Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of 6 months of open‐label, uncontrolled extension treatment with lurasidone in patients with a diagnosis of bipolar depression who completed 6 weeks of acute treatment.

Methods

Patients completing 6 weeks of double‐blind placebo‐controlled treatment with either lurasidone monotherapy (one study) or adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate (two studies), were treated for 6 months with flexible doses of lurasidone, 20–120 mg/day, in an open‐label, uncontrolled extension study (N = 813; monotherapy, 38.9%; adjunctive therapy, 61.1%). Changes in safety parameters were calculated from double‐blind, acute‐phase baseline to month 6 of the extension phase, using a last observation carried forward (LOCF endpoint) analysis.

Results

Five hundred fifty‐nine of 817 (68.4%) patients completed the extension study. In the monotherapy and adjunctive therapy groups, 6.9 and 9.0%, respectively, discontinued due to an adverse event. For the monotherapy and adjunctive therapy groups, respectively, changes from double‐blind baseline to month 6 were +0.8 and +0.9 kg for weight (mean), 0.0 and +2.0 mg/dL for total cholesterol (median), +5.0 and +5.0 mg/dL for triglycerides (median), −1.0 and 0.0 mg/dL for glucose (median); −22.6 and −21.7 for Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; mean); whereas change from open‐label baseline to month 6 were +0.85 and +0.88 kg for weight (mean), and −6.9 and −6.5 for MADRS (mean).

Conclusions

Six months of treatment with open‐label lurasidone was safe and well tolerated with minimal effect on weight and metabolic parameters; continued improvement in depressive symptoms was observed.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, bipolar depression, lurasidone, antipsychotic agents, lithium, valproate, depressive disorder, major depression

INTRODUCTION

Bipolar I disorder is a chronic, recurrent illness with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 1%.1 The treatment of recurrent depressive episodes, which predominate over manic episodes in the majority of patients,2, 3 is an unmet need in the long‐term treatment of bipolar disorder. Antidepressant efficacy has not been demonstrated for standard antidepressants or typical antipsychotics, either as acute treatments for bipolar depression, or as maintenance therapy for the prevention of depression relapse.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 There is weak evidence for the maintenance efficacy of most mood stabilizers in the prevention of depressive relapse (notably lithium, valproate, carbamazepine),9 and stronger evidence suggesting that lamotrigine may be effective in delaying depressive episode recurrence.10

Among atypical antipsychotics, quetiapine monotherapy,11, 12 and olanzapine in combination with fluoxetine (OFC),13 have demonstrated efficacy in the acute treatment of bipolar depression, whereas aripiprazole monotherapy,14 and ziprasidone monotherapy15 and adjunctive therapy (with lithium or divalproex)16 were not significantly different from placebo in controlled acute trials. Quetiapine monotherapy17 and adjunctive therapy (with lithium or divalproex)18, 19, 20 demonstrated significant efficacy in preventing recurrence of both manic and depressive episodes in bipolar populations. Limited data suggest that OFC might be effective as a long‐term therapy for prevention of depressive relapse,21, 22 although weight gain and metabolic effects may limit the utility of this treatment.

Although treatment guidelines have commonly recommended maintenance therapy with lamotrigine or quetiapine as first‐line treatments in bipolar disorder patients at risk for depressive episode recurrence,4, 5, 6, 7, 8 there clearly is a need for additional options that are safe, well‐tolerated, and effective for the maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder patients at risk for depression recurrence.

Lurasidone has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute bipolar depression, both as monotherapy, and as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate. Three randomized, double‐blind, 6‐week trials have been completed, a monotherapy trial comparing two flexible‐fixed doses of lurasidone (20–60 mg/day; 80–120 mg/day),23 and two flexible dose trials of lurasidone (20–120 mg/day) administered adjunctively with lithium or valproate.24, 25 We report here the results of the 6‐month, open‐label, uncontrolled extension of the three 6‐week studies, designed to evaluate long‐term safety and tolerability of lurasidone in patients with bipolar depression. A secondary aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of lurasidone in maintaining improvement in depressive symptoms.

METHODS

This was a 6‐month, open‐label, uncontrolled extension study that enrolled patients who had recently completed one of three 6‐week, double‐blind trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of lurasidone compared to placebo for the treatment of bipolar I depression, either as monotherapy (one study; clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00868699)23 or as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate (two studies; clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT0086845224; and clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00868699).25 The study was conducted from June 2009 to February 2013 at 129 centers in 16 countries. The study protocol was approved by Independent Ethics Committees associated with each study center. Prior to entering the current extension study, an informed consent document was reviewed and signed by all patients. Study conduct was in accordance with Good Clinical Practices as required by the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines and in accordance with ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (as revised in 1983). The study was monitored by an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

PATIENTS AND STUDY DESIGN

Entry into the preceding acute treatment studies was limited to adult outpatients, ages 18–75 years (inclusive), with a DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis of bipolar I disorder with current major depressive episode. The duration of the depressive episode was required to be between 4 weeks and 12 months, with a Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)26 score ≥20 and a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)27 score ≤12. Patients with psychotic features were excluded; however, rapid cycling (four to seven episodes in the prior year) was permitted.

Patients were included in the current extension study if they were judged by the Investigator to be suitable for participation in a 6‐month open‐label study, able to comply with the protocol, not at imminent risk of suicide, or injury to self or others, and if their MADRS item‐10 score (suicidal thoughts) was rated as ≤3 (at open‐label baseline).

In order to maintain the blind in the preceding acute treatment trials, all patients who were enrolled in the current extension study were started at a dose of 60 mg/day for 1 week, regardless of their original double‐blind treatment assignment. Lurasidone was taken orally, once daily in the evening with a meal or within 30 minutes after eating, and adjusted weekly as clinically indicated within the dose range of 20–120 mg/day. Patients treated with lithium or valproate in each of the two acute adjunctive trials were continued on their mood stabilizer, with the recommendation to maintain serum concentrations, which were assessed at baseline and months 3 and 6, within the protocol‐defined therapeutic range for lithium (0.6–1.2 mEq/L) and valproate (50–125 μg/mL). However, mood stabilizer therapy could be discontinued at the discretion of the investigator during extension treatment. In addition, adjunctive treatment with a mood stabilizer could be initiated during extension treatment in patients who received monotherapy during the preceding 6‐week trial. Descriptive analyses were performed separately for the lurasidone monotherapy group and the lurasidone adjunctive therapy group, with group assignment based on which acute treatment study the patient originally participated in.

Patients were permitted to be treated concomitantly with benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium, divalproex, or lamotrigine), or antidepressants at the discretion of the Investigator. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors and antipsychotic medications (other than lurasidone) were prohibited.

SAFETY AND TOLERABILITY

The percentage and severity of treatment‐emergent adverse events were recorded. Movement disorders were assessed using the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS),28 the Simpson‐Angus Scale (SAS),29 and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).30 Additional safety evaluations included vital signs, laboratory tests, 12‐lead ECG, and physical examination. Treatment‐emergent mania was defined, a priori, as a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)27 score of ≥16 at any postbaseline visit, or an adverse event of mania or hypomania. Suicidal ideation and behavior were assessed using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C‐SSRS).31

EFFECTIVENESS

Secondary a priori assessments of treatment effectiveness were obtained at open‐label baseline, and at monthly intervals thereafter. Effectiveness outcomes were analyzed both for observed cases (OC; available patients at each study visit), and based on a last observation carried forward to endpoint analysis (LOCF endpoint). Effectiveness outcomes consisted of the Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),26 the Clinical Global Impression‐Bipolar Severity of depression (CGI‐BP‐S) scale,30 the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM‐A),32 the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS),33 and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form (Q‐LES‐Q‐SF).34

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

The primary safety population consisted of all patients who completed an acute‐phase trial, continued into this extension study, and received at least one dose of open‐label lurasidone. The primary safety analyses consisted of the percentage of treatment‐emergent adverse events, serious adverse events, and discontinuations due to adverse events. Oberved case analyses were calculated for change from double‐blind baseline for the following safety variables: body weight, proportion of patients with ≥7% weight change from baseline, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, vital signs, serum prolactin, electrocardiogram (ECG) parameters, movement disorders as assessed by the BARS, SAS, and AIMS scales, as well as results from the C‐SSRS, physical examination results, and standard laboratory tests, including chemistry, hematology (hemoglobin, hematocrit, white blood cells with differential, platelet count), and urinalysis.

Mean (SD) changes were reported from double‐blind acute study baseline, and from open‐label extension study baseline, for the MADRS total score, CGI‐BP‐S depression score, HAM‐A total score, YMRS total score, SDS total score, and Q‐LES‐Q‐SF score. For efficacy measures, change was reported for observed cases at monthly intervals, and for last observation carried forward at month 6 endpoint (LOCF‐endpoint). Treatment response was defined as achieving ≥50% reduction in MADRS total score from double‐blind baseline, and remission was defined as a MADRS total score ≤12. On a post‐hoc basis, depressive relapse was defined as a MADRS total score ≥20 for two consecutive assessments or discontinuation due to a depression‐related adverse event or due to insufficient clinical response (based on Vieta et al.).35 Shift analyses (observed case) were reported for the percentage of patients exhibiting a change, from open‐label baseline to month 6, in their depression status among one of the four outcome categories: nonresponder, responder, remitter, and relapse. An additional post hoc analysis was performed to evaluate clinical worsening of depression, using a ≥5‐point increase in the MADRS as the criterion, and clinical worsening of manic symptoms, using a ≥5‐point increase in the YMRS as the criterion.36, 37, 38

RESULTS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS AND PATIENT DISPOSITION

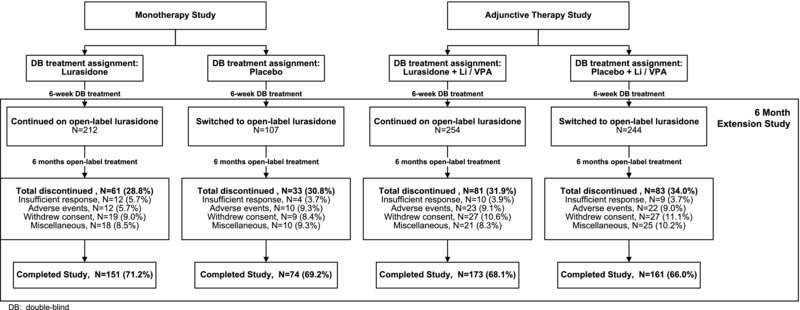

A combined total of 941 patients completed the three double‐blind, 6‐week, acute‐phase studies and were potentially eligible for entry in the current open‐label extension study. Of this total, 817 patients (86.8%) provided informed consent and entered the extension study, including 319 patients who completed the double‐blind acute monotherapy study (lurasidone, N = 212; placebo, N = 107), and 498 patients who completed the two double‐blind acute adjunctive therapy studies (lurasidone, N = 254; placebo, N = 244). The safety population consisted of 316 patients from the monotherapy study (two patients in the lurasidone continuation group, and one in the placebo‐to‐lurasidone switch group discontinued before receiving extension study medication); and 497 patients from the adjunctive therapy studies (one patient in the placebo‐to‐lurasidone switch group discontinued before receiving extension study medication). Among acute monotherapy patients, only (n = 7) 2.2% newly initiated lithium or valproate during the extension study; one adjunctive study patient permanently discontinued mood stabilizer therapy during the extension study.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar for patients who completed the acute monotherapy and adjunctive therapy studies, respectively (Table 1). Five hundred fifty‐nine patients (68.4%) completed the extension study. The proportion of extension study completers was similar for each acute study treatment group (monotherapy: 71.2% in the lurasidone continuation group, and 69.2% in the placebo‐to‐lurasidone switch group; adjunctive therapy: 68.1% in the lurasidone continuation group; 66.0% in the placebo‐to‐lurasidone switch group; Fig. 1). The proportion who discontinued due to an adverse event was less than 10% in each acute study treatment group (monotherapy: 5.7% in the lurasidone continuation group, and 9.3% in the placebo‐to‐lurasidone switch group; adjunctive therapy: 9.1% in the lurasidone continuation group; 9.0% in the placebo‐to‐lurasidone switch group; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of acute study completers who continued in the extension study (safety population)

| Lurasidone monotherapy (N = 316) | Lurasidone adjunctive therapy (N = 497) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % |

| Female | 176 | 55.7 | 251 | 50.5 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 215 | 68.0 | 319 | 64.2 |

| Black/African‐American | 39 | 12.3 | 55 | 11.1 |

| Asian | 39 | 12.3 | 96 | 19.3 |

| Other | 23 | 7.3 | 27 | 5.4 |

| History of rapid cycling (≥4 episodes in past 12 months) | 16 | 5.0 | 40 | 8.0 |

| Adjunctive mood stabilizer, n (%)a | ||||

| Lithium | 6 | 1.9 | 196 | 39.4 |

| Valproateb | 1 | 0.3 | 301 | 60.6 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 42.0 | 12.6 | 43.1 | 11.7 |

| Age of onset of diagnosis, years | 27.7 | 11.4 | 29.3 | 11.7 |

| Duration of current episode, weeks | 11.3 | 7.9 | 13.2 | 9.7 |

| Baseline scores | ||||

| MADRS | ||||

| Double‐blind baseline | 30.1 | 5.0 | 30.0 | 5.0 |

| Extension baseline | 14.8 | 9.4 | 15.6 | 10.4 |

| CGI‐BP‐severity | ||||

| Double‐blind baseline | 4.5 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 0.6 |

| Extension baseline | 2.8 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 1.3 |

| HAM‐A | ||||

| Double‐blind baseline | 16.1 | 6.2 | 15.7 | 6.0 |

| Extension baseline | 8.4 | 6.4 | 8.5 | 6.3 |

| YMRS | ||||

| Double‐blind baseline | 4.1 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| Extension baseline | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.7 |

MADRS, Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; CGI‐BP‐S, Clinical Global Impression Bipolar Version Severity of Illness depression score; HAM‐A, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Any time during the study; note that patients treated with lithium or valproate in one of the two acute adjunctive trials were continued on their mood stabilizer; however, mood stabilizer therapy could be discontinued at the discretion of the investigator; or treatment with a mood stabilizer could be initiated during extension treatment in patients who received monotherapy during the acute trial.

Valproate treatment included: ergynel chrono, valproic acid, and valpromide.

4 patients provided informed consent and entered the open‐label extension study, but never received study medication, and so were not included in the safety population.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

The mean (SD) daily dose of lurasidone during the study was 64.1 (14.4) mg, and was similar in the monotherapy and adjunctive therapy groups. The modal daily dose of lurasidone was 20 mg for 4.2% of patients, 40 mg for 7.4% of patients, 60 mg for 61.5% of patients, 80 mg for 17.6% of patients, 100 mg for 6.3% of patients, and 120 mg for 3.1% of patients. Among patients entering the open‐label extension study from the acute adjunctive therapy studies, 39.4% continued treatment with lithium and 60.6% were treated with valproate (Table 1).

Among adjunctive therapy patients, the mean dose of lithium was maintained in the range of 905–958 mg/day throughout the 6 months of extension study treatment; and the mean dose of valproate was maintained in the range of 1026–1107 mg/day. Mean serum lithium concentrations ranged from 0.61 to 0.70 mEq/L, and mean serum valproate concentrations ranged from 66.3 to 69.3 μg/mL.

SAFETY

For both the monotherapy and adjunctive treatment groups combined, treatment‐emergent adverse events reported by the greatest proportion of patients consisted of Parkinsonism (10.7%; a combined term consisting of bradykinesia, cogwheel rigidity, drooling, hypokinesia, muscle rigidity, Parkinsonism, psychomotor retardation, and tremor), akathisia (8.1%), somnolence (8.0%; a combined term consisting of hypersomnia, sedation, and somnolence), headache (7.7%), nausea (7.6%), insomnia (6.4%), and anxiety (5.8%). The proportion of patients reporting Parkinsonism, akathisia, somnolence, and anxiety (by 2.3 to 7.7%) and to a marginal extent insomnia (0.2%) was higher for lurasidone in the adjunctive therapy group compared with the monotherapy group (Table 2A); there was no consistent trend observed for other adverse events.

Table 2.

Tolerability and safety parameters of acute study completers who continued in the extension study

| Lurasidone monotherapy | Lurasidone adjunctive therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUR to LUR | PBO to LUR | LUR to LUR | PBO to LUR | |

| (N = 210) | (N = 106) | (N = 254) | (N = 243) | |

| A. Treatment‐emergent adverse events (percentage ≥5%; safety population) | ||||

| At least one event | 63.8% | 58.5% | 63.8% | 70.4% |

| Parkinsonisma | 4.8% | 8.5% | 14.2% | 13.2% |

| Headache | 13.3% | 6.6% | 5.5% | 5.8% |

| Somnolencea | 4.3% | 6.6% | 9.1% | 10.7% |

| Nausea | 7.6% | 6.6% | 5.5% | 10.3% |

| Akathisia | 5.7% | 6.6% | 8.7% | 10.3% |

| Insomnia | 5.7% | 7.5% | 7.1% | 5.8% |

| Nasopharyngitis | 6.7% | 6.6% | 3.5% | 3.7% |

| Vomiting | 3.3% | 5.7% | 2.8% | 5.8% |

| Anxiety | 5.7% | 1.9% | 6.7% | 6.6% |

| Depression | 2.9% | 1.9% | 4.7% | 7.0% |

| B. Change from double‐blind baseline to month 6 in weight, BMI, and waist circumference (safety population; OC Analysis) | ||||

| Weight | ||||

| Mean change, kg | +0.6 | +1.4 | +1.1 | +0.6 |

| ≥7% increase | 5.6% | 13.0% | 13.7% | 16.1% |

| ≥7% decrease | 4.0% | 1.9% | 5.3% | 5.1% |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean change | +0.2 | +0.5 | +0.4 | +0.2 |

| Waist circumference, cm, | ||||

| mean change | 0.0 | +0.5 | +1.3 | +0.6 |

| C. Median change from double‐blind baseline to month 6 in laboratory parameters (safety population; OC analysis) | ||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.0 | −1.0 | +1.0 | +6.0 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.5 | +4.0 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.0 | −3.0 | −1.0 | 0.0 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | +6.0 | +5.0 | +5.0 | +5.0 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 0.0 | −4.0 | 0.0 | −1.0 |

| HbA1c, % | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Insulin, mU/L | +0.5 | +0.2 | +1.7 | +0.4 |

| Prolactin, ng/mL | +1.4 | +1.0 | +1.3 | +1.7 |

| Prolactin, males | +1.2 | +0.8 | +0.5 | +1.3 |

| Prolactin, females | +1.8 | +1.7 | +2.7 | +2.3 |

LUR, lurasidone; PBO, placebo; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein, OC, observed case.

LUR to LUR indicates acute treatment with lurasidone, followed by continued treatment with lurasidone during the 6‐month extension study; PBO to LUR indicates acute treatment with placebo, then switched to lurasidone during the 6‐month extension study.

Both confirmed and nonconfirmed fasting values are presented for metabolic parameters.

Parkinsonism = bradykinesia, cogwheel rigidity, drooling, hypokinesia, muscle rigidity, Parkinsonism, psychomotor retardation, and tremor.

Somnolence = sedation, hypersomnia, somnolence.

Both for patients treated with lurasidone as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy, respectively, the majority of adverse events were classified as either mild (44.9 and 52.3%) or moderate (29.1 and 37.2%) in severity. For the combined treatment groups, the three individual TEAEs most frequently rated as “severe” were akathisia (1.4%), depression (1.1%), and insomnia (0.5%). Among patients discontinuing due to a treatment‐emergent adverse event (TEAE), akathisia (1.1%) was the most frequently cited TEAE; other TEAEs were cited with a percentage <0.5%.

In the monotherapy group, the proportion reporting at least one treatment‐emergent adverse event was somewhat lower for patients switching from acute study placebo to lurasidone compared to patients continuing on lurasidone (58.5 vs. 63.8%); in the adjunctive therapy group, the proportion was higher (70.4 vs. 63.8%; Table 2A).

During the extension study, serious treatment‐emergent adverse events were reported by 3.0% of patients, including 2.2% in the monotherapy group, and 3.4% in the adjunctive therapy group. The following serious adverse events were reported in the overall safety population: worsening depression (n = 8; 1.0%), suicidal ideation (n = 3; 0.4%), bone fractures (n = 3; 0.4%), suicide attempt, (n = 2; 0.2%), mania (n = 2; 0.2%), and one for each of the following events: pancreatitis, appendicitis, a hypersensitivity reaction, skin neoplasm, and lumbar spinal stenosis. In addition, two deaths were reported during the study; each was judged by the investigator to be unrelated to study medication: a motor vehicle accident death (in a patient who completed 6 weeks of double‐blind adjunctive therapy with lurasidone 60 mg, and 11 days of open‐label adjunctive therapy with lurasidone 60 mg), and a suicide by hanging (occurred 7 days after taking a single extension study dose of lurasidone in a patient who previously received placebo in the acute monotherapy study). Based on C‐SSRS results, treatment with lurasidone was associated with emergence of suicidal ideation or behavior at some point during the 6‐month study in 5.0% of patients in the monotherapy group and 8.8% of patients in the adjunctive group.

Treatment‐emergent mania, as prespecified in the protocol, occurred in 1.3% of patients in the monotherapy group, and in 3.8% of patients in the adjunctive group. There was a small decrease in mean YMRS total score from open‐label baseline to extension study month 6, for the lurasidone to lurasidone and placebo to lurasidone groups, respectively, among patients taking monotherapy (−0.6, −1.1) and patients taking adjunctive therapy (−0.5, −0.5).

The proportion of patients who received treatment with anticholinergic medication for acute extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) was 4.4% in the monotherapy group, and 9.5% in the adjunctive group. Both monotherapy and adjunctive treatment with lurasidone was associated with negligible mean changes in the BARS global score (≤0.1), and SAS 10‐item mean score (≤0.04; at LOCF endpoint). Categorical worsening in the AIMS global score occurred at low rates in the monotherapy (1.8%) and adjunctive therapy (1.2%) groups. The proportion of patients treated with as‐needed doses of anxiolytics was 7.0% in the monotherapy group and 15.7% in the adjunctive therapy group. The proportion of patients treated with concomitant antidepressants was 5.4% in the monotherapy group and 7.8% in the adjunctive therapy group.

Mean changes in weight from double‐blind baseline at 6 months (observed cases) were modest and similar for the monotherapy and adjunctive therapy groups (0.85 and 0.88 kg, respectively; see Table 2B, which shows results by original double‐blind treatment assignment. The proportion of patients with ≥7% increase in weight at month 6 was lower in the monotherapy group compared with the adjunctive therapy group (8.2 vs. 14.9%, respectively; Table 2B). Mean changes in BMI at month 6 were low (+0.3) in both the monotherapy and adjunctive therapy groups (Table 2B).

Small median changes from double‐blind baseline were observed at month 6 for both the monotherapy and adjunctive groups, respectively, in total cholesterol (0.0 and +2.0 mg/dL), triglycerides (+5.0 and +5.0 mg/dL), and glucose (−1.0 and 0.0 mg/dL; Table 2C; observed cases). There were no changes in HbA1c greater than +2.4% in either the monotherapy or adjunctive therapy groups. Modest median increases in prolactin in the range of 0.5–2.7 ng/mL were observed for both the monotherapy and adjunctive groups (Table 2C).

No clinically significant changes were observed for heart rate, orthostatic blood pressure changes (systolic or diastolic), respiratory rate, or body temperature. No patient in either the monotherapy or adjunctive groups had a QTcB value >500 ms after open‐label baseline. One patient (0.4%) in the monotherapy group and two patients (0.5%) in the adjunctive therapy group had an increase from double‐blind baseline in QTcB value ≥60 ms.

EFFECTIVENESS

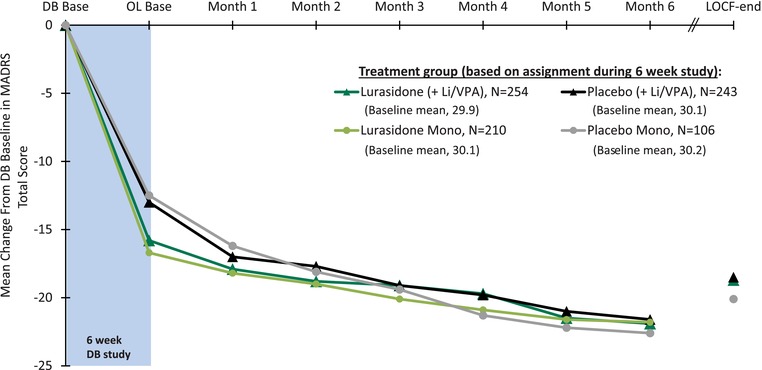

During 6 weeks of initial double‐blind treatment, improvement was observed in both the monotherapy and adjunctive therapy groups (Figure 2). Six months of open‐label treatment with lurasidone was associated with additional improvement in the MADRS for the monotherapy group that continued to receive lurasidone (−5.0; OC analysis) and for the monotherapy group that was switched from placebo to lurasidone (−10.8; OC; Table 3A; Figure 2); and additional improvement in the MADRS was also observed for the adjunctive therapy group that continued to receive lurasidone (−4.9; OC) and for the monotherapy group that was switched from placebo to lurasidone (−8.2; OC; Table 3B; Figure 2). A similar and consistent pattern of improvement from open‐label baseline to month 6 (OC analysis) was observed for the secondary outcome measures (CGI‐BP‐S, HAM‐A, Q‐LES‐Q, SDS) as summarized in Table 3A and B. Table 3A and B also summarizes the results of the LOCF‐endpoint analysis for the MADRS, and for the secondary outcome measures.

Figure 2.

Mean change from baseline in MADRS total score for acute study patients who continued in the extension study. OC scores are shown for each study visit through month 6. OC, observed case; LOCF, last observation carried forward; DB, double‐blind.

Table 3.

Mean changes in efficacy measures from double‐blind (DB) and open‐label (OL) baseline: acute study completers who continued in the extension study

| Observed case analysisa mean (SD) change | LOCF‐endpoint analysis mean (SD) change | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N OC | N LOCF | DB baseline mean (SD) | DB baseline to month 6 | OL baseline to month 6 | DB baseline to month 6 | OL baseline to month 6 | |

| A. Lurasidone monotherapy (based on acute study status) | |||||||

| MADRS total | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 153 | 202 | 30.1 (4.8) | −21.8 (7.5) | −5.0 (8.6) | −20.1 (9.5) | −3.3 (9.7) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 74 | 99 | 30.2 (5.2) | −22.6 (6.0) | −10.8 (8.9) | −20.1 (9.2) | −7.6 (10.9) |

| CGI‐BP‐Severity | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 153 | 202 | 4.5 (0.6) | −2.5 (1.0) | −0.7 (1.0) | −2.4 (1.2) | −0.5 (1.2) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 74 | 99 | 4.4 (0.6) | −2.6 (1.0) | −1.3 (1.2) | −2.3 (1.2) | −1.0 (1.3) |

| HAM‐A total | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 158 | 186 | 15.7 (6.0) | −10.3 (5.6) | −2.1 (5.2) | −9.8 (6.0) | −1.6 (5.4) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 77 | 91 | 16.7 (6.7) | −11.2 (5.9) | −4.3 (5.3) | −10.0 (6.8) | −3.4 (6.1) |

| Q‐LES‐Q‐SF | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 151 | 180 | 34.0 (13.3) | +29.9 (15.1) | +6.6 (15.6) | +29.0 (16.6) | +5.7 (16.5) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 75 | 89 | 34.3 (14.3) | +29.7 (15.2) | +15.5 (19.5) | +28.1 (16.4) | +13.6 (19.3) |

| SDS total | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 122 | 149 | 19.8 (5.0) | −13.8 (7.4) | −3.4 (6.5) | −13.4 (7.4) | −3.1 (6.5) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 64 | 79 | 20.3 (4.5) | −14.4 (6.0) | −6.2 (7.0) | −13.7 (6.9) | −6.0 (7.8) |

| B. Lurasidone adjunctive therapy (based on acute‐study status) | |||||||

| MADRS total | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 173 | 243 | 29.9 (5.1) | −21.9 (9.0) | −4.9 (9.8) | − 18.7 (10.5) | −3.0 (10.7) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 161 | 234 | 30.1 (4.9) | −21.6 (8.1) | −8.2 (8.9) | −18.5 (10.5) | −5.5 (10.7) |

| CGI‐BP severity | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 173 | 243 | 4.5 (0.7) | −2.6 (1.2) | −0.7 (1.2) | −2.2 (1.4) | −0.4 (1.4) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 161 | 234 | 4.5 (0.6) | −2.5 (1.2) | −1.1 (1.2) | −2.1 (1.3) | −0.7 (1.4) |

| HAM‐A total | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 187 | 225 | 15.6 (5.9) | −10.3 (7.8) | −1.3 (6.7) | −9.4 (7.8) | −1.0 (6.8) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 173 | 219 | 15.8 (6.2) | −9.9 (7.1) | −3.5 (6.0) | −8.6 (7.8) | −2.4 (6.6) |

| Q‐LES‐Q‐SF | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 179 | 217 | 34.5 (12.8) | +28.0 (18.3) | +5.3 (18.0) | +25.6 (19.2) | +3.3 (18.4) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 168 | 210 | 34.9 (11.5) | +25.8 (19.1) | +9.8 (16.5) | +23.3 (19.5) | +7.8 (17.7) |

| SDS total | |||||||

| Lurasidone to lurasidone | 155 | 187 | 19.4 (5.7) | −13.2 (7.9) | −2.6 (7.8) | −11.8 (8.6) | − 2.2 (7.6) |

| Placebo to lurasidone | 128 | 179 | 19.4 (5.0) | −12.7 (7.9) | −4.3 (8.0) | −11.2 (8.8) | −3.0 (8.9) |

OC, observed case analysis; LOCF, last observation carried forward.

Lurasidone to lurasidone indicates acute treatment with lurasidone, then continued on lurasidone during the extension study; placebo to lurasidone indicates acute treatment with placebo, then switched to lurasidone during the extension study.

analysis of month 6 completers.

A post hoc responder and remitter analysis was performed to evaluate the outcome of 6 months of extension treatment in the group of patients who received lurasidone in the acute, 6‐week, double‐blind trials. At baseline of the extension study the proportion of patients who met a priori responder and remitter criteria, respectively, was similar in the monotherapy group (56.3 and 44.9%) and in the adjunctive therapy group (51.1 and 45.7%). Following 6 months of continued treatment with lurasidone in the extension study, the proportion of responders and remitters, respectively, increased both in the monotherapy group (90.3 and 83.7%) and in the adjunctive therapy group (83.2 and 77.2%).

In the group of patients who met a priori responder criteria at extension study baseline, the majority continued to be responders at 6 months in both the monotherapy group (96.1%) and the adjunctive therapy group (91.4%). Among patients who met a priori remitter criteria at extension study baseline, the vast majority continued to be remitters at 6 months in both the monotherapy group (95.1%) and the adjunctive therapy group (91.0%). In addition, among responders at extension study baseline (who did not meet remitter criteria), 79.2% in the monotherapy group and 66.7% in the adjunctive therapy group showed sufficient improvement at 6 months to meet remitter criteria.

Among extension study baseline responders, 10.2% met post hoc criteria for depression relapse during 6 months of treatment in the monotherapy group, with a similar 10.2% meeting relapse criteria in the adjunctive therapy group. Among patients who were nonresponders at extension study baseline, the majority had converted to responder status at the end of 6 months in both the monotherapy group (83.0%) and the adjunctive therapy group (73.0%).

In order to assess whether clinical worsening occurred that was below relapse criteria thresholds, supplemental analyses were performed utilizing a 5‐point increase in the MADRS total score as the criterion for emergence of depressive symptoms, and a 5‐point increase in the YMRS total score as the criterion for emergence of hypomanic symptoms. For the group of patients (monotherapy and adjunctive therapy, combined) who met responder criteria at open‐label baseline, 17.9% experienced a ≥5‐point increase in the MADRS during 6 months of extension treatment. Among responders in the monotherapy group, 12.4% experienced a 5‐point increase in MADRS but did not go on to relapse, whereas 3.9% met relapse criteria at LOCF endpoint. Among responders in the adjunctive therapy group, 10.5% experienced a 5‐point increase in MADRS but did not go on to relapse, whereas 8.6% met relapse criteria.

An analysis of treatment‐emergent manic symptoms in the total patient sample found that 37 patients (4.8%) experienced an increase in YMRS total score of ≥5 points, of whom 12 met criteria for mania at LOCF endpoint. The proportion of patients with an increase in YMRS total score of ≥5 points was slightly higher in the adjunctive therapy versus monotherapy group (6.3 vs. 2.3%).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to evaluate the long‐term effects of lurasidone in the treatment of bipolar disorder. The results of this open‐label, uncontrolled extension study demonstrated the safety and tolerability of once‐daily flexible doses of lurasidone, in the range of 20–120 mg, during 6 months of treatment for bipolar disorder, both as monotherapy and adjunctive with lithium or valproate. These results are consistent with previous findings from long‐term trials of lurasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia.39, 40, 41, 42

Completion rates during 6 months of treatment with lurasidone monotherapy (70.5%) and adjunctive therapy (67.1%) compare favorably to those reported during 6 months of open‐label extension treatment with OFC (56%), and with olanzapine monotherapy (66%).21 The percentage of individual treatment‐emergent adverse events was relatively low (<10%) and similar for lurasidone when administered as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy. The majority of adverse events were rated as being either mild or moderate in severity. Patients who switched from acute‐phase placebo to lurasidone (during the extension phase) did not experience a notably higher percentage of adverse events when compared with patients who continued on lurasidone. The frequency of discontinuation due to an adverse event was relatively low, especially for monotherapy (6.9%); the top three events resulting in discontinuation were akathisia (1.1%), depression (0.7%), and anxiety (0.5%).

Lurasidone was not associated with clinically significant findings on laboratory, ECG, or vital sign parameters. Minimal effects were observed on weight, lipids, and measures of glycemic control; and no meaningful differences were observed for lurasidone when administered as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy. There is an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease in the bipolar disorder population.43, 44 The relatively benign cardiometabolic risk profile of lurasidone may make it a potentially safer treatment option in this vulnerable clinical population.

The occurrence of protocol‐specified treatment‐emergent mania was relatively low among patients treated with adjunctive lurasidone (3.8%) and lurasidone monotherapy (1.3%). Because no parallel placebo or active control group was available, the drug‐specific effect of lurasidone on the percentage of mania is unclear. However, the current results appear to be comparable to the percentage of mania (<5%) reported at 6 months in two long‐term trials of quetiapine combined with lithium or valproate in bipolar disorder.20

Throughout the 6‐month course of treatment, mean depressive symptom scores continued to show improvement from open‐label baseline. As expected, patients who were switched from double‐blind placebo to lurasidone in the extension study showed greater additional improvement at 6 months when compared with patients who continued on lurasidone in the extension study. As a result, MADRS scores were similar at month 6 regardless of prior treatment assignment during the double‐blind 6‐week acute study. Continued improvement was also observed in CGI‐BP‐S depression scores, as well as in patient‐rated measures of quality of life and functioning (SDS and Q‐LES‐Q). Greater improvement was also observed for these measures in patients who were switched from acute‐phase placebo to lurasidone, compared to patients who continued acute‐phase lurasidone in the extension study.

The majority of patients who did not meet responder criteria at the start of the extension study improved and became responders by 6 months in both the monotherapy group (83%) and in the adjunctive therapy group (73%), whereas the vast majority (more than 90%) of patients who met responder criteria at baseline of the extension study continued as responders at month 6. Among extension baseline responders, a slightly higher proportion met remission criteria at month 6 in the monotherapy compared with the adjunctive therapy group (92.1 vs. 88.2%). This may reflect differences in the clinical characteristics of patients who were being treated with a mood stabilizer, and thus were eligible for recruitment into an acute adjunctive therapy trial.

In a post hoc analysis, depression relapse rates were low during 6 months of treatment with lurasidone (10.2% in both the monotherapy and adjunctive therapy groups. These rates of relapse are lower than depression relapse rates reported for patients with bipolar depression during 6 months of open‐label treatment with OFC (23.7%)21; or depression relapse rates at 6 months for patients treated with lamotrigine (approximately 35%) and lithium (approximately 43%).45 However, differences in relapse criteria prevent direct comparison of outcomes. For example, in the lamotrigine/lithium trial, additional treatment intervention was the a priori criterion for relapse (e.g., use of antidepressants, electroconvulsive therapy).

The mean maintenance dose of lurasidone used in the current study (64.1 mg/day) was similar to the mean dose used in an acute adjunctive therapy study (66.3 mg/day).24 A modal lurasidone daily dose of 60 mg was taken by 61.5% of patients, regardless of whether they were receiving monotherapy or adjunctive therapy. In the current study, serum lithium and valproate concentrations were similar to concentrations obtained in the acute adjunctive therapy studies, and were maintained through 6 months of study treatment.

LIMITATIONS

The primary limitation of the current study was its open‐label, uncontrolled design and lack of an active comparator or placebo control group. Although the percentage of adverse effects in the current study was low, precise determination of drug‐specific rates of adverse events and laboratory abnormalities was not possible due to the absence of a control group. In addition, patients who received lurasidone in the acute treatment study may represent a more lurasidone‐tolerable group. The absence of (random assignment to) placebo in the current study precludes making inferences about relapse prevention effectiveness associated with maintenance lurasidone treatment. Additional limitations include the sample size and the 6‐month duration of the trial, which may be insufficient to adequately assess rare or very gradually developing safety issues. Future controlled trials are warranted to confirm the effectiveness and safety of long‐term treatment with lurasidone in this population.

CONCLUSIONS

Lurasidone has been shown to be safe and efficacious in the short‐term treatment of bipolar depression. In the current study, the first to evaluate the effects of long‐term treatment in this patient population, once‐daily doses of lurasidone, in the range of 20–120 mg for up to 6 months, appeared to be safe and well‐tolerated with minimal effects on weight and metabolic parameters. Safety outcomes were not different for monotherapy compared with adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate. Treatment with lurasidone was associated with sustained improvement in depressive symptoms, and in patient‐rated measures of quality of life and functioning.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Ketter has engaged in collaborative research with, or received consulting or speaking fees, from Abbott, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Avanir, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sunovion, and Teva; Dr. Ketter's spouse is an employee of, and holds stock in, Janssen Pharmaceuticals

Drs. Sarma, Silva, Kroger, Cucchiaro, and Loebel are full‐time employees of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Edward Schweizer of Paladin Consulting Group who provided editorial and medical writing assistance for this manuscript, which was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Sunovion was involved in the design, collection, and analysis of the data. Interpretation of the results, and the decision to submit this manuscript for publication was made by the authors.

The authors would also like to thank the participants of this study and the members of the lurasidone bipolar disorder study group: Canada: Drs. R. Bergeron, P. Chokka, P. Latimer, V. Tourjman; Czech Republic: Drs. J. Bilik, J. Drahozal, E. Herman, J. Horacek, J. Hronek, M. Klabusayova, J. Lestina, S. Papezova, Z. Solle; Columbia: Drs. L. Agudelo, A. Arrieta, H. Bobadilla, R.N. Cordoba; France: Drs. M. Abbar, B. Jomard, M. Zins Ritter; Germany: Drs. W. Kissling, J. Thomsen; India: Drs. V. Barhale, P. Behere, S. Bhat, B. Buch, M. Chudgar, D. Dhavale, H. Gandhi, M. Gowda, V. Indla, A. Jagadish, R. Mahendru, S. Mittal, V. Mrugesh, U. Nagapurkar, A. Nischal, R. Satapathy, S. Shah, A. Tambi, P. S. Thatikonda, J. K. Trivedi, R. Yadav; Japan: Drs. T. Enomoto, H. Kikuyama, A. Matsuzaki, Y. Saeki, H. Tanaka, Y. Tsutsumi; Lithuania: Drs. D. Deltuviene, R. Jasaite, V. Matoniene, L. Siaudvytyte, A. Stakioniene; Peru: Drs. W. Aguilar, M. Lecussan, B. Macciotta; Poland: Drs. P. Bogacki, J. Janczewski, A. Kokozka; Romania: Drs. G. M. Badescu, D. Cozman, M. Ladea, G. C. Marinescu, G. Oros, D. Vasile; Russia: Drs. M. Ivanov, V. Kozlovsky, V. Tochilov, V. Vid; Slovakia: Drs. V. Garaj, J. Greskova, M. Hastova, Z. Janikova, R. Korba, P. Molčan, A. Shinwari, L. Vavrusova; South Africa: Drs. K. Botha, G. Jordaan, L. Nel, J. Schronen, R. Verster; Ukraine: Drs. V. Abramov, V. Bitenskyy, O. Chulkov, V. Demchenko, N. Maruta, S. Moroz, P. Palamarchuk, S. Rymsha, A. Skrypnikov, I. Spirina, O. Venger, V. Verbenko, K. Zakal; USA: Drs. S. Aaronson, C. Adler, M. Alam, M. Allen, D. Almahana, R. Anderson, V. Arnold, S. Atkinson, A. Attalla, J. Aukstuolis, M. Banov, P. Bhatia, J. Booker, R. Brenner, B. Burtner, J. Calabrese, L. Chung, A. Cutler, G. Dempsey, M. Downing, B. D'Souza, A. Fan, D. Franklin, D. Garcia, E. Gfeller, L. Ginsberg, A. Goenjian, S. Goldstein, T. Grugle, L. Harper, H. Hassman, J. Heussy, R. Hidalgo, T. Ketter, R. Knapp, J. Kunovac, J. Kwentus, R. Manning, V. Mehra, J. Miller, S. Mohaupt, E. Norris, N. Patel M. Plopper, S. Potkin, N. Rosenthal, A. Sedillo, R. Segraves, A. Sfera, W. Smith, K. Sokolski, J. Steiert, T. Tran‐Johnson, N. Vatakis, D. Walling, R. Weisler, K. Yadalam, M. Zarzar.

Contract grant sponsor: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

This article was originally published on 26 February 2016. Subsequently, minor text corrections were made and the corrected article was published on 31 March 2016.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 3 August 2016 after original online publication.

REFERENCES

- 1. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12‐month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long‐term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kupka RW, Altshuler LL, Nolen WA, et al. Three times more days depressed than manic or hypomanic in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kasper S, Calabrese JR, Johnson G, et al. International Consensus Group on the evidence‐based pharmacological treatment of bipolar I and II depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:1632–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goodwin GM, Consensus Group of the British Association for Psychopharmacology . Evidence‐based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition—recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2009;23:346–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin G, et al. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of bipolar depression. World J Biol Psychiatry 2010;11:81–109.20148751 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update. Bipolar Disord 2013;15:1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. NICE Clinical Guidelines . Bipolar disorder. The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London, UK, 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185. (accessed February 21, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vieta E, M Valentí. Pharmacological management of bipolar depression: acute treatment, maintenance, and prophylaxis. CNS Drugs 2013;27:515–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldsmith DR, Wagstaff AJ, Ibbotson T, Perry CM. Lamotrigine: a review of its use in bipolar disorder. Drugs 2003;63:2029–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calabrese JR, Keck PE, Jr. , Macfadden W, et al. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1351–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thase ME, Macfadden W, Weisler RH, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar I and II depression: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study (the BOLDER II study). J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26:600–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine‐fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1079–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thase ME, Jonas A, Khan A, et al. Aripiprazole monotherapy in nonpsychotic bipolar I depression: results of 2 randomized, placebo‐controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;28:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lombardo I, Sachs G, Kolluri S, et al. Two 6‐week, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled studies of ziprasidone in outpatients with bipolar I depression: did baseline characteristics impact trial outcome? J Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;32:470–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sachs GS., Ice KS, Chappell PB P. B., et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive oral ziprasidone for acute treatment of depression in patients with bipolar I disorder: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:1413–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weisler RH, Montgomery SA, Earley WR, et al. Efficacy of extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy in patients with major depressive disorder: a pooled analysis of two 6‐week, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;27:27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vieta E, Suppes T, Eggens I, et al. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex for maintenance of patients with bipolar I disorder (international trial 126). J Affect Disord 2008;109:251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Suppes T, Vieta E, Liu S, et al. Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder: results from a north american study of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:476–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suppes T, Vieta E, Gustafsson U, Ekholm B. Maintenance treatment with quetiapine when combined with either lithium or divalproex in bipolar I disorder: analysis of two large randomized, placebo‐controlled trials. Depress Anxiety 2013;30:1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Corya SA, Perlis RH, Keck PE, Jr. , et al. A 24‐week open‐label extension study of olanzapine‐fluoxetine combination and olanzapine monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown E, Dunner DL, McElroy SL, et al. Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination vs. lamotrigine in the 6‐month treatment of bipolar I depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2009;12:773–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suppes T, Silva R, Kroger H, et al. Lurasidone Adjunctive Therapy With Lithium or Valproate for the Treatment Of Bipolar I Depression: A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Study. Poster presentations at the annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, December 8–12, 2013, Hollywood, FL 2013.

- 26. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979;132:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978;133:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug‐induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989;154:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simpson GN, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatrica Scand 1970;212(Suppl 44):11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) In: Guy W, editor. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976:534–537. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sheehan DV. The Anxiety Disease. New York: Bantam Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vieta E, Suppes T, Ekholm B, et al. Long‐term efficacy of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex on mixed symptoms in bipolar I disorder. J Affect Disord 2012;142:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Müller MJ, Himmerich H, Kienzle B, Szegedi A. Differentiating moderate and severe depression using the Montgomery‐Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS). J Affect Disord 2003;77:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kearns NP, Cruickshank CA, McGuigan KJ, et al. A comparison of depression rating scales. Br J Psychiatry 1982;141:45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lukasiewicz M, Gerard S, Besnard A, et al. Young Mania Rating Scale: how to interpret the numbers? Determination of a severity threshold and of the minimal clinically significant difference in the EMBLEM cohort. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2013;22:46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Citrome L, Cucchiaro J, Sarma K, et al. Long‐term safety and tolerability of lurasidone in schizophrenia: a 12‐month, double‐blind, active‐controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;27:165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Xu J, et al. Effectiveness of lurasidone vs. quetiapine XR for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a 12‐month, double‐blind, noninferiority study. Schizophr Res 2013;147:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stahl SM, Cucchiaro J, Simonelli D, et al. Effectiveness of lurasidone for patients with schizophrenia following 6 weeks of acute treatment with lurasidone, olanzapine, or placebo: a 6‐month, open‐label, extension study. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Citrome L, Weiden PJ, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of lurasidone in schizophrenia or schizoaffective patients switched from other antipsychotics: a 6‐month, open‐label, extension study. CNS Spectr 2014:330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goldstein BI, Fagiolini A, Houck P, Kupfer DJ. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension among adults with bipolar I disorder in the United States. Bipolar Disord 2009;11:657–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vancampfort D, Vansteelandt K, Correll CU, et al. Metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in bipolar disorder: a meta‐analysis of prevalence rates and moderators. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs G, et al. A placebo‐controlled 18‐month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently depressed patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1013–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]