Abstract

Background

Bevacizumab has become standard of care as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), after proving increased response rates and improvement in survival outcomes. Hypertension (HTN) is a common complication of the treatment with bevacizumab and, owing to its close relation with antiangiogenic mechanism, may represent a clinical biomarker to predict the efficacy of the treatment. The aim of this study was to retrospectively evaluate if HTN grades 2 to 3 were correlated with response to treatment with bevacizumab in first line, as well as with improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), in a series of patients with mCRC.

Methods

Retrospective evaluation of clinical records of patients with histologically proven mCRC, treated with bevacizumab as first-line treatment, between January 2008 and December 2013.

Results

79 patients were evaluated. 51.9% of patients developed HTN G2-G3 during chemotherapy-bevacizumab treatment. In the group of patients who developed bevacizumab-related HTN, 73.2% showed response to treatment (complete response (CR)+ partial response (PR)) and 97.6% achieved disease control (CR, PR or stable disease) compared to 18.4% of patients with response and 63.2% with disease control in the group that did not (OR 12.08; 95% CI 4.13 to 35.29; p<0.001 responders vs non-responders; OR 20.8; 95% CI 2.56 to 168.91; p 0.005 controlled vs non controlled disease). The median OS was 28 months (22.7–33.3). Significant statistical difference was obtained in PFS between the two groups (p<0.001). In the group that developed bevacizumab-related HTN, the median OS was 33 months (25.7–40.3), and in the group that did not, it was 21 months (16.5–25.5) with no significant statistical difference between the two groups (p 0.114).

Conclusions

In this subset of patients, HTN G2-3 was predictive of response to treatment with bevacizumab and of PFS but not of OS.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Bevacizumab, Hypertension

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Bevacizumab became standard of care as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) in association with chemotherapy, but not all patients benefit from bevacizumab treatment.

Cumulative data, gathered from retrospective studies, show that bevacizumab-induced hypertension (HTN) appears to be associated with a statistically significant improvement in response rates, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

Bevacizumab-related HTN may serve as a predictor biomarker of response/survival in patients with mCRC treated with bevacizumb in first-line setting.

What does this study add?

In our subset of patients, HTN G2-3 demonstrated to be predictive of response to treatment with bevacizumab and of PFS.

A trend towards a favourable OS was observed.

These results strengthen previous evidence that bevacizumab-related HTN may be a potential predictive biomarker for bevacizumab efficacy.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

In the context of an exponential increase in economic treatment costs, contributed by targeted therapy, the identification of a reliable, non-invasive, feasible and not costly predictive factor that would allow the selection of patients/tumours more likely to benefit from treatment and spare those who would not from additional toxicity is of great value in clinical practice.

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality rates vary markedly around the world. Globally, CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in males and the second in females.1 Approximately 25% of patients present with initial stage IV disease and almost half of the patients with CRC will develop metastases with a CRC-related 5-year survival rate approaching 60%.2

Within the past 10 years, an increase in the number of chemotherapeutic agents available to treat this disease has been seen. Novel biologically targeted therapies, which interfere with specific molecular pathways of cancer proliferation and metastasis, are being developed.3 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a key mediator of angiogenesis and plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of a wide range of human cancers, being a potential target for new anticancer therapies.

Bevacizumab, a humanised anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, became standard of care as first-line treatment of mCRC, after showing effectivity in the treatment of mCRC with improvement in response rates and survival outcomes.4–6 Although not all patients benefit from bevacizumab, selection of those who do profit from this therapy is still difficult because no biomarker has yet been identified that allows us to predict the benefit of the association of bevacizumab to chemotherapy in mCRC. Different biomarkers, such as B-raf and K-ras mutation, microvessel density, VEGF receptor (VEGFR) expression, have been widely studied, but none has proven to be a reliable predictive factor.7 8

Hypertension (HTN) is a common complication of the treatment with bevacizumab which is easily manageable with antihypertensive agents. The pathogenesis of VEGF signal inhibition-induced HTN is still unclear with reports suggesting that impaired angiogenesis or endothelial dysfunction associated with bevacizumab treatment may be responsible.5 9 In fact, VEGF signal antagonism may lead to inhibition of nitric synthase with a consequent decrease in the nitric oxide level, which in turn leads to vasoconstriction and decrease in sodium renal excretion, ultimately resulting in HTN.9

Cumulative data from recent studies have suggested that HTN may be a biomarker for efficacy of VEGF signal inhibition, namely of bevacizumab, due to the underlying mechanism of action. Retrospective studies have shown that patients who develop bevacizumab-induced HTN showed increased response rates and progression-free survival (PFS) in comparison with those who did not. These findings build up the hypothesis that bevacizumab-induced HTN may represent a predictive and prognostic biomarker in patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving first-line bevacizumab.5 10 11

The aim of this study was to retrospectively evaluate if HTN grades 2 to 3 were correlated with response to treatment with bevacizumab in first line, as well as with improved PFS and overall survival (OS), in a series of patients with mCRC.

Patients and methods

Patients and study design

Eligible patients were 18 years of age or older with histologically proven mCRC, with measurable disease, receiving bevacizumab as first-line therapy at a dose of 5 mg/kg every 2 weeks in association with irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid, according to the FOLFIRI regimen, or oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid, according to the FOLFOX regimen. Tumour response evaluation was performed with the use of CT or MRI, depending on which imaging methods were used at baseline.

Blood pressure measurements were recorded before the infusion of bevacizumab by the nurses and a daily record of the blood pressure values was carried out by the patient. The highest value of arterial blood pressure recorded was taken into account to define the grade of bevacizumab-induced arterial HTN according to the grading of the National Cancer Institute—Common Toxicity Criteria toxicity scale V.4.0. Grade 2–3 arterial HTN was the cut-off level for HTN definition in accordance with previous reports, indicating this level to be biologically and clinically relevant.3 9 Patients were then stratified into two groups, those who did not present HTN (grade 0–1) and those who presented bevacizumab-related HTN (grade 2–3). Tumour response and progression were assessed by radiologists of the home institution according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, V.1.1 every 8 weeks. Response was not re-evaluated by independent radiologists as this assessment was not performed in a clinical trial setting but in a daily clinical practice context. The best tumour response was taken into account to define responders (patients showing complete or partial response) or non-responders (progressive disease). Disease control (DC) was defined as those patients who achieved complete response, partial response and stable disease. The disease was staged at the time of diagnosis according to the guidelines of the American Joint Committee on Cancer V.7.

End points

The primary end point was objective response rate, defined as the number of patients with a complete or partial response divided by the number of patients evaluated. Secondary efficacy end points were duration of PFS, defined as the interval between the start of bevacizumab therapy to clinical progression or death from any cause or last follow-up visit if not progressed, and OS, defined as the interval between the start of bevacizumab therapy to death or last follow-up visit.

Statistical analysis

The demographic characteristics were evaluated with descriptive statistics. The association between categorical variables was estimated by Fisher's exact test. Odds ratios (OR) was used to compare the relative odds of response/disease control, given the development or not of bevacizumab-related HTN. Survival distribution was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Comparisons of PFS and OS between groups were performed using Cox Regression. Data on patients who were lost to follow-up were censored at the time of the last evaluation. A significant level of 0.05 was chosen to assess the statistical significance. To determine if HTN was an independent predictive factor for response to treatment with bevacizumab, Cox regression model was used and adjusted age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS (performance status) and KRAS status.

Results

Since January 2008 and December 2013, 79 patients' records were evaluated with a median follow-up time of 19 months. Seventeen patients were excluded because they did not present a consistent record of their blood pressure monitoring. Patients' characteristics according to the development or not of bevacizumab-related hypertension are presented in table 1 below.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics

| Patients with bevacizumab-related HTN (N=41) | Patients without bevacizumab-related HTN (N=38) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 60.2 (32.7–77.3) | 60.4 (31.6–78.8) |

| Male:female | 28 (68.3%):13 (31.7%) | 25 (65.8%):13 (34.2%) |

| Primary tumour location | ||

| Colon | 26 (63.4%) | 24 (63.2%) |

| Rectum | 15 (36.6%) | 14 (36.8%) |

| Metastases location | ||

| Liver | 27 (65.9%) | 31 (81.6%) |

| Lung | 11 (26.8%) | 8 (21.1%) |

| Liver+Lung | 6 (14.6%) | 5 (13.2%) |

| Peritoneal, lymph nodes, bone, ovary and penis | 8 (19.5%) | 5 (13.2%) |

| Primary tumour surgery | ||

| Colon | 23 (56.1%) | 14 (36.8%) |

| Rectum | 8 (19.5%) | 4 (10.5%) |

| Previous chemotherapy (CT) | ||

| Stage II | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (5.2%) |

| Stage III | 11 (26.8%) | 9 (23.7%) |

| Chemotherapy (CT) associated with bevacizumab frontline | ||

| FOLFIRI | 37 (90.2%) | 36 (94.7%) |

| FOLFOX | 4 (9.8%) | 2 (5.3%) |

| RAS status | 36 (87.8%) | 34 (89.5%) |

| KRAS (wt:mutated) | 22 (61.1%):14 (38.9%) | 19 (55.9%):15 (44.1%) |

| NRAS (wt:mutated) | 9 (25%):0 (0%) | 4 (11.8%):0 (0%) |

| Proteinuria (yes:no) | 0 (0%):41 (100%) | 0 (0%):38 (100%) |

| Previous diagnosis of HTN | 15 (36.6%) | 17 (44.7%) |

| Maintained treatment until progression (after initiating antihypertensive treatment) | 38 (100%) | N/A |

| ACE inhibitors | 34 | |

| ARB | 4 | |

| Suspended treatment with bevacizumab | 3 (7.3%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Thromboembolic event | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (100%) |

| Fistulisation | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Response rate (%) | 73.2 | 18.4 |

| Disease control (%) | 97.6 | 63.2 |

| Median OS (months) | 33 | 21 |

ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; HTN, hypertension; N/A, not applicable; OS, overall survival.

The median age at diagnosis was similar between the two groups (about 60 years) with a predominance of the male gender being observed in both arms (68.2% vs 65.8%). All patients were evaluated in terms of PS presenting an ECOG PS 0-1. The majority of patients (85.4%) in the group who developed bevacizumab-related HTN had an ECOG PS 1, while in the group who did not, almost 66% presented an ECOG PS of 0. The majority of patients had their primary tumour in the colon (about 63% in both groups). Hepatic or lung metastases were more frequently seen in both arms with a similar number of patients presenting both liver and lung metastases. Peritoneal lymph node, bone, ovarian and/or penile metastases were observed, although to a lesser extent. In the group of patients who developed bevacizumab-related HTN, more patients seem to have been previously submitted to surgery of the primary (56.1% vs 36.8% colon; 19.5% vs 10.5% rectum). A similar proportion of patients received chemotherapy for stage II and III CRC in both groups. The chemotherapy regimen most often used in association with bevacizumab in first-line treatment for mCRC was, undoubtedly, FOLFIRI with more than 90% of the patients in both arms having received this treatment. No patient developed proteinuria during treatment with bevacizumab. The majority of patients in both arms were evaluated for KRAS status, with 14 in the group that developed bevacizumab-related HTN, and 15 in the group that did not, presenting a KRAS mutation. NRAS status was evaluated in a minority of patients with all of those patients having an NRAS wild type.

About 40% of patients, in both groups, presented a previous diagnosis of HTN managed with medical treatment. All patients evaluated presented a blood pressure at baseline within normal range. Forty-one patients (51.9%) developed HTN G2-G3 during chemotherapy-bevacizumab treatment (35 patients (85.4%) grade 2 and 6 patients (14.6%) grade 3). Thirty-eight patients (92.7%), after beginning treatment with adequate antihypertensive therapy, maintained bevacizumab until progression (3 suspended: 2 developed thrombotic events and 1 fistula).

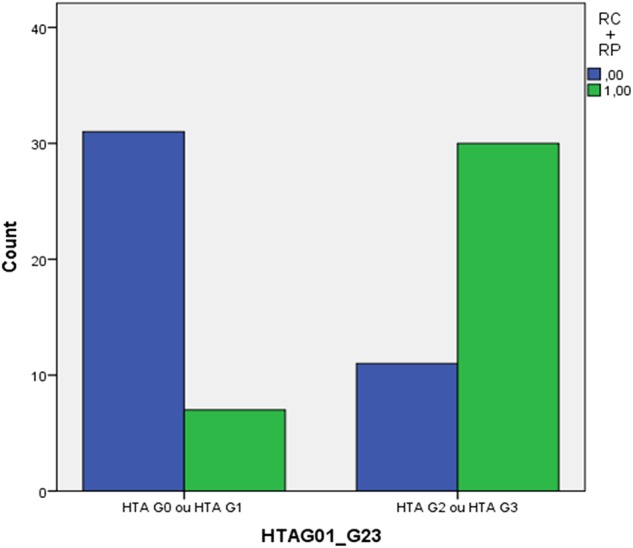

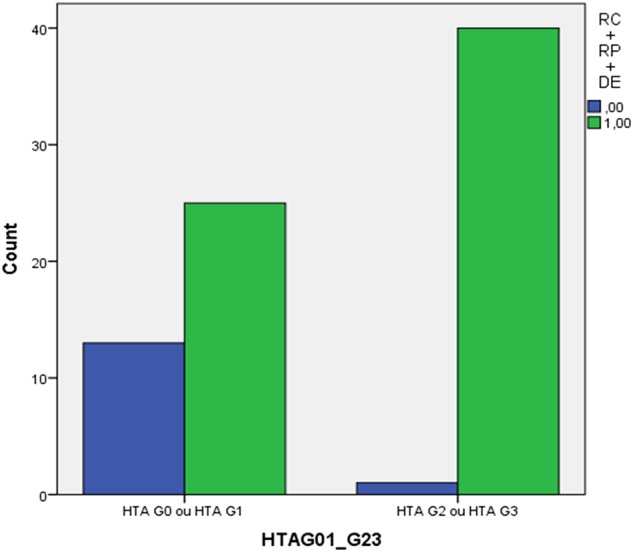

All patients were evaluated in terms of response: 5 patients (6.3%) presented complete response (CR), 32 patients (40.5%) partial response (PR) and 28 patients (35.4%) stable disease. In the group of patients who developed bevacizumab-related HTN, 30 (73.2%) presented response to treatment (complete response (CR)+partial response (PR)) and 40 of them (97.6%) achieved DC (CR, PR or stable disease) compared to 7 patients (18.4%) with response and 24 (63.2%) with DC in the group of those who did not develop HTN (OR 12.08; 95% CI 4.13 to 35.29; p<0.001 responders vs non responders; OR 20.8; 95% CI 2.56 to 168.91; p 0.005 controlled vs non-controlled disease) (figures 1 and 2). HTN G2-3 was an independent predictor of progression-free survival for all adjusted factors but not of OS (see online supplementary data).

Figure 1.

Number of patients with response in the groups of grade 2–3 bevacizumab-induced HTN and without bevacizumab-related HTN. HTN, hypertension.

Figure 2.

Number of patients with disease control in the groups of grade 2–3 bevacizumab-induced HTN and without bevacizumab-related HTN. HTN, hypertension.

esmoopen-2016-000045supp.pdf (68.8KB, pdf)

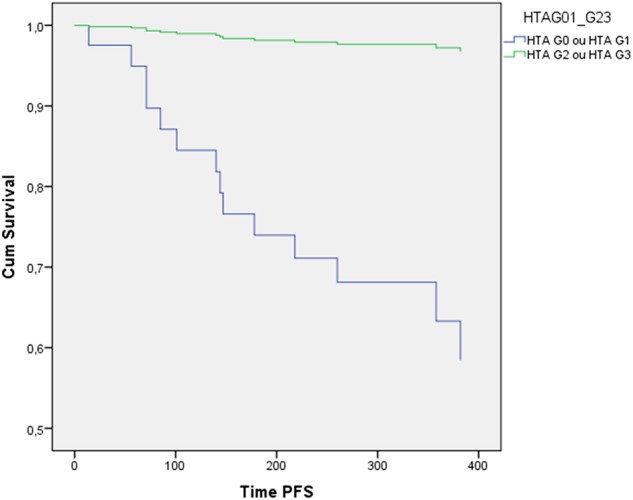

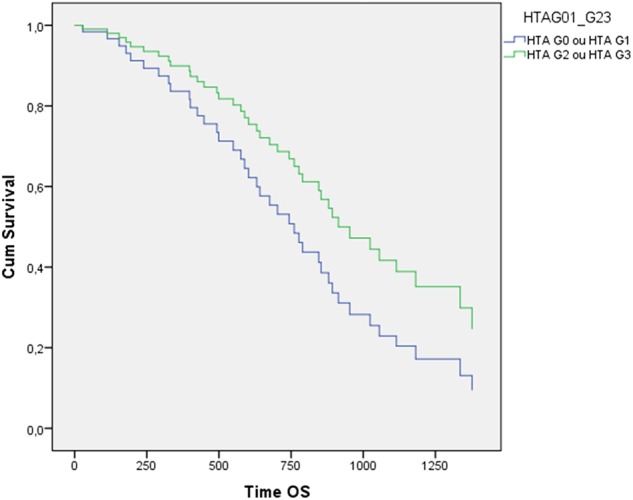

A significant statistical difference was obtained in PFS between the two groups (p<0.001) (figure 3). The median OS was 28 months (22.7–33.3). In the group that developed bevacizumab-related HTN, the median OS was 33 months (25.7–40.3) and in the group that did not, it was 21 months (16.5–25.5), with no significant statistical difference between the 2 groups (p 0.114) (figure 4).

Figure 3.

PFS of patients with colorectal cancer with grade 2–3 bevacizumab-induced HTN and without bevacizumab-related HTN (p<0.001). HTN, hypertension; PFS, progression-free survival.

Figure 4.

OS of patients with colorectal cancer with grade 2–3 bevacizumab-induced HTN and without bevacizumab-related HTN (p 0.114). HTN, hypertension; OS, overall survival.

Discussion

Target therapies like bevacizumab affect tumour growth by targeting specifically tumour-activated biological pathways. New toxicity profiles with this new agents have emerged, as the acneiform skin rash with the anti-EGFR therapy and vascular abnormalities associated with anti-VEGFR agents.12 HTN is a common adverse event of the treatment with antiangiogenic therapy (such as bevacizumab) that has been correlated with the biological inhibition of the VEGF-related pathway and may represent a possible clinical marker for treatment efficacy, analogously to what has been demonstrated for skin rash and cetuximab.3 13

Cumulative data, gathered from retrospective studies, show that bevacizumab-induced HTN appears to be associated with a statistically significant improvement in response rates, PFS and OS, raising the hypothesis that bevacizumab-related HTN may serve as a predictor biomarker of response and survival in patients with mCRC treated with bevacizumb in a first-line setting.

Scartozzi et al12 conducted a retrospective study which included 39 patients with mCRC treated with bevacizumab as part of front-line therapy. Twenty per cent of the patients developed grades 2–3 HTN with a significant improvement in response rate (73.2% vs 18.4% p<0.001) and PFS (14.5 months vs 3.1 months p<0.001) being observed in the group of patients who developed bevacizumab-related HTN with no statistically significant difference in the median OS. In the Österlund et al14 study, 56% of the patients presented HTN with results showing that HTN predicted bevacizumab treatment efficacy regardless of the analysed end point (OS, PFS or RR). Early HTN, defined as HTN within 3 months of treatment initiation, was shown to be predictive for OS in this study. Similar data in metastatic renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer and lung cancer have also been published.15–17 Dahlberg et al16 showed that HTN within 1 month in bevacizumab therapy for lung cancer was predictive for survival.

In our study, 51.9% patients developed HTN G2-G3 during chemotherapy-bevacizumab treatment, which is superior to that reported in other retrospective trials.6 12 16 According to a recently published large meta-analysis, the incidence of HTN in bevacizumab-treated patients with cancer was 23.6%.18 A possible explanation may be that our study population presents a high predominance of the male gender being more frequently affected by primary HTN, suggesting that bevacizumab-related HTN may present the same biological pathway, or that this increase may be possibly due to selection bias since it is a retrospective trial. Our results seem to be in line with published data, with patients who developed bevacizumab-related HTN showing an improvement in clinical outcomes, namely response rates (73.2% vs 18.4% p<0.001 responders vs non responders), disease control (97.6% vs 63.2% p 0.005 controlled disease vs non-controlled) and PFS (p<0.001). In our group, no statistical difference in the median OS was observed (33 months vs 21 months p 0.114), although a trend towards a favourable outcome was seen in those patients with bevacizumab-induced HTN. HTN G2-3 was an independent predictor of progression-free survival for all adjusted factors (age, ECOG PS and KRAS status) but not of OS. This apparently conflicting result might be explained by the fact that HTN is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease being associated with an increase in cardiovascular mortality and so possibly counteracting, in the long term, the potential beneficial impact on OS. The fact that more patients were submitted to surgery of the primary tumour in the group of patients who developed bevacizumab-related HTN may reflect a population with less advanced disease at diagnosis. Only a minority of the patients were evaluated for NRAS status, which is explained by the fact that this mutation analysis only became available for clinical use in our institution recently. The fact that it is a retrospective analysis, as the majority of the previous studies on this subject, presents some limitations as the lack of randomisation (presenting possible selection bias) and accuracy of data (as it is carried out in a retrospective fashion). The small sample size may also be a limitation, although this sample is larger than that of some of the previous ones reported (Scartozzi or Österlund).

It would be interesting to perform analysis about the potential effect of antihypertensive medication on treatment efficacy in bevacizumab-treated mCRC. Owing to the sample size, the authors did not have adequate statistical power to evaluate this hypothesis. It is known that inflammation might affect blood pressure; however, owing to the fact that the C reactive protein level at baseline was not systematically evaluated for all patients, since it is normally requested in an infectious setting, this effect could not be assessed.

The accumulating evidence seems to imply that the identification of a reliable clinical factor such as bevacizumab-induced grades 2–3 arterial HTN may constitute an early indicator efficacy, whereas lack of this side effect could represent a warning of lack of activity and maybe justify an early change in the treatment strategy, for example, EGFR inhibitors.9 10 In the context of an exponential increase in economic treatment costs, contributed by targeted therapy, the identification of a reliable, non-invasive, feasible and not costly predictive factor that would allow the selection of patients/tumours more likely to benefit from treatment and spare those who would not from additional toxicity is urgent.3 19

In conclusion, in this subset of patients, HTN G2-3 demonstrated to be predictive of response to treatment with bevacizumab and of PFS. Bevacizumab treatment-related HTN is a very interesting subject at the moment and prospective studies, to disclose whether bevacizumab-associated HTN predicts outcome and the exact mechanism for the development of anti-VEGF related HTN, are needed.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Helena Gervásio at @H.Gervasio

Contributors: IJDdS performed the literature search, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and writing; JF and JR participated in literature search, data collection, analysis and interpretation. NB helped in data collection and writing. PJ, MM, JR, AP and HG participated in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM et al. . Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;61:69–90. 10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B et al. , ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii1–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdu260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryanne Wu R, Lindenberg PA, Slack R et al. . Evaluation of hypertension as a marker of bevacizumab efficacy. J Gastrointest Cancer 2009;40:101–8. 10.1007/s12029-009-9104-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs CS, Marshall J, Mitchell E et al. . Randomized controlled trial of irinotecan plus infusional, bolus, or oral fluoropyrimidines in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the BICC-C study. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4779–86. 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Diaz-Rubio E et al. . Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2013–19. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W et al. . Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2335–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa032691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ince WL, Jubb AM, Holden SN et al. . Association of k-ras, b-raf, and p53 status with the treatment effect of bevacizumab. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:981–9. 10.1093/jnci/dji174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jubb AM, Oates AJ, Holden S et al. . Predicting benefit from anti-angiogenic agents in malignancy. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:626–35. 10.1038/nrc1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Sun P, Weng H et al. . Hypertension as a predictive biomarker for efficacy of bevacizumab treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J BUON 2014;19:917–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai J, Ma H, Zhu D et al. . Correlation of bevacizumab-induced hypertension and outcomes of metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol 2013;11:306 10.1186/1477-7819-11-306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maitland ML, Moshier K, Imperial J et al. . Blood pressure as a biomarker for sorafenib, an inhibitor of VEGF signalling pathway. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2035 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scartozzi M, Galizia E, Chiorrini S et al. . Arterial hypertension correlates with clinical outcome in colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line bevacizumab. Ann Oncol 2009;20:227–30. 10.1093/annonc/mdn637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S et al. . Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:337–45. 10.1056/NEJMoa033025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Österlund P, Soveri L-M, Isoniemi H et al. . Hypertension and overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab-containing chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2011;104:500–604. 10.1038/bjc.2011.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider BP, Wang M, Radovich M et al. . Association of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 genetic polymorphisms with outcome in a trial of paclitaxel compared with paclitaxel plus bevacizumab in advanced breast cancer: ECOG 2100. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4672–8. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlberg SE, Sandler AB, Brahmer JR et al. . Clinical course of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients experiencing hypertension during treatment with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel on ECOG 4599. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:949–54. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu D et al. . Hypertension (HTN) as a biomarker of efficacy in patients (pts) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) treated with sunitinib. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Genitourinary Cancer Symposium; 2010a; (Abstract 312). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranpura V, Pulipati B, Chu D et al. . Increased risk of high-grade hypertension with bevacizumab in cancer patients: a metaanalysis. Am J Hypertens 2010;23:460–8. 10.1038/ajh.2010.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capdevila J, Saura C, Macarulla T et al. . Monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2007;33(Suppl 2):S24–34. 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

esmoopen-2016-000045supp.pdf (68.8KB, pdf)