Abstract

Background

Predictors of erosive esophagitis (EE) and Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and the influence of number of risk factors in the community are not well defined.

Methods

Rates of BE and EE among community residents identified in a randomized screening trial were defined. The risk of EE and BE associated with single and multiple risk factors (gender, age, GERD, Caucasian ethnicity, ever tobacco use, excess alcohol use, family history of BE or EAC, and central obesity) was analyzed.

Results

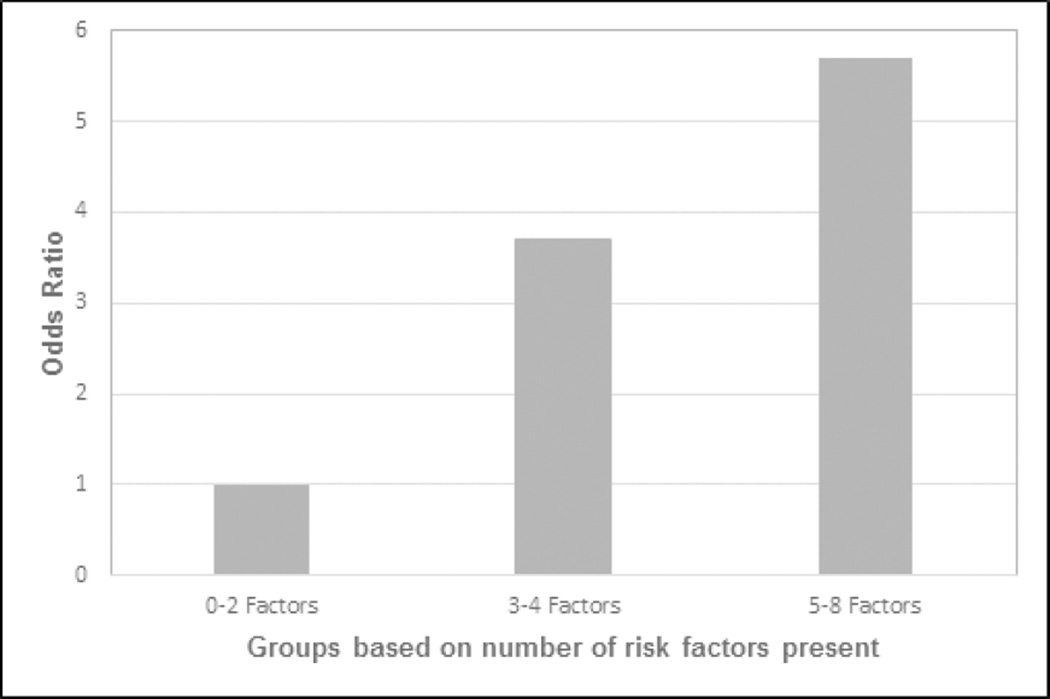

68 (33%) of 205 subjects had EE and/or BE. BE prevalence was 7.8% with dysplasia present in 1.5%. Rates were comparable between subjects with and without GERD. Male sex and central obesity were independent risk factors. The odds of EE or BE were 3.7 times higher in subjects with 3 or 4 risk factors and 5.7 times higher in subjects with five or more risk factors compared to those with 2 or less factors.

Conclusions

EE and BE are prevalent in the community regardless of the presence of GERD. Risk appeared to be additive, increasing substantially with 3 or more risk factors.

Keywords: Esophageal adenocarcinoma, Barrett’s esophagus, transnasal endoscopy, predictors, screening, randomized trial, obesity

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has exponentially increased in the developed world in the last four decades.[1] Five year survival rates are less than 20% when EAC is diagnosed after symptoms have developed, but rates dramatically improve to over 80% when EAC is detected at an early stage.[2] Thus, screening for BE in high-risk subjects is recommended as a potential strategy to improve EAC outcomes.[3,4] However, these guidelines do not provide specific recommendations regarding the number of risk factors or risk stratification based on a combination of these predictors.

BE screening paradigms have historically focused on the presence of chronic gastroesophageal reflux (GER) symptoms.[5,6] However, a significant proportion of BE and EAC cases are diagnosed in patients without chronic or frequent GER symptoms.[7] In fact, several studies have reported the prevalence of BE to be substantial in subjects without symptoms of GER and comparable to the BE prevalence in subjects with symptoms.[8–10] Hence, additional non-GERD risk factors need to be explored as BE predictors, particularly in community-based subjects.[11,12] A far more predictive factor for the presence and/or development of Barrett’s esophagus is erosive esophagitis.[1–3] Unfortunately, there are no guidelines on who should be screened for erosive esophagitis.

Current society guidelines recommend screening in subjects by listing multiple risk factors, intuitively assuming a positive correlation between BE prevalence and the number of risk factors. However the weighting and precise use of these risk factors either individually or in combination to predict the presence of erosive esophagitis and/or Barrett’s esophagus are not well studied.[3,4] Furthermore, current prediction models based on the presence of multiple risk factors are largely derived from BE registries of tertiary care centers.[13,14] Thus, current strategies may not be appropriate for screening in the community.

We recently conducted a community based, prospective randomized trial investigating the clinical effectiveness of minimally invasive endoscopic methods for esophageal screening.[15] Within the context of this trial, the aims of this study were 1. To assess the prevalence and predictors of EE and BE in community subjects with and without GER symptoms; and 2. To determine how the use of individual or a combination of risk factors can serve as a clinical tool for identifying patients at risk for BE/EAC.

METHODS

Trial Design and Setting

This randomized trial was conducted in Olmsted County, MN, between April 1, 2011 and October 30, 2013. The study was designed to compare the clinical effectiveness of unsedated transnasal endoscopy (uTNE) in a mobile research van unit (muTNE), uTNE in a hospital endoscopy unit (huTNE), and conventional sedated endoscopy (sEGD). Please refer to Sami et. al for details.[15] The study found the clinical effectiveness of the three techniques to be comparable. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (identifier: NCT01288612).

Participants

The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) database includes a cohort of over 2500 age- and gender-stratified residents of Olmsted County who have completed validated gastrointestinal symptom questionnaires from 1998 to 2009. Using REP resources to identify potential participants, 459 community subjects 50 years or older in age were recruited by an invitation letter and ultimately enrolled during a phone conversation by a blinded research coordinator using a standardized telephone script. Subjects were stratified by age, sex, and presence or absence of GER symptoms (as per validated questionnaires) and randomly assigned to a study group (approximately 150 per group) to receive endoscopic screening by one of the following methods: muTNE, huTNE, or sEGD.

Interventions

Prior to endoscopic evaluation, subjects filled out the validated GERQ instrument (see Appendix 1 for GERD pertinent questions),[16] and anthropometric measurements were obtained by research coordinators. The GERQ focuses on GER symptoms over the last year but also queries a history of GER symptoms and use of acid reducing medications.

The presence of GER was defined by at least one of the following criteria as reported on the GERQ: heartburn more frequently than once a week, acid regurgitation more frequently than once a week, or frequent over the counter antacid use, daily histamine receptor type-2 antagonists and/or daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use for GERD. The GERQ does not include specific questions regarding the effect of acid suppressing medications on GERD symptoms. Therefore, the inclusion criterion of daily PPIs or histamine receptor type-2 antagonists was necessary to identify and include subjects with GERD who are currently minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic on acid suppressing medications, but continue to be at risk for BE. [13] Review of the medical records was conducted to ensure that these medications were prescribed for GERD.

Consenting subjects underwent the one of three screening methods. Each endoscopy was conducted by one of two endoscopists (LMW or PGI). Both have expertise with uTNE and sEGD and had performed over 5000 upper gastrointestinal endoscopies before the study was initiated. They developed a consensus on the endoscopic definition of BE prior to study initiation. sEGD was performed using high definition endoscopes (GIF-Q180, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) and conscious sedation. uTNE was performed using the EndoSheath® transnasal esophagoscope (TNE-5000, Vision Sciences, Orangeburg, NY). This esophagoscope is covered by a sterile, disposable sheath that isolates it from patient contact. After the procedure, the used sheath is discarded and replaced with a new sterile sheath.

Landmarks assessment included the squamocolumnar junction (transition point from squamous epithelium to columnar epithelium), gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) (measured at the top of the gastric folds with the stomach deflated) and the diaphragmatic hiatus. Endoscopically suspected BE was biopsied. Histology was interpreted by a gastrointestinal pathologist blinded to group assignment.

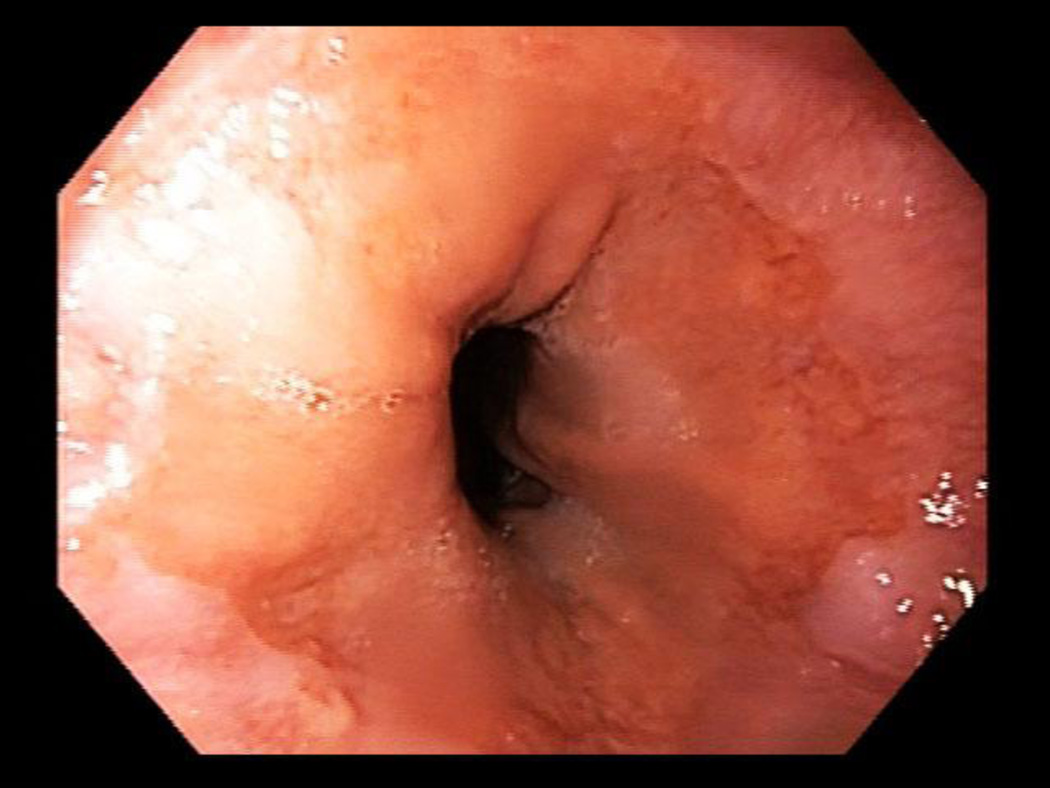

Suspected BE was defined as ≥ 1 cm of columnar metaplasia in the tubular esophagus on endoscopy. BE segment length was classified using the Prague criteria.[17] Figure 1 shows short segment BE C0M1 while Figure 2 shows an irregular Z line, which did not meet criteria for BE. Confirmed BE required presence of intestinal metaplasia on H&E stains. Esophagitis was described using the Los Angeles classification.[18] Subjects with esophagitis were treated with PPIs and then reassessed endoscopically in twelve weeks for healing and presence of BE. Per protocol, all subjects regardless of initial endoscopy type (huTNE, muTNE, sEGD) all had an EGD if follow up endoscopic evaluation was necessary.

Figure 1.

Distal esophageal mucosa and GE junction with short segment BE C0M1.

Figure 2.

Distal esophageal mucosa and GE junction with an irregular Z line, which did not meet criteria for BE.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was prevalence and predictors of EE and BE stratified by GER symptoms. EE and BE were combined given the common etiology of EE and BE, with EE being a precursor of BE.[19–21] Analyses were performed to identify demographic factors associated with subjects with and without GER symptoms. The secondary outcome was assessment of influence of the number of risk factors on EE and BE prevalence.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized by mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency and proportion for categorical variables. Clinical characteristics, esophagitis grade, BE prevalence, presence of dysplasia and diaphragmatic hernia (DH) were compared between study groups with univariate logistic regression. Length of BE and DH size were compared with student’s t-test.

Association of individual risk factors with EE/BE was assessed with logistic regression. Models were created with a-priori selected set of seven predictor variables: gender, age, GER symptoms, ever tobacco use, excess alcohol use (men: >2 alcoholic drinks per day, women: >1 alcoholic drink per day), family history of BE or EAC, and central obesity (waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) for males >0.90 and females >0.85) as defined by the WHO.[22] Despite Caucasian race being a known risk factor for BE, it was not included in this analysis due to the homogeneity of the cohort (98% Caucasian). Multivariate analyses were conducted using backward stepwise regression models.

The influence of cumulative number of risk factors for EE (LA grade B, C, D) on BE risk was estimated. LA grade A esophagitis was excluded from this analysis given its historically higher inter-observer variability.[18] Eight selected variables (gender, age, GER symptoms, Caucasian race, ever tobacco use, excess alcohol use, family history of BE or EAC, and central obesity) were defined and weighed equally. The risk of EE/BE was analyzed and compared between three groups (0–2, 3–4, or 5–8 factors present). Influence of sex on the interaction of risk factors was tested. Statistical significance was defined as a two sided alpha value of less than 0.05. SAS® software version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary NC, was used.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

205 of 459 subjects invited, were screened; (73 (36%) muTNE, 71 (35%) huTNE, 61 (30%) sEGD). Baseline characteristics of the invited subjects and participants were comparable.[15] Baseline characteristics for all participants are summarized in table 1. 46% were male with a mean (SD) age of 70 (11) years. 98% were Caucasians. Mean (SD) WHR was 0.93 (0.09) in males and 0.86 (0.09) in females. 68 (33%) participants had GER symptoms. 82% of subjects with GER symptoms reported symptoms for “more than 2 to 5 years” or longer.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of All Subjects

| Baseline Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 46% (95/205) |

| Female | 54% (110/205) |

| Age (SD) | 70 (11) years |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 98.5% (202/205) |

| Non-Caucasian | 1.5% (3/205) |

| Mean (SD) Waist to Hip Ratio (WHR) | |

| Male | 0.93 (0.09) |

| Female | 0.86 (0.09) |

| GER Symptoms | |

| Present | 33% (68/205) |

| Absent | 67% (137/205) |

| Ever Tobacco Use | 38% (77/205) |

| Excess Alcohol Use† | 10% (21/205) |

Excess Alcohol Consumption classified as greater than 2 alcohol beverages per day

Prevalence of esophagitis and BE

The prevalence of esophagitis and BE in subjects with and without GER symptoms (see Table 2) was comparable statistically. The prevalence of EE was 32% (LA grade A 36%, B 55%, C 9%, D 0%) and 28% (LA grade A 53%, B 42%, C 5%, D 0%) in the groups with and without GER symptoms, respectively. The symptomatic GER group had a numerically higher proportion of Grade B and C esophagitis (64%) compared to the group without symptoms (48%) (p= 0.22). The prevalence of BE was 7.8% overall and was comparable between the GER symptoms and asymptomatic groups (8.8% vs. 7.3% p=0.49). Twelve of 16 cases of BE were diagnosed on follow up endoscopy after treatment of EE. The mean (SD) BE length was 3.5 (2.4) cm in the GER symptom group and 2.6 (1.4) cm in the group without symptoms (p= 0.62). Two of the six BE cases (33%) in the GER symptom group were long segment BE (LSBE); two of the ten BE cases (20%) in the asymptomatic group were LSBE.

Table 2.

Prevalence of esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in cohorts with and without GERD.

| GERD Group (68) | Non-GERD group (137) |

Comparison p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagitis Prevalence | 22 (32%) | 40 (29%) | 0.78 |

| Grade A | 8 | 21 | |

| Grade B | 12 | 17 | |

| Grade C | 2 | 2 | |

| BE Prevalence | 6 (8.8%) | 10 (7.3%) | 0.49 |

| Mean (SD) length (cm) | 3.5 (2.4) | 2.6 (1.4) | 0.62 |

| Dysplasia present† (%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | |||

| Present (%) | 44 (65%) | 79 (58%) | 0.26 |

| Mean (SD) size (cm) | 3.6 (2.1) | 2.6 (0.9) | 0.001* |

p < 0.05 considered significant

Three cases of dysplasia were identified: 1 HGD located in SSBE and 2 LGD located in one SSBE and one LSBE

Three cases of dysplasia were identified: 1 HGD located in SSBE and 2 LGD located in one SSBE and one LSBE. The one subject with HGD did receive radiofrequency ablation therapy. Dysplasia rate of 1.5% was comparable between the GER symptom group and the group without symptoms. Size of hiatal hernia was comparable in both groups.

Clinical Characteristics Associated with EE and BE

Clinical characteristics were compared between subjects with and without EE/BE (see Table 3). There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups with respect to male sex, WHR, and alcohol use. BMI, prevalence of GER symptoms or tobacco use were not different between the two groups. Hence, subjects with EE/BE were more likely to be centrally obese men consuming greater than 2 alcoholic beverages per day.

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of subjects with or without EE/BE.

| Group without EE/BE (138) |

Group with EE/BE (67) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 70 (9) | 70 (9) | 0.91 |

| Male Sex (%) | 55 (39%) | 40 (60%) | 0.004* |

| WHR Mean (SD) | 0.89 (0.1) | 0.94 (0.09) | 0.013* |

| BMI Mean (SD) | 29.2 (10.7) | 29.9 (5.4) | 0.62 |

| GER Symptoms (%) | 46 (33%) | 23 (34%) | 0.78 |

| Ever Tobacco Use (%) |

54 (38%) | 23 (34%) | 0.87 |

| Excess Alcohol Use (%) |

10 (8.7%) | 11 (22%) | 0.014* |

p < 0.05 considered significant

These characteristics were also compared between subjects with EE or BE and stratified by the presence of GER symptoms (supplementary Table 1). Male predominance, increased WHR, and excess alcohol were numerically greater, but not statistically different from subjects without GER symptoms who had developed EE or BE. In contrast, the presence of GER symptoms in combination with these risk factors was associated with a higher prevalence of EE/BE.

Clinical Risk Factors as Predictors of EE and BE

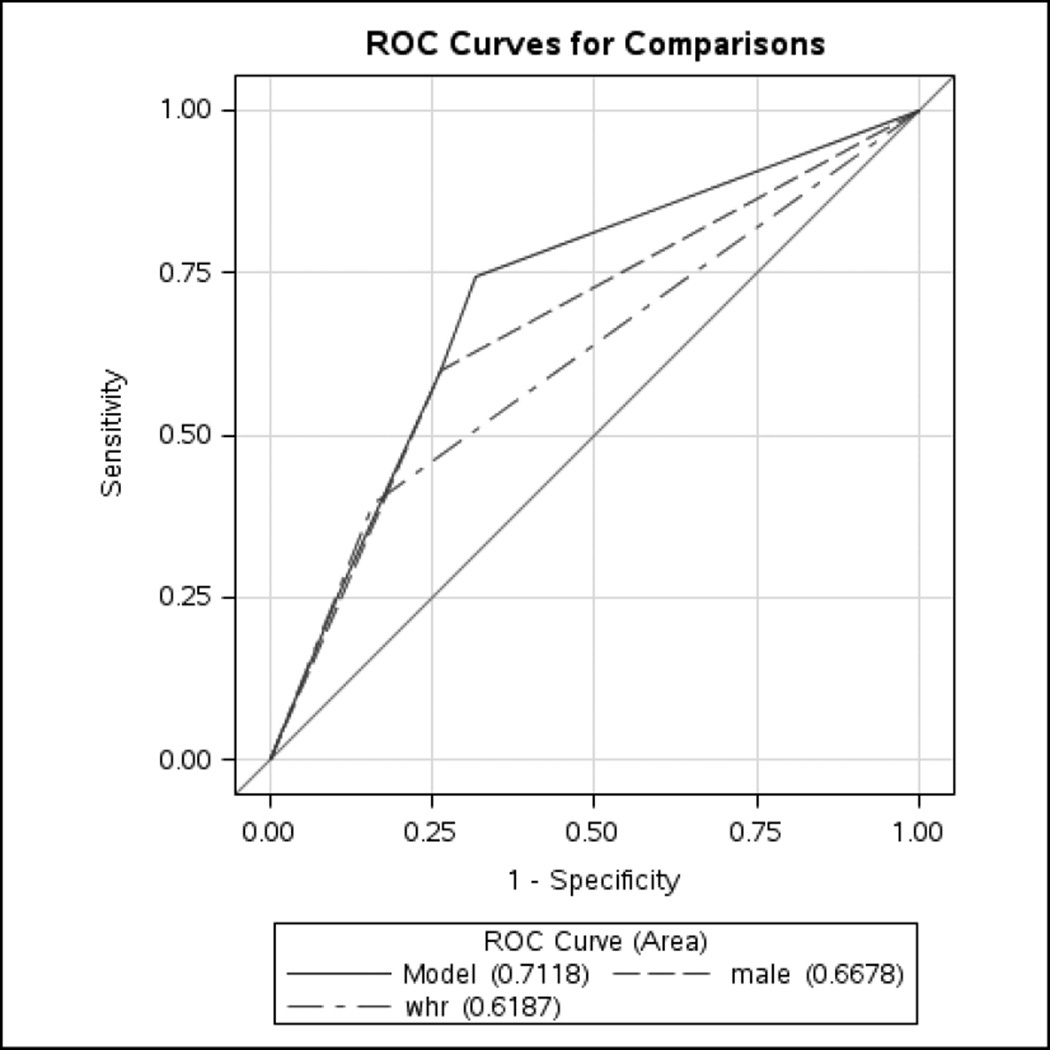

Male sex (OR 3.8, 95% CI 1.7, 8.4) and central obesity (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.2, 7.7) were independent predictors of EE and BE (Table 4). Age, tobacco use, family history, presence of GERD, and excess alcohol use were not significant risk factors. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the multivariable model (including age, male sex, GERD, WHR ratio, Caucasian ethnicity, smoking history, excess alcohol use, family history of BE or EAC) predicting the presence of EE/BE was 0.71 (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Risk Factors and their association with esophageal injury or metaplasia.

| Risk Factor | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Male Sex | 4.2 (1.9, 9.2) | 0.0004* | 3.8 (1.7, 8.4) | 0.001* |

| Age | 2.1 (0.99, 4.4) | 0.05 | ||

| Central Obesity | 3.5 (1.4, 8.8) | 0.008* | 3.0 (1.2, 7.7) | 0.02* |

| GERD | 1.6 (0.8, 3.2) | 0.22 | ||

| Ever Tobacco Use | 0.9 (0.5, 1.9) | 0.86 | ||

| Family History | 0.7 (0.3, 1.6) | 0.43 | ||

| Excess Alcohol Use | 1.9 (0.7, 4.7) | 0.21 | ||

p < 0.05 considered significant

Figure 3.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves showing the performance of the multivariable model in assessing BE/EE risk among community residents, compared to models using only waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) data and models using only male sex data. The multivariable model includes age, male sex, GERD, central obesity, Caucasian ethnicity, smoking history, excess alcohol use, family history of BE or EAC.

The cumulative number of risk factors per subject was analyzed as predictors of EE (LA grade B, C, D) or BE. The rate of EE/BE in subjects with 0–2 risk factors was 6.1%, while the rate in subjects with 3–4 factors and 5–8 factors was 20% and 30%, respectively (p<0.05). The risk of EE/BE was 3.7 times greater (95% CI 1.5, 13.0) for subjects with 3–4 factors. Presence of 5–8 factors was associated with an almost 6 fold higher risk of EE/BE (95% CI 1.5, 22.5) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Risk of Esophagitis and BE increases with increasing number of risk factors. Risk factors include age, male sex, GERD, central obesity, Caucasian ethnicity, smoking history, excess alcohol use, family history of BE or EAC.

* Compared to group 0–2 factors, group 3–4 factors [OR 3.7 (95% CI 1.5, 13.0.; p<0.05)] and group 5–8 [OR 5.7 (95% CI 1.5, 22.5; p<0.05)]

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that BE and EE prevalence in community subjects older than 50 years, is substantial. Overall, 7.8% of subjects had BE, with a comparable prevalence in those with and without typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux (8.8% and 7.3%, respectively). One third of study subjects had erosive esophagitis. Independent predictors of EE and BE included male sex and central obesity. We also identified a threshold of three or more risk factors, which were associated with a significantly higher risk of EE and BE.

The prevalence of BE in this study is comparable to prior reports from U.S. referral center cohorts, but higher than European reports which studied unselected populations [8–10,23] EE is also similarly prevalent in subjects with and without GER symptoms in European communities.[8,10] In our predominantly Caucasian community of adults older than 50 years, prevalence of esophagitis (all LA grades) was 32% overall and 29% in subjects without GER symptoms. More severe EE (LA Grade B and C) was also prevalent (16% overall) though more common in the group with GERD.

A reason for the high percentage of subjects with GERD in this study might result from the expanded definition used. Specifically, the presence of GER symptoms was defined as frequent recent typical symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation or a history of frequent symptoms currently well controlled by anti-reflux medications. These criteria were purposely utilized in order to include subjects with controlled, quiescent or treatment rendered asymptomatic reflux in addition to untreated symptomatic GERD, as both groups may have an increased risk of developing BE. [13] Review of the medical record and GERQ responses substantiated the use of acid suppressing medications for GERD symptoms in all subjects. Rubenstein et al recently used a similar questionnaire-based criterion for GERD to include currently asymptomatic subjects whose symptoms are currently well controlled by medications.[13] Gerson et al also excluded all subjects on proton pump inhibitors from the study cohort when reporting the prevalence of BE in women without GERD.[24]

The data from this study demonstrate that there was no significant difference in prevalence of EE/BE in subjects with and without GER symptoms. On the other hand, higher grades of EE (LA grades B and C), were more likely to be associated with symptoms. The presence of GER symptoms, however, was not an independent predictor of EE/BE in our study. There may be several explanations this finding. In a recent meta-analysis, GER symptoms were strongly associated with only long segment BE; but not short segment BE [6] The majority, 75%, of BE subjects in our study had short segment BE. Patients with BE have been shown to have increased yet asymptomatic esophageal acid exposure despite medical therapy[25] suggesting an esophagus that is hyposensitive to acid. Finally, there may also be GERD-independent mechanisms such as systemic inflammation contributing to the development of EE and BE, particularly in patients with central obesity.[11]

Central obesity was an independent risk factor for the presence of EE/BE in this community cohort. Central obesity is an independent risk factor for esophageal inflammation, linked to metabolically active proinflammatory cytokines and adipokines.[11] Central obesity is easily measurable in clinical practice by its marker WHR. As corroborated by other studies, BMI, (measuring overall obesity), was not associated with EE/BE in this study.[26]

We wished to assess the influence of the number of risk factors on the presence of EE/BE in the community. As 98% of the subjects were Caucasians, the vast majority of BE/EE subjects had at least 1 risk factor present. We found that risk appears to increase substantially in the presence of 3 or more risk factors and continues to rise as the number of factors increase. These results confirm the additive nature of risk factors, which has been assumed by current society guidelines.[4,27] Recent ACG guidelines recommend screening patients with chronic, frequent GER symptoms plus two additional risk factors. [4] Our results suggest that three risk factors, regardless of presence or absence of GER symptoms, may identify a population with a higher prevalence of BE. Further studies are essential to confirm this observation.

Our model had reasonable discriminant ability (AUC 0.71 in ROC curve) compared to the M-BERET model (AUC 0.72 in ROC curve), which used four factors in male veterans: GERD, age, tobacco use, and central obesity.[13] Additional studies with differential weighting of risk factors are required to assess the individual contribution of each of these risk factors. While the economic and clinical implications of the implementation of these models may be substantial, they can potentially improve the current ineffective model which lacks adequate discrimination and accrues significantly greater cost associated undiagnosed with BE leading to advanced stage EAC. Community-based minimally invasive screening techniques that are more acceptable and cost-efficient, utilizing these models, could off-set the costs of increasing the screening pool.[28]

This study has potential limitations. First, we assumed high accuracy with using TNE screening in two thirds of the patients. The accuracy of uTNE in detecting esophageal disease, specifically BE, has been shown in several trials[29,30] and a recent meta-analysis.[31] A randomized cross over trial has also confirmed the accuracy of the EndoSheath technology used in this study.[32] Indeed recent guidelines suggest the use of uTNE as an alternative for BE screening.[4] Furthermore, experienced endoscopists performed all study procedures after developing a consensus on the endoscopic diagnosis of BE. A second potential limitation is combining EE and BE in some of the analyses. Given that EE is a known potential precursor of BE and EAC,[19–21] combining these outcomes was thought to be an acceptable analysis method. Corroboration in an independent validation cohort with addition of other biomarkers would be essential for widespread clinical application of these models.[33,34]

EE and BE are likely multifactorial diseases rather than singularly caused by gastroesophageal reflux. This study supports this conclusion that targeting only subjects with reflux symptoms is likely an inefficient method of screening for BE.[13] The continued use of models which incorporate additional easy to collect demographic and clinical data may more accurately and cost effectively identify subjects at risk who would derive benefit from esophageal screening to detect esophageal neoplasia and its precursors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

This study was funded in part by NIH grant (RC4DK090413)

This publication was also made possible by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Appendix 1. Symptomatic GER Questions from GERQ

How many times have you had a burning pain or discomfort behind the breast bone in your chest in the last year? (Please do NOT count pain in your stomach or pain from heart trouble.)

How many times have you had acid regurgitation in the last year?

How many times have you taken antacids (like Amphojel, AlternaGEL, Gaviscon, Maalox, Mylanta, Riopan, Rolaids, or Tums) in the last year?

Have you taken any of the following over-the-counter medications in the last year: Axid AR (nizatidine), Pepcid AC (famotidine), Tagamet HB (cimetidine), or Zantac (ranitidine)? If yes, how many times?

Have you taken any of the following medications in the last year with a doctor’s prescription: Prevacid (lansoprazole), Prilosec (omeprazole), Propulsid (cisapride), Protonix (pantoprazole), Aciphex (rabeprazole)? If yes, how many times?

** Each question had 5 possible answers: less than once a week, about once a month, about once a week, several times a week, and daily.

Footnotes

Potential competing interests:

No authors have any conflicts to declare.

Guarantor of the article:

Dr. Prasad Iyer accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study.

Specific Author Contributions:

Nicholas R. Crews contributed to analysis, interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript.

Michele L. Johnson contributed to the acquisition of data, analysis.

Cathy D. Schleck contributed to acquisition of data and data analysis

Felicity T. Enders contributed to acquisition of data and data analysis

Louis-Michel Wongkeesong contributed to acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content Kenneth K. Wang contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

David A. Katzka contributed to acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Prasad G. Iyer contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, obtained funding, study supervision.

All Authors approved final version of this article, including authorship list.

References

- 1.Pohl H, Sirovich B, Welch HG. Esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence: Are we reaching the peak? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1468–1470. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das A, Singh V, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK. A comparison of endoscopic treatment and surgery in early esophageal cancer: An analysis of surveillance epidemiology and end results data. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2008;103:1340–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, Ang Y, Kang JY, Watson P, Trudgill N, Patel P, Kaye PV, Sanders S, O’Donovan M, Bird-Lieberman E, Bhandari P, Jankowski JA, Attwood S, Parsons SL, Loft D, Lagergren J, Moayyedi P, Lyratzopoulos G, de Caestecker J. British society of gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB. Acg clinical guideline: Diagnosis and management of barrett’s esophagus. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteman DC, Sadeghi S, Pandeya N, Smithers BM, Gotley DC, Bain CJ, Webb PM, Green AC. Combined effects of obesity, acid reflux and smoking on the risk of adenocarcinomas of the oesophagus. Gut. 2008;57:173–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.131375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor JB, Rubenstein JH. Meta-analyses of the effect of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux on the risk of barrett’s esophagus. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2010;105:1729. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.194. 1730-1727; quiz 1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubenstein JH, Scheiman JM, Sadeghi S, Whiteman D, Inadomi JM. Esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence in individuals with gastroesophageal reflux: Synthesis and estimates from population studies. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011;106:254–260. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Vieth M, Stolte M, Talley NJ, Agreus L. Prevalence of barrett’s esophagus in the general population: An endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1825–1831. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Achem SR, Loeb DS, Krishna M, Hemminger LL, DeVault KR. Barrett’s esophagus is common in older men and women undergoing screening colonoscopy regardless of reflux symptoms. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101:12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zagari RM, Fuccio L, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Fiocca R, Casanova S, Farahmand BY, Winchester CC, Roda E, Bazzoli F. Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, oesophagitis and barrett’s oesophagus in the general population: The loiano-monghidoro study. Gut. 2008;57:1354–1359. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.145177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Sharma AN, Murad MH, Buttar NS, El-Serag HB, Katzka DA, Iyer PG. Central adiposity is associated with increased risk of esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer PG, Borah BJ, Heien HC, Das A, Cooper GS, Chak A. Association of barrett’s esophagus with type ii diabetes mellitus: Results from a large population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1108–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.024. e1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubenstein JH, Morgenstern H, Appelman H, Scheiman J, Schoenfeld P, McMahon LF, Jr, Metko V, Near E, Kellenberg J, Kalish T, Inadomi JM. Prediction of barrett’s esophagus among men. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;108:353–362. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thrift AP, Kendall BJ, Pandeya N, Whiteman DC. A model to determine absolute risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.026. e132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sami SS, Dunagan KT, Johnson ML, Schleck CD, Shah ND, Zinsmeister AR, Wongkeesong LM, Wang KK, Katzka DA, Ragunath K, Iyer PG. A randomized comparative effectiveness trial of novel endoscopic techniques and approaches for barrett’s esophagus screening in the community. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:539–547. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, Bergman JJ, Gossner L, Hoshihara Y, Jankowski JA, Junghard O, Lundell L, Tytgat GN, Vieth M. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for barrett’s esophagus: The prague c & m criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal FT, Galmiche JP, Lundell L, Margulies M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, Tytgat GN, Wallin L. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: A progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85–92. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Vieth M, Agreus L, Aro P. Erosive esophagitis is a risk factor for barrett’s esophagus: A community-based endoscopic follow-up study. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011;106:1946–1952. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanna S, Rastogi A, Weston AP, Totta F, Schmitz R, Mathur S, McGregor D, Cherian R, Sharma P. Detection of barrett’s esophagus after endoscopic healing of erosive esophagitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101:1416–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modiano N, Gerson LB. Risk factors for the detection of barrett’s esophagus in patients with erosive esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishida C, Ko GT, Kumanyika S. Body fat distribution and noncommunicable diseases in populations: Overview of the 2008 who expert consultation on waist circumference and waist-hip ratio. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:2–5. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, Cumings MD, Wong RK, Vasudeva RS, Dunne D, Rahmani EY, Helper DJ. Screening for barrett’s esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1670–1677. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerson LB, Banerjee S. Screening for barrett’s esophagus in asymptomatic women. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katzka DA, Castell DO. Successful elimination of reflux symptoms does not insure adequate control of acid reflux in patients with barrett’s esophagus. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1994;89:989–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corley DA, Kubo A. Body mass index and gastroesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101:2619–2628. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett C, Moayyedi P, Corley DA, DeCaestecker J, Falck-Ytter Y, Falk G, Vakil N, Sanders S, Vieth M, Inadomi J, Aldulaimi D, Ho KY, Odze R, Meltzer SJ, Quigley E, Gittens S, Watson P, Zaninotto G, Iyer PG, Alexandre L, Ang Y, Callaghan J, Harrison R, Singh R, Bhandari P, Bisschops R, Geramizadeh B, Kaye P, Krishnadath S, Fennerty MB, Manner H, Nason KS, Pech O, Konda V, Ragunath K, Rahman I, Romero Y, Sampliner R, Siersema PD, Tack J, Tham TC, Trudgill N, Weinberg DS, Wang J, Wang K, Wong JY, Attwood S, Malfertheiner P, MacDonald D, Barr H, Ferguson MK, Jankowski J. Bob cat: A large-scale review and delphi consensus for management of barrett’s esophagus with no dysplasia, indefinite for, or low-grade dysplasia. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2015;110:662–682. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.55. quiz 683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benaglia T, Sharples LD, Fitzgerald RC, Lyratzopoulos G. Health benefits and cost effectiveness of endoscopic and nonendoscopic cytosponge screening for barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:62–73. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.060. e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peery AF, Hoppo T, Garman KS, Dellon ES, Daugherty N, Bream S, Sanz AF, Davison J, Spacek M, Connors D, Faulx AL, Chak A, Luketich JD, Shaheen NJ, Jobe BA. Feasibility, safety, acceptability, and yield of office-based, screening transnasal esophagoscopy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:945–953. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.021. e942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saeian K, Staff DM, Vasilopoulos S, Townsend WF, Almagro UA, Komorowski RA, Choi H, Shaker R. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy accurately detects barrett’s metaplasia and dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:472–478. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sami SS, Subramanian V, FernáNdez-Sordo JO, Saeed A-H, Singh S, Iyer PG, Ragunath K. Sa1495 performance characteristics of unsedated ultrathin video endoscopy in the assessment of the upper gastrointestinal (gi) tract: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 79:AB234. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shariff MK, Varghese S, O’Donovan M, Abdullahi Z, Liu X, Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M. Pilot randomized crossover study comparing the efficacy of transnasal disposable endosheath with standard endoscopy to detect barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2016;48:110–116. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubenstein JH, Thrift AP. Risk factors and populations at risk: Selection of patients for screening for barrett’s oesophagus. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thrift AP, Garcia JM, El-Serag HB. A multibiomarker risk score helps predict risk for barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1267–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.