Abstract

The change of locomotion activity in response to external cues is a considerable achievement of animals and is required for escape responses, foraging, and other complex behaviors. Little is known about the molecular regulators of such an adaptive locomotion. The conserved eukaryotic two-pore domain potassium (K2P) channels have been recognized as regulatory K+ channels that modify the membrane potential of cells, thereby affecting, e.g., rhythmic muscle activity. By using the Caenorhabditis elegans system combined with cell-type-specific approaches and locomotion in-depth analyses, here, we found that the loss of K2P channel TWK-7 increases the locomotor activity of worms during swimming and crawling in a coordinated mode. Moreover, loss of TWK-7 function results in a hyperactive state that (although less pronounced) resembles the fast, persistent, and directed forward locomotion behavior of stimulated C. elegans. TWK-7 is expressed in several head neurons as well as in cholinergic excitatory and GABAergic inhibitory motor neurons. Remarkably, the abundance of TWK-7 in excitatory B-type and inhibitory D-type motor neurons affected five central aspects of adaptive locomotion behavior: velocity/frequency, wavelength/amplitude, direction, duration, and straightness. Hence, we suggest that TWK-7 activity might represent a means to modulate a complex locomotion behavior at the level of certain types of motor neurons.

LOCOMOTION is a fundamental aspect of life, because it is required for escape responses, foraging, and other behaviors. In both invertebrates and vertebrates, rhythmic and patterned locomotion is usually controlled by specific motor circuits with autonomous rhythmic activities called central pattern generators (Marder and Calabrese 1996). The overall output of the motor network depends on the interplay of premotor interneurons, motor neurons, muscle cells, and the intrinsic membrane properties of the involved cells. For example, in insects, motor activity appears to increase during walking by tonic depolarization of interneurons and/or motor neurons (Ludwar et al. 2005). In response to environmental cues, animals often adjust their locomotion activity, which, in principle, can be regulated at the level of central pattern generators, interneurons, motor neurons, or muscle cells.

Two-pore domain potassium (K2P) channels are evolutionarily conserved eukaryotic membrane proteins (Enyedi and Czirjak 2010). They contain two pore domains per subunit and function as dimers building one conductance pore. K2P channels operate as regulatory K+ channels to stabilize the negative membrane potential and to counterbalance membrane depolarization. Closure of their potassium pore usually induces membrane depolarization and facilitates the excitability of cells. K2P channels are specifically regulated by a variety of factors, including temperature, pH, membrane stretch, fatty acids, and signaling-pathway-dependent phosphorylation. The physiological function of most K2P channels remains to be elucidated. They have been implicated in the regulation of several processes, such as chemoreception, mechanical nociception, and excitation of motor neurons. Experiments on slice preparations of anesthetized adult turtles revealed that the neurotransmitter serotonin increases the excitability of spinal motor neurons via inhibition of a K2P-like K+ current (Perrier et al. 2003), for example.

In nature, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is mainly found on rotten fruits and vegetables (Felix and Braendle 2010; Petersen et al. 2015). These habitats are characterized by solid and liquid microniches, suggesting that crawling and swimming are natural locomotory modes of the nematode. In the laboratory, the kinematic and biophysical parameters (e.g., mechanic forces) of C. elegans crawling and swimming have been described in detail (Pierce-Shimomura et al. 2008; Fang-Yen et al. 2010; Boyle et al. 2012; Majmudar et al. 2012). The frequency of spontaneous alternating C-shape conformations (swimming) is considerably higher compared to undulating S-shape conformations (crawling). Locomotion is controlled by excitatory cholinergic (A and B type) and inhibitory GABAergic (D type) motor neurons that are localized in the ventral nerve cord of the worm. B-type motor neurons are responsible for forward and A-type motor neurons for backward locomotion (Chalfie et al. 1985). A-, B- and D-type motor neurons are further divided into ventral (V) and dorsal (D) subclasses that innervate the longitudinally aligned ventral and dorsal muscle cells, respectively (White et al. 1976; Wen et al. 2012; Gjorgjieva 2014). A- and B-type motor neurons synapse not only onto their respective muscle cells but also onto corresponding inhibitory D-type motor neurons (VD or DD), leading to contralateral muscle inhibition (White et al. 1976; Wen et al. 2012; Gjorgjieva 2014). Recently, it has been shown that the B-type motor neurons (responsible for forward locomotion) are coupled by proprioception, thereby transducing the rhythmic movement, which may be initiated by a postulated central pattern generator near the head, into bending waves propagated driven along the body by a chain of reflexes (Wen et al. 2012). Moreover, studies by Kawano et al. (2011) revealed that an imbalanced neuronal activity between B-type and A-type motor neurons is responsible for directional movement. In response to mechanical, gustatory, olfactory, and thermal stimuli or food deprivation (Sawin et al. 2000; Shtonda and Avery 2006; Clark et al. 2007; Luo et al. 2008; Ben Arous et al. 2009; Luersen et al. 2014), C. elegans shows adaptive locomotion behaviors. The stimulated backing escape response has been characterized in detail (Chalfie et al. 1985; Donnelly et al. 2013). However, the underlying mechanisms (channels, subgroup of neurons, etc.) that are involved in distinct adaptive changes of forward locomotion behavior remain largely unknown.

C. elegans K2P channels are designated as TWK channels [two P (pore forming) domain K+ channels]. More than 40 TWK-encoding genes representing six subfamilies have been identified in the worm (Salkoff et al. 2001; Buckingham et al. 2005). In Drosophila and mammals, only 11 and 15 K2P channels have been annotated, respectively. Most C. elegans TWK channels are expressed in a few cell types, including body-wall muscle cells, chemosensory neurons, interneurons, and motor neurons (Salkoff et al. 2001; Kratsios et al. 2012). Up to now, only two TWK channels, both expressed in body-wall muscle, have been functionally characterized in C. elegans (Kunkel et al. 2000; de la Cruz et al. 2003, 2014). TWK-18 has been implicated in locomotion activity in response to higher temperature. TWK-23 (SUP-9) is activated by a putative iodotyrosine deiodinase (SUP-18) and might be involved in the excitability of muscle membranes. Overall, our knowledge regarding the physiological functions of two-pore domain potassium channels, even in C. elegans and also in other experimental systems, such as fly, zebrafish, or mouse, is rather limited. Here, we found that TWK-7 is required in cholinergic B-type and GABAergic D-type motor neurons to maintain normal spontaneous locomotor activity and locomotion behavior. The coordinated hyperactive phenotype with fast forward and directed crawling caused by loss of TWK-7 function is consistent with the abovementioned impact of closure or inactivation of regulatory K2P channels on the membrane potential of cells and the effect of hyperexcitability of motor neurons on C. elegans locomotion. Owing to the regulatory nature of K2P channels, we suggest that TWK-7 may represent a prime candidate for the modulation of adaptive locomotion behavior that enables fast and directed forward locomotion.

Materials and Methods

Strains and culturing

All C. elegans strains were grown at 20° on nematode growth media (NGM) agar plates seeded with OP50 Escherichia coli as a food source (Brenner 1974). The following strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center: Bristol N2 (used as wild type), RB1239 twk-30(ok1304)I (1000-bp deletion), twk-40(tm6834)III (473-bp deletion), VC40352 twk-43(gk590127)V (substitution L232Ochre), VC40313 twk-46(gk568572)V (substitution G125E), otEx4803 (expressing DsRed under a 3000-bp twk-7 promoter) (Kratsios et al. 2012), LY120 twk-7(nf120)III, VC40681 twk-7(gk760044)III, and RB1239 twk-30(ok1304)I. The strain MT1908 nDf21/dpy-19(e1259), unc-32(e189)III was used for genetic complementation studies. The strain used for cell-specific expression pattern analyses was LX929 unc-17p::GFP(vsIs48). For colocalization studies, we used the thermosensitive strain GE24 pha-1(e2123)III transformed with the plasmid of interest and the rescuing plasmid pBX as comarker (Granato et al. 1994). Double mutants were generated using standard genetic methods without additional marker mutations. Homozygosity of alleles in each double mutant was confirmed by PCR in the case of deletion mutations, by restriction length polymorphism analysis in the case of appropriate SNP mutations, or in all other cases by sequencing of amplified genomic DNA.

Molecular biology and transfection of C. elegans

Transgenic strains were generated by biolistic bombardment following the protocol of Wilm et al. (1999). For rescue experiments, the myo-2p::GFP::pPD118.33 plasmid was used as comarker. Oligonucleotides used for amplification of the following constructs are listed in Supplemental Material, Table S1.

Genetic constructs

twk-7p::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR):

This rescue construct was generated by cloning a 12.1-kb genomic sequence including 3.0 kb upstream of the translational start site into the pPD118.33DD-mCherry vector.

twk-7p::TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR) and twk-7p::TWK-7(T279K)::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR):

A 3.5-kb fragment was cut off of the twk-7p::TWK-7::mCherry construct by using PstI. After gel purification, the isolated fragment was further digested by BglII resulting in a 2.4-kb product of interest for subcloning into the vector pL4440. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out by employing this construct and the complementary primer pairs corresponding to the sequences 5′-AACCGTCGTCACTACCATCGGAT ACGGTAATCCAGTTCCAG-3′ (underlined nucleotide sequence was changed to TGT) and 5′-CTTTGCCGTAACCGTC GTCACTACCATCGGATACGGTAATC-3′ (underlined triplet was changed to AAG) in order to obtain a G282C and T279K exchange in the TWK-7 protein sequence, respectively. The mutated fragments were verified by sequencing, before cloning back into the twk-7p::TWK-7::mCherry construct via SwaI and BglII.

unc-17p(4.2 kb)::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR), unc-17(1 kb)p::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR), and unc-17(1 kb)p::TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR):

The unc-17p(4.2 kb) construct was generated by cloning the cholinergic neuron-specific 4.2-kb promoter region of unc-17 (restriction sites used: ApaI and NdeI) in front of the twk-7 gene of 9142 bp (starting with translational start site) that is fused to mCherry reporter in the pBluescript vector. In addition, we replaced the 4.2-kb unc-17 promoter sequence by a 1-kb unc-17 promoter fragment that has been shown to drive gene expression solely in cholinergic motor neurons (Kratsios et al. 2012). For the dominant-negative TWK-7 construct, a 2.4-kb fragment containing the G282C exchange was excised from twk-7p::TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry vector by BglII and SacII and introduced into the unc-17(1 kb)p::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR) construct.

unc-4p::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR), unc-4p::TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR), acr-5p::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR), acr-5p::TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR), unc47p::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR), and unc-47p::TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR):

These constructs were produced by ligation of the cholinergic neuron-specific promoter regions of unc-4 (4.2-kb genomic DNA, restriction sites: ApaI and NdeI) and acr-5 (4.3-kb genomic DNA, restriction sites: ApaI and AseI) and the GABAergic neuron-specific promoter region of unc-47 (2.9-kb genomic DNA, restriction sites: ApaI and NdeI) in front of the 9142-bp twk-7 and twk-7(G282C) genes, respectively (starting with translational start site) that are fused to mCherry reporter in the pBluescript vector.

Short-term locomotion assays and analyses

To quantify the number of body bends of swimming worms, five nematodes were transferred with a worm picker (platinum wire) from standard NGM plates onto empty NGM plates to clean worms from bacteria. After ∼1 min, worms were placed in a 50-µl droplet of M9 buffer onto a diagnostic slide (three wells, 10-mm diameter) (Menzel). The worms were immediately filmed for 1 min with a VRmgic C-9+/BW PRO IR-CUT camera (VRmagic, Mannhein, Germany) attached to a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). MOV files were used to quantify the body bending swimming frequency by ImageJ wrMTrck wormtracker plugin according to the protocol described in http://www.phage.dk/plugins/download/wrMTrck.pdf. One body bend corresponds to the movement of the head region thrashing from one side to the other and back to the starting position. For the locomotion analysis on NGM agar plates, we followed the protocol of Miller et al. (1999) with minor modifications. The assay was set up by placing 500 late L3 or early L4 stage larva on locomotion assay plates spread with a thin lawn of OP50 bacteria (100 µl of an OP50 overnight culture per plate, incubated for 20 hr at 37°). Worm plates were incubated at 20° for 24 hr, before the locomotion of young adult animals was filmed three times for 1 min with the camera setup described above. Spontaneous body bending crawling frequency was assessed by visual inspection of worms that were captured for at least 5 sec. One body bend corresponds to the movement of the tip of the tail from one side to the other. Velocity and straightness were analyzed by using ImageJ wrMTrck wormtracker plugin. The forward locomotion efficiency (straightness) was calculated from the ratio of distance to track length, whereby the distance represents the straight line from start to end coordinates of each recorded animal. In addition, for more detailed analyses, we split the locomotion behavior into forward, backward, and dwelling time periods. The latter includes periods where worms move less than one body bend in forward or backward direction. Body bending crawling frequencies of single worms were separately assessed for forward locomotion periods. Furthermore, we determined the relative time the worms spent on dwelling and forward and backward locomotion.

Stimulated forward locomotion assays (picking transfer assays) were done as described in Gaglia and Kenyon (2009). Staged young adult animals were transferred with a worm picker from standard NGM plates to NGM assay plates spread with a thin lawn of OP50 food bacteria. Movies were taken immediately after transfer and every 30 min for 2 hr. Body bending crawling frequencies were assessed by visual inspection of the movies. Speed and forward locomotion efficiency were analyzed by using ImageJ wrMTrck wormtracker plugin.

For all locomotion assays, mutants and transgenic strains were strictly compared with the respective control strains (wild-type, nontransgenic siblings) on the same day using the same batch of plates.

Long-term tracking assay and analysis

NGM plates were seeded with E. coli OP50 and incubated over night at 37°. In order to determine the long-term locomotion behavior, single well fed young adult animals were transferred into a 10-µl M9 drop on the freshly seeded NGM plates and incubated for 16 hr at 20°. For track assessment, worm traces were visualized on the backside of each NGM plate using a pencil marker and then captured as .jpeg files with a VRmgic C-9+/BW PRO IR-CUT camera (VRmagic) attached to a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C microscope (Carl Zeiss). Recorded tracks were finally ranked by visual inspection, counting the squares crossed by each worm.

Body curvature analyses

Single swimming or crawling worms were filmed for 10 sec. Subsequently, their bodies were skeletonized and the resulting spines were divided into 10 segments by using MultiWormTracker (version 1.3.0-r1035) software (Swierczek et al. 2011). The alteration of angles between adjacent segment pairs was calculated over time. Resulting values were transferred to MatLab and processed using the contour plot function.

Imaging of reporter strains

Transgenic animals were anesthetized and mounted in 5 mM of levamisole and 5 mM of aldicarb on a 2% agarose pad. Laser-scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy was carried out using a Zeiss Axio Imager Z2 upright microscope equipped with a Zeiss LSM 700 scanning confocal imaging system. Image acquisition and processing was performed by employing Zeiss ZEN software.

Calculation of the slip values for locomotion efficiency

Locomotion efficiency was introduced as the amount of slip (S) by Gray and Lissmann (1964) for the locomotion of nematodes. Slip values were calculated from the ratios between velocity (Vλ) of the undulating wave propagated over the worm spine and the velocities (Vx) of the moving worm, where f represents the bending frequency and λ the wave length:

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.

Results

TWK-7 deficiency led to an enhanced activity of both swimming and spontaneous crawling in a coordinated mode

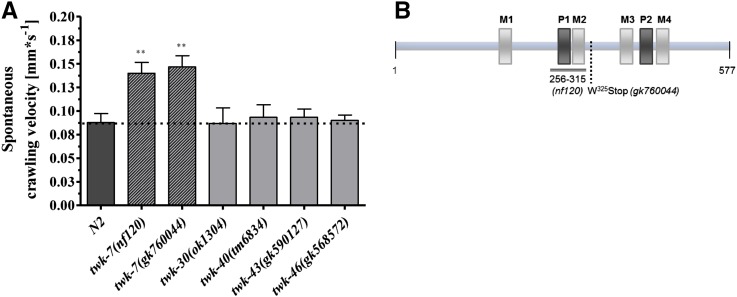

The C. elegans genome contains more than 40 genes encoding TWK channels. Of these, TWK-7, -30, -40, -43, and -46 have been previously shown to be expressed in motor neurons (Salkoff et al. 2001; Kratsios et al. 2012). Because the evolutionarily conserved K2P/TWK channels are known to set the membrane potential and hence influence the excitability of cells, we investigated whether these C. elegans channels have a physiological role in locomotion. When tested for their locomotor activity, the twk-7 mutant allele nf120 showed an altered spontaneous crawling activity from wild-type worms, whereas mutant alleles of other TWK channels expressed in motor neurons did not induce a similar phenotype (Figure 1A). Consistent with the general structure of K2P channels, in silico analyses predicted that the deduced TWK-7 protein contains four transmembrane domains (M1–M4) and the two pore domains P1 and P2 that specify ion selectivity (Figure 1B and Figure S1). In the nf120 allele the twk-7 gene contains a deletion of 303 bp, which leads to the disruption of the P1 and M2 domains and a translational frameshift within the open reading frame.

Figure 1.

twk-7 mutant alleles exhibit enhanced spontaneous crawling activity. (A) Small-scale locomotion screen revealed that twk-7(nf120) and twk-7(gk760044) animals exhibited notably enhanced velocities during spontaneous crawling when compared with wild-type and mutant strains of other TWK-family members that are known to be expressed in motor neurons. The dotted line indicates the wild-type level. Values represent the means (± SEM) of N ≥ 3 independent experiments involving n ≥ 40 animals. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). (B) Schematic diagram of the TWK-7 protein indicates the predicted position of the pore domains P1 and P2 (dark gray) and the transmembrane domains M1–M4 (light gray). The polypeptide region that is not encoded by the deletion mutant allele nf120 and the localization of the premature stop of the allele gk760044 are depicted.

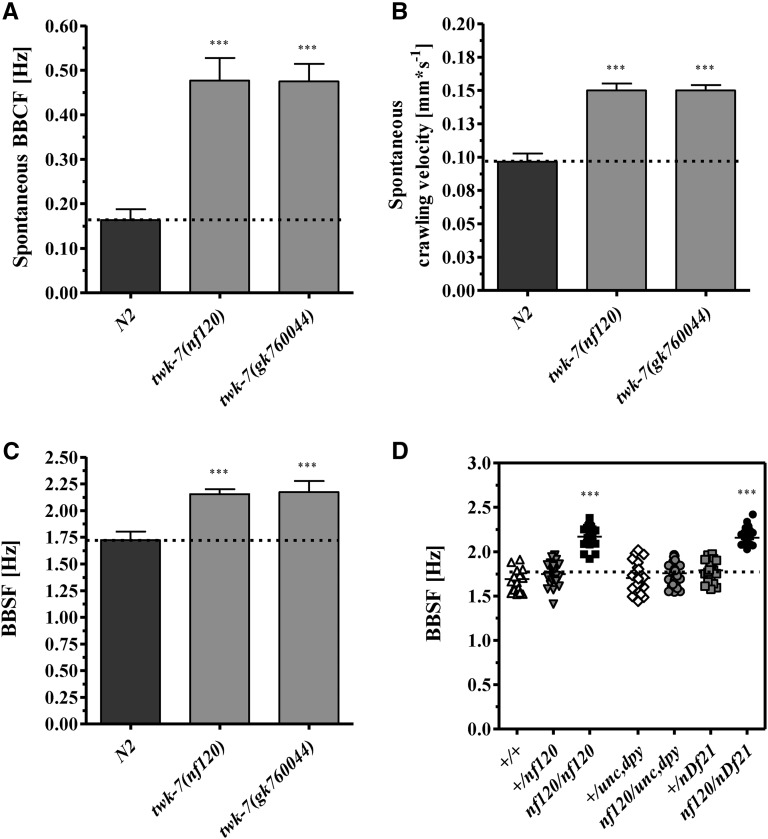

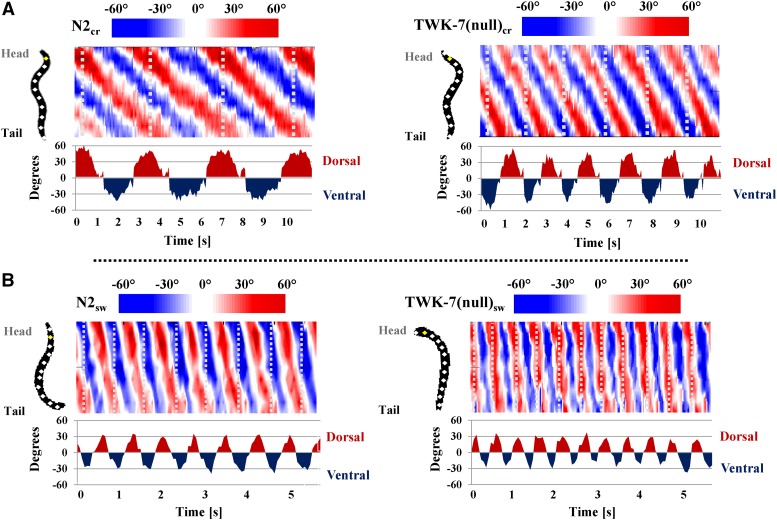

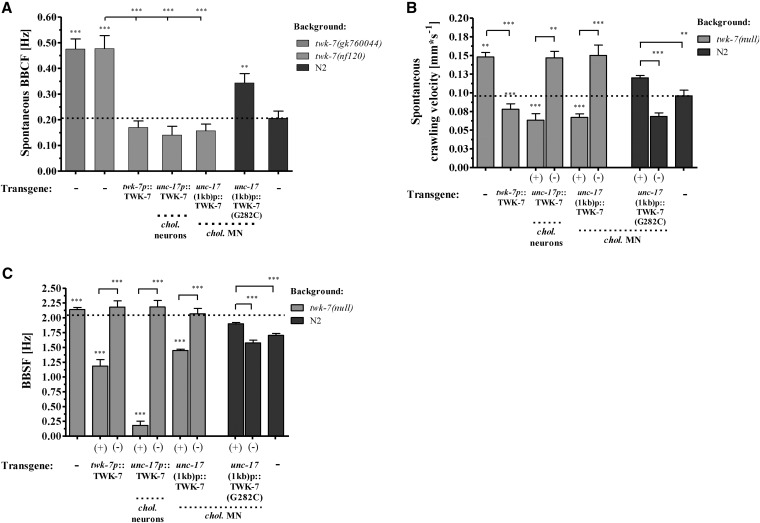

On agar plates, the twk-7(nf120) worms moved with an elevated spontaneous crawling body bending frequency of 0.48 ± 0.11 Hz (wild type: 0.16 ± 0.05 Hz) resulting in an increased crawling velocity of 0.15 ± 0.01 mm/s−1 (wild type: 0.10 ± 0.02 mm/s−1) (Figure 2, A and B, File S1, and File S2). Of note, the threefold increase in body bending frequency of twk-7(nf120) worms led only to a 1.5-fold enhanced crawling velocity when compared to wild-type data. The twk-7(nf120) mutant worms also exhibited an enhanced swimming activity of 2.16 ± 0.05 Hz when compared to wild-type animals with a body bending swimming frequency of 1.68 ± 0.09 Hz (Figure 2C, File S3, and File S4). We conclude that among the K2P mutants tested, only TWK-7 function is required to maintain spontaneous locomotor activity of C. elegans. Hence, for further analysis, we focused on TWK-7. Genetic analysis revealed that nf120 is a recessive null allele of twk-7 (Figure 2D). Thus, twk-7(nf120) was specified as twk-7(null). Accordingly, similar higher crawling and swimming activities were determined for a second loss-of-function allele of twk-7, gk760044 that is characterized by a premature stop at position W325 (Figure 1, A and B, Figure 2, A–C, and Figure S1). Importantly, although the two twk-7 mutants swam and crawled with higher frequencies than wild types, they maintained both normal C-shape conformations during swimming and normal undulating S-shape conformations during crawling (Figure 3, A and B). These results suggest that loss of TWK-7, which most probably mimics a closure of the K+ channel, affects swimming and crawling in a coordinated manner.

Figure 2.

The hyperactive allele nf120 is a recessive null allele of twk-7. (A) The spontaneous body bending crawling frequencies (BBCFs) and (B) the corresponding spontaneous crawling velocities of twk-7 mutant alleles. (C) The body bending swimming frequencies (BBSFs) of the twk-7 mutant alleles. (D) Genetic complementation analyses revealed that only worms homozygote for the twk-7 deletion allele (nf120/nf120) exhibited increased BBSFs. Heterozygote worms (+/nf120) swam like wild type (+/+). Bringing the nf120 allele in trans to the chromosomal deletion nDf21 of the balanced deficiency mutant nDf21/dpy-19(e1259), unc-32(e189)III resulted in worms (nf120/nDf21) with elevated BBSFs, similar to twk-7(nf120) homozygotes. Symbols represent single worms. Genotypes of the tested worms were determined by PCR and/or phenotype analyses of progeny n ≥ 20 animals. Dotted lines indicate the respective wild-type level. Values represent the means (± SEM) of (A–C) N ≥ 4 and (D) N = 3 independent experiments involving n ≥ 40 animals. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

Figure 3.

twk-7(null) animals swim and crawl in a coordinated manner. (A) The S- and (B) C-shape conformations of crawling and swimming worms were visualized using the curvature matrices. Sequence continuities indicate that twk-7(nf120) worms crawled (A) and swam (B) in a coordinated manner similar to wild types, although with higher body bending frequencies. The color code illustrates the dorsal (D, red) and ventral (V, blue) changes of body shape angles (up to 40° for swimming and 60° for crawling, respectively) over time during locomotion (for details see Materials and Methods). The sinusoidal curves below depict the corresponding rhythmic curvature of the neck (for swimming) and midbody segment (for crawling) over time (segments are marked in yellow).

An age-dependent decline of locomotor activity has been reported for wild-type C. elegans (Schreiber et al. 2010). Both twk-7 loss-of-function mutants also showed a constant decrease of swimming activity over 12 days, starting with L4 larvae (Figure S2). Nevertheless, during the whole aging period, the twk-7 mutants still had higher locomotor activities than age-matched control worms. Thus, TWK-7 function affects locomotor activity throughout C. elegans adulthood, but does not influence the gradual reduction of activity caused by the aging process.

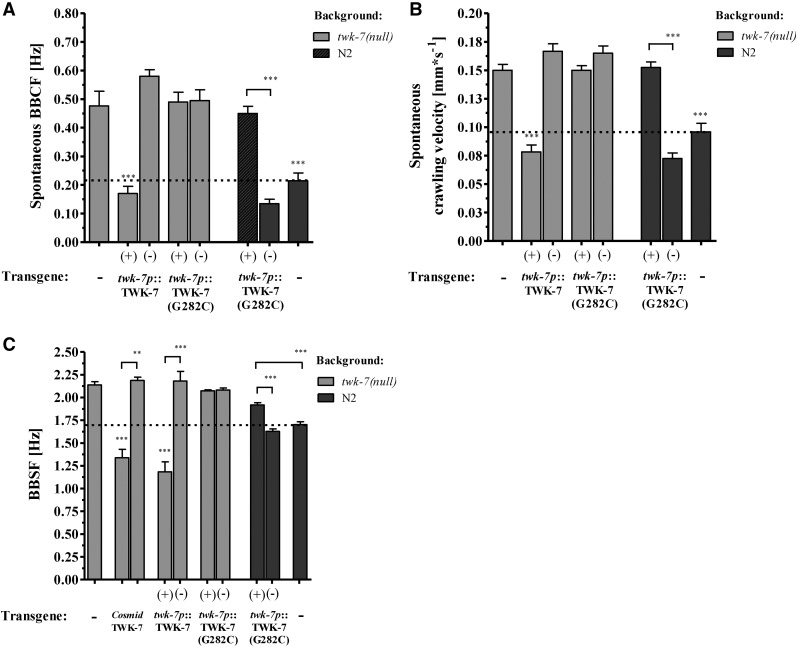

An intact potassium pore is required for the function of TWK-7 in maintaining normal swimming and crawling activity

To further investigate the function of TWK-7 in affecting locomotor activity, the twk-7(nf120) null mutant was transformed either with the twk-7-containing cosmid F22B7 or with the construct cauEx[twk-7p(3000)::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR)] that consists of the full genomic region of twk-7, including 3000 bp of the promoter. Analysis of the resulting transgenic worms showed that these constructs rescued both the accelerated crawling and swimming activity of twk-7(null), even slightly below wild-type level (Figure 4, A–C and File S6). In contrast, the activity of swimming and crawling was not affected in the nontransgenic siblings.

Figure 4.

TWK-7 functions in motor neurons to affect locomotor activity. (A) BBCFs and (B) the respective crawling velocities of transgenics (+) expressing TWK-7 and the selectivity filter mutant TWK-7(G282C) under its own promoter. Values for the corresponding nontransgenic siblings (−) are shown. (C) BBSFs of transgenic twk-7(nf120) and transgenic N2 wild-type worms are depicted. Transgenics (+) are directly compared with nontransgenic (−) siblings. Overexpression of TWK-7 in a twk-7(null) background restores the BBSFs even below wild-type level. In contrast, the selectivity filter mutant TWK-7(G282C) did not affect the swimming rate of twk-7(nf120), but has a dominant-negative effect on the swimming activity in a N2 genetic background.

In a functional K2P channel dimer, the pore domains P1 and P2 of both subunits contribute to the formation of one conductance pore specific for K+ (Enyedi and Czirjak 2010). Single amino acid substitutions within the ion selectivity filter of pore domain P1 inactivates channel function due to suppression of K+ conductance (Kollewe et al. 2009). Here, we introduced the mutations into our twk-7 construct cauEx[twk-7p(3000)::TWK-7::mCherry::let-858(3′ UTR)] to analyze whether the potassium pore of TWK-7 is required for locomotor function. We found that neither mCherry-tagged mutant channel TWK-7(G282C) nor TWK-7(T279K) is able to rescue twk-7(null) locomotion phenotypes (Figure 4, A–C and Figure S3, A and B), which is indicative for a disrupted TWK-7 channel function. Confocal microscopy analysis showed an expression pattern of the TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry mutant channel similar to that of wild-type TWK-7::mCherry (data not shown). Remarkably, expression of TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry in wild-type worms resulted in an elevation of both crawling and swimming activity when compared with nontransgenic siblings or nontransformed wild-type worms (Figure 4, A–C). Because the two-pore domain K+ channels are obligate dimers whose pore domains form a single ion pore, our data indicate a successful expression of a dominant-negative TWK-7 mutant protein that most probably suppresses potassium conductance owing to an impaired ion selectivity filter. We conclude that an intact K+ channel function of TWK-7 is necessary to maintain normal spontaneous locomotor activity.

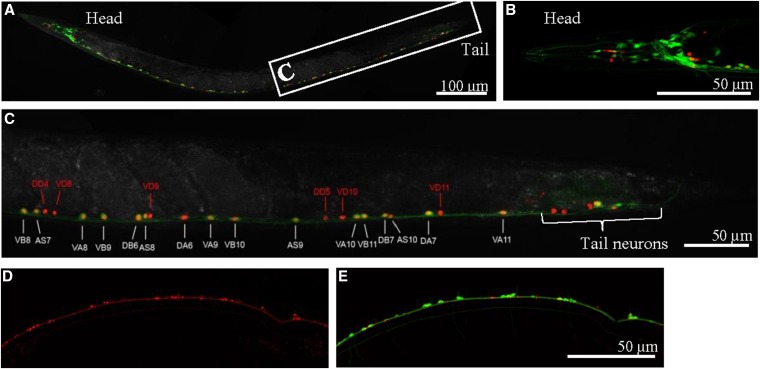

TWK-7 is expressed in all types of motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord

To determine the expression pattern of TWK-7, we employed the ohEx[twk-7p(3000)::DsRed::let-858(3′ UTR)] construct (Kratsios et al. 2012) expressing a cytosolic DsRed reporter protein under the control of the twk-7 promoter. For colocalization studies, we used the vsIs48[unc-17p::GFP::let-858(3′ UTR)] construct that expresses a GFP reporter protein in the entire set of cholinergic neurons with the exception of VC neurons (Kratsios et al. 2012). Confocal microscopy of transgenic worms revealed that the twk-7 promoter drives DsRed reporter expression in some head and tail neurons as well as in all A-, B-, and AS-type motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord (Figure 5, A–C and Figure S4, A–D). In addition, DsRed expression was seen in GFP− neurons. According to their number and stereotypic position, these TWK-7-expressing cells were identified as the 13 ventral and 6 dorsal GABAergic D-type motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord. The cell-type-specific expression pattern of TWK-7 was confirmed in worms that express a C-terminal-tagged TWK-7::mCherry fusion protein under the control of the twk-7 promoter (Figure 5, D and E). TWK-7::mCherry was localized along the ventral nerve cord and in punctated structures in the soma of motor neurons (Figure S4, E–G), suggesting that TWK-7 is trafficked by the secretory Golgi-dependent pathway. Taken together, in accordance with the unraveled impact of TWK-7 on locomotor activity of C. elegans, TWK-7 is expressed in all types of motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord that control body-wall muscle activity.

Figure 5.

TWK-7 is expressed in ventral nerve cord, head, and tail neurons. (A) Cytosolic DsRed expression driven by the twk-7 promoter is overlaid with the cholinergic neuron-specific cytosolic GFP expression mediated by the unc-17 promoter. Coexpression is indicated by yellow color. (B) Maximum projection of a z-series through the head region revealed that DsRed fluorescence is seen in cholinergic and noncholinergic head neurons. (C) Maximum projection of a z-series through the cholinergic region of the ventral nerve cord. Detailed coexpression analyses of TWK-7- and UNC-17-expressing cells in the ventral nerve cord indicate that TWK-7 is present in the cholinergic A-, AS-, and B-type motor neurons as well as in UNC-17− cells. According to their stereotypic positions, these were identified as GABAergic D-type motor neurons. In addition, TWK-7 expression is seen in unidentified tail neurons. (D) Maximum projection of a z-series through the cholinergic region of the ventral nerve cord. Expression of a TWK-7::mCherry fusion protein, which includes the entire TWK-7 channel protein, leads to a punctate subcellular and membrane-associated localization. (E) Coexpression of cytosolic GFP is driven by the cholinergic neuron-specific unc-17 promoter.

TWK-7 is required in excitatory cholinergic motor neurons to maintain normal spontaneous crawling activity

Cholinergic B-type and A-type motor neurons excite muscles on each side of the body during forward and backward crawling, while indirectly inhibiting muscles through excitation of GABAergic D-type motor neurons on the complementary side (Chalfie et al. 1985; Sengupta and Samuel 2009). The B-type neurons act like a single command unit switching local segment oscillations on or off and modulate the speed and amplitude of the local segment waves (Bryden and Cohen 2008). Here we asked whether TWK-7 functions in a certain subset of neurons to maintain normal spontaneous locomotor activity. Expression of TWK-7::mCherry exclusively in cholinergic excitatory motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord reduced both the crawling (Figure 6, A and B) and swimming activity (Figure 6C) of twk-7(null) comparable to the values obtained for transgenic worms expressing twk-7 under its own promoter. Ectopic expression of TWK-7::mCherry in all cholinergic neurons of twk-7(null) resulted in uncoordinated and almost immobile swimming animals (Figure 6C), indicating that a correct spatial expression of TWK-7 is critical for its locomotor function. Complementary to the results of the rescue approach, expression of the dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C)::mCherry mutant channel in cholinergic excitatory motor neurons of wild-type worms led to an increased crawling and swimming activity (Figure 6, A–C). Thus, functional TWK-7 is required in excitatory cholinergic motor neurons (A and B type) to maintain normal spontaneous locomotor activity.

Figure 6.

TWK-7 function in cholinergic motor neurons is sufficient to affect the spontaneous locomotor activity of C. elegans. (A) Crawling and (B) swimming activity analyses of transgenics expressing TWK-7 cell specifically. By employing two different unc-17 promoter constructs, TWK-7 and the dominant-negative selectivity filter mutant channel TWK-7(G282C) were cell-specifically expressed in all cholinergic neurons [unc-17(4.2 kb)p] or solely in the subset of cholinergic motor neurons [unc-17(1 kb)p]. For each transgene (+) the corresponding locomotor activity of nontransgenic sibling (−) is shown. Values represent the means (± SEM) of N ≥ 3 independent experiments involving n ≥ 30 animals. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). Dotted lines indicate the respective wild-type level.

TWK-7 is required in cholinergic B-type motor neurons to maintain normal spontaneous crawling activity

In order to examine the role of TWK-7 in single subtypes of the cholinergic and GABAergic neurons, we expressed the wild-type variant of TWK-7 in the twk-7(null) background, and the dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C) variant in the N2 wild-type background under the control of the unc-4 (cholinergic A-type motor neurons), acr-5 (cholinergic B-type motor neurons) and unc-47 (GABAergic D-type motor neurons) promoter. Expression in A-type motor neurons did not induce any change in the spontaneous forward crawling behavior compared with corresponding nontransgenic animals (Figure 7, A and B). In contrast, worms with twk-7(null) background expressing acr-5p::TWK-7 (B type) or the unc-47p::TWK-7 (D type) construct exhibited markedly decreased locomotion rates (Figure 7, A and B). The spontaneous crawling activities of acr-5p::TWK-7 (0.18 ± 0.05 Hz; 0.08 ± 0.01 mm/s−1) and unc-47p::TWK-7 (0.21 ± 0.01 Hz; 0.09 ± 0.01 mm/s−1) transgenics were similar to those of wild-type animals (0.23 ± 0.02 Hz; 0.09 ± 0.01 mm/s−1), but significantly reduced in comparison with the twk-7(null) mutants (0.46 ± 0.07 Hz; 0.13 ± 0.02 mm/s−1). Consistently, the dominant-negative effect induced by the acr-5p::TWK-7(G282C) in wild-type background led to notably elevated spontaneous locomotion rates (0.47 ± 0.05 Hz; 0.13 ± 0.02 mm/s−1) compared with the N2 control animals (0.23 ± 0.06 Hz; 0.09 ± 0.01 mm/s−1) (Figure 7, A and B). Despite the fact that overexpression of TWK-7 in D-type motor neurons rescued hyperactive phenotype of twk-7(null), dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C) did not accelerate locomotion of wild-type worms when expressed in D-type motor neurons. Thus, functional TWK-7 is required in cholinergic B-type but not in GABAergic D-type motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord to maintain the normal activity of spontaneous crawling.

Figure 7.

Cholinergic B-type and GABAergic D-type motor neuron-specific expression of TWK-7 affects the spontaneous crawling activity of C. elegans. (A) BBCFs and (B) crawling velocity were analyzed in twk-7(null) and wild-type animals overexpressing the wild-type and the dominant-negative G282C mutant form of TWK-7 in A-type, B-type, or D-type motor neurons, respectively. The transgenic worms (+) are directly compared with the nontransgenic (−) siblings. Dotted lines indicate the respective wild-type level. Values represent the means (± SEM) of N ≥ 3 independent experiments involving n ≥ 30 animals. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

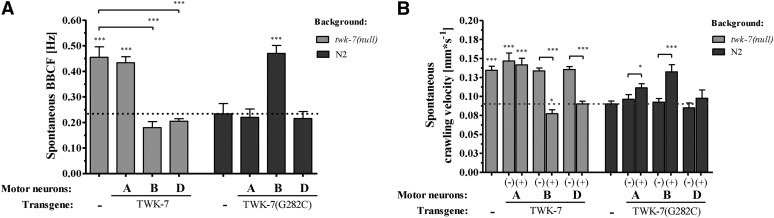

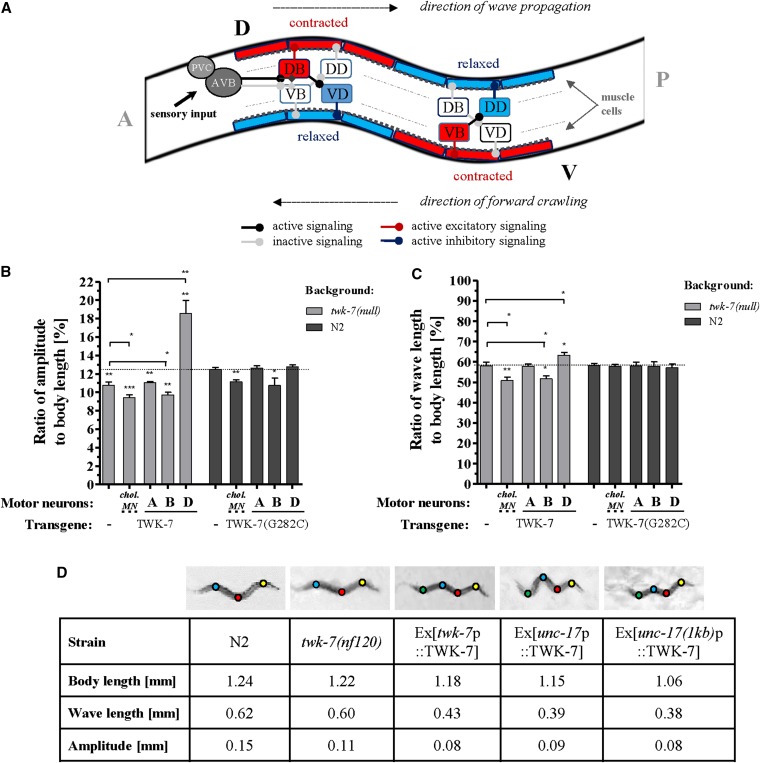

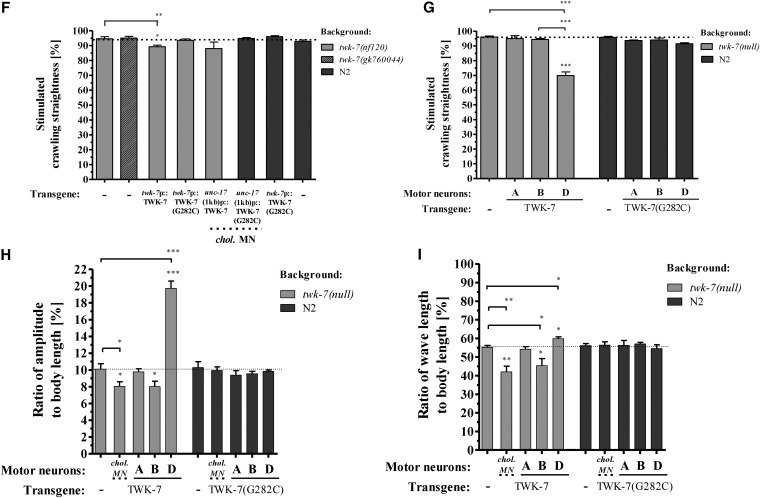

TWK-7 abundance in cholinergic B-type and GABAergic D-type motor neurons affects wave parameters during spontaneous crawling

The crawling pattern of C. elegans and other nematodes is determined by a sinusoidal wave propagated along the body from the head to the tail, where each segment of the worm’s body follows the preceding segment (Gray and Lissmann 1964; Park et al. 2008) (Figure 8A). In this context, we were interested to know to what extent the elevated speed of progression of twk-7(null) worms affects parameters (i.e., amplitudes and wavelengths), which determine the shape of the wave (Figure S6, A and B). To compare worm strains with different body proportions (Figure S6C), we calculated the respective wave parameters in percentage of body lengths. We found that twk-7(null) mutants moved with ∼15% lower amplitude-to-body length ratios than wild types (Figure 8B), whereas the wavelength-to-body length values of both strains were very similar (Figure 8C). Therefore, since the propagation speed of the wave along the body (Figure 8A) is determined by the frequency and the wave length, the higher bending frequency of twk-7(null) animals (Figure 7A) was linearly translated into an increased wave velocity (Figure S6D). Generally, increased wave velocities were associated with a decreased locomotion efficiency, as indicated by the calculated slip values (Figure S6E).

Figure 8.

TWK-7 acts in cholinergic B-type and GABAergic D-type motor neurons to affect the wave parameters during spontaneous crawling. (A) Schematic of muscle control during forward crawling driven by B- and D-type motor neurons is depicted, where A, P, V, and D indicate the anterior, posterior, ventral, and dorsal directions, respectively. Excitatory cholinergic B-type motor neurons (VB and DB) innervate both body-wall muscle cells and GABAergic motor neurons (VD and DD), the latter of which inhibit the activity of contralateral body wall muscles by GABA release. The premotor interneurons AVA and PVC, which regulate the forward locomotor program, are shown. Figure is adapted from wormatlas.org. (B) The amplitude-to-body length and (C) wave length-to-body length ratios during spontaneous crawling were analyzed in twk-7(null) and wild-type worms, respectively, expressing the wild-type and the dominant-negative G282C forms of TWK-7 at the level of A-type, B-type, and D-type motor neurons. Dotted lines indicate the respective wild-type level. Values represent the means (± SEM) of N ≥ 3 independent experiments involving n ≥ 30 animals. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). (D) Examples of S-shape body curvatures of N2 wild-type, twk-7(nf120) mutant, and transgenic animals during spontaneous crawling are depicted. Worms overexpressing TWK-7 under the control of the twk-7 promoter (Ex[twk-7p::TWK-7]), the cholinergic neuron-specific {Ex[unc-17p(4.2 kb)::TWK-7]}, or the cholinergic motor neuron-specific unc-17 promoter {Ex[unc-17(1 kb)p::TWK-7]} frequently exhibited two overlapping S-shape curvatures during spontaneous crawling, thereby generating an additional phase (green dot). The colored dots mark the phases (yellow, 0; red, π; blue, 2π; and green, 3π) of wave propagation. The corresponding body lengths, wave lengths, and amplitudes of each worm determined by ImageJ are presented below.

To further unravel the relationship between TWK-7 expression and wave shape modulation, we next analyzed the effects of an impaired TWK-7 function and of TWK-7 overexpression on amplitudes and wave lengths at the level of the cholinergic motor neurons. Similar to twk-7(null) mutants, transgenic wild-type worms expressing the dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C) allele in cholinergic motor neurons [driven by the unc-17(1 kb) promoter] or solely in B-type motor neurons (driven by the acr-5 promoter) moved with ∼13% reduced amplitude-to-body length ratios when compared to wild type (Figure 8B). The amplitude-to-body length ratios were not affected by TWK-7(G282C) expression in A-type (driven by the unc-4 promoter) or D-type motor neurons (driven by the unc-47 promoter). Moreover, for all transgenic wild-types expressing the dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C), the wave length-to-body length ratios were wild-type-like (Figure 8C).

When the wild-type form of TWK-7 was overexpressed in cholinergic motor neurons [unc-17(1 kb) promoter] or solely in the B-type motor neurons (acr-5 promoter) of twk-7(null) mutants, the amplitude-to-body length ratios were reduced by ∼10 and 20% when compared to nontransgenic twk-7(null) and wild-type animals, respectively (Figure 8B). Moreover, animals overexpressing TWK-7 under its own or both unc-17 promoter variants frequently initiated an additional wave along their bodies during spontaneous forward crawling (Figure 8D and File S6) thereby showing reduced amplitude-to-body length and wave length-to-body length ratios (Figure 8D). Notably, the overexpression of the wild-type form of TWK-7 in D-type motor neurons of twk-7(null) worms (driven by the unc-47 promoter) induced drastic increases of the amplitude-to-body length ratios that were found to be ∼35 and 40% higher than in wild-type and twk-7(null) animals, respectively (Figure 8B and File S5). Moreover, the wave length-to-body length ratios were increased by ∼10% in these transgenics when compared to the corresponding nontransgenics (Figure 8C). Remarkably, expression of the wild-type form of TWK-7 in cholinergic A-type motor neurons of twk-7(null) worms (driven by the unc-4 promoter) did not affect the wave parameters. These animals exhibited twk-7(null) phenotype. All transgenics that exhibited reduced crawling activity (Figure 7A) also had decreased wave velocities (Figure S6D).

Summarizing, the abundance of functional TWK-7 at the level of B- and D-type motor neurons affects the wave lengths and amplitudes during spontaneous crawling. An impaired TWK-7 in B-type neurons is sufficient to reduce the wave amplitude, whereas overexpression of wild-type TWK-7 in D-motor neurons is sufficient to elevate the wave amplitude. Increasing twk-7 expression specifically in B-type neurons was sufficient to frequently induce an additional wave during spontaneous crawling.

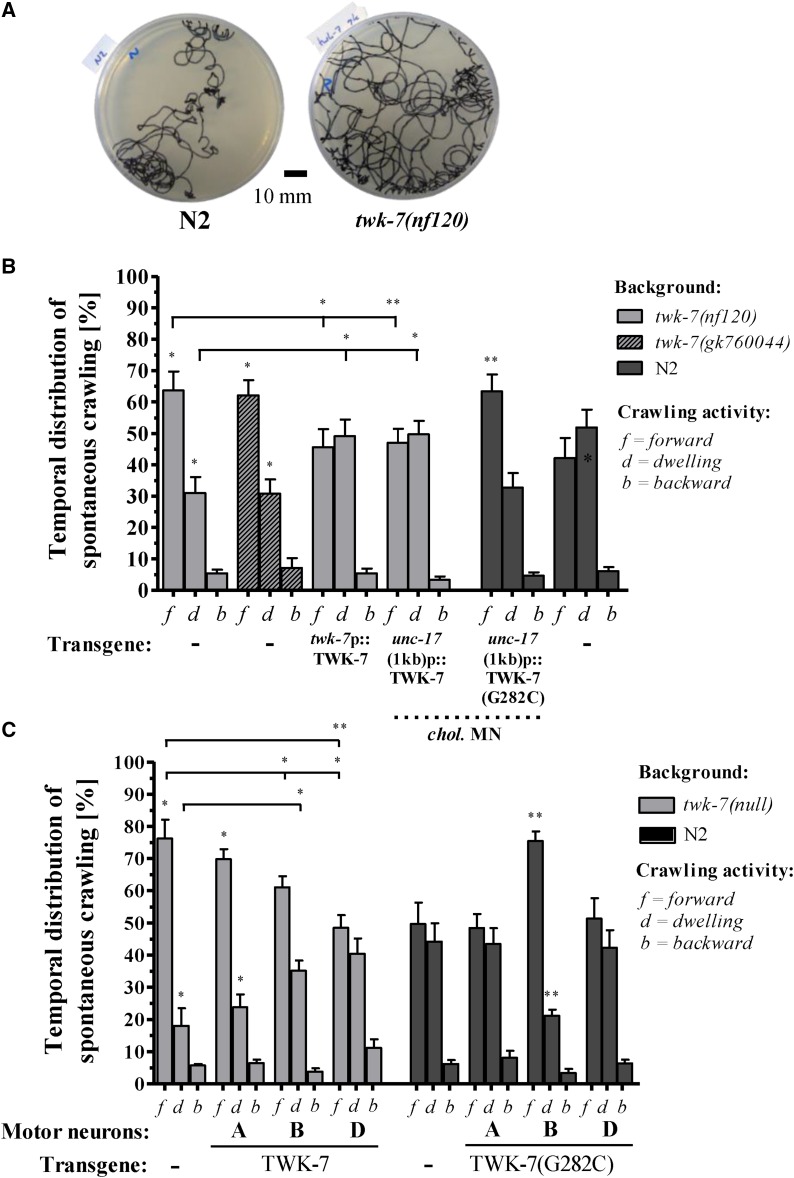

TWK-7 abundance in cholinergic B-type and GABAergic D-type motor neurons affects the duration of spontaneous forward crawling

Our findings on the impact of TWK-7 on locomotion activity prompted us to investigate whether the temporal distribution of crawling forward, crawling backward, and dwelling is affected in the twk-7(null) mutants. The inspection of tracks generated by twk-7(null) mutants over a longer time period (17 hr) revealed that the area explored by the mutant worms was noticeably larger than the area covered by wild-types animals (Figure 9A). Consistently, compared to wild type, these animals spent more time on crawling forward in expense of reduced dwelling times, while the relative duration of crawling backward was not altered (Figure 9B). Wild-type worms crawled 41.9 ± 17.5% of their time in the forward mode and 54.5 ± 15.8% of their time they rested, whereas, the respective values of twk-7(nf120) were 63.7 ± 14.9% and 31.0 ± 12.7%. Mutants carrying the twk-7(gk760044) allele also allocated their time preferentially to crawling forward (62.1 ± 9.7% crawling forward and 30.8 ± 9.1% dwelling). Expression of TWK-7 under its own promoter as well as under the cholinergic motor neuron-specific promoter completely rescued the crawling behavior phenotype of twk-7(null) (Figure 9B). In accordance with this rescue approach, impairing TWK-7 channel function by expressing the dominant-negative mutant variant TWK-7(G282C) in cholinergic motor neurons of wild-type worms led to a temporal distribution of crawling behaviors similar to twk-7(null) (Figure 9B). Regarding the subtype level of motor neurons, transgenic twk-7(nf120) animals expressing acr-5p::TWK-7 (B-type motor neurons) and unc-47p::TWK-7 (D type) spent more time on dwelling and less time on forward crawling than the twk-7(null). Wild-type worms carrying the dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C) in the B-type motor neurons exhibited similar increased forward crawling activity like the twk-7(null) mutants. These transgenics spent more time in the state of forward crawling and exhibited shorter dwelling periods than the nontransgenic wild types (Figure 9C). The dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C) construct expressed in GABAergic D-type neurons had no influence on the duration of forward crawling and dwelling. Overall, the action of TWK-7 in cholinergic B-type and GABAergic D-type motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord influences the persistence of forward crawling.

Figure 9.

Loss of TWK-7 function in cholinergic motor neurons increases the duration of spontaneous forward crawling. (A) For long-term analyses of spontaneous C. elegans locomotion activity, the crawling tracks of single worms incubated for 17 hr on standard NGM plates are depicted. (B) The persistence of forward and backward crawling and dwelling periods was analyzed in animals overexpressing the wild-type and the dominant-negative form G282C of TWK-7 in the twk-7-specific neurons, all cholinergic motor neurons [unc-17(4.2 kb)p], the cholinergic motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord [unc-17(1.0 kb)p], and (C) in the A-, B-, and D-type motor neuron subtypes. Dotted lines indicate the respective wild-type level. Values represent the means (± SEM) of at least N ≥ 3 independent experiments involving n ≥ 30 animals. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

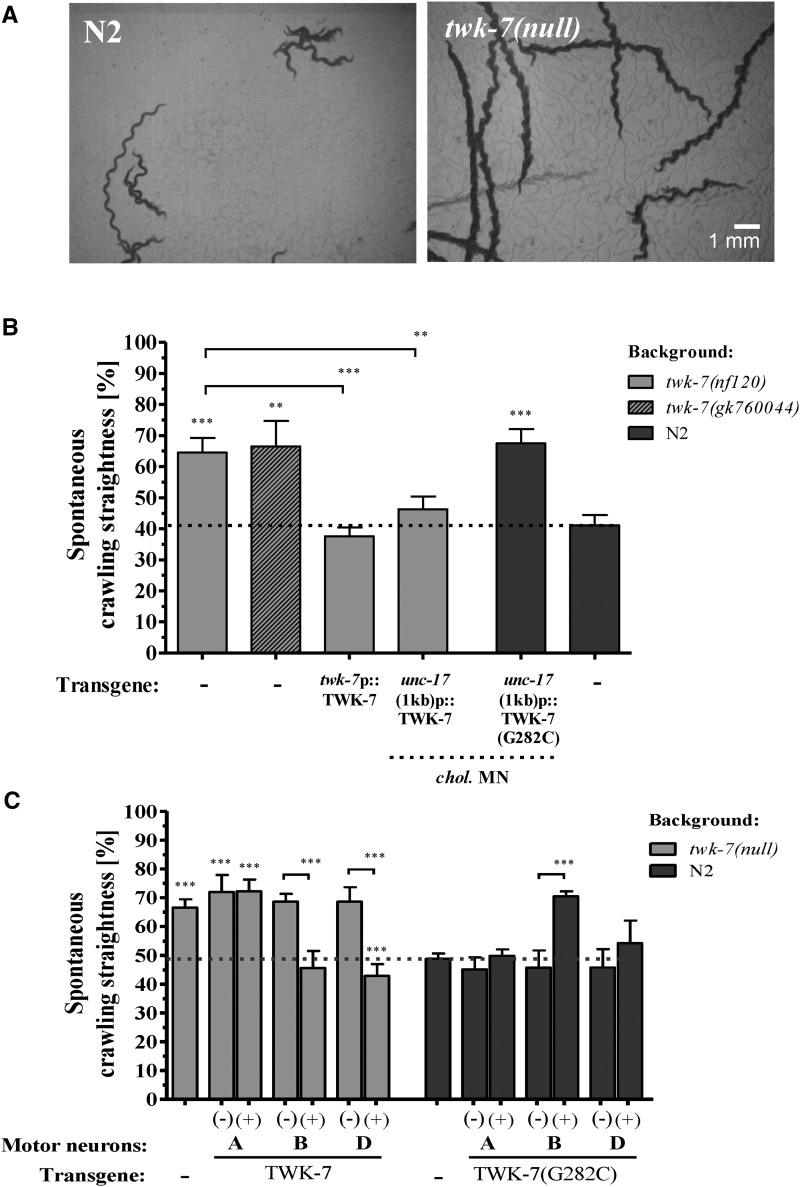

TWK-7 abundance in cholinergic B-type and GABAergic D-type motor neurons affects the straightness of forward crawling

We noticed that the straightness of crawling forward, which is defined by the ratio of distance to track length, was improved in twk-7(null) mutants (Figure 10A). It was found to be 43.1 ± 11.8% for wild-type compared to 64.5 ± 11.6% for twk-7(null) and 67.5 ± 16.8% for twk-7(gk760044), respectively. This crawling behavior phenotype was rescued by TWK-7 expression driven by its own, by the cholinergic motor neuron-specific, by the B-type motor neuron-specific, and by the D-type motor neuron-specific promoter, respectively (Figure 10, B and C). Overexpression of both TWK-7 and TWK-7(G282C) in A-type motor neurons of twk-7(null) and wild type, respectively, had no influence on the straightness of forward crawling. However, when expressed in the B-type motor neurons of wild-type worms, the dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C) construct resulted in an improved straightness similar to twk-7(null), while its expression in GABAergic D-type neurons had no influence on the straightness of forward crawling. Taken together, these data indicate that functional TWK-7 is required in the cholinergic excitatory B-type and inhibitory GABAergic D-type motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord not only to maintain normal spontaneous locomotion activity but also normal spontaneous locomotion behavior.

Figure 10.

Loss of TWK-7 function in cholinergic motor neurons increases the straightness of spontaneous forward crawling. (A) Representative 1-min locomotion tracks of twk-7(null) and N2 wild types. (B) The straightness of forward crawling was analyzed in twk-7(null) and wild-type worms overexpressing the wild-type and the dominant-negative form G282C of TWK-7 in the twk-7-specific neurons, all cholinergic motor neurons [unc-17(4.2 kb)p], the cholinergic motor neurons of the ventral nerve cord [unc-17(1.0 kb)p], and (C) in the cholinergic and GABAergic motor neuron subtypes. The transgenics (+) are directly compared with nontransgenic (−) siblings. Dotted lines indicate the respective wild-type level. Values represent the means (± SEM) of N ≥ 3 independent experiments involving n ≥ 30 animals. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

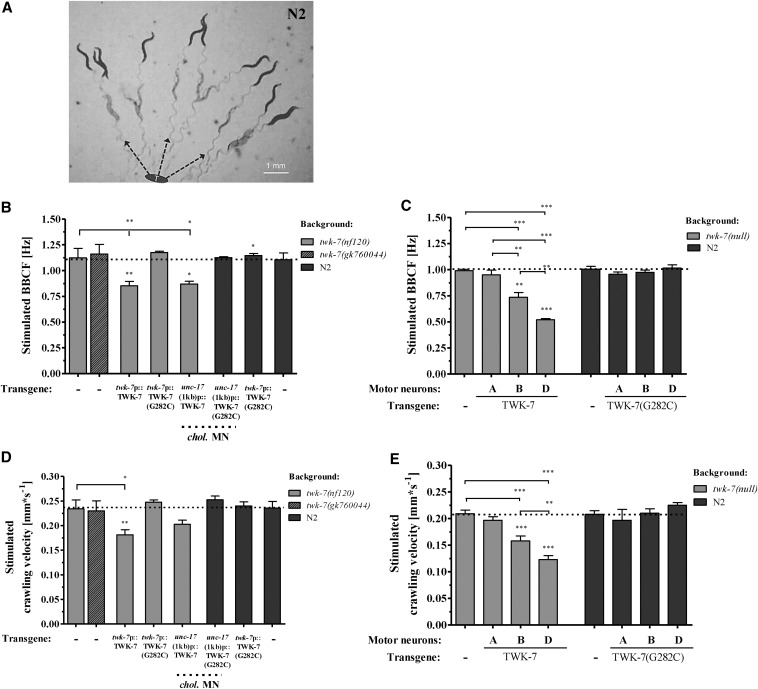

Loss of TWK-7 function affects locomotion parameters in a manner characteristic of stimulated locomotion behavior

Compared to wild type, crawling of twk-7-deficient mutants and of transgenics overexpressing a dominant-negative from of TWK-7 is characterized by (i) an increased activity preferentially on crawling forward, (ii) an extended time spent on crawling forward, and (iii) an improvement of the straightness of crawling forward. Remarkably, we found that these parameters were similarly affected in wild-type animals stimulated by the picking transfer assay (Figure 11B, File S7, and File S8). The stimulated worms dramatically increased their forward crawling activities ∼2.8-fold (Figure S5, A and B and Figure 11, B–E), straightness rates about twofold (Figure 10, B and C and Figure 11, F and G), and also reduced their amplitude to body length ratios by ∼15% to the level of spontaneously crawling twk-7(null) mutants (Figure 8B, Figure 11H, and Figure S7). Consequently, it is tempting to speculate that TWK-7 might be involved in a forward escape or foraging behavior. To further test our hypothesis, we have developed a forward escape score that is based on the distribution of time spent on spontaneous crawling forward, the straightness of spontaneous forward movement, and the spontaneous velocity. This escape score is approximately four times higher in both twk-7(null) mutants compared to wild type (Table 1). Expression of TWK-7::mCherry under its own promoter as well as under the cholinergic motor neuron-specific promoter rescued the increased escape score of twk-7(null) mutants to the wild-type level (Table 1). In contrast to that and consistent with the results presented above, the escape score of N2 wild-type worms that expressed the dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C) mutant protein in TWK-7-specific neurons or in cholinergic motor neurons was found to be similarly elevated, as seen for twk-7(null) (Table 1). These results underline our hypothesis that TWK-7 may be specifically involved in escape-like locomotion behaviors by enhancing the activity, duration, and straightness and adjusting the wave parameters of moving forward.

Figure 11.

Stimulation of C. elegans forward crawling affects five locomotion parameters that are similarly altered in twk-7(null) mutants and TWK-7(G282C) transgenics during spontaneous crawling. (A) To assay the stimulated crawling activity, groups of 10 young adult worms (age 72 hr) were transferred to a new NGM agar plate and recorded immediately by camera. As shown here for wild-type worms, the animals leave the transfer point “T” by crawling straight forward (indicated by dotted arrows). Two pictures of the same movie are overlaid showing the position of worms at time point 0 sec (pale worms) and 10 sec (dark worms). (B and C) The stimulated BBCFs and (D and E) the respective velocities of stimulated forward crawling were immediately determined for wild-type, twk-7(nf120), and transgenic animals. (F and G) The straightness rates, (H) amplitude-to-body length, and (I) wave length-to-body length ratios of stimulated nontransgenics and transgenics are depicted. Dotted lines indicate the respective wild-type level. Values in B–I represent the means (± SEM) of N ≥ 3 independent experiments involving n ≥ 30 animals. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

Table 1. Escape scores of TWK-7(null) animals compared to N2 wild types and transgenic strains overexpressing the wild-type form of TWK-7 or the mutant channel TWK-7(G282C).

| Allele/transgenic | % Time forward (Tfw) | Straightness (St) | Velocity rate V(v/vs) | Escape score (Tfw × St × V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | 0.42 ± 0.17 | 0.43 ± 0.12 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | 0.07 |

| twk-7(nf120) | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.65 ± 0.12 | 0.64 ± 0.05 | 0.26 |

| twk-7(gk760044) | 0.62 ± 0.10 | 0.68 ± 0.17 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 0.27 |

| Ex[twk-7p:TWK-7]a | 0.46 ± 0.14 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Ex[twk-7p:TWK-7(G282C)]a | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Ex[twk-7p:TWK-7(G282C)]b | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 0.28 |

| Ex[unc-17(1 kb)p:TWK-7]a | 0.47 ± 0.12 | 0.46 ± 0.11 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Ex[unc-17(1 kb)p:TWK-7(G282C)]b | 0.63 ± 0.14 | 0.67 ± 0.12 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 0.22 |

The velocity rate V reflects the ratio between stimulated (v) and spontaneous velocity (vs). The values for percentage of time crawling forward (Tfw), straightness (St), and the velocity rate (V) represent the means ± SD.

twk-7(nf120) background.

N2 background.

Next, we investigated how the constitutively hyperactive phenotype of twk-7(null) mutants is affected by picking transfer stimulation. Although starting from a hyperactive state under nonstimulated conditions, these animals further increased their forward crawling activity ∼1.6-fold (Figure S5, A and B and Figure 11, B–E), and straightness rates ∼1.5-fold (Figure 10, B and C and Figure 11, F and G), however, only up to the level of the stimulated wild-type worms. Therefore, the picking-transfer process induced activating pathways that led to a further increase in these locomotion parameters. The amplitude-to-body length ratios of twk-7(null) worms remained unchanged after stimulation when compared to the spontaneous crawling conditions (Figure 8B and Figure 11H). Hence, the locomotion parameters of stimulated wild-type match those of stimulated twk-7(null) animals. Consistently, the expression of the dominant-negative TWK-7(G282C) in wild types did not induce any significant effects on the stimulated wild-type crawling (Figure 11, B–I).

Rescued twk-7(null) mutant worms that overexpressed wild-type TWK-7 under the twk-7 promoter were not able to reach the stimulated forward crawling activity exhibited by wild-type as well as by twk-7(null) animals (Figure 11, B and D and File S9). This effect was also observed by overexpression of TWK-7 in the entire set of cholinergic, B-type, or D-type motor neurons (Figure 11, C and E). The generation of the above-mentioned additional wave seen during spontaneous crawling in rescued animals occurred more frequently after picking-transfer stimulation (File S9).

Although our current data do not allow drawing the conclusion that TWK-7 contributes to the stimulated forward crawling behavior, we found that wild-type worms respond to the external stimulation by changing their crawling parameters reminiscent of the spontaneous hyperactive locomotion phenotype of twk-7(null).

Discussion

Here we have shown that the C. elegans K2P channel TWK-7 is required to maintain both normal spontaneous rhythmic locomotor activity and normal spontaneous locomotion behavior. In spite of predicted biochemical similarities within the C. elegans TWK family (Salkoff et al. 2001; Kratsios et al. 2012), we found that the locomotion phenotypes of two different twk-7(null) alleles were distinct from several other twk mutants. Our data indicate that these functions can be ascribed to a cholinergic B-type and GABAergic D-type neuron-specific expression of TWK-7.

In the past two decades by means of molecular and electrophysiological methods, it has been recognized that the eukaryotic K2P channels are regulatory K+ selective leak channels that modify the membrane potential of neurons and other cell types (Enyedi and Czirjak 2010). Nevertheless, data defining the physiological role of native K2P channels are still limited. In principle, activated K2P channels hyperpolarize the membrane potential by increasing potassium permeability. Diametrically opposed, closure or a genetic knockout of K2P channels depolarizes the membrane potential, resulting in an increased excitability of cells (Enyedi and Czirjak 2010). Accordingly, we suggest that the enhanced spontaneous locomotion activity of twk-7(null) animals is caused by an elevated excitability of neurons. This acceleration of twk-7(null) worms also implies that in wild-type worms, TWK-7 is activated during spontaneous crawling. An activated K2P channel lowers the excitability of cells and, to that effect, overexpressing TWK-7 reduced the locomotor activity of twk-7(null) mutants even slightly below that of wild-type worms. Moreover, the additional wave that appears in worms with overexpressed TWK-7 channels can be explained by a reduced excitability of motor neurons that leads to decreased wave lengths and bending frequencies causing a slowed down forward propagation of the wave. The proprioception mechanism that is transduced by B-type cholinergic motor neurons (Wen et al. 2012) may be involved here, given that a postulated rhythmic generator near the head initiates a certain wave frequency. The respective rhythmic wave initiation pattern appears to be periodically out of phase. Since the activity of K2P channels requires a dimeric structure (Enyedi and Czirjak 2010), the expression of TWK-7 mutant channels with disabled potassium selectivity filter should have an antimorphic effect by binding and thus inactivating the normal wild-type channels. As expected, the expression of the mutant channel TWK-7(G282C) solely in cholinergic excitatory B-type motor neurons did not influence the elevated locomotor activity of twk-7(loss of function) mutants but increases the activity of wild-type worms. Worthy of note, in contrast to the classical uncoordinated C. elegans mutants (Brenner 1974) which impair normal behavior and mainly define constitutive elements of neuromuscular functions, the twk-7(loss of function) mutants and the TWK-7(G282C) transgenics showed coordinated, directed, and accelerated locomotion within a physiological range. Knockout models and pharmacological approaches in the fly and in mammals suggested that K2P channels are involved in the regulation of rhythmic muscle activity (Kunkel et al. 2000; de la Cruz et al. 2003, 2014; Aller et al. 2005; Lalevee et al. 2006; Decher et al. 2011; Donner et al. 2011). For example, the heart rate of Drosophila melanogaster was accelerated by the cardiac-specific inactivation of the K2P channel ORK1 via RNA interference (RNAi), while overexpression of ORK1 led to the stoppage of heart beating. Similarly, pharmacological activation of the K2P channel TASK is associated with decreased motor neuronal excitability, which most likely contributes to the immobilizing effect of anesthetics (Lazarenko et al. 2010). In good accordance with these reported findings, we suggest that our data may point to a regulatory function of C. elegans TWK-7 in cholinergic B-type motor neurons. Alternatively, a genuine regulator of locomotor activity may act upstream of TWK-7 within the same motor neurons or in upstream neurons (e.g., interneurons). However, up to now, we cannot exclude that the activity of TWK-7 in motor neurons may represent a relevant background condition but not a mode of regulation in the context of spontaneous C. elegans locomotion.

According to the locomotion circuit diagram shown in Figure 8A, activated cholinergic B-type motor neurons synapse on both the related body-wall muscles and the corresponding GABAergic D-type motor neurons, which then inhibit the contralateral body-wall muscles. These inhibitory GABAergic motor neurons have been reported to be not essential for rhythmic activity during forward crawling (McIntire et al. 1993). Here, we found that adequate TWK-7 expression is required in D-type GABAergic motor neurons to maintain both activity and straightness of spontaneous movement, suggesting that the excitability of these motor neurons may be important for specific locomotion behaviors. In particular, overexpression of TWK-7 in D-type motor neurons was found to counteract the changes in locomotor activity and behavior of twk-7(null) mutants. Given that B-type motor neurons activate the contralateral inhibitory D-type motor neurons, we assume that a specifically reduced excitability of D-type motor neurons due to TWK-7 overexpression may represent a limiting step in the otherwise elevated B-type motor neuron-driven rhythmic muscle contraction of twk-7(null) mutants. Here, both muscle contraction and contralateral muscle relaxation are altered. Hyperexcitability of B-type motor neurons most probably elicits hypercontraction of body-wall muscles and in accordance with the study of Donnelly et al. (2013), a hypoexcited D-type motor neuron impairs relaxation of body-wall muscle, which leads to a more pronounced wave amplitude. However, these manipulations specifically affected dorsal or ventral GABAergic activity, generating a directional bias. In our studies we observed that the twk-7(null) worms expressing native TWK-7 in GABAergic motor neurons moved slowly and uncoordinatedly, exhibiting larger S-shapes with higher amplitudes. A role of the GABAergic neurons in regulating shape and amplitude of the worms is in agreement with the literature (McIntire et al. 1993; Yanik et al. 2004; Bryden and Cohen 2008).

In contrast to the situation in the excitatory B-type motor neurons, an impaired TWK-7(G282C) channel was not able to induce increased velocity, straightness, and duration of forward movement or affect the wave form in wild-type animals via D-type motor neuron-specific overexpression. Based on the neuronal locomotion circuit, the muscle contraction and D-type motor neuron-dependent contralateral body-wall muscle relaxation is B-type motor neuron dependent. Apparently, a potentially faster muscle relaxation caused by the hyperexcited D-type motor neuron is not able to affect the next contraction by the ipsilateral B-type motor neuron. Hence, an increased excitability of D-type motor neurons due to expression of an inactivated TWK-7 channel does not affect the rhythm and wave form of unstimulated forward crawling in wild-type worms. However, we can not exclude that cell-type-specific differences in channel morphology or regulation might implicate distinct functions of TWK-7 in cholinergic and GABAergic motor neurons, accounting for the lack of a dominant-negative effect of TWK-7(G282C) in GABAergic motor neurons.

It is an interesting question how inactivation of TWK-7 in cholinergic motor neurons causes preferentially forward movement. It has been shown that distinct premotor interneurons (AVA, AVE, AVD, AVB, and PVC) innervate the A- and B-type motor neurons to drive backward and forward movement (Chalfie et al. 1985; Zheng et al. 1999). Moreover, the cross-inhibition between the forward and backward circuit and the premotor interneuron–motor neuron coupling via gap junctions has been demonstrated to establish an imbalanced motor neuron output in favor of forward locomotion (Zheng et al. 1999; Kawano et al. 2011). The forward circuit is generally active and represents the default mode of locomotion direction, whereas the backward circuit is rather proactive, regulated by touch and other stimuli (Chalfie et al. 1985). Similar models of the neuronal control of locomotion direction have been unraveled in Drosophila (Bidaye et al. 2014), crickets (Schoneich et al. 2011), and cockroaches (Burdohan and Comer 1996). All of these models predict that higher excitability of the motor neurons reinforces the activity of the forward circuit. In line with this prediction, we have shown that a closed TWK-7 channel solely in cholinergic B-type motor neurons is sufficient to enhance the duration of forward movement at the expense of dwelling times.

Moreover, it is quite remarkable that loss of TWK-7 function solely in B-type motor neurons was sufficient to enhance the straightness of spontaneous crawling. We suggest that at least two factors are responsible for this locomotion phenotype. First, the lower backward crawling rate of twk-7(null) worms improves the straightness, because in C. elegans reorientation is frequently associated with backing events (Donnelly et al. 2013). Second, the lower amplitudes of twk-7(null) worms during forward crawling may favor a more directed movement.

The regulation of velocity, duration, and direction of movement in response to external and internal cues is a hallmark of adaptive locomotion behavior. Escape behaviors and foraging are important examples for this. In agreement with a previous report (Gaglia and Kenyon 2009), we found that the transfer of worms to new assay plates by a platinum wire stimulates fast straightforward crawling when comparing to spontaneous movement. Since this effect—although declining—persists (Figure S8), we suggest that it might reflect an escape-like behavior rather than an escape reflex. Spontaneously moving twk-7(null) mutants did not reach the activity level of stimulated wild-type worms, indicating that, if TWK-7 is involved in this adaptive locomotion behavior, additional activating pathways are required. Although our current data do not allow drawing the conclusion that twk-7 contributes to this stimulated escape-like behavior, it is quite remarkable that five central aspects of locomotion—velocity/frequency, wave parameters, forward direction, duration, and straightness—that are constitutively affected by loss of TWK-7 function are also induced by external stimulation. Thus, we suggest that TWK-7—together with other factors—may act as a putative player in the context of fast-targeted forward locomotion. Since the K2P channels are regulated by a huge number of stimuli (Enyedi and Czirjak 2010), preferentially the N- and C-terminal regions of TWK-7 might constitute a direct target for regulators such as protein kinases and/or fatty acids. It will be particularly important to test this hypothesis in order to get insight into the pathways that regulate TWK-7.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Schnabel and G. Rimbach for comments on the manuscript, as well as A. Reinke and F. Neumann for processing of plates and strains. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.116.188896/-/DC1.

Communicating editor: P. Sengupta

Literature Cited

- Aller M. I., Veale E. L., Linden A. M., Sandu C., Schwaninger M., et al. , 2005. Modifying the subunit composition of TASK channels alters the modulation of a leak conductance in cerebellar granule neurons. J. Neurosci. 25: 11455–11467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Arous J., Laffont S., Chatenay D., 2009. Molecular and sensory basis of a food related two-state behavior in C. elegans. PLoS One 4: e7584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidaye S. S., Machacek C., Wu Y., Dickson B. J., 2014. Neuronal control of Drosophila walking direction. Science 344: 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle J. H., Berri S., Cohen N., 2012. Gait modulation in C. elegans: an integrated neuromechanical model. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 6: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryden J., Cohen N., 2008. Neural control of Caenorhabditis elegans forward locomotion: the role of sensory feedback. Biol. Cybern. 98: 339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham S. D., Kidd J. F., Law R. J., Franks C. J., Sattelle D. B., 2005. Structure and function of two-pore-domain K+ channels: contributions from genetic model organisms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26: 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdohan J. A., Comer C. M., 1996. Cellular organization of an antennal mechanosensory pathway in the cockroach, Periplaneta americana. J. Neurosci. 16: 5830–5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M., Sulston J. E., White J. G., Southgate E., Thomson J. N., et al. , 1985. The neural circuit for touch sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 5: 956–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. A., Gabel C. V., Lee T. M., Samuel A. D., 2007. Short-term adaptation and temporal processing in the cryophilic response of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurophysiol. 97: 1903–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz I. P., Levin J. Z., Cummins C., Anderson P., Horvitz H. R., 2003. sup-9, sup-10, and unc-93 may encode components of a two-pore K+ channel that coordinates muscle contraction in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 23: 9133–9145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz I. P., Ma L., Horvitz H. R., 2014. The Caenorhabditis elegans iodotyrosine deiodinase ortholog SUP-18 functions through a conserved channel SC-box to regulate the muscle two-pore domain potassium channel SUP-9. PLoS Genet. 10: e1004175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decher N., Wemhoner K., Rinne S., Netter M. F., Zuzarte M., et al. , 2011. Knock-out of the potassium channel TASK-1 leads to a prolonged QT interval and a disturbed QRS complex. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 28: 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly J. L., Clark C. M., Leifer A. M., Pirri J. K., Haburcak M., et al. , 2013. Monoaminergic orchestration of motor programs in a complex C. elegans behavior. PLoS Biol. 11: e1001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner B. C., Schullenberg M., Geduldig N., Huning A., Mersmann J., et al. , 2011. Functional role of TASK-1 in the heart: studies in TASK-1-deficient mice show prolonged cardiac repolarization and reduced heart rate variability. Basic Res. Cardiol. 106: 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi P., Czirjak G., 2010. Molecular background of leak K+ currents: two-pore domain potassium channels. Physiol. Rev. 90: 559–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang-Yen C., Wyart M., Xie J., Kawai R., Kodger T., et al. , 2010. Biomechanical analysis of gait adaptation in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 20323–20328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix M. A., Braendle C., 2010. The natural history of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 20: R965–R969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaglia M. M., Kenyon C., 2009. Stimulation of movement in a quiescent, hibernation-like form of Caenorhabditis elegans by dopamine signaling. J. Neurosci. 29: 7302–7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjorgjieva J. B. D., Haspel G., 2014. Neurobiology of Caenorhabditis elegans locomotion: Where do we stand? Bioscience 64: 476–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granato M., Schnabel H., Schnabel R., 1994. pha-1, a selectable marker for gene transfer in C. elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 1762–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J., Lissmann H. W., 1964. The locomotion of nematodes. J. Exp. Biol. 41: 135–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T., Po M. D., Gao S., Leung G., Ryu W. S., et al. , 2011. An imbalancing act: gap junctions reduce the backward motor circuit activity to bias C. elegans for forward locomotion. Neuron 72: 572–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollewe A., Lau A. Y., Sullivan A., Roux B., Goldstein S. A., 2009. A structural model for K2P potassium channels based on 23 pairs of interacting sites and continuum electrostatics. J. Gen. Physiol. 134: 53–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratsios P., Stolfi A., Levine M., Hobert O., 2012. Coordinated regulation of cholinergic motor neuron traits through a conserved terminal selector gene. Nat. Neurosci. 15: 205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel M. T., Johnstone D. B., Thomas J. H., Salkoff L., 2000. Mutants of a temperature-sensitive two-P domain potassium channel. J. Neurosci. 20: 7517–7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalevee N., Monier B., Senatore S., Perrin L., Semeriva M., 2006. Control of cardiac rhythm by ORK1, a Drosophila two-pore domain potassium channel. Curr. Biol. 16: 1502–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarenko R. M., Willcox S. C., Shu S., Berg A. P., Jevtovic-Todorovic V., et al. , 2010. Motoneuronal TASK channels contribute to immobilizing effects of inhalational general anesthetics. J. Neurosci. 30: 7691–7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwar B., Westmark S., Buschges A., Schmidt J., 2005. Modulation of membrane potential in mesothoracic moto- and interneurons during stick insect front-leg walking. J. Neurophysiol. 94: 2772–2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luersen K., Faust U., Gottschling D. C., Doring F., 2014. Gait-specific adaptation of locomotor activity in response to dietary restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Exp. Biol. 217: 2480–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Gabel C. V., Ha H. I., Zhang Y., Samuel A. D., 2008. Olfactory behavior of swimming C. elegans analyzed by measuring motile responses to temporal variations of odorants. J. Neurophysiol. 99: 2617–2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majmudar T., Keaveny E. E., Zhang J., Shelley M. J., 2012. Experiments and theory of undulatory locomotion in a simple structured medium. J. R. Soc. Interface 9: 1809–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E., Calabrese R. L., 1996. Principles of rhythmic motor pattern generation. Physiol. Rev. 76: 687–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire S. L., Jorgensen E., Kaplan J., Horvitz H. R., 1993. The GABAergic nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 364: 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. G., Emerson M. D., Rand J. B., 1999. Goalpha and diacylglycerol kinase negatively regulate the Gqalpha pathway in C. elegans. Neuron 24: 323–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Hwang H., Nam S. W., Martinez F., Austin R. H., et al. , 2008. Enhanced Caenorhabditis elegans locomotion in a structured microfluidic environment. PLoS One 3: e2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier J. F., Alaburda A., Hounsgaard J., 2003. 5–HT1A receptors increase excitability of spinal motoneurons by inhibiting a TASK-1-like K+ current in the adult turtle. J. Physiol. 548: 485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C., Dirksen P., Schulenburg H., 2015. Why we need more ecology for genetic models such as C. elegans. Trends Genet. 31: 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce-Shimomura J. T., Chen B. L., Mun J. J., Ho R., Sarkis R., et al. , 2008. Genetic analysis of crawling and swimming locomotory patterns in C. elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 20982–20987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkoff L., Butler A., Fawcett G., Kunkel M., McArdle C., et al. , 2001. Evolution tunes the excitability of individual neurons. Neuroscience 103: 853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin E. R., Ranganathan R., Horvitz H. R., 2000. C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway. Neuron 26: 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoneich S., Schildberger K., Stevenson P. A., 2011. Neuronal organization of a fast-mediating cephalothoracic pathway for antennal-tactile information in the cricket (Gryllus bimaculatus DeGeer). J. Comp. Neurol. 519: 1677–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber M. A., Pierce-Shimomura J. T., Chan S., Parry D., McIntire S. L., 2010. Manipulation of behavioral decline in Caenorhabditis elegans with the Rag GTPase raga-1. PLoS Genet. 6: e1000972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P., Samuel A. D., 2009. Caenorhabditis elegans: a model system for systems neuroscience. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19: 637–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtonda B. B., Avery L., 2006. Dietary choice behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Exp. Biol. 209: 89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swierczek N. A., Giles A. C., Rankin C. H., Kerr R. A., 2011. High-throughput behavioral analysis in C. elegans. Nat. Methods 8: 592–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Q., Po M. D., Hulme E., Chen S., Liu X., et al. , 2012. Proprioceptive coupling within motor neurons drives C. elegans forward locomotion. Neuron 76: 750–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. G., Southgate E., Thomson J. N., Brenner S., 1976. The structure of the ventral nerve cord of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 275: 327–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilm T., Demel P., Koop H. U., Schnabel H., Schnabel R., 1999. Ballistic transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 229: 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanik M. F., Cinar H., Cinar H. N., Chisholm A. D., Jin Y., et al. , 2004. Neurosurgery: functional regeneration after laser axotomy. Nature 432: 822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Brockie P. J., Mellem J. E., Madsen D. M., Maricq A. V., 1999. Neuronal control of locomotion in C. elegans is modified by a dominant mutation in the GLR-1 ionotropic glutamate receptor. Neuron 24: 347–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.