Abstract

The reduction of N2 to NH3 by Mo-dependent nitrogenase at its active-site metal cluster FeMo-cofactor utilizes reductive elimination (re) of Fe-bound hydrides with obligatory loss of H2 to activate the enzyme for binding/reduction of N2. Earlier work showed that wild type nitrogenase and a nitrogenase having amino acid substitutions in the MoFe protein near FeMo-cofactor can catalytically reduce CO2 by 2 or 8 electrons/protons to carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4) at low rates. Here, it is demonstrated that nitrogenase preferentially reduces CO2 by 2 electrons/protons to formate (HCOO−) at rates >10 times higher than rates of CO2 reduction to yield CO and CH4. Quantum mechanical (QM) calculations on the doubly-reduced FeMo-cofactor with a Fe-bound hydride and S-bound proton (E2(2H) state) favor a direct reaction of CO2 with the hydride (‘direct hydride transfer’ reaction pathway), with facile hydride transfer to CO2 yielding formate. In contrast, a significant barrier is observed for reaction of Fe-bound CO2 with the hydride (‘associative’ reaction pathway), which leads to CO and CH4. Remarkably, in the direct hydride transfer pathway, the Fe-H behaves as a hydridic hydrogen, whereas in the associative pathway it acts as a protic hydrogen. MoFe proteins having amino acid substitutions near FeMo-cofactor (α-70Val→Ala, α -195His→Gln) are found to significantly alter the distribution of products between formate and CO/CH4.

Keywords: FeS cluster, Mechanism, Calculation, Metalloenzyme

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Nitrogenase catalyzes the reduction of dinitrogen (N2) to two ammonia (NH3) molecules,1 the largest contribution of ‘fixed nitrogen’ in the global biogeochemical nitrogen cycle.2 The reduction of N2 by Mo-dependent nitrogenase occurs at the FeMo-cofactor (7Fe-9S-1Mo-1C-1R homocitrate) contained within the nitrogenase MoFe protein (Fig 1a).3 Early kinetic studies indicated that FeMo-co must accumulate 4 electrons and protons (the E4(4H) state in the Lowe and Thorneley (LT) kinetic model) before the first step of N2 reduction,4 with the electrons delivered one at a time by the nitrogenase Fe protein,5 before N2 can be reduced, and that N2 binding coincides with the evolution of one equivalent of H2.6 Recently, analysis of the reactivity of proteins having amino acid substitutions, coupled with advanced spectroscopic studies of trapped intermediates isotopically labelled at the metal ions and substrates, has identified the intermediates postulated in this kinetic model.7–10 In particular, the reactive E4(4H) state has been revealed to contain two [Fe-H-Fe] bridging hydrides bound to a particular 4Fe-4S FeMo-co face (Fig 1b).7,8,11–13 As delivery of each electron is coupled to delivery of a proton, the E4 state is also assumed to contain 2 bound protons, likely bound to one or more of the sulfides of FeMo-co, hence the notation, E4(4H).9

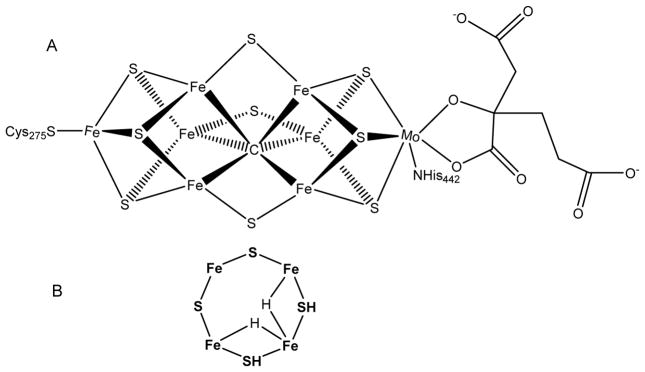

Figure 1. FeMo-co of nitrogenase.

(A) Shown is FeMo-co with the α-Cys275 and α-His442 ligands and R-homocitrate (right). (B) One FeS face of FeMo-co is shown in the proposed bridging dihydride E4 state with two protons associated with sulfides. Not shown are several possible binding modes for the hydrides.

These experiments have further established that E4(4H) necessarily undergoes a loss of H2 during N2 binding/reduction, with the consequence that N2 reduction requires the delivery of a total of eight electrons/protons to the MoFe protein.12,13 This kinetically and thermodynamically reversible equilibrium binding of N2 to E4(4H) with H2 release has been proposed to involve reductive elimination (re) of the two hydrides forming H2, with concomitant reduction of N2 to a diazenido-level, metal-bound state M-(2N2H) (Fig 2, right side).9 Four subsequent electron/proton addition steps ultimately lead to the formation of two NH3 molecules and return FeMo-co to the resting (E0) state.

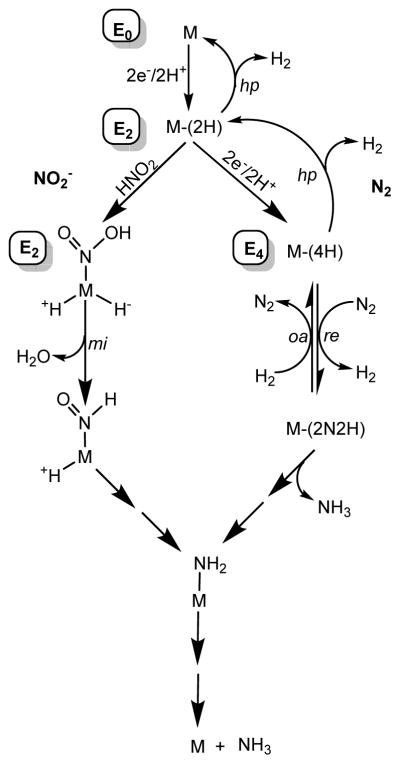

Figure 2. Pathways for N2 and nitrite reduction.

Proposed pathways for H2 evolution (top), N2 reduction (right), and nitrite reduction (left), where M represents FeMo-co and the En state is noted. Hydride protonation (hp) is proposed to make H2, reductive elimination (re) for the activation of N2, while hydride migratory insertion (mi) has been proposed in the reduction of nitrite. Oxidative addition (oa) is shown for the binding of H2 concomitant with the release of N2 (right).

In addition to reducing N2 and protons, nitrogenase can reduce a number of small, multiply bonded compounds.14,15 Reduction of acetylene (C2H2) to ethylene (C2H4) is commonly used as an activity assay.16 We have reported acetylene reduction involves migratory insertion (mi) of bound C2H2 into a Fe–H bond to form an Fe–alkenyl intermediate, followed by reductive elimination of ethylene.17 Substitution of one or more ‘gatekeeper’ amino acids in the protein environment surrounding FeMo-co has been shown to relax the native enzyme’s size restriction on compounds that can gain access to FeMo-co for reduction, and to control the distribution of electrons between competing substrates.18 Most recently, we demonstrated that nitrogenase remodeled in this way can reduce nitrite (NO2−) to NH3.19 Intermediates along the NO2− reaction pathway were trapped by a freeze-quench method and characterized by Q-band ENDOR/Non-Kramers ESEEM spectroscopy. A pair of intermediates consistent with M-NH2 and M-NH3 (M = FeMo-co) species were trapped and identified with intermediates previously trapped during the reduction of diazene (HN=NH) and hydrazine (H2N-NH2).11 From this observation, and the fact that the two-electron/two-proton trapped state of the FeMo-co likely contains a metal-bound hydride and a proton (E2(2H)), we proposed a mechanism for NO2− reduction that again invokes migratory hydride insertion, with the substrate fragment of the M-NOOH state inserting into the M-H−, with proton addition and loss of H2O to yield the M-NHO intermediate (Fig 2, left).19 Subsequent reduction leads to the observed M-NH2 and M-NH3 intermediates and ultimate release of NH3.

From these findings, it can be seen that hydrides on FeMo-cofactor can undergo at least three different types of reaction: (i) reductive elimination (re) of H2 by the state containing two hydrides activates FeMo-co for N2 binding and reaction; (ii) and migratory insertion (mi) into the M-H by substrates, such as acetylene and nitrite, and most likely some of the N2Hx intermediate states of N2 reduction, and (iii) finally, deactivation of FeMo-cofactor through hydride protonation and release of H2.9

It has been demonstrated that in a MoFe protein having substituted amino acids near FeMo-co, carbon dioxide (CO2) can be catalytically reduced by 2 or 8 electrons/protons to carbon monoxide (CO) or methane (CH4) at low rates.20,21 A better understanding of the mechanism by which nitrogenase catalyzes CO2 reduction would provide insight into the challenging and environmentally important reduction of CO2. Here, we report that wild type nitrogenase reduces CO2 by two electrons/protons to make formate (HCOO−) at rates up to 10-times faster than the rates of CO and CH4 formation reported earlier. To understand the alternative reaction mechanisms, we have explored possible pathways for CO2 reduction on FeMo-co using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. These pathways involve reactions of Fe-hydrides and yield energies that are consistent with the observed product distribution for CO2 reduction. In addition, we show that amino acid substitutions near FeMo-co in the MoFe protein can significantly alter the product distribution between formate and CO/CH4.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and protein purification

All reagents were obtained from SigmaAldrich (St.Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ) and were used without further purification. Carbon dioxide (CO2) was purchased from Air Liquide (Walnut Creek, CA) and methane from Air Gas (Radnor, PA). Azotobacter vinelandii strains DJ995 (wild-type), DJ997 (α-195Gln), DJ1310 (α-70Ala), and DJ1316 (α-70Ala/α-195Gln) were grown, and the corresponding nitrogenase MoFe proteins having a seven-His tag addition near the carboxyl-terminal end of the α-subunit, were expressed and purified as previously described.22 Protein concentrations were determined by the Biuret assay using bovine serum albumin as standard. Handling of proteins and buffers was done in septum-sealed serum vials under an argon atmosphere or on a Schlenk vacuum line. All gases and liquids were transferred using gas-tight syringes.

Carbon dioxide reduction assay

CO2 reduction to CH4 was carried out at 0.45 atm CO2 and 0.55 atm Ar in 9.4 mL serum vials. To achieve 0.45 atm CO2, sealed serum vials were first deoxygenated with Ar. To the gas phase was added 6.1 mL of CO2 gas. To each vial was added 2 mL of an assay buffer consisting of 100 mM sodium dithionite, a MgATP regenerating system (13.4 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 60 mM phosphocreatine, 0.6 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, and 0.4 mg/mL creatine phosphokinase) in 100 mM MOPS buffer at pH 7.2 and the samples were incubated at room temperature to allow equilibration. The pH of the solution was measured to be ~ 6.7 resulting in a total concentration of CO2 and HCO3− of ~ 48 mM. MoFe protein was added and then the assay vials were ventilated to atmospheric pressure. Reactions were initiated by the addition of Fe protein and incubated at 30°C for the noted times. To each was added 500 μL of 400 mM EDTA at pH 8.0 to quench the reaction. From the gas phase, 300 μL was injected into a gas chromatograph with a flame ionization detector to quantify CH4. From the same samples, 50 μL of the gas phase was injected into a gas chromatograph with a thermal conductivity detector to quantify H2.

CO2 reduction to CO was measured using a hemoglobin (0.3 mg/mL) binding assay as described before.23 The buffer composition was the same as used for CO2 reduction to CH4 except 0.3 mg/mL hemoglobin was added in the assay buffer. 1.2 mL of assay buffer was transferred to 9.4 mL serum vial containing 0.45 atm CO2 and 20 min of equilibration time was allowed. Then, MoFe protein was added (0.5 mg/mL). One mL of CO2 saturated assay buffer was transferred to a 2.2 mL (l cm path length) quartz cuvette that had been modified to maintain a defined gas atmosphere. Fe protein was added to initiate the reaction. The increase in the absorbance at 418 nm corresponding to the binding of CO to the hemoglobin was monitored using an UV-visible spectrophotometer.

CO2 reduction to formate was detected by NMR spectroscopy, which eliminates a difficulty experienced in earlier work.21 The measurements here used a 300 MHz JOEL NMR spectrometer. To a 9.4 mL vial was added 0.026 mg of H13CO3− under Ar. To this vial was added 2 mL of anaerobic assay buffer, followed by addition of 1 mg MoFe protein. The reaction was initiated by addition of 1 mg of Fe protein. The reaction was allowed to run for 1 h, after which 500 μL of the liquid phase was transferred to a sealed NMR tube. A D2O containing capillary tube was placed inside of the NMR tube. 13C NMR was carried out to ascertain the formation of formate during the reduction of H13CO3− (Fig. S1, Left). The NMR probe temperature was set to 25 °C and the magnetic field was locked using D2O as solvent. The probe was tuned for both 1H and 13C nuclei. Single pulse decoupled NMR was carried out using the following parameters:- X-offset 90 ppm, X-sweep 180 ppm, scan 6000, pulse X-angle 30, relaxation delay 3 s, and both NOE and decoupling on. The 1JC-H for formate was also determined using the same parameters except turning the decoupling parameter off (Fig S1, Right).

A colorimetric assay was used to quantify the formation of formate using a protocol previously reported.24 In a 9.4 mL serum vial, 3.5 mL of 100% acetic anhydride, 50 μL of 30% (w/v) sodium acetate, and 1 mL isopropanol solution containing 0.5% (w/v) citric acid and 10% (w/v) acetamide were added. To this assay solution was added 500 μL of sample with 5 hours of incubation time at room temperature. Using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer, the absorbance was determined at 514 nm (Fig. S2). The formate standard calibration curve was made as follows: first, the assay buffer with MoFe and Fe protein was left to turnover for an hour under an Ar atmosphere; then, the appropriate concentration of formate was added. From this, 500 μL of samples was used for the colorimetric assay.

The other possible products, methanol or formaldehyde, were not detected as products following turnover with 13CO2 as monitored using 13C NMR (Fig. S3).

Calculations

Calculations were performed on the E2 state of the FeMo-co with a simplified model of the FeMo-co and the enzyme environment. The FeMo-co ligands α-Cys275, α-His442 (Azotobacter vinelandii numbering), and R-homocitrate were modeled as methylthiolate, imidazole, and dimethyl glycolate, respectively (Fig S4). The atoms of the protein and FeMo-co that were truncated were kept frozen to their crystallographic position. The electronic structure of the FeMo-co was described within the DFT framework using the gradient-corrected Becke25 exchange and Perdew26 correlation functionals. The Ahlrichs VTZ basis set was employed for all Fe atoms,27 the Los Alamos National Laboratory basis set LANL2TZ with an effective core potential was employed for the Mo atom28, and the 6-311++G** basis set was employed for all atoms coordinated to metal atoms, including protic and hydridic hydrogen atoms, and finally the 6-31G* basis29 set was adopted for all of the other atoms. Harmonic vibrational frequencies were calculated at the optimized geometries using the same level of theory to estimate the zero-point energy and the thermal contributions (298.1 K and 1 atm) to the gas-phase free energy. The protein environment around FeMo-co was described with a polarizable continuum with a dielectric constant ε = 10.30 Standard state corrections were applied to solvation free energies. Different locations of the hydridic and protic hydrogen atoms on the reactive face of the FeMo-cofactor (identified by the atoms Fe2, Fe3, Fe6, and Fe7) were explored. All of them showed similar reactivity toward CO2 reduction to formate. For this reason most of the calculations were performed on the lowest-free energy E2 state, where the hydric hydrogen is asymmetrically located between Fe2 and Fe6 (Fe2-H and F6-H distances of 1.51 Å and 2.36 Å) and the protic hydrogen is bound to S2B (Fig S4).

Results

CO2 reduction to formate

Earlier studies revealed that the wild type MoFe protein reduces CO2 to CO at a very low rate (~0.03 nmol CO/nmol MoFe protein/min at 30°C),20 a result repeated here (Table 1). For comparison, under optimal conditions, wild type nitrogenase catalyzes proton reduction to H2 at a rate of 550 ± 34 nmol H2/nmol MoFe protein/min, acetylene reduction at a rate 452 ± 14 nmol ethylene/nmol MoFe protein/min, and N2 reduction at a rate of 162 ± 2 nmol NH3/nmol MoFe protein/min at 30°C. With these activity values as reference, in an earlier report, whose results are also repeated here, we find that under CO2, most of the electron flux through nitrogenase goes to the reduction of protons to make H2, which occurs with a roughly 3×103-fold greater rate (83 nmol H2/nmol MoFe protein/min at 30°C) than CO formation, and no CH4 was detected. CO2 suppresses the H2 evolution rate compared to the rate observed under Ar. In a subsequent study, it was found that substitution of two amino acids within the MoFe protein located near the active site FeMo-co, α-70Val→Ala/α-195His→Gln, resulted in a MoFe protein that could reduce CO2 by 8 e−/H+ to CH4 at a rate of ~1 nmol CH4/nmol MoFe protein/min, with most of the electron flux going to proton reduction (~62 nmol H2/nmol MoFe protein/min).21 The reduction of CO2 to CO and CH4 are expected to follow the same reaction pathway, with CO formed after 2e−/H+ reduction and CH4 after addition of a further 6 e−/H+.

Table 1.

Product accumulation and electron distribution for wild-type MoFe protein

| Gas | Product

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2

|

HCOO−

|

CH4

|

CO

|

|||||

| nmol/nmol/mina | % e− | nmol/nmol/min | % e− | nmol/nmol/min | % e− | nmol/nmol/min | % e− | |

|

|

||||||||

| Ar | 83 ± 1.55 | 100 | NDb | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| CO2 | 70 ± 1.8 | 87 | 9.8 ± 1.5 | 12 | ND | ND | 0.03 | 1 |

nmol product/nmol MoFe protein/min. Rates are the average over the 60 min assay at 30°C with 1 mg MoFe protein and 1 mg Fe protein. CO2 was at a partial pressure of 0.45 atm.

ND, not detected.

An examination of CO2 reduction catalyzed by a range of small molecules that utilize metal hydrides reveals that an alternative product for CO2 reduction is formate (HCOO−).31–35 The pathway to CO and CH4 formation is believed to involve the addition of H to the O atom of CO2, whereas the pathway to HCOO− formation is believed to involve the addition of H to the C atom of CO2.36,37 In this context, we tested whether wild type nitrogenase could reduce CO2 to HCOO−, a reaction that had not been reported before.

When wild type nitrogenase was allowed to turn over for 60 min in the presence of 13CO2 and the absence of N2, formation of formate was detected by 13C NMR, which showed a peak at 171.083 ppm associated with H13COO− (Fig S1). Since 13C NMR is not ideal for quantifying products, we used a colorimetric assay to quantify formate (Fig S2). As can be seen from the data in Table 1, the wild-type MoFe protein reduces CO2 to formate at a quantifiable rate (~10 nmol HCOO−/nmol MoFe protein/min at 30°C). Under these conditions, ~12% of the electron flux through nitrogenase goes to produce formate, whereas about 1% goes to form CO. The remaining electron flux (87%) makes H2. Thus, the present measurements reveal that the conversion of CO2 to formate represents a significant catalytic process for nitrogenase.

Does CO2 reduction involve reductive elimination?

Although the reduction of CO2 to formate involves only 2e−/H+, and likely involves binding at the E2 state, the 2/8 e−/H+ reduction to CO/CH4 could occur by a process that parallels the reduction of N2, namely a reductive elimination (re) mechanism (Fig 2, right). 10 A key feature of the re mechanism for N2 reduction is the reversible reductive elimination/oxidative addition in which the FeMo-co is activated for the binding/reduction of N2 through the re loss of H2. As a result of this reversible equilibrium, H2 inhibits N2 reduction to NH3 by displacement of the bound N2 (Fig 2, right).13 This inhibition is recapitulated here by activity measurements that show inclusion of 0.8 atm H2 in place of 0.8 atm of Ar along with 0.2 atm N2, results in ~50% inhibition of the NH3 formation rate for wild type nitrogenase (Fig 3). If CO2 reduction also followed a reversible re mechanism, this process likewise should be inhibited by the addition of H2. However, as can been seen (Fig 3, panel B), the inclusion of 1 atm H2 caused no detectable inhibition of the reduction of CO2 to formate, relative to the Ar control. Inclusion of 0.85 atm of H2 also had no effect on the rate of reduction of CO2 to CO compared to the Ar control (Fig 3, panel C). These results indicate that CO2 reduction catalyzed by nitrogenase does not involve the reversible re step that is operative in N2 reduction.

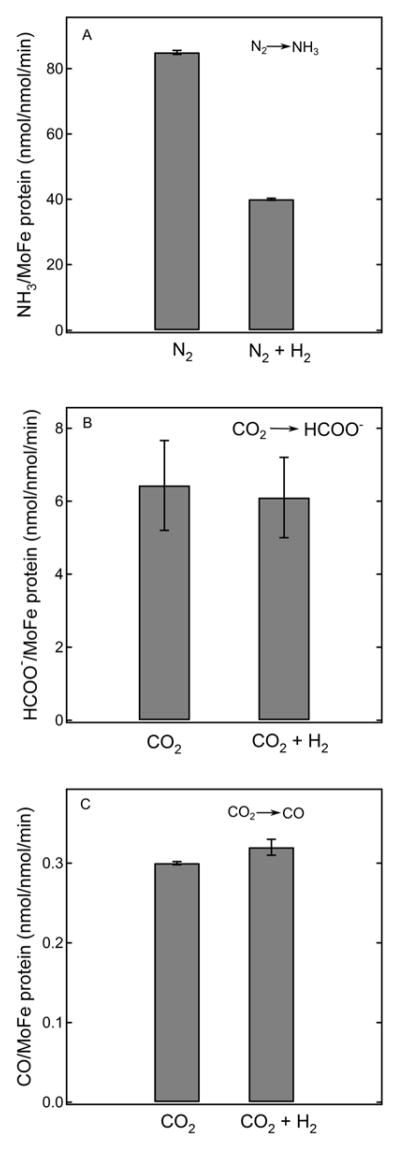

Figure 3. Effect of H2 on N2 and CO2 reduction.

Specific activities (nmol product/nmol MoFe protein/min) are shown for N2 reduction to NH3 (panel A), CO2 reduction to formate (panel B), and CO2 reduction to CO (panel C) either with or without the addition of H2. All assays were done with wild type MoFe protein at 30°C as described in the Materials and Methods. Reaction conditions were: 0.2 atm N2 + 0.8 atm Ar or 0.2 atm N2 + 0.8 atm H2 for panel A; 40 mM HCO3− + 1 atm Ar or 40 mM HCO3− + 1 atm H2 for panel B; 0.15 atm CO2 + 0.85 atm Ar or 0.15 atm CO2 + 0.85 atm H2 for panel C.

Alternative mechanisms of CO2 reduction by hydride insertion

With the re mechanism having been eliminated, the most plausible mechanisms for CO2 reduction catalyzed by nitrogenase involves migratory insertion of CO2 into the Fe-H bond of reduced FeMo-co, in analogy to the proposed mechanisms of C2H2 and NO2− reduction.17,19 Fig 4 presents two alternative hydride insertion reaction pathways for the reduction of CO2 to formate based on studies of inorganic complexes: the ‘direct hydride transfer’ reaction of CO2 with the FeMo-co Fe-H, and an ‘associative’ pathway with hydride insertion by Fe-bound CO2.38 As incorporated into Fig 4, the formation of CO and CH4 can be viewed as a shunt off of the associative pathway. The ~10:1 product ratio of formate:CO/CH4 observed for CO2 reduction by wild-type nitrogenase indicates that the pathways to formate formation are energetically favorable compared to the pathway to CO/CH4 formation.

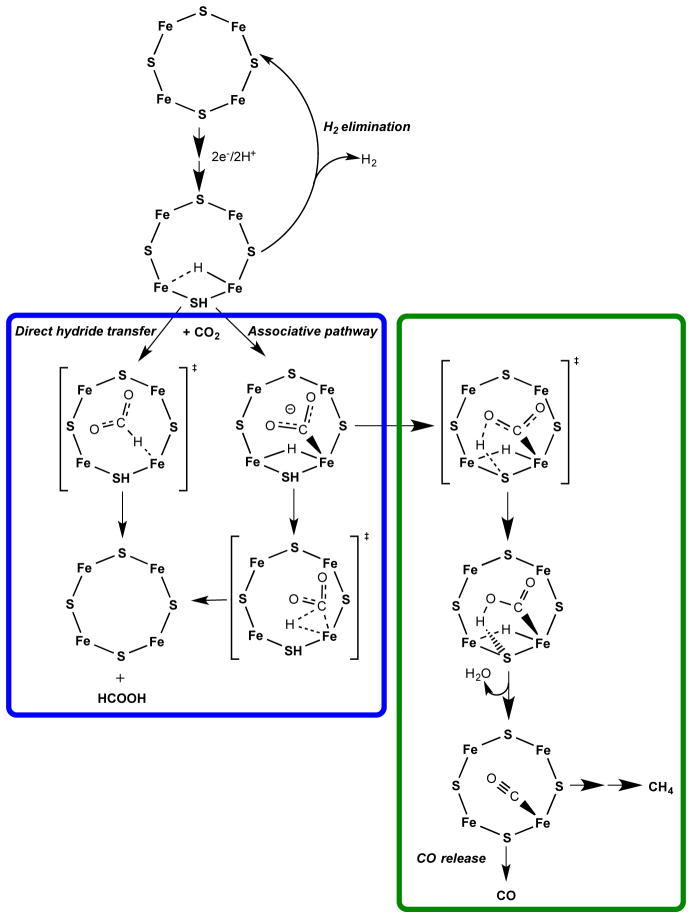

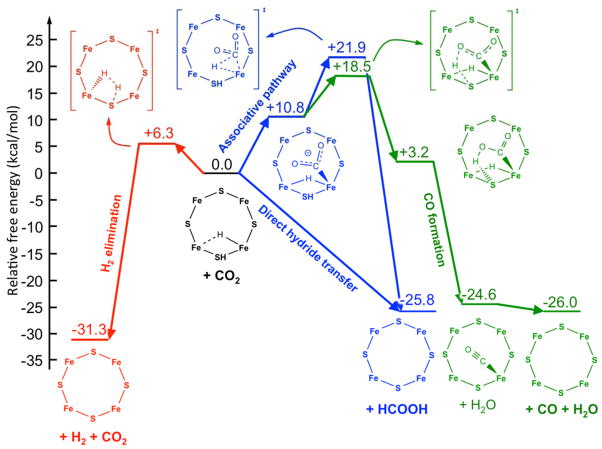

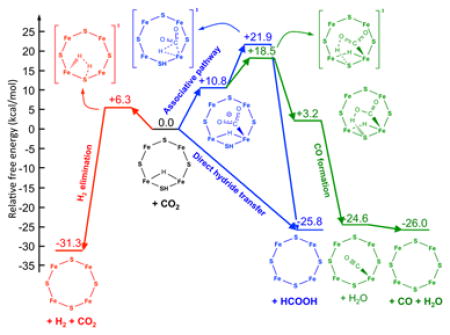

Figure 4. Possible pathways for CO2 reduction.

CO2 activation at one FeS face of the E2 state of FeMo-co is shown. The E2 state is proposed to contain a single Fe-hydride and a proton bound to a sulfide shown bound to one face of FeMo-co. Reduction to formate (blue box) can go by either a direct hydride transfer or an associative pathway. A pathway to formation of CO and CH4 is shown in the green box. Six additional electrons and protons are added to the bottom structure to achieve reduction to CH4.

Testing possible pathways by calculations

We used DFT calculations to evaluate the possible pathways for CO2 reduction catalyzed at FeMo-co, presented in Fig 4. The starting point for the calculations is the E2(2H) state, which has accumulated 2 [e−/H+], which optimization shows to be present as 1 Fe-bound hydride and 1 sulfido-bound proton (Fig S4).

Geometry optimization in the presence of CO2 in the vicinity of the Fe-hydride center of the E2(2H) state leads to spontaneous ‘direct hydride’ transfer to carbon, with the formation of formate (Fig 5, blue pathway). An analysis of the electronic properties of FeMo-co during this process, carried out within the natural bond orbital (NBO) framework,39 revealed a strong charge transfer from the σ(Fe-H) bonding orbital to the π*(C=O) anti-bonding orbital (see Supporting Information), which results in the heterolytic Fe-H → Fe+ + H− bond cleavage and the transfer of the hydride to CO2. In turn, according to the adopted computation model, the newly formed formate promptly deprotonates the S-H of FeMo-co with the formation of formic acid. Isomers of FeMo-co differing in the location of the proton and the hydride provided similar scenarios. These results suggest that the hydricity of the E2 state, ΔGH- (HCOO−), the free energy input required for loss of a hydride (called hydricity),40 is sufficiently low that this state can transfer a hydride to CO2 to generate formate, i.e., the hydricity is below that of formate (HCOO− → CO2 + H−, ΔGH- (HCOO−) = +24.1 kcal/mol).41

Figure 5. Computed free energy diagram for CO2 reduction and H2 formation occurring at the E2 state of FeMo-cofactor.

Calculations start with the E2 state that contains one bridging hydride and one H+ associated with a sulfide. This starting state is assigned a relative free energy of 0 kcal/mol and all other free energy changes are relative to this state. Going to the left (red) is the pathway for heterolytic formation of H2. To the right (blue) is the direct hydride transfer or associative pathway going to a CO2 bound to FeMo-co. Further to the right (green) is the pathway to CO formation.

In contrast, the ‘associative’ pathway for CO2 reduction, whereby CO2 first coordinates to a Fe ion via the C atom, was found to be thermodynamically and kinetically unfavorable. Indeed, the formation of the E2(2H)-CO2 adduct is endergonic by ΔG0 = +10.8 kcal/mol, and the calculated barrier for the subsequent hydrogen transfer to CO2 is ΔG‡ = +11.1 kcal/mol (Fig 5, blue pathway). The computed overall barrier for CO2 reduction to HCOOH via the associative pathway is +21.9 kcal/mol. The NBO analysis of the associative pathway indicates that the hydrogen transfer is driven by a strong charge transfer from σ(Fe-C) of the Fe-bound CO2 moiety to σ*(Fe-H) and from FeMo-co localized orbitals to CO2, which results in the heterolytic Fe-H → Fe− + H+ bond dissociation with the net transfer of a proton to the C atom and the breaking of the Fe-C bond. During the proton transfer the two σ(Fe-C) electrons are used to make the C-H bond. The different behaviors of the Fe-H in the direct hydride transfer pathway and the associative pathway are truly remarkable: in the former the Fe-H hydrogen behaves as a hydridic hydrogen and in the latter as a protic hydrogen.

A pathway leading to the formation of CO from E2(2H)-CO2 was also found. The lowest free energy path for this reaction starts with the transfer of the protic S-H hydrogen to one of the oxygen atoms of CO2, which is an exergonic (ΔG0 = −7.6 kcal/mol) reaction with an activation barrier of ΔG‡ = +7.7 kcal/mol (Fig 5, green pathway). The reaction proceeds with the transfer of the Fe-H hydrogen (as a proton) to that oxygen, which results in the spontaneous and very exoergic dissociation of a water molecule (ΔG0 = −27.8 kcal/mol), followed by the slightly exergonic dissociation of CO (ΔG0 = −1.4 kcal/mol). Thus, in this case, the Fe-H again behaves as a proton donor.

For completeness, we also investigated computationally the release of H2 from the E2(2H) state. We found that formation of H2 is a kinetically facile (ΔG‡ = +6.3 kcal/mol) and very exergonic process (ΔG0 = −31.3 kcal/mol; Fig 5, red pathway). This result is consistent with our recent explanation of why H2 cannot reduce FeMo-co: it is too far ‘uphill’.9 As with the direct hydride pathway, the Fe-H behaves as a hydride that is protonated by S-H, with the overall H2 elimination driven by a σ(Fe-H) to σ*(S-H) charge transfer.

Experimentally altering product distribution during CO2 reduction through MoFe protein modification

We sought to alter the selectivity of CO2 reduction to different products by changing the environment around the active site FeMo-co by amino acid substitutions (Fig. S5). Earlier studies identified the α-70Val and α-195Gln as key residues that, when substituted, alter the reactivity of nitrogenase toward substrate reduction.21,42,43 We therefore assessed how changing these amino acids would alter the ratio of the products when reacting with CO2 (Fig 6 and Table S1).

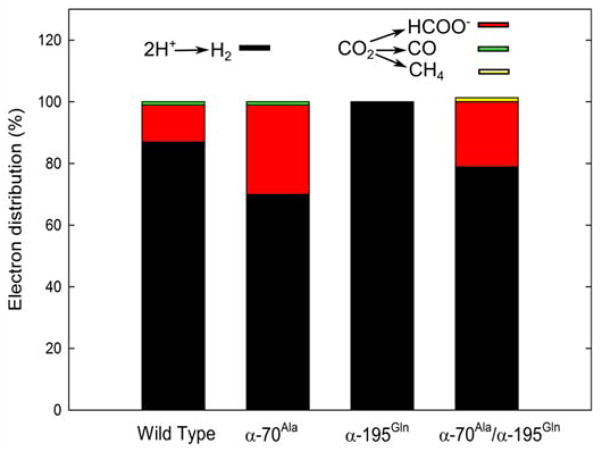

Figure 6. Product distribution under CO2 for different MoFe proteins.

Shown are the electron distribution to different products with CO2 for the wild-type, α-70Ala, α-195Gln, and α-70Ala/α-195Gln MoFe proteins. Assay conditions: 1 mg MoFe, 6 mg Fe, 0.45 atm CO2 with an incubation time of 60 min at 30°C.

For the wild type MoFe protein under these conditions, about 10% of the electrons are utilized for CO2 reduction, formate being the primary product, with a trace of CO. The remaining 87% of electron flux is used to make H2. In the α-70Val->Ala substituted MoFe protein, the electron flux is shifted in favor of CO2 reduction to make formate (~30%), with the remainder going to make H2. The α-195His→Gln substituted MoFe protein shows essentially 100% electron flux going to make H2. Substitution of both α-70Ala/α-195Gln, however, results in a protein that shows considerable reduction of CO2 to formate (~20%), but with detectable formation of CH4 (~2%), the remaining flux going to make H2. These findings reveal that subtle changes around the active site can indeed alter the reaction pathway energy landscape, thereby altering the distribution of electrons passing through nitrogenase to CO2 reduction.

Discussion

The observation reported here that nitrogenase can reduce CO2 to formate, together with the earlier reports of reduction to CO20 and to CH4,21 makes nitrogenase unique in its ability to catalyze the reduction of CO2 to a range of products. For example, CO dehydrogenase and formate dehydrogenase efficiently catalyze 2 e−/H+ reduction of CO2 to CO and HCOO−, respectively, but do not catalyze reduction of CO2 to CH4.44,45 Indeed, few known organometallic complexes can reduce CO2 to this suite of products, 46,47 making the study of the mechanism of CO2 reduction by nitrogenase important to gain mechanistic insights into CO2 reduction. Studies during the last few years have revealed the presence of Fe-bound hydrides in reduced states of nitrogenase, as well as their importance in the nitrogenase N2 reduction mechanism.9 Activation of nitrogenase by the accumulation of 4e−/H+ on FeMo-co (E4(4H) state) results in the storage of these reducing equivalents as two bridging hydrides (Fe-H-Fe) in the central E4(4H) state. There is ample evidence now that the binding of N2 to this activated state is associated with the loss of H2 by a reductive elimination (re) mechanism, with two hydrides combining to make H2 coupled to the reduction of N2 to a diazene-level state.9–13 It has been shown that the binding of N2 to the E4(4H) state with loss of H2 involves the thermodynamically and kinetically reversible re equilibrium (eqn 1)

| (eqn 1) |

that activates FeMo-co for the addition of the first two electrons and protons to N2, the most difficult step in N2 reduction. Subsequent steps of reduction are likely to involve migratory insertion (mi) of this bound species into M-H on FeMo-co, ultimately leading to the formation of two NH3. The ability of FeMo-co to simultaneously hold the partially reduced N2 species juxtaposed to one or more Fe-hydrides offers an attractive way to achieve the stepwise reduction of N2 all the way to NH3 without release of intermediates that might be toxic to the cell.

An important consequence of an obligatory loss of H2 during reduction of any substrate through a re equilibrium means that added H2 will inhibit reduction of the substrate through such a re mechanism by ‘driving’ the equilibrium to the left.13 The findings presented here, that CO2 reduction to formate and to CO and CH4 are not inhibited by H2, eliminates the possibility that CO2 binding and reduction is coupled to reversible re/oa mechanism in which N2 binding/reduction is coupled to the re loss of H2. This finding directed our attention to alternative mechanisms involving proton coupled electron transfer or migratory hydride insertion, as is proposed for CO dehydrogenase and formate dehydrogenase.44,45

Studies on inorganic metal-hydride complexes indicate there are two pathways for the participation of metal-hydrides in reduction of CO2 to formate.38 One is an associative pathway, in which CO2 binds through its C atom to a Fe of FeMo-co that has at least one bound hydride (Fig 4); the presence of a bound hydride increases the π back-donation ability of the metal and the nucleophilicity of the metal. The bound C then undergoes mi into the Fe-H bond and accepts a proton bound to sulfur to release HCOOH. Alternatively, (Fig 4) in a direct hydride transfer mechanism, CO2 does not bind to a metal ion, but rather the C atom of CO2 associates with the metal bound hydride and the hydride is directly transferred to the C of CO2, to generate formate with transfer of the proton bound to sulfur again giving HCOOH.

Both of these mechanisms seem reasonable and it would be difficult to distinguish between them from experimental evidence. Instead, this is an ideal situation where calculations can distinguish between possible pathways. Exploratory DFT calculations have been carried out by starting the reaction pathway from an E2(2H) state, the state with which CO2 is proposed to initially interact. It is expected that a substrate that normally reacts with E2(2H) can also react with the more highly activated, but less populated, E4(4H), as we showed to be the case for C2H2.12 Thus, it is also possible that CO2 interacts with the E4(4H) state in a way that does not involve a re mechanism, but this has not been explored here by calculations, as the catalytic importance of this process is certainly less. These calculations employed a simplified model of the nitrogenase active site, similar to previous investigations,48,49 which includes FeMo-co with truncated Cys, His, and homocitrate ligands, to examine the energetics of the possible direct hydride and associative reaction pathways, and, at the same time, to analyze the chemical bonding and the reorganization of the electron density distribution upon bond breaking and forming.

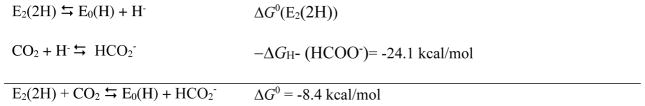

The calculations reveal a significant barrier between CO2 and formate along the associative pathway. For this pathway, the coordination of CO2 to E2(2H) is endergonic by +10.8 kcal/mol, with the overall activation free energy for forming formate being endergonic by +21.8 kcal/mol relative to the E2(2H) state. In contrast, the direct hydride pathway is found to have essentially no barrier. The absence of a barrier is notable, suggesting that the hydride donor ability of the Fe-H on the E2(2H) state is considerably more favorable (smaller hydridicity) than that of formate. Using the experimental hydride donor ability of formate in aqueous solution, ΔGH- (HCOO−)= 24.1 kcal/mol,41 as a reference value, we can obtain a conservative estimate of the hydricity of E2(2H) from the half reactions50 reported in the thermodynamic cycle of Scheme 1 as ΔG0(E2(2H)) = ΔG0 + ΔGH- (HCOO−). Using the ab initio value of ΔG0 = −8.4 kcal/mol for the free energy change of the hydride transfer reaction from E2(2H) to CO2, yields ΔG0(E2(2H)) = +15.7 kcal/mol.

Scheme 1.

Thermodynamic cycle for determining the hydride donor ability of E2(2H).

Following similar arguments, we can obtain an estimate of the pKa for the protonated E0(H) state of −9.1 pKa units. The extremely high acidity of E0(H) suggests that, in the formation of E1(H), E0 is first reduced then protonated probably through a proton coupled electron transfer reaction.

These calculations demonstrate that hydride-bound FeMo-co can act as a strong H− donor. On the other hand, the same hydride ligand can act as a proton donor in the less active associative pathway. These results highlight several of the numerous fallacies in a recent misanalysis of nitrogenase catalysis.48 A hydrogen atom bonded to a metal is defined formally as a hydride, and the present results show that it is incorrect to attempt to define an M-H moiety as a hydride or proton based on atomic point charges derived from electron density partitioning schemes, rather than reactivity (see Supporting Information). The calculations reported in the present paper, together with other recent reports, show little differences between atomic charges on H atoms bound to Fe or S, with variation smaller than differences between the different flavor of the partitioning scheme employed (Tables S2 and S4).48 Correspondingly, the NBO analysis reported here indicates that the Fe-H and S-H bonds are covalent with a small polarization as expected from the difference in electronegativity of the atoms involved (see Supporting Information). Nonetheless, the Fe-H and S-H bonds show dramatically different reactivity patterns. We also would like to point out that, as a consequence of the strong covalent character of the Fe-H and S-H bonds, during the accumulation of e−/H+ to form E2(2H) and, in turn, E4(4H), electrons are neither stored on the FeMo-co metal core, in particular on the Fe atoms, nor in hydridic H− atoms. Rather the added electrons are nearly equally shared between the atoms involved in the new chemical bonds as substantiated by the electron configurations reported in Table S4. Nonetheless, the energy associated with the formation of hydrides lowers the reactivity of FeMo-cofactor compared to what might be observed for a reduced metal-ion cofactor core with a proton on sulfide or elsewhere, as we have discussed.9

In contrast to the formation of formate, the reduction of CO2 to CO, and on to CH4, are likely to follow an associative reaction pathway, involving the binding of CO2 to FeMo-co through the C (Figs 4 and 5). The common early step in this pathway for both formate and CO formation is the endergonic coordination of the CO2 to the Fe of FeMo-co. On the pathway to CO formation, the H+ associated with the S has been modeled to interact with one O of the bound CO2, with the hydride bound to the Fe acting as a proton donor to the O, resulting in the reduction of the O to water and a bound CO. The overall barrier to the formation of the intermediate leading to CO is found to be +18.5 kcal/mol relative to the E2(2H) state. Thus, the calculations are consistent with the experimental observations that the wild type nitrogenase exhibits a larger formate/CO product ratio during CO2 reduction. The calculations indicate that the direct hydride transfer pathway will be substantially favorable compared to the associative pathway that leads to CO and CH4 production. For comparison, calculations were also done for the conversion of the E2(2H) state to the E0 +H2 state, revealing an exergonic process of −31.3 kcal/mol compared to the E2(2H) baseline state, with an activation barrier of 6.3 kcal/mol.

The present calculations thus would lead to the conclusion that in the presence of CO2, formate formation should be kinetically favored over H2 formation, which in turn should be favored over CO and CH4 formation. We observe instead that H2 formation dominates, followed by formate formation. The computational and experimental results can be easily reconciled by noting that the minimal model of nitrogenase employed in our calculations does not consider any entropic and steric contribution arising from the local environment around the FeMo-co. In addition, the protein electrostatic field is incorporated via a simple polarizable dielectric continuum. The reactive face of the FeMo-co is crowded by protein residues, most notably α-70Val, that is known to gate the access of substrates, but also several charged groups face the substrate binding region. All these contributions should be taken into account, and together are expected to introduce a sizeable barrier for the hydride transfer to CO2; such environmental effects are demonstrated by the changes in product ratios introduced by amino acid substitutions in the vicinity of the active sites on FeMo-co. We also point out that the presence of α-70Val can limit the access to a protonated S center and consequently introduce a barrier for the deprotonation process by formate discussed above.

In summary, wild type nitrogenase is shown here to be effective in CO2 reduction to formate. The most favorable pathway for formate production is calculated to be direct hydride transfer to the C with subsequent proton transfer from an SH. The alternative associative pathway to formate, the binding of CO2 to Fe followed by mi of the CO2 into Fe-H and protonation, is calculated to have a much higher energy barrier. The higher barrier on the associative pathway is consistent with the modest rates observed for CO formation, with essentially undetectable CH4 formation. The observation that substitution of amino acids around FeMo-co can alter the product distribution between formate and CO/CH4 reveals that subtle changes in the protein environment around FeMo-co can tune the energetics of the two pathways. Further experimental and computational studies may provide insights into how to design amino acid substitutions that influence the energetics of the competing pathways in favorable ways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is based upon work supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (LCS and DRD), the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Bio-Sciences (SR) and the NIH (GM 111097; BMH).

Abbreviations

- MoFe Protein

Molybdenum Iron Protein

- Fe Protein

Iron Protein

- FeMo-co

Iron Molybdenum Cofactor

- EPR

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance

- ENDOR

Electron Nuclear Double Resonance

- ESEEM

Electron Spin Echo Envelop Modulation

- NMR

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- DFT

Density Function Theory

- NBO

Natural Bond Orbital

Footnotes

Discussion of the natural bond order analysis, figures showing the NMR traces for determining formate, colorimetric formate assay, the structure of the FeMo-co model used for DFT calculations, and tables of products for different variant MoFe proteins. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubsacs.org.

References

- 1.Burgess BK, Lowe DJ. Chem Rev. 1996;96(7):2983–3012. doi: 10.1021/cr950055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smil V. Enriching the earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the transformation of world food production. MIT Press; Cambridge, Mass: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah VK, Brill WJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74(8):3249–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorneley RNF, Lowe DJ. Molybdenum Enzymes. In: Spiro TG, editor. Metal Ions in Biology. Vol. 7. Wiley-Interscience Publications; New York: 1985. pp. 221–284. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hageman RV, Burris RH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75(6):2699–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorneley RN, Lowe DJ. Biochem J. 1984;224:887–894. doi: 10.1042/bj2240887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Igarashi RY, Laryukhin M, Dos Santos PC, Lee H-I, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(17):6231–6241. doi: 10.1021/ja043596p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukoyanov D, Barney BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(5):1451–1455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610975104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman BM, Lukoyanov D, Yang ZY, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Chem Rev. 2014;114(8):4041–4062. doi: 10.1021/cr400641x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman BM, Lukoyanov D, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(2):587–595. doi: 10.1021/ar300267m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukoyanov D, Yang ZY, Barney BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(15):5583–5587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202197109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang ZY, Khadka N, Lukoyanov D, Hoffman BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(41):16327–16332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315852110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukoyanov D, Yang ZY, Khadka N, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(10):3610–3615. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seefeldt LC, Yang ZY, Duval S, Dean DR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827(8–9):1102–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivera-Ortiz JM, Burris RH. J Bacteriol. 1975;123(2):537–545. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.2.537-545.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dilworth MJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;127(2):285–294. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(66)90383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HI, Sørlie M, Christiansen J, Yang TC, Shao J, Dean DR, Hales BJ, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(45):15880–15890. doi: 10.1021/ja054078x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer SM, Niehaus WG, Dean DR. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 2002:802–807. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw S, Lukoyanov D, Danyal K, Dean DR, Hoffman BM, Seefeldt LC. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(36):12776–12783. doi: 10.1021/ja507123d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seefeldt LC, Rasche ME, Ensign SA. Biochemistry. 1995;34(16):5382–5389. doi: 10.1021/bi00016a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang ZY, Moure VR, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(48):19644–19648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213159109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christiansen J, Goodwin PJ, Lanzilotta WN, Seefeldt LC, Dean DR. Biochemistry. 1998;37(36):12611–12623. doi: 10.1021/bi981165b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonam D, Murrell SA, Ludden PW. J Bacteriol. 1984;159(2):693–699. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.693-699.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sleat R, Mah RA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47(4):884–885. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.4.884-885.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becke AD. Phys Rev A. 1988;38(6):3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perdew JP. Phys Rev B. 1986;33(12):8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schäfer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R. J Chem Phys. 1992;97(4):2571–2577. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy LE, Hay PJ, Martin RL. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4(7):1029–1031. doi: 10.1021/ct8000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ditchfield R. J Chem Phys. 1971;54(2):724–728. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klamt A, Schüürmann G. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2. 5. 1993. pp. 799–805. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang P, Cheng C, Chen Z, Schauer CK, Meyer TJ, Brookhart M. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(12):5500–5503. doi: 10.1021/ja300543s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugh JR, Bruce MRM, Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ. Inorg Chem. 1991;30(1):86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmeier TJ, Dobereiner GE, Crabtree RH, Hazari N. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(24):9274–9277. doi: 10.1021/ja2035514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ. Organometallics. 1986;5(7):1500–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rail MD, Berben LA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(46):18577–18579. doi: 10.1021/ja208312t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machan CW, Sampson MD, Kubiak CP. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(26):8564–8571. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song J, Klein EL, Neese F, Ye S. Inorg Chem. 2014;53(14):7500–7507. doi: 10.1021/ic500829p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar N, Camaioni DM, Dupuis M, Raugei S, Appel AM. Dalton Trans. 2014:11803–11806. doi: 10.1039/c4dt01551g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed AE, Curtiss LA, Weinhold F. Chem Rev. 1988;88(6):899–926. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sieh D, Lacy DC, Peters JC, Kubiak CP. Chem Eur J. 2015 doi: 10.1002/chem.201500463. n/a – n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Connelly SJ, Wiedner ES, Appel AM. Dalton Trans. 2015;44(13):5933–5938. doi: 10.1039/c4dt03841j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim CH, Newton WE, Dean DR. Biochemistry. 1995;34(9):2798–2808. doi: 10.1021/bi00009a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dilworth MJ, Fisher K, Kim CH, Newton WE. Biochemistry. 1998;37(50):17495–17505. doi: 10.1021/bi9812017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Can M, Armstrong FA, Ragsdale SW. Chem Rev. 2014;114(8):4149–4174. doi: 10.1021/cr400461p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mondal B, Song J, Neese F, Ye S. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2015;25:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jessop PG, Ikariya T, Noyori R. Chem Rev. 1995;95(2):259–272. doi: 10.1021/cr970037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Appel AM, Bercaw JE, Bocarsly AB, Dobbek H, DuBois DL, Dupuis M, Ferry JG, Fujita E, Hille R, Kenis PJA, Kerfeld CA, Morris RH, Peden CHF, Portis AR, Ragsdale SW, Rauchfuss TB, Reek JNH, Seefeldt LC, Thauer RK, Waldrop GL. Chem Rev. 2013;113(8):6621–6658. doi: 10.1021/cr300463y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dance I. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:9027–9037. doi: 10.1039/c5dt00771b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varley JB, Wang Y, Chan K, Studt F, Nørskov JK. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17(44):29541–29547. doi: 10.1039/c5cp04034e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muckerman JT, Achord P, Creutz C, Polyansky DE, Fujita E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(39):15657–15662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201026109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.