Abstract

The authors conducted two randomized clinical trials with ethnically diverse samples of college student drinkers in order to determine (a) the relative efficacy of two popular computerized interventions versus a more comprehensive motivational interview approach (BASICS) and (b) the mechanisms of change associated with these interventions. In Study 1, heavy drinking participants recruited from a student health center (N = 74, 59% women, 23% African American) were randomly assigned to receive BASICS or the Alcohol 101 CD-ROM program. BASICS was associated with greater post-session motivation to change and self-ideal and normative discrepancy relative to Alcohol 101, but there were no group differences in the primary drinking outcomes at 1-month follow-up. Pre to post session increases in motivation predicted lower follow-up drinking across both conditions. In Study 2, heavy drinking freshman recruited from a core university course (N = 133, 50% women, 30% African American) were randomly assigned to BASICS, a web-based feedback program (e-CHUG), or assessment-only. BASICS was associated with greater post-session self-ideal discrepancy than e-CHUG, but there were no differences in motivation or normative discrepancy. There was a significant treatment effect on typical weekly and heavy drinking, with participants in BASICS reporting significantly lower follow-up drinking relative to assessment only participants. In Study 2, change in the motivation or discrepancy did not predict drinking outcomes. Across both studies, African American students assigned to BASICS reported medium effect size reductions in drinking whereas African American students assigned to Alcohol 101, e-CHUG, or assessment did not reduce their drinking.

Keywords: brief alcohol intervention, motivation, discrepancy, computerized intervention, ethnicity, college alcohol use

Heavy drinking peaks during late adolescence and early adulthood and is especially common among 18–24 year-old young adults who attend college (Chen, Dufour, & Yi, 2004/2005). There are over nine million U.S. college students, approximately 45% of whom report engaging in heavy episodic drinking (defined as at least 5+ drinks in one sitting for men and 4+ drinks in one sitting for women) at least once in the preceding 2 weeks (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). Heavy drinking is associated with myriad health and social consequences including academic and legal difficulties, blackouts, injuries, and risky sexual behavior (Wechsler et al., 2002). In 2005 approximately 1,825 college students died from alcohol related injuries (Hingson et al.).

Interventions for College Student Drinking

Because college student drinkers generally report mild to moderate drinking problems and little motivation to change their drinking, they are an ideal population to target with brief motivational interventions (BMIs; Larimer, Cronce, Lee, & Kilmer, 2004/2005). BMIs typically incorporate the principles of Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002), a supportive and nonjudgmental therapeutic approach that is specifically designed to reduce the ambivalence that often accompanies health behavior change. Students have the opportunity to discuss their alcohol use during a brief counseling session, including both the benefits and consequences of drinking, and their potential interest in moderating consumption and avoiding related high-risk behaviors. BMIs typically include personalized normative feedback (PNF), which is printed information that contrasts the student’s drinking (based on their assessment report) with drinking patterns of other college students, an approach intended to correct the student’s overestimation of peer drinking and to increase motivation to change (Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004). The popular Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention program for College Students (BASICS; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999) combines MI and PNF and has strong empirical support relative to no-treatment control conditions and relative to interventions that provide only generic information about alcohol (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; Larimer & Cronce, 2007).

Computerized or internet-based alcohol interventions are rapidly being adopted on college campuses due to their low cost and convenience (Walters, Miller, & Chiauzzi, 2005). Two of the most popular computerized interventions are Alcohol 101 Plus (Century Council, 2003), an interactive CD-ROM program that takes participants through a “virtual college campus” but does not include PNF, and the Electronic Check Up to Go (e-CHUG; Walters, Vader, and Harris, 2007), a web-based program that includes PNF that is similar to what is included in BASICS. The evidence base for computerized interventions is growing but is not as compelling as it is for MI (Elliot, Carey, & Bolles, 2008). Several studies suggest that computerized interventions are associated with drinking reductions (Larimer et al., 2007; Walters et al., 2007), but the few studies that have directly compared computerized versus counselor-delivered BMIs have found results that are equivocal or suggest some advantage for counselor-delivered BMIs that include PNF (Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007; Carey, Henson, Carey, & Maisto, 2009; Donohue, Allen, Maurer, Ozols, & DeStefano, 2004; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, & Jouriles, 2009). Additionally, although one study has found an advantage for e-CHUG relative to a control condition (Walters et al. 2007), no studies have found an advantage for Alcohol 101 relative to a control condition. More research is needed to determine the relative efficacy of Alcohol 101, e-CHUG, and counselor-administered BMIs.

Mechanisms of action in brief motivational interventions

Investigating the underlying processes of behavior change is critical for the advancement of intervention research (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009). BMIs are presumed to generate behavior change by increasing normative and self-ideal discrepancy, and, in turn, motivation to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Normative discrepancy refers to the dissonance between the individual’s drinking and some external standard of comparison such as the drinking levels of peers. Self-ideal discrepancy refers to the dissonance between the individual’s drinking pattern and some internal standard of comparison, such as the individual’s personal values or goals. Few studies of BMI with college students have evaluated the putative mechanisms of intervention effects, and fewer have measured the immediate post-session impact of BMI on these mechanisms. Methodologically, it is ideal to evaluate the role of changes in a hypothesized causal mechanism of change (i.e., a mediator) in predicting subsequent behavior change using a temporal sequencing that does not confound the change in the mediator (e.g., motivation to change) with the change in the outcome (e.g., drinking quantity or frequency). If the mediator and the outcome variable are measured at the same follow-up point, then it is possible that change (or the absence of change) in the mediator is due in part to changes that occurred in the outcome variable, making it impossible to evaluate the role of the mediator in accounting for changes in the outcome variable (Borsari, Murphy, & Carey, 2009). For example, a student might increase her motivation to change following a BMI, make a reduction in drinking by the first follow-up assessment, and at that point report stable or even lower motivation to change relative to baseline as a result of the fact that her drinking is no longer causing problems. In this case, the stable level of the mediator (motivation) from baseline to follow-up would incorrectly suggest that it was unrelated to subsequent behavior change.

The few studies that have measured motivation immediately post-session have found that that BMIs are associated with post-session increases in motivation, but these studies have either failed to measure the association between change in motivation and subsequent drinking change (Barnett et al., 2007; LaBrie, Pedersen, Earlywine, & Olsena, 2006) or failed to find evidence that motivation predicted or mediated outcomes (Borsari et al., 2009; Collins, Carey, & Smyth, 2005). Even fewer studies have examined the role of discrepancy, despite its centrality to MI theory (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). There is evidence that normative discrepancy increases following a BMI (Neal & Carey, 2004), and that interventions specifically targeting normative and self-ideal discrepancy are associated with reductions in alcohol use and or problems (McNally & Palfai, 2003). However, one study found that although BMI increased discrepancy, change in discrepancy did not mediate the relationship between condition (BMI or control) and drinking outcomes (McNally, Palfai, & Kahler, 2005). Collins, Carey, and Sliwinski (2002) found similar results with a mailed PNF intervention. Given that enhancing discrepancy and motivation are the key proximal goals of BMIs, more research is needed to investigate the extent to which various BMIs impact these mechanisms, and the role of these mechanisms in accounting for subsequent drinking outcomes.

Brief motivational interventions with ethnic minority students

Although in general African American students drink less than Caucasian students (Chen et al., 2004/2005), the percentage of African American students reporting recent heavy drinking increased from 16.7% in 1992 to 21.7% in 2002 (Wechsler et al., 2002). In addition to the numerous health and social/legal consequences associated with excessive alcohol use, such use may be particularly detrimental to African Americans’ academic success and the long-term benefits that such success often entails. Over 50% of African American students who begin at 4-year colleges fail to earn a bachelors degree (U.S. Department of Education, 2008), and research has shown that heavy drinking is negatively associated with studying practices among African American students (dePyssler, Williams, & Windle, 2005). Two studies (LaBrie, Feres, Kenney, & Lac, 2009; Walters et al., 2009) found no differences in response to BMIs in Caucasian versus ethnic minority college students (primarily Hispanic and Asian American students), but no study has examined response to BMIs in African American college students. To our knowledge only one controlled trial of BMIs for college drinking included a sample that was greater than 15% African American (16%; Ingersoll et al., 2005); that study included only women and found drinking reductions but did not examine outcomes by ethnicity.

Study Purpose

We conducted two randomized clinical trials with ethnically diverse samples of college students in order to address several understudied questions regarding BMIs for college drinking, including: a) the relative efficacy of counselor-delivered BMIs similar to BASICS versus two popular computerized interventions in terms of both student preferences, impact on BMI proximal mechanisms (discrepancy and motivation, measured immediately post-session), and 1-month follow-up drinking outcomes; b) the relations between change in BMI mechanisms and subsequent change in drinking; and c) the efficacy of BMIs with African American college students. Study 1 compared a BASICS session to the Alcohol 101 program, and Study 2 compared a BASICS session to the e-CHUG program and to an assessment-only control condition. We hypothesized greater efficacy across all outcomes for BASICS. We also hypothesized that changes in motivation and normative discrepancy would be associated with subsequent change in drinking.

General Methods Common to Studies 1 and 2

Participants

Participants in both studies were students from a large metropolitan public university in the southern United States. Across both studies, students were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years old and reported one or more heavy drinking episodes (≥5/4 drinks on one occasion for a man/woman) in the past month. Because we were interested in recruiting an ethnically diverse sample, and research has shown that minority students drink less than Caucasian students (Chen et al., 2004/2005), but may also begin to experience problems at lower levels of drinking (Welte & Barnes, 1987), we used a lower eligibility threshold for minority students (1 or more past month heavy drinking episode) than for Caucasian students (2 or more past-month heavy episodes) and stratified our randomization by ethnic minority status.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board. Participants completed the baseline measures during an individual laboratory-based assessment appointment and were then randomly assigned to a condition using a random number table that was stratified by gender and ethnicity. The clinician who performed the intervention also completed the baseline assessment but was not aware of the condition assignment until the completion of the assessment.

Post-session assessments

All participants who completed an intervention completed a questionnaire immediately following the intervention that assessed their evaluation of the session, motivation to change, and normative and self-ideal discrepancy. The motivation and discrepancy items were also administered during the baseline assessment. Participants in the assessment-only condition (Study 2) did not complete additional post-session measures.

Follow-up assessments

A research assistant who was blind to the intervention condition conducted the 1-month follow-up assessments. Participants were paid $25 for completing this assessment, which included all drinking, motivation, and discrepancy measures.

Clinician training and supervision

Clinicians were eight clinical or counseling psychology doctoral students who completed over 20 hours of training in MI that included directed readings, MI training DVDs, and supervised role-plays. Clinicians received weekly supervision (including review of session tapes) by a psychologist with extensive experience with college drinking and motivational interventions (J.G.M., M.E.M., or M.P.M.).

Measures

Session ratings

Participants were asked five questions to assess their reactions to the session (Murphy et al., 2001). They rated how interesting and personally relevant they found the session and provided an overall rating of the session on a scale from 1 (Totally bad, boring) to 10 (Excellent, it was great). Additionally, participants rated on a scale from 1 (not at all effective) to 10 (very effective) how effective they believed the session would be at modifying a) their drinking patterns and b) the drinking patterns of other college students.

Alcohol-related discrepancy

Normative and self-ideal discrepancy was measured using the Discrepancy Ratings Questionnaire (Neal & Carey, 2004). Normative discrepancy items assessed students’ perceptions of how their a) frequency of drinking, b) typical quantity of drinking, c) maximum quantity of drinking, d) binge drinking, and e) drinking-related problems compare to the average college student (e.g., How frequently do you drink compared to the average college student?). Participants responded on a scale from 1 (Substantially less) to 7 (Substantially more) with high scores indicating more normative discrepancy. Self-ideal discrepancy items assessed how alcohol was affecting their a) relationships with friends, b) relationships with family, c) school-work, d) health, and e) appearance. Participants responded on a scale from 1 (Substantially helping) to 7 (Substantially interfering) with higher ratings indicating more discrepancy. The mean scores for the five normative and five self-ideal discrepancy items were used in the analyses (αs = .91 & .67, respectively).

Motivation to change drinking

The Readiness Ladder (Biener & Abrams, 1991) was used to assess motivation to change drinking. This measure includes an image of a ladder and requires that participants circle the rung that most closely corresponded to their thoughts of changing their drinking. The rungs ranged from 0 (no thought of changing) to 10 (taking action to change). This single item measure has been found to be sensitive to changes in motivation in other brief alcohol intervention studies (Barnett et al., 2007).

Alcohol use

Total drinks per week were measured using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). This measure asks participants to estimate the total number of standard drinks that they consumed each day during a typical week in the past month. The DDQ has been used frequently with college students and is a reliable measure that is highly correlated with self-monitored drinking reports (Kivlahan, Marlatt, Fromme, Coppel, & Williams, 1990). To assess frequency of heavy drinking, participants were asked how many times in the past month they had engaged in a heavy drinking episode (≥5/4 drinks for a man/woman) in a 2-hour period of time. To assess overall subjective change in drinking, participants were asked if their drinking a) increased, b) decreased, or c) stayed the same during the past month (Murphy et al., 2001, 2004).

Data Analysis Plan

All variables were checked for outliers and deviations from normality prior to analysis. Outliers greater than 3.29 SDs above the mean (p < .001) were re-coded following the recommendations of Tabachnick and Fidell (2006). Square root transformations were used to correct for significant skewness to the drinking variables. Untransformed variables are presented in the tables for interpretational clarity. Between-subjects effect sizes (db) were calculated by dividing the difference between the adjusted follow-up means by the pooled weighted standard deviations (Bien et al., 1993). Within-subject effect sizes (dw) were calculated by dividing the difference between the baseline and follow-up (or post session) value by the pooled standard deviation while accounting for the correlation between the pre and post values due to the dependency in the data. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used for our primary post-session outcomes (discrepancy and motivation), and follow-up drinking outcomes (drinks per week and past-month frequency of heavy drinking), with the baseline value as the covariate, and gender and treatment condition as between-subjects factors. We included gender as a between subjects factor because several studies have found that college women are more responsive to brief alcohol interventions than college men (Carey et al., 2007; Murphy et al., 2004). Multiple regression was used to investigate the relations between change in the post-session mechanism variables and subsequent change in drinking. Ethnicity effects were evaluated by replicating the primary drinking ANCOVAs with ethnicity and treatment condition as between-subjects factors. We compared African American and Caucasian students in these analyses and excluded other ethnic minority students because we did not have a sufficient number of students from other ethnicities and we did not think it would be meaningful to group students from different ethnicities into a single ethnic minority group. Because the small number of African American students (approximately 10 per treatment condition) resulted in low power for the ANCOVAs, we were primarily interested in determining the drinking change effect sizes for African American participants.

Study 1

Methods Particular to Study 1

Participants

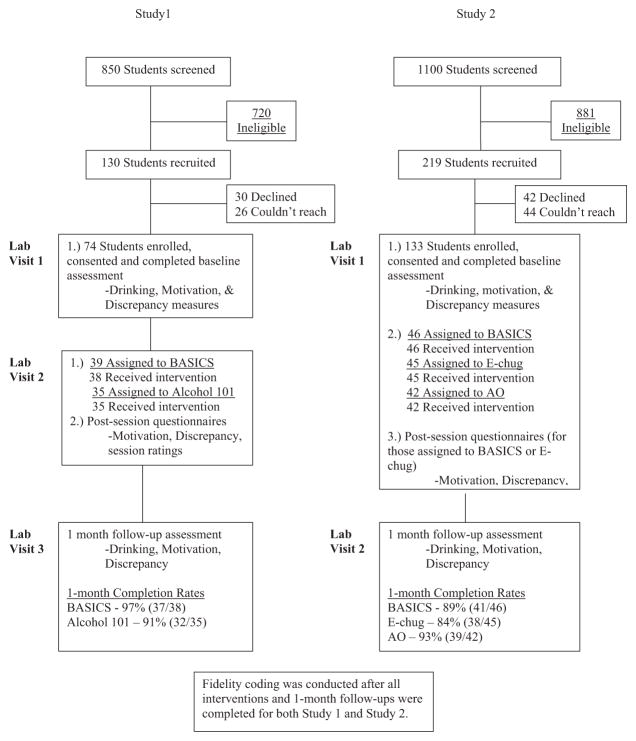

Undergraduate students who presented at the university student health clinic and expressed interested in participating in a paid health behavior study were screened (by completing a brief written screener in the waiting room, or if a research assistant was not present, a subsequent phone screen) and invited to participate in the intervention trial if they met the criteria described above. One-hundred and thirty students were eligible and 74 (57%) agreed to participate (see Figure 1). The self-reported ethnicity of the sample was: 73% Caucasian, 23% African-American, 2.7% Hispanic/Latino, 2.7 % Asian, and 1.4% American Indian. Participants were allowed to indicate multiple ethnicities. The sample included 30 men and 44 women. The mean number of past month heavy drinking episodes was 3.16 (SD = 3.8). Participants reported drinking an average of 16.46 standard drinks during a typical week in the past month (SD = 13.28). The average age was 21.2 years (SD = 2). The sample included 12.2% first-year students, 28.4% second-year students, 31.1% third-year students, and 27.7% fourth-year students. There were no significant demographic or drinking differences between the 56 students who declined to participate and the 74 participants who agreed to participate.

Figure 1.

Flow of Participants Through Each Stage of Study 1 and Study 2.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to either BASICS (n = 39) or the Alcohol 101 Plus CD-ROM program (n = 35). Interventions were conducted in private lab space in the Psychology Department. Across both conditions, session length was 50–60 minutes. Participants completed the intervention within 1 week of the assessment and received $50 for completing both sessions (approximately three hours total over two appointments). The BASICS session consisted of five major parts: (a) an introductory discussion that emphasized confidentiality, harm reduction, and the student’s autonomy/responsibility to make decisions about the information provided in the session; (b) a discussion of the student’s college and career goals, and how they might relate to decisions about substance use; (c) a decisional balance exercise; (d) personalized feedback; and (e) summary, goal setting, and, if the student was interested, reviewing protective behavioral strategies. Personalized feedback elements included: (a) a comparison of the student’s perception of how much college students drink and actual student norms; (b) a comparison of the student’s alcohol use vs. gender-based national norms; (c) an estimated blood alcohol content (BAC) chart depicting the student’s past month peak BAC and the BAC associated with a more moderate drinking episode (i.e., a DDQ entry in which the participant drank under the binge threshold and/or spaced their drinking such that their estimated BAC was less than .081); (d) alcohol-related consequences and risk behavior, including drinking and driving and alcohol-related risky sexual behavior; (e) a comparison of the time spent drinking with time on other activities (e.g. studying, exercising); (f) money spent on alcohol; and (g) calories consumed from alcoholic drinks. Clinicians used MI principles and methods to encourage the student to engage in discussion about the feedback. Students who were interested in changing their drinking were encouraged to set specific goals.

In the Alcohol 101 condition, students used the Alcohol 101 Plus CD-ROM program (Century Council, 2003). This program features a virtual campus that students are required to navigate. They may visit different “buildings” such as the library, the dormitories, or the quad. In each location the student may view information, watch a video depicting potential negative outcomes associated with drinking (e.g. a sexual assault or a drinking and driving arrest), or take a quiz about alcohol and its effects on the body. There is also a virtual bar on the campus in which students may enter their gender, weight, drink type, and speed of consumption and receive feedback on their BAC. Students were instructed to spend at least 50 minutes navigating the virtual campus. At the end of the session, the research assistant used a feature of the program to record the components the participant had seen in order to ensure adequate exposure to the intervention. Thus, in addition to the difference in modality (computer vs. counselor administered), Alcohol 101 does not include the personalized feedback (other than BAC feedback), decisional balance exercise, discussion of the relations between drinking and college/career goals, or goal setting included in the BASICS session; both interventions include similar informational content, harm reduction suggestions, and general material intended to highlight the potential risks associated with drinking (though the material highlighting risk is more personalized in the BASICS session). Additional details of the procedures and measures are reported in the General Methods section.

Results

There were no significant group differences in drinks per week, heavy drinking, motivation, or discrepancy at baseline. One participant who completed a baseline assessment and was assigned to BASICS did not attend the intervention session, but all other randomized participants completed the intervention. One-month follow-up rates were 95% (n = 69), with no between-group differences in rates (see Figure 1). There were no demographic or baseline drinking differences between completers and non-completers.

Evaluation of internal validity

Approximately 25% of the BASICS sessions (n = 10) were randomly selected and reviewed by one of two masters-level clinicians who were not involved with the project but were trained in motivational interviewing. At least one session for each clinician was reviewed. Each of the components on the protocol was rated as a 1 “Did it poorly or didn’t do it but should have,” 2 “Meets Expectations,” or 3 “Above Expectations” (Barnett et al., 2007). A score of 2 or higher indicated that the intervention component was delivered in a manner that was consistent with the protocol in terms of both content and motivational interviewing style. A rating of 3 indicated an especially skillful handling of a session component, (e.g., handling resistance nondefensively, asking open ended questions or reflections that were especially thoughtful and lead to increased discrepancy or problem recognition, and using advanced MI skills such as complex reflections). For the 26 main components of the intervention protocol the average rating was 1.98 (SD =.26, Mdn = 2.00), with 92.5% of the components rated as meeting or exceeding expectations. Competence on 10 specific MI skills (developing discrepancy, rolling with resistance, expressing empathy, etc.; Barnett et al., 2007) was also rated using the same scale described above. The average rating across the MI competence items was 2.04 (SD =.33, Mdn = 2.00), with 95% of these items being rated as a 2 or 3. These ratings indicate that the clinicians in the study consistently administered the intervention components and adhered to an MI style.

Session evaluation ratings

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed a main effect for group on the five evaluation items completed by participants immediately after the interventions, F(5, 65) = 5.87, p < .001, η2 =.311. Mean ratings for both interventions were high (M = 8.47 for BASICS and 7.10 for Alcohol 101), but participants rated the BASICS condition significantly more favorably than Alcohol 101 on each item (all univariate p values < .01; dbs = 0.57–1.16). There was also a main effect for gender, F(5, 65) = 2.83, p = .022, η2 = .179, but no gender × treatment interaction. Women rated both interventions more favorably than did men.

Post-session drinking-related discrepancy

Baseline and post-session discrepancy means and within condition effect sizes (dw) are shown in Table 1. There was a main effect for treatment on self-ideal, F(1, 68) = 8.59, p =.005, η2 =.112, and normative, F(1, 67) = 14.55, p < .001, η2 = .178), discrepancy. At post-session participants in the BASICS condition reported greater self-ideal and normative discrepancy scores than those in Alcohol 101 (after controlling for baseline values). Pre-post effect sizes were medium-to-large in the BASICS condition, while pre-post changes were small in the Alcohol 101 condition. There was also a main effect for gender on normative discrepancy, F(1, 67) = 5.57, p =.021, η2 =.077, with men reporting higher normative discrepancy than women (after controlling for baseline values). There were no significant treatment × gender interactions.

Table 1.

Pre-Post Means (SD) and Effect Sizes, Study 1

| Variable | Baseline BASICS | Follow-up BASICS | d | Baseline Alc. 101 | Follow-up Alc. 101 | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normative discrepancy | 3.71 (1.34) | 4.72 (1.38) | 1.03 | 3.54 (1.32) | 3.65 (1.27) | 0.15 |

| Self-ideal discrepancy | 4.17 (0.29) | 4.39 (0.54) | 0.53 | 4.30 (0.42) | 4.25 (0.29) | −0.19 |

| Motivation to change | 3.74 (2.60) | 4.87 (3.09) | 0.44 | 4.43 (3.00) | 4.29 (3.04) | −0.07 |

| Drinks per week | 15.20 (9.58) | 11.42 (10.01) | 0.47 | 17.14 (16.45) | 14.00 (13.98) | 0.34 |

| Heavy drinking | 3.03 (3.43) | 2.00 (2.43) | 0.36 | 2.87 (3.99) | 2.97 (3.95) | 0.03 |

Note. Sample sizes for post-session follow-up variables (discrepancy and motivation to change) were: BASICS, n = 38 and Alcohol 101, n = 35. Sample sizes for one-month follow-up variables (drinks per week and heavy drinking) were: BASICS, n = 37, Alcohol 101, n = 32. Negative effect sizes indicate a counter-therapeutic pre-post change (i.e., reductions in discrepancy or motivation, or increases in drinking).

Post-session motivation to change drinking

There was a main effect for treatment condition on post-session motivation to change drinking, F(1, 68) = 3.83, p = .05, η2 =.053. Participants in BASICS reported greater post-session motivation to change than participants assigned to Alcohol 101 (see Table 1). There was no effect for gender and no treatment × gender interaction.

One-month follow-up drinking outcomes

Separate ANCOVAs were conducted on the two primary drinking outcome variables: drinks per week and past month frequency of heavy drinking. Participants in the BASICS condition reported larger effect size reductions in weekly drinking, and heavy drinking (dws =.47 & .36, respectively), than participants in Alcohol 101 (dws =.34 & .03; see Table 1), but the follow-up differences controlling for baseline values were not statistically significant, F(1, 64) =.43 and F(1, 63) =.56, ps > .1. There was a main effect for gender on heavy drinking, F(1, 63) = 6.79, p = .01, η2 = .10, with women (across both conditions) reporting less drinking than men at follow-up after controlling for baseline drinking differences. There were, however, no gender × treatment interactions. Finally, in assessing overall subjective changes in drinking, a greater percentage of BASICS participants (68%), than Alcohol 101 participants (56%), reported a decrease in drinking (η2 (1, N = 69) = 6.47, p =.039).2

Change in BMI mechanisms predicting change in drinking

These analyses sought to evaluate whether change in the theoretically based mechanisms of action of BMIs (motivation, normative discrepancy, and self-ideal discrepancy), measured immediately post session, predicted subsequent drinking. Although the absence of group differences in the primary drinking outcomes precluded formal tests of mediation, we conducted a series of hierarchical regression analyses to determine whether the difference between the baseline and post-session BMI mechanism value (change score) predicted follow-up drinking after controlling for baseline drinking, the baseline mechanism value, and treatment condition. To minimize the number of regressions, we used a composite variable for follow-up drinking (the average standard score of weekly and heavy drinking). Change in motivation accounted for unique variance in follow-up drinking (β = .22, ΔR2 = .04, t = 2.52, p = .01). Greater post-session increases in motivation to change were associated with less drinking at follow-up. Neither normative nor self-ideal discrepancy change scores predicted follow-up drinking. We evaluated additional models that included gender as a covariate, but the results were identical.

Ethnicity moderation analyses

Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes for drinking variables among African American and Caucasian students are presented in Table 2. Although the treatment by ethnicity interactions were not significant, African American students showed larger effect size reductions in the BASICS condition than in the Alcohol 101 condition for both heavy drinking and drinks per week. Among Caucasian students, a similar trend of greater reductions for participants assigned to BASICS was evident for heavy drinking but not for drinks per week. There was also a significant overall effect for ethnicity on heavy drinking, F(1, 63) = 6.58, p = .013, η2 = .10. After controlling for differences in baseline drinking level, African-American students reported less drinking than Caucasian students at follow-up. There were no significant treatment by ethnicity interactions for the post-session discrepancy or motivation outcomes.

Table 2.

African American vs. Caucasian Pre-Post Means (SD) and Effect Sizes on Drinking Outcomes, Study 1

| Variable | Baseline BASICS | Follow-up BASICS | d | Baseline Alc. 101 | Follow-up Alc. 101 | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Americans | ||||||

| Drinks per week | 7.89 (6.05) | 3.56 (2.13) | 0.71 | 5.14 (2.67) | 5.00 (5.32) | 0.03 |

| Heavy drinking | 1.22 (2.22) | 0.33 (0.50) | 0.42 | 0.50 (0.84) | 0.67 (1.63) | −0.11 |

|

| ||||||

| Caucasians | ||||||

| Drinks per week | 18.02 (9.81) | 14.26 (10.58) | 0.42 | 20.37 (17.90) | 16.87 (15.27) | 0.35 |

| Heavy drinking | 3.76 (3.73) | 2.72 (2.64) | 0.33 | 3.48 (4.34) | 3.74 (4.27) | −0.08 |

Note. Sample sizes for African Americans were: BASICS, n = 9, Alcohol 101, n = 7. Sample sizes for Caucasians were: BASICS, n = 29, Alcohol 101, n = 23. Negative effect sizes indicate a counter-therapeutic pre-post change (i.e., increases in drinking).

Study 2

Methods Particular to Study 2

Participants

Undergraduate students enrolled in university-wide introductory classes were invited to participate if they met the criteria described above on a brief classroom screening survey. Two-hundred nineteen students were eligible and 133 (61%) agreed to participate (See Figure 1). The reported ethnicity of the sample was 65.4% Caucasian, 30.1% African-American, 2.3% Hispanic/Latino, 2.3% Native American, .8% Hawaiian and .8% Asian. The sample included 67 men and 66 women. The mean number of past month heavy drinking episodes was 3.32 (SD = 3.42). Participants reported drinking an average of 15.84 standard drinks during a typical week in the past month (SD = 13.57). The average age was 18.6 years (SD = 1.2) and 98% of participants were first-year students (2% were 2nd year students). There were no significant demographic differences between the 86 students who declined to participate and the 133 students who agreed to participate, though students who agreed to participate reported slightly more past-month heavy drinking episodes, t(215) = 2.26, p = .03.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to (a) BASICS (n = 46), (b) e-CHUG (n = 45), or (c) assessment-only (n = 42). Participants in the e-CHUG and BASICS conditions completed the intervention immediately after the assessment. Participants in the assessment-only condition did not receive an intervention after the assessment. Participants received $40 for completing the baseline phase of the study. The BASICS condition was identical to that described in Study 1. e-CHUG (Electronic Check-Up to Go) is an interactive web-based program that requires students to complete a brief drinking assessment (6–7 minutes) that is used to instantly generate personalized feedback in the following areas: (a) quantity and frequency of drinking, (b) comparison of drinking with student norms, (c) peak BAC, (d) tolerance level, (e) alcohol-related consequences, (f) money spent on alcohol, (g) calories consumed from alcohol, and (h) family risk score. Students were asked to review the feedback for at least 30 minutes and completed a brief comprehension check to ensure adequate exposure to the intervention. The BASICS and CHUG interventions included nearly identical personalized feedback and harm reduction strategy elements. In addition to differing in treatment modality (computerized vs. counselor administered), BASICS included three additional elements: discussion of the relations between the student’s career goals and drinking, decisional balance, and goal setting. Additional details of the procedures and measures are reported in the General Methods section.

Results

There were no significant group differences in drinks per week, heavy drinking, motivation, or discrepancy at baseline, and all participants assigned to an intervention completed their intervention. The 1-month follow-up rate was 89% (n = 118), with no differences among the conditions (see Figure 1). There was a significant difference in drinks per week between participants who completed the follow-up and the 15 non-completers, t(131) = 2.09, p = .047, with non-completers reporting slightly more drinking than completers at baseline (non-completers, M = 15.51, SD = 14.05; completers, M = 18.43, SD = 8.9). There were no other demographic or drinking differences between completers and non-completers.

Evaluation of internal validity

Procedures for evaluating internal validity were identical to Study 1. Across the 26 components of the intervention the average independent competency/fidelity rating was 2.00 (SD = .21, Mdn = 2.00), with 96.6% of the components rated as meeting or exceeding expectations. Competency ratings on the 10 specific MI skills the average rating was 2.02 (SD = .32, Mdn = 2.00), with 94.2% of these items were rated as a 2 or 3. These ratings indicate that the clinicians in the study consistently administered the intervention and adhered to MI style.

Session evaluation ratings

A MANOVA revealed a main effect for group on the evaluation items, F(5, 83) = 5.09, p < .001, η2 = .235. Mean ratings for both interventions were high (mean of all 5 items = 8.37 for MI and 7.2 for e-CHUG), but participants rated BASICS significantly more favorably than e-CHUG on each item (all univariate p values < .01, dbs = .49–1.02). There was no effect for gender and no treatment × gender interaction.

Post-session drinking-related discrepancy

Participants in BASICS and e-CHUG reported similar post-session values in normative discrepancy (after controlling for baseline values), F(1, 83) = 1.41, p = .239, η2 = .017, but participants in the BASICS condition reported greater self-ideal discrepancy than those in e-CHUG, F(1, 86) = 4.89, p = .03, η2 = .054. Pre-post effect sizes were medium to large in both conditions (see Table 3). There were no effects for gender and no treatment × gender interactions.

Table 3.

Pre-Post Means (SD) and Effect Sizes on Drinking Outcomes, Study 2

| Variable | Baseline BASICS | Follow-up BASICS | d | Baseline e-CHUG | Follow-up e-CHUG | d | Baseline AO | Follow-up AO | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normative discrepancy | 3.44 (1.36) | 4.28 (1.34) | 0.75 | 3.66 (1.32) | 4.24 (1.44) | 0.71 | — | — | — |

| Self-ideal discrepancy | 4.11 (0.54) | 4.33 (0.57) | 0.33 | 4.23 (0.38) | 4.20 (0.30) | −0.12 | — | — | — |

| Motivation to change | 2.18 (2.25) | 4.74 (3.56) | 0.86 | 2.77 (2.81) | 3.95 (3.05) | 0.31 | — | — | — |

| Drinks per week | 14.61(14.62) | 9.43 (11.84) | 0.57 | 16.57 (16.30) | 11.93 (11.33) | 0.42 | 15.44 (11.02) | 14.99 (11.34) | 0.05 |

| Heavy drinking | 3.20 (3.72) | 1.85 (2.83) | 0.46 | 2.99 (3.40) | 2.03 (2.23) | 0.39 | 3.58 (3.31) | 3.61 (3.26) | −0.01 |

Note. Sample sizes for post-session follow-up variables (discrepancy and motivation to change) were: BASICS, n = 46 and e-CHUG, n = 45. Sample sizes for one-month follow-up variables (drinks per week and heavy drinking) were: BASICS, n = 41, e-CHUG, n = 38, assessment-only, n = 39. Negative effect sizes indicate a counter-therapeutic pre-post change (i.e., reductions in discrepancy or motivation, or increases in drinking).

Post-session motivation to change drinking

There was no treatment effect on motivation to change drinking, although participants in the BASICS condition showed larger effect size increases in motivation to change following the session (see Table 3). There was no effect for gender and no treatment × gender interaction.

One-month follow-up drinking outcomes

There were significant treatment effects for typical weekly drinking, F(2, 111) = 3.72, p = .027, η2 = .063 and frequency of heavy drinking, F(2, 108) = 5.19, p =.007, η2 = .088. Follow-up contrasts indicated that BASICS showed a significant advantage relative to assessment only on each of these drinking outcomes (ps = .008 & .002, dbs = .42 & .52, respectively). BASICS showed a non-significant trend level advantage over e-CHUG on heavy drinking (p = .069, db = .35), but there were no other significant contrast effects (including no significant differences between e-CHUG and assessment only). Participants in BASICS and e-CHUG showed medium effect size reductions in drinking whereas participants in the assessment condition showed no change (see Table 3). There were also main effects for gender (ps < .05), but no gender x treatment interactions, on weekly and heavy drinking. Across all conditions, women reported less weekly and heavy drinking than men at follow-up, even after controlling for baseline differences. Finally, in assessing overall subjective changes in drinking a greater percentage of BASICS participants (68%) reported a decrease in drinking than e-CHUG (58%) and assessment-only participants (38%), η2(2, N = 118) = 11.12, p = .025.3

Change in BMI mechanisms predicting change in drinking

Analyses in this study were limited to participants who completed an intervention, as those in the assessment-only condition did not complete post-session measures. In this trial none of the BMI mechanism variables predicted change in drinking. Additionally, change in the mechanism variables did not mediate the trend level advantage of BASICS versus e-CHUG on heavy drinking. We evaluated additional models that included gender as a covariate, but the results were identical.

Ethnicity moderation analyses

There was a significant ethnicity effect on weekly drinking, F(1, 115) = 3.85, p = .05, η2 = .03; after controlling for baseline drinking, Caucasian students reported less drinking at follow-up than African American students. As can be seen in Table 4, however, the smaller treatment response among African American students relative to Caucasian students is primarily due to fact that African American students randomized to e-CHUG did not reduce their drinking while Caucasian students did (dws = .01 & .58). There was a non-significant trend level interaction between treatment and ethnicity on heavy drinking, F(1, 105) = 2.59, p = .08, η2 = .05. Again, Caucasian students randomized to e-CHUG reported larger effect size reductions than African American students (see Table 4). There were no significant treatment by ethnicity interactions for the post session self-ideal discrepancy or motivation outcomes. There was an interaction between treatment and ethnicity on normative discrepancy, F(1, 86) = 10.37, p = .002, η2 = .11. African American students assigned to MI reported greater post-session discrepancy than African American students assigned to e-CHUG, but Caucasian students reported similar post-session levels of discrepancy across MI and e-CHUG.

Table 4.

African American vs. Caucasian Pre-Post Means (SD) and Effect Sizes, Study 2

| Variable | Baseline BASICS | Follow-up BASICS | d | Baseline e-CHUG | Follow-up e-CHUG | d | Baseline AO | Follow-up AO | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Americans | |||||||||

| Drinks per week | 7.93 (11.45) | 4.36 (4.18) | 0.36 | 5.12 (4.97) | 5.15 (7.06) | −0.01 | 6.68 (4.41) | 6.00 (7.36) | 0.08 |

| Heavy drinking | 0.93 (0.10) | 0.64 (1.08) | 0.29 | 0.62 (1.04) | 1.00 (1.15) | −0.26 | 1.82 (3.22) | 1.09 (1.58) | 0.26 |

|

| |||||||||

| Caucasians | |||||||||

| Drinks per week | 18.08 (15.06) | 12.06 (13.64) | 0.64 | 21.88 (17.07) | 14.60 (11.04) | 0.58 | 19.87 (10.62) | 19.40 (10.59) | 0.06 |

| Heavy drinking | 4.42 (4.08) | 2.50 (3.27) | 0.54 | 4.02 (3.42) | 2.39 (2.35) | 0.78 | 4.28 (2.98) | 4.60 (3.03) | −0.09 |

Note. Sample sizes for African Americans were: BASICS, n = 14, e-CHUG, n = 13, assessment-only, n = 11. Sample sizes for Caucasians were: BASICS, n = 26, e-CHUG, n = 24, assessment-only, n = 26. Negative effect sizes indicate a counter-therapeutic pre-post change (i.e., increases in drinking).

Discussion

The results of these two randomized clinical trials with ethnically diverse samples of college drinkers provide detailed information on multiple domains of BMI outcomes for three popular BMIs (Alcohol 101, e-CHUG, and BASICS, which is a more comprehensive counselor administered motivational intervention), including: relative student preferences and relative impact on both proximal BMI mechanisms (discrepancy and motivation) and drinking outcomes. These trials also provide information on the efficacy of BMIs among African American students.

Post-Session Preference Ratings and BMI Mechanism Outcomes

Across both studies, participants rated BASICS more favorably than the comparison intervention on every measured domain. Although participants rated both Alcohol 101 and e-CHUG favorably (~ 7 on a 10 point scale), these results suggest that students may find more comprehensive, counselor-administered MI interventions such as BASICS more interesting, credible, and useful than these particular computerized interventions. This preference information may be relevant to universities’ efforts to market and increase participation in alcohol interventions.4

Across both studies, BASICS was associated with significant increases on all of the intended proximal outcomes: participants reported a greater recognition of the deleterious impact of drinking on important life domains (self-ideal discrepancy), greater perceptions that they were drinking more than other students (normative discrepancy), and greater motivation to change. E-CHUG, which also includes personalized normative feedback (PNF), was also associated with increases in normative discrepancy and motivation to change, but did not increase self-ideal discrepancy. Alcohol 101, which does not include PNF (other than BAC information) or any personalized discussion of drinking patterns or risk factors, did not increase discrepancy or motivation. The overall pattern of results suggests that BMIs are associated with changes in the predicted theoretically derived mechanisms of change that are specific to the content of the intervention.

Drinking Outcomes

In Study 1, although BASICS evidenced greater post-session increases in motivation and discrepancy, there were no significant differences between BASICS and Alcohol 101 on the primary drinking outcomes. Within group effect sizes were larger in BASICS versus Alcohol 101 (especially for heavy drinking), but the study was inadequately powered to detect these differences.5 There was a significant treatment effect on students’ overall report of change in drinking that favored BASICS.

The overall pattern of results in Study 2 provides qualified support for the superiority of BASICS in achieving short-term drinking reductions. BASICS, but not e-CHUG, was associated with significantly greater weekly and heavy drinking reductions relative to an assessment-only control group. Although there were no significant differences between BASICS and either of the computerized interventions on the two primary drinking variables, there was a trend level advantage for BASICS relative to e-CHUG on heavy drinking.

Across both studies within group effect sizes for weekly and heavy drinking in the BASICS conditions were moderate (.36–.57), similar to the e-CHUG effect sizes, and slightly larger than the Alcohol 101 effect sizes. The magnitude of the drinking reductions we observed for Alcohol 101 and e-CHUG (18 & 28% reduction in drinks per week, respectively) are similar to what has been observed in previous research (Carey et al., 2009; Barnett et al., 2007; Walters et al., 2007), with the exception that Alcohol 101 was not associated with any reduction in heavy drinking in the present study. BASICS was associated with a 25% reduction in weekly drinking in Study 1 and a 36% reduction in Study 2. Although some previous studies have observed both smaller (Barnett et al., 2007) and larger (Borsari & Carey, 2000) effects associated with BASICS, the drinking reductions we observed are generally in line with previous research (Carey et al., 2007). Interestingly, across both studies, exactly 68% of students assigned to BASICS reported an overall reduction in drinking, compared to 56–58% of students in the computer intervention conditions, and 38% of the Study 2 assessment-only control participants. This small yet statistically significant advantage for BASICS relative to Alcohol 101 and e-CHUG on this measure may suggest that BASICS is associated with subtle changes in drinking practices that might not be easily detected by standard drinking measures. Indeed, the goal setting discussions often involved idiosyncratic and subtle changes such as avoiding shots and drinking games, spacing drinks, and refraining from drinking on school nights that may nevertheless constitute a meaningful positive change for some students. It is also possible that the advantage for BASICS on this item is related to the fact that in-person interventions elicit a greater amount of commitment or social desirability from participants which might in turn lead to subjective appraisals of change that overestimate actual changes in drinking behavior.

There were several relevant gender differences. In Study 1, women rated both interventions more favorably than did men and reported greater decreases in heavy drinking. In Study 2, women reported slightly greater reductions in both weekly and heavy drinking than men. Across both studies the better outcomes among women were primarily restricted to the BASICS condition. Although numerous trials of BMIs with college drinkers have not found gender differences in treatment response (Marlatt et al., 1998; Larimer et al., 2007; Walters et al., 2009), these results are consistent with several previous studies indicating that college women show greater responses to BMIs (Murphy et al., 2004; Carey et al., 2009; Carey et al., 2007).

Relations Between Change in BMI Mechanisms and Change in Drinking

In the first trial, students who reported greater increases in motivation following the intervention (BASICS or Alcohol 101) reported greater subsequent drinking reductions. This outcome was not replicated in Study 2, and neither study found that change in normative or self-ideal discrepancy was associated with subsequent change in drinking. Thus, both BASICS and e-CHUG appear to impact the theoretically predicted variables, but, consistent with previous research, these proximal outcomes were not consistently associated with subsequent changes in drinking (Borsari et al., 2009; McNally et al., 2005). It is possible that cognitive mechanisms such as motivation and discrepancy might influence behavior in the days or weeks following the intervention but that their influence dissipates over time relative to more stable individual difference variables such as self-regulation and future time perspective (Carey, Henson, et al., 2007) or contextual variables such as the reinforcement value of alcohol relative to substance-free alternatives (MacKillop & Murphy, 2007; Murphy, Correia, Colby, & Vuchinich, 2005; Tucker, Roth, Vignolo, & Westfall, 2009).

Ethnic Differences in Response to BMI

These were the first trials to evaluate response to brief alcohol interventions among African American college students. Although these analyses should be interpreted cautiously due to the small number of African-American participants, these students responded well to BASICS, showing moderate effect size reductions in drinking. In contrast, African American participants assigned to Alcohol 101 or e-CHUG reported no drinking reductions, and although Caucasian students also showed greater effect size reductions in BASICS than Alcohol 101, they showed similar reductions across the BASICS and e-CHUG conditions. Because African American students reported lower drinking levels than Caucasian students, their drinking pattern may not have appeared as significant in the PNF included in e-CHUG, and they may not have identified with the more severe drinking scenarios presented in Alcohol 101. Indeed, in Study 2 African American students assigned to BASICS showed greater post-session increases in normative discrepancy compared to African American students assigned to e-CHUG. Although neither BASICS nor e-CHUG included drinking norms specific for African American students, BASICS is more personalized and interactive and the clinicians may have been able to elucidate ideographic drinking-related concerns that would not have surfaced in the computerized interventions. Future research should investigate the efficacy of computerized alcohol interventions that utilize culturally tailored norms and content.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this report are the inclusion of two studies that compared BASICS to popular computerized interventions on both proximal BMI mechanisms (discrepancy and motivation) and drinking, the inclusion of a substantial number of African American college students, and the inclusion of two active interventions and an assessment only control group in Study 2. Limitations of these studies include the relatively small sample sizes in both studies. The generalizability of Study 2 may have been further limited by the fact that eligible participants who enrolled in the study reported more recent heavy drinking than those who declined to participate. The brief follow-up period is also a limitation. Although the primary goal of this study was to evaluate the proximal responses to the interventions, one study found that MI showed an advantage over written PNF at a 15-month follow-up that was not evident at a 6-month follow-up (White et al., 2007), so it is possible that our results would be different with a longer follow-up period. Finally, because we used a lower heavy drinking inclusion criterion for minority students (≥ 1 past-month episode) than caucasian students (≥ 2 past-month episodes), it is possible that the observed ethnic differences were related to differences in drinking levels. This significant limitation was related to the time-frame of our study and available recruitment streams and should be addressed in future research.

Implications

The results of these studies may assist college health and student affairs personnel in making decisions about brief alcohol intervention programs. Relative to Alcohol 101 and e-CHUG, BASICS was preferred by students, increased both motivation and discrepancy, and (in Study 2) showed significant treatment effects on drinking relative to a no treatment control group. Thus, counselor-administered MI plus feedback may be an ideal frontline intervention for heavy drinking college students. These results are generally consistent with some previous research which has found slightly larger or more reliable drinking reductions associated with MI compared to interventions that deliver PNF without a counseling session (Carey et al., 2009; Monti et al., 2007; Walters et al., 2009; White et al., 2007, but see also Murphy et al., 2004); they extend previous research by indicating that African American students may respond better to MI versus these particular computerized interventions. Nevertheless, the advantages for BASICS relative to Alcohol 101 and e-CHUG were small and often non-significant, so in situations of limited resources these computerized interventions may be a good first option for many student drinkers, perhaps as part of a stepped care approach (Borsari, Tevyaw, Barnett, Kahler, & Monti, 2005). It is important to note that Alcohol 101 and e-CHUG differed from BASICS in both modality and content; BASICS included several components not included in the computerized interventions (e.g., decisional balance, goal setting). Alcohol 101 and e-CHUG also include fairly fixed content; it is possible that more interactive computerized interventions would more closely approximate in person programs like BASICS. Future research should compare computer and counselor administered interventions that have identical content, to determine whether any possible advantages for BASICS are related to intervention content versus modality. Interestingly, a recent study found no significant differences between a 10- versus a 50-minute counselor-administered MI among college drinkers (Kulesza, Apperson, Larimer, & Copeland, 2010). Finally, the relatively small treatment response among male students suggests that traditional BMIs are often inadequate for college men. Future research should attempt to develop additional intervention components that might increase the efficacy of BMIs (Murphy, Correia, & Barnett, 2007; Watt, Stewart, Birch, and Bernier, 2006).

These findings provide partial support for the general motivational theory underlying BMIs (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). BMIs that included PNF, whether counselor delivered or computerized, enhance normative discrepancy and motivation. BASICS, which includes more detailed feedback and discussion also enhances self-ideal discrepancy. Change in motivation predicted subsequent drinking change in Study 1 but not Study 2, and discrepancy did not predict drinking change in either study. Thus, BMIs may generate the theoretically predicted immediate response but that outcome may or may not translate into subsequent behavior change, and changes in drinking may occur in the absence of changes in motivation, findings which are inconsistent with the Transtheoretical Model (c.f., West, 2005). Future research should continue to investigate alternative constructs and measurement approaches for identifying mechanisms of change that are predictive of drinking outcomes (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research grants from the Alcohol Research Foundation (ABMRF; JGM), and the National Institutes of Health (AA016304 JGM).

Footnotes

BAC estimates were generated with the DUI Professional Blood Alcohol Analysis Program (www.duipro.com). The program plots estimated blood alcohol curves over time so that participants could see both their peak BAC and the duration of their elevated alcohol level on both a heavy and a more moderate drinking night. If a participant did not report any moderate drinking nights on the DDQ we generated a hypothetical moderate night (e.g., 3 drinks over 3 hours for a woman, 4 drinks over 4 hours for a man) to use as a contrast to their heavy drinking night.

Attrition effects. To examine the potential impact of missing follow-up data on our primary drinking outcomes we performed additional analyses using the last-observation carry forward method to replace data for the five participants who did not complete a follow-up. There were no meaningful differences in any of our study findings.

Attrition effects. Only one result was different when we replaced data for participants who did not complete the follow-up assessment. The contrast between BMI and e-CHUG on heavy drinking was significant (p = .037), with BMI participants reporting less follow-up heavy drinking than those in the e-CHUG condition.

We conducted exploratory analysis to determine whether or not post-session preference ratings were associated with subsequent change in drinking. In Study 1 participants’ rating of the likelihood that the session would result in a reduction in their drinking was negatively correlated with follow-up drinking. No other Study 1 or Study 2 session ratings were associated with outcomes.

A power analysis indicated that the observed differences in drinks per week between BASICS and Alcohol 101, and between BASICS and e-CHUG would require a sample size of close to 200 per condition to achieve statistical significance.

References

- Apodaca TR, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction. 2009;104:705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett N, Murphy J, Colby S, Monti P. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bien T, Miller W, Tonigan J. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction. 1993;88(3):315–335. doi: 10.111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari J, Carey K. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):728–733. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.68.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Carey KB. Readiness to change in brief motivational interventions: A requisite condition for drinking reductions? Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:232–235. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Tevyaw TO, Barnett NP, Kahler CW, Monti PM. Stepped care for mandated college students: A pilot study. American Journal of Addiction. 2007;16:131–137. doi: 10.1080/10550490601184498. 〈 http://ejournals.ebsco.com/direct.asp?ArticleID=452393C757929CAECBEA〉. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Which heavy drinking college students benefit from a brief motivational intervention? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:663–669. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Computer versus in-person intervention for students violating campus alcohol policy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:74–87. doi: 10.1037/a0014281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon L, Carey MP, DeMartini K. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Century Council. Alcohol 101 Plus (Interactive CD-ROM Program) 2003 Available at www.centurycouncil.org.

- Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi H. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the United States: Results from the 2001–2002 NESARC Survey. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004/2005;28:269–280. 〈 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh284/269-280.htm〉. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S, Carey K, Sliwinski M. Mailed personalized normative feedback as a brief interention for at-risk college drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:559–567. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.559. http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Carey KB, Smyth J. Relationships of linguistic and motivation variables with drinking outcomes following two mailed brief interventions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:526–535. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.526. 〈 http://www.jsad.com/jsad/downloadarticle/Relationships_of_Linguistic_and_Motivation_Variables_with_Drinking_Outcomes/1087.pdf〉. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dePyssler B, Williams V, Windle M. Alcohol consumption and positive study practices among African American college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2005;49:26–44. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_go2545/is_4_49/ai_n29236367/ [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students: A harm reduction approach. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue B, Allen D, Maurer A, Ozols J, DeStefano G. A controlled evaluation of two prevention programs in reducing alcohol use among college students at low and high risk for alcohol related problems. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2004;48:13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JC, Carey KB, Bolles JR. Computer-based interventions for college drinking: A qualitative review. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1999–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;(Supp 16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ingersoll K, Ceperich SD, Nettleman MD, Karanda K, Brocksen S, Johnson BA. Reducing alcohol-exposed pregnancy risk in college women: Initial outcomes of a clinical trial of a motivational intervention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan D, Marlatt G, Fromme K, Coppel D, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:805–810. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza M, Apperson M, Larimer M, Copeland A. Brief alcohol intervention for college drinkers: How brief is? Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:730–733. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Feres N, Shannon R, Kenney SR, Lac A. Family history of alcohol abuse moderates effectiveness of a group motivational enhancement intervention in college women. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Pedersen ER, Earleywine M, Olsena H. Reducing heavy drinking in college males with the decisional balance: Analyzing an element of motivational interviewing. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM, Lee CM, Kilmer JR. Brief interventions in college settings. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004/2005;28:94–104. 〈 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh28-2/94-104.htm〉. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, … Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG. A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, … Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results form a two-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP. Brief group alcohol interventions with college students: Examining motivational components. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33:159–176. doi: 10.2190/82CT-LRC5-AMTW-C090. 〈 http://ejournals.ebsco.com/direct.asp?ArticleID=JREHUB2RTU22WJP013L9〉. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, Kahler CW. Motivational interventions for heavy drinking college students: Examining the role of discrepancy-related psychological processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:78–87. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Woolard R. Motivational interviewing vs. feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102:1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J, Correia C, Colby S, Vuchinich R. Using behavioral theories of choice to predict drinking outcomes following a brief intervention. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;13:93–101. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Benson TA, Vuchinich RE, Deskins MM, Eakin D, Flood AM, … Torrealday O. A comparison of personalized feedback for college student drinkers delivered with and without a motivational interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:200–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.200. http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Correia CJ, Barnett NP. Behavioral economic approaches to reducing college student drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2573–2585. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Duchnick JJ, Vuchinich RE, Davison JW, Karg R, Olson AM, … Coffey TT. Relative efficacy of a brief motivational intervention for college student drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:373–379. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.15.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Carey KB. Developing discrepancy within self-regulation theory: Use of personalized normative feedback and personal strivings with heavy-drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:281–297. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Roth DL, Vignolo MJ, Westfall AO. A behavioral economic reward index predicts drinking resolutions: Moderation revisited and compared with other outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:219–228. doi: 10.1037/a0014968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Digest of Education Statistics 2007. Washington D.C: Author; 2008. Percentage distribution of enrollment and completion status of first-time postsecondary students starting during the 1995–96 academic year, by type of institution and other student characteristics: 2001. Table 318. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Miller E, Chiauzzi E. Wired for wellness: E-interventions for addressing college drinking. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR. A controlled trial of web-based feedback for heavy drinking college students. Prevention Science. 2007;8:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. 〈 http://ejournals.ebsco.com/direct.asp?ArticleID=49448C92EA1F905592A4〉. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Field CA, Jouriles EN. Dismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0014472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt M, Stewart S, Birch C, Bernier D. Brief CBT for high anxiety sensitivity decreases drinking problems, relief alcohol outcome expectancies, and conformity drinking motives: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15:683–695. doi: 10.1080/09638230600998938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee J, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson T, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. Retrieved from CINAHL with Full Text database. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte J, Barnes G. Youthful smoking: Patterns and relationships to alcohol and other drug use. Journal of Adolescence. 1987;10:327–340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(87)80015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R. Time for a change: Putting the transtheoretical (stages of change) model to rest. Addiction. 2005;100:1036–1039. doi: 10.1111/i.l360-0443.2005.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Mun EY, Pugh L, Morgan TJ. Long-term effects of brief substance use interventions for mandated college students: Sleeper effects of an in-person personal feedback intervention. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2007;31:1380–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00435.x. 〈 http://ejournals.ebsco.com/direct.asp?ArticleID=4EF4A8B7AED59EFCDAEA〉. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]