Abstract

Background

Body hair shafts from the beard, trunk, and extremities can be used to treat baldness when patients have inadequate amounts of scalp donor hair, but reports in the literature concerning use of body hair to treat baldness are confined to case reports.

Objectives

This study aimed to assess the outcome of body hair transplanted to bald areas of the scalp in selected patients.

Methods

From 2005 through 2011, 122 patients preselected for adequate body hair had donor hair transplanted from the beard, trunk, and the extremities to the scalp by follicular unit extraction (FUE) by the author at a single center. All patients were emailed surveys to assess surgical outcomes and overall satisfaction.

Results

Seventy-nine patients (64.8%) responded with a mean time of 2.9 years between date of last surgery and time of survey. Patients were generally very satisfied with results of their procedure, giving mean scores of at least a 7.8 on a Likert-like scale of 0 to 10 for their healing status, hair growth in recipient areas, and overall satisfaction with their surgeries. These scores were comparable to mean scores provided by patients whose transplants included scalp donor sources.

Conclusions

FUE using body hair can be an effective hair transplantation method for a select patient population of hirsute individuals who suffer from severe baldness or have inadequate scalp donor reserve.

Level of Evidence:

4 Therapeutic

Therapeutic

It has been estimated that there are up to 12,500 hairs, or approximately 6000 follicular units consisting of 2 to 3 hairs, that are pragmatically transplantable in the average standard donor area (SDA) of the head, an area considered not at risk for hair loss due to androgenic alopecia.1 However, individuals with severe baldness or severely depleted donor areas from previous hair restoration procedures are not good candidates for traditional hair transplantation methods with hair from the SDA. In these cases, body hair transplantation (BHT), which refers to the use of beard and body hair donor sources in the treatment of baldness, remains a viable option in hirsute patients.1-7 In contrast, body hair restoration (BHR) describes use of head or body hair in areas of loss in nonscalp areas (such as pubic or eyebrow hair restoration or eyelashes).8-14 Body hair from the beard, trunk, and the extremities can be transplanted by follicular unit extraction (FUE) methods and combined with head hair, if available, to cover both scalp and nonscalp areas to improve severe baldness,1 create more natural and softer hairlines,5 repair donor strip scars from previous hair restoration surgeries,6 and restore facial and body hair.8-13

Although the application of BHT to treat baldness is promising, reports in the literature have been confined to case reports.2-8,12,13 The objectives of the current article are to present the author's experience in a large series of patients who have undergone BHT using FUE, define suitable candidates selected for the procedure, illustrate the use of different donor and recipient areas, and provide information on patient satisfaction with the procedure and outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design

The guidelines of the Department of Health and Human Services Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects were followed. No IRB approval was sought because this was not a prospective or systematic investigation. Patients were eligible to be included in the study if they were men and had undergone BHT performed using FUE between September 2005 and October 2011. Only beard hair (both facial and anterior neck hair areas) was used for strip scar repair. Body hair was combined with, when available, hair from the head that also included the nape and periauricular areas (NPA) of the scalp. Written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to surgery, and the study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient Selection and Considerations

Potential candidates for BHT have a relative or absolute lack of traditional head donor hair to adequately address their baldness. The main reasons for the lack of traditional head donor hair for transplant are extensive baldness or donor area depletion by prior surgeries. In general, finer and shorter hairs from the leg are more appropriate for restoring or repairing the hairline and temple areas, while coarser beard hair is more appropriate for imparting density and for repair of surgical scars.5,7 The choice of body hair graft source is in part influenced by the observation that body hair generally retains its characteristics when transplanted to recipient head sites.2,6,8 For example, beard hair is much coarser and can grow longer than finer, shorter hair originating from the legs. The diameter of the follicle, color, curliness, texture, growth rate, and shaft angle must also be taken into consideration to best match transplanted hair with the recipient hair site, bearing in mind that combinations of hair from different areas of the body can provide a more blended look and that some sources of body hair, such as the beard, will lose pigment faster over a long period of time.

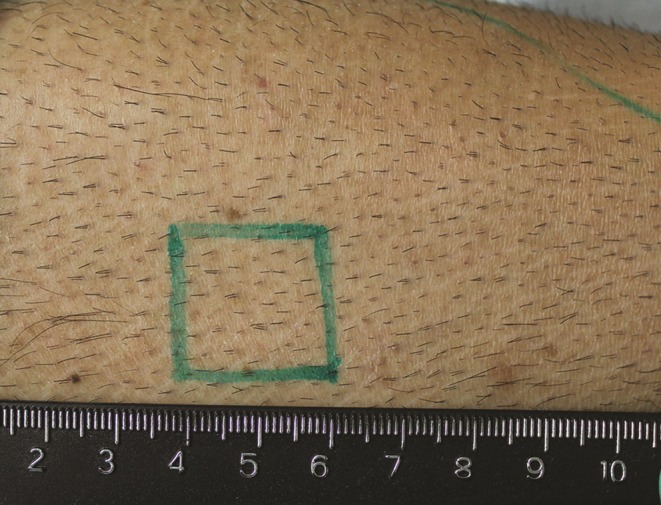

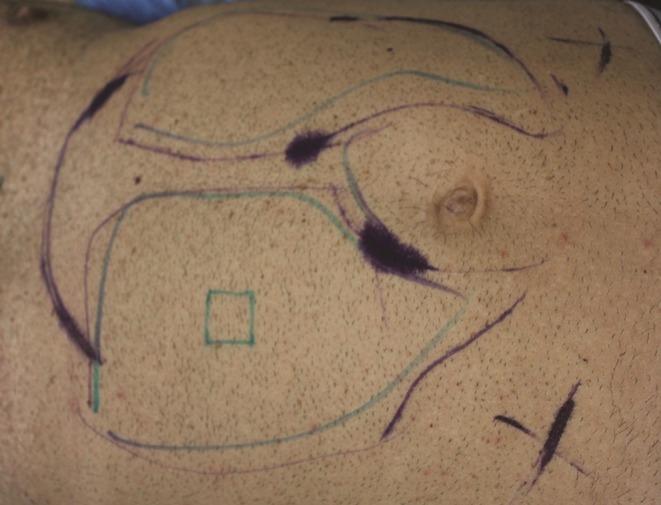

A robust supply of good quality hair in the beard or other body areas is essential. In the author's experience, terminal (nonvellous) hair and uniform average density spread of ≥8 per cm2 (Figure 1) is of good quality for transplantation. Patchy areas of hair, regardless of location on the body, are to be avoided. For example, Figure 2 shows a patient's abdomen in which the areas marked with an X have densities less than 8 per cm2 compared with the circled area, which shows a higher density and more uniform hair spread. In practice, it is common to demarcate areas from a specific body location area into viable vs nonviable sources. Figure 3 shows an example in which the legs have totally nonviable hair sources because of complete hair loss in most areas; in those areas with hair, the hair is vellous-looking and has an unsatisfactory density.

Figure 1.

Example of good quality terminal hair with satisfactory hair density demonstrated on this 40-year-old man.

Figure 2.

Viable and nonviable areas of donor hair extraction in the abdominal area demonstrated on this 40-year-old man. The uniformity and density of hair within the encircled area is satisfactory, but the lower abdominal areas indicated by the X are not.

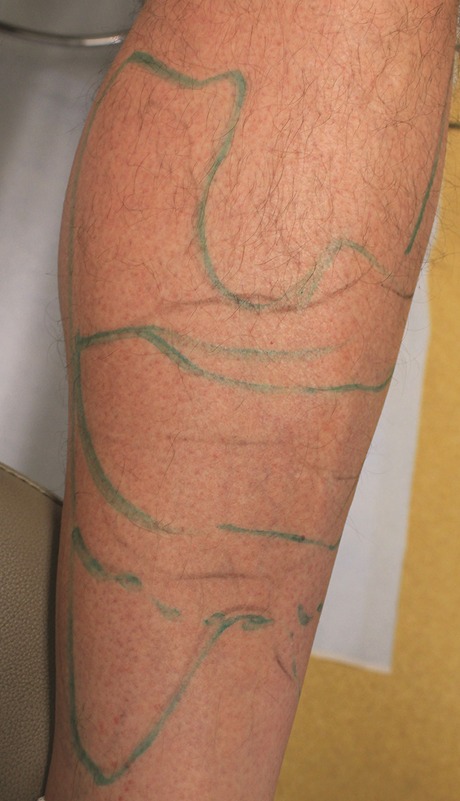

Figure 3.

This 49-year-old man is a poor candidate for leg hair extraction because of complete hair loss in most areas. In the areas with hair, the hair is also vellous-looking with densities below 8 per cm2.

Another important preoperative consideration is the targeting of anagen hair for extraction as these hairs are less susceptible to damage during the extraction process.5 Two methods were employed in these patients. The first is the treatment of the identified donor areas with 5% minoxidil once or twice daily between 6 weeks and 6 months prior to surgery.5,7 This treatment is intended to shorten the telogen phase by inducing follicles resting in the telogen phase to begin the anagen phase,15 as well as lengthen the anagen phase and increase hair caliber.16 About 7 to 10 days before surgery for nonbeard BHT (or 2-3 days for beard BHT), donor areas are shaved bare to identify late-phase anagen hair,1,5-7,12,13 based on the phototrichogram method described by Saitoh et al17 for anagen hair quantification.

Hair Transplantation Technique

Body hair transplantation was accomplished using FUE techniques previously described.7 In general, approximately 1500 to 1800 grafts can be transplanted during an 8- to 9-hour operation day, divided into 2 blocks of time: graft extraction and placement of grafts in their intended recipient areas. Consequently, planning is required in terms of scheduling once the number of grafts required has been estimated. Although back-to-back operational days can be scheduled when required, patient availability and tolerance are factors as is the target density issue for those patients at risk for scalp necrosis in which hair density in a recipient area is built up over a long period time (several sessions over 6-12 months).

A versatile orthopedic table that can accommodate lateral tilt, normal and reverse Trendelenberg positions, height adjustments, and head and neck maneuverability, at a minimum, is recommended.7 A table with leg-splitting capabilities is also useful when leg hair extractions are to be performed. Each session starts with the surgeon mapping out the extraction and recipient areas and approximately how many hair shafts will be extracted from each donor area. If scalp hair is to be extracted in the session, this is done first prior to any body hair extraction.

FUE was conducted under local anesthetic achieved by subcutaneous injections of epinephrine (1:100,000) and lidocaine 1%, and bupivacaine hydrochloride 0.25% without tumescence. Graft extraction was done by use of a hypodermic needle with a modified tip in which the circumference has been flared outward to form a punch-like instrument mounted on a rotary tool (the UPunch Rotor). The cutting tip was fabricated by the author from 19- or 18-gauge needles. This modification minimizes much of the customary graft damage that accompanies the use of straight punches, resulting in clean extraction of intact grafts as the axis of the punch cutting edges is directed away from the follicles.7,18 In addition, because wounds created by these customized punches widen with depth, injury to follicles is lessened, and wound closure accelerated. Of note is the author's use of only 18-gauge needles for the extraction of gray hairs on the premise that using smaller punches may increase the possibility of disrupting the integrity and viability of the follicles. Although the strength of gray hair is comparable to pigmented hair, it has a higher susceptibility to ultraviolet radiation damage and is under higher oxidative stress.19,20 Grafts were hydrated with a piece of wet gauze using a 2- to 3-minute interval between the time of scoring and actual removal of the follicles. This process has been subsequently automated by the author wherein grafts were hydrated by the rotary device (UGraft Revolution Pro-Dex Inc., Irvine, CA) that irrigates them with a physiologic solution at the time of scoring. The irrigation system delivered fluid to a chamber in the hand piece and is activated by the operator via a foot pedal. Hair follicles were then removed with the occasional assistance of hypodermic needle tip dissection and placed in chilled Ringer's lactate solution.

The author has observed that following scoring by the UPunch Rotor, a variable percentage of grafts is completely separated from all tissue attachments. It is possible that these grafts are susceptible to ischemia and desiccation at a faster rate than grafts with residual attachments to the surrounding tissue, which require hypodermic needle separation. Consequently, a simple procedure (“FUE swipe maneuver”) was devised to rapidly identify these follicles and to remove and store them in physiologic media separately ahead of attached grafts. The procedure entails rubbing wet gauze over the donor areas soon after 50 to 100 follicles have been scored. This maneuver typically removes most of these free grafts (Figure 4). Although the relationship between graft survival and time between scoring and actual removal of grafts has not been well studied, biochemical evidence would suggest that this time should be minimized.21 For recipient grafting, slits were created by means of blades custom-sized to the dimensions of the extracted grafts.

Figure 4.

After the “FUE swipe maneuver,” the wet gauze retains most of the grafts that have been completely separated from tissue prior to any mechanical separation by the surgeon. Some grafts are also found laying on the skin surface free of any tissue attachments.

Postoperative nonhead hair donor sites were left open and coated with bacitracin or Neosporin ointment for the first 7 days after surgery twice a day, and triamcinolone lotion 0.1% was used daily for the first 3 days after surgery.

Patient Surveys

A survey was emailed to patients from June 2011 through June 2012 to evaluate donor healing, recipient growth, and overall satisfaction with the procedure. Patients were identified on the survey sheet. Reminders were re-emailed to nonresponders at least twice. The following indices were evaluated using 11-point Likert-like scales: healing status (0 = not well at all and 10 = very well); hair growth in the restored area (0 = no growth and 10 = excellent growth); donor area wound healing (0 = not well at all and 10 = very well); hair growth in strip hair surgery scar area, as applicable (0 = zero growth and 10 = excellent growth); and overall satisfaction with the procedure and results (0 = not satisfied and 10 = extremely satisfied). Additionally, the transplanted graft count was extracted from patient records and evaluated. A blank copy of the survey is available as Supplemental Material at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com.

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty-two men were included in the study. The mean patient age of the patients undergoing BHT was 42.7 years (standard deviation [SD], 8.67; range, 24-66 years).

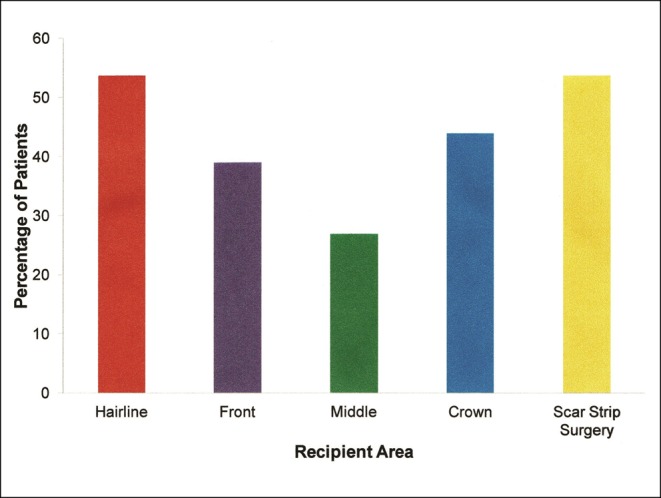

In 113 patients (92.6%), beard hair was one of the BHT donor sources used. In 78 BHT patients (63.9%), head and NPA hair were additional donor sources. Six patients (4.9%) had donor hair from only the trunk, limbs, armpits, and pubic area transplanted, in which no hair was used from the beard, head, or NPA areas. Main recipient areas included the hairline, scar strip surgery, and crown of the scalp (Figure 5). In over half of patients (n = 65, 53.3%), strip surgery scar surgery repair was the sole procedure or done in conjunction with restoration of balding scalp recipient areas whereby beard hair was transplanted into the linear scars of a previous strip hair transplantation. Four patients requested minor touch up transplants to their eyebrows in addition to their BHT and were included in the survey. In all 4 of these patients, over 6000 grafts were implanted to their scalps in contrast to less than 100 grafts total for eyebrow implants.

Figure 5.

Patient recipient areas.

The mean graft count was 4346 (Table 1). The proportion of BHT grafts as a percentage of total grafts was 75% (SD, 33.3). Eighteen patients (14.8%) underwent multiple surgery sessions—typically 2 or 3—although a few had as many as 6 or 7 sessions.

Table 1.

Transplanted Graft Statistics of the Patients by Donor Source

| Donor Source | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alla | 4346 | 3575.0 | 3437 |

| Trunk | 2515 | 1816.4 | 1654 |

| Limbs | 2095 | 2060.6 | 1231 |

| Beard | 1715 | 1513.1 | 1205 |

| Pubis | 823 | 824.0 | 371.2 |

| Armpits | 591 | 261.4 | 599 |

| Head | 1468 | 1481 | 791.2 |

| NPA | 402 | 437.0 | 136 |

aIQR (interquartile range], 5044; range, 309-17,183), n = 98.

Survey Results

Seventy-nine patients responded to the survey, a response rate of 64.8%. Individual question response rates varied, but for overall satisfaction questions, the mean response rate was 62.6%. Mean follow-up time between last surgery and administration of the survey was 2.9 years (SD, 1.17; range, 0.2-6.3 years).

Patients were generally very satisfied with the results of their procedure, giving average scores of at least a 7.8 on a Likert-like scale of 0 to 10 for their healing status, hair growth in the recipient areas, and overall satisfaction with their surgeries. Patients who assessed the healing of their donor areas (n = 74, 60.2%) gave a mean score of 8.6 (SD, 1.63) (Table 2). Patients who, in addition to their BHT donor sources, also had head and NPA hair as a donor source reported the most satisfaction with the healing status (n = 46), giving a mean score of 8.9 (SD, 1.56). For patients who had contributions from beard hair as a donor source, rating of donor area healing made little difference whether they also had a strip scar surgery or not (mean, 8.7 vs 8.6, respectively).

Table 2.

BHT Patient Assessment of Donor Area Healing, Based on a Scale of 0-10

| Patient Group | Responses |

Donor Area Healing Score |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Alla | 73 | 59.8 | 8.6 | 1.63 |

| BHT patients who had contributions from trunk, limbs, armpits, and pubic hair as donor sourceb | 20 | 57.1 | 8.1 | 1.55 |

| BHT patients who had contributions from beard hair as a donor sourcec | 67 | 59.3 | 8.7 | 1.60 |

| BHT patients who had contributions from head and NPA hair as a donor sourced | 46 | 60.0 | 8.9 | 1.56 |

| BHT patients absent use of head or NPA donor sourcese | 30 | 63.8 | 8.1 | 1.82 |

| 29 | 63.0 | 8.0 | 1.82 | |

Group denominators: an = 122, bn = 35, cn = 113, dn = 78, en= 46.

Seventy-nine patients (64%) assessed the transplanted hair growth in the recipient areas, providing a mean score of 8.2 (SD, 1.71) (Table 3). Of the 65 patients in whom beard hair was used to improve the appearance of their strip scar from previous hair restoration procedures, 48 (73.8%) responded to the question of overall hair growth rate. The mean growth score provided was 8.2 (SD, 1.64). Almost all strip scar patients had beard hair used as their sole donor source (n = 60), which is characteristic of my practice. These patients provided a slightly higher mean score of 8.3 (SD, 1.64) for just their strip scar growth outcomes. Patients who had the beard as a donor source but did not have a strip scar surgery rated their overall hair growth rate as 8.3 (SD, 1.65).

Table 3.

Patient Assessment of Growth of Transplanted Hair, Based on a Scale of 0-10

| Patient Group | Responses |

Growth Assessment Score |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Alla | 79 | 64.8 | 8.2 | 1.71 |

| Strip scar repair patientsb | 48 | 73.8 | 8.2 | 1.64 |

| BHT patients who had contributions from trunk, limbs, armpits, and pubic hair as donor sourcec | 22 | 61.1 | 7.8 | 1.94 |

| BHT patients who had contributions from beard hair as a donor sourced | 71 | 62.8 | 8.3 | 1.63 |

| BHT patients absent use of head or NPA donor sourcese | 28 | 65.1 | 7.9 | 1.76 |

Group denominators: an = 122, bn = 65, cn = 35, dn = 113, en = 43.

Overall satisfaction with the surgical outcomes reported by the patients (n = 77, 63.1%) was high with a mean score of 8.3 (SD, 1.71) (Table 4). Patients whose donor sources involved only 1 or more of trunk, limbs, armpits, pubic areas, or beard areas for nonstrip scar head recipient sites were well satisfied with the results, providing mean scores of 8.2 and 8.3, respectively. This compared favorably with patients who, in addition to their BHT transplants, also included the use of head or NPA grafts, who reported a mean score of 8.3 (Table 4). For the 6 BHT patients in whom only trunk, limb, armpits, or pubic donor sources were utilized (ie, no head or beard donor sources were used), the mean scores for donor healing, overall growth rate, and overall satisfaction were 7.1, 6.9, and 8.0, respectively.

Table 4.

Patients' Overall Satisfaction with the Results of Their Body Hair Transplantation Surgery, Based on a Score of 0-10

| Patient Group | Responses |

Overall Satisfaction Score |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Alla | 77 | 63.1 | 8.3 | 1.71 |

| Strip scar repair patientsb | 45 | 69.2 | 8.1 | 1.77 |

| BHT patients who had contributions from trunk, limbs, armpits, and pubic hair as donor sourcec | 22 | 62.9 | 8.2 | 1.76 |

| BHT patients who had contributions from beard hair as a donor sourced | 70 | 61.9 | 8.3 | 1.75 |

| BHT patients who had contributions from head and nape hair as a donor sourcee | 48 | 61.5 | 8.3 | 1.87 |

| BHT patients absent use of head or NPA donor sourcesf | 28 | 65.1 | 8.3 | 1.45 |

Group denominators: an = 122, bn = 65, cn = 35, dn = 113, en = 78, fn = 43.

Patient Outcomes

No complications were encountered in any patients.

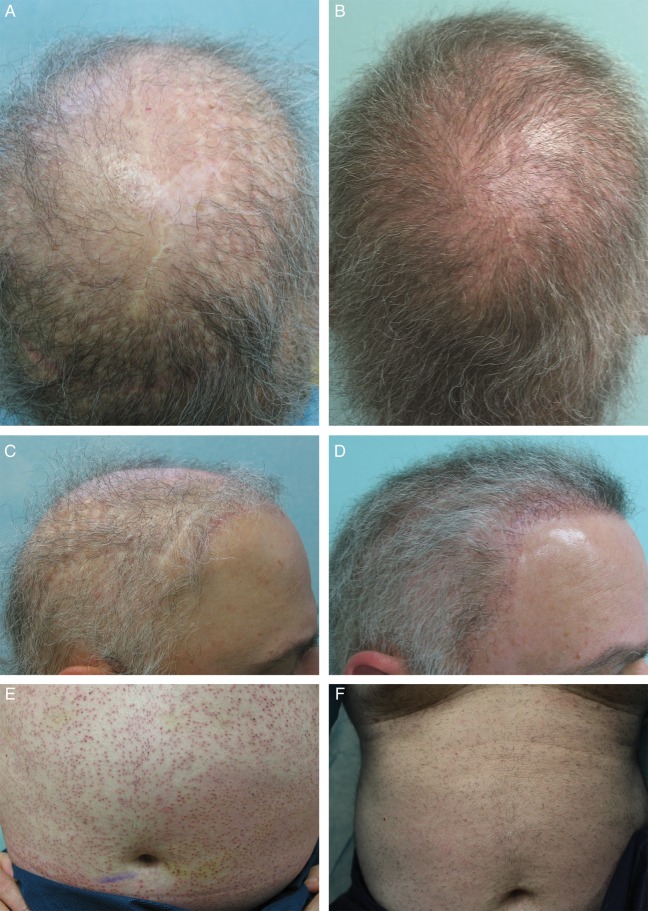

Figure 6 depicts a 46-year-old patient who had experienced multiple failed attempts at hair restoration with head donor areas used exclusively. In particular, the crown area was mostly bald with pluggy and misplaced rows of hair. After transplantation of 14,000 grafts from the head and beard, the result is a cosmetically excellent restoration over the entire Norwood (NW) level 6 area,7 with a softer repaired hairline in which chest hair was mainly used as the donor source.

Figure 6.

(A, C) Preoperative and (B, D) 12-month postoperative photographs of a 46-year-old man. The preoperative bird's eye view (A) shows multiple failed attempts at hair restoration with head donor surgeries and the preoperative crown view (C) shows a mostly bald area with surrounding pluggy, misplaced rows of hair. The postoperative photographs demonstrate a hairline (B) repaired with mainly chest hair to fullness and a softer look and a completely restored crown view (D) after transfer of 14,000 grafts from head and beard.

Figure 7 presents preoperative photographs of another representative patient who was severely bald with no option to using head donor that had been exhausted from previous hair surgeries. In addition to thinning that involved an NW 7 area, several scars in the NW 7 area and hairline needed to be covered. After using 8000 grafts from the chest, abdomen, thighs, and legs, as well as 2000 grafts from the beard areas, the results show a nicely restored Norwood level 6 area as well as the camouflaging of the scars and the creation of a more natural hairline that is appropriate for a middle-aged man.1

Figure 7.

(A, C) Preoperative and (B, D) 6-month postoperative photographs of this 58-year-old man. This patient is an example of severe baldness compounded by exhaustion of head hair donor sites due to previous hair transplantation surgeries. Linear scars of scalp reduction (in crown) and 4 mm punch scars are visible in the occipital and parietal regions (A). In addition to severe thinning, there are linear scars from past temporoparieto-occipital flap surgery in the hairline and temples as well as 4 mm punch excision scars in the parietal regions (C). The postoperative photographs show much improved coverage for the crown of the head and camouflaging of prior surgical scars and aesthetically pleasing hairline and temple coverage (B), as well as the obfuscation of the linear scars in the hairline and temples (D). The patient's abdominal area a few days after body hair extractions (E) and the abdominal region showing healed BHT extraction area about 3 months postoperatively (F). On very close examination, insignificant white dots are visible.

DISCUSSION

In preselected hirsute patients, BHT to the head can be a viable technique to produce cosmetically acceptable results when adequate scalp donor hair is not available. In my practice, about 45% of patients receive BHT, although this figure might be much lower in other practices. However, it is important to understand that, for the majority of patients, BHT is used along with more traditional donor sources such as the SDA or NPA. Despite the methodological limitations (self-selection) of a retrospective survey, patients who responded had good assessments of healing, hair growth, and overall satisfaction with their surgeries. The highest scores were given by patients who, in addition to BHT grafts, also utilized head and NPA hair as a donor source. However, when comparing the results among patient subgroups, patients with BHT without contributions from head or NPA donor sources also had good overall satisfaction (range, 8.1-8.2). In fact, BHT patients with beard-involved donor hair provided the same mean score as BHT patients with head and NPA-involved donor hair for both growth rate assessment and overall satisfaction with the results. For healing status, the mean score was nearly as high for beard-involved donor BHT patients (8.7) as head and NPA-involved donor BHT patients (8.9). Incidentally, the overall satisfaction score with BHT in this study regardless of donor source (8.3) was the same as the overall satisfaction score achieved when only finer head hairs from the NPA areas were used to create softer hairlines and temples (8.3).18

The 6 BHT patients in whom no head or beard donor sources were used (ie, only hairs from any 1 or more of trunk, limbs, armpits, and pubic hair were used as donor sources) generally provided marginally lower scores (7.1 for donor healing and 6.9 for growth rate) However, in terms of overall satisfaction with the results, these patients were nearly as equally satisfied (mean score, 8.0) as their counterparts in whom their BHT also involved the utilization of beard, head, or NPA counterparts (mean score, 8.3).

The major limitations to the use of BHT in hair restoration (compared with traditional use of scalp hair as a sole donor source) are that the procedure is longer and more costly, requires a higher surgical skill level and specialized equipment and instruments, may result in lower quality outcomes, and is not an option in nonhairy individuals.7 In particular, it is worth noting that while the overall graft take using SDA/NPA is about 95%, for BHT it is around 75%-80%.1,5 It is also relatively labor intensive and, given the complexity and delicate nature of the procedure, the applicability of robotic options seems less likely in the near future.

From clinical experience, the author has observed a large number of patients with patchy areas of baldness both on the body (Figure 3) and in the beard. Although the most common cause of such patchy hair loss in the beard area is alopecia areata, other conditions are also often responsible.22,23 In one instance, a biopsy by the author of patchy leg area of hair loss revealed a single hair follicle in catagen-telogen phase with no significant peribulbar inflammatory cell infiltrate; no follicular ostia in the epidermis; no interface dermatitis, dermal mucinosis, or scarring; and no melanin pleating. There was scant superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with rare melanophages. These were nonspecific findings and may be related to chronic friction in the area. In cases in which the cause of patch hair loss is unclear, it is advisable to refrain from extracting hair from these and adjacent areas. Earlier in his experience with BHT, the author noted a relatively higher graft transection and trauma rate during extractions of hairs from the back regions of the torso. This is attributed to the fact that the reticular dermal layer in the region is the thickest of all body regions24; for this reason, back hairs should be routinely avoided in BHT. The beard is the easiest skin area from which to extract with other areas slightly more difficult. When extracting from the abdomen, lack of patient sedation is important so the patient can coordinate breathing movements with the surgeon's activities. The trunk areas involved in the reported patients only involved the chest, abdominal, and upper shoulders, and transection rates were acceptable at 10% or less. In the beard area, it is typically less than 5%, and it is 5%-10% in the area below the neck. The UPunch Rotor also pulls the follicle into its lumen as it cuts around it, and the operator does need not push the punch all the way to the follicular root as the punch pulls the follicle upward in effect carrying the cut down to the follicular root level and beyond it (3-6 mm). This pulling action is attributed to the textured inner surface of the device, which the author considers a critical component to the success of the technique in his hands.

Healing of donor areas can leave white dots, which are hypopigmented, tiny but flat, and insignificant scars that are hardly visible in Caucasian patients but may be more visible in patients with darker skin. The author has not observed any instance of hypertrophic scarring or keloids in part because patients with history of abnormal scarring are disqualified from having surgery and also because of good surgical practice, technique, and tooling, such as use of the UPunch Rotor, which enhances wound closure and aesthetics. However, the most common side effects of FUE in general still apply, including the occasional ingrown hair.

Because transplanted body hair (with the exception of beard hair) does not grow as long as head hair, hair is routinely maintained short after the procedure for the best cosmetic results. Another factor favoring a shorter haircut stems from the observation that in predominantly beard graft-involved BHT, a longer hair cut could present grooming challenges as beard hair is relatively wirier and may be difficult to style. In addition to maintaining hair short to optimize cosmetic results of BHT by FUE, hair dyes can be used to produce a more even coloring at the recipient site.2 In general, men naturally tend to be better candidates than women for BHT to the head because they typically possess beard and body hair. Finally, patient expectations must be managed accordingly, with the realization that their recipient area hair will be short, but still cosmetically acceptable, when body hairs have been transplanted.

While patient satisfaction of BHT was good in the present patients, and about two-thirds of patients answered questions, retrospective surveys have inherent limitations. Not all patients returned their surveys, which can result in response bias, as well as over- or underestimation of means and variance estimates. Second, when patients are asked to rate items that happened in the past (eg, donor healing areas), responses can be inaccurate. In addition, questionnaires were not returned anonymously, which can also be a source of bias. Despite these limitations, most patients returned their survey and reported good results. Third, a blinded, third-party assessment of patients' results based on preoperative and postoperative photos was not possible, which limits confirmation of patient assessment. Last, complete graft information was not available for every patient, which could lead to more uncertainty regarding the statistics. Strengths of the study include a relatively large sample size and breadth of combinations of donor sources.

CONCLUSIONS

This series of patients suggests that transplantation of body hair to the scalp by FUE can be a cosmetically viable treatment in a select patient population of hirsute individuals who suffer from severe baldness or have inadequate hair in their SDA.

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material located online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com.

Disclosures

The author has a US patent for the UGraft and UPunch technologies (Pro-Dex, Inc., Irvine, CA) described in this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Umar S. Hair transplantation in patients with inadequate head donor supply using nonhead hair: Report of 3 cases. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;67:322-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandy D. Chest hair used as donor material in hair restoration surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:841-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods R, Campbell AW. Chest hair micrografts display extended growth in scalp tissue: a case report. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(8):789-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones R. Body hair transplantation to wider donor scar. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umar S. The transplanted hairline: leg room for improvement. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:239-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umar S. Use of beard hair as a donor source to camouflage the linear scars of follicular unit hair transplant. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1279-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umar S. Use of body hair and beard hair in hair restoration. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2013;21:469-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirai T, Inoue N, Nagamoto K. Potential use of beards for single-follicle micrografts: convenient follicle-harvesting technique using an injection needle. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:37-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee YR. Hair Transplanting in the pubic area. In: Unger W, Shapiro R, eds. Hair Transplantation. 4th ed New York: Informa Healthcare; 2011:450-452. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein J. Eyebrow transplantation. In: Unger W, Shapiro R, eds. Hair Transplantation. 4th ed New York: Informa Healthcare; 2011:460-463. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein J. Facial hair restoration: Hair transplantation to eyebrows, beard, sideburns, and eyelashes. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2013;21:457-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umar S. Eyelash transplantation using leg hair by follicular unit extraction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:e324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umar S. Eyebrow transplantation: alternative body sites as a donor source. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:e140-e141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umar S. Eyebrow transplants: the use of nape and periauricular hair in 6 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1416-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinclair R, Patel M, Dawson TL Jr et al. . Hair loss in women: medical and cosmetic approaches to increase scalp hair fullness. Br J Dermatol. 2001;165(Suppl 3):12-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saitoh M, Uzuka M, Sakamoto M. Human hair cycle. J Invest Dermatol. 1970;54:65-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umar S. Use of nape and peri-auricular hair by follicular unit extraction to create soft hairlines and temples: my experience with 128 patients. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;358:903-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao T, Bedell A. Ultraviolet damage on natural gray hair and its photoprotection. J Cosmet Sci. 2001;52:103-118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trüeb RM. Oxidative stress in ageing of hair. Int J Trichology. 2009;1:6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsley WM, Perez-Meza D. Review of factors affecting the growth and survival of follicular grafts. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3:69-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khodaee M. Bald patch in the beard. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:583-584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacLean KJ, Tidman MJ. Alopecia areata: more than skin deep. Practitioner. 2013;257:29-32, 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velazquez EF, Murphy GF. Histology of the skin. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL et al., eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:7-66. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.