Abstract

Purpose

To assist in determining barriers to an oncology career incorporating cancer prevention, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Cancer Prevention Workforce Pipeline Work Group sponsored surveys of training program directors and oncology fellows.

Methods

Separate surveys with parallel questions were administered to training program directors at their fall 2013 retreat and to oncology fellows as part of their February 2014 in-training examination survey. Forty-seven (67%) of 70 training directors and 1,306 (80%) of 1,634 oncology fellows taking the in-training examination survey answered questions.

Results

Training directors estimated that ≤ 10% of fellows starting an academic career or entering private practice would have a career focus in cancer prevention. Only 15% of fellows indicated they would likely be interested in cancer prevention as a career focus, although only 12% thought prevention was unimportant relative to treatment. Top fellow-listed barriers to an academic career were difficulty in obtaining funding and lower compensation. Additional barriers to an academic career with a prevention focus included unclear career model, lack of clinical mentors, lack of clinical training opportunities, and concerns about reimbursement.

Conclusion

Reluctance to incorporate cancer prevention into an oncology career seems to stem from lack of mentors and exposure during training, unclear career path, and uncertainty regarding reimbursement. Suggested approaches to begin to remedy this problem include: 1) more ASCO-led and other prevention educational resources for fellows, training directors, and practicing oncologists; 2) an increase in funded training and clinical research opportunities, including reintroduction of the R25T award; 3) an increase in the prevention content of accrediting examinations for clinical oncologists; and 4) interaction with policymakers to broaden the scope and depth of reimbursement for prevention counseling and intervention services.

INTRODUCTION

Oncologists have and are expected to play a significant role in cancer prevention. Oncologist clinical and research careers that emphasize cancer prevention may take a variety of forms, requiring skill sets often not emphasized in traditional clinical oncology fellowships. These skills include risk and genetic counseling for unaffected high-risk individuals as well as those with cancer, knowledge of appropriate surveillance and prophylactic treatment of high-risk individuals, early- and late-phase primary and secondary clinical prevention trial design, benign tissue sampling techniques for research purposes, knowledge of precancerous biology and experience with molecular biology techniques, and familiarity with epidemiology and biostatistics.1,2 An oncology work force adequately trained in primary and secondary prevention is necessary for implementation of interventions already known to reduce cancer incidence, and a critical mass with training in prevention research is required for new discovery.3 However, it is the opinion of many thought leaders that the number of oncologists engaged in cancer prevention activities, especially research, is dwindling. The reasons are uncertain, but according to a 2004 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) survey, 43% of oncologist respondents felt they were not adequately trained in prevention. Oncologists were also concerned about reimbursement for prevention services.2 Only scant attention has been paid to future manpower needs in the area of cancer prevention, in contrast to cancer treatment,4 although a few warning bells have been sounded.5,6 Furthermore, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) R25T award, created in 1991 to support multidisciplinary mentors and trainees and their initial research efforts in cancer prevention research, was discontinued in 2013.7

With the widening gap between demand for oncology services and the supply of new oncology trainees, the proportion of oncologists working in prevention is not likely to increase in the near future without corrective action. According to a recent study by ASCO, the demand for oncology services in the United States is expected to grow by 40% over the next 10 years, but the physician workforce will increase by only 25%, generating a shortfall of ≥ 2,500 oncologists by 2025.8 This may be a conservative estimate, given the recent information on oncology physician satisfaction, with 45% of > 1,000 individuals completing a survey reporting burnout.9,10 In 2012, the ASCO Cancer Prevention Committee identified the prevention research workforce as an issue of high priority, creating the Cancer Prevention Workforce Pipeline Work Group. The Cancer Prevention Workforce Pipeline Work Group initially reviewed data from the NCI, which in 2013 supported 30 training programs that had cancer prevention as a component. It was not clear how many of these trainees were oncology clinicians,11 although representatives from the NCI commented that few physicians had enrolled in the NCI Cancer Prevention Fellowship program in the last several years.

In view of its charge to determine the interest level and perceived barriers to cancer prevention research or clinical practice harbored by oncology fellows, the work group undertook a survey of both oncology fellowship program directors and oncology fellows in the United States. The findings from this survey and next-step recommendations are reported here.

METHODS

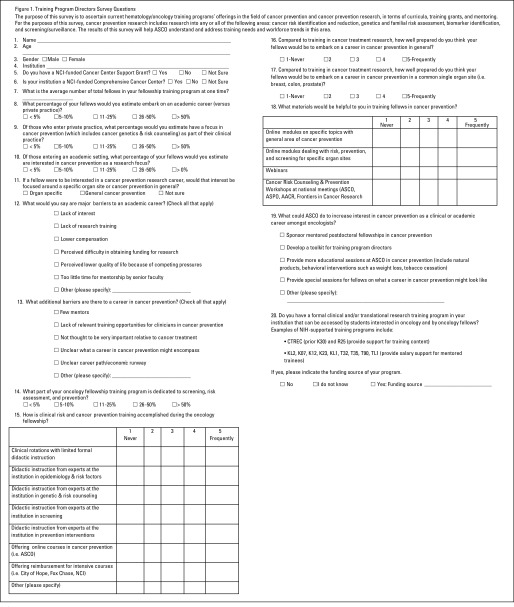

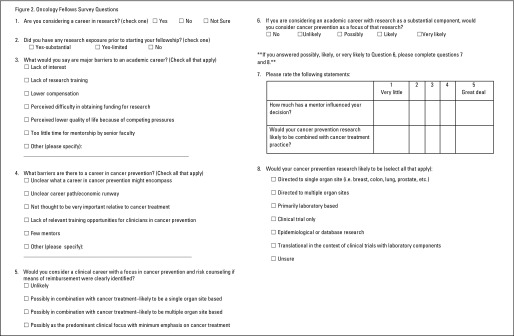

Separate surveys were created to be given to oncology fellows and their training directors to determine how they view careers in cancer prevention and identify potential barriers. These surveys contained similar questions adapted for the audience. Both surveys were first piloted at two of the work group member institutions: University of Kansas Medical Center and the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California Irvine. The final survey was approved by the ASCO Professional Development Committee. The training program director survey (Fig 1) was distributed as a hard copy at the ASCO training program fall 2013 retreat, at which 70 directors representing diverse sites of fellowship training across the United States were in attendance. The fellow survey questions (Fig 2) were incorporated into the ASCO annual in-training examination survey, given to 1,634 fellows and administered from February 25 to 26, 2014. Results were compiled by ASCO staff.

Fig 1.

Training program director survey questions. AACR, American Association for Cancer Research; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; ASPO, American Society of Preventive Oncology; CTREC, Center for Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer; NCI, National Cancer Institute; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Fig 2.

Oncology fellow survey questions.

RESULTS

Training Program Director Survey Results

Demographics of training directors and training programs.

Forty-seven (67%) of 70 training directors in attendance responded to the survey. Fifty-seven percent of these were male, and the average age was 49 years (range, 33 to 71 years). Institutions represented are listed in Appendix Table A1 (online only). The average number of fellows within the fellowship programs represented was 13 (range, four to 42). Forty-three percent of training director respondents stated that their institution had an NCI-funded cancer center support grant, and for 36.2%, this was a comprehensive cancer center grant. Responding directors estimated that at least 46% of fellows had formal clinical or translational research training as part of the program (Clinical and Translational Science Award, Center for Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer, K07, K12, K23, K30, KL1 or 2, R25, T32, T35, T90 or TL1, or other). A majority (70%) of oncology program training directors estimated that between 11% and 50% of their fellows embarked on a carrier in academic medicine, with the most frequent category of response being 11% to 25%.

Training director estimates of fellow interest in careers in cancer prevention.

Whether their fellows went into academic medicine or private practice, there was agreement among training directors (> 85%) that ≤ 10% would embark on a career with a focus in cancer prevention (including cancer genetics and risk counseling). For fellows interested in having a research career in cancer prevention, program directors thought the interest was likely to be organ specific (yes, 48.9%; unsure, 31.9%).

Training director opinions as to barriers to careers in academic medicine or cancer prevention.

Training directors cited difficulties in obtaining research funding (63.8%) as the most frequent barrier to an academic research career in general. Lack of interest and lower compensation were listed as barriers to a career in academic medicine by > 50% of program director respondents, and lack of research training and lower quality of life as a result of competing pressures were cited by > one third. Additional barriers to a career in cancer prevention included lack of mentors, cited by > 85% of respondents; lack of training opportunities for clinicians, unclear career path, and unclear economic future, cited by > two thirds; and lower importance relative to cancer treatment, cited by 47%. Frequent comments were that institutional cancer prevention programs were often headed by PhDs rather than MDs and that teaching or mentoring, if performed, was not done by clinicians, thus providing limited numbers of role models.

Opportunities for addressing barriers.

The survey also queried training directors on what types of materials would be most helpful to them in fellowship training in cancer prevention. Online modules dealing with risk prevention and screening, both in general and for specific organ sites, were thought to be the single most helpful training tool, but workshops at national meetings were also thought to be moderately helpful. In terms of what ASCO could do to raise interest in cancer prevention, all of the following were thought to be worthwhile by a majority of respondents: 1) a toolkit for program directors, 2) prevention educational sessions at ASCO meetings, 3) special sessions at ASCO meetings focused on what oncology careers emphasizing cancer prevention might look like, and 4) ASCO-sponsored mentored postdoctoral fellowships. Of these, the highest rating was for development of a toolkit.

Oncology Fellow Survey Results

Of the 1,634 fellows taking the examination, 1,306 (80%) completed the fellow survey prevention questions. An overwhelming majority (1,202) of the respondents were currently in a training program. Of the 1,233 fellows providing demographic data, 47% were female, and the average age was 34 years (range, 26 to 63 years). Eighty-seven percent had had some research training before beginning their fellowship, but this training was substantial for only 26%. In general, fellows' responses were as predicted by the training directors (Table 1 lists comparisons).

Table 1.

Comparisons of Answers in Training Program Director Versus Medical Oncology Fellow Surveys

| Variable | Training Program Director Respondents (n = 47; 67% of those queried) | Fellow Respondents (n = 1,306; 80% of those queried) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 49 (33-71) | 34 (26-63) |

| Female sex, % | 43 | 47 |

| NCI-funded cancer center support grant, % | 43 | NA |

| Formal research training in program, % | 46.5 | NA |

| Average No. of fellows in program (range) | 13 (4-42) | NA |

| Interested in academic career, % | 11-50 (70% of respondents) | 43 |

| Cancer prevention as focus in academic career, % | ≤ 10 (85% of respondents) | 15 (likely or very likely); 42 (possibly) |

| Organ specific, % | 49 | Approximately half |

| Cancer prevention as focus in private practice, % | ≤ 10 (87% of respondents) | 65 (would consider if combined with cancer treatment and means of reimbursement identified); 3 (prevention as predominant clinical focus) |

| Major barriers to research career (top five reasons in order), % | Difficulty obtaining funding (64) | Difficulty obtaining funding (64) |

| Lower compensation (57) | Lower compensation (61) | |

| Lack of interest (57) | Lower quality of life (38) | |

| Lack of research training (40) | Too little mentorship (35) | |

| Lower quality of life (34) | Lack of research training (34) | |

| Lack of interest (16) | ||

| Additional barriers to cancer prevention research (five reasons in order), % | Few mentors (85) | Unclear career model (55) |

| Lack of training opportunities for clinicians (70) | Unclear economic runway (37) | |

| Unclear career model (68) | Lack of training opportunities for clinicians (35) | |

| Unclear economic runway (66) | Few mentors (30) | |

| Not important or relative to treatment (47) | Not important or relative to treatment (12) | |

| Portion of training program dedicated to risk, screening, or prevention, % | ≤ 10 (86% of respondents) | NA |

| Most frequent type of instruction | Didactic by prevention experts and online courses | NA |

| Preparedness in prevention compared with cancer treatment | Not very well (87% of respondents) | NA |

| What area of prevention research most likely, % | NA | Clinical or translational trials (48) |

| Epidemiology or database (31) | ||

| Laboratory (5) | ||

| Unsure (38) | ||

| Helpful training materials | Online modules on specific topics within general area of prevention (73% answered helpful or very helpful) | |

| Online modules dealing with risk, screening, or prevention for specific organ sites (75% answered helpful or very helpful) | ||

| Top ways ASCO could help, % | Toolkit for training program directors (77) | |

| Special career sessions (70) | ||

| More prevention education sessions at ASCO annual meeting (66) | ||

| Sponsor-mentored postdoctoral fellowship in cancer prevention (52) |

Abbreviations: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; NA, not applicable; NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Top barriers to an academic career in general were perceived difficulty in obtaining funding for research (64%) and lower compensation (61%). Perceived lower quality of life because of competing pressures, too little mentorship, and lack of research training were also listed as barriers by 34% to 38% of fellow respondents. Lack of interest in a research career was a major factor for only 16%. Top additional barriers to a career with a focus in cancer prevention were lack of clarity as to what a career in cancer prevention might encompass (55%), economic uncertainty (37%), and lack of mentorship (35%). Lack of importance relative to cancer treatment was listed as a factor by only 12%. Two thirds of fellows would consider a career with a focus in cancer prevention but generally only if combined with cancer treatment. Only 15% of those considering an academic career thought it was likely or very likely that they would consider cancer prevention as a focus of their research. Most considering an academic career reported a mentor had influence on their decision making. Clinical and translational trials were the top type of prevention research for those interested, followed by epidemiologic or database studies, with only 5% likely to select primarily laboratory-based prevention research. Many respondents reported they were unsure of what type of prevention research they might pursue.

DISCUSSION AND WORK GROUP RECOMMENDATIONS

Given the concerns expressed in the survey regarding adequacy of prevention training, reimbursement, and research opportunities, we examined current curriculum requirements for prevention, available postfellowship prevention educational resources, reimbursement climate for clinical prevention services, and funding mechanisms available to young researchers.

Prevention in Curriculum of Oncology Training Programs

Cancer prevention activities include cancer risk assessment and genetic counseling, behavioral modification to prevent new primary cancers or recurrence, prescribing and managing cancer prevention therapies, and developing methods to reduce long-term adverse effects of cancer treatment without increasing risk of recurrence. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has published requirements and curricula for all accredited training programs.12-14 For pediatric oncology, there is no formal curriculum mandating training in prevention of second malignancies or other long-term complications of treatment. Most pediatric programs use the Children's Oncology Group long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers,15 appropriate for the routine long-term management and assessment of asymptomatic childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors. For general surgical oncology, none of the competencies included in the ACGME program requirements specifically address cancer prevention.16 Prophylactic or surgical prevention interventions are not discussed, nor is management of acute and long-term effects associated with surgery that cancer survivors may experience. ACGME educational requirements for fellows training in adult hematology and oncology include a provision that they demonstrate medical knowledge and practice competence in prevention and survivorship, but details are lacking as to how training programs should comply.17 Furthermore, the only prevention and survivorship competency requirements explicitly identified in the ACGME policies include genetic testing for high-risk individuals and cancer screening. Exposure to prevention and survivorship during medical oncology training is variable.18 Except in larger training programs, education on these topics may be relegated to didactic lectures or on-line materials. Both ASCO and the American Society of Hematology have recently provided more granular recommendations on curricular milestones for oncology trainees in the United States and Canada,19 including expectations for cancer prevention and survivorship knowledge (Table 2). For individuals interested in pursuing a career in cancer prevention research, dual degrees (MD and PhD, MD and MPH, or MD and Masters of Clinical Research) may also be helpful.

Table 2.

ASCO and ASH Hematology-Medical Oncology Curricular Milestones Specific to Cancer Prevention and Survivorship (ASCO 2014)

| Competency Category | Milestone | Specific Training Requirement to Be Met for Unsupervised Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Patient care | Demonstrates ability to effectively recognize and promote cancer prevention and control strategies and survivorship | Consistently promotes proven cancer prevention or control strategies and individual needs of cancer survivors and participates in cancer control and prevention strategies aimed at disparate populations |

| Medical knowledge | Demonstrates knowledge of, and indications for, genetic, genomic, molecular, and laboratory tests related to hematologic and oncologic disorders | Consistently demonstrates knowledge about molecular pathways; appropriate cytogenetic or molecular tests; and clinical genetic syndromes; including diagnosis and management of inherited or acquired common, rare, and complex disorders |

| Systems-based practice | Demonstrates ability to use and access information that incorporates cost awareness and risk–benefit analysis in patient or population-based care | Incorporates cost-awareness principles into standard clinical judgments and decision making, including use of screening tests |

Abbreviations: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; ASH, American Society of Hematology.

The ASCO Cancer Prevention Workforce Pipeline Work Group recommends that ASCO join efforts to collaborate with ACGME and the American Board of Internal Medicine to increase emphasis on competency in prevention and survivorship in their training program accreditation requirements, in-service examinations, and maintenance of certification requirements. Other potential possibilities include supplemental awards to cancer center core grants to support pre- and postdoctoral training in cancer prevention, which could cover a range of activities including partial tuition coverage for Masters of Public Health training.

Mentorship

In general, interest in academic medicine wanes as trainees progress through their residency.20 The reasons for this are not completely clear, but financial considerations and debt play major roles.21 Active mentorship, engagement in research, and publication of this research during the training period can increase the likelihood of retention of a trainee in academic medicine.21 Increasingly, it is thought that a network of mentors, with skills individualized to the mentees' needs, may be more critical than a single mentor.22 Through earlier exposure to cancer prevention principles and career opportunities (eg, during medical school), formative impressions may be made that may follow trainees into cancer prevention career development paths, not only within oncology but also in surgery, primary care, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics.

The work group recommends continued liaison with the ASCO Professional Development Committee to offer written materials and meet-the-experts sessions in the fellows lounge at the annual meeting. An easily updated mentor list should also be incorporated into an online toolkit for training directors. Inclusion of cancer prevention career paths with ASCO medical student initiatives is recommended. Reinstitution of the NCI R25T award mechanism, which provides funding for mentors, partial stipends for trainees, funds for trainee research, and travel funds, would likely generate both trainee and mentor interest. Finally, ASCO and/or NCI initiatives to fund short trainee externships with established cancer prevention researchers to learn skill sets specific to their research areas of interest should be encouraged.

NCI Federal Funding for Young Researchers

The NCI offers training and career development grants. The career development award program (ie, K grants) are intended for individual clinical investigators building toward an independent research career and are of particular interest to young investigators, including those potentially interested in cancer prevention research.23 An evaluation of the K award portfolio (K01, K07, K08, K11, K22, K23, and K25) was undertaken by the NCI in 2012 primarily to assess whether and how K awards affected awardees' future research careers.13 More than half of K awardees were MDs, with medical oncology and hematology in the top three medical specialties. K awardees were more likely to pursue an academic career, with more subsequent grants and publications than nonawardees. However, only 14% of institutions received the majority (60%) of awarded K grants.13 Thus, NCI-funded career development awards may not be accessible to the broad base of trainees potentially interested in cancer prevention research careers.

The work group recommends a more granular review of the NCI funding portfolio to assess how much research funding is currently being provided to clinical trainees with an interest in cancer prevention and can work with the NCI to identify special funding opportunities or incentives such as loan repayment. Awareness of prevention-focused funding opportunities can be increased by listing them in the training program director toolkit and by having clinical research mentors available at the annual meeting in the fellows lounge. Grant-writing resources, prevention research methodology, and updated lists of mentors available for long and short externships in cancer prevention should also be included in the toolkit.

Increasing Prevention and Survivorship Competencies for Practicing Oncologists

Although there are oncologists who have as their primary focus risk assessment and genetic counseling, they are relatively rare. More often, in the current workforce, oncologists combine cancer treatment with cancer risk and genetic counseling practices. These individuals often specialize in a single organ or multiple closely related organ sites and have had special postdoctoral training in cancer genetics and risk counseling. Continuing medical education offerings in this area should be ongoing and include the spectrum of services involved in risk assessment and counseling, genetic testing, and postassessment decision making regarding surveillance and preventive therapy. ASCO has developed education on cancer prevention topics, both as part of its ASCO University learning modules library and as part of the ASCO annual meeting education and scientific sessions, available online at the ASCO University Web site. In addition, ASCO has authored position papers on prevention topics of high interest, such as obesity.24 ASCO has also released a cancer prevention and screening maintenance of certification module as well as a tobacco cessation maintenance of certification module. In 2014, ASCO University released a highly successful multimodule cancer genetics program, designed specifically to increase providers' knowledge in the area of hereditary cancer genetics. In addition to educational opportunities, cancer program standards should include prevention measures relevant to all practicing oncologists. Sources for information include National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines, ASCO's Quality Oncology Practice Initiative, and the Commission on Cancer Hospital Accreditation Program.25-27

The work group recommends that ASCO expand and maintain ASCO-sponsored education in cancer prevention, including an online portfolio of general and organ site–specific prevention topics, and that prevention topics be fully integrated into treatment and survivorship education. The work group will work with the education committee to ensure prevention educational sessions and topics of high interest are cross referenced with the prevention track and appropriate disease-specific tracks, an effort that was initiated during the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting planning process. ASCO should also work with other organizations to ensure that prevention is integrated into early career professional development, including research and grant-writing training workshops such as the American Association for Clinical Research/ASCO Vail Methods Workshop.

Financial Implications of Prevention Activities in Clinical Practice

From a coverage and reimbursement perspective, the Affordable Care Act has broadly outlined a group of core services called essential health benefits, which must be offered by individual and group insurers. These benefits include some cancer preventive services (colon and cervical cancer screening, mammography, and human papilloma virus vaccination) that are to be provided with no copay.28 However, the law is unclear on whether coverage for follow-up diagnostic tests or coverage without deductibles or copays must be included and gives states leeway in interpretation and implementation, leading to patchwork coverage.29 Medicaid beneficiary data suggest that even these simple preventive screenings are unlikely to be routinely adopted unless reimbursement for office visits is increased commensurate with the time it takes for providers to explain the necessity for these procedures to their patients30-32 or arrange a follow-up procedure after a positive screen.33 There is uneven commercial coverage for risk and genetic counseling and genetic testing. Counseling time, if covered, is often poorly reimbursed.34 The complexity of risk and genetic counseling, poor reimbursement for counseling time, and relative scarcity of qualified counselors too often result in lack of referral for testing.35 A recent study from Michigan reported only half of women with breast cancer age < 50 years received genetic counseling and testing, citing lack of referral or insurance issues as the primary reasons for this shortcoming.34 The advent of gene panel testing, with the increase in mutations of uncertain significance and deleterious mutations that are nonactionable or for which action is uncertain, will only serve to exacerbate the manpower problem.35,36

The work group recommends that the ASCO Cancer Prevention and Cancer Survivorship Committees continue to identify strategies to increase counseling for prevention and survivorship interventions as well as increase uptake of the interventions covered as essential health benefits. Furthermore, oncologists should be reimbursed for providing the counseling or intervention, if they choose to do so.

In summary, surveys of medical oncology fellows conducted on behalf of the ASCO Cancer Prevention Workforce Pipeline Work Group suggest interest in prevention as a focus for careers both in academic medicine and clinical practice, but little likelihood of uptake because of concerns regarding adequate training resources, mentorship, and reimbursement. Fellows favored a clinical or research career in which they could perform treatment as well as prevention activities. Lack of clinicians as prevention role models was a significant deterrent. General barriers to a career in academic medicine were perceived difficulty in grant funding and reduced quality of life because of competing pressures. Training directors did not think their fellows were well trained in prevention relative to treatment. They were in favor of toolkits and integrated prevention sessions at ASCO.

The ASCO Cancer Prevention Workforce Pipeline Work Group plans several approaches, including: 1) assessment of the NCI cancer prevention funding portfolio for clinicians and efforts to increase funding opportunities; 2) reinstatement of the NCI R25T award mechanism to increase multidisciplinary mentorship and research training in cancer prevention; 3) continued offerings of ASCO-sponsored education in cancer prevention; 4) development of a cancer prevention toolkit for training program directors; 5) collaboration with ACGME and the American Board of Internal Medicine to increase emphasis on competency in prevention and survivorship in their training program accreditation requirements, in-service examinations, and maintenance of certification requirements; 6) efforts to improve awareness of early career professional development opportunities in prevention, including ASCO- and/or NCI-supported short externships with mentors in cancer prevention; and 7) efforts to increase the scope of prevention counseling and services covered under essential health benefits (Table 3). Survivorship in pediatric cancer and transitional care for adolescent and young adults should also be addressed separately.

Table 3.

ASCO Cancer Prevention Research, Education, and Policy Recommendations

| Recommendation |

|---|

| Optimize research funding by conducting assessment of NCI prevention research funding and increasing awareness of prevention-focused funding opportunities |

| Develop training and education resources, with priority given to creating ASCO-sponsored education in cancer prevention, developing training program director toolkit, increasing awareness of cancer prevention careers at ASCO annual meeting, and working to incorporate competencies in prevention and survivorship into ACGME training program requirements |

| Advocate for increased reimbursement by more fully including prevention reimbursement in ASCO policy efforts |

Abbreviations: ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Appendix

Table A1.

Institutions of Program Director Survey Respondents

| Institutions Represented |

|---|

| Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX |

| Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA |

| Beth Israel, New York, NY |

| Carter Medical Center, Miami, FL |

| Columbia University, New York, NY |

| Georgetown University, Washington, DC |

| Gundersen Health Systems, La Crosse, WI |

| Howard University Hospital, Washington, DC |

| John H. Stroger Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, IL |

| Marshall University School of Medicine, Huntington, WV |

| Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN |

| MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX |

| Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC |

| Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY |

| NCC–Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD |

| NSLIJ/Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, NY |

| Ochsner Health System, Jefferson, LA |

| Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR |

| Oklahoma University Health Sciences Health Center, Oklahoma City, OK |

| Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute, Hershey, PA |

| Providence Health and Services, Renton, WA |

| San Antonio Military Medical Center, San Antonio, TX |

| Scripps Clinic, San Diego, CA |

| Staten Island University Hospital, New York, NY |

| University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, MA |

| University of California Davis, Davis, CA |

| University of California Irvine, Irvine, CA |

| University of Chicago, Chicago, IL |

| University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH |

| University of Florida, Gainesville, FL |

| University of Louisville, Louisville, KY |

| University of Northern Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC |

| University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada |

| University of Penn Medical Center/University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA |

| University of South Florida and Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL |

| University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN |

| University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT |

| University of Vermont, Burlington, VT |

| University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA |

| Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN |

| Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC |

| West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV |

| Yale University, New Haven, CT |

Abbreviations: NCC, National Capital Consortium; NSLIJ, North Shore–Long Island Jewish.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: 2318 Mill Rd, Suite 800, Alexandria, VA 22314; e-mail: cancerpolicy@asco.org.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Administrative support: Courtney A. Tyne

Provision of study materials or patients: Carol J. Fabian, Frank L. Meyskens Jr

Collection and assembly of data: Courtney A. Tyne

Data analysis and interpretation: Carol J. Fabian, Frank L. Meyskens Jr, Dean F. Bajorin, Thomas J. George Jr, Joanne M. Jeter, Courtney A. Tyne, William N. William Jr

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Barriers to a Career Focus in Cancer Prevention: A Report and Initial Recommendations From the American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer Prevention Workforce Pipeline Work Group

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Carol J. Fabian

Research Funding: DSM (Inst), Lignan Research (Inst)

Frank L. Meyskens Jr

Stock or Other Ownership: Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals (co-founder and member of the Scientific Review Board. No fiduciary obligations.)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patents (Inst; several patents related to chemoprevention usage of eflornithine and polyamine metabolism in a number of malignant and nonmalignant conditions. Jointly held by institution and Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals

Dean F. Bajorin

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck, Genentech/Roche

Thomas J. George Jr

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer

Research Funding: Bayer (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Joanne M. Jeter

Honoraria: Genentech

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech

Shakila Khan

No relationship to disclose

Courtney A. Tyne

Employment: Feinstein Kean Healthcare

William N. William Jr

Research Funding: Astellas Boehringer Ingelheim

REFERENCES

- 1.Zon RT, Goss E, Vogel VG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: The role of the oncologist in cancer prevention and risk assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:986–993. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganz PA, Kwan L, Somerfield MR, et al. The role of prevention in oncology practice: Results from a 2004 survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2948–2957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umar A, Dunn BK, Greenwald P. Future directions in cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:835–848. doi: 10.1038/nrc3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G. Future supply and demand of oncologists: Challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang S, Cameron C. Addressing the future burden of cancer and its impact on the oncology workforce: Where is cancer prevention and control? J Canc Educ. 2012;27(suppl):S118–S127. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0342-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang S, Collie CL. The future of cancer prevention: will our workforce be ready? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2348–2351. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang S. In memoriam: An appreciation for the NCI R25T cancer education and career development program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1133–1136. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang W, Williams JH, Hogan PF, et al. Projected supply of and demand for oncologists and radiation oncologists through 2025: An aging, better-insured population will result in shortage. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:39–45. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:678–686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanafelt TD, Raymond M, Kosty M, et al. Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1127–1135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson DE, Faupel-Badger J, Phillips S, et al. Future directions for postdoctoral training in cancer prevention: Insights from a panel of experts. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:679–683. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in pediatric hematology-oncology. http://acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013-PR-FAQ-PIF/327_hematology_oncology_peds_07012013.pdf.

- 13.Mason JL, Lei M, Faupel-Badger JM, et al. Outcome evaluation of the National Cancer Institute career development awards program. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:9–17. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0444-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Commission on Cancer. Cancer program standards 2012: Ensuring patient-centered care. https://www.facs.org/∼/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx.

- 15.Children's Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers (version 3.0) www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/ltfuguidelines.pdf. [PubMed]

- 16.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in complex general surgical oncology. www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/446_complex_general_surgical_oncology_2016_1-YR.pdf.

- 17.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in hematology and medical oncology (internal medicine) https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013-PR-FAQ-PIF/155_hematology_oncology_int_med_07132013.pdf.

- 18.Halpern MT, Viswanathan M, Evans TS, et al. Models of cancer survivorship care: Overview and summary of current evidence. J Oncol Pract. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001403. [epub ahead of print on September 9, 2014] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Hematology-oncology curricular milestones: A collaboration of the American Society of Hematology and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. www.asco.org/sites/www.asco.org/files/ho_curricular_milestones_4.18.14_final.pdf.

- 20.Straus SE, Straus C, Tzanetos K. International campaign to revitalise academic medicine: Career choice in academic medicine—Systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1222–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borges NJ, Navarro AM, Grover A, et al. How, when, and why do physicians choose careers in academic medicine? A literature review. Acad Med. 2010;85:680–686. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d29cb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, et al. Mentor networks in academic medicine: Moving beyond a dyadic conception of mentoring for junior faculty researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88:488–496. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318285d302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute. Funding opportunities for training by award type. www.cancer.gov/researchandfunding/cancertraining/funding/awardtype.

- 24.Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3568–3574. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denlinger CS, Carlson RW, Are M, et al. Survivorship: Introduction and definition—Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:34–45. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Quality Oncology Practice Initiative, measures summary, fall 2014: Manual submission. http://qopi.asco.org/documents/Fall_2014_Measures_Summary-Manual_Submission_(2).pdf.

- 27.McNiff K. The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative: Assessing and improving care within the medical oncology practice. J Oncol Pract. 2006;2:26–30. doi: 10.1200/jop.2006.2.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang SQ, Polite BN. Achieving a deeper understanding of the implemented provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014;2014:e472–e477. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haeder SF. Balancing adequacy and affordability? Essential health benefits under the Affordable Care Act. Health Policy. 2014;118:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halpern MT, Romaire MA, Haber SG, et al. Impact of state-specific Medicaid reimbursement and eligibility policies on receipt of cancer screening. Cancer. 2014;120:3016–3024. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams WW, Lu PJ, Saraiya M, et al. Factors associated with human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult women in the United States. Vaccine. 2013;31:2937–2946. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown ML, Klabunde CN, Cronin KA, et al. Challenges in meeting Healthy People 2020 objectives for cancer-related preventive services, National Health Interview Survey, 2008 and 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E29. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green BB, Coronado GD, Devoe JE, et al. Navigating the murky waters of colorectal cancer screening and health reform. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:982–986. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson B, McLosky J, Wasilevich E, et al. Barriers and facilitators for utilization of genetic counseling and risk assessment services in young female breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;2012:298745. doi: 10.1155/2012/298745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.George R, Kovak K, Cox SL. Aligning policy to promote cascade genetic screening for prevention and early diagnosis of heritable diseases. J Genet Couns. 2015;24:388–399. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxwell KN, Wubbenhorst B, D'Andrea K, et al. Prevalence of mutations in a panel of breast cancer susceptibility genes in BRCA1/2-negative patients with early-onset breast cancer. Genet Med. 2015;17:630–638. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]