Abstract

Patient: Female, 64

Final Diagnosis: Segmental absence of intestinal musculature

Symptoms: Abdominal discomfort

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Colectomy

Specialty: Diagnostics, Laboratory

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Segmental absence of intestinal musculature is a well described entity in premature infants. It presents with peritonitis, bowel perforation, and obstruction. The diagnosis is based on pathologic observation of absence of intestinal musculature. Researchers hypothesized that this entity is a result of a vascular accident during embryogenesis. However, segmental absence of intestinal musculature is no longer limited to the pediatric population. Recently, a few cases have been described in adults with and without significant vascular diseases. This change in the age of the affected population with segmental absence of intestinal musculature makes the understanding of the pathogenesis of this entity even more challenging.

Case Report:

Here, we report a case of segmental absence of intestinal musculature in a 64-year-old female. The patient presented to the emergency room with sudden onset of abdominal pain and signs of peritonitis. Abdominal computed tomography showed free air in the abdomen. Laparotomy was performed, and a perforation involving the descending colon was identified. Left hemicolectomy was performed. Pathologic examination of the resected colon showed segmental absence of intestinal musculature.

Conclusions:

Although the pathologic diagnosis of segmental absence of intestinal musculature is straightforward, the assumption that this condition is limited to the pediatric population is a major player in overlooking this diagnosis in adults. Pathologists should be aware that this condition can present in adults and is segmental. Gross and microscopic examination of perforated intestine is required to reach the correct diagnosis. To our knowledge, twelve cases of this entity have been described in adults. Here we present the thirteenth case of segmental absence of intestinal musculature in an adult, and we discuss the clinical and pathologic findings of this entity as well as its pathogenesis.

MeSH Keywords: Congenital Abnormalities, Intestinal Perforation, Muscle Development

Background

Segmental absence of intestinal musculature (SAIM) is a well described entity in the pediatric population, especially premature infants. It is diagnosed based on pathologic examination of the bowel. The presentation of this condition in adults is very rare. To the best of our knowledge, twelve cases of SAIM have been described in adults. Here, we report the thirteenth case of SAIM in a 64-year-old female, and we discuss the clinical and pathologic findings of SAIM in adults.

Case Report

The patient was a 64-year-old female with a known history of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hiatal hernia, chronic abdominal pain with constipation, and family history of osteogenesis imperfecta. The patient had no history of cardiovascular diseases and no history of major surgeries other than caesarian section. Multiple radiological studies were conducted to investigate the abdominal pain, and no abnormalities were detected. She then presented to the emergency room with sudden onset of severe abdominal pain. The pain started two weeks prior, and it was associated with fever and absence of bowel movement for five days. The physical examination was significant for abdominal distention, tenderness, rigidity, and absent bowel sound. An abdominal computed tomography scan showed free air in the abdomen. Laparotomy was then performed and showed descending colon perforation. Left hemicolectomy with colo-colonic anastomosis was performed, and the resected bowel was sent to the pathology lab for further examination.

Gross examination

The hemicolectomy specimen consisted of a 34.5 cm (in length) ×2.0–3.2 cm (in diameter) segment of colon with stapled ends and up to a 4.5 cm portion of attached peri-colonic fat. The colon had a 2.7 cm area of perforation 5.0 cm from the closest stapled margin. Two segments of the colon adjacent to the perforation site had thin wall with loss of the muscular layer (Figure 1). The peri-colonic fat had two small lymph nodes. Sampling of the perforation, colonic wall adjacent to perforation, stapled margins, and lymph nodes was performed. The sampled tissue was then embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Figure 1.

Gross picture of colonic segment with loss of muscularis propria.

Microscopic examination

The microscopic examination revealed acute inflammation and colonic perforation through a muscular wall defect. There was abrupt loss of muscularis propria in the bowel segment with grossly thinned wall. No thrombosed blood vessel, loss of nerves, or loss of mucosa, submucosa, or serosa was seen. The colonic tissues at the stapled margins were unremarkable. The lymph nodes were reactive (Figures 2–5).

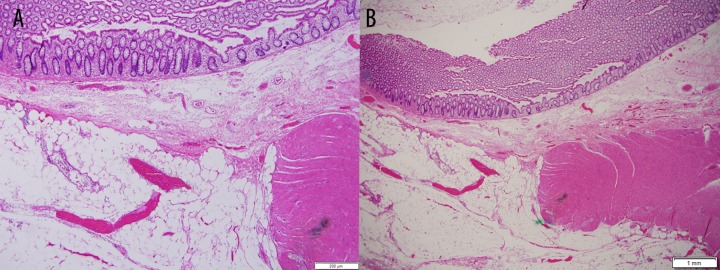

Figure 2.

(A, B) Full colonic wall section adjacent to perforation showing abrupt loss of muscularis propria with preservation of mucosa.

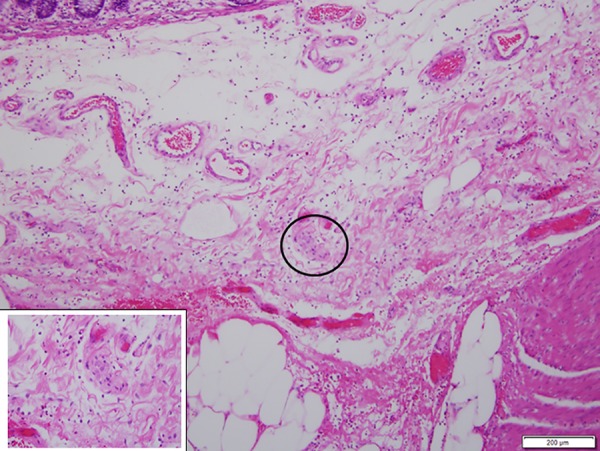

Figure 3.

Intact nerve in the area of loss of muscularis propria.

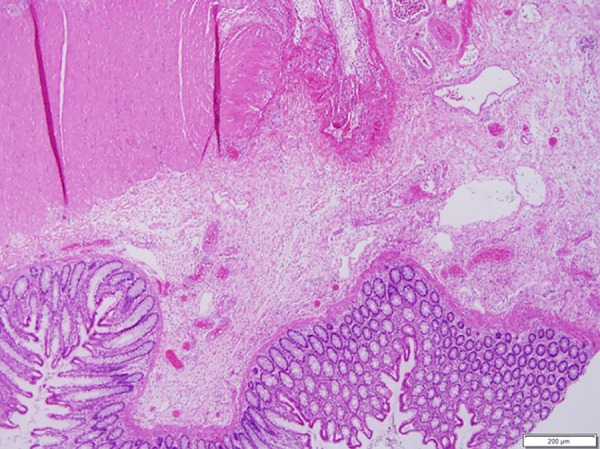

Figure 4.

Section through the perforation site showing acute inflammation and abrupt loss of muscularis propria.

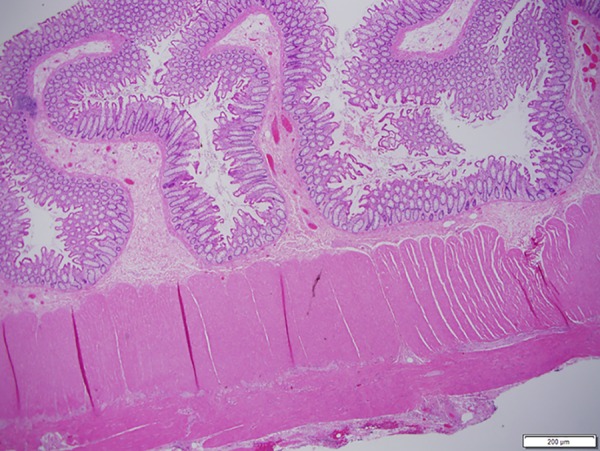

Figure 5.

Uninvolved bowel segment with preserved muscularis propria.

Follow-up

The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged ten days postoperatively. However, she presented four months later with multiple intraabdominal abscesses and severe inflammation of the small bowel secondary to anastomotic leak. Irrigation and drainage of the abscesses were performed. The anastomotic leak was repaired, and segments of the small and large bowel were resected. Pathologic examination of the resected bowel showed acute and chronic inflammation. No loss of intestinal musculature was noted.

Discussion

In 1997, Darcha et al. described the first case of SAIM in adults in a 64-year-old female, who had iatrogenic sigmoid colon perforation during endoscopic removal of a rectal polyp [1]. A study published by Tamai et al. described seven cases of SAIM in a retrospective study involving patients who presented with spontaneous intestinal perforation [2]. The true incidence of SAIM is not known, as this entity is segmental and the diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion. The disease affects men and women equally. The age range of SAIM in adult is 28–64 years. However, the majority of cases are described in older adults. Clinically, SAIM presents with a sudden episode of intestinal perforation or obstruction. Associated clinical symptoms include severe abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distention. Perforation can be single or multiple. SAIM is described more frequently in the large intestine than in the small intestine. In adults, no cases have been described in stomach, duodenum, or rectum [1–6]. A summary of the reported cases of SAIM in adults is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of cases of SAIM in adults.

| Case # | Year, Author | Age (y) | Sex | Clinical presentation | Intraoperative findings | Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1997, Darcha et al. [1] | 64 | F | Iatrogenic colonic perforation during laparoscopic polypectomy | Sigmoid colon perforation | SAIM |

| 2 | 1998, Tawfiq et al. [3] | 34 | M | Nausea and abdominal pain Past history: Three episodes of small bowel obstruction Three vessels coronary artery bypass graft Thyroglossal duct excision Laryngeal polypectomy |

Obstruction of the jejunum and adhesions | SAIM No inflammation, vascular abnormalities, or perforation |

| 3 | 2009, Aldalati et al. [4] | Middle age | M | Pancreatic mass and pancreatitis | Dilated segment of jejunum, multiple diverticula, and fibrotic peritoneal nodule | SAIM Lymphangioma The peritoneal nodule turned out to be a thrombosed blood vessel No inflammation or perforation No pancreatic malignancy |

| 4 | 2010, Procházka et al. [5] | 28 | F | Sepsis and abdominal pain five days post appendectomy | Two perforations involving the ascending colon | SAIM No acute appendicitis |

| 5 | 2013, Tamai et al. [2] | ?* | F | Shock Mucus and blood in stool Patient had histories of hypertension, uterine cancer treated with radiotherapy, foot ulcer, and urinary tract infection |

SAIM Loss of nerves in the area of SAIM No signs of inflammation No vasculitis No ischemic changes |

|

| 6 | 2013, Tamai et al. [2] | ?* | ?* | Nausea, vomiting, and fever Patient had history of gastric cancer treated with surgery |

Bowel perforation | SAIM Loss of nerves in the area of SAIM No signs of inflammation No vasculitis No ischemic changes |

| 7 | 2013, Tamai et al. [2] | ?* | ?* | Abdominal distention, abdominal pain, and vomiting three days post-rectal resection for rectal cancer | Bowel perforation | SAIM Loss of nerves in the area of SAIM No signs of inflammation No vasculitis No ischemic changes |

| 8 | 2013, Tamai et al. [2] | ?* | F | Patient had history of chronic renal failure and hypertension | Multiple bowel perforations | SAIM Loss of nerves in the area of SAIM No signs of inflammation No vasculitis No ischemic changes |

| 9 | 2013, Tamai et al. [2] | ?* | ?* | Sudden severe abdominal pain and chronic history of melena and fever Patient was on chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma at the time of presentation |

Bowel perforation | SAIM Loss of nerves in the area of SAIM No signs of inflammation No vasculitis No ischemic changes |

| 10 | 2013, Tamai, et al. [2] | ?* | ?* | NA | Bowel perforation | SAIM Loss of nerves in the area of SAIM No signs of inflammation No vasculitis No ischemic changes |

| 11 | 2013, Tamai et al. [2] | ?* | ?* | Abdominal pain Patient had history of angina pectoris, dementia, and constipation |

Bowel perforation | SAIM Loss of nerves in the area of SAIM No signs of inflammation No vasculitis No ischemic changes |

| 12 | 2015, Nandedkar et al. [6] | 48 | M | Abdominal pain and vomiting twenty days post-resection of gangrenous bowel | Small bowel perforation | SAIM Gangrenous small bowel with perforation, peritonitis, and thrombosed mesenteric artery |

| 13 | 2016, Current case; Nawar and Sawyer | 64 | F | Severe abdominal pain and tenderness Patient had significant history of chronic abdominal pain and constipation Family history of osteogenesis imperfecta |

Descending colon perforation | SAIM Perforation Focal serositis Acute inflammation No thrombosed blood vessels No loss of ganglion cells or nerves |

Tamai et al. described seven cases of SAIM in four females and three males with the age range of 44–89 years. The authors did not specify the age or the sex of the individual patients.

The pathogenesis of SAIM is not yet understood. Theoretically, the disease can be congenital or acquired [7–9]. Congenital SAIM probably results from defects in embryogenesis. Proposed mechanisms include failure of regression of intestinal diverticula, or over-resorption of muscles during regression of the omphalomesenteric duct during embryogenesis [7]. Some researchers have suggested that SAIM results from transient ischemia secondary to vascular accident during embryogenesis, or secondary to transient intussusception [8]. The ischemia theory might help explain some of the acquired cases of SAIM in adults. Among adults with SAIM, 38% had hypertensive vascular diseases or history of bowel ischemia. Two of the reported cases had mesenteric vessel thrombosis, which was confirmed by microscopic pathology examination of mesentery [4,6]. However, the ischemia theory does not explain SAIM in adults with no vascular diseases. It also does not explain the preservation of the mucosa, which is more sensitive to ischemia than the muscularis propria.

On gross pathology examination, bowel segments with SAIM usually have a very thin, paper-like wall. Other gross features that might be associated with SAIM include perforation, ulceration, and diverticulosis. However, evaluation of bowel wall might be difficult in areas with perforation. Therefore, meticulous gross examination of bowel wall throughout the resected bowel segment is essential. Thinned wall might be easier to appreciate in segments adjacent to the perforated area. On microscopic examination, there will be a gradual or abrupt loss of the circular as well as the longitudinal layer of the muscularis propria. Approximately 50% of cases had loss of nerve plexuses in areas lacking muscularis propria. No loss of mucosa, submucosa, and serosa is associated with this condition. Inflammation and mesenteric vessel thrombosis are unusual [2–6].

Cases with SAIM are usually treated with surgical resection of the involved segment. As the incidence of the disease is not known, it is difficult to predict the prognosis of SAIM. However, no recurrences of intestinal perforation have been reported. Mortality was reported in only one case, in which the patient died two days postoperatively as a result of pulmonary edema [2].

In our case, the patient was a 64-year-old female, the same age and gender as the first reported case of SAIM in adults. The patient did not have evidence of vascular diseases. She presented with spontaneous intestinal perforation and had hemicolectomy. She developed postoperative complications secondary to anastomotic leak, but she did not have a recurrence of intestinal perforation. Microscopic examination of the descending colon showed SAIM and inflammation. No loss of nerves was noted, as opposed to 50% of the described cases.

The patient’s family history of osteogenesis imperfecta made us consider the possibility of undiagnosed underlying connective tissue disease that affected the vascular supply to intestinal musculature. However, we do not have evidence to support that possibility. The etiology of SAIM in this case remains mysterious.

Conclusions

In summary, segmental absence of muscularis propria is a rare entity with unknown etiology. The disease can present in pediatric as well as in adult populations. Thorough gross and microscopic examination of bowel segment is essential for diagnosis. Pathologists should be aware that this entity is segmental and keep a high index of suspicion when evaluating bowel resections, especially in cases of intestinal obstruction or perforation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Caryn Cooper for her technical assistance.

References:

- 1.Darcha C, Orliaguet T, Levrel O, et al. [Segmental absence of colonic muscularis propria. Report of a case in an adult] Ann Pathol. 1997;17(1):31–33. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamai M, Satoh M, Tsujimoto A. Segmental muscular defects of the intestine: A possible cause of spontaneous perforation of the bowel in adults. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(12):2643–50. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tawfik O, Newell B, Lee KR. Segmental absence of intestinal musculature in an adult. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(2):397–99. doi: 10.1023/a:1018879011103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldalati O, Phelan C, Ibrahim H. Segmental absence of intestinal musculature (SAIM): A case report in an adult. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.01.2009.1425. pii: bcr01.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Procházka V, Svoboda T, Soucek O, Kala Z. [Segmental absence of the muscularis propria layer in the colonic wall – a rare cause of colonic perforation during pregnancy] Rozhl Chir. 2010;89(11):679–81. [in Czech] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nandedkar SS, Malukani K, Patidar E, Nayak R. Segmental absence of intestinal musculature: A rare case report. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;5(3):222–24. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.165378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy DW, Qualman S, Besner GE. Absent intestinal musculature: Anatomic evidence of an embryonic origin of the lesion. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29(11):1476–78. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SF, Vacanti J, Kozakewich H. Segmental defect of the intestinal musculature of a newborn: Evidence of acquired pathogenesis. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(5):721–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dzieniecka M, Grzelak-Krzymianowska A, Kulig A. Segmental congenital defect of the intestinal musculature. Pol J Pathol. 2010;61(2):94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]