Abstract

Palindromic sequences (inverted repeats) flanking the origin of DNA replication with the potential of forming single-stranded stem-loop cruciform structures have been reported to be essential for replication of the circular genomes of many prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. In this study, mutant genomes of porcine circovirus with deletions in the origin-flanking palindrome and incapable of forming any cruciform structures invariably yielded progeny viruses containing longer and more stable palindromes. These results suggest that origin-flanking palindromes are essential for termination but not for initiation of DNA replication. Detection of template strand switching in the middle of an inverted repeat strand among the progeny viruses demonstrated that both the minus genome and a corresponding palindromic strand served as templates simultaneously during DNA biosynthesis and supports the recently proposed rolling-circle “melting-pot” replication model. The genome configuration presented by this model, a four-stranded tertiary structure, provides insights into the mechanisms of DNA replication, inverted repeat correction (or conversion), and illegitimate recombination of any circular DNA molecule with an origin-flanking palindrome.

The rolling-circle replication mechanism has been demonstrated in the replication of circular DNAs of phages (32), bacterial plasmids (7, 15), plant geminiviruses (11, 13, 34), and animal DNA viruses (10, 28, 29). The rolling-circle cruciform replication model postulates that a replicator initiation protein (Rep) binds its cognate sequence at the origin of DNA replication, unwinds the double-stranded DNA, and causes extrusion of two single-stranded stem-loops to generate a cruciform structure. Rep then nicks the cognate sequence present in the plus strand to generate a free 3′-OH end for new leading-strand DNA synthesis. During geminivirus replication (11, 13, 34), the closed circular single-stranded genome is first converted to a superhelical double-stranded DNA replication intermediate. The virus-encoded Rep binds to and nicks (indicated by ↓) between the seventh T and the eighth A of a “conserved” nonanucleotide (TAATATT↓AC) at the origin to initiate plus-strand DNA replication. This nonanucleotide is present among all members of the Geminiviridae family and is flanked by two inverted repeat (palindromic) sequences, which can potentially base pair together to form the stems of a cruciform structure during DNA replication.

Similar to geminiviruses, porcine circovirus (PCV) of the Circoviridae family has a closed circular single-stranded DNA genome (21, 35, 40). Two genotypes of PCV have been identified. PCV type 1 (PCV1) is nonpathogenic, while PCV2 has been implicated as the etiological agent of a new disease, named postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (1). The genome nucleotide sequences of a number of PCV1 (1,759 bases) and PCV2 (1,768 bases) isolates (2, 8, 12, 22, 23, 27) have been determined. It has been suggested that the PCV genome is an intermediate between the genomes of geminivirus and plant circovirus (renamed nanovirus) (30, 36) and that animal circovirus was derived from a plant virus (probably a plant nanovirus) that switched hosts (via an insect vector) to infect a vertebrate and then recombined with a vertebrate-infecting virus (probably a single-stranded RNA virus such as a calicivirus) (9).

The origin of PCV1 has been mapped to a 111-bp fragment (20) which contains a nonanucleotide (TAGTATT↓AC) (Fig. 1A) similar to that of geminiviruses. Recent work showed that the PCV2 nonanucleotide (AAGTATT↓AC) can be further condensed to an octanucleotide motif sequence (AxTAxTAC) and is essential for PCV DNA replication (5). This octanucleotide is flanked by a pair of 11-nucleotide palindromic sequences. PCV DNA replication requires two Rep-associated proteins, Rep and Rep′ (REP complex) (2, 3, 18, 19). In vitro experiments showed that PCV1 Rep binds to the right arm of the presumed stem-loop, while both Rep and Rep′ bind to two adjacent, almost perfect 6-nucleotide (CGGCAG or CGTCAG) tandem direct repeats located at nucleotide 13, 19, 30, and 36 (Fig. 1A) (39). However, in vivo analysis demonstrated that Rep may interact with the palindromic stem only via the C nucleotide at positions 3 and 10 (4). The presence of the “conserved” octanucleotide flanked by inverted repeats at the origin and similarities among the Rep proteins essential for virus replication suggest that PCV DNA may replicate via the rolling-circle “cruciform” model proposed for the Mastrevirus genus of the Geminiviridae family (18, 34) with modifications specified by the recently proposed rolling-circle “melting-pot” model (4).

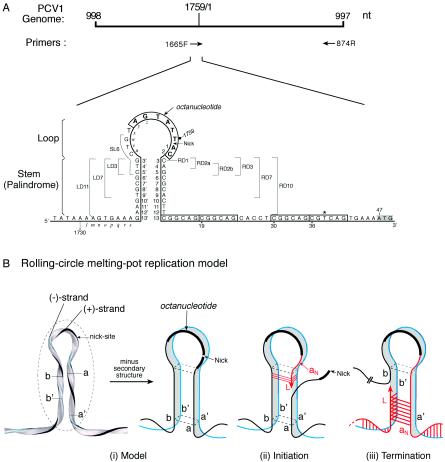

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the PCV1 origin, indicating potential base pairing of the flanking inverted repeats. The locations of the PCR primers are indicated below the PCV1 genome. The genome sequence (1,759 nucleotides) and coordinates (1, 2, 3, etc.) are based on GenBank accession number AY184287 (2). The nucleotide coordinates (3′, 4′, 5′, etc.) are arbitrarily assigned to show the nucleotide complementarity of the palindromic sequences. The octanucleotide containing the presumed nick site (AGTATT↓AC) is boxed and indicated in bold. The palindrome is divided into six regions (right arm, RD3, RD7, and RD10; left arm, LD3, LD7, and LD11). The six-nucleotide tandem repeats located at nucleotides 13, 19, 30, and 36 (not perfect at nucleotide 38 and indicated by an asterisk) are in boxes. Relevant nucleotide sequences are assigned arbitrary positions (l-m-n-o-p-q-r-s and u-v-w-x-y-z) to assist in retracing the templates used during replication. (B) The rolling-circle melting-pot replication model (adopted from reference 4). (i) PCV1 origin after Rep binding to the octanucleotide (prior to nicking) with the plus- and minus-strand genomes in close proximity to each other. The destabilized environment (i.e., the melting pot) is enclosed by a dotted circle. (ii) Schematic representation of the DNA templates available during initiation of DNA replication after removal of the secondary structure in the model. The leading strand (L) displaces strand a and uses strand a′ or strand b as the template. (iii) Schematic representation of the DNA templates available during termination of DNA replication after removal of the secondary structure in the model. The leading strand (L) displaces strand b and uses the newly synthesized strand aN or strand b′ as the template. The plus-strand genome is indicated in black, the minus-strand genome is indicated in blue, and the potential base-pairing opportunities available for the current round of DNA replication are indicated in red.

The origin configuration of the melting-pot model differs from that of the rolling-circle cruciform model. In the melting-pot model, the REP complex binds its cognate sequence (AGTATT↓AC), which is embedded in the 12-nucleotide loop sequence of the superhelical double-stranded replication intermediate PCV1 genome. This REP complex destabilizes and unwinds the origin sequence, nicks the octanucleotide between the sixth T and the seventh A, and generates a free 3′-OH end for new leading-strand DNA synthesis. There is no formation of a cruciform structure. Instead, the REP complex induces a sphere of instability, the melting pot, which encompasses the loop and the palindrome (Fig. 1B-i). Within this destabilized environment, all four strands of the inverted repeats (strands a, a′, b, and b′) are in a “melted” state and are juxtaposed in a four-stranded tertiary structure.

After the REP complex nicks the octanucleotide, DNA replication proceeds with the leading strand descending into the palindromic stem portion of the melting pot through the right arm and displacing the old strand a. Both minus-genome strand a′ and inverted repeat strand b are available as templates (Fig. 1B-ii). For DNA termination, the leading strand ascends into the melting pot through the left arm to displace the old strand b. Both the minus-genome strand b′ and the newly synthesized palindromic strand aN are available as templates (Fig. 1B-iii). Therefore, two DNA strands are available as templates via template strand switching (i.e., from the minus genome to the corresponding palindromic strand) during initiation as well as termination of DNA replication. For this reason, the rolling-circle melting-pot replication model permits the use of either the left-arm or right-arm inverted sequence to regenerate the wild-type palindrome (inverted repeat correction, previously referred as gene correction) (38) or to adopt a mutilated sequence to form a new palindrome (inverted repeat conversion) in the progeny virus (4).

In this study, the experiments were designed to examine the mechanisms involved in palindrome regeneration by self-DNA replication during production of infectious progeny viruses. This was done via deletion mutagenesis of either or both arms of the 11-nucleotide palindrome present at the origin of PCV1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell and virus propagation.

Viruses were propagated in PCV1-free PK15 cell lines maintained in minimal essential medium-Hank's balanced salt solution (MEM-H) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum.

DNA mutagenesis.

Specific deletions were introduced into the cloned PCV1 genome according to the manufacturer of the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, San Diego, Calif.). The primer sets for mutagenesis were designed to contain 14 to 20 identical nucleotides on either side of the predetermined deletion (indicated by lowercase letters), and only one strand of each mutagenic primer set is listed. The primers were as follows: LD3, AAAAGTGAAAGAAGTGCG(ctg)CTGTAGTATTACCAGCGCA; SL6, AAAAGTGAAAGAAGTGCG(ctgctg)TAGTATTACCAGCGCACT; LD7, CTATAAAAGTGAAAGAAG(tgcgctg)CTGTAGTATTACCAGCGCA; LD11, CATCCTATAAAAGTGAAA(gaagtgcgctg)CTGTAGTATTACCAGCGCA; RD1, TGCTGTAGTATTAC(c)AGCGCACTTCGGCA; RD2a, TGCTGTAGTATTAC(ca)GCGCACTTCGGCAG; RD2b, TGCTGTAGTATTACC(ag)CGCACTTCGGCAG; RD3, CGCTGCTGTAGTATTAC(agc)CGCACTTCGGCAGCGGCA; RD7, TGCGCTGCTGTAGTATTAC(cagcgca)CTTCGGCAGCGGCAGCACC; RD10, TGCGCTGCTGTAGTATTAC(cagcgcactt)CGGCAGCGGCAGCACCTC; Del3, TAAAAGTGAAAGAAGTGCG(ctg)CTGTAGTATTAC(agc)CGCACTTCGGCAGCGGCAG; Del7, TCCTATAAAAGTGAAAGAAG(tgcgctg)CTGTAGTATTAC(cagcgca)CTTCGGCAGCGGCAGCACCT; and Del10, TCATCCTATAAAAGTGAAAG(aagtgcgctg)CTGTAGTATTAC(cagcgcactt)CGGCAGCGGCAGCACCTCGG.

Transfection.

After the viral genome was excised from the Bluescript plasmid and recircularized by T4 DNA ligase, the ligated DNA mixture was transfected into PK15 cells which had been seeded into 48-well tissue culture plates so that approximately 60 to 80% confluency was reached 24 h later. Transfection of the ligated DNA mixture (0.5 μg) was carried out with a commercially available Lipofectamine reagent (30 μg/ml) in MEM-H. The DNA/Lipofectamine mixture (0.3 ml) was dispensed into each culture which had been freshly rinsed with MEM-H. After incubation for 5 h at 37 C, the DNA-Lipofectamine mixture was replaced with MEM-H with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Immunochemical staining.

PK15 monolayer cells seeded in 48-well culture plates were infected with virus or transfected with DNA. At 48 h, the cells were rinsed with water, fixed in a phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 40% acetone and 0.2% bovine serum albumin (−20°C) for 10 min, and dried for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then incubated with a hyperimmune swine serum that reacts with the Rep-associated proteins of PCV1 (2) diluted in binding buffer (0.01% Tween 20 and 0.5 M NaCl in phosphate-buffered saline) for 1 h at room temperature, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBSW), incubated with protein G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000) (Zymed Labs, Inc., San Francisco, Calif.) for 30 min, and rinsed with PBSW twice. Color development was carried out with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole and hydrogen peroxide in 0.05 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5). Viral antigens were stained reddish brown in this assay.

PCR.

Total cell DNAs were isolated with the STAT-60 DNA extraction kit purchased from Tel-Text B, Inc. (Friendswood, Tex.). The cells were lysed and extracted with chloroform according to the manufacturer's instructions. The origin sequence was amplified with oligonucleotide primers 1665F (CCAAGATGGCTGCGGGGG) and 874R (GTAATCCTCCGATAGAGAGC) (2). PCR was carried out with 1 μg of DNA in the presence of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 0.2 mM each of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 100 pM each of the primers, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase. The reaction mixture was amplified for 45 cycles at 94°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 70°C for 30 s and then kept at 70°C for 10 min.

RESULTS

Construction of mutant genomes.

A previously described PCV1 genomic clone (J1) (2, 3) was employed to construct the mutated genomes used in this study. A schematic representation of the single-stranded plus-strand origin is denoted in Fig. 1A. The octanucleotide sequence encompassing the presumed nick site between the first nucleotide (position 1) and the last nucleotide (position 1759) is enclosed in a box. A series of mutations were engineered into the right arm (starting at nucleotide 3 of the genomic sequence) (2), the left arm, or both arms of the palindrome to destabilize the potential stem-loop structure. A collection of 13 mutant genomes, organized into three groups, were constructed. Those in the left arm are named LDx, those in the right arm are named RDx, and those in both arms are named Delx. For the LD and RD genomes, x indicates the number of bases deleted; for the Del mutant genomes, x indicates the number of palindromic base pairs deleted. An SL6 mutant genome with a six-nucleotide (CTGCTG) deletion at the stem-loop junction of the left arm was also constructed.

To assist in tracing the template used during DNA synthesis, the relevant viral sequences were assigned arbitrary positions (Fig. 1A). After excision and recircularization, the viral genomes were transfected into PK15 cells and then assayed for viral protein synthesis and progeny virus production.

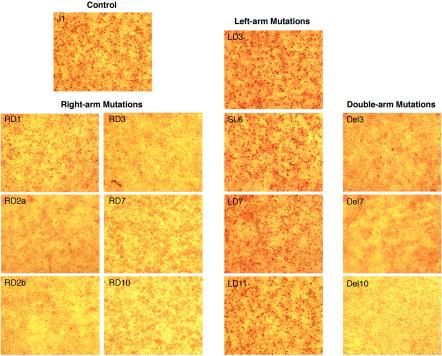

Viral protein synthesis.

Transfected cultures were assayed at 48 h for Rep-associated protein by immunochemical staining with a hyperimmune swine serum (3, 6). In comparison with the parent J1 genome, an equivalent number of Rep-associated antigen-producing cells were detected with the left-arm deletion genomes (LD3, SL6, LD7, and LD11), while the number of Rep-associated antigen-producing cells was greatly reduced with the right-arm deletion genomes (RD1, RD2a, RD2b, RD3, RD7, and RD10) and the double-arm deletion genomes (Del3, Del7, and Del10) (Fig. 2). The number of Rep-associated antigen-producing cells exhibited by RD1, RD2b, and the rest of the RD and Del mutant genomes was 25%, <10%, and <1% of that with J1, respectively. It was interesting that the two-nucleotide deletion (CA) in RD2a (1% of J1) that involved the C nucleotide at position 3 had a more inhibitory effect than the two-nucleotide deletion (AG) in RD2b (10% of J1) that did not involve the C nucleotide at position 3.

FIG. 2.

Immunochemical staining of Rep-associated antigens in PK15 cells transfected with deletion genomes. The input genome is indicated in each panel.

Progeny virus production.

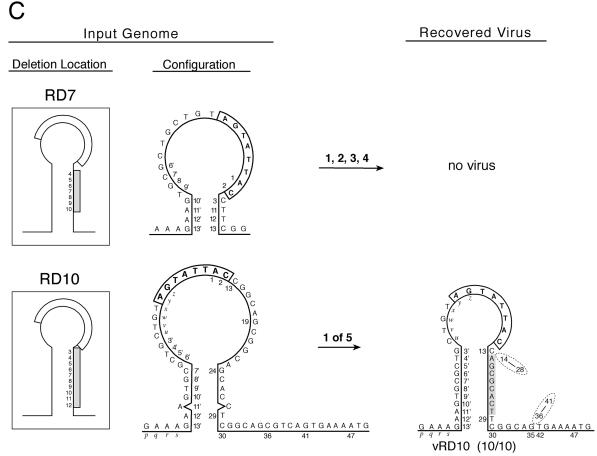

At 7 days, a set of parallel transfected cultures were harvested, frozen and thawed three times, and then assayed for progeny virus by immunochemical staining after passage on fresh PK15 cells for 48 h. Infectious viruses were readily recovered in the cultures transfected with the left-arm deletion genomes LD3, SL6, LD7, and LD11. For the right-arm deletion genomes, fewer viruses were recovered from RD1, RD2a, and RD2b in comparison with parent J1, and none were detected with the RD3, RD7, or RD10 or with any of the double-arm mutant genomes immediately after transfection. However, a small number of progeny viruses evidently were produced with RD3, Del3, and RD10, because after an additional two to three cell passages, infectious viruses were recovered from RD3 and Del3 (two out of two experiments) and occasionally from RD10 (one of five experiments).

Genotype of recovered progeny viruses.

After three cell passages and confirmation by immunochemical staining, virus-infected cell DNAs were isolated and amplified by PCR with PCV1-specific primers 1665F and 874R (Fig. 1A). Each PCR product was subcloned into a TA cloning plasmid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) for nucleotide sequence determination. A collection of 22 viruses with various palindromic sequences were obtained (Fig. 3 to 5). To retrace the DNA strand used as the template during synthesis of the palindromic sequences in each of the recovered viruses, the following criteria were used: (i) template strand switching was invoked as little as possible and only when the minus genome could not possibly be the template, (ii) template-dependent DNA replication along the same template was favored as long as possible, and (iii) a large single deletion had priority over multiple small deletions. Sequences derived from their respective palindromic templates via template strand switching are shaded but not labeled, illegitimate nucleotide are circled, and deleted nucleotide are enclosed in dotted ovals.

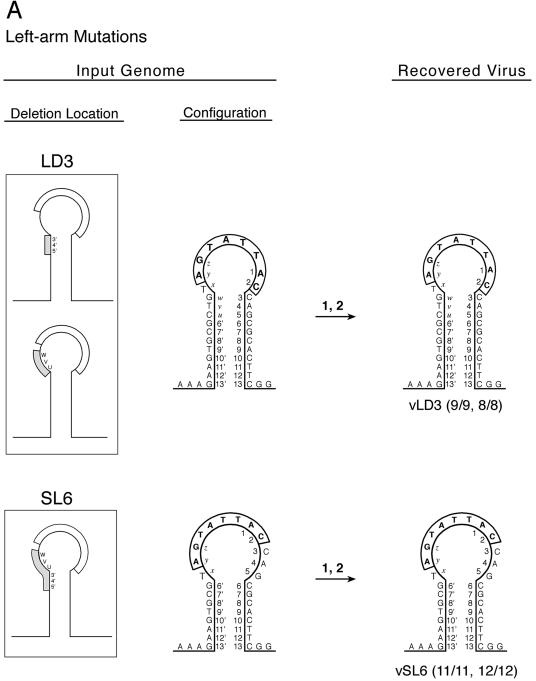

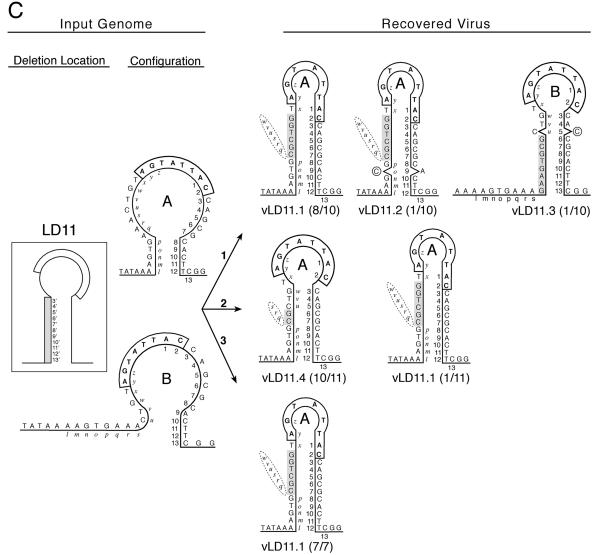

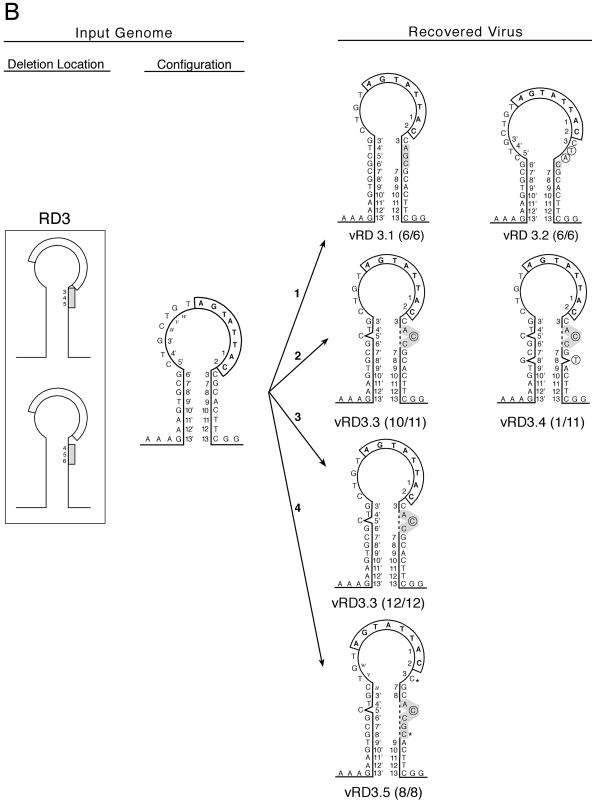

FIG. 3.

Input genomes and recovered viruses from left-arm mutations. For the input genome, the location of the engineered deletion and the potential configuration(s) of each genome are presented at the left of each panel. The octanucleotide sequences are enclosed in boxes, and the inverted repeat sequences regenerated via template strand switching are shaded but not labeled. “Illegitimate” nucleotides are circled. Deletions are indicated by dotted ovals. The dotted line in the palindrome indicates possible duplication of the preceding sequence. The C3 and C10 nucleotides of vRD3.5 are indicated by asterisks. The number of examples (specific subclones/total number recovered) of each recovered virus, determined by sequencing cloned PCR fragments, is indicated in parentheses.

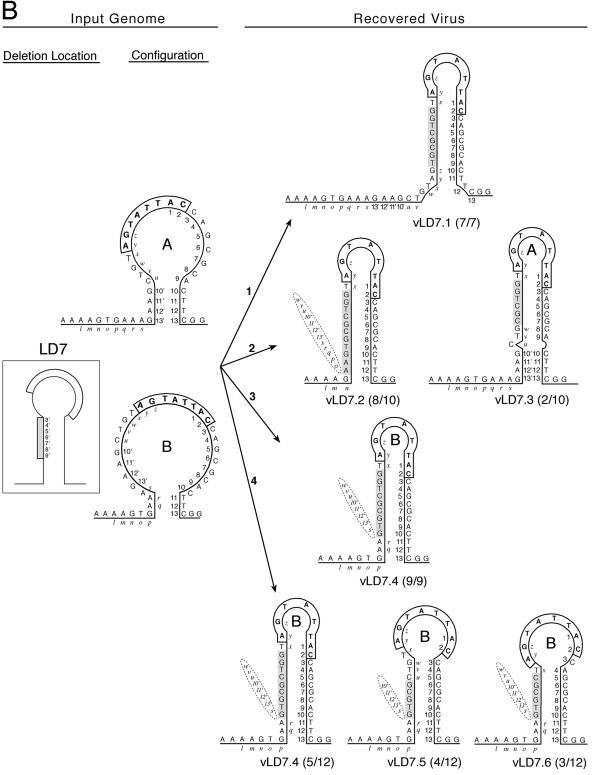

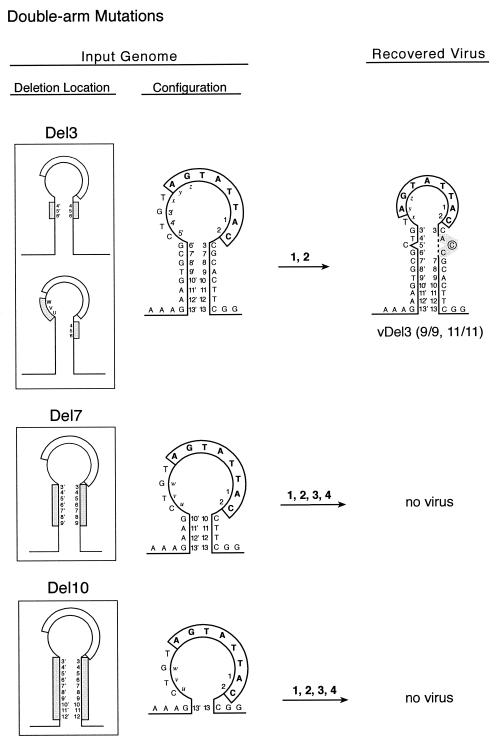

FIG. 5.

Input genomes and recovered viruses from double-arm mutations. See the legend to Fig. 3 for details.

Left-arm deletions. (i) LD3.

A copy of the tandem triplet (CTG/CTG) at positions 5′, 4′, and 3′/u, v, and w was deleted in LD3, and the recovered progeny viruses contained only one copy of the triplet (Fig. 3). Since the remaining triplet can occupy the left-arm positions 5′, 4′, and 3′, the recovered viruses may exhibit the original 11-nucleotide palindrome but a shortened loop (9 instead of 12 nucleotides). The results from two independent experiments showed that the engineered mutation was retained in the progeny viruses.

(ii) SL6.

Both copies of the tandem triplet (CTG/CTG) at positions 5′, 4′, and 3′/u, v, and w were deleted in SL6, and the recovered progeny viruses obtained in two separate experiments did not contain these six nucleotides. Thus, these viruses have a noncomplementary upper region (positions 3, 4, and 5) and may exhibit a shortened palindromic stem of eight nucleotides.

(iii) LD7.

Seven nucleotides (TGCGCTG) at positions 9′ through 3′ were deleted. Four independent experiments were conducted, and each yielded a set of progeny viruses with slightly different palindromic sequences. Inspection of the progeny virus genomes suggested that the input viral DNAs may have assumed multiple configurations based on nucleotide base-pairing availability. It is unlikely that any stable palindrome could have been formed by the base-pairing nucleotide that remained in the engineered genomes (between one and four nucleotide) at the onset of DNA replication. As illustrated, virus genome A was likely derived from configuration A (with four base-pairing nucleotides), while virus genome B was likely derived from configuration B (with three base-pairing nucleotides). Essentially, the right-arm sequences of the recovered viruses were identical to that of the input genomes, which indicates that the minus genome was used as the template during initiation of DNA replication. During termination, a portion of the right arm served as the template for synthesis of the left arm (shaded nucleotides) to generate a longer palindrome. A total of six genotypes were observed among the progeny viruses, and each contained a longer and more stable palindrome than that of the input DNA. Evidently, template strand switching from the minus genome template to the newly synthesized palindromic strand aN template occurred during termination of DNA replication. In addition, nucleotide insertion or deletion was observed in each progeny virus.

For vLD7.1, leading-strand DNA synthesis proceeded through positions u, v, w, x, y, and z before template strand switching to use the right arm as the template. Upon reverse template strand switching (from palindromic strand aN to genome strand b′) to synthesize the loop sequence, the triplet sequence TAG at positions x, y, and z was duplicated. For vLD7.2, leading-strand DNA synthesis proceeded through positions l, m, and n and then the nucleotides at positions o, p, q, r, s, 13′, 12′, 11′, 10′, u, v, and w were deleted. Template strand switching occurred at the bottom of the left arm, and the leading strand used the right arm as the template for synthesizing almost the entire new left arm. For vLD7.3, leading-strand DNA synthesis proceeded through positions u, v, and w, and then template strand switching used the right arm as the template before reverse template strand switching to use the minus genome at positions x, y, and z. With vLD7.4, vLD7.5, and vLD7.6, leading-strand DNA synthesis proceeded through positions l, m, n, o, p, q, and r before template strand switching occurred. For vLD7.4 and vLD7.6, the nucleotides at positions s, 13′, 12′, 11′, 10′, u, v, and w were deleted. For vLD7.5, a shorter sequence (s, 13′, 12′, 11′, 10′) was deleted, and reverse template strand switching occurred at positions u, v, and w. Thus, for each virus, a different length of the right arm was used as the template to regenerate the left-arm sequence prior to reverse template strand switching to synthesize the loop nucleotide.

(iv) LD11.

The entire left-arm sequence from nucleotides 13′ to 3′ was deleted in LD11. Judging from the four recovered viruses, the input genomes would have existed in two configurations (A and B) during replication. Configuration A appeared to have recruited the l, m, n, o, and p sequence into the melting pot to generate vLD11.1, vLD11.2, and vLD11.4. Both vLD11.1 and vLD11.2 had a deletion of six nucleotides at positions q, r, s, u, v, and w, and vLD11.2 incorporated an illegitimate nucleotide at position o (circled). For vLD11.1 and vLD11.2, template strand switching occurred after positions l, m, n, o, and p and then reverse template strand switching occurred at positions x, y, and z. For vLD11.4, only two nucleotides at positions 6 to 7 of the right leg were used as the templates, and the three nucleotides at positions q, r, and s were deleted. Since the nucleotides at positions l, m, n, o, and p were not recruited into a new palindrome, configuration B was void of any base-pairing nucleotide. However, it gave rise to vLD11.3, which exhibited the original 11-nucleotide palindrome by regenerating the sequence at positions 13′ through 6′ with the right arm as the template and then reverse template strand switching at positions u, v, and w. Nucleotide deletion was not observed with vLD11.3, but an illegitimate C nucleotide was incorporated into the right arm at position 5. This collection of progeny viruses showed that a different length of the right arm was also used as the template to regenerate the left-arm sequence.

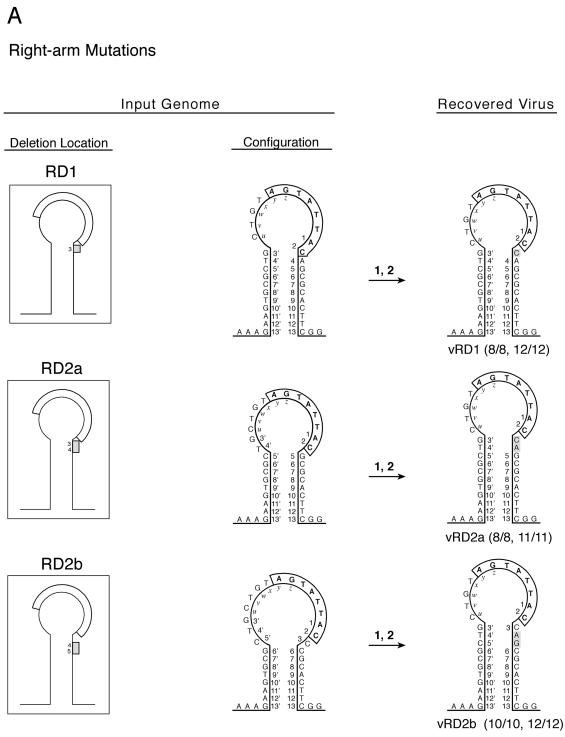

Right-arm deletions.

Previous work (4) showed that the C nucleotides at positions 3 and 10 (designated C3 and C10) are critical for PCV1 progeny virus regeneration. The following experiments were aimed at deleting C3 or disrupting the spatial distance between C3 and C10.

(i) RD1, RD2a, and RD2b.

One or two nucleotides were deleted from this group of mutant genomes. As shown above, the number of Rep-associated antigen-producing cells exhibited by RD1 (25%), RD2a (<1%), and RD2b (<10%) was reduced, and fewer progeny viruses were recovered immediately after transfection in comparison with the parent genome J1. However, all three input deletion genomes yielded wild-type viruses, and they could all be accounted for by template strand switching during initiation of DNA replication (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Input genomes and recovered viruses from right-arm mutations. See the legend to Fig. 3 for details.

(ii) RD3.

Three nucleotides were deleted from the right arm at positions 3, 4, and 5 (CAG) or 4, 5, and 6 (AGC) in RD3, and five variant viruses were recovered. Presumably, this mutant genome would assume the 4-5-6 deletion configuration because C3 plays an important role in viral protein synthesis. For vRD3.1, template strand switching occurred after position 3 at the onset of initiation of DNA replication, and the sequence at 4′, 5′, and 6′ was used as the template to regenerate the wild-type palindrome. For vRD3.2, 2 illegitimate nucleotides (TA) were inserted prior to template strand switching to use position 6′ as the template. This virus may exhibit an expanded loop and a shortened palindrome. For vRD3.3 and vRD3.4, template strand switching occurred after position 3, and an illegitimate C nucleotide was incorporated in the regenerated sequence of each virus; in addition, vRD3.4 had a second illegitimate T nucleotide at position 8. For vRD3.5, template strand switching occurred after position 8 and an illegitimate C nucleotide was incorporated in the regenerated sequence; the actual C3 and C10 of the new genome are denoted by asterisks. Alternatively, the regenerated sequences in vRD3.3, vRD3.4, and vRD3.5 could also be the product of duplication of the preceding sequence (ACC for vRD3.3 and vRD3.4 and ACCGC for vRD3.5) (indicated by dotted lines) resulted from slippage of the replication machineries (10).

(iii) RD7 and RD10.

Seven nucleotides from positions 3 through 9 and 10 nucleotides from positions 3 through 12 were deleted from RD7 and RD10, respectively. Progeny viruses were not recovered from RD7, but on one occasion, viruses were recovered from RD10. Apparently, the sequence at positions 24 to 30 downstream from the original right arm was recruited into the stem portion of the melting pot but only the nucleotides at positions 29 and 30 were retained in the vRD10 viruses. Template strand switching was evident at position 13 to regenerate a wild-type sequence for the right arm, and concurrently, two separate deletion events appeared to have occurred at positions 14 to 28 and 36 to 41. The data also showed that only one copy of the hexanucleotide CGGCAG was sufficient to sustain replication of the modified genome of vRD10.

Double-arm deletions. (i) Del3.

Three nucleotide at positions 4, 5, and 6 of the right arm and a copy of the complementary sequence at positions 4′, 5′, and 6′ or u, v, and w of the left arm were deleted (Fig. 5). A variant virus with three nucleotides inserted into the right arm (positions 4, 5, and 6) but not the left arm was recovered. This new DNA sequence could be accounted for by template strand switching at position 3 with incorporation of an illegitimate C in the regenerated sequence. Alternatively, the regenerated sequence (ACC) could also be the result of duplication of the preceding sequence due to slippage of the replication machineries.

(ii) Del7 and Del10.

Seven and 10 nucleotides on both sides of the palindrome were deleted from Del7 and Del10, respectively. Progeny viruses were not recovered from either input genome in four independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, deletion mutagenesis was conducted to investigate the importance of the origin-flanking palindromic sequences of the PCV1 genome with respect to viral protein synthesis and progeny virus production via self-DNA replication. A total of 13 mutant genomes were constructed. Three of the engineered genomes did not give any progeny virus, while the other 10 yielded 22 progeny virus variants. Deletions (from 3 to 11 nucleotides) introduced into the left arm (LD3, SL6, LD7, and LD11) did not affect the number of viral antigen-producing cells, and progeny viruses were readily recovered from cultures transfected with the excised and recircularized double-stranded mutant genomes. In contrast, the right-arm and double-arm deletion genomes exhibited greatly reduced numbers of Rep-associated protein-producing cells. Since the Rep-associated antigens are essential for PCV DNA replication, their reduction is expected to affect progeny virus production. Mutant genomes with deletions of three or fewer nucleotides (RD1, RD2a, RD2b, RD3, and Del3) yielded progeny viruses consistently, while a seven-nucleotide-deletion genome (RD7) did not give any progeny virus, and a 10-nucleotide-deletion genome (RD10) yielded infectious viruses only occasionally. In comparison with a previous study (4), nucleotide substitutions engineered into the right arm, left arm, or both arms of the palindrome did not affect protein synthesis or progeny virus production. Therefore, the types of mutations and their specific locations at the origin have different effects on PCV protein synthesis, self-DNA replication, and progeny virus regeneration.

Previous studies on bacterial plasmids (24, 31), geminiviruses (16, 33, 37), and parvoviruses (17) concluded that a palindrome at the origin of each system is essential for initiation of DNA replication. In contrast, the results from this study corroborated previous work (4) and demonstrated that a palindrome is nonessential for initiation of PCV1 DNA replication. The deletions introduced into LD7 and LD11 rendered each with minimal base-pairing nucleotides remaining (LD7 with one to four nucleotides and LD11 with zero to five nucleotides), but these mutant genomes yielded viable progeny viruses. It is doubtful that any base pairing could have occurred to form a cruciform structure when the input viral genomes were introduced into PK15 cells or at the onset of DNA replication. In addition, if a stable cruciform structure had been formed during initiation of DNA replication, none of the recovered viruses of LD7 or LD11 would have maintained their right-arm sequences. Thus, the rolling-circle cruciform replication model cannot be employed to account for the progeny viruses here.

Evidence of template strand switching at the PCV1 origin, in which both the minus genome and a corresponding palindromic sequence must have served as the templates, was provided by nucleotide sequence analysis of the progeny viruses. In fact, template strand switching may have contributed to the generation of the palindromes present in all of the progeny viruses except vLD3 and vSL6. In this study, the deleted left arm was readily regenerated via template strand switching with the right arm as the template during termination of DNA replication. However, correction of the right arm with the left arm as the template was less efficient because the engineered right-arm deletions adversely affected synthesis of the essential Rep-associated proteins. Although some of the progeny viruses recovered from the right-arm deletion genomes could be accounted for by sequence duplication caused by slippage of the replication machineries (vRD3.3, vRD3.4, vRD3.5, and vDel3) (10), template strand switching during initiation of DNA replication was evident in vRD1, vRD2a, vRD2b, vRD3.1, vRD3.2, and vRD10. These results prominently display the inverted repeat correction mechanism inherent in the rolling-circle melting-pot replication model (4). The LD7 and LD11 progeny viruses provided the best examples to support this model by exhibiting template strand switching in the middle of synthesizing the left arm and unequivocally demonstrated that both the minus genome and the newly synthesized strand aN were available simultaneously to serve as templates during termination of DNA replication.

Although the melting-pot model allows the leading strand the freedom to choose either the minus genome or a corresponding palindromic sequence as the template, only viruses with longer and more stable palindromes than the input genomes had were recovered in this and previous substitution mutagenesis studies. Thus, the regeneration of a palindrome at the origin of PCV1 at the end of the replication process is preferred. This palindrome may be the signal for termination of PCV DNA replication. Interestingly, the importance of an origin-flanking palindrome during termination of DNA replication has also been suggested for wheat dwarf virus of the Geminiviridae family (14).

Similar to previous work (4, 5), the 12-nucleotide loop and the 11-nucleotide palindrome of a perturbed melting pot exhibited a high degree of flexibility and mutability. The loop sequences of PCV1 (12 nucleotides) and PCV2 (10 nucleotides) are interchangeable (5). Deletion of one or both copies of the triplet CTG at positions 3′, 4′, and 5′ or u, v, and w at the left-arm stem-loop junction was tolerated (e.g., vLD3, vSL6, and vDel3). The palindrome (positions 3 through 13) can be lengthened or shortened as the circumstances dictate (e.g., vSL6, vLD7, vLD11, and vRD3.5). In combination with one or more deletion events, the upstream sequence at positions l, m, n, o, and p or the downstream sequence at positions 24 to 30 can be recruited into the melting pot to generate vLD11.1, vLD11.2, vLD11.4, and vRD10, respectively. Ample examples of illegitimate recombination errors (i.e., deletions, insertions, and illegitimate nucleotide incorporation) that occur frequently at the origin of phages and plasmids (25, 26) were also detected here. Insertions or duplications (e.g., vLD7.1, vRD3.2, and vRD3.5) and deletions (e.g., selected vLD7, selected vLD11, and vRD10) were observed among the progeny viruses. Incorporation of illegitimate nucleotide was detected in vLD11.2, vLD11.3, vRD3.2, vRD3.3, vRD3.4, vRD3.5, and vDel3. However, the “illegitimate” nucleotides in vRD3.3, vRD3.4, vRD3.5, and vDel3 could be attributed to duplication of the preceding sequence and not to illegitimate nucleotide incorporation. Finally, it is interesting that when multiple experiments were conducted with some of the mutant genomes (four with LD7, three with LD11, four with RD3, and five with RD10), multiple sets of progeny viruses were obtained. These observations suggest that the destabilized environment at the PCV1 origin, with all four strands of the inverted repeats in the melted state, and the availability of two templates simultaneously during initiation and termination of DNA replication may contribute to the flexibility as well as the increased mutation frequency at the origin.

Integrated in this destabilized and very flexible melting-pot environment is a certain degree of organization. Formation of the melting pot is dependent upon the interactions between the REP complex and its cognate octanucleotide motif sequence (5, 20). Mutant nucleotides engineered into positions 3 and 10 of the right arm reverted back to wild-type C nucleotides in the progeny virus genomes irrespective of the minus genome template or the corresponding palindromic strand template (4). These two positions have been designated birthright positions, and presumably their birthrights are “inherited” and dictated by the REP complex. All the progeny viruses recovered from the right-arm deletion genomes contained a C nucleotide at positions 3 and 10 through insertion or deletion of the appropriate number of nucleotides via template strand switching or duplication. The most notable examples are vRD3.5 and vRD10, in which the genomes underwent multiple modifications (a combination of insertion, duplication, deletion, and illegitimate nucleotide incorporation) to maintain the C3 and C10 configuration. These data indicate that the predetermined status of positions 3 and 10 and the spatial distance between C3 and C10 are critical for PCV1 DNA replication. Furthermore, DNA sequence complementarity is not the only deciding factor for nucleotide incorporation during self-DNA replication at the PCV1 origin.

Not unexpectedly, the results obtained in this investigation arrived at the melting-pot model independently of the substitution mutagenesis study (4). Thus, this work confirms and extends previous observations that the rolling-circle melting-pot replication model provides a viable mechanism for DNA replication, inverted repeat correction (or conversion), and illegitimate recombination at the PCV1 origin and may be applicable to the replication of other circular DNAs.

Acknowledgments

I thank S. Pohl, D. Alt, K. Halloum, and O. Kohutyuk for technical assistance and M. Marti and S. Ohlendorf for manuscript preparation.

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan, G. M., and J. A. Ellis. 2000. Porcine circoviruses: a review. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 12:3-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung, A. K. 2003. Comparative analysis of the transcriptional patterns of pathogenic and non-pathogenic circoviruses. Virology 301:41-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung, A. K. 2004. Identification of the essential and non-essential transcriptional units for protein synthesis, DNA replication and infectious virus production of porcine circovirus type 1. Arch. Virol. 149:975-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung, A. K. 2004. Detection of template strand-switching during initiation and termination of DNA replication of porcine circovirus. J. Virol. 78:4268-4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung, A. K. Identification of an octanucleotide motif sequence essential for viral protein, DNA and progeny virus biosynthesis at the origin of DNA replication of porcine circovirus type 2. Virology, 324:28-36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Cheung, A. K., and S. R. Bolin. 2002. Kinetics of porcine circovirus type 2 replication. Arch. Virol. 147:43-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.del Solar, G., R. M. Giraldo, J. Ruiz-Echevarria, M. Espinosa, and R. Diaz-Orejas. 1998. Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:434-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenaux, M., P. G. Halbur, M. Gill, T. E. Toth, and X. J. Meng. 2000. Genetic characterization of type 2 porcine circovirus (PCV-2) from pigs with postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in different geographic regions of North America and development of a differential PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay to detect and differentiate between infections with PCV-1 and PCV-2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2494-2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbs, M. J., and G. F. Weiller. 1999. Evidence that a plant virus switched hosts to infect a vertebrate and then recombined with a vertebrate-infecting virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8022-8027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham, F. L., J. Rudy, and P. Brinkley. 1989. Infectious circular DNA of human adenovirus type 5: regeneration of viral DNA termini from molecules lacking terminal sequences. EMBO J. 7:2077-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez, C. 1999. Geminivirus DNA replication. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56:313-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamel, A. L., L. L. Lin, and G. P. S. Nayar. 1998. Nucleotide sequence of porcine circovirus associated with postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in pigs. J. Virol. 72:5262-5267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanley-Bowdoin, L., S. B. Settlage, B. M. Orozco, S. Nagar, and D. Robertson. 2000. Geminiviruses: models for plant DNA replication, transcription, and cell cycle regulation Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35:105-140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kammann, M., H. J. Schalk, V. Matzeit, S. Schaefer, J. Schell, and B. Gronenborn. 1991. DNA replication of wheat dwarf virus, a geminivirus, requires two cis-acting signals. Virology 184:786-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan, S. A. 2000. Plasmid rolling-circle replication: recent developments. Mol. Microbiol. 37:477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazarowitz, S. G., A. J. Pinder, V. D. Damsteegt, and J. S. Rogers. 1989. Maize streak virus genes essential for systemic and symptom development. EMBO J. 8:1023-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefebvre, R. B., S. Riva, and K. I. Berns. 1984. Conformation takes precedence over sequence in adeno-associated virus DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:1416-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mankertz, A., and B. Hillenbrand. 2001. Replication of porcine circovirus type 1 requires two proteins encoded by the viral rep gene. Virology 279:429-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mankertz, A., J. Mankertz, K. Wolf, and H.-J. Buhk. 1998. Identification of a protein essential for replication of porcine circovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 79:381-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mankertz, A., F. Persson, J. Mankertz, G. Blaess, and H.-J. Buhk. 1997. Mapping and characterization of the origin of DNA replication of porcine circovirus. J. Virol. 71:2562-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNulty, M., J. Dale, P. Lukert, A. Mankertz, J. Randles, and D. Todd. 2000. Circoviridae, p. 299-303. In M. H. V. van Regenmortel, C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wickner (ed.), Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 22.Meehan, B. M., J. L. Creelan, M. S. McNulty, and D. Todd. 1997. Sequence of porcine circovirus DNA: affinities with plant circoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 78:221-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meehan, B. M., F. McNeilly, D. Todd, S. Kennedy, A. Jewhurst, J. A. Ellis, L. E. Hassard, E. G. Clark, D. M. Haines, and G. M. Allan. 1998. Characterization of novel circovirus DNAs associated with wasting syndromes in pigs. J. Gen. Virol. 79:2171-2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miao, D. M., Y. Honda, K. Tanaka, A. Higashi, T. Nakamura, Y. Taguchi, H. Sakai, T. Komano, and M. Bagdasarian. 1993. A base-paired hairpin structure essential for the functional priming signal for DNA replication of the broad host range plasmid RSF1010. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:4900-4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michel, B., and S. D. Ehrlich. 1986. Illegitimate recombination at the replication origin of bacteriophage M13. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:3386-3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel, B., and S. D. Ehrlich. 1986. Illegitimate recombination occurs between the replication origin of the plasmid pC194 and a progressing replication fork. EMBO J. 5:3691-3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morozov, I., T. Sirinarumitr, S. Sorden, P. G. Halbur, M. K. Morgan, K.-J. Yoon, and P. S. Paul. 1998. Detection of a novel strain of porcine circovirus in pigs with postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2535-2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musatov, S., J. Roberts, D. Pfaff, and M. Kaplitt. 2002. A cis-acting element that directs circular adeno-associated virus replication and packaging. J. Virol. 76:12792-12802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musatov, S. A., T. A. Scully, L. Dudus, and K. J. Fisher. 2000. Induction of circular episomes during rescue and replication of adeno-associated virus in experimental models of virus latency. Virology 275:411-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niagro, F. D., A. N. Forsthoefel, R. P. Lawther, L. Kamalanathan, B. W. Ritchie, K. S. Latimer, and P. D. Lukert. 1998. Beak and feather disease virus and porcine circovirus genomes: intermediates between geminiviruses and plant circoviruses. Arch. Virol. 143:1723-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noirot, P., J. Bargonetti, and R. P. Novick. 1990. Initiation of rolling-circle replication in pT181 plasmid: initiator protein enhances cruciform extrusion at the origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:8560-8564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novick, R. P. 1998. Contrasting lifestyles of rolling-circle phages and plasmids. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:434-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orozco, B. M., and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1996. A DNA structure is required for geminivirus replication origin function. J. Virol. 70:148-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer, K. E., and E. O. Rybicki. 1998. The molecular biology of mastreviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 50:183-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pringle, C. R. 1999. Virus taxonomy at the XIth International Congress of Virology, Sydney, Australia. Arch. Virol. 144:2065-2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randles, J. W., P. W. G. Chu, J. L. Dale, R. M. Harding, J. Hu, M. Kojima, K. M. Makkouk, Y. Sana, J. E. Thomas, and H. J. Vetten. 2000. Nanovirus, p. 303-309. In M. H. V. van Regenmortel, C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wickner (ed.), Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 37.Revington, G. N., G. Sunter, and D. M. Bisaro. 1989. DNA sequences essential for replication of the B genome component of tomato golden mosaic virus. Plant Cell 1:985-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samulski, R. J., A. Srivastava, K. I. Berns, and N. Muzyczka. 1983. Rescue of adeno-associated virus from recombinant plasmids: gene correction within the terminal repeats of AAV. Cell 33:135-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinfeldt, T., T. Finsterbusch, and A. Mankertz. 2001. Rep and Rep′ protein of porcine circovirus type 1 bind to the origin of replication in vitro. Virology 291:152-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tischer, I., H. Gelderblom, W. Vettermann, and M. A. Koch. 1982. A very small porcine virus with circular single-stranded DNA. Nature 295:64-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]