Abstract

The function of the nigro-striatal pathway on neuronal entropy in the basal ganglia (BG) output nucleus (entopeduncular nucleus, EPN) was investigated in the unilaterally 6-hyroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-lesioned rat model of Parkinson’s disease (PD). In both control subjects and subjects with 6-OHDA lesion of the nigro-striatal pathway, a histological hallmark for parkinsonism, neuronal entropy in EPN was maximal in neurons with firing rates ranging between 15Hz and 25 Hz. In 6-OHDA lesioned rats, neuronal entropy in the EPN was specifically higher in neurons with firing rates above 25Hz. Our data establishes that nigro-striatal pathway controls neuronal entropy in motor circuitry and that the parkinsonian condition is associated with abnormal relationship between firing rate and neuronal entropy in BG output nuclei. The neuronal firing rates and entropy relationship provide putative relevant electrophysiological information to investigate the sensory-motor processing in normal condition and conditions with movement disorders.

Keywords: Entropy, basal ganglia, rat, globus pallidus internal, dopamine, 6-OHDA

Introduction

Executions of motor activities are envisaged in terms of selections and inhibitions of motor programs leading to the most appropriate motor sequences1. Electrophysiological activities in sensory-motor circuitries are considered as the neuronal substratum for the control of motor activities. Conditions with motor disorders result from alterations in sensory-motor circuitry and consecutive neurotransmitter imbalances and pathological electrophysiological activities. Parkinson disease (PD)2 and related conditions3 exhibit various histopathological hallmarks4 including the loss of catecholaminergic neurons (resulting in dopamine (DA) and noradrenaline (NA) depletions) which are key players in the dysfunctions of the sensory motor circuitry2, 5. Identification of pathological neuronal activities in this circuitry may condition the efficiency of future neuro-modulation therapeutics to reduce the burden of parkinsonism6.

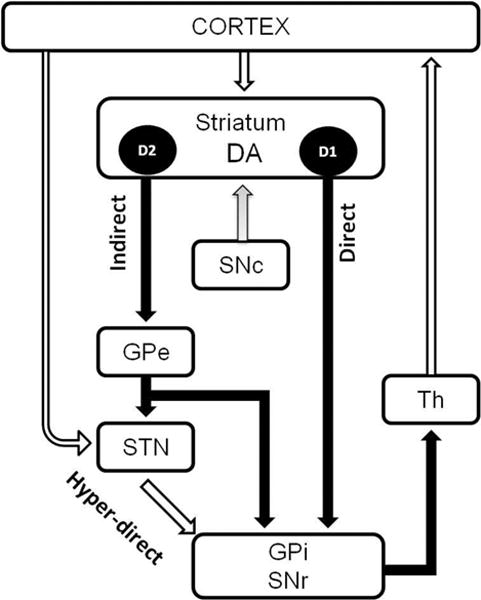

Briefly, cortical and sub-cortical areas also called basal ganglia (BG) contribute to sensory-motor processing. The BG, (Fig. 1) are a part of the cortico-cortical loops (via the thalamus)2. The striatum is the most prominent input nucleus to the BG and receives dense excitatory (glutamatergic) projections from the cortex and dopaminergic (DA-ergic) inputs from the substantia nigra compacta (SNpc). This cortical excitatory drive exerts an excitatory control on the striatal efferent neurons (medium spiny neurons, MSN)7 which project to the BG output nuclei via two pathways. The ‘direct’ pathway is a GABA-ergic monosynaptic projection, while the indirect ‘pathway’ is a GABA-ergic multisynaptic projection. These two pathways are mostly segregated in two populations of medium spiny neuron (MSN) which express different types of DA-ergic receptors8. The MSN of the direct pathway express the D1 family receptors which have excitatory effects on these neurons. In contrast, the MSN of the indirect pathway express the D2 family receptors which inhibit their activities. In human and non-human primates, the output nuclei of the BG consist in the globus pallidus internal (GPi) and the substantia nigra reticulata (SNr); the GPi receives sensory-motor inputs from the dorsal striatum and it is a target for Deep Brain Stimulation therapy (an efficient treatment to alleviate PD symptoms)9. In rodents, the entopedoncular nucleus (EPN) also receives input from the dorsal striatum10 and its stimulation can alleviate dysfunctions induced by depletion in catecholamines11. In both rodents and primates, the output nuclei of the BG are also under excitatory control arising from the cortex via a relay in the subthalamic nucleus (STN, hyperdirect pathway)12. This anatomo-functional model stresses the importance of the balance of activities between the direct, indirect and hyperdirect pathways on sensory-motor processing2. In conditions with lesion of the DA-ergic nigro-striatal pathway (i.e. parkinsonism), the model predicts that loss of DA results in an imbalance between the direct and indirect pathway activities in favor of the indirect pathway, leading to decreased inhibition and increased neuronal firing activity in the output BG2, 3 and, secondary, to an inhibition of the thalamus13. Inhibition and excitation of the thalamus are considered promoting the selection and inhibition of movement respectively.

Figure 1. Schematization of the basal ganglia circuitry.

See introduction for discussion.

The input nuclei of the BG consist of the STN and the striatum. The output nuclei of the BG are the GPi and the SNr. The BG input nuclei receive projection from the cortical area. The STN projects to the output nuclei through the glutamatergic hyperdirect pathway. The striatum projects to the output nuclei via two pathways: the direct pathway and the indirect pathway (through the GPe).

White arrow: the inhibitory GABAergic; black arrow: excitatory glutamatergic projection; gray arrow: dopaminergic projection projections. DA: Dopamine, D1: receptors dopamine D1-like, D2: receptors dopamine D2-like, SNc: substantia nigra compacta, GPe: globus pallidus external (globus pallidus in rodent, GP), GPi: globus pallidus internal (entopedoncular nucleus in rodent, EPN), STN: subthalamic nucleus, Th: Thalamus.

The concept of summation of disinhibitory/inhibitory drives onto the output nuclei of BG has given ground to consider that coding of information relies (solely) on the firing rate of neurons2, 14 and forged the “rate hypothesis”. Under this hypothesis, the BG are seen in a steady state; increased firing rate in BG output nuclei leads to hypokinesia while decreased firing rate leads to hyperkinesia. However, critics to the model15–17 have pointed out the fact that the parkinsonian condition may be seen as a breakdown of motor control with a wide range of motor symptoms including tremor, rigidity and impairment in performing voluntary movements; therefore, alterations in the spike timing of output nuclei of BG may not solely be characterized by changes in central tendency (aka, firing rate) but may also include a breakdown of its temporal organization9, 17–21. We hypothesized that catecholaminergic regulation not only controls the ‘tone’ of the direct and the indirect pathways, but also the dynamic, or synergy, of their modulations on the output BG neurons2. This hypothesis underlies that both rate and irregularity (as defined by entropy)22, 23 of the spike timing could be jointly altered following depletion in catecholamine. Specifically, we have investigated the entropy/rate properties of output EPN neurons in rats with dopamine depletion induced by the neurotoxine 6-OHDA directly administrated in the medial forebrain bundle to lesion the nigrostriatal pathway. Recordings of single neurons firing activity were performed in the anesthetized animals to limit movement-related sensory-motor inputs and environmental perturbations. Approximate entropy (ApEn) and firing rate were used to investigate changes in spike timing in EPN neurons following catecholamine depletion and in idle (aka, anesthetized) condition. In light to the changes in entropy/rate property observed after 6-OHDA lesion, we discuss the role of the nigrostriatal pathway on neuronal firing activity in output BG neurons and sensory-motor coding.

Material and Methods

2.1 Animals

Experiments were carried out in male Sprague-Dawley rats (N = 14; weighing 220–230 g; Charles River Laboratories, Germany). Rats were housed in groups of four in standard Macrolon Type IV cages (Techniplast, Hohenpeissenberg, Germany) under a 12-h light–dark cycle (on at 07:00 h) at a room temperature of 22 ±2 °C, with food and water available at all times. All animal procedures were approved in accordance with the European Council Directive of November 24, 1986 (86/609/EEC) and approved by the local animal ethic committee. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their discomfort.

2.2 6-OHDA lesion

One group (N=8, 6-OHDA treated group) received 6-OHDA injection and a non-lesioned group (N=6, control) served as a naïve control. For surgery, rats were anaesthetized with 3.6 % chloral hydrate (1ml/100g body weight, i.p., Sigma, Germany) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting, Wood Dale, Illinois, USA). The incision area was shaved and local anaesthetic (Xylocain, s.c.) was injected along the intended incision line. Ophthalmic ointment (Bepanthen, Bayer, Germany) was applied to the eyes to avoid corneal dehydration. The skull was exposed by a midline sagittal incision. Two holes were drilled over the targets above the right medial forebrain bundle and the dura was exposed. 6-OHDA was dissolved in 0.02% ascorbate saline at a concentration of 3.6 μg/μl and was injected (1 μl/min) in two deposits (2.5 μl and 3μl, respectively) at the following coordinates in mm relative to bregma and to the surface of the dura mater: anterior (A) = −4.0; lateral (L) = ±0.8; ventral (V) = −8.0; mouth bar at +3.4 and A = −4.4; L = ±1.2; V = −7.8; mouth bar at −2.4, respectively. The injection rate was 1μl/min. Following the infusion, the cannula remained at the target site for an additional 5 minutes to allow diffusion of the neurotoxin. We did not use desipramine to prevent putative effects of 6-OHDA on non-dopaminergic catecholaminergic or indolaminergic fibers.

Body temperature was maintained at 37–37.5 °C throughout surgery by a heating pad. After infusion, the incision was closed by stitches and the animals were returned to their home cages for recovery11.

The efficacy of the 6-OHDA-induced lesion was assessed 3 weeks after surgery by challenge with apomorphine (0.05 mg/kg, s.c.; Sigma) as described by Schwarting and Huston (1996)24. Apomorphine-induced rotation was used to functionally validate the lesion in 6-OHDA treated rats. A lesion was considered successful for subjects performing more than 80 net contraversive rotations in 20 min following apomorphine administration.

2.3 Single neuronal activity recording

Electrophysiological recordings were taken in the EPN of control and hemi-lesioned rats at least 3 weeks after vehicle or 6-OHDA injection. The rats were anesthetized with urethane (1.4 g/kg, i.p.; ethyl carbamate, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and placed in a stereotaxic frame. The body temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5° C by a heating device (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME).

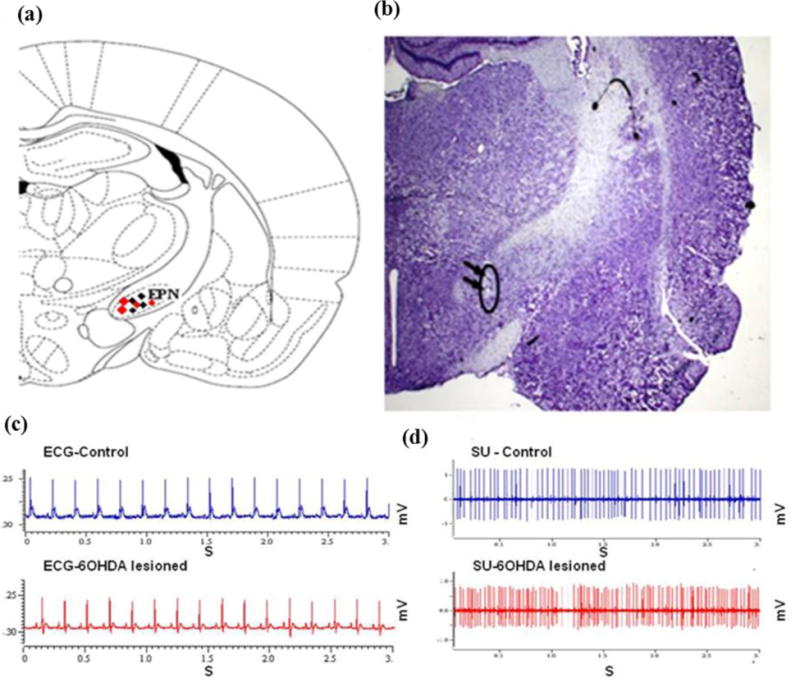

Small craniotomies were made over the target coordinate for the EPN to the ipsi- hemisphere to lesion side. A single microelectrode for extracellular recordings (quartz coated pulled with a ground platinum-tungsten alloy core (95%–5%), diameter 80 μm, impedance 1–2 MΩ) was connected to the Mini Matrix 2 channel version drives head-stage (Thomas Recording, Germany) and stereotaxically guided through the skull burr holes to the target coordinates in the EPN (A: −2.5 to −2.8 mm; L: +/− 2.5 to +/− 2.8 mm; V: −7.8 to −8.2 mm) under continuous recording of extracellular neuronal signals using a microdrive (Thomas Recording GmbH, Giessen, Germany). Single unit (SU) spike activities were recorded between 500 and 5000 Hz and amplified × 19,000 and sampled at 25 kHz. All signals were digitized with a CED 1401 (Cambridge Electronic Design, UK) and recorded for 10 to 12 min after signal stabilization with Spike2 analysis software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). 300 s of the recording were analyzed and sorted on the base of a 3:1 signal to noise ratio. After termination of the experiment, electrical lesions were made at the proximal and the distal site of the trajectory to allow histological verification of the recording site (10 μA for 10 seconds; both negative and positive polarities) as previously described25. An illustration of histological-based reconstruction from the rat brain atlas26 and of the localization of recording electrode in thionine-stained coronal section of the EPN is shown (Fig. 2a–b).

Figure 2.

(a) An illustration from the rat brain atlas of the EPN region at −2.5 mm posterior to bregma, 2.5 mm lateral to the midline and 7.8 to 8.0mm to the skull surface, localization of recording neurons for control (blue dots) and 6-OHDA lesioned rats (red dots), image modified from Paxinos and Watson (1986). (b) Histological verification showing (black arrows) the localization of a recording electrode by electric coagulation in thionine-stained coronal sections of the entopeduncular nucleus (EPN). (c) A representation of heart rate and (d) single neuronal activity for total duration of 3 s in the EPN of control (blue color) and 6-OHDA lesioned rats (red color) during microelectrode recordings.

2.4 Spike sorting

Action potentials arising from a single neuron were discriminated by the template-matching function of the spike-sorting software (Spike2; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). Only well isolated SUs were included in the analysis, which was determined by the homogeneity of spike waveforms, the separation of the projections of spike waveforms onto principal components during spike sorting, and clear refractory periods in ISIs histograms. All analyses were performed using custom-written Matlab routines (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Firing rate was calculated by taking the reciprocal value of the mean ISI for the whole 1000 spikes of recording.

2.5 Entropy and firing rate analyses

Entropy (as measured by Approximate Entropy, ApEn) is, by definition, a measurement for irregularity in a time series27. ApEn was defined by Pincus23, 28 as fellow:

With

where

for k=1,2,…,m and i=j=1,2,…,N.

measures the regularity between patterns of windows length m and within a tolerance r. The value of ApEn increases when an observed pattern is not followed by additional similar patterns in the time series. A time series that is rendered highly predictable by repetitive patterns has a relatively small ApEn; a less predictable process (or more random-looking progress) has a higher ApEn.

In comparison to analyses in time, frequency and non-linear domains, the order of the data in the time series is the crucial factor. Briefly, the standard deviation (STD), mean or coefficient variation (CV) measure the central tendency and dispersion of the magnitude of a series and these measurement are independent of the order of the data. In contrast, ApEn (and other entropy measurements) depends on the temporal organization of the data.

For example, let’s consider the following sequences: A=[2 2 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 2] and B= [1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2]. Then, STD(A)=STD(B)=0.53; mean (A)=mean(B)=1.50; and therefore CV(A)=CV(B)=0.35. Using the previous data samples and for the m and r fixed at 2 and 0.1 respectively: ApEn(A)=0.51 and ApEn(B)=0.01. In the first case (A), the signal is irregular (aka, the next value is highly unpredictable) therefore the entropy of this signal is high; in the second case (B), the signal is very regular (aka, the next value is highly predictable), therefore entropy is very low.

Because ApEn is dependent on the record length N, contiguous segments of strictly 1000 ISIs were used. As previously discussed by others, the embedding dimension (m) was fixed at 222, 28, 29. In the current study, the vector comparison length (tolerance, r) was set to an absolute value. This is a different approach from previous studies22 which used a r value relative to the standard deviation (STD) and this technical consideration is further developed in the discussion.

2.6 Statistics

Central tendencies are expressed in median and dispersion in percentiles (range 25th–75th percentiles). Differences between groups were tested using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. We used the Friedman test to determine the effects of 6-OHDA on the relation between entropy and firing rate.

Results

Comparison of the effects of treatments between control and 6-OHDA treated subjects

In this study, all 6-OHDA treated subjects responded to apomorphine challenge by developing over 80 net contralateral rotations in 20 min (110 turns/20min, range: 104–122). The level of anesthesia was assessed by testing reflexes to a hind-paw or tail pinch every 15 minutes and electrocardiographic activity. Control and 6-OHDA treated subjects did not exhibit flexor reflex to pinch during the recording sessions; heart beat rate was similar between groups with 354.87 b/min (312.87–370.4) for control and 358.85b/min (309.54–368.66) in 6-OHDA treated rats (Fig. 2c).

Comparison of the spike timing from EPN neurons between control and 6-OHDA treated subjects

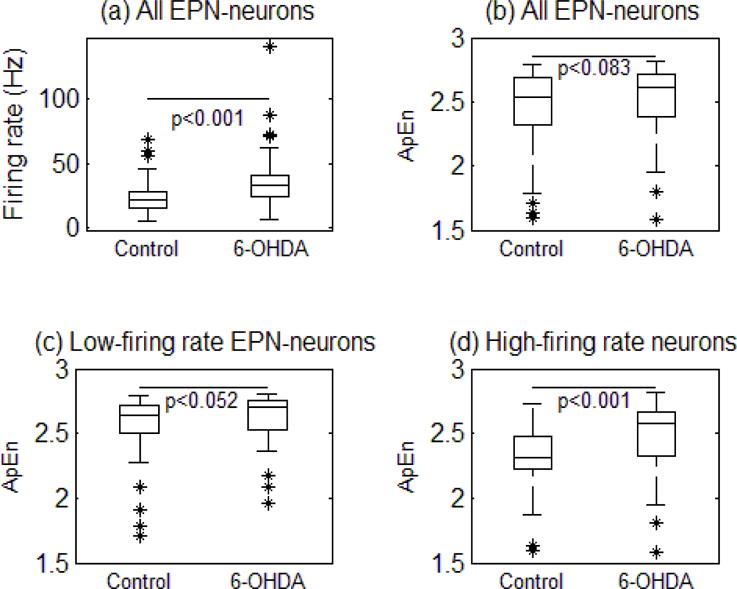

One hundred eight neurons from 6-OHDA treated rats (10 neurons/rat; range: 6.5–20) and 80 neurons from naive control rats (13 neurons/rat; range: 13.0–15.0) were included in this study. An example of spontaneous single-unit activity in the EPN over 3 seconds in the control and 6-OHDA lesioned rats is shown (Fig. 2d). In control subjects, the mean firing rate of EPN neurons was 21.96 Hz (range: 15.21–28.23). In 6-OHDA treated rats, the mean firing rate was significantly increased (RS=5466, z= −5.68, P <0.001) to 33.36 Hz (range 23.82–40.88) (Fig. 3). On the over-all population, entropy was slightly increased from 2.54 (range: 2.32–2.69) to 2.62 (range: 2.39–2.71) (P<0.09, Z= −1.39, RS= 7048) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The box plots illustrate the summary of changes in the firing rate (a), the ApEn values for all the neuronal activity between groups (b), the ApEn values for the neuronal activity less than <25Hz (c) and the ApEn values greater than >25 Hz (d) in the EPN of naïve control (N = 80) and 6-OHDA treated rats (N = 108). The central line of the box plots represents the median, the 25%–75% (interquartile) range, and the edge of the whiskers show the 5%-95% range.

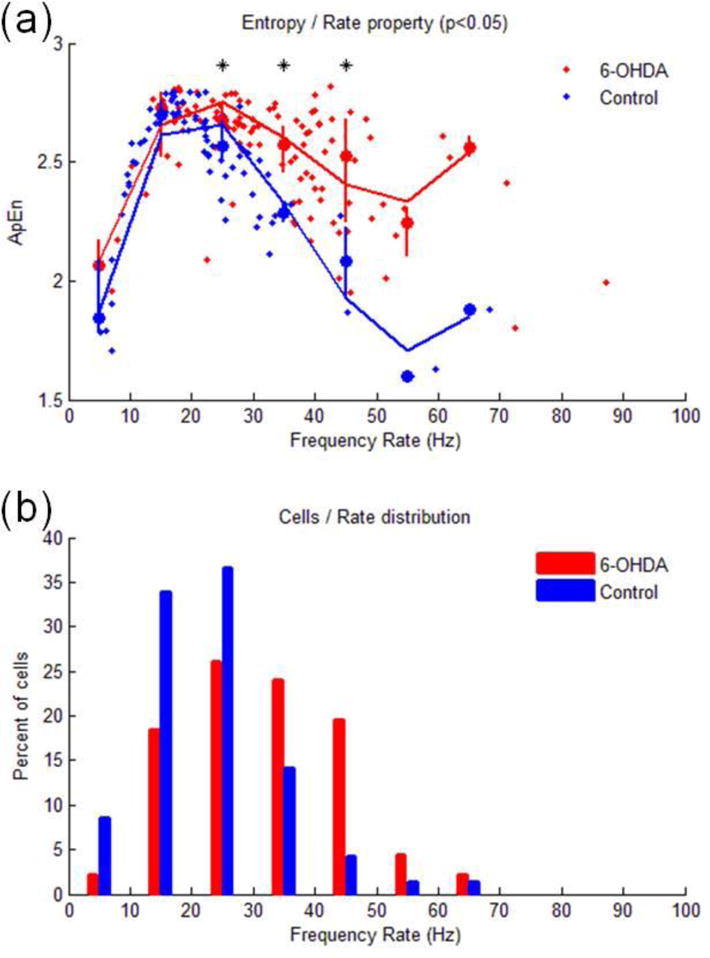

When expressing the level of entropy as function of firing rate, our data shows that entropy increased from low frequency (below 15Hz) to reach maximal value for a plateau between 15Hz and 25Hz. In control subjects, entropy drastically decreased above 25Hz but not in 6-OHDA treated subjects. For low-frequency firing neurons (firing rate below 25 Hz), entropy levels were slightly different between control (median: 2.65; range: 2.50–2.71) and 6-OHDA treated subjects (median: 2.71; range: 2.53–2.76) (P < 0.052, z=−1.63, RS= 2120). However, entropy in high-frequency firing neurons (above 25Hz) was found to be significantly higher in 6-OHDA treated rats (median: 2.58; range: 2.67–2.33) comparatively to control rats (median: 2.31; range: 2.48–2.23) (P<0.001, Z= −3.74, RS= 866).

Therefore, entropy difference between control and 6-OHDA treated subjects was mostly explained by neurons with firing above 25Hz (Friedman test, sigma: 0.71, p<0.009 Fig. 4a) which were also more frequently found in 6-OHDA lesioned subjects (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

(a): The curves illustrate the quantitative relation of ApEn values on the function of firing rate across the naïve control rats (N = 80; blue dots) and 6-OHDA treated rats (N = 108; red dots). Solid curves express the trend (Legendre polynomials, 4th order) of ApEn as function of firing rate for control rats (blue curve) and 6-OHDA treated rats (red curve). Vertical lines indicate the range (25th–75th percentiles) of ApEn at different bins of frequency rates (bin size: 10Hz). Stars at the top indicate significant differences between controls and 6-OHDA subjects (P<0.05). (b) This figure indicates the distribution of cells as function of the firing rate in the control and 6-OHDA treated animals. Y axe expresses the percent over the cell population of each group.

Discussion

The main finding of this investigation is that entropy and firing rate are related in EPN neurons and that this relation is affected by dopamine depletion. In normal and 6-OHDA lesioned subjects, EPN neurons with firing rates ranging from 15Hz to 25 Hz exhibited high entropy. In 6-OHDA lesioned subjects, EPN neurons showed higher entropy and firing rate. Interestingly, the difference in entropy between intact and lesioned subjects was dependent on the neuronal firing rate. In comparison to control subjects, EPN neurons from 6-OHDA lesioned animals exhibited higher ISIs entropy in neurons with firing rate exceeding 25Hz.

It is worth first discussing a few technical aspects that characterize the current study from previous ones on BG entropy.

At the computational level, most of the previous studies using ApEn to measure irregularity in spike timing of BG neurons18, 22, 29 set the tolerance value of “r” to a percent of the standard deviation in order to filter the noise in the signal believed to be proportional to the magnitude of the signal. This strategy is adequate for bio-signals that have their magnitude dependent on technical methodologies23. For example, the magnitude of the local field potentials can vary as functions of the impedance of the electrode and the distance between electrodes. However, in the case of single unit recording, noise (or error) on interval interspike series cannot exceed the minimal interval tolerated for differentiating two spikes which is defined by the refractory period (1ms or 0.001s). In addition, the relative r value as the mathematical result to de-correlate entropy value from the magnitude of the signal is used. Again, this is a valuable feature when the variability in the signal amplitude results from technical methodologies. However, sources of irregularities in the interval interspikes are not all scaled with mean frequency rate. For example the base line firing rate of DA-ergic cells is poorly predictive of the burst-firing frequency30. We therefore used an r value fixed at the refractory period (0.001 s) for all the population of neurons analyzed under the assumption that the systemic error on identifying the spike is not dependent on neuronal activity.

Also, and in contrast to previous investigation on non-linear dynamic of spike timing in basal ganglia neurons, the current study was performed under anesthesia. During recording sessions, the depth of anesthesia was carefully controlled by monitoring autonomic and nociceptive functions. Under urethane anesthesia, the heart rate and reflex suppression to pinch were similar between control and 6-OHDA. In agreement with previous studies11, these observations support the view that depth of anesthesia was identical between groups and during the recording sessions. As previously reported under anesthesia31 or in awake state32, our data shows that loss of DA-ergic neurons in 6-OHDA lesioned rats increases neuronal firing rate in EPN. Therefore, and in addition to previous studies reporting that urethane anesthesia does not reverse the differences in neurochemistry between control and 6-OHDA treated subjects33, our investigation confirms that this paradigm preserves the main electrophysiological hallmarks for parkinsonism (aka, higher firing rate in EPN)31, 34. Because control and 6-OHDA subjects were recorded under anesthesia, the differences in linear and non-linear measurement of spike timing are unlikely dependant of movement, perception and arousal35 but more likely related to the lesions induced by the neurotoxin. In agreement with our previous clinical investigation reporting that DA receptor agonist apormorphine decreases entropy and firing rate of spike timing in parkinsonian patients18, our current study reports without surprise that lesions induced by 6-OHDA increase entropy. Though 6-OHDA per se can affect both DA-ergic and noradrenergic cells, the noradrenergic component of intranigral 6-OHDA may be epiphenomenal36 or elusive37–39 on BG circuitry activity. Data raised above supports the view that: (1) urethane did not mask the effects of 6-OHDA lesion on circuitry activity, (2) lesion of 6-OHDA effects on entropy corroborate those previously reported dependant on DA-ergic activity in awake PD patients.

Previous studies have described non-linear features in spontaneous discharge of BG neurons of animals or patients in awake state. Such spontaneous activity does not represent true ‘idling’ of the BG thalamocortical circuitry because the subjects were certainly engaged in cognition, small-amplitude movements or sensorial stimulation during recording22, 35. In one hand, the use of experimental paradigm under anesthesia allowed to isolate the effects of 6-OHDA from such confounding factors22. On the other hand, under anesthesia, the loss of motor manifestation associated to the condition resulting from both peripheral and central effects of urethane limits the interpretation of the entropy/rate property in term of its relationship to specific movement disorders which is out of the scope of the current investigation.

Our data raised above supports the view that DA depletion increases entropy in the output nuclei of the BG, firing rate and alters the relationship between firing rate and entropy in EPN neurons. In the DA depleted subjects, increased firing rate in EPN-neurons is predicted by an overall imbalanced activity in favor of indirect pathways40–43 and an increased glutamatergic drive from the hyperdirect pathway44. In agreement with the ‘irregularity hypothesis’18, 45–47, depletion in DA resulted in overall higher entropy in the spike timing of EPN neurons. The entropy/rate property observed in the population of EPN neurons and its alteration following nigro-striatal lesion provides new insights on the coding properties of EPN neurons. In contrast to the ‘rate coding’ hypothesis, which underlies a static balance between the excitatory and inhibitory drives2, the ‘entropy hypothesis’ underlies that irregularity in the spike timing is a reflection of a dynamic balance exerted by fluctuant excitatory and inhibitory drives.

In intact subjects, entropy was found maximal in EPN neuronal activity with firing rates ranging from15Hz to 25Hz therefore high neuronal entropy per se may not be an abnormal feature of BG neuronal activity17, 45. Our data indicate also that EPN is composed of heterogenous subpopulation of neurons with distinct entropy/rate properties. Comparison of entropy/rate properties between groups shows that coexistence of high entropy and high firing rate in the spike timing of EPN neurons is a functional hallmark of EPN neurons associated to nigro-striatal lesion.

In dopamine depleted pathological condition, high entropy in EPN neurons was observed in high frequency neurons. These data can be interpreted as a consequence from EPN disinhibition which lower the threshold of neuronal excitability48, 49 and increase the efficiency of coincident excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSPs) to induce neuronal firing13. Following lesion of nigrostriatal pathway, increased neuronal entropy in EPN may be envisaged as infiltration of neuronal coding likely caused by hyperexcitability to the coincident inputs50. This hypothesis is also supported by computational approaches demonstrating that complex systems with high cohesion can exhibit low entropy, while systems with reduced cohesion can exhibit high irregularities causal to independent behaviors of their constitutive entities51. An alternative, but not exclusive, hypothesis is that increase in EPN neuronal entropy following DA-ergic depletion reflects18 an increase in un-coincidental events between the hyperdirect, direct and indirect pathways engendering irregularities in EPN neurons52. Since this investigation was performed under anesthetic condition, the relationship between entropy/rate property and movement disorders could not be characterized. In anaesthetized state, it cannot be ruled out that some of the effects of 6-OHDA might have been accentuated by urethane47, 53. The robustness of the entropy/rate property to arousal and its relevance on motor symptoms in parkinsonism are warranted to be investigated. Since both irregularity and oscillatory activities are known to co-exist and interact in other circuitries (i.e. autonomic circuitry, cortex)54, 55, future investigations in behaving subjects are warranted to investigate the relationship between oscillatory activity and entropy55 in the BG of behaving subjects.

Conclusion

Irregularity in EPN neurons was found maximal in neurons with firing rates ranging between15Hz and 25 Hz. DA depletion increased entropy in the EPN neurons and this increase in entropy was more pronounced in neurons with firing rates higher than 25Hz. Our data establish that lesion of the nigro-striatal pathway, a hallmark for parkinsonism, has synergic effects on firing rate and entropy in EPN neurons. The rate-irregularity relationship may be a relevant feature to identify, localize and quantify pathological electrophysiological activities of the BG in the context of movement disorders. Finally, integration of the entropy-rate feature into computational model56, 57 and/or brain interface system58 may help to detect misprocessing episodes of sensory motor information.

Acknowledgments

Dr O. Darbin is supported by the Department of Neurology University of South Alabama College of Medicine (Mobile, AL, USA) and by the Division of System Neurophysiology at the National Institute for Physiological Sciences (Okasaki, Japan). Research reported in this publication/press release was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR00165, the Strategic Japanese-German Cooperative Program, JST (to AN), and the foundation for medical science in Alabama (to OD). Xingxing Jin received funding from The Chinese Scholarship Council. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health and other supports.

Contributor Information

Olivier Darbin, Department of Neurology, University South Alabama, Mobile AL, US; Division of System Neurophysiology, National institute for physiological sciences, Okazaki, Japan; Animal resource program, University Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, US.

Xingxing Jin, Department of Neurosurgery, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Christof von Wrangel, Department of Neurosurgery, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Kerstin Schwabe, Department of Neurosurgery, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Atsushi Nambu, Division of System Neurophysiology, National institute for physiological sciences, Okazaki, Japan.

Dean K Naritoku, Department of Neurology, University South Alabama, Mobile AL, US.

Joachim K. Krauss, Department of Neurosurgery, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany

Mesbah Alam, Department of Neurosurgery, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

References

- 1.Mink JW. The basal ganglia: focused selection and inhibition of competing motor programs. Progress in Neurobiology. 1996;50:381–425. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gatev P, Darbin O, Wichmann T. Oscillations in the basal ganglia under normal conditions and in movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1566–77. doi: 10.1002/mds.21033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darbin O. The aging striatal dopamine function. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:426–32. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease-related pathology. Cell and tissue research. 2004;318:121–134. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Rodriguez M, Lanciego JL, Artieda J, Gonzalo N, Olanow CW. Pathophysiology of the basal ganglia in Parkinson’s disease. Trends in Neurosciences. 2000;23:S8–S19. doi: 10.1016/s1471-1931(00)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIntyre CC, Chaturvedi A, Shamir RR, Lempka SF. Engineering the Next Generation of Clinical Deep Brain Stimulation Technology. Brain stimulation. 2015;8:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West AR, Floresco SB, Charara A, Rosenkranz JA, Grace AA. Electrophysiological interactions between striatal glutamatergic and dopaminergic systems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1003:53–74. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerfen CR, Surmeier DJ. Modulation of striatal projection systems by dopamine. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:441–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nambu A, Chiken S. Deep Brain Stimulation for Neurological Disorders. Springer; 2015. Mechanism of DBS: Inhibition, Excitation, or Disruption? [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Der Kooy D, Carter DA. The organization of the efferent projections and striatal afferents of the entopeduncular nucleus and adjacent areas in the rat. Brain Res. 1981;211:15–36. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alam M, Capelle HH, Schwabe K, Krauss J. Effect of Deep Brain Stimulation on Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesias and Striatal Oscillatory Local Field Potentials in a Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Brain stimulation. 2014;7:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nambu A. Deep Brain Stimulation for Neurological Disorders. Springer; 2015. Functional Circuitry of the Basal Ganglia. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nambu A. A new approach to understand the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2005;252(Suppl 4):IV1–IV4. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-4002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nambu A. Seven problems on the basal ganglia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leblois A, Meissner W, Bioulac B, Gross CE, Hansel D, Boraud T. Late emergence of synchronized oscillatory activity in the pallidum during progressive Parkinsonism. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;26:1701–1713. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montgomery EB., Jr One View of the Current State of Understanding in Basal Ganglia Pathophysiology and What is Needed for the Future. Journal of Movement Disorders. 2011;4:13–20. doi: 10.14802/jmd.11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darbin O, Adams E, Martino A, Naritoku L, Dees D, Naritoku D. Non-Linear Dynamics in Parkinsonism. Front Neurol. 2013;4:211. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lafreniere-Roula M, Darbin O, Hutchison WD, Wichmann T, Lozano AM, Dostrovsky JO. Apomorphine reduces subthalamic neuronal entropy in parkinsonian patients. Exp Neurol. 2010;225:455–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andres DS, Cerquetti D, Merello M. Finite dimensional structure of the GPI discharge in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Int J Neural Syst. 2011;21:175–86. doi: 10.1142/S0129065711002778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andres DS, Gomez F, Ferrari FA, Cerquetti D, Merello M, Viana R, Stoop R. Multiple-time-scale framework for understanding the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2014;90:062709. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.90.062709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossello JL, Canals V, Oliver A, Morro A. Studying the role of synchronized and chaotic spiking neural ensembles in neural information processing. Int J Neural Syst. 2014;24:1430003. doi: 10.1142/S0129065714300034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darbin O, Soares J, Wichmann T. Nonlinear analysis of discharge patterns in monkey basal ganglia. Brain Res. 2006;1118:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pincus S. Approximate entropy (ApEn) as a complexity measure. Chaos. 1995;5:110–117. doi: 10.1063/1.166092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarting R, Huston J. The unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesion model in behavioral brain research. Analysis of functional deficits, recovery and treatments. Progress in Neurobiology. 1996;50:275–331. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Wrangel C, Schwabe K, John N, Krauss JK, Alam M. The rotenone-induced rat model of Parkinson’s disease: Behavioral and electrophysiological findings. Behav Brain Res. 2015;279:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2nd. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pincus SM. Approximate entropy as a measure of irregularity for psychiatric serial metrics. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:430–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pincus SM. Approximate entropy as a measure of system complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2297–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim J, Sanghera MK, Darbin O, Stewart RM, Jankovic J, Simpson R. Nonlinear temporal organization of neuronal discharge in the basal ganglia of Parkinson’s disease patients. Exp Neurol. 2010;224:542–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grace AA, Bunney BS. The control of firing pattern in nigral dopamine neurons: burst firing. The Journal of neuroscience. 1984;4:2877–2890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02877.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breit S, Bouali-Benazzouz R, Benabid AL, Benazzouz A. Unilateral lesion of the nigrostriatal pathway induces an increase of neuronal activity of the pedunculopontine nucleus, which is reversed by the lesion of the subthalamic nucleus in the rat. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;14:1833–1842. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruskin DN, Bergstrom DA, Walters JR. Nigrostriatal lesion and dopamine agonists affect firing patterns of rodent entopeduncular nucleus neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:487–496. doi: 10.1152/jn.00844.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cass WA, Manning MW. GDNF Protection against 6-OHDA–Induced Reductions in Potassium–Evoked Overflow of Striatal Dopamine. The Journal of neuroscience. 1999;19:1416–1423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01416.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benazzouz A, Gao D, Ni Z, Piallat B, Bouali-Benazzouz R, Benabid A. Effect of high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus on the neuronal activities of the substantia nigra pars reticulata and ventrolateral nucleus of the thalamus in the rat. Neuroscience. 2000;99:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouyer JJ, Dedet L, Debray O, Rougeul A. Restraint in primate chair may cause unusual behaviour in baboons; electrocorticographic correlates and corrective effects of diazepam. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1978;44:562–567. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(78)90123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luthman J, Bolioli B, Tsutsumi T, Verhofstad A, Jonsson G. Sprouting of striatal serotonin nerve terminals following selective lesions of nigro-striatal dopamine neurons in neonatal rat. Brain research bulletin. 1987;19:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts D, Zis A, Fibiger H. Ascending catecholamine pathways and amphetamine-induced locomotor activity: importance of dopamine and apparent non-involvement of norepinephrine. Brain Res. 1975;93:441–454. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindgren HS, Demirbugen M, Bergqvist F, Lane EL, Dunnett SB. The effect of additional noradrenergic and serotonergic depletion on a lateralised choice reaction time task in rats with nigral 6-OHDA lesions. Experimental neurology. 2014;253:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gesi M, Soldani P, Giorgi F, Santinami A, Bonaccorsi I, Fornai F. The role of the locus coeruleus in the development of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24:655–668. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galvan A, Wichmann T. Pathophysiology of parkinsonism. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119:1459–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nambu A. A new dynamic model of the cortico-basal ganglia loop. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:461–6. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obeso JA, Marin C, Rodriguez-Oroz C, Blesa J, Benitez-Temino B, Mena-Segovia J, Rodriguez M, Olanow CW. The basal ganglia in Parkinson’s disease: current concepts and unexplained observations. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(Suppl 2):S30–46. doi: 10.1002/ana.21481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang JK, Moro E, Mahant N, Hutchison WD, Lang AE, Lozano AM, Dostrovsky JO. Neuronal firing rates and patterns in the globus pallidus internus of patients with cervical dystonia differ from those with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:720–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.01107.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nambu A, Tokuno H, Takada M. Functional significance of the cortico-subthalamo-pallidal ‘hyperdirect’ pathway. Neurosci Res. 2002;43:111–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darbin O, Dees D, Martino A, Adams E, Naritoku D. An entropy-based model for basal ganglia dysfunctions in movement disorders. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013742671 doi: 10.1155/2013/742671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanghera MK, D O, Alam M, Krauss JK, Friehs G, Jankovic J, Simpson RK, Grossman RG. Entropy measurements in pallidal neurons in dystonia and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27(Suppl 1):S1–639. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andres DS, Cerquetti D, Merello M, Stoop R. Neuronal Entropy Depends on the Level of Alertness in the Parkinsonian Globus Pallidus in vivo. Front Neurol. 2014;5:96. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meurers BH, Dziewczapolski G, Bittner A, Shi T, Kamme F, Shults CW. Dopamine depletion induced up-regulation of HCN3 enhances rebound excitability of basal ganglia output neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quiroga-Varela A, Walters J, Brazhnik E, Marin C, Obeso J. What basal ganglia changes underlie the parkinsonian state? The significance of neuronal oscillatory activity. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;58:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kita H, Tachibana Y, Nambu A. The Basal Ganglia VIII. Springer; 2005. Glutamatergic and Gabaergic Control of Pallidal Activity in Monkeys. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanyimboh T, Templeman A. Calculating maximum entropy flows in networks. Journal of the Operational Research Society. 1993:383–396. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nambu A, Tachibana Y. Mechanism of parkinsonian neuronal oscillations in the primate basal ganglia: some considerations based on our recent work. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:74. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benhamou L, Cohen D. Electrophysiological characterization of entopeduncular nucleus neurons in anesthetized and freely moving rats. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8 doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sapoznikov D, Luria MH, Gotsman MS. Detection of regularities in heart rate variations by linear and non-linear analysis: power spectrum versus approximate entropy. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine. 1995;48:201–209. doi: 10.1016/0169-2607(95)01694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wright J. Attractor dynamics and thermodynamic analogies in the cerebral cortex: synchronous oscillation, the background EEG, and the regulation of attention. Bulletin of mathematical biology. 2011;73:436–457. doi: 10.1007/s11538-010-9562-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cen Z, Wei J, Jiang R. A gray-box neural network-based model identification and fault estimation scheme for nonlinear dynamic systems. Int J Neural Syst. 2013;23 doi: 10.1142/S0129065713500251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu C, Wang J, Chen YY, Deng B, Wei XL, Li HY. Closed-loop control of the thalamocortical relay neuron’s parkinsonian state based on slow variable. Int J Neural Syst. 2013;23 doi: 10.1142/S0129065713500172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu WY. Application of competitive Hopfield neural network to brain-computer interface systems. Int J Neural Syst. 2012;22:51–62. doi: 10.1142/S0129065712002979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]