Abstract

Background

The aim of this case report is to discuss the issue of nutritional therapy in patients taking warfarin. Patients are often prescribed vitamin K free diets without nutritional counseling, leading to possible health consequences.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old woman with obesity and hypertension was prescribed a low calorie diet by her family doctor in an effort to promote weight loss. After a pulmonary embolism, she was placed on anticoagulant therapy and on hospital discharge she was prescribed a vitamin K free diet to avoid interactions. Given poor control of her anticoagulant therapy, she was referred to our Nutritional Unit outpatients’ service.

Conclusions

This case illustrates the importance of a thorough medical nutrition assessment in the management of patients with obesity and the need for a change in the dietary approach of nutritional therapy in the management of vitamin K anticoagulant therapy. In patients taking warfarin, evidence suggest that the aim of nutritional therapy should be to keep dietary intake of vitamin K constant.

Keywords: Obesity, Pulmonary embolism, Nutrition, Vitamin K, Nutritional assessment, Diet

Background

A number of studies have found a significant increased risk for deep venous thromboembolism (VTE), and/or pulmonary embolism in people with obesity [1–6]. A hazard ratio of 2.7 for a body mass index >40 has been reported by the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) [2].

Besides obesity, many other factors contribute to increasing the VTE risk: smoking, increasing age, patients with factor V Leiden or pro-thrombin gene mutation [7] and oral contraceptive therapy [8].

Patients who had a VTE episode are usually treated with oral anticoagulants. Their use is challenging because the therapeutic range is narrow and dosing is affected by multiple factors including genetic variation, drug interactions, and diet [9]. Moreover, compared to normal weight, obese and morbidly obese patients had a decreased initial response to warfarin [10, 11].

Prothrombin time is an assay evaluating the extrinsic pathway of coagulation. The international normalized ratio (INR) is used to standardize the prothrombin time and the optimal intensity of anticoagulant therapy corresponds to a target INR of 2.5 (range, 2.0 to 3.0) [12].

Both prophylaxis and treatment of VTE and pulmonary embolism (PE) with anticoagulants are associated with significant risks of major and fatal hemorrhage. Both anticoagulant treatment and lifestyle changes should be individualized to prevent further complications [9, 12].

Two major factors that may lead to poor INR control are failure to take warfarin appropriately and very low dietary vitamin K intake/vitamin K deficiency. The nutritional management of these patients is therefore extremely complicated.

We hereby describe a case of pulmonary embolism in an obese patient providing key insights into treatment with medical nutrition therapy and anticoagulants.

Case presentation

In-patient diagnosis and treatment

In January 2015, a 52-year old woman with obesity and hypertension was admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit of a hospital in Northern Italy for acute dyspnea and chest pain. Computed tomography angiography revealed filling defects affecting the right and left branches of the pulmonary artery suggestive of pulmonary embolism (PE). She was initially treated with intravenous heparin sodium and bridged to warfarin as a long-term anticoagulant. Before the hospital discharge she was prescribed a vitamin K free diet reported in Table 1(b). Although the general recommendation is to maintain a stable and consistent intake of Vitamin K, in the clinical practice patients are suggested to avoid food high in vitamin K and they are given general dietetic guidelines.

Table 1.

Total energy and nutrient composition of three diets prescribed to a 52-year-old woman before (a) and after (b, c) a pulmonary embolism

| (a) Low calorie diet | (b) vitamin K free diet | (c) NU diet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients | Amount (units) | % of total energy | Amount (units) | % of total energy | Amount (Units) | % of total energy |

| Energy | 1044 (kcal) | 922 (kcal) | 1688 (kcal) | |||

| Proteins | 50 (g) | 19 | 30 (g) | 13 | 77 (g) | 18 |

| Animal proteins | 34 (g) | 17 (g) | 46 (g) | |||

| Vegetable proteins | 16 (g) | 13 (g) | 31 (g) | |||

| Fats | 37 (g) | 32 | 37 (g) | 36 | 50 (g) | 26 |

| Animal fats | 13 (g) | 32 (g) | 12 (g) | |||

| Vegetable fats | 24 (g) | 5 (g) | 38 (g) | |||

| Saturated fats | 11 (g) | 9.5 | 18 (g) | 17 | 11 (g) | 6.0 |

| Monounsaturated fats | 20 (g) | 17 | 10 (g) | 10 | 30 (g) | 16.0 |

| Linoleic acid | 3 (g) | 2.5 | 3.0 (g) | 3.0 | 6 (g) | 3.0 |

| Linolenic acid | 1 (g) | 1.0 | 1.0 (g) | 1.0 | 1 (g) | 0.5 |

| Polyunsaturated fats | 4 (g) | 3.5 | 4.0 (g) | 4.0 | 8 (g) | 4.0 |

| Cholesterol | 97 (mg) | 103 (mg) | 236 (mg) | |||

| Carbohydrates | 139 (g) | 50 | 127 (g) | 51 | 250 (g) | 56 |

| Soluble carbohydrates | 42 (g) | 15 | 41 (g) | 17 | 52 (g) | 11 |

| Dietary fiber | 16 (g) | 14 (g) | 23 (g) | |||

| Thiamine | 0.6 (mg) | 1.1 (mg) | 1.0 (g) | |||

| Vitamin B6 | 1.5 (mg) | 1.1 (mg) | 1.9 (g) | |||

| Folate | 253 (μg) | 87 (μg) | 264 (g) | |||

| Vitamin K | 273 (μg) | 23 (μg) | 58 (μg) | |||

| Sodium | 1880 (mg) | 3415 (mg) | 1460 (g) | |||

a) Low calorie diet prescribed the patient by her family doctor before the pulmonary embolism. b) Vitamin K free diet prescribed upon discharge to the patient taking oral anticoagulants after the pulmonary embolism. c) Diet prescribed by the Nutritional Unit (NU) to the same patient: moderately low calorie with low vitamin K (planning a slow and continuous increase of vitamin K daily intake up to 150 μg per day)

Diet composition analyzed by trained dietitians using a dedicated software developed by our Nutrition Unit incorporating “Food Composition Database for Epidemiological Studies in Italy” by Gnagnarella P, Salvini S, Parpinel M. Version 1.2015 Website http://www.bda-ieo.it/

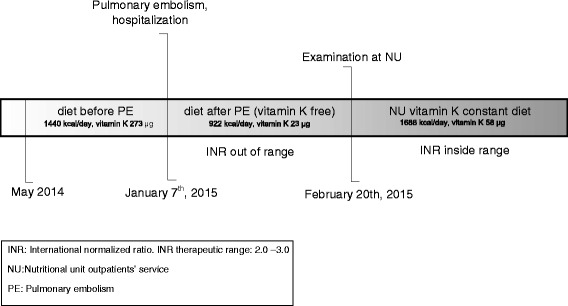

During her first month as an outpatient it was very difficult to get her INR into the therapeutic range. Her family doctor recognized that poor nutrition is an important factor in establishing therapeutic levels and she was referred to our Nutritional Unit outpatient service (NU) for a nutritional assessment and specific medical nutrition therapy. Figure 1 shows the timeline of present illness, intervention and follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Timeline

Outpatient nutritional unit

Medical history

She reported a long-term history of obesity and hypertension. She denied allergies and cigarette smoking and reported a sedentary lifestyle with no physical activity. The patient was nulliparous and had been on oral contraceptive therapy since the age of 25. The therapy was discontinued by her physicians after her PE. At the time of the examination she was on nebivolol, alprazolam and warfarin adjusted for INR, as well as vitamin B12 and folate supplementation (400 μg). Her family history was negative for thrombosis and cardiovascular diseases.

Weight history

The patient reported that she began struggling with obesity during her childhood. She began adulthood at a weight of 90 kg (BMI 35.0 kg/m2). Maximum and minimum weight reported by the patient were 117.5 kg (BMI 45.9 kg/m2) and 69 kg (BMI 27.0 kg/m2) respectively at 51 and 26 years of age. Soon after reaching her peak weight she started a hypocaloric diet as suggested by her family doctor, Table 1(a).

Nutritional assessment

Anthropometrical, bioelectrical and clinical findings at physical examination are showed in Table 2 with biochemical analyses. The patient’s BMI was greater than 34.99 Kg/m2, class II obesity according to WHO classification [13]. Fat mass was estimated by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) using a BIA 101 Akern s.r.l. (Italy). The exam, performed under standardized conditions [14] revealed an important increase in fat mass although a normal state of hydration. The waist-to-hip ratio indicates an android fat distribution. Evidence of increased visceral fat depot is shown by waist circumference measurement.

Table 2.

Clinical findings and blood test results at the time of nutritional unit outpatient service examination

| Blood test results | |

|---|---|

| Variables | Values (Units) |

| Hemoglobin | 13.4 (g/dl) |

| Hematocrit | 40.8 (%) |

| Mean cellular volume | 83.2 (fl) |

| Platelets | 250 (1000/ μl) |

| Leukocytes | 8.81 (1000/ μl) |

| International normalized ratio | 2.06 |

| Antithrombin III actvity | 99 (%) |

| D-dimer | 378 (μg/l) |

| Anti-cardiolipin antibodies | negative |

| Anti-beta 2-glycoprotein I antibodies | negative |

| Homocysteine | 21 (μmol/L) |

| Folate | 5.8 (ng/ml) |

| Vitamin B12 | 372 (pg/ml) |

| Vitamin D | 7.4 (ng/ml) |

| Parathormone | 35.3 (pg/ml) |

| Glucose | 88(mg/dl) |

| Insulin | 18.6 (mIU/ml) |

| Homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index | 4.04 |

| Magnesium | 2 (mg/dl) |

| Prealbumin | 0.23 (g/l) |

| Weight: 93.6 kg Height: 160 cm Body mass index: 36.6 kg/m2 aBlood pressure: 120/70 mmHg Waist circumference: 122 cm Hip circumference: 118 cm Waist-to-Hip ratio: 1.03 |

bResting Energy Expenditure (REE): 1515 kcal/day cEnergy Expenditure: 1818 kcal/day dBIA for BC FM = 48.2 % PhA = 5.5° |

VR506Q mutation of factor V (Leiden): absent

VH1299R mutation of factor V: absent

G20210 of protrhombin gene (factor II): absent

Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene mutation: absent

Fifty-two-year old female patient with obesity and hypertension taking anticoagulants due to a history of a recent pulmonary embolism

ataking hypertension medication

bMifflin equation [14].

cEE = REE x Activity Factor Category Definition (1.2 for sedentary)

dBioelectrical Impedance Analysis for Body Composition (BIA 101 Akern s.r.l. – Italy); FM = Fat mass, PhA = Phase angle

Resting energy expenditure (REE) has been estimated by means of Mifflin predictive equations [15], which is more likely than the other known equations to estimate REE to within 10 % [16].

Before the PE, the patient was following the diet reported in Table 1(a), which was prescribed by her family doctor. Total energy and nutrient intakes were analyzed by trained dietitians using dedicated software developed by our Nutrition Unit incorporating “Food Composition Database for Epidemiological Studies in Italy” by Gnagnarella P, Salvini S, Parpinel M. (Version 1.2015 Website http://www.bda-ieo.it/).

The diet followed by the patient before the PE was a low-calorie diet that did not satisfy the dietary recommendations for protein and micronutrient intake (LARN 2014) [17].

The nutrient composition of the diet prescribed to the patient after the PE upon hospital discharge is reported in Table 1(b).

Vitamin K free diets typically are lacking in vegetables, with a consequent insufficient dietary fiber and folate intake. Protein intake prescribed to the patient was far lower than any standard recommendation (less than 0.33 g/ kg of body weight) while the total fat and in particular the saturated ones were higher than the standard recommendations (LARN 2014 and ESC 2012 [18]).

The patient’s laboratory values at the time of her first examination in our NU are shown in Table 2. She had high levels of homocysteine and low prealbumin. She also was vitamin D deficient as can be seen in patients with obesity [19].

Both folate and vitamin B12 concentrations levels were within the accepted normal ranges, likely due to her supplementation and not her dietary intake.

Therapeutic intervention

After the nutritional assessment, a balanced, low-calorie diet was prescribed, with particular attention to sodium and soluble carbohydrates intake. The protein intake prescribed was equivalent to 0.8 g/Kg of actual body weight. The nutritional composition of the diet prescribed at our NU is shown in Table 1(c).

In order to avoid a sharp change in vitamin K intake the starting vitamin K intake prescribed was low (57.88 μg per day). Gradually her vitamin K intake was increased to 150 μg per day. Folate supplementation was prescribed (400 μg per day) as well as vitamin D supplementation (300,000 IU every 3 months for 9 months) [20].

The benefit of having her seen in the NU was that our staff was able to take the appropriate amount of time to counsel the patient and to ensure she understood the dietary guidelines and risk of complications in order to transform the acquired knowledge into behavior change and to achieve greater adherence.

Follow-up and outcomes

The patient’s INR values were tested on a regular base. As shown in Table 3, the INR values were therapeutic and remained constant immediately following initiation of the prescribed diet.

Table 3.

INR testing in a 52-year old woman taking oral anticoagulants due to a recent history of pulmonary embolism

| Date (2015) | Weekly warfarin dose (mg) | International normalized ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 01/19 | 41.75 | 1.82 |

| 01/26 | 43.75 | 1.80 |

| 02/02 | 45 | 3.16 |

| 02/09 | 43.75 | 1.82 |

| 02/20 | 43.75 | 2.06 |

| 02/27 | 41.75 | 2.23 |

| 03/13 | 41.75 | 2.16 |

| 03/20 | 43.75 | 2.43 |

| 04/03 | 43.75 | 2.04 |

Before February 20th, she was fallowing a vitamin K free diet. After February 20th, she was following the diet prescribed at our nutritional unit (NU), with stable content of vitamin K

INR = International normalized ratio. INR therapeutic range: 2.0 – 3.0

Warfarin dose refers to the week prior to the INR value

Conclusion

This case study presents the nutritional issues of anticoagulants in the setting of obesity. We present a case of a 52 year old female patient with obesity and hypertension taking anticoagulants due to a history of a recent PE treated in our NU outpatient service.

She had no inherited thrombophilia nor a previous hospitalization, immobility, trauma, surgery, malignancy or infection before the PE, and we hypothesize that perhaps this adverse event might have been caused by the combination of obesity, oral contraceptive therapy and sedentary lifestyle. Indeed, there is strong evidence that oral contraceptives entail a statistically significant risk of VTE, which is particularly high among women with high body mass indices and a history of cigarette smoking [21, 22]. Previous studies demonstrate that oral contraceptives modify the effect of obesity on the risk of venous thrombosis, with a 10-fold increased risk among women on oral contraceptives with a BMI >25 kg/m2 compared to normal weight women not using oral contraceptives [8, 23].

Obesity is considered a risk factor for VTE and PE and is associated with an increase of procoagulant factors (factor VII, factor VIII, factor XII and fibrinogen) [24–26] and with venous stasis [2] in turn increasing the thrombotic risk (Virchow’s triad). Analysis of data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey indicated an increased relative risk for VTE (RR 2.50, 95 CI 2.492.51) and PE (RR 2.21, 95 % CI 2.202.23) in subjects with obesity [27].

Our patient reported a long history of obesity and 7 months before the PE episode she was put on a low calorie diet without a formal nutritional assessment of her specific nutritional needs.

As shown in Table 1, the diet before the PE did not satisfy fiber, protein and micronutrients needs for this patient likely due to the low fruit and vegetable intake.

The “Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE)” prospective study [28] found a diet with more fruits, vegetables, and fish, and less red and processed meat was associated with a lower VTE incidence. Data about the relationship of diet to VTE risk comes from: historical observations about the incidence of PE under wartime conditions, including food rationing in early 20th century European cities; prospective observational studies of diet and lifestyle factors associated with VTE [9]; case–control studies of VTE patients looking at lipid profiles, inflammation markers, and coagulation variables; comparisons among the general population on various diets regarding lipid profiles, inflammation markers, and coagulation variables [9]. It is possible that the link between diet and VTE is potentially through other aspects of their lifestyle: people who are less health conscious may be less concerned about a healthy diet and may place less importance as well on physical activity, exposing them to a greater risk of prolonged non-pulsatile venous blood flow and consequent valve pocket hypoxemia. According to the valve cusp hypoxia hypothesis (VCHH) deep venous thromboembolism may occur wherever sustained non-pulsatile venous blood flow leads to suffocating hypoxemia in the valve pockets, resulting in hypoxic injury to and hence death of the inner endothelium of the cusp leaflets [9].

Furthermore both diets before and after the PE were very high in sodium intake, which would be inappropriate in a patient with a long history of hypertension. Our patient also had hyperhomocysteinemia, despite vitamin B12 and folate supplementation. High plasma concentration of homocysteine may be due to genetic defects in the enzymes involved in homocysteine metabolism (i.e. homozygosity for the thermolabile variant of methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase, MTHFR -TT genotype), nutritional deficiencies in vitamin cofactors (folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 [29–32]), or other factors including some drugs such as oral contraceptives. Given her absence of MTHFR mutation, it is most likely her hyperhomocysteinemia was due to both the long-term oral contraceptive therapy and to a low folate diet. Since prothrombotic effects of homocysteine have been demonstrated [33–36], it is important to include this parameter in the nutritional assessment. Indeed, a proper assessment of patients with obesity should include vitamin status especially in those at risk of subclinical deficiencies.

This case illustrates the need for a thorough medical nutrition assessment in the management of patients with obesity. Weight loss therapy, cannot be focused only on lowering calories, but should include care to meet macro and micronutrients recommendations even through supplementation, if necessary.

A vitamin K free diet, such as Table 1(b), is very often prescribed to patients who had a PE and are on warfarin. Individuals on warfarin generally are sensitive to fluctuations in vitamin K intake, and adequate INR control requires close attention to the amount of vitamin K ingested from dietary and other sources [37]. This case report highlights the need for a change in the clinical approach of patients taking warfarin. The aim of nutritional therapy should be to keep dietary intake of vitamin K constant rather than to exclude it completely from the diet, which is not uncommon in the clinical practice. Several studies have demonstrated the relationship between vitamin K intake and INR control [38–40] in particular suggesting patients should be advised to consume a healthy diet, and they should not avoid fruits and vegetables for fear of altering the INR.

Despite the evidence, it is common practice to suggest vitamin K free diets to all patients on oral anticoagulants therapy. The main consequence of this recommendation is the exclusion of vegetables and fruit from the diet, resulting in nutrient deficiencies and impaired health status. We should not forget that eliminating these very important food groups puts our patients at further risk.

In the field of cardiovascular risk and diseases, medical nutrition therapy plays a crucial role in providing both prevention and therapy. A correct and complete nutritional assessment is essential for effective therapy. Nutritional intervention should be tailored to the individual patient and should provide the correct amount of macronutrients, micronutrients and vitamin or mineral supplementation if needed.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None of the authors received funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to data collections, analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed in drafting the article and to the critical revision of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Abbreviations

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- BIA

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

- BMI

Body mass index

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

- INR

International Normalized Ratio

- LITE

Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology

- MTHFR

Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase

- NU

Nutritional Unit outpatient service

- PE

Pulmonary embolism

- REE

Resting energy expenditure

- VCHH

Valve cusp hypoxia hypothesis

- VTE

Venous thromboembolism

- WHO

World Health Organization

References

- 1.Samama MM. An epidemiologic study of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in medical outpatient: the Sirius study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai AW, Cushman M, Rosamond WD, Heckbert SR, Polak JF, Folsom AR. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism incidence: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1182–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ageno W, Becattini C, Brighton T, Selby R, Kamphuisen PW. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2008;117(1):93–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.709204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holst AG, Jensen G, Prescott E. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism: results from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;121(17):1896–903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.921460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldhaber SZ, Savage DD, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP, Kannel WB, McNamara PM, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary embolism. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1983;74(6):1023–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Severinsen MT, Kristensen SR, Johnsen SP, Dethlefsen C, Tjønneland A, Overvad K. Anthropometry, body fat, and venous thromboembolism: a Danish follow-up study. Circulation. 2009;120(19):1850–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Severinsen MT, Overvad K, Johnsen SP, Dethlefsen C, Madsen PH, Tjønneland A, et al. Genetic susceptibility, smoking, obesity and risk of venous thromboembolism. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):273–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomp ER, le Cessie S, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. Risk of venous thrombosis: obesity and its joint effect with oral contraceptive use and prothrombotic mutations. Br J Haematol. 2007;139(2):289–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cundiff DK, Agutter PS, Malone PC, Pezzullo JC. Diet as prophylaxis and treatment for venous thromboembolism? Theor Biol Med Model. 2010;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallace JL, Reaves AB, Tolley EA, Oliphant CS, Hutchison L, Alabdan NA, et al. Comparison of initial warfarin response in obese patients versus non-obese patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;36(1):96–101. doi: 10.1007/s11239-012-0811-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kearon C. Long-term management of patients after venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2004;110(9 Suppl 1):I10–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140902.46296.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domienik-Karłowicz J, Pruszczyk P. The use of anticoagulants in morbidly obese patients. Cardiol J. 2016;23(1):12–6. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2015.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . Western pacific region, international association for the study of obesity, international obesity task force. Redefining obesity and its treatment. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Consensus NIH. Statement. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in body composition measurement. National institutes of health technology assessment conference statement. December 12–14, 1994. Nutrition. 1996;12(11–12):749–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mifflin MD, St Jeor ST, Hill LA, Scott BJ, Daugherty SA, Koh YO. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51(2):241–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frankenfield D, Roth-Yousey L, Compher C. Comparison of predictive equations for resting metabolic rate in healthy nonobese and obese adults: a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(5):775–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Società Italiana di Nutrizione Umana, SINU . Livelli di Assunzione di Riferimento di Nutrienti ed energia per la popolazione italiana, IV revisione. Milano: SICS Editore; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.EHS ESC guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias 2011. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–1818. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira-Santos M, Costa PR, Assis AM, Santos CA, Santos DB. Obesity and vitamin D deficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):341–9. doi: 10.1111/obr.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adami S, Romagnoli E, Carnevale V, Scillitani A, Giusti A, Rossini M, et al. Guidelines on prevention and treatment of vitamin D deficiency. Italian Society for Osteoporosis, Mineral Metabolism and Bone Diseases (SIOMMMS) Reumatismo. 2011;63(3):129–47. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.No authors listed Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: results of international multicentre case–control study. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1995;346(8990):1575–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drife J. Thromboembolism. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:177–90. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdollahi M, Cushman M, Rosendaal FR. Obesity: risk of venous thrombosis and the interaction with coagulation factor levels and oral contraceptive use. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:493–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Pergola G, De Mitrio V, Giorgino F, Sciaraffia M, Minenna A, Di Bari L, et al. Increase in both pro-thrombotic and anti-thrombotic factors in obese premenopausal women: relationship with body fat distribution. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(7):527–535. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowles LK, Cooper JA, Howarth DJ, Miller GJ, MacCallum PK. Associations of haemostatic variables with body mass index: a community-based study. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2003;14(6):569–73. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosito GA, D’Agostino RB, Massaro J, Lipinska I, Mittleman MA, Sutherland P, et al. Association between obesity and a prothrombotic state: the Framingham Offspring Study. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91(4):683–9. doi: 10.1160/th03-01-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein PD, Beemath A, Olson RE. Obesity as a risk factor in venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2005;118(9):978–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steffen LM, Folsom AR, Cushman M, Jacobs DR, Jr, Rosamond WD. greater fish, fruit, and vegetable intakes are related to lower incidence of venous thromboembolism. The Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology. Circulation. 2007;115(2):188–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.641688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson K, Arheart K, Refsum H, Brattström L, Boers G, Ueland P, et al. Low circulating folate and vitamin B6 concentrations: risk factors for stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and coronary artery disease. European COMAC Group. Circulation. 1998;97(5):437–43. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB, Sampson L, Colditz GA, Manson JE, et al. Folate and vitamin B6 from diet and supplements in relation to risk of coronary heart disease among women. JAMA. 1998;279(5):359–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.5.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voutilainen S, Rissanen TH, Virtanen J, Lakka TA, Salonen JT. Low dietary folate intake is associated with an excess incidence of acute coronary events: The Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Circulation. 2001;103(22):2674–80. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.22.2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vermeulen EG, Stehouwer CD, Twisk JW, van den Berg M, de Jong SC, Mackaay AJ, et al. Effect of homocysteine-lowering treatment with folic acid plus vitamin B6 on progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9203):517–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Obaidi MK, Philippou H, Stubbs PJ, Adami A, Amersey R, Noble MM, et al. Relationships between homocysteine, factor VIIa, and thrombin generation in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2000;101(4):372–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.4.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.den Heijer M, Koster T, Blom HJ, Bos GM, Briet E, Reitsma PH, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia as a risk factor for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(12):759–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603213341203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ray JG. Meta-analysis of hyperhomocysteinemia as a risk factor for venous thromboembolic disease. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(19):2101–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.19.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.den Heijer M, Rosendaal FR, Blom HJ, Gerrits WB, Bos GM. Hyperhomocysteinemia and venous thrombosis: a meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 1998;80(6):874–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohde LE, de Assis MC, Rabelo ER. Dietary vitamin K intake and anticoagulation in elderly patients. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328011c46c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leblanc C, Presse N, Lalonde G, Dumas S, Ferland G. Higher vitamin K intake is associated with better INR control and a decreased need for INR tests in long-term warfarin therapy. Thromb Res. 2014;134(1):210–2. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harshman SG, Saltzman E, Booth SL. Vitamin K: dietary intake and requirements in different clinical conditions. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17(6):531–8. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes MV, Hunt BJ, Shearer MJ. The role of dietary vitamin K in the management of oral vitamin K antagonists. Blood Rev. 2012;26(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.