Abstract

Patients with hypophosphatemia rickets (including DMP1 mutations) develop severe osteoarthritis (OA), although the mechanism is largely unknown. In this study, we first identified the expression of DMP1 in hypertrophic chondrocytes using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and X-gal analysis of Dmp1-knockout-lacZ-knockin heterozygous mice. Next, we characterized the OA-like phenotype in Dmp1 null mice from 7-week-old to one-year-old using multiple techniques, including X-ray, micro-CT, H&E staining, Goldner staining, scanning electronic microscopy, IHC assays, etc. We found a classical OA-like phenotype in Dmp1 null mice such as articular cartilage degradation, osteophyte formation, and subchondral osteosclerosis. These Dmp1 null mice also developed unique pathological changes, including a biphasic change in their articular cartilage from the initial expansion of hypertrophic chondrocytes at the age of 1-month to a quick diminished articular cartilage layer at the age of 3-months. Further, these null mice displayed severe enlarged knees and poorly formed bone with an expanded osteoid area. To address whether DMP1 plays a direct role in the articular cartilage, we deleted Dmp1 specifically in hypertrophic chondrocytes by crossing the Dmp1-loxP mice with Col X Cre mice. Interestingly, these conditional knockout mice didn't display notable defects in either the articular cartilage or the growth plate. Because of the hypophosphatemia remained in the entire life span of the Dmp1 null mice, we also investigated whether a high phosphate diet would improve the OA-like phenotype. A 8-week treatment of a high phosphate diet significantly rescued the OA-like defect in Dmp1 null mice, supporting the critical role of phosphate homeostasis in maintaining the healthy joint morphology and function. Taken together, this study demonstrates a unique OA-like phenotype in Dmp1 null mice, but a lack of the direct impact of DMP1 on chondrogenesis. Instead, the regulation of phosphate homeostasis by DMP1 via the axis of “FGF23-renal phosphorus reabsorption” is vital for maintaining a healthy joint.

Keywords: Dentin Matrix Protein 1, Osteoarthritis, Cartilage, Chondrocyte, Subchondral Bone.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA), also known as degenerative arthritis or degenerative joint disease, is usually considered as a group of abnormalities involving the progressive reduction of proteoglycan and collagen in articular cartilage, subchondral bone sclerosis and osteophyte formation, etc. OA affects more than 27 million people in the U.S 1, 2. However, the pathogenesis of OA is poorly understood. A number of studies have indicated that there is a strong hereditary component in primary OA 3-5, but the exact genes those involved in this process have not been clearly identified.

Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1), a member of the small integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoprotein (SIBLINGs) family 6, 7, is an acidic non-collagenous phosphoprotein that is found mainly expressed in the extracellular matrix of dentin and bone 8-11. Several studies revealed that DMP1 plays important roles in both osteogenesis and dentinogenesis 12-16. Genetic studies showed that Dmp1 deletion in mice and its mutations in humans lead to autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets (ARHR) 13, 17. Pathological studies demonstrated that DMP1 regulates in vivo phosphate homeostasis via fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a hormone released from bone and targeted in the kidney to accelerate renal excretion of phosphate that results in lower serum phosphorus levels 13, 17, 18.

A clinical study reported that two ARHR patients, who did not receive high phosphate (Hi-Pi) diet treatment, developed OA-like symptoms, including joint pain, loss of articular cartilage, fusion of joints and bony outgrowths or osteophytes 19. This study suggests that DMP1 is one of the genetic factors involved in the primary OA development, although it is not clear whether OA-like phenotype is a direct or indirect consequence of DMP1 mutations.

Our early studies showed that the postnatal development of the growth plate in Dmp1 knockout (KO) mice was severely impaired, resulting in a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype 20. Further evaluations consistently demonstrated that this chondrodysplasia-like phenotype could be fully rescued by a Hi-Pi diet alone or FGF23 antibody injection, suggesting that Dmp1 deletion indirectly causes OA development via its role in regulating bone metabolism through the functional axis of “FGF23-renal phosphorus reabsorption-serum phosphorus level” 13, 18, 20. However, several recent studies implied that DMP1 may play a direct role in the regulation of chondrogenesis, cartilage remodeling and the pathological changes of OA. For example, DMP1 was detected in the cartilage of developing forelimb, postnatal growth plate and articular cartilage 21, 22. Furthermore, Prasadam and colleagues documented a direct correlation between DMP1 expression level and chondrogenesis, OA development, respectively 23.

In this study, we attempted to address: 1) The pathological changes of the global Dmp1 KO knees at the levels of gross, cell and molecule during postnatal development stages from 1-month to 12-months (detailed evaluations focused mainly on 7-weeks and 3-month), as well as the potential mechanism; 2) whether the conditional KO (cKO) of Dmp1 in hypertrophic chondrocytes develops the OA-like phenotype; and 3) whether a Hi-Pi diet rescues the OA-like phenotype in Dmp1 KO mice. Our studies confirmed DMP1 expression in the articular cartilage and subchondral bone, although the conditional deletion of Dmp1 in chondrocytes by crossing Dmp1-loxP to Col X Cre mice did not recapture the OA-like phenotype. However, the Dmp1 KO mice developed an early onset of the OA-like phenotype from puberty, and became severe at the age of 12-months. Interestingly, there was a biphasic response in the KO articular cartilage layer: a dramatic expansion in hypertrophic chondrocyte layer at early stage but a quick reduction in the articular cartilage subsequently. Finally, we demonstrated a complete recovery of the OA-like phenotype in Dmp1 null mice by the Hi-Pi diet alone.

Materials and Methods

Animals and phosphate diet

The details of the generation of Dmp1 KO mice in C57B/L6 genetic background using the lacZ-knockin target approach have been described previously 9, 14, 20. The generation of the conditional allele of Dmp1 mice was also reported earlier 24, and it was crossed to Col X Cre for the specific deletion of Dmp1 in cartilage. Age-matched wild type (WT) mice were used as controls and fed with autoclaved rodent chow (5010; Ralston Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 1% calcium, 0.67% phosphorus and 4.4 international units (IU) vitamin D/g (regular diet). While the Hi-Pi diet group (KO+Hi-Pi) were fed with the rodent chow which containing 1.5% phosphorus, 0.6% calcium, 0.6% sodium and 1% potassium (03625 Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) from the age of 3-weeks onwards. Genomic DNA was extracted from a tail biopsy and used for genotyping by PCR analysis as described previously 25. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Texas A&M University, Baylor College of Dentistry (Dallas, TX, USA).

Histological analysis

Under anesthesia, the aforementioned mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution (pH 7.4). The whole knee joints were dissected, and fixed in the same solution for 48 hours at 4°C. All samples were then decalcified using 10% EDTA medium and embedded in paraffin using standard histologic protocols 8, or dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol (from 70% to 100%) then embedded in methyl methacrylate (MMA, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL) as undecalcified specimens. The paraffin blocks were cut into serial sections of 4.5 μm thickness and the plastic blocks were cut into 6 μm thickness using a Leica 2165 rotary microtome (Ernst Leitz Wetzlar) for further histological analysis, including H&E staining, safranin-O fast green staining, toluidine blue staining, Goldner's masson trichrome staining, as described previously 15.

Immunohistochemistry

The antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are listed as following: For detection of DMP1, anti-DMP1-C-terminal polyclonal antibody 26 was used at a dilution of 1:500; for detection of type II collagen (Col II), anti-type II collagen polyclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) was used at a dilution of 1:1000; for detection of type IV collagen (Col IV), anti-type IV collagen polyclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) was used at a dilution of 1:400; for detection of type X collagen (Col X), anti-type X collagen monoclonal antibody (Quartett Immunodiagnostika & Biotechnologie GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used at a dilution of 1:100; for detection of MMP13, anti-MMP13 monoclonal antibody (kindly provided by Dr. E. Lee, Shriners Hospital for Children) was used at a dilution of 1:200; for detection of sclerostin (SOST), anti-SOST polyclonal antibody (R&D Biosystems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used at a dilution of 1:200; for detection of bone sialoprotein (BSP), anti-BSP monoclonal antibody (anti-BSP-10D9.2) 27 was used at a dilution of 1:1000; for detection of osteopontin (OPN), anti-OPN monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) was used at a dilution of 1:200. All IHC experiments were carried out using the M.O.M kit and DAB kit (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

β-Galactosidase (lacZ) expression assay

The method of β-Galactosidase staining was described previously 14. Femoral heads were dissected from 3-week-old Dmp1 heterozygous mice and fixed for 5 min immediately, then were rinsed with PBS for 15 min. After PBS wash, the specimens were stained for 48 hours in freshly prepared X-gal solution (1 mg/ml) at 37°C. The stained samples were washed with PBS again, followed by re-fixation, decalcification, and embedded in paraffin for sectioning, then counterstained by nuclear fast red (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Radiography, micro-computed tomography (µCT) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The knee joints were examined on a Faxitron MX-20 radiography system (Faxitron X-ray Corp., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Three-dimensional images of the knee joints from WT, Dmp1 KO and KO+Hi-Pi mice were scanned with μ-CT (μ-CT35, Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). Images were reconstructed using EVS Beam software with a global threshold at 1400 Hounsfield Units. MMA embedded samples were cut and polished on the surface using 1.0 μm and 0.3 μm alumina alpha micropolish II solution (Buehler, IL, USA), then scanned by a FEI/Philips XL30 field-emission environmental SEM (Hillsboro, OR, USA) as described previously 20, 28.

Serum biochemistry

Three-month-old mice were anesthetized, blood was collected through heart puncture, and serums were obtained by precipitation and centrifugation. Serum phosphorous (Pi), calcium (Ca) and FGF23 was measured following the protocol as previously described 13.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA for multiple-group comparison. If significant differences were found with one-way ANOVA, the Bonferroni method was used to determine which groups were significantly different from others. The quantified results are represented as the “MEAN±SEM”; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

Identification of DMP1 expression in articular cartilage and subchondral bone

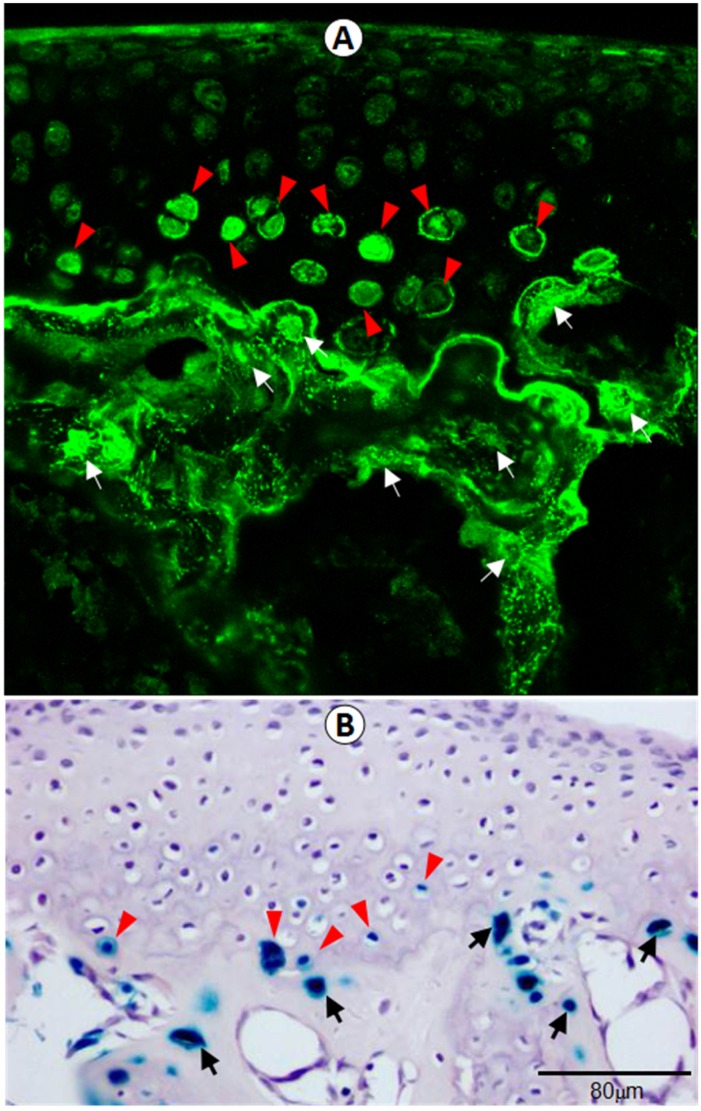

To verify the physiological relevance of DMP1 in femoral head, including articular cartilage and the subchondral bone, we examined its in vivo expression pattern using both confocal immunofluorescence imaging (Figure 1A) and lacZ expression assay (Figure 1B) in Dmp1 heterozygous mice. Both assays showed clearly that DMP1 is expressed in both the articular cartilage and subchondral bone. Specifically, DMP1 was mainly detected in the hypertrophic chondrocytes and osteocytes.

Figure 1.

DMP1 is expressed in hypertrophic chondrocytes in 3-week-old articular cartilage by immunofluorescence stain and x-gal stain. (A) DMP1 was detected at high levels in the osteocytes (white arrows) and some of the hypertrophic chondrocytes (arrowheads) by immunofluorescence analysis. (B) X-gal staining of Dmp1 heterozygous bone cells (arrows) and hypertrophic chondrocytes (arrowheads), in which one allele of Dmp1 is replaced by a lacZ reporter gene and expression of lacZ reflects endogenous Dmp1 activity.

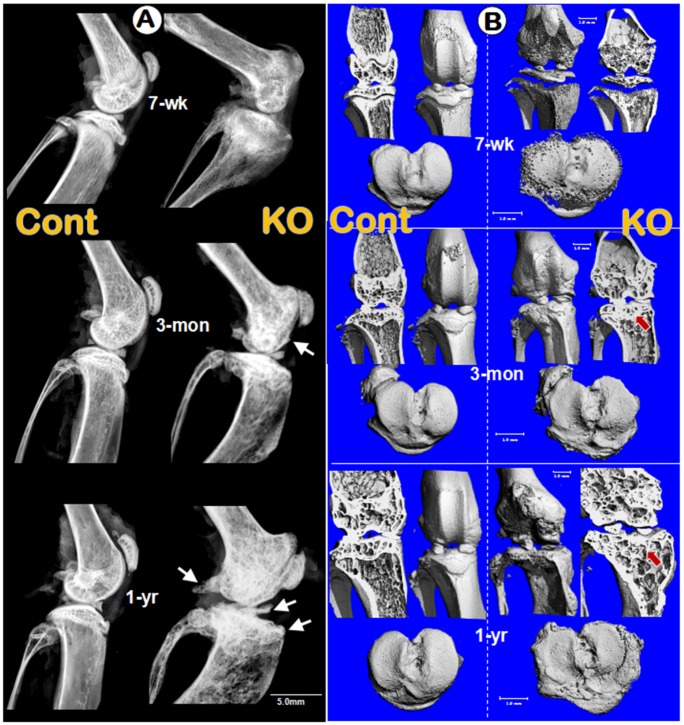

Dmp1 null mice developed early OA-like phenotype that progresses with aging

To test the overall impact of Dmp1 ablation on knee joints, we examined the integrity of knee joints in pubertal (7-week-old), adult (3-month-old), and old (1-year-old) mice by radiographs. The lateral X-ray images showed that the joint shape, comparing to the control littermates, is notably expanded in the Dmp1 KO mice throughout their developmental stages starting from 7-weeek-old (Figure 2A, upper right). The initial osteophyte was observed at the age of 3-months (Figure 2A, middle right, arrow) and showed more striking changes at the age of 1-year (Figure 2A, lower right, arrows). The μ-CT images further confirmed thick osteosclerosis and malformed subarticular spongiosa in the 3- and 12-month-old KO articulations by the longitudinal cross-section views (Figure 2B, upper right panels). Besides, the tibial plateaus showed porous and uneven bone surfaces in the KO tibia at all age groups with osteophyte-like structures growing out in elder ones (Figure 2B, lower right panels).

Figure 2.

Morphological and histological OA-like changes in Dmp1 null mice. (A) Representative radiographs showed the knee joints of Dmp1 KO mice (right panels) and the age-matched littermate controls (left panels) at the early stage (7-week-old, top), adult stage (3-month-old, middle), and the old stage (1-year-old, lower). The arrows reflect osteophytes. (B) the μ-CT images from frontal view of the knee joints (center), the matched longitudinal sections (both sides), and tibial plateaus (bottom) at age of 7-weeks (top), 3-months (middle), and 1-year (lower) with arrows pointed to the area changed; and (C) Representative H&E staining of control (left panels) and Dmp1 KO (right panels) mice from 7-week-old, 3-month-old, and 12-month-old. Arrows indicate osteophytes, ellips circle the areas with complete loss of cartilage, asterisks point the subchondral bone sclerosis, and the inserted images displayed the enlarged box area.

To further understanding the progress of the morphological changes in the Dmp1 KO knee, we performed H&E stains. The histological images displayed no apparent changes in the articular cartilage at the age of 7-weeks (Figure 2C, upper right). By 3-month-old, a small osteophyte-like structure was detected (Figure 2C, middle right). At the age of 1-year, there were large osteophyte-like structures appeared in the KO knee joint (Figure 2C, lower right). Besides, in the remained KO articular cartilage, degradation or denudation surface can be clearly observed (Figure 2C, insert), and in several areas, there were complete abrasions of articular cartilage layer (Figure 2C, circle rings).

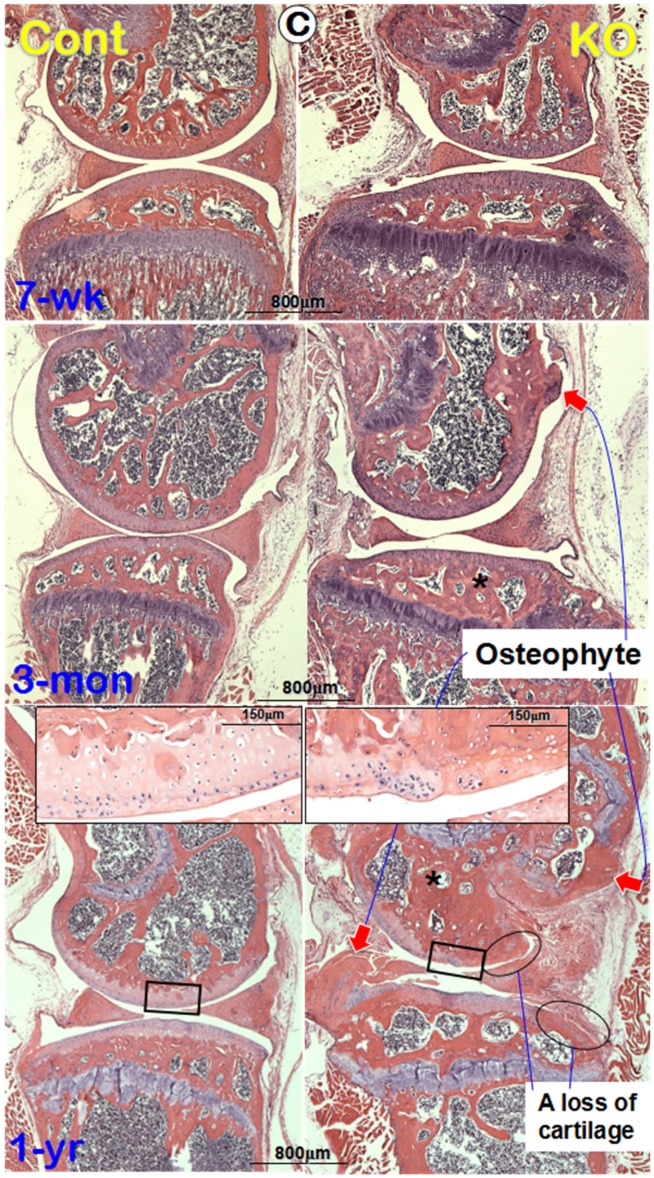

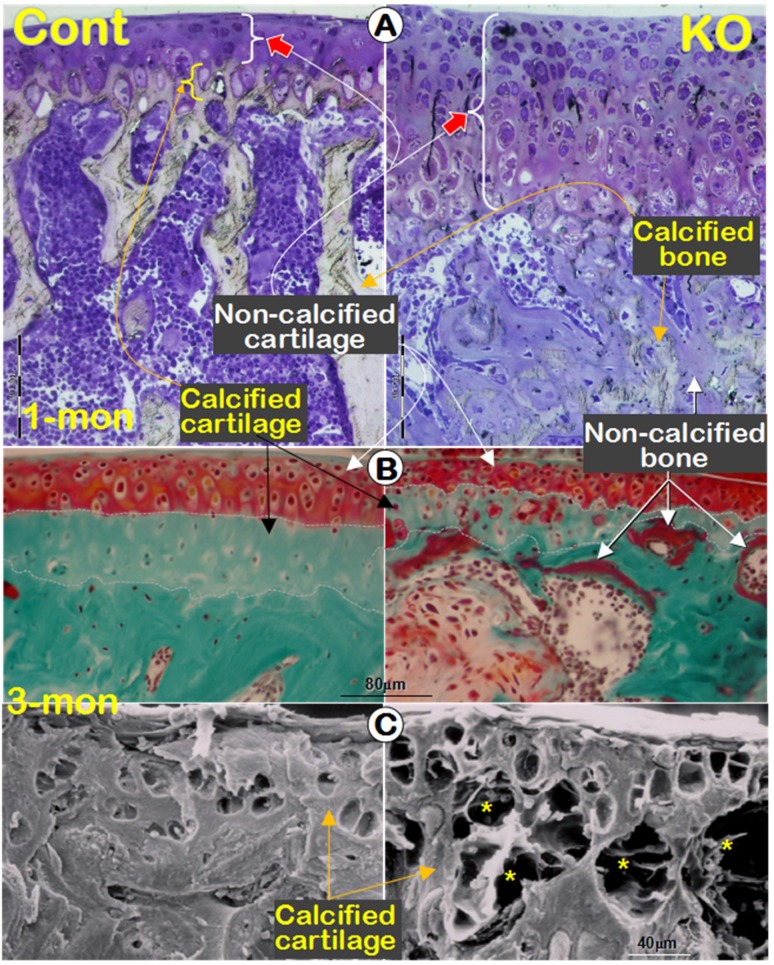

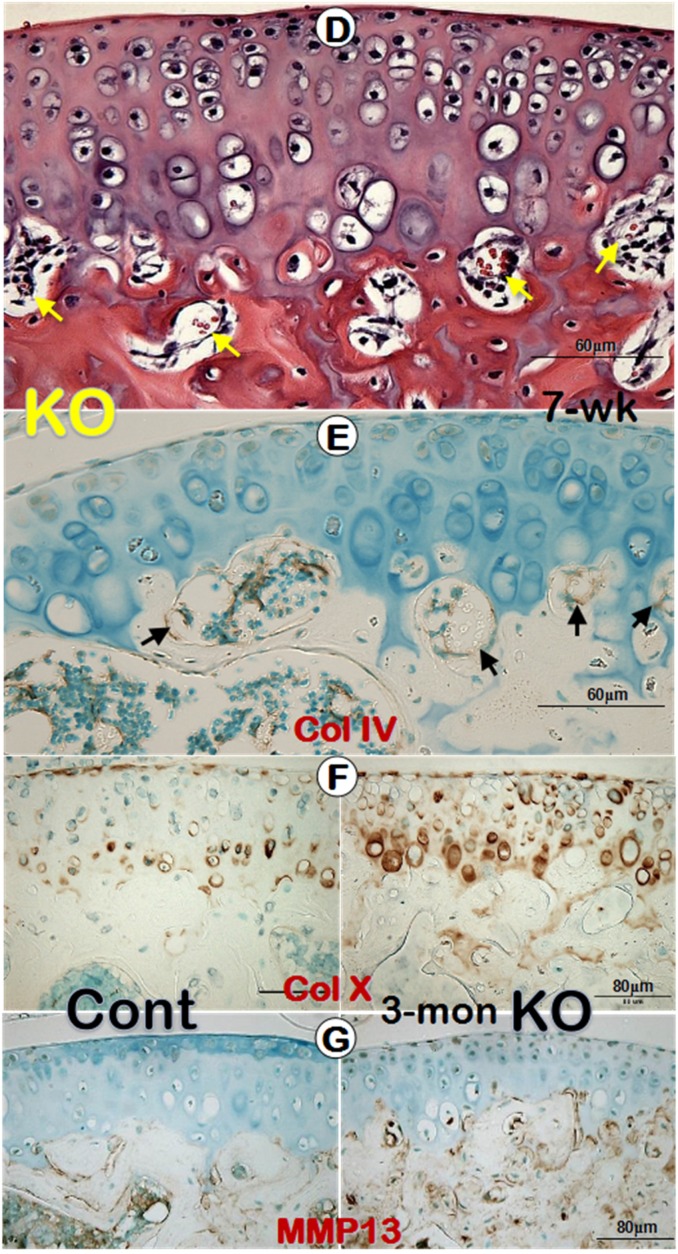

A biphasic change in the Dmp1 KO articular cartilage layer with a sharp increase of osteoid in the subchondral bone

Previously we reported a remarkable increase in hypertrophic chondrocyte layer in Dmp1 KO mice 20. Unexpectedly, in this study we observed a biphasic change in the Dmp1 KO articular cartilage layer using three non-decalcified assays. First, using toluidine blue staining we showed a dramatic expansion in hypertrophic chondrocyte layer with a lot of non-calcified subchondral bone at the age of 1-month (Figure 3A, right panel). By 3-month-old, the Goldner stain assay revealed a diminished articular cartilage, including both the non-calcified and the calcified cartilage layer in the KO mice, which was accompanied with a thick osteoid layer on the KO bone surface (Figure 3B, right panel). Furthermore, the backscattered SEM image not only confirmed the same change of the calcified cartilage in the KO mice, but also showed numerous cysts as well (Figure 3C, right panel; asterisks). The further assessment of these cysts using H&E staining revealed several vessels in these cysts, within which red blood cells could be easily found (Figure 3D). The IHC stains showed positive signals of Col IV in the endothelial cells surrounding these vessels (Figure 3E). Moreover, it's also found an expended Col X expression in the KO articular cartilage (Figure 3F) and an up-regulated MMP13 activity in the subchondral bone (Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

A biphasic change in the KO articular cartilage layer with severe defects in mineralization of the subchondral bone and abnormal blood vessel invasions. (A) Toluidine blue assay of 1-month-old non-decalcified samples showed a sharp expansion of the articular cartilage layer (especially the hypertrophic chondrocyte layer) and the poor mineralization of the subchondral bone, which stained with light blue/purple color; (B) Goldner staining of 3-month-old non-decalcified samples displayed thinning cartilage layer and abnormal calcification in the calcified cartilage and subchondral bone, which stained with red color in the KO group (right panel); (C) The resin casted SEM images revealed diminished calcified cartilage layer and many “cyst-like spaces” (asterisks) in the 3-month-old KO subchondral bone (right); (D) The H&E stained images documented many vessels within the cysts at the edge between the KO cartilage layer and subchondral bone layer (arrows); (E) The IHC images showed Col IV signals in the endothelial cells (arrows); (F-G) IHC staining displayed an increase in expressions of Col X (F, right panel) and MMP13 (G, right panel) in the KO samples.

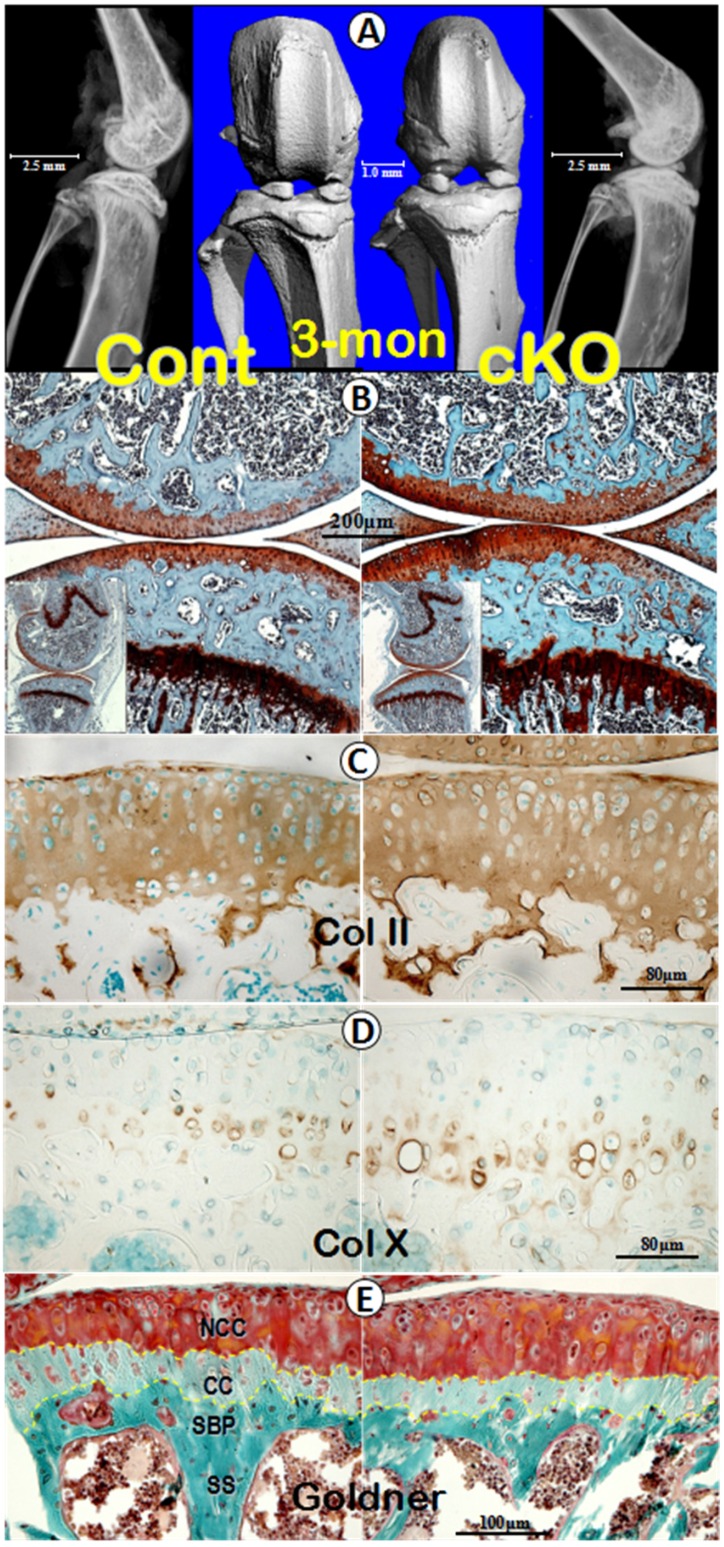

Conditional deletion of Dmp1 in hypertrophic chondrocyte had no apparent impact on the articular cartilage and growth plate

To investigate whether the OA-like phenotype in Dmp1 null mice is caused by the directly regulatory role of DMP1 in the cartilage, we conditionally knocked out Dmp1 in the hypertrophic chondrocyte by crossing the Dmp1-loxP mice to Col X Cre mice, which showed the Cre activity restricted within the hypertrophic chondrocytes 29, 30. The 3-month-old cKO offspring were collected for further evaluation. There were no notable morphological differences and histopathological changes in the cKO knee joints by radiographs and μ-CT images (Figure 4A). Further evaluations using safranin-O staining (Figure 4B), IHC assays of Col II (Figure 4C) and Col X (Figure 4D), as well as Goldner stain (Figure 4E) displayed no apparent differences between the age-matched controls and the cKO knee samples. Taken together, these data suggest that the chondrocyte-originated DMP1 in the articular cartilage may not be critical for chondrogenesis and cartilage matrix remodeling.

Figure 4.

A lack of apparent differences in levels of morphology, histopathology and molecular expressions between the control and Dmp1 cKO knee (the crossing between Dmp1-loxP and Col X Cre lines, at 3-months). (A) Representative μ-CT images (center) and radiographs (both sides) of the control (left panels) and cKO (right panels) mice; (B) safranin-O staining of knee joints revealed comparable structures at the histological levels in both the control (left) and cKO (right panel) mice, including the low (inserts) and high magnification views; (C-E) IHC images of Col II (C) and Col X (D), Goldner's masson trichrome stain images (E), displayed no apparent differences between the control (left panels) and cKO (right panels) mice, respectively. Of note, the yellow dash lines describe the tidemark that lies between articular cartilage and calcified cartilage, as well as the cement line between calcified cartilage and subchondral bone plate. NCC, non-calcified cartilage; CC, calcified cartilage; SBP, subchondral bone plate; SS, subarticular spongiosa.

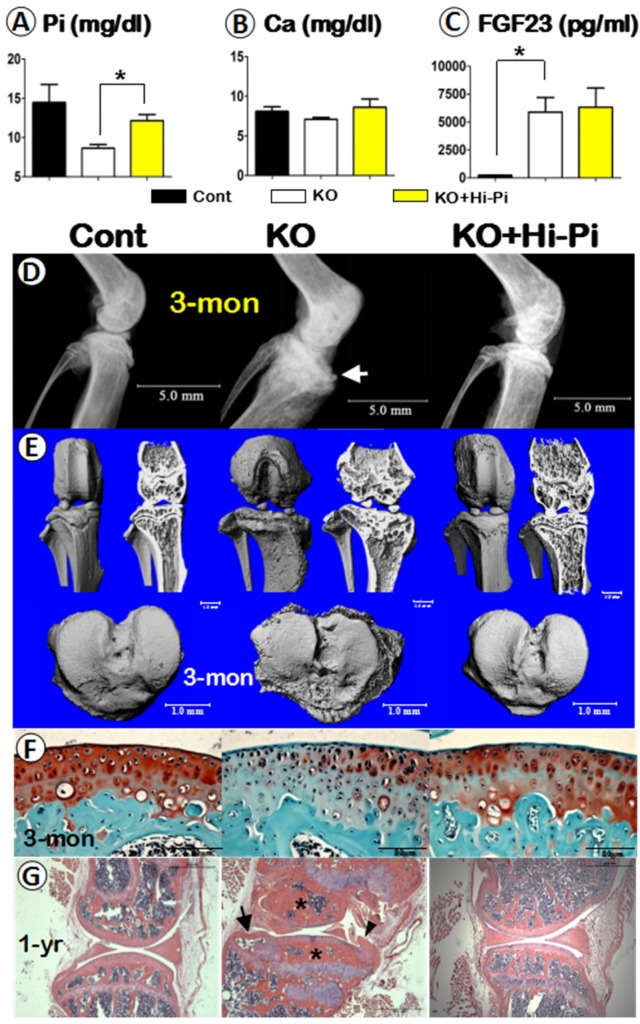

Rescue of spontaneous OA-like phenotype in Dmp1 KO mice by high-phosphate diet

As reported in the clinical case study, in which the DMP1 mutant patient without Hi-Pi treatment developed a very severe OA phenotype 19, suggesting a possible impact of the low serum Pi level on the knee joint. To test this hypothesis, we normalized the serum Pi level of Dmp1 KO mice by Hi-Pi feeding starting at the age of 3-weeks and ending at age of 3-months, then evaluated the effect of the Pi restoration in the Dmp1 KO mice. The quantified data of serum biochemistry displayed a decrease of 35% of the serum Pi in Dmp1 null mice, which is meaningfully rescued in the KO+Hi-Pi group (Figure 5A) with no apparent influence on the serum Ca (Figure 5B). However, the Hi-Pi diet treatment had no effect on the serum FGF23 level, which had a more than 24-fold increase in Dmp1 KO mice compared with WT mice (Figure 5C). The subsequent radiographs showed OA-like changes in the KO mice, including the shape of the knee joint, thickness of the subchondral bone plate, structure of the subarticular spongiosa, porosity of the tibial plateau surface, were fully rescued in the treatment group (Figure 5D). The μ-CT images further confirmed the above observation (Figure 5E). Finally, the histological studies clearly showed an apparent recover of morphology and pathohistology in Dmp1 KO mice with Hi-Pi treatment at the age of 3-months (Figure 5F). And this recovery persisted up to 1-year as the Hi-Pi continued (Figure 5G). Taken together, these rescue data based on Hi-Pi diet support the notion that it is the loss of Pi homeostasis that leads to the OA-like phenotype in the Dmp1 null knee joint.

Figure 5.

Analyses of serum biochemistry, morphology and histopathology of the control, Dmp1 KO, and the KO with Hi-Pi diet for two months. (A-C) Serum biochemistry profiles of the 3-month-old control (left columns), KO (middle columns), and KO with Hi-P treatment (right columns) groups revealed an effective rescue of the level of Pi (A), but not the levels of Ca (B) or FGF23 (C); Data are presented as “MEAN±SEM”; n=5; *P<0.05; compared to the control. (D-E) The representative radiographs (D) and μ-CT (E) images of the 3-month-old mouse knees displayed a full rescue of the overall structure in the KO+Hi-Pi group (right panels). (F) Representative safranin-O stained images displayed staining loss in the KO articular cartilage but re-involved in the KO+Hi-Pi specimen (right). (G) The H&E stain images revealed subchondral bone sclerosis (asterisks), osteophyte (arrowhead) and an cyst (arrow) in the KO knee joint, plus a apparent restoration of the histological structures in the 1-year-old KO+Hi-Pi group (right panel).

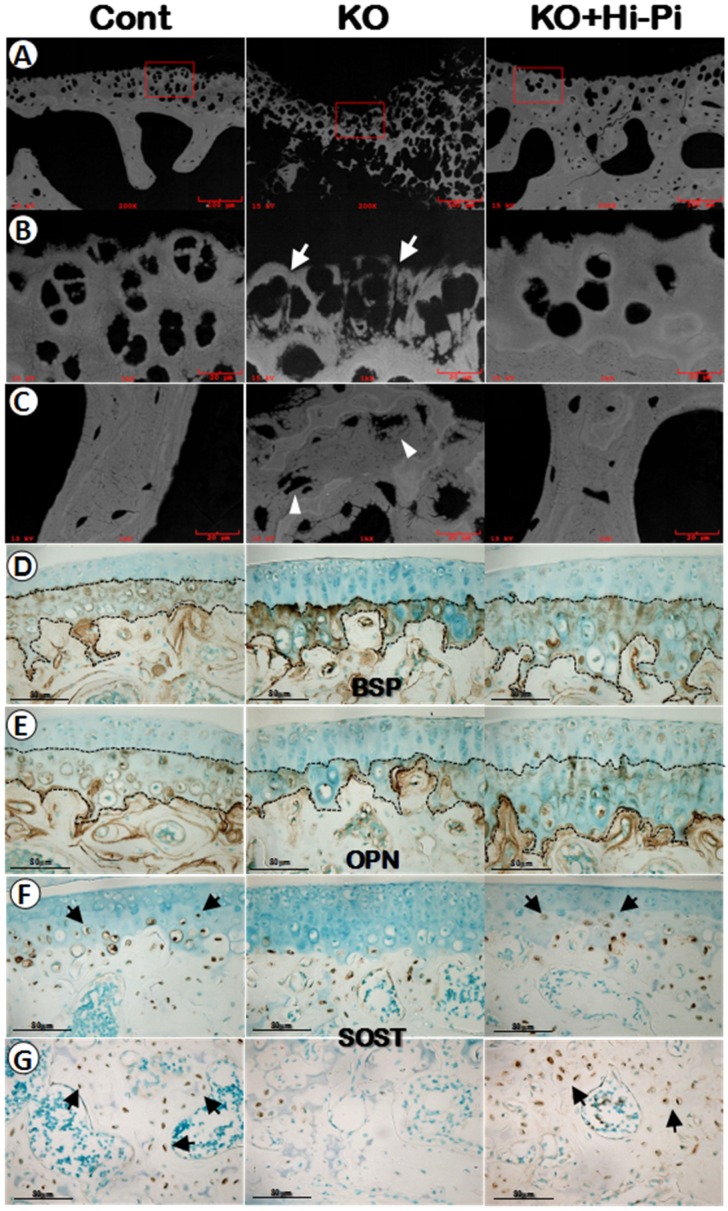

Metabolic defect in calcified cartilage and subchondral bone is the key pathological trigger in the OA development

Our previous studies of the Dmp1 KO mice with or without Hi-P treatment mainly focused on the growth plate and long bone 13, 18. Here we first used the backscattered SEM technique, in which the white color indicates high quality of minerals and grey/black areas reflect poor mineral formation, to address the impact of Dmp1 ablation and the rescue effect of the Hi-Pi diet on the calcified matrices of articulations. As shown in the Figure 6A-C (middle panels), there was impaired mineral metabolization in both the calcified cartilage and subchondral bone of the Dmp1 KO mice. While the Hi-Pi diet greatly improved the mineral status in these matrices underneath non-calcified cartilage (Figure 6A-C, right panels).

Figure 6.

Restorations of the mineralization in the calcified cartilage matrix by a Hi-Pi diet treatment at the age of 3-months. (A-C) The mineral status of the 3-month-old control (left panels), KO (middle panels), and KO+Hi-Pi (right panels) mice were detected by backscattered SEM imaging techniques (white, high mineral content) with (A) reflecting the low magnification views, (B) indicating the high magnification views of the calcified cartilage and (C) displaying the subchondral bone matrices. Arrows showed the malformed calcified cartilage and arrowheads indicated the hypomineralized bone matrix. (D-E) Anti-BSP and anti-OPN IHC staining of 3-month-old articular cartilage. Black dash lines described the tidemarks and cement lines. (F-G) Anti-SOST IHC analysis of the articular cartilage (F) and subarticular spongiosa (G) at the age of 3-months. Arrows indicate the SOST postive cells in the calcified cartilages and subchondral bones of the control (left) and the rescued KO mice (right).

Next, we used IHC assays to ask whether molecular markers are efficient for testing the pathological changes of chondrocytes and bone cells during the development of hypophosphatemia induced OA. Unexpectedly, there were no apparent changes in the expression levels of early bone markers such as BSP (Figure 6D) or OPN (Figure 6E) in either the KO or the rescued group compared to the age-matched controls (Figure 6D-E). However, the SOST, a gene highly expressed in osteocytes, was also detected in the late chondrocytes in the control and rescued knee joints but little in the KO chondrocytes (Figure 6F), suggesting that 1) there is a defect in chondrogenic and osteogenic maturation of the Dmp1 KO articular cartilage and subchondral bone; and 2) SOST is a sensitive marker to reflect the maturation of hypertrophic chondrocytes and subchondral bone cells in articulations.

Discussion

The role of DMP1 in bone biology has been well established during the last two decades, however, its function in regulating articular cartilage formation and homeostasis is still largely unknown. Here, we first characterized the pathological changes of the global Dmp1 KO knees at the levels of the gross, cell and molecule from 1-month-old to 12-month-old (mainly focusing on two time points: 7-week-old and 3-month-old), which is distinctly different from an aging related OA phenotype. Second, we showed that removing Dmp1 in hypertrophic chondrocytes had little impacts on the knee joint, excluding its direct role on development of the OA-like phenotype. Third, we demonstrated a full rescue of the Dmp1-OA phenotype by a Hi-Pi diet treatment, supporting a critical role of Pi homeostasis on the healthy knee joint.

DMP1 was originally isolated from rat dentin and was thought to be specific only to dentin 10. Later, several research groups demonstrated the expression of DMP1 in bone at an even higher level than in dentin 8, 31. More recently, DMP1 has been observed in several non-mineralized tissues, such as the brain, salivary glands, and certain tumors of epithelial origin 32-36. The identification of DMP1 in articular cartilage, as well as, its regulatory role in maintaining the chondrogenic phenotype of bone marrow stromal cells and articular chondrocytes, suggested that it may play important roles in cartilage matrix formation and remodeling 21, 23. However, the Dmp1 cKO articular cartilage didn't display apparent phenotype, supporting the notion that DMP1, which is weakly expressed in hypertrophic chondrocytes, may not be essential for or uniquely contribute to articular chondrogenesis and cartilage matrix remodeling. This finding, together with the high Pi-diet rescue data presented in this study, further confirm that the OA-like phenotype in Dmp1-KO mice is mainly secondary to hypophosphatemia. At present, we do not know how hypophosphatemia changes the articular cartilage phenotype. Our future plan is to address whether phosphorus homeostasis changes chondrogenesis using the cell lineage tracing approach combined with different cell markers.

Subchondral bone lesions are commonly associated with articular cartilage defects during the development of OA. Although promising results have been achieved in the past two decades to treat isolated cartilage defects 37, the problem of OA extending into the underlying subchondral bone has not received much attention until recently 38, 39. It is thought that the increase in bone volume, density, and stiffening of subchondral bone in OA are closely associated with repetitive responses to micro-damage/fracture caused by an imbalance in mechanical loading of the joint 40. Apparently, this is not the likely mechanism in the Dmp1-KO caused OA-like phenotype, as our data showed a biphasic change (the early expansion and late shrinkage) in the KO articular cartilage, which is closely associated with the striking defect in mineralization of both the calcified cartilage and subchondral bone. Furthermore, these changes occurred at the early developmental stage. Importantly, all these changes plus the malformed osteophytes are fully restored after two month Hi-Pi diet treatment, indicating a vital role of Pi homeostasis in maintaining the knee healthy. In fact, degenerative osteoarthropathy has been observed in young patients with XLH (X-linked hypophosphatemia mainly caused by PHEX mutations) and common to all older patients, characterized by thinning of the articular surface of ankle and knee joints and subchondral sclerosis 41, 42. Animal studies showed that Hyp mice, a murine model of XLH, recaptured the OA-like phenotype similar to the patients with XLH; and that a Hi-Pi diet treatment greatly improved the OA-like phenotype 43.

In summary, this study using the Dmp1 conventional KO mouse model has demonstrated invaluable methods in elucidating cellular and molecular changes within the context of hypophosphatemia caused OA-like phenotype. It also provides strong evidence that a stable serum Pi homeostasis is essential for both the early intervention and the long-term management of the osteoarthritis-related complications of the hypophosphatemia. Importantly, our data suggest that disruption of extracellular factors in the hypophosphatemic environment severely impacts the distinct architecture of articular cartilage. Finally, this study will have a broad application to all other OA-like formats, which are due to the disruption of the Pi homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chunlin Qin for his generous presentations of anti-DMP1-C-terminal polyclonal antibody and anti-BSP monoclonal antibody. This study was partially supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DE025014 to JQF, DE024797 to SEH; and National Natural Science Foundations of China No. 81070824 and 81371141 to QZ, and No. 81500814 to SXL.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA. et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK. et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valdes AM, Spector TD. The contribution of genes to osteoarthritis. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:45–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.08.007. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valdes AM, Spector TD. The contribution of genes to osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:581–603. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spector TD, MacGregor AJ. Risk factors for osteoarthritis: genetics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(Suppl A):S39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Six genes expressed in bones and teeth encode the current members of the SIBLING family of proteins. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44(Suppl 1):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher LW, Torchia DA, Fohr B, Young MF, Fedarko NS. Flexible structures of SIBLING proteins, bone sialoprotein, and osteopontin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:460–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fen JQ, Zhang J, Dallas SL, Lu Y, Chen S, Tan X. et al. Dentin matrix protein 1, a target molecule for Cbfa1 in bone, is a unique bone marker gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1822–31. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.10.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng JQ, Huang H, Lu Y, Ye L, Xie Y, Tsutsui TW. et al. The Dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1) is specifically expressed in mineralized, but not soft, tissues during development. J Dent Res. 2003;82:776–80. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George A, Sabsay B, Simonian PA, Veis A. Characterization of a novel dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein. Implications for induction of biomineralization. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12624–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang B, Maciejewska I, Sun Y, Peng T, Qin D, Lu Y. et al. Identification of full-length dentin matrix protein 1 in dentin and bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82:401–10. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9140-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin C, D'Souza R, Feng JQ. Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1): new and important roles for biomineralization and phosphate homeostasis. J Dent Res. 2007;86:1134–41. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng JQ, Ward LM, Liu S, Lu Y, Xie Y, Yuan B. et al. Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1310–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye L, MacDougall M, Zhang S, Xie Y, Zhang J, Li Z. et al. Deletion of dentin matrix protein-1 leads to a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, hypomineralization, and expanded cavities of pulp and root canal during postnatal tooth development. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19141–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin S, Zhang Q, Cao Z, Lu Y, Zhang H, Yan K. et al. Constitutive nuclear expression of dentin matrix protein 1 fails to rescue the Dmp1-null phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:21533–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.543330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin SX, Zhang Q, Zhang H, Yan K, Ward L, Lu YB. et al. Nucleus-targeted Dmp1 transgene fails to rescue dental defects in Dmp1 null mice. Int J Oral Sci. 2014;6:133–41. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bastepe M, Benet-Pages A, Amyere M, Wagenstaller J, Muller-Barth U. et al. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1248–50. doi: 10.1038/ng1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R, Lu Y, Ye L, Yuan B, Yu S, Qin C. et al. Unique roles of phosphorus in endochondral bone formation and osteocyte maturation. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1047–56. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makitie O, Pereira RC, Kaitila I, Turan S, Bastepe M, Laine T. et al. Long-term clinical outcome and carrier phenotype in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia caused by a novel DMP1 mutation. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2165–74. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye L, Mishina Y, Chen D, Huang H, Dallas SL, Dallas MR. et al. Dmp1-deficient mice display severe defects in cartilage formation responsible for a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6197–203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412911200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Y, Gandhi V, Prasad M, Yu W, Wang X, Zhu Q. et al. Distribution of small integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLING) in the condylar cartilage of rat mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:272–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y, Ma S, Zhou J, Yamoah AK, Feng JQ, Hinton RJ. et al. Distribution of small integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLING) in the articular cartilage of the rat femoral head. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:1033–43. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.956771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasadam I, Zhou Y, Shi W, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Role of dentin matrix protein 1 in cartilage redifferentiation and osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2014;53:2280–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng JQ, Scott G, Guo D, Jiang B, Harris M, Ward T. et al. Generation of a conditional null allele for Dmp1 in mouse. Genesis. 2008;46:87–91. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang B, Cao Z, Lu Y, Janik C, Lauziere S, Xie Y. et al. DMP1 C-terminal mutant mice recapture the human ARHR tooth phenotype. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2155–64. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin C, Brunn JC, Cook RG, Orkiszewski RS, Malone JP, Veis A. et al. Evidence for the proteolytic processing of dentin matrix protein 1. Identification and characterization of processed fragments and cleavage sites. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34700–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang B, Sun Y, Maciejewska I, Qin D, Peng T, McIntyre B. et al. Distribution of SIBLING proteins in the organic and inorganic phases of rat dentin and bone. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:104–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y, Yuan B, Qin C, Cao Z, Xie Y, Dallas SL. et al. The biological function of DMP-1 in osteocyte maturation is mediated by its 57-kDa C-terminal fragment. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:331–40. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebhard S, Hattori T, Bauer E, Schlund B, Bosl MR, de Crombrugghe B. et al. Specific expression of Cre recombinase in hypertrophic cartilage under the control of a BAC-Col10a1 promoter. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:693–9. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jing Y, Zhou X, Han X, Jing J, von der Mark K, Wang J. et al. Chondrocytes Directly Transform into Bone Cells in Mandibular Condyle Growth. J Dent Res. 2015;94:1668–75. doi: 10.1177/0022034515598135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Souza RN, Cavender A, Sunavala G, Alvarez J, Ohshima T, Kulkarni AB. et al. Gene expression patterns of murine dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1) and dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) suggest distinct developmental functions in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:2040–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher LW, Jain A, Tayback M, Fedarko NS. Small integrin binding ligand N-linked glycoprotein gene family expression in different cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8501–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terasawa M, Shimokawa R, Terashima T, Ohya K, Takagi Y, Shimokawa H. Expression of dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) in nonmineralized tissues. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22:430–8. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Expression of SIBLINGs and their partner MMPs in salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2004;83:664–70. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Renal expression of SIBLING proteins and their partner matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) Kidney Int. 2005;68:155–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. SIBLING expression patterns in duct epithelia reflect the degree of metabolic activity. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:403–9. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7075.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:889–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaiprakash A, Prasadam I, Feng JQ, Liu Y, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Phenotypic characterization of osteoarthritic osteocytes from the sclerotic zones: a possible pathological role in subchondral bone sclerosis. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:406–17. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhen G, Wen C, Jia X, Li Y, Crane JL, Mears SC. et al. Inhibition of TGF-beta signaling in mesenchymal stem cells of subchondral bone attenuates osteoarthritis. Nat Med. 2013;19:704–12. doi: 10.1038/nm.3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burr DB, Radin EL. Microfractures and microcracks in subchondral bone: are they relevant to osteoarthrosis? Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2003;29:675–85. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(03)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reid IR, Hardy DC, Murphy WA, Teitelbaum SL, Bergfeld MA, Whyte MP. X-linked hypophosphatemia: a clinical, biochemical, and histopathologic assessment of morbidity in adults. Medicine. 1989;68:336–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardy DC, Murphy WA, Siegel BA, Reid IR, Whyte MP. X-linked hypophosphatemia in adults: prevalence of skeletal radiographic and scintigraphic features. Radiology. 1989;171:403–14. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.2.2539609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang G, Vanhouten J, Macica CM. An atypical degenerative osteoarthropathy in Hyp mice is characterized by a loss in the mineralized zone of articular cartilage. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89:151–62. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]