Abstract

Objective Recent massive investment in electronic health records (EHRs) was predicated on the assumption of improved patient safety, research capacity, and cost savings. However, most US health systems and health records are fragmented and do not share patient information. Our study compared information available in a typical EHR with more complete data from insurance claims, focusing on diagnoses, visits, and hospital care for depression and bipolar disorder.

Methods We included insurance plan members aged 12 and over, assigned throughout 2009 to a large multispecialty medical practice in Massachusetts, with diagnoses of depression (N = 5140) or bipolar disorder (N = 462). We extracted insurance claims and EHR data from the primary care site and compared diagnoses of interest, outpatient visits, and acute hospital events (overall and behavioral) between the 2 sources.

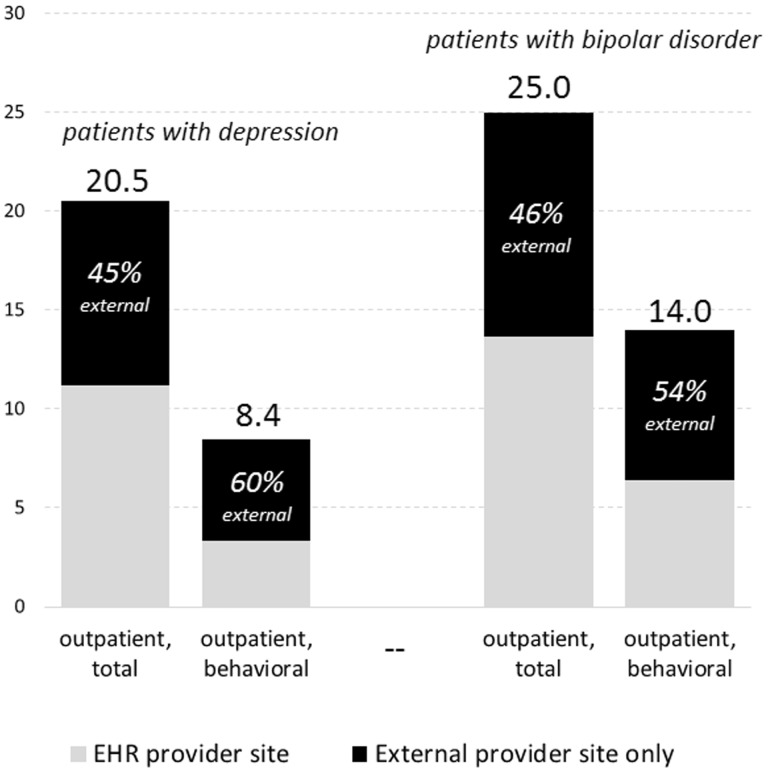

Results Patients with depression and bipolar disorder, respectively, averaged 8.4 and 14.0 days of outpatient behavioral care per year; 60% and 54% of these, respectively, were missing from the EHR because they occurred offsite. Total outpatient care days were 20.5 for those with depression and 25.0 for those with bipolar disorder, with 45% and 46% missing, respectively, from the EHR. The EHR missed 89% of acute psychiatric services. Study diagnoses were missing from the EHR’s structured event data for 27.3% and 27.7% of patients.

Conclusion EHRs inadequately capture mental health diagnoses, visits, specialty care, hospitalizations, and medications. Missing clinical information raises concerns about medical errors and research integrity. Given the fragmentation of health care and poor EHR interoperability, information exchange, and usability, priorities for further investment in health IT will need thoughtful reconsideration.

Keywords: electronic health records, mental disorders, validation studies, health information exchange, health care systems

INTRODUCTION

In a push to improve patient safety and reduce medical costs, as of 2015, over 500 000 US physicians and almost 6000 hospitals should have operating electronic health records (EHRs) and health information technology systems, or face penalties in Medicare reimbursement.1–3 These rules were in the 2009 The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, part of the economic stimulus that year.2,3 However, the fragmentation of US health care and the lack of interoperability and information exchange among the hundreds of EHR systems currently in use4–6 threaten the achievement of the underlying safety goals of this legislation, because the medical information in most EHRs is incomplete, which can result in medical errors.7

Insured individuals in the US are typically assigned to a primary care provider site, which may have an EHR, but individuals frequently receive specialty care at other locations which do not (and usually cannot) share data with that EHR. Computer decision support systems in EHRs are intended to protect patients at the time of prescription by guiding drug selection and dosing, and alerting physicians about dangerous drug-drug or drug-disease interactions. However, increased physician reliance on computer decision support in the present context of fragmentation and incomplete data may lead to poor-quality care and medical injury.8 For example, duplicated drug orders (in different EHRs within the same hospital) resulted in excess administration of insulin, leading to the death of a patient.9 A study of recent malpractice filings identified 147 cases where EHRs contributed to patient harm; 46 of those resulted in patient death.9,10

We hypothesized that fragmentation might be especially common in mental health care, because patients may protect their privacy by seeking behavioral care at a separate location from their somatic care.11,12 Primary care physicians then not only run the risk of medication errors, but also miss opportunities to encourage adherence to mental health visits and medications. Treatment adherence is particularly poor among mentally ill outpatients and can lead to adverse outcomes, including hospitalization.13–15

While fragmentation and incomplete clinical data in EHRs are recognized problems, almost no published data estimate their extent. Since health insurers maintain claims data on almost all drugs and health services received by a covered population, insurance claims can validate the completeness of mental health care data in provider EHRs. In this report, we compared the information recorded in a typical EHR at a large premier interdisciplinary practice with data from insurance claims during the same period. We focused on diagnoses, outpatient and emergency department visits, and hospitalizations for depression and bipolar disorder, common conditions that may be treated with a combination of psychotropic drugs and ongoing outpatient treatment. These mood disorders affect roughly 10% of the adult population and impose major social costs due to functional impairment, suicidality, health care use, and lost work productivity16–19; for the year 2000, the economic burden of depression alone in the US was estimated to be $83 billion.20 We also included overall health services in our analyses of missingness, as these results have important implications for both patients with mental illness and other patients.

METHODS

Study Population and Variables

Our study population included members of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care (HPHC) aged 12 and over who were assigned for primary care throughout 2009 to Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (HVMA), a multispecialty medical practice serving over 300 000 in Massachusetts. HPHC is the second largest health insurer in New England with over 1 million members, roughly 15% of whom are assigned to HVMA. Both organizations are national health care quality leaders21,22 while typifying the fragmented US health system, in that HPHC contracts with multiple provider organizations and HVMA cares for patients with a mix of insurance arrangements. HMVA was an early pioneer in the use of EHRs and since 2000 has relied on Epic™, the most popular EHR system in the US.23–25

Our 2 study cohorts included members with at least 1 claims diagnosis26,27 of depression (but no diagnosis of bipolar disorder, N = 5140), or diagnosis of bipolar disorder (N = 462) in 2009. Together these comprised 13% of continuously enrolled HPHC/HVMA adolescents and adults.

Study outcomes included depression or bipolar diagnosis in the EHR from a 2009 clinical encounter; claims-based counts of outpatient care days (total and behavioral), hospitalizations, and emergency department visits; and comparable counts of face-to-face clinical care days from the EHR. Outpatient and inpatient care days in the EHR were combined because outpatient hospital visits could not be classified automatically to outpatient or inpatient status. We excluded laboratory-only and imaging-only events from counts in both data sources. Descriptive study measures were obtained from insurer enrolment files (age, sex), US census data linked to member address (neighborhood-level educational attainment), and pharmacy claims (psychotropic medication use).

Analyses

Study data were thoroughly checked for internal and external consistency.28–30 We calculated the proportion of each cohort whose diagnosis of interest appeared in 2009 structured EHR data. We compared service utilization results using several approaches. First, within the insurance claims alone, we calculated the average number of distinct days of outpatient care (total and behavioral, separately) at the EHR site versus days with care only received elsewhere.

Next, we identified outpatient care days, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits in claims (total and behavioral, separately) and calculated the proportion of these that could not be found in the EHR data (by matching on patient ID, service date, and type). Finally, we tallied all days of care (inpatient or outpatient combined, total and behavioral separately) in the EHR, and calculated the proportion of these that could not be found in the claims data.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study cohorts. Both patient cohorts were more likely to be female when compared to members overall. A majority of the study population received antidepressant medication during the observation year, and roughly 3 out of 4 patients with bipolar illness received a mood stabilizer (anticonvulsant or lithium). Nineteen percent of patients with bipolar illness experienced an acute psychiatric event at a hospital during the year. Only 72.7% of patients with depression and 72.3% of those with bipolar disorder had their diagnosis recorded in a 2009 EHR clinical encounter.

Table 1:

Selected characteristics of the study cohorts and the prevalence of service use in the study year, according to insurance claims and the primary site EHR

| Characteristics and Service Use | All insured members assigned to EHR practice site for primary care | Cohort having depression diagnosis in claims | Cohort having bipolar disorder diagnosis in claims |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 43 582 | N = 5140 | N = 462 | |

| Characteristic (%) | |||

| Aged 12–19 years | 14.0 | 9.0 | 16.5 |

| Aged 20–39 years | 27.0 | 25.7 | 30.1 |

| Aged 40–64 years | 54.2 | 60.5 | 50.6 |

| Aged 65 + years | 4.7 | 4.8 | 2.8 |

| Female sex | 54.4 | 67.1 | 61.5 |

| Low-education neighborhood | 23.5 | 21.1 | 20.3 |

| Prevalence of any service use, according to claims (%) | |||

| Overall | |||

| ED visit (w/o hospital admission) | – | 23.5 | 35.7 |

| Hospital admission | – | 11.8 | 23.2 |

| Either an ED or a hospital admission | – | 27.2 | 39.8 |

| Behavioral | |||

| Mental health specialist visit | 85.8 | 97.2 | |

| Psychiatric ED visit (w/o hospital admission) | – | 2.8 | 13.4 |

| Psychiatric hospital admission | – | 2.4 | 16.7 |

| Either psychiatric ED or psychiatric hospital admission | – | 3.7 | 18.8 |

| Medication dispensing, according to claims | |||

| Any antidepressant use (%) | – | 64.7 | 59.7 |

| Avg months supplied among antidepressant users | – | 10.0 | 10.6 |

| Any antipsychotic use (%) | – | 4.9 | 47.4 |

| Avg months supplied among antipsychotic users | – | 6.3 | 8.1 |

| Any mood stabilizer use (%) | – | 29.6 | 76.0 |

| Avg months supplied among mood stabilizer users | – | 5.6 | 11.6 |

| Prevalence, according to EHR (%) | |||

| Any depression diagnosis | – | 72.7 | – |

| Any bipolar disorder diagnosis | – | – | 72.3 |

| Any mental health specialist visit | – | 58.0 | 74.0 |

All individuals in the table had HPHC insurance and HVMA primary care assignment throughout 2009. A “low-education” neighborhood had >50% of adults aged 25+ who had attained no more than high school–level education. Individuals in the depression cohort had 1 or more ICD-9 code for depression (296.2x, 296.3x, 300.4x, 301.12, 309.0x, 309.1x, 309.28, or 311.x) in an inpatient or outpatient claim in 2009, and no diagnosis of bipolar disorder; individuals in the bipolar disorder cohort had 1 or more bipolar codes (296.0x, 296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, or 296.8x) in an inpatient or outpatient claim in 2009. We defined acute services as psychiatric using either the institutional code or primary/admitting diagnosis. We included EHR diagnoses from structured fields in outpatient or inpatient encounters, not other encounter types (eg, telephone contacts, letters) or free-text fields. Hyphens indicate outcomes that were not measured.

In general, service events appearing in the EHR also appeared in claims data. However, a substantial majority of behavioral service events observed in claims for patients with depression and bipolar disorder were missing from the EHR.

Sites of Outpatient Care Identified in Insurance Claims

Based on claims data only, patients with depression had an average of 3.3 behavioral visits (ie, outpatient care days) with a provider at the EHR site (HVMA) in 2009, and another 5.1 visits (or 60% of total behavioral) outside of the EHR site (Figure 1). Patients with bipolar disorder had an average of 6.4 behavioral visits at the EHR site versus 7.6 (54%) at external provider sites.

Figure 1:

Average number of days with outpatient care per patient in 2009, total and behavioral, and percentage of care days occurring at external provider sites, according to insurance claims. In the analyses below, we defined “behavioral” as having any mental health specialist provider. We conservatively classified days that included care at both the EHR site and external providers (∼3% of total) as occurring at the EHR site. Although all subjects were assigned to HVMA for their primary care, we conservatively classified care occurring beyond HVMA in the broader Atrius provider network as occurring at the EHR provider site, because Atrius providers share a single EHR. For all categories of care shown below, average days at the EHR site as derived from claims were identical to average days at the EHR site as derived from EHR data (average EHR counts not shown).

Use of external services was not limited to mental health care. Our claims analyses indicated that patients with depression averaged 11.2 outpatient visits at the EHR site and 9.3 additional visits outside of the EHR site; that is, 45% of outpatient visits of all types were received at external sites (generally not captured by the EHR). Patients with bipolar disorder had 13.6 outpatient visits at the EHR site plus 12.2 visits externally (ie, 46% of total outpatient visits were external; Figure 1).

Cross-Linkage of Specific Care Events between the 2 Data Sources

When we linked data from both sources to match specific events across systems, the results were very similar: roughly half of the outpatient care days in claims could not be matched to clinical contacts recorded in the EHR (Table 2, Claims events). Consistent with our data in Table 1, the extent of missingness observed in these matched analyses was greater for behavioral services as compared to overall outpatient care.

Table 2.

Matched analyses showing service events as enumerated in 1 data source and the percentage of those events that were missing in the second data source, for claims events and EHR events

| Data source and type of service | Depression | Bipolar Disorder | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 5140) | (N = 462) | |||

| Count in claims data | Percentage of events in claims data that were missing from EHR data (%) | Count in claims data | Percentage of events in claims data that were missing from EHR data (%) | |

| (a) Claims events | ||||

| Outpatient care days (cohort mean) | ||||

| Total | 20.5 | 45 | 25.0 | 43 |

| Behavioral | 9.4 | 57 | 15.6 | 53 |

| Emergency department visits (cohort total) | ||||

| Total | 1646 | 47 | 262 | 57 |

| Behavioral | 146 | 88 | 71 | 92 |

| Hospitalizations (cohort total) | ||||

| Total | 1174 | 26 | 210 | 53 |

| Behavioral | 229 | 90 | 148 | 88 |

| count in EHR data | Percentage of events in EHR data that were missing from claims data (%) | count in EHR data | percentage of events in EHR data that were missing from claims data (%) | |

| (b) EHR events | ||||

| Days with clinical care (cohort mean, inpt or outpt) | ||||

| Total | 11.2 | 7 | 14.0 | 6 |

| Behavioral | 4.2 | 2 | 7.5 | 3 |

We defined the percentage missing as the proportion of events in the first data source that did not have matches in the second data source. Matching required the same patient ID, event type, and service date (±1 day), and for the behavioral subset, we required the presence of behavioral coding. For outpatient care days in claims and all care in the EHR, “behavioral” was defined as having any mental health diagnosis, procedure, or provider specialty code (ie, a broader definition than in the figure). For ED visits and hospitalizations in claims, “behavioral” was defined as having a psychiatric institutional code or psychiatric primary/admitting diagnosis. EHR events may be missing from claims as a result of duplicate coverage, limits on coverage, partial encounters, or other reasons.

Hospital-based events were also substantially underrepresented in the EHR. Among all acute psychiatric services in claims (594 hospital admissions or ED visits), 89% were missing from the EHR. Overall, 43% of all hospital-based events (hospital or ED, psychiatric and non-psychiatric) were missing from the EHR. By contrast, clinical events appearing in the EHR could be matched to events in claims in 93–98% of cases (Table 2, EHR events).

DISCUSSION

Very little published data exists on the completeness of medical information in primary care EHRs.31–33 We assessed EHR completeness for patients with depression or bipolar disorder by quantitatively comparing diagnoses and service use in a major primary care site EHR to those in claims data during the same period. While a broad range of specialty services is available at the primary site studied and some specialist care was documented in their EHR, roughly a quarter of current depression and bipolar diagnoses and more than half of behavioral visits were missing. Data missingness was similarly high for non-behavioral care, both inpatient and outpatient. Nearly 90% of acute psychiatric services at hospital facilities, representing more severe exacerbations of mental illness, were not captured in the EHR.

The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) defines EHR “meaningful use” with detailed criteria, including requirements that an EHR contain some diagnostic information on each patient and checks for medication interactions, and is capable of exchanging clinical data with other providers.34 Higher stages of meaningful use are generally defined by the presence of additional functions. However, the CMS criteria do not specify the quality of the data or the practical usability of any functions. Missing data undermines many central EHR functions. Published reports touting the anticipated benefits of the recent rapid adoption of EHRs35–38 (eg, improved safety and quality of care) should be tempered by frank examinations of EHRs as they currently exist. Above all, individual providers and health system leaders need to be fully cognizant of the information gaps and disconnects that lie behind the screen. Features that are intended to improve care and protect patients from harm may be inadequate in typical fragmented health systems, offering false comfort.

Missing clinical information is likely to result in medication errors and other patient harms.39 Concurrent psychiatric treatment has multiple implications for the delivery of safe, high-quality somatic care. For example, use of antipsychotic agents should be accompanied by enhanced monitoring for cardiometabolic complications,40 and many commonly used pain relievers carry extra risks in the presence of SSRI or lithium use.41 Primary care practitioners with knowledge of their patients’ previous depression treatment will be more likely to care for important conditions such as postpartum depression42 or emergent bipolar disorder.43 EHRs are often credited with improvements in safety when compared with earlier paper and manual systems.44,45 However, to the extent that medical decision-making grows increasingly automated and reliant on new information technologies,46–48 care will suffer if there is overreliance on data that are in fact incomplete.39 We found no studies assessing data completeness in paper charts or whether completeness improved or deteriorated after a shift to electronic records.

Given extensive information missingness, epidemiological and evaluative studies that rely on data from typical provider EHRs49–51 will undercount diagnosed patient populations and their use of services and medications. With appropriate privacy safeguards, EHRs can assist in clinical research: rich narrative data and test results, for example, may be useful in case identification and measurement of severity for small, nonrepresentative studies. However, for population-level studies, insurance claims are more complete and systematic, providing a foundation for reliable research.52–58

Our findings should be understood in the context of several limitations. We focused on patients with mental illness and their behavioral care services, and behavioral care may represent a unique case. It is often segregated by location, though the multispecialty EHR site in our study (HVMA) has behavioral clinics in almost all locations. Insurers and employer sponsors frequently offer and manage behavioral care benefits separately from other care. All study subjects had behavioral coverage through the insurer HPHC, which then carves out coverage to a managing vendor; this arrangement did not affect our access to behavioral claims data. At HVMA, a privacy firewall in the EHR prevents other clinicians from viewing psychiatric diagnoses entered by mental health specialists. Thus, our study greatly underestimates the missingness of behavioral data experienced by primary care providers who use the EHR. However, all diagnoses were available in the de-identified data abstracted for this study.

While behavioral health care is unique, it is important to emphasize that our findings demonstrate that the problem of incomplete clinical data in the EHR is not limited to behavioral care. Rates of missingness were high among both behavioral events and overall events, both in and outside the hospital. Specialist care of all types is particularly likely to be underrepresented in a primary care EHR.59 HVMA is a multispecialty provider group; we expect that in many other simpler primary care settings, the extent of missing specialist care in the EHR would be far higher than at HVMA.

Our study did not include medication data from the EHR; this would include initial prescription orders written by internal providers, dispensing at in-house pharmacies, and patient-reported medications. Given the extent of outside service use we observed and the well-documented problem of primary nonadherence (ie, not filling prescriptions),60 an attempt at measuring drug utilization based on data in the EHR would underestimate use, as compared to essentially complete insurer-paid pharmacy claims.58,61,62

Our analyses focused on current service encounters and the diagnoses made at these encounters, both of which were underrepresented in the EHR. EHR data often contain other potentially useful information about mental and non-mental health concerns that are not available in claims, such as diagnoses from current letters, telephone calls, and electronic correspondence; diagnoses entered in earlier years on the patient’s “active problem” list; and free-text clinician comments. These supplementary internal data may be available for clinicians using the EHR during encounters even if current diagnoses and services from off-site utilization are missing. However, these supplementary items represent “softer” data, which typically do not feed into patient safety and management functions like Clinical Decision Support. Similarly, it is possible for providers at HVMA to access patient information at some external partnering institutions, but such inquiries must be conducted individually; this information does not flow into the EHR. Finally, HPHC provides claims data extracts to HVMA for a minority of members in managed care-style financial risk–sharing arrangements; these claims are used in some HVMA case management activities but, again, do not feed into the EHR or its safety functions. The general attributes of the HVMA EHR have not changed since the time of our study and the EHR meets CMS meaningful use benchmarks.

We present findings from one large multisite, multispecialty setting that may not be generalizable to other settings. For example, in a rural setting, patients may have fewer choices for specialist care and may receive a higher proportion of their care at their primary site. Nevertheless, the continuing fragmentation of US health care59 ensures that incomplete clinical data in primary site EHRs is a widespread problem.

Better interoperability could be facilitated with national technical standards. Federal policies to date have tilted too far in accommodating EHRs vendors’ desire for flexible, voluntary standards. The incompatible products that result undermine public health goals and can lock providers in to proprietary systems that cannot easily share data. Other barriers to information exchange between entities include provider concerns about costs and liability and patient concerns about confidentiality. Future progress may be possible through more accountable insurer-provider arrangements which include the sharing of data from claims with EHRs and clinicians, patient-driven data-sharing mechanisms, and regulations requiring more complete, timely, and usable data flows where access already exists.4,5,63,64 EHRs have long been touted as a technology that will advance patient safety in the United States, and enormous public and private investment has been funneled into EHR development in recent years.65,66 Adoption of EHRs among US office-based physicians increased from 48% in 2009 to 83% in 2014,67 though the extent of their actual use and effectiveness is unknown. In this research, we found that the lack of integration, interoperability, and exchange in US health care resulted in a major EHR missing roughly half of the clinical information. Policymakers should put more focus on the quality and utility of health information and ways these can be improved, instead of simply tallying up EHR purchases and supposed capabilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank our colleagues in the Mental Health Research Network consortium for financial and intellectual support, our colleagues at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates and Atrius Health in Massachusetts for data access and assistance, Irina Miroshnik (Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston) for advice on data analyses, and Ross Koppel (School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) for critical reading and content advice.

FUNDING

This research was an infrastructure core activity of the Mental Health Research Network and was funded by a supplement from the National Institute of Mental Health to the existing Cancer Research Network, funded by the National Cancer Institute, and through a 3-year cooperative agreement with the NIMH (U19 MH092201, “Mental Health Research Network: A Population-Based Approach to Transform Research”).

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors affirm that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Health Forum LLC. Fast Facts on US Hospitals. 2015; http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/fast-facts.shtml. Accessed May 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright A, Henkin S, Feblowitz J, McCoy AB, Bates DW, Sittig DF. Early results of the meaningful use program for electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):779–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DesRoches CM, Worzala C, Bates S. Some hospitals are falling behind in meeting ‘meaningful use' criteria and could be vulnerable to penalties in 2015. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(8):1355–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandl KD, Szolovits P, Kohane IS. Public standards and patients' control: how to keep electronic medical records accessible but private. BMJ. 2001;322(7281):283–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontaine P, Ross SE, Zink T, Schilling LM. Systematic review of health information exchange in primary care practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(5):655–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Malley AS, Grossman JM, Cohen GR, Kemper NM, Pham HH. Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):177–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. A Report of the Committee on Quality of Health Care in America (Institute of MedicineReport). National Academics Press: Washington, DC: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridgely MS, Greenberg MD. Too many alerts, too much liability sorting through the malpractice implications of drug-drug interaction clinical decision support. St Louis University J Health Law Policy. 2012;5(2):257–296. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowland C. Hazards tied to medical records rush: Subsidies given for computerizing, but no reporting required when errors cause harm. Boston Globe. 2014. http://www.bostonglobe.com/news/nation/2014/07/19/obama-pushed-electronic-health-records-with-huge-taxpayer-subsidies-but-has-rebuffed-calls-for-hazards-monitoring-despite-evidence-harm/OV4njlT6JgLN67Fp1pZ01I/story.html [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruder DB. Malpractice Claims Analysis Confirms Risk in EHRs. 2014. http://psqh.com/january-february-2014/malpractice-claims-analysis-confirms-risks-in-ehrs. Accessed July 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger M, Wagner TH, Baker LC. Internet use and stigmatized illness. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1821–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

- 14.Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70 (Suppl 4):1–46; quiz 47–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, Sredl K. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(12):1128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goetzel RZ, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S. The health and productivity cost burden of the “top 10” physical and mental health conditions affecting six large U.S. employers in 1999. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang PS, Simon G, Kessler RC. The economic burden of depression and the cost-effectiveness of treatment. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(1):22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):1465–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The National Committee for Quality Assurance. Top 20 Private Health Insurance Plans. http://www.ncqa.org/ReportCards/HealthPlans/HealthInsurancePlanRankings/PrivateHealthPlanRankings20132014.aspx. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 22.Harvard Vanguard practices earn top accreditation. Lowell Sun. 2012. http://www.lowellsun.com/business/ci_20839136/harvard-vanguard-practices-earn-top-accreditation.

- 23.Grossman JH, Barnett GO, Koepsell TD, Neeson HR, Dorsey JL, Phillips RR. An Automated Medical Record System. JAMA. 1973;224(12):1616–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaywitz D. Epic challenge: what the emergence of an EMR giant means for the future of healthcare innovation. Forbes. 2012. http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidshaywitz/2012/06/09/epic-challenge-what-the-emergence-of-an-emr-giant-means-for-the-future-of-healthcare-innovation/2/. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppel R, Lehmann CU. Implications of an emerging EHR monoculture for hospitals and healthcare systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Sledge WH. Health and disability costs of depressive illness in a major U.S. corporation. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(8):1274–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olfson M, Crystal S, Gerhard T, Huang CS, Carlson GA. Mental health treatment received by youths in the year before and after a new diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(8):1098–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgkin D, Merrick EL, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, McLaughlin TJ. Does type of gatekeeping model affect access to outpatient specialty mental health services? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(1 Pt 1):104–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bryant-Comstock L, Stender M, Devercelli G. Health care utilization and costs among privately insured patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4(6):398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Elinson L, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA. 2002;287(2):203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koppel R. Is healthcare information technology based on evidence? Yearb Med Inform. 2013;8(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Amore JD, Mandel JC, Kreda DA, et al. Are Meaningful Use Stage 2 certified EHRs ready for interoperability? Findings from the SMART C-CDA Collaborative. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(6):1060–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):501–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumenthal D. Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1477–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buntin MB, Burke MF, Hoaglin MC, Blumenthal D. The benefits of health information technology: a review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):464–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones SS, Rudin RS, Perry T, Shekelle PG. Health information technology: an updated systematic review with a focus on meaningful use. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheikh A, Jha A, Cresswell K, Greaves F, Bates DW. Adoption of electronic health records in UK hospitals: lessons from the USA. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leviss J, Charney P. H.i.t or Miss: Lessons Learned from Health Information Technology Implementations, Second Edition. Chicago: American Health Information Management Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Diabetes Association. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther. 2007;29 (Suppl):2477–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baldessarini RJ, Faedda GL, Offidani E, et al. Antidepressant-associated mood-switching and transition from unipolar major depression to bipolar disorder: a review. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates DW, Gawande AA. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2526–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahoney CD, Berard-Collins CM, Coleman R, Amaral JF, Cotter CM. Effects of an integrated clinical information system on medication safety in a multi-hospital setting. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(18):1969–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anand V, Carroll AE, Downs SM. Automated primary care screening in pediatric waiting rooms. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1275–e1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryant AD, Fletcher GS, Payne TH. Drug interaction alert override rates in the Meaningful Use era: no evidence of progress. Applied Clin Inform. 2014;5(3):802–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1197–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beyer J, Kuchibhatla M, Gersing K, Krishnan KR. Medical comorbidity in a bipolar outpatient clinical population. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(2):401–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kohane IS, McMurry A, Weber G, et al. The co-morbidity burden of children and young adults with autism spectrum disorders. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e33224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dean BB, Lam J, Natoli JL, Butler Q, Aguilar D, Nordyke RJ. Review: use of electronic medical records for health outcomes research: a literature review. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(6):611–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Ross-Degnan D, Casteris CS, Bollini P. Effects of a limit on Medicaid drug-reimbursement benefits on the use of psychotropic agents and acute mental health services by patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(10):650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Law MR, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Adams AS. A longitudinal study of medication nonadherence and hospitalization risk in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu CY, Zhang F, Lakoma MD, et al. Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. BMJ. 2014;348:g3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Madden JM, Adams AS, LeCates RF, et al. Changes in drug coverage generosity and untreated serious mental illness: transitioning from Medicaid to Medicare Part D. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Penfold RB, Stewart C, Hunkeler EM, et al. Use of antipsychotic medications in pediatric populations: what do the data say? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(12):426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Townsend L, Walkup JT, Crystal S, Olfson M. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying depression using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21 (Suppl 1):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Behrman RE, Benner JS, Brown JS, McClellan M, Woodcock J, Platt R. Developing the Sentinel System: a national resource for evidence development. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):498–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care: a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fischer MA, Stedman MR, Lii J, et al. Primary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(4):284–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gellad WF, Grenard JL, Marcum ZA. A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: looking beyond cost and regimen complexity. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9(1):11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(4):323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mandl KD, Kohane IS. Escaping the EHR trap: the future of health IT. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2240–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rudin RS, Motala A, Goldzweig CL, Shekelle PG. Usage and effect of health information exchange: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riskin L, Koppel R, Riskin D. Re-examining health IT policy: what will it take to derive value from our investment? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):459–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soumerai SB, Starr D, Majumdar SR. How do you know which health care effectiveness research you can trust?. A Guide to Study Design for the Perplexed. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, US DHHS; Office-based Physician Electronic Health Record Adoption: 2004-2014. http://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/physician-ehr-adoption-trends.php. Accessed January 19, 2016.