SUMMARY

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to explore and describe Khmer mothers’ understanding of HBV and HPV prevention as well as their perception of parenting on health and health education of their daughters in the US.

Methods

The qualitative pilot study guided by the revised Network Episode Model and informed by ethnographic analysis and community-based purposive sampling method were used. Face-to-face audiotaped interviews with eight Khmer mothers were conducted by bilingual female middle-aged community health leaders who spoke Khmer.

Results

The findings revealed that Khmer mothers clearly lacked knowledge about HBV and HPV infection prevention and had difficulty understanding and educating their daughters about health behavior, especially on sex-related topics. The findings showed that histo-sociocultural factors are integrated with the individual factor, and these factors influenced the HBV and HPV knowledge and perspective of Khmer mothers’ parenting.

Conclusion

The study suggests that situation-specific conceptual and methodological approaches that take into account the uniqueness of the sociocultural context of CAs is a novel method for identifying factors that are significant in shaping the perception of Khmer mothers’ health education related to HBV and HPV prevention among their daughters. The communication between mother and daughter about sex and the risk involved in contracting HBV and HPV has been limited, partly because it is seen as a “taboo subject” and partly because mothers think that schools educate their children regarding sexuality and health.

Keywords: Cambodian American, hepatitis B virus, human papillomavirus, knowledge, parenting

Introduction

Khmer or Cambodian Americans (CAs) are at lower risk for the top cancer diagnoses experienced by most Americans, but they experience a significantly higher burden of liver and cervical cancers as well as higher incidences of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) infections [9,17,18,22,23,32,42]. Though the transmission modes of HIV, HBV, and HPV are similar, via infected blood or sexual contact, HBV is 100 times more infectious than HIV is [18]. While researchers, policy-makers, practitioners, and funders have made significant progress in prioritizing the prevention and treatment of HIV infection, far less attention has been given to HBV and HPV infectious diseases which disproportionally affect Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Both HBV and HPV are primary causes of liver and cervical cancer, but are vaccine preventable (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004; [7,21]). HBV and HPV vaccination rates for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have been low. However, there is limited information relevant to vaccination and cancer prevention behavior among this population (Euler, 1998; [27,28]). In particular, the social and cultural factors associated with HBV and HPV infection and cancer prevention behaviors among CAs remain largely unexplored.

Studies have documented that parents strongly influence their children’s health and health behavior. Mothers, in particular, are widely acknowledged to be their children’s primary health educators [10,15,34]. Specifically with regard to vaccination decisions, adolescents typically follow decisions of their parents, due to their legal custody, greater knowledge, and financial means. In studies with White, Black, and Hispanic/Latino adolescent daughters, for example, mothers with higher levels of knowledge about their children’s health and those who communicated about vaccinations and sex were associated with higher vaccination rates and fewer episodes of unprotected sexual intercourse for their daughters [1,10,15,31,34]. Health information passed from mother to daughter is influenced by sociocultural factors as well as individual parenting styles. Moreover, the mother’s own access to health care is a critical factor for the health-related decisions and actions of her children [2]. However, little is known about Khmer mothers’ perceptions and understanding about HBV and HPV infection prevention for themselves and their daughters as well as what roles they play in parenting their daughters on health-related education topics such as vaccination and sex. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore and describe Khmer mothers’ understanding of HBV and HPV prevention as well as their perceptions of parenting on health and health education of their daughters in the US.

The way people respond to HBV is both a sociocultural process and the result of individual experiences [25,26]. Based upon these considerations, the theoretical framework guiding this research study is the revised Network-Episode Model (NEM) [36]. The NEM is used to conceptualize how Khmer mothers come to recognize and respond to health problems and perceive their parenting. Perception of parenting behavior in the revised NEM is conceptualized as a context-bound, interactive social process that is shaped by specific sociocultural contexts and social networks rather than by a deterministic response. In this study, sociocultural context is defined as personal characteristics, including demographic, social and cultures factors and is the background for people’s lives. Sociocultural context influences whether individuals recognize their HBV and HPV infection and seek for vaccination [26]. Individual factor refers to knowledge and beliefs that are central to the way individuals construct a diagnosis, shape illness experiences, and plan for HBV and HPV vaccination [26,45]. The revised NEM provides a framework to explore and describe individual factors (Khmer mothers’ understanding of HPV and HBV prevention) and sociocultural factors, and to explain perceptions of parenting in the context of interpersonal interactions within Khmer social networks.

Method

The data reported in this manuscript is a part of a larger study to develop and test the multifactorial quantitative instrument. The larger study utilized a four standardized stages: (a) qualitative interviews to guide development of the quantitative survey instrument; (b) item selection for the survey; (c) pretesting of the survey; (d) administration of the full-scale survey. However, the manuscript only addresses qualitative interviews. The domains of qualitative interview were the sociocultural context of the respondents, their health belief and health knowledge as well as parenting practices about health education of their children. These interviews informed the development of theory-based and culturally-relevant measures. The study used a descriptive qualitative design guided by the revised NEM and informed by ethnographic analysis. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Target population of CAs in Massachusetts

Asian Americans are the fastest growing minority in the US, increasing from 0.5% in 1960 to 5.6% in 2010 and projected to reach 10% by 2050 [6]. Massachusetts ranks 10th among all the states in terms of its Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders population (4.9%). It has one of the largest Southeast Asian populations in the US. The population of CAs in Massachusetts is 24,172 (2005 American Community Survey), the majority of whom reside in Lowell (Census Bureau). The 2010 Census reported that the CA population in Lowell grew by 36.7% from 2000 to 2010 (Census Bureau). Of the more than 3,100 students enrolled in grades 9 through 12 at Lowell High School. For example, 30%, or approximately 1,000 students, are CAs. Lowell has the second largest CA population (14,470), after Long Beach, California (19,998). However, the per capita CA population in Lowell, 13% (Long Beach is 4%) by 2010 Census in the US is the highest of any city in the US.

CAs began arriving in the US as refugees after surviving the brutal rule of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia from 1975 to 1979 when 1.7 million—close to 30% of the country’s population—died from starvation, execution, torture, forced labor, and illness [5,14]. More than 70% of CAs are immigrants, many of whom face the task of developing networks and social relations in their new environment with members of their ethnic group as well as with the mainstream population. The 2010 U.S. Census indicated that CAs had the highest poverty rate and the highest proportion of linguistic isolation among all Asian American groups that year; over 90% spoke Khmer at home ([6], Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004).

Sampling

A community-based purposive sampling method was used to ensure maximum variation in education, length of residence in the US, age, and level of English with three inclusion criteria: self-identified as Cambodian or Khmer, mother/legal guardian of girls 12–20 years old, and ability to speak or read Khmer or English. The sampling adequacy was ensured with evidence of saturation and replication [33] to account for all selected domains of sociocultural context, health knowledge and beliefs, and parenting on health education.

Training community health leaders (CHLs) as Interviewers

Middle aged female CHL interviewers were selected based upon their understanding of the health beliefs and sociocultural background of CAs and because they have worked as community health workers or patient navigators for the targeted populations. Funding was provided to CHL interviewers to be certified via the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative program for research ethics education. Moreover, to enhance CHLs’ ability to understand the HBV and HCV problem in the CA community, a series of five CHL training sessions were offered to enable the data collectors to educate and support eligible research participants make informed decisions for participation in the study. Trainings also provided CHL interviewers with structured settings for sharing relevant information, experiences, concerns, and recommendations with the team’s academic researchers. CHLs shared their cultural, linguistic, and community practitioner knowledge and reflections to guide the development and piloting of interview protocols with CA mothers by advising the researchers on both what and how questions should be asked and regarding the most culturally sensitive and appropriate ways to conduct the interviews with CA middle-aged women. During the training sessions and throughout the study, CHL interviewers were also informed of the importance of keeping any information obtained from the research confidential and they were asked to reassure the participants of this fact.

Interview process

Interview guides and interview questions were developed with Khmer CHLs and the interview protocol was standardized. The interview begin with general questions and move to specific questions and then additional structural and comparison questions. The CA mothers were asked about their perceptions and knowledge of HBV and HPV infection, vaccination, and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in relation to themselves and their daughters, as well as what and how they educate their daughters on health and sexuality. The interviewer tailored questions to the interviewee’s responses. An example of one question was, “Please discuss what you know about how you (your daughter) can get hepatitis B virus infection (or HPV). What does it mean to you?” “You stated that your English-speaking daughter knows more. Please tell me more about that.” Eight interviews of 20–60 minutes were conducted by bilingual CHL interviewers and audiotaped. Care was taken to conduct the interviews with mothers privately at a time and place convenient to participants wherever they wished, such as in homes, in a quiet corner of an ethnic restaurant or in a room of an ethnic community health center. The CHL interviewers met the participants anywhere they felt safe and where it was quiet and private enough for an interview.

All but two of the participating CA mothers preferred Khmer language for the interview, though some CA mothers used English words when they spoke about medical terminology and the U.S. health care system. Some also used only Khmer language to articulate specific cultural issues and topics related to health belief. Field notes, reflections, and ideas of the interviewee were compiled by the interviewer.

Data analysis

Interviews conducted in Khmer were audio translated into English by bilingual CHL interviewers, and then the English translated audiotapes were transcribed. Theory-guided content analysis methods based on the revised NEM were used to examine Khmer mothers’ perception and knowledge about HBV and HPV infection and the role Khmer mothers play in health and health behavior of their daughters in the US.

Discourse analysis [44] based on the interviews was used to better understand individual Khmer mother’s knowledge, health belief, and sociocultural factor as well as perceptions of their role of parenting on health and health education for their daughters within their sociocultural contexts. After independent coding by three key investigators, an open coding meeting with coders, a Khmer consultant, CHLs, and Khmer RAs was conducted to share the coders’ perspectives and approaches to the data and to determine common and emerging themes and issues as well as differences.

To optimize validity (trustworthiness) and reliability (exhaustiveness), we sought to minimize discrepancies between participants’ views and the investigators’ interpretations. Trustworthiness of the findings was ensured by taking the following steps: (a) after several readings, the transcripts were coded using recurring words or phrases. This was done independently by three key investigators (H.L., P.K., S.T.); (b) an open coding meeting with coders, a Khmer consultant (P.C.), CHL (S.P.), and RA (S.S.A.), was conducted to debrief and share the coders’ s perspectives and approaches to the data; (c) to check accuracy of the data, member checking with CHL interviewers and two participants was used [13,29]. The identified codes and categories in English were translated into Khmer, and Khmer researchers and CHLs reviewed and discussed the qualitative data, including codes and categories. In addition, they helped non-Khmer researchers to clarify ambiguous or poorly understood information uncovered during the individual coding process.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the eight CA mothers are given in Table 1. All participants were first-generation Khmer immigrants; the majority spoke Khmer at home; and four of the participants completed at least middle-school education either in Cambodia or the US which reflected the demographic characteristics of CAs [6]. The participants ranged in age from 34 to 51 years and their spouses are all Khmers. Two participants reported that they spoke English well or fluently. All reported having a regular source of health care. Major findings revealed that participants were uninformed and had low levels of knowledge about HBV, HPV, liver and cervical cancer. The findings showed that three factors, health belief in historical context, misinformed or uninformed, and sociocultural contexts, were related to Khmer mothers’ perceptions of parenting on health and health education of their daughters in the US. Thus, the use of the revised NEM provided a new insight to explaining how Khmer mothers came to recognize their parenting roles and responded to their daughters’ health and health education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants (N = 8).

| Variables | Total (N = 8)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| No. | M ± SD or % | |

| Age (34–51 yrs) | 8 | 42.1 ± 5.5 |

| Native country | ||

| Cambodia | 8 | 100.0 |

| Percent of life in the US | ||

| <50% | 4 | 50.0 |

| ≥50% | 4 | 50.0 |

| Year moved to the US | ||

| 1980s | 4 | 50.0 |

| 1990s | 2 | 25.0 |

| 2000s | 2 | 25.0 |

| Reason for moving (n = 7) | ||

| Refugee status | 4 | 57.1 |

| Join family | 3 | 42.9 |

| Ethnicity of spouse (n = 7) | ||

| Khmer | 5 | 83.3 |

| Did not answer | 2 | 16.7 |

| No. of daughters (n = 7) | ||

| 1 | 4 | 57.1 |

| 2 | 2 | 28.6 |

| 3 | 1 | 14.3 |

| Highest education in Cambodia or the US | ||

| Elementary school (grade K–6) dropout | 1 | 12.5 |

| Middle school (grade 7–9) dropout | 1 | 12.5 |

| High School (grade 10–12) dropout | 1 | 12.5 |

| High School (grade 10–12) completed | 4 | 50.0 |

| University or 4-year college graduate/dropout | 1 | 12.5 |

| Have a regular source of medical care | ||

| Yes | 8 | 100.0 |

| Type of medical facility | ||

| Private doctor’s office | 3 | 37.5 |

| Community health center or country clinic | 4 | 50.0 |

| Private doctor’s office and community health center or country clinic | 1 | 12.5 |

| Speak English | ||

| Not at all | 1 | 12.5 |

| A little or somewhat | 5 | 62.5 |

| Well or fluently | 2 | 25.0 |

| Language at Home | ||

| Khmer | 4 | 50.0 |

| Both English & Khmer | 4 | 50.0 |

Health beliefs in historical context

Most participants linked their health beliefs and health condition to their experiences under the Khmer Rouge and refugee camps. The participants shared their overarching belief that their health conditions and circumstances were profoundly shaped by their own or their families’ living situations under Khmer Rouge and in the refugee camps three decades earlier. Although questions about past history were not asked, the participants, nevertheless, associated their experiences and social contexts under the Khmer Rouge and in the refugee camps with their current health and health behavior in several important ways. In relation to the HBV vaccination, participants thought that they were immune and free from any disease if they were approved and allowed to move to the US. For example, the following translated and transcribed dialogue between an interviewer and interviewee revealed this assumption:

Interviewee: “But before coming to the United States, they all examined us already.”

Interviewer: “Yeah. That’s true.”

Interviewee: “They gave all kinds of shots, all kinds of medications, they stripped us down naked already.” “You know, they detoxified our whole body, we are detoxified.”

Interviewer: “Detoxified already. Everything’s been done (laughing).”

Informants also linked dirty environments under the Khmer Rouge and in the refugee camps with HBV and HPV infection, especially the lack of clean water to drink and to keep good hygiene. As one mother stated, “Yes, there are a lot of cases due to poor perineal hygiene during Khmer rouge.” They thought that poor hygiene was a risk factor for cervical cancer and drinking unclean water was a risk factor for HBV infection.

Regarding questions relating to the sexually transmitted nature of the viruses, two Khmer mothers shared these views: “The younger one’s still very young and single. So I never ask such thing (sex-related topics) but I stress on abstinence until marriage,” and “I told her to perform thorough hygiene to prevent any bacteria.” Another added, “I just never talked to her about sex. I just want her to refrain from having sex until she’s 18,” or “It can be caused by polygamy.” Some mothers, for example, believed that people gets sexually transmitted diseases if they go outside the marriage. This belief also serves to stigmatize any individual with HBV and HPV as having been unfaithful or promiscuous.

Low health knowledge: I have never heard of it

Participants were asked specifically what they knew about HBV or HPV infection or if they had heard of it. The findings suggest that participants’ knowledge about HBV and HPV fit into two categories—those who had no knowledge and those who possessed little knowledge. There were only a few instances in which the participants reported knowing anything about HBV or HPV infection or vaccinations. The majority of participants did not know anything about HBV and HPV or had never heard of it.

Regarding HPV, most participants had no knowledge, stating, for example, “I don’t even know how to say all these disease let alone telling the doctor,” and “I never heard of it until today.” When one mother asked, “What is it called in Khmer?” the interviewer provided the explanation in Khmer, and the participant interpreted it in general terms as “womb disease” because there is no Khmer term for cervix or HPV. When asked about causes for cervical cancer, one participant responded, “My husband passed away so I don’t think there is anything wrong with me.” Another stated, “I am feeling fine—there is no discharge.” The data revealed that the participants not only have a low level of knowledge but also were not “informed”.

Regarding HBV, one participant explained, “I think you have to use separate eating utensils from the one infected with hepatitis to avoid getting infected.” Another stated, “We have to wash hands before eating, no consuming alcohol too much.” Another added, “Clean, always clean your hands.” Still another wondered, “Through sexual intercourse, saliva or through, maybe food … dirty water, maybe, I don’t know.” These responses exemplify a low level of knowledge about HBV, HPV, liver and cervical cancer for Khmer mothers in this study.

Sociocultural contexts

The findings of this study revealed that Khmer mothers’ health behavior and perceptions of parenting are formed in relation to their dual Cambodian-based and U.S.-based sociocultural contexts. They are challenged in their traditional perceptions of health communication and parenting by the different educational and health care systems in the US that conflict with traditional beliefs and social practices in Cambodia. Moreover, aside from language barriers, Khmer immigrant mothers have minimal formal schooling. The data suggests that Khmer mothers doubt their ability to advise their English-speaking daughters.

For example, Khmer mothers typically thought that their English-speaking daughters educated in the US were more knowledgeable than they themselves were. One explained, “My generation, nobody was talking about it at the school. Plus, lack of English,” and “My children go to school and get it from school, they find out themselves.” Another added, “My kid’s generation is more educated about hygiene and more issues, too; she will be educating about that department.”

In U.S. health care settings, Khmer mothers saw themselves as passive observers rather than being responsible or knowledgeable guides for their daughters’ health and health care. As one mother stated, “In doctor’s office, they talk in English, so I do not really understand. I do not know much of medical stuff. I guess that I do not need to know what they are discussing.” Another mother recalled, “I was kept out of the exam room since she turned 11 or 12 years old. I think [doctors] have this vaccine for 12 or 13 years old girl to protect the womb ulcers, it is a new rule that just [came] out.” The mothers perceived that these dynamics that distanced them from health care providers in relation to their daughters’ health care in the US meant that their parenting role was not valued or needed.

Perception of parenting on health and health education

Parenting, in this case, represents the mothers’ perceptions about their ability to educate their children or communicate with them about health and sex-related topics. Our data suggested that Khmer mothers lacked an understanding of their daughters’ health behaviors, and perception of the role of parenting on health and health education are made within in the context of interpersonal interactions within their social contexts and interactions between individual factors and sociocultural factors. Data indicated that most mothers did not talk with their children about health and sex. Mothers’ messages fell into the following categories: (a) avoiding sex; (b) focusing on education; (c) keeping good hygiene.

Specifically, most mothers felt very uncomfortable and confused about their roles. One participant stated, “I only teach them how to function appropriately in the society, focus on school and career, not on sexual activity, and the most important thing is to finish school.” Another participant clearly describes the complexity and challenge of parenting: “I do not know if that’s a good thing or bad thing being like what we are. I do not know, to me, I still do not feel comfortable talking about it.” The last recurring theme concerning parenting on health and health education was their perception that hygiene was the most important factor for prevention of disease and infection and that poor hygiene was a risk factor for cervical cancer. Another mother responded to the question about women’s health education as, “I often asked her how her periods are. I teach her how to clean her private area.” However, when asked about protected sex, she responded this way, “No, she is too young. I just want her to perform thorough hygiene, especially when she has period.”

Communication between mothers and daughters about sex and the risks involved in HBV and HPV was limited, partly because there were gaps between immigrant Khmer mothers and their children who were raised and educated in the US, and partly because the subject itself was considered taboo. One mother explained, “I have never talked about it … my mom never shared those things … it makes me feel uncomfortable to talk with my daughter too.” Another agreed, “When it comes to S-E-X department, it is a closed door conversation, I said to them, ‘Look, stay away from S-E-X until you finish school.”

Most participants did not directly use the term, “sex” during the interview process. This was not surprising, given shared cultural values of modesty. However, one younger mother in her 30s, did answer differently—showing some diversity of perspective and experience among the participants. Interviewed in English, she shared her process regarding sex education with her daughter: “I gave her the information, like the educational material. She is more comfortable texting to me versus sits in front and talks to me directly. She feels uncomfortable. So we just text. If she has questions, I give her the information. If she has still questions, she will come back texting me, ‘Mom, what is this? What is that?’ but [just not directly].”

Discussion

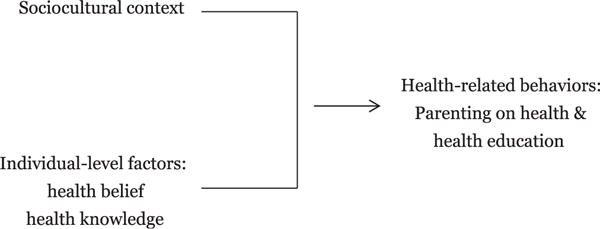

Qualitative findings in this study revealed that Khmer mothers’ parenting regarding health education and health actions for their daughters as well as their own health practice reflected an interactive, relational process between individual health beliefs and knowledge with sociocultural factors (Figure 1). In addition, the mothers’ approaches to health education with their daughters were influenced by sociocultural values in their current US-based social context as well as their Cambodian and Thai refugee camp sociohistorical contexts and by their own mothers’ parenting styles. Our findings clarified the limited role that Khmer mothers have in health decision-making and in health education, especially sexual education, with their daughters. However, qualitative findings of this study also challenge stereotypic assumptions of monolithic cultural beliefs and practices by Khmer mothers, given the clear example of participants who developed alternative strategies to communicate in English on “taboo topics”.

Figure 1.

Situation-specific theory of hepatitis B virus and human papillomavirus prevention- related parenting on health and health education among Cambodian American Mothers.

In terms of HBV and HPV knowledge, it is significant that Khmer mothers overwhelmingly lacked knowledge about HBV and HPV infection, highlighting the importance of education on these vaccine preventable diseases. Findings of prior studies among CAs and Asian Americans also indicate low level of knowledge about HBV and HPV infection [4,11,17,26,28,41,46]. The differences in HBV and HPV vaccination rates exist by country of origin, sociocultural factors such as health insurance, English proficiency, income, education, and knowledge level [3,4,19,26,35,40]. The [16] has issued a report calling for data collection on patient race/ethnicity, and language as a strategy for improving quality of care and reducing health disparities in racial/ethnic minority groups. However, most studies lack or have limited subgroup categorization for Asian Americans, especially CAs, even though Asian Americans are diverse in sociodemographic characteristics and HBV and HPV vaccinations [6,8]. The disease-specific and ethnicity-specific data from this study, however, will be used to develop evidence-based, culturally specific health interventions.

Furthermore, Khmer mothers do not have communication skills to educate their US-educated daughters regarding HBV and HPV prevention behaviors. The problem is four-fold. First, Khmer mothers incorrectly believed that unclean water and poor hygiene caused cervical and liver cancers. Consistent with previous research literature about Southeast Asian women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004; [24,26]), CA women believed cervical cancer is caused by improper hygiene through infection. This belief reflects their experiences in historical and sociocultural contexts of war and forced migration through which they link unclean, post-genocidal environments with disease and refugee camp processing with medicine, immunization, and being “detoxified”. They also were not able to differentiate types of hepatitis and were not able to name different types of immunization, and incorrectly believed that one of the vaccinations they received in the refugee camps was for hepatitis. Second, health education about STDs may be particularly difficult for Khmer mothers to discuss, because of their associating STDs with topics considered taboo in their culture. Hence, they may mistakenly stigmatize individuals with HBV and HPV who fall within a STD group that has historically been associated with social taboos of sex and immorality in Khmer culture. Third, Khmer mothers assumed that their daughters, educated in the US, have more knowledge about health and sexual education than themselves, due to their lack of English proficiency. Their incorrect assumption about U.S. schools and their daughters’ health knowledge is understandable given their direct experience with dynamics of marginalization due to language, culture, race, citizenship, and lack of formal education [26,30,39,43]. Immigrant families typically experience family role-reversal as children learn English faster than their parents and become translators, interpreters, and decision-makers in relation to health care services and settings. Fourth, the data revealed that language barriers facing Khmer mothers and daughters—as well as Khmer families and communities more broadly—relate to more than English language fluency or literacy. There are simply no words in Khmer for certain medical terminologies. For instance, Khmer mothers used the terms in Khmer such as “liver disease” for HBV and “womb ulcer” or “womb cancer” for cervical cancer since there are no Khmer words for these terms. Given these sociolinguistic differences, further studies are needed to address the issues of how mothers communicate with both their daughters and health care providers as well as how researchers collect reliable, meaningful data from CAs on these topics.

Most participants’ initial response to questions about HBV and HPV knowledge were typically, “I do not know,” “I really do not know,” “I was not educated in that field,” or “I’ve heard people talking about them, people having Hep B and cervical cancer, but I haven’t actually encountered them with my own eyes.” The meaning of “I do not know” among Khmers may not mean that they did not know at all, but rather they do not have medical knowledge to understand the topic or do not have personal experiences related to that topic. If, for example, the individual or their family had not been directly infected with these diseases, the participants did not want to mislead the interviewer about their knowledge level. Rather they preferred to wait until they understood more about the meaning of the questions asked. This qualitative finding suggests that the response, “I do not know” might be an important rating component of measures in addition to “yes” or “no” when studying Khmers and that further studies are needed to understand the meanings and significance of the “I don’t know” category of responses.

Furthermore, in several cases, participants directly asked the interviewers to provide additional health information during the interview, such as: “I have a question, for instance, if I am on birth control pills, can it lead to that?” and “I never know anyone infected with it. Do you know someone that has it?” Moreover, it appeared that the interview process gave some of the participants the opportunity for self-reflective moments such as: “I do not know because I have never had one. Since I do not know how it is transmitted, I do not know if I already have it because I never heard of it. How do you know if one is infected with it?” Some Khmer mothers stated that they never before thought about their own or their daughters’ risks of becoming infected with HPV and HBV, and they told the interviewers that they now felt that they could ask their primary care providers to check their HBV status and give the HPV vaccinations to their children. This suggest a potential link between the interview process and the intervention as CA mothers might use the interview process as an opportunity for self-reflection or self-learning; the interview might motivate CA mothers obtain more health information and provide health information to their daughters. As for interview duration, although the interview protocol was standardized, the interviews varied from 20 to 60 minutes and the findings suggest that when participants responded with “I don’t know” to the interview questions the interview took less time.

Our findings in the current study are novel in that using qualitative data in instrument development will allow us to take the next step in developing ethnicity- and disease-tailored community-based health educational programs for CAs. These qualitative data will inform selection and testing of items and language during the instrument development phase of the project. The end goal of the project is to develop a culturally sensitive instrument with good psychometric properties examining CAs’ health experiences and perceptions about HBV and HPV prevention.

The limited transferability of findings stems from a small sample of participants from one geographic areas of the US. Conducting the interviews face-to-face may have resulted in socially desirable responses. However, most participants indicated that they were grateful to learn that professors from the university and their CHLs are interested in knowing more about their health experiences, so they were willing to share their stories. In addition, this study is a part of a larger study on quantitative tool development. Hence, the scope of this article does not provide as extensive detail as would have been appropriate if it had been the sole focus of the research project.

Conclusion

The findings clearly indicate that the majority of participants did not know anything about HBV and HPV prevention and point to the fact that there is an urgent need for providing culturally tailored public health education about HBV and HPV infection among CA communities.

This study suggests that culture-specific conceptual and methodological approaches that take into account the uniqueness of the sociocultural context of CAs are shown to be a novel method for identifying factors that are significant in shaping the perception of Khmer mothers’ health education of HBV and HPV prevention among their daughters. Although, we suspect that many refugee and immigrant mothers as well as fathers may experience similar problems and challenges as they strive to maintain their parenting roles in sociocultural contexts that are so significantly different from their homeland settings, the weight of such issues is especially heavy for under-researched populations that face data disparities in the health fields, such as CAs.

It was assumed that CA mothers knew about their children’s health knowledge and health behaviors. However, our data suggested that CAs lacked an understanding of their daughters’ health behaviors and sexual education. Thus, the accuracy of CA mothers as a source for their children’s health-related data is questionable. Moreover, Khmer mothers mistakenly assume that health education is independently occurring through their daughters’ experiences in U.S. schools. The skills and resources needed by Khmer mothers include regaining their parenting role in the health education and health promotion of their children, improving communication skills with their daughters regarding health education, and gaining accurate knowledge about HBV and HPV risk behaviors and vaccinations for themselves and their daughters.

Further studies are needed to explore the roles that mothers can play in providing information to their daughters on health-related education topics, including vaccination and sexuality as well as effective intercultural communication practices and modes of communication between Khmer mothers and daughters, ranging from dialogue, texting, story-telling, and joint participation in similar or expanded community-based health research and education projects. Further studies to ascertain the knowledge and perspectives of Khmer American children, especially with a focus on communication between mother and daughter as well as parent and children on the subject of sexuality and HBV and HPV prevention behavior are also needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Khmer Student Association at University of Massachusetts Boston and Khmer American Communities, Massachusetts. The works were supported by a Research Grant from the College of Nursing and Health Sciences and a Research Fellowship from Institution for Asian American Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston and by the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA15207-01).

References

- 1.Allen JD, Thus MKD, Shelton RC, Li S, Norman N, Tom L, et al. Parental decision making about the HPV vaccine. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prevention. 2010;19(9):2187–98. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allred NJ, Wooten KG, Kong Y. The association of health insurance and continuous primary care in the medical home on vaccination coverage for 19-to 35-month-old children. Pediatrics. 2007;111:S4–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnack-Tavlaris JL, Garcini LM, Macera CA, Brodine S, Klonoff EA. Human Papillomavirus vaccination awareness and acceptability among US and foreign-born Women living in California. Health Care for Women International. 2014:1–19. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.954702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastani R, Glenn BA, Tsui J, Chang C, Marchand EJ, Taylor VM, et al. Understanding suboptimal human Papilloma vaccine update among ethnic minority girls. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prevention. 2011;20:1463–72. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cambodia Public Health Development. A public health profile of Cambodia. 2008;2008 Retrieved from http://www.workforce.southcentral.nhs.uk/pdf/A_Public_Health_Profile_of_Cambodia.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Census Bureau. The Asian population: 2010. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) Mortality Morbidity Weekly Report. 2014;63:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JY, Diamant AL, Kagawa-Singer M, Pourat N, Wold C. Disaggregating data on Asian and Pacific Islander women to access cancer screening. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen C, Evans AA, London WT, Block J, Conti M, Block T. Underestimation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States of America. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2007;15:12–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dancy B, Crittenden KS, Talashek ML. Mothers’ effectiveness as HIV risk reduction educators for adolescent daughters. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17(1):218–39. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Do H, Seng P, Talbot J, Acorda E, Coronado GD, Taylor VM. HPV vaccine knowledge and belief among Cambodian American parents and community leaders. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2009;10:339–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Euler GL. Have we met the 2000 goals and objectives? What’s next? Asian American Pacific Islanders Journal of Health. 2000;8:113–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology Journal. 1981;29:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heng MB, Key PJ. Cambodian health in transition. British Medical Journal. 1995;311:435–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7002.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutchinson MK, Kahwa E, Waldron N, Brown CH, Hamilton PI, Aiken J, et al. Jamaican mothers’ influences of adolescent girls’ sexual beliefs and behaviors. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2012;44:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. The National Academy Press. 2002 Retrieved from: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=030908265X. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and liver cancer: a national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C 2010. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html. [PubMed]

- 18.Ioannou GN. Hepatitis B virus in the United States: infection, exposure, and immunity rates in a nationally representative survey. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;154:319–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeudin P, Liveright E, Carmen MG, Perkins RB. Race, ethnicity, and income factors impacting Human Papilloma vaccination rates. Clinical Therapeutics. 2014;36:24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S, Lee H, Kiang P, Kalman D, Ziedonis DM. Factors associated with alcohol problems among Asian American college students: gender, ethnicity, smoking and depressed mood. Journal of Substance Use. 2014;19:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koutsky LA, Adult KA, Wheeler CM, Brown DR, Barr E, Alvarez FB, et al. Controlled trial of a human papillomavirus type 16 vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:1645–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowdely KV, Wang CD, Welch S, Roberts H, Brosgard CL. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology. 2012;56:422–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.24804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwong SL, Stewart SL, Aoki CA, Chen MS. Disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma survival among Californians of Asian ancestry, 1988–2007. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prevention. 2010;19(11):2747–57. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam TK, McPhee SJ, Mock J, Wong C, Doan HT, Nguyen T, et al. Encouraging Vietnamese-American women to obtain pap tests through lay health worker outreach and media education. Journal of General International Medicine. 2003;18:516–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee H, Hann H, Yang J, Fawcett J. Recognition and management of HBV infection in a social context. Journal of Cancer Education. 2011;26(3):516–21. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee H, Kiang P, Chea P, Peou S, Tang SS, Yang J, et al. HBV-related health behaviors in a socio-cultural context: perspectives from Khmers and Koreans. Applied Nursing Research. 2014;27:127–32. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H, Kiang P, Watanabe P, Halon P, Shi L, Church DR. Hepatitis B virus infection and immunizations among Asian American college students: infection, exposure, and immunity rate. Journal of American College Health. 2013;6:67–74. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.753891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H, Levin MJ, Kim F, Warner A, Park W. Hepatitis B infection among Korean Americans in Colorado: evidence of the need of serologic testing and vaccination. Hepatitis Monthly. 2008;8:91–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliott MN, Berthold SM, Chun CA. Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. Journal of American Medical Association. 2005;294(5):571–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McRee AL, Reiter PL, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Mother-daughter communication about HPV vaccine. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:314–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller BA, Chu KC, Hankey BF, Ries LAG. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns among specific Asian and Pacific Islander populations in the U.S. Cancer Causes and Control. 2008;19(3):227–56. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morse JM. Strategies for sampling. In: Morse J, editor. Qualitative nursing research: a contemporary dialogue. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publcations; 1991. pp. 117–131. Rev. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy DA, Roberts KJ, Herbeck DM. HIV-positive mothers’ communication about safer sex and STD prevention with their children. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33(2):136–57. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11412158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen GT, Leader AE, Hung WL. Awareness of anti-cancer vaccines among Asian American women with limited English proficiency: an opportunity for improved public health communication. Journal of Cancer Education. 2009;24:280–3. doi: 10.1080/08858190902973127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pescosolido BA. Beyond rational choice: the social dynamics of how people seek help. American Journal of Sociology. 1992;97:1096–138. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pulido MJ, Alvardo EA, Berger W, Nelson A, Todoroff C. Vaccinating Asian Pacific Islander children against hepatitis B: ethnic specific influence and barriers. Asian American Pacific Islander Journal of Health. 2001;9:211–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Presto S. Cambodian immigrants make impact on city in US Northeast. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.voanews.com/english/archive/2005-05/2005-05-04-voa72.cfm.

- 39.Tang SSL. Challenges of policy and practice in under-resourced Asian American communities: analyzing public education, health, and development issues with Cambodian American women. Asian American Law Journal. 2008;15:153–75. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor VM, Talbot J, Do HH, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Jackson JC, et al. Hepatitis B knowledge and practices among Cambodian Americans. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2011;12:957–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor VM, Burke NJ, Ko LK, Sos C, Liu Q, Do HH, et al. Understanding HPV vaccine update among Cambodian American girls. Journal of Community Health. 2014;39:857–62. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9844-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Combating the silent epidemic of viral hepatitis: action plan for the prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis. 2014 Retrieved from http://liver.stanford.edu/resources/HHSactionplanintro.pdf.

- 43.Wright WE. Khmer as a heritage language in the United States: historical sketch, current realities, and future prospects. Heritage Language Journal. 2010;7(1):117–47. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood LA, Kroger RO. Doing discourse analysis: methods for studying action in talk and text. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang JH, Lee H, Cho MO. The meaning of illness among Korean Americans with chronic hepatitis B. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2010;40:662–75. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2010.40.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yi JL, Anderson KO, Le EC, Escobar-Chaves SL, Reyes-Gibby CC. English proficiency, knowledge, and receipt of HPV vaccine in Vietnamese-American women. Journal of Community Health. 2013;38:805–11. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9680-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]