Abstract

Objective

To compare methodology used to assign cause of and factors contributing to maternal death.

Design

Reproductive Age Mortality Study.

Setting

Malawi.

Population

Maternal deaths among women of reproductive age.

Methods

We compared cause of death as assigned by a facility‐based maternal death review team, an expert panel using the International Classification of Disease, 10th revision (ICD‐10) cause classification for deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (ICD‐MM) and a computer‐based probabilistic program (Inter VA‐4).

Main outcome measures

Number and cause of maternal deaths.

Results

The majority of maternal deaths occurred at a health facility (94/151; 62.3%). The estimated maternal mortality ratio was 363 per 100 000 live births (95% CI 307–425). There was poor agreement between cause of death assigned by a facility‐based maternal death review team and an expert panel (κ = 0.37, 86 maternal deaths). The review team considered 36% of maternal deaths to be indirect and caused by non‐obstetric complications (ICD‐MM Group 7) whereas the expert panel considered only 17.4% to be indirect maternal deaths with 33.7% due to obstetric haemorrhage (ICD‐MM Group 3). The review team incorrectly assigned a contributing condition rather than cause of death in up to 15.1% of cases. Agreement between the expert panel and Inter VA‐4 regarding cause of death was good (κ = 0.66, 151 maternal deaths). However, contributing conditions are not identified by Inter VA‐4.

Conclusions

Training in the use of ICD‐MM is needed for healthcare providers conducting maternal death reviews to be able to correctly assign underlying cause of death and contributing factors. Such information can help to identify what improvements in quality of care are needed.

Tweetable abstract

For maternal deaths assigning cause of death is best done by an expert panel and helps to identify where quality of care needs to be improved.

Keywords: Cause of death classification, expert panel, ICD‐MM, InterVA‐4, maternal death review

Tweetable abstract

For maternal deaths assigning cause of death is best done by an expert panel and helps to identify where quality of care needs to be improved.

Introduction

Reduction of maternal mortality has long been a global health priority with a target set for a 75% decrease in the maternal mortality ratio compared with 1990 by the end of 2015 (Millennium Development Goal 5a). The new global target is fewer than 70 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births by 2030,1, 2 Although significant progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5a has been reported in the past decade, further improvements are needed.2, 3, 4

Inconsistencies in coding and assigning of the underlying cause of maternal deaths exist across countries.5, 6, 7 Accurate identification and classification of cause of death may prove difficult in the absence of clear criteria and guidance because of the relationships between different conditions that may be reported as cause of death.8 This potentially compromises the quality and interpretation of information available for planning effective interventions aimed at reducing maternal mortality and morbidity.

The methodologies for maternal death audit (or review) start with the simplest facility‐based case review, which focuses particularly on tracing the ‘story’ of each woman who died with the aim of identifying what went well and any avoidable factors which, if addressed, could prevent future deaths.9 A similar process can be performed at community level (for women who died at home or in a health facility) and is then referred to as a ‘verbal autopsy’.

Data obtained via verbal autopsy or facility‐based review are usually analysed by healthcare providers themselves (including midwives and obstetrician–gynaecologists) or by an external expert panel. In recent years, there has been an interest in using computer‐coded verbal autopsy data to improve consistency, inter‐observer agreement and comparability.10, 11, 12 The InterVA‐4 model is a computer‐based probabilistic model that provides a likely cause of death.13

A new standard classification for maternal and pregnancy‐related deaths to facilitate national and international comparisons (ICD‐MM) was developed in 2012.5 This classification is an application of the International Classification of Disease, 10th revision, to deaths in pregnancy, labour and puerperium and defines three types of maternal deaths: direct, indirect and unspecified, with eight mutually exclusive groups of underlying causes. A ninth group is used for coincidental causes not related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management5 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Type of maternal death and group for underlying cause of death of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium

| Type | Group |

|---|---|

| Direct maternal death | 1. Pregnancy with abortive outcome |

| 2. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | |

| 3. Obstetric haemorrhage | |

| 4. Pregnancy‐related infection | |

| 5. Other obstetric complications | |

| 6. Unanticipated complications of management | |

| Indirect maternal death | 7. Nonobstetric complications |

| Unspecified | 8. Unknown/undetermined causes of death |

| Death during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (but not maternal death) | 9. Coincidental causes |

Source: World Health Organization.5

We sought to compare cause of death and contributing factors as assigned by an expert panel using ICD‐MM with cause as assigned by a facility‐based review team and a computer‐based program (InterVA‐4).

Methods

In this study we included all maternal deaths that occurred in one rural district, (Mangochi) in Malawi during 1 year (December 2011 to November 2012 inclusive). The district has a population of 916 274 distributed across nine traditional authorities (2008 census data). Of these, 207 868 were women of reproductive age. Maternity services are delivered at primary and secondary healthcare levels (42 health centres, three rural hospitals, one district hospital). Women can be referred to one of two tertiary hospitals in the country, the nearest of which is 110 km away. The district is perceived to be one of the districts with the highest maternal mortality ratio in Malawi but there is no district‐level data available.

Deaths were identified through a prospective Reproductive Age Mortality Study where all deaths among women of reproductive age were identified whether these occurred at health facility level or at home. Health facility staff reported all deaths that occurred not only in the maternity wards but in any section of the health facility. Research staff visited all health facilities at least once every quarter and cross‐checked all registers. Community health workers reported all deaths which occurred at home and quarterly review meetings were held with community workers and village heads to identify any deaths that may not yet have been reported. At the end of every month the two data sources (health facility and community) were compared, and any duplicates were removed.

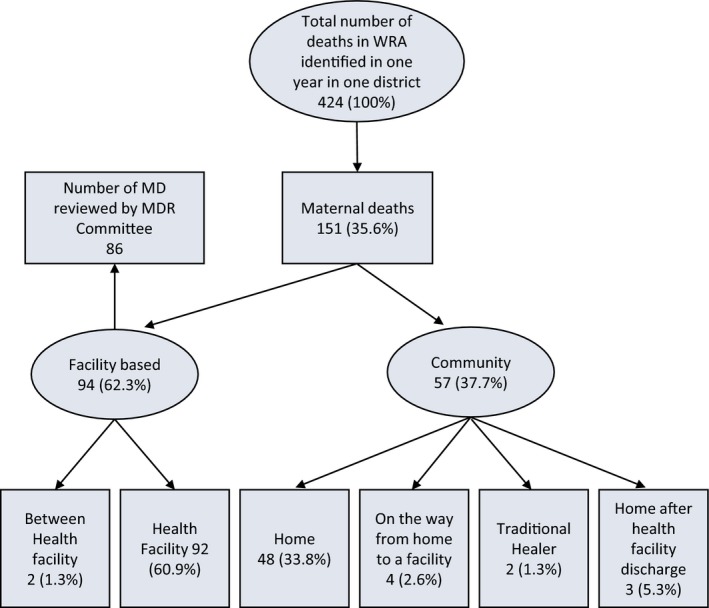

Research staff classified the death of a woman of reproductive age as a maternal death (or not) using the ICD‐10 definition of maternal death.14 Out of 424 deaths among women of reproductive age, 151 were identified to be maternal deaths, 94 occurred at a healthcare facility and 57 in the community (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of deaths among women of reproductive age (WRA), number of maternal deaths (MD) and place of death identified using a Reproductive Age Mortality Study (RAMOS).

This study sought to compare recorded cause of death assigned by healthcare providers themselves with cause of death assigned using InterVA‐4 or an expert panel. All 57 deaths occurring in the community were reviewed using verbal autopsy.15

The facility review team was comprised of doctors, clinical officers, medical assistants, nurses and midwives and administrative staff working in health facilities in the district. They were not trained in ICD‐MM and in this setting there is no pathologist available. Cause of death was assigned by the team for 86 of the 94 maternal deaths after review of the case notes and was documented using the standard Malawi maternal death review form provided by the Ministry of Health.

The expert panel consisted of two obstetricians and a midwife (each with experience in low‐resource settings and in maternal death review). The expert panel applied the ICD‐MM classification system to all 151 maternal deaths using information from verbal autopsy and facility‐based review forms and assigned an underlying cause of death and contributing conditions. The panel subsequently met to reach consensus for cases where there were differences in opinion. Agreement of three reviewers was necessary to assign a final cause of death. In cases where three experts did not reach agreement, a fourth independent senior obstetrician–gynaecologist with experience of working in developing countries was consulted to reach agreement.

Underlying cause of death was defined as: the disease or condition that initiated the morbid chain of events leading to death. Contributing conditions were defined as: conditions present that may have contributed to (or be associated with) but did not directly cause death.5 We compared cause of death and contributing conditions for facility‐based maternal deaths as assigned by the in‐country review team with those assigned by the expert panel.

The InterVA‐4 model is an online computer‐based probabilistic model that can be used to determine cause of death using verbal autopsy data (see Appendix S1).13 The program considers malaria and HIV⁄AIDS prevalence in the region. For Malawi, these were set at high levels.

We compared cause of death for 86 maternal deaths with cause assigned by the facility‐based review team, as generated by the InterVA‐4 probabilistic model and as assigned by the expert panel. We also compared cause of death for all 151 cases obtained by the expert panel and InterVA‐4. Cohen's κ statistic was calculated to assess the level of agreement for all comparisons.16 We only compared contributing conditions assigned by the expert panel and review team because InterVA‐4 does not produce contributing conditions.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the College of Medicine Ethics Committee in Malawi.

Results

Number of maternal deaths and maternal mortality ratio

In Malawi, there is no civil registration system in place. Empirically, the number of bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccinations has been found to be a reasonable proxy for live births as babies are immunised at birth.17 In Malawi, immunisation coverage is almost universal (97%) and with a strong Health Management information System in place data are collected regarding the number of immunised babies across the country. We estimated that a total of 41 623 births occurred during the study period.18 We identified 151 maternal deaths among women of reproductive age, giving an estimated maternal mortality ratio of 363 per 100 000 live births (95% CI 307–425). No previous estimates were available for the district.

Underlying cause of death assigned by maternal death review team, expert panel and InterVA‐4

The cause of death for 86 facility‐based maternal deaths assigned by the facility‐based maternal death review team, expert panel and InterVA‐4 software were compared (Table 2). There were no major differences between cause assigned by expert panel and InterVA‐4.

Table 2.

Underlying cause of death for facility‐based maternal deaths as assigned by the facility‐based maternal death review team, an expert panel and probabilistic computer‐based program (InterVA‐4) (n = 86)

| ICD‐MM type | ICD‐MM group | Maternal death review team (%) | Expert panel (%) | InterVA4 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct maternal death | 1. Pregnancy with abortive outcome | 6 (7.0) | 12 (14.0) | 13 (15.1) |

| 2. Hypertensive disorders | 7 (8.1) | 10 (11.6) | 14 (16.3) | |

| 3. Obstetric haemorrhage | 16 (18.6) | 29 (33.7) | 26 (30.2) | |

| 4. Pregnancy related infections | 7 (8.1) | 12 (14.0) | 15 (17.4) | |

| 5. Other obstetric complications | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 6. Unanticipated complications of management | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Indirect maternal death | 7. Nonobstetric complications | 31 (36.0) | 15 (17.4) | 13 (15.1) |

| Unspecified | 8. Unknown/ undetermined | 2 (2.3) | 5 (5.8) | 3 (3.5) |

| Contributing conditions (assigned as underlying cause of death) | 13 (15.1) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | |

| NC: No code available for condition in ICD‐MM | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 86 (100) | 86 (100) | 86 (100) | |

However, a significant difference was observed between cause of death assigned by the review team and the two other groups (expert panel and InterVA‐4). Both expert panel and InterVA‐4 software identified more direct maternal deaths (76.8% and 80.2%, respectively) than the facility‐based maternal death review team (45.3%). The review team more frequently assigned an indirect cause of maternal death (36%) compared with the expert panel and InterVA‐4 (17.4% and 15.1%, respectively).

The maternal death review team identified non‐obstetric complications as cause of death in 36% (indirect maternal deaths) compared with 17.4% and 15.1% by the expert panel and InterVA‐4 software, respectively. On the other hand the expert panel and InterVA‐4 attributed more cases to obstetric haemorrhage (33.7% and 30.2%, respectively) compared with 18.6% by the review team. In addition the review team assigned one or more contributing conditions as underlying cause of death in 15.1% of maternal deaths. Both the expert panel and InterVA‐4 more frequently identified pregnancy‐related infection and abortion‐related death as cause of death (14% for both compared with 8.1% and 7% by review team, respectively). The percentage of cases for which no underlying cause could be identified was 5.8% for the expert panel, 3.5% for InterVA‐4 and 2.3% for the facility‐based maternal death team.

Cohen's κ for the agreement level between the expert panel and review team showed agreement in 46.5% (40/86) (κ = 0.37, slight agreement).

Contributing conditions

The maternal death review team identified contributing conditions in 69 (87.3%) of the 86 facility‐based maternal deaths with the most common contributing condition being severe anaemia (15.9%; 11/69). HIV complicating pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium, and ruptured uterus each contributed to 13.0% (9/69). Obstructed labour was considered a contributing condition in 10% (7/69).

In general, contributing conditions identified by the expert panel tended to be the same as those identified by the maternal death review team; obstructed labour in 37.7% (26/69) of cases, prolonged labour in 21.3% (15/69) but the expert panel identified additional contributing conditions such as precipitated labour 8.7% (6/69), multiple gestation and premature rupture of the membranes 4.3% each (3/69) and grand multiparity in two cases (2.8%). Based upon ICD‐MM definitions, the facility‐based review team was noted to have assigned a contributing condition as the ‘underlying cause of death’ in 15.1% of maternal deaths (13/86).

It was not possible to calculate Cohen's κ statistic for level of agreement because the variability between contributing conditions assigned by the groups was too diverse. Cohen's κ statistic requires a two‐way table with the same variables.

Cause of death assigned by expert panel and using InterVA‐4

Verbal autopsy was conducted for all 151 maternal deaths and cause of death identified using the InterVA‐4 software was compared with cause assigned by the expert panel. To allow for meaningful comparison, cause assigned by InterVA‐4 was classified according to the ICD‐MM groupings. There was only a minimal difference for cause assigned by InterVA‐4 and the expert panel for ICD‐MM Groups 1–7 (Table 3). Overall there was substantial agreement between cause of death assigned by the expert panel and InterVA‐4 (73.5%, κ = 0.66, 151 maternal deaths).

Table 3.

Underlying cause of maternal death assigned using probabilistic model (InterVA‐4) compared with expert panel using ICD‐MM (n = 151)

| ICD‐MM type | ICD‐MM group | Expert panel (%) | InterVA‐4 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct maternal death | 1. Pregnancy with abortive outcome | 16 (10.6) | 15 (9.9) |

| 2. Hypertensive disorders | 24 (15.9) | 19 (12.6) | |

| 3. Obstetric haemorrhage | 51 (33.7) | 53 (35.1) | |

| 4. Pregnancy related infections | 20 (13.2) | 22 (14.6) | |

| 5. Other obstetric complications | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | |

| 6. Unanticipated complications of management | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Indirect maternal death | 7. Nonobstetric complications | 32 (21.2) | 26 (17.3) |

| Unspecified | 8. Unknown/undetermined | 5 (3.3) | 12 (7.9) |

| Contributing conditions (assigned as underlying cause of death) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | |

| NC: No code available for condition in ICD‐MM | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 151 (100) | 151 (100) |

The expert panel assigned more maternal deaths to unspecified causes (7.9% (12/151) than InterVA‐4 (1.3%, 2/151). The InterVA‐4 assigned a contributing condition as underlying cause of death for two maternal deaths.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the underlying cause of maternal death as assigned by an expert panel trained in the application of the new ICD‐MM cause of death classification, and a probabilistic computer program (InterVA‐4) with type and cause of maternal deaths assigned by a facility‐based review team.

Main findings

There were marked discrepancies with regard to cause of death as assigned by an untrained facility‐based review team compared with that assigned by an expert panel using the ICD‐MM classification (κ = 0.37, 86 maternal deaths). In contrast, the level of agreement between cause assigned using InterVA‐4 and the expert panel was good (κ = 0.66, 151 maternal deaths). The distribution of type and cause of maternal death obtained is consistent with the current literature on cause of maternal deaths in low‐ and middle‐income settings with the majority recognised to be direct (73%) rather than indirect (27.5%) maternal deaths.19 This study also demonstrates that it is possible with relatively simple information (case notes with or without verbal autopsy) to identify a clear underlying cause of death in the majority of maternal deaths with only a small proportion remaining undetermined (between 2.3% and 5.8%). However, it is clear that with regard to definition, there is confusion between what is the ‘underlying cause of death’ and what is a ‘contributing condition’, especially at the level of a facility‐based review team.

Strengths and limitations

Although previous studies have compared underlying cause of death as assigned by physicians (referred to as experts in this study) with computer‐coded cause of death,10, 20 to the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to compare cause of death assigned by a facility‐based review team (comprised of different cadres of healthcare providers expected to review maternal and perinatal deaths) with cause of death as assigned by an external expert panel and the InterVA‐4 software.

The expert panel comprised two obstetricians and a senior midwife experienced and knowledgeable about the new ICD‐MM classification. In contrast, the maternal death review team used a standard review form currently in use in many sub‐Saharan countries and had no training in the use of the ICD‐MM classification, which was published in 2012. Cause of death was assigned based upon their professional and clinical knowledge.

Interpretation

The findings of this study are in agreement with those of a study conducted in Pakistan, which compared hospital‐assigned cause of death with physician‐coded verbal autopsy data.21 The study showed complete agreement for direct maternal deaths but weak agreement for other causes and for indirect maternal deaths (κ = 0.378). Poor agreement (κ = 0.219) was also obtained when comparing the cause of death assigned by healthcare providers with that by an expert panel using ICD‐MM in a previous study from Malawi.6 It is plausible that when maternal deaths are reviewed ‘in‐house’, the local team may miss important factors and emphasise relatively unimportant ones (such as anaemia) due to defensive medicine or reluctance to seem critical of colleagues.22

The above findings have implications for policy‐makers, planning and resource allocation. Inaccurate reporting of cause of death limits the validity and usefulness of mortality indicators for policy, research and applied public health decisions.23, 24 Accurate cause of death attribution is considered to be increasingly important to guide national and international efforts aimed at reducing maternal deaths in the post‐Millennium Development Goal agenda.5 Inconsistencies across countries makes it difficult to correctly plan mortality reduction strategies and are also of concern if they are incorrect but used to inform planning at national and international levels. It is also of concern that this could mean that policy decisions globally as well as locally are based on intrinsically faulty data.

Providing a maternal death review form that will help maternal death review teams extract from case notes or interviews with family all the necessary information that is needed to apply ICD‐MM will make it easier to correctly and more consistently assign a single underlying cause of death and separately identify the contributing conditions.

The expert panel had no problems applying ICD‐MM classification to data obtained either at a facility or community level, particularly for conditions such as obstructed labour, HIV and anaemia, which are common and, in the past, have often wrongly been assigned as cause of death rather than a contributing condition (with other direct cause of death, e.g. haemorrhage).

We found a high level of agreement between the expert panel and InterVA‐4 software. Other studies have similarly reported levels of agreement ranging from 50% to 83%.11, 25, 26, 27 However, InterVA‐4 identified cause of death mostly to the level of ICD‐MM group only. Expert panel classification of cause of death remains the reference standard against which to monitor performance of other methods of cause attribution.26 On the other hand, legitimate concerns remain as to standardisation between different experts, the lack of trained expert panels, and the sheer volume of work involved in reviewing large numbers of deaths in low‐ and middle‐income settings.26, 27, 28 The InterVA model is freely available in the public domain and is much less labour intensive and offers 100% consistency.11, 29 However, application of a probabilistic computer program does not in itself result in clinicians conducting in‐depth review of cases to identify what went well and/or where quality is sub‐standard and needs to be improved.

Conclusion

Accurate determination of the underlying cause of maternal death is important to promote national and international comparability and to ensure targeted resource allocation to end preventable maternal deaths. It is critical that countries adopt clear and internationally agreed definitions for ‘underlying cause of death’ and ‘contributing condition’. National data collection forms used to evaluate care provided and factors pertaining to a maternal death should be revised to explicitly include variables used in the ICD‐MM classification including; type of maternal death and group level for cause of maternal death. A section setting out the most frequently occurring specific causes of death (below Group level), contributing conditions and ICD‐MM codes could be added to review forms. Training in the application of ICD‐MM should be a part of midwifery and medical curricula and in‐service training.

An expert panel to review maternal deaths is the reference standard. The InterVA‐4 model could help with analysis of large data sets and promote standardisation of verbal autopsy data. However, we note that to do so, InterVA‐4 requires further refinement if it is to provide information on more specific cause of death (below the ICD‐MM Group level).

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests available to view online as supporting information.

Contributions to authorship

FM designed the study, developed the methodology, collected the data, performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. NvdB designed and supervised the study, assisted with data analysis and wrote the manuscript. RU assisted with data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Details of ethics approval

Ethical approval was received from COMREC, the Malawi College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (P.06/11/1087) on 3 July 2011 and the LSTM Ethics Committee (Research Protocol 11.76) on 31 August 2011.

Funding

This research formed part of FM's doctoral thesis, which was funded by The Icelandic International Development Agency (ICEIDA) and the Sir Halley Stewart Trust.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Description of InterVA (Verbal Autopsy) model to assign cause of death.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr M. Chalupowski for help with assigning cause of death using ICD‐MM.

Mgawadere F, Unkels R, van den Broek N. Assigning cause of maternal death: a comparison of findings by a facility‐based review team, an expert panel using the new ICD‐MM cause classification and a computer‐based program (InterVA‐4). BJOG 2016;123: 1647–1653.

References

- 1. United Nations . United Nations Millenium Declaration. Resolution A/RES/55/2. New York: United Nations Department of Public Information, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Strategies Toward Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/maternal_perinatal/epmm/en/] Accessed 5 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, the World Bank, the United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality to 2013: Estimates by the WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA . Trends in Maternal Mortality 1990 to 2013: Estimates by the WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1990. p 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi M, Ahn SY, Wang M, Makela SM, et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet 2010;375:1609–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . The WHO Application of ICD‐10 to Deaths During Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Puerperium: ICD‐MM. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/9789241548458/en/] Accessed 6 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Owolabi H, Ameh C, Bar‐Zeev S, Adaji S, Kachale F, van den Broek N. Establishing cause of maternal death in Malawi via facility‐based review and application of the ICD‐MM classification. BJOG 2014;121:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ameh CA, Adegoke A, Pattinson R, van den Broek N. Using the new ICD‐MM classification system for attribution of cause of maternal death‐a pilot study. BJOG 2014;121:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research . Beyond the Numbers: Reviewing Maternal Deaths and Complications to Make Pregnancy Safer. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241591838/en/] Accessed 23 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lozano R, Lopez AD, Atkinson C, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Murray CJ, et al. Performance of physician‐certified verbal autopsies: multisite validation study using clinical diagnostic gold standards. Popul Health Metr 2011;9:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Byass P, Fottrell E, Dao Lan H, Berhane Y, Corrah T, Kahn K, et al. Refining a probabilistic model for interpreting verbal autopsy data. Scand J Public Health 2006;34:26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Barofsky JT, Bryson‐Cahn C, Lozano R. Estimating population cause‐specific mortality fractions from in‐hospital mortality: validation of a new method. PLoS Med 2007;4:e326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization . WHO Technical Consultation on Verbal Autopsy Tools. Geneva. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14. WHO . Maternal death surveillance and response: technical guidance. Information for action to prevent maternal death, 2013. [www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/ maternal_death_surveillance/en/] Accessed 25 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . Verbal Autopsy Standards Ascertaining and Attributing Cause of Death. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 3rd edn Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Songane FF, Bergström S. Quality of registration of maternal deaths in Mozambique: a community‐based study in rural and urban areas. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malawi Ministry of Health . Malawi Health Management Information System (HMIS) Lilongwe. Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi‐Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, Heuton KR, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:980–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bauni E, Ndila C, Mochamah G, Nyutu G, Matata L, Ondieki C, et al. Validating physician‐certified verbal autopsy and probabilistic modeling (InterVA) approaches to verbal autopsy interpretation using hospital causes of adult deaths. Popul Health Metrics 2011;9:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Midhet F. Validating the verbal autopsy questionnaire for maternal mortality in Pakistan. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2008;2:91–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geller S, Koch A, Martin N, Prentice P, Rosenberg D. Comparing two review processes for determination of preventability of maternal mortality in Illinois. Mat Child Healt J 2015;19:2621–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kircher T, Anderson RE. Cause of death. Proper completion of the death certificate. J Am Med Assoc 1987;258:349–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Messite J, Stellman SD. Accuracy of death certificate completion: the need for formalized physician training. J Am Med Assoc 1996;275:794–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Byass P, Chandramohan D, Clark SJ, D'Ambruoso L, Fottrell E, Graham WJ, et al. Strengthening standardised interpretation of verbal autopsy data: the new InterVA‐4 tool. Glob Health Action 2012;5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Byass P, Lan Huong D, Van Minh H. A probabilistic approach to interpreting verbal autopsies: methodology and preliminary validation in Vietnam. Scand J Public Health 2003;31:32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tensou B, Araya T, Telake DS, Byass P, Berhane Y, Kebebew T, et al. Evaluating the InterVA model for determining AIDS mortality from verbal autopsies in the adult population of Addis Ababa. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:547–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fottrell E, Byass P, Ouedraogo TW, Tamini C, Gbangou A, Sombié I, et al. Revealing the burden of maternal mortality: a probabilistic model for determining pregnancy‐related causes of death from verbal autopsies. Popul Health Metr 2007;5:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fantahun M, Fottrell E, Berhane Y, Wall S, Högberg U, Byass P. Assessing a new approach to verbal autopsy interpretation in a rural Ethiopian community: the InterVA model. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:204–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Description of InterVA (Verbal Autopsy) model to assign cause of death.