Abstract

Background

Various drugs are administered for the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) in Japan. However, there have been no surveys undertaken to identify these drugs or their frequency of prescription. Therefore, we administered a questionnaire survey to the diplomates of the Subspecialty Board of Japanese Society of Medical Oncology (JSMO) to investigate the frequency of administration of different drugs for the management of CIPN in Japan.

Methods

We investigated the use of vitamin B12, antiepileptic agents such as pregabalin, duloxetine, antidepressants other than duloxetine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids and the Kampo compound goshajinkigan in a questionnaire employing a three-step scale wherein A implies routine or prophylactic administration, B implies occasional administration and C implies infrequent administration.

Results

Considering responses A and B together, the most frequently administered drugs for the treatment of numbness were antiepileptic drugs such as pregabalin (A+B=98.7%), vitamin B12 (74.7%), Kampo compounds (58.7%) and duloxetine (46.8%). The most frequently prescribed drugs for pain were NSAIDs (97.7%), followed by opioids (83.1%) and finally antiepileptic drugs (82.1%).

Conclusions

Various drugs are frequently administered for CIPN. In addition, it was found that marked differences exist between the drugs targeted on numbness and pain.

Keywords: CIPN, chemotherapy, neuropathy, guideline, questionnaire

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

It is known that various drugs are administered for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN); however, there were no surveys to identify the actual drugs prescribed.

What does this study add?

Various drugs are frequently administered for CIPN. In addition, it was found that marked differences exist between the drugs targeted on numbness and pain.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

We feel that it would be necessary to distinguish pain and numbness for management of CIPN in future blind randomised controlled trial to develop guidelines in Japan.

Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a common adverse event in response to chemotherapy and often results in the cessation of treatment. However, global guidelines for the treatment of CIPN did not exist for a long time owing to a lack of data from reliable clinical trials.1–3 The positive effects of duloxetine were recently demonstrated in a phase III clinical trial, and subsequently the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines were released for the management of CIPN.4 5

In Japan, while various drugs are administered for the treatment of CIPN, there has been no survey to identify their rates of prescription. To develop feasible clinical guidelines for CIPN management in Japan in the near future, the true situation regarding drugs prescribed for CIPN must be clarified.

With this objective, we administered a questionnaire survey to the diplomates of the Subspecialty Board of Medical Oncology in order to understand accurately the current situation on the administration of drugs for CIPN treatment in Japan. The ASCO guidelines did not distinguish between CIPN-derived symptoms of pain and those of numbness. In our evaluation of CIPN treatment in Japan, we considered pain and numbness as separate symptoms.

Methods

Outline of questionnaire

Please answer the following two questions about yourself.

-

Specialty

□ Thoracic oncology □ Gastrointestinal oncology □ Haemato–oncology □ Breast cancer □ Others

-

Current age (in years)

□ 40 or less □ 40–49 □ 50 or above

Main questions

Do you administer drugs for peripheral neuropathy induced by anticancer agents such as platinum, taxane or vinca alkaloids? (Please disregard any problems associated with insurance.)

Choose one of the following options:

Routine or prophylactic administration

Occasional, multiple administration

If you answer A for a drug, you may not choose option B for the same drug. If you choose neither A nor B for a drug, your answer will be considered as C: infrequent administration.

Drugs surveyed in this study include vitamin B12, antiepileptic drugs gabapentin and pregabalin, duloxetine, antidepressants other than duloxetine (amitriptyline), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, Kampo compounds (goshajinkigan) and others.

Each drug was separately evaluated via the questionnaire for numbness and for pain.

Distribution and analysis of questionnaires

We sent the questionnaires via email to 971 diplomates of the Subspecialty Board of Medical Oncology of the Japanese Society of Medical Oncology (JSMO). Approval for the survey was obtained from the scientific programme committee of JSMO prior to sending the questionnaires.

The questionnaire was distributed on 18 February 2015 with the deadline for responses set as 6 March 2015. Results were analysed using the SurveyMonkey Online Questionnaire Tool (SurveyMonkey Inc). Approval for the publication of the results was obtained from the board members of JSMO (23 November 2015).

Results

Structure of answerer

Three hundred responses in 971 distributions were valid, giving a response rate of 30.9%. Thirty-three per cent of the respondents were aged 40 years or less, 46% were aged 40–49 years, and 21% were aged 50 years or more. In terms of specialty, 32.2%, 31.2%, 21.4%, 7.4% and 7.8% specialised in gastrointestinal oncology, thoracic oncology, haemato–oncology, breast cancer and others, respectively.

Administration preference for numbness and pain

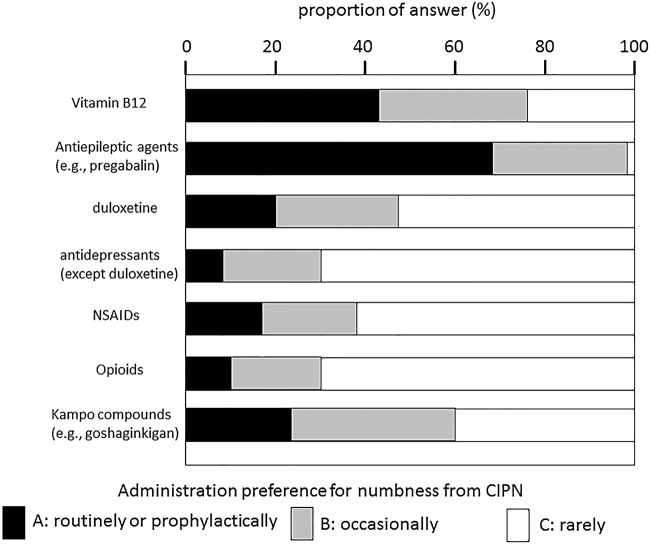

The most frequently administered drugs for the treatment of numbness were antiepileptic drugs such as pregabalin (A=68.3%, A+B=98.7%), vitamin B12 (A=42.7%, A+B=74.7%), Kampo compounds such as goshajinkigan (A=24.1%, A+B=58.7%) and duloxetine (A=21.0%, A+B=46.8%), as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Administration preference for numbness from CIPN. CIPN, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

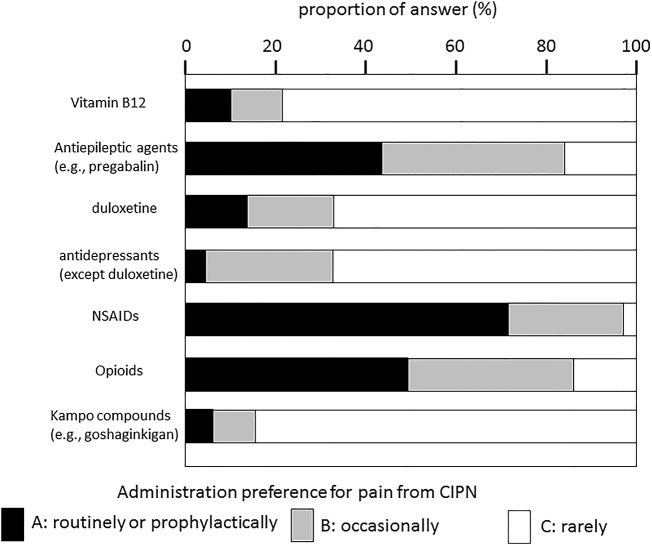

For pain, the most frequently prescribed drugs were NSAIDs (A=71.7%, A+B=97.7%) followed by opioids (A=40.9%, A+B=83.1%) or antiepileptic drugs (A=42.6%, A+B=82.1%), as shown in figure 2. Three respondents (0.1%) also mentioned administering acetaminophen for both numbness and pain.

Figure 2.

Administration preference for pain from CIPN.CIPN, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

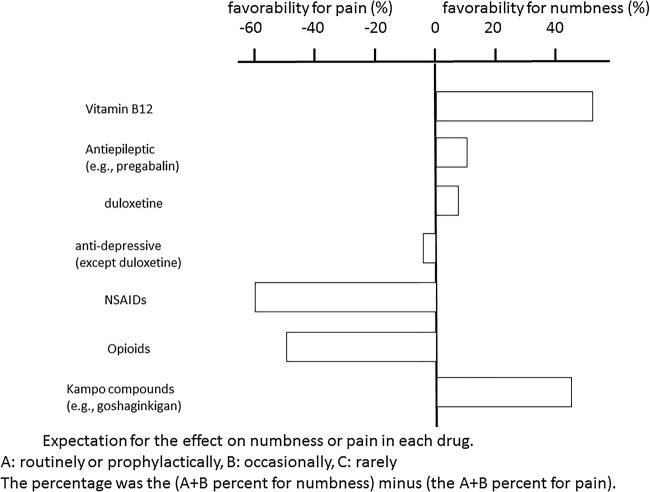

Expectation for the effect on numbness or pain in each drug

Marked differences were observed in the frequency of administration between the drugs administered for the management of numbness and for pain.

For a drug, an overall value indicating frequency of administration was calculated by subtracting the percentage of (A+B) for pain treatment frequency from the percentage of (A+B) for numbness treatment frequency. This result is shown in figure 3. On the basis of the results, the drugs could be clearly divided into three groups. The first included drugs with a difference of+40% in terms of their preferred use for numbness as opposed to pain, and included vitamin B12 and the Kampo compound goshajinkigan. The second group included drugs with a difference of −40% in terms of their preferred use for pain as opposed to numbness and included NSAIDs and opioids. Duloxetine, other antidepressants and the antiepileptic drug pregabalin were administered almost equally for pain and numbness, and made up the final group. The same trend was obtained by subtracting the percentage of A for numbness treatment frequency from the percentage of A for pain treatment frequency for each drug.

Figure 3.

Expectation for the effect on numbness or pain in each drug. Physicians prefer different groups of drugs for treating numbness and different ones for treating pain. NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Discussion

The respondents to this questionnaire were JSMO specialists, but we cannot be certain that the results reflect the opinions of all JSMO specialists, because the rate of response to the questionnaire was only 30.9%. However, this rate of response still suggests a strong concern about CIPN among JSMO specialists. A large proportion of the JSMO respondents were aged in their 40s, and most specialised in fields associated with internal medicine, including gastrointestinal and thoracic oncology as well as haemato–oncology, and only a few specialised in fields such as gynaecological, orthopaedic or urological oncology.

The results of the questionnaire revealed that various drugs are very frequently administered for the management of CIPN in Japan. However, the effect of the drugs could not be evaluated in the present survey.

Gabapentin was reported to have no effect in a blind randomised control trial (RCT). There are no reports of RCTs for pregabalin, with the only available data coming from a case series report.6 7 Smith et al4 reported that duloxetine was effective on the basis of a blind RCT, and the ASCO guidelines reflected the results.

The main points of the ASCO guidelines are as follows: (1) Moderate recommendation for treatment with duloxetine. (2) Patients should be informed about the limited scientific evidence for CIPN, and the potential harm and cost involved in the use of tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin and pregabalin. In addition, the ASCO guidelines suggest the effect of topical gels including bacrofen, ketamine and lidokine. However, since topical gels are not widely used in Japan and need to be prepared in-house and since their safety cannot be guaranteed, they were not included in this study. Apart from the drugs included under the ASCO guidelines, other agents such as vitamin B12, opioids, NSAIDs and Kampo compounds are also administered in Japan. A search of the literature regarding these agents revealed that in spite of frequent prescription of vitamin B12, there are no reports of clinical trials on its use for CIPN in Japan. There were also no reports on the use of NSAIDs for treating CIPN.

Recently, we reported the results of an open-label, pilot randomised trial wherein duloxetine was compared with vitamin B12 in Japanese patients with CIPN.8 Significant differences in improvement in numbness and pain were observed in the duloxetine group in comparison with those in the vitamin B 12 group. Adverse events (AE) including fatigue, somnolence, insomnia and nausea were observed, but all were grade 1 in common terminology criteria for AE (CTCAE) V.4.0.9 On the basis of these results, we reported that the prescription of duloxetine to Japanese patients could be feasible.

A case series suggested that oxycodone is expected to be effective in treatment of CIPN.10 On the basis of the fact that NSAIDs and opioids are effective in treating general pain as part of palliative care, we speculated that they might also be effective in the treatment of pain associated with CIPN.

The Kampo medicine, goshajinkigan, is composed of 10 natural ingredients and is classified as a drug that affects sensory nerves. Some studies suggested that goshajinkigan improved taxane-induced neuropathy.11 Goshajinkigan was reported to be ineffective as a prophylactic agent in a blind RCT,12 although there is no conclusive evidence about its effectiveness as a preventive agent in CIPN therapy.

There is no distinction made between pain and numbness in the ASCO guidelines, but the present survey suggests that physicians in Japan prefer different groups of drugs for treating numbness and different ones for treating pain. Vitamin B12 and Kampo compounds were administered more frequently for treating numbness than for pain treatment, whereas NSAIDs and opioids were more frequently prescribed for treating pain than for numbness treatment. Antidepressant (including duloxetine) and antiepileptic agents were administered for the management of both pain and numbness. For this reason, we feel that it would be necessary to distinguish symptoms of pain and numbness in the management of CIPN in future blind RCTs to develop guidelines for CIPN treatment in Japan.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nagahiro Saijo for the editing of this article and Hiromi Nishizawa for assisting with email distribution of the survey.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cavaletti G, Frigeni B, Lanzani F et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity assessment: a critical revision of the currently available tools. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:479–94. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavaletti G, Cornblath DR, Merkies IS et al. The chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy outcome measures standardization study: from consensus to the first validity and reliability findings. Ann Oncol 2013;24:454–62. 10.1093/annonc/mds329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pachman DR, Barton DL, Watson JC et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: prevention and treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;90:377–87. 10.1038/clpt.2011.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith EM, Pang H, Cirrincione C et al. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309:1359–67. 10.1001/jama.2013.2813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH et al. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1941–67. 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao RD, Michalak JC, Sloan JA et al. Efficacy of gabapentin in the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial (N00C3). Cancer 2007;110:2110–18. 10.1002/cncr.23008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takenaka M, Iida H, Matsumoto S et al. Successful treatment by adding duloxetine to pregabalin for peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013;30:734–6. 10.1177/1049909112463416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirayama Y, Ishitani K, Sato Y et al. Effect of duloxetine in Japanese patients with chemotherapy- induced peripheral neuropathy: a pilot randomized trial. Int J Clin Oncol 2015;20:866–71. 10.1007/s10147-015-0810-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Common terminology criteria for adverse events version 4. http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Nagashima M, Ooshiro M, Moriyama A et al. Efficacy and tolerability of controlled-release oxycodone for oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy and the extension of FOLFOX therapy in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:1579–84. 10.1007/s00520-014-2132-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishioka M, Shimada M, Kurita N et al. The Kampo medicine, Goshajinkigan, prevents neuropathy in patients treated by FOLFOX regimen. Int J Clin Oncol 2011;16:322–7. 10.1007/s10147-010-0183-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oki E, Kojima H, Higashijima J et al. Preventive effect of goshajinkigan on peripheral neurotoxicity of FOLFOX therapy (GENIUS trial): a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized phase III study. Int J Clin Oncol 2015;20:767–75. 10.1007/s10147-015-0784-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]