Abstract

Objective To assess the efficacy of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Data sources Medline, Embase, Scientific Citation Index, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, and abstracts from conferences.

Review methods Inclusion criterion was randomised controlled trials comparing topical NSAIDs with placebo or oral NSAIDs in osteoarthritis. Effect size was calculated for pain, function, and stiffness. Rate ratio was calculated for dichotomous data such as clinical response rate and adverse event rate. Number needed to treat to obtain the clinical response was estimated. Quality of trial was assessed, and sensitivity analyses were undertaken.

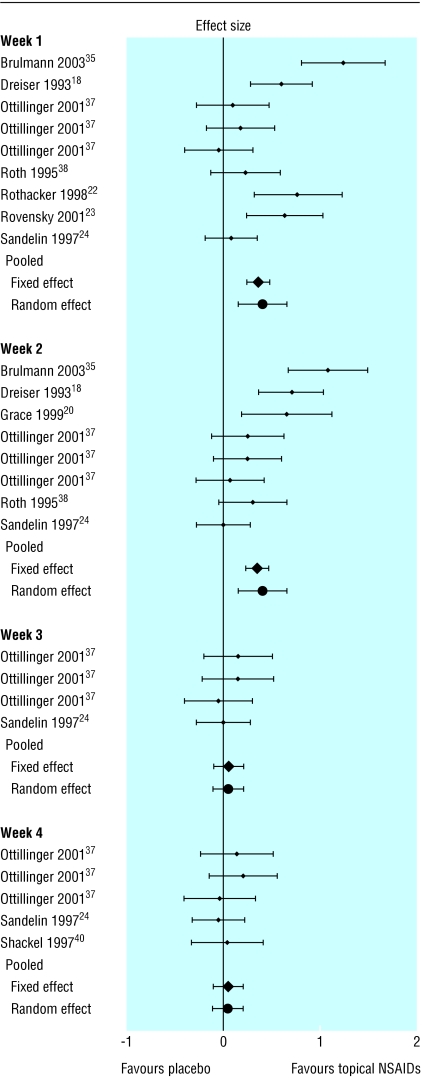

Results Topical NSAIDs were superior to placebo in relieving pain due to osteoarthritis only in the first two weeks of treatment. Effect sizes for weeks 1 and 2 were 0.41 (95% confidence interval, 0.16 to 0.66) and 0.40 (0.15 to 0.65), respectively. No benefit was observed over placebo in weeks 3 and 4. A similar pattern was observed for function, stiffness, and clinical response rate ratio and number needed to treat. Topical NSAIDs were inferior to oral NSAIDs in the first week of treatment and associated with more local side effects such as rash, itch, or burning (rate ratio 5.29, 1.14 to 24.51).

Conclusion Randomised controlled trials of short duration only (less than four weeks) have assessed the efficacy of topical NSAIDs in osteoarthritis. After two weeks there was no evidence of efficacy superior to placebo. No trial data support the long term use of topical NSAIDs in osteoarthritis.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis and the major cause of disability in elderly people.1,2 It represents a major disease burden for patients, health services, and society.3 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used to relieve pain in musculoskeletal tissues, but their use comes at the cost of toxicity, with a 2-4% annual incidence of serious gastrointestinal ulcer and complications—four times higher than in non-users.4-9 NSAIDs have been applied topically for decades. This route possibly reduces gastrointestinal adverse reactions by maximising local delivery and minimising systemic toxicity.10 Some experimental evidence supports this, but at large joints such as the knee, bloodborne delivery may be the predominant mechanism for deep tissues.11 Pain associated with osteoarthritis may be periarticular in origin rather than intracapsular, and topical application may act through effects on peripheral and central sensitisation.12 Irrespective of the mechanism, topical NSAIDs are popular with health professionals and with patients as over the counter medicines. Several randomised controlled trials of short duration (less than four weeks) have been undertaken in both periarticular lesions and osteoarthritis.13-26 A systematic review in 1998 confirmed that topical NSAIDs were superior to placebo over two weeks in the treatment of chronic pain, including pain due to osteoarthritis and tendinitis.27 We did a meta-analysis to determine the benefit of NSAIDs in treating osteoarthritis beyond two weeks.

Methods

We identified reports of randomised controlled trials of topical NSAIDs compared with placebo or oral NSAIDs through a systematic search of the literature from 1966 to 31 October 2003. The MeSH search used in Medline, Embase, and CINAHL consisted of three steps, each containing any possible MeSH relevant to the target condition [osteoarthritis, osteoarthrosis or chronic pain associated with osteoarthritis or osteoarthrosis], study drug [topical NSAIDs], and study method [randomized controlled trial]. All MeSHs were exploded. The steps were then combined to produce relevant citations. We searched the Scientific Citation Index and Cochrane Library with the keywords osteoarthritis and topical NSAIDs. Titles and abstracts were reviewed for possible trials, and hard copies obtained for further scrutiny. The reference lists of original reports and review articles were searched, as were conference abstracts for 2002 and 2003 from international societies of rheumatology, such as the British Society for Rheumatology, the European League Against Rheumatism, the American College of Rheumatology, and the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing topical NSAIDs with placebo or oral NSAIDs. Studies were selected if patients had clinical or radiographical evidence of osteoarthritis. Two rheumatologists (JL and AJ) cross checked and agreed on the diagnostic criteria in each trial. We excluded studies in conditions such as non-osteoarthritic joint pain; rheumatoid arthritis; pain due to dental extraction, surgery, or injury; and studies with mixed patient groups such as those with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, unless the subgroup data for osteoarthritis were available. No language restrictions applied.

Quality assessment

The quality of studies was assessed for randomisation, blinding, and withdrawal. We did not allocate additional scores for description of the method of randomisation as this is a feature of the reporting of the trials and allocation of such points may be arbitrary. Sensitivity analysis was used to assess the impact to the results of the quality components such as study design and withdrawal rate.28

Data extraction and outcome measures

Three of us (JL, WZ, AJ) undertook data extraction independently using a customised form. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

The primary outcome measure was reduction in pain (global pain or pain at rest) from baseline. Other outcome measures included change in function and scores for stiffness. We assessed the clinical response rate, defined as the percentage of patients reporting at least moderate to excellent or greater than 50% pain relief or improvement in symptoms. Adverse events, expressed as the proportion of patients with any adverse events and the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events, were analysed in total and by specific categories (for example, gastrointestinal events).

Statistical analysis

From individual studies we calculated the mean reduction and the standard deviation of the reduction from the means and standard deviations of the scores for pain, function, and stiffness at baseline and end point. The standard mean difference or effect size was then calculated using Hedges unbiased approach.29 The rate ratio was estimated for dichotomous outcomes such as the clinical response rate and adverse event rate.30 We estimated the numbers needed to treat and the 95% confidence intervals.31

We statistically pooled the data by the standard approach, weighted by the inverse of the sampling variance.32 A random effects model was used for heterogeneous trials on the basis of the Q statistics for heterogeneity and if the reason for heterogeneity could not be identified. Possible publication bias was sought by a funnel plot and Egger test.33 Analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software (version 11.0).

Results

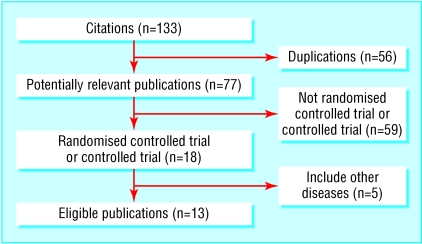

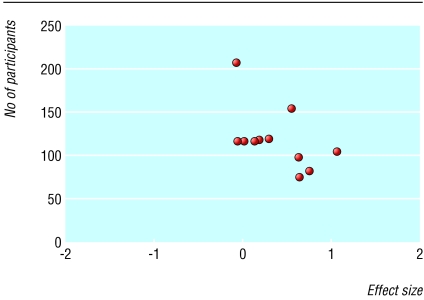

We identified 133 citations, of which 77 remained after omission of duplicate articles. Overall, there were 18 potentially relevant randomised controlled trials (16 in English and two in German). Five were further excluded because either the participants did not exclusively have osteoarthritis or the comparison was between topical NSAIDs and oral NSAIDs compared with oral NSAIDs. Our inclusion criteria were met by 13 trials, representing 1983 patients (fig 1 and table 1). All trials, except for one with unknown sponsorship, were sponsored or partially sponsored with study drugs and placebo by pharmaceutical companies.18 All were stated as randomised controlled trials, but there were no details on method of randomisation. The withdrawal rate was 1% to 23%. A funnel plot showed noticeable asymmetry in the 11 placebo controlled trials (fig 2).

Fig 1.

Selection of randomised controlled trials

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomised controlled trials comparing topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with placebo or oral NSAIDs in patients with osteoarthritis

| Trial | Design | Site of osteoarthritis | Duration (weeks) | Mean (SD) age (years) | No male/No female | % baseline pain score* | Active treatment (No in group) | Control (No in group) | Effect size (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical NSAIDs versus placebo: | |||||||||

| Algozziine 198234 | Double blind crossover | Knee | 1, 1, and 1 | 62 (8) | 24/2 | NA | Salicylate four times daily (26) | Placebo (26) | NA |

| Bruhlmann 200335 | Double blind parallel | Knee | 2 | 64 (11) | 43/60 | 57 | Diclofenac twice daily (51) | Placebo (52) | 1.08 (0.21) |

| Dreiser 199318 | Double blind parallel | Knee | 2 | 66 (11) | 35/120 | 58 | Diclofenac three times daily (78) | Placebo (77) | 0.71 (0.17) |

| Grace 199920 | Double blind parallel | Knee | 2 | 62 (12) | 29/45 | 42 | Diclofenac (38) | Placebo (36) | 0.66 (0.24) |

| Ottillinger 200137 | Double blind parallel | Knee | 4 | 67 (8) | 54/183 | 55 | Eltenac: 3 mg three times daily (59), 9 mg three times daily (59), 30 mg three times daily (57) | Placebo (59), placebo (59), placebo (59) | −0.04 (0.18), 0.20 (0.18), 0.14 (0.19) |

| Roth 199538 | Double blind parallel | Hip, knee, hand | 2 | 67 (NA) | 33/86 | 80 | Diclofenac four times daily (59) | Placebo (60) | 0.31 (0.18) |

| Rothacker 199439 | Double blind crossover | Hand | 3 hours, 1 week, and 3 hours | 66 (8) | 8/41 | NA | Salicylate (50) | Placebo (50) | NA |

| Rothacker 199822 | Double blind parallel | Hand | 2 hours | 61 (11) | 21/60 | 85 | Salicylate twice daily (41) | Placebo (40) | 0.77 (0.23) |

| Rovensky 200123 | Double blind parallel | Knee | 1 | 63 (8) | 26/74 | 32 | Ibuprofen three times daily (50) | Placebo (50) | 0.64 (0.20) |

| Topical NSAIDs versus oral NSAIDs or placebo: | |||||||||

| Shackel 199740 | Double blind parallel | Hip, knee | 4 | 61 (12) | 52/64 | 33 | Salicylate twice daily (58) | Placebo (58) | 0.03 (0.19) |

| Sandelin 199724 | Double blind parallel | Knee | 4 | 61 (8) | 104/177 | 38 | Eltenac three times daily (126) | Placebo (82) | −0.05 (0.14) |

| Eltenac three times daily (126) | Diclofenac twice daily (82) | −0.10 (0.14) | |||||||

| Topical NSAIDs versus oral NSAIDs: | |||||||||

| Dickson 199136 | Double blind parallel | Knee | 4 | 62 (12) | 80/155 | 63 | Piroxicam three times daily (117) | Ibuprofen three times daily (118) | NA |

| Zacher 200126 | Double blind parallel | Hand | 3 | 62 (9) | 38/283 | 50 | Diclofenac (165) | Ibuprofen three times daily (156) | −0.05 (0.11) |

NA=not available.

Percentage of baseline pain score relative to maximum pain score: 0%=no pain, 50%=moderate pain, 100%=severe pain.

Fig 2.

Funnel plot of randomised controlled trials comparing topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with placebo (asymmetry P=0.04)

Efficacy

Reduction in pain

Topical NSAIDs were superior to placebo in the first two weeks of treatment but not the following two weeks (fig 3 and table 2). Topical NSAIDs were less effective than oral NSAIDs numerically at any week and statistically in the first week (see table 2).

Fig 3.

Effect sizes (95% confidence intervals) in pain relief between topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and placebo

Table 2.

Pooled effect sizes for pain relief and improvements in function and stiffness in randomised controlled trials comparing topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with placebo or oral NSAIDs

| Variable | No of trials | No of patients | Pooled effect size (95% CI) | χ2 for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical NSAIDs versus placebo | ||||

| Pain: | ||||

| Week 1 | 7 | 1000 | 0.41 (0.16 to 0.66)* | 35.49 |

| Week 2 | 6 | 893 | 0.40 (0.15 to 0.65)* | 27.48 |

| Week 3 | 2 | 442 | 0.05 (−0.11 to 0.22) | 1.02 |

| Week 4 | 3 | 558 | 0.04 (−0.11 to 0.19) | 1.68 |

| Function: | ||||

| Week 1 | 4 | 566 | 0.37 (0.20 to 0.53)* | 4.60 |

| Week 2 | 4 | 540 | 0.35 (0.19 to 0.53)* | 6.87 |

| Week 3 | 1 | 208 | 0.10 (−0.18 to 0.38) | — |

| Week 4 | 1 | 208 | 0.26 (−0.02 to 0.54) | — |

| Stiffness: | ||||

| Week 1 | 1 | 74 | 0.64 (0.19 to 1.09)* | — |

| Week 2 | 1 | 81 | 0.33 (−0.13 to 0.79) | — |

| Week 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Week 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Topical NSAIDs versus oral NSAIDs† | ||||

| Pain: | ||||

| Week 1 | 1 | 208 | −0.38 (−0.66 to −0.10) | — |

| Week 2 | 1 | 208 | −0.19 (−0.47 to 0.09) | — |

| Week 3 | 2 | 529 | −0.26 (−0.68 to 0.16) | 5.83 |

| Week 4 | 1 | 208 | −0.10 (−0.37 to 0.18) | — |

| Function: | ||||

| Week 1 | 1 | 208 | −0.32 (−0.60 to −0.04) | — |

| Week 2 | 1 | 208 | −0.24 (−0.52 to 0.04) | — |

| Week 3 | 2 | 529 | −0.11 (−0.28 to 0.06) | 0.71 |

| Week 4 | 1 | 208 | −0.10 (−0.38 to 0.17) | — |

NA=not available.

P≤0.05.

Data not available on stiffness.

Improvements in function and stiffness

The effect size for improvement in function also showed superiority of topical NSAIDs over placebo in the first two weeks but not in weeks 3 and 4 (see table 2). A statistically significant effect size for improvement in stiffness was seen at one week but not at two weeks.

Clinical response rate

The clinical response rate ratio was statistically significant in the first but not fourth week (table 3). No difference was found between topical NSAIDs and oral NSAIDs.

Table 3.

Clinical response rate ratio and numbers needed to treat with 95% confidence intervals

|

Crude rate

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Duration (weeks) | Active | Control | Rate ratio (95% CI) | Number needed to treat (95% CI) |

| Topical NSAIDs versus placebo: | |||||

| Rothecker 199439 | 1 | 12/24 | 6/25 | 2.08 (0.93 to 4.66) | NS |

| Rovensky 200123 | 1 | 43/50 | 27/50 | 1.59 (1.20 to 2.11)* | 3.1 (2.1 to 6.6)* |

| Pooled | 1.64 (1.26 to 2.13)* | 3.3 (2.3 to 6.2)* | |||

| Dreiser 199318 | 2 | 72/78 | 43/74 | 1.59 (1.30 to 1.95)* | 2.9 (2.1 to 4.7)* |

| Shackle 199740 | 4 | 32/58 | 32/56 | 0.97 (0.70 to 1.34) | NS |

| Topical NSAIDs versus oral NSAIDs: | |||||

| Dickson 199136 | 4 | 68/107 | 71/118 | 1.06 (0.86 to 1.30) | NS |

P≤0.05.

Adverse events

Topical NSAIDs had no more side effects than placebo. Compared with oral NSAIDs, fewer patients taking topical NSAIDs had any adverse events, withdrawals due to side effects, and gastrointestinal side effects, but significantly more patients had local side effects such as rash, itch, and burning(table 4).

Table 4.

Pooled rate ratio (95% confidence intervals) of side effects

|

Crude rate

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Active | Control | Rate ratio (95% CI) |

| Topical NSAIDs versus placebo: | |||

| No of patients with adverse events | 108/577 | 85/531 | 1.02 (0.62 to 1.68) |

| No of patients withdrawn due to adverse events | 16/577 | 6/531 | 1.51 (0.63 to 3.66) |

| Gastrointestinal events* | 14/577 | 15/531 | 0.81 (0.43 to 1.56) |

| Central nervous system events† | 14/577 | 14/531 | 0.90 (0.43 to 1.89) |

| Local events‡ | 119/577 | 71/531 | 1.14 (0.51 to 2.55) |

| Others | 22/577 | 19/531 | 0.96 (0.57 to 1.63) |

| Topical NSAIDs versus oral NSAIDs: | |||

| No of patients with adverse events | 101/408 | 89/356 | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.27) |

| No of patients withdrawn owing to adverse events | 18/408 | 24/356 | 0.72 (0.37 to 1.38) |

| Gastrointestinal events* | 36/408 | 44/356 | 0.74 (0.48 to 1.13) |

| Central nervous system events† | 19/243 | 14/200 | 1.08 (0.55 to 2.13) |

| Local events‡ | 18/243 | 2/200 | 5.29 (1.14 to 24.51)§ |

Includes nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea.

Includes dizziness and drowsiness.

Skin reactions such as rash, itch, and burning.

P≤0.05.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses showed that although baseline pain score influenced the statistical inference only, the type of topical NSAID produced significantly different effect sizes. Other factors did not affect the results (table 5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis of effect size (95% confidence interval) for reduction in pain between topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and placebo, according to quality of studies, site of osteoarthritis, and pain scores at baseline

| Variable | Weeks 1 and 2 | Weeks 3 and 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Study design: | ||

| Double blind parallel | 0.39 (0.19 to 0.59)* | 0.08 (−0.04 to 0.19) |

| Double blind crossover | 0.77 (0.32 to 1.22)* | NA |

| Withdrawal rate: | ||

| <10% | 0.54 (0.27 to 0.82)* | −0.02 (−0.22 to 0.17) |

| ≥10% | 0.20 (0.06 to 0.34)* | 0.12 (−0.01 to 0.26) |

| Site of osteoarthritis: | ||

| Hand | 0.77 (0.32 to 1.22)* | NA |

| Knee | 0.41 (0.18 to 0.63)* | 0.08 (−0.04 to 0.20) |

| Hand, hip, and knee | 0.27 (0.02 to 0.53)* | 0.03 (−0.34 to 0.39) |

| Baseline pain score: | ||

| <50% | 0.32 (−0.06 to 0.70) | −0.01 (−0.18 to 0.16) |

| ≥50% | 0.44 (0.21 to 0.67)* | 0.14 (−0.01 to 0.92) |

| Topical NSAIDs: | ||

| Salicylate | 0.77 (0.32 to 1.22)* | 0.03 (−0.34 to 0.39) |

| Diclofenac | 0.68 (0.38 to 0.99)* | NA |

| Eltenac | 0.10 (−0.01 to 0.22) | 0.08 (−0.04 to 0.19) |

| Ibuprofen | 0.64 (0.23 to 1.04)* | NA |

NA=not available.

P≤0.05.

Discussion

Most randomised controlled trials of treatment for osteoarthritis last only two weeks, and no trials go beyond four weeks. Meta-analysis of this limited data shows that treatment of osteoarthritis with topical NSAIDs is only beneficial in the first two weeks and at one month is comparable to placebo. Our meta-analysis challenges current guidelines from Europe and America that topical NSAIDs are an effective treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee.41-44

This is only the second meta-analysis of topical NSAIDs. The first analysis, in 1998, reported that topical NSAIDs were effective for “chronic” painful conditions, including osteoarthritis, on the basis of data on pain relief at two weeks.27 Unlike that study we focused solely on osteoarthritis, included studies published in the interim, examined outcomes of stiffness and function as well as pain, and examined data beyond two weeks of treatment. Our analysis had reasonable power since we identified 13 randomised controlled trials that specifically examined osteoarthritis. Although a positive effect superior to placebo was found at two weeks, trials lasting four weeks showed no benefit. The effect of topical NSAIDs may depend on time or more likely reflect the type of drug used (salicylic acid, eltenac, diclofenac, or ibuprofen), as detected by our sensitivity analyses. This seems to be more problematic in the first two weeks, as a statistically significant heterogeneity and different effects of topical NSAIDs were detected. We obtained a statistically significant asymmetrical funnel plot, indicating that negative studies are less likely to be published and that small studies are more likely to produce larger effect sizes. This publication bias may overestimate the benefit of topical NSAIDs.33 We therefore draw two important conclusions from the data: firstly, that further well designed, long term studies (months rather than weeks) are required, and, secondly, that the benefit may be drug specific rather than class specific.

Only three trials compared topical NSAIDs with oral NSAIDs. Comparative efficacy data are limited by trial size and lack of comparison between the same drug given by different routes. The ongoing study of ibuprofen (topical versus oral) funded by the Health Technology Assessment in the United Kingdom should be helpful in this respect.

Several caveats need to be mentioned. Firstly, language bias cannot be completely avoided because many studies in non-English are not indexed in the databases.45 Secondly, results may have been confounded by different numbers of trials being pooled at different time points. Finally, we pooled trials that examined different topical NSAIDs that may have different efficacy. To minimise this bias, we used a sensitivity analysis.

In conclusion, research evidence to support the long term use (more than one month) of topical NSAIDs in osteoarthritis is absent. Current recommendations that support their use in osteoarthritis need to be revised.41-44

What is already known on this topic

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been used to relieve the pain of osteoarthritis

Current guidelines recommend topical NSAIDs as an effective treatment for osteoarthritis

What this study adds

No evidence supports the long term use of topical NSAIDs in osteoarthritis

Current recommendations for their use in osteoarthritis need to be revised

We thank Katja Schmidt from University of Exeter and Plymouth for her help in translating the German papers. Jinying Lin is a visiting scholar from the People's Hospital of Guangxi Province, People's Republic of China.

Contributors: JL was involved in reading the papers, quality assessment, data extraction, analysis, and writing. WZ was involved in planning, searching, reading the papers, quality assessment, data extraction, analysis, and writing. AJ was involved in reading the papers, quality assessment, data extraction, and editing. MD was involved in planning and editing; he will act as guarantor for the paper.

Funding: UK Arthritis Research Campaign (grant Nos D0565 and D0593).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Felson DT. Epidemiology of hip and knee osteoartritis. Epidemiol Rev 1988;10: 1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60: 91-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yelin E. The earnings, income, and assets of persons aged 51-61 with and without musculoskeletal conditions. J Rheumatol 1997;24: 2024-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wynne HA, Campell M. Pharmacoeconomics of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Pharmacoeconomics 1994;3: 107-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein JL, Silverstein FE, Agrawal NM, Hubbard RC, Kaiser J, Maurath CJ, et al. Reduced risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer complications with celecoxib, a novel COX-2 inhibitor. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95: 1681-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutthann SP, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Raiford DS. Individual nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and other risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation. Epidemiology 1997;8: 18-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, Davies HW, Struthers BJ, Bittman RM, et al. Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1995;123: 241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh G, Rosen Ramey D. NSAID induced gastrointestinal complications: the ARAMIS perspective—1997. Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information System. J Rheumatol 1998;51(suppl): 8-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mamdani M, Rochon PA, Juurlink DN, Kopp A, Anderson GM, Naglie G, et al. Observational study of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in elderly patients given selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ 2002;325: 624-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anon. Trolamine salycylate cream in osteoarthritis of the knee. JAMA 1982;247: 1311-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaile JH, Davis P. Topical NSAIDs for musculoskeletal conditions—a review of the literature. Drugs 1998;56: 783-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doherty M, Jones A. Topical NSAIDs. In: Brandt K, Doherty M, Lohmander S, eds. Osteoarthritis. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003: 291-5.

- 13.Akermark C, Forsskahl B. Topical indomethacin in overuse injuries in athletes: a randomised double-blind study comparing Elimetacin with oral indomethacin and placebo. Int J Sports Med 1990;11: 393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diebschlag W, Nocker W, Bullingham R. A double-blind study of the efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine gel in the treatment of ankle sprain, in comparison to placebo and etofenamate. J Clin Pharmacol 1990;30: 82-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosie GAC, Rapier C. The topical NSAID, felbinac, versus oral ibuprofen: a comparison of efficacy in the treatment of acute lower back injury. Br J Clin Res 1993;4: 5-17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison W. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy trial to compare the use of topical Traxam gel with oral ibuprofen in the treatment of acute neck sprain. Clinical trial report. Wayne, NJ: Lederle Laboratories, 1993.

- 17.Vanderstraeten G, Schuermans P. Study on the effect of etofenamate 10% cream in comparison with an oral NSAID in strains and sprains due to sports injuries. Acta Belgica-Medica Physica 1990;13: 139-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dreiser RL, Tisne-Camus M. DHEP plasters as a topical treatment of knee osteoarthritis—a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Drugs Exp Clin Res 1993;19: 117-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eberhardt R ZTHR. [DMSO in patients with active gonarthrosis. A double-blind placebo controlled phase III study]. [German]. Fortschr Med 1995;113: 446-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grace D, Rogers J, Skeith K, Anderson K. Topical diclofenac versus placebo: a double blind, randomized clinical trial in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol 1999;26: 2659-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenen NJ, Haag RF, Bias P, Rose P. Percutaneous therapy of activated osteoarthritis of the knee—comparison between DMSO and diclofenac. Munch Med Wochenschr 1996;138: 534-8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothacker DQ, Lee I, Littlejohn III TW. Effectiveness of a single topical application of 10% trolamine salicylate cream in the symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 1998;4: 6-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovensky J, Micekova D, Gubzova Z, Fimmers R, Lenhard G, Vogtle-Junkert U, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with a topical non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the efficacy and safety of a 5% ibuprofen cream. Drugs Exp Clin Res 2001;27: 209-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandelin J, Harilainen A, Crone H, Hamberg P, Forsskahl B, Tamelander G. Local NSAID gel (eltenac) in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. A double blind study comparing eltenac with oral diclofenac and placebo gel. Scand J Rheumatol 1997;26: 287-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waikakul S, Penkitti P, Soparat K, Boonsanong W. Topical analgesics for knee arthrosis: a parallel study of ketoprofen gel and diclofenac emulgel. J Med Assoc Thailand 1997;80: 593-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zacher J, Burger KJ, Farber L, Grave M, Abberger H, Bertsch K. Topical diclofenac versus oral ibuprofen: a double blind, randomized clinical trial to demonstrate efficacy and tolerability in patients with activated osteoarthritis of the finger joints (Heberden and/or Bouchard arthritis). Aktuel Rheumatol 2001;26: 7-14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore RA, Tramer MR, Carroll D, Wiffen PJ, McQuay HJ. Quantitative systematic review of topical applied non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ 1998;316: 333-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Wan Po A, Zhang W. Systematic overview of co-proxamol to assess analgesic effects of addition of dextropropoxyphene to paracetamol. BMJ 1997;315: 1565-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedges LV. Fitting continues models to effect size data. J Edu Stat 1982;7: 245-70. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothman KJ. Modern epidemiology. Boston: Little, Brown, 1986: 177-233.

- 31.Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 1995;320: 452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitehead A, Whitehead J. A general parametric approach to the meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Stat Med 1991;10: 1665-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egger M, Smith JD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ 1997;315: 629-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Algozzine GJ, Pharm D, Gerald H, Doering PL, Araujo OE, Akin KC. Trolamine salicylate cream in osteoarthritis of the knee. JAMA 1982;247: 1311-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruhlmann P, Michel BA. Topical diclofenac patch in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003;21: 193-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dickson D J. A double-blind evaluation of topical piroxicam gel with oral ibuprofen in osteoarthritis of the knee. Curr Ther Res 1991;49: 199-207. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ottillinger B, Gomor B, Michel BA, Pavelka K, Beck W, Elsasser U. Efficacy and safety of eltenac gel in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2001;9: 272-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth SH. A controlled clinical investigation of 3% diclofenac/2.5% sodium hyaluronate topical gel in the treatment of uncontrolled pain in chronic oral NSAID users with osteoarthritis. Int J Tiss React 1995;17: 129-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothacher D, Difigilo C, Lee I. A clinical trial of topical 10% trolamine salicylate in osteoarthritis. Curr Ther Res 1994;55: 584-97. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shackel NA, Day RO, Kellet B, Books PM. Copper-salicylate gel for pain relief in osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Med J Aust 1997;167: 134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker-Bone K, Javaid K, Arden N, Cooper C. Medical management of osteoarthritis. BMJ 2000;321: 936-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott DL. Guidelines for the diagnosis, investigation and management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Report of the Joint Working Group of the British Society for Rheumatology and the Research Unit of the Royal College of Physician. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1993;27: 391-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma JW, Dieppe P, et al. EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62: 1145-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43: 1905-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egger M, Zellweger-Zahner T, Schneider M, Junker, Lengeler C, Antes G. Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet 1997;350: 326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]