Abstract

Objectives: To prospectively evaluate (1) pregnancy desirability, (2) stated intentions should pregnancy occur among emergency contraception (EC) users, and (3) explore differences between women selecting the copper T380 intrauterine device (Cu IUD) or oral levonorgestrel (LNG) regarding hypothetical pregnancy plans and actual pregnancy actions during subsequent unintended pregnancies.

Study Design: In this prospective observational trial, women received the Cu IUD or oral LNG for EC without cost barriers. At baseline, participants completed a visual analogue scale measuring pregnancy desirability (anchors: 0, “trying hard not to get pregnant”; 10, “trying hard to get pregnant”) and self-reported plans (abortion, adoption, parenting, and unsure) if the pregnancy test were to come back positive. Pregnancies were tracked for 12 months, and actions regarding unintended pregnancies were compared between EC method groups.

Results: Of 548 enrolled women, 218 chose the Cu IUD and 330 the oral LNG for EC. Pregnancy desirability at baseline was low, with no difference between EC groups (IUD group: 0.51, SD ± 1.60; LNG group: 0.68, SD ± 1.74). Fifty-four (10%) women experienced unintended pregnancies. Pregnancy plans from baseline changed for 27 (50%) women when they became pregnant. EC groups did not differ in hypothetical pregnancy intention (p = 0.15) or in agreement of hypothetical pregnancy intention with actual pregnancy action (p = 0.80).

Conclusions: Women presenting for EC state high desire to prevent pregnancy regardless of method selected. When considering a hypothetical pregnancy, half of women had a plan for how they would respond to that situation, but when confronting an actual unintended pregnancy, half altered their plan. Clinical Trial Registration Number: Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00966771.

Keywords: : pregnancy intentions, emergency contraception, unintended pregnancy

Introduction

Women presenting for emergency contraception (EC) are at high risk of unintended pregnancy over the course of the next year, given that many EC users do not start a reliable method of contraception after receiving EC.1,2 Relative to copper T380 intrauterine device (Cu IUD) EC users, oral levonorgestrel (LNG) EC users are at greater risk of unintended pregnancy, both for the cycle of EC use3 and during the subsequent year.4 Given the disparities in both the effort required to obtain each EC method and the methods' efficacies in preventing unintended pregnancy for the future, there may be interesting differences between these two groups of EC users in their desire to prevent pregnancy and their future actions around a pregnancy should it occur. Research has not adequately addressed these potential differences.

Continuing gestations with an unintended pregnancy are associated with decreased utilization of antenatal care services,5 increased high-risk pregnancy behaviors,6–8 increased rates of preterm birth and low birth weight,9,10 and negative postpartum maternal outcomes.7,11 Although published literature addresses pregnancy continuation after unintended pregnancies, there is a dearth of information regarding factors that influence decision making surrounding the choice to continue an unintended pregnancy. For instance, quantification of a woman's desire to avoid pregnancy and subsequent choice regarding method of EC are lacking. Traditional pregnancy intention measures, including those used in the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), assess pregnancy intention retrospectively and may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias.12

This prospective study provides data regarding associations between EC choice, desire to avoid pregnancy, hypothetical pregnancy intent, and action after unintended pregnancy among women who presented for EC and had a subsequent pregnancy within 1 year. This was a secondary analysis of an observational study that investigated 1-year pregnancy rates for the Cu IUD versus oral LNG for EC.4 Our primary aim for this secondary analysis was to investigate whether baseline desire to avoid pregnancy was correlated with efficacy of EC method choice. We hypothesized that women presenting for EC would have a strong desire to avoid pregnancy and those choosing the most effective EC method would have greater desire to avoid pregnancy. Our secondary aim was to evaluate the agreement of hypothetical pregnancy intention when presenting for EC with actual pregnancy action should an unintended pregnancy occur within 12 months of EC use.

Materials and Methods

This analysis used data collected from a prospective observational study comparing 1-year pregnancy rates among EC users who chose either oral LNG or the Cu IUD. Women aged 18–30 years presenting for EC within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse at two Planned Parenthood Association of Utah (PPAU) clinics in Salt Lake County were invited to participate in the study. Participants were enrolled between November 2009 and July 2010. Exclusion criteria were any documentation of infection with gonorrhea or chlamydia in the 60 days before EC presentation or uterine infection within the past 90 days. Additional information on this study design and methods has been previously described in detail.4

After giving informed consent, participants filled out a survey assessing demographics and prior contraceptive use. We also asked participants about intent to avoid pregnancy using a visual analogue scale (VAS) score with anchors of 0 for “trying hard not to get pregnant” and 10 for “trying hard to get pregnant.” The specific question used with this pregnancy avoidance VAS was “If you had to rate how much you were trying to get pregnant or avoid pregnancy, how would you rate yourself?”

After this question, participants were then asked about their hypothetical pregnancy plans with this question: “If you found out you were pregnant today, would you…?” Response options were as follows:

• Have an abortion

• Keep the child

• Place child for adoption

• Hope for a miscarriage/I am unsure of what I would do

Plans to have an abortion, keep the child, and pursue adoption were considered definitive plans. Hoping for miscarriage and being “unsure of what I would do” were assessed as uncertain plans. After survey completion, participants received their desired method of EC free of charge, and they had been informed at enrollment that there would be no cost for their chosen EC method. If an IUD insertion failed, the participant received oral LNG. We conducted follow-up telephone interviews at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months and asked participants again about whether a pregnancy had occurred, and, if so, to describe the actual action taken during the pregnancy (i.e., actions included abortion, adoption, or parenting). Participants were also asked about any method of anticipatory contraception they were using at that time.

We assigned participants to treatment group using an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and categorized them by their selected method of EC, not by the obtained method. Thus, if a participant requested an IUD but was unable to obtain one because of IUD insertion failure, she was included in the IUD group for analysis. A per-protocol analysis, which grouped women by the EC method they actually received, was also conducted. We used a simple kappa coefficient to measure agreement between hypothetical pregnancy plans and actual actions during subsequent unintended pregnancies. Intended pregnancies were excluded from analysis. We analyzed demographic data and secondary outcomes using chi-squared and Fisher exact tests. All analyses were completed using Stata 13 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Utah (No. 00030937) and Planned Parenthood Federation of America Medical Affairs Department approved this study. We followed STROBE guidelines during study design and article preparation.13

Results

A total of 548 women were enrolled in this study, 218 women (40%) chose the Cu IUD for EC and 330 (60%) chose oral LNG for EC. Six women were withdrawn at baseline because of being in protocol violation based on exclusion criteria. Of women who selected the IUD, there were 42 IUD insertion failures (19%); this higher than expected rate has been addressed in a separate article.14 Thirty-eight women (17%) in the IUD group and 67 women (20%) in the oral LNG group were lost to follow-up, withdrew from the study, or were excluded for protocol violations. Demographics of the original cohort are reported elsewhere.4 Differences in follow-up rates between the two groups were not significant (p = 0.71). Contraceptive use at baseline did not differ between the two EC groups; in each, more than one-third of women were not using any method of contraception when they presented for EC (42% in the oral LNG group and 35% in the IUD group).4 Use of effective anticipatory contraception (defined as use of a method of contraception with a typical use pregnancy rate of less than or equal to 9% per year)15 at 12 months was greater in the IUD group 125/183 (68%) than in the oral LNG group 106/257 (41%) (p < 0.001).

Despite low rates of effective anticipatory contraceptive use at baseline, the mean VAS scores on a 10-point scale for intent to avoid pregnancy were 0.51 (SD ± 1.60) in the IUD group and 0.68 (SD ± 1.74) among women selecting oral LNG; indicating the average participant was “trying hard not to get pregnant.” The desire to avoid pregnancy did not differ by EC method selected (p = 0.25) or by EC method received (p = 0.57).

Data regarding hypothetical pregnancy intention at time of presentation for EC were available for 540/542 participants (99%). About half of the women in each EC group had a definitive pregnancy intention at baseline: 29% IUD versus 33% oral LNG planned to continue the pregnancy and parent, 22% IUD versus 17% oral LNG planned to have an abortion, and 1% IUD versus 4% oral LNG planned to pursue adoption. In both EC groups, nearly half of participants had unsure intentions (47% IUD vs. 46% oral LNG), meaning they were unsure or would hope for a miscarriage. Pregnancy intention did not differ between groups (p = 0.15).

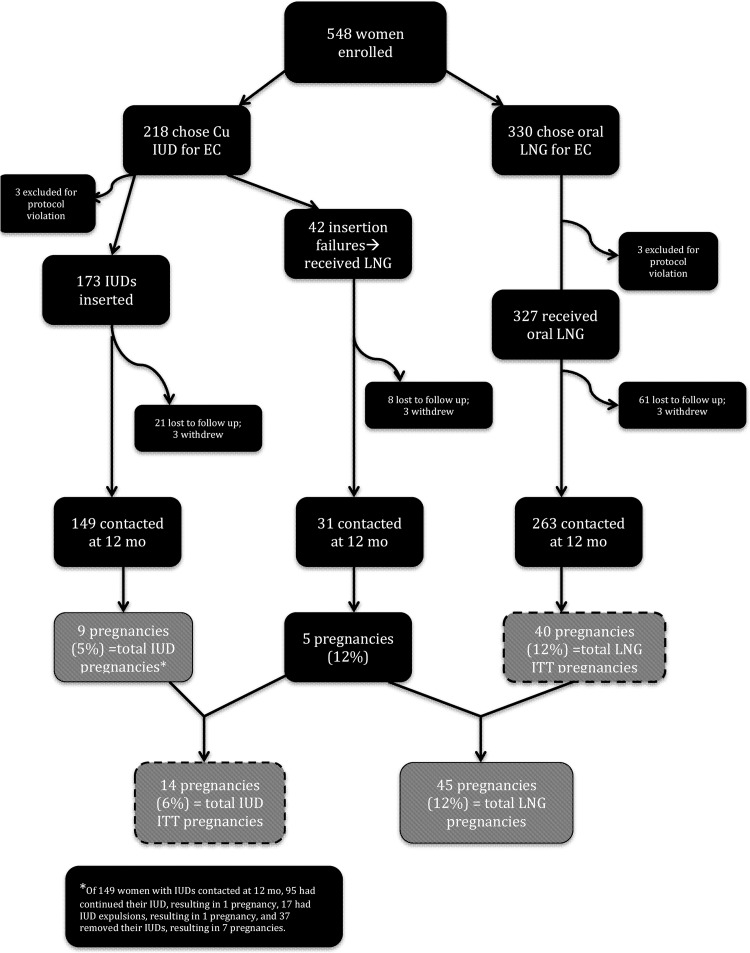

Fifty-six (10.3%) pregnancies were reported within 12 months of presentation for EC; 54 (96%) of these were unintended pregnancies; 14 (6%) pregnancies were in the IUD group and 40 (12%) in the oral LNG group. Among women who chose the IUD, the pregnancies occurred in five women who had IUD insertion failures, one who had an IUD expulsion, seven women who had IUD removals, and one who continued the IUD. The two intended pregnancies were excluded from subsequent analyses. The characteristics of the women who reported an unintended pregnancy were representative of the larger study population. We report the demographics of the participants who experienced unintended pregnancies in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the flow of pregnancy rates in the IUD versus LNG groups, for ITT and for actual treatment received.

Table 1.

Demographics of Women with Unintended Pregnancies Within 1 Year of Presentation for Emergency Contraception

| IUD (n = 14) | Oral LNG (n = 40) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 22.1 ± 3.2 | 22.3 ± 3.4 | 0.86 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 6 (43) | 27 (68) | 0.08 |

| Hispanic | 5 (38) | 11 (28) | |

| Asian American | 1 (7) | 1 (3) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single, never married | 9 (64) | 29 (73) | 0.37 |

| Single, living with partner | 3 (2) | 2 (5) | |

| Married | 2 (14) | 8 (20) | |

| Separated | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Full time | 2 (14) | 7 (18) | 0.88 |

| Part time | 4 (29) | 7 (18) | |

| Student | 6 (43) | 16 (40) | |

| Homemaker | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | |

| Unemployed | 2 (14) | 5 (13) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Income, n (%) | |||

| <$20,000 | 7 (54) | 27 (68) | 0.51 |

| ≥$20,000 | 6 (46) | 13 (33) | |

| Insurance, n (%) | |||

| Private | 6 (43) | 14 (36) | 0.59 |

| Medicaid | 1 (7) | 9 (23) | |

| Uninsured | 7 (50) | 16 (41) | |

| Insurance covers contraception, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2 (15) | 11 (29) | 0.66 |

| No | 6 (46) | 16 (42) | |

| Do not know | 5 (39) | 11 (29) | |

| Nulligravid, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 11 (79) | 12 (30) | 0.002 |

| No | 3 (21) | 28 (70) | |

| Prior abortion, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2 (14) | 9 (23) | 0.71 |

| No | 12 (86) | 31 (78) | |

| Prior STI, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (29) | 9 (23) | 0.72 |

| No | 10 (71) | 31 (78) | |

| Contraceptive method used at time of pregnancy, n (%) | |||

| IUD/implant/sterilization | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.23 |

| Depo | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pill/patch/ring | 1 (7) | 8 (20) | |

| Condom/withdrawal/other | 6 (43) | 21 (53) | |

| None | 6 (43) | 11 (28) | |

Totals may not equal 100% because of rounding.

IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

FIG. 1.

Study flowchart. There were 14 pregnancies overall in the Cu IUD intention-to-treat group and 40 pregnancies in the oral LNG intention-to-treat group. There were 9 pregnancies overall among women who actually received IUDs (i.e., had successful insertions) and 45 pregnancies among women who received oral LNG (i.e., LNG intention-to-treat plus failed IUD insertions). Cu IUD, copper T380 intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel.

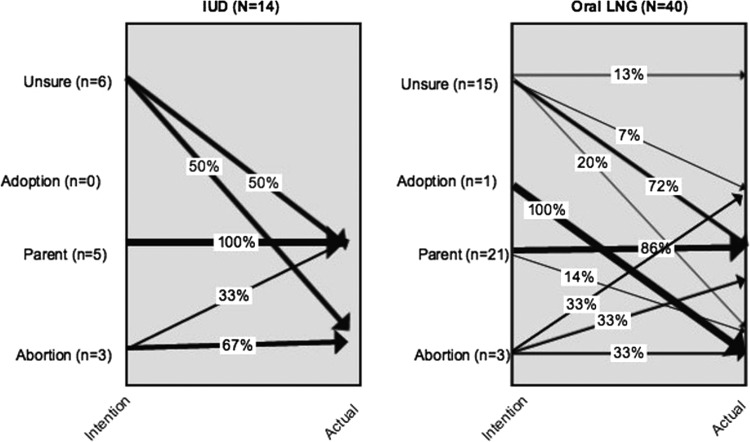

For women who experienced unintended pregnancies, hypothetical pregnancy intention at baseline changed for 27 (50%) women when they were actually pregnant. At the time of enrollment, among the 14 women who selected the IUD for EC and had a subsequent unintended pregnancy, 5 (36%) planned to continue the pregnancy and parent, 3 (21%) planned to have an abortion, no one 0 (0%) was planning on adoption, and 6 (43%) were uncertain of what they would do. Among these 14 women, when subsequent pregnancy occurred, 9 (64%) decided to continue the pregnancy and parent, and 5 (36%) had, or intended to have, an abortion. At enrollment, among the 40 women selecting oral LNG for EC who subsequently had an unintended pregnancy, 21 (53%) intended to parent, 3 (8%) intended to abort, 1 (3%) intended adoption, and 15 (38%) were unsure of what they would do if their baseline pregnancy test came back positive. Among these 40 women, at the time of subsequent unintended pregnancy, 28 (70%) intended to parent, 8 (20%) had, or intended to have, an abortion, 1 (3%) planned an adoption, and 3 (8%) remained unsure about actions. These data are represented in Figure 2.

FIG. 2.

Pregnancy intention versus action by EC selection group Baseline pregnancy intention and action during subsequent unintended pregnancy for patients initially selecting the Cu IUD (n = 14) or oral LNG (n = 40). Percentages are within intention and arrows are weighted to reflect proportions of patients with given action. For example, of the individuals who selected an IUD and were unsure of what they would do if pregnant at baseline, 50% parented and 50% aborted at time of subsequent pregnancy. EC, emergency contraception.

There were no differences between the groups in either baseline intentions (p = 0.416) or subsequent actions (p = 0.473). In the IUD group, 7/14 women (50%) had concordance between their baseline pregnancy intentions and actual decision for the action taken during subsequent unintended pregnancy (kappa = 0.28). This was similar to the oral LNG group, in which 21/40 (53%) had concordance between their baseline pregnancy intentions and actual decision for the action during subsequent unintended pregnancy (kappa = 0.21). The test for equal kappa coefficients between groups was not rejected (p = 0.80), indicating no significant difference between the IUD and oral LNG groups with regard to concordance of baseline pregnancy intentions and actions for subsequent unintended pregnancy.

Discussion

These data illustrate the complex and dynamic nature of decision making surrounding unintended pregnancy. Associations did not exist between degree of desire to avoid pregnancy and choice of a more effective EC method, even when cost barriers were completely removed. Correlations did not exist between effective method choice and hypothetical pregnancy intention. There were no differences between EC method selection (or actual type of EC received) and pregnancy intention to action concordance.

These data, which indicate that a woman's desire to become pregnant does not necessarily predict her chosen method of EC or contraception, support a recent qualitative study of pregnancy intention among low-income women, which similarly found a poor correlation between pregnancy intention and contraceptive behavior.16 In addition, a study among privately insured women found that when cost barriers were removed, pregnancy risk exposure (which the researchers determined based on partnership type and frequency of sexual intercourse) was a better predictor of choice of contraception than was pregnancy intention (which the researchers defined as the amalgamation of the time frame in which women want to avoid pregnancy and how strongly women want to avoid pregnancy).17

Contraceptive counseling can perhaps improve the divergence between a strong desire to avoid pregnancy and the hesitancy to choose the Cu IUD for EC despite its short- and long-term efficacy. A qualitative study revealed that many women declining IUD placement for EC did so because they were not in a “long-term” relationship and thus did not feel that they needed “long acting” contraception.18 Although the emotional and time-sensitive nature of EC counseling presents additional challenges, it is probable that reframing EC counseling to focus on pregnancy prevention rather than duration of use could increase Cu IUD uptake. First, when counseling patients, providers must keep in mind that a variety of factors, in addition to effectiveness, influence a woman's choice of contraception.19 Second, presenting for EC may feel urgent and emotionally charged, and it is possible that at this time women are less likely to prioritize long-term pregnancy prevention. Third, considering a hypothetical pregnancy is a very different situation than responding to an actual pregnancy. It is important for clinicians to keep in mind that actions may change from hypothetical pregnancy plans and counsel patients with a full range of options regardless of previously stated plans.20

The main strength of this study lies in prospective query of hypothetical pregnancy plans before confirmed positive pregnancy test. This methodology allows for evaluation of intention, which is not subject to recall bias. In addition, providing quantification of degree of desire to avoid pregnancy provides novel data regarding factors affecting EC method choice. In addition to the prospective study design, other strengths include the large sample size and high 1-year follow-up rate.

The major limitation to this study is that intentions asked at baseline may not equal intention over the course of the year, and participants were only asked about their intentions at baseline. Furthermore, pregnancy intention is a fluid concept, which can be difficult to quantify and correlate with subsequent actions.21,22 Challenges in assessing fluidity of pregnancy intention and ambivalence also plague traditional pregnancy intention measures, such as those used in the NSFG and PRAMS.12,21 The lack of association between desire to prevent pregnancy and method chosen may also be the result of using a simple tool to assess a complex issue. The VAS score provides the advantage of querying individuals before knowing their pregnancy status, but lacks measures shown to increase understanding of intention such as multiple questions, queries of male intentions, and answers allowing for overt ambiguity.23–25 Finally, the low absolute numbers of pregnancies in our sample size limit our abilities to make final assessments, particularly when divided among different categories.

Despite these limitations, our analysis provides novel insight and data regarding the complex nature of EC choice and decision making in response to unintended pregnancy. Although EC users report a high intent to avoid pregnancy, their hypothetical pregnancy intentions do not necessarily predict how they will respond if pregnant. Further studies should explore the decision-making processes that women (both those presenting for EC and those desiring contraceptive care more generally) undergo when confronted with unintended pregnancies. Although women presenting for EC are clear in their desire to prevent pregnancy at that moment, future decision making regarding prevention or pursuit of pregnancy is complex and dynamic. The variability between stated hypothetical pregnancy intentions at the time presenting for EC and actions around subsequent pregnancies suggests that patient conversations around contraception selection should avoid this theoretical construct and target other benefits of contraceptive use.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the trial participants and the staff at Planned Parenthood Association of Utah who made this study possible. In particular we would like to acknowledge the efforts of Kathy Burke and Penny Davies. We would also like to thank Vineela Maddukuri, Janet Jacobson, Shawn Gurtcheff, and Marie Flores for their contributions to the study during early development. The findings and conclusions of this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc.

Funding

This project was supported by grants from the Society of Family Planning, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (R21HD063028), and the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistic Center, with funding from the Public Health Services research grant: UL1-RR025764 and the National center for Research Resources grant: C06-RR11234. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD or the NIH. The copper IUDs and oral levonorgestrel (Plan B One Step) were supplied by Duramed Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the U.S. distributor of both products at the time the study was initiated.

Author Disclosure Statement

The University of Utah Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology receives research support from Bayer Women's Health, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Medicines 360, Veracept and Bioceptive. D.K.T. receives speaking honoraria from Allergan and Medicines360 and has served as a consultant for Bioceptive, and on advisory boards for Actavis, Pharmanest, Teva, and Bayer. The other authors report no conflict of interest. For all other authors, no competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Raine-Bennett T, Merchant M, Sinclair F, Lee JW, Goler N. Reproductive health outcomes of insured adolescent and adult women who access oral levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:904–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ESHRE Capriworkshop Group. Emergency contraception. Widely available and effective but disappointing as a public health intervention: A review. Hum Reprod 2015;30:751–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: A systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1994–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turok DK, Jacobson JC, Dermish AI, et al. Emergency contraception with a copper IUD or oral levonorgestrel: An observational study of 1-year pregnancy rates. Contraception 2014;89:222–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dibaba Y, Fantahun M, Hindin MJ. The effects of pregnancy intention on the use of antenatal care services: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health 2013;10:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orr ST, James SA, Reiter JP. Unintended pregnancy and prenatal behaviors among urban, black women in Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore preterm birth study. Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception 2009;79:194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCrory C, McNally S. The effect of pregnancy intention on maternal prenatal behaviours and parent and child health: Results of an irish cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013;27:208–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah PS, Balkhair T, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Scott F, Frick C. Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: A systematic review. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kost K, Lindberg L. Pregnancy intentions, maternal behaviors, and infant health: Investigating relationships with new measures and propensity score analysis. Demography 2015;52:83–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercier RJ, Garrett J, Thorp J, Siega-Riz AM. Pregnancy intention and postpartum depression: Secondary data analysis from a prospective cohort. BJOG 2013;120:1116–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, et al. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2003;35:94–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.STROBE Statement: Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology, 2007. Available at: www.strobe-statement.org/?id=available-checklists (accessed July15, 2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Dermish AI, Turok DK, Jacobson JC, Flores ME, McFadden M, Burke K. Failed IUD insertions in community practice: An under-recognized problem? Contraception 2013;87:182–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatcher R. Contraceptive technology. 20th rev. ed. New York, NY: Ardent Media, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, et al. “It just happens”: A qualitative study exploring low-income women's perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception 2015;91:150–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisman CS, Lehman EB, Legro RS, Velott DL, Chuang CH. How do pregnancy intentions affect contraceptive choices when cost is not a factor? A study of privately insured women. Contraception 2015;92:501–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright RL, Frost CJ, Turok DK. A qualitative exploration of emergency contraception users' willingness to select the copper IUD. Contraception 2012;85:32–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bharadwaj P, Saxton JC, Mann SN, Jungmann EM, Stephenson JM. What influences young women to choose between the emergency contraceptive pill and an intrauterine device? A qualitative study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2011;16:201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollak KI, Coffman CJ, Alexander SC, et al. Can physicians accurately predict which patients will lose weight, improve nutrition and increase physical activity? Fam Pract 2012;29:553–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zabin LS. Ambivalent feelings about parenthood may lead to inconsistent contraceptive use—and pregnancy. Fam Plann Perspect 1999;31:250–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klerman LV. The intendedness of pregnancy: A concept in transition. Matern Child Health J 2000;4:155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheeder J, Teal SB, Crane LA, Stevens-Simon C. Adolescent childbearing ambivalence: Is it the sum of its parts? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2010;23:86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kavanaugh ML, Schwarz EB. Prospective assessment of pregnancy intentions using a single- versus a multi-item measure. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2009;41:238–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett G, Smith SC, Wellings K. Conceptualisation, development, and evaluation of a measure of unplanned pregnancy. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:426–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]