Abstract

There is a significant need for developing compounds that kill Cryptococcus neoformans, the fungal pathogen that causes meningoencephalitis in immunocompromised individuals. Here, we report the mode of action of a designed antifungal peptide, VG16KRKP (VARGWKRKCPLFGKGG) against C. neoformans. It is shown that VG16KRKP kills fungal cells mainly through membrane compromise leading to efflux of ions and cell metabolites. Intracellular localization, inhibition of in vitro transcription, and DNA binding suggest a secondary mode of action for the peptide, hinting at possible intracellular targets. Atomistic structure of the peptide determined by NMR experiments on live C. neoformans cells reveals an amphipathic arrangement stabilized by hydrophobic interactions among A2, W5, and F12, a conventional folding pattern also known to play a major role in peptide-mediated Gram-negative bacterial killing, revealing the importance of this motif. These structural details in the context of live cell provide valuable insights into the design of potent peptides for effective treatment of human and plant fungal infections.

Introduction

Opportunistic fungal infections are on the rise, exhibiting very high morbidity and mortality rates in immunocompromised individuals including HIV patients, cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, and individuals who have undergone solid organ transplantations (1, 2, 3). Cryptococcus neoformans is a major opportunistic fungal pathogen, linked to cryptococcosis, which may cause infection in cutaneous, pulmonary regions or even in the brain meninges (4,5). Cryptococcal meningitis is a fatal disease especially seen in HIV patients, affecting >1,000,000 people annually and leading to a death toll of ∼70,000 worldwide (2, 3, 4). Hence, cryptococcosis among other invasive fungal infections, is a challenging problem that requires concentrated efforts toward development of new antifungal agents. The current therapeutics approaches mainly include the azole group of drugs (amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine, and echinocandins, among others). Most of these are limited by their cytotoxic effects on the host, limited efficacy, or development of resistance in the pathogen upon long-term usage (4, 5, 6, 7). In addition, sessile biofilms act as a store house for antibiotic tolerant fungal cells that can lead to persistent systemic infections (8, 9). The lack of antifungal agents active against biofilm-forming varieties increases the urgent need for novel agents in the drug pipeline (5, 10).

Cationic antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), present in all forms of life, are the first line of host defense. They are small molecules of 12–50 amino acid residues with diverse structural attributes, and display a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activities with unconventional targets and modes of action (11, 12, 13). They kill microorganisms using various strategies that include membrane disruption as the chief mechanism, apart from having downstream intracellular targets (14). They offer themselves as attractive substitutes for conventional small molecule drugs in view of their membrane disruption properties that allow them to circumvent the development of resistance in microbial targets (3, 15, 16, 17, 18). A number of these naturally occurring molecules are endowed with antimicrobial activities; however, their use is restricted to topical applications owing to their cytotoxicity (19). Extensive research in this field has led to the development of synthetically designed AMPs and peptidomimetics having in vitro antimicrobial activity and reduced cytotoxicity making them suitable candidates for antimicrobial drug design (20, 21, 22). Synthetically designed peptides have opened up immense opportunities in the field of drug design allowing modification to obtain optimal potency and selectivity. In an earlier report a nontoxic and nonhemolytic 16-residue AMP, VG16KRKP (VARGWKRKCPLFGKGG) was designed using first principles; the peptide showed potential activity against Gram-negative plant pathogenic bacteria as well as opportunistic fungal pathogens such as Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans. Mode of action of the peptide against Gram-negative bacteria was elucidated from a structural aspect based on solution NMR structure of the peptide in lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a chief component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria (23). However, its mode of antifungal action remained unexplored. It is worth mentioning that the membrane architectures of Gram-negative bacteria and fungi are different. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to provide a comprehensive investigation of the anticryptococcal activity of VG16KRKP from both functional and structural aspects. Most of the AMP structures reported till date have been described in the context of membrane mimicking environments. However, these mimics may not account for the exact interactions of the peptide with live cells, which in turn might have important implications. Thus, our focus is to provide mechanistic insight at atomic resolution in the context of live cells, enabling a correlation between structure and function. Our study reveals that VG16KRKP exhibits its antifungal effects primarily through membrane compromise, depolarization, and efflux of cell metabolites and ions. It is also seen to be localized inside the cell at sublethal doses and is thought to have intracellular targets, displaying DNA binding abilities and transcription inhibition in vitro. Thus, we propose a dual mode of action for the designed peptide and firmly believe that such studies will be instructive in determining rules for the design of potent antifungal peptides whose folded structures can be stabilized on the fungal cell surface, aiding in enhanced membrane disruption.

Materials and Methods

Peptide synthesis

The peptides VG16KRKP and FITC-VG16KRKP with 95% purity were purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai, China). The purity was further confirmed by HPLC, mass spectrometry, and NMR spectroscopy. One-millimolar stock solutions of peptide in sterile water were used for all assays except NMR. The stock solutions were kept at 4°C for storage. Peptide in its powder form was kept at −20°C for long-term storage.

Antimicrobial activity assay

Dose response assays were performed with C. neoformans at two different cell concentrations (105 and 106 cells/mL) in a 96-well plate format where midlog phase cells were washed three times with 10 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.4 and resuspended in the same buffer to obtain required cell numbers considering 1 OD correspond to ∼107 cells. Fifty microliters of cell suspension was incubated with 50 μL of phosphate buffer containing peptide in varying concentrations (0, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 25, 50, and 100 μM) and incubated at 30°C for 6 h. One-hundred-ninety microliters of YPD was added to each well and incubated for 36 h and read at 630 nm. The experiment was conducted three times, and average values were reported.

Time kill experiments

Overnight grown cultures of C. neoformans in YPD broth were washed twice and diluted to 105 cells/mL in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). A reaction in a final volume of 1 mL containing 100 μL of above cell suspension, 10 μL of the peptide, and buffer was set. At each time interval of 15 min for a period of 6 h, 100 μL of the above reaction mixture was taken out and serially diluted (10-fold dilution) twice. Approximately 100 μL of the least diluted culture was spread on YPD plates in triplicate, which was then incubated overnight at 30°C. The total number of colony-forming units on the plates was counted. Percentage viability of C. neoformans was plotted against time. The experiment was conducted independently three times, and the average values were reported.

Live-dead staining assay

The C. neoformans cells were grown overnight in YPD medium, harvested, and resuspended in buffer to get a cell density of 105 cells/mL or 106 cells/mL as described above. These cells were then treated with peptide at a concentration of 10 μM for 6 h. A control set of cells without peptide treatment was also used for analysis. After 6 h of treatment, the cells were stained to determine live-dead cell populations (24) as described in the Supporting Material.

Scanning electron microscopy

Overnight-grown C. neoformans culture was washed twice and resuspended at 105 cells/mL in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and incubated with the peptide at its MIC100% value (10 μM) in a final volume of 1 mL, at 30°C. After every 15 min (until 1.5 h), 100 μL of the fungal suspension was aliquoted and incubated with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 h. After fixation, the suspension was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 2 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed and resuspended in 10 μL of buffer and placed on poly-L-lysine coated slides. The slides were air-dried for 30 min followed by dehydration with graded series of ethanol. Controls were run in the absence of peptide using the same protocol. Samples were gold-coated and observed under the scanning electron microscope.

Zeta-potential measurements

For zeta-potential measurements of C. neoformans upon treatment with VG16KRKP a Nano S ZEN3690 (Malvern Instruments, Westborough, MA) was employed using a method described in Arakha et al. (25). The details of the method can be found in the Supporting Material.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

All fluorescence spectroscopic experiments were carried out in a model No. F-700 FL spectrometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) in a quartz cuvette with a path length of 0.1 cm. To elucidate the binding interactions of the peptide with the fungus, the intrinsic Trp fluorescence of peptide was monitored upon addition of increasing volumes of 1 OD C. neoformans cell suspension to 5 μM of peptide solution. All stocks and solutions were prepared in 10 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.2. The sample was excited at 280 nm and the emission spectrum was measured at a range of 300–400 nm at a temperature of 25°C. Both excitation and emission slits were set at 5 nm.

DAPI fluorescence experiments were also performed to study minor groove binding of VG16KRKP to DNA (GG28). One micromolar DAPI in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 alone and in the presence of 2 μM GG28 was excited at 372 nm and its emission scanned from 400 to 520 nm. Increasing concentrations of VG16KRKP ranging from 2 to 24 μM was added and its emission spectrum was monitored at 25°C.

1-N-phenylnaphthylamine dye uptake assay

C. neoformans was grown overnight in YPD broth. Cells were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 3 min. Cell pellet was washed with 10 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.4 three times and resuspended to an OD600 of 0.5. 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine (NPN), a hydrophobic dye, was added to the cells at a concentration of 10 μM from stock solutions made in acetone and left to stabilize for 30 min. Increasing concentrations of peptide, ranging between 5 and 20 μM, were added to the cells, and the subsequent enhancement in NPN fluorescence, owing to a disruption in the outer membrane, was measured on a model No. F-7000FL spectrophotometer (Hitachi). A quantity of 0.1% Triton X-100 served as a positive control. Excitation and emission was carried out at 350 and 410 nm, respectively, with a bandwidth of 5 nm. The percentage increase in NPN fluorescence was calculated using:

| (1) |

where F is fluorescence intensity after addition of peptide, F0 is basal fluorescence intensity, and FT is maximum fluorescence intensity after addition of 0.1% Triton X 100.

Calcein leakage assay

Approximately 2 mg each of POPE, POPC, cholesterol (Chl), and ergosterol (ERG) were weighed and dissolved in chloroform (CHCl3) to obtain stock solutions. Required amounts of suspended lipid stocks were mixed to obtain POPC/POPE/ERG in a molar ratio of 5:4:3, with POPC and 40% cholesterol, followed by drying in a nitrogen stream and overnight lyophilization to form a lipid film. The film was resuspended in buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and 70 mM calcein, by vortexing vigorously for 30 min followed by five freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen to obtain calcein-entrapped vesicles. The suspension was passed through a mini extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) using two-stacked 100-nm pore-size polycarbonate membrane filters to obtain unilamellar vesicles. Samples were typically subjected to 23 passes through filter. An odd number of passages was performed to avoid contamination of the sample by vesicles that have not passed through the first filter. Next, to eliminate free calcein, it was loaded on to a gel filtration-based hydrated Centrisep-Spin Column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 2 min to obtain a light orange iridescent suspension. Six-hundred microliters of extravesicular buffer (10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing calcein entrapped lipid vesicles was read in a fluorimeter using excitation at 490 nm and emission at 520 nm with a slit of 2.5 nm. After stabilization of calcein fluorescence, peptide in increasing concentrations was added and fluorescence enhancement was measured after 5 min of each addition. A quantity of 0.1% Triton X100 was used to obtain maximum fluorescence intensity. Percent leakage was calculated using:

| (2) |

where F is the fluorescence intensity after addition of peptide, F0 is the basal fluorescence intensity, and FT is the maximum fluorescence intensity after addition of Triton X100.

Flow cytometry analysis

C. neoformans cells were grown and diluted to 106 cells/mL, as described earlier. A set of cells (1 mL) was then treated with a sublethal dose (10 μM) of peptide for 6 h at 30°C whereas another set was kept untreated with peptide. After 6 h of the peptide-treated cells, 2 mL of YPD was added in these tubes and further incubated at 30°C for 4 h. The cells were then harvested from both treated and untreated samples and processed for flow cytometry analysis. One set of cells was harvested at the beginning of the experiment and processed for analysis to determine the profile of starting culture. The harvested cells (all three samples) were fixed in 70% ethanol for 14–16 h, washed with 1 mL of NS buffer, and finally resuspended in 200 μL of NS buffer. These cells were then treated with RNase at a concentration of 100 μg/mL for 4 h. Following this, the cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) for 30 min and analyzed using the FACSCalibur system (30,000 events; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Confocal laser-scanning microscopy

Overnight cultures of wild-type C. neoformans or a histone H4-mCherry tagged strain of C. neoformans were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and resuspended to obtain a suspension of 106 cells/mL. One-hundred microliters of this suspension were incubated with a sublethal dose (10 μM) of FITC-VG16KRKP at 37°C for 8 h. At different time points, 20 μL of the treated cells were aliquoted, centrifuged, washed with buffer, loaded on a glass slide, and mounted with DPX (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). A sample containing only fungal suspension was also processed as above, to serve as the control. Fluorescent and differential interference contrast images were captured with a 488-nm band-pass filter for excitation of FITC and a 587 nm band-pass filter for excitation of mCherry using a No. TCS SP8 confocal microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) at a magnification of 63× (oil immersion) having a numerical aperture of 1.4. Acquisition Suite X software (Leica) was used for capturing images.

Fluorescence-based in vitro transcription assay

E. coli RNA polymerase and σ70 were purified as previously described in Mukhopadhyay et al. (26). Four-hundred nanomolar of E. coli RNAP core and 800 nM of σ70 were incubated in 4 μL Transcription buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 50 nM BSA, and 5% glycerol) at 25°C for 20 min to form holo enzyme. A quantity of 500 ng of pUC19-lacCONS plasmid DNA samples (27) along with 0, 1, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 μM of VG16KRKP in 6 μL transcription buffer were added to the RNAP holo enzyme and incubated at 25°C for 20 min. The samples were further incubated at 37°C for 15 min to form an open complex. Transcription reactions were initiated by addition of 250 μM of NTP and were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 U of RNase-free DNase, followed by incubation for 30 min at 37°C. After DNase digestion, the samples were diluted to 10-fold with TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA). One-hundred microliters of RiboGreen dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (diluted to 20,000 folds in TE buffer) were added to samples and incubated for 5 min at 25°C. Fluorescence intensities of the samples were monitored using a spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International, HORIBA Scientific, Edison, NJ) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 495 and 535 nm, respectively.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

A model No. J-815 spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Peltier cell holder and temperature controller CDF-426 L was used for the circular dichroism (CD) experiments. Twenty micromolar of either GG28 or GC28 DNA alone in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 was scanned from a range of 320–210 nm at a scanning speed of 100 nm/min with data points collected at every nanometer, and for four repetitive scans that were finally averaged out. Titrations were carried out at 25°C with increasing concentrations of VG16KRKP starting from 20 to 100 μM. CD melting experiments were also carried out with DNA alone and in presence of VG16KRKP in a DNA/peptide ratio of 1:5 for both GG28 and GC28 sequences. The samples were heated from 5 to 95°C using a heating rate of 2.5°C/min. At each temperature, the sample cell was equilibrated for 5 min before data acquisition. A stream of dry nitrogen gas was used to flush the cuvette chamber to avoid water vapor condensation at low temperatures. All experiments were performed in a quartz cuvette of 2-mm path length. The data was converted to molar ellipticity (deg.cm2.dmol−1) for data analysis. The fractions of GG28 and GC28 in their duplex state were calculated using Eq. 3 and plotted against temperature (28). A sigmoidal curve fitting assuming two-state models was carried out to obtain the melting temperature (Tm) using the equation

| (3) |

where θt = observed CD value in millidegrees (mdeg) at temperature T. The values θd and θs are the observed CD values in mdeg when DNA is in fully double- and single-stranded conformation, respectively. The resultant duplex fraction α was fitted equation against different temperatures T to obtain the melting temperature (Tm) using Eq. 4 to fit. In Eq. 4, a and b correspond to adjustable fitting constraints.

| (4) |

The thermodynamic parameters, i.e., ΔH, ΔG, and ΔS, were calculated for the DNA alone and then in the presence of peptide, using the van ’t Hoff equation given in Mergny and Lacroix (29) and Breslauer (30).

NMR spectroscopy

The NMR samples were prepared in 90% 10 mM phosphate buffer of pH 5.5 or pH 7.2 containing 10% D2O, or in 100% deuterated 10 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.2. 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate sodium salt was used as an internal chemical shift standard. NMR spectra used in this study were collected at 25°C using either a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz or Bruker Avance III 700 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm cryo-probe. A series of one-dimensional (1D) 1H proton NMR spectra for both the free DNA duplex GG28 as well as the VG16KRKP-bound DNA at a molar ratio of DNA/VG16KRKP = 1:1, were recorded using a Bruker Avance III 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm cryo-probe. The 1D spectrum was acquired using excitation-sculpting scheme for water suppression. The acquisition parameters were, 20 ppm for spectral width and 128 transients, a relaxation delay of 2 s, and an acquisition delay of 1.7 s. The spectra were processed and plotted with Topspin software suite (Bruker) using a line-broadening factor of 1.0 Hz.

One-dimensional proton NMR spectra of 1 mM VG16KRKP, dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer of pH 5.5 and 10% D2O at 25°C, was carried out using a Bruker Avance III 700 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm cryo-probe. A series of titrations was carried out with living C. neoformans cells suspended in phosphate buffer of similar pH, until broadening of the 1D 1H spectra of VG16KRKP was observed. Two-dimensional (2D) homonuclear total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) and transferred nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (tr-NOESY) experiments with mixing times of 80 and 150 ms, respectively, were set up with a spectral width of 12 ppm in both dimensions. Number of scans for tr-NOESY and TOCSY were 24 and 16, respectively, per t1 increment with 16 dummy scans. The experiments were performed with 456 increments in t1 and 2048 data points in t2 dimension, States TPPI (31) for quadrature detection in t1 dimension and WATERGATE for water suppression (32). For processing the TOCSY and tr-NOESY spectra 4 K (t2) and 1 K (t1) data matrices were used after zero filling. Details of the calculation of solution NMR structures can be found in the Supporting Material.

For live cell NMR experiments, 1 mM VG16KRKP solution, made with 90% of 10 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.2 and 10% D2O were prepared. One-dimensional proton NMR spectra of VG16KRKP at 25°C was carried out on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz NMR spectrometer (equipped with smart probe), followed by a series of 1D titrations using C. neoformans cell suspensions (OD600 = 1.0) in same buffer amounting to a final range of ∼107 cells.

For live cell STD experiments, a 1 mM VG16KRKP solution was prepared in 10 mM deuterated phosphate buffer of pH 7.2 to rule out the possibility of peptide resonance suppression by water (33, 34). Similarly, a live C. neoformans cell suspension of OD600 = 1.0 was prepared in the same buffer. A standard STD pulse program was used to run the experiment at 25°C (34, 35). A selective saturation frequency of −1 ppm and an off-resonance frequency of 40 ppm for the reference spectrum were used. The saturation frequency was used to selectively saturate the cells whereas the off-resonance corresponded to such a resonance where neither the cell nor the peptide spectrum saw any resonances. An STD experiment was run in three sets for (1) peptide alone, (2) cells alone, and (3) peptide in the presence of cells. A cycle of 40 Gaussian-shaped pulses (49 ms, 1 ms delay between pulses), with a total saturation time of 2 s was used as in Bhunia and Bhattacharjya (36). A spectral width of 12 ppm, with 512 and 1024 scans, was maintained for reference and STD spectra, respectively. A relaxation delay of 1 s and 16 dummy scans was kept constant for both STD and reference spectra. An exponential line broadening function of 5 Hz was multiplied with all STD 1D spectra before Fourier transformation.

Docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies

Docking of VG16KRKP and GG28 was performed using the Z-Dock server (37). The coordinates for peptide were derived from NMR spectroscopy and that for duplex DNA was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB: 2M2C) (38). Residue-specific interaction was based on the finding of NMR relaxation study, which was used as input for iterative docking calculations. With the energy-minimization process, the complex was subjected to NPT simulation with gradual increase of system temperature in a gradual increment order. The protocol for temperature increments is 0–150 K (5 ps), 150–250 K (5 ps), 250–325 K (5 ps), and 325–300 K (5 ps), with integration steps of 0.5 fs at a temperature-coupling constant of 1.0 ps. In addition to this, a constant temperature timescale was also employed such that the temperature distribution across the system can be uniform. The retrieved complex was energy minimized using the AMBER ff99SB-ildn force field (39). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was further carried out with same force field using the dipole-effect of water (implicit simulation conditions). Final MD production run was processed for a timescale of 15 ns, which was analyzed for the secondary structure of peptide in bound condition to the duplex DNA. The trajectory was saved at the 5 ps mark, which was analyzed using VMD (40).

A detailed description of the dynamic behavior for VG16KRKP bound to GG28 (duplex DNA) can be found in Movie S1.

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy

Details of solid-state NMR sample preparation can be found in the Supporting Material. NMR experiments were performed on a 600 NMR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) operating at the resonance frequency of 599.88 MHz for 1H and 283.31 MHz for 31P nuclei using a 4 mm MAS HXY Probe (Agilent Technologies). 31P NMR experiments were performed using a 90° pulse (6.8 μs duration) and 24 kHz TPPM proton decoupling. In all cases, a total of 3000 scans were acquired for each sample with a relaxation delay time of 3 s. LUVs were put in a 4 mm Pyrex glass tube (Corning, Corning, NY), which was cut to fit into the MAS probe. A temperature control unit (Agilent Technologies) was used to maintain the sample temperature at 30 or 45°C. 31P NMR spectra of LUVs without peptide were first collected and an appropriate amount of peptide (2 and 4 mol %) from a stock solution in buffer was then added; the mixture was gently shaken before the sample was placed back into the magnet for 31P NMR experiments. All 31P NMR spectra were processed using 300 Hz line broadening referenced externally to 85% phosphoric acid (0 ppm).

Results and Discussion

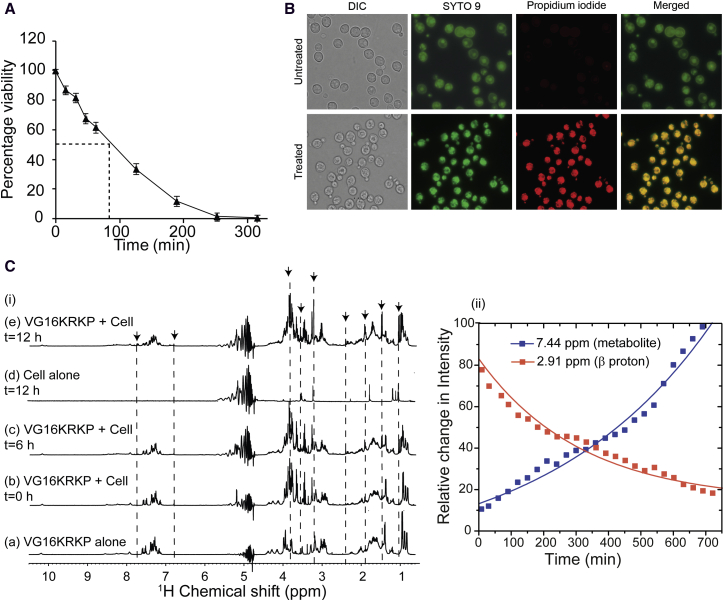

VG16KRKP kills C. neoformans primarily through membrane compromise and cell content leakage

From the dose response assay (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material) it was found that VG16KRKP (VARGWKRKCPLFGKGG) killed C. neoformans cells (105 cells/mL) completely at 10 μM concentrations (Fig. S1 A, left panel) while 106 cells/mL required much higher concentrations (100 μM) of peptide (Fig. S1 A, right panel). The time-dependent killing of fungal cells (105 cells/mL) was detected as early as 15 min after treatment with the peptide at its MIC, and it killed almost 50% of cells within 90 min (Fig. 1 A). A staining assay that differentiates live and dead cells also showed almost 100% killing of cells within 6 h when 105 cells/mL concentration was used (Fig. 1 B). When a higher concentration of cells (106/mL) was treated with 10 μM peptide, only 70–80% of cells showed staining after 6 h of treatment (Fig. S1 B). The efflux of metabolites from cells upon treatment with the peptide was also clearly demonstrated by live cell NMR experiments where new peaks appearing over time corresponded to metabolites from C. neoformans cells. These new peaks were observed almost immediately after addition of cells to the peptide (Fig. 1 C i b), and showed a time-dependent increase in intensity (highlighted with arrows and dotted lines) in the 1D 1H NMR spectra of the peptide (Fig. 1 C, i c and e and ii). In addition, an interaction of the peptide with the cell surface was also observed, which is reflected by the broadening of the peptide signal associated with a gradual reduction in 1H signal intensities with time (Figs. 1 C ii and S1, C and D). In addition, cell surface binding of VG16KRKP with live C. neoformans cells was also studied using the intrinsic Trp fluorescence of VG16KRKP. Upon addition of live cells to VG16KRKP showed a significant 14 nm blue shift in its emission maxima, indicating binding of the peptide to live cells (Fig. S1 E).

Figure 1.

Killing kinetics of Cryptococcus upon treatment with VG16KRKP. (A) Time kill curve of C. neoformans upon treatment with VG16KRKP. (B) Fluorescence-based live-dead staining to show the differentially stained cells after treatment with the peptide. The treated cells are stained with both SYTO9 and PI whereas untreated cells are only stained with SYTO9 but not with PI. (C) (i) 1D 1H proton NMR spectra of VG16KRKP alone (a); VG16KRKP upon addition of C. neoformans cells at different time points (b, c, and e) and C. neoformans cell alone incubated for 12 h (as control) (d). The spectrum of VG16KRKP in the presence of cell shows line-broadening effects, without changing the chemical shift, indicating the binding of the peptide to the cells. In contrast, appearance of new peaks in the spectrum in either the presence or absence of peptide corresponds to release of cell metabolites from the cell. (C) (ii) Plot showing the decrease in peptide resonance intensities (CβH protons of VG16KRKP) and at the same time increase in metabolite resonance intensities indicating binding and membrane disruption, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

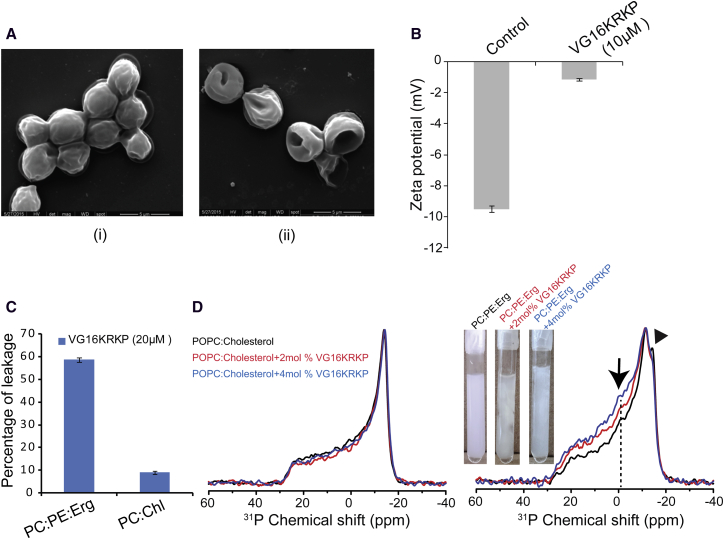

Further studies employing scanning electron microscopy of the C. neoformans cells treated with peptide at its MIC100% for similar time periods showed a shrinkage in cell volume within 15 min (Fig. S1 F i) and it continued to increase with time of incubation (Fig. S1 F ii). The cell morphology of peptide-treated cells indicated a morbid effect of the peptide on cell wall/cell membrane. The membrane integrity of the cell was visibly shrunken at ∼45 min (Fig. 2 A ii) and cells adopted crescent or bowl-shaped forms at 90 min posttreatment (Fig. S1 F iii). These data could be correlated with Fig. 1 C that a peptide-mediated osmolytic shock leads to an efflux of cell contents eventually causing cell death. Similar observation was also obtained previously for killing of C. neoformans by dendritic cell lysosomal enzyme cathepsin B (41). Because osmolytic shock and membrane depolarization are interlinked, and act as a common mode of action of antimicrobial peptides (42), zeta-potential measurements of the C. neoformans cell surface were carried out after peptide treatment. Zeta-potential of the cells in the absence of peptide was –10 mV (Fig. 2 B), whereas it reached nearly to zero in the presence of peptide, indicating depolarization and an efflux of ions across the cell surface (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

Membrane compromise and depolarization upon treatment with VG16KRKP. (A) Scanning electron microscopy images showing control (i) and peptide-treated (ii) C. neoformans cells, 45 min posttreatment that indicate cell shrinkage due to osmolytic shock. (B) Bar plot showing ζ-potential of C. neoformans cells in the absence and upon treatment with VG16KRKP, indicating depolarization of the membrane posttreatment. (C) Bar plot showing percentage of calcein leakage from POPC/POPE/ERG (5:4:3) LUVs and POPC/40% Cholesterol (Chl) vesicles upon treatment with VG16KRKP indicating membrane-perturbing abilities of the peptide and cell selectivity. (D) 31P solid state NMR spectra of POPC LUVs incorporated with 40% Cholesterol (Chl) (left) and 5:4:3 POPC/POPE/ERG LUVs (right). Both samples were treated with 0 mol % (black), 2 mol % (red), and 4 mol % (blue) VG16KRKP peptides. For the latter case, pictures (inset) showed the LUV samples after the addition of the peptide and aggregation of the LUVs is clearly seen. Arrows indicate the changes upon addition of peptide to the POPC/POPE/ERG LUV. To see this figure in color, go online.

The membrane disruption of C. neoformans cells by VG16KRKP was also supported by NPN dye uptake assay. NPN, a hydrophobic dye, is unable to penetrate the cell membrane, but we observed a 35% dye uptake upon addition of 5 μM of VG16KRKP, demonstrating the insertion of the dye into the hydrophobic environment owing to perturbation of the membrane integrity (Fig. S1 G). Additionally, a calcein leakage assay using lipid vesicles of POPC/POPE/Ergosterol (POPC/POPE/ERG) with a molar ratio of 5:4:3, mimicking the fungal membrane (43), was performed and revealed a 60% leakage upon addition of VG16KRKP, confirming membranolytic capabilities of the peptide (Fig. 2 C). However, vesicles composed of POPC with 40% cholesterol, that mimic the mammalian cell membrane, demonstrated a negligible amount (∼9%) of leakage at the same concentration of peptide. These results further support the fact that the VG16KRKP peptide is highly selective and is nontoxic toward mammalian membranes, which is consistent with our previous study (23). Further, 31P solid-state NMR spectra of POPC LUVs in the presence of physiological cholesterol concentration (∼40%) showed no distortion of the lamellar phase line shape and absence of isotropic peak at 0 ppm even in the presence of VG16KRKP upto 4 mol % concentration. By contrast, POPC/POPE/ERG with a molar ratio of 5:4:3 LUVs showed a typical 31P powder pattern spectra of POPC and POPE in the absence of VG16KRKP, confirmed by spectral simulation with perpendicular edge of –12 and –15 ppm for POPE and POPC, respectively (Fig. S1 H). Upon addition of the VG16KRKP peptide into the POPC/POPE/ERG (5:4:3) LUVs, the perpendicular edges of the POPC and POPE were not distinguishable and the relative intensity of the parallel edges increased (Fig. 2 D). These data suggest that the spherical shape of the LUVs is deformed/aggregated in the presence of peptide, as seen in the picture in inset. An almost negligible intense isotropic peak at ∼0 ppm was observed at 2 and 4 mol% of the peptide (Fig. 2 D), indicating that the peptide interacts selectively with lipids and does not fragment the lipid bilayer to give an isotropic peak like that observed for MSI-78, which is known to support a carpeting mechanism (17). Therefore, it may be possible that the peptide acts by causing transient membrane permeation/pore formation without causing fragmentation that cannot be detected by 31P NMR. Taken together, the peptide is selective having the ability to discriminate between fungal and mammalian cell membrane. This is mainly due to the well-known fact that the presence of cholesterol in mammalian membrane has a major contribution toward the observed inhibitory effects on cationic AMPs. However, it is interesting to note that ergosterol, present in the fungal membrane has a similar inhibitory effect to that of cholesterol toward AMPs but to a much lesser extent. In addition, quite a few AMPs having antifungal activity do not seem to cause membrane disruption, instead undergo cellular uptake via receptors or through transient pores (44).

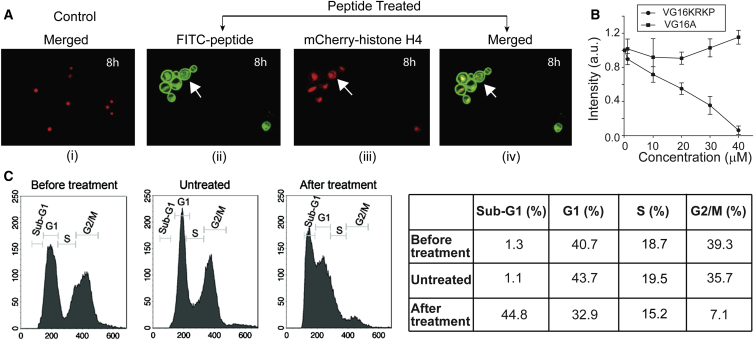

The peptide, VG16KRKP, can be nuclear-localized to inhibit transcription

Creation of transient pores may not be able to kill all cells within 3 h of treatment. Hence, to understand possible intracellular interactions of the peptide, we used FITC tagged peptide to determine its intracellular localization within the cells. C. neoformans cells expressing mCherry-tagged histone H4 (Figs. 3 A i and S2 A i) were used as a marker for chromatin to probe its possible interaction with DNA. It should be noted that histone H4 is one of the major constituents of chromatin in eukaryotic cells. We observed the peptide to be localized mostly at the cell membrane 2 h posttreatment (Fig. S2 A, ii, iii, and iv), with a minority of cell population showing some amount of peptide inside the cell (marked by an arrow). At 4 h posttreatment, the peptide was found to be located at the membrane as well as at the nucleus in some of the cells (Fig. S2 A, v, vi, and vii) as evident from colocalization of green (FITC-peptide) and red fluorescence (H4-mCherry). At 8 h posttreatment, a complete colocalization of red and green fluorescence was observed in most cells indicating localization of the peptide in the nucleus in addition to other cellular compartments including the cell membrane (Figs. 3 A ii, iii, and iv and S2 A viii, ix, and x). Moreover, the nucleus also seemed to be visibly enlarged and dispersed in some cells (marked by arrows), hinting at nuclear fragmentation. To validate further the intracellular localization of the peptide, we prepared spheroplasts of C. neoformans by removing the cell wall using enzymatic digestion (45). When this spheroplast preparation was treated with 1 μM concentration of the FITC-peptide, the peptide showed a similar localization pattern as seen in intact cells 8 h posttreatment (Fig. S2, B and C). Therefore, we hypothesized that the peptide can interact with DNA if entry into the cells is facilitated. This interaction can cause interference in vital processes such as replication or transcription that can eventually lead to cell death. To support this hypothesis, we also performed an in vitro transcription assay using bacterial model of transcription. The assay with E. coli RNAP-sigma70 holoenzyme and VG16KRKP or a control peptide VG16A (VARGWGNGCGLFGKGG) showed that VG16KRKP was able to inhibit transcription with an IC50 value of ∼20 μM, while the control peptide VG16A showed no apparent inhibition (Fig. 3 B). We also carried out flow cytometry analysis of C. neoformans cells in presence or absence of sublethal doses of the peptide. As expected, the starting cell culture contained a mixed population of cells in G1, S, or G2/M phases of the cell cycle (Fig. 3 C). Surprisingly, after peptide treatment, the mitotic cell population was found to be significantly reduced to ∼7%. Moreover, in the peptide-treated cell profile, an additional sub-G1 peak, which probably corresponds to the dead cells (∼45%), was seen. The control peptide-untreated cells, on the other hand, did not show any significant difference in distribution of cells in various stages of the cell cycle as compared to the starting culture (Fig. 3 C, right panel). Accumulation of cells at interphase (G1 and S phases) suggests that the peptide could be inhibiting some vital processes such as DNA replication or transcription by binding directly to DNA. However, it may also cause fragmentation of nuclear material by DNA damage mechanisms that can lead to cell death.

Figure 3.

VG16KRKP-mediated interference of the DNA-related processes in C. neoformans. (A) Confocal images of C. neoformans H4-mCherry incubated either without peptide (i) or with FITC-tagged VG16KRKP incubated for 8 h (ii, iii, iv) with ii showing the image through FITC channel; iii showing the image through mCherry channel; i, and iv showing the FITC/mCherry superimposed/merged images. ii, iii, and iv show the peptide to be membrane bound as well as localized in the nucleus with an observable enlargement of the nucleus in few cases, marked by the arrow, depicting nuclear fragmentation. (B) Plot of fluorescence intensity of ribo-green bound to RNA versus VG16KRKP concentration showing complete transcriptional inhibition in vitro, at 40 μM concentration. (C) Flow cytometry analysis showing the effect of peptide on the nuclear mass in C. neoformans. As shown, before treatment (left panel), cells are present in both interphase (G1 peak) and mitotic phase (G2/M peak). Peptide untreated cells also show the similar profile (central panel) while peptide treated cells (right panel) show a reduction in mitotic cell population and an emergence of dead cell peak (Sub G1). The cell populations from the same experiment were quantified and are shown in the table. To see this figure in color, go online.

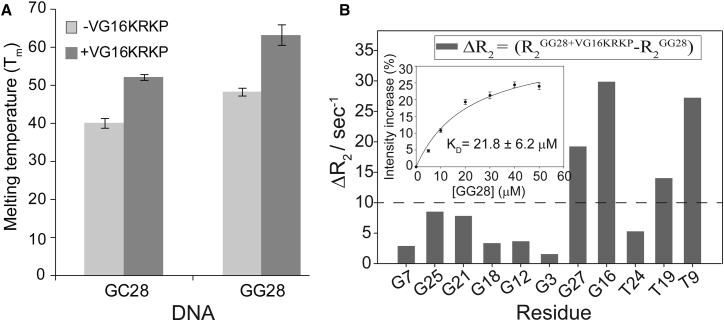

VG16KRKP is capable of binding to DNA, leading to its stabilization in vitro

Because we saw peptide localization in the nuclear region of the cells, we also tested its direct DNA binding properties. Thermal melting studies of DNA were carried out using CD spectroscopy in the absence and presence of VG16KRKP to understand the direct interaction of peptide and DNA. Interestingly, both DNA sequences, GC-rich GG28 and AT-rich GC28 (Fig. S3 A), represented an intrinsic CD pattern for native B type DNA duplex (38, 46) both in the absence and presence of VG16KRKP (Fig. S3 B). However, melting temperatures (Tm) of control DNA sequences, GG28 and GC28 in the absence of VG16KRKP, were 52.2°C and 40.1°C, respectively (Fig. 4 A), and they increased to 63.2 and 48.4°C in the presence of VG16KRKP (Fig. 4 A), ∼10°C and 8°C higher, respectively. This motivated us to calculate the thermodynamical parameters from CD melting data using van’t Hoff isotherm equation. Interestingly, the ΔΔH (ΔHGG28-VG16KRKP-ΔHGG28) and ΔΔS (ΔSGG28-VG16KRKP-ΔSGG28) values for the GG28-VG16KRKP complex increased to –17.35 kcal.mol−1 and –50.75 cal.mol−1.K−1, respectively. Additionally, the overall Gibbs free energy change (ΔG = –11.30 kcal.mol−1) favored complex formation thermodynamically. Similar results were also obtained for GC28-VG16KRKP binding (data not shown), suggesting the peptide did not show much preferential binding to any specific DNA sequence.

Figure 4.

DNA binding abilities of VG16KRKP in vitro. (A) Bar plot of the melting temperatures (Tm) of the two DNA sequences in the absence and in the presence of VG16KRKP, indicating an increase in Tm values that supports binding. (B) Bar diagrams summarizing differential transverse relaxation rates (ΔR2) for imino protons of GG28 in the presence of VG16KRKP at a 1:1 molar ratio. The dotted line indicates the average change of ΔR2 values for the imino protons. The experiments were performed in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, containing 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM NaCl (pH 7.2) at 25°C using a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz NMR spectrometer. (Inset) Plot of percentage increase in the fluorescence intensity of FITC-tagged VG16KRKP as a function of DNA (GG28) concentration. The dissociation constant (KD) for the binding is ∼22 μM.

The 1H NMR spectra of GG28 showed line broadening (data not shown) as well as reduction in intensity of the imino proton resonances (Fig. S3 C) upon addition of increasing concentrations of VG16KRKP. The DNA binding affinity of VG16KRKP was probed by titrating FITC-tagged VG16KRKP with increasing concentration of duplex DNA (GG28) and the dissociation constant (KD) for the binding process was found to be in the micromolar range (KD = 21.8 ± 6.2 μM) (Fig. 4 B, inset). The stabilization of DNA-peptide complex was further supported by the difference in transverse relaxation rate (ΔR2) profiles for imino protons of GG28 in the absence and presence of VG16KRKP (Fig. 4 B). As evident from Fig. 4 B, the overall R2 values for each of the residues of GG28 increased by a factor of ∼1.4 upon complexation with the peptide. The most prominent increments of R2 values were found for the dG27, dG16, dT19, and dT9 residues. Note that dG27 and dG16 residues are the terminal residues of the duplex, whereas dT9 and dT19 are in the central region of the duplex. Therefore, it can be concluded that due to complexation with VG16KRKP, the overall correlation time increased due to decreased mobility in the system, reflected in the ΔR2 plot. In contrast, the longitudinal relaxation rates (R1) for the similar imino proton residues of GG28 in the absence as well as in the presence of VG16KRKP did not show significant variation, suggesting that motional preferences cannot be determined using this parameter (data not shown).

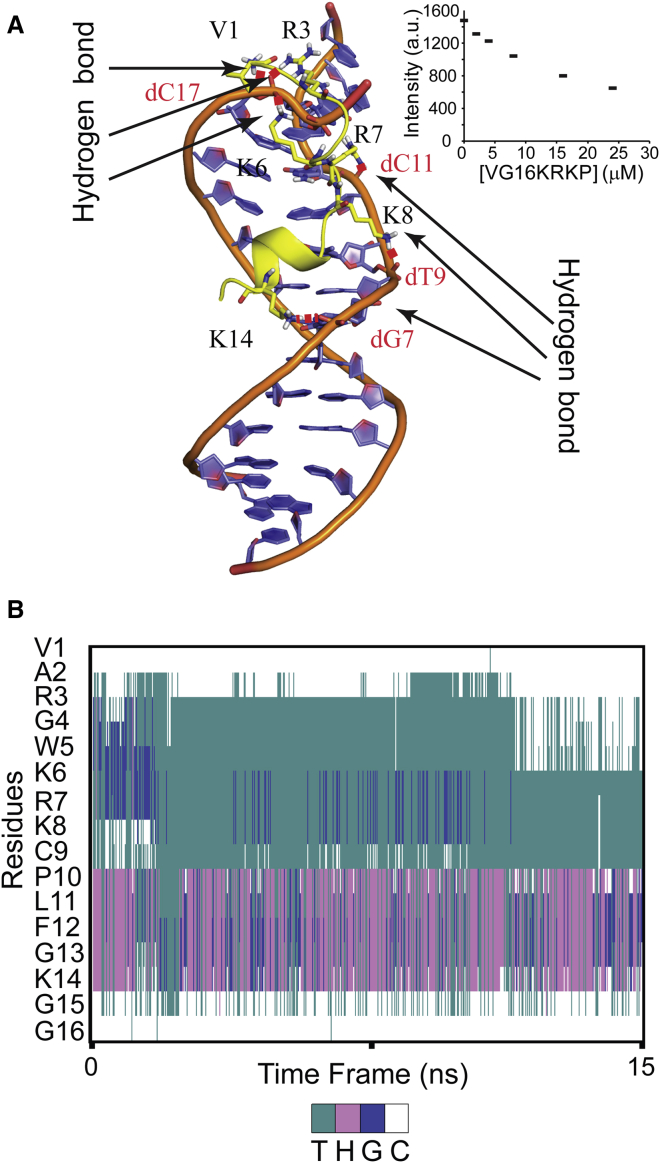

Docking of VG16KRKP into GG28 showed that the peptide binds to the minor groove of GG28 (Fig. 5 A) with three hydrogen bonds, mediated by R3, K6, and R7 of VG16KRKP and backbone phosphate groups of GG28. DAPI fluorescence studies showed a concentration-dependent quenching upon addition of increasing concentrations of peptide to DNA, which confirms the minor groove binding of VG16KRKP (Fig. 5 A, inset). In contrast, there was no contact found between amino acids and imino group of nucleobases, which is in agreement with the experimental R1 results. This correlates well with the fact that the decreased relaxation rate for these nucleobases can be accounted for binding of peptide with DNA, which protects the imino group’s chemical exchange with bulk water. However, MD simulation (Movie S1; Fig. 5 B) of the initial docking structure was further stabilized by two additional hydrogen bonds, formed by V1, K8, and K14 of the peptide and the phosphate groups of GG28 that accounts for a total Coulombic energy contribution (ΔE) of ∼10 kcal.mol−1 (assuming ∼2 kcal.mol−1 for each hydrogen bond (47)). A similar correlation of dynamicity was also observed in the MD simulation studies for VG16KRKP-GG28 (Movie S1), where the positively charged amino acid residues (R3, K6, R7, K8, and K14) were found to make polar contacts with negatively charged phosphate backbone (dG7, dT7, dC11, and dC17) of GG28. A detailed view of conformational deviations can be accounted in Fig. S3 D, showing that VG16KRKP is bound to GG28 at the minor groove. In summary, VG16KRKP is proposed to compact the DNA duplex and thereby inhibit the transcription pathway to kill the cell.

Figure 5.

Insights into interaction of VG16KRKP with DNA and associated structural changes. (A) VG16KRKP binding to duplex DNA, showing the key polar interaction taking place in the minor groove. The residues forming hydrogen bonds with phosphate backbone of DNA is highlighted in the figure. (Inset) Scatter plot presenting a reduction in the emission intensity of DAPI bound to GG28, as a function of increasing peptide concentration indicating minor groove binding of VG16KRKP. (B) Secondary structure information for VG16KRKP bound to the minor groove of DNA, determined from MD simulation. The color code for secondary structure representation (T-turn, H-Helix, G-310 helix, and C-coil). To see this figure in color, go online.

Structure of VG16KRKP when bound to live C. neoformans cells

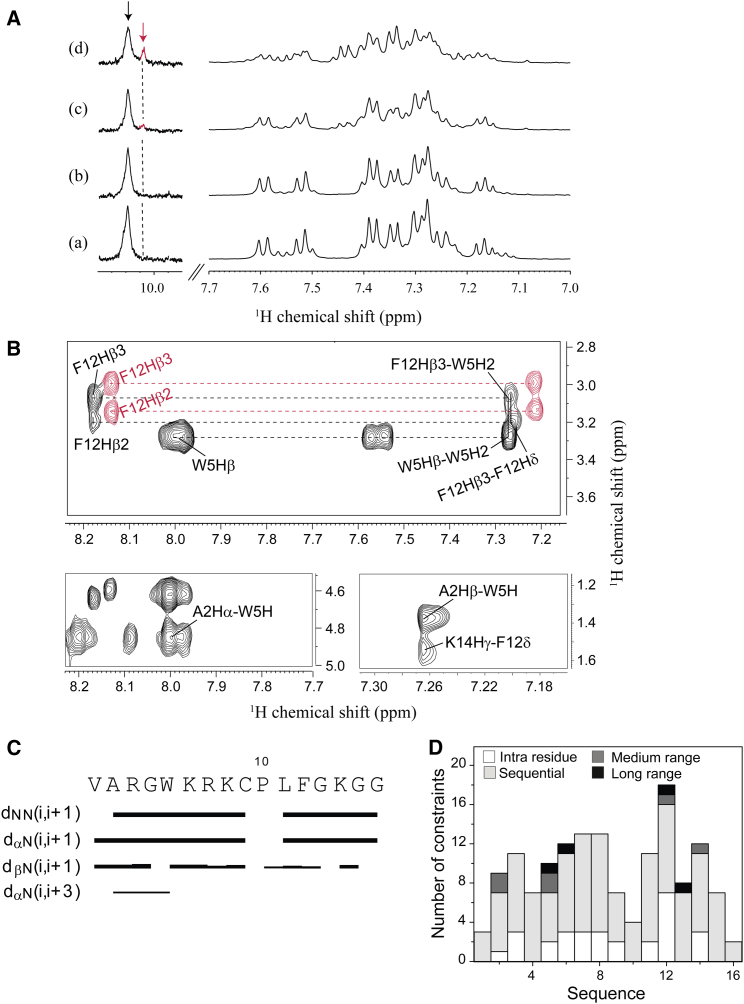

We carried out live-cell NMR experiments to better understand its mechanism of action at atomic resolution. It would also aid in identifying a structural motif, if any, responsible for dictating its biological properties as described in Malgieri et al. (48). One-dimensional titration of VG16KRKP in the presence of increasing numbers of C. neoformans cells showed significant line broadening in all regions of 1H NMR spectrum of the peptide. A gradual reduction in intensity indicated binding of VG16KRKP to the cell surface (Fig. 6 A). Surprisingly, there was also a dramatic change in the aromatic resonances of indole (NεH) ring protons of W5 (resonating at ∼10.2 ppm) (Fig. 6 A d), with an appearance of a small subpeak of Trp indole ring protons, which increased with time, along with a time-dependent decrease in the main peak intensity (Fig. S4 A). This probably corresponds to the emergence of a second conformational species (Fig. 6 A d). The tr-NOESY (23, 49) spectra of VG16KRKP also revealed two conformations of the peptide: conformation 1 shows a single long-range NOE contact between F12CαH and G4NH (Fig. S4 B). In contrast, conformation 2 (Fig. 6 B) shows medium and long-range NOE cross peaks (marked in black) between A2/W5 and between W5/F12 (Figs. 6, B and D, and S4 B) in addition to i to i+1 NOE contacts (Fig. 6, C and D). Both conformations were considered to be loosely bound to the cells, as reflected by the low number of NOEs that are further reduced in case of conformation 1 (Table 1).

Figure 6.

1D and 2D NMR analysis of VG16KRKP interaction with C. neoformans and its structure calculation. (A) 1D proton NMR spectra of VG16KRKP alone (a) and upon titration with increasing concentrations of C. neoformans cells (b–d) showing line broadening of the proton resonances and reduction in intensity indicating binding along with the emergence of a small peak in the Trp indole region (d) indicating the presence of another conformation. (B) Different regions of the tr-NOESY spectra showing the important medium- and long-range NOE connectivities along with presence of two different conformations (red labels indicate conformation 1 and black labels indicate conformation 2). The experiment was performed at 25°C and pH 5.5 using a 700 MHz Bruker Avance III NMR spectrometer, equipped with a cryoprobe. (C) Bar plot showing NOE connectivities of the bound conformation 2 of VG16KRKP with the thickness of the lines corresponding to the number of NOEs; (D) histogram showing the short-, medium-, and long-range NOEs of VG16KRKP conformation 2 when bound to C. neoformans. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

Summary of Structural Statistics for the 20 Lowest Energy Ensemble Structures of VG16KRKP in C. neoformans Cell Suspension

| Distance Restraints | Conformation 1 | Conformation 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Intraresidue (i–j = 0) | 29 | 29 |

| Sequential (|i–j| = 1) | 53 | 54 |

| Medium-range (2 ≤ |i–j| ≤ 4) | 02 | 03 |

| Long-range (|i–j| ≥ 5) | 01 | 02 |

| Total | 85 | 88 |

| Angular restraints | 40 | 40 |

| Ф | 13 | 13 |

| Ψ | 13 | 13 |

| Distance restraints from violations (≥0.4 Å) | 0 | 0 |

| Deviation from mean structure (Å) | ||

| Average back bone to mean structure | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| Average heavy atom to mean structure | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| Ramachandran plot for mean structurea | ||

| % Residues in the most favorable and additionally allowed regions | 100 | 100 |

| % Residues in the generously allowed region | 0 | 0 |

| % Residues in the disallowed region | 0 | 0 |

Based on Procheck NMR.

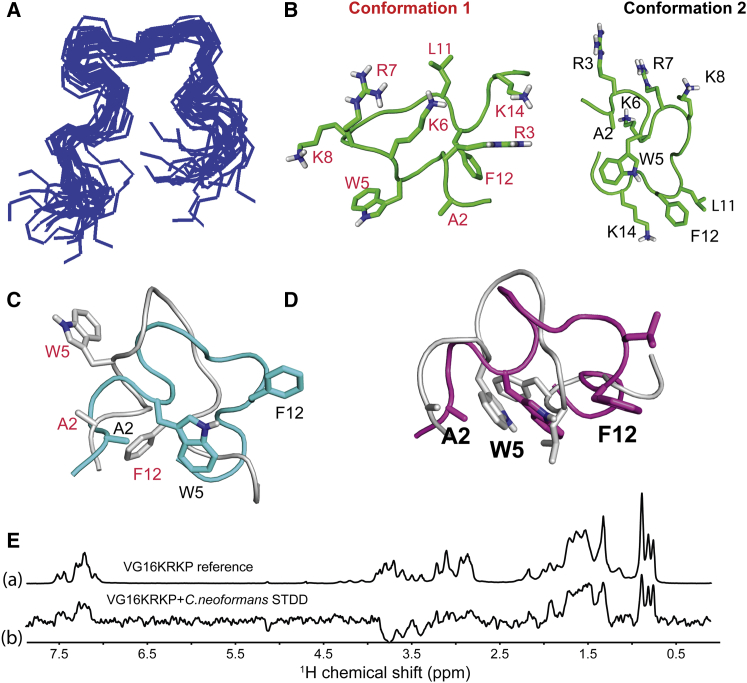

The 20 ensemble structures of conformation 2 of VG16KRKP show a satisfactory superimposition (Fig. 7 A) with a root mean-square deviation (RMSD) value of 1.3 Å (Table 1). The three-dimensional (3D) structure of conformation 2 (Fig. 7 B, right) in live C. neoformans cell shows an amphipathic arrangement with a clear segregation of the polar face composed of all positively charged Arg and Lys residues (R3, K6, R7, and K8) from the hydrophobic face. Interestingly, K14 is seen to be involved in a cation π stabilizing interaction with F12 (Figs. 6 B and 7 B, right). Conformation 1, however, has the L11 residue oriented toward the polar face (Fig. 7 B, left). The overlay of conformations, conformation 1 with conformation 2 of VG16KRKP clearly reflects increased stabilization of conformation 2 contributed by the hydrophobic interaction between W5/F12 (Fig. 7 C). The reduced stability of conformation 1 is also evident from a dispersed ensemble structure (data not shown) with a high RMSD value of 2.4 Å (Table 1), reflecting its dynamic nature.

Figure 7.

Folded conformation of VG16KRKP upon binding to C. neoformans giving insights into its residue-specific contacts. (A) 20 ensemble structures of conformation 2 of VG16KRKP in the presence of C. neoformans showing a fair convergence among the structures. (B) Cartoon representation of a single structure of conformation 1 (left panel) and conformation 2 (right panel) of VG16KRKP bound to C. neoformans labeled in red and black, respectively showing interaction between G4 and F12 for conformation 1 and hydrophobic triad between A2, W5 and F12 in conformation 2. (C) Overlay of the cartoon representations of the single structures of conformation 1 (gray cartoon and labeled in red) and conformation 2 (cyan cartoon and labeled in black) of VG16KRKP bound to C. neoformans showing the differences in the hydrophobic stabilization. (D) Overlay of the cartoon representation of the single structures of VG16KRKP bound to C. neoformans (magenta) and LPS (gray). (E) Probing the residue-specific contacts of VG16KRKP when bound to C. neoformans using STDD. (a) Reference spectra of VG16KRKP alone. (b) STDD spectra of VG16KRKP and C. neoformans showing the binding of VG16KRKP to the C. neoformans cells at an atomic resolution. The experiment was performed at 25°C in 99% D2O phosphate buffer using a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz NMR spectrometer. To see this figure in color, go online.

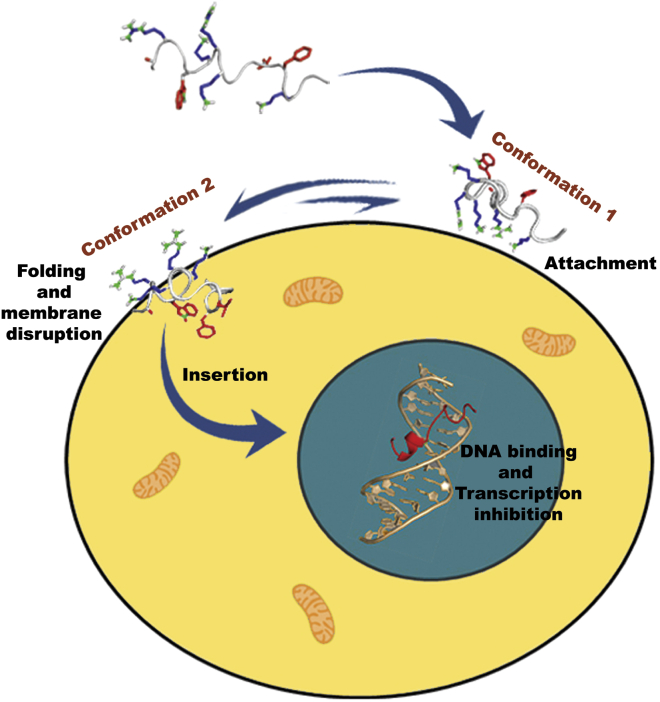

Comparison of the C. neoformans-bound structure of VG16KRKP with the LPS-bound structure shows that the hydrophobic triad composed of W5, L11, and F12 in the LPS-bound conformation is partially lost in the case of C. neoformans-bound conformation, although the interaction between W5 and F12 is still retained (Fig. 7 D). A2, however, still contributes to the hydrophobic interactions as seen in the LPS bound structure (23). Taken together, the hydrophobic hub of VG16KRKP formed in the presence of LPS or C. neoformans cells consisted of A2-W5-L11-F12 or A2-W5-F12, respectively. This data suggests that the peptide has similar structural arrangement in both environments where the hydrophobic interaction between W5 and F12 seems to be the driving force, playing a major role in stabilization of the peptides on the membrane interface. However, a marked difference in the orientation of the L11 side chain in the two environments might have an implication in preferential stabilization of the folded conformation in LPS, thus leading to an increase in membrane disruption abilities, as seen in the case of Gram-negative bacteria (23). A lack of stable hydrophobic triad composed of W5-L11-F12 in live C. neoformans cell indicated that the peptide is less stable in the C. neoformans environment that supports a lower efficiency in mediating membrane disruption, possibly due to the presence of a polysaccharide capsule and cell wall in C. neoformans (50). Therefore, it may be proposed that the observed cell death in C. neoformans occurred due to both membrane permeabilization and an alternate secondary mechanism of killing, involving traversal of the peptide inside the cell through transient membrane damage and subsequent interference and/or inhibition of the DNA related processes by binding to DNA leading to the death of C. neoformans cells (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

A schematic representation of the mode of action of VG16KRKP against C. neoformans. VG16KRKP is thought to initially interact with the cell surface (conformation 1) through electrostatic interaction, followed by structural stabilization (conformation 2) and hence insertion into the membrane via transient membrane damage. It thereby gets access inside the cell and hinders the DNA-related processes eventually leading to cell death. To see this figure in color, go online.

Next, we carried out live cell saturation transfer double difference (STDD) 1H NMR experiments to identify residue-specific interactions of VG16KRKP upon binding to C. neoformans cells (Fig. 7 E). STDD experiments can also help to distinguish between the two conformations (conformations 1 and 2) observed in the presence of live cells (33, 34, 35). A difference of the 1D STD spectra of the peptide VG16KRKP in the presence of live cells (Fig. S4 C a) and the spectra of live cells only (Fig. S4 C b), yielded the STDD spectra of the peptide in the presence of live cells. Surprisingly, the 1D STDD spectra of VG16KRKP in live cell had many similarities with its reference 1H NMR spectra (Fig. 7 E), attributable to close association of the peptide with the cell surface. VG16KRKP alone did not show any STDD signal (data not shown), revealing effective magnetization transfer from cells to VG16KRKP when present together. Severe signal overlap prevented the group epitope mapping of the peptide in the presence of live cells. However, strong STDD effects were observed for the aromatic ring protons of F12 and W5, showing their close proximity to the cell surface (Fig. 7 E). Additionally, the aliphatic region (between 1.3 and 2 ppm), corresponding to the β, γ, and δ-protons of the positively charged R3, R7, K6, K8, and K14, showed intermediate STDD effects, indicating their participation in the binding interaction (Fig. 7 E). The upfield region (0.7–1 ppm), which corresponds to the γ- and δ-protons of V1 and L11, also showed very strong STDD effects. In contrast, a weak STDD effect was obtained for P10, A2, and the β-protons of W5, F11, and C9, resonating between 2.8 and 3.2 ppm. STDD results yet again reveal the importance of the aromatic W5 and F12 residues, and the positively charged Arg and Lys residues in interacting with the cell surface, as observed in the 3D structure of VG16KRKP. In addition, the Val, Leu, Cys, and Pro residues, although not directly involved in the formation of hydrophobic hub of the peptide, possibly play a role in stabilizing the peptide on the cell surface as evident from STDD results. This data corroborated well with the mutational analysis of VG16KRKP using single Ala mutations at Cys (C9A) or Pro (P10A), giving rise to much reduced antimicrobial activity of the mutants compared to the wild-type (unpublished data).

Collectively, we propose that conformation 1 is short lived, representing an intermediate in the interaction process that includes the initial interaction of the peptide with the cell surface. In other words, conformation 1 represents the initial attachment of the peptide to the cell surface, mediated primarily by strong electrostatic interactions between positive residues R3, K6, R7, K8, and K14 of VG16KRKP and the negatively charged phosphate groups of the cell membrane, as indicated by the high RMSD values and dispersed ensemble structure for conformation 1 (Fig. 8). This in turn initiates the binding of the peptide to the cell, where conformation 1 inserts itself into the membrane and adopts conformation 2, a more stable structure. This is also supported by the STDD data, where high STD effects are seen for W5 and F12 with moderate STD effects for L11. These are more probable in conformation 2 than in conformation 1, as seen from the orientation of W5, L11, and F12 in both conformations (Fig. 7 B).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the designed peptide presents itself as an antifungal drug molecule exerting its antifungal activity primarily via cell membrane penetration, possibly causing transient damage on the cell surface leading to efflux of ions and metabolites. This allows entry of the peptide into the cells, where it may have secondary targets such as DNA. It has been reported that antifungal peptides of animal as well as plant origin, such as the cysteine-rich family of AMPs, have intracellular targets and usually enter inside a cell either through receptor-mediated uptake or membrane permeabilization (5). In addition, proline-rich antifungal peptides have also been reported to translocate across the fungal membrane and interact with intracellular targets (51). In another report, a histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptide Buforin II was shown to penetrate cells via a proline hinge, the removal of which abrogates its penetration into the cell. Proline is also known to play a crucial role in inducing peptide structures that enhance the antimicrobial activity of peptides (52). Both cysteine and proline in our peptide are probably involved in mediating an interaction with the cell surface and are thought to play a role in its activity. This mechanism of action is further supported by our live cell STDD experiments and preliminary mutational analysis (C9A and P10A). However, detailed structural analysis based on mutational studies is further required to establish such claims. Altogether, structural analysis of the designed peptide in the context of live C. neoformans cells provides direct evidence for its mode of action and lays the foundation for the design of more potent antifungal drug candidates that can replace the conventional drugs and alleviate this scarcity in the drug pipeline.

Author Contributions

A.B. designed the research; A.D., A.G., V.Y., J.C., D.B., R.K.K., H.I., A.D., E.A., J.M., and A.B. performed the experiments; A.D., A.G., V.Y., D.B., R.K.K., J.M., K.S., A.R., D.K.L., and A.B. analyzed the results; A.D., A.G., V.Y., K.S., J.M., D.K.L., A.R., and A.B. wrote the article; all authors reviewed the article; and A.B. arranged funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

A.B. thanks Dr. Pallob Kundu, Bose Institute, Kolkata for stimulating discussion and Professor Nikhil R. Jana, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Kolkata for zeta-potential facilities. The Central Instrument Facility of Bose Institute is greatly acknowledged. The structures of VG16KRKP bound to C. neoformans cells have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers PDB: 2N9M and PDB: 2N9N.

This research was mainly supported by the Institutional Fund (Plan Project-II to A.B.) and the Government of India (Council of Scientific & Industrial Research and Department of Science and Technology to A.B.) and partly supported by the funds from National Institutes of Health (to A.R.). A.B. also acknowledges Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, for the infrastructure development fund (No. BT/PR3106/INF/22/138/2011) for procuring 700-MHz NMR spectrometer with cryoprobe. A.D., V.Y., A.G., and R.K.K. are grateful to Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, the Government of India, for their senior research fellowships.

Editor: Paulo Almeida.

Footnotes

Aritreyee Datta and Vikas Yadav contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Materials and Methods, four figures, and one movie are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30754-8.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Tortorano A.M., Peman J., Grillot R. Epidemiology of candidaemia in Europe: results of 28-month European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) hospital-based surveillance study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2004;23:317–322. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park B.J., Wannemuehler K.A., Chiller T.M. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–530. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hancock R.E., Scott M.G. The role of antimicrobial peptides in animal defenses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8856–8861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermes A., Guchelaar H.J., Dankert J. Flucytosine: a review of its pharmacology, clinical indications, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and drug interactions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000;46:171–179. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Weerden N.L., Bleackley M.R., Anderson M.A. Properties and mechanisms of action of naturally occurring antifungal peptides. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70:3545–3570. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldorf A.R., Polak A. Mechanisms of action of 5-fluorocytosine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1983;23:79–85. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powderly W.G., Finkelstein D., Bozzette S.A. A randomized trial comparing fluconazole with clotrimazole troches for the prevention of fungal infections in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:700–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503163321102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnarao T.V., Galgiani J.N. Comparison of the in vitro activities of the echinocandin LY303366, the pneumocandin MK-0991, and fluconazole against Candida species and Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1957–1960. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Missall T.A., Lodge J.K. Function of the thioredoxin proteins in Cryptococcus neoformans during stress or virulence and regulation by putative transcriptional modulators. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57:847–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butts A., Krysan D.J. Antifungal drug discovery: something old and something new. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002870. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brogden K.A. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong J.H., Kim J.S., Kim Y. NMR structural studies of antimicrobial peptides: LPcin analogs. Biophys. J. 2016;110:423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon B., Waring A.J., Hong M. A 2H solid-state NMR study of lipid clustering by cationic antimicrobial and cell-penetrating peptides in model bacterial membranes. Biophys. J. 2013;105:2333–2342. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambroggio E.E., Separovic F., Bagatolli L.A. Direct visualization of membrane leakage induced by the antibiotic peptides: maculatin, citropin, and aurein. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1874–1881. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W., O’Brien-Simpson N.M., Wade J.D. Multimerization of a proline-rich antimicrobial peptide, Chex-Arg20, alters its mechanism of interaction with the Escherichia coli Membrane. Chem. Biol. 2015;22:1250–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stach M., Siriwardena T.N., Reymond J.L. Combining topology and sequence design for the discovery of potent antimicrobial peptide dendrimers against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:12827–12831. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee D.K., Bhunia A., Ramamoorthy A. Detergent-type membrane fragmentation by MSI-78, MSI-367, MSI-594, and MSI-843 antimicrobial peptides and inhibition by cholesterol: a solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance study. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1897–1907. doi: 10.1021/bi501418m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng J.T., Hale J.D., Straus S.K. Effect of membrane composition on antimicrobial peptides aurein 2.2 and 2.3 from Australian southern bell frogs. Biophys. J. 2009;96:552–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhunia A., Mohanram H., Bhattacharjya S. Designed β-boomerang antiendotoxic and antimicrobial peptides: structures and activities in lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:21991–22004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh C., Haldar J. Membrane-active small molecules: designs inspired by antimicrobial peptides. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:1606–1624. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J., Chou S., Chen Z. High specific selectivity and membrane-active mechanism of the synthetic centrosymmetric α-helical peptides with Gly-Gly pairs. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15963. doi: 10.1038/srep15963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnusch C.J., Ulm H., Shai Y. Ultrashort peptide bioconjugates are exclusively antifungal agents and synergize with cyclodextrin and amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00468-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Datta A., Ghosh A., Bhunia A. Antimicrobial peptides: insights into membrane permeabilization, lipopolysaccharide fragmentation and application in plant disease control. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11951. doi: 10.1038/srep11951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoque J., Akkapeddi P., Haldar J. Broad spectrum antibacterial and antifungal polymeric paint materials: synthesis, structure-activity relationship, and membrane-active mode of action. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:1804–1815. doi: 10.1021/am507482y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arakha M., Saleem M., Jha S. The effects of interfacial potential on antimicrobial propensity of ZnO nanoparticle. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9578. doi: 10.1038/srep09578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukhopadhyay J., Kapanidis A.N., Ebright R.H. Translocation of σ(70) with RNA polymerase during transcription: fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay for movement relative to DNA. Cell. 2001;106:453–463. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banerjee R., Rudra P., Mukhopadhyay J. Optimization of recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA polymerase expression and purification. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 2014;94:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Victor B.A., Donald C.M., Ignacio T. University Science Books; Sausalito, CA: 2000. Nucleic Acids: Structures, Properties, and Functions. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mergny J.L., Lacroix L. Analysis of thermal melting curves. Oligonucleotides. 2003;13:515–537. doi: 10.1089/154545703322860825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breslauer K.J. Extracting thermodynamic data from equilibrium melting curves for oligonucleotide order-disorder transitions. Methods Mol. Biol. 1994;26:347–372. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59259-513-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marion D., Ikura M., Bax A. Rapid recording of 2D NMR spectra without phase cycling. Application to the study of hydrogen exchange in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 1989;85:393–399. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sklenar V., Piotto M., Saudek V. Gradient-tailored water suppression for 1H-15N HSQC experiments optimized to retain full sensitivity. J. Magn. Reson. A. 1993;102:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caraballo R., Dong H., Ramström O. Direct STD NMR identification of beta-galactosidase inhibitors from a virtual dynamic hemithioacetal system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:589–593. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayer M., Meyer B. Group epitope mapping by saturation transfer difference NMR to identify segments of a ligand in direct contact with a protein receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6108–6117. doi: 10.1021/ja0100120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhunia A., Bhattacharjya S., Chatterjee S. Applications of saturation transfer difference NMR in biological systems. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhunia A., Bhattacharjya S. Mapping residue-specific contacts of polymyxin B with lipopolysaccharide by saturation transfer difference NMR: insights into outer-membrane disruption and endotoxin neutralization. Biopolymers. 2011;96:273–287. doi: 10.1002/bip.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierce B.G., Hourai Y., Weng Z. Accelerating protein docking in ZDOCK using an advanced 3D convolution library. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh A., Kar R.K., Bhunia A. Indolicidin targets duplex DNA: structural and mechanistic insight through a combination of spectroscopy and microscopy. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:2052–2058. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindorff-Larsen K., Piana S., Shaw D.E. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins. 2010;78:1950–1958. doi: 10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hole C.R., Bui H., Wozniak K.L. Mechanisms of dendritic cell lysosomal killing of Cryptococcus. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:739. doi: 10.1038/srep00739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubinstein B., Mahar P. Effects of osmotic shock on some membrane-regulated events of oat coleoptile cells. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:365–368. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrestha S.K., Chang C.W., Takemoto J.Y. Antifungal amphiphilic aminoglycoside K20: bioactivities and mechanism of action. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:671. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phoenix D.A., Dennison S.R., Harris F. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2013. Antimicrobial Peptides. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janbon G., Ormerod K.L., Dietrich F.S. Analysis of the genome and transcriptome of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii reveals complex RNA expression and microevolution leading to virulence attenuation. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghosh A., Kar R.K., Bhunia A. Double GC:GC mismatch in dsDNA enhances local dynamics retaining the DNA footprint: a high-resolution NMR study. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:2059–2064. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeremy B.M., John T.L., Lubert S. W. H. Freeman; New York: 2002. Biochemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malgieri G., Avitabile C., Fattorusso R. Structural basis of a temporin 1b analogue antimicrobial activity against Gram negative bacteria determined by CD and NMR techniques in cellular environment. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015;10:965–969. doi: 10.1021/cb501057d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Z., Krause G., Reif B. Structure and orientation of peptide inhibitors bound to beta-amyloid fibrils. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;354:760–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doering T.L. How sweet it is! Cell wall biogenesis and polysaccharide capsule formation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;63:223–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Conti S., Radicioni G., Vitali A. Structural and functional studies on a proline-rich peptide isolated from swine saliva endowed with antifungal activity towards Cryptococcus neoformans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:1066–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sani M.A., Lee T.H., Separovic F. Proline-15 creates an amphipathic wedge in maculatin 1.1 peptides that drives lipid membrane disruption. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848(10 Pt A):2277–2289. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.