Abstract

Genes that code for proteins involved in organelle biogenesis and intracellular trafficking produce products that are critical in normal cell function . Conserved orthologs of these are present in most or all eukaryotes, including Drosophila melanogaster. Some of these genes were originally identified as eye color mutants with decreases in both types of pigments found in the fly eye. These criteria were used for identification of such genes, four eye color mutations that are not annotated in the genome sequence: chocolate, maroon, mahogany, and red Malpighian tubules were molecularly mapped and their genome sequences have been evaluated. Mapping was performed using deletion analysis and complementation tests. chocolate is an allele of the VhaAC39-1 gene, which is an ortholog of the Vacuolar H+ ATPase AC39 subunit 1. maroon corresponds to the Vps16A gene and its product is part of the HOPS complex, which participates in transport and organelle fusion. red Malpighian tubule is the CG12207 gene, which encodes a protein of unknown function that includes a LysM domain. mahogany is the CG13646 gene, which is predicted to be an amino acid transporter. The strategy of identifying eye color genes based on perturbations in quantities of both types of eye color pigments has proven useful in identifying proteins involved in trafficking and biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles. Mutants of these genes can form the basis of valuable in vivo models to understand these processes.

Keywords: genetic analysis, vesicular transporters, LysM domain in eukaryotes

Drosophila melanogaster is an extremely useful model organism for both classical genetics and molecular biology. It is also one of the earliest organisms to have its DNA sequence determined and extensively annotated. However, many of the genes identified and used in classical genetics have not been matched with their corresponding genes in the molecular sequence. This study identifies four genes coding for eye color mutations.

Certain eye color genes regulate vesicular transport in cells. Enzymes and other substances needed for pigment synthesis are transported to the pigment granule, a lysosome-related organelle (Dell’Angelica et al. 2000; Reaume et al. 1991; Summers et al. 1982). D. melanogaster has a red-brown eye color caused by the presence of two classes of pigments, pteridines (red) and ommochromes (brown). There are independent pathways for the synthesis of each (Reaume et al. 1991; Summers et al. 1982). Some eye color mutations are caused by the lack of individual enzymes in these pathways. Examples include bright red vermillion (tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase), which is incapable of synthesis of any ommochromes, and dark brown sepia (GSTO4), which lacks an enzyme used to synthesize a subset of pteridines (Baillie and Chovnick 1971; Kim et al. 2006; Searles and Voelker 1986; Searles et al. 1990; Walters et al. 2009; Wiederrecht and Brown 1984). The first mutant described in Drosophila, white, lacks both types of pigments in the eye (Morgan 1910). The white gene codes for a subunit of an ABC transporter located in the membrane of the pigment granule, and is required for transport of substrates into pigment granules (Goldberg et al. 1982; Mackenzie et al. 1999; Summers et al. 1982). Lloyd et al. (1998) developed a hypothesis that single mutations causing perturbations in the amount of both types of pigments in the eyes could result from defects in genes associated with intracellular transport. They named these genes “the granule group.” Their concept has been supported by both identification of existing eye color genes for which the genomic coding sequences were originally unknown, and by studies in which induced mutations or reduced expression of orthologs of known transporter genes resulted in defective eye color phenotypes.

Vesicular trafficking is critical. Each cell in the body is highly organized with a number of compartments. These must contain specific proteins and have distinct characters, such as pH, as well as specific molecules attached to them. Vesicular trafficking is accomplished by a large number of protein complexes and individual effector proteins, and the list of these is still growing. One mode of delivery involves endocytic trafficking resulting in the sorting of proteins, lipids, and other materials and directing them to specific vesicles/organelles (Li et al. 2013). Many of the relevant proteins were first identified in yeast and have been highly conserved (Bonifacino 2014). D. melanogaster eye color genes provide in vivo metazoan models of these proteins and their interactions in trafficking. For example, the adaptor protein 3 (AP3) complex consists of four proteins: the β3 (RUBY), δ3 (GARNET), μ3 (CARMINE), and σ3 (ORANGE) subunits. It is involved in cargo selection for vesicles, transport of soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor complexes, biogenesis of lysosomes, and lysosome-derived organelles, including formation of synaptic vesicles (Besteiro et al. 2008; Cowles et al. 1997; Faundez et al. 1998; Kent et al. 2012; Mullins et al. 1999, 2000; Ooi et al. 1997). The homotypic vacuole fusion and protein sorting (HOPS) complex in metazoans has four core proteins coded for by the Vps16A, Vps11, Vps18 (dor), and Vps33 (car) genes. Two additional proteins coded for by Vps39 and Vps41 (lt) can also be part of the complex. The HOPS complex participates in endocytic transport, endosome maturation, and fusion with lysosomes (Nickerson et al. 2009; Solanger and Spang 2013). Rab GTPases are molecular switches, active when coupled with GTP. The guanine exchange factor (GEF) catalyzes the conversion of GDP to GTP, activating its associated Rab GTPase. Rabs contribute to cargo selection, vesicle movement via microfilaments and actin, and fusion of membranes. Two eye color mutants, lightoid (Rab32) and claret (its putative GEF), have been shown to affect pigment granule morphology and autophagy; lightoid’s transcript has also been shown to be enriched in neurons. Human Rab32 participates in the transport of enzymes involved in melanin production to the melanosome, another lysosome-related organelle (Chan et al. 2011; Hutagalung and Novick 2011; Ma et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2012a; Zhen and Stenmark 2015). The human gene Lysosomal Trafficking Regulator Protein (LYST) is required for normal size and number of lysosomes and biogenesis of cytotoxic granules. Mutations in the gene are associated with Chediak–Higashi syndrome, which causes defects in immunity, prolonged bleeding, and oculocutaneous albinism. The fly ortholog, mauve, recapitulates some of these characteristics. It has overlarge pigment granules, abnormal eye color, and is susceptible to bacterial infection. It also lacks the ability to produce mature autophagosomes (Huizing et al. 2008; Rahman et al. 2012; Sepulveda et al. 2015). At least three sets of Biogenesis of Lysosome-related Organelle Complexes, BLOC1, BLOC2, and BLOC3, are required for normal development of these organelles (Dell’Angelica. 2004). The classic eye mutant, pink, is a member of BLOC2, an ortholog of Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome 5 (HPS5) and shows genetic interactions with AP3 genes, garnet and orange, and the HOPS gene carnation (Di Pietro et al. 2004; Falcon-Perez et al. 2007; Syrzycka et al. 2007). Finally, Drosophila orthologs of genes originally identified as BLOC1 genes in other organisms have produced an abnormal eye color phenotype when their expression was inhibited by RNAi. These include four of the BLOC1 genes, Blos1, Pallidin, Dysbindin, and Blos4 (Bonifacino 2004; Cheli et al. 2010; Dell’Angelica et al. 2000).

Using the perturbation in amounts of both ommochromes and pteridines as a criterion, we selected and identified the genomic sequence coding for each of four eye color genes in D. melanogaster: chocolate (cho), maroon (ma), mahogany (mah), and red Malpighian tubules (red). Two of the genes, cho and ma, are VATPase and VPS16a subunits, respectively. The roles of these annotated genes in vesicular transport have been previously characterized. The mah mutation also codes for a gene involved in transfer of amino acids to granules. Finally, the last gene, red, codes for a predicted protein with a LysM domain, but the protein’s function is unknown.

Materials and Methods

Nucleic acid isolation, RT-PCR, and production of transgenic flies

Fly DNA was isolated from single flies using the method of Gloor et al. (1993). The Parks et al. (2004) “5 Fly Extraction” was used to isolate purer DNA from groups of five to 10 flies at a time. The second technique was modified by using single microcentrifuge tubes and a tissue grinder for homogenizing. RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Life Technologies). cDNA was prepared using Superscript II (Life Technologies) and an oligo dT primer. Genomic DNA for wild-type versions of cho, ma, and mah and cDNA from the CG12207 transcript A were amplified by PCR and TOPO-TA cloned (Life Technologies). Each gene’s DNA/cDNA was subcloned into the pUAST vector (Drosophila Genomic Resource Center) in order to use the GAL4/UAS technique (Brand and Perrimon 1993; Duffy 2002). Clones were sequenced to verify that they had the wild-type sequence. The constructs were isolated with Plasmid Midi Prep kits (Qiagen). Injections of the pUAST clones to produce transgenic flies were performed by Rainbow Transgenic Flies.

Fly stocks and crosses

Fly stocks were maintained at 25° on Instant Drosophila Medium (Carolina Biological). Jim Kennison provided the EMS-induced redK1 stock and its OreR progenitor. Other stocks were obtained from the Bloomington and Exelixis Stock Collections (Table 1). Deletions were made using the Flp-FRT methods described by Parks (Parks et al. 2004). The chromosome sequence coordinates of specific existing deletions and deletions that were made are shown in Supplemental Material, Table S1. Recombinants were chosen based on their eye color. PCR was used to verify the deletions.

Table 1. Stocks used for locating eye color mutants.

| cho Mapping | All Autosomal Mapping | mahogany Mapping, cont’d. |

|---|---|---|

| P{XP}XPG-L Exelixis Stock Collection | P{ry+t7.2=hsFLP}1, y1 w1118; DrMio/TM3 ry* Sb1 | w1118;Df(3R)P{XP}CG31121d06890 to PBac{WH}f01730/TM6B, Tb Constructed by authors |

| w1118/Binsinscy | w1118; wg Sp-1/CyO; sensLy-1/TM6B, Tb1 | |

| w1118; MKRS, P{ry+t7.2 = hsFLP}86E/TM6B, Tb1 | red Mapping | |

| w1118/FM7c | maroon Mapping | w1118; Df(3R)Exel7321/TM6B, Tb1 |

| y2 cho2 flw1 | ma1 fl1 | w1118; Df(3R)Exel6267, P{w+mC = XP-U}Exel6267/TM6B, Tb1 |

| Df(1)10-70d, cho1 sn3/FM6 | w1118; Df(3R)BSC507/TM6C, Sb1 cu1 | w1118; PBac{ w+mC = RB}su(Hw)e04061/TM6B, Tb1 |

| Df(1)ED6716 w1118/FM7h | w1118; PBac{RB}Aats-trpe00999/TM6B Exelixis Stock Collection | w1118; P{XP}trxd08983/TM6B, Tb1 |

| w1118 P+PBac{XP3.WH3}BSC877/FM7h/Dp(2;Y)G P{hs-hid}Y | w1118; P{XP}d00816/TM6B Exelixis Stock Collection | w1118; Df(3R)P{XP}trxd08983 to PBac{RB}su(Hw)e04061/TM6B, Tb1 Constructed by authors |

| Df(1)BSC834 w1118/Binsinscy | w1118; Df(3R)Exel9036, PBac{WH}Exel9036/TM6B, Tb1 | |

| w1118; P{XP}d03180 Exelixis Stock Collection | w1118;Df(3R)ED5339, P{3′.RS5+3.3′}ED5339/TM6C, cu1 Sb1 | |

| w1118; PBac{RB}VhaAC39-1e04316 Exelixis Stock Collection | w1118;Df(3R) PBac{RB}Aats-TrpRSe00999 to P{XP}d00816/TM6B, Tb1 Constructed by authors | Additional Stocks for Rescue Crosses |

| w1118; P{w+mC = XP}yind02176 | w*; P{w+mc GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 | |

| P{XP}ecd00965 Exelixis Stock Collection | mahogany Mapping | w*;Cy/P{w+mc GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 Constructed by authors |

| PBac{WH}f06086 Exelixis Stock Collection | mah1 | w*; KrIf-1/CyO |

| w1118;Df(1) P{XP}ecd00965 Exelixis Stock Collection | w1118; PBac{WH}f01730/TM6B Exelixis Stock Collection | w*; KrIf-1/CyO; Df(3L)Ly, sensLy-1/TM6C, Sb1 Tb1 |

| PBac{WH}f06086 Exelixis Stock Collection | w1118; P{w+mc = XP}CG31121d06890/TM6B | w1118; KrIf-1/CyO; TM3, Sb1/D1 |

| w1118;Df(1) P{XP}ecd00965 to PBac{WH}f06086/FM7h Constructed by authors | w1118; Df(3R)BSC494/TM6C, Sb1 cu1 | w*; KrIf-1/CyO; CxD/TM6C, Sb1 Tb1 |

| w1118 PBac{RB}VhaAC39-1e04316 to P{XP}yind02176/FM7h Constructed by authors | w1118; Df(3R)Exel6200, P{XP-U}Exel6200/TM6B, Tb1 | w*; KrIf-1/CyO; TM3, Ser1/D1 |

| w1118; Df(1)P{XP}d03180 to PBac{RB}VhaAC39-1e04316/FM7h Constructed by authors | w1118; Df(3R)BSC318/TM6C, Sb1 cu1 | w1118; TM3, Sb1/CxD |

Unless otherwise noted, the stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

Deletion mapping crosses were made between each deletion stock (Table 2) and its corresponding homozygous mutant stock. Rescue crosses required that eye color phenotypes be evaluated in w+ flies. The GAL4/UAS system was used (Brand and Perrimon 1993; Duffy 2002). The driver employed for eye specific expression was Gal4-ninaE.GMR12. Stocks with balancers were used to produce w+; Cy/P{GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 homozygous mutant stocks for ma, mah, and red. These flies were crossed at 27° with the Cy/pUAST transgene stocks that were also homozygous for the appropriate third chromosome mutant allele and the phenotype was assayed in the F1s. For the X-linked cho gene, w+cho/w+cho; Cy/P{GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 females were crossed with wY; Cy/pUAST-cho transgene stock flies and the phenotype was evaluated in the male F1. Rescue was assayed for at least three independent transgene lines for each gene.

Table 2. Existing deletions or transposable elements used to produce deletions.

| Gene Deletion or Transposable Elements | Complements Mutant |

|---|---|

| chocolate | |

| P{XP}d03180 and PBac{RB}VhaAC39-1e04316 | Yes |

| PBac{RB}VhaAC39-1e04316 and P{XP}yind02176 | Yes |

| P{XP}ecd00965 and PBac{WH}f06086 | No |

| Df(1)BSC834 | Yes |

| Df(1)BSC877 | Yes |

| Df(1)ED6716 | No |

| maroon | |

| Df(3R)ED5339 | No |

| Df(3R)Exel9036 | Yes |

| Df(3R)BSC507 | No |

| mahogany | |

| Df(3R)BSC318 | No |

| Df(3R)Exel6200 | Yes |

| Df(3R)BSC494 | Yes |

| P{XP}CG31121d06890 and PBac{WH}f01730 | Yes |

| red Malpighian tubules | |

| Df(3R)Exel6267 | No |

| Df(3R)Exel7321 | Yes |

| P{XP}trxd08983 and PBac{RB}su(Hw)e04061 | No |

Data from complementation experiments are given for each deletion.

Photomicroscopy

Flies were photographed using a Leica DFC425 digital camera mounted on a Leica M205A stereomicroscope. A series of 15–70 images were taken at different focal planes with the software package Leica Application Suite version 3.0 (Leica Microsystems, Switzerland) and assembled using the software Helicon Focus 6 (Helicon Soft, Ukraine).

Sequence analysis

Sequencing was performed by the DNA Analysis Facility on Science Hill at Yale University, the Biological Sciences Sequencing Facility at the George Washington University, and Macrogen USA. Primers for cloning and sequencing are listed in Table S2. Sequences were compiled using Sequencher (Gene Codes). Predicted protein alignments were performed using T-Coffee or PSI-Coffee (Di Tommaso et al. 2011; Notredame et al. 2000) or PRALINE. PSI-Coffee alignment figures were produced using Boxshade (Source Forge) and PRALINE (Simossis and Heringa 2003; Simossis et al. 2005).

Data availability

Sequences of mutant alleles have been deposited in Genbank (accession nos. KU665627 – cho1, KU682283 – ma1, KU682282 – mah1, red KU711835 - red1 and red KU711836 - redK1). Other gene sequences are available by request. Aligned nucleotide sequences for the red mutants and OreR are in Figure S1. Table S2 lists the primers used in cloning and sequencing. Nucleotide changes in cho, ma, and mah are in Table S3. The identifiers for all proteins used in alignments are given in Table S4. The distribution of nucleotide substitutions in the two red stocks and OreR are shown in Table S5.

Results

cho codes for a subunit of vesicular ATPase

cho is an X-linked recessive eye color mutation that is also associated with brown pigmentation in the Malpighian tubules. It was originally described by Sturtevant (Lindsley and Zimm 1968; Sturtevant 1955). Both the amounts of ommochromes and pteridines present in cho eyes are decreased compared to wild type (Ferre et al. 1986; Reaume et al. 1991). The cytological position of cho is 3F1–3F4 and Sturtevant placed it close to echinus (ec). Three overlapping deficiencies, Df(1)BSC834, Df(1)ED6716, and Df(1)BSC877, which together removed regions around and including ec, were used for the first deletion mapping (Table 2). Only heterozygotes for cho and Df(1)ED6716 showed the cho phenotype, indicating that cho was in the region removed exclusively by Df(1)ED 6716 (Table 2). Genomic deficiencies were made using the Flp-FRT method (Parks et al. 2004). Deletion mapping with these identified a 47.8-Kbp region that contained the cho gene. Within it were three candidate genes: VhaAC39-1, a subunit of vacuolar ATPase; CG42541, a member of the Ras GTPase family; and CG15239, which has an unknown function (Table 2).

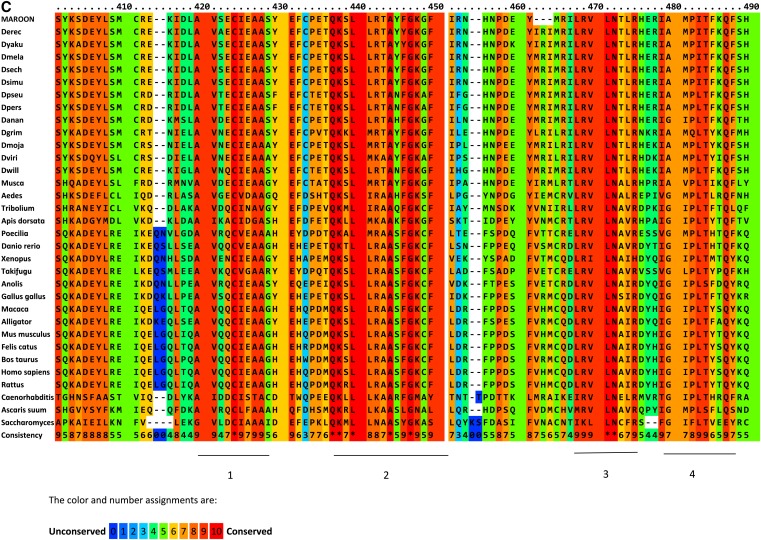

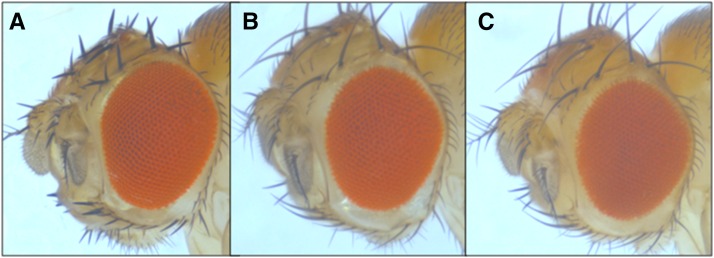

Each of these genes was amplified from cho DNA and sequenced. The coding regions of CG15239 and CG42541 did not contain any nonsynonymous sequence changes in the cho mutant flies. The coding region of VhaAC39-1 had a change from guanine to thymine at position X:3,882,405 that resulted in a nonsynonymous change, W330L, in the deduced protein sequence (Table 3 and Table S3). The UAS-VhaAC39-1 transgene (carried on chromosome 2) and the Gal4-ninaE.GMR12 driver were used to fully rescue cho/cho stocks (Figure 1). The residue at position 330 is highly conserved. Alignments of predicted orthologs from insects, other invertebrates, including yeast and vertebrates all showed a tryptophan at their corresponding positions (Figure 2). The conservation and phenotype change caused by cho mutant alleles both show the importance of this tryptophan in protein function.

Table 3. Nonsynonymous differences, deletions, and insertions between the Drosophila melanogaster genome sequence and mutant alleles of maroon, chocolate, mahogany, and red Malpighian tubules.

| Position | DNA Change | Nonsynonymous Changes |

|---|---|---|

| X | VhaAC39-1-chocolate | |

| X:3,882,405 | G > T | W330L |

| 3R | Vps16A-maroon | |

| 9267133 | G > A | M4I |

| 9267260 | G > A | A24T |

| 9268607–9268615 | Deletion | Deletion 422-I M R-424 |

| 9269662 | A > T | E712D |

| 3R | CG13646-mahogany | |

| 24949138 | roo insert | |

| 24949334 | T > C | I460Ta |

| 3R | CG12207-red | |

| red1 | ||

| 14300442 | A > C | N67Hb |

| redK1 | ||

| 14298973 | G > A | G51Sb |

This part of the exon may not be translated when the roo LTR is present.

The amino acid positions listed are for isoforms PA, PD, and PE. In isoforms PB, PF, and PG, the positions are N90H for red1 and G74S for redK1.

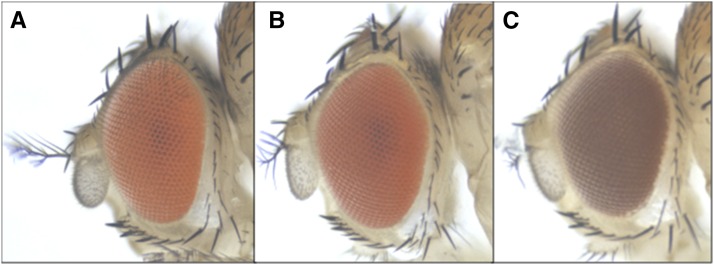

Figure 1.

The VhaAC39-1 gene complements the chocolate gene. (A) Wild-type genotype and phenotype. (B) cho/Y with transgene showing the wild-type phenotype. The transgenic male is hemizygous for the mutant allele and carries the Gal4 driver from w*; P{GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 and one copy of the VhaAC39-1 transgene. (C) cho/Y showing the mutant phenotype.

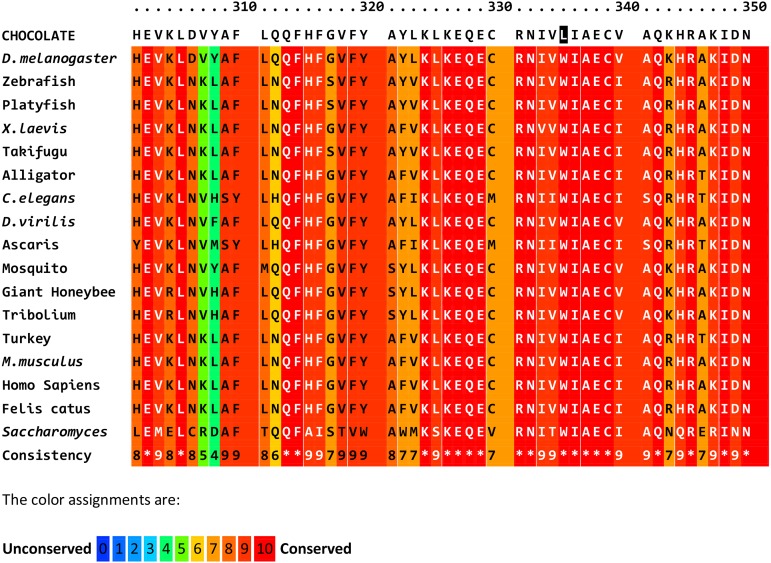

Figure 2.

Alignment of predicted partial protein sequences for CHOCOLATE orthologs in insects, fish, reptiles, birds, mammals, and yeast. Multiple sequence alignment, conservation scoring, and coloring were performed by PRALINE. 0 is the least conserved alignment position, increasing to 10 for the most conserved alignment position. Asterisks in the consistency sequence indicate identity in all sequences. The CHO sequence is not included in the consistency rating. The predicted CHO sequence for the region surrounding the missense mutation (shaded) is in the first line. The orthologous sequences were obtained for some vertebrates and yeast. The whole protein is highly conserved and the tryptophan at position 335 is constant except for the CHO sequence which has leucine. Species, gene, and protein identifiers are in Table S4.

ma codes for a component of the HOPS complex, Vps16A

The ma allele is recessive and homozygotes have darker eyes than normal and yellow Malpighian tubules (Bridges 1918). Homozygotes also have decreased amounts of both pteridines and ommochromes (Nolte 1955). Deletion mapping results (Table 2) indicated that the region in which ma resides contains Vps16A, a gene involved in endosomal transport and eye pigment (Pulipparacharuvil et al. 2005); Aats-trp, a tRNA synthase (Seshaiah and Andrew 1999); CG8861, a predicted Lymphocyte Antigen super family 6 gene (Hijazi et al. 2009); HP1E, a member of the heterochromatin protein 1 family (Vermaak et al. 2005); and CG45050, a gene coding for a protein with Zinc finger domains (dos Santos et al. 2015).

The Vps16A gene was sequenced in ma flies because of its role in the HOPS complex. The DNA sequence has 10 nucleotide substitutions and a 9-bp deletion (Table S3). The protein has three missense substitutions and a deletion of three contiguous amino acids (Table 3). Homozygous mutant ma1 flies had a near wild-type phenotype when rescued by the UAS-Vps16A transgene driven by the Gal4-ninaE.GMR12 driver (Figure 3).

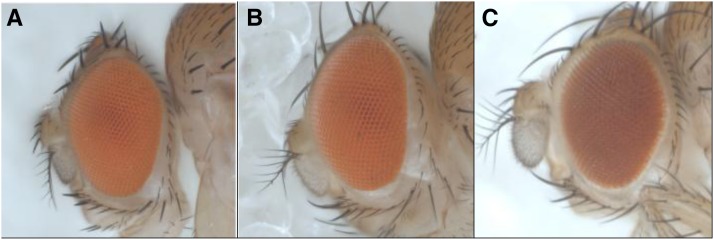

Figure 3.

The Vps16A wild-type allele complements the maroon mutation. (A) Wild-type genotype and phenotype. (B) ma/ma mutant genotype plus the Vps16A transgene and P{GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 driver produces a wild-type phenotype. (C) ma/ma mutant genotype and phenotype.

The cause of impaired protein function is unclear. The first two substitutions (M4I and A24T) are not conservative and are found in variable regions in the protein (Figure 4A). The aspartic acid of the E712D substitution is found in the corresponding site in the majority of Drosophila species and in many other species (Figure 4B). The deletion sequence is in a region with moderately conservative changes between amino acids and it does lie between two regions that are conserved from fly to man (Figure 4C). The spacing between these conserved regions is invariant among the investigated species, with the exception of Caenorhabditis elegans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

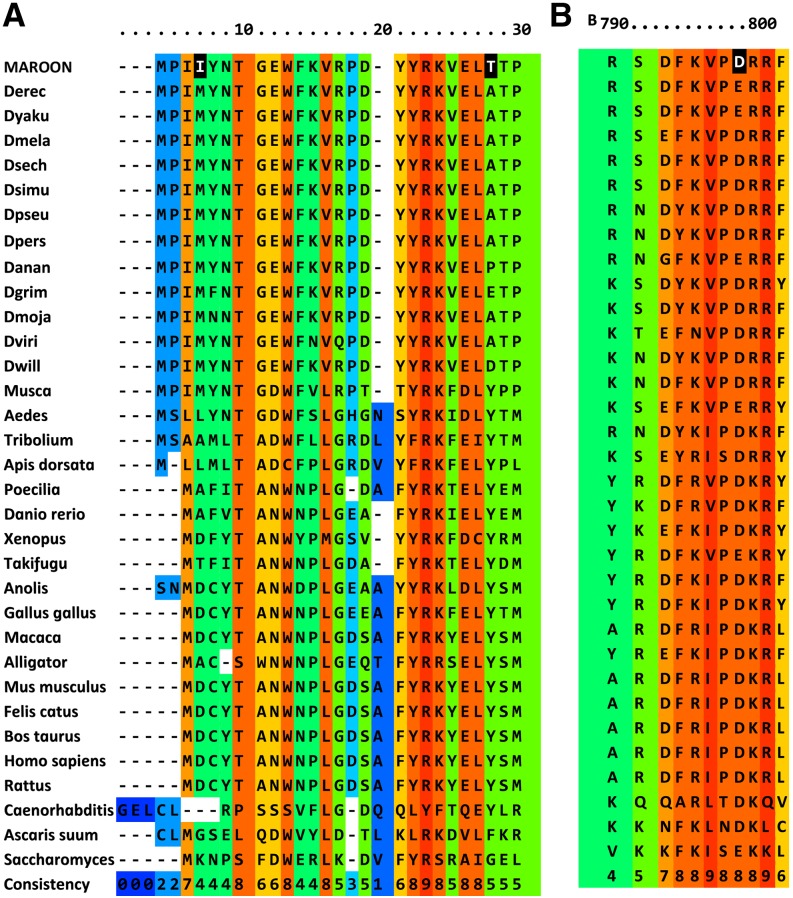

Figure 4.

A PRALINE alignment of regions of the predicted MAROON protein which have changed compared to the D. melanogaster sequence. Alignment, conservation scoring and coloring was performed by PRALINE. The ma sequence is not included in the consistency rating. 0 is the least conserved alignment position, increasing to 10 for the most conserved alignment position. Asterisks in the consistency line indicate identity for all sequences. Species, gene and protein identifiers are in Table S4. MA amino acid changes are shaded black in the first line for each alignment. (A) The first two amino acid changes are in regions with low conservation. Note, however, that the residue at position 7 is not found in any other species. The M at that site is conserved in all Drosophila. The A to T change at position 28 is also not found in other species. The position is variable in insects, but vertebrates usually have a Y. (B) The E to D change at position 797 is in a moderately conserved area. D is found in many organisms at this site. (C) The deletion of three amino acids in the MA protein shown in line one at positions 461–463 lies between two sets of conserved sequences, 1, 2, 3, and 4 (underlined). The distance between the 2 and 3 regions is conserved in all species shown except C. elegans and S. cerevisiae.

mah contains domains found in amino acid transporters and permeases

mah is a recessive eye color mutant on the right arm of the third chromosome with a recombination map position of 88. It was discovered by Beadle (Lindsley and Zimm 1968). Homozygotes have decreases in ommochrome pigments and six of 10 pteridine pigments (Ferre et al. 1986).

Deficiency mapping showed that the possible mah genes were Nmnat and CG13646 in the 96B cytological region (Table 2). Nmnat is Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase and is involved in NAD synthesis and photoreceptor cell maintenance (Zhai et al. 2006). The CG13646 gene contains transmembrane domains and an amino acid transporter domain (dos Santos et al. 2015; Romero-Calderon et al. 2007). Along with functions that could relate to pigmentation, both genes had expression patterns consistent with an eye color gene (dos Santos et al. 2015) Nmnat and CG13646 were sequenced using DNA from the mah strain.

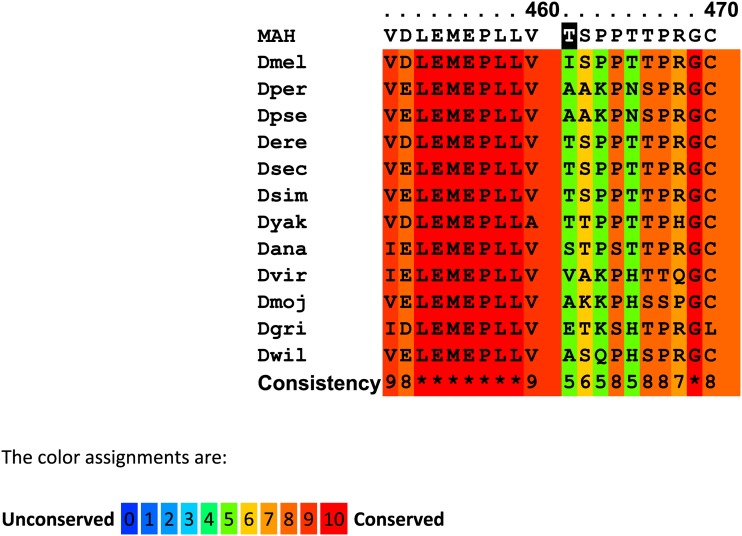

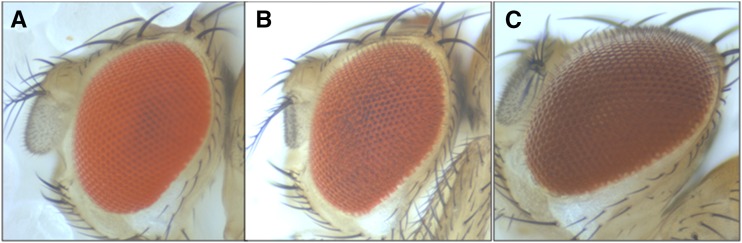

The Nmnat allele sequence matched the Flybase sequence in its coding region and introns. The CG13646 gene had 10 single base pair substitutions and an insertion of 433 bp, including a duplication of a 5-bp insert sequence in its fifth exon (Table S3). The additional DNA is a solo insert of a roo LTR (Meyerowitz and Hogness 1982; Scherer et al. 1982). For CG13646, only one substitution mutation was nonsynonymous, a T > C at 3R:24949334 causing an I460T change if that position were transcribed and translated (Table 3). The UAS-CG13646 transgene under the control of the eye-specific GAL4-ninaE.GMR12 driver rescued mah/mah flies (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The CG13646 gene rescues the mahogany gene. (A) Wild-type genotype and phenotype. (B) mah/mah mutant genotype and CG13646 transgene under the control of the Gal4 driver P{GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 shows the wild-type phenotype. (C) mah/mah genotype shows the mutant phenotype.

The insertion would be expected to cause production of a truncated inactive protein product. If the translation of the last exon proceeds through the insert, there will be an early termination signal adding three amino acids coded for by roo and deleting 130 amino acids. Comparing the CG13646 orthologous proteins in 12 Drosophila species shows the threonine substitution is at the corresponding position in D. melanogaster’s close relatives, D. simulans, D. erecta, and D. sechellia, implying that this substitution would be functional if the mah transcript were properly spliced and translated (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

PRALINE alignment and consistency scores of predicted residues 450–470 with the MAHOGANY protein sequence in Drosophila species. 0 is the least conserved alignment position, increasing to 10 for the most conserved alignment position. Asterisks in the consistency rating indicate identity for all. The MAH sequence is not included in the consistency rating. The change in sequence in the MAH protein is shaded black in the first line. A number of other species, D. erecta, D. simulans, D. yakuba, and D. sechellia, have a T at the same position as mahogany. Species, gene, and protein identifiers are in Table S4.

Unlike the genes discussed above, mah’s protein product shows very high sequence similarity to predicted orthologous proteins in other Drosophila species but markedly decreased similarity to orthologs in other insects (Figure S1A). It shows relatively low similarity to vertebrate proteins. While Psi Blast searches with the CG13646 protein found sequence similarity with human and mouse GABA vesicular transporters, another D. melanogaster predicted protein, VGAT, shows greater sequence similarity and is the presumptive ortholog of the mammalian protein (Figure S1B).

red is coded for by a gene with a LysM domain and an unknown function

The red gene’s phenotype is caused by a recessive allele producing flies with dark red-brown eyes and rusty red-colored Malpighian tubules. This gene is located on the third chromosome at cytogenetic position 88B1-B2 and was discovered by Muller (Lindsley and Zimm, 1968). red flies show decreases in both ommochromes and some pteridines (dos Santos et al. 2015; Ferre et al. 1986).

Deletion mapping revealed red was coded for by one of three genes, CG12207, CG3259, or su(Hw) (Table 2). The su(Hw) gene codes for a DNA-binding protein and mutants have well described phenotypes that do not involve the eyes. The CG3259 gene is involved in microtubule binding and the CG12207 gene codes for a product of unknown function. The exons of CG12207 and the complete CG3259 gene were sequenced in three stocks, red1, redK1, and the OreR stock that is the redK1 progenitor.

Compared to the Genbank reference sequence for CG12207 and CG3259, the three stocks had substitutions at 34 sites for CG12207. The most telling comparison is redK1 vs. its progenitor. The redK1 stock contained four changes that were absent from OreR (Table 4 and Table S5). One was a missense change producing G51S in the LysM domain of protein isoform A (Table 3). The others were two synonymous changes and one substitution in an untranslated region. The red1 stock had 26 substitutions compared to the Genbank reference sequence and 12 compared to OreR (Table S5). It carried only one missense mutation, A to C, that produced an N67H change in the LysM domain of the protein isoform A (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 4. Types and numbers of substitutions in red1, redK1, and OreR stocks for CG12207 and CG3259 compared with the Genbank reference sequences for CG12207 and CG3259.

The CG3259 sequences from the three stocks had 25 substitutions compared to the Genbank reference sequence (Table 4). The redK1 stock had two changes in sequence that were missing in OreR, one synonymous and one in an untranslated region. These two stocks shared the same predicted protein sequence with four amino acids that varied from the Genbank reference protein sequence. The red1 flies shared the replacements coding for the four amino acid substitutions and had four more missense changes, resulting in a substitution of eight amino acids compared with the Genbank reference sequence (Table 4 and Table S5).

The nucleotide sequences for both genes from OreR and the two red stocks were compared to the Drosophila Genomic Reference Panel, a database showing nucleotide polymorphisms in a panel of 200 inbred lines of D. melanogaster (Mackay et al. 2012). All of the CG12207 replacements were found in the panel, except for each missense change in red1 and redK1 (Figure S2). All of the CG3259 changes also were found in the panel, except one shared by OreR and redK1. That substitution resided in an intron. When the CG3259 predicted protein sequences were compared in 11 Drosophila species, most amino acid changes were found in other species and were at variable sites in the protein sequence (data not shown).

Given the presence of unique amino acid changes in red CG12207 sequences, the UAS-CG12207 cDNA-A construct was chosen for a rescue experiment. It was able to partially or fully complement red flies when expressed with the GAL4-ninaE.GMR12 driver, demonstrating that CG12207 is the red gene (Figure 7). These data are consistent with the Johnson Laboratory analysis comparing the reference gene sequence to an earlier restriction map that included the red gene (Breen and Harte 1991) and the predictions of Cook and Cook found in Flybase (FBrf0225865).

Figure 7.

CG 12207 partially complements the red/red genotype. (A) Wild-type genotype and phenotype. (B) red/red genotype and partially wild-type phenotype with a CG12207 transgene and the P{GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 driver present. (C) Red mutant phenotype in red/red fly.

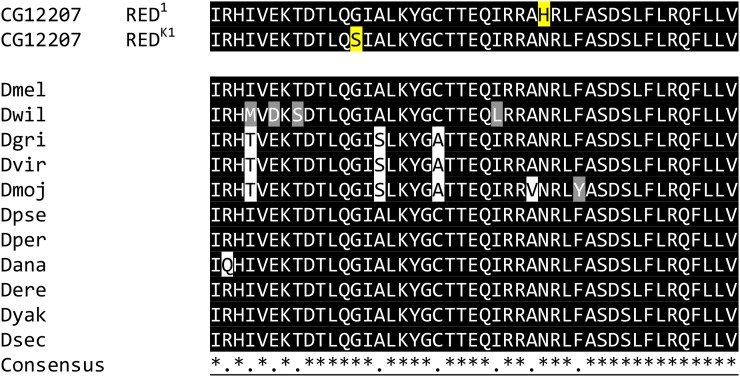

The single domain identified in CG12207 is the LysM domain and it is the site of both red1 and redK1 missense mutations. It is present in all six transcripts of the gene, but the function(s) of the predicted proteins are unknown. The domain in CG12207 is highly conserved in predicted Drosophila orthologs (Figure 8). Further, the LysM domain is present in Eubacteria, plants, animals, and fungi.

Figure 8.

Alignment of LysM Domains in CG12207 orthologs in 11 Drosophila species and in RED1 and REDK1. The multiple sequence alignment was performed by PSI-Coffee and the illustration made using BoxShade. RED1 and REDK1 proteins were not included in the consensus calculation. Residues that match the consensus sequence are shaded black. Gray regions represent changes to similar amino acids. White regions indicate substitutions to less similar amino acids. Asterisks in the consensus denote identity in all sequences. The red1 allele (top line) codes for a substitution of G to S and redK1 (second line) produces an N to H substitution (both marked in yellow). In wild-type D. melanogaster and the other 10 species, these sites are conserved. Species, gene, and protein identifiers are in Table S4.

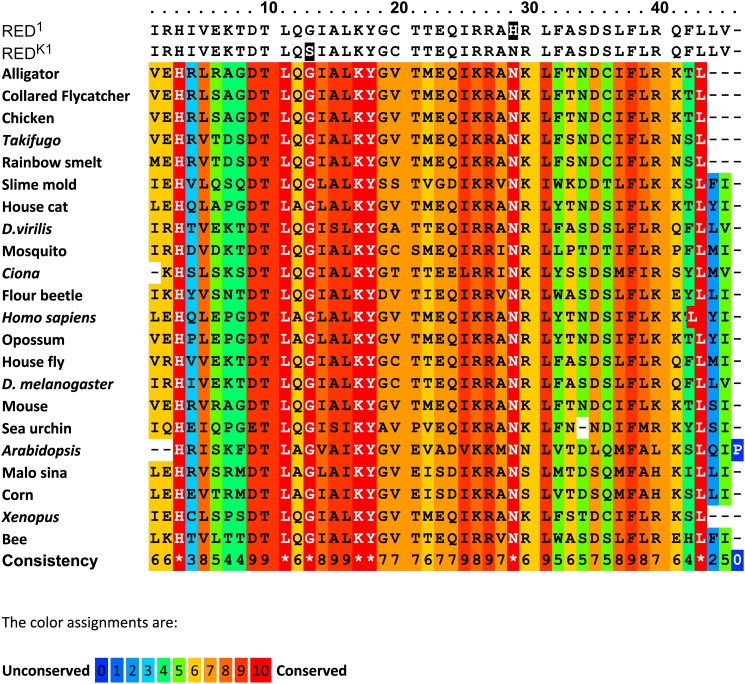

Examples of LysM domains similar in sequence to that found in red were identified b querying NCBI Blast using the CG12207 LysM domain. These were aligned using T-Coffee (Notredame et al. 2000) and the G and N sites mutated in red alleles were perfectly conserved from rice to man (Figure 9). In addition, the N site appears conserved in other LysM motifs (Laroche et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2009). Glycine is often found in tight turns in proteins and even a seemingly neutral change to serine may influence protein conformation (Betts and Russell 2003). While changes of asparagines to histidines are found in proteins, the exclusive presence of asparagines in the LysM domains examined supports the idea that the amino acid is important for normal protein function.

Figure 9.

PRALINE alignment of predicted LysM domains from a variety of animals and plants. Asterisks in the consistency line indicate identity for all sequences. The RED1and REDK1 protein sequences are not included in the consistency rating. Sequences were chosen by their similarity to the CG12207 LysM domain sequence. The sites that were mutated in RED1 and REDK1 (shaded black) are normally completely conserved from rice and corn to man. All species, protein, and gene identifiers are in Table S4.

Discussion

The cho gene is essential and functions to acidify cellular compartments

The cho gene, VhaAC39-1, codes for Vacuolar H+ ATPase AC39 subunit d. The V-ATPase is found in all eukaryotes and is present in lysosomes, endosomes, and clathrin-coated vesicles. The two sectors of V-ATPases are V1 and V0, each of which contains multiple proteins. V1 is found outside the organelle/vesicle and interacts with ATP, ADP, and phosphate. V0 is found in the plasma membrane and transports H+ into the compartment (Beyenbach and Wieczorek 2006; Marshansky et al. 2014). Subunit d of the V0 complex may function in connecting the V1 complex to the V0 complex through interactions with V1 protein subunits (Allan et al. 2005). Intracellular V-ATPases play important roles in trafficking, such as separation of ligands and receptors in endosomes, and degradation in lysosomes (Wang et al. 2012b). Acidification regulates and mediates the trafficking of cellular receptors and ligands, such as Notch and Wnt.

The mutation in the cho gene is a tryptophan-to-leucine mutation. Tryptophan is the rarest amino acid in eukaryotic proteins, while leucine is the most common (Gaur 2014). Owegi et al. (2006) investigated the effects of a change of the corresponding tryptophan to alanine (W325A) in yeast. Loss of the tryptophan decreased the assembly of the V0V1 active enzymes, ATPase activity, and proton transport to about 10% of the normal rate.

The cho/VhaAC39-1 gene has several other characteristics that are consistent with its role as an important component of trafficking. RNAi experiments demonstrated that its knockdown in D. melanogaster resulted in complete lethality (Mummery-Widmer et al. 2009). Its ortholog in mice is also essential (Miura et al. 2003). The viability of cho flies indicates a malfunction of VHAAC39-1 that results in a decrease in activity vs. a loss of protein, as seen in knockdowns. Further, cho is ubiquitously expressed (Chintapalli et al. 2007; Hammonds et al. 2013; Tomancak et al. 2002, 2007). Studies of cho’s effects in all parts of the body could reveal gene interactions between VHAAC39-1 and proteins of other mutant genes participating in the same pathways.

The ma gene is essential and participates in the HOPS complex used in trafficking, endosome maturation, and fusion with lysosomes

The ma/Vps16A gene product is one of four core proteins in the HOPS complex in metazoans. This role has been confirmed in flies. Pulipparacharuvil et al. (2005) have shown that VPS16A complexes with DOR and CAR proteins. Takáts et al. (2014) demonstrated that the HOPS complex is required for fusion of autophagosomes with the lysosomes. Disruption of the HOPS complex also resulted in increased metastasis and growth of tumors in Drosophila (Chi et al. 2010). Recent work in humans has shown that VPS 16 is required to recruit VPS 33A to the HOPS complex. The lack of either of these proteins prevented the fusion of lysosomes with endosomes or autophagosomes (Wartosch et al. 2015).

In D. melanogaster, a VPS16A knockdown in the eye resulted in a change in eye color and retinal degeneration due to defects in lysosomal delivery and the formation of pigment granules. An organism-wide knockdown of VPS16A caused death (Pulipparacharuvil et al. 2005). Like cho, ma is an essential gene and the ma allele produces a partially functional protein. In addition, ma RNA is maternally deposited and the gene is expressed widely in larvae and adults (Chintapalli et al. 2007; Hammonds et al. 2013; Tomancak et al. 2002, 2007). The study of ma mutant flies for other possible interacting genes would produce an in vivo system capable of revealing new gene networks and their sites of action.

The red gene’s product has an unknown function and a LysM domain, which is part of a superfamily found in bacteria, plants, and animals

The role of the red/CG12207 gene product is unknown. The fact that the two red mutant alleles had missense substitutions in their LysM domains indicates that the domain is important for the protein’s function. In animals, the LysM domain is found either by itself or in combination with TLDC motifs found in putative membrane-bound proteins (Zhang et al. 2009). The RED protein has a single LysM domain near the N terminal end of the protein. It lacks the transmembrane region found in most LysM proteins of bacteria, fungi, and plants, and, presumably, remains inside cells vs. on their surfaces.

In plants, some LysM proteins function in immune responses. Evidence in animals is mixed. Shi et al. (2013) reported that a red swamp crayfish gene carrying the LysM domain, PcLysM, shows increases in its mRNA accumulation when the crayfish are challenged with bacteria. Knockdown of PcLysM mRNA in the animals is accompanied by a decrease in the antimicrobial response. Laroche et al. (2013) reviewed two microarray studies that measured Zebrafish mRNA levels in response to challenges with bacteria. The studies failed to detect a change in the quantities of LysM domain containing mRNAs (Laroche et al. 2013). Four D. melanogaster genes contain a LysM domain, CG15471, CG17985, and mustard (mtd). Only mtd also contains a TLDC domain. It is the only Drosophila LysM-containing gene that has been investigated with respect to innate immunity. mtd has a mutant allele that increases fly tolerance to Vibrio infection and decreases the transcription of at least one antimicrobial peptide involved in innate immunity. However, the mtd transcript that is most influential in changing sensitivity lacks the LysM domain and carries a TLDC domain (Wang et al. 2012b).

The CG12207 protein has two different N terminal sequences. Neither of these appears to be a signal sequence (Petersen et al. 2011). Like the cho and ma genes, CG12207 is maternally deposited and is ubiquitously expressed. Its highest expression is observed in Malpighian tubules (Chintapalli et al. 2007; Hammonds et al. 2013; Tomancak et al. 2002, 2007). Two of the five gene interactions listed in the Flybase Interactions Browser for CG12207 are with proteins related to trafficking: CG16817 influences Golgi organization and ZnT63C transports Zn (Guruharsha et al. 2011). The Golgi apparatus contributes cargo to the endosomes and lysosomes that may be involved in vesicular trafficking. ZnT63C moves Zn out of the cytoplasm either into intracellular compartments or outside the cell membrane (Kondylis et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2009). Another Zn transporter, Catsup, has been shown to disrupt trafficking of NOTCH, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor, and Drosophila Amyloid Precursor-Like proteins (Groth et al. 2013).

The MAH protein is predicted to be an amino acid transporter that is not essential

InterPro analysis of the MAH predicted protein identified 11 transmembrane helices and a conserved domain found in amino acid transporters (Mitchell et al. 2015). The NCBI Conserved Domain Database identified the domain in MAH as the Solute Carrier (SLC) families 5 and 6-like; solute binding domain. Two studies (Romero-Calderon et al. 2007; Thimgan et al. 2006) fail to place CG13646 into the D. melanogaster SLC6 protein group and Romero-Calderon et al. (2007) suggest that the protein may be an amino acid permease.

Unlike cho and ma, mah is not essential because the predicted protein in the mah/mah fly is a truncated, and probably inactive enzyme, yet these flies are viable. The expression of mah is limited, being ranked as present in the larval central nervous system, adult eye, Malpighian tubule, and testes (Chintapalli et al. 2007). Its time of highest expression is the white prepupal stage when eye pigmentation begins (Graveley et al. 2011).

Disruption of both types of pigments is a good criterion to identify genes involved in Drosophila vesicular trafficking

Four candidate genes were identified as possible granule group genes based on one characteristic, decreases in the amounts of both ommochromes and pteridines found in fly eyes. Of these, ma is the best example of such a gene since it is a member of the HOPS complex, like some previously identified granule group genes. The vesicular ATPase, cho, is also very important in vesicle maturation and function. The mah gene may well be important in transport to pigment granules given that it appears to be a membrane protein similar to other amino acid carriers. The red gene’s function and significance in transport are unknown.

cho and ma can be used to study the involvement of their products in a variety of processes when their proteins are expressed in vivo. These two genes are essential, but the mutants are visible and viable without partial RNAi knockdowns. Further, since the genes are ubiquitously expressed they could be tested in screens detecting changes in tissues and organs other than the eye. They can also be used in screens in which the tested genes are knocked down by RNAi. The use of mutants in whole organisms to understand the effects of genes and genetic interactions is very powerful.

Trafficking is a complex phenomenon in which many genes participate. A simple criterion allows the discovery of more Drosophila trafficking genes and more alleles of identified genes. There is a set of unmapped, eye color mutants that have had their relative pteridine and ommochrome levels tested that could be identified using the techniques of deletion mapping and sequencing. More genes/alleles could be discovered whose use would contribute to understanding vesicular trafficking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Courtney Smith for many helpful discussions and advice. Ligia Rosario Benavides, Thiago da Silva Moreira, and Robert J. Kallal of the Gustavo Hormiga laboratory assisted us with photomicroscopy. Jim Kennison kindly provided the redK1 strain and the Oregon R strain from which it was derived. T.M., A.W., and J.N. were supported by the Undergraduate Research Program for the Biological Sciences Department. The work was supported by intramural funding through The George Washington University Facilitating Fund grants, Columbian College Facilitating Funds and Dilthey grants. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online at www.g3journal.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/g3.116.032508/-/DC1.

Communicating editor: C. Gonzalez

Literature Cited

- Allan A. K., Du J., Davies S. A., Dow J. A., 2005. Genome-wide survey of V-ATPase genes in Drosophila reveals a conserved renal phenotype for lethal alleles. Physiol. Genomics 22: 128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie D. L., Chovnick A., 1971. Studies on the genetic control of tryptophan pyrrolase in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Gen. Genet. 112: 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besteiro S., Tonn D., Tetley L., Coombs G. H., Mottram J. C., 2008. The AP3 adaptor is involved in the transport of membrane proteins to acidocalcisomes of Leishmania. J. Cell Sci. 121: 561–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts M. J., Russell R. B., 2003. Amino acid properties and consequences of subsitutions, in Bioinformatics for Geneticists, edited by Barnes M. R. M. R., Gray I. C. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester. [Google Scholar]

- Beyenbach K. W., Wieczorek H., 2006. The V-type H+ ATPase: molecular structure and function, physiological roles and regulation. J. Exp. Biol. 209: 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino J. S., 2004. Insights into the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles from the study of the Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1038: 103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino J. S., 2014. Vesicular transport earns a nobel. Trends Cell Biol. 24: 3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. H., Perrimon N., 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen T. R., Harte P. J., 1991. Molecular characterization of the trithorax gene, a positive regulator of homeotic gene expression in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 35: 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges C. J., 1918. Maroon–a recurrent mutation in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 4: 316–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. C., Scoggin S., Wang D., Cherry S., Dembo T., et al. , 2011. Systematic discovery of rab GTPases with synaptic functions in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 21: 1704–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheli V. T., Daniels R. W., Godoy R., Hoyle D. J., Kandachar V., et al. , 2010. Genetic modifiers of abnormal organelle biogenesis in a Drosophila model of BLOC-1 deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19: 861–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi C., Zhu H., Han M., Zhuang Y., Wu X., et al. , 2010. Disruption of lysosome function promotes tumor growth and metastasis in Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 21817–21823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli V. R., Wang J., Dow J. A., 2007. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 39: 715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles C. R., Odorizzi G., Payne G. S., Emr S. D., 1997. The AP-3 adaptor complex is essential for cargo-selective transport to the yeast vacuole. Cell 91: 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Angelica E. C., 2004. The building BLOC(k)s of lysosomes and related organelles. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16: 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Angelica E. C., Mullins C., Caplan S., Bonifacino J. S., 2000. Lysosome-related organelles. FASEB J. 14: 1265–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro S. M., Falcon-Perez J. M., Dell’Angelica E. C., 2004. Characterization of BLOC-2, a complex containing the Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome proteins HPS3, HPS5 and HPS6. Traffic 5: 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tommaso P., Moretti S., Xenarios I., Orobitg M., Montanyola A., et al. , 2011. T-coffee: a web server for the multiple sequence alignment of protein and RNA sequences using structural information and homology extension. Nucleic Acids Res. 39: W13–W17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos G., Schroeder A. J., Goodman J. L., Strelets V. B., Crosby M. A., et al. , 2015. FlyBase: introduction of the Drosophila melanogaster release 6 reference genome assembly and large-scale migration of genome annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: D690–D697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J. B., 2002. GAL4 system in Drosophila: a fly geneticist’s swiss army knife. Genesis 34: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon-Perez J. M., Romero-Calderon R., Brooks E. S., Krantz D. E., Dell’Angelica E. C., 2007. The Drosophila pigmentation gene pink (p) encodes a homologue of human Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome 5 (HPS5). Traffic 8: 154–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faundez V., Horng J. T., Kelly R. B., 1998. A function for the AP3 coat complex in synaptic vesicle formation from endosomes. Cell 93: 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre J., Silva F. J., Real M. D., Mensua J. L., 1986. Pigment patterns in mutants affecting the biosynthesis of pteridines and xanthommatin in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem. Genet. 24: 545–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaur R. K., 2014. Amino acid frequency distribution among eukaryotic proteins. IIOABJ 5: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gloor G. B., Preston C. R., Johnson-Schlitz D. M., Nassif N. A., Phillis R. W., et al. , 1993. Type I repressors of P element mobility. Genetics 135: 81–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M. L., Paro R., Gehring W. J., 1982. Molecular cloning of the white locus region of Drosophila melanogaster using a large transposable element. EMBO J. 1(1): 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley B. R., Brooks A. N., Carlson J. W., Duff M. O., Landolin J. M., et al. , 2011. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 471: 473–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth C., Sasamura T., Khanna M. R., Whitley M., Fortini M. E., 2013. Protein trafficking abnormalities in Drosophila tissues with impaired activity of the ZIP7 zinc transporter catsup. Development 140: 3018–3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruharsha K. G., Rual J. F., Zhai B., Mintseris J., Vaidya P., et al. , 2011. A protein complex network of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell 147: 690–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds A. S., Bristow C. A., Fisher W. W., Weiszmann R., Wu S., et al. , 2013. Spatial expression of transcription factors in Drosophila embryonic organ development. Genome Biol. 14: R140–2013–14–12-r140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijazi A., Masson W., Auge B., Waltzer L., Haenlin M., et al. , 2009. Boudin is required for septate junction organisation in Drosophila and codes for a diffusible protein of the Ly6 superfamily. Development 136: 2199–2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizing M., Helip-Wooley A., Westbroek W., Gunay-Aygun M., Gahl W. A., 2008. Disorders of lysosome-related organelle biogenesis: clinical and molecular genetics. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 9: 359–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutagalung A. H., Novick P. J., 2011. Role of rab GTPases in membrane traffic and cell physiology. Physiol. Rev. 91: 119–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent H. M., Evans P. R., Schafer I. B., Gray S. R., Sanderson C. M., et al. , 2012. Structural basis of the intracellular sorting of the SNARE VAMP7 by the AP3 adaptor complex. Dev. Cell 22: 979–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Suh H., Kim S., Kim K., Ahn C., et al. , 2006. Identification and characteristics of the structural gene for the Drosophila eye colour mutant sepia, encoding PDA synthase, a member of the omega class glutathione S-transferases. Biochem. J. 398: 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondylis V., Tang Y., Fuchs F., Boutros M., Rabouille C., 2011. Identification of ER proteins involved in the functional organisation of the early secretory pathway in Drosophila cells by a targeted RNAi screen. PLoS One 6: e17173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche F. J., Tulotta C., Lamers G. E., Meijer A. H., Yang P., et al. , 2013. The embryonic expression patterns of zebrafish genes encoding LysM-domains. Gene Expr. Patterns 13: 212–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Garrity A. G., Xu H., 2013. Regulation of membrane trafficking by signalling on endosomal and lysosomal membranes. J. Physiol. 591: 4389–4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley D. L., Zimm G. G., 1968. The Genome of Drosophila Melanogaster. Carnegie Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd V., Ramaswami M., Kramer H., 1998. Not just pretty eyes: Drosophila eye-colour mutations and lysosomal delivery. Trends Cell Biol. 8: 257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Plesken H., Treisman J. E., Edelman-Novemsky I., Ren M., 2004. Lightoid and claret: a rab GTPase and its putative guanine nucleotide exchange factor in biogenesis of Drosophila eye pigment granules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 11652–11657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay T. F., Richards S., Stone E. A., Barbadilla A., Ayroles J. F., et al. , 2012. The Drosophila melanogaster genetic reference panel. Nature 482: 173–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie S. M., Brooker M. R., Gill T. R., Cox G. B., Howells A. J., et al. , 1999. Mutations in the white gene of Drosophila melanogaster affecting ABC transporters that determine eye colouration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1419: 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshansky V., Rubinstein J. L., Gruber G., 2014. Eukaryotic V-ATPase: novel structural findings and functional insights. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837: 857–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz E. M., Hogness D. S., 1982. Molecular organization of a Drosophila puff site that responds to ecdysone. Cell 28: 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A., Chang H. Y., Daugherty L., Fraser M., Hunter S., et al. , 2015. The InterPro protein families database: the classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: D213–D221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura G. I., Froelick G. J., Marsh D. J., Stark K. L., Palmiter R. D., 2003. The d subunit of the vacuolar ATPase (Atp6d) is essential for embryonic development. Transgenic Res. 12: 131–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan T. H., 1910. Sex limited inheritance in Drosophila. Science 32: 120–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins C., Hartnell L. M., Wassarman D. A., Bonifacino J. S., 1999. Defective expression of the mu3 subunit of the AP-3 adaptor complex in the Drosophila pigmentation mutant carmine. Mol. Gen. Genet. 262: 401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins C., Hartnell L. M., Bonifacino J. S., 2000. Distinct requirements for the AP-3 adaptor complex in pigment granule and synaptic vesicle biogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263: 1003–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mummery-Widmer J. L., Yamazaki M., Stoeger T., Novatchkova M., Bhalerao S., et al. , 2009. Genome-wide analysis of Notch signalling in Drosophila by transgenic RNAi. Nature 458: 987–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson D. P., Brett C. L., Merz A. J., 2009. Vps-C complexes: gatekeepers of endolysosomal traffic. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21: 543–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte D. J., 1955. The eye pigmentary system of Drosophila VI. The pigments of the ruby and red groups of genes. J. Genet. 53: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C., Higgins D. G., Heringa J., 2000. T-coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302: 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi C. E., Moreira J. E., Dell’Angelica E. C., Poy G., Wassarman D. A., et al. , 1997. Altered expression of a novel adaptin leads to defective pigment granule biogenesis in the Drosophila eye color mutant garnet. EMBO J. 16: 4508–4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owegi M. A., Pappas D. L., Finch M. W., Jr, Bilbo S. A., Resendiz C. A., et al. , 2006. Identification of a domain in the V0 subunit d that is critical for coupling of the yeast vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 30001–30014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks A. L., Cook K. R., Belvin M., Dompe N. A., Fawcett R., et al. , 2004. Systematic generation of high-resolution deletion coverage of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Nat. Genet. 36: 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen T. N., Brunak S., von Heijne G., Nielsen H., 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8: 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulipparacharuvil S., Akbar M. A., Ray S., Sevrioukov E. A., Haberman A. S., et al. , 2005. Drosophila Vps16A is required for trafficking to lysosomes and biogenesis of pigment granules. J. Cell Sci. 118: 3663–3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M., Haberman A., Tracy C., Ray S., Kramer H., 2012. Drosophila mauve mutants reveal a role of LYST homologs late in the maturation of phagosomes and autophagosomes. Traffic 13: 1680–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaume A. G., Knecht D. A., Chovnick A., 1991. The rosy locus in Drosophila melanogaster: xanthine dehydrogenase and eye pigments. Genetics 129: 1099–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Calderon R., Shome R. M., Simon A. F., Daniels R. W., DiAntonio A., et al. , 2007. A screen for neurotransmitter transporters expressed in the visual system of Drosophila melanogaster identifies three novel genes. Dev. Neurobiol. 67: 550–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer G., Tschudi C., Perera J., Delius H., Pirrotta V., 1982. B104, a new dispersed repeated gene family in Drosophila melanogaster and its analogies with retroviruses. J. Mol. Biol. 157: 435–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles L. L., Voelker R. A., 1986. Molecular characterization of the Drosophila vermilion locus and its suppressible alleles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83: 404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles L. L., Ruth R. S., Pret A. M., Fridell R. A., Ali A. J., 1990. Structure and transcription of the Drosophila melanogaster vermilion gene and several mutant alleles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10: 1423–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda F. E., Burgess A., Heiligenstein X., Goudin N., Menager M. M., et al. , 2015. LYST controls the biogenesis of the endosomal compartment required for secretory lysosome function. Traffic 16: 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshaiah P., Andrew D. J., 1999. WRS-85D: a tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase expressed to high levels in the developing Drosophila salivary gland. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 1595–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X. Z., Zhou J., Lan J. F., Jia Y. P., Zhao X. F., et al. , 2013. A lysin motif (LysM)-containing protein functions in antibacterial responses of red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 40: 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simossis V. A., Heringa J., 2003. The PRALINE online server: optimising progressive multiple alignment on the web. Comput. Biol. Chem. 27: 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simossis V. A., Kleinjung J., Heringa J., 2005. Homology-extended sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 816–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanger J., Spang A., 2013. Tethering complexes in the endocytic pathway: CORVET and HOPS. FEBS J. 280: 2743–2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant A. H., 1955. New mutants report. D. I. S. 29: 75. [Google Scholar]

- Summers K., Howells A., Pyliotis N., 1982. Biology of eye pigmentation in insects. Adv. Insect Physiol. 16: 119–166. [Google Scholar]

- Syrzycka M., McEachern L. A., Kinneard J., Prabhu K., Fitzpatrick K., et al. , 2007. The pink gene encodes the Drosophila orthologue of the human Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome 5 (HPS5) gene. Genome 50: 548–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takáts S., Pircs K., Nagy P., Varga A., Karpati M., et al. , 2014. Interaction of the HOPS complex with syntaxin 17 mediates autophagosome clearance in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Cell 25: 1338–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimgan M. S., Berg J. S., Stuart A. E., 2006. Comparative sequence analysis and tissue localization of members of the SLC6 family of transporters in adult Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 209: 3383–3404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomancak P., Beaton A., Weiszmann R., Kwan E., Shu S., et al. , 2002. Systematic determination of patterns of gene expression during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genome Biol. 3: RESEARCH0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomancak P., Berman B. P., Beaton A., Weiszmann R., Kwan E., et al. , 2007. Global analysis of patterns of gene expression during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genome Biol. 8: R145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermaak D., Henikoff S., Malik H. S., 2005. Positive selection drives the evolution of rhino, a member of the heterochromatin protein 1 family in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 1: 96–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K. B., Grant P., Johnson D. L., 2009. Evolution of the GST omega gene family in 12 Drosophila species. J. Hered. 100: 742–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Liu Z., Huang X., 2012a Rab32 is important for autophagy and lipid storage in Drosophila. PLoS One 7: e32086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wu Y., Zhou B., 2009. Dietary zinc absorption is mediated by ZnT1 in Drosophila melanogaster. FASEB J. 23: 2650–2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Berkey C. D., Watnick P. I., 2012b The Drosophila protein MUSTARD tailors the innate immune response activated by the immune deficiency pathway. J. Immunol. 188: 3993–4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartosch L., Gunesdogan U., Graham S. C., Luzio J. P., 2015. Recruitment of VPS33A to HOPS by VPS16 is required for lysosome fusion with endosomes and autophagosomes. Traffic 16: 727–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederrecht G. J., Brown G. M., 1984. Purification and properties of the enzymes from Drosophila melanogaster that catalyze the conversion of dihydroneopterin triphosphate to the pyrimidodiazepine precursor of the drosopterins. J. Biol. Chem. 259: 14121–14127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai R. G., Cao Y., Hiesinger P. R., Zhou Y., Mehta S. Q., et al. , 2006. Drosophila NMNAT maintains neural integrity independent of its NAD synthesis activity. PLoS Biol. 4: e416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. C., Cannon S. B., Stacey G., 2009. Evolutionary genomics of LysM genes in land plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 9: 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen Y., Stenmark H., 2015. Cellular functions of rab GTPases at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 128: 3171–3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequences of mutant alleles have been deposited in Genbank (accession nos. KU665627 – cho1, KU682283 – ma1, KU682282 – mah1, red KU711835 - red1 and red KU711836 - redK1). Other gene sequences are available by request. Aligned nucleotide sequences for the red mutants and OreR are in Figure S1. Table S2 lists the primers used in cloning and sequencing. Nucleotide changes in cho, ma, and mah are in Table S3. The identifiers for all proteins used in alignments are given in Table S4. The distribution of nucleotide substitutions in the two red stocks and OreR are shown in Table S5.