Abstract

Female life expectancy is currently shorter in the United States than in most high-income countries. This study examines work-family context as a potential explanation. While work-family context changed similarly across high-income countries during the past half century, the United States has not implemented institutional supports, such as universally available childcare and family leave, to help Americans contend with these changes. We compare the United States to Finland—a country with similar trends in work-family life but generous institutional supports—and test two hypotheses to explain US women's longevity disadvantage: (1) US women may be less likely than Finnish women to combine employment with childrearing; and (2) US women's longevity may benefit less than Finnish women's longevity from combining employment with childrearing. We used data from women aged 30–60 years during 1988–2006 in the US National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File and harmonized it with data from Finnish national registers. We found stronger support for hypothesis 1, especially among low-educated women. Contrary to hypothesis 2, combining employment and childrearing was not less beneficial for US women's longevity. In a simulation exercise, more than 75 percent of US women's longevity disadvantage was eliminated by raising their employment levels to Finnish levels and reducing mortality rates of non-married/non-employed US women to Finnish rates.

Female life expectancy is currently shorter in the United States than in most high-income countries. This growing longevity disadvantage is well documented but poorly understood. One potential explanation is that US women's longevity disadvantage partly reflects the dramatic changes in work-family context (especially the rise in single-parent households and dual-earner households) in the post-WWII era, alongside weak US policies to assist working parents. While work-family context changed similarly across other high-income countries during this time frame, many of those countries implemented institutional supports, such as universally available childcare and family leave, to help working parents contend with these changes. Some US women have responded to the obstacles in combining employment with childrearing by exiting the labor force. Other US women have continued to combine employment with childrearing but may experience high levels of role strain as a result. Both of these scenarios have implications for women's longevity. For instance, exiting the labor force can reduce access to income and other health-enhancing resources, and experiencing chronic work-family strain can deteriorate health.

In this study, we compare the United States to Finland—a country with similar trends in work-family context but generous institutional supports—and test two hypotheses to explain US women's longevity disadvantage: (1) US women may be less likely than Finnish women to combine employment with childrearing; and (2) US women's longevity may benefit less than Finnish women's longevity from combining employment with childrearing. We test these two hypotheses for all women and separately by education level. It is important to examine the hypotheses by education level because the longevity disadvantage of US women is most pronounced among the low educated and because institutional supports may be especially salient for this group. The findings provide insights into how broader social-policy contexts have intersected with the changing landscape of work and family life to shape women's longevity.

Background

Gains in women's life expectancy within the United States have not kept pace with many high-income European countries during the past few decades (Crimmins, Preston, and Cohen 2011). For example, between 1980 and 2005, life expectancy at age 30 among US women increased 2.0 years (from 49.2 to 51.2), compared with a 4.1-year increase in Finland (from 48.9 to 53.0) (Human Mortality Database n.d.).

The resulting longevity disadvantage of US women may partly reflect the fact that the smoking epidemic among women started earlier and reached a higher peak in the United States than in most high-income countries (Crimmins, Preston, and Cohen 2011). However, US women have higher mortality across numerous causes of death and among ages where smoking plays a minor role. For instance, over 40 percent of the life-expectancy shortfall of US women compared with other high-income countries in 2006–2008 was due to deaths occurring below age 50 (Ho 2013). Country-level differences in age-specific death rates similarly reveal large disparities among working-age women. In 2000–2004, death rates among women aged 30–49 years were 34 to 51 percent higher in the United States than in Finland, depending on the age group (Human Mortality Database n.d.) These patterns have raised the question of whether other factors, such as social-policy contexts, may also be important in understanding why US women have higher mortality than women in other high-income countries (Avendano and Kawachi 2011; National Research Council 2011).

One potential explanation for the higher mortality of US women is that it partly reflects the dramatic changes in work-family life in the post-WWII era within the context of weak US policies (e.g., family leave) to assist working parents. During this period, US women's labor-force participation rates increased, as did age at first marriage, divorce rates, and the number of single-mother households, while total fertility rates changed little (Blau 1998; Cherlin 2010; Raley and Bumpass 2003; Spain and Bianchi 1996; Zeng et al. 2012). These trends occurred within a US policy environment with few institutional supports for working parents, particularly in comparison to high-income European countries (Gornick, Meyers, and Ross 1997). For example, the United States ranks 20th out of 21 high-income countries in the number of weeks available for protected parental job leave, and it is one of few OECD countries that do not offer paid parental leave (Ray, Gornick, and Schmitt 2009).

Understanding how changes in work-family life may have affected women's mortality is challenging. On the one hand, marital, employment, and parenthood roles are usually associated with better health; and adults occupying multiple roles tend to have better health than adults with fewer roles (Barnett and Hyde 2001; Crosby 1991; Gove 1972; Martikainen 1995; Moen, Dempster-McClain, and Williams 1992; Repetti, Matthews, and Waldron 1989; Thoits 1986; Verbrugge 1983; Waldron, Weiss, and Hughes 1998). Multiple roles may provide varied and numerous sources of social support, a sense of purpose and accomplishment, and financial well-being; and through these mechanisms, the roles may enhance health. It is important to note that the health benefits of work-family roles persist even after accounting for selection of healthier individuals into the roles (Frech and Damaske 2012; Murray 2000; Pavalko and Smith 1999).

On the other hand, combining work and family roles may be less salubrious when their demands are high and supports are low (Barnett and Hyde 2001; Voydanoff 2004). Supports such as partners, spouses, and work-family policies largely determine the feasibility of combining work and family roles and whether individuals derive the expected benefits from them (Barnett and Hyde 2001; Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie 2007). Combining employment and childrearing may be particularly challenging in the United States. Compared with European countries, employer expectations of work hours are generally higher for US employees; yet institutional support structures, such as childcare and family leave, are less generous and comprehensive (Heymann 2000; Moen and Roehling 2005; Padavic and Reskin 2002).

Indirect support for the possibility that post-WWII changes in work-family life without commensurate changes in institutional supports have contributed to US women's longevity disadvantage comes from evidence that work-family conflict has increased in the United States (Nomaguchi 2009; Winslow 2005). Further supporting this possibility, the increase in work-family conflict appears to be largest for unmarried, working mothers: In 1977, 10 percent of them reported that their job interfered with family life, as opposed to 21 percent in 1997 (Winslow 2005). Moreover, work-family conflict may be more common among US women than women in other high-income countries. Among women in seven high-income countries, the percentage of employed women who desired more time with their families ranged from 90 percent in the United States to 52 percent in the Netherlands (Gornick and Meyers 2005).

Some US women have responded to the obstacles in combining work and family by reducing work hours or exiting the labor force (Gornick and Meyers 2005; Kaufman and Uhlenberg 2000). This trade-off has myriad consequences, such as lower incomes for women and their families. Other women continue to combine these roles, but may experience high levels of role strain. Despite increases in labor-force participation, women remain more likely than men to be the primary caregivers for children and aging parents. They are also more likely than men to be employed in low-wage and inflexible jobs. The resulting role strains can damage health. For instance, sustained work-family conflict appears to increase cardiovascular disease risk (Berkman et al. 2010), depressive symptoms (Ertel, Koenen, and Berkman 2008; Frone 2000), sickness absence (Jansen et al. 2006; Väänänen et al. 2008), and deteriorate overall health (Frone, Russel, and Cooper 1997; Väänänen et al. 2004). In sum, these studies imply that the obstacles to combining employment and childrearing in the United States—whether they deter labor-market participation or elevate role strain—could contribute to US women's longevity disadvantage. To our knowledge, no prior study has examined the extent to which differences between the United States and other high-income countries in the prevalence of, and longevity benefits of, combining employment and childrearing have contributed to the disadvantage.

Educational Attainment

When assessing the potential contribution of work-family context to US women's longevity disadvantage, there are several reasons to consider heterogeneity by educational attainment. First, while Americans from all education levels experience higher mortality rates than similarly educated Europeans, the mortality gap is largest among the low educated (Avendano et al. 2009; Avendano et al. 2010). This suggests that there may be something particularly toxic about the US environment for low-educated women, which should be investigated and remedied.

Second, heterogeneity in work-family context by education level is substantial within the United States and many other middle- and high-income countries. Low-educated women are less likely to be married, to be employed, and to combine employment with childrearing than their more educated peers (England, Garcia-Beaulieu, and Ross 2004; England, Gornick, and Shafer 2012; Kalmijn 2013). Moreover, since the mid-1970s, education has become an even stronger predictor of US women's work and family roles (Cohen and Bianchi 1999; Montez et al. 2014).

Third, work-family context may have differential consequences by education level. While the challenges of combining employment and childrearing cut across education levels (Williams and Boushey 2010), low-educated US women may be particularly vulnerable. When employed, they are more likely than their higher-educated peers to have minimum wage, precarious jobs with limited flexibility in time allocation (Kalleberg 2011). Thus, they may be more likely to encounter conflicting demands between work and family. In countries with generous institutional supports for working parents, low-educated women may disproportionately benefit from policies such as comprehensive parental leave and childcare—supports often unavailable to their US counterparts. In sum, country-level disparities in work-family context and its health and longevity consequences may be greatest for low-educated women.

It is important to note that the mortality disadvantage of low-educated US women compared with peers in other countries is unlikely to be fully explained by work-family contexts and policies. Other factors, such as access to healthcare, redistributive social policies, and health behaviors, may also contribute (Avendano and Kawachi 2014). For instance, while healthcare coverage is near universal in Western and Northern Europe, 17 percent of Americans under age 65 are uninsured and a large share of them are low educated (Adams, Kirzinger, and Martinez 2012). Compared with European countries, the United States offers less generous social provisions and redistributive policies (OECD 2008), which are particularly beneficial for low-educated individuals. However, prior studies indicate that these factors provide only a partial explanation for the mortality gap (Avendano et al. 2010; Crimmins, Preston, and Cohen 2011). The current study contributes to our understanding of the reasons behind US women's mortality disadvantage by examining an immensely important and changing feature of women's lives—their work and family context.

United States versus Finland

Finland provides an interesting comparison. Both Finland and the United States experienced similar trends in employment and fertility rates in recent decades. Full-time employment among women has also increased rapidly in Finland since the 1960s and has been slightly higher than in the United States. In 1960, 66 percent of women aged 15–64 in Finland were in the labor force, as opposed to 42 percent in the United States. By 1980, these estimates rose to 70 percent in Finland and 59 percent in the United States (OECD 2010). At the same time, total fertility rates declined to a similar level: 1.8 in the United States and 1.6 in Finland in 1980 (World Bank 2013).

Despite these similarities, women's employment levels in these two countries differ in some respects. After WWII, Finland experienced a workforce shortage and thus Finnish women made a fairly rapid and direct entry into full-time employment between 1950 and 1970 (Haataja, Kauhanen, and Nätti 2011). Partly as a result, Finnish women are less likely to work part-time than women in the United States or other Nordic countries (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014; Haataja, Kauhanen, and Nätti 2011). Except during the recession in the early 1990s, full-time employment among Finnish women has remained high. For instance, among women aged 25–54 in 2011, Finland had an 80 percent employment rate and a 77 percent maternal employment rate among women with children under 15, which is higher than in the United States (69 and 62 percent) and somewhat lower than other Nordic countries, such as Sweden (82 and 80 percent) and Denmark (83 and 84 percent) (OECD 2014).

While recent trends in work and family roles are comparable in the United States and Finland, the countries differ dramatically in their policy response. The Finnish model for reconciling work and family stands out from any other OECD country because of its tradition of support for employed parents with young children (Gornick and Meyers 2005; Jacobs and Gerson 2004). As early as 1948, Finland began constructing its family-support system by introducing a universal child benefit, and in 1973 it launched the Act on Children's Day Care, which ensured access to care for all children under school age (Finland Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2000). In the 1990s, it extended support for parental leave that encouraged father involvement, offered free preschool education for six-year-olds, and guaranteed a right to childcare. Finnish mothers receive 18 weeks of maternity leave, have access to 26 additional weeks of parental leave (which the parents can share), and receive an earnings-related allowance throughout the leave duration (Finland Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2000; Gornick and Meyers 2005). In contrast, US federal policy requires no paid parental leave, and only a small percentage (roughly 7 percent) of US firms offer some form of family-related paid leave. Following the leave period, Finnish parents have several options for guaranteed childcare; for example, providing own care at home and receiving an allowance until the child is age three, or using a municipal or private daycare until the child begins school (Finland Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2000). Childcare enrollment rates for children under age three are slightly lower in Finland than in the United States, while 73 percent of Finnish children aged 3–5 attend childcare or preschool services, compared with 67 percent of US children (OECD 2014).

Aims and Hypotheses

In this study, we examine the extent to which the higher mortality of US women compared with Finnish women may be explained by differences in work-family context. We test two hypotheses derived from the discussion above to explain the mortality gap. In developing the hypotheses, we made two assumptions. First, we expected that employment, marriage, and motherhood each predict lower mortality in both countries, and that combinations of two or more roles predict lower mortality than one role. Second, we considered employment and childrearing as the primary roles structuring the daily demands of women's lives, with marriage acting as a potential source of instrumental, economic, and social support for those roles. The hypotheses are below.

US women are less likely than Finnish women to combine employment with childrearing, especially if unmarried. A significant difference between countries in the prevalence of employment among mothers—particularly among unmarried mothers—would support this hypothesis. Moreover, we expect that support for this hypothesis will be strongest for low-educated women. We refer to this hypothesis as “structural obstacles,” as it may reflect greater obstacles to combining employment and childrearing within the United States.

US women garner fewer longevity benefits than do Finnish women from combining employment with childrearing, especially if unmarried. A significant difference between countries in the longevity benefits of combining these two roles—particularly among unmarried mothers—would support this hypothesis. In addition, we expect that support for this hypothesis will be strongest for low-educated women. We refer to this hypothesis as “work-family strain,” as it may reflect elevated role strain experienced by US working mothers due to weaker work-family reconciliation policies in the United States.

We test the hypotheses for the entire sample, as well as separately by education level. We expected US-Finland differences in the prevalence of, and mortality risks of, combining work and family roles to be largest among low-educated women. Finally, we decompose the mortality rates of each country to simulate how much of US women's mortality disadvantage reflects differences in the prevalence of, versus the mortality consequences of, work-family roles.

Data & Methods

Data Sources

The Finnish data are based on individual-level registers collated by Statistics Finland. Using personal identification numbers, they combined longitudinal, annually updated population registries and labor-market information with data on mortality and cause of death. The study data include a representative 11 percent sample of the Finnish population during 1987–2007 with an 80 percent oversample of the population that died during the period. Appropriate weights are used in our analyses to account for this oversampling. Linkage of death and population records was possible for over 99.5 percent of the population. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents—age, education, labor-force status, and family characteristics—come from population register data.

The US data are taken from the public-use National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File (NHIS-LMF). It links respondents in the 1986–2004 annual cross-sectional NHIS surveys of the non-institutionalized population with death records in the National Death Index through December 31, 2006. The linkage is based mainly on a probabilistic matching algorithm, which correctly classifies the vital status of 98.5 percent of eligible survey records (NCHS 2009). We used the data provided by the Minnesota Population Center (2012) and the NHIS raw files.

Analytic Sample

Our study period covers 1988–2006, which are the years common to the US and Finnish data. We include women aged 30–60 years. This range helps ensure that most women had completed their education and reflects the ages at which women were likely to be employed or raising children or both. We exclude women born outside each country to minimize the influence of immigration. Country of birth was not available in the NHIS-LMF in 1988, so we used Hispanic ethnicity as a proxy for a non-US birth for that survey year.

The US analytic sample includes NHIS survey data collected during 1988–2004 with mortality follow-up through December 31, 2006. To create our sample, we first selected respondents aged 25–55 years at survey. We then created a person-year file by following them for five years to monitor vital status. We set the follow-up to five years to limit the window of potential change in work-family roles. Next, we screened the person-year file to include only observations when respondents were aged 30–60 years. Thus, a respondent aged 28 years at the time of survey who survived the five-year follow-up contributes three person-year observations when she is 30, 31, and 32 years of age. Respondents are censored after death.

The Finnish sample includes data collected during 1988–2005 with mortality follow-up through December 31, 2006. Consistent with the US data structure, we created a person-year file and allow women below the age of 30 years at baseline to enter the analytic sample at the month of their 30th birthday. To ensure comparability with the US data (where information on work-family characteristics is collected from women once at the time of survey and women are then followed for five years), information on work-family characteristics was updated for each woman every five years. Also to ensure compatibility with the US data, we excluded the institutionalized population. Respondents are censored after death or at the end of the year they emigrate from Finland (emigration data not available in the NHIS-LMF).

Work, Family, and Work-Family Combinations

We harmonized the measurement of work and family roles across the two surveys. Work is categorized as currently employed (full-time or part-time) or not employed (unemployed or not in the labor force) to maximize comparability between the surveys. We group women who were unemployed with women outside the labor force because these women were not juggling employment and childrearing at the time of survey, and it is the combination of these roles that is the focus of our study (see also Schnittker 2007; Waldron, Weiss, and Hughes 1998).1 The number of children under 18 years of age residing in the family household is categorized as 0, 1, or 2 and higher. Legal marital status is defined as married, previously married (divorced, separated, widowed), or never married. When examining work-family combinations, we dichotomize the three roles into employed versus not employed, no children in the household versus one or more, and married versus unmarried, and then combine the three roles into eight work-family combinations.

Educational Attainment

We define three levels of education that are comparable between the United States and Finland. The levels reflect nationally meaningful educational thresholds (Elo, Martikainen, and Smith 2006) and have been used in international comparisons of women's employment (Pettit and Hook 2005). In the United States, the three levels are defined as low (0–11 years), mid (12 years), and high (13+ years). In our sample, the distribution of women across the three categories is 9.9, 36.9, and 53.2 percent, respectively. We do not distinguish women with a bachelor's degree or higher because the number of deaths in this group was very small for certain work-family combinations. In Finland, the three levels are defined as low (0–9 years), mid (10–12 years), and high (13+ years). The years of education are approximate and reflect the typical length of time to earn a credential. The distribution of women across the three categories is 29.5, 38.9, and 31.6 percent, respectively. Because of the large differences in educational distributions, we carried out sensitivity analyses, the results of which will be outlined in the “sensitivity analyses” section of the discussion.

Mortality

For each country, the person-year file contains an observation for each year respondents were followed. Each observation contains the length of exposure to the risk of death and vital status.

Methods

We first estimate the prevalence and death rates of each work and family role and work-family combination by country among our analytic sample. The estimates are age-standardized to the European Standard Population and based on the person-year files.

Next, for the multivariate analyses, we estimate all-cause mortality risk for each country separately using Poisson regression models for person-year data (Loomis, Richardson, and Elliott 2005). The models estimate the natural logarithm of the death rate as a linear function of the work-family predictors and covariates. The models are based on the person-year files where each person-year record contains information on the respondent's work-family roles, covariates, and a binary indicator of vital status. All models control for the covariates age, education, and race (US only; classified as white, black, or other). The model is illustrated below, where λi is the mortality rate for individual i, β1 is a vector of parameter estimates for the work-family roles, and β2 is a vector of parameter estimates for the covariates:

All models were weighted according to the study design of each country's data set. We then replicate these models by educational group. An advantage of Poisson models for survival analyses is that taking the anti-logarithm of the parameter estimates provides relative mortality ratios, where mortality in each group is compared to the mortality in the omitted reference group.

Finally, we estimate the contribution of country-level differences in work-family context to country-level differences in women's mortality by simulating what the mortality risk of US women would have been had they experienced Finnish women's (a) distribution of work-family combinations; and (b) mortality risks associated with each work-family combination.

Results

Prevalence of Work-Family Roles

Table 1 summarizes the age-standardized prevalence of work and family roles among women aged 30–60 years in 1988–2006. The country-level distributions are fairly similar. Compared with Finnish women, US women had a somewhat lower prevalence of employment (79.1 percent in Finland versus 73.9 percent in the United States), a similar prevalence of children at home (51.7 percent in Finland versus 51.9 percent in the United States), and a higher prevalence of marriage (64.8 percent in Finland versus 69.8 percent in the United States). Country-level differences are more apparent within education levels. Among low-educated women, 73.0 percent were employed in Finland versus 50.1 percent in the United States, a 23-percentage-point gap. The percentage-point gap in employment was 5.4 percent among the mid-educated (77.7 percent in Finland versus 72.3 percent in the United States) and 7.2 percent among the high educated (87.0 percent in Finland versus 79.8 percent in the United States). Also noteworthy, the higher prevalence of marriage among US women overall reflects a higher prevalence only among mid- and high-educated US women. Among low-educated women, 63.8 percent were married in Finland versus 60.7 percent in the United States.

Table 1.

Age-Standardized Prevalence of, and Death Rates Associated with, Employment, Motherhood, and Marriage among US and Finnish Women Aged 30–60 Years, 1988–2006

| Finland |

United States |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education level |

Education level |

|||||||

| All | Low | Mid | High | All | Low | Mid | High | |

| Prevalence (%) | ||||||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 79.1 | 73.0 | 77.7 | 87.0 | 73.9 | 50.1 | 72.3 | 79.8 |

| Not employed | 20.9 | 27.0 | 22.3 | 13.0 | 26.1 | 49.9 | 27.7 | 20.2 |

| Children under 18 at home | ||||||||

| 0 | 48.3 | 49.4 | 47.0 | 46.4 | 48.1 | 43.0 | 47.3 | 49.6 |

| 1 | 21.9 | 22.6 | 22.3 | 22.0 | 21.2 | 21.4 | 21.8 | 20.6 |

| 2 or more | 29.7 | 28.0 | 30.7 | 31.7 | 30.7 | 35.6 | 30.9 | 29.8 |

| Marriage | ||||||||

| Married | 64.8 | 63.8 | 63.9 | 66.4 | 69.8 | 60.7 | 71.5 | 70.2 |

| Previously married | 15.2 | 18.0 | 16.0 | 11.9 | 19.1 | 25.7 | 19.3 | 17.9 |

| Never married | 20.0 | 18.2 | 20.1 | 21.7 | 11.1 | 13.6 | 9.2 | 11.9 |

| Death rate (per 100,000) | ||||||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 128 | 158 | 121 | 105 | 170 | 309 | 180 | 143 |

| Not employed | 435 | 541 | 383 | 346 | 501 | 723 | 509 | 371 |

| Children under 18 at home | ||||||||

| 0 | 241 | 354 | 222 | 158 | 287 | 588 | 311 | 216 |

| 1 | 156 | 199 | 150 | 117 | 265 | 553 | 255 | 178 |

| 2 or more | 127 | 170 | 116 | 108 | 242 | 490 | 253 | 144 |

| Marriage | ||||||||

| Married | 151 | 192 | 140 | 115 | 202 | 372 | 220 | 152 |

| Previously married | 268 | 356 | 243 | 160 | 393 | 749 | 399 | 275 |

| Never married | 286 | 439 | 250 | 182 | 407 | 791 | 430 | 292 |

| Deaths | 26,333 | 12,616 | 8,773 | 4,944 | 3,521 | 837 | 1,436 | 1,248 |

| Death rate (per 100,000) | 190 | 257 | 175 | 132 | 259 | 516 | 272 | 189 |

| Number of women | 195,242 | 75,272 | 73,184 | 56,835 | 265,902 | 29,709 | 101,018 | 135,175 |

| Number of person-years | 2,411,049 | 798,400 | 907,007 | 705,642 | 1,528,629 | 172,140 | 583,897 | 772,593 |

Note: Prevalence estimates and death rates are age-standardized to the European Standard Population, weighted to reflect the sample designs, and based on the person-year file. The number of deaths, women, and person-years are not weighted. Totals may not add to 100.0 due to rounding.

Unmarried includes divorced, separated, widowed, and never married.

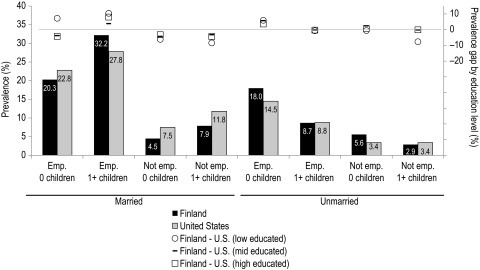

The distributions of the eight work-family combinations are displayed in figure 1, where the bars represent the prevalence of each combination. At first glance, the distributions are fairly similar. For example, 27.8 percent of US women were married and employed with children at home, compared with 32.2 percent of Finnish women; a 4.4-percentage-point gap. However, distributions by education level reveal larger country-level differences. The percentage-point gaps in work-family combinations by education level are illustrated by the symbols in figure 1 (the raw percentages are available in table A2 online). For instance, 28.1 percent of low-educated Finnish women were married and employed with children at home, compared with just 17.7 percent of low-educated US women, a 10.4-percentage-point gap. Even among the high educated, Finnish women were more likely to combine employment, marriage, and childrearing (37.9 percent) than US women (29.9 percent).

Figure 1.

Age-standardized prevalence of work-family combinations among Finnish and US women aged 30–60 years, 1988–2006

Note: Prevalence gap = prevalence of a work-family combination in Finland minus the prevalence in the United States within a given education level. Symbols above the horizontal line indicate that the prevalence was higher in Finland. All between-country differences in prevalence of work-family combinations are significant at p < 0.05 (due partly to large sample sizes).

Mortality Risks Associated with Work-Family Roles

The lower portion of table 1 contains age-standardized death rates (ASDR; deaths per 100,000 women) associated with each work and family role. The ASDR was 259 among US women and 190 among Finnish women. The 36.3 percent higher mortality of US women concurs with other data (Human Mortality Database n.d.). The ASDR was 43, 55, and 101 percent higher in the United States than in Finland for high-, mid-, and low-educated women, respectively. As expected, employment, marriage, and motherhood were each associated with lower mortality in both countries. For example, compared with non-employed women, the ASDR of employed women was 71 percent lower in Finland (435 versus 128) and 66 percent lower in the United States (501 versus 170).

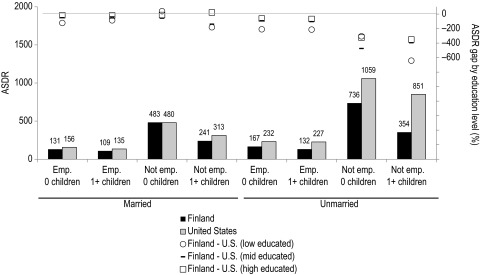

The ASDRs for the eight work-family combinations are displayed in figure 2. Two patterns are noteworthy. First, the mortality disadvantage of US women is very large for women who are non-married/non-employed, regardless of children or education level. Second, US women who combine all three roles have mortality rates comparable to their Finnish peers. The ASDR among women who combined the roles was 135 in the United States and 109 in Finland.

Figure 2.

Age-standardized death rates associated with work-family combinations among Finnish and US women aged 30–60 years, 1988–2006

Note: ASDR gap = age standardized death rate (ASDR) of a work-family combination in Finland minus the ASDR in the United States within a given education level. Symbols above the horizontal line indicate that the ASDR was higher in Finland. Among unmarried women, between-country differences in ASDR are significant at p < 0.05 regardless of education level. Among married women, between-country differences in ASDR are significant at p < 0.05 except for (a) women who were not employed and had no children at home, regardless of education level; (b) low-educated women who were employed and had children at home; and (c) high-educated women.

We further tested our expectation that each work and family role is associated with lower mortality in both countries. Table 2 summarizes the results of three Poisson regression models that estimate mortality risk separately from employment, marital status, and children at home, while controlling for age, education, and race (US only). The results support our expectation. For example, compared with non-employed women, the risk of death among employed women was 69 percent lower in Finland (p < 0.001) and 62 percent lower (p < 0.001) in the United States.

Table 2.

Relative Risks of Death Associated with Employment, Motherhood, and Marriage among Women Aged 30–60 Years, 1988–2006

| Finland |

United States |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.08 (1.08,1.08)*** | 1.06 (1.06,1.07)*** | 1.09 (1.08,1.09)*** | 1.09 (1.08,1.09)*** | 1.08 (1.07,1.09)*** | 1.09 (1.09,1.10)*** |

| Race (White) | ||||||

| Black | – | – | – | 1.89 (1.74,2.06)*** | 1.97 (1.81,2.14)*** | 1.59 (1.46,1.74)*** |

| Other | – | – | – | 1.25 (1.01,1.53)* | 1.32 (1.07, 1.62)** | 1.22 (1.00,1.50)* |

| Education (mid-level) | ||||||

| Low level | 1.32 (1.28,1.36)*** | 1.38 (1.33,1.42)*** | 1.43 (1.38,1.47)*** | 1.37 (1.23,1.52)*** | 1.74 (1.57,1.93)*** | 1.64 (1.48,1.82)*** |

| High level | 0.84 (0.81,0.88)*** | 0.74 (0.71,0.77)*** | 0.73 (0.71,0.76)*** | 0.77 (0.71,0.84)*** | 0.70 (0.64,0.76)*** | 0.69 (0.63,0.75)*** |

| Employed | 0.31 (0.30,0.32)*** | 0.38 (0.35,0.41)*** | ||||

| Children at home (0) | ||||||

| 1 | 0.68 (0.65,0.70)*** | 0.81 (0.74,0.89)*** | ||||

| 2† | 0.49 (0.47,0.52)*** | 0.69 (0.62,0,76)*** | ||||

| Marital status (never) | ||||||

| Previously married | 0.87 (0.83,0.90)*** | 0.97 (0.87,1.09) | ||||

| Currently married | 0.51 (0.50,0.53)*** | 0.55 (0.50,0.62)*** | ||||

| Deaths | 26,333 | 26,333 | 26,333 | 3,521 | 3,521 | 3,521 |

Note: Reference groups in parentheses.

*** p < 0.001 ** p < 0.01 * p < 0.05 †p < 0.10

Hypothesis 1: Structural Obstacles to Combining Employment with Childrearing

Are US women less likely than Finnish women to combine employment with childrearing? We find modest support for this hypothesis. Figure 1 shows that 40.9 percent (32.2 + 8.7) of Finnish women and 36.6 percent (27.8 + 8.8) of US women were employed mothers, a 4.3-percentage-point gap.

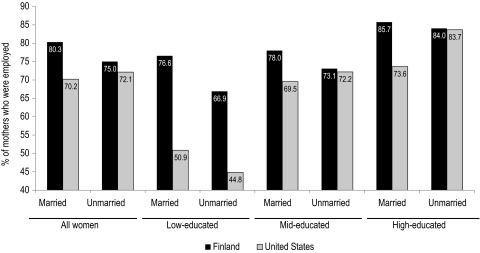

A stronger test of hypothesis 1 compares employment levels among mothers. Figure 3 shows that, among married mothers, 80.3 percent were employed in Finland versus 70.2 percent in the United States, a gap of 10.1 percent. Finnish married mothers were more likely to be employed than US married mothers within every education level (t-tests p < 0.001). The gap was striking among low-educated married mothers: 76.6 percent were employed in Finland versus 50.9 percent in the United States. In contrast, employment differed little among unmarried mothers. Among unmarried mothers, 75.0 percent were employed in Finland versus 72.1 percent in the United States; a 2.9-point gap. The similar employment levels of US and Finnish unmarried mothers existed for all but the low educated, among whom US women were less likely to be employed (p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

The percentage of women aged 30–60 years with children at home who were employed, by marital status and education level, 1988–2006

The results provide modest support for the structural obstacles hypothesis. Low-educated mothers in the United States were less likely to be employed than low-educated mothers in Finland regardless of marital status. Mid- and high-educated mothers were less likely to be employed in the United States than in Finland if they were married. One interpretation is that, among women with at least mid-levels of education, structural obstacles to combining employment with childrearing did not deter US women from employment any more than they did for Finnish women, when women did not have alternative sources of material well-being (e.g., a spouse). When alternative sources were available, US mothers were less likely than Finnish mothers to be employed.

Hypothesis 2: Work-Family Strain When Combining Employment with Childrearing

Table 3 contains relative risks (RR) of death estimated from Poisson regression models that include employment, marriage, motherhood, an “employment × motherhood” interaction, and the covariates age, education, and race (US only). The work-family strain hypothesis is supported if combining employment and childrearing had smaller mortality benefits for US women—especially unmarried women—than for Finnish women. Statistically, this means that the “employment × motherhood” interaction for US women should be larger than 1.0 and greater than the interaction for Finnish women.

Table 3.

Relative Risks of Death Associated with Combining Employment with Childrearing among Women Aged 30–60 Years, 1988–2006

| Finland |

United States |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Married | Unmarried | All | Married | Unmarried | |

| Age | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

| (1.07,1.07)*** | (1.08,1.08)*** | (1.06,1.07)*** | (1.07,1.09)*** | (1.07,1.09)*** | (1.07,1.08)*** | |

| Race (White) | ||||||

| Black | – | – | – | 1.58 (1.45,1.73)*** | 1.96 (1.72,2.22)*** | 1.35 (1.20,1.51)*** |

| Other | – | – | – | 1.21 (0.99,1.48)† | 1.17 (0.89,1.54) | 1.20 (0.89,1.61) |

| Education (mid-level) | ||||||

| Low level | 1.28 (1.24,1.32)*** | 1.25 (1.20,1.30)*** | 1.32 (1.25,1.38)*** | 1.29 (1.16,1.44)*** | 1.35 (1.17,1.55)*** | 1.21 (1.05,1.40)** |

| High level | 0.85 (0.82,0.89)*** | 0.90 (0.85,0.94)*** | 0.80 (0.75,0.85)*** | 0.77 (0.71,0.84)*** | 0.75 (0.67,0.84)*** | 0.80 (0.70,0.92)** |

| Employed | 0.28 (0.27,0.29)*** | 0.34 (0.32,0.35)*** | 0.25 (0.24,0.26)*** | 0.33 (0.30,0.36)*** | 0.40 (0.35,0.46)*** | 0.26 (0.22,0.29)*** |

| 1+ child at home | 0.51 (0.48,0.54)*** | 0.63 (0.58,0.67)*** | 0.45 (0.42,0.49)*** | 0.67 (0.60,0.75)*** | 0.67 (0.56,0.79)*** | 0.72 (0.61,0.84)*** |

| Married | 0.67 (0.65,0.69)*** | – | – | 0.55 (0.51,0.59)*** | – | – |

| Employed × 1+ child at home | 1.66 (1.57,1.76)*** | 1.44 (1.34,1.56)*** | 1.67 (1.51,1.84)*** | 1.27 (1.10,1.47)*** | 1.22 (1.00,1.50)* | 1.26 (1.01,1.57)* |

| Deaths | 26,333 | 13,977 | 12,356 | 3,521 | 1,891 | 1,630 |

Note: Reference groups in parentheses.

*** p < 0.001 ** p < 0.01 * p < 0.05 † p < 0.10

Table 3 shows that the “employment × motherhood” interaction is significantly larger than 1.0 in both countries. In other words, while employment and motherhood are each associated with lower mortality, combining these roles reduces the mortality benefits of each role. This may signal health repercussions of work-family role strain. This pattern applies to both countries, with no evidence that combining employment and childrearing elevates mortality comparatively more for US women. On the contrary, the excess mortality associated with combining these roles is somewhat larger for Finnish women (RR = 1.66; 95 percent confidence interval 1.57, 1.76) than for US women (RR = 1.27; 95 percent confidence interval 1.10, 1.47). Separate models by marital status reveal similar patterns. It is worth pointing out that, although combining employment and motherhood reduced the mortality benefits of each role, women who combined these two roles still had lower mortality than women who engaged in just one of the roles.

Models stratified by education (table A3 online) reveal that combining employment and motherhood is associated with excess mortality risk among all education levels in Finland and among mid- and high education levels in the United States. In contrast, combining employment and motherhood did not confer excess mortality risk for low-educated US women (RR = 0.85; 95 percent confidence interval 0.59, 1.23). This may indicate a ceiling effect. In other words, because the mortality of low-educated US women was high in absolute terms even when not combining the roles, it may be unreasonable to expect multiplicative effects of combining roles on mortality.

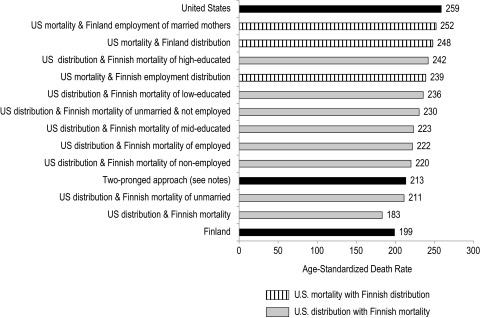

What If U.S. Women Had the Work-Family Distribution or Mortality of Finnish Women?

To estimate the potential contribution of work-family context in explaining US women's mortality disadvantage, we replaced the distribution (or death rates) of the eight work-family combinations among US women with the distribution (or death rates) among Finnish women within education levels. The procedure starts by estimating each country's mortality rate from the distribution of women and deaths for each education-work-family combination. Using this procedure, mortality rates before simulation were 199 for Finland and 259 for the United States (the ASDRs can differ from table 1 due to rounding). Based on the simulation estimates, if US women had the work-family distribution of Finnish women, the ASDR for US women would fall by only 4 percent to 248, ceteris paribus. The reduction was small because distributional changes that lowered US mortality (e.g., increases in employment) were partly offset by changes that raised US mortality (e.g., increases in the non-married/non-employed group). If US women maintained their work-family distribution but experienced Finnish women's mortality rates, their ASDR would fall by 29 percent to 183, ceteris paribus. This scenario would eliminate the US-Finland mortality gap, yielding lower mortality risk for American than Finnish women.

Additional scenarios are displayed in figure 4. We focus here on a few key scenarios most amenable to policy intervention. Increasing employment levels of married US mothers to levels of married Finnish mothers slightly reduced the US ASDR from 259 to 252. Increasing employment levels of all US women to Finnish levels reduced the US ASDR to 239 and thus shrank the mortality gap between US and Finnish women by 33 percent [(259 – 239)/(259 – 199)]. Reducing the mortality rate of US women who were non-married/non-employed to the rate of their Finnish peers lowered the US ASDR to 230, thereby shrinking the mortality gap by 50 percent. Combining these latter two approaches reduces mortality gap substantially, by more than 75 percent.

Figure 4.

Simulation of age-standardized death rates for US women if they experienced the same work-family distribution or mortality rates of Finnish women, 1988–2006

Note: The two-pronged approach entails elevating employment rates of US women to match employment rates of Finnish women and lowering mortality rates of US women who were both unmarried and not employed to match the mortality rates of Finnish women.

Sensitivity Analyses

We assessed the sensitivity of our results to several different specifications of the sample, the variables, and the models. The results were substantively unchanged across all of these various specifications, providing additional assurance in the robustness of the results.

First, we tested the sensitivity of the results to restricting the US sample to non-Hispanic white women (see online supplement). We did this to reduce race-ethnic heterogeneity in the sample and because these women have relatively low mortality. The conclusions were essentially unchanged. The ASDR decreased somewhat, from 259 for all women to 227 among non-Hispanic white women. Like the main analysis, between-country differences in the prevalence of work-family combinations existed mainly among married women, with the largest differences among the low educated. Also like the main analysis, between-country differences in death rates of the work-family combinations were largest among women who were non-married/non-employed. Again, the death rates were most similar among women who combined all three roles—marriage, employment, and children at home (ASDR = 109 in Finland and 120 in the United States). In summary, factors related to race/ethnic heterogeneity in the US sample do not drive our results.

We also tested the robustness of our results to alternative definitions of marriage. In our study, about 65 percent of Finnish women and 70 percent of US women aged 30–60 years were legally married. An additional 12 percent of Finnish women and 5 percent of US women were cohabiting.2 If the mortality patterns of cohabiting women differ significantly from other unmarried women, excluding information on cohabitation may bias our results. However, results from ancillary analyses and previous Finnish studies (Koskinen et al. 2007) on a comparable age group show that mortality among cohabiting women is similar to other unmarried women. Our robustness checks further show that the “employment × motherhood” interaction term that is of substantive interest for our analyses does not significantly differ between cohabiting and other unmarried women. Thus, the specification of marriage that we used does not appear to bias our conclusions.

We also examined an ordinal measure of children at home (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or more), but it did not alter our conclusions. For example, table 3 showed that having at least one child at home suppressed the mortality benefits of combining employment and childrearing by 27 percent (p < 0.05) among US women, with similar results for married and unmarried women. Using the ordinal measure, we found that each additional child suppressed the mortality benefits of employment by 12 percent (p < 0.01), again with similar results for married and unmarried women.

To assess the extent to which the presence of very young children might affect the conclusions, we replicated tables 2 and 3, controlling for whether the respondent had at least one child under age seven. The US results were unchanged. Among Finnish women, the employment-by-motherhood interactions were attenuated by a small degree (5–6 percent), which does not alter our conclusions. Nonetheless, one might cautiously speculate that the small attenuation reflects the benefits of childcare supports in Finland, which are most generous before age seven.

Finally, we examined whether the especially large differences between low-educated US and Finnish women might reflect differences in the education distribution of the two countries.3 Specifically, because the proportion of low-educated women was smaller in the United States (9.9 percent) than in Finland (29.5 percent), it is conceivable that low-educated women in the United States were more negatively selected than their peers in Finland. If so, this might explain the large differences in work-family context and mortality risk between these groups. To address this concern, we randomly reassigned some US women with 12 years of education down to the low-educated group (i.e., the original 0–11-year group), and some US women with 13–15 years of education down to the mid-educated group (i.e., the original 12-year group), so that the US education distribution matched the Finnish distribution. We then replicated the study (see online supplement). While the unfavorable results for low-educated US women were attenuated, these women remained disproportionately disadvantaged compared with their Finnish peers. For instance, US women remained less likely than Finnish women to be employed across education levels, and the gap remained most pronounced among the low educated. Also, US women's mortality remained higher than Finnish women's across education levels, and the gap was still most pronounced among the low educated. Similar to the main analysis, we found stronger support for the structural obstacles hypothesis than the work-family strain hypothesis. Consistent with these findings, other analyses comparing education-mortality gradients between the United States and Finland have found that the gradients were not driven by compositional differences (Elo, Martikainen, and Smith 2006).

Discussion

Gains in US women's longevity have lagged behind many high-income European countries in recent decades. We hypothesized that the resulting longevity gap partly reflects changes in work-family life in the post-WWII era alongside weak US policies to assist working parents. Some US women have responded to the obstacles in combining work and family by exiting the labor force. Other women have continued to combine these roles but may experience high levels of strain. Both scenarios have implications for women's longevity. We assessed the extent to which these scenarios may have contributed to US women's longevity disadvantage compared with Finnish women by testing two hypotheses: (1) US women may be less likely than Finnish women to combine employment with childrearing; and (2) US women's longevity may benefit less than Finnish women's longevity from combining employment with childrearing.

We found stronger support for hypothesis 1, which we refer to as the “structural obstacles” hypothesis. Among women with mid-levels of education or higher, married mothers in the United States were less likely than married mothers in Finland to be employed, while unmarried mothers were similarly likely to be employed in both countries. This finding concurs with a study of women's employment in 19 countries reporting that marriage was negatively associated with employment in the United States but positively associated in Finland (Pettit and Hook 2005). One interpretation of our finding is that structural obstacles to combining employment and childrearing did not deter US women from the labor force any more than they did for Finnish women, when women did not have alternative sources of material well-being (e.g., a spouse). When alternative sources of material well-being were available, US women were less likely than Finnish women to combine employment with childrearing. Supporting this interpretation, other studies have found a negative relationship between US women's annual hours of paid work and other family income (which for married women is primarily through a spouse). However, the negative relationship has weakened over time (Cohen and Bianchi 1999) and may not apply to nonwhite women (England, Garcia-Beaulieu, and Ross 2004). The structure of the US health insurance system may also play a role. Unmarried US women may need to maintain a strong attachment to the labor force in order to have health insurance for themselves and their children (Legerski 2012). Indeed, one of the major reasons given for full-time maternal employment in the United States is access to paid healthcare benefits (Lyonette, Kaufman, and Crompton 2012). In contrast, healthcare coverage is universal in Finland and not dependent on employment. On the other hand, the fact that unmarried mothers were similarly likely to be employed in both the United States and Finland suggests that health insurance coverage may not be the only incentive driving employment decisions among unmarried women. We also found that, among low-educated women, US mothers were less likely than Finnish mothers to work regardless of marital status. This pattern further supports the structural obstacles hypothesis.

We found little support for hypothesis 2, which we refer to as the “work-family strain” hypothesis. Contrary to the hypothesis, the longevity benefits of combining employment and childrearing were not suppressed among US women any more than they were for Finnish women. We encourage additional studies of this hypothesis to assess the extent to which our finding is robust across age groups, health outcomes, and other factors. For instance, the effects of work-family strain on women's mortality may not fully manifest until women reach older ages. The effects may also differ by other factors, such as health outcome. A recent study found that the negative effect of combining employment and childrearing on US women's self-rated health was highly significant, although it largely evaporated once children entered school (Schnittker 2007). Another complicating factor is selection. If combining employment and childrearing in the United States is as difficult as studies suggest, US women who combine these roles may be positively selected on characteristics that lower mortality (e.g., sense of control, resiliency) and buffer any health repercussions of combining the roles. In other words, the US sample of employed mothers may be a very select group of women, while the Finnish sample may be more heterogeneous. Finally, it is possible that the longevity benefits of combining employment with childrearing may be suppressed most severely among US women working very long hours—a group too small to impact population-level analyses. For instance, Schnittker (2007) found that combining work and motherhood suppressed the health benefits of employment mostly among the small group of women working more than 50 hours per week.

Implications

Even though we found the strongest support for the structural obstacles hypothesis in contributing to the longevity disadvantage of US women, our simulation exercise indicates that removing obstacles to employment among mothers alone would not erase the disadvantage. Instead, our findings suggest that the disadvantage could be greatly reduced through a two-pronged approach. One approach is to make it easier for US adults to integrate multiple work and family roles. The second approach is to provide adequate social and economic supports for US adults who have few work and family roles. In our simulation exercise, these two strategies jointly reduced the mortality gap between US and Finnish women by more than 75 percent. These recommended approaches are further bolstered by our finding that US women's mortality disadvantage was negligible among women with all three work-family roles and striking among women who were neither married nor employed.4 These patterns imply that access to health-enhancing resources is more tightly bound to one's employment and marital status in the United States than it is in Finland, where social and economic supports are widely available.

A comprehensive policy approach could help diminish some of the obstacles faced by US women in engaging in work and family roles. For instance, national policies could improve the availability and quality of employment for all US women, regardless of education level or parental status. Shoring up the financial and fringe benefits of part-time employment in the United States to resemble many European countries could also be very beneficial (Gornick and Meyers 2005; Williams 2001). In addition, policies are needed to mitigate the challenges of combining employment with childrearing, such as universal childcare and family leave.

Strategies that do not directly fall within the domain of work-family reconciliation could also help shrink the longevity disadvantage. A few examples include improvements to public-transportation systems to facilitate access to employment and realigning the school day to match the workday. Current policies should also be evaluated to ensure that they do not unintentionally discourage adults from combining multiple roles. For example, some scholars propose that combining work and marriage may have become incompatible for disadvantaged US mothers, due to certain provisions of welfare-to-work policies (Cherlin and Fomby 2005).

It is important to note that the strategies discussed above implicitly assume that women possess the requisite health to engage in work and family roles. However, this assumption will not hold for everyone and should temper the expected impact of the recommendations. Taking the childcare recommendation as an example, the US General Accounting Office estimates that providing a full subsidy for poor or near-poor mothers who pay for childcare would not increase the proportion working to 100 percent, but rather to 44–57 percent (GAO 1994). The reasons are myriad and complex and partly reflect the poor health of many low-income US women and their children, which precludes many women from engaging in paid work (Meyers, Heintze, and Wolf 2002).

Limitations

Some limitations of the study should be noted. First, our work-family measures were collected at one point in time for US women. Work-family histories may have provided additional insights; however, the data sets used here are the best for this study, given the large number of deaths required. To assess the extent to which this might affect the results, we replicated table 3 for Finnish women using data that annually updated their work and family roles (analyses available upon request). Results were very similar. The employment-by-motherhood interaction terms were marginally attenuated (6–15 percent smaller, depending on marital status) but remained highly significant (p < 0.001) and corroborated the conclusions from the original table.

Another limitation is that we did not have good data on spousal income in the US survey. This would have allowed us to test the interpretation that access to material well-being through a spouse explains why married US mothers were less likely to be employed than married Finnish mothers. Future studies should examine this explanation. It is also possible that US culture is simply less favorable toward women combining work and family. While we cannot test this possibility with our data, extant research offers little support. A study of 32 countries found that the percentage of women who stated that mothers of preschoolers should not be employed was 42 percent in the United States and 38 percent in Finland (Charles and Cech 2010).

Another potential limitation is that we did not examine mortality among women over 60 years of age. However, the benefits of following respondents into these later ages may be offset by the increased likelihood of changes to their baseline work-family context. We also did not have comparable information in both data sets on subjective measures of work-family life, such as marital quality, which can moderate the mortality effects of work-family roles. Finally, while the data did not allow us to account for selection into work-family roles (i.e., we do not know if respondents were not working due to poor health), studies using longitudinal data find that these roles are salubrious for women's health even after accounting for unequal selection of healthier and advantaged women into the roles (e.g., Frech and Damaske 2012; Pavalko and Smith 1999).

Conclusions

In contrast to the United States, Finland has a long history of government assistance for working parents, such as childcare and parental leave. Our findings provide mixed, indirect evidence on the effect of this assistance in explaining the longevity disadvantage of US women compared to their Finnish peers. Part of the disadvantage appears to reflect a lower prevalence of combining employment with childrearing among married US women compared to married Finnish women. Thus, US women may be missing out on the longevity benefits of engaging in multiple work and family roles. Another part of the disadvantage seems to reflect the comparatively high mortality of US women who do not engage in multiple work and family roles. These women may be particularly vulnerable in countries like the United States, where economic well-being and access to healthcare is tightly linked to employment and marital status, than in countries like Finland with broad institutional supports and strong safety nets. Taken together, the findings imply that implementing institutional supports for working parents and providing safety nets for adults with few work and family roles could shrink US women's longevity disadvantage. Our simulation exercise estimated that more than 75 percent of the disadvantage could potentially be eliminated by elevating US women's employment levels to match Finnish levels and reducing the mortality of US women who were non-married/non-employed to match their Finnish peers. We encourage further studies of how social-policy contexts have intersected with the changing landscape of work and family life to shape the longevity disadvantage of US women.

About the Authors

Jennifer Karas Montez is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Research Faculty in the Women's and Gender Studies Program at Case Western Reserve University. Her research examines inequalities in health and longevity at the intersections of gender, educational attainment, and geography. Recent publications have appeared in Demography, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, and American Journal of Public Health.

Pekka Martikainen is Professor of Demography in the Department of Social Research at the University of Helsinki. He has written on sociodemographic differences in mortality and on the health effects of unemployment and death of spouse. Current interests include changes and causes of socioeconomic differences mortality, and social determinants of long-term care in aging populations. He is also working on the health effects of marital status and living arrangements and has been involved in cross-national comparisons of health inequalities.

Hanna Remes is Postdoctoral Researcher in the Department of SocialResearch at the University of Helsinki. Her research interests include social differentials in health and mortality, particularly the impact of parental background on young people's health, and the transition to adulthood. She has recently published work in Journal of Adolescent Health and Advances in Life Course Research.

Mauricio Avendano is Principal Research Fellow and Deputy Director at LSE Health at the London School of Economics, and adjunct Associate Professor at the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard School of Public Health. His research examines the impact of social exposures and social policies on health and health inequalities. Part of his work also studies the impact of employment on health, and the role of social policies in explaining cross-national differences in health.

Supplementary Material

Notes

In sensitivity analyses, we examined two alternative definitions of employment status. One definition combined employed and unemployed women, because unemployed women may also experience high time demands from work-related activities, such as looking for work and training for new job skills (e.g., Damaske 2011). Another definition excluded unemployed women from the analysis. The study results are consistent across all three specifications, possibly reflecting the small size of the unemployed-women group (around 3 percent of the US sample and 7 percent of the Finnish sample).

The NHIS-LMF began asking respondents if they were living with an unmarried partner in 1997. Thus, the US estimate of 5 percent for cohabiting unions reflects the period 1997–2006.

We thank one of the reviewers for suggesting this sensitivity analysis.

The high mortality of US women who were neither married nor employed compared with other US women has been reported elsewhere (Verbrugge 1983; Waldron, Weiss, and Hughes 1998). The explanation likely entails selection of the healthiest individuals into marriage and employment, as well as salubrious effects of marriage and employment. The reasons for the markedly higher mortality of US women who were neither married nor employed compared with their Finnish peers are unclear. The size of this group was comparable in both countries (6.8 percent in the United States, 8.5 percent in Finland), so it seems unlikely that US women in this group were more negatively selected than Finnish women. Moreover, the markedly higher mortality of non-married and non-employed US women was evident for even the highest-educated women, a group with generally good health. The higher mortality could partly reflect weaker social safety nets for non-workers in the United States. Future studies should investigate the mortality disparity among this group of women.

References

- Adams Patricia F., Kirzinger Whitney K., Martinez Michael E. 2012. Summary Health Statistics for the US Population: National Health Interview Survey. Vital Health Stat 10(255): National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Avendano Mauricio, Glymour M. Maria, Banks James, Mackenbach Johan P. 2009. “Health Disadvantage in US Adults Aged 50 to 74 Years: A Comparison of the Health of Rich and Poor Americans with That of Europeans.” American Journal of Public Health 99:540-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendano Mauricio, Kawachi Ichiro. 2011. “Invited Commentary: The Search for Explanations of the American Health Disadvantage Relative to the English.” American Journal of Epidemiology 173:866-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendano Mauricio, Kawachi Ichiro. 2014. “Why Do Americans Have Shorter Life Expectancy and Worse Health Than Do People in Other High-Income Countries?” Annual Review of Public Health 35:307-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendano Mauricio, Kok Renske, Glymour Maria, Berkman Lisa, Kawachi Ichiro, Kunst Anton, Mackenbach Johan, with support from members of the Eurothine Consortium 2010. “Do Americans Have Higher Mortality Than Europeans at All Levels of the Education Distribution? A Comparison of the United States and 14 European Countries.” In International Differences in Mortality at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources, edited by Crimmins E. M., Preston S. H., Cohen B., 313-32. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett Rosalind Chait, Hyde Janet Shibley. 2001. “Women, Men, Work, and Family: An Expansionist Theory.” American Psychologist 56:781-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman Lisa F., Buxton Orfeu, Ertel Karen A., Okechukwu Cassandra. 2010. “Managers' Practices Related to Work-Family Balance Predict Employee Cardiovascular Risk and Sleep Duration in Extended-Care Settings.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15:316-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Suzanne M., Robinson John P., Milkie Melissa A. 2007. Changing Rhythms of American Family Life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Blau Francine D. 1998. “Trends in the Well-Being of American Women, 1970–1995.” Journal of Economic Literature 36:112-65. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2014. Household Data Annual Averages. Washington, DC. http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat22.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Charles Maria, Cech Eric. 2010. “Beliefs about Maternal Employment.” In Dividing the Domestic: Men, Women, and Household Work in Cross-National Perspective, edited by Treas J., Drobnic S., 147-74. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J. 2010. “Demographic Trends in the United States: A Review of Research in the 2000s.” Journal of Marriage and Family 72:403-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J., Fomby Paula. 2005. “Welfare, Work, and Changes in Mothers' Living Arrangements in Low-Income Families.” Population Research and Policy Review 23:543-65. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Philip N., Bianchi Suzanne M. 1999. “Marriage, Children, and Women's Employment: What Do We Know?” Monthly Labor Review (December):22-31. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins Eileen M., Preston Samuel H., Cohen Barney. 2011. International Differences in Mortality at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby Faye J. 1991. Juggling: The Unexpected Advantages of Balancing Career and Home for Women and Their Families. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Damaske Sarah. 2011. For the Family? How Class and Gender Shape Women's Work. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elo Irma T., Martikainen Pekka, Smith Kirsten P. 2006. “Socioeconomic Differentials in Mortality in Finland and the United States: The Role of Education and Income.” European Journal of Population 22:179-203. [Google Scholar]

- England Paula, Garcia-Beaulieu Carmen, Ross Mary. 2004. “Women's Employment among Blacks, Whites, and Three Groups of Latinas: Do More Privileged Women Have Higher Employment?” Gender and Society 18:494-509. [Google Scholar]

- England Paula, Gornick Janet, Shafer Emily Fitzgibbons. 2012. “Women's Employment, Education, and the Gender Gap in 17 Countries.” Monthly Labor Review (April):3-12. [Google Scholar]

- Ertel Karen A., Koenen Karestan C., Berkman Lisa F. 2008. “Incorporating Home Demands into Models of Job Strain: Findings from the Work, Family & Health Network.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 50:1244-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finland Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. 2000. Early Childhood Education and Care Policy in Finland: Background Report Prepared for the OECD Thematic Review of Early Childhood Education and Care Policy. http://www.oecd.org/finland/2476019.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Frech Adrianne, Damaske Sarah. 2012. “The Relationships between Mothers' Work Pathways and Physical and Mental Health.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 53:396-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frone Michael R. 2000. “Work-Family Conflict and Employee Psychiatric Disorders: The National Comorbidity Survey.” Journal of Applied Psychology 85:888-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frone Michael R., Russel Marcia, Cooper M. Lynne. 1997. “Relation of Work-Family Conflict to Health Outcomes: A Four-Year Longitudinal Study of Employed Parents.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 70:325-35. [Google Scholar]

- General Accounting Office (GAO). 1994. Child Care: Child-Care Subsidies Increase Likelihood That Low-Income Mothers Will Work. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick Janet C., Meyers Marcia K. 2005. Families That Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick Janet C., Meyers Marcia K., Ross Katherin E. 1997. “Supporting the Employment of Mothers: Policy Variation across Fourteen Welfare States.” Journal of European Social Policy 7:45-70. [Google Scholar]

- Gove Walter R. 1972. “The Relationship between Sex Roles, Marital Status, and Mental Illness.” Social Forces 51:34-44. [Google Scholar]

- Haataja Anita, Kauhanen Merja, Nätti Jouko. 2011. Underemployment and Part-Time Work in the Nordic Countries. Helsinki: Kela Online Working Papers 31. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/28810. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann Jody. 2000. The Widening Gap: Why America's Working Families Are in Jeopardy and What Can Be Done about It. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y. 2013. “Mortality under Age 50 Accounts for Much of the Fact That US Life Expectancy Lags That of Other High-Income Countries.” Health Affairs 32:459-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Mortality Database. n.d. Human Mortality Database. http://www.mortality.org. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Jerry A., Gerson Kathleen. 2004. The Time Divide: Work, Family, and Gender Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen N. W. H., Kant I. J., van Amelsvoort L. G. P. M., Kristensen T. S., Swaen G. M. H., Nijhuis F. J. N. 2006. “Work-Family Conflict as a Risk Factor for Sickness Absence.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 63:488-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn Matthijs. 2013. “The Educational Gradient in Marriage: A Comparison of 25 European Countries.” Demography 50:1499-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman Gayle, Uhlenberg Peter. 2000. “The Influence of Parenthood on the Work Effort of Married Men and Women.” Social Forces 78:931-49. [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen Seppo, Joutsenniemi Kaisla, Martelin Tuija, Martikainen Pekka. 2007. “Mortality Differences According to Living Arrangements.” International Journal of Epidemiology 36:1255-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legerski Elizabeth Miklya. 2012. “The Cost of Instability: The Effects of Family, Work, and Welfare Change on Low-Income Women's Health Insurance Status.” Sociological Forum 27:641-57. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis D., Richardson D. B., Elliott L. 2005. “Poisson Regression Analysis of Ungrouped Data.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 62:325-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyonette Clare, Kaufman Gayle, Crompton Rosemary. 2012. “‘We Both Need to Work’: Maternal Employment, Childcare, and Health Care in Britain and the USA.” Work, Employment, and Society 25:34-50. [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen Pekka. 1995. “Women's Employment, Marriage, Motherhood, and Mortality: A Test of the Multiple Role and Role Accumulation Hypotheses.” Social Science & Medicine 40:199-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers Marcia K., Heintze Theresa, Wolf Douglas A. 2002. “Child Care Subsidies and the Employment of Welfare Recipients.” Demography 39:165-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Population Center. 2012. Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center, Integrated Health Interview Series: Version 5.0. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; http://www.ihis.us. [Google Scholar]

- Moen Phyllis, Dempster-McClain Donna, Williams Robin M. 1992. “Successful Aging: A Life-Course Perspective on Women's Multiple Roles and Health.” American Journal of Sociology 97:1612-38. [Google Scholar]

- Moen Phyllis, Roehling Patricia. 2005. The Career Mystique: Cracks in the American Dream. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montez Karas Jennifer, Sabbath Erika, Glymour M. Maria, Berkman Lisa F. 2014. “Trends in Work-Family Context among US Women by Education Level, 1976 to 2011.” Population Research and Policy Review 33:629-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray John E. 2000. “Marital Protection and Marital Selection: Evidence from a Historical-Prospective Sample of American Men.” Demography 37:511-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2009. The National Health Interview Survey (1986–2004) Linked Mortality Files, Mortality Follow-Up through 2006: Matching Methodology. Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. 2011. Explaining Divergent Levels of Longevity in High-Income Countries. Edited by Crimmins E. M., Preston S. H., Cohen B. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi Kei M. 2009. “Change in Work-Family Conflict among Employed Parents between 1977 and 1997.” Journal of Marriage and Family 71:15-32. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2008. Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2010. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Stat. doi:10.1787/Data-00285-En. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/data/oecd-stat_data-00285-en. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2014. OECD Family Database. http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database. [Google Scholar]

- Padavic Irene, Reskin Barbara. 2002. Women and Men at Work. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko Eliza K., Smith Brad. 1999. “The Rhythm of Work: Health Effects of Women's Work Dynamics.” Social Forces 77:1141-62. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit Becky, Hook Jennifer. 2005. “The Structure of Women's Employment in Comparative Perspective.” Social Forces 84:779-801. [Google Scholar]

- Raley R. Kelly, Bumpass Larry L. 2003. “The Topography of the Divorce Plateau: Levels and Trends in Union Stability in the United States after 1980.” Demographic Research 8:245-60. [Google Scholar]

- Ray Rebecca, Gornick Janet C., Schmitt John. 2009. Parental Leave Policies in 21 Counties: Assessing Generosity and Gender Equality. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/parental_2008_09.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti Rena L., Matthews Karen A., Waldron Ingrid. 1989. “Employment and Women's Health: Effects of Paid Employment on Women's Mental and Physical Health.” American Psychologist 44:1394-1401. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker Jason. 2007. “Working More and Feeling Better: Women's Health, Employment, and Family Life 1974–2004.” American Sociological Review 72:221-38. [Google Scholar]

- Spain Daphne, Bianchi Suzanne M. 1996. Balancing Act: Motherhood, Marriage, and Employment among American Women. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits Peggy A. 1986. “Multiple Identities: Examining Gender and Marital Status Differences in Distress.” American Sociological Review 51:259-72. [Google Scholar]