Abstract

Regeneration of skeletal muscles is required throughout life to ensure optimal performance. Therefore, a better understanding of the resident cells involved in muscle repair is essential. Muscle repair relies on satellite cells (SCs), the resident myogenic progenitors, but also involves the contribution of interstitial cells including fibro/adipocyte progenitors (FAPs). To elucidate the role of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling in these two cell populations, we previously analyzed freshly isolated cells for their FGF receptor (FGFR) signature. Transcript analysis of the four Fgfr genes revealed distinct expression profiles for SCs and FAPs, raising the possibility that these two cell types have different FGF-mediated processes. Here, we pursued this hypothesis exploring the role of the Klotho genes, known to function as FGFR co-receptors for the endocrine FGF subfamily. Isolated SC and FAP populations were analyzed in culture, exhibiting spontaneous myogenic or adipogenic differentiation, respectively. αKlotho transcript expression was not detected in either population. βKlotho transcript expression, while not detected in SCs, was strongly upregulated in FAPs entering adipogenic differentiation, coinciding with expression of a panel of adipogenic genes and preceding the appearance of intracellular lipid droplets. Overexpression of βKlotho in mouse cell line models enhanced adipogenesis in NIH3T3 fibroblasts but had no effect on C2C12 myogenic cells. Our study supports a pro-adipogenic role for βKlotho in skeletal muscle fibro/adipogenesis and calls for further research on involvement of the FGF-FGFR-βKlotho axis in the fibro/adipogenic infiltration associated with functional deterioration of skeletal muscle in aging and muscular dystrophy.

Keywords: Satellite cells, Fibro/adipocytes, FAPs, αKlotho, βKlotho, Fibroblast growth factor receptors, Adipogenic differentiation, Adipogenesis, Piggybac transposon, FGF21

Introduction

Skeletal muscle regeneration requires the participation of myogenic progenitors, termed satellite cells (SCs), that reside underneath the myofiber basal lamina and contribute progeny for myofiber repair [1, 2]. Effective muscle repair however, not only relies on SCs, but also involves the contribution of interstitial fibroblastic cells [3, 4]. A sub-set of these skeletal muscle interstitial cells, defined by the expression of the cell surface antigen Sca1, has been characterized as fibro/adipocyte progenitors (FAPs) based on a propensity to generate both fibroblasts and adipocytes [5–9]. These muscle-resident FAPs have been shown to be activated during muscle injury, normally acting in synergy with SCs to promote efficient muscle regeneration [5, 10]. Nevertheless, skeletal muscle regeneration is impaired with age and pathological conditions such as muscular dystrophy. In these situations, healthy contractile tissue was shown to be progressively infiltrated, or even replaced, by fibrotic and adipose tissue that contributes to deterioration of muscle function [11–14]. Although FAPs have been proposed to be the source of this intramuscular fibro/adipogenesis, the regulation of this pathogenic progression is just beginning to be unveiled [15, 16].

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, of which the first member was identified in 1974 as a promoter of fibroblast proliferation [17], comprises over 20 FGFs that are key players in the processes of proliferation and differentiation of a wide range of cells and tissues [18–20]. The FGFs are classified by their mechanism of action as paracrine (FGFs 1–10, 16–18, 20, 22), endocrine (FGFs 15/19, 21, 23) and intracrine (FGFs 11–14) [21, 22]. With the exception of intracrine FGFs that act as intracellular molecules, FGFs exert their effects through FGF tyrosine kinase receptors (FGFRs) that are coded by four different genes (Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Fgfr3, Fgfr4) [20, 23]. Most studies on the role of FGF signaling in skeletal muscle have focused on the prototypic (i.e. paracrine) FGF sub-family. Selective paracrine FGFs have been detected at the transcript and even the protein levels in adult skeletal muscle and have been known for a long time to act as mitogens of satellite cells (i.e. FGF1, FGF2, FGF4, FGF6) [24–29]. These paracrine FGFs require heparan sulfate as a co-factor for their stable interaction with FGFRs [20, 30, 31]. Differently, the endocrine FGFs have a low binding affinity for heparan sulfate and their interaction with FGFRs typically require the transmembrane FGFR co-receptors coded by the Klotho genes (αKlotho [AKA Klotho] and βKlotho) [23, 32, 33]. Our long-term interest in the role of the FGF family in adult myogenesis [25, 34–38] has prompted our recent study on the expression pattern of the FGF receptor (FGFR) genes (Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Fgfr3, Fgfr4) in SCs and in FAPs. Analyzing freshly isolated populations, we showed that while Fgfr1 was expressed at a relatively high level and Fgfr3 was detected at relatively low level by both SCs and FAPs, the expression of the other two Fgfr genes varied between the two cell types: Fgfr2 was below detection level in SCs, while some Fgfr2 expression was demonstrated by the FAPs, and Fgfr4 was expressed only by SCs [39]. The latter expression analysis of the four “traditional” Fgfr genes coding for the FGFRs is furthered in the current study that focuses on the expression profile and overexpression outcomes of the Klotho genes. The primary site of αKlotho expression is the kidney while βKlotho is primarily expressed in the liver and adipose tissue [40–43]. We and other laboratories have previously reported on the detection of low levels of αKlotho and βKlotho in skeletal muscle [40, 42–45]. We further observed a marked up-regulation in βKlotho gene expression in the diaphragm muscle of dystrophin-null (mdx4cv) mice, concomitant with the mdx muscle pathology of enhanced fibrosis and adipogenicity [43], raising the possibility that βKlotho is involved in muscle fibrosis.

In the current study we have analyzed the endogenous expression profile of the Klotho genes in FAP and SC cultures. αKlotho was not detected in either population. βKlotho was strongly upregulated in FAPs concomitant with adipogenic differentiation, while SC cultures never expressed βKlotho, nor underwent adipogenesis, even when cultured in adipogenic inducing medium. Forced expression of βKlotho in mouse cell line models enhanced adipogenesis in NIH3T3 fibroblasts but had no effect on C2C12 myogenic cells. These results provide novel insight into the potential role of βKlotho as a pro-adipogenic factor in skeletal muscle fibro/adipogenesis.

Results

βKlotho expression is associated with fibro/adipogenesis while myogenic cells neither enter adipogenesis nor express βKlotho

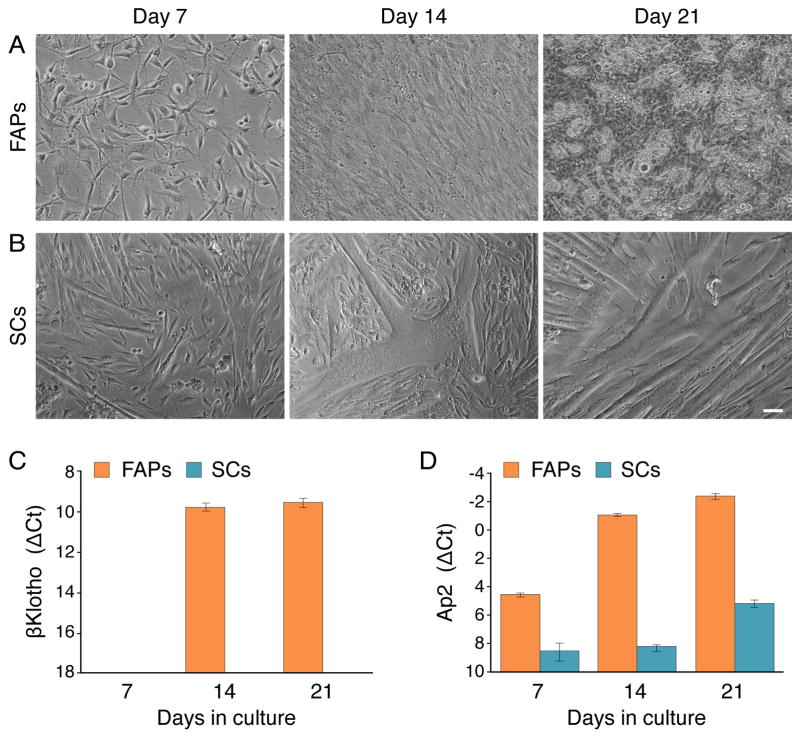

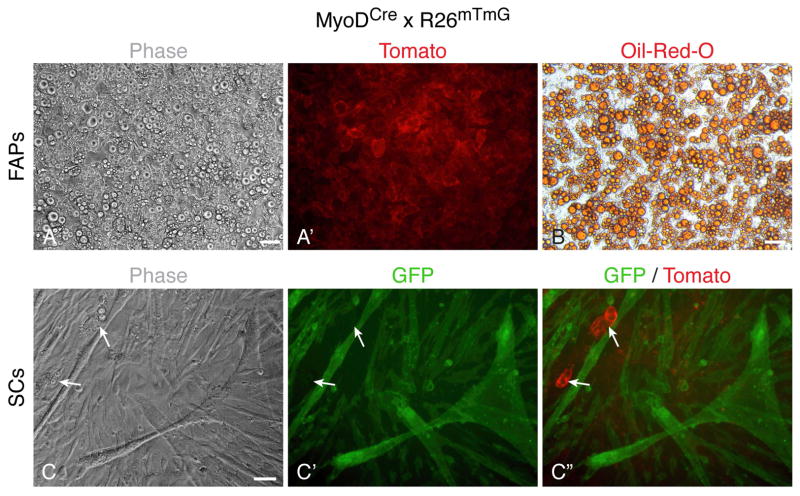

Expression of the Klotho genes was surveyed in cultures derived from satellite cells (SCs) and fibro/adipogenic progenitors (FAPs) freshly isolated from hindlimb skeletal muscle. SCs and FAPs were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) based on their respective antigen signatures of CD31−/CD45−/CD34+/Sca1− and CD31−/CD45−/CD34+/Sca1+, respectively, and cultured in our standard primary culture, mitogen-rich medium that contains 20% fetal calf serum (FBS), 10% horse serum (HS), and 1% chicken embryo extract. This growth medium that has been widely used by us to promote the proliferation and spontaneous myogenic differentiation of SC cultures, also supports the proliferation and spontaneous adipogenic differentiation of FAP cultures [7, 46] (Fig. 1). The plated cells were followed morphologically and processed for RT-PCR analyses at several time points (Fig. 1). The FAPs gave rise to fibroblastic cells that underwent spontaneous adipogenic differentiation in culture, as detected by the emergence of cells containing multivacuolar lipid droplets (Fig. 1A) associated with adipocyte maturation [47–50]. As anticipated, SCs gave rise to myogenic cultures that differentiated over time into multinucleated myotubes (Fig. 1B). Our initial RT-PCR studies showed that αKlotho was not expressed in any of the populations at any time point analyzed while βKlotho expression was observed only in the FAP cultures with expression rising at later time points. Quantitative RT-PCR analyses clearly demonstrated a robust rise of βKlotho expression in the FAP cultures by culture day 14 (Fig. 1C). This increase in βKlotho expression coincided with the upregulation of the adipogenic marker Ap2 (Fig. 1D) and preceded the morphological adipogenic differentiation as adipocytes were only seen at low frequency (~10%) in culture day 14, but were present at high frequency by culture day 21 (Fig. 1A). Differently, in the SC cultures, βKlotho expression was not detected (Fig. 1C) and Ap2 was only detected at a low basal level, at all time points analyzed (Fig. 1D). Typically, cultures of SCs isolated by FACS as described above are purely myogenic, but adipocyte-like cells have been sporadically detected in some of such preparations. Nevertheless, even when using adipogenic induction conditions, which promote robust adipogenic differentiation in FAP cultures (Figs. 2A–B), the occurrence of adipocytes remains extremely infrequent in the SC cultures (Figs. 2C–C″, arrows). Significantly, using a permanent reporter marking of the myogenic lineage (i.e. MyoD-Cre driven GFP expression, further details in Fig. 2 legend), we have clearly demonstrated that adipocytes developing in SC cultures are not progeny of SCs, but reflect rare non-myogenic cells co-isolated with the sorted SC population (Figs. 2C–C″). This conclusion is in agreement with an earlier report relying on isolated single myofibers [51].

Fig. 1.

Morphological (A, B) and quantitative RT-PCR (C, D) analyses of FAP and SC cultures harvested on days 7, 14, and 21 following initial plating. FAP and SC populations were isolated by FACS after obtaining single cell suspensions from hindlimb muscles of adult wildtype mice, and cultured in our standard (mitogen-rich) primary culture medium that promotes spontaneous adipogenesis and myogenesis of FAPs and SCs, respectively. The cultures were followed up morphologically (A, B), then harvested for quantitative RT-PCR analyses of βKlotho and the early adipogenic marker Ap2 (C, D). Notably, the presence of adipocytes containing multivacuolar lipid droplets seen in advanced FAP cultures (but not in SC cultures) has been also confirmed by Oil-Red-O staining as performed in Fig. 2. ΔCt values were normalized in reference to Eef2 gene expression. Results are noted as mean ± SD, n=3. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Fig. 2.

Lineage tracing analysis of FAP and SC cultures maintained under adipogenic induction conditions. FAPs and SCs were isolated from hindlimb muscles of adult MyoDCre x R26mTmG mice by FACS and cultured in our standard (mitogen-rich) primary culture medium until reaching near confluence, then switched to adipogenic induction conditions for up to 2 weeks. The R26mTmG reporter operates on a membrane-localized dual fluorescent system where all cells express Tomato until Cre-mediated excision of the Tomato gene allows for GFP expression in the targeted cell lineage [72]. Consequently, due to ancestral MyoD expression in the myogenic lineage [71], in the MyoDCre x R26mTmG cross, all skeletal muscles and their resident SCs are GFP+ while all other cells are Tomato+, as described in our previous studies [7, 39, 73]. (A, A′) Upon adipogenic induction, FAP cultures underwent robust adipogenesis with nearly all cells developing into adipocytes as illustrated by the presence of large intracellular lipid droplets (A′) stained with Oil-Red-O staining (B). Notably, images in (A, A′) and (B) were taken from two different replicative wells as the Oil-Red-O staining causes a general red autofluorescence, which preclude any reliable co-analysis of Tomato+ fluorescence. (C–C″) Differently, SC cultures, even when switched to adipogenic induction conditions, maintained a myogenic fate with only very rare adipocytes detected, which were Tomato+ indicating their non-myogenic source. Scale bars, 50 μm.

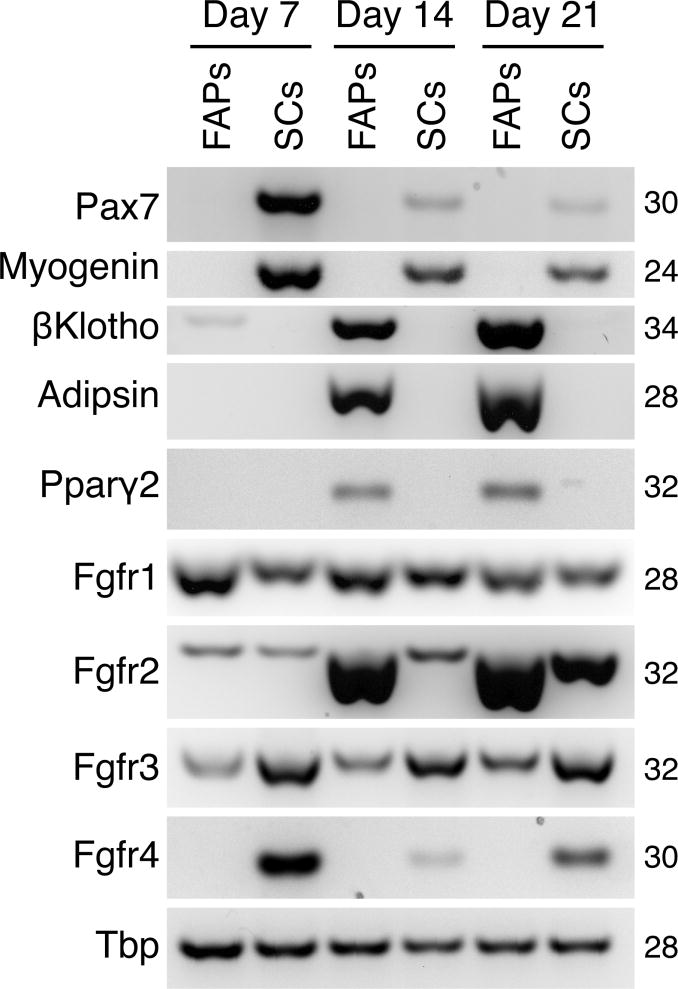

SC and FAP cultures were further characterized by semi-quantitative RT-PCR for the expression of a number of characteristic myogenic markers (Pax7, myogenin) and adipogenic markers (adipsin, Pparγ2) (Fig. 3). In view of βKlotho involvement in FGFR signaling (detailed in the Introduction), we additionally evaluated expression of the four Fgfr genes to establish if there are changes in Fgfr expression associated with βKlotho upregulation during fibro/adipogenesis. In a previous study, we only analyzed Fgfr expression in day 7 cultures of such FACS-sorted populations [39], a time point preceding βKlotho upregulation and the emergence of adipocytes in FAP cultures (as shown in Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 3, Fgfr1 and Fgfr3 were expressed in both cell types at a relatively higher and lower level, respectively, and their levels did not change appreciably across the three time points per each cell population. Differently, Fgfr4 expression was specific to the myogenic cells, in agreement with our previous studies [25, 39]. Strikingly, Fgfr2 was strongly upregulated in the FAP cultures by day 14, paralleling the strong upregulation in βKlotho and the adipogenic genes adipsin and Pparγ2 by day 14. SC cultures only showed relatively minimal Fgfr2 expression (with some increase by culture day 21) and no expression of βKlotho, Adipsin and Pparγ2 at any time point (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses of FAP and SC cultures harvested on days 7, 14, and 21 following initial plating. FAP and SC populations were isolated by flow cytometry from hindlimb muscles of adult wildtype mice and cultured in our standard (mitogen-rich) primary culture medium (as in Fig. 1). Pax7, Myogenin, βKlotho, Adipsin, Pparγ2, Ffgr1, Fgfr2, Fgfr3, and Fgfr4 transcript levels were determined and the expression level of Tbp was used as a reference gene.

Establishing βKlotho overexpressing C2C12 myoblasts and NIH3T3 fibroblasts

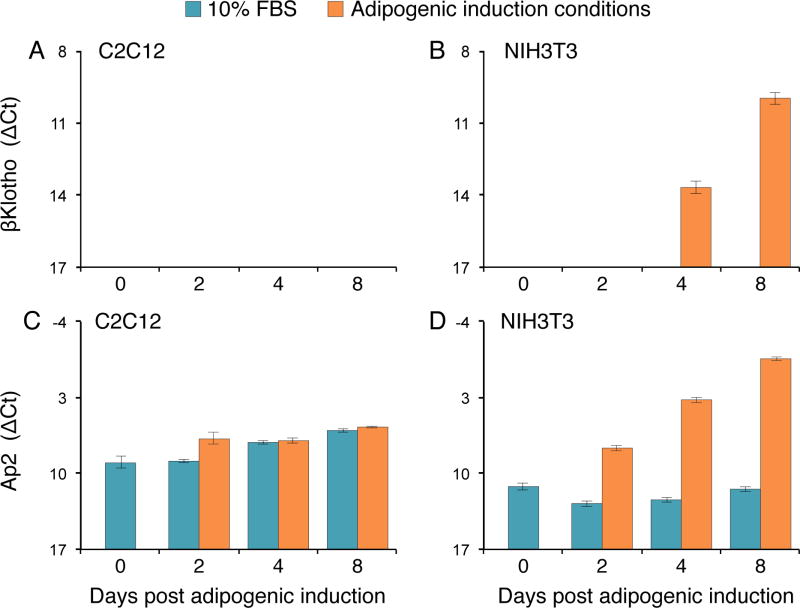

Next, we were interested in determining whether forced expression of βKlotho could induce adipogenic differentiation in myogenic cells or accelerate adipogenesis in fibroblastic cells. To facilitate overexpression experiments we switched to the well-characterized myogenic C2C12 and fibroblastic NIH3T3 mouse cell line models. These cell lines were maintained either in standard 10% FBS growth medium or switched to adipogenic induction conditions. Based on our initial morphological observations, while C2C12 retained a strict myogenic fate in both media, NIH3T3 underwent some adipogenic differentiation only when switched to adipogenic induction conditions. Before embarking into overexpression experiments, we determined baseline endogenous expression levels for αKlotho, βKlotho and Ap2 genes in these C2C12 and NIH3T3 cell lines maintained either in standard 10% FBS growth medium or switched to the adipogenic induction conditions (Fig. 4). In agreement with the aforementioned primary culture studies, αKlotho was not detected in either the myogenic or fibroblastic cell lines, and C2C12 cells did not exhibit βKlotho expression or up-regulation of Ap2 expression regardless of the culture medium (Figs. 4A, C). NIH3T3 fibroblasts demonstrated no βKlotho expression in the standard 10% FBS medium but robustly upregulated βKlotho expression when cultured under adipogenic conditions (Figs. 4B, D). The adipogenic marker Ap2, expressed at a low basal level in NIH3T3 cells cultured in 10% FBS medium, was also markedly up-regulated after cells were switched to adipogenic induction conditions, just preceding βKlotho upregulation (Fig. 4B, D) as observed for FAP cultures (Fig. 1). We also have been interested in the status of Fgfr gene expression in these two cell lines. We previously published the Fgfr expression profile for the C2C12 cells [37], demonstrating that levels of Fgfr1 and Fgfr3 did not change appreciably throughout the days in culture, Fgfr2 was barely detectable, while peak Fgfr4 expression coincided with the onset of myogenic differentiation. Here, we have analyzed Fgfr expression profile in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 5). Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 were relatively strongly expressed with a slight increase in their levels after adipogenic induction (Fig. 5A), while Fgfr3 and Fgfr4 were expressed at lower levels (Fig. 5B). Overall, the gene expression results obtained with the “wildtype” NIH3T3 fibroblasts and the C2C12 myogenic cell line corroborate our observations made with the FAPs and SCs primary cultures, suggesting a role for βKlotho during adipogenic differentiation in fibroblasts while the myogenic cells neither enter differentiation nor upregulate βKlotho.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of βKlotho and the early adipogenic gene Ap2 in (A, C) C2C12 and (B, D) NIH3T3 cultures maintained throughout the experiment in our standard 10% FBS cell line growth medium or switched to the adipogenic induction conditions. Day 0 refers to cultures just prior to the switch and subsequent days 2, 4, 6, 8 reflect time following the switch to the adipogenic induction conditions. ΔCt values were normalized in reference to Eef2 gene expression. Results are noted as mean ± SD, n=6.

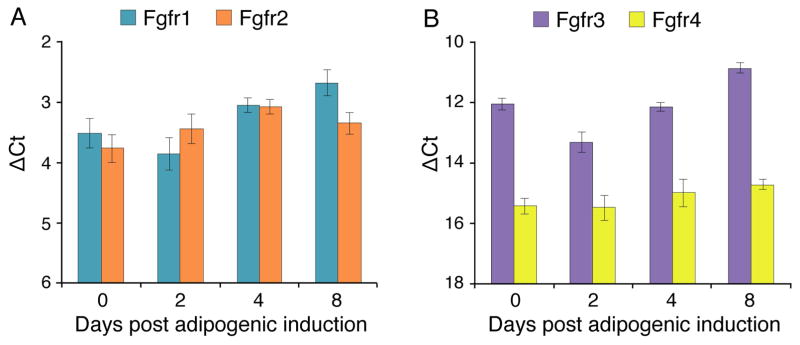

Fig. 5.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression levels of (A) Fgfr1/Fgfr2, and (B) Fgfr3/Fgfr4 genes in NIH3T3 cultures switched to the adipogenic induction conditions. Day 0 refers to cultures just prior to the switch and subsequent days 2, 4, 8 reflect time following the switch to the adipogenic induction conditions. ΔCt values were normalized in reference to Eef2 gene expression. Results are noted as mean ± SD, n=3.

C2C12 and NIH3T3 stable cell lines overexpressing βKlotho were developed using the Piggybac transposon vector system as described in Materials and methods. In order to monitor βKlotho-expressing cells, we opted to overexpress a βKlotho-GFP fusion construct that also allows insights into βKlotho localization in live cells. To ensure that the fusion of βKlotho with GFP does not alter the effect of overexpressed βKlotho, we also overexpressed a control βKlotho-IRES-GFP bicistronic construct, which enables independent expression of the βKlotho and GFP proteins. As additional controls for the specificity of the effect of overexpressed βKlotho, we generated αKlotho-IRES-GFP and GFP expressing cell lines. Representative GFP fluorescent images (live cultures) of all C2C12 and NIH3T3 cell lines developed are shown in Fig. 6A. Overexpression of GFP, alone, or when using α/βKlotho-IRES-GFP constructs, resulted in a typical ubiquitous GFP fluorescence pattern throughout the cell. Differently, C2C12 and NIH3T3 cells overexpresssing the βKlotho-GFP fusion construct demonstrated specifically localized GFP fluorescence in perinuclear and cell-cell contact regions as further depicted in higher magnification images in Fig. 7. Production of the βKlotho-GFP fusion protein was also verified by western blot using a GFP antibody (data not shown). βKlotho transcripts were measured for all developed cell lines maintained in standard 10% FBS growth medium, and as expected (see Fig. 4A, B, 10% FBS condition) were detected only in the βKlotho-GFP and βKlotho-IRES-GFP expressing cell lines (Figs. 6B, C). For both C2C12 and NIH3T3 cells, the level of overexpressed βKlotho was over 2000 fold higher when compared to the highest level of endogenous βKlotho expressed in wildtype NIH3T3 cells exposed to adipogenic conditions (i.e. compare Figs. 6B, C and Fig. 4B).

Fig. 6.

Morphological and quantitative RT-PCR characterization of all C2C12 and NIH3T3 stable cell lines developed in the current study. Cell lines that have integrated the βKlotho-GFP fusion construct were compared to wildtype and cell lines that have integrated a control GFP construct; additional NIH3T3 stable cell lines that have integrated a βKlotho-IRES-GFP or a αKlotho-IRES-GFP construct were also analyzed as controls. (A) Representative phase and GFP fluorescent images (live cultures). Cell lines overexpressing a GFP, αKlotho-IRES-GFP, or βKlotho-IRES-GFP construct show a typical ubiquitous GFP fluorescence pattern with the latter two lines depicting lower level of GFP, likely due to GFP gene being downstream of IRES sequence. C2C12 and NIH3T3 cells overexpresssing the βKlotho-GFP fusion construct demonstrate specifically localized GFP fluorescence in perinuclear and cell-cell contact regions as further depicted in higher magnification images in Fig. 7. C2C12 cultures shown were switched to 2% HS medium to promote synchronized myogenic differentiation, and both myoblasts and myotubes exhibit similar ubiquitous (GFP construct) or localized (βKlotho-GFP construct) GFP distribution pattern. (B, C) Overexpression of βKlotho was measured at the transcript level by quantitative RT-PCR in (B) C2C12 and (C) NIH3T3 cell lines. ΔCt values were normalized in reference to Eef2 gene expression. Results are noted as mean ± SD, n=3.

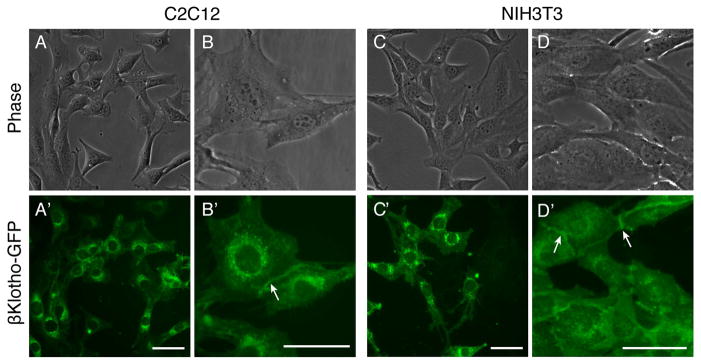

Fig. 7.

Localization of overexpressed βKlotho-GFP fusion protein in C2C12 myoblasts and NIH3T3 fibroblasts cultured in standard 10% growth medium. In both cell lines, βKlotho-GFP detected by direct GFP localization in live cells is localized to (A–D′) perinuclear regions and occasionally (B–B′, D–D′) areas of cell-cell contact (arrows). Scale bars, 5 μm.

As mentioned earlier, the use of the βKlotho-GFP fusion construct has permitted insight into βKlotho localization in live cells. In both C2C12 and NIH3T3 cells, βKlotho-GFP was detected in discrete perinuclear regions (Fig. 7A–D′), presumably within the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi network [52], while also occasionally observed at cell-cell contacts (Figs. 7B–B′ and D–D′, arrowheads). This pattern of βKlotho distribution determined by direct GFP localization is in accordance with a previous cytological study that has detected βKlotho predominantly in the endoplasmic reticulum with only a small portion of the protein found in the plasma membrane [53]. The latter study has further shown that βKlotho harbors an endoplasmic reticulum retrieval signal, and was hypothesized to play a role in regulating FGFR glycosylation within the endoplasmic reticulum [53].

Overexpression of βKlotho does not influence C2C12 myoblasts but enhances adipogenic differentiation in NIH3T3 fibroblasts

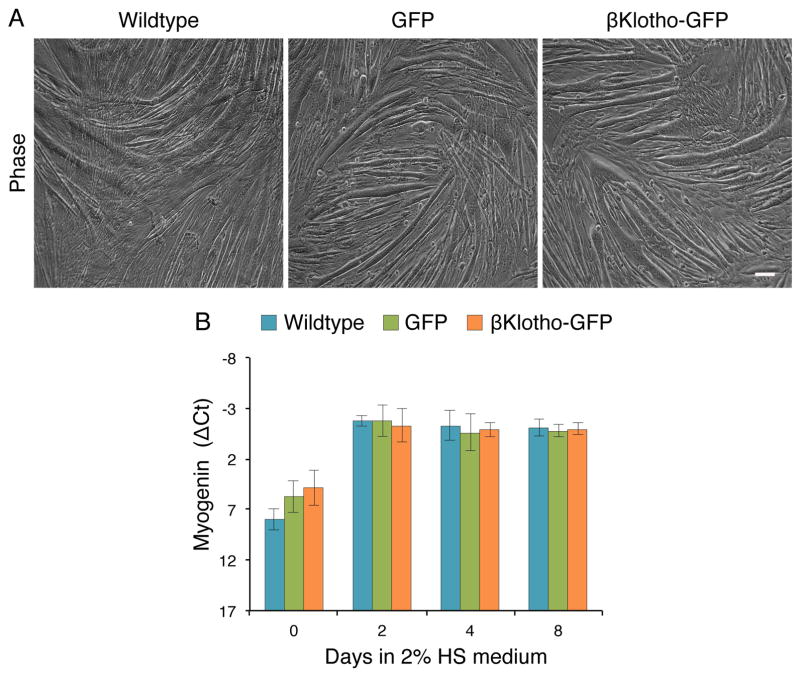

C2C12 cells overexpressing βKlotho-GFP retained myogenicity and clearly did not enter adipogenic differentiation regardless of medium conditions. Whether maintained in standard 10% FBS medium or switched to adipogenic inducing conditions, the three C2C12 cell lines (wildtype, GFP and βKlotho-GFP) demonstrated extensive proliferation with some myotube formation, without appearance of any morphological evidence for adipocyte development (data not shown). Furthermore, when cells were switched to the differentiation synchronizing 2% HS medium, overexpression of βKlotho-GFP in C2C12 cells did not influence myogenic differentiation at the morphological level (i.e. myotube development, Figs. 6A and 8A) or according to the expression level of the myogenic-specific transcription factor myogenin (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

βKlotho overexpressing C2C12 cells retain their myogenic fate as determined by morphological and transcript expression analyses. Wildtype C2C12 cells and C2C12 cells overexpressing GFP or βKlotho-GFP were cultured in standard 10% FBS growth medium and when near confluence, switched (day 0) into a DMEM-based medium containing 2% HS in order to promote a synchronized myogenic differentiation. (A) Representative phase images of day 5 cultures demonstrating a typical morphology of differentiated myogenic cultures for all three stable cell lines analyzed. (B) Myogenin gene expression profile as determined by quantitative RT-PCR. ΔCt values were normalized in reference to Eef2 gene expression. Results are noted as mean ± SD, n=6. Scale bars, 100 μm.

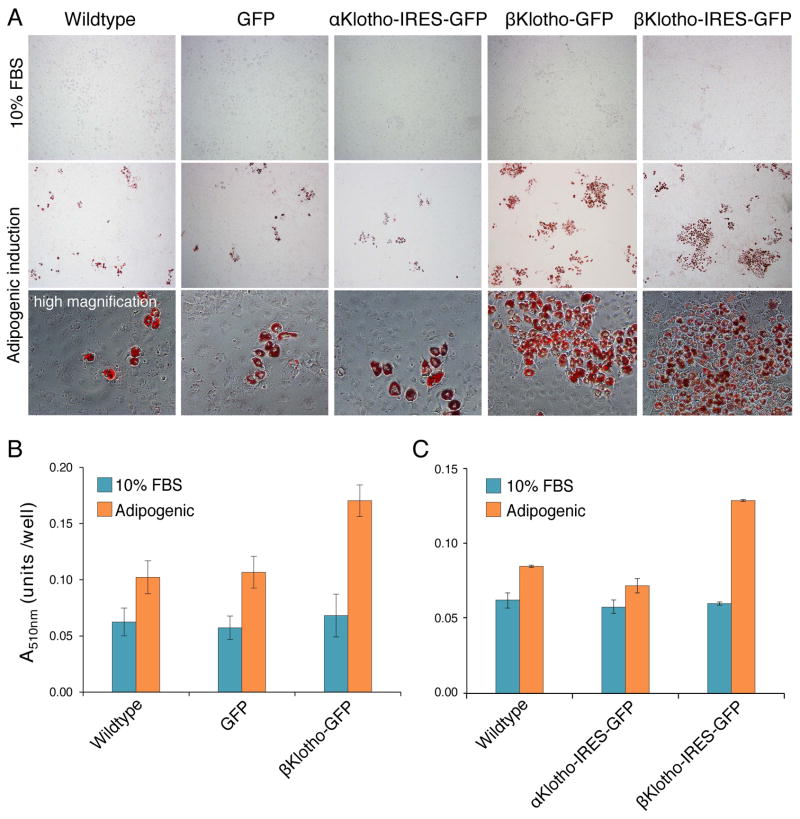

Different from C2C12 myoblasts, NIH3T3 fibroblasts do undergo some adipogenic differentiation but only when switched from 10% FBS medium to adipogenic inducing conditions (Fig. 9A). Overexpression of βKlotho did not induce adipogenic differentiation when NIH3T3 cells were maintained in standard 10% FBS medium, but resulted in increased adipogenic differentiation for NIH3T3 cells switched to adipogenic inducing conditions. As readily apparent in images of Oil-Red-O staining and further demonstrated in subsequent quantification (Fig. 9), overexpression of βKlotho (βKlotho-GFP or βKlotho-IRES-GFP constructs) resulted in 52–79% increase in lipid levels compared to control NIH3T3 cell lines (wildtype, and overexpressing GFP or αKlotho-IRES-GFP) (p<0.001, Figs. 9B and C).

Fig. 9.

βKlotho overexpressing NIH3T3 cells demonstrate enhanced adipogenic differentiation compared to control cells as determined by Oil-Red-O staining. Wildtype NIH3T3 cells and NIH3T3 cells overexpressing GFP, αKlotho-IRES-GFP, βKlotho-GFP or βKlotho-IRES-GFP, were either maintained in standard 10% FBS growth medium or switched to adipogenic induction conditions for 14 days. (A) Representative phase images of Oil-Red-O stained cultures. For all cell lines, adipogenic differentiation occurs only when cells are switched to adipogenic induction conditions and is clearly enhanced upon βKlotho overexpression. Additional high magnification images clearly demonstrate the development of mature adipocytes as detected by the presence of cells containing large multivacuolar lipid droplets stained with Oil-red-O. (B, C) Quantification of Oil-Red-O staining level after extraction of the Oil-Red-O dye within each cell culture and measure of its specific absorbance (at 510 nm wavelengths) by spectrophotometry. When maintained in 10% FBS growth medium, no significant differences in the amount of Oil-Red-O staining were detected between all the different NIH3T3 cell lines tested (p=0.34). When switched to adipogenic induction conditions, βKlotho-GFP overexpressing cells demonstrated a significant increase in lipid levels compared to wildtype (67% higher, p<0.001) and GFP overexpressing (59% higher, p=0.001) controls. Similarly, in another complementary study, NIH3T3 cells overexpressing βKlotho-IRES-GFP exhibited a significant increase in the level of Oil-Red-O staining compared to wildtype (52% higher, p<0.0001) and αKlotho-IRES-GFP overexpressing cells (79% higher, p<0.0001). Data shown in (B) and (C) are from two independent studies. Results are noted as mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test, n=14 and n=6 for data in (B) and (C), respectively.

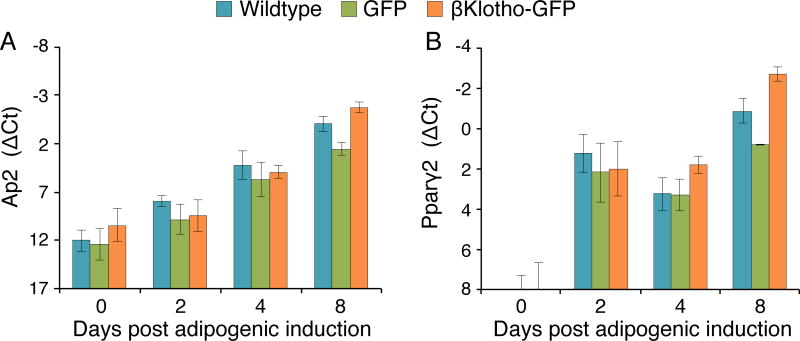

Following the above demonstration of a βKlotho effect on morphological adipogenic differentiation in NIH3T3 cells, we further explored the effect of βKlotho overexpression on transcript levels of the early adipogenic regulatory genes Ap2 and Pparγ2. These genes have been typically described as early adipogenic genes [54, 55] and as shown above for FAPs cultures, their expression precedes the accumulation of lipid droplets during adipogenic differentiation (Figs. 1 and 3). Here, the βKlotho-GFP NIH3T3 cells were compared with the wildtype and GFP control lines for Ap2 and Pparγ2 transcript levels (Fig. 10). Cells were first cultured in standard 10% FBS medium and then switched to adipogenic induction conditions; day 0 in Fig. 8 refers to cultures just prior to the switch and subsequent days 2, 4, 8 reflect time following the switch to the adipogenic conditions. Both Ap2 and Pparγ2 were upregulated in all the three NIH3T3 cell lines over the time spent in the adipogenic induction conditions, but for each gene there was no apparent difference in expression profile between the three cell lines analyzed (Fig. 10). Notably, similar to the lag in the onset Pparγ2 expression compared to Ap2 expression observed with FAP cultures undergoing spontaneous adipogenic differentiation (Figs. 1 and 3), in the NIH3T3 lines, Ap2 was already present at day 0, while Pparγ2 was first detected only after adipogenic induction (Fig. 10). βKlotho overexpression also had no apparent effect on transcript levels of the four Fgfr genes (data not shown) with their expression profiles during the course of adipogenic differentiation resembling the pattern shown in Fig. 5 for wildtype NIH3T3.

Fig. 10.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression levels of early adipogenic genes in NIH3T3 βKlotho overexpressing cells versus control lines. Wildtype NIH3T3 cells and NIH3T3 cells overexpressing GFP or βKlotho-GFP were cultured in standard 10% FBS growth medium or switched to the adipogenic induction conditions. Day 0 refers to cultures just prior to the switch and subsequent days 2, 4, 8 reflect time following the switch to the adipogenic induction conditions. (A) Ap2 and (B) Pparγ2 transcript levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR at different time points in culture. There was no apparent difference in the level of expression between cell types. ΔCt values were normalized in reference to Eef2 gene expression. Results are noted as mean ± SD, n=6.

Discussion

This study of βKlotho expression profiling and overexpression outcome introduces βKlotho as a novel player in skeletal muscle fibro/adipogenesis, while myogenic cells neither express βKlotho nor affected by βKlotho overexpression. First, our results reveal that βKlotho expression is specifically upregulated in the FAP cultures derived from skeletal muscle, concomitant with the upregulation of the adipogenic markers Ap2, Pparγ2 and Adipsin, and preceding the phenotypic emergence of adipocytes. Second, our overexpression experiments have suggested that βKlotho is important during fibro/adipogenesis as βKlotho overexpressing NIH3T3 fibroblastic cells exhibited a marked increase in adipogenic differentiation when exposed to adipogenic conditions. Differently, myogenic cultures derived from SCs or from the C2C12 cells never entered adipogenesis (even when maintained in adipogenic induction conditions), nor expressed βKlotho, and overexpression of βKlotho in the C2C12 cell line clearly did not induce adipogenic differentiation. In the NIH3T3 cells overexpressing βKlotho, while an enhanced adipogenesis at the morphological level was observed, we found that βKlotho overexpression had no apparent impact at transcript levels of the early adipogenic regulatory genes Ap2 and Pparγ2. This observation, taken together with our finding that NIH3T3 cells overexpressing βKlotho (like control cells) did not enter adipogenesis unless switched from standard 10% FBS medium to adipogenic inducing conditions, may indicate that βKlotho promotes later stages of adipogenic differentiation and that an intrinsic pro-adipogenic program needs to be activated before βKlotho can induce its effect. We further propose that such pro-adipogenic intrinsic program is not active in myogenic cells, as these do not enter adipogenesis even in adipogenic induction conditions regardless of βKlotho overexpression.

While the determination of which FGF and which FGFR are involved in the FGF-FGFR-βKlotho axis during skeletal muscle fibro/adipogenesis awaits future studies, it is attractive to propose FGFR2 for the receptor based on its strong upregulation observed concomitant with βKlotho upregulation in the cultured FAPs, and to suggest FGF21, a member of the endocrine FGF subfamily, as the candidate ligand, in view of its established presence in skeletal muscle and its role within adipose tissue. FGF21 is a key mediator of systemic glucose and lipid metabolism, playing a role in obesity and diabetes [44, 56–58]. While FGF21 was first identified as predominantly expressed in the liver [59], it has been later shown to be secreted by a number of tissues including skeletal muscle [60–62]. Particularly, a recent wave of studies has revealed FGF21 as a stress induced endocrine factor that targets adipose tissue through the FGFR-βKlotho complex [63–69] with βKlotho expression determining the tissue specificity of FGF21 action [70].

Collectively, future studies on the dynamics of skeletal muscle fibro/adipogenesis and the involvement of the FGF-FGFR-βKlotho axis are likely to provide important insight into the molecular and cellular changes in skeletal muscles associated not only with aging and muscular dystrophy where fibrosis and fat infiltration have been demonstrated, but also with diabetes and obesity where cellular modifications have not been fully characterized yet.

Materials and methods

Animals

Mice were from our colonies maintained under 12:12-h light/dark cycle and fed ad libitum Lab Diet 5053 (Purina Mills, St. Paul, MN, USA). Animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Washington. Experimental mice were typically 3–6 month old males. Mouse strains included wildtype C57BL/6 and double heterozygote MyoDCre x R26mTmG on an enriched C57BL/6 background. To obtain the latter reporter strain, knockin heterozygous males MyoDCre [MyoD1tm2.1(icre)Glh [71]] provided by David Goldhamer, backcrossed by us to C57BL/6, were bred with knockin reporter females R26mTmG [Gt(ROSA) 26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J [72]] to generate adult F1 MyoDCre/+ x R26mTmG/+ double heterozygous animals. The R26mTmG reporter operates on a membrane-localized dual fluorescent system where all cells express Tomato until Cre-mediated excision of the Tomato gene allows for GFP expression in the targeted cell lineage [72]. Consequently, due to ancestral MyoD expression in the myogenic lineage [71], in the MyoDCre x R26mTmG cross, all skeletal muscles and their resident SCs are GFP+ while all other cells are Tomato+, as described in our previous studies [7, 39, 73].

Isolation of satellite cells and fibro/adipogenic progenitors by fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Cells were isolated from pooled hindlimb muscles (tibialis anterior, gastrocnemius and extensor digitorum longus) of adult mice following our previously published procedure [7, 39, 73]. SC and FAP populations were then purified by FACS. All sorted cells were collected within the G0–G1 population depleted of CD31+ (endothelial) and CD45+ (hematopoietic) cells. When muscles were harvested from wildtype mice, SC and FAP populations were further isolated as CD34+/Sca1− and CD34+/Sca1+ cells, respectively. When muscles were harvested from MyoDCre x R26mTmG mice, SC and FAP populations were further isolated as GFP+/Sca1− and Tomato+/Sca1+ cells, respectively [7, 39, 73].

In brief, for both mouse strains, cell suspensions were released from harvested muscles by collagenase/dispase digestion and were first incubated with 10 μM Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min at 37°C to label cell nuclei, followed by incubation with a combination of fluorescently conjugated monoclonal antibodies (all from eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) that included: Sca1-APC (clone D7), CD31-PECy7 (clone 390), CD45-PECy7 (clone 30-F11) and CD34-FITC (clone RAM34) with the latter being used only when sorting cells from wildtype but not from MyoDCre x R26mTmG mice. Antibodies were diluted at a ratio of 300 ng of antibody per 106 cells for Sca1-APC, 1μg of antibody per 106 cells for CD34-FITC, and 600 ng of antibody per 106 cells for CD31-PECy7 and CD45-PECy7. Cell sorting was performed using an Influx Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with 350, 488, and 638 nm lasers. Gates were determined by comparing fluorophore signal intensities between the unstained control and each single antibody/fluorophore control, and sorted cells were collected in our mitogen-rich growth medium and then cultured for morphological follow-up and RNA isolation as described below.

Satellite cell and fibro/adipogenic progenitor cultures

The basal solution for all culture medium preparations used in this study consisted of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, high glucose, with L-glutamine, 110 mg/l sodium pyruvate, and pyridoxine hydrochloride, Hyclone GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, Utah, USA) supplemented with antibiotics (50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). SC and FAP populations were cultured in 12-well culture plates pre-coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, diluted to a final concentration 1 mg/ml, [46]). Cultures were initiated at a density of 3–4 × 104 cells per well and incubated at 37°C/5% CO2, using our standard DMEM-based mitogen-rich growth medium containing 20% fetal calf serum (FBS) and 10% horse serum (HS) (both from Gibco), and 1% chicken embryo extract [46]. After the initial plating, growth medium was replaced every 3 days. When indicated cultures were switched to adipogenic inducing conditions as described in the next section.

Cultures of C2C12 and NIH3T3 cell lines, and adipogenic induction conditions

Murine C2C12 myoblasts [74, 75] and NIH3T3 fibroblasts [76] were cultured in 24-well plates at a cell density of 12,000 and 30,000 cells per well, respectively. Both cell lines were incubated at 37°C/5% CO2, using a DMEM-based growth medium containing 10% FBS.

When indicated, cells were switched to adipogenic induction conditions (adapted from [77]). Briefly, near-confluent cultures were switched into DMEM-based medium containing 10% FBS, 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 1 μg/ml dexamethasone, and 5 μg/ml insulin (Sigma-Aldrich)] for two days followed by a switch to a high-insulin medium consisting of DMEM with 10% FBS and 5 μg/ml insulin for the remainder of the culture time. The high insulin medium was typically changed every other day or daily when reaching high density. For control cultures, a medium change to fresh standard growth medium was applied at the time the parallel cultures were switched to adipogenic induction conditions and at any subsequent medium change.

Oil-Red-O staining and quantification

Oil-Red-O staining of triglycerides and lipids was performed on cultured cells as previously described [50]. For each condition, a minimum of 9 wells from 3 independent experiments were quantified. Briefly, cultures fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde were incubated with Oil-Red-O working solution for 30 min, and then washed with Tris buffered saline. Oil-Red-O staining level was quantified by extracting the dye in each well using 100 μl of 100% isopropanol for 1 min (protocol adapted from [78]). The absorbance of Oil-Red-O dye in each well was then quantified on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) at 510 nm wavelengths.

Gene expression analyses

To isolate total RNA, cultured cells were rinsed twice with DMEM before adding the lysis buffer from the RNeasy Plus Micro kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and processed according to the manufacturer instructions. The RNA was then quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer or a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and reverse transcribed (at 0.4 ng/μl and 20 ng/μl for quantitative and semi-quantitative gene expression analysis, respectively) into cDNA using the iScript reverse transcriptase (Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) as previously described [79].

Quantitative RT-PCR analyses were performed as previously described [45]. Gene expression was determined by SYBR Green-based quantitative PCR using 1 μl cDNA per reaction (20 μl final volume) on an ABI 7300 Real Time PCR machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The qPCR forward and reverse primer sequences used were: αKlotho (Kl, 398bp), CGACTACCCAGAGAGTATGAAG/TATGCCACTCGAAACCGTCCATGA; βKlotho (Klb; 326bp) ACCAGGTTCTTCAAGCAATAAAAT/CAGTGACATTCCACACATACAG; Ap2 (Fabp4, 344bp) TCACCTGGAAGACAGCTCCT/TCGACTTTCCATCCCACTTC; Pparγ2 (103bp, PrimerBank ID: 6755138a1) TCGCTGATGCACTGCCTATG/GAGAGGTCCACAGAGCTGATT; myogenin (Myog, 106bp, PrimerBank ID: 13654247a1) GAGACATCCCCCTATTTCTACCA/GCTCAGTCCGCTCATAGCC; Fgfr1, GCCCTGGAAGAGAGACCAGC/GAACCCCAGAGTTCATGGATGC (244bp, [37]); Fgfr2, GCCTCTCGAACAGTATTCTCCT/ACAGGGTTCATAAGGCATGGG (103bp, PrimerBank ID 2769639a1, [80]); Fgfr3, GGCTCCTTATTGGACTCGC/TCGGAGGGTACCACACTTTC (219bp, [81]); Fgfr4, TTGGCCCTGTTGAGCATCTTT/GCCCTCTTTGTACCAGTGACG (189bp, PrimerBank ID 6679789a1); Eef2 (123bp, PrimerBank ID: 33859482a1), TGTCAGTCATCGCCCATGTG/CATCCTTGCGAGTGTCAGTGA. The final concentration of all primers was 500 nM except for the βKlotho reverse primer, which was used at 300 nM final concentration. Raw qPCR cycle threshold values for each individual sample were normalized to Eef2 (eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2) reference gene expression [39, 45]. Notably, Eef2 expression level showed little variation between primary culture treatment groups (average Ct 14.88±0.13) or cell lines treatment groups (average Ct 16.30±0.04). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Genes were considered expressed if cycle threshold values (raw Ct) of less than 33 cycles were detected.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses were performed following our previously published protocol [79]. Briefly, for all PCR reactions, we used 5 μl of cDNA per PCR reaction (25 μl final volume) and the following cycling parameters: 95°C for 15 min, 24–34 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 60°C for 50 s, 72° for 1 min, with a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min. The PCR forward and reverse primer sequences for Pax7, myogenin, βKlotho, adipsin, Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Fgfr3, Fgfr4 and Tbp were as in our previous publications [37, 43, 79]). The PCR forward and reverse primer sequences for Pparγ2 were GCTGTTATGGGTGAAACTCTG/ATAAGGTGGAGATGCAGGTTC (351bp). All primers were used at a final concentration of 400 nM. Expression of Tbp (TATA box binding protein) housekeeping control gene served as quality and loading control as in [43]). PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gels containing 1:10,000 dilution of SYBR Green I (Molecular Probes, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gels were imaged using Gel Logic 212 Pro (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA).

Statistics

Data were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA. When ANOVA revealed significant differences between groups, post hoc t-tests were performed with a Bonferroni correction to the level of significance. Data are presented as mean ± SD or mean ± SEM as indicated in figure legends, where n is the number of experimental replicates; P values <0.01 were considered significant.

Generation of overexpressing stable cell lines

Mammalian expression constructs employing the piggybac transposon system were used to produce NIH3T3 and C2C12 transgenic stable cell lines for experimentation. Such stable overexpressing cell lines were created after initial attempts to transiently overexpress αKlotho-EGFP or βKlotho-EGFP fusion constructs (driven by the CMV or EF1α promoter, using the pCR3.1 expression vector) resulted in high levels of cell death. Transiently transfected cells exhibited strong endoplasmic reticulum localized GFP expression and died 2–3 days after transfection potentially due to the endoplasmic reticulum overload response [82]. The latter plasmids (deposited as pCMV-Kl-EGFP and pCMV-Klb-EGFP at Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA, plasmids #45532 and #45531, respectively) were further used as subcloning constructs to develop the Piggybac expression constructs as described below.

Full-length coding sequences (CDS) for αKlotho and βKlotho were cloned from murine kidney or adipose tissue cDNA, respectively; these tissues show high expression of each of the respective Klotho gene [40, 42]; supplemental material in [43]. Both genes were PCR amplified using pfu ultraII HotStart fusion polymerase (Agilent) under the following conditions: 95°C 1min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 20sec, 61°C for 20sec, and 72°C for 1min, 45sec, with a final extension at 72°C for 3min. The following primer sets were used for gene amplification (fwd/rev): αKlotho, GCATGCTAGCCCGCGC/CGTTCACATTACTTATAACTTCTCTGGC; and αKlotho, GATCCAGGCTAATCATTGACAGGG/GTAAGTTACCAGTACATGGAGCCG.

βKlotho-GFP fusion construct was created by cloning the βKlotho CDS (lacking a stop codon and with PCR added ′ HindIII and 3′ SpeI restriction sites) into a modified pCR3.1 vector driving emerald GFP (emGFP, termed GFP throughout the manuscript) expression. The βKlotho-GFP sequence was then subcloned into a modified piggybac transposon vector (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA) containing the human eukaryotic elongation factor-1α (hEEF1A) promoter, a T2A self-cleaving peptide sequence and the puromycin resistance gene (at 5′ HindIII and 3′ MluI restriction sites between the hEEF1A promoter and the T2A sequence; pPB-hEEF1A-Klb-GFP-T2A-PuroR). To enable T2A and puromycin translation, the βKlotho-GFP sequence was modified to remove the GFP stop codon (by PCR) prior to cloning. A GFP control vector was also created by amplifying the GFP CDS (with 5′ HindIII and 3′ MluI restriction sites) and cloning into the piggybac backbone vector (pPB-hEEF1A-GFP-T2A-PuroR). To independently express βKlotho and GFP, a bicistronic βKlotho-IRES-GFP vector was also created. This was achieved by PCR amplifying the βKlotho CDS (with stop codon) from pCMV-KLb-EGFP with added 5′ NheI and 3′ NotI restriction sites into a vector containing an IRES-GFP sequence (GFP lacking stop codon). The entire βKlotho-IRES-GFP fragment was then subcloned into the piggybac vector backbone (using NheI and MluI restriction sites present between the hEEF1A promoter and the T2A sequence; pPB-hEEF1A-Klb-IRES-GFP-T2A-PuroR). A similar αKlotho-IRES-GFP bicistronic construct was also produced by cloning the αKlotho CDS (derived from pCMV-Kl-EGFP) into the pPB-hEEF1A-Klb-IRES-GFP-T2A-PuroR vector in place of the βKlotho transgene (pPB-hEEF1A-Kl-IRES-GFP-T2A-PuroR). All constructs were thoroughly sequenced for accuracy prior to experimentation (Genewiz, Seattle, WA, USA).

Stable βKlotho-GFP and GFP expressing cells were created for both NIH3T3 and C2C12 cells whereas only NIH3T3 cells were used to produce stable βKlotho-IRES-GFP and αKlotho-IRES-GFP overexpressing cell lines. One hundred thousand cells per transfection were electroporated using the Neon electroporation system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to manufactures protocols (C2C12; 1 pulse at 1400V for 30ms, NIH3T3; 2 pulses at 1400V for 20 ms). A total of 700 ng of total plasmid DNA was added for each transfection at a 2.5:1 ratio of transposon to transposase (System Biosciences). Transfected cells were plated into two separate 10 cm plates and cultured for 3 days prior to the addition of puromycin for selection (3 μg/ml). Once stable cell lines were established frozen stocks were created and working cultures were grown in the absence of puromycin to match wildtype cell culture conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lindsey Muir for her valuable comments on the manuscript and our former team members, Maria Elena Danoviz and Andrew Shearer for their involvement during the early SC/FAP studies, and Rachel Gillespie for participating in the αKlotho-IRES-GFP cell line development. We are also grateful to Donna Prunkard and Peter Rabinovitch for providing cell sorting support (performed at the core facility of the University of Washington Nathan Shock Center of Excellence). This work was funded by grants to Z.Y.R. from the National Institutes of Health (AG021566 and NS090051). Z.Y.R. acknowledges additional support during the course of this study from the National Institutes of Health (AG035377 and NS088804). M.P. was supported by the Genetic Approaches to Aging Training Program (T32 AG000057). P.S. was supported by an AFM-telethon fellowship (#18574).

Abbreviations

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- SCs

satellite cells

- FAPs

fibro/adipocyte progenitors

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HS

horse serum

- CDS

coding sequence

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

Footnotes

Author Contributions

M.P. planned experiments; performed experiments; analysed data; wrote the paper. P.S. planned experiments; performed experiments; analysed data; wrote the paper. Z.Y.R. conceived and led the project; planned experiments; performed experiments; analysed data; wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Montarras D, L’Honoré A, Buckingham M. Lying low but ready for action: the quiescent muscle satellite cell. FEBS J. 2013;280:4036–4050. doi: 10.1111/febs.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yablonka-Reuveni Z. The Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cell Still Young and Fascinating at 50. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:1041–1059. doi: 10.1369/0022155411426780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew SJ, Hansen JM, Merrell AJ, Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Hutcheson DA, Hansen MS, Angus-Hill M, Kardon G. Connective tissue fibroblasts and Tcf4 regulate myogenesis. Development. 2011;138:371–384. doi: 10.1242/dev.057463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Mathew SJ, Hutcheson DA, Kardon G. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3625–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joe AWB, Yi L, Natarajan A, Le Grand F, So L, Wang J, Rudnicki MA, Rossi FMV. Muscle injury activates resident fibro/adipogenic progenitors that facilitate myogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:153–163. doi: 10.1038/ncb2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemos DR, Paylor B, Chang C, Sampaio A, Underhill TM, Rossi FMV. Functionally Convergent White Adipogenic Progenitors of Different Lineages Participate in a Diffused System Supporting Tissue Regeneration. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1152–1162. doi: 10.1002/stem.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuelsatz P, Shearer A, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Ancestral Myf5 gene activity in periocular connective tissue identifies a subset of fibro/adipogenic progenitors but does not connote a myogenic origin. Dev Biol. 2014;385:366–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uezumi A, Fukada S-i, Yamamoto N, Takeda Si, Tsuchida K. Mesenchymal progenitors distinct from satellite cells contribute to ectopic fat cell formation in skeletal muscle. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:143–152. doi: 10.1038/ncb2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uezumi A, Ito T, Morikawa D, Shimizu N, Yoneda T, Segawa M, Yamaguchi M, Ogawa R, Matev MM, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda Si, Tsujikawa K, Tsuchida K, Yamamoto H, Fukada S-i. Fibrosis and adipogenesis originate from a common mesenchymal progenitor in skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3654–3664. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heredia JE, Mukundan L, Chen FM, Mueller AA, Deo RC, Locksley RM, Rando TA, Chawla A. Type 2 innate signals stimulate fibro/adipogenic progenitors to facilitate muscle regeneration. Cell. 2013;153:376–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uezumi A, Ikemoto-Uezumi M, Tsuchida K. Roles of nonmyogenic mesenchymal progenitors in pathogenesis and regeneration of skeletal muscle. Front Physiol. 2014;5:68. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann CJ, Perdiguero E, Kharraz Y, Aguilar S, Pessina P, Serrano AL, Munoz-Canoves P. Aberrant repair and fibrosis development in skeletal muscle. Skelet Muscle. 2011;1:21. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serrano AL, Munoz-Canoves P. Regulation and dysregulation of fibrosis in skeletal muscle. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:3050–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus RL, Addison O, Kidde JP, Dibble LE, Lastayo PC. Skeletal muscle fat infiltration: impact of age, inactivity, and exercise. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14:362–6. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0081-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natarajan A, Lemos DR, Rossi FM. Fibro/adipogenic progenitors: a double-edged sword in skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2045–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.11.11854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Judson RN, Zhang RH, Rossi FM. Tissue-resident mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in skeletal muscle: collaborators or saboteurs? FEBS J. 2013;280:4100–8. doi: 10.1111/febs.12370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gospodarowicz D. Localisation of a fibroblast growth factor and its effect alone and with hydrocortisone on 3T3 cell growth. Nature. 1974;249:123–7. doi: 10.1038/249123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason I. Initiation to end point: the multiple roles of fibroblast growth factors in neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:583–96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beenken A, Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:235–53. doi: 10.1038/nrd2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4:215–66. doi: 10.1002/wdev.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Fibroblast growth factors: from molecular evolution to roles in development, metabolism and disease. J Biochem. 2011;149:121–30. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohta H, Itoh N. Roles of FGFs as Adipokines in Adipose Tissue Development, Remodeling, and Metabolism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:18. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goetz R, Mohammadi M. Exploring mechanisms of FGF signalling through the lens of structural biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:166–80. doi: 10.1038/nrm3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheehan SM, Allen RE. Skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation in response to members of the fibroblast growth factor family and hepatocyte growth factor. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:499–506. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199912)181:3<499::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastner S, Elias MC, Rivera AJ, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Gene expression patterns of the fibroblast growth factors and their receptors during myogenesis of rat satellite cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:1079–96. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada S, Buffinger N, DiMario J, Strohman RC. Fibroblast growth factor is stored in fiber extracellular matrix and plays a role in regulating muscle hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1989;21:S173–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alterio J, Courtois Y, Robelin J, Bechet D, Martelly I. Acidic and basic fibroblast growth factor mRNAs are expressed by skeletal muscle satellite cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;166:1205–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Moigne A, Martelly I, Barlovatz-Meimon G, Franquinet R, Aamiri A, Frisdal E, Bassaglia Y, Moraczewski G, Gautron J. Characterization of myogenesis from adult satellite cells cultured in vitro. Int J Dev Biol. 1990;34:171–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bischoff R. Proliferation of muscle satellite cells on intact myofibers in culture. Dev Biol. 1986;115:129–39. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olwin BB, Arthur K, Hannon K, Hein P, McFall A, Riley B, Szebenyi G, Zhou Z, Zuber ME, Rapraeger AC, et al. Role of FGFs in skeletal muscle and limb development. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;39:90–100. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080390114. discussion 100–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yayon A, Klagsbrun M, Esko JD, Leder P, Ornitz DM. Cell surface, heparin-like molecules are required for binding of basic fibroblast growth factor to its high affinity receptor. Cell. 1991;64:841–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90512-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuro-o M. Endocrine FGFs and Klothos: emerging concepts. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt KP, Baum MG, Schiavi S, Hu MC, Moe OW, Kuro-o M. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6120–3. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500457200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shefer G, Van de Mark DP, Richardson JB, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Satellite-cell pool size does matter: defining the myogenic potency of aging skeletal muscle. Dev Biol. 2006;294:50–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Rivera AJ. Temporal expression of regulatory and structural muscle proteins during myogenesis of satellite cells on isolated adult rat fibers. Dev Biol. 1994;164:588–603. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Seger R, Rivera AJ. Fibroblast growth factor promotes recruitment of skeletal muscle satellite cells in young and old rats. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:23–42. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwiatkowski BA, Kirillova I, Richard RE, Israeli D, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. FGFR4 and its novel splice form in myogenic cells: Interplay of glycosylation and tyrosine phosphorylation. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:803–817. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Anderson JE. Satellite cells from dystrophic (mdx) mice display accelerated differentiation in primary cultures and in isolated myofibers. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:203–12. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Danoviz ME, Phelps M, Stuelsatz P. Myogenic-specific ablation of Fgfr1 impairs FGF2-mediated proliferation of satellite cells at the myofiber niche but does not abolish the capacity for muscle regeneration. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:85. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fon Tacer K, Bookout AL, Ding X, Kurosu H, John GB, Wang L, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Kuro-o M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Research resource: Comprehensive expression atlas of the fibroblast growth factor system in adult mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:2050–64. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito S, Kinoshita S, Shiraishi N, Nakagawa S, Sekine S, Fujimori T, Nabeshima Y-i. Molecular cloning and expression analyses of mouse βklotho, which encodes a novel Klotho family protein. Mech Dev. 2000;98:115–119. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kume E, Iwasaki H, Iida A, Shiraki-Iida T, Nishikawa S, Nagai R, Nabeshima Y-i. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stuelsatz P, Keire P, Almuly R, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. A contemporary atlas of the mouse diaphragm: myogenicity, vascularity, and the Pax3 connection. J Histochem Cytochem. 2012;60:638–57. doi: 10.1369/0022155412452417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mashili FL, Austin RL, Deshmukh AS, Fritz T, Caidahl K, Bergdahl K, Zierath JR, Chibalin AV, Moller DE, Kharitonenkov A, Krook A. Direct effects of FGF21 on glucose uptake in human skeletal muscle: implications for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:286–97. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phelps M, Pettan-Brewer C, Ladiges W, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Decline in muscle strength and running endurance in klotho deficient C57BL/6 mice. Biogerontology. 2013;14:729–39. doi: 10.1007/s10522-013-9447-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Danoviz ME, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Skeletal muscle satellite cells: background and methods for isolation and analysis in a primary culture system. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;798:21–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-343-1_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gregoire FM, Smas CM, Sul HS. Understanding Adipocyte Differentiation. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:783–809. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mersmann HJ, Goodman JR, Brown LJ. Development of swine adipose tissue: morphology and chemical composition. J Lipid Res. 1975;16:269–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Napolitano L. The differentiation of white adipose cells. An electron microscope study. J Cell Biol. 1963;18:663–679. doi: 10.1083/jcb.18.3.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shefer G, Wleklinski-Lee M, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Skeletal muscle satellite cells can spontaneously enter an alternative mesenchymal pathway. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5393–5404. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Starkey JD, Yamamoto M, Yamamoto S, Goldhamer DJ. Skeletal muscle satellite cells are committed to myogenesis and do not spontaneously adopt nonmyogenic fates. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:33–46. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.956995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Braiterman L, Nyasae L, Guo Y, Bustos R, Lutsenko S, Hubbard A. Apical targeting and Golgi retention signals reside within a 9-amino acid sequence in the copper-ATPase, ATP7B. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G433–G444. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90489.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Triantis V, Saeland E, Bijl N, Oude-Elferink RP, Jansen PL. Glycosylation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 is a key regulator of fibroblast growth factor 19-mediated down-regulation of cytochrome P450 7A1. Hepatology. 2010;52:656–66. doi: 10.1002/hep.23708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rangwala SM, Lazar MA. Transcriptional control of adipogenesis. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:535–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Graves RA, Budavari AI, Spiegelman BM. mPPAR gamma 2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1224–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fisher FM, Chui PC, Antonellis PJ, Bina HA, Kharitonenkov A, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E. Obesity is a fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)-resistant state. Diabetes. 2010;59:2781–9. doi: 10.2337/db10-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coskun T, Bina HA, Schneider MA, Dunbar JD, Hu CC, Chen Y, Moller DE, Kharitonenkov A. Fibroblast growth factor 21 corrects obesity in mice. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6018–27. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kharitonenkov A, Larsen P. FGF21 reloaded: challenges of a rapidly growing field. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishimura T, Nakatake Y, Konishi M, Itoh N. Identification of a novel FGF, FGF-21, preferentially expressed in the liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1492:203–6. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Izumiya Y, Bina HA, Ouchi N, Akasaki Y, Kharitonenkov A, Walsh K. FGF21 is an Akt-regulated myokine. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3805–10. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cuevas-Ramos D, Almeda-Valdes P, Meza-Arana CE, Brito-Cordova G, Gomez-Perez FJ, Mehta R, Oseguera-Moguel J, Aguilar-Salinas CA. Exercise increases serum fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) levels. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raschke S, Eckel J. Adipo-myokines: two sides of the same coin--mediators of inflammation and mediators of exercise. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:320724. doi: 10.1155/2013/320724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding X, Boney-Montoya J, Owen BM, Bookout AL, Coate KC, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. betaKlotho is required for fibroblast growth factor 21 effects on growth and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2012;16:387–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang C, Jin C, Li X, Wang F, McKeehan WL, Luo Y. Differential specificity of endocrine FGF19 and FGF21 to FGFR1 and FGFR4 in complex with KLB. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adams AC, Cheng CC, Coskun T, Kharitonenkov A. FGF21 requires βklotho to act in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adams AC, Yang C, Coskun T, Cheng CC, Gimeno RE, Luo Y, Kharitonenkov A. The breadth of FGF21’s metabolic actions are governed by FGFR1 in adipose tissue. Mol Metab. 2013;2:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luo Y, McKeehan WL. Stressed liver and muscle call on adipocytes with FGF21. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013;4:194. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogawa Y, Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt KP, Goetz R, Eliseenkova AV, Mohammadi M, Kuro-o M. βKlotho is required for metabolic activity of fibroblast growth factor 21. PNAS. 2007;104:7432–7437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suzuki M, Uehara Y, Motomura-Matsuzaka K, Oki J, Koyama Y, Kimura M, Asada M, Komi-Kuramochi A, Oka S, Imamura T. betaKlotho is required for fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 21 signaling through FGF receptor (FGFR) 1c and FGFR3c. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1006–14. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurosu H, Choi M, Ogawa Y, Dickson AS, Goetz R, Eliseenkova AV, Mohammadi M, Rosenblatt KP, Kliewer SA, Kuro-o M. Tissue-specific Expression of βKlotho and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Receptor Isoforms Determines Metabolic Activity of FGF19 and FGF21. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26687–26695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704165200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kanisicak O, Mendez JJ, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto M, Goldhamer DJ. Progenitors of skeletal muscle satellite cells express the muscle determination gene, MyoD. Dev Biol. 2009;332:131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stuelsatz P, Shearer A, Li Y, Muir LA, Ieronimakis N, Shen QW, Kirillova I, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Extraocular muscle satellite cells are high performance myo-engines retaining efficient regenerative capacity in dystrophin deficiency. Dev Biol. 2015;397:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Blau HM, Chiu C-P, Webster C. Cytoplasmic activation of human nuclear genes in stable heterocaryons. Cell. 1983;32:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yaffe D, Saxel O. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature. 1977;270:725–727. doi: 10.1038/270725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jainchill JL, Aaronson SA, Todaro GJ. Murine Sarcoma and Leukemia Viruses: Assay Using Clonal Lines of Contact-Inhibited Mouse Cells. J Virol. 1969;4:549–553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.4.5.549-553.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu Z, Xie Y, Bucher NL, Farmer SR. Conditional ectopic expression of C/EBP beta in NIH-3T3 cells induces PPAR gamma and stimulates adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2350–2363. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ramírez-Zacarías JL, Castro-Muñozledo F, Kuri-Harcuch W. Quantitation of adipose conversion and triglycerides by staining intracytoplasmic lipids with oil red O. Histochemistry. 1992;97:493–497. doi: 10.1007/BF00316069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Day K, Shefer G, Richardson JB, Enikolopov G, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Nestin-GFP reporter expression defines the quiescent state of skeletal muscle satellite cells. Dev Biol. 2007;304:246–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Spandidos A, Wang X, Wang H, Seed B. PrimerBank: a resource of human and mouse PCR primer pairs for gene expression detection and quantification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D792–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Deng C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Zhou F, Kuo A, Leder P. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is a negative regulator of bone growth. Cell. 1996;84:911–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pahl HL, Baeuerle PA. The ER-overload response: activation of NF-kappa B. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:63–7. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]