CCR2 KO has impaired myeloid recruitment, regeneration, and failure of regenerated myofibers to attain baseline size despite increased tissue cytokines/chemokines.

Keywords: sarcopenia, monocytes/macrophages, TLRs, myogenic progenitor cells

Abstract

Skeletal muscle regeneration requires coordination between dynamic cellular populations and tissue microenvironments. Macrophages, recruited via CCR2, are essential for regeneration; however, the contribution of macrophages and the role of CCR2 on nonhematopoietic cells has not been defined. In addition, aging and sex interactions in regeneration and sarcopenia are unclear. Muscle regeneration was measured in young (3–6 mo), middle (11–15 mo), old (24–32 mo) male and female CCR2−/− mice. Whereas age-related muscle atrophy/sarcopenia was present, regenerated myofiber cross-sectional area (CSA) in CCR2−/− mice was comparably impaired across all ages and sexes, with increased adipocyte area compared with wild-type (WT) mice. CCR2−/− mice myofibers achieved approximately one third of baseline CSA even 84 d after injury. Regenerated CSA and clearance of necrotic tissue were dependent on bone marrow–derived cellular expression of CCR2. Myogenic progenitor cells isolated from WT and CCR2−/− mice exhibited comparable proliferation and differentiation capacity. The most striking cellular anomaly in injured muscle of CCR2−/− mice was markedly decreased macrophages, with a predominance of Ly6C− anti-inflammatory monocytes/macrophages. Ablation of proinflammatory TLR signaling did not affect muscle regeneration or resolution of necrosis. Of interest, many proinflammatory, proangiogenic, and chemotactic cytokines were markedly elevated in injured muscle of CCR2−/− relative to WT mice despite impairments in macrophage recruitment. Collectively, these results suggest that CCR2 on bone marrow–derived cells, likely macrophages, were essential to muscle regeneration independent of TLR signaling, aging, and sex. Decreased proinflammatory monocytes/macrophages actually promoted a proinflammatory microenvironment, which suggests that inflammaging was present in young CCR2−/− mice.

Introduction

Skeletal muscle regeneration requires intricate coordination between multiple dynamic cell populations and complex alterations in the microenvironment. Imbalances in this process result in impaired regeneration. After injury, a prominent inflammatory response of neutrophils and macrophages removes necrotic tissue [1]. Concurrently, skeletal muscle progenitor cells, also known as satellite cells, proliferate and migrate to the area of injury, differentiate, and merge to form myofibers. Impressively, this elaborate and complex process is primarily complete by 7 d, with myofiber CSA reaching baseline by ∼21–28 d in young mice [2–5]. Mechanisms of regeneration across aging and sex that contribute to dysfunction in regeneration are highly debated and poorly understood, which impedes progress in devising therapies for muscle regeneration.

Our group and others have reported differences in muscle regeneration between male and female mice. Some have suggested an advantage for females regarding regeneration [6, 7], whereas we identified comparable trajectories of regenerated CSA in young male vs. female mice [4]. However, young female mice more effectively cleared necrotic tissue but exhibited increased adipocyte area in regenerated muscle compared with males, with adipocyte area differences dependent upon having intact gonads [4], which suggested sex-specific differences in regeneration. Whereas young females were able to eventually remodel the regenerated tissue to decrease adipocyte area, female mice in middle and old ages retained the adipocytes and exhibited modest impairments in muscle regeneration as measured by regenerated myofiber CSA [2]. Of interest, old age mice with sarcopenia maintained the ability to efficiently regenerate muscle after extensive injury [2, 8].

Age-related deficits in skeletal muscle regeneration [9–11], consistent with the necessity of satellite cells to regenerate [12–14], have focused on age-related decreases in number and/or function of satellite cells [15–20]. However, minimal deficits in muscle regeneration with aging have been demonstrated by using myofiber CSA [2] or restoration of tissue architecture and function between young and old animals [8]. Even studies that focused on ex vivo satellite cells or tissue explants from animal models and humans observed no aging deficit when cultures were maintained in standard conditions [21, 22] or in cultures that contained human sera from young vs. old humans [23]. However, distinct aging differences occurred in satellite cell cultures or tissue explants that were exposed to heterochromic serum [9, 21], which suggests age-related environmental effects were more influential than stem cell age.

The paradigm of a lifelong contribution of satellite cells to skeletal muscle regeneration and eventual failure that contributes to age-related muscle atrophy (sarcopenia) has become controversial [24]. The outcome of diminished numbers and/or functional deficit in satellite cells with aging has been hypothesized to lead to sarcopenia. Fry et al. [25] inducibly depleted satellite cells, which resulted in impaired skeletal muscle regeneration after injury with no effect on sarcopenia. It is critical that we develop an understanding of the factors that link and distinguish regeneration and sarcopenia.

A concept shared across age-related pathologies is the progressive proinflammatory status known as inflammaging [26, 27]. Regarding muscle regeneration, both animal and human models of muscle injury exhibit higher and prolonged proinflammatory cytokine expression and inflammatory pathway activation in older vs. younger participants [21, 28, 29]. Myoblasts derived from older vs. younger humans also exhibited greater activation of the proinflammatory pathway, NF-κB, in response to TNF-α [29], which suggested that a proinflammatory environment may influence muscle regeneration. However, models of muscle regeneration that interfere with the contribution of proinflammatory cellular and/or environmental factors during regeneration have not been studied across sex, aging, or in the context of sarcopenia vs. regeneration.

Macrophages play a vital role in muscle regeneration; however, the essential functions of macrophages in regeneration are poorly understood. CCR2 is present on proinflammatory monocytes/macrophages [30, 31]. In mice, MCP family members, MCP-1 [32], MCP-3 [33], and MCP-5 [34], bind to CCR2, with MCP-1/CCR2 interactions being a major pathway for macrophage recruitment. Our lab has used MCP-1−/− [3, 35, 36] and CCR2−/− [3, 5, 37, 38] mice as models of diminished proinflammatory monocyte/macrophage recruitment [39]. MCP-1−/− mice exhibited impaired muscle regeneration and macrophage recruitment; however, impairments were not as severe as those observed in CCR2−/− mice [3]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the necessity of CCR2 expression for muscle regeneration [3, 5, 37, 38] and, specifically, expression of CCR2 on BM-derived cells [38]. However, CCR2 is widely expressed on MPCs [40], endothelial cells, pericytes, and fibroblasts [41]. Whether diminished macrophage recruitment, in addition to changes induced by aging and sex, will affect muscle regeneration and the possible contribution of macrophages to muscle maintenance and eventual sarcopenia is unknown.

Given the necessity of CCR2 expression, a proinflammatory chemokine receptor [39], and the deficit of macrophage numbers observed in injured muscle with resulting impaired regeneration, we hypothesized that proinflammatory macrophage populations are essential to skeletal muscle regeneration and that aging will amplify differences in regeneration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

CCR2−/− mice [42] were backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) for 6–10 generations. Original CCR2−/− breeders were generously provided by William A. Kuziel (Protein Design Laboratories, Freemont, CA, USA). Both C57BL/6J WT control mice and enhanced GFP-Tg [C57BL/6-Tg (ACTB-EGFP IOsb/J] breeders were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. CCR2−/−, WT GFP-Tg, and CCR2−/− GFP-Tg mice were bred and maintained at the Audie L. Murphy branch of the South Texas Veterans Health Care System (San Antonio, TX, USA). CCR2−/− genotype was confirmed by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from tail snips and 3 primers: i) 5′-GTG AGC CTT GTC ATA AAA CCA GTC-3′; ii) 5′TCA GAG ATG GCC AAG TTG AGC AGA-3′; and iii) 5′-TTC CAT TGC TCA GCG GTG CT-3′. Primers i and ii were used to detect the WT gene with PCR product of 180 bp, and primers ii and iii were used to detect the mutant CCR2 gene with PCR product of 450 bp. Male and female CCR2−/− mice in young (3–6 mo), middle (11–15 mo), and old (24–32 mo) age groups were used.

For TLR pathway knockout mice, C57BL/6N WT control mice were originally obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick Animal Production Area, Frederick, MD, USA) and were maintained in a breeding colony at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. TRIF−/− [43] and MyD88−/− [44] breeding pairs were originally obtained from Dr. Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) via Dr. Douglas Golenbock (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA) and were backcrossed for 8–10 generations onto the NCI C57BL/6 genetic background. Presence of the knockout alleles in each strain was validated at each generation by PCR. Mice were bred and maintained in ventilated cages under specific pathogen-free conditions in the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Laboratory Animal Resources Department, an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care–accredited facility. Young male mice age 4–6 mo were used in these studies.

All protocols complied with the U.S. National Institute of Health Animal Care and Use Guidelines and were approved by the institutional animal care and use committees of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and of the South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Chimera mice

Male mice age 6–8 wk were used as BM donors and hosts to create chimeric mice. Chimeric mice were created as previously described [38]. Host mice (WT and CCR2−/−) were fed γ-irradiated food and acidified water that contained neomycin sulfate and polymyxin sulfate B (0.2 and 0.02 mg/ml, respectively; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 4 d before and for 4 wk after BM transplantation. A total of 1100 cGy of irradiation was administered in divided doses of 620 and 480 cGy 2 h apart. Radiation was generated by a 137Ce gamma ray source using a Gammacell 40 irradiator (Atomic Energy of Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada). BM cells were sterilely isolated from GFP donor mice (CCR2−/− or WT), and 5 × 106 cells were injected into the tail vein of host mice on the same day as the mice were irradiated. Four groups of chimeric mice were created. Two host control groups—WT BM donors into WT hosts or CCR2−/− BM donors into CCR2−/− hosts—were used to control for the effects of BM transplantation. Two experimental groups of host and donor genotypes—WT BM donors into CCR2−/− hosts or CCR2−/− BM donors into WT hosts—were used to determine the effects of CCR2 expression on muscle injury, percent of fat, necrosis, and muscle fiber regeneration after injury in BM-derived vs. host-derived cells. Groups were identified with the following nomenclature: host control mice were designated as WT→WT or CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− and the experimental groups were designated as WT→CCR2−/− or CCR2−/−→WT.

The percentage engraftment of donor cells, defined as the percentage of GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood of host mice, was analyzed 4 wk after BM transplant by using flow cytometry. Blood was collected from the retro-orbital venous complex, and leukocytes were isolated as described previously [38]. Verification of the success of adoptively transferred donor BM in host mouse was conducted by flow cytometry and was shown to be stable for ≤8 wk [38]. Percentages of GFP+ cells within the total WBC population and subsets (lymphoid and myeloid) were determined on the basis of the innate fluorescence of GFP; all 4 groups exhibited similar engraftment of ≥89%. All cell analyses were performed on a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, Brea, CA, USA), and data analysis was performed by using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

CTX-induced skeletal muscle injury

Male and female (3–32 mo) and chimeric mice (≥8 wk after irradiation, 16–24 wk old) received i.m. CTX (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) injections into the hind limb muscles below the knee to induce myonecrosis. Mice were anesthetized with an inhalation of 1–2% isoflurane (Vedco, St. Joseph, MO, USA) and were kept on a warming pad to maintain body temperature during the procedure. Two 50-μl CTX (2.5 μM in normal saline) injections were delivered uniformly into the muscles of the anterior compartment. The posterior compartment received four 50-μl CTX injections.

Histology and histomorphometry

Myofiber CSA and percent fat in TA muscle were analyzed as previously described [5]. Mice were euthanized at baseline and various times after CTX injections. Anterior compartment muscles were harvested, weighed, and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin before routine paraffin embedding. The average CSA (µm2) of myofibers in a specimen was determined after outlining individual myofibers in representative, digitized images of a given TA muscle. Myofibers with centrally located nuclei were measured as regenerated fibers, and fibers with peripherally located nuclei were measured as mature fibers. Fat area (%) was calculated after manual outline of i.m. adipocyte area and division by the total area in the image. Average results were derived from similar animals at comparable time points after CTX administration.

Necrotic myofibers were distinguished by appearance: swollen/enlarged fibers with fragmented, pale, and eosinophilic cytoplasm, compared with both noninjured and regenerated cells, and the absence of centrally located nuclei that were common in regenerated myofibers. The area of muscle injury and residual necrosis in the TA muscle of individual animals was measured on H&E-stained cross-sections after digital scanning of microscope slides by using a model CS ScanScope system (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA, USA). Digitally captured slides were analyzed via ImageScope software (v10.0.36.1805; Aperio Technologies) to measure the total area of the TA, area of TA injury, and area of residual TA necrosis. The entire area of injury for a given TA muscle in cross-section was defined as the area of regenerated muscle cells with centrally located nuclei in combination with the area of residual necrotic myofibers. Percent necrosis was calculated as the area of necrosis relative to the entire area of injury. Percent injury was calculated as the entire area of injury relative to the entire CSA of the TA.

Isolation of MPCs

MPCs were isolated as previously described [45] from the hind limbs of male C57Bl/6J or CCR2−/− mice age 3–4 mo. Primary MPCs were cultured in Ham’s F-10 complete growth medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) that was supplemented with 20% FBS, 10 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor-2 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin G, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and were grown on type I collagen (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich)–coated tissue plate. MPC from 2 mice were isolated and used for each experiment. Cells were housed at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. MPC cultures used in these experiments contained >90% of cells that were positive for MyoD by immunocytochemistry, as previously described [45].

MPC proliferation assay and cell-cycle analysis

C57Bl6/J WT or CCR2−/− MPCs were plated on collagen-coated T-25 flasks at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells in growth media and were grown over a 3-d time course. At harvest, cells were trypsinized and counted via hemocytometer; 1 × 106 cells were separated, centrifuged at 170 g for 5 min, fixed in 1 ml cold 70% ethanol, and stored at 4°C. For cell-cycle analysis, fixed cells were centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min, washed with 1× PBS, and centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min. Pellets were suspended in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mg DNAse free RNAse A, and 2% 2 mg/ml propidium iodide was added. Cells were incubated in the dark for 30 min before cell-cycle DNA analysis was performed on a FACS Calibur. Experiments were performed in triplicate using cells at the third passage isolated from different animals for each mouse strain; each time point was performed in duplicate for each experiment.

MPC differentiation assay

MPCs at passage 3 were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells per 60-mm dish with ECL adhesion matrix in growth media and allowed to grow for 24 h. To induce differentiation, growth media was replaced with differentiation media (DMEM + 2% horse serum + 1% antibiotic/antimyotic) over a 6-d time course. At each time point, cells were washed with 1× PBS and fixed with 50:50 methanol acetone twice for 5 min. Cells were blocked with 1% donkey serum in PBS and immunolocalized with MF20 antibody at a 1:50 dilution for 3 h under dark, moist conditions. Cells were counterstained with Alexa Fluor 568 at a 1:400 dilution for 45 min and mounted with DAPI. For each assay, 20 images of both DAPI and rhodamine at each time point were obtained at ×10 magnification; total DAPI-stained and MF20-positive nuclei were counted. The following equations for differentiation potential and fusion index were used: differentiation potential = (nuclei within MF20-stained myotubes/total nuclei) × 100; fusion index = (myotubes with ≥2 nuclei/total nuclei) × 100, as previously described [45]. Experiments were performed in triplicate using cells isolated from different animals for each mouse strain.

Tissue inflammatory cell quantification

Hind limb muscles were harvested from young male mice, minced, and enzymatically dissociated in HBSS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) that contained 1500 U/ml collagenase II (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 4.0 U/ml dispase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 2.5 mM CaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 90 min and filtered through a 40-μm strainer (BD Biosciences) to obtain a single-cell suspension. Single-cell suspensions were treated with mAb 2.4G2 (BD Biosciences) for 20 min on ice to block Fc II/III receptors, followed by incubation with conjugated antibodies at 4°C for 30 min. Anti–CD90-FITC (53-2.1), anti–B220-FITC (RA3-6B2), anti–CD49b-FITC (DX5), anti–NK1.1-FITC (PK136), anti–Ly6G-PE (1A8), anti–Ly6G-FITC (1A8), anti–CD11b-V450 (M1/70), anti–CD11c-PE (HL3), anti–I-Ab-PE (AF6-120.1), and anti–Ly6C-APC (AL-21) were purchased from BD Biosciences; anti–F4/80-PE (BM8) was purchased from eBioscience (San Jose, CA, USA); and anti-CD301 (ER-MP23) was purchased from AbD Serotec (Raleigh, NC, USA). Monocytes were identified as CD11b+(CD90/B220/CD49b/NK1.1/Ly6G)−(F4/80/I-Ab/CD11c) −Ly6C+/− [46]. Macrophages were identified as CD11b+F4/80+ cells. Isotype controls were used to titrate each antibody to minimize background staining, propidium iodide (1 μg/ml; Sigma- Aldrich) was used for dead cell exclusion, and fluorescence-minus-one controls were used to generate gates [47]. Inflammatory cell numbers were calculated as total cells multiplied by percent cells within the corresponding gate.

Tissue lysate preparation and cytokine measurement

C57Bl6/J WT and CCR2−/− young male mice were sacrificed at days 1, 3 and 7 after CTX injections, and anterior compartment muscles of the hind limb were removed en bloc, weighed, and immediately used to prepare tissue lysates as previously described [36]. Protein in tissue lysates was determined by the Pierce BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) using a microtiter plate format. BSA from ICN Biomedicals (Costa Mesa, CA, USA) in lysate buffer was used as the standard, as previously described [36]. Murine SDF-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) tissue levels were assessed by an ELISA by per manufacturer protocol with slight modification: standards and unknowns were diluted in lysate buffer, adjusted for the amount of protein in tissue lysates, and results were expressed as pg/mg protein. The dynamic range was 156–5000 pg/ml for SDF-1. Absorption in all microtiter plate assays was monitored in a SpectraMax Plus plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and results were analyzed with SOFTmax PRO software. Protein lysates were submitted for cytokine profiling by Myriad RBM (Austin, TX, USA) using a microsphere-based immune-multiplexing technology to quantify analyte concentrations. Twenty seven cytokines/chemokines/proteins were quantified, including fibroblast growth factor-9, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, KC-GRO (KC or GROα), IL-1α, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-7, IL-10, IL-11, IL-12 (p70), IL-17α, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, lymphotactin, MCP-1, MCP-3, MCP-5, MIP-1β, MIP-2, oncostatin, SCF, RANTES, TIMP-1, TNF-α, and vascular endothelial growth factor A. Data are reported as concentration in pg/mg of protein in the tissue lysate.

Data analysis

Myofiber CSA was analyzed with Dunnett’s multiple comparison procedure using a 2-way ANOVA of least-square means to determine whether significant differences existed at different time points post-CTX injection compared with baseline values for chimera mice. Myofiber CSA, body weights, anterior compartment weights, and anterior compartment weight/body weight were analyzed with ANOVA, with Bonferroni corrected P values used to determine significant differences between the chimera groups and the different age groups for CCR2−/− mice. Percent i.m. fat compared with baseline was analyzed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test using a Bonferroni correction. Percent injury and percent necrosis were analyzed by using a Kruskal-Wallis test. Percent i.m. fat, percent injury, and percent necrosis between groups were analyzed by the exact Wilcoxon test using a Bonferroni correction.

MPC proliferation data for cell-cycle phase was Arcsin transformed, and for total number of cells, log transformed and analyzed by using a repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons. MPC differentiation data was analyzed by using a Kruskal-Wallis test. Differentiation potential, fusion index, and proliferation data between the WT and CCR2−/− strains were analyzed by using repeated measures regression testing.

Flow cytometry data and cytokines in tissue lysates were analyzed by using ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test using Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). For lysate samples with cytokines below the level of detection in the rules-based medicine assays, a value of least-detectable dose/ pg/ml was assigned to these samples [48] and was corrected for the protein in each lysate. All other analyses were performed by using SAS for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All statistical testing was 2-sided with an experiment-wise significance level of 5%. Data are presented as means ± sem. To standardize data presentation, repeated measures data from cell culture experiments were represented by line graphs, and data over time from different animal groups were represented by bar graphs.

pg/ml was assigned to these samples [48] and was corrected for the protein in each lysate. All other analyses were performed by using SAS for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All statistical testing was 2-sided with an experiment-wise significance level of 5%. Data are presented as means ± sem. To standardize data presentation, repeated measures data from cell culture experiments were represented by line graphs, and data over time from different animal groups were represented by bar graphs.

RESULTS

Sex- and age-dependent differences in anterior compartment weight and body weight in baseline muscle from CCR2−/− mice with similar trends in anterior compartment/body weight ratios

At baseline (control, uninjured mice), anterior compartment weights were increased (P ≤ 0.009) in male compared with females mice of all corresponding ages (Table 1). In both sexes, anterior compartment weight progressively decreased with age; however, only old-age mice had significantly decreased (P ≤ 0.01) anterior compartment weights compared with young mice. In parallel, body weights were increased (P < 0.001) only in middle-age males compared with female mice, whereas body weight was comparable in young and old-age mice of both sexes. In middle-age male mice, body weight was increased (P < 0.001) compared with young and old male mice, whereas body weight was comparable in females across all ages. In contrast, when anterior compartment weight was adjusted for body weight, males and females across the 3 age groups were comparable, whereas both sexes exhibited an increased (P ≤ 0.002) ratio in young compared with both middle- and old-age groups. Thus, whereas anterior compartment weight decreased with age, body weight increased until middle age and decreased thereafter, which suggests that young mice had relatively heavier anterior compartments for their body weight compared with middle- and old-age mice, consistent with a loss in muscle mass observed in sarcopenia [2, 49, 50].

TABLE 1.

CCR2−/− Baseline AC, body weight, and AC/body weight ratio

| Sex and age | AC weight (mg) | Body weight (g) | AC weight (mg)/body weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||

| Young | 92 ± 4 | 27 ± 1* | 3.5 ± 0.1 |

| Middle | 87 ± 4 | 35 ± 2 | 2.6 ± 0.1** |

| Old | 80 ± 4** | 27 ± 2* | 2.8 ± 0.1** |

| Female | |||

| Young | 79 ± 2† | 24 ± 1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 |

| Middle | 73 ± 2† | 27 ± 1† | 2.7 ± 0.1** |

| Old | 64 ± 2**,† | 24 ± 1 | 2.7 ± 0.1** |

Baseline (control, no injury) AC and body weights and AC/body weight ratios for male and female CCR2−/− mice in young (3–6 mo), middle (11–15 mo), and old (24–32 mo) age groups. Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 8–14 mice/group. AC, anterior compartment. *P < 0.001 compared with middle-age mice for each sex; **P ≤ 0.01 compared with young mice for each sex; †P ≤ 0.009 compared with male mice at the corresponding age group.

Similar impairments in muscle regeneration across age groups in male and female CCR2−/− mice despite sarcopenia in middle- and old-age mice

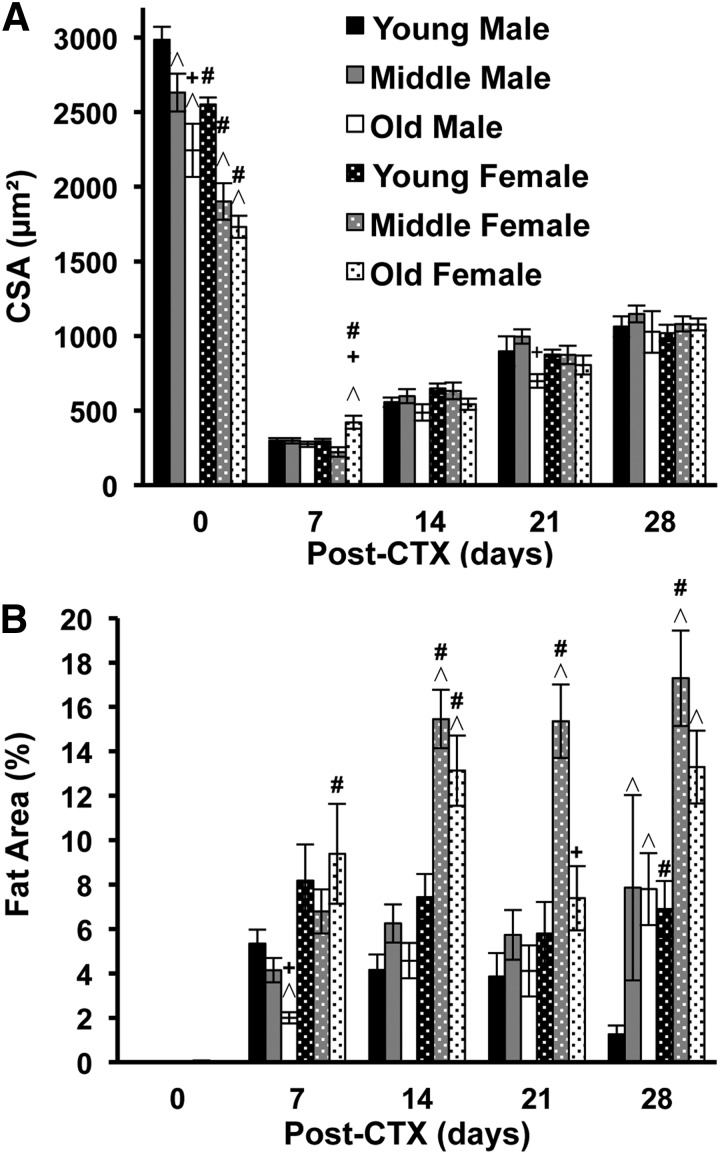

Baseline myofiber CSA in TA muscle of male mice was larger (P ≤ 0.004) than that in female mice at each corresponding age group (Fig. 1A). In both male and female mice, the average myofiber CSA progressively decreased, with male mice exhibiting decreased myofiber size in both middle and old ages compared with young (P ≤ 0.05) and old compared with middle age (P = 0.02), whereas female mice had smaller myofiber (P < 0.001) in middle- and old-age groups compared with young mice (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Effects of sex and age on baseline myofiber size, regenerated myofiber size, and fat area in CCR2−/− mice.

CSA of myocytes and area (%) of adipocytes in TA muscle of male and female mice of different ages—young (3–6 mo), middle (11–15 mo), and old (24–32 mo)—obtained at baseline (no injury, day 0) and at various times (d) after injury. (A) Myofiber CSA at baseline and in regenerated myofibers after CTX muscle injury. Regenerated myofibers were decreased (P < 0.001) at all postinjury time points compared with baseline. (B) Intramuscular fat area at baseline and in injured/regenerated muscle. Fat area was increased (P ≤ 0.02) at all postinjury time points compared with baseline. Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 3–18 mice/group/time point. ^P ≤ 0.05 compared with young mice for each sex at the corresponding time point; +P ≤ 0.03 compared with middle-age mice for each sex at the corresponding time point; #P ≤ 0.03 compared with male mice at the corresponding age group and time point.

After CTX injury, regenerated myofiber size was decreased (P < 0.001) compared with baseline in both sexes and all age groups for all postinjury time points (Fig. 1A). In contrast to the age- and sex-dependent differences in baseline fiber size, regenerated myofibers were similar in size across all age groups and sexes at each time point, with only modest differences occasionally observed (Fig. 1A). No group attained baseline fiber size by day 28 (Fig. 1A) and exhibited severe impairments in muscle regeneration compared with WT mice, as previously reported [2, 3, 5]. At 7 d post-CTX, the area of TA muscle injury (%) and necrosis (%) were similar in male and female CCR2−/− mice across the 3 ages groups, except for increased necrosis in middle-age males (P = 0.04) compared with middle-age females (Table 2). Whereas percent injury was similar to WT mice, the average residual necrosis in the groups ranged from 32 to 43% in CCR2−/− mice compared with previously reported values of ≤1% in WT mice [2].

TABLE 2.

Residual necrosis and injury in TA muscle of CCR2−/− mice 7 d after injury

| Sex and age | Necrosis (%) | Injury (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | ||

| Young | 39 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 |

| Middle | 43 ± 2 | 89 ± 2 |

| Old | 39 ± 2 | 93 ± 4 |

| Female | ||

| Young | 33 ± 2 | 86 ± 4 |

| Middle | 33 ± 2* | 91 ± 2 |

| Old | 32 ± 3 | 96 ± 1 |

Male and female CCR2−/− mice in young (3–6 mo), middle (11–15 mo), and old (24–32 mo) age groups were injected with CTX and sacrificed 7 d later. TA muscle was analyzed for injury and necrosis. Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 7–16 mice/group. *P = 0.004 compared with male mice at the corresponding age group.

Baseline fat area was minimal in both sexes and across age groups (Fig. 1B). After injury and compared with baseline, fat area was increased (P ≤ 0.02) in male and female CCR2−/− mice in all age groups and time points (Fig. 1B). In general, in regenerating muscle, fat area increased with age and female sex (Fig. 1B).

Muscle regeneration dependence upon CCR2 expression on BM-derived cells

Given the similarities in regeneration in both sexes, male radiation chimera mice were used to determine the role of CCR2 on BM-derived cells in muscle regeneration. After CTX injury, the residual necrosis phenotype was dependent upon CCR2 expression in BM-derived cells (Table 3); CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host control mice had greater (P < 0.001) residual necrosis compared with WT→WT host control mice. Experimental groups that received CCR2−/− BM exhibited greater (P < 0.001) residual necrosis than did host mice that received WT BM. Thus, whereas injury was similar in all groups, the extent of residual necrosis in chimera mice was dependent upon CCR2 expression on BM-derived cells.

TABLE 3.

Residual necrosis and injury in TA muscle at day 14 after injury in young, male chimera mice

| Donor BM→Host | Necrosis (%) | Injury (%) |

|---|---|---|

| WT→WT (HC) | 0.01 ± 0.01* | 82 ± 6 |

| WT→CCR2−/− | 0.24 ± 0.15* | 87 ± 4 |

| CCR2−/−→WT | 16.93 ± 2.49** | 89 ± 3 |

| CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− (HC) | 13.81 ± 2.76** | 88 ± 5 |

Host control mice (HC) were used to control for the effects of BM transplantation. Data are presented as mean ± sem; n=8–10 mice/group. *P < 0.001 vs. CCR2−/−→CCR2−/−; **P < 0.001 vs. WT→WT.

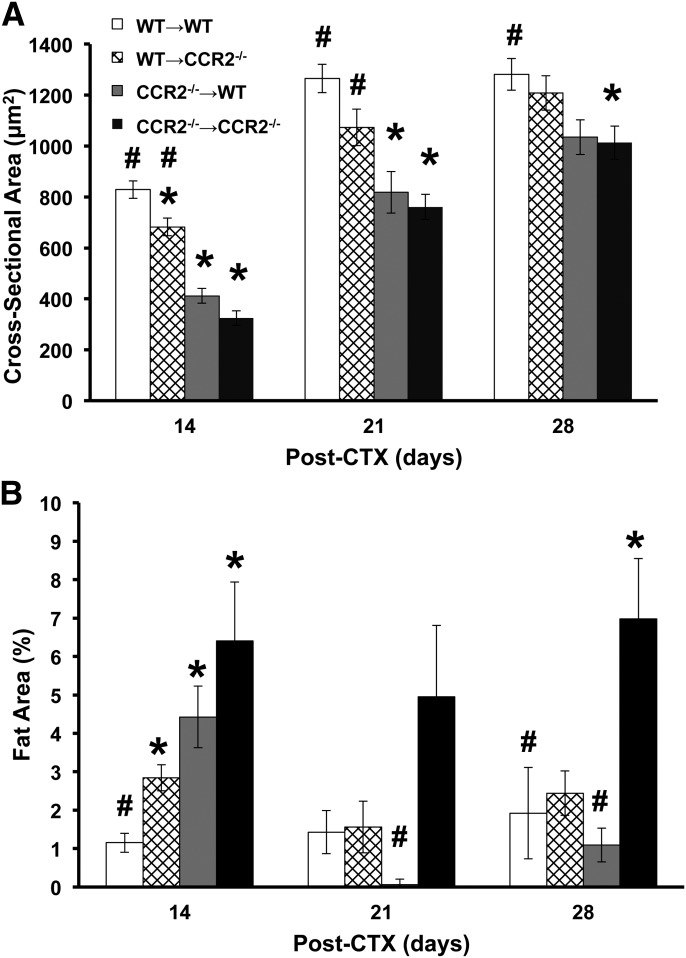

Similar to residual necrosis, regenerated CSA was also dependent upon CCR2 expression on BM-derived cells. Average baseline myofiber size was comparable in all 4 groups of chimera mice and ranged from 2736 to 3174 μm2. Compared with baseline, regenerated myofiber size was smaller (P < 0.001) in all 4 groups at each postinjury time point. To determine the role of CCR2 on BM vs. host compartments, host control mice (WT→WT and CCR2−/−→CCR2−/−) were used to control for the effect of irradiation and BM transplantation. CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host controls had smaller (P ≤ 0.04) regenerated myofiber size at each time point after injury (days 14, 21, and 28) compared with WT→WT host controls (Fig. 2A). Of interest, the regenerated myofiber size of the WT→WT host control was stable at days 21 and 28, which suggests that the myofibers may have reached the maximum postinjury size while the CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host control regenerated myofiber size continued to increase during the 28 d. In the 2 experimental groups with different genotypes for BM and host mice (WT→CCR2−/− and CCR2−/−→WT), WT→CCR2−/− mice had regenerated myofiber size comparable to WT→WT host controls, except at day 14, which exhibited smaller (P = 0.03) myofiber size. In contrast, WT→CCR2−/− mice had larger (P ≤ 0.01) regenerated myofiber size at days 14 and 21 vs. CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host controls. Regenerated myofiber size of CCR2−/−→WT was similar to CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host controls at all postinjury time points and was decreased (P ≤ 0.002) at days 14 and 21 compared with WT→WT host controls. Thus, whereas baseline myofiber size was similar in chimera mice, the phenotype of regenerated myofiber size was dependent upon CCR2−/− expression on BM-derived cells but not host cells in that CCR2−/− mice that received WT BM had myofiber size similar to WT→WT host controls and WT mice that received CCR2−/− BM had myofiber size similar to CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host controls.

Figure 2. Effects of BM donor genotype on myofiber regeneration and fat area in young, male chimera mice.

(A) Regenerated myofiber CSA was decreased (P < 0.001) at all postinjury time points compared with baseline; range of 2736–3174 µm2. (B) Intramuscular fat area in injured/regenerated muscle; baseline fat area range of 0.00–0.01%. Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 5–11 mice/group/time point; *P ≤ 0.03 compared with WT→WT; #P ≤ 0.04 compared with CCR2−/−→CCR2−/−.

Whereas phenotype of residual necrosis and regenerated myofiber size was dependent upon CCR2 expression on BM-derived cells, fat accumulation in injured muscle exhibited a different phenotypic pattern (Fig. 2B). The percent fat area in the TA at baseline was comparable in all 4 chimera groups and was essentially undetectable. Compared with baseline, percent fat area was greater (P ≤ 0.005) in all groups at each postinjury time point. CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host controls had greater percent fat area (P ≤ 0.02) at days 14 and 28 after injury compared with WT→WT host controls. The 2 experimental groups (WT→CCR2−/− and CCR2−/−→WT) had comparable fat area compared with WT→WT host control, except for an increase (P ≤ 0.006) in both experimental groups at day 14. The CCR2−/−→WT experimental group had decreased (P ≤ 0.01) fat area compared with the CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host control group, whereas the WT→CCR2−/− experimental group was comparable to the CCR2−/−→CCR2−/− host control group. Hence, expressing CCR2 in at least 1 compartment (BM or host) decreased fat area in regenerating tissue, whereas CCR2−/−→CCR2−/−, which lacked CCR2 expression in both compartments, demonstrated a sustained increase in fat area.

Young, male CCR2−/− mice did not attain baseline myofiber size, and fat area remained increased 84 d after injury

Whereas regenerated myofiber CSA after injury was dependent upon CCR2 expression on BM-derived cells in the chimera experiments, regenerated myofiber size at day 28 attained ∼40% of baseline values in all groups, and the WT→WT host control CSA was similar at days 21 and 28, which suggests that further increases in CSA were unlikely. This could be secondary to radiation effects [51] necessary to create the chimera animals. Using the same CTX injury model as in the chimera mice, Martinez et al. [3] found that WT male mice achieved baseline myofiber size within 21 d after injury, whereas CCR2−/− mice only reached ∼30% of baseline myofiber size by day 28. To determine whether CCR2−/− young, male mice could attain baseline myofiber size, we measured myofiber CSA at day 84 after injury (Table 4). Given the extended length of time after injury, CSA and myofiber distribution were determined for myofibers with both peripherally and centrally located nuclei. As previously reported in CCR2−/− mice [3], baseline CSA was 2985 ± 88 μm2, and at day 28, regenerated myofiber CSA was 1062 ± 68 μm2. At the day 84 time point, the combined CSA (peripherally and centrally located nucleated myofiber size) was 1225 ± 41 μm2, with the CSA of centrally located increased (P < 0.001) compared with myofibers with peripherally located nuclei. The majority of the CTX-injured myofibers (72 + 2%) exhibited peripherally located nuclei. In addition, fat area remained increased at 4.7 ± 1% at the day 84 time point. Thus, regenerated myofibers in CCR2−/− mice did not achieve baseline myofiber size, and increased fat area was maintained in the regenerated muscle even after an extended recovery time.

TABLE 4.

CSA and distribution of myofibers in TA muscles of young, male CCR2−/− mice at 84 d after CTX injury

| Location of nuclei | Mean fiber CSA (µm2) | Mean fiber count (n) | Mean fiber distribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral | 1076 ± 35* | 451 ± 33* | 72 ± 2 |

| Central | 1375 ± 50 | 174 ± 10 | 28 ± 2 |

| Combined | 1225 ± 41 | 625 ± 29 |

Young, male CCR2−/− mice were injected with CTX and sacrificed 84 d later. CSA was measured for myofibers with centrally located nuclei (regenerated) and peripherally located nuclei (mature) as well as CSA for the combined regenerated and mature muscle fibers. Distribution of myofibers with centrally located vs. peripherally located nuclei was determined. Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 10. *P < 0.001 compared with myofibers with centrally located nuclei.

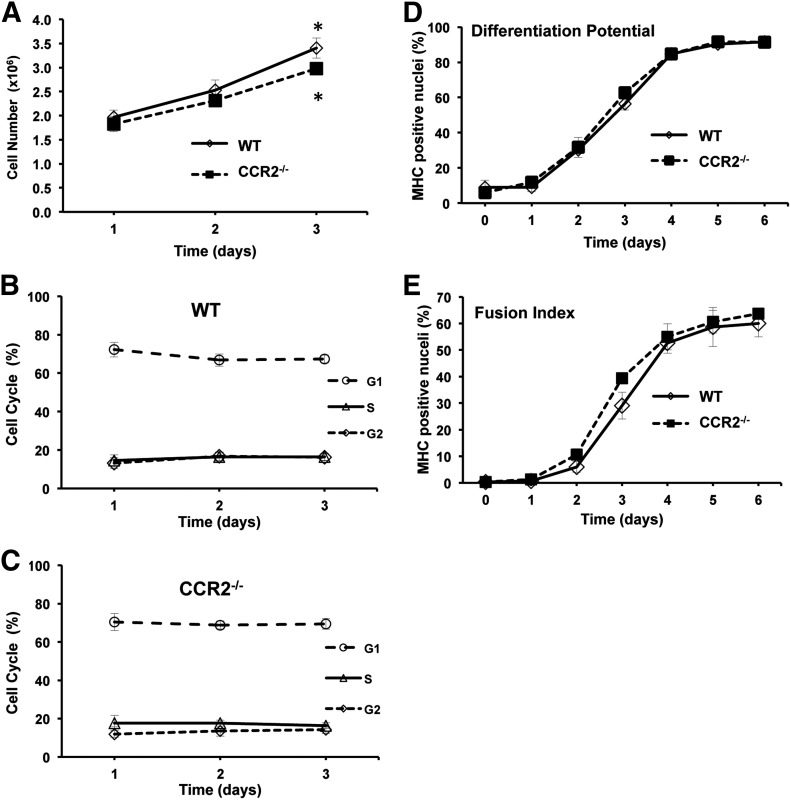

Similar in vitro proliferation and differentiation of MPCs isolated from young, male WT and CCR2−/− mice

The inability of CCR2−/− mice to attain baseline myofiber size after injury could have resulted from the absence of CCR2 on BM-derived cells or that MPCs require CCR2 for normal proliferation and/or differentiation as CCR2 is expressed on MPCs [40]. To examine the effects of CCR2 on proliferation and differentiation, MPCs were isolated from WT and CCR2−/− young, male mice. In proliferating conditions, MPCs isolated from WT and CCR2−/− mice exhibited similar total cell numbers and cell-cycle progression (Fig. 3A–C). Both WT and CCR2−/− mice had increased (P ≤ 0.04) total cells at day 3 compared with day 1 (Fig. 3A). Similarly, WT and CCR2−/− MPCs exhibited similar differentiation potential and fusion index when cultured using differentiation conditions (Fig. 3D and E). Thus, MPCs isolated from CCR2−/− mice exhibited in vitro proliferation and differentiation similar to MPCs derived from WT mice, which suggests that the absence of CCR2 on MPCs was not responsible for impairments in muscle regeneration. Taken altogether, these observations lend further support that the impaired muscle regeneration phenotype in CCR2−/− mice was a result of the absence of CCR2 on BM-derived cells.

Figure 3. Similar in vitro proliferation and differentiation between MPCs isolated from young, male WT and CCR2−/− mice.

For proliferation, MPCs were subcultured after the third passage and maintained in MPC growth media on type I collagen–coated dishes. (A) WT and CCR2−/− MPC proliferation. (B and C) Distribution of cells in different phases of the cell cycle was established by flow cytometry in WT (B) and CCR2−/− (C) MPCs. For differentiation, MPCs were subcultured after the third passage and maintained in MPC differentiation media on entactin-collagen IV-laminin–coated dishes. (D and E) Differentiation potential (D) and fusion index (E) were determined on the basis of nuclei in myosin heavy chain (MHC)–positive cells and myotubes. Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 3 different MPC primary cultures/mouse strain used at passage 3. *P ≤ 0.04 compared with 24-h time point for each strain.

Similar muscle regeneration in young, male C57Bl/6N WT and mice that lack TLR signaling

CCR2 is a proinflammatory receptor that is critical for proinflammatory cell recruitment, which is essential for skeletal muscle regeneration [3, 38], suggesting that other proinflammatory receptors may also be essential for muscle regeneration. TLRs represent another type of proinflammatory receptor [52] and are responsible for initiating inflammatory responses in many tissues [53]. Indeed, TLR signaling induced MCP-1, the principle ligand for CCR2, in skeletal muscle [54]. We used 2 mouse strains with deletions in the TLR signaling adaptor molecules, MyD88 and TRIF, which are required for the 2 major TLR signaling pathways, to investigate the role of TLR signaling in muscle regeneration (Table 5). The day 7 time point after CTX-induced injury was chosen, as 4 different parameters of muscle injury/regeneration could by simultaneously assessed. We were surprised to discover that injury, necrosis, CSA, and fat area were similar in WT and in TLR signaling–deficient TRIF−/− and MyD88−/− mice. Thus, whereas the presence of CCR2 was essential for muscle regeneration, TLR signaling, which is often responsible for the expression of CCR2 ligands during proinflammatory responses, was not required for muscle regeneration in our model.

TABLE 5.

Similar muscle regeneration in young, male WT mice and mice deficient in TLR signaling

| Mice | CSA (μm2) | Fat (%) | Injury (%) | Necrosis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1181 ± 44 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 98 ± 1 | 1.56 ± 0.90 |

| TRIF−/− | 1026 ± 75 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 99 ± 0 | 0.48 ± 0.24 |

| MyD88−/− | 1046 ± 50 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 95 ± 3 | 0.44 ± 0.22 |

TA muscle in cross-section 7 d after CTX injury was used to determine the CSA, fat, injury, and necrosis of young, male C57BL6/N WT and knockout mice with 2 different TLR signaling pathways, TRIF−/− and MyD88−/−. Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 6 mice/strain.

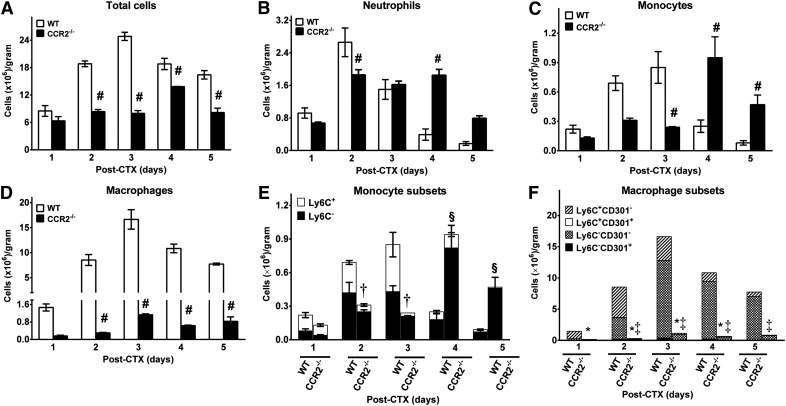

Inflammatory cell recruitment to injured skeletal muscle in young, male WT and CCR2−/− mice

Given impairments in skeletal muscle regeneration in CCR2−/− mice and the roles of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory monocytes and macrophages in muscle repair [55], inflammatory cells and the phenotype of monocyte and macrophage subsets in CTX-injured muscle in young, male WT and CCR2−/− mice were quantified by flow cytometry (Fig. 4). Total cells recovered from injured muscle (Fig. 4A) were increased (P ≤ 0.003) in WT mice at days 2–5 compared with CCR2−/− mice. Minimal inflammatory cells were present in baseline muscle in both WT and CCR2−/− mice [3]. In WT mice, neutrophil recruitment (Fig. 4B) after injury peaked at day 2 and decreased thereafter. In contrast, CCR2−/− mice had decreased (P = 0.01) neutrophils at day 2 compared with WT mice, but remained elevated with increased (P < 0.001) neutrophils in CCR2−/− compared with WT mice at day 4 after CTX injury.

Figure 4. Inflammatory cell recruitment in young, male WT and CCR2−/− mice after CTX injury.

Cells isolated from CTX-injured muscle were analyzed by flow cytometry at the indicated times. (A–F) Total cells (A), neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) (B), monocytes (CD11b+(CD90/B220/CD49/NK1.1/Ly6G)−(F4/80/I-Ab/CD11c)−Ly6C+/−) (C), macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+) (D), monocyte subsets (E), and macrophage subsets (F). Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 3 mice/strain/time point. #P ≤ 0.05 WT vs. CCR2−/− mice at the corresponding time point; †P ≤ 0.003 Ly6C+ monocyte subset WT vs. CCR2−/− mice at the corresponding time point; §P ≤ 0.01 Ly6C− monocyte subset WT vs. CCR2−/− mice at the corresponding time point; *P ≤ 0.03 for Ly6C+CD301− macrophage subset WT vs. CCR2−/− mice at the corresponding time point; ‡P ≤ 0.02 for Ly6C−CD301− macrophage subset WT vs. CCR2−/− mice at the corresponding time point.

Total monocytes (Fig. 4C; see Supplemental Fig. 1 for gating strategy) revealed different patterns of recruitment in WT and CCR2−/− mice. In WT mice, monocytes peaked at day 3, decreasing thereafter, and contained similar numbers of proinflammatory Ly6C+ and anti-inflammatory Ly6C− monocytes until Ly6C− monocytes predominated at days 4 and 5 (Fig. 4E). In contrast, in CCR2−/− mice, whereas maximal monocyte numbers were similar to WT mice, recruitment was delayed, with a decrease (P < 0.001) at day 3 and an increase (P ≤ 0.05) in monocytes at days 4 and 5 in CCR2−/− mice. In WT mice, Ly6C+ monocytes predominated early, whereas Ly6C− monocytes were the majority at days 4 and 5. In contrast, essentially all monocytes in CCR2−/− mice were Ly6C− (Fig. 4E). Ly6C+ monocytes were increased (P ≤ 0.003) at days 2 and 3 in WT compared with CCR2−/− mice, whereas Ly6C− monocytes were increased (P ≤ 0.01) in CCR2−/− compared with WT mice. Thus, monocyte recruitment was delayed in CCR2−/− mice, and subsets were altered with minimal Ly6C+ monocytes compared with WT mice.

Total macrophages, defined as CD11b+F4/80+ cells (Fig. 4D; see Supplemental Fig. 2 for gating strategy), in WT mice peaked at day 3 and remain elevated through day 5 (Fig. 4D). In contrast, minimal macrophages were present in CCR2−/− injured muscle and were decreased (P < 0.001) compared with WT mice at days 2–5. Similar to a previous report [55], minimal macrophages in injured muscle were positive for the M2 marker, CD301, in both WT and CCR2−/− mice. In WT mice, proinflammatory Ly6C+ macrophages predominated at days 1 and 2 after injury with macrophages that were negative for both Ly6C and CD301 predominating thereafter (Fig. 4F). In CCR2−/− mice, macrophages that were negative for both Ly6C and CD301 predominated at all time points; minimal Ly6C+ macrophages were present. Compared with CCR2−/− mice, in WT mice, Ly6C+CD301− macrophages were increased (P ≤ 0.03) at days 1–4, whereas Ly6C−CD301− macrophages were increased (P ≤ 0.02) at days 2–5. Thus, CCR2−/− mice had minimal macrophages throughout the studied time course, and altered macrophage subsets were characterized by an absence of Ly6C+ macrophages.

Elevated cytokines/chemokines in injured and regenerating muscle in young, male CCR2−/− mice

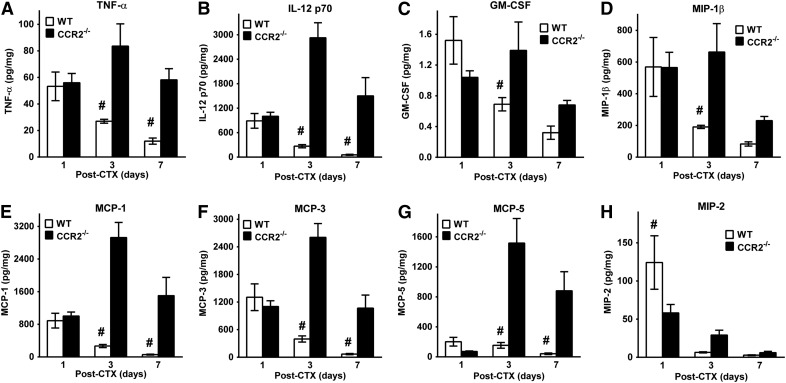

Given impairments in muscle regeneration and tissue macrophages in young, male CCR2−/− mice (Fig. 4), we measured cytokines/chemokines in injured muscle that was obtained at 1, 3, and 7 d after CTX-induced injury in young, male WT and CCR2−/− mice. The following cytokines/chemokines had comparable levels in WT and CCR2−/− muscle at all 3 postinjury time points: fibroblast growth factor-9, IL-1α, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-11, IL-17α, vascular endothelial growth factor, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, lymphotactin, RANTES, and IFN-γ (data not shown). However, many proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines—TNFα, IL-12 p70, GM-CSF, MIP-1β, MCP-1, MCP-3, and MCP-5 (Fig. 5A–G)—were elevated in CCR2−/− compared with WT mice. A consistent pattern for multiple proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines emerged; comparable levels at day 1 after injury, with elevations at day 3 (P ≤ 0.02; Fig. 5A–G) and day 7 (P ≤ 0.005; Fig. 5A, B, and E–G) in CCR2−/− compared with WT mice. A notable exception to this pattern was MIP-2 (Fig. 5H). MIP-2 was increased (P = 0.02) in WT compared with CCR2−/− muscle at day 1 after injury and comparable at days 3 and 7.

Figure 5. Increased proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in young, male CCR2−/− mice compared with WT mice after CTX injury.

(A–H) Measurement of tissue cytokines/chemokines normalized to total protein in the anterior compartment of WT and CCR2−/− mice after CTX-induced injury for TNF-α (Α), IL-12p70 (B), GM-CSF (C), MIP-1β (D), MCP-1 (E), MCP-3 (F), MCP-5 (G), and MIP-2 (H). Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 4–8 mice/strain/time point. #P ≤ 0.02 WT vs. CCR2−/− mice at the corresponding time point.

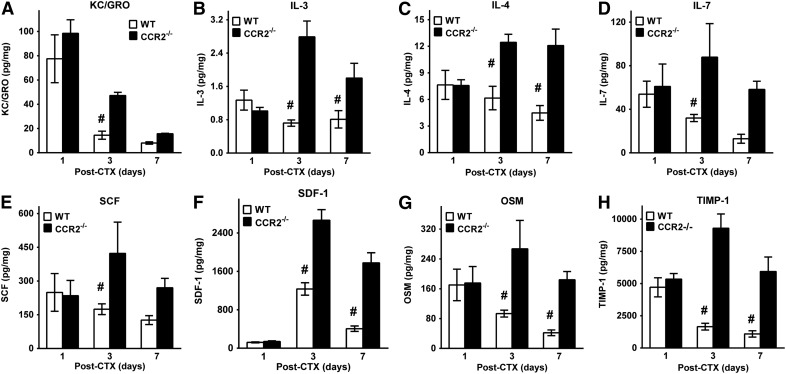

In addition to proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines, many other cytokines/chemokines with diverse functions were also elevated (P = 0.04) at day 3 (Fig. 6) and day 7 (Fig. 6B, C, F, and G) after injury in CCR2−/− compared with WT mice. KC-GRO (Fig. 6A), a potent neutrophil chemoattractant, was increased at day 3 (P = 0.04) in CCR2−/− compared with WT mice. Elevations (P ≤ 0.01) in IL-3, -4, and -7 occurred in CCR2−/− tissue. Chemoattractants for stem cells, such as SCF and SDF-1, were elevated (P ≤ 0.01) in CCR2−/− muscle compared with WT (Fig. 6E and F). Finally, oncostatin and TIMP-1 (Fig. 6G and H) were elevated at days 3 and 7 in CCR2−/− compared with WT muscle. Taken together, remarkably consistent patterns of cytokine/chemokine elevations in CCR2−/− injured/regenerating muscle were present despite decreases in tissue macrophages and in the presence of impaired and persistent muscle regeneration.

Figure 6. Diverse cytokine/chemokine elevations in young, male CCR2−/− mice compared with WT mice after CTX injury.

(A–H) Measurement of tissue cytokines/chemokines normalized to total protein in the anterior compartment of WT and CCR2−/− mice after CTX-induced injury for KC/GRO (A), IL-3 (B), IL-4 (C), IL-7 (D), SCF (E), SDF-1 (F), oncostatin (OSM) (G), and TIMP-1 (H). Data are presented as means ± sem; n = 4–8 mice/strain/time point. #P ≤ 0.04 WT vs. CCR2−/− mice at the corresponding time point.

DISCUSSION

Optimal skeletal muscle regeneration requires coordination of multiple, dynamic cellular and environmental components. Factors that include age, sex, and immune status can modify muscle regeneration. Our group [38] has shown the necessity of CCR2 expression on BM-derived cells and demonstrated the importance of immune cells, likely macrophages, to regeneration. However, the contribution of age and sex to skeletal muscle regeneration is controversial [2, 6, 7, 9, 10, 24]. The purpose of our study was to determine the effect of sex and aging on muscle regeneration and sarcopenia in the absence of CCR2. In addition, the current study also revealed intriguing alterations in inflammation and cytokines/chemokines present in regenerating skeletal muscle in CCR2−/− mice.

Differences previously noted with aging and between sexes in WT mice were altered or amplified in CCR2−/− mice. Old-age WT [2] and CCR2−/− mice exhibited sarcopenia in both sexes (Fig. 1A). On the one hand, even in the presence of sarcopenia in old mice, male WT mice had similar regenerated myofiber CSA until baseline fiber size was attained by day 28 after injury across all 3 age groups. On the other hand, the regenerated CSA of middle and old WT female mice was decreased compared with young females, with middle-age female mice being the only group that did not attain baseline fiber size by day 28. In contrast, CCR2−/− mice had comparable regenerated myofiber size in both sexes and all age groups, but only attained approximately one third to one half of baseline fiber size by day 28 (Fig. 1A). Thus, the sex-dependent differences in myofiber size with aging in female WT mice were not present in CCR2−/− animals. In other words, the regeneration defect of smaller myofibers after injury that was observed in young CCR2−/− male mice [3, 5] was present and not affected by sex or aging.

Consistent with WT mice [2, 4], female CCR2−/− mice had increased adipocyte area compared with males at all ages and postinjury time points (Fig. 1B); however, adipocyte area was markedly elevated in both sexes of CCR2−/− relative to WT mice after injury [2]. Another difference between WT and CCR2−/− was the ability to remodel regenerated tissue with a resultant decrease in adipocyte area. Young female and all 3 age groups of male WT mice were able to decrease adipocyte area over time, whereas middle- and old-age females retained adipocytes after injury [2]. Of interest, only young, male CCR2−/− mice had decreased adipocyte area over time, whereas fat was retained in middle and old males and all three age groups of females after injury (Fig. 1B). We previously reported greater adipocyte area in castrated compared with intact male WT mice [4]. CCR2 may be involved in sex hormone–related adipocyte changes that were observed in both sexes. This finding may be relevant to age-related decline in muscle function given that increased muscle fat content has been associated with diminished strength [50]. Mesenchymal FAPs differentiate into adipocytes after skeletal muscle injury [56, 57]. A recent finding has suggested macrophage regulation of FAPs. Infiltrating macrophage production of TNF-α induced FAP apoptosis, whereas production of TGF-β prevented apoptosis leading to fibrosis in injured skeletal muscle [58]. However, their proposed mechanism of FAP apoptosis mediated by TNF-α–expressing macrophages [58] is not as likely to occur in CCR2−/− mice as a result of impaired macrophage recruitment (Fig. 4). In addition, TNF-α was 4–6× higher in injured muscle of young, male CCR2−/− compared with WT mice (Fig. 5A), whereas TGF-β was not measured in our model. Of interest, MCP-1, which was also markedly elevated in CCR2−/− mice compared with WT (Fig. 5E), can promote expression of TGF-β [59]. Finally, the fat area in the chimera experiments suggested that the expression of CCR2 on either host or BM cells resulted in a phenotype similar to WT host controls (WT→WT), whereas lack of CCR2 on both compartments (CCR2−/−→CCR2−/−) resulted in increased fat area (Fig. 2B). Whereas a relationship between CCR2, macrophages, and adipogenesis is suggested by the current study, the regulatory mechanisms and functional outcomes in the context of sex and aging will require more in-depth studies.

Aging is a process that is associated with changes in body mass and composition [60, 61]. Body mass in young (3–6 mo) and old (24–32 mo) CCR2−/− mice were equivalent, with peak body mass observed in middle-age (11–15 mo) mice. This pattern was consistent with C57BL/6J WT mice [60]; however, reports of higher body masses in aged mice [62] seem contradictory until one considers the age ranges defined as aged. In Mirsoian et al. [62], aged mice were defined as 15–20 mo old, which was more consistent in both age and body mass with our middle-age mice. The careful definition of aging-related phenotypes, including body mass, is vital for understanding the interaction of genes, such as CCR2, and aging.

Until recently, age-related changes in muscle mass (sarcopenia) and regeneration (delayed/impaired) were thought to be the result of secondary satellite cell failure; however, Fry et al. [25] demonstrated that inducible satellite cell depletion resulted in impaired muscle regeneration but had no effect on sarcopenia. That regeneration and sarcopenia may be independent pathways was also observed in the current study. The anterior compartment weights of CCR2−/− mice progressively decreased with aging. In addition, when corrected with body weight, anterior compartment weights were diminished in middle and old mice compared with young mice. Consistent with our previous studies with WT C57BL/6J mice [2], CCR2−/− also demonstrated age-related decreased myofiber CSA at baseline, particularly in the old-age animals. Sarcopenia was evident on the basis of both weight (Table 1) and CSA (Fig. 1A). However, after CTX injury, CSA at each time point was comparable, which suggests no effect of age in CCR2-regulated deficits in myofiber CSA. Although satellite cells are important to regeneration [12–14, 19–23, 25, 63], whether satellite cell function is diminished with aging is controversial [8, 15, 18, 24], and the impact on regeneration is also unclear.

What CCR2 contributes to determining the final regenerated CSA is an interesting question. Given that age and sex did not affect regenerated myofiber size and that, even by day 84, the CSA of myofibers in young, male CCR2−/− mice was comparable to day 28, attaining approximately one third of baseline CSA (Table 4) suggests that regeneration was delayed and permanently impaired in that injured myofibers could not attain baseline size. This observation is especially intriguing given that MPCs isolated from CCR2−/− and WT young males had comparable proliferation and differentiation in culture (Fig. 3), which suggests that CCR2 expression was not essential on MPCs. In addition, WT BM transplanted into an irradiated CCR2−/− host (WT→CCR2−/−) exhibited similar regenerated myofiber CSA at day 28 compared with WT controls (WT→WT) despite the lack of CCR2 on MPCs, whereas CCR2−/− BM transplanted into WT host mice resulted in smaller myofiber size similar to CCR2 controls (CCR2−/−→CCR2−/−; Fig. 2A). The primary factors associated with regenerated myofiber CSA relate to the number of MPCs that fuse to form the myofiber and the cytoplasmic volume of each of those MPCs [64]. Therefore, the decreased regenerated myofiber CSA was not likely a result of a deficit in the regenerative potential of CCR2−/− MPCs and is likely secondary to macrophage recruitment defects or some other component related to BM-derived cells. Finally, baseline myofiber CSA in young CCR2−/− mice was larger (P ≤ 0.002) than that in WT in both sexes (male: WT 2628 ± 52 vs. CCR2−/− 2985 ± 88 μm2; female: WT 2024 ± 55 vs. CCR2−/− 2553 ± 46 μm2) [2]. The regulatory mechanisms that define myofiber target size are not understood. Clearly, other factors, including possibly macrophage recruitment, are essential to establishing a set point for myofiber size at baseline and after injury.

CCR2 expression in monocytes/macrophages is a proinflammatory marker [39]. Given that TLR signaling is a major pathway for initiating and maintaining proinflammatory cytokine production [52], we hypothesized that ablation of TLR signaling would result in impaired muscle regeneration similar to CCR2−/− mice. Surprisingly, knockouts of the primary adaptor proteins immediately downstream of TLR, MyD88−/−, and TRIF−/− resulted in comparable injury, CSA, fat area, and percent residual necrosis in injured muscle compared with WT young, male mice (Table 5). Knockout of TLR4 in the muscular dystrophy mouse model resulted in diminished proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in muscle [65]. TRIF−/− mice had similar regenerating CSA 1 wk after ischemic injury compared with controls, but elevated proinflammatory cytokine expression [53]. In contrast, muscle regeneration in MyD88−/− mice demonstrated mildly increased CSA compared with WT mice, with diminished proinflammatory cytokine expression [53]. Macrophages that were isolated from MyD88−/− mice did not produce proinflammatory cytokines in response to LPS; however, signaling via the NF-ΚB and MAPK pathways was intact [66]. Perhaps cell-to-cell communication mediates the necessary functions of macrophages in muscle regeneration or activation of alternative TLR-independent pathways may compensate for the lack of TLR signaling in our model of muscle regeneration in MyD88−/− and TRIF−/− mice.

Impaired macrophage recruitment in CCR2−/− mice has been previously reported [3, 67, 68] and is confirmed in the current study (Fig. 4). Consistent with our previous work [3], neutrophils remained elevated in injured muscle, and macrophages were markedly diminished in CCR2−/− compared with young, male WT mice. However, the distribution of Ly6C+ and Ly6C− monocytes/macrophages in CCR2−/− mice had not been explored. Ly6C in monocytes/macrophages is well established as a proinflammatory marker [31, 46, 55, 69]; therefore, we hypothesized that Ly6C+ cells would be absent/diminished in injured muscle of CCR2−/− mice. Of interest, monocytes in injured CCR2−/− muscle reached numbers similar to WT mice, albeit with delayed recruitment and a predominance of Ly6C− cells (Fig. 4C and E). In contrast, macrophage numbers were severely diminished in CCR2−/− mice, with almost absent Ly6C+ and greatly diminished Ly6C− cells (Fig. 4D and F), a pattern that is remarkably similar to early ablation of CD11+ cells [55]. Of interest, there is strong evidence that the source of Ly6C− macrophages is Ly6C+ macrophages [70], which suggests that a small population of Ly6C+ macrophages are capable of infiltrating the tissue and differentiating into Ly6C− macrophages. Nevertheless, the numbers of Ly6C− macrophages in CCR2−/− mice were only approximately one eighth of the maximal numbers observed in WT animals. Taken together with the impairments in muscle regeneration, our collective data strongly suggest that early macrophage recruitment is essential and that alterations in the progression of inflammatory cells results in long-term impairments of muscle regeneration.

The concomitant expression of CCR2 and Ly6C on early recruited monocytes/macrophages into injured tissue and atherosclerotic plaques has been documented by multiple groups [31, 71, 72]. CCR2 is more highly expressed on Ly6C+ than on Ly6C− monocytes/macrophages [71, 72], with increased production of proinflammatory mediators by CCR2+ or Ly6C+ monocytes/macrophages [67, 69]. Our data support the observations by other labs that CCR2 is necessary for Ly6C+ monocyte/macrophage recruitment to tissue [73], as the overwhelming predominance of monocytes/macrophages present in injured tissue in CCR2−/− mice were Ly6C− (Fig. 4). In contrast to the expected roles of CCR2 and Ly6C in tissue inflammation, our data suggest an exacerbation of tissue inflammatory response, possibly secondary to the severe impairments in macrophage recruitment as evidenced by elevated proinflammatory mediators in CCR2−/− tissue deficient of CCR2+/Ly6C+ monocytes/macrophages. Targeted ablation of monocytes/macrophages at different time points in muscle regeneration demonstrated that ablation at days 2 and 3 resulted in the most severe impairments in muscle regeneration [55]. Of interest, days 2 and 3 in control mice were associated with the transition of a predominance of Ly6C+ to Ly6C− macrophages. Furthermore, disruption of the proinflammatory TLR pathways had no measurable effect on muscle regeneration (Table 5). Altogether, this suggests that whereas CCR2 is important for monocyte/macrophage recruitment, CCR2 may not be essential for the function/polarization of the macrophages once at the site of injury.

Macrophages are a major source of many cytokines and as a result of the deficient recruitment of macrophages to injured muscle in CCR2−/− mice, we anticipated that proinflammatory cytokines would be severely depressed. Of interest, the general trend for many cytokines was marked elevations in CCR2−/− compared with WT mice (Figs. 5 and 6). Among the 28 cytokines and proteins that were measured in regenerating muscle, only 8 were significantly different at any time point (days 1, 3, and 7 after injury) between CCR2−/− and WT mice. Monocyte/macrophage numbers peaked in injured muscle by day 3 in WT animals (Fig. 4C and D). Therefore, it is interesting that the general pattern of cytokines elevated in the CCR2−/− mice commonly peaked at day 3, with significant increases at day 3 in all, and also at day 7 in many cytokines compared with WT mice (Figs. 5 and 6). Only 1 cytokine, MIP-2, was increased in WT compared with CCR2−/− mice and only on day 1 after injury (Fig. 5H). MIP-2 promotes neutrophil chemotaxis [74] and mobilizes hematopoietic progenitor cells [75]. Proinflammatory cytokines that were elevated in CCR2−/− muscle included TNF-α, IL-12p70, GM-CSF, MIP-1β, MCP-1, MCP-3, and MCP-5 (Fig. 5) [74]. Specifically, TNF-α elevations were present in injured/regenerating muscle of both animal models and in humans [21, 28]. Not surprisingly, chemokines that are responsible for monocyte chemotaxis—MCP-1, MCP-3, MCP-5, MIP-1β, IL-3, and GM-CSF—were markedly elevated in the macrophage-deficient CCR2−/− tissue [74].

In addition to proinflammatory cytokines, diverse cytokines were also elevated in CCR2−/− muscle (Fig. 6). Chemokines responsible for neutrophil (KC-GRO) and endothelial (IL-3 and GM-CSF) chemotaxis were elevated [74], which is consistent with the persistence of neutrophils in CCR2−/− muscle (Fig. 4B). One anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-4, was markedly increased in the CCR2−/− tissue, possibly as a counterbalance to the fulminant proinflammatory environment. Both SCF and SDF-1, which are important in hematopoietic stem cell chemotaxis and involved in homing hematopoietic stem cells return to the BM [76], were elevated in the CCR2−/− muscle. SCF also stimulates hematopoiesis [77] in concert with IL-3 + GM-CSF promotion of differentiation into the myeloid lineage [74], whereas IL-7 enhances differentiation into the lymphoid lineage [78]. Proangiogenic cytokines that were elevated in CCR2−/− tissue included KC-GRO, IL-3, and GM-CSF, with one antiangiogenic protein, TIMP-1 [74]. Taken together, in the absence of macrophage recruitment, many proinflammatory, proangiogenic, and prohematopoietic cytokines were markedly elevated in association with impaired muscle regeneration. Cellular sources of these proteins could include the retained neutrophils, endothelial cells, MPCs, fibroblasts, adipocytes, and FAPs. The specific contribution of each of these components of the microenvironment to the regeneration deficit will require further study.

An interesting aspect of the current study was the impaired macrophage recruitment, especially with regard to Ly6C+ proinflammatory monocytes/macrophages, in association with marked elevations of diverse cytokines in injured muscle from young CCR2−/− mice, which suggests that the injured/regenerating microenvironment was similar to inflammaging [26, 27] present in aging individuals. Given that regenerating myofiber CSA was comparable in young and old-age CCR2−/− mice, and that young, male CCR2−/− mice were unable to attain baseline myofiber size after injury, suggests that absence of a proinflammatory chemokine receptor caused an aging phenotype in young mice.

In summary, our results further support that muscle regeneration and sarcopenia are independent events. In addition, CCR2 expression on BM-derived cells, likely macrophages, was essential to muscle regeneration, independent of TLR signaling, aging, and sex. Decreased proinflammatory monocytes/macrophages actually resulted in a proinflammatory microenvironment, which suggests that inflammaging was present in young CCR2−/− mice.

AUTHORSHIP

D.W.M., A.C.R., H.W., M.D.W., J.T.W., and P.K.S. wrote the first drafts of sections of the manuscript. H.W. performed flow cytometry experiments. D.W.M., A.C.R., H.W., and Z.S. performed tissue cytokine experiments. Z.S. and J.T.W. performed chimera experiments. A.C.R., J.T.W., and L.P. performed histomorphometry. M.T.B. provided mice and expertise for TLR mouse experiments. M.D.W. performed MPC experiments. L.M.M. and P.K.S. developed the overall experimental design. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joel Michalek, Ph.D., and Ken Ouyang for expert assistance in performing statistical analyses for these studies. These studies were supported, in part, by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL074236 and HL110743), NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI095951), Nathan Shock Centers of Excellence in Basic Biology of Aging AG013319, and Veterans Administration Merit Review 1I01BX001186. Data was generated in the Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Facility, which is supported by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA), NIH National Cancer Institute P30-CA054174-20 (Cancer Therapy & Research Center at UTHSCSA) and UL1-TR001120 (Clinical and Translational Science Award).

Glossary

- BM

bone marrow

- CSA

cross-sectional area

- CTX

cardiotoxin

- FAP

fibrocyte/adipocyte progenitor

- GFP-Tg

GFP transgenic

- KC-GRO

keratinocyte-derived cytokine (aka KC or GROα)

- MPC

myogenic progenitor cell

- SCF

stem cell factor

- SDF-1

stromal cell–derived factor

- TA

tibialis anterior

- TIMP-1

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1

- TRIF

TIR (Toll/IL-1R) domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen Y., Melton D. W., Gelfond J. A., McManus L. M., Shireman P. K (2012) MiR-351 transiently increases during muscle regeneration and promotes progenitor cell proliferation and survival upon differentiation. Physiol. Genomics 44, 1042–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearing C. M., Melton D. W., Lei X., Hancock H., Wang H., Sarwar Z. U., Porter L., McHale M., McManus L. M., Shireman P. K (2015) Increased adipocyte area in injured muscle with aging and impaired remodeling in female mice. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 71, 992–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez C. O., McHale M. J., Wells J. T., Ochoa O., Michalek J. E., McManus L. M., Shireman P. K. (2010) Regulation of skeletal muscle regeneration by CCR2-activating chemokines is directly related to macrophage recruitment. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 299, R832–R842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McHale M. J., Sarwar Z. U., Cardenas D. P., Porter L., Salinas A. S., Michalek J. E., McManus L. M., Shireman P. K. (2012) Increased fat deposition in injured skeletal muscle is regulated by sex-specific hormones. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 302, R331–R339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ochoa O., Sun D., Reyes-Reyna S. M., Waite L. L., Michalek J. E., McManus L. M., Shireman P. K. (2007) Delayed angiogenesis and VEGF production in CCR2-/- mice during impaired skeletal muscle regeneration. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293, R651–R661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enns D. L., Tiidus P. M. (2008) Estrogen influences satellite cell activation and proliferation following downhill running in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 104, 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deasy B. M., Lu A., Tebbets J. C., Feduska J. M., Schugar R. C., Pollett J. B., Sun B., Urish K. L., Gharaibeh B. M., Cao B., Rubin R. T., Huard J. (2007) A role for cell sex in stem cell-mediated skeletal muscle regeneration: female cells have higher muscle regeneration efficiency. J. Cell Biol. 177, 73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee A. S., Anderson J. E., Joya J. E., Head S. I., Pather N., Kee A. J., Gunning P. W., Hardeman E. C. (2013) Aged skeletal muscle retains the ability to fully regenerate functional architecture. BioArchitecture 3, 25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conboy I. M., Conboy M. J., Wagers A. J., Girma E. R., Weissman I. L., Rando T. A. (2005) Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature 433, 760–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paliwal P., Pishesha N., Wijaya D., Conboy I. M. (2012) Age dependent increase in the levels of osteopontin inhibits skeletal muscle regeneration. Aging (Albany, N.Y.) 4, 553–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson B. M., Faulkner J. A. (1989) Muscle transplantation between young and old rats: age of host determines recovery. Am. J. Physiol. 256, C1262–C1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepper C., Partridge T. A., Fan C.-M. (2011) An absolute requirement for Pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 138, 3639–3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy M. M., Lawson J. A., Mathew S. J., Hutcheson D. A., Kardon G. (2011) Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development 138, 3625–3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambasivan R., Yao R., Kissenpfennig A., Van Wittenberghe L., Paldi A., Gayraud-Morel B., Guenou H., Malissen B., Tajbakhsh S., Galy A. (2011) Pax7-expressing satellite cells are indispensable for adult skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 138, 3647–3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sousa-Victor P., Gutarra S., García-Prat L., Rodriguez-Ubreva J., Ortet L., Ruiz-Bonilla V., Jardí M., Ballestar E., González S., Serrano A. L., Perdiguero E., Muñoz-Cánoves P. (2014) Geriatric muscle stem cells switch reversible quiescence into senescence. Nature 506, 316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth S. M., Martel G. F., Ivey F. M., Lemmer J. T., Metter E. J., Hurley B. F., Rogers M. A. (2000) Skeletal muscle satellite cell populations in healthy young and older men and women. Anat. Rec. 260, 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shefer G., Van de Mark D. P., Richardson J. B., Yablonka-Reuveni Z. (2006) Satellite-cell pool size does matter: defining the myogenic potency of aging skeletal muscle. Dev. Biol. 294, 50–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conboy I. M., Conboy M. J., Smythe C. M (2003) Notch-mediated restoration of regenerative potential to aged muscle. Science 302, 1575–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakkalakal J. V., Jones K. M., Basson M. A., Brack A. S. (2012) The aged niche disrupts muscle stem cell quiescence. Nature 490, 355–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Day K., Shefer G., Shearer A., Yablonka-Reuveni Z. (2010) The depletion of skeletal muscle satellite cells with age is concomitant with reduced capacity of single progenitors to produce reserve progeny. Dev. Biol. 340, 330–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barberi L., Scicchitano B. M., De Rossi M., Bigot A., Duguez S., Wielgosik A., Stewart C., McPhee J., Conte M., Narici M., Franceschi C., Mouly V., Butler-Browne G., Musarò A. (2013) Age-dependent alteration in muscle regeneration: the critical role of tissue niche. Biogerontology 14, 273–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alsharidah M., Lazarus N. R., George T. E., Agley C. C., Velloso C. P., Harridge S. D. R. (2013) Primary human muscle precursor cells obtained from young and old donors produce similar proliferative, differentiation and senescent profiles in culture. Aging Cell 12, 333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George T., Velloso C. P., Alsharidah M., Lazarus N. R., Harridge S. D. R. (2010) Sera from young and older humans equally sustain proliferation and differentiation of human myoblasts. Exp. Gerontol. 45, 875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grounds M. D. (2014) Therapies for sarcopenia and regeneration of old skeletal muscles: more a case of old tissue architecture than old stem cells. BioArchitecture 4, 81–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fry C. S., Lee J. D., Mula J., Kirby T. J., Jackson J. R., Liu F., Yang L., Mendias C. L., Dupont-Versteegden E. E., McCarthy J. J., Peterson C. A. (2015) Inducible depletion of satellite cells in adult, sedentary mice impairs muscle regenerative capacity without affecting sarcopenia. Nat. Med. 21, 76–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franceschi C., Bonafè M., Valensin S., Olivieri F., De Luca M., Ottaviani E., De Benedictis G. (2000) Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 908, 244–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minciullo P. L., Catalano A., Mandraffino G., Casciaro M., Crucitti A., Maltese G., Morabito N., Lasco A., Gangemi S., Basile G. (2016) Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: the role of cytokines in extreme longevity. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz.) 64, 111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Poel C., Gosselin L. E., Schertzer J. D., Ryall J. G., Swiderski K., Wondemaghen M., Lynch G. S. (2011) Ageing prolongs inflammatory marker expression in regenerating rat skeletal muscles after injury. J. Inflamm. (Lond.) 8, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merritt E. K., Stec M. J., Thalacker-Mercer A., Windham S. T., Cross J. M., Shelley D. P., Craig Tuggle S., Kosek D. J., Kim J.-S., Bamman M. M. (2013) Heightened muscle inflammation susceptibility may impair regenerative capacity in aging humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 115, 937–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauvau G., Chorro L., Spaulding E., Soudja S. M. (2014) Inflammatory monocyte effector mechanisms. Cell. Immunol. 291, 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geissmann F., Jung S., Littman D. R. (2003) Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 19, 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charo I. F., Taubman M. B. (2004) Chemokines in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. Circ. Res. 95, 858–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurihara T., Bravo R. (1996) Cloning and functional expression of mCCR2, a murine receptor for the C-C chemokines JE and FIC. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11603–11607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarafi M. N., Garcia-Zepeda E. A., MacLean J. A., Charo I. F., Luster A. D. (1997) Murine monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-5: a novel CC chemokine that is a structural and functional homologue of human MCP-1. J. Exp. Med. 185, 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shireman P. K., Contreras-Shannon V., Ochoa O., Karia B. P., Michalek J. E., McManus L. M. (2007) MCP-1 deficiency causes altered inflammation with impaired skeletal muscle regeneration. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81, 775–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shireman P. K., Contreras-Shannon V., Reyes-Reyna S. M., Robinson S. C., McManus L. M. (2006) MCP-1 parallels inflammatory and regenerative responses in ischemic muscle. J. Surg. Res. 134, 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Contreras-Shannon V., Ochoa O., Reyes-Reyna S. M., Sun D., Michalek J. E., Kuziel W. A., McManus L. M., Shireman P. K. (2007) Fat accumulation with altered inflammation and regeneration in skeletal muscle of CCR2-/- mice following ischemic injury. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C953–C967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun D., Martinez C. O., Ochoa O., Ruiz-Willhite L., Bonilla J. R., Centonze V. E., Waite L. L., Michalek J. E., McManus L. M., Shireman P. K. (2009) Bone marrow-derived cell regulation of skeletal muscle regeneration. FASEB J. 23, 382–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geissmann F., Manz M. G., Jung S., Sieweke M. H., Ley K (2010) Development of monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells. Science 327, 656–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartoli C., Civatte M., Pellissier J. F., Figarella-Branger D. (2001) CCR2A and CCR2B, the two isoforms of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor are up-regulated and expressed by different cell subsets in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 102, 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carulli M. T., Ong V. H., Ponticos M., Shiwen X., Abraham D. J., Black C. M., Denton C. P. (2005) Chemokine receptor CCR2 expression by systemic sclerosis fibroblasts: evidence for autocrine regulation of myofibroblast differentiation. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 3772–3782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]