Abstract

In chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, one of the most common mutations to the virus occurs at amino acid 97 of the core protein, where leucine replaces either phenylalanine or isoleucine, depending on strain. This mutation correlates with changes in viral nucleic acid metabolism and/or secretion. We hypothesize that this phenotype is due in part to altered core assembly, a process required for DNA synthesis. We examined in vitro assembly of empty HBV capsids from wild-type and F97L core protein assembly domains. The mutation enhanced both the rate and extent of assembly relative to those for the wild-type protein. The difference between the two proteins was most obvious in the temperature dependence of assembly, which was dramatically stronger for the mutant protein, indicating a much more positive enthalpy. Since the structures of the mutant and wild-type capsids are essentially the same and the mutation is not involved in the contact between dimers, we suggest that the F97L mutation affects the dynamic behavior of dimer and capsid.

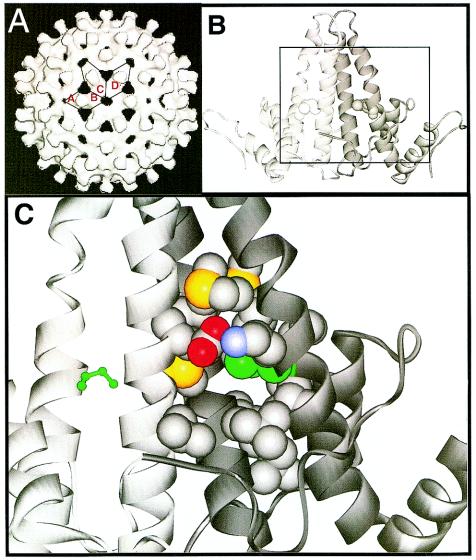

The capsid of hepatitis B virus (HBV), the protein shell of the virus core, plays vital roles in nucleic acid replication and intracellular transport (2, 3, 12, 14, 17, 18, 21, 27, 29). In vivo, the predominant form of the capsid is an ∼30-nm particle (24), corresponding to a T=4 icosahedron constructed from 240 copies of the core protein (Cp), arranged as 120 dimers (9). The full-length Cp is 183 residues long, of which the N-terminal 149 residues are the assembly domain (4, 33, 39), referred to as Cp149-wt in this paper. Cp dimers are the fundamental subunit of assembly (16, 22, 33, 39). In Cp149-wt, dimers are held together by a four-helix bundle with two helices from each half dimer (6, 8, 34). This four-helix bundle forms the spikes that decorate the surface of HBV (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Residue 97 is largely buried in the middle of the HBV Cp dimer interface. (A) Surface representation of a T=4 HBV capsid shows 120 spikes (reproduced with permission from the publisher of reference 43). The spikes are formed by the four-helix bundle (B) at the dimer interface. Residue 97, located in the middle of the spike, is remote from the sites of interaction with other subunits (around the C-terminal peptide, to the right and left of the illustration) and nucleic acid (interior base of the four-helix bundle). Coordinates are from the crystal structure of a T=4 capsid of the ayw strain of HBV (34); residue I97 is shown as a space-filling model. (C) The amino acids surrounding I97 (boxed area in panel B) are shown in greater detail. I97 (green) is surrounded by hydrophobic residues (V27, L31, L55, I59, C61, W62, M93, G94, L100, and L101); an exterior edge of the pocket is bordered by a salt bridge between E64 and K94. The β methyl of isoleucine (also in strains adr and adw) or the bulk of phenylalanine (in strains adyw and ady) at position 97 probably constrains movement of the side chain within the pocket (or, conversely, constrains movement of the pocket). However, leucine at position 97 would be expected to have greater freedom of movement. Backbone atoms are not shown, carbon atoms are gray, nitrogen atoms are blue, oxygen atoms are red, and sulfur atoms are yellow. The ribbon diagram was prepared with WebLab (Molecular Simulations, Inc., San Diego, Calif.).

Mutation of amino acid 97 to leucine, one of the most common mutations of the core protein seen in chronic infections (13), has been found to affect nucleic acid metabolism (26, 35-37). Depending on the strain of HBV, residue 97 is phenylalanine (e.g., ayw and adyw) or isoleucine (e.g., adr and adw). In tissue culture studies with both F97L and I97L mutants, a substantial fraction of secreted capsid particles contained single-stranded DNA, instead of the mature form of the genome (36, 37). In the Huh7, but not the HepG2, cell line I97L correlates with increased replication compared to that of the wild-type virus (26).

Residue 97 is located in a hydrophobic pocket in the middle of the four-helix bundle with most of its surface buried (Fig. 1). Based on the structure of the capsid (34), it is not clear why a conservative mutation in the dimer interface should change the behavior of the virus. The site of the Cp149-F97L mutation is remote from important sites of interactions between dimers. The site for intersubunit contact is dominated by residues 125 to 142, at either end of the dimer, ∼30 Å distant (Fig. 1). The base of the dimer interface, about 20 Å away, forms the interior of the virus and may contact encapsidated nucleic acid and reverse transcriptase. The outer extremity of the four-helix bundle is believed to participate in binding surface protein to mediate export (5, 10, 28), though it has also been observed that mutations at residues 95, 96, and 97 affect export (15, 20, 36).

In our previous studies, we described the assembly thermodynamics and kinetics of Cp149-wt from the adyw strain of HBV. Assembly was fast and nucleated and showed few intermediates (7, 44). The individual subunit-subunit interactions were very weak, on the order of −3 to −4 kcal/mol (depending on reaction conditions), which corresponded to a millimolar association constant per contact (7). The resulting capsids were stable because each subunit was involved in four contacts and because of a kinetic barrier to dissociation (hysteresis) (22). The ionic strength dependence of assembly and the effect of Zn2+ on assembly kinetics suggested that assembly was regulated by a transition of Cp from the assembly-inactive state to the assembly-active state (7, 25).

In this study we observe that the Cp149-F97L mutant protein assembles faster and with dramatically different thermodynamics than Cp149-wt, suggesting that this seemingly innocuous mutation enhances the ability of the capsid protein to adopt the assembly-active state and pass through the transition state of the assembly reaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein.

Residue 97 was mutated from phenylalanine to leucine with the Stratagene QuikChange kit. The plasmid construct pCp149 (33) was mutated with the mutagenic primer GTGGGCCTAAAGCTCAGACAATTATTGTGG, where the leucine codon is underlined. Cp149-wt and Cp149-F97L were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as previously described (42), except that cells expressing F97L were grown at 30°C. The mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing and mass spectrometry. An extinction coefficient (ɛ280) of 60,900 M−1 cm−1 (43) was used for both proteins.

Assembly and stability assays.

The Cp dimer was dialyzed into assembly buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 1 mM dithiothreitol) prior to reactions. The dimer was assembled by mixing it with an equal volume of 0.3 M NaCl assembly buffer, to yield a final NaCl concentration of 0.15 M. Assembly reactions were monitored by light scattering in a SPEX Fluoromax-2 fluorometer (Instruments S.A. Inc., Addison, N.J.) (44). Concentrations of capsid and dimer were determined by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a 27-ml Sephacryl S-300 HR column or a 21-ml Superose 6 HR column connected to an AKTA FPLC instrument or a Shimadzu high-pressure liquid chromatography instrument. The capsid eluted at 8 ml and the dimer eluted at 18 ml in the Superose 6 column (7). Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded at 21°C with a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter and a Hellma 0.1-mm path-length quartz cell (22). Multiangle laser light scattering data were measured with a Dawn detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, Calif.).

Data analysis.

The SEC data were analyzed to determine thermodynamic parameters as previously described (7). Briefly, for the assembly reaction where 120 dimers form a capsid, the equilibrium constant, Kcapsid, is given by

|

(1) |

where [dimer] and [capsid] are the concentrations of dimer and capsid, respectively. Kcapsid includes contributions from all 240 quasiequivalent interdimer contacts. The average per-contact association constant, Kcontact (equation 2), is in the more convenient units of inverse molarity; the coefficient in equation 2 describes the degeneracy of the assembly reaction (11, 41, 46).

|

(2) |

where Kcontact is related to the free energy per contact of each dimer by

|

(3) |

where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in degrees Kelvin.

RESULTS

Comparison of capsid stability determined from assembly reactions.

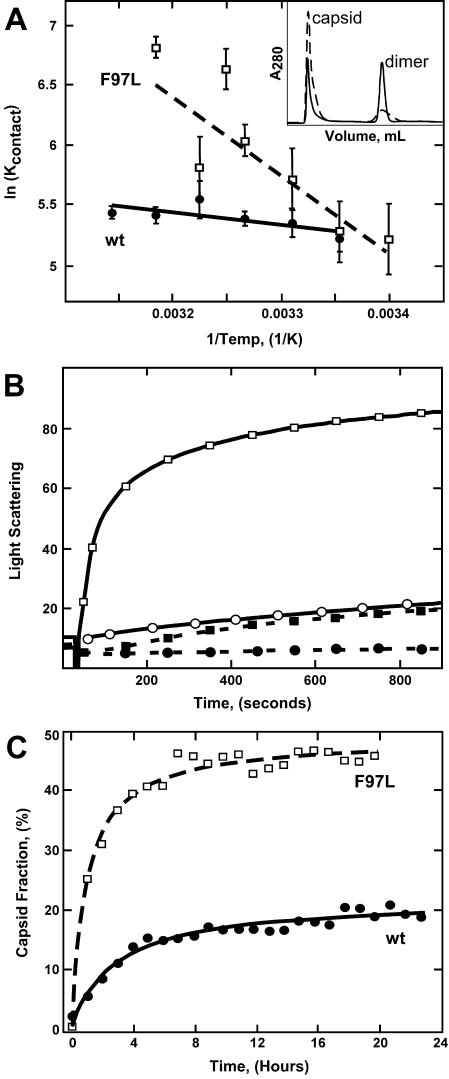

SEC is a simple and direct assay to determine concentrations of capsid and dimer at equilibrium. Capsid assembly reactions closely approach equilibrium, allowing determination of association energy (i.e., stability) for a given set of conditions (7, 11). No detectable intermediates were observed in chromatographs of either wild-type or mutant protein, as expected for a nucleated reaction (44). SEC data also show the capsids and dimers of the wild type and mutant elute at the same volumes (Fig. 2A, inset). Multiangle laser light scattering data were consistent with assignment of the two peaks as the 4-MDa capsid and 34-kDa dimer (data not shown). In agreement with other reports (19), Cp149-F97L and -wt capsids were indistinguishable by negative-stain electron microscopy and on sucrose gradients (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Mutation F97L alters assembly properties of Cp149. (A) A van't Hoff plot comparison of assembly of Cp149-F97L (dashed line) and Cp149-wt (solid line). The equilibrium data were obtained by SEC (the inset shows F97L [dashed line] and the wild type [solid line]). The per-contact association constants for both proteins at 21°C were identical (intersection of lines; see Table 1); however, the temperature dependence of the assembly reaction for Cp149-F97L (squares) was much greater than that for the wild type (circles). Data were fit to straight lines, imposing temperature independence on ΔH, with slopes proportional to enthalpies of +7.4 kcal/mol for Cp149-F97L (dashed line) and +1.5 kcal/mol for the wild type (solid line). Each point is the average of at least seven measurements. (B) The assembly kinetics at 21°C of Cp149-F97L (squares) and Cp149-wt (circles) were monitored by 90° angle light scattering (in arbitrary units) at 320 nm. Assembly was induced by addition of salt to a final concentration of 0.15 M. Final protein concentrations were 20 (solid symbols) and 25 μM (open symbols). Though Cp149-wt was slower than Cp149-F97L, both reactions reached the same final concentration of capsid. (C) The time course of capsid assembly at 37°C was observed at 1-h intervals by SEC. The percentage of protein in capsid form for the mutant Cp149-F97L protein (squares) increased very rapidly during the first few hours of assembly, whereas the reaction for Cp149-wt (circles) was much slower. The data were fit to a hyperbolic curve.

Assembly reactions at 21°C showed that Cp149-wt and Cp149-F97L assemble to the same extent but with different kinetics (Fig. 2A and B). The effect of the mutation was even more evident when the assembly reactions were compared at 37°C; the yield of capsid was greater and assembly was much faster for Cp149-F97L than for Cp149-wt (Fig. 2C). Above 37°C, unlike Cp149-wt (7), Cp149-F97L had a marked tendency to form heterogeneous aggregates with masses on the order of tens of megadaltons, based on multiangle laser light scattering (data not shown).

Assembly of Cp149-F97L was measured at a range of protein concentrations to establish isotherms for determining Kcapsid, and at different temperatures to determine enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS). Values for Kcapsid, the association constant for capsid from 120 dimers (equation 1), were obtained from reactions that were equilibrated for 24 h. Longer incubations did not affect the yield of capsid (Fig. 2C). Kcapsid was partitioned into Kcontact (equation 2), the association constant for individual dimer-dimer interactions. The Kcontact values of both proteins at 21°C were identical, corresponding to a ΔGcontact value of −3.0 kcal/mol (equation 3) or a dissociation constant of only ∼6 mM (Table 1). Because each dimer makes quasiequivalent contacts with four neighboring dimers, this association energy results in a micromolar apparent dissociation constant for the capsid, where KDapparent is defined as the concentration where [dimer] and [capsid] are equal (7, 40, 41). However, at 37°C the association energy for Cp149-F97L was −3.6 kcal/mol, substantially stronger than that for Cp149-wt (Table 1). In short, the temperature dependence of association is far greater for Cp149-F97L than for Cp149-wt.

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters describing assembly of Cp149-wt and -F971La

| Protein | ΔG (kcal/mol) at:

|

ΔH (kcal/mol) | −TΔS (kcal/mol) at 37° | 1/Kcontact (mM) at:

|

KDapparent (μM) at 37° | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25° | 37° | 25° | 37° | ||||

| Cp149-wt | −3.0 | −3.27 | +2.0 | −5.27 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 8.3 |

| Cp149-F97L | −3.0 | −3.6 | +7.4 | −11.0 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

Values are per contact. Temperatures are in degrees Celsius.

The Kcontact data were compared in a van't Hoff plot (Fig. 2A). The slope in a van't Hoff plot is equal to −ΔH/R, where R is the universal gas constant. The negative slopes in Fig. 2A show that both reactions had a positive enthalpy of association. The greater temperature dependence for the assembly of Cp149-F97L compared to that for the assembly of Cp149-wt indicated a much larger enthalpy of assembly. Enthalpy was calculated as a temperature-independent parameter since our data were not sufficient to describe heat capacity-induced curvature of the van't Hoff plot.

Assembly of Cp149-F97L was much faster than that of Cp149-wt.

For a simple reaction, the initial rate of reaction is independent of the end point; i.e., kinetics are independent of association energy. However, capsid assembly is best described as a cascade of reactions, where the stability of intermediates has a marked effect on the rate of appearance of the final product (11, 41). Comparison of kinetics, showing that Cp149-F97L had a faster intrinsic rate of assembly, was unambiguous at 21°C (Fig. 2B), where both proteins have the same association energy.

Light scattering is a convenient method for measuring HBV capsid formation. SEC data demonstrate that concentrations of intermediates in these reactions are very low so that the increase in light scattering is almost exclusively due to accumulation of capsids (45). At 21°C and 150 mM NaCl, a concentration greater than 15 μM Cp149-wt is required for appreciable accumulation of capsid (7). Under these conditions, Cp149-F97L assembled much faster than Cp149-wt, though the final yields of capsid were the same (Fig. 2B). At 37°C, the greater stability of intersubunit contacts combined with faster kinetics further enhanced assembly of Cp149-F97L relative to that of Cp149-wt (Fig. 2C).

Comparison of the structure and stability of Cp149-F97L and -wt dimers.

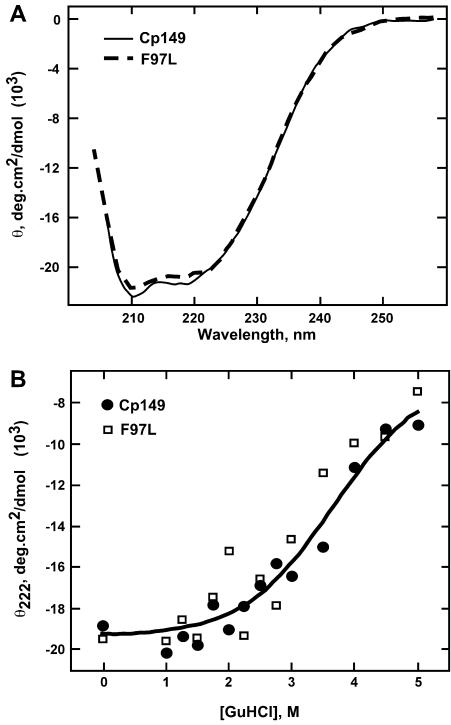

There are many possible explanations for enhanced enthalpy of assembly for the mutant protein. One possibility is that the mutant protein refolds during assembly. To test this possibility, we examined the CD spectra of both proteins and the sensitivity of the proteins to denaturation. The two proteins had nearly identical spectra, indicating that they have the same largely α-helical secondary structure (Fig. 3A). We examined the stability of wild-type and mutant dimer by observing their denaturation in guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl). We found that the GuHCl titrations of Cp149-wt and -F97L were nearly identical, indicating that the two proteins had approximately the same stability and that both proteins were folded in the absence of denaturant (Fig. 3B). These results are in agreement with fluorescence studies (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

CD spectroscopy demonstrates that Cp149-F97L and -wt have similar structures and stabilities. (A) CD spectra recorded for Cp149-wt (solid line) and Cp149-F97L (dashed line). The double minima at 210 and 222 nm are diagnostic for α-helical secondary structure. (B) Molar ellipticities at 222 nm, averaged from three or more CD spectra, of Cp149-wt (circles) and Cp149-F97L (squares) were plotted as a function of GuHCl concentration. CD is sensitive to unfolding at ≥3 M GuHCl but insensitive to capsid dissociation (22). A single line fit both data sets, indicating that the wild-type protein and Cp149-F97L do not have significant differences in stability.

DISCUSSION

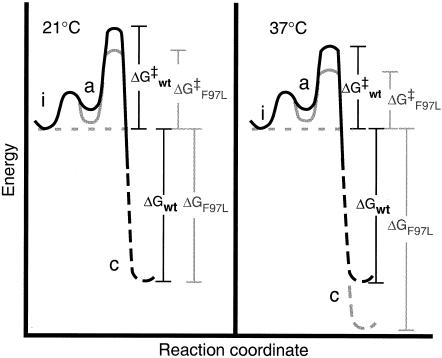

To better understand regulation of the life cycle of HBV, we compared assembly of Cp149-wt with that of Cp149-F97L, which has a mutation that is common in chronic infections. We found that the Cp149-F97L mutant capsid protein assembles more rapidly than Cp149-wt at 21°C, but to the same equilibrium concentration. At 37°C, Cp149-F97L assembly is faster and forms a thermodynamically more stable particle. The kinetic result implies that the mutant protein is more able to assume the transition state conformation for the assembly reaction, i.e., the activation energy (ΔG‡) is lower for Cp149-F97L (Fig. 4). The enhanced stability of the Cp149-F97L capsids may be due to changes in the stability of the unassembled form of core protein dimer and/or its assembled form in capsids. Effectively, the mutant protein is able to support capsid assembly at concentrations too low for the wild-type protein (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 4.

Model describing the energetics of wild-type and Cp149-F97L capsid assembly. Our data show that at 21°C the Kcontact values for both proteins are the same. However, the kinetics of capsid formation were much faster for the mutant than for the wild type. This indicates that the energetic barrier to reach the transition state must be smaller. Because the observed rate of assembly will also be affected by the concentration of the assembly-active state, the faster rate could be due to either a more stable active state of the dimer and/or a smaller ΔG‡. The energy barrier represented by ΔG‡ in this figure includes nucleation and subsequent assembly. At physiological temperature, the ΔGcontact of Cp149-F97L assembly is stronger and the rate constant is faster than those for Cp149-wt. Thus, at 37°C the Cp149-F97L dimer may start at a higher energy state than the wild type and/or the capsid may be at lower energy. The enhanced rate may be due to changes in the stability of the assembly-active state or ΔG‡ from that at 21°C. However, we observed that dimer stabilities for both proteins are about the same, and thus stability is not linked to the energy of assembly. Therefore, the difference in rate must be attributable to the ability of the mutant protein to undergo the conformational changes required for assembly. Thus, we propose that the Cp149-F97L mutation affects assembly by altering protein dynamics.

The increased stability of mutant capsids at 37°C was the result of a dramatic change in ΔH and ΔS. This result is surprising because the site of the F97L mutation is the intradimer four-helix bundle, not the interface between dimers. Generally, the enthalpy of a reaction correlates with buried surface area (1, 23), but the site of the F97L mutation is not close to surfaces that are buried during assembly (34). We eliminated the possibility that the enthalpy difference was due to partial unfolding of Cp149-F97L by showing stability similar to that of the wild type based on denaturation studies (Fig. 3). Our experiments also showed that kinetics of Cp149-F97L assembly were faster (Fig. 2B and C), indicating a lower energy barrier to assembly (Fig. 4). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the F97L mutation supports a conformational transition that is involved in the assembly reaction.

Leucine has physical properties similar to those of isoleucine and phenylalanine but leucine is structurally distinct. Mutation of leucine to isoleucine can have drastic consequences for structure (see, for example, reference 32). In the HBV capsid structure (34) (Fig. 1) it can be seen that the β methyl of I97 constrains its freedom of motion. A phenylalanine at position 97 would fill most of the pocket observed in the four-helix bundle, similarly constraining the residue and the protein. A leucine, which has no β methyl and is smaller that phenylalanine, would be expected to have significantly greater freedom of motion. Because there are (i) altered thermodynamics, (ii) enhanced kinetics, and (iii) presumably no change in the protein surfaces that are actually buried during assembly, we propose that the F97L mutation makes it easier for the dimer to undergo the structural transition required for assembly.

The large changes in enthalpy and entropy suggest significant structural differences between Cp149-wt and -F97L, associated with the assembly reaction. The faster association rate indicates that this change also affects the stability of the assembly transition state (ΔG‡ in Fig. 4). However, we found no evidence for structural differences between dimers (Fig. 3). The transition state may be related to the conformational change from an assembly-inactive dimer to an assembly-active state, hypothesized for capsid assembly (7, 25). The hypothesis that HBV assembly is sensitive to changes in protein conformation is consistent with our recent observation that Zn2+ induces a conformational change in the unassembled dimer and increases the rate of capsid assembly without altering assembly thermodynamics; i.e., Zn2+ changes the stability of an intermediate state compared to reactant (dimer) but not the stability of the product (capsid) compared to reactant (25). We have suggested that formation of this intermediate-state, assembly-active dimer plays a role in regulating assembly (25). How does our study of the assembly of empty capsids compare with assembly of cores in vivo? Regulation of capsid assembly is probably a mechanism for limiting encapsidation of nonviral nucleic acid; otherwise one would expect a high proportion of capsids containing nonviral RNA. Thus, regulating factors and the intrinsic association energy and kinetics are likely to be critical to HBV assembly in vivo, though not necessarily independent of the Cp RNA-binding domain and viral RNA.

A recent report (19) observed that wild-type and I97L capsids are equally stable, based on resistance to denaturants. We argue that dissociation is an insensitive assay for determining capsid stability. Unlike capsid assembly reactions, which closely approach equilibrium (7, 11), dissociation reactions are affected by hysteresis (22, 30), i.e., there is a kinetic barrier to equilibrium. Based on thermodynamic-kinetic models of assembly (22), we have shown that hysteresis occurs because the large intermediates found in the early stages of a dissociation reaction preferentially reassociate to form capsids, except when ΔGcontact decreases catastrophically, as if by a great excess of denaturant. This local energy minimum impedes the reaction from equilibrating to the global energy minimum. Consequently, the stability of viruses and other large oligomers can be determined only from assembly reactions, not dissociation studies. Unlike larger oligomers, monomers and dimers generally do not display hysteresis (30), allowing us to compare stability of wild-type and F97L dimers (Fig. 3B).

Mutation of core protein residue 97 is among the most common mutations observed in chronic infections (13, 36). Why would a mutation such as F97L be selected for? The enhanced association energy and kinetics of assembly indicate that F97L can support assembly even when expression of the capsid protein is lower. The increase in intracellular replication (26) would be an expected consequence of increased capsid assembly, since capsid formation is believed to activate reverse transcription (2, 3, 12, 18, 27, 29). Premature or immature secretion (36, 37) may also be related to increased availability of core. Mutations to polymerase (31) or treatment with the polymerase inhibitor lamivudine (38) also leads to secretion of single-stranded DNA-containing particles, which suggests that there may not be a strict link between the completion of genome replication and core particle secretion (12). Thus, any mutation that increases the availability of cores could increase the fraction of secreted immature particles, as DNA polymerization probably stalls when access to deoxynucleoside triphosphates is prevented by envelopment.

Acknowledgments

A research scholar grant (RSG-99-339-04-MBC) from the American Cancer Society supported this work.

We thank Jennifer Johnson and Christina Bourne for helpful discussions and Bruce Baggenstoss at the EPSCOR Mass Spec facility for his assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, B. M., and K. P. Murphy. 1998. Prediction of binding energetics from structure using empirical parameterization. Methods Enzymol. 295:294-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartenschlager, R., M. Junker-Niepmann, and H. Schaller. 1990. The P gene product of hepatitis B virus is required as a structural component for genomic RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 64:5324-5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartenschlager, R., and H. Schaller. 1992. Hepadnaviral assembly is initiated by polymerase binding to the encapsidation signal in the viral RNA genome. EMBO J. 11:3413-3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum, F., and M. Nassal. 1990. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid assembly: primary structure requirements in the core protein. J. Virol. 64:3319-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bottcher, B., N. Tsuji, H. Takahashi, M. R. Dyson, S. Zhao, R. A. Crowther, and K. Murray. 1998. Peptides that block hepatitis B virus assembly: analysis by cryomicroscopy, mutagenesis and transfection. EMBO J. 17:6839-6845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottcher, B., S. A. Wynne, and R. A. Crowther. 1997. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature 386:88-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceres, P., and A. Zlotnick. 2002. Weak protein-protein interactions are sufficient to drive assembly of hepatitis B virus capsids. Biochemistry 41:11525-11531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conway, J. F., N. Cheng, A. Zlotnick, P. T. Wingfield, S. J. Stahl, and A. C. Steven. 1997. Visualization of a 4-helix bundle in the hepatitis B virus capsid by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature 386:91-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowther, R. A., N. A. Kiselev, B. Bottcher, J. A. Berriman, G. P. Borisova, V. Ose, and P. Pumpens. 1994. Three-dimensional structure of hepatitis B virus core particles determined by electron cryomicroscopy. Cell 77:943-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyson, M. R., and K. Murray. 1995. Selection of peptide inhibitors of interactions involved in complex protein assemblies: association of the core and surface antigens of hepatitis B virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2194-2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endres, D., and A. Zlotnick. 2002. Model-based analysis of assembly kinetics for virus capsids or other spherical polymers. Biophys. J. 83:1217-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerelsaikhan, T., J. E. Tavis, and V. Bruss. 1996. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid envelopment does not occur without genomic DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 70:4269-4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunther, S., L. Fischer, I. Pult, M. Sterneck, and H. Will. 1999. Naturally occurring variants of hepatitis B virus. Adv. Virus Res. 52:25-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu, J., D. O. Toft, and C. Seeger. 1997. Hepadnavirus assembly and reverse transcription require a multi-component chaperone complex which is incorporated into nucleocapsids. EMBO J. 16:59-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Pogam, S., and C. Shih. 2002. Influence of a putative intermolecular interaction between core and the pre-S1 domain of the large envelope protein on hepatitis B virus secretion. J. Virol. 76:6510-6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nassal, M., A. Rieger, and O. Steinau. 1992. Topological analysis of the hepatitis B virus core particle by cysteine-cysteine cross-linking. J. Mol. Biol. 225:1013-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nassal, M., and H. Schaller. 1993. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid assembly, p. 41-75. In W. Doefler and P. Bohm (ed.), Virus strategies. VCH Publishers, Weinheim, Germany.

- 18.Nassal, M., and H. Schaller. 1993. Hepatitis B virus replication. Trends Microbiol. 1:221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman, M., F. M. Suk, M. Cajimat, P. K. Chua, and C. Shih. 2003. Stability and morphology comparisons of self-assembled virus-like particles from wild-type and mutant human hepatitis B virus capsid proteins. J. Virol. 77:12950-12960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ponsel, D., and V. Bruss. 2003. Mapping of amino acid side chains on the surface of hepatitis B virus capsids required for envelopment and virion formation. J. Virol. 77:416-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeger, C., and W. S. Mason. 2000. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:51-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh, S., and A. Zlotnick. 2003. Observed hysteresis of virus capsid disassembly is implicit in kinetic models of assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 278:18249-18255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spolar, R. S., J. R. Livingstone, and M. T. Record, Jr. 1992. Use of liquid hydrocarbon and amide transfer data to estimate contributions to thermodynamic functions of protein folding from the removal of nonpolar and polar surface from water. Biochemistry 31:3947-3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stannard, L. M., and M. Hodgkiss. 1979. Morphological irregularities in Dane particle cores. J. Gen. Virol. 45:509-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stray, S. J., P. Ceres, and A. Zlotnick. Zinc triggers conformational change and oligomerization of hepatitis B virus capsid protein. Biochemistry, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Suk, F. M., M. H. Lin, M. Newman, S. Pan, S. H. Chen, J. D. Liu, and C. Shih. 2002. Replication advantage and host factor-independent phenotypes attributable to a common naturally occurring capsid mutation (I97L) in human hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 76:12069-12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Summers, J., and W. S. Mason. 1982. Replication of the genome of a hepatitis B-like virus by reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate. Cell 29:403-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan, W. S., M. R. Dyson, and K. Murray. 1999. Two distinct segments of the hepatitis B virus surface antigen contribute synergistically to its association with the viral core particles. J. Mol. Biol. 286:797-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, G. H., and C. Seeger. 1993. Novel mechanism for reverse transcription in hepatitis B viruses. J. Virol. 67:6507-6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber, G., A. T. Da Poian, and J. L. Silva. 1996. Concentration dependence of the subunit association of oligomers and viruses and the modification of the latter by urea binding. Biophys. J. 70:167-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei, Y., J. E. Tavis, and D. Ganem. 1996. Relationship between viral DNA synthesis and virion envelopment in hepatitis B viruses. J. Virol. 70:6455-6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willis, M. A., B. Bishop, L. Regan, and A. T. Brunger. 2000. Dramatic structural and thermodynamic consequences of repack a protein's hydrophobic core. Struct. Fold Des. 8:1319-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wingfield, P. T., S. J. Stahl, R. W. Williams, and A. C. Steven. 1995. Hepatitis core antigen produced in Escherichia coli: subunit composition, conformational analysis, and in vitro capsid assembly. Biochemistry 34:4919-4932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wynne, S. A., R. A. Crowther, and A. G. W. Leslie. 1999. The crystal structure of the human hepatitis B virus capsid. Mol. Cell. 3:771-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan, T. T., M. H. Lin, S. M. Qiu, and C. Shih. 1998. Functional characterization of naturally occurring variants of human hepatitis B virus containing the core internal deletion mutation. J. Virol. 72:2168-2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan, T. T., G. K. Sahu, W. E. Whitehead, R. Greenberg, and C. Shih. 1999. The mechanism of an immature secretion phenotype of a highly frequent naturally occurring missense mutation at codon 97 of human hepatitis B virus core antigen. J. Virol. 73:5731-5740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan, T. T., P. C. Tai, and C. Shih. 1999. Subtype-independent immature secretion and subtype-dependent replication deficiency of a highly frequent, naturally occurring mutation of human hepatitis B virus core antigen. J. Virol. 73:10122-10128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, W., H. J. Hacker, M. Tokus, T. Bock, and C. H. Schroder. 2003. Patterns of circulating hepatitis B virus serum nucleic acids during lamivudine therapy. J. Med. Virol. 71:24-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou, S., and D. N. Standring. 1992. Hepatitis B virus capsid particles are assembled from core-protein dimer precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10046-10050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zlotnick, A. 2003. Are weak protein-protein interactions the general rule in capsid assembly? Virology 315:269-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zlotnick, A. 1994. To build a virus capsid. An equilibrium model of the self assembly of polyhedral protein complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 241:59-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zlotnick, A., P. Ceres, S. Singh, and J. M. Johnson. 2002. A small molecule misdirects assembly of hepatitis B virus capsids. J. Virol. 76:4848-4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zlotnick, A., N. Cheng, J. F. Conway, F. P. Booy, A. C. Steven, S. J. Stahl, and P. T. Wingfield. 1996. Dimorphism of hepatitis B virus capsids is strongly influenced by the C-terminus of the capsid protein. Biochemistry 35:7412-7421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zlotnick, A., J. M. Johnson, P. W. Wingfield, S. J. Stahl, and D. Endres. 1999. A theoretical model successfully identifies features of hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. Biochemistry 38:14644-14652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zlotnick, A., I. Palmer, S. J. Stahl, A. C. Steven, and P. T. Wingfield. 1999. Separation and crystallization of T=3 and T=4 icosahedral complexes of the hepatitis B virus core protein. Acta Cryst. D 55:717-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zlotnick, A., and S. J. Stray. 2003. How does your virus grow? Understanding and interfering with virus assembly. Trends Biotechnol. 21:536-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]