Abstract

Background

Although linkages have been found between agricultural interventions and nutritional health, and the development of clean fuels and improved solid fuel stoves in reducing household air pollution and adverse health effects, the extent of the potential of combined household interventions to improve health, nutrition and the environment has not been investigated. A systematic review was conducted to identify the extent and type of community-based agricultural and household interventions aimed at improving food security, health and the household environment in low and middle income countries.

Methods

A systematic search of Ovid MEDLINE, PUBMED, EMBASE and SCOPUS databases was performed. Key search words were generated reflecting the “participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes and study design” approach and a comprehensive search strategy was developed following “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” recommendations. Any community-based agricultural and/or household interventions were eligible for inclusion if the focus was to improve at least one of the outcome measures of interest. All relevant study designs employing any of these interventions (alone/in combination) were included if conducted in Low and middle income countries. Review articles, and clinical and occupational studies were excluded.

Results

A total of 123 studies were included and grouped into four intervention domains; agricultural (n = 27), air quality (n = 34), water quality (n = 32), and nutritional (n = 30). Most studies were conducted in Asia (39.2 %) or Africa (34.6 %) with the remaining 26.1 % in Latin America. Very few studies (n = 11) combined interventions across more than one domain. The majority of agricultural and nutritional studies were conducted in Africa and Asia, whereas the majority of interventions to improve household air quality were conducted in Latin America.

Conclusions

It is clear that very little trans-disciplinary research has been done with the majority of studies still being discipline specific. It also appears that certain low and middle income countries seem to focus on domain-specific interventions. The review emphasizes the need to develop holistic, cross-domain intervention packages. Further investigation of the data is being conducted to determine the effectiveness of these interventions and whether interdisciplinary interventions provide greater benefit than those that address single health or community problems.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3731-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Agriculture, Food security, Nutrition, Household air pollution, Water quality, Intervention, Health

Background

Although there has been a significant improvement in global food security, still 805 million people (one in eight people) in low and middle income countries (LMIC) remain chronically undernourished [1]. According to the key findings of the Global Food Security Index 2015 [2], the rate of under nutrition is considerably higher in low and lower middle income countries (25.4 % and 16.5 % respectively) compared to high income countries (4.9 %). It is also estimated that 29.1 % and 15.5 % of children under the age of five years in lower middle income countries are either stunted or underweight. The prevalence rate is even higher in low income countries where 39.1 % of children under the age of five years are stunted and 22.6 % are underweight [2].

In addition to the health effects of food insecurity leading to poor nutrition, household air pollution from combustion of solid cooking fuels such as firewood, charcoal, etc. is the fourth leading cause of mortality in LMIC [3]. Evidence from epidemiological studies have shown that exposure to household air pollution is associated with acute respiratory tract infection, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cataract and lung cancer [4–6]. Likewise diarrhoea and other common infectious diseases due to poor hygiene and sanitation are also causing significant public health problems in LMIC [3].

It is evident that health is a complex phenomenon determined by multiple risk factors. Complex environmental interactions make it difficult to determine pathways to health in many communities. Food and diet is clearly an important route for exposure to pathogens, but it should not be considered in isolation, since other environmental exposures, such as household air pollution due to burning of biomass for cooking, pesticide exposure from agricultural use and polluted water for drinking, can be equally or more important to health. Food insecurity leading to poor nutrient intake is the main cause of malnutrition, but it is also dependent on other immediate causes, such as the individual’s health status [7]. Previous studies have recognised strong linkages between agricultural interventions and nutritional health [8–10] and the development of clean fuels and improved solid fuel stoves in reducing household air pollution and adverse health effects [11]. However, the scale and effectiveness of combined household interventions to improve health, nutrition and the environment has not been investigated. It is unknown whether interventions are inter-disciplinary, crossing domains of health, nutrition, agriculture and/or environment and where these interventions are being conducted. This review determined the extent and types of community-based complex agricultural and household interventions to improve food security, health status and the household environment in LMIC.

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed following the recommendations in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [12]. Key search words were generated reflecting the PICOS (participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes and study design) approach [12]. A database search of Ovid EMBASE was performed using Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, keywords and truncations covering the potential interventions, outcomes of interest and study design (Additional file 1). The search strategy was developed by combining those search terms using appropriate Boolean operators such as AND/OR/NOT. The search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE, PUBMED and SCOPUS databases were then derived from those search terms and conducted in January 2015. In addition, web and hand searches of bibliographies of identified studies were also performed manually to identify any additional potentially eligible articles.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

Community-based agricultural and household interventions such as the introduction of biogas, improved cook stoves, home gardening, animal husbandry, livestock farming and nutrition education were eligible to be included in this study if the focus of the intervention was to improve at least one of the outcome measures of interest (Table 1). Human studies employing any of these interventions, alone or in combination, and published after 1990, were included.

Table 1.

Definitions of outcomes of interest measured

| Outcome categories | Outcomes of interest measured |

|---|---|

| Food production | Year round of food production, production of vitamin A- rich fruits and vegetables, poultry stock and egg production, fish production, access to goat milk and other home grown foods |

| Food consumption | Household food security level/score, Dietary Diversity Score (DDS), consumption of food/food groups per day |

| Nutrient intake | Micro- and macro-nutrient intake levels |

| Anthropometry | Prevalence of Stunting [Weight for age Z-score (WAZ)], Wasting [height for age Z-score (HAZ)], underweight, child growth, height and weight gain |

| Nutrient deficiencies | Vitamin A deficiency level, Incidence/prevalence of anaemia, serum retinol concentration, serum ferritin level, haemoglobin, night blindness |

| Air quality | Kitchen/household/personal exposure to carbon monoxide (CO) and/or concentration of fine particulate matter of diameter < 2.5 μm (PM2.5), kitchen smoke, suspended particulate matter (PM) concentration, nitrogen dioxide concentration, ratio of food to fuel |

| Health | Incidence and/or prevalence of: Diarrhoeal disease; morbidity; respiratory disease symptoms (cough, runny nose, breathlessness, incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), pneumonia); eye irritation/infection, headache. Changes in: lung function performance; cognitive performance and attention levels; quality of life |

| Microbial Contamination | Thermo tolerant coliforms (TCC) count, level of E.coli contamination |

| Hygiene and sanitation | Kitchen and hand hygiene, behaviour and knowledge of water storage, self-reported compliance |

| Education | Perception and knowledge of health and nutrition |

The review was open to include any interventional or observational study, such as randomised control trial (RCT), cluster-randomised trial (CRT), cross-sectional study (CSS) and longitudinal studies conducted in LMIC as defined by the World Bank list of economics for 2015. As the main focus of this study was to identify community-based household interventions, clinical and occupational studies were excluded from the review. Similarly, review articles and studies from high income countries were excluded from the review.

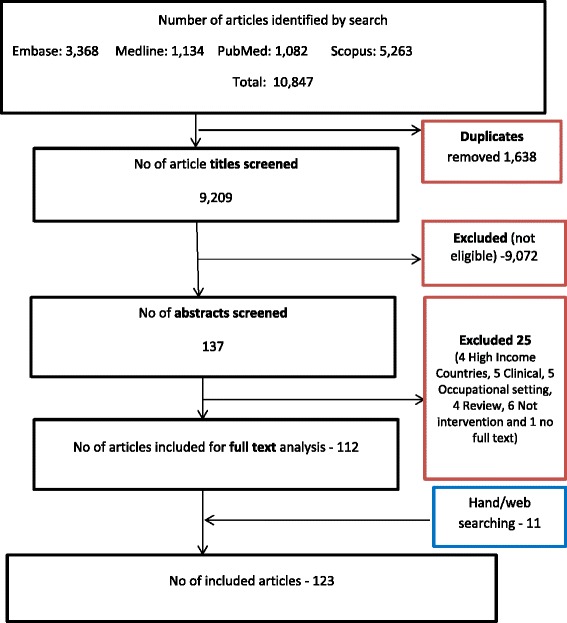

All articles identified by electronic searching from the four databases were exported to a web-based bibliography and database manager namely, Refworks. The titles were merged in one database and duplicates removed (Fig. 1). The primary reviewer (SG) screened titles and selected potentially relevant abstracts following predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Then four further reviewers (DM, SS, JK and JS) independently examined 10 % of randomly selected titles and abstracts to ensure the accuracy of title and abstract screening process. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion and checking the full text articles. All articles deemed potentially eligible were retrieved in full text. Reference lists of included studies were also checked to identify other relevant studies.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Data extraction and management

A standard data extraction form (Additional file 2) was designed considering the Cochrane systematic review data collection checklist [13]. The data collection form was piloted and amended prior to starting the formal data extraction.

Data from all included studies were extracted independently by three reviewers. The extracted data from 10 % of randomly selected articles was then checked independently by a second reviewer to ensure all the correct information was recorded.

Data analysis

A narrative analysis was conducted based on interventional categorisation. Interventions were categorised according to four domains defined as follows:

Agricultural interventions: Interventions such as home gardening and animal husbandry that have the explicit goal of improving food productivity, nutritional status, health, dietary diversity and/or food security.

Air quality interventions: Interventions such as improved cook stove and biogas that have the clear aim of improving household air quality and occupant’s health.

Water quality interventions: Interventions such as water filters (sand and bio sand), solar disinfection technique, water treatment using chlorine tablets alone and/or combination with sanitation health and hygiene education that have the clear aim of improving drinking water quality and health.

Nutritional interventions: Interventions such as nutrition education, complementary food and nutritional supplements that have the clear aim of improving participants’ nutritional status, dietary diversity, and health and food security.

The studies from each interventional category were summarised in tables and narrative text provided to summarise the following aspects:

country where the study was conducted

sample size

setting

study designs followed

types of interventions provided

intervention duration

outcomes of interest measured

Assessment of methodological quality

An assessment of the validity of included studies was conducted alongside the data extraction using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool for quantitative studies [14]. Studies were categorised as strong, moderate or weak based on their quality with regards to component ratings of selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, withdrawals and drop-outs and analysis.

Results

Identified studies

The search retrieved 10,847 unique articles (Fig. 1). After removal of 1,638 duplicates the remaining 9,209 articles were screened on the basis of title review. The first stage selection excluded 9,072 articles on the basis of predefined exclusion criteria. Studies were mainly excluded as they were conducted in high income countries, clinical or occupational settings, were not interventional studies or review articles, etc. From these 137 articles were potentially eligible for abstract screening. Finally, 112 articles met the eligibility criteria for the detailed analysis. Of the 25 articles excluded at the abstract screening stage four of them were from high income countries, five were in a clinical setting (Cl), five involved occupational settings, four were review articles, six papers were not interventional studies, and the full text of one paper was not available. Eleven additional articles were identified by hand/web searching. Finally, a total of 123 studies were included for the final review.

Study characteristics

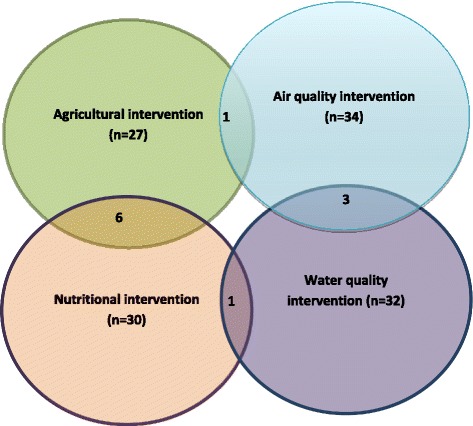

Of the 123 included studies in the review, 27 (21.9 %) were agricultural interventions, 34 (27.6 %) were air quality interventions, 32 (26 %) were water quality interventions and 30 (24.3 %) were nutritional interventions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Overlapping intervention domains

Characteristics of agricultural interventions (n = 27)

Of the 27 studies (Table 2) reporting agricultural interventions, 14 projects promoted and supported home gardening and household food production or the improvement of the existing garden with micronutrient-rich fruit and vegetables. Six projects promoted animal husbandry, such as pig and poultry breeding, goat farming, fisheries and dairy production. Five studies observed the effectiveness of combined home gardening and nutrition education intervention. One promoted home gardening with animal husbandry and another, a combination of home gardening, animal husbandry and nutrition education.

Table 2.

Characteristics of agricultural intervention studies

| Study (Author and publication year) | Country | Participants (sample size, age, setting) | Study design | Intervention details (I = Intervention and C = Control) | Duration of intervention (months) | Outcome measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayele Z and Peacock C; 2003 | Ethiopia | 210 households | CSS (Pre and post) | I: Animal husbandry: goat farming | NR | Food consumption, nutrient deficiencies |

| Belachew T et al. 2013 | Ethiopia | 2100 adolescents, 13–17 years, household | 5 year Longitudinal study | I: Food production | NR | Food consumption |

| Bezner KR, et al. 2010 | Malawi | 3838 children <3 years, household | Prospective quasi- experimental study | I: Intercropping legumes and nutrition education C: Usual practice |

72 | Anthropometry |

| Bloem MW et al. 1996 | Bangladesh | 7341 participants, all aged, household | Intervention study | I: Home gardening | NR | Food production |

| Bushamuka VN, et al. 2005 | Bangladesh | 2,160 households | Intervention study | I: Home gardening C: Usual practice |

NR | Food production, food consumption |

| Cabalda AB, et al. 2011 | Philippines | 200 households, participants aged 2–5 years | CSS (2 group comparison) | I: Home gardening (n = 105) C: Without home garden (n = 95) |

NR | Food consumption |

| Faber M, et al. 2002, | South Africa | 208 participants, aged 2–5 years, community | CSS (Pre and post) | I: Home gardening and nutrition education (n = 108) C: Usual practice (n = 100) |

20 | Food consumption, nutrient intake, nutrient deficiencies |

| Gibson RS et al. 2003 | Malawi | 281 households, aged 30–90 months | Intervention study | I: Multiple: Animal husbandry and home gardening (n = 200) C: Usual practice (n = 81) |

12 | Food consumption, anthropometry, education, nutrient deficiencies, health |

| Haseen F, 2007 | Bangladesh | 370 households, all age participants | CSS (Pre and post) | I: Home based food production, increased purchasing capacity to improve food intake and nutritional status (n = 180) C: Usual practice (n = 193) |

24 | Food consumption, nutrient intake |

| Hoorweg J, et al. 2000 | Kenya | 144 households, participants aged between 6–59 months | Intervention study | I: Dairy farming (n = 30) and dairy customers (n = 24) C: Usual practice (n = 90) |

NR | Food consumption, anthropometry, income |

| Hop LT; 2003 | Vietnam | NR | Longitudinal survey (LS) (pre and post) | I: Programs to improve pig and poultry breeding | NR | Food consumption, nutrient deficiencies |

| Hotz C, et al. 2012 | Uganda | >10,000 households, community | Randomised control trial (RCT) | I1: B-carotene–rich orange sweet potato (OSP) vines with training (n = 293 children, 212 women) I2: Education on female and child health and promotion of OSP (n = 179 children, 130 women) C: Usual practice (n = 280 children, 213 women) |

12 and 24 | Nutrient intake, nutrient deficiencies |

| Jones KM, et al. 2005 | Nepal | 819 households, community | Intervention study | I: Home gardening and nutrition education (n = 430) C: Usual practice (n = 389) |

36 | Food consumption, education |

| Kalavathi S, et al. 2010 | India | 150 household | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Package intervention of nutrition gardening, livestock rearing and nutrition education | 36 | Food production, food consumption and nutrient intake |

| Kerr RB, et al. 2010 | Malawi | 3838 participants, aged < 3 years, households | Intervention study | I: Home gardening and nutrition education (n = 1724) C: Usual practice |

72 | Anthropometry |

| Kidala D, et al. 2000 | Tanzania | 2250 household | Quasi-experimental (2 groups comparison) | I: Horticultural and nutrition education (n = 125 households) C: Usual practice (n = 125 households) |

60 | Nutritional knowledge, nutrient intake, nutrient deficiencies |

| Low JW, et al. 2007 | Mozambiqu | 741 children aged 13 months, household | Quasi-experimental (2 groups comparison) | I: Production of Orange-fleshed sweet potato (OFSP) and nutritional knowledge (n = 498) C: Usual practice (n = 243) |

24 | Nutrient intake, nutrient deficiencies |

| Miura S, et al. 2003 | Philippines | 152 women, household | CSS (pre and post) | I: Home gardening | NR | Food consumption |

| Murshed-e-Jahan K, et al. 2010 | Bangladesh | NR | Intervention study | I: Training support to farmers on aquaculture C: Usual practice |

NR | Food production, food consumption |

| Nielsen H, et al. 2003 | Bangladesh | 70 households, women of reproductive age and 5–12 years old girls | Intervention study | I: Poultry production (n = 35) C: Usual practice (n = 35) |

12 | Food production, food consumption |

| Olney DK, et al. 2009 | Cambodia | 500 households | CSS (Pre and post) | I: Home gardening (n = 300) C: Usual practice (n = 200) |

NR | Food consumption, anthropometry, health |

| Schipani S, et al. 2002 | Thailand | 60 children, household | Intervention study | I: Mixed home gardening (n = 30) C: Non gardening (n = 30) |

NR | Food consumption, anthropometry |

| Schmid M et al. 2007 | India | 220 participants, Child:6 to 39 months and mother > 15 years, community | CSS (pre and post) | I: Home gardening (n = 124) C: Without home garden (96) |

96 | Nutrient intake |

| Sha KK et al. 200, | Bangladesh | 1343 participants aged <24 months, households | Longitudinal study | I: Household production and availability of rice and other fresh foods e.g. Vegetables, fish, meat | NR | Food consumption, anthropometry |

| Smitasiri et al. 1999 | Thailand | 15 communities, all age | CSS (pre and post) | I: Home gardening (seed grant) and nutrition and health messages (271) C: without home gardening (247) |

Food consumption, nutrient intake | |

| Wyatt AJ, et al. 2013 | Kenya | 92 households | CSS (3 group comparison) | Dairy intensification I1: Milk production >6 l per day (n = 31) I2: Milk production <6 l per day (n = 31) C: No milk production (n = 30) |

2 | Food consumption |

| Yakubu A, et al. 2014 | Nigeria | 58 households, community | CSS (pre and post) | I: Cockerel exchange programme | NR | Food production |

RCT randomised control trial, CSS cross sectional study, NR not reported

Most of the studies were either cross sectional (n = 10) or intervention studies (n = 10) with one RCT [15]. There was a wide variation of sample sizes, ranging from 58 households [16] to >10,000 participants [15]. Similarly, duration of the studies varied; from a dairy intensifying intervention in Kenya for two months [17] to a home gardening study in India for 96 months [18]. Fourteen of these studies were conducted in Asia and the other 13 in Africa. The first home gardening study was conducted in Bangladesh in 1996 [19]. Most of these studies (n = 22) were conducted in a household setting and only a few in community settings.

Nineteen of these studies examined the effect of intervention on dietary diversity and improvement in food consumption, seven on food production, seven on nutrient intake, seven on nutritional deficiencies, seven on anthropometry, three on education, two on health and two on food security.

Characteristics of air quality interventions (n = 34)

Of the 34 air quality studies (Table 3), four projects introduced biogas [13–20] as an alternative means of cooking fuel, 17 projects promoted improved cook stoves and 11 studies examined the effectiveness of improved stoves with chimney to improve the household air quality. One project evaluated the impact of improved cook stoves with solar water disinfection and hand hygiene [21], and another looked at an improved cook stove intervention with biogas fuel and solar heaters [20].

Table 3.

Characteristics of air quality intervention studies

| Study (Author and publication year) | Country | Participants (sample size, age, setting) | Study design | Intervention details (I = Intervention and C = Control) | Duration of intervention (months) | Outcome measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander D, et al. 2013 | Bolivia | 31 household | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Improved cook stoves with chimney (Yanalo Cookstoves) | 12 | Air quality, health |

| Burwen J and Levine DI; 2012 | Ghana | 768 household | RCT | I: Improved cook stoves with chimney (n = 402) C: Traditional biomass stoves (usual practice) (n = 366) |

2 | Air quality, health, stove usages |

| Chengappa C, et al. 2007 | India | 60, household | Paired, before and after study | I: improved cook stoves (Sukhad) | 12 | Air quality |

| Clark LM, et al. 2009 | Honduras | 79 participants, mean age 43.2 years, household, | CSS (pre and post) | I: Improved cook stoves with chimney (n = 38) C: Traditional cook stoves (n = 41) |

3 | Air quality, health |

| Chowdhury Z et al. 2012 | China | 30 household | CSS (pre and post) | I: Improved stoves along with biogas burners and solar heaters | 2 | Air quality |

| Commodore AA, et al. 2013 | Peru | 84 participants household | Community-RCT (C-RCT) | I: Improved cook stoves (OPTIMA) (n = 39) C: Traditional biomass stove, NGO Stoves, self-improved stove (n = 45) |

3 | Air quality, health |

| Cynthia AA, et al. 2008 | Mexico | 34 households, | Randomised trial | I: Improved cook stoves (n = 60) | 1 | Air quality |

| Diaz E, et al. 2008 | Guatemala | 180 women, mean age 27.8 years, household | RCT | I: Improved cook stoves with chimney (Plancha) (n = 89) C: Traditional biomass stove (usual practice) (n = 91) |

26 | Air quality, health |

| Diaz E, et al. 2007 | Guatemala | 504 women, 27.7 years, household | RCT | I: Improved cook stoves with chimney (Plancha) (n = 259) C: Traditional biomass stove (usual practice) (n = 245) |

18 | Air quality, health |

| Dohoo C, et al. 2012 | Kenya | 62 women, household | CSS (comparison between 2 groups) | I: Biogas (n = 31) C: Traditional biomass stove (n = 31 |

2 | Health |

| Ezzati M, et al. 2000 | Kenya | 38 households | Intervention study | I: Improved cook stoves | 1 | Air quality |

| Fitzgerald C, et al. 2012 | Peru | 57 participants, mean age 33 years, household | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Improved cook stoves (n = 26 for PM2.5 and 25 for CO) | 5 | Air quality |

| Garfi M, et al. 2012 | Peru | 12 households | Intervention study | I: Low-cost tabular biogas digester | NR | Food production, air quality |

| Harris SA, et al. 2010 | Guatemala | 4000, household | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Improved cook stoves C: Traditional biomass stove (usual practice) |

48 | Health |

| Hartinger SM, et al. 2012 | Peru | 115 households, household, | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Multiple intervention; improved cook stoves, solar water disinfection and hand hygiene | 5 | Air quality, hygiene and sanitation, health |

| Jary HR, et al. 2014 | Malawi | 51 Women, mean age 38.1 years, households | RCT | I: Improved cook stoves (n = 25) C: Traditional biomass stove (usual practice) (n = 26) |

2 | Air quality, health |

| Katwal H, Bohara AK; 2009 | Nepal | 461 households | Intervention study | I: Biogas digester | NR | Air quality, health, Food production |

| Khushk WA, et al. 2005 | Pakistan | 159 women, mean age 43.27 (I) and 36.18 (C) years, household | CSS (comparison between 2 groups) | I: Improved cook stoves (n = 45) C: Traditional biomass stove (usual practice) (n = 114) |

2 | Air quality, health |

| Li Z, et al. 2011 | Peru | 57 households, participants aged 18–45 years, household | Intervention study (pre and post) | I : Improved cooking stove with chimney | 3 weeks | Air quality |

| McCracken JP, et al. 1998 | Guatemala | 11, household | CSS (comparison between 2 groups) | I: Improved cook stoves (n = 6) C: Traditional biomass stove (usual practice) (n = 5) |

NR | Air quality |

| McCracken JP, et al. 2011 | Guatemala | 534 Households | RCT | I: Improved stove with Chimney (n = 49) C: Traditional open fire stoves (n = 70) |

16 | Air quality, health |

| Mukhopadhyay R, et al. 2012 | India | 32 women, mean age 32 years, household | CSS (pre and post) | I: Improved cook stoves C: Traditional open fire biomass stove (usual practice) |

3 | Air quality, acceptability and usage |

| Ochieng CA, et al. 2012 | Kenya | 104 Women, household | CSS (comparison between 2 groups) | I: Improved stoves without chimney (n = 49) C: Traditional stoves (n = 45) |

6 | Air quality |

| Oluwole O, et al. 2013 | Nigeria | 59 participants, mothers 43 years and children 13 years, household | CSS (pre and post) | I: Improved stoves | 12 | Air quality, health |

| Pandey MR, et al. 1990 | Nepal | 20 households | Intervention study | I: Improved cook stoves (n = 20) | 5 | Air quality |

| Riojas-Rodriguez, et al. 2011 | Mexico | 47 women, mean age 28 years, household | RCT | I: Improved cook stoves fitted with chimney (Patsari stoves) (n = 30) C: Traditional stoves (n = 17) |

12 | Air quality |

| Romieu I, et al. 2009 | Mexico | 528 women, mean age 26.3 (I) and 25.5 (C) years, household | RCT | I: Improved cook stoves fitted with chimney (Patsari stoves) (n = 273) C: Traditional stoves (n = 255) |

10 | Health |

| Schilmann A, et al. 2014 | Mexico | 559 children <4 years, household | RCT | I: Improved cook stoves fitted with chimney (Patsari stoves) (n = 287) C: Traditional stoves (n = 272) |

10 | Health |

| Singh A, et al. 2012 | Nepal | 47 households, all aged participants | CSS (pre and post) | I: Improved mud stoves | 12 | Air quality, health |

| Singh S, et al. 2014 | India | 75 household | CSS (comparison between 2 groups) | I: Improved stoves C: Traditional stoves |

2 | Air quality |

| Smith KR, et al. 2011 | Guatemala | 534 households, participants aged <4 months at baseline | RCT | I: Improved wood stove with chimney (n = 265) C: Open wood fires (n = 253) |

14 | Health |

| Wafula EM, et al. 2000 | Kenya | 400 households, women aged 15–60 years and children <5 years | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Improved cook stoves (n = 200) C: Traditional three-stone stoves (n = 200) |

120 | Health |

| Zhou Y, et al. 2014 | China | 996 participants, aged > 40 years, household | CSS (comparison between 2 groups) | I: Biogas digester and improved kitchen ventilation (n = 740) C: Traditional biomass stove (usual practice) (n = NR) |

108 | Air quality, health |

| Zuk M, et al. 2007 | Mexico | 53 household | CSS (pre and post) | I: Improved cook stoves (Patsari stoves) | 5 | Air quality |

RCT randomised control trial, CSS cross sectional study, NR not reported

Most of the studies provided data either on pre and post or between group comparisons with nine randomised control trial. The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 11 [22] to 4,000 households [23]. The duration of the study also varied considerably; a Peru cook stove project lasted for 3 weeks [24], while one vented stove project in the highlands of Guatemala collected data for 48 months [23]. The majority of the studies (n = 18) were conducted in South America, nine were in Asia, with the other seven in African countries. The first cook-stove intervention study was conducted in Nepal in 1990 [25]. All of these studies were conducted in household settings.

Almost all of the studies (28 out of 34) examined the improvement in household air quality parameters such as particulate matter and carbon monoxide concentrations. Twenty studies assessed the impact of the intervention on participants’ health outcomes such as incidence of pneumonia, acute respiratory infections (ARI), conjunctivitis and lung function, and three examined the impact on food production.

Characteristics of water quality interventions (n = 32)

Of the 32 water quality intervention studies (Table 4), 12 were water filter interventions; nine were chlorine tablets/solutions interventions, seven were Solar disinfection; two were hand water pumps along with hygiene education and latrine construction interventions [26]; one was a health, hand hygiene, water quality and sanitation educational intervention [27]; one involved disinfection tablets along with sanitation and hygiene education [28]; one was a water disinfection stove [29] and one a filter along with improved cook stove [30].

Table 4.

Characteristics of water quality intervention studies

| Study (Author and publication year) | Country | Participants (sample size, age, setting) | Study design | Intervention details (I = Intervention and C = Control) | Duration of intervention (months) | Outcome measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boisson S, et al. 2010 | Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) | 240 household (1,144 participants mean age 39.1 years) | RCT | I: Lifestraw family filter (n = 120 households, 546 participants) C: Placebo filter (n = 120 households, 598participants) |

15 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Boisson S, et al. 2009 | Ethiopia | 313 households, 6 months and over, household | RCT | I: Life straw personal filter to be used for ingesting of untreated water both at home and away from home (n = 155) C: Usual practice (n = 158) |

5 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Boisson S, et al. 2013 | India | 2,163 household (2,986 children <5 years) | RCT | I: NaDC tabletsb (n = 1080) C: Placebo (n = 1083) |

12 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Brown J et al. 2008 | Cambodia | 180 households, all age participants | RCT | I: One of following: Ceramic water purifier (CWP) (n = 60) and Iron-rich ceramic water purifier (CWP-fe) (n = 60) C: Usual practice (n = 60) |

5.5 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Clasen T.F et al. 2006 | Bolivia | 60 households (317 individuals), all age, household | RCT | I: Water purification filter (20 households; 210 individuals) C: Usual practice (40 households; 107 individuals) |

5 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Clasen T, et al. 2007 | Bangladesh | 100 households, 555 participants of any age group | RCT | I: 67-mg NADCC tabletsb designed to treat 20–25 L of water (n= 50 households; 279 participants) C: Placebo consisting of tablets of the same colour, size and packaging (n = 50 households, 276 participants) |

4 | Microbial contamination |

| Clasen T, et al. 2005 | Columbia | 140 household | RCT | I: Ceramic Water filter (n = 76 households, 415 participants) C: Usual practice (n = 64 households, 265 participants) |

6 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Christen A, et al. 2009 | Bolivia | 2 household (27 proxy household for air quality) | CSS (pre and post) | I: Water disinfection stove (WADIS) | 6 | Water quality, Microbial contamination, air quality, health |

| Conroy R, et al. 1996 | Kenya | 206 children age 5–16 years, household | RCT | I: SODIS bottle (n = 108) C: Only water bottle and suggested to use indoor (n = 98) |

3 | Health |

| Crump JA, et al. 2005 | Kenya | 605 households (6650 participants) | Cluster- RCT | I1: Flocculant- disinfectant intervention (n = 201 households,2124 participants) I2: Sodium hypochlorite intervention (n = 203 households, 2249 participants) C: Usual practice (n = 201 households, 2277 participants) |

4 (20 weeks) | Microbial contamination, health |

| Davis J, et al. 2011 | Tanzania | 248 households, participants aged <5 years | Experimental field study | I: One of following 4 intervention: 1) Information on strategies to reduce water and sanitation related illness (n = 79) 2) Information as per 1 plus water quality tests (n = 84) 3) Information as per 1 plus hand-rinse test results (n = 90) 4) information as per 1 plus water and hand rinse results (n = 81) | 4 | Microbial contamination, hygiene and sanitation |

| Du Preez M, et al. 2008 | Zimbabwe and South Africa | 115 households, participants aged between 12 to 24 months | RCT | I: Ceramic water filter (n = 60) C: In-house water filter (n = 58) |

6 | Health |

| Du Preez M, et al. 2010 | South Africa | 649 households, 6 months to 5 years, household | RCT | I: SODISa bottles to be used to provide drinking water at all times and as much as possible drink directly from the bottle (n = 297) C: Usual practice (n = 267) |

12 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Fabiszewski de Aceituno AM, et al. 2012 | Honduras | 195 participants aged <5 years, household | RCT | I: Plastic Bio sand filters, a narrow mouth gallon (20 L), water jug and general education on hygiene and sanitation (n = 90 households, 532 participants) C : Usual practice (n = 86 households, 488 participants) |

10 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Graf J, et al. 2010 | Cameroon | 2,193 households, participants aged <5 years | CSS (pre and post) | I: SODIS bottles for water purification | 10 | Health |

| Garrett V, et al. 2008 | Kenya | 555 households (960 children aged <5 years) | RCT | I: Sodium hypochlorite water disinfection solution and storage containers and hygiene and sanitation education (n = 366) C: Usual practice (n = 189) |

2 (8 weeks) | Microbial contamination, health |

| Habib MA, et al. 2013 | Pakistan | 18,244, participants, household | Cluster-RCT | I: Diarrhoea pack (two packets of low osmolality ORS, one strip of Zinc tablets, two packets of water purification sachet and a leaflet with educational materials) (n = 9,581) C: Usual practice (n = 8,663) |

12 | Health |

| Henry FJ et al. 1990 | Bangladesh | 44 children, 6–23 months, community | Intervention Study | I: Latrine construction and hygiene education (n = 41) C: Usual practice (n = 43) |

6 | Health |

| Henry FJ et al. 1990 | Bangladesh | 92 participants, 6–18 months, household | Intervention study | I: Hand pumps, latrine construction and hygiene education (44) C: Hand pumps only (48) |

6 | Health |

| Lindquist ED, et. al; 2014 | Bolivia | 1,198 participants, household | Cluster-RCT | I1: A household level hollow fiber filter (n = 330) I2: Education (behaviour change communication) (n = 302) I3: Filter and education (n = 285) C: Life skills and attitudes and family responsibility message (n = 279) |

3 | Health |

| Luby,AP, et al. 2006 | Pakistan | 1340 households, all age participants | RCT | I: One of following intervention: 1) diluted bleach and a water vessel provided (n = 265) 2) soap and hand washing promotion provided (n = 262) 3) flocculent disinfectant water treatment and water vessel provided (n = 262) 4) flocculent-disinfection, soap and hand washing promotion provided (n = 266) C: Usual practice (n = 282) |

9 | Health |

| Mausezahi D et al. 2009 | Bolivia | 484 households, participants aged <5 years | RCT | I: SODIS bottles (n = 255 households; 376 children) C: Usual practice (n = 200 households; 349 children) |

14 | Health |

| Opryszko MC et al. 2010 | Afghanistan | 1514 households, all age participants, household | RCT | I: Multiple intervention; liquid chlorine with a water vessel (299 households), hygiene education (233 households), improved tube well (308 households) and combination of all (261 households) C: Usual practice (n = 292) |

17 | Diarrhoeal incidence |

| Quick RE et al. 1996 | Bolivia | 42 household | Intervention study (pre and post) | I1: 20 l narrow mouthed water vessel and the calcium hypochlorite solution (n = 15) I2: 20 l narrow mouthed water vessel (n = 15) C: Usual practice (n = 12) |

9 weeks | Microbial contamination, |

| Quick RE, et al. 1998 | Bolivia | 127 households | RCT | I: Water disinfection solution and storage vessels (n = 64 households, 400 individuals) C: Usual practice (n = 63 households, 391 individuals) |

8 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Ram PK, et al. 2007 | Madagascar | 242 households, participants aged 0–90 year | Intervention study | I: Water chlorination tablet and Jerrycan for water storage | NR | Education and self-reported compliance |

| Rangel JM, et al. 2003 | Guatemala | 100 households | RCT | I1: Chlorine bleach and 20 l narrow mouthed water vessel (n = 20) I2: Combined product c in narrow mouthed water vessel (n = 20) I3: Combined product c with customised vessel (n = 20) I4: Combined product c in traditional vessel (n = 20) C: Traditional vessel (n = 20) |

1 (4 weeks) | Microbial contamination, health |

| Rose A et al. 2006 | India | 200 children, participants aged <5 years, household | RCT | I: SODIS bottles for water purification plus diarrhoea prevention and treatment education (n = 100) C: Diarrhoeal prevention and treatment education only (n = 100) |

6 | Health |

| Rosa G, et al. 2014 | Rwanda | 566 households | RCT | I: Life straw family 2.0 filter and one improved stove (Eco Zoom Dura) (n = 285) C: Usual practice (n = 281) |

5 | Water quality, air quality |

| Stauber CE, et al. 2009 | Dominican Republic | 187 households, all aged participants | RCT | I: Plastic Bio Sand filters (n = 81 households, 447 participants) C : Usual practice (n = 86 households, 460 participants) |

10 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Stauber CE, et al. 2011 | Cambodia | 189 households, participants aged <5 years | RCT | I: Plastic Bio Sand filters (n = 90 households, 546 participants) C : Usual practice (n = 99 households, 501 participants) |

6 | Microbial contamination, health |

| Tiwari SS, et al. 2009 | Kenya | 59 household | RCT | I: Concrete Bio sand Filter and instruction on filter use (n = 30) C: Usual practice (n = 29) |

6 | Microbial contamination, health |

RCT randomised control trial, CSS cross sectional study, NR not reported, aSODIS: Solar Disinfection method, bNADCC tablets: Sodium Dichloroisocyanurate tablets, c Combined product: a product incorporating precipitation, coagulation, flocculation and chlorination technology

Most of the studies were RCT (n = 25) or intervention studies (n = 4). The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 2 [29] to 2,193 households [31] and the interventions were delivered over periods of 2 [29] to 15 [32] months. Nine studies were conducted in South America, 10 in Asia and the remaining 13 in African countries. All of these studies were conducted in household settings.

Twenty-seven of these studies looked at the impact of intervention on health especially on the incidence/prevalence of diarrhoeal diseases; 20 on microbial contaminations and water quality; two studies examined the level of knowledge and self-compliance, two investigated air quality and one hygiene and sanitation.

Characteristics of nutrition Interventions (n = 30)

Of the 30 nutrition intervention studies included in the review (Table 5), 11 studies were supplementary food and vitamin interventions, 13 nutrition education interventions, five nutrition education together with complementary food interventions, two combined interventions of nutrition education and home gardening [33, 34] and one combined package intervention of health care, nutrition education, water and sanitation [35].

Table 5.

Characteristics of nutrition intervention studies

| Study (Author and publication year) | Country | Participants (sample size, age, setting) | Study design | Intervention details (I = Intervention and C = Control) | Duration of intervention (months) | Outcome measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali D et al. 2013 | Bangladesh, Vietnam, Ethiopia | 2356 (Ethiopia), 3075 (Vietnam), 3422 (Bangladesh) households, participants aged 6 monthsnths-5 years | CSS | I: Nutrition education | NR | Food consumption and anthropometry |

| Chow J, et al. 2010 | India | participants aged 1–4 years, household | Intervention study | I: High dose vitamin A supplementation, Industrial fortification of mustard oil and GM fortification of mustard oil and seed | NR | Health |

| Creed-Kanashiro H et al. 2003 | Peru | 42 participants, aged 12–51 years, community | Interventional study (pre and post) | I: Nutrition education | NR | Nutrient deficiencies, education |

| Darapheak C, et al. 2013 | Cambodia | 6202 participants, aged 12–59 months, household | CSS (post intervention only) | I: Animal source food group C: Non animal source food group |

NR | Anthropometry, health |

| English RM, et al. 1997 | Vietnam | 720 children <6 years, community | CSS (2 groups) | I: Home gardening and nutrition education (n = 469) C: Usual practice (n = 251) |

24-36 | Nutrient intake, health |

| Faber M, et al. 2002 | South Africa | 208 participants, aged 2–5 years, community | CSS (Pre and post) | I: Home gardening along with nutrition education (n = 108) C: Usual practice (n = 100) |

20 | Nutrient intake |

| Fenn B et al. 2012 | Ethiopia | 5552 participants, 6–36 monthsnths, household | CSS (pre and post) | I: Multiple intervention; health care, nutrition education, water and sanitation (4124) C: Protective safety net programme (1428) |

30 | Anthropometry |

| Gibson RS et al. 2003 | Malawi | 281 participants, aged between 30–40 months, household | Quasi- experimental | I: Complementary foods (n = 200) C: Usual practice (n = 81) |

6 | Food consumption, nutrient intake, anthropometry |

| Grillenberger, et al. 2006 | Kenya | 498 participants, mean age 7.4 years | RCT | I: Three supplementary foods groups: meat (n = 134), milk (n = 144) and energy (veg oil) supplied as a school snack in a maize stew (n = 148) C: Usual practice (n = 129) |

24 | Anthropometry |

| Grillenberger, et al. 2006 | Kenya | 554 participants, mean age 7.4 years | RCT | I: Three supplementary foods groups: meat (n = 134), milk (n = 144) and energy (veg oil) supplied as a school snack in a maize stew (n = 148) C: Usual practice (n = 129) |

24 | Nutrient intake, anthropometry |

| Imran M, et al. 2014 | India | 245 participants, aged 2–4 years, community | Intervention study | I: Nutrition education along with supplementary nutrition and supervision | 12 | Anthropometry |

| Kabahenda M, et al. 2011 | Uganda | 89 children <4 years, household | RCT | I: Nutrition education (n = 46) C: Sewing classes (n = 43) |

12 | Food consumption, nutrient deficiencies |

| Khan A Z et al. 2013 | Pakistan | 586 participants, aged 6 mo- 8 years, household | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Nutrition education | 3 | Food consumption, anthropometry |

| Kilaru A, et al. 2005 | India | 242 infants aged 5–11 months, household | Intervention study | I: Nutrition education (n = 173) C: No nutrition education (n = 69) |

36 | Food consumption, Anthropometry |

| Lanerolle P and Atukorala S, 2006 | Sir Lanka | 229 adolescent girls aged between 15–19 years, household | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Nutrition education | 10 weeks | Nutrition knowledge, food consumption, nutrient deficiencies |

| Lartey A et al. 1999 | Ghana | 216 participants, aged 6–12 months, households | RCT | I: One of following complementary fortified foods: Weanimix (W) a combination of soybeans, maize and groundnuts, Weanimix plus minerals and vitamins (WM), Weanimix plus fish powder (WF) and Koko plus fish powder (KF) (n = 208) C: Usual practice (n = 465) |

6 | Anthropometry |

| Moore JB, et al. 2009 | Nicaragua | 182 adolescents and 67 mothers, community | Longitudinal study (pre and post) | I: Nutrition education | 48 for girls and 24 for mothers | Nutritional knowledge, nutrient deficiencies |

| Pawloski LR and Moore JB; 2007 | Nicaragua | 186 adolescent girls aged 10–17 years, community | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Nutrition education | 36 | Nutritional knowledge, Anthropometry, nutrient deficiencies |

| Phawa S, et al. 2010 | India | 370 mothers of children aged 12–71 months, community | Intervention study (2 groups) | I: Nutrition and health education (n = 195) C: Usual practice (n = 175) |

9 | Health |

| Pant CR, et al. 1996 | Nepal | 40,000 children aged 6–12 months | Intervention study (pre and post) | I: Mega dose vitamin A capsules and nutrition education C: Usual practice |

24 | Health, nutrient deficiencies |

| Rivera JA, et al. 2004 | Mexico | 650 children aged <12 months, household | Randomised crossover study | I: Nutrition Education along with micronutrient- fortified foods (n = 373) C: Cross over intervention group (n = 277) |

24 | Anthropometry, nutrient deficiencies |

| Roy SK, et al. 2005 | Bangladesh | 282 children aged 6–24 months, household | RCT | I1: Intensive nutrition education twice a week I2: Intensive nutrition education and supplementary food C: Nutrition education from community nutrition promotors |

3 | Food consumption Anthropometry, Nutrient intake, Education |

| Salehi M, et al. 2004 | Iran | 811 children aged <5 years, household | Intervention study (2 groups) | I: Nutrition education (n = 406) C: Usual practice (n = 405) |

12 | Anthropometry, Food consumption |

| Santos I, et al. 2001 | Brazil | 424 participants, aged <18 months, community | RCT | I: Nutritional counselling (n = 218) C: Usual practice (n = 206) |

One off training | Anthropometry |

| Sazawal S, et al. 2010 | India | 633 participants, 1–4 years, community | RCT | I: Micronutrient fortified milk (n = 316) C: Non-fortified milk (n = 317) |

12 | Anthropometry and nutrient deficiencies |

| Sekartini R et al. 2013 | Indonesia | 54 participants, aged between 5–6 years, household | RCT | I: Four different complementary milks products; Std GUM, Iso-5 GUM, Iso-5 LP GUM, Iso-2 · 5 GUM | 2 | Health |

| Siekmann JF et al. 2003 | Kenya | 555 participants aged between 5–14 years | RCT | I: Three supplementary foods groups: meat (n = 134), milk (n = 144) and energy (veg oil) supplied as a school snack in a maize stew (n = 148) C: Usual practice (n = 129) |

12 | Food consumption, nutrient intake |

| Serkatini R et al. 2013 | Indonesia | 54 participants, aged 5–6 years, household | Cross over study | I: Four different growing up milk (GUM) products – Standard GUM, Std GUM with 5 g isomaltulose per serving (Iso-5 GUM0, Iso-5 GU with lowered protein content (Iso-5 LP GUM), Std GUM with 2.5 g isomaltulose in combination with other vitamins and minerals (Iso 2.5 GUM) | 2 | Health |

| Vitolo M R et al. 2008 | Brazil | 500 individuals, all age, household | RCT | I: Breastfeeding and weaning counselling and complementary foods (163 mothers baby pairs) C: No dietary advice given (234 mother-baby pairs) | 6 | Health |

| Walsh CM, et al. 2002 | South Africa | 815 children aged 2 to 5 years, household | Intervention study (2 groups) | I: Nutrition education plus food aid C: Food aid only |

24 | Anthropometry, nutrient deficiencies |

RCT randomised control trial, CSS cross sectional study, NR: Not reported

Most of the studies (n = 18) were intervention studies (pre and post or two group comparison), ten RCT, one randomised crossover study and one crossover trial. The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 42 [36] to 40,000 [37] participants. The duration of the study also varied; from a once-off nutrition counselling training [38] to a 48 months nutrition education intervention in Nicaragua [39]. Just over half of the studies (n = 16) were conducted in Asia, nine in Africa and the other six in South American countries. Majority of these studies (n = 17) were conducted in a household settings with some in community settings.

Eighteen of the nutrition intervention studies assessed the impact of intervention on nutritional status such as growth, prevalence of stunting (low height-for-age), underweight (low weight-for-age), and wasting (low weight-for-height), 10 studies assessed food consumption and dietary diversity, nine studies assessed the impact on nutrient deficiencies, eight studies looked at health status, six at nutrient intake, five at health and nutritional knowledge, two at feeding practice and one assessed food security.

Methodology quality

Of the 123 included studies, eight studies failed to provide sufficient detail to assess their methodological quality. Information of study selection, withdrawals, blinding and confounders were particularly under-reported in the majority of studies. Because of the nature of the intervention, it was assumed that no blinding was imposed in some studies and they were therefore categorised into moderate quality study. The most common methodological problems among the weak studies were in selection bias, confounders, reliability and validity of data collection tools and blinding.

Discussion

According to our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to explore the cross-domain overlapping of multidisciplinary research projects in agriculture, nutrition, air quality and water quality. It is obvious that there is a lot of work being done in this area but from this review it clear that there is variation in not only the type of intervention, study type, sample size, duration and setting, but also in the outcome measured.

Although a wide variety of agricultural interventions such as home gardening and animal husbandry were conducted to improve household food productivity and food consumption, this review also confirms the findings of previous reviews that only few studies were measuring the impact of those interventions on nutritional status [8–10]. Of those projects that did look at the impact of agricultural intervention on nutrition, seven examined the impact on nutrient intake, nutrient deficiencies and anthropometry. In general it is predictable that increased production and consumption of food leads to better nutrition, but due to variation in study design, duration and outcome of interest measured among the included studies, it doesn’t look likely to obtain pooled estimate for studies which look at impact of intervention on nutritional health.

While looking at the air quality interventions, it is evident that interventions to improve cook stoves are the most popular interventions (83 %) and are widely being used in all over the world. This may provide the enough roofs to perform the meta-analysis. Some biogas interventions (n = 4) [20, 40–42] have been conducted to measure the multiple benefits of intervention on indoor air quality and food production (using bio-slurry). However, as they refer to different outcome measures and are measured in different ways, the available evidence does not look strong enough to perform the comprehensive analysis.

It was identified that water purification filter interventions were the most popular (n = 12) interventions for treatment of drinking water quality in LMIC. Other interventions such as chlorine tablets or solution (n = 9) and solar disinfection (n = 7) are also common in this region. Randomised controlled trial study design was the most popular among the water quality intervention as the vast majority (78 %) of the research project applied this method. So, it is more likely that effects on the drinking water quality can be summarised across studies.

Nutrition education (n = 13) and supplementary food and vitamin (n = 11) interventions were the most popular nutritional intervention in LMIC. Some intra-domain combined interventions of nutrition education and supplementary foods (n = 5) have also been piloted in some low and middle income countries to determine the impact of intervention on dietary diversity and nutrient intake.

The main finding of this review is that the vast majority (91 %) of the academic research on agricultural, nutrition and the environmental studies are simple and discipline specific with substantially fewer (n = 11) combined interventions across domains and the result is consistent with previous domain specific reviews [7, 43]. Only six studies looked at the combined impact of agricultural and nutrition education interventions, three on air and water quality interventions, one study examined the impact of a combination of agricultural and air quality interventions and one was a combined water quality and nutritional intervention. Although poor nutrition and household air pollution are the leading cause of mortality in LMIC [3], this review did not find any studies examining the impact of a combination of air quality and nutritional interventions on health. It is also striking that none of these studies investigating the combined impact of agricultural and drinking water quality interventions on human health. The evidence reviewed here shows that silo mentality is still inherent in academic research.

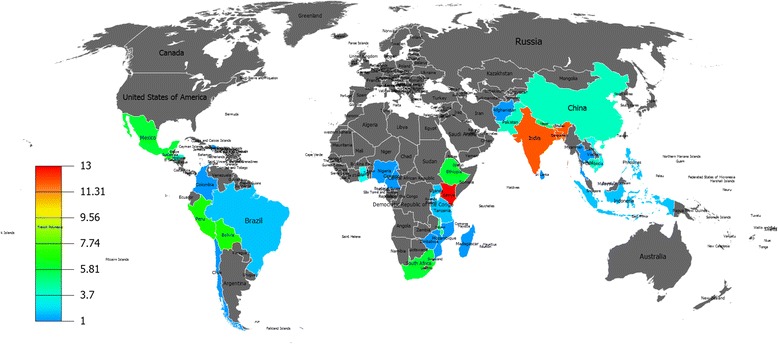

Another interesting finding of this review is that certain LMIC regions seem to focus on domain-specific interventions, with most studies in Kenya and India and only a small number in other countries (Fig. 3). Asian and African countries were the most common regional target for agricultural and nutritional studies. More than half of the agricultural (52 %) and nutritional (53 %) interventions were conducted in Asian countries with the majority of them in south Asian countries. Similarly, 48 % of agricultural and 30 % of nutritional studies were conducted in Africa with the majority of them focussed in sub-Saharan African countries such as Kenya, Ethiopia and South Africa. The majority of water quality interventions were conducted in Africa (40.6 %) followed by Asia (31.3 %) and Latin America (28.1 %). However, the majority (53 %) of interventions to improve household air quality were conducted in Latin American countries particularly in Guatemala, Peru and Mexico. This restricts the generalisability of the findings to other LMIC.

Fig. 3.

Global map highlighting the regional focus of included studies

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strength of this review is the application of a comprehensive search strategy through four databases to capture all potentially relevant peer reviewed articles. One hundred and twenty three articles representing the four different intervention domains provide ample evidence to understand the current research gap in interdisciplinary research. The use of independent reviewers throughout the review process further strengthened the methodological quality.

The main limitation of this study is that as only peer reviewed journal articles were included in this review, there is a chance of missing those studies published in developmental organisations’ reports and bulletins (publication bias). Additionally, this review focused on household and community-based studies, so there is a chance of missing some useful studies conducted in clinical settings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is evident that very little interdisciplinary research has been conducted with the majority of studies on agriculture, nutrition and the environment being discipline specific. It also seems that certain LMIC regions seem to focus on domain-specific interventions. Although a wide variety of study designs have been implemented to measure the impact of agricultural, nutrition and air quality interventions on respective outcomes of interest measured, there is still not sufficient evidence which utilises robust randomised or quasi-experimental study design.

Therefore, this review emphasizes that future research needs to focus on multi-disciplinary complex interventions with standardised outcome measures. Also, rigorous research across disciplines and sharing expertise across regions is a necessity. The next phase of this review (Meta-analysis) will identify whether eliminating silos of discipline specific research can bring a significant improvement or not.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Steve Turner and Dr Adam Price for their insightful comments that improved the manuscript. We would like to thank Heather Clark and Bimbola Kalejaiye for their help in data extraction. We are also grateful to Melanie Bickerton and Dr Amudha Poobalan for their systematic review advice.

Funding

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Authors’ contributions

SG drafted the study protocol, conducted the systematic review and wrote the manuscript. JK, SS, JS, MS and DM contributed to search strategy, assessed the quality of the data extraction process and contributed to the analysis plan and authorship of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ARI

Acute respiratory infections

- C

Control group

- CO

Carbon monoxide

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRT

Cluster-randomised trial

- CSS

Cross-sectional study

- DDS

Dietary diversity score

- HAZ

Height for age Z-score

- I

Intervention group

- LMIC

Low and middle income countries

- MeSH

Medical subject heading

- NADCC tablets

Sodium dichloroisocyanurate tablets

- NR

Not reported

- PICOS

Participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes and study design

- PM2.5

Fine particulate matter of diameter < 2.5 μm

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RCT

Rrandomised control trial

- SODIS

Solar disinfection method

- TCC

Thermo tolerant coliforms

- WAZ

Weight for age Z-score

Additional files

Ovid Embase Search Strategy. (DOCX 16 kb)

Data Extraction Sheet. (DOCX 21 kb)

Contributor Information

Santosh Gaihre, Email: santosh.gaihre@abdn.ac.uk.

Janet Kyle, Email: j.kyle@abdn.ac.uk.

Sean Semple, Email: sean.semple@abdn.ac.uk.

Jo Smith, Email: jo.smith@abdn.ac.uk.

Madhu Subedi, Email: madhu.subedi@savethechildren.org.

Debbi Marais, Email: D.Marais@warwick.ac.uk.

References

- 1.The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Strengthening the enabling environment for food security and nutrition, UN Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), 2014.

- 2.Global Food security index 2015: An annual measure of the state of global food security. The Economist Group, 2015.

- 3.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurmi OP, Semple S, Steiner M, Henderson GD, Ayres JG. Particulate matter exposure during domestic work in Nepal. Ann Occup Hyg. 2008;52:509–17. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/men026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurmi OP, Gaihre S, Semple S, Ayres JG. Acute exposure to biomass smoke causes oxygen desaturation in adult women. Thorax. 2011;66:724–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.144717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzati M, Kammen DM. Quantifying the Effects of Exposure to Indoor Air Pollution from Biomass Combustion on Acute Respiratory Infections in Developing Countries. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:481–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNICEF . Strategy for Improved Nutrition of Children and Women in Developing Countries. New York: UNICEF; 1990. pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masset E, Haddad L, Cornelius A, Isaza-Castro J. Effectiveness of agricultural interventions that aim to improve nutritional status of children: systematic review. BMJ. 2012;344:d8222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d8222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berti PR, Krasevec J, FitzGerald S. A review of the effectiveness of agriculture interventions in improving nutrition outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:599–609. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruel MT. Can Food-Based Strategies Help Reduce Vitamin A and Iron Deficiencies? A Review of Recent Evidence. Washington, DC: IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute); 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehfuess EA, Puzzolo E, Stanistreet D, Pope D, Bruce NG. Enablers and Barriers to Large-Scale Uptake of Improved Solid Fuel Stoves: A Systematic Review. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:120–30. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson N, Waters E. Guidelines for Systematic Reviews of Health Promotion and Public Health Interventions Taskforce. Guidelines for Cochrane systematic reviews of public health interventions. Health Promot Int. 2005;20:367–74. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hotz C, Loechl C, et.al. Introduction of b-Carotene–Rich Orange Sweet Potato in Rural Uganda Resulted in Increased Vitamin A Intakes among Children and Women and Improved Vitamin A Status among Children. The Journal of Nutrition. 2012. p.1871-1880. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Yakubu A, Ari MM, Ogbe1 AO, Ogah DM, Adua MM, Idahor KO, Alu SE, Ishaq AS and Salau ES. Preliminary investigation on community-based intervention through cockerel exchange programme for sustainable improved rural chicken production in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Livestock Research for Rural Development. 2014, 26. http://www.lrrd.cipav.org.co/lrrd26/10/yaku26184.htm.

- 17.Wyatt AJ, Yount KM, Null C, Ramakrishnan U, Girard AW. Dairy intensification, mothers and children: an exploration of infant and young child feeding practices among rural dairy farmers in Kenya. Maternal Child Nutr. 2015;11:88–103. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid M, Salomeyesudas B, Satheesh P, Hanley J, Kuhnlein HV. Intervention with Traditional Food as a Major Source of Energy, Protein, Iron, Vitamin C, and Vitamin A for Rural Dalit Mothers and Young Children in Andhra Pradesh, South India. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16(1):84–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolem MW, Huq N, Gorstein J, Burger S, Kahn T, Islam N, et al. Production of fruits and vegetables at the homestead is an important source of Vitamin A among women in rural Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50S:62–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chowdhury Z, Le LT, Masud AA, Chang KC, Alauddin M, Hossain M, et al. Quantification of indoor air pollution from using cookstoves and estimation of its health effects on adult women in Northwest Bangladesh. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2012;12(4):463–75. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartinger SM, Lanata CF, Gil AI, Hattendorf J, Verastegui H, Mausezahl D. Combining interventions: improved chimney stoves, kitchen sinks and solar disinfection of drinking water and kitchen clothes to improve home hygiene in rural Peru. J Field Actions. 2012;6:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCracken JP, Smith KR. Emissions and efficiency of improved woodburning cookstoves in Highland Gatemala. Environ Int. 1998;24(7):739–47. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(98)00062-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris SA, Weeks JB, Chen JP, Layde P. Health effects of an efficient vented stove in the highlands of Guatemala. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(4):421–32. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.523708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Mulholland JA, Romanoff LC, Pittman EN, Trinidad DA, Lewin MD, et al. Evaluation of exposure reduction to indoor air pollution in stove intervention projects in Peru by urinary biomonitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites. Environ Int. 2011;37(7):1157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pndey MR, Neupane RP, Gautam A, Shrestha B. The Effectiveness of Smokeless Stoves in Reducing Indoor Air Pollution in a Rural Hill Region of Nepal. Mountain Res Develop. 1990;10(4):313–20. doi: 10.2307/3673493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry FJ, Huttly SRA, Patwary Y, Aziz KMA. Environmental sanitation, food and water contamination and diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh. Epidemiol Infect. 1990;104(02):253–9. doi: 10.1017/S0950268800059422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Aceituno AM F, Stauber CE, Walters AR, Meza Sanchez RE, Sobsey MD. A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Plastic-Housing BioSand Filter and Its Impact on Diarrheal Disease in Copan, Honduras. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(6):913–21. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrett V, Ogutu P, Mabonga P, Ombeki S, Mwaki A, Aluoch G, Phelan M, Quick RE. Diarrhoea prevention in a high-risk rural Kenyan population through point-of-use chlorination, safe water storage, sanitation, and rainwater harvesting. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:1463–71. doi: 10.1017/S095026880700026X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christen A, Navarro CM, Mausezahi D. Safe drinking water and clean air: An experimental study evaluating the concept of combining household water treatment and indoor air improvement using the Water Disinfection Stove (WADIS) Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2009;212(5):562–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosa G, Majorin F, Boisson S, Barstow C, Johnson M, Kirby M, Ngabo F, Thomas E, Clasen T. Assessing the Impact of Water Filters and Improved Cook Stoves on Drinking Water Quality and Household Air Pollution: A Randomised Controlled Trial in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graf J, Togouet SZ, Kemka N, Niyitegeka D, Meierhofer R, Pieboji JG. Health gains from solar water disinfection (SODIS): evaluation of a water quality intervention in Yaoundé, Cameroon. J Water Health. 2010;8(4):779–96. doi: 10.2166/wh.2010.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boisson S, Kiyombo M, Sthreshley L, Tumba S, Makambo J, Clasen T. Field Assessment of a Novel Household-Based Water Filtration Device: A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial in the Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.English R, Badcock JC, Giay T, Ngu T, Waters AM, Bennett SA. Effect of nutrition improvement project on morbidity from infectious diseases in preschool children in Vietnam: comparison with control commune. BMJ. 1997;315:1122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7116.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faber M, Phungula MAS, Venter SL, Dhansay MA, Benade AJ S. Home gardens focusing on the production of yellow and dark-green leafy vegetables increase the serum retinol concentrations of 2–5-y-old children in South Africa. Am Soc Clin Nutr. 2002;76(5):1048–54. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fenn B, Bulti AT, nduna T, Duffield A and Watson F. An evaluation of an operations research project to reduce childhood stunting in a food-insecure area in Ethiopia. 2012. 15;9: p. 1746–1754. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Creed-Kanashiro HM, Bartoini RM, Fukumoto MN, Uribe TG, Robert RC, Bentley ME. Formative research to develop a nutrition education intervention to improve dietary iron intake among women and adolescent girls through community kitchens in Lima Peru. J Nutr. 2003;133(11):3987S–91. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3987S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pant CR, Pokharel GP, Curtale F, Pokhrel RP, Grosse RN, Lepkowski J, Muhilal, Bannister M, Gorstein J, Pak-Gorstein S, Atmarita, Tilden RL. Impact of nutrition education and mega-dose vitamin A supplementation on the health of children in Nepal. Bull World Health Org. 1996;74(5):533–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santos I, Victora CG, Martines J, Gonçalves H, Gigante DP, Valle NJ, Pelto G. Nutrition counseling increases weight gain among Brazilian children. J Nutr. 2001;131:2866–73. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore JB, Pawloski L, Rodriguez C, Lumbi L, Ailinger R. The Effect of a Nutrition Education Program on the Nutritional Knowledge, Hemoglobin Levels, and Nutritional Status of Nicaraguan Adolescent Girls. Public Health Nurs. 2009;26(2):144–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dohoo C, Guernsey J.R, Critchley K, and VanLeeuwen J. Pilot study on the impact of biogas as a fuel source on respiratory health of women on rural Kenyan smallholder dairy farms. J Environ Public Health. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Garfi M, Ferrer-Marti L, Perez I, Flotats X, Ferrer I. Codigestion of cow and guinea pig manure in low-cost tubular digesters at high altitude. Ecol Eng. 2011;37:2066–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou Y, Zou Y, Li X, Chen S, Zhao Z, He F, et al. Lung function and incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after improved cooking fuels and kitchen ventilation: A 9 year prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strunz EC, Addiss DG, Stocks ME, Ogden S, Utzinger J, Fewwman MC. Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.