Abstract

Some transplant programs consider the lack of health insurance as a contraindication to living kidney donation. Still, prior studies have shown that many adults are uninsured at time of donation. We extend the study of donor health insurance status over a longer time period and examine associations between insurance status and relevant sociodemographic and health characteristics. We queried the UNOS/OPTN registry for all living kidney donors (LKDs) between July 2004 and July 2015. Of the 53,724 LKDs with known health insurance status, 8,306 (16%) were uninsured at the time of donation. Younger (18 to 34 years old), male, minority, non-employed, less educated, non-married LKDs and those who were smokers and normotensive were more likely to not have health insurance at the time of donation. Compared to those with no health risk factors (i.e., obesity, smoking, hypertension, eGFR, proteinuria)(14%), LKDs with 1 (18%) or ≥2 (21%) health risk factors at the time of donation were more likely to be uninsured (P<0.0001). Among those with ≥2 health risk factors, blacks (28%) and Hispanics (27%) had higher likelihood of being uninsured compared to whites (19%; P<0.001). Study findings underscore the importance of providing health insurance benefits to all previous and future LKDs.

INTRODUCTION

While guidelines exist for the evaluation of living kidney donors (LKDs)[1,2], considerable variation persists in the surgical, medical, and psychosocial criteria used by transplant programs in the United States (U.S.) to determine donation eligibility. [3–6] One characteristic that remains controversial in determining donation eligibility is the presence or absence of health insurance in the potential LKD.[4–10] In a survey of U.S. kidney transplant programs, the lack of health insurance in the donor was an absolute and relative contraindication to donation in 15% and 42% of programs, respectively.[4]

Some programs may not require LKDs to have their own health insurance because the costs associated with the donation evaluation, surgery, hospitalization, follow-up and short-term complications are covered by the transplant recipient’s health insurance in most instances. Moreover, the incidence of donation-related consequences is relatively low [11–14] and requiring LKDs to have health insurance that they are likely to never activate for donation-related health concerns may be seen as overly restrictive, particularly if the LKD is willing to accept this risk. However, it has been shown that LKDs in the U.S. incur health care costs both before and after donation.[15,16] These may include costs for routine health screening that is necessary for donation evaluation but not covered by the recipient’s health insurance (e.g., mammogram, colonoscopy) and for evaluation and treatment of newly discovered health problems during the evaluation. Other potential healthcare costs may include outpatient appointments and laboratory testing to satisfy the donor follow-up regulatory requirements for two years after donation, rehabilitation services, and the evaluation and treatment of complications not covered by the recipient’s insurance.[10,16,17] It is recognized, of course, that health insurance status is not static for many adults in the United States – LKDs insured at the time of evaluation and donation may become uninsured in the two years following donation, while uninsured LKDs may subsequently acquire health insurance.[18]

Approximately 32% of kidney transplants in the U.S. are performed using kidneys from healthy living donors.[19] The number of LKDs in the United States peaked in 2004 and has declined in the last decade.[20] There were only 5,538 LKDs in 2015, which is 17% fewer than the 6,647 donors in 2004.[http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov] Considering the decline in LKDs in the context of increasing volume of transplant candidates, it is possible that transplant programs have become less stringent about the need for potential donors to have health insurance at the time of donation. Conversely, emerging data regarding the health care costs incurred by LKDs [15,16] and the policy changes requiring programs to report clinical follow-up data on their donors [1] may have triggered some programs to require health insurance at time of donation.

Health insurance trends in LKDs are an important topic of scientific inquiry. More than 36 million adults (10%) in the U.S. are uninsured.[21] The proportion of uninsured is highest in young adults (ages 19 to 34 years old), adults with low income, and African Americans, three groups that have seen a precipitous drop in the rate of living kidney donation in the last decade.[20] Moreover, those without health insurance are less likely to have an identified primary care physician, undergo routine healthcare screening, seek medical evaluation of new-onset physical symptoms and psychological distress, follow through with recommended care following a diagnosis of a chronic health condition, fill prescriptions, and live as long compared to those with health insurance.[22]

Gibney et al.[23] previously examined health insurance status of LKDs between July 2004 and September 2006 and found that 18% were uninsured at time of donation. Also, LKDs who were younger, male, and minorities had higher rates of being uninsured. In the current study, we sought to extend the prior work of Gibney et al.[23] by examining the temporal health insurance trends at the time of donation in LKDs between July 2004 and July 2015. Additionally, we examined whether LKD health insurance status was associated with sociodemographic, health, and donation characteristics.

METHODS

We obtained data from the UNOS/OPTN registry for all LKDs between July 2004 and July 2015. July 2004 was selected as the start point since health insurance status was not formally collected by the UNOS/OPTN prior to that date. The primary variable of interest was known LKD health insurance status at the time of donation. Transplant programs report only whether the donor has health insurance (“insured,” “uninsured,” or “unknown insurance status”), not the specific policy type. T tests and chi-square statistics were calculated to compare the characteristics of LKDs with known insurance status (i.e., insured or uninsured) to those with unknown insurance status. The latter group was then excluded from subsequent analyses.

Fisher exact and chi square tests were used to assess the relationship between LKD health insurance status and sociodemographic (age, sex, race/ethnicity, working status, education level, and marital status) and health (obesity, current smoking, hypertension, eGFR<60, and proteinuria) characteristics. A health risk score was calculated and we examined its relationship to health insurance status. The health risk score was the simple sum of five variables, the presence of each at the time of donation, yielding 1 point for a score ranging from 0 to 5. The five variables were obesity (BMI>30 kg/m2), cigarette smoking, hypertension, eGFR<60, and proteinuria (positive urine protein by dipstick). eGFR was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.[24] We also examined the association between health insurance status and UNOS region, as well as for any differences in health insurance status between the non-elderly (<65 yrs old) adult general population [22] and LKDs in each UNOS region. Next, we studied whether health insurance status predicted likelihood of having serum creatinine (SCr) in the UNOS/OPTN registry at the 6, 12, and 24 month follow-up assessments, controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, working status, education level, and marital status. Finally, we conducted secondary analyses to examine the relationship between health insurance status and donation events that occurred within the first 6 weeks following surgery, including laparoscopic to open nephrectomy conversion, re-operation, hospital readmission, complications requiring intervention, and new-onset hypertension.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS (Chicago, IL). To reduce the likelihood of Type I error rate associated with very large samples and multiple comparisons, statistical significance was set at P<0.001. We received a determination of exempt status from the Committee on Clinical Investigation at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Protocol #2015P-000373).

RESULTS

There was a total of 66,987 LKDs between July 2004 and July 2015. We excluded LKDs who were <18 years old (n=4), did not reside in the U.S. (n=573), and whose health insurance status was unknown (n=12,686), resulting in a final sample of 53,724 LKDs. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic, health status, and donation characteristics of this cohort. Mean age was 41.8 (±11.5) years and the majority was female (61%), non-Hispanic white (71%), employed (81%), married (63%), had more than a high school education (73%), and biologically related to the recipient (55%). LKDs excluded due to unknown insurance status were more likely to be younger, male, black, have less than college education, and obese than those with known health insurance status (P values <0.0001).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, health, and donation characteristics of living kidney donors (LKDs) with known health insurance status at time of donation, United States, July 2004 to July 2015, N = 53,724

| Characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Age | ||

| 18 to 34 yrs | 15,752 | (29) |

| 35 to 49 yrs | 23,349 | (44) |

| 50 to 64 yrs | 13,595 | (25) |

| ≥65 yrs | 1,028 | (2) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 32,872 | (61) |

| Male | 20,852 | (39) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 38,204 | (71) |

| Black | 6,065 | (11) |

| Hispanic | 6,971 | (13) |

| Asian | 1,791 | (3) |

| Other (American Indian, Pacific Islander, Multiracial) | 693 | (2) |

| Working for income | 43,503 | (81) |

| Highest education | ||

| No high school diploma or equivalent | 963 | (2) |

| High School diploma or equivalent | 13,527 | (25) |

| Attended college | 13,442 | (25) |

| College degree | 14,129 | (26) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 6,203 | (12) |

| Unknown | 5,460 | (10) |

| Married or life partner | 33,827 | (63) |

| Health (at time of donation) | ||

| Health insurance, yes | 45,418 | (84) |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 11,597 | (22) |

| Cigarette smoker | 5,075 | (9) |

| Hypertension | 1,449 | (3) |

| eGFR <60 | 1,370 | (3) |

| Proteinuria | 2,044 | (4) |

| Donation | ||

| Relationship to recipient | ||

| Biological | 29,412 | (55) |

| Spouse/Life partner | 7,167 | (13) |

| Non-biological | 17,145 | (32) |

| UNOS region | ||

| 1 (CT, ME, MA, NH, RI, VT) | 3,067 | (6) |

| 2 (DE, DC, MD, NJ, PA, WV, VA) | 6,856 | (13) |

| 3 (AL, AR, FL, GA, LA, MS, PR) | 5,088 | (10) |

| 4 (OK, TX) | 3,924 | (7) |

| 5 (AZ, CA, NV, NM, UT) | 8,270 | (15) |

| 6 (AK, HI, ID, MT, OR, WA) | 1,870 | (5) |

| 7 (IL, MN, ND, SD, WI) | 6,085 | (11) |

| 8 (CO, IA, KS, MO, NE, WY) | 3,289 | (6) |

| 9 (NY, VT) | 4,893 | (9) |

| 10 (IN, MI, OH) | 5,891 | (11) |

| 11 (KY, NC, SC, TN, VA) | 3,977 | (7) |

| Unknown | 514 | (1) |

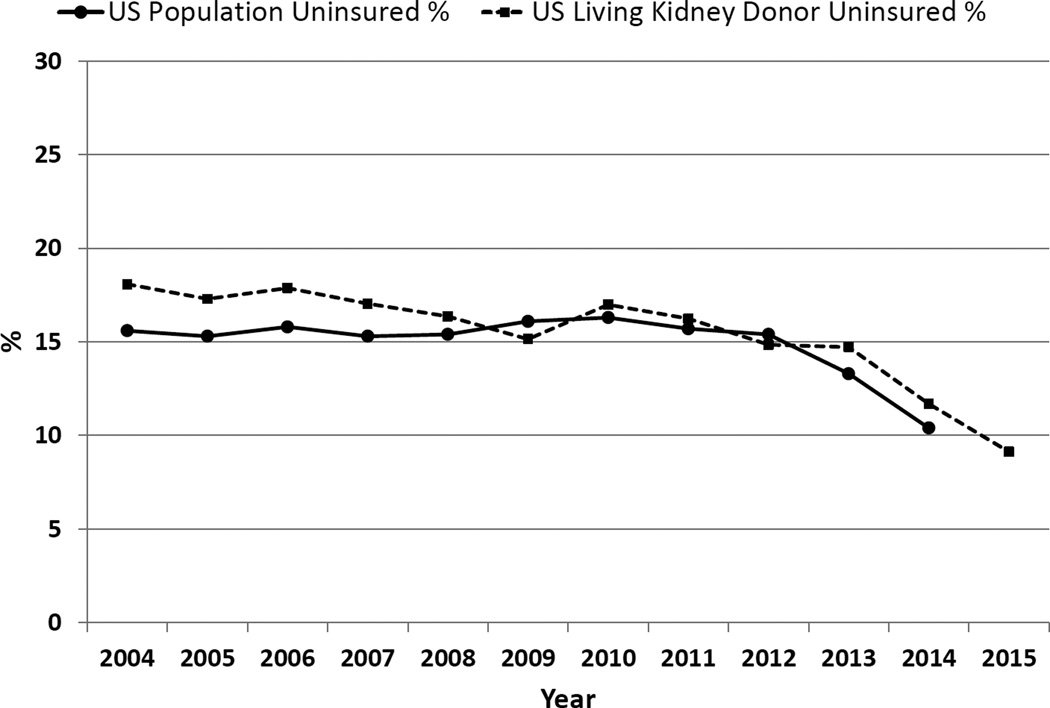

Of the 53,724 LKDs in the analysis cohort, 8,306 (16%) did not have health insurance at the time of donation. Figure 1 depicts the percentage of uninsured LKDs from 2004 to 2015, in comparison to the general U.S. non-elderly adult population. From 2004 to 2008, the percentage of uninsured LKDs was higher than that seen in the general adult population; however, the percentage of uninsured in these two populations is now essentially equivalent (9% and 10%, respectively). Importantly, there has been a downward trajectory of uninsured LKDs over time, decreasing from 18% in 2004 to 9% in 2015, which mirrors a similar decline in the general population (16% in 2004 to 10% in 2015).

Figure 1.

Percentage of uninsured living kidney donors (LKDs) and U.S. adult population from 2004 to 2015.

Univariable analyses found significant associations between health insurance status and LKD age, sex, race/ethnicity, employment status, education, marital status, smoking status, and hypertension (P values < 0.0001) (Table 2). Younger (18 to 34 years old), male, minority, non-employed, less educated, and non-married LKDs were more likely to not have health insurance at the time of donation. Also, LKDs who were cigarette smokers and normotensive were less likely to be insured.

Table 2.

Univariable associations between living kidney donor (LKD) health insurance status at time of donation and sociodemographic, health, and donation characteristics, United States, July 2004 to July 2015, N = 53,724

| Characteristics | Health Insurance Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninsured (n=8,306) |

Insured (45,418) |

|||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age | P<0.0001 | |||

| 18 to 34 yrs | 3,699 | (44) | 12,053 | (27) |

| 35 to 49 yrs | 3,231 | (39) | 20,118 | (44) |

| 50 to 64 yrs | 1,335 | (16) | 12,260 | (27) |

| ≥65 yrs | 41 | (1) | 987 | (2) |

| Sex | P<0.0001 | |||

| Female | 4,606 | (55) | 28,266 | (62) |

| Male | 3,700 | (45) | 17,152 | (38) |

| Race/Ethnicity | P<0.0001 | |||

| White | 4,525 | (55) | 33,679 | (75) |

| Black | 1,230 | (15) | 4,835 | (11) |

| Hispanic | 2,061 | (25) | 4,910 | (11) |

| Asian | 355 | (4) | 1,436 | (3) |

| Other (American Indian, Pacific Islander, Multiracial) | 47 | (1) | 200 | (1) |

| Working for income | P<0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 5,537 | (70) | 37,966 | (86) |

| No | 2,336 | (30) | 6,159 | (14) |

| Education | P<0.0001 | |||

| ≤High school diploma (or equivalent) | 3,730 | (50) | 10,760 | (26) |

| College education/college or graduate degree | 3,761 | (50) | 30,013 | (74) |

| Married or life partner | P<0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 3,669 | (45) | 30,158 | (68) |

| No | 4,427 | (55) | 14,393 | (32) |

| Health | ||||

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | P=0.004 | |||

| Yes | 1,886 | (24) | 9,711 | (22) |

| No | 6,068 | (76) | 33,941 | (78) |

| Cigarette smoker | P<0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 1,401 | (19) | 3,674 | (9) |

| No | 6,117 | (81) | 38,223 | (91) |

| Hypertension | P<0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 104 | (1) | 1,345 | (3) |

| No | 8,073 | (99) | 43,698 | (97) |

| eGFR <60 | P=0.70 | |||

| Yes | 206 | (2) | 1,164 | (3) |

| No | 8,100 | (98) | 44,254 | (97) |

| Proteinuria | P=0.32 | |||

| Yes | 333 | (4) | 1,711 | (4) |

| No | 7,251 | (96) | 39,574 | (96) |

| Number of health risk factors | P<0.0001 | |||

| None | 5,123 | (62) | 31,115 | (69) |

| 1 | 2,780 | (33) | 12,764 | (28) |

| ≥2 | 403 | (5) | 1,532 | (3) |

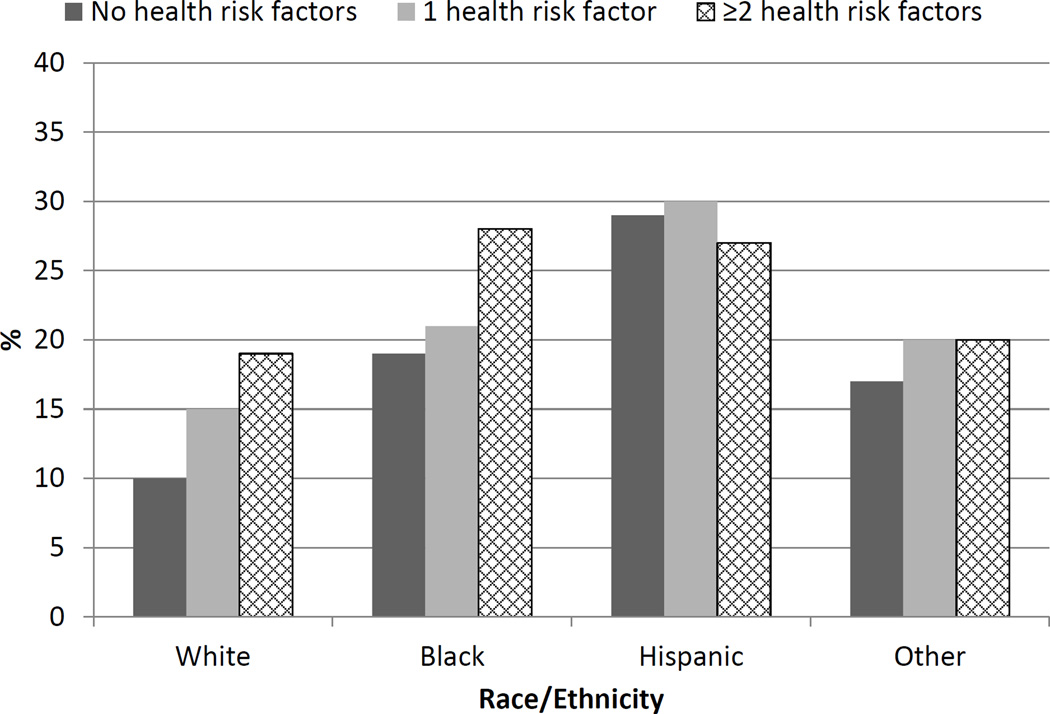

LKDs were categorized as having 0, 1, or ≥2 health risk factors at time of donation. Only 75 LKDs (<1%) had 3 or more health risk factors, so they were combined with those with 2 risk factors for purposes of analysis. Health risk factors included obesity, cigarette smoking, hypertension, eGFR<60, and proteinuria at time of donation. Compared to those with no health risk factors (14%), higher percentages of LKDs with 1 (18%) or ≥2 (21%) health risk factors at the time of donation were uninsured (P<0.0001). Among those with ≥2 health risk factors, blacks (28%) and Hispanics (27%) had higher likelihood of being uninsured compared to whites (19%; P<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of uninsured living kidney donors (LKDs) by race/ethnicity and number of health risk factors at time of donation. Health risk factors include obesity, hypertension, smoking, eGFR<60, and proteinuria.

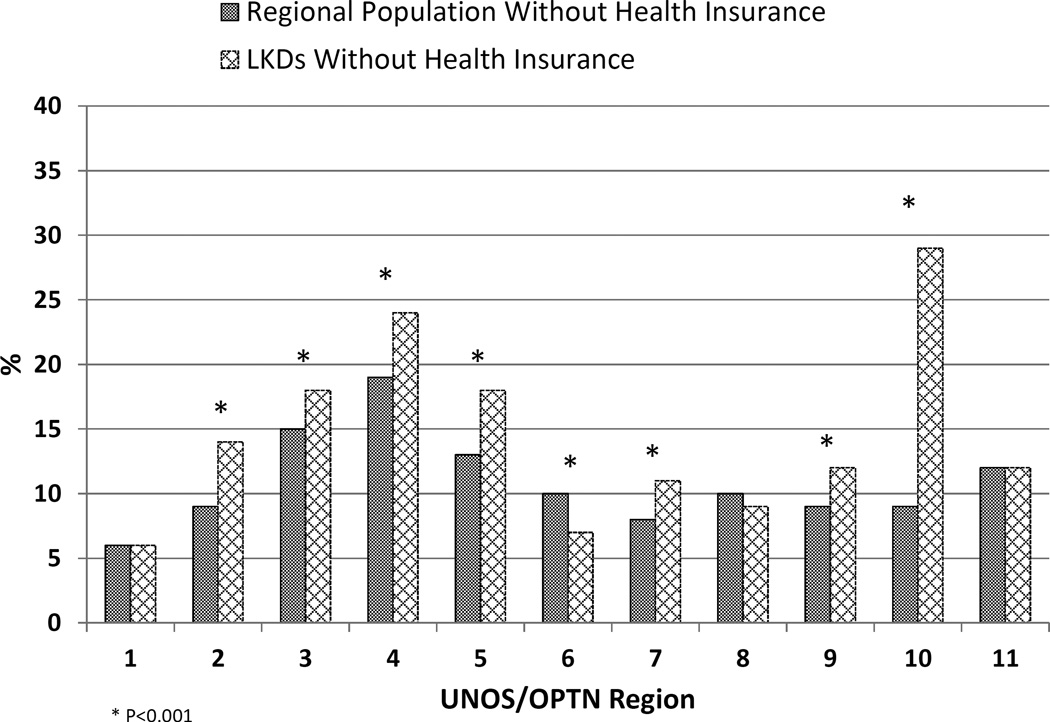

There were regional variations in the percentage of LKDs without health insurance (Figure 3). Regions 10 (IN, MI, OH) and 4 (OK, TX) had the highest percentage of LKDs without health insurance (29% and 24%, respectively), while regions 1 (CT, ME, MA, NH, RI, VT) and 6 (AK, HI, ID, MT, OR, WA) had the fewest uninsured donors (5% and 6%, respectively). Compared to the general non-elderly adult population within region, the percentage of uninsured LKDs was significantly higher in 7 of the 11 UNOS regions (2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, and 10). Only region 6 had significantly fewer uninsured LKDs relative to the general adult population in that region (7% vs. 10%).

Figure 3.

Percentage of uninsured living kidney donors (LKDs) and U.S. adult population by UNOS/OPTN region.

Controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, working status, education level, and marital status, having health insurance at the time of donation predicted higher likelihood of having SCr recorded in the UNOS/OPTN registry at the 6 month (OR=1.12, 95% CI=1.06, 1.19, P<0.001), 12 month (OR=1.09, 95% CI=1.03, 1.15, P=0.002), and 24 month (OR=1.12, 95% CI=1.06, 1.19, P<0.001) follow-ups.

Among LKDs (n=1,235) with a hospital readmission in the first 6 weeks after discharge, 236 (19%) were uninsured (vs. 15% of those who did not have a readmission, P<0.001). Of the readmissions among uninsured LKDs, the most common reasons were wound infection (10%), bowel obstructions (8%), fever (3%), vascular complications (1%), and other complications (70%; e.g., abdominal pain, dehydration, nausea and vomiting, pain, urinary tract infection). Uninsured LKDs did not have significantly higher rates of conversion from laparoscopic to open nephrectomy, re-operation, complications requiring intervention, or new-onset hypertension within the first 6 weeks following donation (P values >0.05).

We also examined whether health insurance status was associated with the occurrence of complications or hospital readmissions related to donation, new-onset hypertension requiring medication, or positive urine protein between the 6 week and 2 year follow-up assessments. Among LKDs (n=3,328) with proteinuria at any point during the two year follow-up period, 555 (17%) were uninsured (vs. 15% of those who did not have proteinuria, P<0.04). Also, among those (n=1,038) with newly diagnosed hypertension at any point during the two year follow-up period, 123 (12%) were uninsured (vs. 16% of those who did not have hypertension, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

In the United States, 16% of LKDs in the last decade lacked health insurance at the time of donation, which is comparable to the percentage of uninsured adults in the general non-elderly adult population (15%).[22] This suggests that the uninsured are not over-represented among LKDs relative to their proportion in the general population, thereby not assuming a higher than expected living donation burden. Also, the percentage of uninsured LKDs has steadily declined in recent years, for which there may be several explanations. First, there may be an increased reluctance on the part of transplant programs to accept uninsured donors. More than half of kidney transplant programs surveyed in the U.S. viewed the lack of health insurance as an absolute or relative contraindication to donation.[4] However, it is unknown whether those survey findings from a decade ago reflect current donor eligibility criteria and selection practices. Second, changing LKD demographics may account for this decline in uninsured donors. since the peak volume in 2004, living kidney donation has decreased by 30% in younger (<35 years old) adults and increased by 35% in those 50 years old and older.[38] A shift toward older donors who are more likely to be insured may also account for the overall change in health insurance coverage among LKDs. Third, changing health insurance patterns in the U.S. might also be a contributing factor to what we are observing in LKDs. For instance, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has contributed to a decrease in non-elderly adults without health insurance, since its marketplace enrollment began in October 2013. Compared to the two years prior, the percentage of LKDs without insurance dropped from 15% to 11% in the two years after ACA marketplace enrollment began.

Despite the favorable decline in the percentage of uninsured LKDs, the lack of health insurance in 16% of LKDs (or even 9% of LKDs, if examining 2015 data only) represents an “at-risk” population of several hundred donors per year in the U.S.. Living donation in the absence of health insurance may cause additional financial hardship for LKDs who may incur healthcare expenses that are not covered by the recipient’s health insurance policy.[15–17] Additionally, donation may adversely impact the LKD’s future health insurability. Boyarsky et al.[25] found that 7% of LKDs reported problems changing or initiating health insurance after donation. Others have reported a smaller percentage of LKDs being denied health insurance [18,26], but its occurrence can have downstream social, financial, and health consequences for donors. While ACA made it illegal for insurance companies to refuse health insurance to those with pre-existing conditions (including LKDs) beginning January 1, 2014,[27] there is the possibility that the ACA – or some of its components – may be repealed in the future.[28] The lack of health insurance at the time of donation also may affect compliance with follow-up for the two years required by UNOS/OPTN and beyond. Consistent with data reported by Schold et al.[29], we found that uninsured adults at time of donation were less likely to have 6, 12, and 24 month SCr values reported in the UNOS/OPTN database. Failure to attend to required follow-up poses risk for both the donor (i.e., lack of health assessment) and transplant program (i.e., failure to meet minimum thresholds for donor follow-up and probationary disposition).[1] Improved donor follow-up care is a unifying call to action within the transplant community[8,29–33]; however, a standardized approach for how to deliver (and pay for) such care to uninsured LKDs is lacking.

Perhaps most troubling is our finding that LKDs with two or more health risk factors (i.e., medically complex donors) are less likely to have insurance at the time of donation compared to those with no risk factors. Donors with obesity, hypertension, cigarette smoking, low eGFR, and/or proteinuria at time of donation are at highest need for consistent insurance coverage to facilitate routine monitoring in the months and years following donation. However, laboratory and provider fees for routine surveillance may be prohibitive for those without insurance. Indeed, lack of health insurance has been shown to be a barrier to accessing healthcare, associated with poorer health outcomes, and a risk factor for premature death from preventable causes in the general population.[21,22,34,35] In the context of emerging long-term outcomes for LKDs [36,37], accepting uninsured medically complex LKDs raises critical ethical questions about donor eligibility criteria.

Racial/ethnic minority LKDs were less likely than whites to have insurance. While this same disparity exists in the general population, we were surprised to find that minority LKDs had a substantially higher rate of being uninsured relative to general population rates within their own race/ethnicity (20% vs. 13% for blacks, 30% vs. 21% for Hispanics).[21] Also, we found that the percentage of uninsured blacks and Hispanics with two or more health risk factors is much higher than for uninsured whites with the same health risk factors. Living kidney donation in minorities, particularly blacks, has declined sharply in recent years, further exacerbating disparities in rates of live donor kidney transplantation.[20,38,39] Minorities are likely to have more medical issues that excluded them from living donation, yielding fewer eligible potential donors for minority transplant candidates. Thus, it is possible that some programs are more willing to accept uninsured minority donors, even those with medical complexities, knowing that the transplant candidate of the same minority race is likely to have few viable options for live donor kidney transplantation. This may explain some of the regional variations observed in this study, with particularly large percentages of uninsured LKDs in those regions with higher black and Hispanic representation on the transplant waiting list.

Study findings have educational, research, and policy implications. We recommend that programs inform potential LKDs of the specific risks they incur by proceeding to donation without health insurance. Current regulations simply require programs to inform potential LKDs that donation may make it more difficult to obtain or maintain health insurance in the future and that health problems related to donation may not be covered by the donor's current or future health insurance.[1] Potential LKDs should be informed of the likely out-of-pocket costs they will incur for health maintenance, medications, regulatory surveillance laboratory testing and provider visits, and downstream complications related to donation. Prospective research is needed to better understand the outcomes of uninsured LKDs. While certainly valuable, most of what we know now about long-term living donation outcomes comes from databases populated only by insured donors.[8,40] Future living donor registries, such as the 10-year follow-up registry recommended by the Advisory Committee on Transplantation [41], should ensure that donor health insurance status is captured at all assessments, which would facilitate more comprehensive study of insurance stability/instability and its association with outcomes over time. Finally, Newell et al.[8] recently proposed providing uninsured donors with health insurance, or paying the premiums of those with insurance, to facilitate the acquisition of important health information following donation. Considering our finding that uninsured donors are less likely to have clinical surveillance data available, we believe such a program would enable the transplant community to better track donor outcomes over time, engage donors in routine health maintenance, and promote appropriate use of healthcare services.

While our study benefits from the large number of living donors in the UNOS/OPTN database, our findings and conclusions are necessarily limited by the extent of missing data. Health insurance status was missing for 19% of LKDs. Younger, male, black, and less educated donors were disproportionately represented in this group for whom insurance status was unknown. However, future studies should be enabled by more robust reporting of health insurance status (i.e., health insurance status available for 96% of LKDs in 2014 vs. only 61% in 2004). Another important limitation of the database is that health insurance status is captured only at the time of donation and changes in status – and its relationship to sociodemographic characteristics and outcomes – after donation are unknown.

In conclusion, a small but significant percentage of LKDs do not have health insurance at time of donation. While evaluation and treatment of short-term donation-related complications and surveillance testing may be covered by the recipient’s health insurance, LKDs who remain uninsured following donation may be at risk for higher financial impact if complications occur. Particularly troubling is that lack of insurance is more common in LKDs with known health disparities (e.g., minorities, least educated) and those who have two or more pre-existing health risk factors (e.g., obesity, smoking, hypertension, low eGFR, proteinuria). Data from this study should be considered in discussions regarding the provision of health insurance benefits to previous and future LKDs in the U.S.[8,10,23,42,43]

Acknowledgments

The project described is supported by Award Number R01DK085185 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. This research was also supported, in part, by the Julie Henry Research Fund, the Center for Transplant Outcomes and Quality Improvement, and Surgical Outcomes Analysis & Research (SOAR), Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA. Also, this work was supported, in part, by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C.

Abbreviations

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- eGFR

estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate

- LKD

Living Kidney Donor

- MDRD

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- SCr

Serum Creatinine

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- US

United States

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER

The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

REFERENCES

- 1.OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network)/UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) OPTN Policies, Policy 14: Living Donation. [Accessed on February 02, 2016]; http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/ContentDocuments/OPTN_Policies.pdf.

- 2.Dew MA, Jacobs CL, Jowsey SG, Hanto R, Miller C, Delmonico FL United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS); American Society of Transplant Surgeons; American Society of Transplantation. Guidelines for the psychosocial evaluation of living unrelated kidney donors in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1047–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Danovitch GM, Johnson SR, Karp SJ, Khwaja K, Hanto DW, Rodrigue JR. The medical evaluation of living kidney donors: a survey of US transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2333–2343. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigue JR, Pavlakis M, Danovitch GM, Johnson SR, Karp SJ, Khwaja K, Hanto DW, Mandelbrot DA. Evaluating living kidney donors: relationship types, psychosocial criteria, and consent processes at US transplant programs. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2326–2332. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiessen C, Kim YA, Formica R, Bia M, Kulkarni S. Written informed consent for living kidney donors: practices and compliance with CMS and OPTN requirements. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2713–2721. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M. Living donor practices in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19:212–219. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dew MA, Jacobs CL. Psychosocial and socioeconomic issues facing the living kidney donor. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19:237–243. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newell KA, Formica RN, Gill JS. Engaging living kidney donors in a new paradigm of postdonation care. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:29–32. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibney EM. Lifetime insurance benefit for living donors: Is it necessary and could it be coercive? Am J Transplant. 2016;16:7–8. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tushla L, Rudow DL, Milton J, Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Hays R. Living-donor kidney transplantation: Reducing financial barriers to live kidney donation – Recommendations from a Consensus Conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1696–1702. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lentine KL, Lam NN, Axelrod D, Schnitzler MA, Garg AX, Xiao H, et al. Perioperative complications after living kidney donation: A national study. Am J Transplant. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13687. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lentine KL, Patel A. Risks and outcomes of living donation. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19:220–228. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schold JD, Goldfarb DA, Buccini LD, Rodrigue JR, Mandelbrot DA, Heaphy EL, et al. Comorbidity burden and perioperative complications for living kidney donors in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1773–1782. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12311212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemens KK, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Parikh CR, Yang RC, Karley ML, Boudville N, et al. Psychosocial health of living kidney donors: A systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2965–2977. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, et al. Predonation direct and indirect costs incurred by adults who donated a kidney: Findings from the KDOC Study. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2387–2393. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, et al. Direct and indirect costs following living kidney donation: Findings from the KDOC Study. Am J Transplant. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13591. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke KS, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, Yang RC, Garg AX Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network. The direct and indirect economic costs incurred by living kidney donors-a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1952–1960. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodrigue JR, Vishnevsky T, Fleishman A, Brann T, Evenson AR, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA. Patient-reported outcomes following living kidney donation: A single center experience. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2015;22:160–168. doi: 10.1007/s10880-015-9424-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Gustafson SK, Stewart DE, Cherikh WS, et al. Kidney (OPTN/SRTR annual data report) Am J Transplant. 2016;16(Suppl 2):11–46. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Mandelbrot DA. The decline in living kidney donation in the United States: random variation or cause for concern? Transplantation. 2013;96:767–773. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318298fa61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JC, Medalia C. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2015. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Key facts about the uninsured population. [Accessed February 13, 2016]; http://kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibney EM, Doshi MD, Hartmann EL, Parikh CR, Garg AX. Health insurance status of US living kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:912–916. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07121009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb EJ, Tomson CR, Roderick PJ Clinical Sciences Reviews Committee of the Association for Clinical Biochemistry. Estimating kidney function in adults using formulae. Ann Clin Biochem. 2005;42:321–345. doi: 10.1258/0004563054889936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyarsky BJ, Massie AB, Alejo JL, Van Arendonk KJ, Wildonger S, Garonzik-Wang JM, et al. Experiences obtaining insurance after live kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:2168–2172. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs CL, Gross CR, Messersmith EE, Hong BA, Gillespie BW, Hill-Callahan P, et al. Emotional and financial experiences of kidney donors over the past 50 years: The RELIVE Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:2221–2231. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07120714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Affordable Care Act: Read the law. [Accessed February 9, 2016]; Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/law/index.html.

- 28.Béland D, Rocco P, Waddan A. Implementing health care reform in the United States: intergovernmental politics and the dilemmas of institutional design. Health Policy. 2014;116:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schold JD, Buccini LD, Rodrigue JR, Mandelbrot D, Goldfarb DA, Flechner SM, et al. Critical factors associated with missing follow-up data for living kidney donors in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2394–2403. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Living Kidney Donor Follow-Up Conference Writing Group. Leichtman A, Abecassis M, Barr M, Charlton M, Cohen D, Confer D, et al. Living kidney donor follow-up: state-of-the-art and future directions, conference summary and recommendations. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2561–2568. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis CL. Living kidney donor follow-up: state-of-the-art and future directions. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19:207–211. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Karp SJ, Johnson SR, Hanto DW, Rodrigue JR. Practices and barriers in long-term living kidney donor follow-up: a survey of U.S. transplant centers. Transplantation. 2009;88:855–860. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b6dfb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dew MA, Olenick D, Davis CL, Bolton L, Waterman AD, Cooper M. Successful follow-up of living organ donors: strategies to make it happen. Prog Transplant. 2011;21:94–96. doi: 10.1177/152692481102100202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadley J. Sicker and poorer—the consequences of being uninsured: a review of the research on the relationship between health insurance, medical care use, health, work, and income. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(Suppl):3S–75S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703254101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeman JD, Kadiyala S, Bell JF, Martin DP. The causal effect of health insurance on utilization and outcomes in adults: a systematic review of US studies. Med Care. 2008;46:1023–1032. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318185c913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311:579–586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, et al. Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int. 2014;86:162–167. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodrigue JR, Kazley AS, Mandelbrot DA, Hays R, LaPointe Rudow D, Baliga P. Living donor kidney transplantation: Overcoming disparities in live kidney donation in the US--Recommendations from a Consensus Conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1687–1695. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00700115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purnell TS, Xu P, Leca N, Hall YN. Racial differences in determinants of live donor kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1557–1565. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:724–732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Advisory Committee on Organ Transplantation Recommendation 49. [Accessed February 15, 2016]; Available from: http://organdonor.gov/legislation/acotrecs4749.html.

- 42.Gaston RS, Danovitch GM, Epstein RA, Kahn JP, Matas AJ, Schnitzler MA. Limiting financial disincentives in live organ donation: a rational solution to the kidney shortage. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2548–2555. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis CL, Cooper M. The state of U.S. living kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1873–1880. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01510210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]