Abstract

Background:

The frequency and the perceived intensity of life stressors, coping strategies, and social supports are very important in everybody's well-being. This study intended to estimate the relation of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and these factors.

Materials and Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study carried out in Isfahan on 2013. Data were extracted from the framework of the study on the epidemiology of psychological, alimentary health, and nutrition. Symptoms of IBS were evaluated by Talley bowel disease questionnaire. Stressful life event, modified COPE scale, and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support were also used. About 4763 subjects were completed questionnaires. Analyzing data were done by t-test and multivariate logistic regression.

Results:

Of all returned questionnaire, 1024 (21.5%) were diagnosed with IBS. IBS and clinically-significant IBS (IBS-S) groups have significantly experienced a higher level of perceived intensity of stressors and had a higher frequency of stressors. The mean score of social supports and the mean scores of three coping strategies (problem engagement, support seeking, and positive reinterpretation and growth) were significantly lower in subjects with either IBS-S or IBS than in those with no IBS. Multivariate logistic regression revealed a significant association between frequency of stressors and perceived intensity of stressors with IBS (odds ratio [OR] =1.09 and OR = 1.02, respectively) or IBS-S (OR = 1.09 and OR = 1.03, respectively).

Conclusions:

People with IBS had higher numbers of stressors, higher perception of the intensity of stressors, less adaptive coping strategies, and less social supports which should be focused in psychosocial interventions.

Keywords: Coping strategies, irritable bowel syndrome, life stressors, social support

INTRODUCTION

General practitioners, family physicians, and gastroenterologists regularly visit patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in their clinical practice.[1] Several factors influence on the brain-gut biopsychosocial interaction which is necessary for IBS development. An important part of this picture involves the interactions of life stressors, coping strategies, and social supports which influence gastrointestinal functions, perception of IBS symptoms, and its expression.[1] Noticeable difficulties in personal interrelationships are more commonly reported by IBS patients than in patients with organic gastrointestinal disorders.[2] Studies revealed that high loads of daily or emotional stressors predispose IBS from nonpatient to patient status[3] and exacerbate the severity of symptoms.[4,5]

Coping strategies are “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and internal demands that are appraised as exceeding the resources of person.”[6] The responses of IBS patients to handle negative emotions induced by stressful situations seem to be different than the responses of healthy controls and patients with organic diseases.[5] For example, some studies showed highly emotional-oriented coping strategies among IBS patients.[6,7] Another investigation demonstrated very low levels of positive reappraisal and the ability to control the symptoms in these patients.[8] Different studies on coping and IBS were not in general agreement, and further investigations are required.

When the patients feel inadequate social supports, their immune system functions are altered,[9,10,11,12,13] whereas when feel adequate social supports, they respond better to stressors and their immune system functions are improved.[14,15] This process is more prominent in patients with IBS because of the inflammatory background of disease.[16] Then, social supports of family, friends, relationships, and networks lessen the effects of stressors on patients with IBS while unsatisfactory social supports intensify the severity of symptoms.[16,17,18] Psychological factors are potentially efficacious in treating IBS in many patients, and unlike many pharmaceutical treatments, they have minimal side effects and can be cost-effective.[19] Assessment of life stressors, coping strategies, and social supports and their initiation chance to IBS in a large sample of the general population might help us a better understanding of the proper management of patients with IBS. The current study intended to examine the initiation of the psychosocial characteristic in IBS in an Iranian university-based community.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This project was a cross-sectional study. The data were extracted from the framework of the study on the epidemiology of psychological, alimentary health, and nutrition (SEPAHAN), on 2013. SEPAHAN showed the epidemiological image of functional gastrointestinal disorders and their relation with psychological factors and lifestyle on 2010.[20] The SEPAHAN research was designed as follows: The population was selected among about 10,500 nonacademic healthy staff working of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in fifty different centers across Isfahan province. Subjects who were ≥18 years old, willing to comply with the study protocol, and provided written informed consent were selected. The presence of any psychiatric or medical condition that needs long time drug consumption was unmet criteria. Participating was optional and the response rate was 86.16%. Finally, the data of 4763 people who had completed information was used. Four standard self-administered questionnaires were used. In order to increase the awareness and enhance the contribution of the study, group in the study, posters, brochures, and letters were used. They contained information on the goals of the research and the study design. The questionnaires were filled out individually. The detailed information about this survey has already been published.[20]

Confident extraction of the data in short time with the least possible errors was done by optical mark recognition. Individual health profiles were ready by July 2012. The Medical Research Ethics Committee (project number, 189069, 189082, and 189086) approved the study. All subjects signed written consent form. Principal investigator continuously monitored various parts of the study.

Variable assessment

The presence of symptoms of IBS was assessed by Talley bowel disease questionnaire.[21] Rome III criteria were applied to define the disorders.[22] Those patients who reported “always” or “often” having pain or discomfort were categorized as clinically-significant IBS (IBS-S).[1]

Stressful life event (SLE) questionnaire was employed to assess the frequency and the perceived intensity of various life stressors. The questionnaire's 46 items covered 11 stress domains as follow: Home life, financial problems, social relations, personal conflicts, job conflicts, educational concerns, job security, loss and separation, sexual life, daily life, and health concerns. Each item was scored by 5-point Likert scales (never = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, severe = 3, and very severe = 4). Total perceived intensity of stressors was indicated by total intensity score. Higher scores denoted higher perception of stress intensity. Moreover, the frequency of each stressor and the total stress frequency were determined.[23,24]

Modified COPE scale was used to evaluate coping strategies employed to cope with SLEs. This is a multicomponent self-administered coping strategies questionnaire.[25] It included 23 items subdivided into five subscales as follow: Positive reinterpretation and growth, problem engagement, acceptance, seeking support, and avoidance. The reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α = 0.84). Each question was scored by 3-point Likert scales (never = 0, sometimes = 1, and often = 2). Higher scores specified the more frequent use of the related coping strategies.[26]

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support was applied to estimate various social employed by participants.[27] It included 12 items with 3-point Likert scales (never = 0, sometimes = 1, and often = 2) and evaluated the sufficiency of social support received from three sources: Family, friends, and significant others. Each source was assessed by four items. Higher scores demonstrated higher levels of received social support. The Persian validated version of questioner was used.[28]

Statistical analysis

To analyze the data, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used. Two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered significant. Continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviation [SD]) and were analyzed by t-test. The prevalence of IBS-S and IBS according to life stressors, coping strategies, and social supports were computed.

The relationships of IBS-S and IBS with various variables such as age, sex, education, marital status, life stressors, coping strategies, and social supports were assessed. The crude effects of each variable on IBS-S and IBS were studied by univariate logistic regression analysis. Indices of life stressors included total frequency of life stressors and mean scores of perceived intensity of life stressors. Total score of social support was applied as the index of all social supports. Various types of coping strategies were studied separately.

The questioners with more than 10% missing data were omitted from analysis. The relative contributions of stressors, social support, coping, age, sex, marital status, and educational level in IBS patients were studied by multivariate regression analyses in two models. Model 1 included the total frequency of life stressors, total score of social support, different types of coping strategies and age, sex, marital status, and education. Model 2 included a mean score of perceived intensity of life stressors, total score of social support, different types of coping strategies and age, sex, marital status, and education. The odds ratios (ORs) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated in the logistic regression analysis. The ORs (95% CI) >1 denotes that the people with the corresponding variable (s) are more likely to suffer from IBS. The ORs (95% CI) <1 denotes that the people with the corresponding variable (s) are less likely to suffer from IBS. The 5% significance level was considered for exclusion from the model.

RESULTS

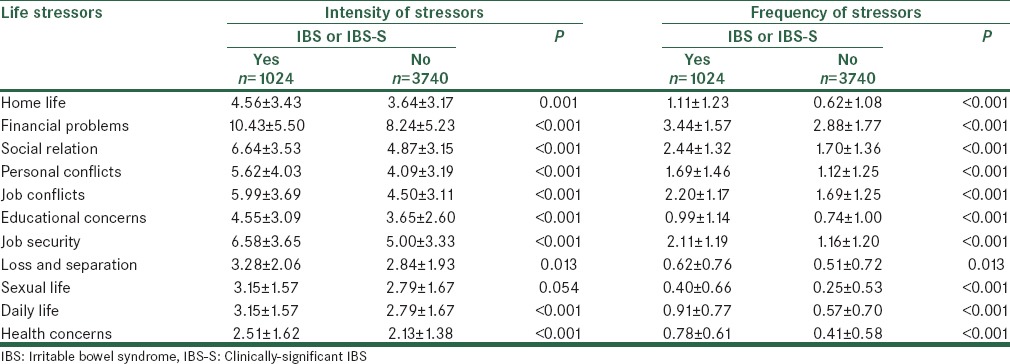

Of all participants, 1024 (21.5%) demonstrated IBS and the female:male ratio was 1.3 and 276 (5.8%) had IBS-S with a female:male ratio of 2. Table 1 shows the perceived intensity and the frequency of each life stressor in the two groups of patients with IBS and IBS-S and in subjects with no IBS or IBS-S. The frequencies of stressors in subjects with either IBS or IBS-S in all items of SLE questionnaire were significantly more common than in subjects with no IBS or IBS-S (P < 0.05), [Table 1]. ten out of 11 evaluated stress domains in SLE questionnaire revealed significantly higher mean scores of perceived intensity in patients with either IBS or IBS-S versus no IBS or IBS-S (P < 0.05), [Table 1].

Table 1.

The differences in the frequency and in the perceived intensity of life stressors between the patients with IBS or IBS-S versus those with no IBS or IBS-S

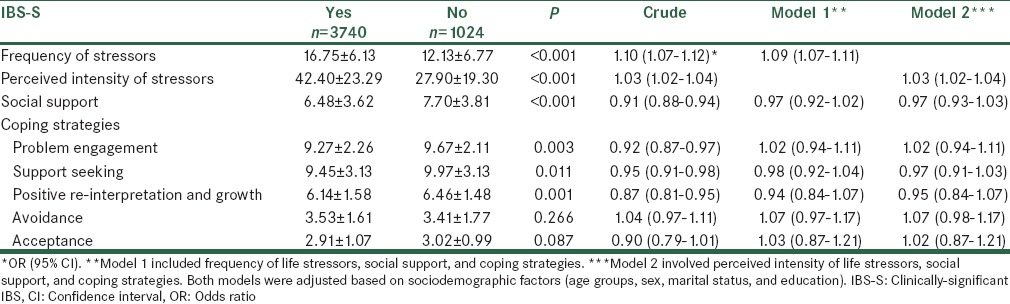

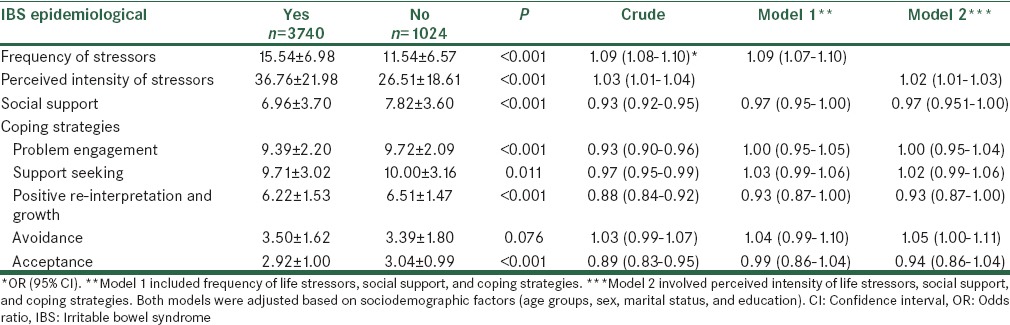

Table 2 demonstrates the mean scores of all stressors together, social supports, and coping strategies in patients with IBS-S versus subjects with no IBS-S and Table 3 demonstrates the mean scores of all stressors together, social supports, and coping strategies in patients with IBS versus subjects with no IBS. Mean (SD) frequency of all stressors together in SLE questionnaire was significantly higher in patients with IBS-S or IBS than that in people with no IBS-S or IBS, respectively [Tables 2 and 3]. Mean (SD) perceived intensity score of all stressors together was also significantly higher in cases with IBS-S or IBS than that in subjects with no IBS-S or IBS, respectively [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Comparison of mean scores of stressors, social supports, and coping strategies in patients with IBS-S versus those with no IBS-S and logistic regression analyses demonstrating the crude and adjusted effects of these variables on IBS-S

Table 3.

Comparison of mean scores of stressors, social supports, and coping strategies in patients with irritable bowel syndrome versus those with no irritable bowel syndrome

The results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses in patients with IBS-S are summarized in Table 2. Univariate analyses revealed a significant association of all independent variables with IBS-S but avoidance and acceptance coping strategies. Model 1 and 2 showed significant associations of the frequency of stressors 1.09 (1.07–1.11) (ORs with 95% CI) and the perceived intensity of stressors 1.03 (1.02–1.04) with IBS-S, respectively. Social supports and coping strategies had no significant association with IBS-S in either model.

The findings of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses in subjects with IBS are presented in Table 3. Univariate analyses demonstrated a significant association of all independent variables with IBS but avoidance coping strategy. Similar to IBS-S, the frequency of stressors and the perceived intensity of stressors showed a significant relationship with IBS in Model 1 and Model 2, 1.09 (1.07–1.10), 1.02 (1.01–1.03) (ORs with 95% CI), respectively. Moreover, both models revealed no significant relationship between any coping strategy or social supports with IBS.

DISCUSSION

Estimates for the prevalence of IBS vary between 4% and 31% internationally. The rate of about 21% in our population is near to the USA, UK, and some other countries.[29] In the current study, the dimensions of various life stressors including their frequencies and perceived intensities were evaluated, and their relationships with IBS and IBS-S were assessed. It was demonstrated that subjects with IBS or IBS-S had statistically and clinically significant higher stress levels, less social support, and less adaptive coping strategies versus non-IBS or non-IBS-S subjects. This factors, lowers the compliance with health care, increase depressive effect, reduce the quality of life, and limit the access to the health care system.[30,31,32,33,34] The imbalance between life stressors, coping strategies, and social supports in patients with IBS was similarly found by other investigations.[3,4,7,16,35,36,37] Fujii and Nomura in a study with 105 sample showed that stressors and copy styles are predictive factors which may result in the incidence of clinical IBS.[3] This is in consistent with our results that showed this factors are more prevalent in patients with IBS. Surdea-Blaga et al. showed that SLEs are involved in the onset of IBS. They revealed that major life events such as death or illness of a parent, seeing someone being murdered, having a person in the family with a psychiatric illness and failing to be understood by parents were more frequently in IBS subjects than in healthy controls.[7] Our results also showed that frequency of life stressors was more in IBS subjects. Jones et al. in a study with 177 subjects revealed that IBS patients have less interpersonal support than control people. Moreover, control group showed better problem solving as a coping strategy than patients with IBS, who relied significantly less on problem-solving and more on escape-avoidance strategies.[16] In consistent with this study, we showed that IBS patients have less social support and less adaptive coping styles.

Although social support and three coping factors of problem engagement, support seeking, and positive reinterpretation and growth had significant relationships with IBS and IBS-S in univariate analyses, when they were added into the regression equation in the hierarchical analysis of the total population, they failed to illuminate the variance on adjustment beyond the 0.05 significance level. In other words, IBS and IBS-S were more strongly associated with perceived intensity of stressors and frequency of stressors compared with social support and coping strategies. This meant that in clinical practice of IBS management, more efficient approach must be taken toward altering the stress appraisal by these patients. Then, clinical management of IBS as a bio-psycho-social disease needs more active approaches such as involvement of family members and intimate others to find out potential stressors, to provoke further support, to educate them sufficiently, and to refer to family therapists.[35,36,37]

The main limitations of the present study were as follow: First, all participants were recruited from the subjects of a single large medical university. Then, the findings are restricted to this special population and may not be generalized to the whole population and more importantly to clinical setting. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the present study made it impossible to draw the definite conclusions about the temporal relationships recorded between IBS and the frequency and perceived intensity of stressors, coping strategies and social supports. Third, IBS diagnosis was based on questionnaire and no clinical visit was applied to further confirm the diagnosis. Additional investigations with prospective design will help more closely evaluate the temporal relationships of IBS and the above-mentioned variables. More effective therapeutic approaches require the better perception of these relationships.

CONCLUSION

The current study's findings were in agreement with other studies showing that people with IBS had a higher perception of intensity of stressors, higher numbers of stressors, less adaptive coping strategies, and less social supports. These files need to be focused on psychosocial interventions in IBS patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by Psychosomatic Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Psychosomatic Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences who supported this work and also all staff of IUMS who participated in our study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, et al., editors. The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006. p. 943. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creed F, Craig T, Farmer R. Functional abdominal pain, psychiatric illness, and life events. Gut. 1988;29:235–42. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujii Y, Nomura S. A prospective study of the psychobehavioral factors responsible for a change from non-patient irritable bowel syndrome to IBS patient status. Biopsychosoc Med. 2008;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palsson OS, Drossman DA. Psychiatric and psychological dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome and the role of psychological treatments. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:281–303. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang L, Lee OY, Naliboff B, Schmulson M, Mayer EA. Sensation of bloating and visible abdominal distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3341–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:571–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surdea-Blaga T, Baban A, Dumitrascu DL. Psychosocial determinants of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:616–26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i7.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li Z, Keefe F, Hu YJ, Toomey TC. Effects of coping on health outcome among women with gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:309–17. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen AN, Hammen C, Henry RM, Daley SE. Effects of stress and social support on recurrence in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:143–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Fisher LD, Ogrocki P, Stout JC, Speicher CE, Glaser R. Marital quality, marital disruption, and immune function. Psychosom Med. 1987;49:13–34. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, Treanor JJ. Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychol. 2005;24:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas PD, Goodwin JM, Goodwin JS. Effect of social support on stress-related changes in cholesterol level, uric acid level, and immune function in an elderly sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:735–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright RJ, Finn P, Contreras JP, Cohen S, Wright RO, Staudenmayer J, et al. Chronic caregiver stress and IgE expression, allergen-induced proliferation, and cytokine profiles in a birth cohort predisposed to atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1051–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller GE, Cohen S, Ritchey AK. Chronic psychological stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: A glucocorticoid-resistance model. Health Psychol. 2002;21:531–41. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones MP, Wessinger S, Crowell MD. Coping strategies and interpersonal support in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:474–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkman LF. Assessing the physical health effects of social networks and social support. Annu Rev Public Health. 1984;5:413–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.05.050184.002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drossman DA, Creed FH, Olden KW, Svedlund J, Toner BB, Whitehead WE. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II25–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altayar O, Sharma V, Prokop LJ, Sood A, Murad MH. Psychological therapies in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2015. 2015:549308. doi: 10.1155/2015/549308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adibi P, Keshteli AH, Esmaillzadeh A, Afshar H, Roohafza HR, Bagherian-sararoudi R, et al. The study on the epidemiology of psychological, alimentary health and nutrition (SEPAHAN): Overview of methodology. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:S291–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., rd Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: The bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1456–79. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: New standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roohafza H, Ramezani M, Sadeghi M, Shahnam M, Zolfagari B, Sarafzadegan N. Development and validation of the stressful life event questionnaire. Int J Public Health. 2011;56:441–8. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sali R, Roohafza H, Sadeghi M, Andalib E, Shavandi H, Sarrafzadegan N. Validation of the revised stressful life event questionnaire using a hybrid model of genetic algorithm and artificial neural networks. Comput Math Methods Med 2013. 2013:601640. doi: 10.1155/2013/601640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–83. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roohafza HR, Afshar H, Keshteli AH, Mohammadi N, Feizi A, Taslimi M, et al. What's the role of perceived social support and coping styles in depression and anxiety? J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:944–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:610–7. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagherian-Sararoudi R, Hajian A, Ehsan HB, Sarafraz MR, Zimet GD. Psychometric properties of the persian version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:1277–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:71–80. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alemi F, Stephens R, Llorens S, Schaefer D, Nemes S, Arendt R. The Orientation of Social Support measure. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1285–98. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grassi L, Rasconi G, Pedriali A, Corridoni A, Bevilacqua M. Social support and psychological distress in primary care attenders. Ferrara SIMG Group. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:95–100. doi: 10.1159/000012372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hefner J, Eisenberg D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:491–9. doi: 10.1037/a0016918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karukivi M, Joukamaa M, Hautala L, Kaleva O, Haapasalo-Pesu KM, Liuksila PR, et al. Does perceived social support and parental attitude relate to alexithymia?. A study in Finnish late adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabinovitch M, Cassidy C, Schmitz N, Joober R, Malla A. The influence of perceived social support on medication adherence in first-episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:59–65. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerson CD, Gerson J, Gerson MJ. Group hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome with long-term follow-up. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2013;61:38–54. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2012.700620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerson MJ, Gerson CD. The importance of relationships in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A review. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012. 2012:157340. doi: 10.1155/2012/157340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerson MJ, Gerson CD, Awad RA, Dancey C, Poitras P, Porcelli P, et al. An international study of irritable bowel syndrome: Family relationships and mind-body attributions. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2838–47. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]