excluding all noneligible records, we analyzed 26,774 discharge records, whereas 1420 were coded for PEG tube placement (5.30%). Table 1 shows the demographic and medical characteristics for the different patient groups. We compared stroke patients with and without PEG tube placement with nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon ranksum test and chi-square test where appropriate) because all variables were not normally distributed. We found that stroke patients with PEG tube placement were slightly older, were more likely to be a racial minority, were more likely to have a hemorrhagic stroke, and had more comorbidities in comparison to patients without PEG tube placement.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All stroke patients |

Stroke patients with PEG tube placement |

Stroke patients without PEG tube placement |

Difference between stroke patients with and without PEG tube placement (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge records, % (N) | 100 (26,774) | 5.30 (1,420) | 94.70 (25,354) | N/A |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 71.44 (14.47) | 73.20 (13.48) | 71.35 (14.51) | <.0001 |

| Females, % (N) | 51.27 (13,727) | 51.13 (726) | 51.28 (13,001) | .9117 |

| Whites, % (N) | 66.71 (17,860) | 57.04 (810) | 67.25 (17,050) | <.0001 |

| Ischemic stroke, % (N) | 90.20 (24,151) | 77.61 (1,102) | 90.91 (23,049) | <.0001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (max 24), total score (SD) |

3.04 (1.88) | 3.95 (1.85) | 2.99 (1.87) | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; SD, standard deviation.

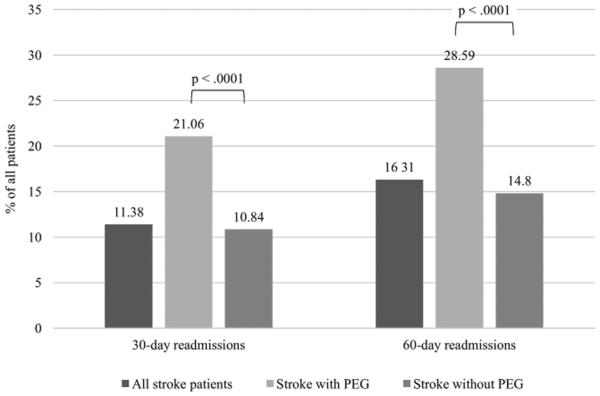

Objective 1: Readmission Rates

Figure 2 shows that stroke patients with a PEG tube placement during their index hospital stay were approximately twice as likely to be readmitted within 30 and 60 days compared to stroke patients without PEG tube placement. This difference was statistically significant (chi-square test, P < .0001 for 30- and 60-day readmissions).

Figure 2.

Readmission rates (30 and 60 days) for all stroke patients, stroke patients with PEG tube placement, and stroke patients without PEG tube placement. Abbreviation: PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses showed that PEG tube placement during the index hospital stay was an independent predictor for 30- and 60-day hospital readmissions for all stroke patients while controlling for age, gender, stroke type, and CCI (odds ratio = 1.972, 95% confidence interval 1.721-2.259, P <.0001; odds ratio = 1.956, 95% confidence interval = 1.730-2.2210, P <.0001, respectively).

According to the AHRQ PQI measures, we found that 13.09% (N = 399) of all 30-day readmissions were preventable for all stroke patients, 11.71% (N = 35) for stroke patients with PEG tube placement, and 13.25% (N = 364) for stroke patients without PEG tube placement. Of those patients who were readmitted within 30 days, 4.46% (136 of 3047) of all stroke patients, 10.36% (31 of 299) of stroke patients with PEG tube placement, and 3.77% (105 of 2748) of stroke patients without PEG tube placement died during the readmission. Of those patients who were readmitted within 60 days, 4.01% (175 of 4367) of all stroke patients, 9.35% (38 of 406) of stroke patients with PEG tube placement, and 3.46% (137 of 3962) of patients without PEG tube placement died during the readmission.

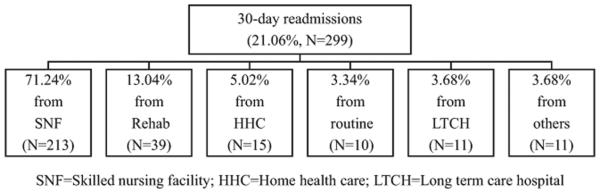

Objective 2: Readmissions in Relation to Discharge Location

From their index hospital stay, the vast majority of stroke patients with a PEG tube placement were discharged to SNFs (53.80%) with rehabilitation facilities being the second most frequent (15.56%) discharge site (Table 2). Of all stroke patients with a PEG tube placement who were discharged to a SNF or to a rehabilitation facility, 27.88% and 17.65%, respectively, were readmitted to an acute care hospital within 30 days after their discharge from the index hospital stay. Of all stroke patients with PEG tube placement who were readmitted within 30 days (N = 299), 71.24% had been discharged from their index hospital stay to SNFs and 13.04% to rehabilitation facilities (Fig 3).

Table 2.

Discharge destinations and proportion of readmitted patients from all stroke patients with PEG tube placement

| Discharge destination | % Discharged to facility type |

% Readmitted within 30 days from facility type |

|---|---|---|

| Skilled nursing facility | 53.80 | 27.88 |

| Rehabilitation facility (including hospital rehab units) |

15.56 | 17.65 |

| Long-term care hospital | 9.15 | 8.46 |

| Hospice (medical facility) | 8.24 | 1.71 |

| Home health care | 4.15 | 25.42 |

| Routine (home or self-care) | 2.75 | 25.64 |

Figure 3.

Stroke patients with PEG tube placement who were readmitted within 30 days and their original discharge destination from their index hospital stay.

Objective 3: Primary Diagnoses for Readmissions

Table 3 shows that of all readmitted stroke patients who had a PEG tube placement during their index hospitalization, 16.72% were coded for septicemia, the most frequent primary readmission diagnosis. The second most frequent readmission diagnosis was food or vomit pneumonitis (6.69%). In terms of preventable readmissions, the most frequent diagnosis was urinary tract infection (28.57%) followed by pneumonia (≈25%) and congestive heart failure (≈25%).

Table 3.

Top 5 primary diagnoses for 30-day readmissions for stroke patients with and without PEG tube placement (percentages reflect the proportion of readmissions with this primary diagnosis)

| Rank | Stroke patients with PEG tube placement (N = 1,420) |

Stroke patients without PEG tube placement (N = 25,354) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All readmissions (N = 299) |

Preventable readmissions only (N = 35) |

All readmissions (N = 2,748) |

Preventable readmissions only (N = 364) |

|

| 1 | Septicemia (16.72%) | UTI (28.57%) | Cerebral artery occlusion (14.45%) |

UTI (23.90%) |

| 2 | Food/vomit pneumonitis (6.69%) |

Pneumonia (25.71%)* | Septicemia (3.89%) | Congestive heart failure (23.08%) |

| 3 | Cerebral artery occlusion (5.35%) |

Congestive heart failure (25.71%)* |

TIA (3.68%) | Pneumonia (18.96%) |

| 4 | Acute kidney failure (4.68%) | COPD (8.57%) | Acute kidney failure (3.60%) | COPD (7.42%)* |

| 5 | UTI (3.34%) | Diabetes with long-term complications (5.71%) |

Food/vomit pneumonitis (3.09%) |

Hypertension (7.42%)* |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; TIA, transient ischemic attack; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Neighboring cells are tied.

For patients without a PEG tube placement, the most frequent primary diagnoses for 30-day readmissions were cerebral artery occlusion and septicemia, coded in 14.45% and 3.89% of all readmitted patients as the primary diagnosis, respectively. The most frequent primary diagnoses for preventable readmissions were urinary tract infections, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia, each representing a quarter to a fifth of all preventable readmissions.

Readmission diagnoses that were directly related to the PEG tube placement were only present in a few cases in all subgroups that we analyzed for PEG tube placement. In the group of ischemic stroke patients with PEG tube placement, the primary diagnosis of “attention to gastrostomy” (ICD-9-CM diagnosis code V55.1) was the fifth most frequent 30-day readmission diagnosis with 2.68% (N = 8) of all readmissions. “Attention to gastrostomy” is a billing code that can be used in different situations. Three of the eight patients in our cohort were coded for PEG tube placement, 2 patients were coded for PEG tube replacement, and 1 patient each was coded for enterostomy and parenteral infusion of concentrated nutritional substances. One patient had no procedure code entries associated with their readmission.

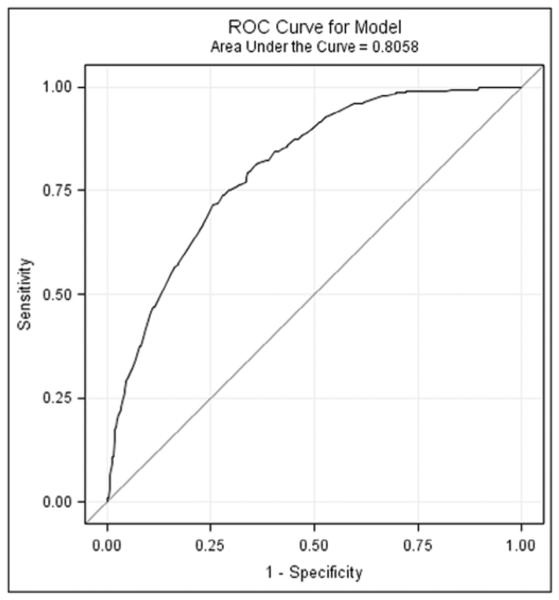

Objective 4: Risk Model

We modeled the risk of 30-day readmissions for stroke patients with PEG tube placement. The following factors were significant in the domain-specific analyses: hemorrhagic stroke, CCI, and LOS (<11 days) in the domain “Patient Characteristics”; and discharge to rehabilitation facility, hospice, and other discharge destinations in the domain “Environment Characteristics.” No factor was significant in the domains “Treatment Characteristics” or “Provider Characteristics.” We combined all significant predictors in the final model. All factors fulfilled the criteria of being independent predictors for 30-day readmissions (Table 4). Diagnostics of the model indicated a good model fit with a P value of .5758 in the Hosmer and Lemeshow test. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was .81 (P < .0001) (Fig 4).

Table 4.

Thirty-day readmission prediction model for stroke patients with PEG tube placement

| Predictor/independent variable | β | SE β | P value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhagic stroke | −2.1875 | .4330 | <.0001 | .112 (.048-.262) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | .1607 | .0390 | <.0001 | 1.174 (1.088-1.268) |

| Length of hospital stay (≥11days) | −1.7911 | .1650 | <.0001 | .167 (.121-.230) |

| Discharge to home | .6291 | .2565 | .0142 | 1.876 (1.135-3.101) |

| Discharge to rehab facility | −1.5210 | .3344 | <.0001 | .218 (.113-.421) |

| Discharge to hospice | .3060 | .2216 | .1673 | 1.358 (.880-2.097) |

| Discharge to other destinations | .8771 | .2033 | <.0001 | 2.404 (1.614-3.580) |

Abbreviations: β, regression coefficient; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; SE, standard error.

Figure 4.

ROC curve for the modeled risk of 30-day readmissions of stroke patients with PEG tube placement. Abbreviation: ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Discussion

Although reducing hospital readmissions to improve patients’ health is always a worthy goal, it is more important now than ever to evaluate the means to reach this goal. Both the increased recognition of hospital readmissions as a surrogate for quality of care and the monetary penalties related to the Affordable Care Act are compelling hospital administrators and clinicians to undertake quality improvement projects to decrease readmission rates. Resources toward this goal have to be devoted to (1) preventable readmissions and (2) detection of issues related to unpreventable readmissions to address “problems” at an earlier, less severe disease state. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating hospital readmissions of stroke patients who have had a PEG tube placement during their index hospital stay.

For stroke patients, PEG tube placement during the index hospital stay was a significant independent predictor for 30- and 60-day hospital readmissions. In Florida in 2012, every fifth stroke patient with a PEG tube placement was readmitted within 30 days after being discharged from the acute care hospital. This was twice as many patients as compared to stroke patients without a PEG tube placement. The proportion of readmitted stroke patients with PEG tube placement increased for 60-day readmissions, so that 1 out of 4 patients were readmitted at least once within this period. Only a minority (11%-13%) of all readmissions were classified as preventable, which is in line with previous findings for ischemic stroke patients.5 Although many readmissions were not preventable, it is likely that earlier attention to these patients may be able to reduce the severity of the cause of their readmission.

Our analyses of readmission rates based on discharge destinations revealed that stroke patients with PEG tubes who were discharged to SNFs had the highest probability to be readmitted within 30 days. This finding does not necessarily mean that patients in SNFs receive inferior care compared with patients discharged to other facilities. The vast majority of stroke patients with PEG tube placement were discharged to SNFs; therefore, it is to be expected that the largest proportion of readmitted patients also comes from this group. In comparison, every fourth patient who was discharged to home health care or home/self-care was readmitted within 30 days, which is about the same proportion as readmitted from SNFs. However, only very few patients were discharged to home health care or home/self-care. It is possible that patients who were more ill were discharged to SNFs instead of to other locations. Future studies are needed to further evaluate readmissions that are linked to SNFs, because our findings suggest that efforts to reduce readmission rates should focus on SNFs to have maximum effectiveness.

The third objective of our study was to identify diagnoses that lead to readmissions with a special interest in PEG tube-related complications. This knowledge can assist clinicians in preventing readmissions or, at least, in reducing the severity of the illness at the time of readmission by focusing on poststroke complications that most likely lead to readmissions. Indeed, we found that complications related to PEG tubes are among the most frequent readmission causes of stroke patients with PEG tube placement. However, when looking at absolute numbers, PEG tube-related complications were rare events. Some ischemic stroke patients were readmitted because of a procedure targeting the gastrostomy, which was typically a placement of a (new) feeding tube. We found that food and vomit pneumonitis was the primary diagnosis for a readmission in 6.69% of all stroke patients with a PEG tube placement. Food and vomit pneumonitis is a well-known complication in patients with enteral tube feeding. Specific interventions and patient care procedures can reduce the occurrence of aspiration of oropharyngeal, gastric, or tube feeding contents and can consequently reduce the risk for pneumonitis.15 However, according to the AHRQ-PQI measures, pneumonitis is not preventable. Thus, our estimated proportion of preventable readmissions might not reflect the true number of preventable readmissions.

When looking at preventable readmissions only, pneumonia comprised a fifth (20%) of all preventable 30-day readmissions for patients with PEG tube placements. Like pneumonitis, pneumonia is a common complication with gastrostomy tubes and is also common for patients with dysphagia, with or without a feeding tube. Investigating the contribution of dysphagia to hospital readmissions was not possible due to known undercoding for dysphagia.16 Future, prospective studies should address the relationship of dysphagia and readmissions. Additionally, diagnoses such as septicemia, one of the leading readmission diagnoses for stroke patients, might mask PEG tube-related complications that developed in septicemia. Again, the true contribution of PEG tube induced complications to hospital readmissions warrants further investigation.

The last objective of the present study was to determine which patients, under which circumstances, will be readmitted. To answer this question, we built a predictive model for 30-day readmissions in stroke patients with a PEG tube placement during their index hospital stay. The likelihood that a patient was readmitted within 30 days was higher for patients with more comorbidities, with a LOS of less than 11 days, with ischemic stroke, and with a discharge destination of home or nursing facilities.

Stroke patients with PEG tube placement stayed on average (median) 11 days in the hospital (range 0-318). A shorter LOS of less than 11 days increased the risk for 30-day readmissions. This suggests that patients who are more severely ill, such as patients with PEG tube placement, develop more complications when they are discharged early.

In our model, race was not significant. This finding is in part contradictory to previous findings that black and Hispanic ischemic stroke patients have higher risks for PEG tube placements than white patients.17 In our study, patients with and without PEG tube placements showed significant differences in race distribution based on univariate analyses. However, after adjusting for treatment, provider and environment characteristics, race was not significant for 30-day readmissions.

Overall, our predictive model supports the common clinical intuition that strategies for readmission prevention should focus on ischemic stroke patients with multiple comorbidities who are discharged to nursing facilities, especially to SNFs, or discharged home. Our model had a good predictive capability for 30-day readmissions of stroke patients with PEG tube placement. Future research is needed to verify the quality and generalizability of our model in other settings.

The findings of our study have several implications for clinical practice. The high rate of readmissions and, the not to be ignored, mortality rate during rehospitalizations emphasize that clinicians should raise their awareness for patients with PEG tube placement and implement strategies to prevent complications that lead to rehospitalizations. For example, systematic follow-ups of stroke patients with PEG tube placements are needed, which could include timely postdischarge appointments and contact (phone calls, telehealth visits) from relevant members of the health-care team (e.g., speech and language pathologists for patients who have a PEG tube because of dysphagia). As every fourth stroke patient with an initial PEG tube placement is rehospitalized within 60 days, re-evaluations of the PEG tube indication during the readmission could be of great benefit for patients who did not have access to re-evaluations after being discharged from an acute care hospital. For example, re-evaluations could identify patients whose oral diet can be improved and/or whose PEG tube can be removed. Consequently, this might prevent future hospital readmissions.

Furthermore, risk models, like ours, can aide early identification of patients at risk for readmissions. This knowledge can guide clinicians to intensify patient education and discharge processes and reduce possible complications related to readmissions. As an example, our results suggest that patient-level follow-up strategies should start with ischemic stroke patients with numerous comorbidities who are discharged to SNFs, home health care, or home/self-care.

Study Limitations

Our study has several limitations. We analyzed a secondary dataset and, thus, there is the potential for ascertainment bias with possible mismatches between coding and clinical assessments. Further, factors like stroke severity, brain lesion volume, dysphagia, hospital type, and hospital size might cause variations in readmission rates but were not assessable with the dataset. We assume that stroke patients with a PEG tube placement are more severely ill than patients without a PEG tube; however, we were not able to control for stroke severity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, PEG tube placement during the acute hospital stay is an independent predictor for 30- and 60-day readmissions of stroke patients. Within 30 days, 1 in every 5 stroke patients with PEG tube placement will be readmitted. This number increases to 1 in every 4 patients within 60 days. Compared to stroke patients without PEG tube placements, stroke patients with PEG tube placement are twice as likely to be readmitted and to die during hospital readmissions. This difference may reflect a difference in stroke severity. The primary readmission diagnosis for some patients was directly linked to PEG tube complications. Additionally, our predictive model suggests that ischemic stroke patients with a PEG tube placement who have multiple comorbidities and who have been discharged to SNFs or discharged home, are at high risk for readmissions. The results of our study can assist clinicians in implementing quality improvement projects to reduce readmissions in this vulnerable group of stroke patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by NIH – NCATS KL2 TR000060.

Footnotes

Institution where the study was performed: Medical University of South Carolina, Department of Health Sciences and Research, College of Health Professions.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boccuti C, Casillas G. Aiming for Fewer Hospital U-turns: The Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 3.CMS CfMMS Medicare program; hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long-term care hospital prospective payment system and fiscal year 2014 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; hospital conditions of participation; payment policies related to patient status. Final rules. Fed Regist. 2013;78:50495–51040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elixhauser AA, Steiner CA. HCUP statistical brief #153. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2013. Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtman JH, Leifheit-Limson EC, Jones SB, et al. Preventable readmissions within 30 days of ischemic stroke among Medicare beneficiaries. Stroke. 2013;44:3429–3435. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lainay C, Benzenine E, Durier J, et al. Hospitalization within the first year after stroke: the Dijon stroke registry. Stroke. 2015;46:190–196. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtman JH, Leifheit-Limson EC, Jones SB, et al. Predictors of hospital readmission after stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2010;41:2525–2533. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.599159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis M, Lewis S, Cranswick G, et al. FOOD: a multicentre randomised trial evaluating feeding policies in patients admitted to hospital with a recent stroke. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:3–4. doi: 10.3310/hta10020. 9-10, 1-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts PS, Divita MA, Riggs RV, et al. Risk factors for discharge to an acute care hospital from inpatient rehabilitation among stroke patients. PM R. 2014;6:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.08.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reker DM, Hamilton BB, Duncan PW, et al. Stroke: who’s counting what? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AHRQ . Prevention quality indicators overview. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potack JZ, Chokhavatia S. Complications of and controversies associated with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: report of a case and literature review. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Fernandez M, Gardyn M, Wyckoff S, et al. Validation of ICD-9 Code 787.2 for identification of individuals with dysphagia from administrative databases. Dysphagia. 2009;24:398–402. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George BP, Kelly AG, Schneider EB, et al. Current practices in feeding tube placement for US acute ischemic stroke inpatients. Neurology. 2014;83:874–882. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]