Abstract

The WHO/UNICEF Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative has been shown to increase breastfeeding rates, but uncertainty remains about effective methods to improve breastfeeding in community health services. The aim of this pragmatic cluster quasi‐randomised controlled trial was to assess the effectiveness of implementing the Baby‐friendly Initiative (BFI) in community health services. The primary outcome was exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months in healthy babies. Secondary outcomes were other breastfeeding indicators, mothers' satisfaction with the breastfeeding experience, and perceived pressure to breastfeed. A total of 54 Norwegian municipalities were allocated by alternation to the BFI in community health service intervention or routine care. All mothers with infants of five completed months were invited to participate (n = 3948), and 1051 mothers in the intervention arm and 981 in the comparison arm returned the questionnaire. Analyses were by intention to treat. Women in the intervention group were more likely to breastfeed exclusively compared with those who received routine care: 17.9% vs. 14.1% until 6 months [cluster adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 1.33; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.03, 1.72; P = 0.03], 41.4% vs. 35.8% until 5 months [cluster adjusted OR = 1.39; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.77; P = 0.01], and 72.1% vs. 68.2% for any breastfeeding until 6 months [cluster adjusted OR = 1.24; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.54; P = 0.06]. The intervention had no effect on breastfeeding until 12 months. Maternal breastfeeding experience in the two groups did not differ, neither did perceived breastfeeding pressure from staff in the community health services. In conclusion, the BFI in community health services increased rates of exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months. © 2015 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Keywords: Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative, breastfeeding, primary health care, breastfeeding support, cluster quasi‐randomised controlled trial, evidence based practice

Introduction

Human milk is tailored for infants, and breastfeeding is associated with improved child and maternal health (Ip et al. 2009; Horta and Victora 2013). Enabling women to breastfeed is, therefore, a public health priority (Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services 2007; HM Government 2010; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2011). In Norway, 98% of mothers initiate breastfeeding, 17% breastfeed exclusively until 6 months and 35% continue partial breastfeeding for at least a year (Norwegian Directorate of Health 2014). Although these are high levels compared with most other high‐income countries, they fall short of recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO/UNICEF 2003). The Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT) provided foundational evidence of the effect of the WHO/UNICEF Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) (Kramer et al. 2001).

Today, mothers are discharged from hospital earlier than before; thus, efforts to promote breastfeeding need to focus more on the community level (UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative 1999; Lawrence 2011; Haiek 2012; Macaluso et al. 2013; Hernandez‐Aguilar et al. 2014). While the PROBIT study and most systematic reviews have looked at the combined effect of breastfeeding interventions in hospitals and primary care (Spiby et al. 2009; Beake et al. 2012; Renfrew et al. 2012; Haroon et al. 2013; Skouteris et al. 2014; Sinha et al. 2015), a systematic review by the US Preventive Service Task Force focused on interventions in primary care (Chung et al. 2008). This review found that breastfeeding interventions could be more effective than usual care in increasing breastfeeding rates; however, most findings were not statistically significant. Re‐establishing a breastfeeding culture in high‐income countries is challenging (Hoddinott et al. 2011), and the question on how best to support breastfeeding in community health services remains (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013). Thus, evaluations of structured programmes targeting changes at the organizational service delivery level, such as the Baby‐Friendly Initiative (BFI) in community health services, are called for (Beake et al. 2012). Important aspects of breastfeeding interventions are how they impact on maternal satisfaction with their breastfeeding experience and perceived breastfeeding pressure, but so far, these outcomes have been poorly reported (Renfrew et al. 2012).

One possible downside of population‐wide interventions is that they may widen socio‐economic inequalities in health (Macintyre et al. 2001). In Norway, as in most Western countries, breastfeeding rates are consistently lower in low socio‐economic groups (Kristiansen et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2014). Few studies have examined how an increase in breastfeeding resulting from an intervention benefits different socio‐economic groups (Yang et al. 2014).

The aims of our trial were to assess the effectiveness of the BFI in community health services on exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months. Secondary outcomes were exclusive breastfeeding until 5 months, any breastfeeding until 6 and 12 months, maternal satisfaction with the breastfeeding experience and perceived breastfeeding pressure.

Key messages.

The Baby‐friendly Initiative in community health services increased exclusive breastfeeding until 6‐months.

There was no significant difference in effect size in the different socioeconomic groups.

The majority of mothers were satisfied with their breastfeeding experience and did not feel pressurized to breastfeed.

Considering the limited need of additional resources, the local anchorage, scalability and sustainability, the effectiveness of this structured intervention may be of public health importance.

Participants and methods

Study design and population

We assessed the effects of the BFI in community health services, in a cluster quasi‐randomised controlled trial (Higgins and Green, 2011). We decided to allocate municipalities rather than health centres because all health centres within a municipality are under a shared management, and to minimize contamination between the intervention and comparison groups.

The study was undertaken in 54 municipalities in six Norwegian counties, (Østfold, Vestfold, Nord‐Trøndelag, Hordaland, Telemark, Finnmark), where the BFI in community health services had not yet been introduced. These are predominantly rural or semi‐urban districts. Consent to participate in the trial was given by the managers of the community health services before the group allocation. As described in our protocol, the municipalities were meant to be randomised, but due to a misunderstanding, allocation was by alternation: An adviser from Statistics Norway, neither involved in the intervention nor the data analyses, prepared a list of the 54 municipalities ranked according to the number of births in the previous year. For each consecutive pair of clusters, the first was allocated to the intervention and the second to the comparison group. All mothers with babies of five completed months living in the study area were invited to participate in a postal questionnaire survey, with a follow‐up questionnaire when the child passed 11 months. We identified the mothers through the National Population Register. The questionnaire asked about infant feeding practices, maternal satisfaction with the breastfeeding experience, perceived breastfeeding pressure, socio‐demographic factors and smoking habits. The questionnaires were only offered in Norwegian.

We conducted a pre‐intervention postal questionnaire survey to all mothers with infants of 5 or 11 completed months in the municipalities, from 24 August 2009 to 12 January 2010. The BFI in community health services was initiated in all intervention municipalities in 9 December 2009 and continued until the post‐intervention survey commenced in 7 May 2012. Data‐collection ended 19 August 2013. Those who returned a completed questionnaire were entered into a lottery of ten and five vouchers, approximately valued $130 and $650, respectively. Mothers were included in the data‐analyses if they had given birth to a singleton infant of ≥ 37 gestational weeks and a birth weight of ≥2000 g. The statistician performing the main data‐analysis was not involved in the implementation of the intervention or the allocation process and was masked to the group affiliation.

Intervention

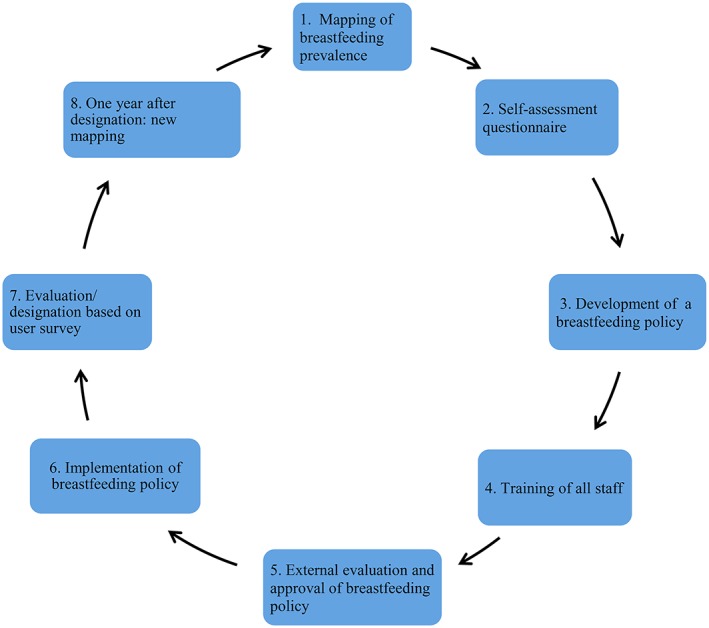

The intervention, developed by the Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Breastfeeding, is an adaptation of the BFHI, for integration into routine antenatal and child care services at the community level (WHO/UNICEF 2003). Municipalities allocated to the intervention group received a manual on how to become Baby‐friendly, outlining 6 points, which collectively describe a quality standard for breastfeeding counselling. The community health services were supervised by two specially trained part‐time public health nurses from the national advisory unit (Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Breastfeeding 2012). We used a cycle approach, i.e. community health services were offered tools for assessment, action and re‐assessment (Fig. 1). In the first stage of the process, public health nurses mapped breastfeeding practices, using a 24‐h recall, and examined the reasons for breastfeeding cessation in 20 infants who attended their 5‐month or 12‐month routine appointments. The second stage was a self‐appraisal questionnaire completed by the staff in order to clarify existing practices. During the third stage, staff were to develop a written breastfeeding policy and a training programme based on the 6‐point quality standard and send these to the national advisory unit for approval. The minimum requirement of training for all staff was 12 h, including reading of a 200 page book with 100 study questions, as well as training and demonstration of practical skills, in line with the WHO/UNICEF 20 h course. About 3 months after approval and implementation of the breastfeeding policy, the Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Breastfeeding would undertake a user survey among pregnant women and mothers of 6‐week old babies. Final designation as a Baby‐friendly community health centre was based on the approval of the breastfeeding policy, as well as at least 80% of pregnant women and mothers confirming that received counselling was in accordance with the 6‐point quality standard. One year after designation, the community health centre mapped the breastfeeding prevalence again, to stimulate a continuous process of assessment and action.

Figure 1.

The Baby‐friendly Initiative in community health services – the process.

The comparison municipalities continued offering routine health services, which comprises both antenatal care and preventive health care from hospital discharge through childhood and adolescence. The routine preventive programme for infants includes a home‐visit between 0–2 weeks, and consultations at 6 weeks, and at 3, 4 5, 6, 7–8, 10 and 11–12 months for vaccination, anthropometric measurements, screening and lactation counselling.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months, specified as exclusive breastfeeding for at least five completed months (World Health Organization 2008). Secondary outcomes were exclusive breastfeeding until 5 months, any breastfeeding until 6 and 12 months and maternal satisfaction with the breastfeeding experience and perceived breastfeeding pressure. The questionnaires were sent to mothers the week after their child was 5 and 11 completed months old. Consistent with the WHO definition (World Health Organization 2008), infants were considered exclusively breastfed if they were given only breast milk. To assess duration of exclusive breastfeeding, we asked both if and for how long they had breastfed, and at what age the infant was introduced to infant formula, water and water based drinks or solids.

We assessed overall maternal satisfaction with the breastfeeding experience by asking the participants ‘How was your overall experience of breastfeeding?’ on a 5 point single‐item scale ranging from very poor to very good (Labarere et al. 2005). We also asked the mothers ‘Have you felt pressured to breastfeed for a longer period than you wanted to?’ We conducted subgroup analyses to explore possible differential effects across socio‐economic groups. Maternal education was used as an indicator for socio‐economic status as it reflects both material resources and knowledge (van Rossem et al. 2009).

Statistical analysis

We anticipated that the intervention would lead to an increase in the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months of 5 percentage points, from approximately 9% based on national figures to 14% (Øverby et al. 2008). Furthermore, we expected to recruit 50 municipalities. Based on these assumptions, and a significance level of 5% for a two‐sided test, statistical power of 80% and an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.01, we estimated a needed sample size of at least 1950 mother–infant pairs (Practihc 2007). As we expected a participation rate of about 55%, we planned to invite 3500 mother–infant pairs to participate.

We used intention to treat analysis as our main analytical approach, i.e. data from all participants were analyzed according to their original allocation to intervention or comparison group. Missing data, ranging from 0% to 2.5% across the different items in the questionnaire, were excluded. No data were discarded. To account for within municipality clustering, the intervention effects on the binary outcome variables were analyzed by mixed‐effects logistic regression. In this model, the effects of municipalities were regarded as random, and the corresponding variance estimate was the basis for the computation of intra‐class correlation (Rodriguez and Elo 2002). The following pre‐defined adjustment variables were included in the model: feeding status at hospital discharge (Haggkvist et al. 2010), maternal education, maternal age, mother with one child or more and smoking habits (Kristiansen et al. 2010). To conduct subgroup analyses according to mothers' education (proxy for socioeconomic status), the interaction between intervention and education was included. To assess the robustness of our findings, we conducted randomisation tests, which make no distributional assumptions. In this analysis, the P‐values of the logistic regression coefficients were computed by re‐randomizing pairs of clusters (Edgington 1995). We also ran a per protocol analysis, based on the 18 of 27 municipalities, which actually completed the intervention, and corresponding comparison clusters of similar size. The questionnaire to assess breastfeeding until 12 months was not sent to mothers who had ended breastfeeding before 6 months, because their answers were considered as known. Non‐response weighting was applied to avoid that this group was overrepresented because of no no‐response. Therefore, to assess the impact on breastfeeding until 12 months, three groups were weighted according to their non‐response: mothers who did not receive the 12 month questionnaire as they had ended breastfeeding before 6 months, non‐responders of 6 month questionnaire and mothers breastfeeding until 6 months (Appendix S2). The estimated regression coefficients were transformed to odds ratios. Statistical analyses were performed with the R programme using the lme4 package and SPSS 21.

Deviations from the protocol

Originally, we planned to estimate intervention effects as the difference between changes in rates of exclusive breastfeeding from the pre‐intervention to the post‐intervention survey, for the intervention and comparison groups (i.e. difference in difference). Instead, we simply compared the post intervention prevalence in the two groups. We made this change for two reasons: (1) We found no important differences between the groups in the pre‐intervention survey (see Results). (2) We conducted the pre‐intervention survey 2–4 years before the post intervention survey, making it likely that the findings were too old to reflect differences between the actual intervention and comparison groups. As described earlier, another deviation from the protocol was that allocation of municipalities was by alternation.

Ethical approval

The Regional Committees for Medical Research Ethics approved the study protocol (REK Sør‐Øst C Ref:S‐09277c 2009/5783), and informed consent was obtained from the mothers. This trial is registered in clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01025362.

Results

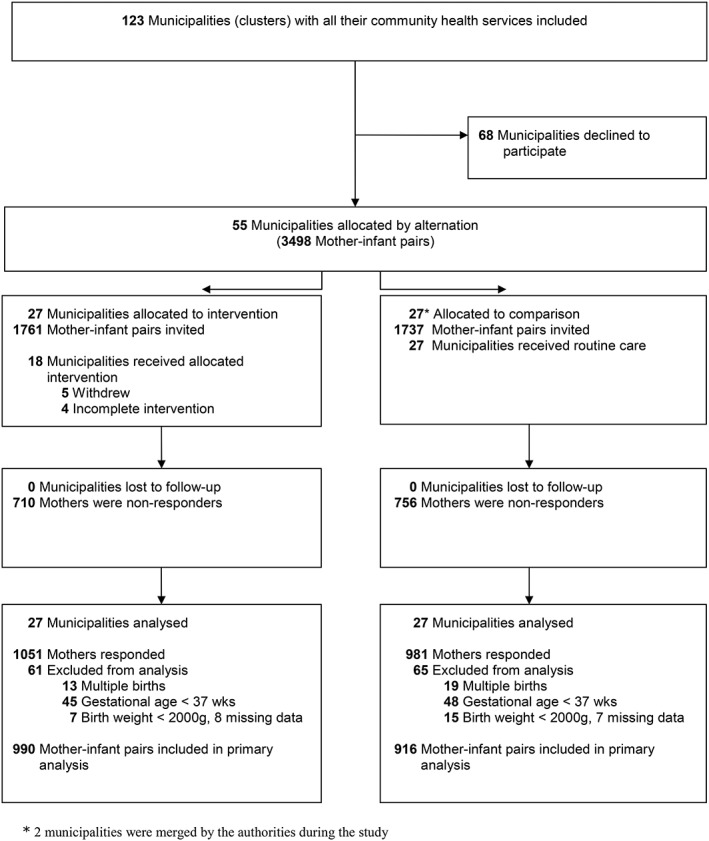

Figure 2 shows the flow of municipalities and mother–infant pairs in the study. All the 123 municipalities in the six counties were invited to participate, and 55 accepted. The main reason for declining was lack of capacity. Twenty seven municipalities were allocated to the intervention group and 28 to the comparison group. During the study period, two municipalities in the comparison arm merged, resulting in a total of 54 clusters. The number of community health centres per municipality ranged from one to seven. For the post‐intervention survey, we invited 3498 mothers with infants of five completed months to participate, and 2032 (58.1%) agreed to take part; 1051/1761 (59.7%) from the intervention group and 981/1737 (56.5%) from the comparison group. One thousand nine hundred and six mother–infant pairs were eligible for data analysis, 990 in the intervention group and 916 in the comparison group.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of municipalities (clusters) and mother‐infant pairs.

Data from the pre‐intervention study showed similar characteristics of mother, infants, levels of breastfeeding and maternal satisfaction at the intervention and comparison sites (Appendix S1). In the post‐intervention study, the two arms were similar in all respects, except that a lower percentage of women in the intervention group were smoking than in the comparison group (10.1% vs. 13.0%, P = 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers and infants in intervention and comparison groups in post‐intervention study (2012–2013)

| Characteristics† | Intervention | Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Number of clusters (municipalities) | 27 | 27* |

| Age of mother, n (%) | ||

| 16–24 years | 156/990 (15.8) | 128/916 (14.0) |

| 25–29 years | 338/990 (34.1) | 311/916 (34.0) |

| 30–34 years | 320/990 (32.3) | 293/916 (32.0) |

| 35–44 years | 176/990 (17.8) | 184/916 (20.0) |

| Education of mother, n (%) | ||

| Primary and secondary school | 92/967 (9.5) | 115/892 (12.9) |

| Comprehensive school | 326/967 (33.7) | 300/892 (33.6) |

| Academy/college/university (≤4 years) | 330/967 (34.1) | 295/892 (33.1) |

| Academy/college/university (>4 years) | 219/967 (22.6) | 182/892 (20.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married | 432/983 (43.9) | 411/904 (45.5) |

| Cohabitant | 517/983 (52.6) | 448/904 (49.6) |

| Not married/cohabitant | 34/983 (3.5) | 45/904 (5.0) |

| Parity, n (%) | ||

| Primiparous | 446/985 (45.3) | 392/910 (43.1) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||

| Smoking 5 months after birth | 100/990 (10.1) | 119/915 (13.0) |

| Feeding status at discharge from hospital, n (%) | ||

| Exclusively breastfed | 761/983 (77.4) | 722/909 (79.4) |

| Infant, n (%) | ||

| Female | 514/990 (51.9) | 440/916 (48.0) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD),g | 3606 (522) | 3606 (493) |

No significant differences in characteristics of intervention and comparison groups (P > 0.05); smoking, P = 0.50.

Two municipalities were merged by the authorities during the study, leaving 27 municipalities in the comparison group.

Excluded: Birth weight < 2000 g, gestational age <37 weeks, multiple births.

At the time of the post‐intervention survey, 18 of the 27 intervention municipalities were designated as Baby‐friendly community health centres, four municipalities were still in the process of becoming designated, and five municipalities had dropped out of the programme.

Table 2 shows our main findings. Women in the intervention group were more likely to breastfeed exclusively than those in the comparison group who received routine care; 17.9% vs. 14.1% until 6 months [cluster adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 1.33; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.02, 1.72; P = 0.03] and 41.4% vs. 35.8% until 5 months [cluster adjusted OR = 1.39; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.77; P = 0.01]. Rates of any breastfeeding until 6 months were 72.1% in the intervention group vs. 68.2% in the comparison group [cluster adjusted OR = 1.24; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.54; P = 0.06]. There was, however, no significant difference in rates of breastfeeding until 12 months, 224 (27.8%) of 807 in the intervention group and 204 (27.9%) of 732 in the comparison group; weighted proportions 30.7% in the intervention group and 32.3% in the comparison group, P = 0.34 (Appendix S2).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary*outcomes

| Intervention group | Comparison group | Crude odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio | P‐value | ICC§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | (95% CI)† | (95% CI)‡ | ||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months | 174/971 (17.9) | 127/900 (14.1) | 1.33 (1.04, 1.70) | 1.33 (1.03, 1.72) | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding until 5 months | 402/971 (41.4) | 322/900 (35.8) | 1.31 (1.06, 1.62) | 1.39 (1.09, 1.77) | 0.01 | 0.018 |

| Any breastfeeding until 6 months | 699/969 (72.1) | 612/898 (68.2) | 1.21 (0.99, 1.48) | 1.24 (0.99, 1.54) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Mother satisfied with breastfeeding experience | 719/944 (76.2) | 660/880 (75.0) | 1.07 (0.86, 1.33) | 1.16 (0.92, 1.46) | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| Perceived pressure to breastfeed (generally) | 139/945 (14.7) | 123/877 (14.0) | 1.05 (0.81, 1.37) | 0.99 (0.76, 1.30) | 0.95 | <0.001 |

| Pressure from staff at child health centre | 54/945 (5.7) | 40/877 (4.6) | 1.26 (0.83, 1.92) | 1.21 (0.79, 1.87) | 0.37 | <0.001 |

Breastfeeding until 12 months in Appendix S2 and Results.

Only adjusted for cluster effects.

Adjusted for cluster effects, breastfeeding at hospital discharge, maternal education, age, parity and smoking habits.

Intra Cluster Correlation

CI, confidence interval

A majority of mothers were satisfied with their breastfeeding experience, and the intervention did not seem to impact on this outcome. Perceived breastfeeding pressure from staff in the community health services was low and did not differ between the two groups (Table 2).

We did not detect statistically significant differences in effect size across socio‐economic subgroups in exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months (P‐value for interaction = 0.163) (Appendix S3).

The per protocol analysis, based on the 18 intervention municipalities, which had completed the intervention and 18 corresponding comparison municipalities, yielded comparable effect estimates to our main analysis, though the effect on exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months was not statistically significant (Appendix S4). Nonparametric randomisation tests yielded similar results as our main analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

In this pragmatic cluster quasi‐randomised controlled trial, the BFI in community health services increased the duration of exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months, compared with routine care. The study was undertaken in a period with a downward trend in breastfeeding rates (Norwegian Directorate of Health 2014). The estimated effect size was moderate. Staff from the comparison municipalities was informed about the ongoing programme; thus, contamination between intervention and comparison groups was likely and may have reduced the effect size. Our findings are largely in agreement with findings from a meta‐analysis of primary care based interventions in developed countries, although most of their findings were not statistically significant (Chung et al. 2008; Sinha et al. 2015) . The PROBIT trial achieved a stronger impact than ours, but the effect of the post‐discharge component of their intervention was not assessed per se (Kramer et al. 2001). In our setting, the Baby‐friendly standard was already part of the routine care in hospitals. Interventions to support breastfeeding are often implemented as adjuncts to routine health services, are time‐intensive or rely on specifically trained nurses or peer counsellors (Labarere et al. 2005). For example, in two recent trials where lactation consultants were integrated into routine primary care, they achieved a threefold to fourfold increase in exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months (from around 3% to 11%) among low‐income women. This indicates a potential for a stronger effect of more intensive, high‐quality support (Renfrew et al. 2012; Bonuck et al. 2014). Our strategy with the BFI in community health services was to strengthen the existing health services, without offering extra resources. Whereas any breastfeeding for 6 months seemed to increase, we were unable to show any significant effect on breastfeeding duration until 12 months. Few other studies have found any effect on breastfeeding duration up to this age (Chung et al. 2008; Renfrew et al. 2012). Factors outside the domain of the health services are probably increasingly important in the second half of infancy.

In line with the findings from most other trials in the community health services, the intervention had no effect on maternal satisfaction with the breastfeeding experience (Labarere et al. 2005). The majority of mothers were satisfied, although only a minority complied with the infant feeding recommendations. This seemingly contradiction may be due to mothers' ability to modify breastfeeding expectations as they acquire experience (Labarere et al. 2005). Our question on overall maternal satisfaction might have been too general, but we also asked specifically about perceived ‘breastfeeding pressure’, which has been debated widely in the media and explored in qualitative studies (Andrews and Knaak 2013). In Norway, breastfeeding is perceived as a social norm, and deviance from the recommended behaviour may cause a feeling of failure. In our study, however, the large majority of mothers did not report being exposed to breastfeeding pressure from health personnel, instead most mothers referred to themselves as the main source of pressure suggesting that they had internalized the societal norm. The focus of our intervention was on improving counselling skills in lactation management, it was not designed as a ‘breast is best’ campaign. This may explain why the perceived pressure to breastfeed did not increase.

Our BFI in community health services did not seem to have differential effects across socio‐economic groups. To our knowledge, the PROBIT study in Belarus is the only previous study that has assessed the effect of a breastfeeding intervention in different socio‐economic groups. Contrary to the situation in Norway, the socio‐economic inequalities in breastfeeding in Belarus were negligible before the intervention started but emerged in the trial's intervention group (Yang et al. 2014). As breastfeeding may increase chances of upward social mobility (Sacker et al. 2013), future trials of interventions to promote breastfeeding should include analysis of effect sizes across socioeconomic groups.

The key strength of this study was that it was a controlled trial and conducted in a real world community health service setting. The cluster‐design reduced the risk that the comparison group would be contaminated by the intervention. However, as staff from the comparison municipalities was informed about the ongoing programme, some elements of the intervention may have influenced practice in comparison centres. The primary outcome, exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months, was assessed prospectively. Breastfeeding practices at earlier ages were assessed with no more than 6 months recall, which has been shown to give valid results (Li et al. 2005). The allocation by alternation was a potential source of bias, but because all municipalities were allocated at the same time using a fixed list, leaving little or no room for manipulation, we believe the risk was negligible (Chalmers 1997). Furthermore, all remained in the trial and provided data for the analysis. The intervention group systematically included the largest municipality from each pair on the ranking list, which might, perhaps, have skewed the results as breastfeeding rates are generally higher in urban areas with more than 100,000 inhabitants (Lande et al. 2003). None of the included municipalities were that large. The pre‐intervention survey found similar characteristics of mother‐infant pairs in the intervention and comparison groups. The breastfeeding rates were non‐significantly lower in the intervention municipalities (Appendix S1). As in other Norwegian population‐based postal questionnaire surveys, participation rate was low. In general, non‐participation tends to be more pronounced among lower educated people (Howe et al. 2013). The response rate in both study arms were, however, similarly higher in women with high education (data not shown). Women in the intervention group may have been less inclined to respond if they failed to breastfeed until 6 months. If so, this would have biased our results. We think this is unlikely, for the following reasons: This was a low‐keyed intervention primarily aimed at health care providers in the community health service and not a community campaign directly targeting the women. Also, mothers received the questionnaires by post, not from the public health nurse. Finally, only about 5% of mothers reported feeling pressurized by the public health nurse to breastfeed.

The authors of a recent survey from child health centres in the city of Bergen were able to collect data from 85.6% of all infants because of the recent implementation of an electronic medical records system. They reported exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months among 24.7% of women attending BF community health services and 17.0% among those attending non‐designated services (Halvorsen et al. 2015).

One out of three municipalities had not completed the intervention within the timeframe of the study. This could indicate that the intervention is difficult to implement in practice. However, some municipalities continued the process towards designation after the study period, and by November 2015, three out of four municipalities were designated as Baby‐friendly. Contrary to what we would have expected, the protocol analysis yielded a slightly smaller effect estimate for the primary outcome than our main analysis, but not for the secondary breastfeeding outcomes. One possible explanation is that the intervention centres not yet designated Baby‐friendly had partially implemented the intervention. The difference between the main and the per protocol analysis may also simply reflect random variation. By November 2015, 100 of the 428 Norwegian municipalities, serving about 50% of the infant population, were designated as Baby‐friendly community health services.

Conclusion

In this large, pragmatic trial, the BFI adapted for community health services increased exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months. Considering the limited need for additional resources, the local anchorage, scalability and sustainability, the effectiveness of this structured intervention may be of public health importance. Whether our findings could be generalized across countries, will likely depend on how the community health services are organized.

Source of funding

This trial has been financially supported by the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation through EXTRA funds (2013/FOM5639) and the Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Breastfeeding, Oslo University Hospital. The intervention was also supported by the Norwegian Directorate of Health and the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

AB proposed the hypothesis, contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AF was the senior author who proposed the study design, contributed to data analysis and interpretation and to the first draft of the article. ØL analysed the data and contributed with data interpretation and writing of the article. BFL contributed to the writing of the final version of the protocol, contributed with the interpretation of data analysis and writing of the article. ET proposed the hypothesis, contributed with the draft study protocol and with writing of the article. TT contributed with the study design and participated in writing of the article. Statistics Norway was responsible for cluster allocation and data collection. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

We thank the mothers and staff who took part in the trial. We thank Elisabeth Gahr Støre, public health nurse and Elisabeth Tufte, public health nurse, IBCLC, MPH; Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Breastfeeding, who developed the programme, adapted from the BFHI. Together with Ragnhild Alquist, public health nurse, IBCLC, MPH, they also supervised the municipalities. We thank Statistics Norway for data‐collection and analysis. We also thank SINTEF Health and Welfare for contributing with the draft protocol. We are grateful to the Directorate of Health and the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare for supporting the intervention. We thank Hanne Kronborg, PhD, University of Aarhus, Denmark for allowing us to use some of her questions on maternal satisfaction. Finally, we thank the Norwegian Women's Public Health Association for their input to the research application and for forwarding it to the Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation.

Bærug, A. , Langsrud, Ø. , Løland, B. F. , Tufte, E. , Tylleskär, T. , and Fretheim, A. (2016) Effectiveness of Baby‐friendly community health services on exclusive breastfeeding and maternal satisfaction: a pragmatic trial. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12: 428–439. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12273.

References

- Andrews T. & Knaak S. (2013) Medicalized mothering: experiences with breastfeeding in Canada and Norway. Sociological Review 61, 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Beake S., Pellowe C., Dykes F., Schmied V. & Bick D. (2012) A systematic review of structured compared with non‐structured breastfeeding programmes to support the initiation and duration of exclusive and any breastfeeding in acute and primary health care settings. Maternal & Child Nutrition 8, 141–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck K., Stuebe A., Barnett J., Labbok M.H., Fletcher J. & Bernstein P.S. (2014) Effect of primary care intervention on breastfeeding duration and intensity. American Journal of Public Health 104 (Suppl 1), S119–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) Strategies to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases: The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers I. (1997) Assembling comparison groups to assess the effects of health care. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 90, 379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M., Raman G., Trikalinos T., Lau J. & Ip S. (2008) Interventions in primary care to promote breastfeeding: an evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine 149, 565–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgington E. (1995) Randomization Tests. Marcel‐Dekker: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Haggkvist A.P., Brantsaeter A.L., Grjibovski A.M., Helsing E., Meltzer H.M. & Haugen M. (2010) Prevalence of breast‐feeding in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study and health service‐related correlates of cessation of full breast‐feeding. Public Health Nutrition 13, 2076–2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiek L.N. (2012) Compliance with Baby‐Friendly policies and practices in hospitals and community health centers in Quebec. Journal of Human Lactation 28, 343–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen M.K., Langeland E., Almenning G., Haugland S., Irgens L.M., Markestad T. et al. (2015) Breastfeeding surveyed using routine data. Tidsskrift for den Norske Lægeforening 135, 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon S., Das J.K., Salam R.A., Imdad A. & Bhutta Z.A. (2013) Breastfeeding promotion interventions and breastfeeding practices: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 13 (Suppl 3), S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez‐Aguilar M.T., Lasarte‐Velillas J.J., Martin‐Calama J., Flores‐Anton B., Borja‐Herrero C., Garcia‐Franco M., et al. (2014) The Baby‐Friendly Initiative in Spain: a challenging pathway. Journal of Human Lactation 30, 276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J., Green S. (editors). (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (Updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration.

- HM Government (2010) Healthy lives, healthy people: our strategy for public health in England. The Stationary Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P., Seyara R. & Marais D. (2011) Global evidence synthesis and UK idiosyncrasy: why have recent UK trials had no significant effects on breastfeeding rates? Maternal & Child Nutrition 7, 221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta B.L. & Victora C.G. (2013) Long‐Term‐Effects of Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Howe L.D., Tilling K., Galobardes B. & Lawlor D.A. (2013) Loss to follow‐up in cohort studies: bias in estimates of socioeconomic inequalities. Epidemiology 24, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip S., Chung M., Raman G., Trikalinos T.A. & Lau J. (2009) A summary of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's evidence report on breastfeeding in developed countries. Breastfeeding Medicine 4 (Suppl 1), S17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M.S., Chalmers B., Hodnett E.D., Sevkovskaya Z., Dzikovich I., Shapiro S. et al. (2001) Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA 285, 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen A.L., Lande B., Overby N.C. & Andersen L.F. (2010) Factors associated with exclusive breast‐feeding and breast‐feeding in Norway. Public Health Nutrition 13, 2087–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarere J., Gelbert‐Baudino N., Ayral A.S., Duc C., Berchotteau M., Bouchon N. et al. (2005) Efficacy of breastfeeding support provided by trained clinicians during an early, routine, preventive visit: a prospective, randomized, open trial of 226 mother‐infant pairs. Pediatrics 115, e139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande B., Andersen L.F., Baerug A., Trygg K.U., Lund‐Larsen K., Veierod M.B. et al. (2003) Infant feeding practices and associated factors in the first six months of life: the Norwegian infant nutrition survey. Acta Paediatrica 92, 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R.A. (2011) Increasing breastfeeding duration: changing the paradigm. Breastfeeding Medicine 6, 367–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Scanlon K.S. & Serdula M.K. (2005) The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutrition Reviews 63, 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso A., Bettinelli M.E., Chapin E.M., Cordova do Espirito Santo L., Mascheroni R., Murante A.M. et al. (2013) A controlled study on baby‐friendly communities in Italy: methods and baseline data. Breastfeeding Medicine 8, 198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S., Chalmers I., Horton R. & Smith R. (2001) Using evidence to inform health policy: case study. BMJ 322, 222–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Directorate of Health (2014) Breastfeeding and Infant Feeding in Norway 2013. [In Norwegian]. (ed Norwegian Directorate of Health). Oslo. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (2007). Recipe for a healthier diet Norwegian Action Plan on Nutrition 2007–2011. Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services: Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Breastfeeding (2012) Baby‐Friendly Initiative in Community Health Services. The Process Towards Becoming a Designated Baby‐Friendly Community Health Service. Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Breastfeeding: Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Practihc (2007) Practihc (pragmatic randomized controlled trials in HealthCare).

- Renfrew M.J., McCormick F.M., Wade A., Quinn B. & Dowswell T. (2012) Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5 CD001141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez G. & Elo I. (2002) Intra‐class correlation in random‐effects models for binary data. Stata Journal 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sacker A., Kelly Y., Iacovou M., Cable N. & Bartley M. (2013) Breast feeding and intergenerational social mobility: what are the mechanisms? Archives of Disease in Childhood 98, 666–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha B., Chowdhury R., Sankar M.J., Martines J., Taneja S., Mazumder S. et al. (2015) Interventions to Improve Breastfeeding Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Acta Paediatr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skouteris H., Nagle C., Fowler M., Kent B., Sahota P. & Morris H. (2014) Interventions designed to promote exclusive breastfeeding in high‐income countries: a systematic review. Breastfeeding Medicine 9, 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiby H., McCormick F., Wallace L., Renfrew M.J., D'Souza L. & Dyson L. (2009) A systematic review of education and evidence‐based practice interventions with health professionals and breast feeding counsellors on duration of breast feeding. Midwifery 25, 50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011) The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. (eds Department of Health and Human Services & Office of the Surgeon General). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative (1999) The baby friendly initiative in the community: a seven point plan for the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding in community health care settings. UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative: London. [Google Scholar]

- van Rossem L., Oenema A., Steegers E.A., Moll H.A., Jaddoe V.W., Hofman A. et al. (2009) Are starting and continuing breastfeeding related to educational background? The generation R study. Pediatrics 123, e1017–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF (2003) Global Strategy on Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2008) Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices Part I: Definitions (ed. World Health Organization ). : Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Platt R.W., Dahhou M. & Kramer M.S. (2014) Do population‐based interventions widen or narrow socioeconomic inequalities? The case of breastfeeding promotion. International Journal of Epidemiology 43, 1284–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Øverby N.C., Kristiansen A.L., Andersen L.F. & Lande B. (2008) Spedkost 6 months ‐ Norwegian National Dietary Survey among Infants (ed. Norwegian Directorate of Health ). : Oslo. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting info item