Abstract

Foamy viruses (FV) are complex retroviruses that possess several unique features that distinguish them from all other retroviruses. FV Gag and Pol proteins are expressed independently of one another, and both proteins undergo single cleavage events. Thus, the mature FV Gag protein does not consist of the matrix, capsid, and nucleocapsid (NC) proteins found in orthoretroviruses, and the putative NC domain of FV Gag lacks the hallmark Cys-His motifs or I domains. As there is no Gag-Pol fusion protein, the mechanism of Pol packaging is different but unknown. FV RNA packaging is not well understood either. The C terminus of FV Gag has three glycine-arginine motifs (GR boxes), the first of which has been shown to have nucleic acid binding properties in vitro. The role of these GR boxes in RNA packaging and Pol packaging was investigated with a series of Gag C-terminal truncation mutants. GR box 1 was found to be the major determinant of RNA packaging, but all three GR boxes were required to achieve wild-type levels of RNA packaging. In addition, Pol was packaged in the absence of GR box 3, but GR boxes 1 and 2 were required for efficient Pol packaging. Interestingly, the Gag truncation mutants demonstrated decreased Pol expression levels as well as defects in Pol cleavage. Thus, the C terminus of FV Gag was found to be responsible for RNA packaging, as well as being involved in the expression, cleavage, and incorporation of the Pol protein.

The process of retroviral assembly is largely driven by the Gag protein. For all Orthoretrovirinae, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), specific domains within the Gag precursor polyprotein regulate the major steps of assembly (reviewed in reference 32). To properly assemble an infectious virus particle, the genomic RNA must be selectively packaged into the virion. This is no easy task given that the viral RNA makes up much less than 1% of the total mRNA pool existing in the cytoplasm of the cell. The regions of viral RNA responsible for orthoretroviral RNA packaging are referred to as the packaging signal (ψ) and are located near the 5′ end of the RNA genome. The packaging signal is believed to comprise both specific sequences and higher-order structural features (3, 4, 28). Viral proteins, in addition to cis-acting sequences, play an important role in viral genomic RNA packaging. The virion nucleocapsid protein (NC) has been shown to be specifically involved in viral genomic RNA dimerization and packaging (12-14, 23). In addition, mutagenesis studies have shown that the basic residues surrounding the Cys-His boxes within NC are critical for RNA packaging for many orthoretroviruses (6, 11, 19, 27, 31).

In contrast, foamy viruses (FV) have a fundamentally different replication strategy. FV are classified as complex retroviruses based largely on their genomic organization and their reverse transcription pathway. A major difference between FV and other retroviruses is the mode of Pol expression. Unlike orthoretroviruses, which express Pol as part of a Gag-Pol fusion protein, FV express Pol independent of Gag, from a separate spliced message (35). Thus, Pol cannot be incorporated into particles via a Gag assembly domain alone. Recent work suggests that a signal near the 5′ end of the viral genomic RNA (CAS I) is required for Pol incorporation (15, 17). Another difference is limited proteolytic processing of FV Gag and Pol proteins. Only two cleavage events are detected in infected cells and virions for the Gag and Pol proteins; Gag cleavage occurs at the C terminus of the protein to release a 3-kDa peptide, and Pol cleavage occurs between the RNase-H domain and the integrase (IN) domain. Thus, FV does not have the mature proteins MA, CA, and NC, and its protease (PR) and reverse transcriptase (RT) act in concert as a fusion protein (reviewed in references 10 and 21).

It is clear that the participation of FV Gag in RNA packaging differs from that of orthoretroviral Gag proteins because the FV Gag protein does not contain a true NC domain with a Cys-His box(es) surrounded by basic residues. Within its putative C-terminal NC region, FV Gag contains three glycine-arginine motifs, termed GR boxes (30). These boxes are the only highly conserved motifs in FV Gag proteins isolated from different species and might serve the same function in RNA packaging as the basic residues surrounding the Cys-His boxes in orthoretroviral NC. In fact, in vitro studies have shown that GR box 1 can bind nucleic acids, while GR box 2 has been shown to have a functional nuclear localization signal (30, 36). At present there is no known function for GR box 3. The location of the FV RNA packaging signal has yet to be clearly defined. Recent work suggests that, unlike what is found for all other retroviruses, ψ is not near the 5′ end of the viral genome (17). Studies designed to determine the minimum requirements for vector transfer have shown that RNA sequences within the pol gene called CAS II are required for RNA packaging (8, 16). Thus, it appears that FV use a uniquely located packaging signal within their genomic RNA.

In the present study, we have investigated the role of the FV GR boxes in RNA encapsidation. Given that the mechanism of FV Pol incorporation must be unique, the role of the FV GR boxes in Pol incorporation was also examined. We found that deletion of the C terminus of Gag has complex effects on the level of Pol expression, which made analysis of its effect on Pol packaging difficult. We also found that the region downstream of GR box 1 does not play a major role in RNA encapsidation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis and cloning.

The panel of Gag C-terminal truncation mutants was generated in viral subclones, and the mutagenized fragments were subsequently cloned into the full-length viral plasmid. The mutations were previously created through PCR mutagenesis of viral subclones pLinkSub1 and pLinkSub2 (1). FV mutants GR3st, GR2st, and GR1st were previously referred to as 74stop, 68stop, and 60stop, respectively. The GR(-) mutation was created similarly to the other mutations with mutagenic PCR primers 50stop1 (5′-GGCCTTAATGCCAGAGGACAAAGTTAATAAGCTAGCCATCGAT-3′) and 50stop2 (5′-CCAGATGCTAGCGTGACTCCTCAACCCCGACCATCC-3′). A unique NheI restriction site was introduced through these primers for easy identification of the mutants. These mutant subclones were all cloned back into the full-length primate FV under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter (pCMV-HFV) with the unique sites for the respective subclone (pLinkSub1, EagI/SwaI; pLinkSub2, SwaI/PacI). Full-length viral constructs containing the mutations were identified by restriction digestion with NheI and confirmed by sequencing.

Cell culture.

Both FAB and 293T cells were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DME) in the presence of 1% penicillin and streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cell transfections were performed with PolyFect reagent (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer's protocol. Cell lysates were generated between 40 and 45 h posttransfection by rinsing cells which were about 90% confluent with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), scraping in antibody buffer (7 μl/mm2 of surface area; 20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), shearing cells with a 23-gauge needle, and centrifuging at 13,800 × g for 10 min in a tabletop microcentrifuge. Viral supernatants were collected, centrifuged at 82 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris, and then pelleted through a 20% sucrose cushion for 2 h at 24,000 rpm and 4°C (Beckman). Viral pellets were resuspended in standard buffer (10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). Titering of viral supernatants was performed with FAB cells as described previously (37).

Western blotting.

SDS sample loading buffer was added to cell lysates and/or viral pellets prior to loading onto a 10% protein gel. After proteins were separated by electrophoresis, they were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked and hybridized with antibodies in a milk-PBS solution containing 0.5% Tween 20, followed by a final rinse in PBS-1.0% Tween 20. Enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were used for signal detection by X-ray film. Quantitative Western blot analysis was performed as described above, but using the stabilized 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Promega) for development. Color development was stopped by rinsing the blot in distilled H2O. The blots were allowed to air dry, and they were scanned and quantitated with ImageQuant software.

RPAs.

An FV long terminal repeat (LTR)-specific riboprobe was in vitro transcribed and radiolabeled from the plasmid pSGC11 linearized with EagI (described in reference 35). RNase protection assays (RPAs) were performed with the Direct Protect RPA kit (Ambion) according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cell lysates and viral pellets were hybridized with the radiolabeled riboprobe overnight, followed by RNase digestion. After proteinase K digestion, samples were precipitated with isopropanol and resuspended in sample buffer. RNAs were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide urea gel, and the gel was dried and exposed to a phosphor screen (Molecular Dynamics) for analysis.

Radioimmunoprecipitation and pulse-chase assays.

Transfected 293T cells were labeled with [35S]methionine in DME lacking Met and Cys (Gibco) 36 h posttransfection. Two hours later, the labeled medium was removed and cells were rinsed with PBS. Cells were either scraped in antibody buffer or fed fresh DME that did not contain label. Eight hours later, these cells were rinsed in PBS and scraped in antibody buffer. Cells were lysed with QiaShredder columns (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer's instructions. [35S]methionine-labeled cell lysates were incubated with an anti-Gag polyclonal antibody or an anti-Pol polyclonal antibody and protein A-Sepharose beads at 4°C with shaking overnight. The bead-antibody-protein complexes were centrifuged at 2,040 × g for 5 min, washed twice with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS), once with high-salt buffer (2 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid), once with RIPA buffer, and once with TE (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA). After the final centrifugation, all liquid was carefully removed and the beads were resuspended in SDS-protein sample loading buffer. Samples were heated at 95°C for 10 min, followed by centrifugation at 4°C. The eluted proteins were separated on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel, and the gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film.

RESULTS

Generation of FV Gag C-terminal truncation mutants.

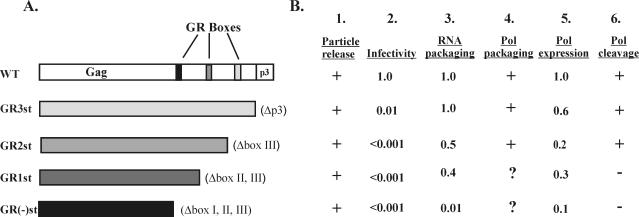

To investigate the functions of the FV Gag GR boxes, a series of C-terminal Gag truncation mutants were created by introducing stop codons downstream of GR box 3 at the p3 cleavage site (GR3st), downstream of GR box 2 (GR2st), downstream of GR box1 (GR1st), and upstream of GR box 1 [GR(-)st] (Fig. 1A). These mutations were created in an FV Gag subclone by PCR mutagenesis, and then the mutagenized fragments were cloned into the full-length FV provirus in which the cytomegalovirus promoter replaces the FV U3 region in the 5′ LTR. The mutant constructs were transfected into 293T cells to verify proper Gag expression. Gag expression was compared to that of IN- FV (22), rather than the wild type (Fig. 2A, lane 1). This mutant lacks IN activity and was chosen because viral proteins are synthesized properly but the resulting virus cannot spread. Since synthesis of gene products is limited to the initial transfected DNA, the amounts of Gag and Pol serve as wild-type levels for comparison with other replication-defective mutants being tested. We found that all of the Gag C-terminal mutants efficiently express the predicted truncated Gag proteins, as determined by Western blot analysis using an anti-Gag antibody (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 to 5). Unlike IN- FV Gag proteins, in which PR cleavage is normal, all of the mutant Gag proteins lack the PR cleavage site and therefore only a single major species is detected.

FIG. 1.

FV Gag C-terminal truncation mutations. (A) Diagram of mutants. The Gag C-terminal truncation mutants were generated by introducing a stop codon just upstream of each of the GR boxes as well as the p3 cleavage site. The resulting mutants were termed GR3st, GR2st, GR1st, and GR(-)st. WT, wild type. (B) Summary of results. Column 1, plus signs indicate that all mutants released particles; columns 2 and 3, infectivity and RNA packaging efficiencies compared to wild type; column 4, plus signs indicate that Pol was detected in virions, and question marks indicate that Pol was not detectable in virions by Western blotting but that packaging remains inconclusive; column 5, Pol expression levels relative to wild type; column 6, Pol cleavage (+) or lack of cleavage (−) within cells.

FIG. 2.

Western blots of 293T transfected-cell lysates and pelleted viral supernatants. (A) An anti-Gag polyclonal antibody was used to detect FV Gag proteins. Lanes 1 and 8, IN- FV; lanes 2 and 9, GR3st; lanes 3 and 10, GR2st; lanes 4 and 11, GR1st; lanes 5 and 12, GR(-)st; lanes 6 and 13, FV ΔEnv; lanes 7 and 14, mock transfection. (B) An anti-Pol monoclonal antibody was used to detect FV Pol proteins (lanes are as described for panel A).

Particle release.

The multimerization of Gag proteins within the cytoplasm initiates the process of FV capsid assembly and leads to viral release. To determine whether our panel of Gag C-terminal protein deletion mutants were still able to form and release particles properly, Western blotting with the anti-Gag antibody was performed on pelleted viral supernatants from the transiently transfected 293T cells, as shown in Fig. 2A. Gag proteins of the appropriate size were detected in the pelleted viral supernatants for each of the mutants (Fig. 2A, lanes 9 to 12), in amounts equal to, or somewhat less than, those for the IN- control, (Fig. 2A, lane 8). To control for nonspecific release of viral proteins into the supernatants, the behavior of another mutant, ΔEnv, was also examined. Primate FV cannot release particles in the absence of the Env glycoproteins (2, 9), and therefore any Gag in the supernatant of ΔEnv-transfected cells would be indicative of cell lysis. We found that ΔEnv synthesizes Gag protein in the cell (Fig. 2A, lane 6), but no viral particles were seen in the culture supernatant (Fig. 2A, lane 13), indicating that particle formation is required for detection of viral Gag in culture supernatants. Thus, the C terminus of the FV Gag protein is not absolutely required to assemble and release virus particles.

Infectivity.

A previous publication reported approximately a 2-log-unit reduction in infectivity for the GR3st mutant lacking the p3 peptide (7). Given that our panel of truncation mutants all lack the p3 peptide, we hypothesized that these mutants would also have reduced infectivity. To test this, we infected FAB indicator cells with supernatants after transfection of 293T cells. The results confirmed a 2-log-unit reduction in titer for the GR3st mutant. In contrast, none of the other truncation mutants had any measurable titer (Fig. 1B). Thus, while the C terminus of the FV Gag protein (including the three GR boxes) is not required for particle assembly and release, it is very important for viral infectivity. A viral mutant which lacks only GR box 2, known as H3RR, has previously been shown to be reduced less than 1 log unit in infectious titer (36). Therefore, the more profound effect of GR2st on infectivity reflects the removal of p3 and other downstream sequences.

RNA packaging.

A possible explanation for the lack of infectivity in the Gag truncation mutants is a failure to package viral genomic RNA. Indeed, the absence of GR box 1 was hypothesized to disrupt Gag interaction with the viral genomic RNA (36). To determine whether these mutants package viral RNA as well as to measure the relative packaging efficiencies of each, RPAs and quantitative Western blot analyses were performed. 293T cells were transfected with each mutant provirus plasmid, and both cell lysates and pelleted viral supernatants were collected. Portions of the cell lysates and viral pellets were used in RPAs. The LTR riboprobe (Fig. 3A, 1) used in these analyses distinguishes between the transfected plasmid DNA and viral DNA (Fig. 3A, 2), the 5′ end of the viral genomic RNA (Fig. 3A, 3), and the 3′ end of the viral genomic RNA (Fig. 3A, 4). As a probe synthesis and digestion control, the riboprobe was run on the gel without and with RNase treatment (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2). As expected, the free riboprobe showed the full-length probe of 503 nucleotides (nt) and the RNase-treated riboprobe showed no signal. Each of the cell lysates, with the exception of the mock-transfected lysate (Fig. 3B, lane 9), showed a clear band of 260 nt, representing the 3′ end of the viral genomic RNA, as well as a band of 427 nt, representing the transfected plasmid DNA (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 to 8). These results indicate that the transfections were successful and showed relatively similar efficiencies, although in this particular experiment the level of GR1st was lower than those of the others. In the pelleted-viral-supernatant lanes, the GR3st and GR2st mutants showed protected fragments of 330 and 260 nt, similar in intensity to that of the positive control (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 11 and 12 to 10 [IN-]). In contrast, GR1st showed bands of less intensity (Fig. 3B, lane 13), and no detectable bands were seen for GR(-)st (Fig. 3B, lane 14). The ΔEnv negative control and the mock viral pellets do not show any protected fragments (Fig. 3B, lanes 15 and 16). These results indicate that GR3st and GR2st are able to package RNA well, while GR1st and GR(-)st appear to have a reduced ability to package RNA.

FIG. 3.

RNA packaging efficiencies of FV Gag C-terminal truncation mutants. (A) Diagram of the predicted riboprobe hybridization products. Solid lines, fragments of RNA. (B) RNase protection assay of transfected-cell lysates and pelleted viral supernatants. Lane 1, undigested probe; lane 2, RNase-digested probe; lanes 3 and 10, IN-; lanes 4 and 11, GR3st; lanes 5 and 12, GR2st; lanes 6 and 13, GR1st; lanes 7 and 14, GR(-)st; lanes 8 and 15, ΔEnv; lanes 9 and 16, mock transfection. (C) Quantitative Western blot of cell lysates and pelleted viral supernatants. Sample lane designations are the same as in panel B. (D) Calculated relative packaging efficiencies for the mutants. Samples lanes are the same as in panel B. Values were derived from normalizing viral RNA levels to cellular RNA levels and then normalizing those values to cellular and viral Gag levels. Asterisks indicate that no signal was detected for Gag and that therefore an efficiency could not be calculated.

The second portions of the cell lysate and pelleted viral supernatant samples were used for Gag quantitation. Several anti-Gag RIPA experiments were performed; however the results were in disagreement with those of Western blot analyses, in that there were larger amounts of the mutant proteins than would be expected from the Western blots (compare Fig. 2A and Fig. 4, bottom panel). It is possible that the epitope(s) recognized by the anti-Gag antibody used is more accessible in the mutant Gag proteins under RIPA conditions, which are less denaturing than those used in Western blots. Therefore, to more accurately determine the amount of Gag present in the pelleted viral supernatants, quantitative Western blot analyses were performed using the enzymatic TMB substrate. Serial dilutions of positive-control samples were used to confirm the linear range of the quantitative Western TMB substrate (data not shown). Samples were subjected to Western blotting, and the membrane was probed with a polyclonal anti-Gag antibody and developed with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody along with TMB substrate. All of the mutants expressed similar amounts of the truncated Gag proteins in the cell lysates (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 to 8). However, analysis of the viral samples revealed that the GR1st and GR(-)st mutants released significantly fewer particles (Fig. 3C, lanes 13 and 14). These Western results, along with the RPA results, were quantitated with ImageQuant software. The amount of viral Gag released from the cell was divided by the total amount of Gag expressed in the cell to determine the relative number of particles released for each mutant. Next, the amount of virus-specific RNA in particles was divided by the amount of virus-specific cellular RNA to determine the relative amount of RNA present in the particles of each mutant. Finally, the amount of particle RNA was divided by the relative number of particles released to calculate the relative packaging efficiency of each mutant (Fig. 3C, bottom). The results show that GR3st packages RNA as efficiently as the wild type, while GR2st and GR1st show approximately a twofold decrease in packaging efficiency compared to the wild type. In contrast, the packaging efficiency of GR(-)st is reduced by 2 log units, although this number is based on a low level of viral particles. Thus, it appears that the C terminus of Gag, including the GR boxes, includes sequences important for viral RNA packaging.

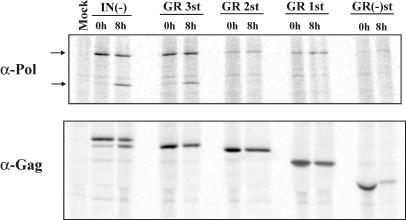

FIG. 4.

Pol expression and stability in the Gag C-terminal truncation mutants. Pulse-chase radiolabeling and immunoprecipitations of transfected-cell lysates. Cells were radiolabeled for 2 h; 0-h samples were immediately harvested, and 8-h samples were chased with unlabeled media for 8 h prior to harvesting. The top panel shows immunoprecipitation with an anti-Pol antibody, and the bottom panel shows immunoprecipitation with an anti-Gag antibody.

Pol packaging.

A poorly understood aspect of the FV life cycle is the mechanism by which the Pol protein is packaged. Recent work has demonstrated that packaging of the viral genomic RNA is necessary for Pol packaging (15). The FV Gag C-terminal truncation mutants described above show various levels of genomic RNA packaging and, therefore, might be expected to also show altered levels of encapsidated Pol protein. The same cell lysates and pelleted viral supernatants used to determine particle release (Fig. 2A) were also used to determine Pol incorporation (Fig. 2B). Western blotting was performed with a newly generated mouse monoclonal antibody against the PR and RT domains of the Pol protein, which was found to be sensitive enough to detect Pol in virus particles from replication-defective proviruses. FV RT is synthesized as part of a PR-RT-IN precursor, which is cleaved to a mature PR-RT fusion protein, and an IN protein. Our serum detects both the precursor and the PR-RT proteins, but not the IN protein, in the wild type (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 6). Only the cleaved PR-RT protein is found in virions (Fig. 2B, lane 8). In the cell, GR3st expresses wild-type levels of both cleaved and full-length forms, and Pol is easily detected in the pelleted viral supernatants of GR3st (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 9). Surprisingly, GR2st and GR1st express significantly lower levels of Pol in the cell and GR(-)st Pol is almost undetectable (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 to 5). GR2st contains Pol in the particles, but at a lower level than that for the wild type (Fig. 2B, lane 10). Another curious finding is that GR1st Pol is found only in the uncleaved form within the cell (Fig. 2B, lane 4). GR1st and GR(-)st do not have any detectable Pol in the particles, even upon overexposure of Western blots (Fig. 2B, lanes 11 and 12, and data not shown). Although it is not possible to quantitate these enhanced chemiluminescence-based Western blots, we can conclude that GR3st expresses and packages Pol efficiently, that GR2st expresses Pol inefficiently but packages some Pol into particles, and that GR1st expresses Pol inefficiently and only as a precursor and there is no detectable Pol in the particles. Finally, GR(-)st does not express detectable levels of Pol in the ell and there is no detectable Pol in the particles. Given the decreased levels of Pol detected in cells with GR1st and GR(-)st, it is not possible to determine whether Pol is packaged in these mutants, since the expected level would be below the limits of detection of the antibody.

Pol expression and stability.

If the C terminus of Gag interacts with the Pol protein and helps stabilize it within the cell, then its loss would lead to normal levels of Pol synthesis but increased protein turnover. Alternatively, if the level of Pol synthesis itself is decreased, there would be less Pol protein detected during a pulse label. To distinguish between these possibilities, pulse-chase experiments were performed. 293T cells were transfected with either the positive IN- control, the four truncation mutants, or a mock plasmid (Fig. 4). Thirty-two hours posttransfection, one set of cells was radiolabeled with [35S]methionine for 2 h, and lysates were harvested for the time zero point. A second set of cells was fed unlabeled medium for another 8 h before harvesting (8-h time point). Cell lysates were divided into two separate samples to be used for immunoprecipitation with either the anti-Gag or anti-Pol antibody. We could not use shorter labeling times as there was insufficient labeling of Pol proteins.

The anti-Pol time zero points were used to quantitatively compare the expression levels of Pol in each of the Gag C-terminal mutants. In addition, the anti-Gag time zero points were used for normalization (Table 1). The results of the 0-h sample quantitations revealed that the expression levels of all of the Gag C-terminal mutants were reduced, compared to that for the IN- control. GR3st showed 64% of control Pol, while GR2st, GR1st, and GR(-)st showed more-dramatic loss of protein expression, ranging from 13 to 32%. These results correspond to the decreased levels of Pol observed by Western blotting.

TABLE 1.

Levels of synthesis and stability of Gag and Pol proteinsd

| Virus | Pol

|

Gag

|

Gag/Polc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expressiona | Stabilityb | Expression | Stability | ||

| IN- | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.59 | 1.0 |

| GR3st | 0.64 | 1.30 | 1.27 | 0.44 | 2.0 |

| GR2st | 0.15 | 0.95 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 4.2 |

| GR1st | 0.32 | 1.01 | 0.80 | 0.42 | 2.5 |

| GR(-)st | 0.13 | 1.19 | 0.77 | 0.40 | 5.9 |

Expression levels were calculated from the time zero points in Fig. 4, relative to that for the IN- mutant.

Stability levels were calculated by comparing the protein level at 8 h relative to that at 0 h for each mutant.

Ratios were determined from the time zero points.

Results are the averages of three experiments.

The anti-Pol 0- and 8-h time points were used to measure Pol stability for each of the Gag C-terminal mutants. It can be seen that, at 8 h, approximately one-half of the PR-RT-IN precursor in the IN- control had been cleaved to the mature PR-RT protein. The amount of Pol present at 8 h (both bands) was divided by the total amount of Pol present at 0 h to determine the percentage of Pol remaining for each mutant. None of the mutants showed a significant difference in the amount of Pol remaining after the 8-h chase (Table 1). Thus, the Gag C-terminal truncations did not affect the stability of the Pol protein, and the observed decreases in Pol levels are likely a result of decreased expression. Similar analyses for the Gag 0- and 8-h time points show that Gag stability is not affected by the Gag C-terminal truncations either, although Gag protein in the cell is less stable than Pol (Table 1). In addition, the anti-Pol 8-h time points confirm the observation that there is no detectable Pol cleavage for either FV GR1st or GR(-)st. These results indicate that the decrease in Pol levels observed in the Gag C-terminal truncation mutants is likely the result of decreased expression levels and not instability of the Pol and/or Gag proteins themselves. We also calculated the relative amounts of Gag and Pol for each mutant (Table 1, last column) and found that the relative amount of Pol was decreased for each mutant.

Finally, in an attempt to determine whether the Gag C-terminal truncation mutants affect Pol expression in cis or in trans, a wild-type Gag construct was cotransfected with each mutant and Western blotting was performed on cell lysates. Anti-Pol Western blots revealed that there were no significant differences in Pol levels when wild-type Gag was present in trans (data not shown). This result shows that the Gag C-terminal truncation mutations affect Pol expression only in cis.

The results presented in this work are summarized in Fig. 1B. We found that RNA packaging was highly reduced in GR(-)st but not the other mutants. Truncation of Gag had profound effects on the level of Pol expression and cleavage so that it was difficult to measure the level of Pol packaging. However, the region removed by the deletion in GR2st, including GR box 3, is not required for Pol encapsidation.

DISCUSSION

A surprising result from our analysis of C-terminal Gag truncation mutants is the altered expression and cleavage of Pol within the cell. The absence of the p3 region in GR3st did not have any affect on Pol expression. However, the other three mutants [GR2st, GR1st, and GR(-)st] exhibited significantly decreased cellular expression of Pol but no alteration in Pol protein stability. FV Pol is translated from a spliced mRNA, and altered utilization of the Pol mRNA splice acceptor site in gag could explain the reduced protein levels. However, the splice acceptor for the spliced Pol RNA is located upstream of the first GR box and all of the Gag C-terminal truncation mutants retain it. Also, because the truncation mutants were generated by the introduction of stop codons, they retain the full RNA sequence in this region. Thus, a finding that splicing is affected would suggest that the region surrounding GR boxes 1 and 2 may have some sequences or secondary structures that contribute to efficient splicing. Another possible explanation for the decreased Pol expression could be that the C terminus of FV Gag is involved in the proper transcription and/or translation of Pol. For example, the small nucleotide changes made in the RNA sequence could affect ribosome scanning, which possibly could be involved in the initiation of Pol translation, although there is currently no experimental support for such a mechanism. In addition to decreased expression of Pol, GR1st and GR(-)st also lacked cleavage of the Pol PR-RT-IN precursor. Although the requirements for activation of PR and the resulting cleavage events are poorly understood for FV, in the complete absence of the FV Gag protein, Pol is efficiently cleaved (C. R. Stenbak and M. L. Linial, unpublished data), showing that PR activation and cleavage are independent of the Gag protein. Thus, lack of cleavage is specific to the C-terminal truncation mutants.

The NC protein of orthoretroviruses, which is at or near the C terminus of Gag, has been shown to have many important roles in the retroviral life cycle, both as a mature NC protein and as part of the Gag precursor protein. Previous work from a large number of laboratories has shown that NC is important for orthoretroviral assembly (reviewed in reference 32). In contrast, the results presented in this work clearly demonstrate that the C terminus of the FV Gag protein is not absolutely required for the assembly or release of particles, although there is a decreased efficiency with the larger truncations [GR1st and GR(-)st]. There is accumulating evidence that nucleic acid is required as a scaffold for orthoretroviral assembly (18, 24, 34, 38), although one recent report suggests that HIV particle assembly can occur in the absence of RNA (33). It is interesting that particle assembly occurs in the mutants lacking GR box 1, as GR box 1 has nucleic acid binding activity in vitro. This suggests that RNA binding is not required for FV assembly and/or that there are additional nucleic acid binding regions in FV Gag. It is known that other aspects of FV assembly differ from those of orthoretroviruses and bear similarities to those of hepadnaviruses. FV and hepadnaviruses package RNA, but mature particles contain DNA genomes, lack structural-protein cleavage, and require envelope glycoprotein incorporation for particle release (reviewed in reference 20). The removal of a stretch of arginine-rich residues in the hepatitis B virus Gag-equivalent core protein resulted in assembly of viral particles but reduced abilities to package the pregenome and replicate (25), similar to what is demonstrated here for FV.

The C terminus of FV Gag was found to be critical for viral infectivity. This is similar to what has been observed with other retroviruses. For example, it has been reported that HIV type 1 can form particles efficiently with a large region of NC deleted, yet these particles were noninfectious and deficient in genomic RNA (26). This is not the case for the FV Gag truncation mutants described here, as the GR3st, GR2st, and GR1st truncation mutants all package genomic RNA at only moderately reduced levels compared to wild-type FV. These results suggest that the FV particles with Gag C-terminal truncations up to GR box 1 are noninfectious for a reason other than a defect in RNA packaging. Clearly GR2st, GR1st, and GR(-)st all express lower levels of Pol and do not appear to package Pol in the particles, which would result in an inability to replicate. However, GR3st also shows a 2-log-unit reduction in infectivity, although it appears to package RNA and Pol efficiently. This contrasts with what was found for a mutant in which GR box 3 was replaced by a sequence encoding an epitope tag, for which infectivity was near that of the wild type (36), suggesting that the defect in GR3st is related to removal of p3. It is not known whether the p3 domain is important in the context of the full-length Gag protein, as a cleaved peptide, or both. Based on the proper cleavage of Pol in cells transfected with GR3st, it is clear that the viral PR is active in the absence of p3 (Fig. 2B). Our earlier work showed that an internal deletion of the second GR box led to at most a 10-fold decrease in FV infectivity (36). Thus, the more-profound effects seen in the present study after removal of the GR box 2 region in GR2st and GR1st result from the deletion of this region as well as all of the downstream sequences rather than just the GR-rich region.

It is known that orthoretroviral NC proteins facilitate tRNA incorporation, tRNA placement, and efficient reverse transcription as well as promoting integration (reviewed in reference 5). While FV Gag is not cleaved into a mature NC protein, the C terminus of FV Gag may come into contact with the RNA genome within the virion and facilitate some aspects of reverse transcription. Previous work has shown that FV replication requires a highly active RT, such that a moderate reduction in RT activity results in a block to replication (29). Similarly, the absence of p3 could reduce the efficiency of reverse transcription enough to result in a significant reduction in infectivity.

Gag GR box 1 has nucleic acid binding activity in vitro, which suggests that it would be the major determinant of genomic RNA packaging in vivo (36). Indeed, the data presented here show that GR box 1 alone was sufficient for 40% of wild-type levels of RNA packaging. This is in contrast to the packaging levels of ca. 1% of wild-type levels in the absence of all GR boxes. The in vitro studies found no function associated with GR box 3; however, the work presented here shows that the region encompassing GR box 3 and the downstream sequences is required to achieve wild-type levels of RNA packaging. In contrast to the GR boxes, the p3 peptide does not appear to play any role in RNA packaging for FV.

The fact that FV express the Pol protein independently of the Gag protein presents a unique dilemma for FV. Orthoretroviruses use the fusion of Pol with Gag to ensure the encapsidation of Pol into assembling virus particles via Gag assembly domains. FV, on the other hand, must have a different mechanism that actively and specifically incorporates Pol proteins into virions. A region in U5 that appears to be involved in either Pol packaging or PR activation, termed CAS I, has been identified (17). There is also recent evidence strongly suggesting that genomic RNA is required for Pol incorporation (15). It remains unclear whether domains within the Gag protein are also important, but it is possible that a tertiary complex of Gag, Pol, and viral RNA is required for the proper packaging of the Pol protein. The analysis of the Gag C-terminal truncation mutants for their ability to package Pol found that GR3st and GR2st both package Pol. Pol was undetectable in particles of GR1st and GR(-)st; however, it is unclear if this finding is due to the decreased expression levels of Pol in these mutants. While GR2st shows decreased expression of Pol, it is still able to package Pol, albeit at lower levels. Presumably, full-length Pol is incorporated into particles, where it then undergoes cleavage, but this has not been formally demonstrated. Thus, it remains possible, though unlikely, that GR1st and GR(-)st do not package Pol because the Pol proteins of these mutants are not cleaved within the cell and only the PR-RT and IN cleavage products are packaged independently.

While the importance of the C terminus including the GR boxes for packaging RNA is clear from these studies, the mechanism of Pol expression, cleavage, and incorporation remains to be fully determined. This work supports previous work showing that a Pol-RNA interaction is involved in packaging Pol (15, 17). We have shown that GR box 1 and/or nearby sequences are required for RNA packaging and that the region encompassing all three GR boxes is required for efficient RNA packaging. Additionally, it appears that the region containing GR boxes 1 and 2 contributes to Pol packaging. Interaction of Gag with Pol could be required for Pol binding to a cis-acting RNA sequence and its incorporation into virions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alison Yu, Jacqueline Roy, Michael Emerman, and Julie Overbaugh for insightful comments and Dior Kingston for assistance with some of the experiments.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant CA 18282 from the National Cancer Institute to M.L.L. C.R.S. was partially supported by training grant CA 09229 from the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin, D. N. 1999. Mechanisms of Pol expression and assembly for human foamy virus. Ph.D. thesis. University of Washington, Seattle.

- 2.Baldwin, D. N., and M. L. Linial. 1998. The roles of Pol and Env in the assembly pathway of human foamy virus. J. Virol. 72:3658-3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks, J. D., K. L. Beemon, and M. L. Linial. 1997. RNA regulatory elements in the genomes of simple retroviruses. Semin. Virol. 8:194-204. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beasley, B. E., and W. S. Hu. 2002. cis-acting elements important for retroviral RNA packaging specificity. J. Virol. 76:4950-4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkowitz, R., J. Fisher, and S. P. Goff. 1996. RNA packaging. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 214:177-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dannull, J., A. Surovoy, G. Jung, and K. Moelling. 1994. Specific binding of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein to PSI RNA in vitro requires N-terminal zinc finger and flanking basic amino acid residues. EMBO J. 13:1525-1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enssle, J., N. Fischer, A. Moebes, B. Mauer, U. Smola, and A. Rethwilm. 1997. Carboxy-terminal cleavage of the human foamy virus Gag precursor molecule is an essential step in the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 71:7312-7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erlwein, O., P. D. Bieniasz, and M. O. McClure. 1998. Sequences in pol are required for transfer of human foamy virus-based vectors. J. Virol. 72:5510-5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer, N., M. Heinkelein, D. Lindemann, J. Enssle, C. Baum, E. Werder, H. Zentgraf, J. G. Muller, and A. Rethwilm. 1998. Foamy virus particle formation. J. Virol. 72:1610-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flugel, R. M., and K.-I. Pfrepper. 2003. Proteolytic processing of foamy virus Gag and Pol proteins, p. 63-88. In A. Rethwilm (ed.), Foamy viruses. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Fu, X. D., P. T. Tuazon, J. A. Traugh, and J. Leis. 1988. Site-directed mutagenesis of the avian retrovirus nucleocapsid protein, pp 12, at serine 40, the primary site of phosphorylation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 263:2134-2139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorelick, R. J., D. J. Chabot, D. E. Ott, T. D. Gagliardi, A. Rein, L. E. Henderson, and L. O. Arthur. 1996. Genetic analysis of the zinc finger in the Moloney murine leukemia virus nucleocapsid domain: replacement of zinc-coordinating residues with other zinc-coordinating residues yields noninfectious particles containing genomic RNA. J. Virol. 70:2593-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorelick, R. J., L. E. Henderson, J. P. Hanser, and A. Rein. 1988. Point mutants of Moloney murine leukemia virus that fail to package viral RNA: evidence for specific RNA recognition by a “zinc finger-like” protein sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:8420-8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorelick, R. J., S. M. Nigida, Jr., J. W. Bess, Jr., L. O. Arthur, L. E. Henderson, and A. Rein. 1990. Noninfectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants deficient in genomic RNA. J. Virol. 64:3207-3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinkelein, M., C. Leurs, M. Rammling, K. Peters, H. Hanenberg, and A. Rethwilm. 2002. Pregenomic RNA is required for efficient incorporation of Pol polyprotein into foamy virus capsids. J. Virol. 76:10069-10073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinkelein, M., M. Schmidt, N. Fischer, A. Moebes, D. Lindemann, J. Enssle, and A. Rethwilm. 1998. Characterization of a cis-acting sequence in the pol region required to transfer human foamy virus vectors. J. Virol. 72:6307-6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinkelein, M., J. Thurow, M. Dressler, H. Imrich, D. Neumann-Haefelin, M. O. McClure, and A. Rethwilm. 2000. Complex effects of deletions in the 5′ untranslated region of primate foamy virus on viral gene expression and RNA packaging. J. Virol. 74:3141-3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, M. C., H. M. Scobie, Y. M. Ma, and V. M. Vogt. 2002. Nucleic acid-independent retrovirus assembly can be driven by dimerization. J. Virol. 76:11177-11185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, E.-G., A. Alidina, C. May, and M. L. Linial. 2003. Importance of basic residues in binding of Rous sarcoma virus nucleocapside to the RNA packaging signal. J. Virol. 77:2010-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linial, M. L. 1999. Foamy viruses are unconventional retroviruses. J. Virol. 73:1747-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linial, M. L., and S. W. Eastman. 2003. Particle assembly and genome packaging, p. 89-110. In A. Rethwilm (ed.), Foamy viruses. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Meiering, C. D., K. E. Comstock, and M. L. Linial. 2000. Human foamy virus multiple integrations in persistently infected human erythroleukemia cells. J. Virol. 74:1718-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meric, C., and P.-F. Spahr. 1986. Rous sarcoma virus nucleic acid-binding protein p12 is necessary for viral 70S RNA dimer formation and packaging. J. Virol. 60:450-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muriaux, D., J. Mirro, D. Harvin, and A. Rein. 2001. RNA is a structural element in retrovirus particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:5246-5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nassal, M. 1992. The arginine-rich domain of the hepatitis B virus core protein is required for pregenome encapsidation and productive viral positive-strand DNA synthesis but not for virus assembly. J. Virol. 66:4107-4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ott, D. E., L. V. Coren, E. N. Chertova, T. D. Gagliardi, K. Nagashima, R. C. Sowder, D. T. K. Poon, and R. J. Gorelick. 2003. Elimination of protease activity restores efficient virion production to a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid deletion mutant. J. Virol. 77:5547-5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poon, D. T., J. Wu, and A. Aldovini. 1996. Charged amino acid residues of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid p7 protein involved in RNA packaging and infectivity. J. Virol. 70:6607-6616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rein, A. 1994. Retroviral RNA packaging: a review. Arch. Virol. 9(Suppl.):513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rinke, C. S., P. L. Boyer, M. D. Sullivan, S. H. Hughes, and M. L. Linial. 2002. Mutation of the catalytic domain of the foamy virus reverse transcriptase leads to loss of processivity and infectivity. J. Virol.. 76:7560-7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schliephake, A. W., and A. Rethwilm. 1994. Nuclear localization of foamy virus Gag precursor protein. J. Virol. 68:4946-4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmalzbauer, E., B. Strack, J. Dannull, S. Guehmann, and K. Moelling. 1996. Mutations of basic amino acids of NCp7 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 affect RNA binding in vitro. J. Virol. 70:771-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swanstrom, R., and J. W. Wills. 1997. Synthesis, assembly and processing of viral proteins, p. 263-334. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 33.Wang, S. W., K. Noonan, and A. Aldovini. 2004. Nucleocapsid-RNA interactions are essential to structural stability but not to assembly of retroviruses. J. Virol. 78:716-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu, F., S. M. Joshi, Y. M. Ma, R. L. Kingston, M. N. Simon, and V. M. Vogt. 2001. Characterization of Rous sarcoma virus Gag particles assembled in vitro. J. Virol. 75:2753-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu, S. F., D. N. Baldwin, S. R. Gwynn, S. Yendapalli, and M. L. Linial. 1996. Human foamy virus replication—a pathway distinct from that of retroviruses and hepadnaviruses. Science 271:1579-1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu, S. F., K. Edelmann, R. K. Strong, A. Moebes, A. Rethwilm, and M. L. Linial. 1996. The carboxyl terminus of the human foamy virus gag protein contains separable nucleic acid binding and nuclear transport domains. J. Virol. 70:8255-8262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu, S. F., and M. L. Linial. 1993. Analysis of the role of the bel and bet open reading frames of human foamy virus by using a new quantitative assay. J. Virol. 67:6618-6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, Y., H. Qian, Z. Love, and E. Barklis. 1998. Analysis of the assembly function of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein nucleocapsid domain. J. Virol. 72:1782-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]