Abstract

Almost 40% of individuals with eating disorders have a comorbid addiction. The current study examined weight/shape concerns as a potential moderator of the relation between the hypothesized latent factor “addiction vulnerability” (i.e., impairments in reward sensitivity, affect regulation and impulsivity) and binge eating. Undergraduate women (n=272) with either high or low weight/shape concerns completed self-report measures examining reward sensitivity, emotion regulation, impulsivity and disordered (binge) eating. Results showed that (1) reward sensitivity, affect regulation and impulsivity all loaded onto a latent “addiction vulnerability” factor for both women with high and with low weight/shape concerns, (2) women with higher weight/shape concerns reported more impairment in these areas, and (3) weight/shape concerns moderated the relation between addiction vulnerability and binge eating. These findings suggest that underlying processes identified in addiction are present in individuals who binge eat, though weight/shape concerns may be a unique characteristic of disordered eating.

Keywords: eating disorders, addiction, reward sensitivity, emotion regulation, impulsivity, binge eating, urgency

1. Introduction

Eating Disorders (EDs; e.g., anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED)) have lifetime prevalence rates ranging from 0.6-2.8% of the population.1,2 Binge eating, (i.e., the consumption of atypically large amounts of food while experiencing loss of control) occurs across EDs and is characteristic of BED. Criteria for BED include recurrent bingeing (≥1/week for 3 months) without compensatory behaviors and at least 3 characteristics of bingeing (e.g., eating rapidly, eating until uncomfortably full).1 Binge eating is the most common ED symptom occurring in 4.5%-6.9% of people and is associated with medical complications (e.g., infertility, obesity, metabolic syndrome).1,3

1.2 Overlap of Eating and Addictive Disorders

Both EDs and addictive disorders2 show a similar developmental trajectory, with onset often occurring in adolescence, following a chronic course, and frequently involving periods of remission and recurrence.1,4,5 Further, there is significant comorbidity, with nearly 40% of individuals with EDs meeting criteria for addiction.2 These behavioral similarities are associated with neurobiological impairments in dopaminergic and serotonergic systems.5-7 However, while some argue that bingeing in EDs is a form of addiction,8,9 others maintain that binge eating and addiction represent distinct conditions.10,11 Examining impairments in common underlying mechanisms of bingeing and addiction (i.e., reward sensitivity, affect regulation, and impulsivity) may clarify the extent to which these phenotypes overlap and may improve assessment, prevention, and treatment of EDs.

1.3 Reward Dysfunction

Reward dysfunction is implicated in EDs and addiction; however, it is unclear whether hypo- or hypersensitivity is responsible.12 Reward deficiency theory,13 which is commonly associated with substance use disorders, posits that individuals resort to using drugs (or other highly rewarding behaviors) to compensate for an innate hyposensitive response to reward caused by a genetic determinant attributed to reduced dopamine receptors. Reward sensitivity theory14 posits that hypersensitivity to rewarding properties of stimuli (e.g., drug or food) increases the addictive potential of those stimuli. Either variant of reward dysfunction manifests as difficulty tolerating delayed reward and increased desire for the rewarding stimuli.15 Individuals with addiction endorse impaired reward sensitivity16 and perform poorly on delay discounting tasks.17 Similarly, in addition to being hyper-responsive to the hedonistic properties of food,6 individuals who binge eat report impaired reward processing,18,19 and perform poorly on delay discounting.19,20 Reward dysfunction has been linked to neurological and genetic underpinnings in both addiction and EDs,21,22 providing further evidence that individuals with EDs exhibit similar reward system dysfunction as in addiction although the dysfunction (i.e., deficiency or hypersensitivity) may differ.12-14

1.4 Affect Regulation

Another impairment in addiction and EDs is poor affect regulation. Affect regulation encompasses awareness, understanding, and acceptance of emotions, as well as the ability to modulate responses to emotion.23 According to the Self-Medicating Hypothesis, individuals engage in continued drug use to avoid or escape negative affect.24 Drug use initially reduces negative affect but ultimately results in increased negative affect.25 Similarly, individuals who binge eat often report engaging in bingeing to escape from negative emotions.26,27 While bingeing can temporarily emotional relief, distress is often ultimately exacerbated due to feelings of shame and guilt from losing control over eating.28 Individuals with addiction or EDs endorse impaired affect regulation29,30 and lower levels of emotional control than non-clinical participants.31 Further, both have a high rate of comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders.1,2 Thus, impaired affect regulation appears to contribute to both EDs and addiction.

1.5 Impulsivity-Urgency

Impulsivity is a multifaceted construct32,33 that encompasses behavior that occurs without careful consideration, exhibiting a component of rashness. Across a variety of domains, individuals with EDs or addictions demonstrate increased levels of trait and behavioral impulsivity.32,34-36 However, negative and positive urgency (i.e., acting rashly in response to negative or positive mood) have emerged as the strongest impulsivity domains related to EDs and addiction.37,38 Taken together, the data suggest impulsivity, specifically urgency, is associated with addiction and EDs.

1.6 Addiction Vulnerability

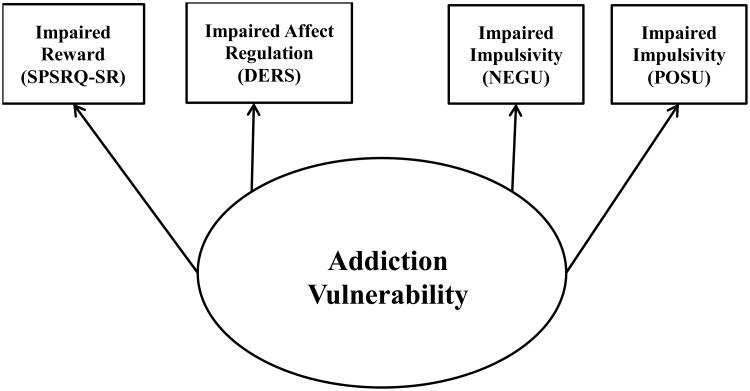

Significant commonalities between addiction and EDs with bingeing behavior are found in three impairments: 1) reward processing, 2) affect regulation, and 3) impulsivity.15 Although these constructs are distinct, they are interrelated. For example, the rash action defined by urgency is a behavioral response to emotions. Additionally, it is difficult to inhibit behavior in the presence of something extremely rewarding. Furthermore, evidence suggests these constructs likely have overlapping neurocircuitry.14,20,39,40 Together these three deficits are posited to contribute to an “addiction vulnerability” (see Figure 1). The present study extends the use of this model to identify when impairments in these three areas might lead to the development of binge eating.

Figure 1.

Measurement Model of Addiction Vulnerability. Oval represents latent constructs and rectangles represent measured constructs. SPSRQ – SR = Sensitivity to Punishment and Reward Questionnaire – Sensitivity to Reward Subscale; DERS = Overall Score on the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; NEGU = (negative) Urgency subscale of the UPPS-P; POSU = Positive Urgency subscale of the UPPS-P.

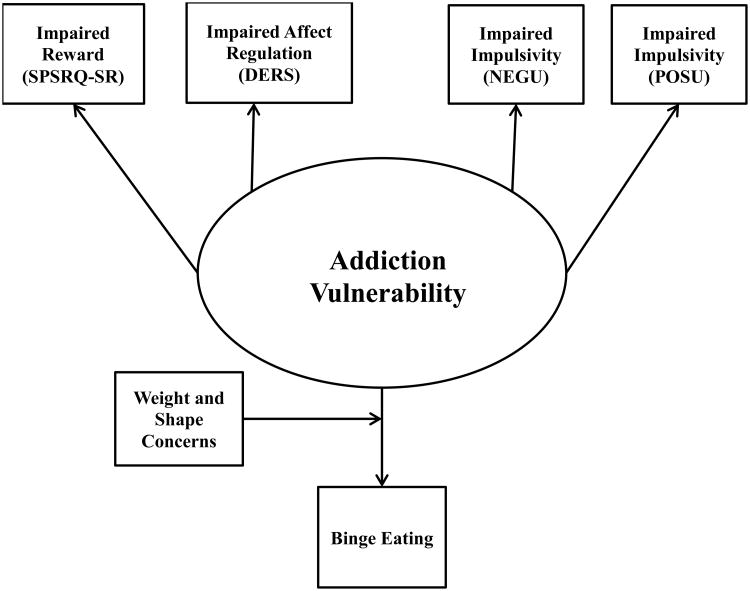

Weight and shape concerns are a defining characteristic of EDs.1,41 Specifically, greater shape and weight concerns are associated with greater ED symptomatology and can differentiate individuals with or without EDs.41 Yet, no data suggest weight/shape concerns are associated with addictive disorders. Accordingly, weight and shape concerns may differentiate individuals with and without binge eating, who are predisposed to addiction vulnerability, such that individuals with high weight/shape concerns will develop binge eating, whereas those with low weight/shape concerns will not (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed Model Reflecting Weight and Shape Concerns Moderate the Relationship between EDs and Addiction Vulnerability. Oval represents latent constructs and rectangles represent measured constructs. SPSRQ – SR = Sensitivity to Punishment and Reward Questionnaire – Sensitivity to Reward Subscale; DERS = Overall Score on the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; NEGU = (negative) Urgency subscale of the UPPS-P; POSU = Positive Urgency subscale of the UPPS-P.

The current study aimed to better characterize impaired processes, which may be related to a common phenotype underlying addiction vulnerability. Self-report measures were utilized to examine three key deficits established in the addiction literature15: 1) impaired reward, 2) impaired affect regulation and 3) impaired impulsivity (i.e., urgency) in relation to binge eating in college women. Binge eating was the ED behavior of interest because of its prevalence across EDs.1 The primary aims were to: 1) evaluate the addiction vulnerability construct itself and 2) in relation to binge eating (see Figure 2). We hypothesized that 1) reward sensitivity, affect regulation and impulsivity would load on the addiction vulnerability construct and 2) weight and shape concerns would moderate the relationship between addiction vulnerability and binge eating.

2. Method

2.1 Participants and Procedures

Undergraduate females (N=486) from a mid-Atlantic university were recruited via a secure online system through which students enroll in research studies to earn credits for course requirements. Details of the study were provided via an online consent form. After agreeing to participate, participants completed self-report measures via the online system. Exclusion criteria were being male or age being outside of 18-25 years old. Females (n=272) who met criteria for either high (i.e., scored in the top third of the weight (≥ 3.20) and shape (≥ 3.625) subscales of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q), n =135) or low (i.e., scored in the bottom third of the weight (≤1.20) and shape (≤1.75) subscales, n=137) weight/shape concerns were included in these analyses. Average age of participants was 20.16 years (SD=1.67), average self-report BMI was 23.50 kg/m2 (SD=4.5) and the sample was mostly Caucasian (61.5%; African American-16.5%, Asian-8.1%, Latino-5.1%). This study was approved by the university's Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Self-Report Measures

All questionnaires utilized have good psychometric properties23,42-45 and α levels for this sample are provided below.

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire46 (EDE-Q) is a 28-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the presence of ED symptomatology and attitudes over the previous four weeks. The item “Over the past 28 days, on how many days have such episodes of overeating occurred (i.e., you have eaten an unusually large amount of food and have had a sense of loss of control at the time)?” assessed binge eating. Weight and shape concerns were assessed using the weight (α = 0.93) and shape (α = 0.96) concerns subscales which include items that assess concern about the number on the scale (weight) or one's figure (shape).

The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire47-Sensitivity to Reward subscale (SPSRQ-SR; α = 0.87) was used to measure reward sensitivity. Responses range from “Very untrue of me” to “Very true of me” on a 5-point Likert scale to items such as “Do you often do things to be praised?” and “Do you sometimes do things for quick gains?”

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale23 (DERS) total score (α = 0.95) was used to measure affect regulation. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “almost never” to “almost always”, and include items such as “I am attentive to my feelings” and “I have no idea how I am feeling.”

The UPPS-P Impulsivity Scale Negative Urgency (NEGU; α = 0.89) and Positive Urgency (POSU; α = 0.94)33 subscales were used to measure impulsivity. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert-like scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. NEGU includes item like “When I am upset I often act without thinking” whereas POSU includes items like “I tend to lose control when I am in a great mood.”

2.3 Data Analytic Plan

M-plus version 6.1248 was used to conduct analyses. A multiple-sample confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) tested the proposed factor structure (Figure 1) for the latent construct, addiction vulnerability, in individuals with high weight/shape concerns and individuals with low weight/shape concerns. Data were analyzed using the maximum-likelihood estimation procedure (ML). To assess goodness of fit, the χ2 statistic, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were calculated. CFI values > .95 and RMSEA values < .06 indicate a good fitting model.49,50

A multiple-group comparison assessed critical differences between the high and low weight/shape concerns groups, by constraining parameters of the model to be equal.51 First, an initial baseline model was specified in which no constraints were imposed. Next, the factor structure for each group was constrained to be equal and the goodness of fit statistics were examined. Last, a χ2 test of differences determined if the models differed significantly. A nonsignificant χ2 difference would provide support that the factor structure for both groups was equal and testing of the full model could proceed.

To test for moderation, differences between the groups were examined after the addition of the path (Figure 2) to binge eating using structural equation modeling.52 First, the unconstrained model for each group was specified and used as a baseline measure of comparison. Then, the models were constrained by forcing the path coefficient estimate from the high weight/shape concerns group to equal the coefficient for the low weight/shape concerns group. A significant difference in the overall model χ2 would indicate that the relationship between addiction vulnerability and disordered eating was moderated by weight and shape concerns.

3. Results

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. Low and high weight/shape concern groups differed on race/ethnicity (p = .044). Post-hoc single df χ2 contrasts determined that the high weight/shape concerns group had a greater proportion of Caucasians in relation to African Americans compared to the low weight/shape concerns group χ2(1) = 8.76, p =.004. Regression examining the main and interactive effects of race/ethnicity and shape/weight concern on the four main variables (SPSRQ-SR, DERS Total, NEGU, POSU) showed no significant effects of race/ethnicity or race/ethnicity × weight/shape (ps >.05), so race/ethnicity was not included as a covariate in subsequent analyses.

Table 1. Age and Race/Ethnicity Demographic Data.

| Variable | Low W/S Concerns (n=137) | High W/S Concerns (n=135) | Test Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 20.08(1.61) | 20.23(1.73) | t(265)= -.738 |

| Race/Ethnicity | χ2(4) = 9.79* | ||

| Caucasian | 74 (54%) | 94 (69.6%) | |

| African | 31 (22.6%) | 14 (10.4%) | |

| American | |||

| Asian | 13 (9.5%) | 9 (6.7%) | |

| Latino | 6 (4.4%) | 7 (5.2%) | |

| Other | 11 (8.0%) | 9 (6.7%) |

Note. W/S Concerns = Weight/Shape Concerns.

p <.05

Means and standard deviations of the main variables of interest by high versus low weight/shape concerns are presented in Table 2. Differences between the high and low weight/shape concerns groups were found on all variables of interest (all p <.001) except the POSU subscale (p =.073).

Table 2. Mean Responses on Primary Self-Report Measures.

| Variable | Low W/S Concerns (n=137) M (SD) | High W/S Concerns (n=135) M (SD) | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDE-Q | |||

| Weight Subscale | 1.20 (.50) | 4.47 (.79) | -52.428* |

| Shape Subscale | .75 (.51) | 4.74 (.70) | -53.753* |

| # of Binges | .42 (1.59) | 3.61 (4.54) | -7.737* |

| SPSRQ – SR | 66.45 (14.48) | 76.30 (11.51) | -6.205* |

| DERS | 76.07 (20.68) | 97.44 (24.48) | -7.781* |

| UPPS-P | |||

| NEGU | 2.18 (.59) | 2.51 (.58) | -4.696* |

| POSU | 1.81 (.64) | 1.95 (.65) | -1.800 |

Note. W/S Concerns = Weight/Shape Concerns. EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire. SPSRQ – SR = Sensitivity to Punishment and Reward Questionnaire – Sensitivity to Reward Subscale. DERS = Overall Score on the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. UPPS-P = UPPS-P Impulsivity Scale. NEGU = (negative) Urgency subscale of the UPPS-P. POSU = Positive Urgency subscale of the UPPS-P.

p <.001

Table 3 presents the factor loadings for the addiction vulnerability latent factor. All measured variables loaded significantly in both the low and high weight/shape concerns group. Without any model modifications, fit indices were acceptable for both groups: low weight/shape concerns, χ2(2) = 1.549, p > .15, RMSEA = 0.000 (90% CI = 0.0, 0.157), CFI = 1.000; high weight/shape concerns, χ2(2) = 2.865, p > .20, RMSEA = 0.057 (90% CI = 0, 0.19), CFI = 0.995.

Table 3. Factor Loadings of CFA for Low and High Weight/Shape Concerns.

| Low Weight/Shape Concerns (N=137) | High Weight/Shape Concerns (N=135) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Unstandardized | SE | Standardized | Unstandardized | SE | Standardized |

| NEGU | 1.000a | -- | .919 | 1.000a | -- | .866 |

| DERS | 26.095* | 3.389 | .679 | 25.718* | 4.192 | .528 |

| SPSRQ-SR | 9.650* | 2.443 | .358 | 13.679* | 2.096 | .598 |

| POSU | .876* | .104 | .735 | 1.061* | .123 | .817 |

Note. SPSRQ – SR = Sensitivity to Punishment and Reward Questionnaire – Sensitivity to Reward Subscale. DERS = Overall Score on the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. NEGU = (negative) Urgency subscale of the UPPS-P. POSU = Positive Urgency subscale of the UPPS-P.

p <.001 (2-tailed).

Not tested for statistical significance.

To compare the factor structure between the two groups, a CFA multiple-group model without equality constraints was conducted. Initially, all indicators still loaded significantly on the latent factor but fit statistics were not acceptable. After conducting measurement model tests, allowing the intercepts to vary freely for the SPSRQ-SR, DERS, and POSU indicators produced significant improvements to the chi-square fit and produced a model with good fit: χ2(7) = 6.954, p > .40, RMSEA = 0.000 (90% CI = 0.0, 0.105), CFI = 1.000. Next, a model in which the factor structure was constrained to be equal among the groups resulted in a non-significant decrement in fit: χ2(8) = 6.964, p = 5405, RMSEA = 0.000 (90% CI = 0.000, 0.092), CFI = 1.000; Δχ2(1) = .010, p >.05. Thus, we concluded that the factor structure for the low and high weight/shape concerns groups was equivalent.

3.3. Moderation of Weight and Shape

The final model added a predictive path from the latent factor, addiction vulnerability to binge eating and demonstrated excellent fit: χ2(13) = 13.07, p >.40; RMSEA = 0.006 (90% CI = 0.0, 0.085), CFI = 1.000. Next, the path between addiction vulnerability and binge eating of the low group was constrained to be equal to that of the high group. This resulted in a significant decrement of fit: χ2(14) = 19.86, p >.10, RMSEA = 0.055 (90% CI = 0.0, 0.107), CFI = 0.983; Δχ2(1) = 6.79, p <.05. The path coefficients (see Table 4) demonstrated that the relationship between addiction vulnerability and binge eating was significant in the high weight/shape group but only marginally significant in the low weight/shape group, providing support for moderation.

Table 4. Path Coefficients for both Weight/Shape Concerns Groups in Full Path Model.

| # of Binges | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Group | Unstandardized | SE | Significance | Standardized |

| Low Weight/Shape Concerns | .509 | .273 | .062 | .169 |

| High Weight/Shape Concerns | 2.616 | .753 | .001 | .307 |

4.0 Discussion

This study is the first to explore the proposed model (Figure 2) which posits 1) that the three putative addictive mechanisms15 (impaired reward/motivation processing, affect regulation, and impulsivity) underlie addiction vulnerability and 2) weight/shape concerns moderate the relation between addiction vulnerability and binge eating. As hypothesized, the three mechanisms loaded onto addiction vulnerability and the relation between addiction vulnerability and binge eating was moderated by weight/shape concerns. These preliminary findings support the proposed model and highlight commonalities of EDs and addiction.

In accordance with previous research, these results reveal that greater reward sensitivity,18,40 emotion dysregulation,30 and urgency37 were found among the high weight/shape concerns group (i.e., the group most likely to engage in binge eating). Previous research has demonstrated similar dysfunction in these three constructs in individuals with addictions.53-55 Prior research has often explored these constructs separately; however, this study provides evidence that the three functional impairments15 identified in addiction are concurrently present among individuals who binge eat. These results highlight the importance of examining the construct of addiction vulnerability, which may account for the contributions of reward sensitivity, emotion regulation, and urgency, to the development of disordered eating and addictive behaviors. These impairments have been identified in a number of psychological disorders56,57 and although they are labeled as distinct constructs, they are interrelated, involve overlapping neurocircuitry,14,20,39,40 and may affect one another. For instance, it is very difficult to inhibit behavior (i.e., not act impulsively) when something is extremely rewarding (high reward sensitivity), and/or engaging in the behavior can help escape negative affect (deficits in emotion regulation).15 The definition of urgency further demonstrates the interconnectedness: mood-based (positive or negative) rash action, encompassing affective and behavioral impulsivity.43 This study further demonstrated the interrelatedness of these constructs by the significant factor loadings on all four facets found among both the low and high weight/shape concerns groups.

Advances in the understanding of the biological basis of eating and addictive disorders have identified common genetic and neurological underpinnings.21,22,39,58 Specifically, research suggests that the reward system, modulated by dopamine, is hyperstimulated by highly palatable food or drugs which results in heightened reward responses and manifests as poor impulse control.5,6,40 Impairments found in the neurocircuitry suggest that deficits may persist after recovery;21,40 however, longitudinal studies are needed to discern whether these impairments are present prior to the disorder or if they are caused by the disorder. There remains debate12 as to whether reward dysfunction is characterized by an innate hyposensitivity to reward13 or a hypersensitivity to reward.14 However, some argue that the hypersensitivity to the specific rewarding cues (e.g., drugs or food) is caused by a general hyposensitivity to reward.59,60 Taken together, debate remains regarding the underlying causes of the reward dysfunction (e.g., hypo- vs. hypersensitivity) but there is consensus that the reward dysfunction leads to similar negative consequences (i.e., overuse of substance).12-14

Although many similarities exist, it is important to identify what might differentiate eating and addictive disorders. Current results demonstrate that weight and shape concerns moderate the relationship between addiction vulnerability and binge eating. EDs are characterized by extreme weight and shape concerns1 and although not reflected in the diagnostic criteria, individuals with BED also demonstrate these concerns.41 This study provides further evidence that weight and shape concerns may uniquely characterize the development of disordered eating, although future studies must directly demonstrate the absence of weight and shape concerns among individuals with drug addiction without comorbid ED pathology.

Clinical implications of these findings may include moving towards developing more transdiagnostic treatments that target overlapping impairments. The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders exemplifies this belief and aims to treat multiple disorders and comorbidities using one treatment by addressing common underlying factors related to emotional dysfunction.61 Thus, developing treatments around other overlapping impairments such as high levels of urgency and reward dysfunction may be warranted.

4.1 Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

This study builds upon the existent literature on the relationship between disordered eating and reward sensitivity, affect regulation, and impulsivity by concurrently examining the integrative relationships between these constructs and disordered eating. The proposed model provides a solid framework to develop and test future hypotheses. Study limitations include a predominately Caucasian female undergraduate sample. Males were excluded as weight/shape concerns are less understood in males; however, future studies should explore whether similar relations are found in males. In addition, formal diagnostic information was not gathered and future studies of the predictive value of this model with BED or BN diagnoses are needed. Only binge eating was examined in this study as this is the most prevalent of ED behaviors.2 However, examining food restriction and compensatory behaviors (e.g. vomiting) would test if this model predicts to a wider range of disordered eating behaviors. Furthermore, the current study focused specifically on disordered eating. Future studies are needed to examine these constructs collectively in both ED and substance use populations to further confirm this model. Finally, additional research should be aimed at identifying other factors that interact with addiction vulnerability to dictate what psychopathology might likely develop.

4.2 Conclusions

This study is the first to demonstrate that weight and shape concerns moderate the relation between addiction vulnerability and binge eating. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the three putative mechanisms commonly identified with addiction are shared with individuals who binge eat. Accordingly, this study provides preliminary evidence of a proposed model highlighting the shared commonalities between EDs and addiction. This study only examined these mechanisms with regards to binge eating behavior. Future studies should continue to evaluate this model comparing individuals with addiction, EDs, and comorbid addiction and EDs to validate this model in a clinical sample.

Research Highlights.

We examined a proposed model of “addiction vulnerability” in binge eating behavior

We explored specific putative commonalities between eating disorders and addictions

Reward, affect, and cognitive processes loaded on the addiction vulnerability factor

Weight and shape concerns moderated binge eating and addiction vulnerability

Acknowledgments

DME was funded by a grant award by the National Institutes of Health (T32HL007456 – Dr. Denise Wilfley) while writing this manuscript. The funding source had no input on the conduct of the research study. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the funding source. The authors would like to thank Brittany Matheson and Ethan Ganot for their copyediting support.

Footnotes

Although much of the literature on addictions is related to substances, wherever available, literature examining behavioral addictions and these constructs were utilized.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington DC: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The Prevalence and Correlates of Eating Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell JE. Medical comorbidity and medical complications associated with binge-eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2015 doi: 10.1002/eat.22452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stice E, Marti CN, Rohde P. Prevalence, Incidence, Impairment, and Course of the Proposed DSM-5 Eating Disorder Diagnoses in an 8-Year Prospective Community Study of Young Women. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2013;122(2):445–457. doi: 10.1037/a0030679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis CA, Levitan RD, Reid C, et al. Dopamine for “Wanting” and Opioids for “Liking”: A Comparison of Obese Adults With and Without Binge Eating. Obesity. 2009;17(6):1220–1225. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avena NM, Bocarsly ME. Dysregulation of brain reward systems in eating disorders: Neurochemical information from animal models of binge eating, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63(1):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis C. Compulsive Overeating as an Addictive Behavior: Overlap Between Food Addiction and Binge Eating Disorder. Curr Obes Rep. 2013;2(2):171–178. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold MS, Frost-Pineda K, Jacobs WS. Overeating, binge eating, and eating disorders as addictions. Psychiatric Annals. 2003;33(2):117. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassin SE, von Ranson KM. Is binge eating experienced as an addiction? Appetite. 2007;49(3):687–690. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson GT. Eating disorders, obesity and addiction. European Eating Disorders Review. 2010;18(5):341–351. doi: 10.1002/erv.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulte EM, Grilo CM, Gearhardt AN. Shared and unique mechanisms underlying binge eating disorder and addictive disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;44:125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blum K, Braverman ER, Holder JM, et al. The Reward Deficiency Syndrome: A Biogenetic Model for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Impulsive, Addictive and Compulsive Behaviors. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(sup1):1–112. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10736099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The psychology and neurobiology of addiction: an incentive–sensitization view. Addiction. 2000;95:91–117. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman A. Neurobiology of addiction: An integrative review. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;75(1):266–322. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dissabandara LO, Loxton NJ, Dias SR, Dodd PR, Daglish M, Stadlin A. Dependent heroin use and associated risky behaviour: The role of rash impulsiveness and reward sensitivity. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens L, Verdejo-García A, Roeyers H, Goudriaan AE, Vanderplasschen W. Delay Discounting, Treatment Motivation and Treatment Retention Among Substance-Dependent Individuals Attending an in Inpatient Detoxification Program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;49:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison A, O'Brien N, Lopez C, Treasure J. Sensitivity to reward and punishment in eating disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2010;177(1–2):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schienle A, Schäfer A, Hermann A, Vaitl D. Binge-Eating Disorder: Reward Sensitivity and Brain Activation to Images of Food. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(8):654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis C, Patte K, Curtis C, Reid C. Immediate pleasures and future consequences. A neuropsychological study of binge eating and obesity. Appetite. 2010;54(1):208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volkow Nora D, Morales M. The Brain on Drugs: From Reward to Addiction. Cell. 2015;162(4):712–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis C, Levitan RD, Yilmaz Z, Kaplan AS, Carter JC, Kennedy JL. Binge eating disorder and the dopamine D2 receptor: Genotypes and sub-phenotypes. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2012;38(2):328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gratz K, Roemer L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(1):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khantzian EJ. The Self-Medication Hypothesis of Substance Use Disorders: A Reconsideration and Recent Applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, M MR, Fiore MC. Addictionmotivation reformulated:An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111(1):33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leehr EJ, Krohmer K, Schag K, Dresler T, Zipfel S, Giel KE. Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity - a systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015;49:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grilo CM, Shiffman S, Carter-Campbell JT. Binge eating antecedents in normal-weight nonpurging females: Is there consistency? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(3):239–249. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199411)16:3<239::aid-eat2260160304>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corstorphine E. Cognitive–emotional–behavioural therapy for the eating disorders: Working with beliefs about emotions. European Eating Disorders Review. 2006;14(6):448–461. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorberg FA, Lyvers M. Negative Mood Regulation (NMR) expectancies, mood, and affect intensity among clients in substance disorder treatment facilities. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(5):811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brockmeyer T, Skunde M, Wu M, et al. Difficulties in emotion regulation across the spectrum of eating disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2014;55(3):565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierrehumbert B, Bader M, Miljkovitch R, Mazet P, Amar M, Halfon O. Strategies of emotion regulation in adolescents and young adults with substance dependence or eating disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2002;9(6):384–394. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawe S, Loxton NJ. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28(3):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, Cyders MA. The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior (Technical Report) West Lafayette: Purdue University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petry NM. Substance abuse, pathological gambling, and impulsiveness. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63(1):29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson M, Pearce E, Engel S, Wonderlich S. Cognitive Control Moderates Relations Between Impulsivity and Bulimic Symptoms. Cogn Ther Res. 2009 Aug 01;33(4):356–367. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svaldi J, Naumann E, Trentowska M, Schmitz F. General and food-specific inhibitory deficits in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2014;47(5):534–542. doi: 10.1002/eat.22260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer S, Smith GT, Cyders MA. Another look at impulsivity: A meta-analytic review comparing specific dispositions to rash action in their relationship to bulimic symptoms. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(8):1413–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berg JM, Latzman RD, Bliwise NG, Lilienfeld SO. Parsing the Heterogeneity of Impulsivity: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Behavioral Implications of the UPPS for Psychopathology. Psychological Assessment. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pas0000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Telang F, Baler R. Addiction: Decreased reward sensitivity and increased expectation sensitivity conspire to overwhelm the brain's control circuit. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2010;32(9):748–755. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wierenga CE, Ely A, Bischoff-Grethe A, Bailer UF, Simmons AN, Kaye WH. Are Extremes of Consumption in Eating Disorders Related to an Altered Balance between Reward and Inhibition? Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;8:410. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldschmidt AB, Hilbert A, Manwaring JL, et al. The significance of overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caseras X, Àvila C, Torrubia R. The measurement of individual differences in Behavioural Inhibition and Behavioural Activation Systems: a comparison of personality scales. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34(6):999–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(4):839–850. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJV. Temporal stability of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36(2):195–203. doi: 10.1002/eat.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJV. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42(5):551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(4):363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torrubia R, Ávila C, Moltó J, Caseras X. The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray's anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31(6):837–862. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mplus User's Guide. Sixth. Los Angeles,CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological methods. 1996;1(2):130. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelinng. 3rd. New York: Guilford; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fox HC, Axelrod SR, Paliwal P, Sleeper J, Sinha R. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control during cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89(2–3):298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The Role of Personality Dispositions to Risky Behavior in Predicting First Year College Drinking. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2009;104(2):193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loxton NJ, Dawe S. How do dysfunctional eating and hazardous drinking women perform on behavioural measures of reward and punishment sensitivity? Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(6):1163–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Zutphen L, Siep N, Jacob GA, Goebel R, Arntz A. Emotional sensitivity, emotion regulation and impulsivity in borderline personality disorder: A critical review of fMRI studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015;51:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Umemoto A, Lukie C, Kerns K, Müller U, Holroyd C. Impaired reward processing by anterior cingulate cortex in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2014;14(2):698–714. doi: 10.3758/s13415-014-0298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frank GW. Recent Advances in Neuroimaging to Model Eating Disorder Neurobiology. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(4):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0559-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koob GF, Moal ML. Drug Abuse: Hedonic Homeostatic Dysregulation. Science. 1997;278(5335):52–58. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Di Chiara G, Bassareo V. Reward system and addiction: what dopamine does and doesn't do. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2007;7(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Boisseau CL, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders: Protocol Development and Initial Outcome Data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]