Abstract

Introduction:

The increasing use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) cytology to examine pancreatic neoplasms has led to an increase in the diagnosis of metastases to the pancreas. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common metastasis to the pancreas. Our study examines 33 cases of metastatic RCC to the pancreas sampled by EUS-FNA from four large tertiary care hospitals.

Materials and Methods:

We searched the cytopathology database for RCC metastatic to the pancreas diagnosed by EUS-FNA from January 2005 to January 2015. Patient age, history of RCC, nephrectomy history, follow-up postnephrectomy, radiological impression, and EUS-FNA cytologic diagnosis were reviewed.

Results:

Thirty-three patients were identified. The average age was 67.5 years (range, 49–84 years). Thirty-two patients had a previous documented history of RCC. One patient had the diagnosis of pancreatic metastasis at the same time of the kidney biopsy. Thirty-one patients had been treated with nephrectomy. Twenty-seven patients were being monitored annually by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Twenty-five patients had multiple masses by imaging, but 8 patients had a single mass in the pancreas at the time of EUS-FNA. EUS-FNA of 20 cases showed classic morphology of RCC. Thirteen cases had either “atypical” clinical-radiologic features or morphologic overlaps with primary pancreatic neoplasms or other neoplasms. Cell blocks were made on all 13 cases and immunochemical stains confirmed the diagnosis.

Conclusions:

EUS-FNA cytology is useful for the diagnosis of metastatic RCC to the pancreas. Cytomorphology can be aided with patient history, imaging analyses, cell blocks, and immunochemical stains.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound, fine needle aspiration cytology, metastatic tumors, pancreas, renal cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic metastases from other primary sites are uncommon and account for only 2% of pancreatic malignancies.[1,2,3,4,5] Nevertheless, a wide range of malignant neoplasms has been found to metastasize to the pancreas.[6,7,8,9,10] Among these, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common metastasis to the pancreas.[10,11,12]

Pancreatic metastases are often asymptomatic.[3] Due to the increasing use of imaging modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), pancreatic metastases are often detected during surveillance after resection of the primary tumor or as an incidental finding during a work-up for an unrelated condition.[13,14,15] Although the most common presentation of pancreatic metastases is that of a widespread disease, some patients do present with a single potentially resectable pancreatic mass.[10] Furthermore, metastatic RCC to the pancreas usually appears as hypervascular lesions on CT/MRI and may often mimic primary pancreatic tumors, such as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs). Thus, the accurate diagnosis of a metastatic RCC is important for clinical management.[15]

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) cytology is widely used to evaluate solid and cystic pancreatic lesions preoperatively.[16] EUS-FNA cytology has been shown to be accurate in diagnosing pancreatic metastases.[6,7,8,9,10,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] However, current literature regarding EUS-FNA cytology of metastatic RCC to the pancreas is limited with mostly case reports or small case series.[11,24,25,26,27] Therefore, we studied a large series of metastatic RCC to the pancreas diagnosed by EUS-FNA cytology from four academic tertiary medical centers. We evaluated sonographic characteristics and cytologic features to determine if EUS-FNA cytology is an accurate tool to diagnose metastatic RCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Institutional review board approval was obtained. A computer-based search was used to retrieve cases with the natural language containing metastatic RCC to the pancreas by EUS-FNA. The inclusion criteria were patients with EUS-FNA diagnoses of metastatic RCC, and the imaging results and cytology materials were available for review. We included cases from the Cleveland Clinic and Mayo Clinics (Arizona, Florida, and Rochester) between January 2005 and January 2015.

Patients’ demographic data, clinical symptoms, and imaging features, including CT, MRI, and EUS were obtained from the electronic medical record. The time between the diagnosis of the primary tumor and the initial pancreatic metastasis, the focality, and the imaging characteristics were collected. Slides of EUS-FNA cytology and surgical pathology were reviewed. The EUS-FNA cytology slides included smears with Papanicolaou and/or Diff-Quick stains (Thermo Fisher Scientific Corp. Kalamazoo, MI, USA), liquid-based cytology (ThinPrep, Hologic Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA), cell block with hematoxylin and eosin stain, and immunochemical stained slides. The results of EUS-FNA, immunochemical stains, and the histologic subtypes of RCC were collated.

RESULTS

EUS-FNA of the pancreas was performed 4655 times among the four institutions during the study period. Thirty-three patients with metastatic RCC to the pancreas were identified. They had a mean age of 67.5 (range, 49–84 years) and there were 12 women and 21 men. Thirty-two of the 33 patients had previously diagnosed RCC. One patient had a concurrent RCC (diagnosed by kidney biopsy) when the pancreatic metastasis was identified on imaging. Thirty-one patients had been treated with nephrectomy. One patient was treated medically after metastatic disease was also documented to the bone and lung. Another patient had prior metastasis to the brain and lung. Four patients had subsequent metastasis to other organs: Liver and lung (2), liver (1), and stomach and thyroid (1).

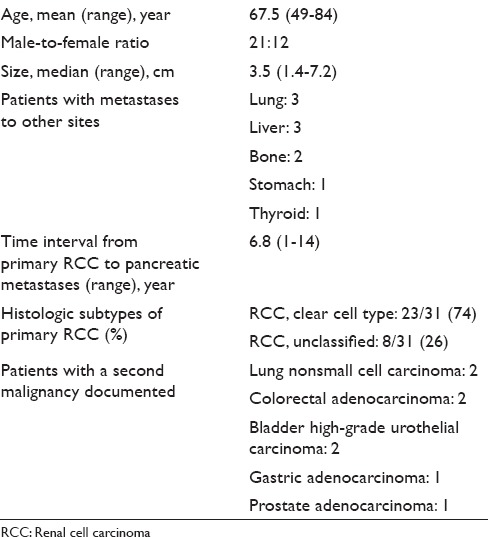

Besides RCC, 8 patients also had documented history of lung, gastrointestinal, bladder, or prostate carcinomas. Of the 31 patients who underwent nephrectomy, 23 patients had histologically confirmed clear cell RCC and 8 patients had RCC, unclassified. The mean time interval between nephrectomy for primary RCC and the presentation of pancreatic metastases was 6.8 years with a standard deviation of 5.3 years. Demographic, clinical, surgical pathology characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patients’ demographic, clinical, and surgical pathology characteristics for metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas

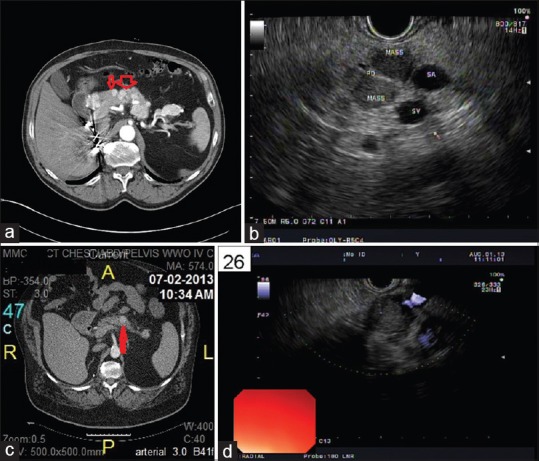

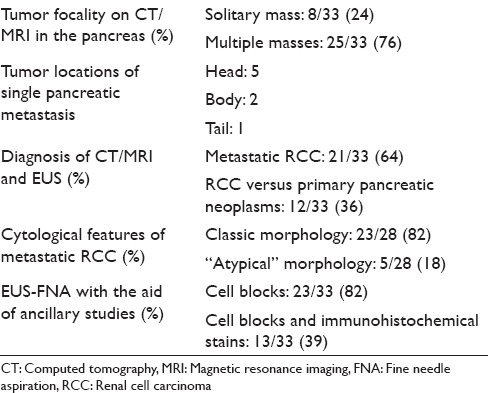

Twenty-seven of the 33 patients were monitored annually by cross-sectional imaging studies including CT and/or MRI. At the time of detection of pancreatic metastases, 22 (66%) had imaging impression of widespread metastatic diseases, while 11 patients (34%) had isolated pancreatic metastases by imaging. Of the 33 patients with pancreatic metastases of RCC, 25 patients (76%) had multiple masses throughout the pancreas and 8 patients (24%) had single mass in the pancreas. Of the isolated pancreatic metastasis of RCC (n = 8), 5 (63%) were in the head, 2 (25%) in the body, and 1 (13%) in the tail. On contrast enhanced CT/MRI, most of the RCC metastases (30/33) were hypervascular and demonstrated intense enhancement on arterial and venous phase images, compared to the normal tissue. On EUS, the pancreatic RCC metastases were typically round, well circumscribed, homogenous, hypoechoic, and hypervascular lesions. The CT/MRI and EUS characteristics of the patients are illustrated in Figure 1a–d. In 21 of the 33 patients, CT/MRI and EUS characteristics of the tumors were felt to be consistent with metastatic RCC. Twelve patients (36%) had overlapping imaging features and the possibility of another primary pancreatic neoplasm, such as PNET was raised [Table 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Computed tomography abdomen showing multiple enhancing nodules throughout the pancreas (red arrows show multiple masses). (b) EUS of the pancreas showing multiple pancreatic metastases of renal cell carcinoma. (c) Computed tomography abdomen showing a single mass in the body of the pancreas (the red arrow shows the single mass). (d) EUS of the pancreas showing a single pancreatic mass

Table 2.

Summary of computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging, endoscopic ultrasound guided, and fine needle aspiration characteristics for metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas

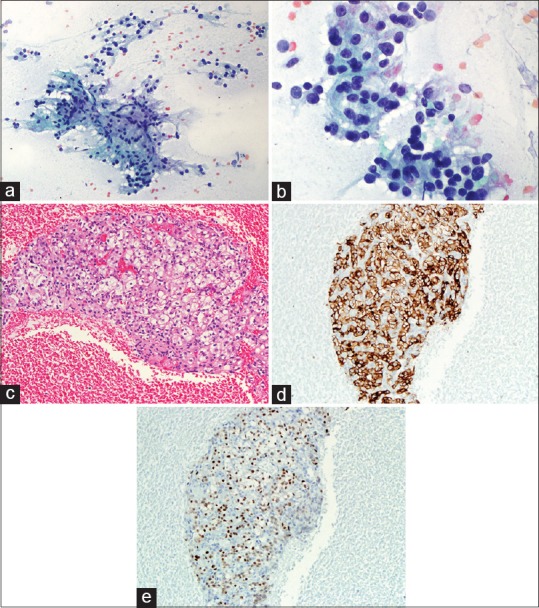

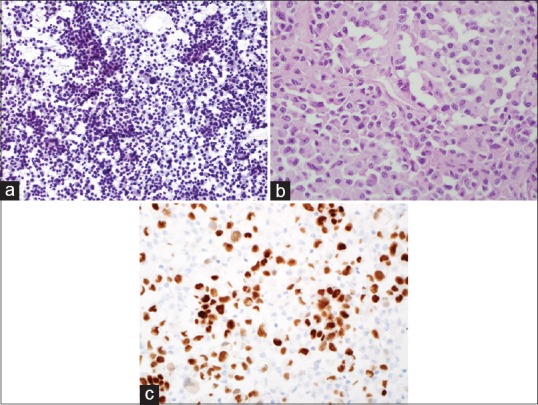

EUS-FNAs were performed on all 33 patients and the diagnosis of “metastatic RCC” was rendered on all cases. Five cases had limited tumor cells. Only cytology smears and liquid-based cytology preparations were available, these 5 cases had typical morphologic features of RCC and the clinical history and imaging results also helped making the final diagnosis. Twenty-eight cases had cytology smears, liquid-based cytology preparations, and cell blocks. All cell blocks had recognizable tumor cells. Thirteen cases with cell blocks had immunocytochemical stains. Among the 28 cases with abundant cellular materials, classical cytomorphology of RCC with large cohesive clusters of epithelial cells with intersecting blood vessels was noted in 23 cases (82%) [Figure 2a and Table 2]. The tumor cells had large nuclei, moderate amount of vacuolated cytoplasm, poorly defined cell borders, and visible nucleoli [Figure 2b]. Five cases had cytology findings that are not classic of RCC [Table 2]; two had large clusters of tumor cells without the typical hyper-vasculature, and the tumor cells had abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm [Figure 3a]; and two cases had large clusters of tumor cells with moderate amount of dense amphophilic cytoplasm. One case had large pleomorphic tumor cells arranged in tubular or “glandular” pattern. The five cases with limited cellularity had rare groups of tumor cells with vacuolated cytoplasm. The cell blocks were not contributory. Among the 13 cases with immunostains, the most common markers used were Pax8, CD10, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), synaptophysin, chromogranin, beta-catenin, and pan-cytokeratin. All the metastatic RCCs in our study were positive for the following markers: Pan-cytokeratin, CD10, EMA, and PAX-8 [Figures 2c–e and 3b, c]; they were negative for synaptophysin, chromogranin, and negative for nuclear staining of beta-catenin.

Figure 2.

(a) Cytology smear of an EUS-fine needle aspiration of pancreas showing cohesive cluster of epithelial cells with intersecting blood vessels (Pap, ×200). (b) High power view of 2A showing renal cell carcinoma tumor cells with large nuclei, moderate to abundant vacuolated cytoplasm, and visible nucleoli (Pap, ×400). (c) Cell block of 2A showing the typical renal cell carcinoma with tumor cells of clear cytoplasm (H and E, ×200). (d) Immunohistochemical stain of EMA on the above cell block showing the tumor cells are positive for epithelial membrane antigen (×200). (e) Immunohistochemical stain of PAX-8 on the cell block showing the tumor cells are positive (nuclear staining) for PAX-8 (×200)

Figure 3.

(a) Cytology smear of another EUS-fine needle aspiration of pancreas showing large discohesive tumor cells with abundant granular cytoplasm (Pap, ×200,). (b) Cell block of 3A showing the large tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (H and E, ×400). (c) Immunohistochemical stain of PAX-8 on the cell block showing the tumor cells are positive (nuclear staining) for PAX-8 (×400)

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis of the EUS and cytological features of 33 RCCs metastatic to the pancreas, we find that these tumors are usually well-circumscribed, lobulated, and hypervascular sonographically. Although the majority of these tumors are associated with widespread metastases, solitary metastasis can occur. EUS-FNA is accurate in diagnosing RCC metastatic to the pancreas.

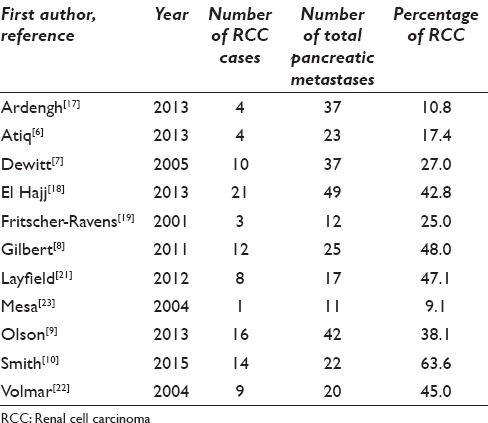

The pancreas is an unusual site for metastasis.[3] The diagnosis of metastases to the pancreas by EUS-FNA has been demonstrated to be beneficial and accurate.[2] RCC was noted to be the most common metastasis to the pancreas.[12] Although EUS-FNA of metastases to the pancreas has been extensively reported in the literature, the cases of EUS-FNA of metastatic RCC are often “lumped” with other metastases to the pancreas [Table 3]. To our knowledge, this is the largest EUS-FNA series of RCC metastasis to the pancreas.

Table 3.

Summary of fine needle aspiration cytology of metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas reported in the literature

Most of our patients (97%) have documented history of RCC. This clinical history is very useful in accurately diagnosing RCC metastatic to the pancreas. However, the latency period of RCC metastasis to the pancreas is quite long with an average time interval of 6.8 years, and the case with the longest latency period is 14 years. These data are in agreement with several published papers which report long interval between the primary RCC diagnosis and the occurrence of pancreatic metastases.[10,24,27] The mode of RCC metastasis to the pancreas is generally accepted as hematogenous, especially if there is an extrapancreatic spread to other organs.[28] However, in cases with just isolated pancreatic metastases, the hematogenous spread would fail to explain the increased frequency of multiple isolated pancreatic metastases in the absence of metastases to other organs. A hypothetical theory is that the RCC cells might have a unique affinity toward the parenchyma of the pancreas where optimal conditions for maturation may exist. This theory may explain why there are cases of late isolated pancreatic metastases. Therefore, metastatic RCC needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis even if the patient had RCC many years ago.[29,30]

The correct diagnosis of RCC rather than primary pancreatic neoplasm is of paramount importance in deciding the course of therapy.[31,32] CT/MRI is usually used as the initial diagnostic modality.[14,15] In our study, 27 of the 33 patients are under annually surveillance with CT and/or MRI. On contrast enhanced CT and MRI, most of the RCC metastases demonstrate intense enhancement on arterial and venous phase images compared to the normal tissue. Tumors smaller than 1.5–2 cm in diameter enhanced homogenously while in the larger lesions rim enhancement was seen, reflecting the hypervascularization of the vital tumor tissue and diminished or absent perfusion of necrotic components as seen in the primary RCC.[13,14,32] Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas typically appear as uniformly nonenhancing masses on CT and intense enhancement is very uncommon owing to their desmoplastic composition, thus, they can be reliably distinguished.[11,15] However, nonfunctional pancreatic endocrine tumors (PNETs) can be difficult to differentiate as they share the same morphological and contrast enhancement characteristics as that of RCC.[15,32] In our study, 12 of the 33 cases were thought to be PNET on CT/MRI. In those cases that CT/MRI cannot make definitive diagnosis, and additional diagnostic modalities, such as EUS-FNA, are needed.

EUS-FNA has been increasingly used recently due to its higher sensitivity in detecting and diagnosing pancreatic lesions, especially small lesions compared to other modalities.[16] On EUS, the pancreatic RCC metastases usually appear as hypoechoic, round, well circumscribed, homogenous lesions. The hypervascular nature of the metastases compared to the normal tissue can be well appreciated using Color Doppler imaging.[18,19,33] On the contrary, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas which constitute the majority of primary pancreatic malignancies usually have an irregular tumor edges and are hypovascular.[34] However, PNET can share similar EUS morphology with metastatic RCC.[6,8,18] Twelve patients in our study have CT/MRI morphologic features that have overlapping features with primary pancreatic neoplasms. Therefore, EUS-FNA has been often used to visualize and directly sample these lesions.[9,10,19] Among the 33 EUS-FNA cases in our study, 8 of them have single mass in the pancreas. It has been reported in the literature that up to 48% of pancreatic metastases can be unifocal, therefore, it is challenging to differentiate these tumors by imaging alone. Eight patients have documented malignancies other than RCC in our series; these include lung adenocarcinoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma, high-grade urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, and prostate adenocarcinoma. Among these patients, even though the CT/MRI and EUS are quite typical of pancreatic metastases, sampling the lesions with EUS-FNA enables the correct diagnosis.

Clear cell RCC is the most common subtype of RCC metastasis to the pancreas in our study (74%). The rest of the patients (26%) have RCC, unclassified type. These results are in agreement with previous reports.[12,30] Adsay et al., reported 2 cases of sarcomatoid RCC and 1 case of papillary RCC spread to the pancreas.[4] We do not encounter these subtypes of RCC in our study. The cytomorphology of metastatic RCC in our study reflects the histologic subtypes of RCC. The FNA biopsy of classic clear cell RCC is typically moderately cellular. The tumor cells occur in clusters, sheets, and often grow along capillaries. Abundant pale and clear cytoplasm is usually observed. Nuclei are often centrally placed, and prominent nucleoli are visible. Few cases have hyaline globules in the cytoplasm. In our study, a definitive diagnosis of RCC is often made with classic cytomorphology given the patient's history of RCC and the imaging features. On the other hand, most of the RCC, unclassified subtype demonstrate overlapping morphologic features with other malignant neoplasms. Two cases in our study show discohesive, single large tumor cells with abundant granular cytoplasm raising the possibilities of PNET, epithelioid angiomyolipoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, etc. Two cases show cytologic features of undifferentiated carcinoma with large pleomorphic tumor cells with dense amphophilic cytoplasm. One case is more reminiscent of high-grade breast carcinoma with tumor cells arranged in tubules. In this case, the tumor cell nuclei are large and pleomorphic and the cytoplasm are scant. Reviewing the patient's previous histology of RCC is essential and very helpful for the correct diagnosis and we can do that in 21 of the 33 cases. Immunochemistry has an important role in differential diagnosis of metastatic RCC to the pancreas.[20,21,26,27] RCC typically coexpress pan-cytokeratin, vimentin, EMA, CD10, and PAX-8.[24,25] In our study, the most common immunochemical markers used are pan-cytokeratin, EMA, CD10, and PAX-8. These markers along with neuroendocrine markers can be very helpful in distinguishing RCC from primary pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm. In our study, the 13 cases with attempted immunostains have unequivocal results supporting the diagnosis of RCC.

The treatment of pancreatic metastases of RCC remains controversial owing to their rarity and the complex natural history of RCC, ranging from cases with long disease free-interval to others with early development of widespread metastases.[28] In patients with isolated metastases of pancreas, surgical resection may improve the survival.[35] Surgical treatment is usually not feasible in cases with locally advanced disease.[5] Chemotherapy has been proven to be efficacious for inoperable cases, but may be associated with considerable toxic effects.[12] Recently, molecular targeted therapy with drugs, such as Pazopanib (Novartis Inc., USA) and Sunitinib (Pfizer Corp., USA), have been reported to have more clinical efficacy in patients with advanced RCC.[36,37] The prognosis of metastatic RCC to the pancreas is in general poor. However, Grassi et al. have shown that the presence of pancreatic metastasis seems to be associated with a longer survival than the presence of metastasis at other sites.[38] Nevertheless, the treatment options are largely dependent upon correct diagnosis of metastatic RCC.

CONCLUSION

We present a large series of metastatic RCC to the pancreas diagnosed by EUS-FNA. EUS evaluation is complementary to cross-sectional imaging, and these tumors can be accurately sampled by EUS-FNA. Cytomorphology of EUS-FNA can be aided with patient's history, imaging analyses, cell block, and immunohistochemical stains.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors have no competing interest to declare.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by the ICMJE. All authors are responsible for the conception of this study, have partipated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors have no competing interests.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

CT - Computed Tomography

EMA - Epithelial Membrane Antigen

EUS-FNA - Endoscopic Ultrasonography-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration

MRI - Magnetic Resonance Imaging

PNETs - Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

RCC - Renal Cell Carcinoma

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Contributor Information

Rahul Pannala, Email: pannala.rahul@mayo.edu.

Karyn M. Hallberg-Wallace, Email: hallbergwallace.karyn@mayo.edu.

Amber L. Smith, Email: smitha4@ccf.org.

Aziza Nassar, Email: nassar.aziza@mayo.edu.

Jun Zhang, Email: zhang.jun@mayo.edu.

Matthew Zarka, Email: zarka.matthew@mayo.edu.

Jordan P. Reynolds, Email: reynolj4@ccf.org.

Longwen Chen, Email: chen.longwen@mayo.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Showalter SL, Hager E, Yeo CJ. Metastatic disease to the pancreas and spleen. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:160–71. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstantinidis IT, Dursun A, Zheng H, Wargo JA, Thayer SP, Fernandez-del Castillo C, et al. Metastatic tumors in the pancreas in the modern era. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:749–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzahrani MA, Schmulewitz N, Grewal S, Lucas FV, Turner KO, McKenzie JT, et al. Metastases to the pancreas: The experience of a high volume center and a review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:156–61. doi: 10.1002/jso.22009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adsay NV, Andea A, Basturk O, Kilinc N, Nassar H, Cheng JD. Secondary tumors of the pancreas: An analysis of a surgical and autopsy database and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:527–35. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-0987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung JH, Wang SE, Shyr YM, Su CH, Chen TH, Wu CW. Resection for secondary malignancy of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2012;41:121–9. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821fc8f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atiq M, Bhutani MS, Ross WA, Raju GS, Gong Y, Tamm EP, et al. Role of endoscopic ultrasonography in evaluation of metastatic lesions to the pancreas: A tertiary cancer center experience. Pancreas. 2013;42:516–23. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31826c276d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeWitt J, Jowell P, Leblanc J, McHenry L, McGreevy K, Cramer H, et al. EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic metastases: A multicenter experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:689–96. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert CM, Monaco SE, Cooper ST, Khalbuss WE. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of metastases to the pancreas: A study of 25 cases. Cytojournal. 2011;8:7. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.79779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson MT, Wakely PE, Jr, Ali SZ. Metastases to the pancreas diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 2013;57:473–80. doi: 10.1159/000352006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AL, Odronic SI, Springer BS, Reynolds JP. Solid tumor metastases to the pancreas diagnosed by FNA: A single-institution experience and review of the literature. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123:347–55. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghavamian R, Klein KA, Stephens DH, Welch TJ, LeRoy AJ, Richardson RL, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas: Clinical and radiological features. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:581–5. doi: 10.4065/75.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballarin R, Spaggiari M, Cautero N, De Ruvo N, Montalti R, Longo C, et al. Pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: The state of the art. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4747–56. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biset JM, Laurent F, de Verbizier G, Houang B, Constantes G, Drouillard J. Ultrasound and computed tomographic findings in pancreatic metastases. Eur J Radiol. 1991;12:41–4. doi: 10.1016/0720-048x(91)90131-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein KA, Stephens DH, Welch TJ. CT characteristics of metastatic disease of the pancreas. Radiographics. 1998;18:369–78. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.2.9536484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmowski M, Hacke N, Satzl S, Klauss M, Wente MN, Neukamm M, et al. Metastasis to the pancreas: Characterization by morphology and contrast enhancement features on CT and MRI. Pancreatology. 2008;8:199–203. doi: 10.1159/000128556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitman MB, Deshpande V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of the pancreas: A morphological and multimodal approach to the diagnosis of solid and cystic mass lesions. Cytopathology. 2007;18:331–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ardengh JC, Lopes CV, Kemp R, Venco F, de Lima-Filho ER, dos Santos JS. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the suspicion of pancreatic metastases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Hajj II, LeBlanc JK, Sherman S, Al-Haddad MA, Cote GA, McHenry L, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of pancreatic metastases: A large single-center experience. Pancreas. 2013;42:524–30. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31826b3acf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritscher-Ravens A, Sriram PV, Krause C, Atay Z, Jaeckle S, Thonke F, et al. Detection of pancreatic metastases by EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:65–70. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.111771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hijioka S, Matsuo K, Mizuno N, Hara K, Mekky MA, Vikram B, et al. Role of endoscopic ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in diagnosing metastasis to the pancreas: A tertiary center experience. Pancreatology. 2011;11:390–8. doi: 10.1159/000330536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layfield LJ, Hirschowitz SL, Adler DG. Metastatic disease to the pancreas documented by endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration: A seven-year experience. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:228–33. doi: 10.1002/dc.21564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volmar KE, Jones CK, Xie HB. Metastases in the pancreas from nonhematologic neoplasms: Report of 20 cases evaluated by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:216–20. doi: 10.1002/dc.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mesa H, Stelow EB, Stanley MW, Mallery S, Lai R, Bardales RH. Diagnosis of nonprimary pancreatic neoplasms by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:313–8. doi: 10.1002/dc.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dousset B, Andant C, Guimbaud R, Roseau G, Tulliez M, Gaudric M, et al. Late pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surgery. 1995;117:591–4. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoshino Y, Shinozaki H, Kimura Y, Masugi Y, Ito H, Terauchi T, et al. Pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: A case report and literature review of the clinical and radiological characteristics. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:289. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katsourakis A, Noussios G, Hadjis I, Alatsakis M, Chatzitheoklitos E. Late solitary pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: A case report. Case Rep Med 2012. 2012:464808. doi: 10.1155/2012/464808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thadani A, Pais S, Savino J. Metastasis of renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas 13 years postnenhrectomv. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:697–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sellner F, Tykalsky N, De Santis M, Pont J, Klimpfinger M. Solitary and multiple isolated metastases of clear cell renal carcinoma to the pancreas: An indication for pancreatic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:75–85. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hafez KS, Novick AC, Campbell SC. Patterns of tumor recurrence and guidelines for followup after nephron sparing surgery for sporadic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1997;157:2067–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson LD, Heffess CS. Renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas in surgical pathology material. Cancer. 2000;89:1076–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1076::aid-cncr17>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mallery JS, Centeno BA, Hahn PF, Chang Y, Warshaw AL, Brugge WR. Pancreatic tissue sampling guided by EUS, CT/US, and surgery: A comparison of sensitivity and specificity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:218–24. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yun HS, Min YW, Lee MJ, Chang WI, Lee KH, Lee KT, et al. Clinicoradiologic characteristics and outcomes of metastatic cancer to the pancreas and double primary pancreatic cancer. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palazzo L, Borotto E, Cellier C, Roseau G, Chaussade S, Couturier D, et al. Endosonographic features of pancreatic metastases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:433–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aso A, Ihara E, Osoegawa T, Nakamura K, Itaba S, Igarashi H, et al. Key endoscopic ultrasound features of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma smaller than 20 mm. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:332–8. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.878745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zerbi A, Ortolano E, Balzano G, Borri A, Beneduce AA, Di Carlo V. Pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: Which patients benefit from surgical resection? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1161–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motzer RJ, Basch E. Targeted drugs for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Lancet. 2007;370:2071–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61874-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grassi P, Verzoni E, Mariani L, De Braud F, Coppa J, Mazzaferro V, et al. Prognostic role of pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: Results from an Italian center. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2013;11:484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]