Abstract

The Zn(II) ion has been linked to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) due to its ability to modulate the aggregating properties of the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide, where Aβ aggregation is a central event in the etiology of the disease. Delineating Zn(II) binding properties to Aβ is thus a prerequisite to better grasp its potential role in AD. Because of (i) the flexibility of the Aβ peptide, (ii) the multiplicity of anchoring sites, and (iii) the silent nature of the Zn(II) ion in most classical spectroscopies, this is a difficult task. To overcome these difficulties, we have investigated the impact of peptide alterations (mutations, N-terminal acetylation) on the Zn(Aβ) X-ray absorption spectroscopy fingerprint and on the Zn(II)-induced modifications of the Aβ peptides’ NMR signatures. We propose a tetrahedrally bound Zn(II) ion, in which the coordination sphere is made by two His residues and two carboxylate side chains. Equilibria between equivalent ligands for one Zn(II) binding position have also been observed, the predominant site being made by the side chains of His6, His13 or His14, Glu11, and Asp1 or Glu3 or Asp7, with a slight preference for Asp1.

Short abstract

Zn(II) coordination features to the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide involved in Alzheimer’s disease were revealed by the combined use of X-ray absorption spectroscopy and NMR to monitor Zn(II) binding to Aβ and many modified peptides. Several similar sites are in equilibrium, and the N-terminal amine does not bind Zn(II) in the predominant species detected at physiological pH.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in the elderly population, accounting for 50–80% of dementia cases. The worldwide prevalence of AD is approximately 30 million, a number that is expected to quadruple within the next 40 years.1 As a direct consequence, AD currently represents a major global public health problem with increased impacts of AD over a short time scale.

AD shares some molecular features with other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, prion diseases, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. This includes, in addition to the presence in diseased brains of proteinaceous aggregates, the role of metal ions, mainly copper and zinc, which are directly involved in the degeneration. Indeed, several studies have shown abnormalities in brain homeostasis and in metabolism of copper and zinc ions in neurodegenerative diseases.2 In AD, the neurohistological hallmarks detected post-mortem are extracellular amyloid plaques, also called senile plaques, and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated Tau protein. It has been proposed that the apparition of the amyloid plaques precedes, and thus likely induces, the hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein and the associated neuronal degeneration.1 According to the amyloid cascade hypothesis, the mismetabolism of a peptide, called amyloid-β (Aβ), its accumulation, and aggregation in insoluble forms in the senile plaques are thus key early events in AD pathogenesis. In addition, soluble monomeric forms are found in healthy brains, while the amyloid plaques, rich in Aβ aggregates and copper and zinc ions, are detected in AD patient’s brains.3,4

The Aβ peptide is mainly a 40/42-residue peptide with a N-terminal hydrophilic part containing potential ligands of metal ions (from positions 1 to 16) and a C-terminal hydrophobic part (from positions 17 to 42). Aβ is able to bind metal ions using several residues including the N-terminal amine, the side chains of the carboxylic acid residues at positions 1 (Asp), 3 (Glu), 7 (Asp), and 11 (Glu), and the side chains of the three His residues at positions 6, 13, and 14. These residues are all located in the 1–16 region, which is located near the central hydrophobic core (residues 17 to 21) involved in Aβ dimerization (first step of the aggregation), and thus binding of metal ions can modulate the aggregating properties of Aβ.3,5,6 Analyses by different NMR techniques and other means showed that adding Zn(II) to Aβ40 affected predominantly the first 16 amino acids.7,8 Thus, it is well established that the first coordination sphere of Zn binding lies in the first 16 amino acids sequence (peptide noted Aβ16), which is a correct model of the first coordination sphere on Zn(II) binding to the soluble monomeric Aβ40/42. However, it is not excluded that the other part of the peptide (amino acids 17–40/42) could contribute to the second or third coordination sphere and hence modulate slightly the coordination.

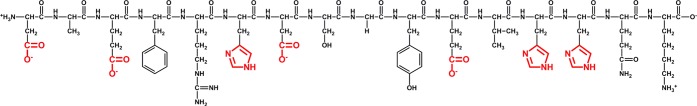

Scheme 1. Aβ Peptide in the Protonation State Predominant at pH 7.4.

The functional groups of the amino acid residues potentially involved in Zn(II) binding are highlighted in red.

In line with the previous statements and supported by studies in vitro, in cell cultures, and in AD model animals, metal ions have been proposed to play key roles in the development of AD via their intervention in the amyloid cascade process.1−3 In contrast to redox-active Cu ions, for which the deleterious impact in AD is linked to oxidative stress3,9−11 and to a lesser extent to formation of oligomeric and fibrillar aggregates5 is acknowledged, the impact of the redox-silent Zn ion is less obvious.12,13 A positive impact of Zn(II) has mainly been proposed, with modes of action that include the precipitation of Aβ in excess into a redox-inert form, precipitation of toxic aggregates, formation of nontoxic aggregates,12,14−16 and chaperone mimicking,17 while negative effects of Zn were mainly attributed to the promotion of oligomeric forms.18,19 Additionally, Zn(II) is the most common transition metal ion involved in neuronal signal transmission being released by certain glutamatergic neurons and can be present in high amounts in the synaptic cleft.20−22 Both Cu and Zn(II) ions can bind Aβ in the synaptic cleft since the dissociation constants of Aβ for Cu(II) and Zn(II) are ∼10–10 M23,24 and ∼10–5 M,24,25 respectively, while their respective concentration can reach ∼10 μM26,27 and 300 μM.20 Note that the dissociation constant of Aβ for Cu(I) is still under debate, with the most relevant propositions spanning from 10–7 M28 to 10–10 M.29 In addition, Zn(II) is found at higher concentration (∼1 mM) than Cu (∼400 μM) in the senile plaques.30−32 Most of the current chemical studies on the influence of metal ions in the amyloid cascade are mainly dedicated to the role of Cu, because it seems to be the most pertinent therapeutic target for chelation therapy. However, Zn(II) is also important since it can have a direct impact in the amyloid cascade according to the elements discussed above but also because it can interfere with the deleterious role of Cu. As a consequence, there is a need for better understanding of how Zn(II) intervenes in the amyloid cascade. The first step to reach this long-term objective is to decipher the coordination site of Zn(II) in the N-terminal part of the peptide. This is highly difficult because there is no direct way to investigate Zn(II) interactions with the multiple possible anchoring sites (due to the spectroscopically silent nature of Zn(II)). In addition, the flexibility of the peptide precludes any characterizations by X-ray diffraction studies. As a consequence, there are currently several coordination models debated in the literature (refs (13) and (33) and Table S1). To circumvent these limitations, we investigate Zn(II) binding to Aβ16 (a well-accepted model for Zn coordination to the full-length Aβ40/42)7,8,34 and a wide series of its modified counterparts by NMR and XAS (X-ray absorption spectroscopy) spectroscopies. Throughout the description of the present work, Aβ16 will be noted Aβ for convenience reasons. EXAFS (extended X-ray absorption fine structure) is useful to determine the number of surroundings atoms, while the impact of peptide modifications on Zn(II)–peptide species can be monitored by XANES (X-ray absorption near-edge structures). The evaluation of Zn(II)-induced alterations of the NMR signatures of Aβ and its modified counterparts also brings new insights into the Zn(II) binding site to Aβ. In addition, the results of affinity measurements of Zn to Aβ and its modified counterparts were also integrated.25 Hence, the strength and robustness of the present study lie in the use of several complementary techniques and samples, which is unparalleled in the literature.

Results

Zn(II) Coordination to the Aβ Peptide

EXAFS

Due to its d10 electronic configuration, the Zn(II) ion is “silent” in most of the classical spectroscopic techniques (UV–vis, EPR, etc.). Hence, its coordination sphere can mainly be directly probed by X-ray absorption spectroscopy, either XANES or EXAFS. The XANES signature carries a lot of structural information that has been analyzed qualitatively. The analysis is described below since not only the Aβ peptide but also modified peptides have been studied (see paragraph Zn(II) Coordination to Modified Aβ Peptides: XANES). More quantitative data can be obtained only after simulation of the spectrum. Development of simulation approaches that can be applied to the study of biological systems are currently emerging but still require a starting structural dataset, provided for instance by X-ray crystallography.35 Since such structural data are not available in the present case, exploration of XANES simulations has been considered to be outside the scope of our study.

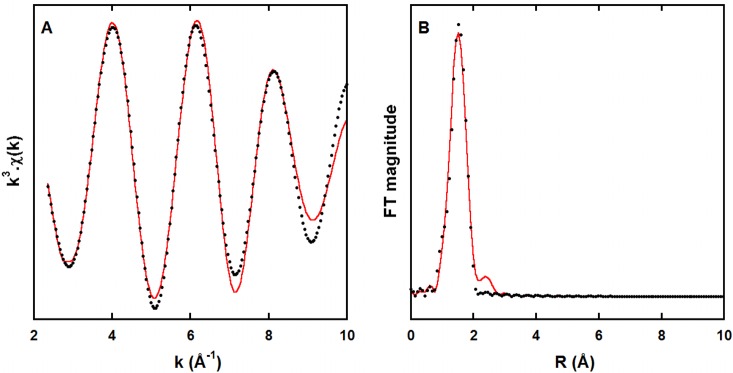

EXAFS data can give access to the nature, number, and distance of the coordinating atoms. However, in the case of the Aβ peptides, the data recorded suffer from the ill-defined coordination sphere of the Zn(II) ions, and in line with previous observations,34,36,37 the number of useful oscillations is limited. This is a common feature of such peptidic species that differ from either Zn metalloprotein38 or inorganic complexes,39 for which more insights can be obtained due to a higher number of well-resolved oscillations. Hence, only the first coordination sphere can be determined in the present case. Experimental and fitted first coordination shell EXAFS spectra and their corresponding Fourier transform of Zn(II) bound to Aβ at pH 6.9 are shown in Figure 1 (and the corresponding unfiltered data are shown in Figure S1). The EXAFS oscillations are best reproduced with a 4N/O shell at an average distance of 1.98 Å from the metallic center (see all parameters in Table S2). In addition, to confirm the four-coordination of the Zn center, the bond-valence sum (BVS) theory was applied.40,41 The bond valence calculated using the equation reported by Thorp40 is equal to 0.52, in line with the corresponding calculated Zn oxidation state of 2.08 in the case of a four-coordinated Zn, while a five-coordination environment would have led to an unrealistic value (2.60) for the Zn oxidation state. This strongly supports a tetrahedrally bound Zn(II), in line with the most widespread environment for this ion in biological systems.42

Figure 1.

k3-Weighted experimental (black dots) and least-squares fitted (red line) first coordination shell EXAFS spectra of the Zn(Aβ) at pH 6.9 (A) and the corresponding non-phase-shift-corrected Fourier transforms (B). Recording conditions: [Aβ] = 1.0 mM, [Zn(II)] = 0.9 mM in Hepes buffer 50 mM, T = 20 K.

NMR

Another way to investigate the coordination sphere of the Zn(II) is to determine how its binding impacts the NMR signature of potential coordinating groups from the Aβ peptide. The impact can be either a broadening of some protons or their up- or downfield shift. Such modifications of the NMR spectrum can witness (i) the direct binding of the Zn(II) ion in the close vicinity of protons affected by the Zn(II)-induced change of Lewis acidity or (ii) the indirect changes in the folding of the peptide upon Zn(II) binding, which affected protons more distant from the Zn(II) binding site, while shifts arise from a different chemical environment of the proton of interest; broadening finds its origin in a fast equilibrium between Zn-bound and free peptide. However, we could not find any direct correlation between the type of Zn(II)-induced modifications (broadening versus chemical shift changes) and the involvement of residues as direct Zn(II) ligands or structural changes. This might be due to the overall very high flexibility of the peptide ligand in which all Zn(II) binding groups can exchange on a fast time scale.

Zn(II) coordination models from published NMR studies are not fully convergent. This could be due to different experimental conditions (length of peptides (Aβ16, Aβ28, Aβ40), buffer, temperature, etc.)43,44 and/or means used for increasing the solubility of the Aβ peptide (use of PEGylated counterpart of the peptide,45 N-terminal acetylation of Aβ,46 or study in water-micelle environment).47 However, such modifications (of the peptide or of the medium) can alter the native Zn(II) binding coordination to the peptide.

In the present study, we performed 1H NMR because the peptide concentration is limited to a maximal value in the low millimolar range, above which precipitation occurs in the presence of Zn(II). Such low concentration precludes the use of 13C or 2D NMR unless 13C- and 15N-labeled peptide is used,7 but in contrast to 13C- or 2D-labeled Aβ40, the modified counterparts are not commercially available. Several recording conditions were tested and conditions under which the Zn(II)-induced broadening of the peptide protons is the most specific, i.e., the effect is clearly observed (not too weak as in ref (43)) but the broadening is not too strong (so that it becomes weakly specific, as observed in ref (44) for a Zn(II):peptide ratio of 1:1), were used. Only the formation of 1:1 Zn(Aβ) as predominant species was detected under those conditions (see Figure S4), in line with previous reports relying on either NMR titration43,44 or determination of the hydrodynamic radius by NMR or gel filtration studies.17,48 Note that proton attributions are based on previous works.49,50

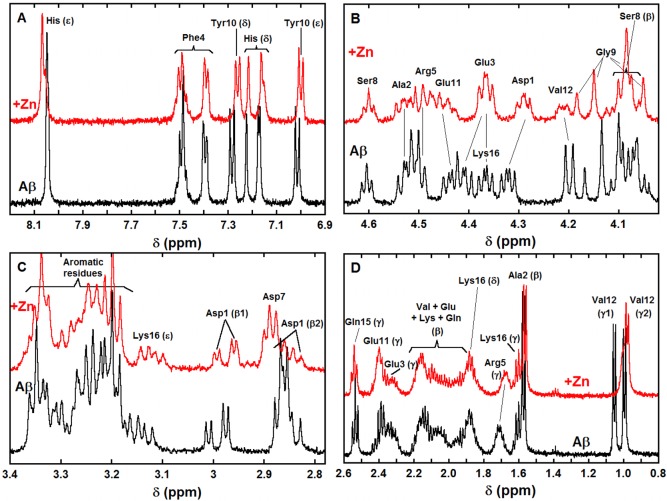

In the aromatic region (panel A in Figure 2), protons of the three His residues are impacted by the addition of Zn(II). The three His Hδ (respectively Hε; for nomenclature of the protons, see Scheme S1) are slightly down-shifted (respectively up-shifted). Only one out of the three His Hδ is significantly broadened upon Zn(II) addition. Both the Hδ and Hε protons from the Tyr10 are down-shifted, with a stronger shift for the Hδ. In the Hα region (panel B in Figure 2), the most obvious modifications induced by Zn(II) are (i) strong broadening of the Val12 Hα, (ii) down-shift of the Asp1 Hα, and (iii) down-shift (respectively up-shift) of the Glu3 and Glu11 Hα, with a relatively intense broadening for the latter one. In the Hβ region (panel C in Figure 2), the two diastereotopic Asp1 Hβ1 and Hβ2 are brought closer and the Asp7 Hβ are up-shifted. Lastly, in the low-field region (panel D in Figure 2), broadening of Val12 Hγ1 is clearly observed as well as a slight broadening and down-shift of the Arg5 Hγ and a weak down-shift of the Ala2 Hβ. The impact of Zn(II) addition on other protons is more difficult to unambiguously detect due to the superimposition or closeness of signals. The various effects of Zn(II) addition on pertinent protons from Aβ amino acid residues are summarized in Table S3, entry 1. Note that for convenience reasons the XAS and NMR data shown in Figures 1 and 4 and in Figures 2, 5, 6, and 7 have been recorded at pH 6.9 and 7.4, respectively (for further details, see the Supporting Information). The pH 7.4 and 6.9 counterparts of Figures 1, S1, 2, and 4 are given in the Supporting Information (Figures S2, S3, S5, and S6).

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra of Aβ (bottom black lines) and of Aβ in the presence of 0.9 equiv of Zn(II) (top red lines) in selected regions (A: aromatic, B: Hα, C: Hβ, D: Hβ and Hγ, unless otherwise specified). [Aβ] = 300 μM, [Zn(II)] = 270 μM in d11-TRIS buffer 50 mM, pH = 7.4, T = 318 K, v = 500 MHz. δ(His6 Hδ) > δ(His14 Hδ) > δ(His13 Hδ). For the details of the amino acid residue nomenclature, see Scheme S1.

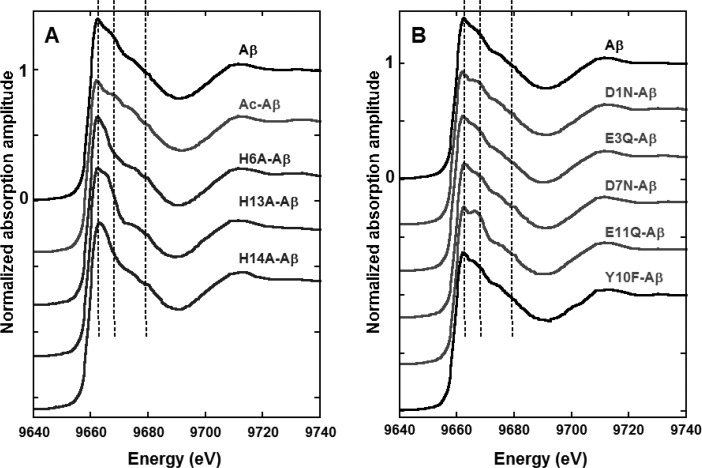

Figure 4.

Zn(II) K-edge XANES spectra of Zn(II) bound to Aβ (black line) and to N mutants (panel A) and O mutants (panel B), Hepes buffer 50 mM pH 6.9, [Zn(II)] = 1.0 mM, [peptide] = 1.1 mM, T = 20 K. Normalization of the amplitude is given for the reference Zn(Aβ) complex.

Figure 5.

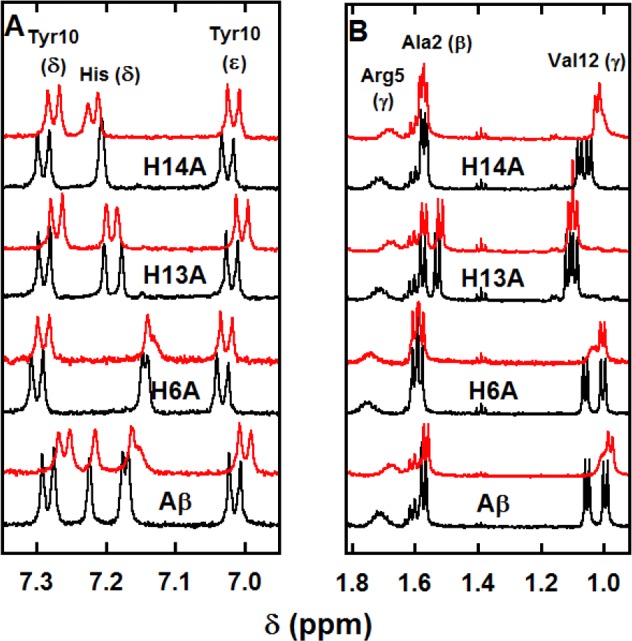

1H NMR spectra of Aβ peptide and His-Ala mutants (bottom black lines) and of Aβ peptide and His-Ala mutants in the presence of 0.9 equiv of Zn(II) (top red lines) in selected regions (panel A: aromatic, panel B: Hβ and Hγ). [peptide] = 300 μM, [Zn(II)] = 270 μM in d11-TRIS buffer 50 mM, pH = 7.4, T = 318 K, v = 500 MHz.

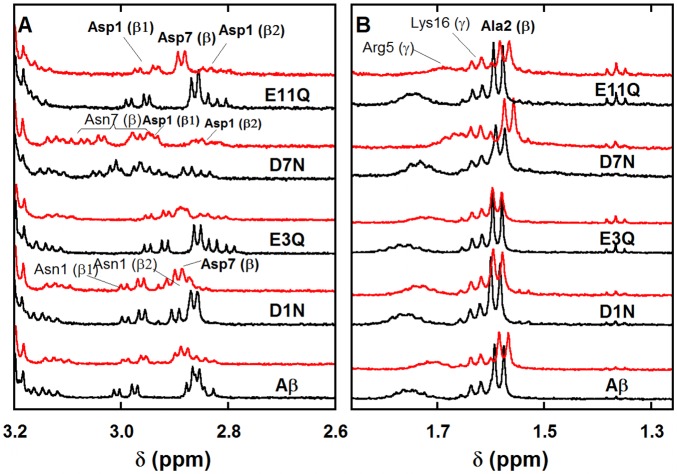

Figure 6.

1H NMR spectra of Aβ peptide and Asp-Asn and Glu-Gln mutants (bottom black lines) and of Aβ peptide and Asp-Asn and Glu-Gln mutants in the presence of 0.9 equiv of Zn(II) (top red lines) in selected regions (panel A: aromatic, panel B: Hβ and Hγ). [peptide] = 300 μM, [Zn(II)] = 270 μM in d11-TRIS buffer 50 mM, pH = 7.4, T = 318 K, v = 500 MHz.

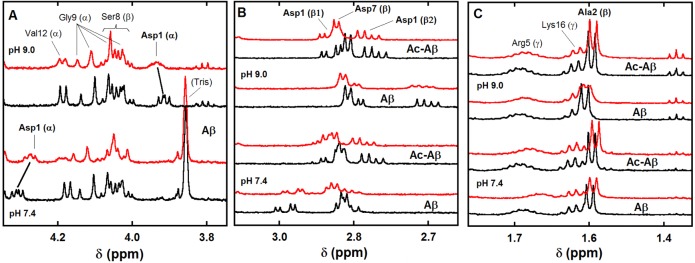

Figure 7.

1H NMR spectra of Aβ and Ac-Aβ peptides (bottom black lines) and of Aβ and Ac-Aβ peptides in the presence of 0.9 equiv of Zn(II) (top red lines) in selected regions as a function of pH (panel A: Hα, panel B: Asp Hβ, * stands for Asp7 protons, and panel C: Ala 2 Hβ). [peptide] = 300 μM, [Zn(II)] = 270 μM in d11-TRIS buffer 50 mM, pH = 7.4 or pH = 9.0, T = 318 K, v = 500 MHz.

Zn(II) Coordination to Modified Aβ Peptides

Affinity Values

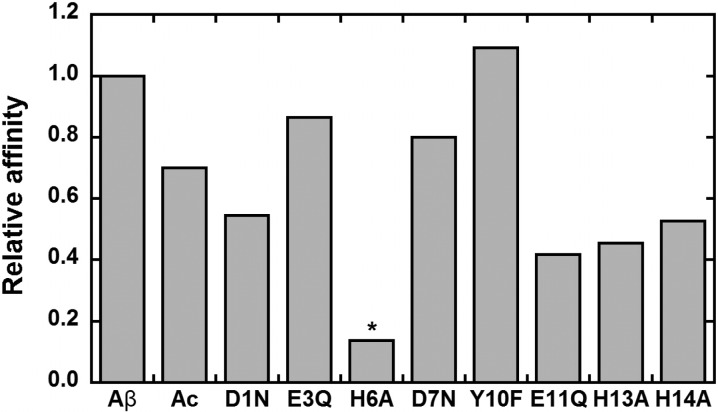

From the data obtained with the sole peptide, it is difficult to determine the Zn(II) binding site. In particular, the NMR study is not sufficient since more than four coordinating groups are impacted by Zn(II) addition. As previously pointed out,13,33,43 this strongly suggests the presence of several possible sites in equilibrium, in line with what has already been evidenced for Cu(I),3,51,52 Cu(II),3,49,51 and Fe(II)3,50,51 ions bound to Aβ peptide. This is the reason that we use here an indirect strategy relying on the use of pertinent modified Aβ peptides. In a previous publication, we have reported the impact of nine Aβ modifications on the Zn(II) binding affinity.25 Evaluation of the affinity is another indirect way to probe the amino acid residues important for Zn(II) binding. The results are recounted in Figure 3, which shows the relative Zn(II) affinity of each altered peptide (namely, Ac-Aβ, D1N-Aβ, E3Q-Aβ, H6A-Aβ, D7N-Aβ, Y10F-Aβ, E11Q-Aβ, H13A-Aβ, and H14A-Aβ) with respect to Aβ. The impact of acetylation and His6 and Glu11 mutation were in line with previous data obtained by calorimetry.53

Figure 3.

Zn(II) binding affinity values for the various modified peptides relative to Aβ. For the H6A mutant (*), the given value corresponds to a maximum value.

Here, we have performed XANES and NMR studies of Zn(II) binding to the same nine altered peptides. [Note that preliminary EXAFS data were recorded with all modified peptides, but they do not show any significant differences with the Aβ peptide. Trying to obtain more insightful data would have required too much time than the beam-time allocated.] Monitoring how sequence alteration impacts the XANES signature of the Zn(II)–peptides species helps to identify the amino acids key for Zn(II) binding. By NMR, changes induced by Zn(II) binding on the peptides will be compared between the Aβ and the modified peptides. Two possibilities can be foreseen: (i) if the changes induced by Zn(II) to the NMR spectrum of the Aβ peptide and its modified counterparts are identical, then the modified amino acid residue is not strongly involved in Zn(II) binding; (ii) if the changes induced by Zn(II) to the NMR spectrum of the Aβ peptide and its modified counterparts are different (Zn(II) can have either a weaker or a stronger impact), then the modified amino acid residue is involved in Zn(II) binding. Because insights gained into Zn(II) binding site using spectroscopic studies obtained with modified peptides are indirect, use of complementary techniques is required to get reliable insights and data analysis has to be performed very carefully.

XANES

Figure 4 shows the XANES patterns of Zn(II) bound to Aβ peptide and altered counterparts on the N (panel A) and O (panel B) amino acid residues with coordinating abilities (to compare with the XANES signature of free Zn(II), see Figure S7). As a general trend, the white line intensity of the XANES spectra of all Zn(II)–peptides complexes is in line with a four-coordination of the metal center,38 thus (i) strengthening the EXAFS data for the Zn(Aβ) species and (ii) indicating that when a residue is modified and made unable to bind the Zn(II) ion, it is replaced by another equivalent one keeping the coordination number to four in the Zn(II) complexes of modified peptides. In addition, the pattern of the white line of all peptidic complexes except the Zn(E11Q-Aβ) is reminiscent of the signature of biological systems with two His residues bound (and a coordination number of four).38 In line with the previous statement, this suggests that when one His is mutated, preventing its Zn(II) binding, it is replaced by another one. Regarding the E11Q mutation, the spectrum of the Zn(II) complex resembles more a system with three His bound.38 Hence, this would imply that in this particular case the binding of the carboxylate group from Glu11 is replaced by the third available His. With the desire not to overinterpret the XANES data, we have mainly focused on the comparison of the impact of mutations of the Aβ peptide on the XANES signatures of the Zn(II) complexes to decipher the most important residues for Zn(II) binding. While some mutations, namely, H13A, H6A, H14A, and E11Q, induce significant differences in the XANES fingerprints by comparison to Zn(Aβ), other modifications, namely, N-terminal acetylation, and D1N, E3Q and D7N mutations induce weaker changes. Finally, the Y10F mutation has no impact.

NMR

Histidine Residues

To identify from which His the Hδ that is strongly broadened in the presence of Zn(II) comes from, the impact of Zn(II) binding to the three His-Ala mutants was studied (Figure 5, panel A, Figures S8–S10, and Table S3, entries 3–5). With the H6A-Aβ and to a lesser extent the H14A-Aβ mutants but not with the H13A-Aβ, the broadening is maintained. This agrees with the NMR of the Aβ peptide, in which the His13 Hδ signal undergoes a strong broadening in the presence of Zn(II). This is in line with the examination of the Val12 Hγ resonance plotted in Figure 5, panel B, which is affected (both broadened and shifted) by Zn(II) addition for the Aβ peptide and the H6A-Aβ and H14A-Aβ mutants, but not for H13A-Aβ. Here, we can also note that the Arg5 Hγ is down-shifted upon addition of Zn(II) to the Aβ peptide and the H13A-Aβ and H14A-Aβ mutants but not to the H6A-Aβ mutant, indicating that this Zn(II)-induced shift is due to Zn(II) binding to the nearby His6 rather than to Arg5 itself as previously proposed.13 These observations point to the involvement of the three His residues in the Zn(II) binding, but with various contributions. In particular, the roles of His13 and His6 are probed by broadening on the Val12 and Arg5 resonances, respectively, which are not observed with the H13A-Aβ and H6A-Aβ mutants.

Carboxylate-Containing Residues

The effect of Zn(II) on the carboxylate groups was evaluated by comparison of the impact of Zn(II) on the Aβ peptide and on the D1N-Aβ, E3Q-Aβ, D7N-Aβ, and E11Q-Aβ mutants. Analysis of the Asp1 Hβ region (Figure 6, panel A, Figures S11–S14, and Table S3, entries A, 6–9) and of the adjacent Ala2 Hβ region (Figure 6, panel B, Figures S11–S14, and Table S3 entries B, 6–9) indicates that (i) when the carboxylate group from D1 is amidated, Zn(II) has no more impact, thus suggesting that the carboxylate group from D1 is involved, at least partially, in Zn(II) binding by the Aβ peptide; (ii) in contrast, a similar Zn(II) effect on the Aβ peptide and on the E11Q-Aβ mutant is observed, meaning that when Glu11 binding to Zn(II) is precluded, this has no direct impact on Zn(II) binding by Asp1; (iii) with the other two mutants, E3Q-Aβ and D7N-Aβ, an intermediate situation is observed. Zn(II) impacts the Asp1 and Ala2 Hβ but in a different way than it does for the Aβ peptide. This suggests that Zn(II) binds to Glu3 and Asp7 in Aβ. From these data, it is proposed that Asp1, Glu3, and Asp7 side chains compete for one Zn(II) binding position, while Glu11 binds to Zn(II) independently to other carboxylate residues.

N-Terminal Amine

Modifications on the Asp1 Hα of the Aβ (panel A in Figure 7) and on the Asp1 Hβ of the Aβ and Ac-Aβ peptides (panel B in Figure 7 and Figure S15) upon Zn(II) binding have been investigated as a function of pH. On the Asp1 Hα of the Aβ, there is a down-shift and a weak broadening at pH 7.4, while the broadening is more intense at pH 9.0, along with an up-shift upon Zn(II) addition. The impact of Zn(II) on the Asp1 Hβ1 and Hβ2 at pH 7.4 is equivalent in the presence (Aβ) or absence (Ac-Aβ) of the free N-terminal amine, while a striking difference was observed with the D1N-Aβ peptide, for which Zn(II) addition has no impact on both Asp1 Hβ (panel A, Figure 6). Hence, the Zn(II)-induced modification detected on the Aβ peptide is mainly due to Zn(II) binding by the side chain of Asp1 rather than by the N-terminal amine. At pH 9.0, the situation is different since the broadening observed on the Aβ is no longer detected with the Ac-Aβ. In addition, the Ala2 Hβ is also a sensitive probe of Zn(II) binding in the N-terminal region (panel C in Figure 7). When the pH is increased from 7.4 to 9.0, broadening of the Ala2 Hβ of the Aβ peptide is strongly reinforced, whereas this effect is not observed with the acetylated counterpart. This suggests that the broadening of the Ala2 Hβ originates from the Zn(II) binding to the N-terminal amine, which is strongly (respectively weakly) observed at pH 9.0 (respectively 7.4). In brief, Zn(II) induces a stronger broadening of the Asp1 Hβ2 and of the Ala2 Hβ of the Aβ peptide at pH 9 compared to pH 7.4, an effect that is not observed with the Ac-Aβ (Figure 7, panels B and C, top versus bottom), suggesting that the N-terminal amine is not bound to Zn(II) binding at pH 7.4.

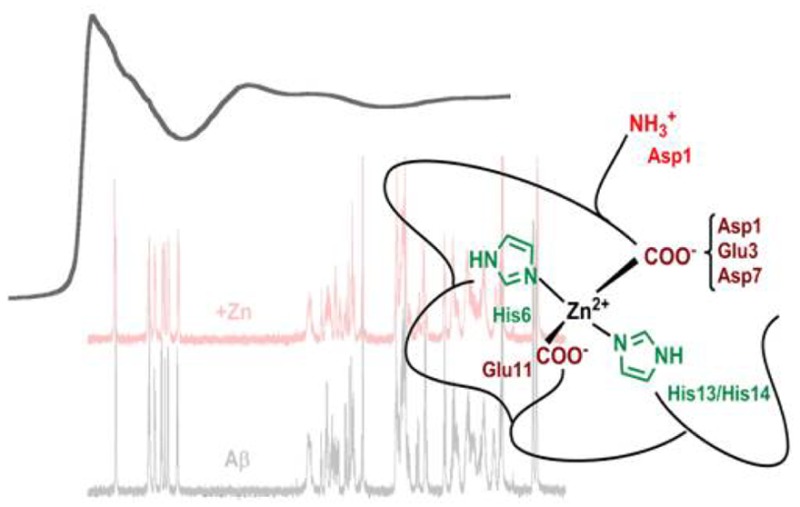

Discussion

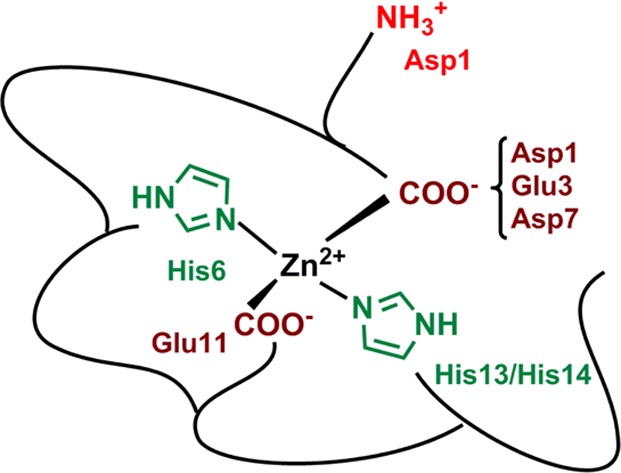

On the basis of the various results described above, we propose the unprecedented model shown in Scheme 2 regarding Zn(II) binding to Aβ. Near pH 7, the main Zn(II) coordination sphere is [2N2O], made of two His residues and two carboxylate groups. The tetrahedral coordination is deduced from the EXAFS data (Table S2) and is in line with what is reported for Zn(II) preferred binding geometry in biological systems.42 On the basis of NMR, XANES, and affinity data, an equilibrium between His13 and His14 for one binding position is anticipated, while His6 remains constantly bound. Regarding the carboxylate groups, binding by Glu11 is predominant, while the other three carboxylate side chains share the fourth coordination position, with a preference for Asp1.

Scheme 2. Proposed Zn(II) Binding Site in Aβ (Predominant Species at pH 7.4).

The present study has ruled out the possibility of having the Arg5 or the Tyr10 residues involved in Zn(II) binding as still recently proposed (reviewed in ref (13)) by evidencing that the Zn(II)-induced modification of their NMR signatures is due to the binding of adjacent residues (His6 and Glu11, respectively) and not to their direct binding. In particular the NMR signature of the Y10F-Aβ mutant undergoes the very same Zn(II)-induced modification as the Aβ (compare entries 1 and 10 in Table S3 and see Figure S16).

More importantly, the present proposition differs from previous ones (see Table S1) regarding several points discussed below.

The N-Terminal Amine Is NOT Bound to Zn(II) in the Predominant Species at pH 7.4

The coexistence of two Zn(Aβ) species at pH 7.4 has been evidenced in the present study. The N-terminal amine has not been considered as a ligand in the predominant species at pH 7.4 because acetylation of the Aβ peptide does not induce strong alteration in comparison to Aβ neither in the NMR data nor in the XANES signatures of the Zn(II)–peptides complexes. This is in line with previous affinity data (Figure 3), in which acetylation of the N-terminal amine induces only a weak decrease in the Zn(II) affinity. In contrast, at pH 9, acetylation induces important changes with respect to Zn(II) binding as probed by NMR (Figure 7). A similar trend is observed by XANES, where differences between Zn(Aβ) and Zn(Ac-Aβ) are more obvious at higher pH (Figure S6). This strongly supports that the coordination change occurring when the pH is increased is the binding of the N-terminal amine to the Zn(II). This is in line with previous pH-dependent studies.43,45 Taking into account the pH dependence is a prerequisite to sort out the possibility of having the N-terminal amine bound to Zn(II), this feature has thus been overlooked when only one pH value (near the physiological pH) was investigated (entries 2, 3, and 5 in Table S1). Misinterpretation of previous NMR data leading to the conclusion that the N-terminal amine is bound to Zn(II) in the main species present at pH 7.47,44,47 is probably due to (i) the involvement of the Asp1 side chain in Zn(II) binding, (ii) the presence of a mixture of two Zn(Aβ) complexes at pH 7.4 with the N-terminal amine linked to Zn(II) although in the minor species, and (iii) changes in the speciation of the two complexes due to different experimental conditions. In the present study, several consistent insights have been obtained by combining the use of the acetylated peptide, a pH-dependent study, and XANES data (in addition to NMR). Whether the proposed binding of the N-terminal amine in the predominant form at higher pH induces other changes in the Zn(II) coordination sphere is beyond the scope of the present paper.

It is worth noting that the nonbinding of the N-terminal amine to the Zn(II) ion has two main direct consequences: (i) Ac-Aβ is a correct model regarding Zn(II) binding in the main species present at physiological pH, thus strengthening the pertinence of previous studies with the Ac-Aβ peptide46,53−56 and more recent studies of the H6R mutation and Ser8 phosphorylation impact on Zn(II) binding, both performed with acetylated peptides,57,58 and (ii) the better solubility of the Zn(Ac-Aβ) compared to the Zn(Aβ) (as mentioned above) may be due to a change in the charge of the system since the N-terminal amine remains protonated in Zn(Aβ)46 while being neutral when acetylated.

Two Histidine Residues Are Bound to the Zn(II) Center

The simultaneous coordination of the three His side chains is not considered here to be the most pertinent configuration. Indeed, it seems from literature data on truncated peptides (EVHH N-terminally protected or not) that coordination of the His13 is not favored. When the peptides start at position 11 (with or without acetylation), then the carboxylate group from Glu11 and the imidazole ring of His14 are involved in Zn(II) coordination.54,59 Here the involvement of His13 is also proposed based on the strong broadening observed on Val12 protons that are no longer observed with the H13A-Aβ mutant (Figure S17). In addition, in contrast to the H6A mutation, H13A and H14A mutations have no strong impact on the affinity values, indicating that His13 or His14 could be exchanged. We thus propose that there is an equilibrium between Glu11-His13 and Glu11-His14 as binding couples for Zn(II). This coordination feature seems to be important, since both H13A and H14A mutation impact the Zn(II)-modulated Aβ aggregation.16 The previous proposition of simultaneous binding of the three His may be due to the fact that indeed all three His are involved in Zn(II) binding and that quantification of their relative implication by NMR is difficult.7,43,44,46,47

Involvement of Two Carboxylate Side Chains

Taking into account the four-coordination of the Zn(II) center determined by EXAFS, the involvement of two His in Zn(II) binding and the noninvolvement of the N-terminal, two positions remained to be occupied by O-ligands. While Glu11 has a predominant role in Zn(II) binding as previously observed,46,47,54 the second position may be occupied by Asp1 with only a slight preference with respect to other carboxylate residues (i.e., Glu3 and Asp7). The possibility of having one bidendate carboxylate bound to the Zn(II) is ruled out based on the EXAFS data, which are correctly reproduced with four equal distances, while having the bidentate coordination of the carboxylate would impose a longer distance (2.4 Å).42,60 We cannot (completely) exclude that a water molecule is the fourth ligand, because effects on Asp1, Glu3, and Asp7 upon Zn(II) binding observed by NMR and XANES could be explained via H-bonding of these residues with the coordinating water.

Comparison with the Cu(II) Binding Site

The here-proposed model of the predominant Zn(II) binding site to Aβ shows that the site differs from the Cu(II) binding site. In the case of Cu(II), the predominant site (called component I) is composed of the N-terminal amine from Asp1, the carbonyl group from the peptide bond between Asp1–Ala2, and the imidazole groups from His6 and His13 or His14 in an almost square planar geometry.3,61 Thus, a main difference between the Cu(II) and Zn(II) site is the involvement of the N-terminal amine, a main ligand for Cu(II), but not Zn(II). In contrast the His are involved in a very similar way in the binding site of both metal ions. In general, the Cu(II) and Zn(II) binding sites are different, but partially overlapping. This is in line with the analysis of the simultaneous binding of Cu(II) and Zn(II), i.e., in the bimetallic Cu(II),Zn(II)-Aβ species, in which both sites are partially different compared to the sites in the monometallic complexes (Cu(II)-Aβ and Zn(II)-Aβ).62

Concluding Remarks

In the present paper, we have reported a very complete study of Zn(II) binding to the Aβ peptide based on investigations of the impact of peptide modifications on the spectroscopic (NMR and XAS) signatures of the Zn(peptides) complexes. Although indirect, the large quantity of data obtained allows us to propose a new Zn(II) coordination site to Aβ. Some key features, such as the noncoordination of the N-terminal amine and the exchange of equivalent ligands for one binding position, have been revealed.

Since the N-terminal amine of Aβ is involved in Cu(II) binding, coordination of Zn(II) and Cu(II) differ at physiological pH. This is anticipated to impact their respective binding properties to physiologically relevant N-truncated1,61,63−66 or N-elongated67,68 Aβ. Indeed the Zn(II) binding site would not be strongly altered within the N-truncated1,61,63−66 or N-elongated Aβ, whereas Cu(II) binding is strongly influenced by both N-truncation or N-elongation due to coordination of the N-terminal amine.

The coordination results obtained in the present study also impact the current view on the respective role of Zn(II) and Cu(II) in Aβ aggregation. Although there is no consensus in the literature on how Zn(II) modulates Aβ aggregation,19 all reports agree that the impacts of Zn(II) and Cu(II) are different. This could be linked to an overall charge of the Zn(Aβ) and Cu(Aβ) complexes that differs by +1 unit at about neutral pH, due to the protonation of the free N-terminal amine in the case of Zn(II), while it is deprotonated and bound to the Cu(II). For the full-length Aβ40/42 peptides, the overall charge is thus −1 for the Zn(Aβ) and −2 for the Cu(Aβ), a difference that could be responsible for the higher tendency of the Zn(II) ion to induce aggregation and formation of amorphous aggregates.59

Ongoing studies include the determination of the high pH binding site of Zn(II) to Aβ and of the pKa between the two species present at physiological pH, evaluation of the impact of some familial mutations, and more importantly how biologically relevant peptide modifications impact the Zn(II)-induced Aβ aggregation, one key parameter in Alzheimer’s disease.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Reagents were commercially available and were used as received. Hepes buffer (sodium salt of 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethanesulfonic acid) was bought from Fluka (bioluminescence grade). d11-TRIS (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) and d19-BIS-TRIS (2-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol) were bought from Sigma-Aldrich. The Zn(II) ion source was Zn(SO4)(H2O)7.

Peptides

Aβ16 peptide (sequence DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQK and referred to as Aβ in the following) and the modified counterparts (Ac-Aβ, Ac-DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQK; H6A-Aβ, DAEFRADSGYEVHHQK; H13A-Aβ, DAEFRHDSGYEVAHQK; H14A-Aβ, DAEFRHDSGYEVHAQK; D1N-Aβ, NAEFRHDSGYEVHHQK; E3Q-Aβ, DAQFRHDSGYEVHHQK; D7N-Aβ, DAEFRHNSGYEVHHQK; E11Q-Aβ, DAEFRHDSGYQVHHQK; and Y10F-Aβ, DAEFRHDSGFEVHHQK) were bought from GeneCust (Dudelange, Luxembourg) with purity grade >98%.

Stock solutions of the peptides were prepared by dissolving the powder in Milli-Q water (resulting pH ∼2). Peptide concentration was then determined by UV–visible absorption of Tyr10 considered as free tyrosine (at pH 2, (ε276–ε296) = 1410 M–1 cm–1). For the Y10F-Aβ mutant, the absorption of the two Phe ((ε258–ε280) = 390 M–1 cm–1) was used.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

Zn(II) K-edge XANES and EXAFS spectra were recorded at the BM30B (FAME) beamline at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France).69 The storage ring was operated in 7/8 + 1 mode at 6 GeV with a 200 mA current. The beam energy was selected using a Si(220) N2 cryo-cooled double-crystal monochromator with an experimental resolution close to that theoretically predicted (namely, ∼0.5 eV FWHM (full width at half maximum) at the Zn energy).70 The beam spot on the sample was approximately 300 × 100 μm2 (H × V, FWHM). Because of the low Zn(II) concentrations, spectra were recorded in fluorescence mode with a 30-element solid-state Ge detector (Canberra) in frozen liquid cells in a He cryostat. The temperature was kept at 20 K during data collection. The energy was calibrated with Zn metallic foil, such that the maximum of the first derivative was set at 9659 eV. XANES Zn(II) data were collected from 9510 to 9630 eV using 5 eV steps of 3 s, from 9630 to 9700 eV using 0.5 eV steps of 3 s, and from 9700 to 10 000 eV with a k-step of 0.05 Å–1 and 3 s per step. For each sample three scans were averaged, and spectra were background-corrected by a linear regression through the pre-edge region and a polynomial through the postedge region and normalized to the edge jump. EXAFS Zn(II) data were collected from 9510 to 9630 eV using 5 eV steps of 3 s, from 9630 to 9700 eV using 0.5 eV steps of 3 s, and from 9700 to 10 500 eV with a k-step of 0.05 Å–1 and an increasing time of 4–10 s per step. Samples for XAS measurements were prepared in the presence of 10% glycerol as cryoprotectant.

NMR

NMR experiments were realized on a Avance 500 Bruker NMR spectrometer. Several solutions of the buffer deuterated tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (d11-TRIS or d19-BISTRIS) at different pH were prepared by solubilization of the buffer powder in D2O and acidification or basification with D2SO4 or NaOD. Peptide samples were freshly prepared from a D2O stock solution (see above peptide stock solution preparation). Peptides (final concentration 300 μM) were added to several TRIS/BIS-TRIS solutions at a given pH (final concentration 50 mM). The residual water signal was suppressed by a presaturation procedure. Zn(II) was directly added into the NMR tube.

Note that studies were performed in H2O (XAS) or in D2O (NMR). However, for clarity and consistency, we decided to use the notation pH even when the measurements were made in D2O. pD was measured using a classical glass electrode according to pD = pH* + 0.4, and the apparent pH value was adjusted according to ref (71), pH = (pD – 0.32)/1.044, or equivalently to ref (72), pH = 0.929pH* + 0.41, to be in ionization conditions equivalent to those in H2O.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility for provision of beamtime (experiment 30-02-1060), the FAME staff for their support, and Pier-Lorenzo Solari (synchrotron SOLEIL) for fruitful discussions. The ERC aLzINK grant (ERC-StG-638712) is acknowledged for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01733.

Scheme of the Aβ16 peptide sequence, models of Zn binding to Aβ proposed in the literature, first coordination shell structural data of Zn(Aβ) at pH 7.4 and 6.9 obtained from EXAFS fits, unfiltered experimental EXAFS data of Zn(Aβ) at pH 6.9, unfiltered and k3-weighted experimental EXAFS data of Zn(Aβ) at pH 7.4, XANES spectra of Zn(Aβ) complexes for all the modified peptides described in the text at pH 7.4, XANES spectra of Zn in buffer, NMR spectra of Zn(Aβ) at pH 6.9 and 7.4, NMR spectra of Zn(Aβ) complexes for all the modified peptides described in the text, Zn-induced NMR broadenings and shifts of the Aβ peptides (PDF)

Author Present Address

§ (B.A.) Université de Bordeaux, ChemBioPharm INSERM U1212 CNRS UMR 5320, Bordeaux, France.

Author Present Address

□ (P.F.) Institut de Chimie, UMR 7177 CNRS-Université de Strasbourg, 4 Rue Blaise Pascal, Institut Le Bel, 67081 Strasbourg, France.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Holtzman D. M.; Morris J. C.; Goate A. M. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 77sr1. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski H.; Luczkowski M.; Remelli M.; Valensin D. Copper, Zinc and iron in neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and prion diseases). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2129–2141. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hureau C. Coordination of redox active metal ions to the APP and to the amyloid-β peptides involved in AD. Part 1: an overview. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2164–2174. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noël S.; Cadet S.; Gras E.; Hureau C. The benzazole scaffold: a SWAT to combat Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7747–7762. 10.1039/c3cs60086f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viles J. H. Metal ions and amyloid formation in neurodegenerative diseases. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2271–2284. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alies B.; Hureau C.; Faller P. Role of Metallic Ions in Amyloid Formation: General Principles from Model Peptides. Metallomics 2013, 5, 183–192. 10.1039/c3mt20219d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson J.; Pierattelli R.; Banci L.; Graslund A. High-resolution NMR studies of the zinc-binding site of the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. FEBS J. 2007, 274, 46–59. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei-Ghaleh N.; Giller K.; Becker S.; Zweckstetter M. Effect of zinc binding on β-amyloid structure and dynamics: implications for Aβ aggregation. Biophys. J. 2011, 101, 1202–1211. 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hureau C.; Faller P. Aβ-mediated ROS production by the Cu ions: structural insights, mechanisms and relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimie 2009, 91, 1212–1217. 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing S.; Collin F.; Dorlet P.; Gout J.; Hureau C.; Faller P. Copper and heme-mediated Abeta toxicity: redox chemistry, Abeta oxidations and anti-ROS compounds. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 2573–2595. 10.2174/1568026611212220011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnham K. J.; Masters C. L.; Bush A. I. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2004, 2004, 205–214. 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuajungco M. P.; Faget K. Y. Zinc takes the center stage: its paradoxical role in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. Rev. 2003, 41, 44–56. 10.1016/S0165-0173(02)00219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tôugu V.; Palumaa P. Coordination of Zinc to the Aβ, APP, α-synuclein, PrP. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2219–2224. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuajungco M. P.; Goldstein L. E.; Nunomura A.; Smith M. A.; Lim J. T.; Atwood C. S.; Huang X.; Farrag Y. W.; Perry G.; Bush A. I. Evidence that the beta -amyloid plaques of Alzheimer’s disease represent the redox-silencing and entombment of Aβ by zinc. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 19439–19442. 10.1074/jbc.C000165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garai K.; Sahoo B.; Kaushalya S. K.; Desai R.; Maiti S. Zinc Lowers Amyloid-β Toxicity by Selectively Precipitating Aggregation Intermediates. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 10655–10663. 10.1021/bi700798b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tõugu V.; Karafin A.; Zovo K.; Chung R. S.; Howells C.; West A. K.; Palumaa P. Zn(II)- and Cu(II)-induced non-fibrillar aggregates of amyloid-beta (1–42) peptide are transformed to amyloid fibrils, both spontaneously and under the influence of metal chelators. J. Neurochem. 2009, 110, 1785–1795. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abelein A.; Gräslund A.; Danielsson J. Zinc as chaperone-mimicking agent for retardation of amyloid-β peptide fibril formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 5407–5412. 10.1073/pnas.1421961112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomonov I.; Korkotian E.; Born B.; Feldman Y.; Bitler A.; Rahimi F.; Li H.; Bitan G.; Sagi I. Zn2+-Aβ40 complexes form metastable quasi-spherical oligomers that are cytotoxic to cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 20555–20564. 10.1074/jbc.M112.344036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller P.; Hureau C.; Berthoumieu O. Role of Metal Ions in the Self-assembly of the Alzheimer’s Amyloid-β Peptide. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12193–12206. 10.1021/ic4003059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson C. J. Neurobiology of zinc and zinc-containing neurons. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1989, 31, 145–238. 10.1016/S0074-7742(08)60279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson C. J.; Giblin L. J.; Krezel A.; McAdoo D. J.; Muelle R. N.; Zeng Y.; Balaji R. V.; Masalha R.; Thompson R. B.; Fierke C. A.; Sarvey J. M.; de Valdenebro M.; Prough D. S.; Zornow M. H. Concentrations of extracellular free zinc (pZn)e in the central nervous system during simple anesthetization, ischemia and reperfusion. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 198, 285–293. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson C. J.; Koh J. Y.; Bush A. I. The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 449–462. 10.1038/nrn1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alies B.; Renaglia E.; Rozga M.; Bal W.; Faller P.; Hureau C. Cu(II) affinity for the Alzheimer’s Peptide: Tyrosine fluorescence studies revisited. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 1501–1508. 10.1021/ac302629u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawisza I.; Rozga M.; Bal W. Affinity of peptides (Aβ, APP, α-synuclein, PrP) for metal ions (Cu, Zn). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2297–2307. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noël S.; Bustos S.; Sayen S.; Guillon E.; Faller P.; Hureau C. Use of a new water-soluble Zn sensor to determine Zn affinity for the amyloid-β peptide and relevant mutants. Metallomics 2014, 6, 1220–1222. 10.1039/c4mt00016a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. G.; Cappai R.; Barnham K. J. The redox chemistry of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid beta peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2007, 1768, 1976–1990. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuerenburg H. J. CSF copper concentrations, blood-brain barrier function, and coeruloplasmin synthesis during the treatment of Wilson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2000, 107, 321–329. 10.1007/s007020050026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alies B.; Badei B.; Faller P.; Hureau C. Reevaluation of Copper(I) affinity for amyloid-β peptides by competition with Ferrozine, an unusual Copper(I) indicator. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 1161–1167. 10.1002/chem.201102746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z.; Gottschlich L.; van der Meulen R.; Udagedara S. R.; Wedd A. G. Evaluation of quantitative probes for weaker Cu(i) binding sites completes a set of four capable of detecting Cu(i) affinities from nanomolar to attomolar. Metallomics 2013, 5, 501–513. 10.1039/c3mt00032j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush A. I. The metallobiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2003, 26 (4), 207–214. 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell M. A.; Robertson J. D.; Teesdale W. J.; Campbell J. L.; Markesbery W. R. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998, 158, 47–52. 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. M.; Wang Q.; Telivala T. P.; Smith R. J.; Lanzirotti A.; Miklossy J. Synchrotron-based infrared and X-ray imaging shows focalized accumulation of Cu and Zn co-localized with β-amyloid deposits in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Struct. Biol. 2006, 155, 30–37. 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliorini C.; Porciatti E.; Luczkowski M.; Valensin D. Structural characterization of Cu2+, Ni2+ and Zn2+ binding sites of model peptides associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 352–368. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minicozzi V.; Stellato F.; Comai M.; Dalla Serra M.; Potrich C.; Meyer-Klaucke W.; Morante S. Identifying the minimal Cu and Zn binding site sequence in amyloid-β peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 10784–10792. 10.1074/jbc.M707109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui P.; Wang Y.; Chu W.; Guo X.; Yang F.; Yu M.; Zhao H.; Dong Y.; Xie Y.; Gong W.; Wu Z. How water molecules affect the catalytic activity of hydrolases - A XANES study of the local structures of peptide deformylase. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4 (7453), 1–6. 10.1038/srep07453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellato F.; Menestrina G.; Serra M. D.; Potrich C.; Tomazzolli R.; Meyer-Klaucke W.; Morante S. Metal binding in amyloid beta-peptides shows intra- and inter-peptide coordination modes. Eur. Biophys. J. 2006, 35, 340–351. 10.1007/s00249-005-0041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santis E.; Minicozzi V.; Proux O.; Rossi G.; Silva I.; Lawless M. J.; Stellato F.; Saxena S.; Morante S. Cu(II)–Zn(II) Cross-Modulation in Amyloid–Beta Peptide Binding: An X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 15813–15820. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b10264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachini L.; Veronesi G.; Francia F.; Venturolid G.; Boscherinib F. Synergic approach to XAFS analysis for the identification of most probable binding motifs for mononuclear zinc sites in metalloproteins. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2010, 17, 41–52. 10.1107/S090904950904919X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Baldwin K.; Tierney D. L.; Govindaswamy N.; Gruff E. S.; Kim C.; Berg J.; Koch S. A.; Penner-Hahn J. E. The Limitations of X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy for Determining the Structure of Zinc Sites in Proteins. When Is a Tetrathiolate Not a Tetrathiolate?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 8401–8409. 10.1021/ja980580o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp H. H. Bond valence sum analysis of metal-ligand bond lengths in metalloenzymes and model complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 1585–1588. 10.1021/ic00035a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penner-Hahn J. E. Characterization of “spectroscopically quiet” metals in biology. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 161–177. 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts I. L.; Nadassy K.; Wodak S. J. Analysis of zinc binding sites in protein crystal structures. Protein Sci. 1998, 7, 1700–1716. 10.1002/pro.5560070805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekmouche Y.; Coppel Y.; Hochgrafe K.; Guilloreau L.; Talmard C.; Mazarguil H.; Faller P. Characterization of the ZnII binding to the peptide amyloid-beta1–16 linked to Alzheimer’s disease. ChemBioChem 2005, 6, 1663–1671. 10.1002/cbic.200500057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme C. D.; Viles J. H. Solution 1H NMR investigation of Zn2+ and Cd2+ binding to amyloid-beta peptide (Abeta) of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2006, 1764, 246–256. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damante C. A.; Osz K.; Nagy N. V.; Pappalardo G.; Grasso G.; Impellizzeri G.; Rizzarelli E.; Sovago I. Metal Loading Capacity of Aβ N-Terminus: a Combined Potentiometric and Spectroscopic Study of Zinc(II) Complexes with Aβ(1–16), Its Short or Mutated Peptide Fragments and Its Polyethylene Glycol-ylated Analogue. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 10405–10415. 10.1021/ic9012334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirah S.; Kozin S. A.; Mazur A. K.; Blond A.; Cheminant M.; Ségalas-Milazzo I.; Debey P.; Rebuffat S. Structural changes of region 1–16 of the Alzheimer disease amyloid β-peptide upon zinc binding and in vitro aging. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 2151–2161. 10.1074/jbc.M504454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaggelli E.; Janicka-Klos A.; Jankowska E.; Kozlowski H.; Migliorini C.; Molteni E.; Valensin D.; Valensin G.; Wieczerzak E. NMR studies of the Zn2+ interactions with rat and human beta-amyloid (1–28) peptides in water-micelle environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 100–109. 10.1021/jp075168m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmard C.; Guilloreau L.; Coppel Y.; Mazarguil H.; Faller P. Amyloid-beta peptide forms monomeric complexes with Cu(II) and Zn(II) prior to aggregation. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 163–165. 10.1002/cbic.200600319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hureau C.; Coppel Y.; Dorlet P.; Solari P. L.; Sayen S.; Guillon E.; Sabater L.; Faller P. Deprotonation of the Asp1-Ala2 Peptide Bond Induces Modification of the Dynamic Copper(II) Environment in the Amyloid-β Peptide near Physiological pH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9522–9525. 10.1002/anie.200904512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousejra-El-Garah F.; Bijani C.; Coppel Y.; Faller P.; Hureau C. Iron(II) Binding to Amyloid-β, the Alzheimer’s Peptide. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 9024–9030. 10.1021/ic201233b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller P.; Hureau C.; La Penna G. Metal Ions and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins and Peptides: From Cu/Zn Amyloid-β to General Principles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2252–2259. 10.1021/ar400293h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hureau C.; Balland V.; Coppel Y.; Solari P. L.; Fonda E.; Faller P. Importance of dynamical processes in the coordination chemistry and redox conversion of copper amyloid-β complexes. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 14, 995–1000. 10.1007/s00775-009-0570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkov P. O.; Kulikova A. A.; Golovin A. V.; Tkachev Y. V.; Archakov A. I.; Kozin S. A.; Makarov A. A. Minimal Zn(2+) binding site of amyloid-β. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, L84–86. 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozin S. A.; Mezentsev Y. V.; Kulikova A. A.; Indeykina M. I.; Golovin A. V.; Ivanov A. S.; Tsvetkov P. O.; Makarov A. A. Zinc-induced dimerization of the amyloid-b metal-binding domain 1–16 is mediated by residues 11–14w. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7, 1053–1055. 10.1039/c0mb00334d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozin S. A.; Zirah S.; Rebuffat S.; Hoa G. H.; Debey P. Zinc binding to Alzheimer’s Abeta(1–16) peptide results in stable soluble complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 285, 959–964. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirah S.; Rebuffat S.; Kozin A.; Debey P.; Fournier F.; Lesage D.; Tabet J.-C. Zinc binding properties of the amyloid fragment Ab(1–16) studied by electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 228, 999–1016. 10.1016/S1387-3806(03)00221-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kulikova A. A.; Tsvetkov P. O.; Indeykina M. I.; Popov I. A.; Zhokhov S. S.; Golovin A. V.; Polshakov V. I.; Kozin S. A.; Nudler E.; Makarov A. A. Phosphorylation of Ser8 promotes zinc-induced dimerization of the amyloid-β metal-binding domain. Mol. BioSyst. 2014, 10, 2590–2596. 10.1039/C4MB00332B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozin S. A.; Kulikova A. A.; Istrate A. N.; Tsvetkov P. O.; Zhokhov S. S.; Mezentsev Y. V.; Kechko O. I.; Ivanov A. S.; Polshakov V. I.; Makarov A. A. The English (H6R) familial Alzheimer’s disease mutation facilitates zinc-induced dimerization of the amyloid-β metal-binding domain. Metallomics 2015, 7, 422–425. 10.1039/C4MT00259H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alies B.; La Penna G.; Sayen S.; Guillon E.; Hureau C.; Faller P. Insights into the Mechanisms of Amyloid Formation of ZnII-Ab11–28: pH-Dependent Zinc Coordination and Overall Charge as Key Parameters for Kinetics and the Structure of ZnII-Ab11–28 Aggregates. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 41, 7897–7902. 10.1021/ic300972j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryde U. Carboxylate binding modes in zinc proteins: A theoretical study. Biophys. J. 1999, 77, 2777–2787. 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77110-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hureau C.; Dorlet P. Coordination of redox active metal ions to the APP protein and to the amyloid-β peptides involved in Alzheimer disease. Part 2: How Cu(II) binding sites depend on changes in the Aβ sequences. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2175–2187. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alies B.; Sasaki I.; Proux O.; Sayen S.; Guillon E.; Faller P.; Hureau C. Zn impacts Cu coordination to Amyloid-ß, the Alzheimer’s peptide, but not the ROS production and the associated cell toxicity. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1214–1216. 10.1039/c2cc38236a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawhar S.; Wirths O.; Bayer T. A. Pyroglutamate Amyloid-β (Aβ): A Hatchet Man in Alzheimer Disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 38825–38832. 10.1074/jbc.R111.288308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenzig D.; Rönicke R.; Cynis H.; Ludwig H. H.; Scheel E.; Reymann K.; Saido T.; Hause G.; Schilling S.; Demuth H. U. N-terminal Pyroglutamate (pGlu) formation of Aβ38 and Aβ40 Enforces Oligomer Formation and Potency to Disrupt Hippocampal LTP. J. Neurochem. 2012, 121, 774–784. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirths O.; Breyhan H.; Cynis H.; Schilling S.; Demuth H. U.; Bayer T. A. Intraneuronal pyroglutamate-Abeta 3–42 triggers neurodegeneration and lethal neurological deficits in a transgenic mouse model. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118, 487–496. 10.1007/s00401-009-0557-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittnam J. L.; Portelius E.; Zetterberg H.; Gustavsson M. K.; Schilling S.; Koch B.; Demuth H. U.; Blennow K.; Wirths O.; Bayer T. A. Pyroglutamate amyloid β (Aβ) aggravates behavioral deficits in transgenic amyloid mouse model for Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 8154–8162. 10.1074/jbc.M111.308601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willem M.; Tahirovic S.; Busche M. A.; Ovsepian S. V.; Chafai M.; Scherazad K.; Hornburg D.; Evans L. D. B.; Moore S.; Daria A.; Hampel H.; Müller V.; Giudici C.; Nuscher B.; Wenninger-Weinzierl A.; Kremmer E.; Heneka M. T.; Thal D. R.; Giedraitis V.; Lannfelt L.; Müller U.; Livesey F. J.; Meissner F.; Herms J.; Konnerth A.; Marie H.; Haass C. η-Secretase processing of APP inhibits neuronal activity in the hippocampus. Nature (London, U. K.) 2015, 256, 443–447. 10.1038/nature14864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portelius E.; Olsson M.; Brinkmalm G.; Rüetschi U.; Mattsson N.; Andreasson U.; Gobom J.; Brinkmalm A.; Hölttä M.; Blennow K.; Zetterberg H. Mass spectrometric characterization of amyloid-β species in the 7PA2 cell model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013, 33, 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proux O.; Biquard X.; Lahera E.; Menthonnex J. J.; Prat A.; Ulrich O.; Soldo Y.; Trévisson P.; Kapoujvan G.; Perroux G.; Taunier P.; Grand D.; Jeantet P.; Deleglise M.; Roux J.-P.; Hazemann J.-L. FAME: A new beamline for X-ray absorption investigations of very-diluted systems of environmental, material and biological interests. Phys. Scr. 2005, 115, 970–973. 10.1238/Physica.Topical.115a00970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proux O.; Nassif V.; Prat A.; Ulrich O.; Lahera E.; Biquard X.; Menthonnex J. J.; Hazemann J.-L. Feedback system of a liquid nitrogen cooled double-crystal monochromator: design and performances. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2006, 13, 59–68. 10.1107/S0909049505037441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado R.; Da Silva J. J. R. F.; Amorim M. T. S.; Cabral M. F.; Chaves S.; Costa J. Dissociation constants of Brempty setnsted acids in D2O and H2O: studies on polyaza and polyoxa-polyaza macrocycles and a general correlation. Anal. Chim. Acta 1991, 245, 271–282. 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)80232-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krezel A.; Bal W. A formula for correlating pKa values determined in D2O and H2O. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2004, 98, 161–166. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.