Abstract

Recent evidence indicates that cancer cells, even in the absence of a primary tumor, recirculate from established secondary lesions to further seed and colonize skeleton and soft-tissues, thus expanding metastatic dissemination and precipitating the clinical progression to terminal disease. Recently, we reported that breast cancer cells utilize the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 to exit the blood circulation and lodge to the skeleton of experimental animals. Now we show that CX3CR1 is overexpressed in human breast tumors and skeletal metastases. To assess the clinical potential of targeting CX3CR1 in breast cancer, a functional role of CX3CR1 in metastatic seeding and progression was first validated using a neutralizing antibody for this receptor and transcriptional suppression by CRISPR-interference (CRISPRi). Successively, we synthesized and characterized JMS-17-2, a potent and selective small-molecule antagonist of CX3CR1, which was used in pre-clinical animal models of seeding and established metastasis. Importantly, counteracting CX3CR1 activation impairs the lodging of Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) to the skeleton and soft-tissue organs and also negatively affects further growth of established metastases. Furthermore, nine genes were identified that were similarly altered by JMS-17-2 and CRISPRi and could sustain CX3CR1 pro-metastatic activity. In conclusion, these data support the drug development of CX3CR1 antagonists and promoting their clinical use will provide novel and effective tools to prevent or contain the progression of metastatic disease in breast cancer patients.

Implications

This works conclusively validates the instrumental role of CX3CR1 in the seeding of circulating cancer cells and is expected to pave the way for pairing novel inhibitors of this receptor with current standards of care for the treatment of breast cancer patients.

INTRODUCTION

Over ninety percent of breast cancer patients are diagnosed with localized or regionally confined tumors, which are successfully treated by a combination of surgery and radiation. However, up to thirty percent of patients will eventually present distant recurrences (1), which primarily affect bones, lungs, liver and brain, and remain incurable resulting in 40,000 annual deaths in the U.S. alone. Notably, the skeleton is the first site of recurrence in at least half of metastatic patients (2). These secondary bone tumors function as reservoirs of CTCs, which have been recently shown to cross-seed existing metastatic lesions as well as additional skeletal sites and soft-tissue organs (3, 4). By egressing the peripheral blood and invading the surrounding tissues CTCs convert into Disseminated Tumor Cells (DTCs) that initiate secondary tumors. Therefore, interfering with the conversion of CTCs into DTCs would have the potential to prevent metastatic disease or significantly delay its progression (5). Unfortunately, clinical strategies directed to block cancer cells from spreading are undeveloped, largely due to limited molecular targets and lack of suitable pharmacological or biological therapeutics. Studies from our laboratory and others indicate that the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 drives cancer cells to the skeleton (6,7), activates pro-survival signaling pathways in normal (8) and cancer cells, promotes cell viability (9, 10) and therefore bears unique therapeutic potential (11). Fractalkine (FKN, a.k.a CX3CL1) (12) – the sole chemokine ligand of CX3CR1 – exists as a trans-membrane protein with strong adhesive properties and can be cleaved into a soluble molecule with potent chemoattractant properties (13). We previously reported that FKN is constitutively expressed by endothelial and stromal cells of the human bone marrow both as membrane anchored and soluble forms (14). Thus, functional interactions between FKN and its receptor are distinctively capable of mediating adhesion and extravasation of CX3CR1-expressing CTCs at the skeletal level as well as supporting tumor colonization and progression in secondary organs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell cultures

MDA-MB-231 (MDA-231) and SKBR3 human breast cancer cell lines were purchased from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) and McCoy's 5A (Invitrogen), respectively, containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 0.1% gentamicin (Invitrogen). Starting from the original vials from ATCC, each cell line was expanded and frozen in different aliquots that were used for not more than 10 passages and not longer than 2 months following resuscitation. Each cell line was genetically engineered to stably express Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) by transduction with a proprietary lentiviral vector (Addgene) in DMEM for 24 hours.

Clinical samples, Immunohistochemistry, and Digital Image Analysis

De-identified human tissue specimens from primary breast tumors and bone-metastatic lesions from breast cancer patients were obtained from the archives of the Department of Pathology at Drexel University College of Medicine. Immunohistochemical detection of breast adenocarcinoma markers in primary tumors and CX3CR1 in bone metastases was conducted using a BenchMark ULTRA module (Ventana) with the following protocol: antigen retrieval (pH 8.1) using CC1 reagent 64 minutes, followed by primary antibody incubation for 40 minutes at 37°C, and then staining with the XT, Ultraview™ Universal DAB Detection Kit (Ventana). We used primary antibodies against Estrogen Receptor (ER) (Clone: SP1), Progesterone Receptor (PR) (Clone: 1E2), Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor (HER2) (Clone: 4B5) all from Ventana and diluted 1:50 on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections. For the detection of CX3CR1 in human primary tumors and metastases we used a primary antibody from Abcam CX3CR1 (ab802) as follows: sections were deparaffinized for 30 minutes using a Xylene Substitute (Thermo Scientific), followed by rehydration in an ethanol gradient. Antigen retrieval was performed heating the sections at 95°C for 1 hour using Epitope Unmasking Solution (ProHisto), tissues were blocked with normal goat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch), followed by overnight incubation with the primary antibody at 4°C. For the negative control staining, the CX3CR1 primary antibody was mixed with its control peptide (Abcam ab8125) for 1 hour prior to incubation with the tissues. Anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and DAB kit (Vector Shield) were used for visualization of the staining. Counterstaining was performed using Harris’ Alum Hematoxylin (EMD Chemicals) for one minute. Interpretation and scoring of sections were conducted by two clinical pathologists (J.Y. and F.U.G.) using the Aperio ePathology System (Leica Biosystems).

In vitro stimulation of CX3CR1 and analysis of downstream signaling

SKBR3 human breast cancer cells were serum starved for four hours before being exposed to 50nM recombinant human FKN (R&D Systems) for 5 minutes, with or without previous incubation with either a CX3CR1 neutralizing antibody (TP-502, Torrey Pines Biolabs) used at 15μg/ml or the JMS-17-2 antagonist (10nM) for 30 minutes at 37 °C.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

Cell lysates were obtained using a single detergent lysis buffer containing DTT, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem), protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem) and Igepal CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentrations of cellular lysates were determined using a BCA protein assay (Pierce). Samples containing equivalent amounts of protein were resolved by SDS-PAGE using 10% polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto Immobilon PVDF membranes (Millipore Corporation). Membranes were blocked for one hour at room temperature with 0.1% Tween-20/TBS with 5% (w/v) powdered milk. Human CX3CR1 was detected using a primary rabbit polyclonal antibody (TP-502, Torrey Pines Biolabs) used at 0.5μg/ml whereas the activation of the ERK signaling pathway was detected with rabbit phospho-ERK and total-ERK antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) at 10ng/ml. Primary antibodies were diluted in 0.1% Tween-20/TBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. A secondary, HRP-conjugated antibody (Pierce) was used at 10ng/ml. Blotted membranes were processed with SuperSignal Femto chemiluminescence substrates (Pierce) and visualized using a FluorChem imaging system (ProteinSimple).

Chemotaxis assay

MDA-231 cells (1×105) were starved overnight and plated in the top chamber of transwell inserts (filters with 8-μm pore diameter; BD Falcon) 200μl of serum-free culture medium. The inserts were transferred into a 24-well plate where each well contained 700μl of serum-free medium with or without recombinant human FKN (50nM; R&D). Positive controls were obtained using 10% FBS. For experiments involving JMS-17-2 and the CX3CR1 neutralizing antibody (Torrey Pines Biolabs), cells were plated on the upper side of the filters in serum-free medium containing JMS-17-2 (1nM, 10nM and 100nM) or the antibody (15μg/ml) and then transferred to wells containing JMS-17-2 or the neutralizing antibody plus FKN. Cells were allowed to migrate at 37°C for 6 hours and at the end of the assay the cells still on the top of the filter were removed by scrubbing twice with a tipped swab. Cells migrated to the bottom of the filter were fixed with 100% methanol for 10 minutes; filters were then washed with distilled water, removed from the insert and mounted on cover glasses using mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector) for nuclear staining. Two replicates were conducted for each condition, and five random microscope fields were used for cell enumeration, conducted with an Olympus BX51 microscope connected to the Nuance multispectral imaging system using version 2.4 of the analysis software (CRI). Three independent experiments were performed and results were presented as a ratio of cells that migrated under each condition relative to cells that migrated in control conditions (serum-free culture medium).

Generation of stable cell lines expressing either dCas9 or Tet-regulatable dCas9 cell lines and co-expression of gRNAs for the CX3CR1 gene

CX3CR1-specific gRNAs were expressed using a lentiviral U6-based expression vector carrying a puromycin-resistant gene (Addgene, 52963). The gRNA expression plasmids were cloned by inserting CX3CR1 targeting sequences (5’- CTGCACGGTCCGGTTGTTCA-3’; 3’-GACGTGCCAGGCCAACAAGT-5’) into the lentiviral expression vector. Lentiviral expression vector of the human codon-optimized, nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) protein fused with transcription suppressor KRAB domain was purchased from Addgene (Addgene, 46911). A Tet-regulatable dCas9-KRAB lentiviral expression vector carrying a neomycin-resistant gene was also purchased from Addgene (Addgene Plasmid 50917). HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. For lentivirus generation, HEK293T cells were split and plated at 1.3×105 cells/cm2. The following day, packaging plasmids (pCMV R8.74; pMD2.G) and dCas9-, Tet-regulatable dCas9 or gRNA-coding plasmids were transfected using lipofectamine 2000 in Opti-MEM according to the manufacturer's instructions. Viruses were harvested 48 hours after transfection and incubated with MDA-231 cells expressing both GFP and luciferase in the presence of polybrene. Transduced cells were selected using G418 (1000μg/ml) or puromycin (1.5μg/ml) for 3 weeks. Tet-regulatable dCas9 expression was induced in vitro by adding 2μg/ml doxycycline to complete culture medium.

Animal models of metastasis

SCID mice (Taconic CB17-SCRF, ~ 25g body weight) were housed in a germ-free barrier. At 6 weeks of age, mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (80mg/kg) and xylazine (10mg/kg). Tumor cells were delivered as a 100μl suspension of serum-free culture medium by carefully accessing the left ventricle of the heart through the chest with an insulin syringe mounting a 30-gauge needle.

Model of tumor seeding

For the pre-incubation experiments, MDA-231 cells in suspension were exposed to either a CX3CR1 neutralizing antibody (15μg/ml, Torrey Pines Biolabs) or the JMS-17-2 compound (10nM in 0.1% DMSO) for 30 minutes (10 minutes at room temperature plus 20 minutes on ice), before being delivered to mice in the same pre-incubation suspension to maximize target engagement. Species- and class-matched irrelevant immunoglobulins (Rabbit IgG, 15μg/ml, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or DMSO were used for the control groups. For the experiments requiring administration of JMS-17-2, animals were then treated i.p. with the CX3CR1 antagonist dissolved in 4% DMSO, 4% Cremophor EL (Kolliphor EL, Sigma-Aldrich, MO) in sterile ddH20 or just vehicle twice, one-hour prior and three hours after being injected with cancer cells. The dosing regimen was selected based on results from pharmacokinetic analyses. Mice were killed 24 hours post-injection, except for the experiments described in Fig. 3 A-C, for which mice were killed at two weeks post-injection. Blue-fluorescent beads, 10μm-polystyrene in diameter (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes) were included in the injection medium and visualized by fluorescence microscopy to validate injection efficiency. Mice showing non-homogenous distribution of or lacking fluorescent beads in tissue sections of lungs and kidneys were removed from the study.

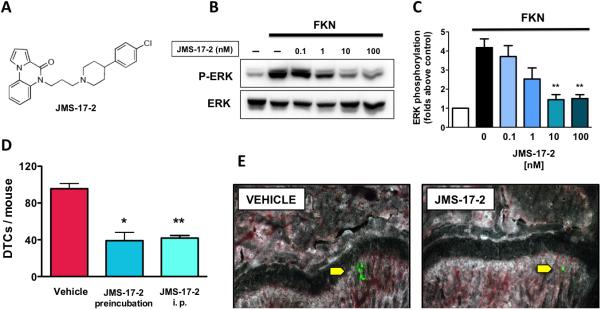

Figure 3.

JMS17-2 blocks CTCs from seeding the bone. A, The chemical structure of JMS-17-2, a novel small-molecule antagonist of CX3CR1. B and C, JMS-17-2 caused a dose-dependent inhibition of ERK phosphorylation in SKBR3 breast cancer cells exposed to 50nM FKN. (**p<0.001) D, MDA-231 cells were either pre-incubated with 10nM JMS-17-2 prior to IC inoculation in mice or inoculated in animals administered with the same antagonist at 10mg/Kg i.p. Both pre-incubation and i.p. administration of JMS-17-2 showed comparable and significant decrease in skeletal DTCs as detected 24 hours after cancer cell inoculation (Vehicle: n=8; JMS-17-2 pre-incubation: n=7; JMS-17-2 i.p.: n=8. *p=0.0001; ** p<0.0001). E, Two representative bone sections imaged by fluorescence microscopy, obtained from control and JMS-17-2 treated animals and showing green-fluorescent DTCs. Magnification: 200x.

Model of established metastases

One week after IC cell injection, animals were randomly assigned to control and treated group and then imaged for tumors in the skeleton and soft-tissue organs. Vehicle or JMS-17-2 (10mg/Kg) was administered i.p. twice/day, respectively, for the entire duration of the study while animals were imaged weekly.

All experiments were performed in agreement with NIH guidelines for the humane use of animals. The Drexel University College of Medicine Committee approved all protocols involving the use of animals for the Use and Care of Animals.

In vivo bioluminescence Imaging

MDA-231 cells were stably transduced with the pLeGo-IG2-Luc2 vector. Prior to imaging, animals were injected i.p. with 150 mg/Kg of D-luciferin (ViVoGlo, Promega) and anesthetized using 3% isoflurane. Animals were then transferred to the chamber of an IVIS Lumina XR (PerkinElmer) where they received 2% isoflurane throughout the image acquisition. Fifteen minutes after injection of the substrate, exposures of both dorsal and ventral views were obtained and quantification and analysis of bioluminescence was performed using the Living Image software.

Processing of animal tissues

Bones and soft-tissue organs were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 24 hours and then transferred into fresh formaldehyde for additional 24 hours. Soft-tissue organs were then placed either in 30% sucrose for cryoprotection or 1% paraformaldehyde for long-term storage. Bones were decalcified in 0.5M EDTA (Fisher Scientific) for 7 days followed by incubation in 30% sucrose. Tissues were maintained at 4°C for all aforementioned steps and frozen in O.C.T. medium (Sakura Finetek) by placement over dry-ice chilled 2-methylbutane. Soft-tissue organs as well as knee joints (femora and tibiae) were processed to obtain serial frozen sections, 80μm in thickness, using a Microm HM550 cryostat (15). All sections spanning the entire bone width (approximately 32 for femur and tibia) were inspected to obtain the accurate enumeration of DTCs and visualization and measurement of tumor foci in the inoculated animals.

Fluorescence microscopy and morphometric analysis of metastases

Fluorescent images of skeletal metastases were acquired using an Axio Scope.A1 microscope (Zeiss) connected to a Nuance Multispectral Imaging System (PerkinElmer). Digital images were analyzed and processed using the Nuance Software (v. 2.4). Microscope and software calibration for size measurement is regularly performed using a TS-M2 stage micrometer (Oplenic Optronics) (16) .

Pharmacophore design and synthesis of JMS-17-2

A potent CCR1 antagonist (17), was previously found to bind the cytomegalovirus receptor US28 (18). Since FKN also binds potently to this receptor, we speculated that this compound would also engage CX3CR1. Thus, we synthesized this CCR1 antagonist (named Compound-1) and found it to be also a functional antagonist of CX3CR1 with an IC50 = 268 nM, established by measuring the inhibition of FKN-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation detected with a plate-based assay. Subsequently, we optimized Compound-1 by modifying the diphenyl acetonitrile moiety and combining it with the right-hand aryl piperidine motif, which led to the discovery of a lead series and the compound JMS-17-2 (IC50 = 0.32 nM). The favorable potency shown by JMS-17-2 was combined with significant selectivity for CX3CR1 over other chemokine receptors such CXCR2 and CXCR1, for which this compound showed lack of activity at concentrations as high as 1μM as well as CXCR4 that was tested by Western blot analysis (a patent covering this compound was recently published [US no. 8,435,993] and a manuscript reporting synthesis and pharmacologic validation of JMS-17-2 in major detail has been submitted elsewhere).

Pharmacokinetic analyses

Mice were administered with 10mg/Kg of JMS-17-2 in 10% dimethylacetamide (DMAC), 10% tetraethylene glycol and 10% Solutol HS15 in sterile ddH2O. Animals were then anesthetized as described above and 300μl of blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture at the designated time points and transferred in K2EDTA tubes. Blood samples were placed on ice and tested after dilution. The measurement of JMS-17-2 concentrations in blood and brain tissue was outsourced to Alliance Pharma (www.alliancepharmaco.com).

Laser Capture Microdissection of tumor tissues from animal models of metastasis

Mouse tissues from different treatment groups were frozen in OCT (Optimal Cutting Temperature) cryo-embedding medium and sectioned at 40μm thickness. Sections were washed with ice-cold RNase-free water for 2 minutes to remove excessive OCT compound immediately prior to dehydration using ethanol gradient to maintain RNA integrity. LCM was performed using a Zeiss PALM MicroBeam system under the guidance of fluorescent signal emitted by GFP. Microdissected tissue specimens were catapulted into AdhesiveCap (Zeiss 415190-9191-000) and stored at −80°C.

qRT-PCR and Nanostring gene profiling of microdissected tissue samples

For qRT-PCR, microdissected tissue samples were slowly thawed at room temperature and RNA was extracted using RNeasy FFPE Kit (73504, Qiagen) according to the Zeiss's instructions (LCM protocol for RNA handling). RNA samples were stored at −80°C. TaqMan® RNA-to-Ct™ 1-Step Kit (4392653) was used on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System. Gene-specific primer and probe sets were purchased from Applied Biosystems. For Nanostring transcriptome analysis we used 100ng of total RNA (20ng/μl) on the PanCancer Pathways Panel, which includes 730 genes with established relevance in cancer plus 40 housekeeping genes used for normalization and selected with a geNorm algorithm (19). The nSolver (v.2.5) user interface was used to operate the nCounter Advanced analysis module, which employs the R statistical software. As an internal Quality Control step, we ran a comparative transcriptome analysis with MDA-231 cells growing in vitro, either wild-type cells or with CX3CR1 expression silenced by CRISPRi and found that none of the genes included in the PanCancer panel was altered in the CX3CR1-silenced cells as compared to wild-type cells. Thus, the differential gene expression observed between these two cells types, when growing as tumors in mice, were not a consequence of the use of CRISPRi per se.

Statistics

We analyzed data from two experimental groups using a two-tailed Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA test when comparing multiple groups. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was deemed significant.

RESULTS

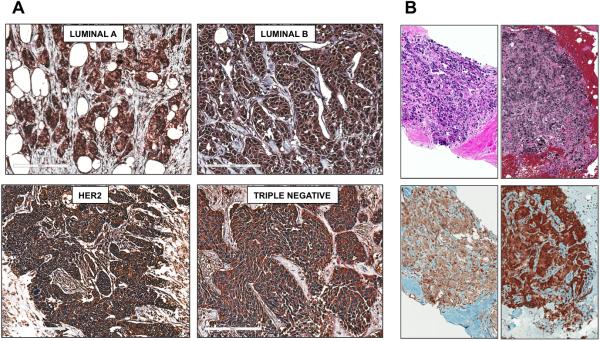

CX3CR1 is expressed in primary and metastatic human breast cancer

We examined surgical specimens from patients with primary breast adenocarcinoma classified as Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2 and Triple Negative (20) and found that these subtypes express CX3CR1 at comparable levels (Fig.1A). Since the percentage of patients with skeletal DTCs detected at initial diagnosis is unrelated to the status of Estrogen Receptor (ER), Progesterone Receptor (PR) or HER2 (21), this hints to a broad implication of CX3CR1 in dissemination to the skeleton rather than a role restricted to selected breast cancer subtypes. Consistently, tissue specimens from bone metastatic lesions were all found positive for CX3CR1 expression (Fig. 1B). The specificity of CX3CR1 staining in these human specimens was validated by negative controls obtained by pre-incubating the primary antibody with a blocking peptide prior to the IHC procedure (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

CX3CR1 is expressed in primary and metastatic breast cancer. A, Tissues from the four main subtypes of breast adenocarcinoma: Luminal A (LUM A; 7 specimens), Luminal B (LUM B; 7 specimens), Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 positive (HER2; 7 specimens) and Triple Negative (TN; 8 specimens) stained all positive for CX3CR1 expression. B, Two representative images of a total of seven biopsy specimens of skeletal metastatic tumors that were collected from different breast cancer patients and also stained all positive for CX3CR1. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining is shown in the upper panels. Magnification: 100-200x. Scale bar: 50μm

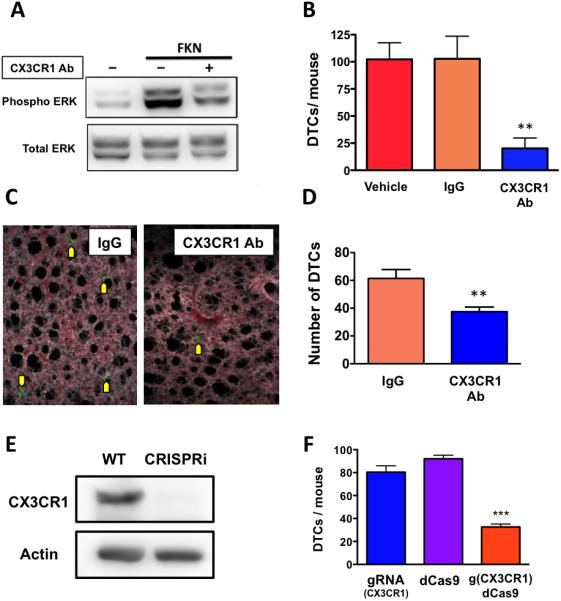

Targeting CX3CR1 impairs the seeding of circulating breast cancer cells

We previously reported that Fractalkine knock-out transgenic mice (22) grafted with MDA-231 cells in the blood showed a 70% reduction in the number of DTCs detected at the skeletal level as compared to syngeneic wild-type FKN-expressing animals (7). This indicates that the lack of the only chemokine ligand for CX3CR1 directly hampers the lodging of circulating breast cancer cells in the bone. Here we complemented this approach by preventing the engagement of CX3CR1 by FKN using neutralizing antibody against this receptor. Following a functional validation in vitro (Fig. 2A), the antibody was pre-incubated with MDA-231 cells to promote target engagement prior to their intracardiac (IC) inoculation in mice, a procedure that instantaneously generates CTCs and effectively replicates the tumor spreading through the systemic blood circulation (23). Blocking CX3CR1 with the neutralizing antibody reduced DTCs in the skeleton of inoculated animals by approximately 80% as compared to the same cells exposed to either vehicle or a species- and isotype-matched irrelevant immunoglobulin (Fig. 2B). To determine whether diverging cancer cells from seeding the skeleton as a consequence of targeting CX3CR1 could unintentionally promote tumor seeding of soft-tissues, mice were examined for DTCs in the lung by spectral fluorescence microscopy of serial tissue sections. We found that upon CX3CR1 antibody-blockade the cancer cells that lodged to the lung parenchyma were actually reduced in number as compared to control animals, similarly albeit by a smaller degree to the effects observed for the skeleton (Fig. 2C and D). This reduction of breast DTCs observed in the lungs is in agreement with previous studies by others reporting the expression of FKN by this tissue (24).

Figure 2.

Targeting CX3CR1 with a neutralizing antibody or transcriptional silencing by CRISPRi impairs the homing of breast cancer cells to the bone. A, The neutralizing antibody blocked ERK phosphorylation in SKBR3 human breast cancer cells induced by soluble FKN and assessed by Western blotting. B, Pre-incubation of cells with the same antibody prior to their IC inoculation in mice dramatically reduced the number of fluorescent MDA-231 cells detected in the knee joints 24 hours post-inoculation, as compared to animals that received cells pre-incubated with either vehicle or an irrelevant immunoglobulin (Vehicle: n=6; IgG: n=7; CX3CR1-Ab: n=6. **p<0.01). C, Representative images of fluorescent MDA-231 cells detected in the lung parenchyma of inoculated animals. Magnification 200x. D, Preventing the activation of CX3CR1 also significantly reduced the number of DTCs seeding the lungs from the systemic blood circulation, as compared to controls (IgG: n=6; CX3CR1-Ab: n=6. **p<0.01). E, The effective silencing of CX3CR1 in MDA-231 cells by CRISPRi was confirmed by Western blotting. F, when CX3CR1-silenced cells were inoculated in mice, the number of DTCs detected in bone was significantly reduced (gRNA: n=3; dCas9: n=3; g(CX3CR1)dCas9: n=5. *** p<0.001).

A second set of experiments was conducted by silencing CX3CR1 transcription in MDA-231 cells by CRISPRi, which completely abrogated CX3CR1 protein expression in vitro (Fig. 2E). When these cells were injected in mice via the IC route, the reduction in skeletal DTCs observed was fully comparable to that previously obtained with the antibody-neutralization of CX3CR1 (Fig. 2F). Control cells expressing only the guidance RNA (gRNA) or a deactivated Cas9 (dCAS9) disseminated to the skeleton with efficacy comparable to wild-type MDA-231 cells (compare with Fig. 2B).

Building on the target validation studies described above, we synthesized JMS-17-2, a small-molecule antagonist of CX3CR1, by exploiting important pharmacophoric features of non-specific chemokine antagonists and combining these with drug-like elements of G-protein coupled receptor ligands (Fig.3A and methods). JMS-17-2 potently antagonizes CX3CR1 signaling in a dose-dependent fashion, as measured by inhibition of ERK phosphorylation (Fig.3B and C). Interestingly, the two concentrations of JMS-17-2 most effective in blocking FKN-induced ERK phosphorylation also significantly reduced the migration of breast cancer cells in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S2).

We then sought to ascertain the effects of JMS-17-2 on the conversion of breast CTCs into skeletal DTCs, in our relevant pre-clinical model of metastasis. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of JMS-17-2 administered to mice at a dose of 10mg/Kg (i.p.) produced drug levels of 89ng/ml (210 nM) in blood measured one hour after dosing, which corresponds to a 20-fold increase over the lowest fully effective dose of this compound in vitro (10nM, see fig. 3B,C). Thus, a first group of mice received MDA-231 cancer cells pre-incubated with 10nM JMS-17-2, whereas a second group of animals was dosed with JMS-17-2 (10mg/Kg; i.p.) twice, one hour prior and three hours after the IC inoculation of cancer cells, to maximize target engagement. Remarkably, both experimental groups showed a reduction in DTCs of approximately 60% as compared to control animals treated with vehicle (Fig. 3D and E).

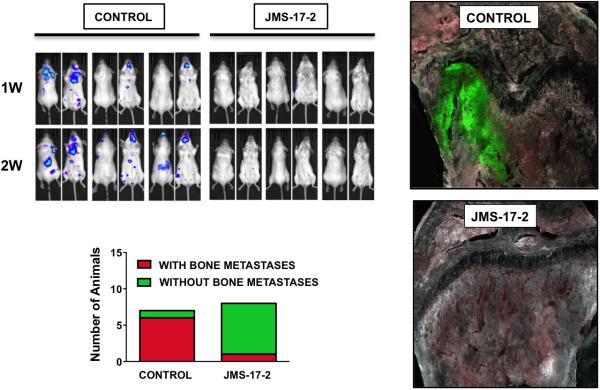

Reducing tumor seeding directly impairs colonization and growth

The prognostic value of breast DTCs detected in the bone marrow of patients has been established (25), with higher values corresponding to a poorer clinical outcome (26), (27). Since JMS-17-2 did not completely abolish the seeding of breast CTCs to the skeleton, we aimed to determine if and to which extent the reduction in skeletal DTCs would translate into a long-term inhibition of tumor growth. To this end, mice were grafted with MDA-231 cells engineered to express both fluorescent and bioluminescent markers and monitored by in vivo imaging during the two weeks following IC injection. Furthermore, the presence of skeletal tumors and DTCs was also assessed post-necropsy by examining bone tissue sections by multispectral fluorescence microscopy. These experiments showed that, in contrast to control animals presenting multiple tumors both in the skeleton and visceral sites, seven of the eight animals that received cancer cells pre-incubated with JMS-17-2 were found free of tumors (Fig. 4A and B). Notably, these animals were also found devoid of microscopic tumor foci and DTCs when inspected for fluorescent signals with multispectral microscopy-based imaging of frozen tissue sections (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

CX3CR1 inhibition shows long-term anti-tumor effects. A, Mice were inoculated via the left cardiac ventricle with MDA-231 cells, stably expressing both GFP and luciferase, and previously incubated with either vehicle or JMS-17-2. Tumor growth was monitored by in vivo bioluminescence imaging for two weeks post-inoculation until euthanasia. Treatment with JMS-17-2 caused a dramatic reduction of tumors in both skeleton and visceral organs. B, Only one of eight animals inoculated with cancer cells pre-incubated with the CX3CR1 antagonist presented with tumors, in contrast with six out of seven animals in the control group. C, Tissues were harvested under bioluminescence guidance and inspected for fluorescence to confirm the presence or absence of tumor lesions at the histological level, as shown by two representative images. Magnification: 200x.

CX3CR1 is implicated in the progression of established metastases

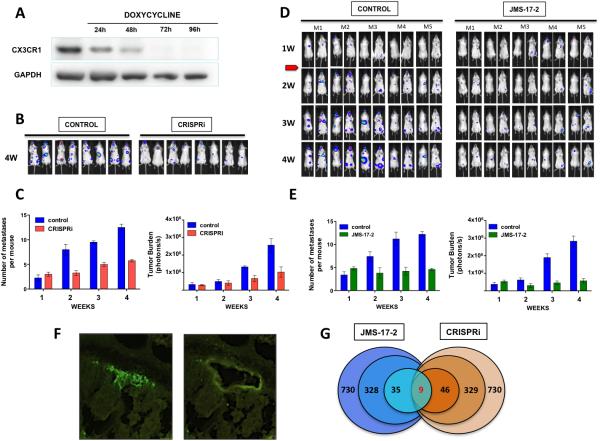

We next sought to replicate a common clinical scenario in which breast cancer patients present with early metastatic lesions, years after successful treatment of their primary tumor by local modalities. Despite treatment, these patients eventually and inevitably progress, presenting with a surge in tumor burden due to a multiplication of metastatic lesions by re-seeding (3,4). To this end, mice were IC injected with MDA-231 cells expressing a regulatable CRISPRi system for CX3CR1, which was first validated in vitro, providing a complete ablation of protein expression by 72 hours after administration of doxycycline (Fig. 5A). To replicate the onset of metastatic disease observed in the clinic, animals were left untreated until one week later, when bioluminescence imaging showed small tumors in skeleton and soft-tissues. At this stage, animals were randomly assigned to control or CRISPRi groups and received vehicle or doxycycline, respectively. Imaging continued weekly for the following 21 days before euthanasia. As shown, down-regulation of CX3CR1 expression significantly reduced both the number of total lesions/animal and the overall tumor burden (Fig.5B and C). The effective down-regulation of CX3CR1 by CRISPRi was confirmed by harvesting tumor tissues from different lesions by Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) and performing qRT-PCR analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3)

Figure 5.

Targeting CX3CR1 in a model of established metastases and transcriptome analyses of metastatic tumors. A, CX3CR1 was conditionally silenced by an inducible-CRISPRi system. Complete protein repression was achieved 72 hours after exposing cells to 2μg/ml of doxycycline. B, Mice were inoculated via the left cardiac ventricle with MDA-231-TRE-CRISPRi_CX3CR1 cells, stably expressing both GFP and luciferase. Animals were left untreated for one week after the inoculation of cancer cells; then, a doxycycline-containing diet was administered to the treatment group for the next following 3 weeks before euthanasia. Tumor progression was monitored weekly by in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Mice in both control and treatment groups imaged at 4 weeks are shown. C, Quantification of the number of metastatic lesions and overall tumor burden based on the detection of bioluminescent signal in both control and CRISPRi groups. D, Mice bearing one-week tumors in bones and soft-tissues were treated daily with JMS-17-2 (10mg/Kg - i.p. twice a day) for the next following 3 weeks before euthanasia. Control animals received only vehicle. E, Quantification of number of metastatic lesions and overall tumor burden based on bioluminescent signal in both control and JMS-17-2 treated groups. F, Two representative images of a mouse tissue section containing a bone tumor, identified by the emitted green fluorescence, before (left) and after (right) harvesting by LCM. G, Tumor tissues from four animals for each experimental groups (Control, JMS-17-2 and CRISPRi) were harvested and pooled for RNA isolation; of the 730 human genes with demonstrated implication in tumorigenesis and progression included in the nCounter PanCancer panel, approximately 330 genes were significantly altered in tumors collected from JMS-17-2 treated and CX3CR1-silenced tumors as compared to tumors in control animals. Of these genes, 46 for the JMS-17-2 group and 35 from the CX3CR1-silenced group showed at least 3-fold change. Nine of these genes were found to be affected in a similar fashion between the two experimental groups. Statistical significance was established by using the t-test module included in the nSolver software.

To determine whether the pharmacologic targeting of CX3CR1 with JMS-17-2 would produce similar effects, mice were grafted with MDA-231 cells and at the first week post-IC injection were randomized and administered with either vehicle or 10mg/Kg JMS-17-2 i.p. twice daily for three weeks, based on the results of our pharmacokinetics studies with this compound. Animals were imaged weekly before being euthanized and we observed that treatment with JMS-17-2 led to a reduction in the number of tumor foci and overall tumor burden, at least as effectively as observed using CRISPRi (Fig. 5D and E). Taken together, these results point towards a crucial role of CX3CR1 in dictating seeding, colonization and progression of disseminated breast cancer cells. We decided to ascertain whether interfering with CX3CR1 functioning could alter the expression of genes with an established role in tumorigenesis. Thus, tumor tissues collected by LCM (Fig. 5F) were interrogated using Nanostring technology for the expression of 730 genes including 606 genes regulating 13 canonical signaling pathways and 124 cancer driver genes (PanCancer Panel). A comparative analysis of CRISPRi and JMS-17-2 treatment showed that nine genes were similarly altered, with WNT5a being the only up-regulated gene (Fig. 5G and table 1). Notably, both pharmacologic and genomic targeting of CX3CR1 resulted in a strong down-regulation of NOTCH3 (table 1) and significant deregulation of the Notch signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Tumor-associated genes altered by targeting CX3CR1 in vivo

| Gene Name | Accession # | CRISPRi vs. Control | JMS-17-2 vs. Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL7R | NM_002185.2 | −7.63 | −3.16 |

| SSX1 | NM_005635.2 | −4.74 | −15.46 |

| INHBB | NM_002193.2 | −4.6 | −4.48 |

| N0TCH3 | NM_000435.2 | −4.32 | −4.28 |

| SOST | NM_025237.2 | −3.55 | −4.12 |

| PRLR | NM_001204318.1 | −3.5 | −3.42 |

| FGF13 | NM_033642.1 | −3.48 | −3.32 |

| CD40 | NM_001250.4 | −3.45 | −3.48 |

| WNT5A | NM_003392.3 | 5.77 | 3.28 |

DISCUSSION

The multiple organ failure associated with distant recurrence of primary tumors such as breast adenocarcinoma is by far the most frequent cause of patients’ demise. About 30% of breast cancer patients will eventually develop multiple secondary lesions in skeleton and soft-tissue organs and metastatic disease can currently be treated yet still not cured (1), (28). There is abundant evidence that distant spreading, proliferation and survival of cancer cells is regulated by chemokine receptors (29). In particular, studies from our laboratory and others suggest that CX3CR1 drives cancer cells to the skeleton in animal models (7), activates pro-survival signaling pathways in normal and tumor cells and promotes cell viability (9, 10). Thus, while interfering with CX3CR1 functioning bears unique therapeutic potential (11), potent and selective antagonists of this receptor as well as compelling pre-clinical evidence for its functional role in tumor cells dissemination and metastatic progression have been lacking.

The findings reported here demonstrate the crucial role of the CX3CR1-FKN pair in guiding circulating breast cancer cells to seed the skeleton and soft-tissue organs as well as to support their colonization and growth into macroscopic tumor lesions. Most importantly, we have synthesized a novel small-molecule antagonist of CX3CR1 and provided pre-clinical functional validations of its activity in both preventing the conversion of CTCs into DTCs and counteracting the expansion of number and size of existing tumors in bone and visceral organs.

CX3CR1 might contribute equally to the distant seeding of breast cancer cells independently of their molecular features, since all four commonly recognized subtypes of mammary adenocarcinoma express this receptor at comparable levels. Notably, high CX3CR1 expression was observed also in bone metastases, indicating that during colonization and growth in the bone microenvironment cancer cells preserve this receptor on their surface and remain susceptible to signaling by FKN. This is of relevance due to our previous studies reporting the detection of this chemokine in human bone marrow (14). In initial pre-clinical studies we also reported that transgenic mice knockout for FKN showed reduced seeding of breast CTCs to the skeleton (7). Herein we further validate this preliminary observation using a neutralizing antibody or stable transcriptional silencing by CRISPRi, which were both able to drastically impair the CX3CR1-dependent tumor seeding to skeleton and lungs of mice grafted with breast cancer cells in the systemic blood circulation. Building on these data, we sought to determine the potential for pre-clinical antitumor effects generated by the pharmacologic targeting of CX3CR1 and proceeded with synthesizing a novel small-molecule compound directed to impair CX3CR1 functional activation by FKN. The two concentrations of JMS-17-2 most effective in blocking ERK phosphorylation were also able to significantly reduce the migration of breast cancer cells, which in vivo translates as impairing the transmigration of cancer cells through endothelial cells and extravasation (12), (30). Our in vivo studies showed that interfering with the engagement of CX3CR1 on cancer cells by its only known ligand FKN – achieved by using either immunologic, genetic or pharmacological means, is sufficient to severely limit the ability of breast CTCs to extravasate and lodge to different organs. Notably, the approximately 30-40% of MDA-231 cells that still harbor to the skeleton notwithstanding the inhibition of CX3CR1 failed to either survive in a dormant state or generate tumors. This suggests that subpopulations of breast cancer cells, while able to circumvent the need for CX3CR1 to seed the skeleton by relying on alternative molecules, such as CXCR4 for prostate cancer cells (31), may lack tumorigenic potential.

A major clinical need is to identify effective treatment to delay disease progression in patients presenting with few metastatic lesions. It has been recently demonstrated that existing metastases function as active reservoirs of tumor cells, cross-seeding other metastases and generate additional lesions, which makes therapeutic treatments directed to effectively counteract cancer seeding urgently needed (5). The target validation achieved in vivo with CRISPRi silencing of CX3CR1 provided impetus to test the JMS-17-2 compound in animals reproducing early metastatic onset in patients. The results from these experiments are strongly indicative that impairing CX3CR1 can successfully limit metastatic cross-seeding. On the other hand, the unexpected observation that both JMS-17-2 treatment and CRISPRi drastically restricted the growth of single lesions and contained the overall tumor burden could not be justified by interfering with tumor seeding.

Therefore, to understand the mechanistic basis underpinning this role of CX3CR1 in regulating secondary tumor growth and identify the signaling pathway altered by targeting this receptor, we harvested tumor tissues from animals in the control, JMS-17-2 treated and CRISPRi experimental groups and conducted comparative transcriptome analyses using Nanostring technology. Using this uniquely informative approach, we found that nine genes were altered in a corresponding fashion by JMS-17-2 and CRISPRi-mediated gene silencing, thus revealing molecular mediators for the role of CX3CR1 in supporting survival and proliferation of disseminated breast cancer cells. Particularly relevant is the up-regulation of WNT5A, involved in non-canonical Wnt signaling and endowed with a suppressive activity on metastatic breast cancer (32). The down-regulation of SOST, highly implicated in bone-related disease (33) and PRLR, which promotes colonization of breast cancer cells in soft tissues, are equally compelling (34). Finally, the down-regulation of NOTCH3 and deregulation of Notch signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. S4) are strongly indicative of a possible role of CX3CR1 antagonism mitigating the tumor-initiating properties regulated by this gene in breast cancer (35,36). Indeed, CX3CR1 transactivates the Epidermal Growth Factor signaling pathway in breast cancer cells, promoting cell proliferation in vitro and delaying mammary tumor onset in mouse models (37,38).

In conclusion, the work presented here introduces a conceptual shift in the treatment strategies for breast cancer patients. Furthermore, we have synthesized and functionally characterized the first lead compound in a novel class of potentially new drugs with novel mechanisms of action to be added to the arsenal of therapies to treat advanced breast adenocarcinoma.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Drs. W. Kevin Kelly (Medical Oncology) and Adam P. Dicker (Radiation Oncology), at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center of Thomas Jefferson University, for inputs and discussion, and the Genomic Core Facility of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute (CTRI) at Drexel University College of Medicine, for the invaluable support. This work was funded by grants from the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement (CURE) program and the Pennsylvania Breast Cancer Coalition (PA BCC) to A.F., and in part by NIH grants CA178540 (J.M.S and A.F.) and DA15014 (O.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Shaughnessy J. Extending survival with chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2005;10(Suppl 3):20–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-90003-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Even-Sapir E. Imaging of malignant bone involvement by morphologic, scintigraphic, and hybrid modalities. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1356–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gundem G, Van Loo P, Kremeyer B, Alexandrov LB, Tubio JMC, Papaemmanuil E, et al. The evolutionary history of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature. 2015;520:353–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong MKH, Macintyre G, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Patel K, Lunke S, et al. Tracking the origins and drivers of subclonal metastatic expansion in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6605. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steeg PS. Perspective: The right trials. Nature. 2012;485:S58–9. doi: 10.1038/485S58a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulby S, Dolloff N, Stearns M, Meucci O, Fatatis A. CX3CR1-fractalkine expression regulates cellular mechanisms involved in adhesion, migration, and survival of human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4693. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamieson-Gladney WL, Zhang Y, Fong AM, Meucci O, Fatatis A. The chemokine receptor CX3CR1 is directly involved in the arrest of breast cancer cells to the skeleton. Breast Cancer Research. 2010;12:307. doi: 10.1186/bcr3016. BioMed Central Ltd. BioMed Central Ltd; 2011;13:R91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meucci O, Fatatis A, Simen AA, Miller RJ. Expression of CX3CR1 chemokine receptors on neurons and their role in neuronal survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090017497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saitoh Y, Koizumi K, Sakurai H, Minami T, Saiki I. RANKL-induced down-regulation of CX3CR1 via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway suppresses Fractalkine/CX3CL1-induced cellular responses in RAW264.7 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364:417–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferretti E, Bertolotto M, Deaglio S, Tripodo C, Ribatti D, Audrito V, et al. A novel role of the CX3CR1/CX3CL1 system in the cross-talk between chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells and tumor microenvironment. Leukemia. 2011;25:1268–77. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Haese JG, Demir IE, Friess H, Ceyhan GO. Fractalkine/CX3CR1: why a single chemokine-receptor duo bears a major and unique therapeutic potential. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:207–19. doi: 10.1517/14728220903540265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai T, Hieshima K, Haskell C, Baba M, Nagira M, Nishimura M, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell. 1997;91:521–30. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazan JF. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997:385. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamieson WL, Shimizu S, D'Ambrosio JA, Meucci O, Fatatis A. CX3CR1 is expressed by prostate epithelial cells and androgens regulate the levels of CX3CL1/fractalkine in the bone marrow: potential role in prostate cancer bone tropism. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1715–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell MR, Liu Q, Fatatis A. Targeting the {alpha} receptor for platelet-derived growth factor as a primary or combination therapy in a preclinical model of prostate cancer skeletal metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5002–10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Q, Russell MR, Shahriari K, Jernigan DL, Lioni MI, Garcia FU, et al. Interleukin-1β promotes skeletal colonization and progression of metastatic prostate cancer cells with neuroendocrine features. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3297–305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naya A, Sagara Y, Ohwaki K, Saeki T, Ichikawa D, Iwasawa Y, et al. Design, synthesis, and discovery of a novel CCR1 antagonist. J Med Chem. 2001;44:1429–35. doi: 10.1021/jm0004244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulshof JW, Vischer HF, Verheij MHP, Fratantoni SA, Smit MJ, de Esch IJP, et al. Synthesis and pharmacological characterization of novel inverse agonists acting on the viral-encoded chemokine receptor US28. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:7213–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onitilo AA, Engel JM, Greenlee RT, Mukesh BN. Breast cancer subtypes based on ER/PR and Her2 expression: comparison of clinicopathologic features and survival. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2009;7:4–13. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2009.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruber I, Fehm T, Taran FA, Wallwiener M, Hahn M, Wallwiener D, et al. Disseminated tumor cells as a monitoring tool for adjuvant therapy in patients with primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144:353–60. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2853-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook DN, Chen SC, Sullivan LM, Manfra DJ, Wiekowski MT, Prosser DM, et al. Generation and analysis of mice lacking the chemokine fractalkine. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3159–65. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.9.3159-3165.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bos PD, Nguyen DX, Massagué J. Modeling metastasis in the mouse. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2010;10:571–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim K-W, Vallon-Eberhard A, Zigmond E, Farache J, Shezen E, Shakhar G, et al. In vivo structure/function and expression analysis of the CX3C chemokine fractalkine. Blood. 2011;118:e156–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riethdorf S, Wikman H, Pantel K. Review: Biological relevance of disseminated tumor cells in cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1991–2006. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ignatiadis M, Georgoulias V, Mavroudis D. Micrometastatic disease in breast cancer: clinical implications. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2726–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin H, Balic M, Zheng S, Datar R, Cote RJ. Disseminated and circulating tumor cells: Role in effective cancer management. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2011;77:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckhardt BL. Strategies for the discovery and development of therapies for metastatic breast cancer. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2012;11:479–97. doi: 10.1038/nrd2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantovani A, Savino B, Locati M, Zammataro L, Allavena P, Bonecchi R. The chemokine system in cancer biology and therapy. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2010;21:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nevo I, Sagi-Assif O, Meshel T, Ben-Baruch A, Jöhrer K, Greil R, et al. The involvement of the fractalkine receptor in the transmigration of neuroblastoma cells through bone- marrow endothelial cells. Cancer Letters. 2009;273:127–39. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiozawa Y, Pienta KJ, Taichman RS. Hematopoietic stem cell niche is a potential therapeutic target for bone metastatic tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5553–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu N, Qin L, Luo Z, Guo Q, Yang L, Liao D. Challenging role of Wnt5a and its signaling pathway in cancer metastasis (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:3–8. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gkotzamanidou M, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Christoulas D, Moulopoulos LA, Terpos E. Sclerostin: a possible target for the management of cancer-induced bone disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16:761–9. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.697154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yonezawa T, Chen K-HE, Ghosh MK, Rivera L, Dill R, Ma L, et al. Anti-metastatic outcome of isoform-specific prolactin receptor targeting in breast cancer. Cancer Letters. 2015;366:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sansone P, Ceccarelli C, Berishaj M, Chang Q, Rajasekhar VK, Perna F, et al. Self-renewal of CD133(hi) cells by IL6/Notch3 signalling regulates endocrine resistance in metastatic breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10442. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yen W-C, Fischer MM, Axelrod F, Bond C, Cain J, Cancilla B, et al. Targeting Notch signaling with a Notch2/Notch3 antagonist (tarextumab) inhibits tumor growth and decreases tumor-initiating cell frequency. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2084–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tardáguila M, Mañes S. CX3CL1 at the crossroad of EGF signals: Relevance for the progression of ERBB2(+) breast carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e25669. doi: 10.4161/onci.25669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tardáguila M, Mira E, García-Cabezas MA, Feijoo AM, Quintela-Fandino M, Azcoitia I, et al. CX3CL1 promotes breast cancer via transactivation of the EGF pathway. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4461–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.