Abstract

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) remains a major public health problem and there is an urgent need to maximize the impact of primary prevention using the implantable defibrillator. While implantable defibrillators are of utility for prevention of SCD, current methods of selecting candidates have significant shortcomings. Major advancements have occurred in the field of cardiac imaging, with significant potential to identify novel cardiac substrates for improved prediction. While assessment of the left ventricular ejection fraction remains the current major predictor, it is likely that several novel imaging markers will be incorporated into future risk stratification approaches. The goal of this review is to discuss the current status and future potential of cardiac imaging modalities to enhance risk stratification for SCD.

Keywords: Sudden cardiac death, Cardiac imaging, Risk stratification

Introduction

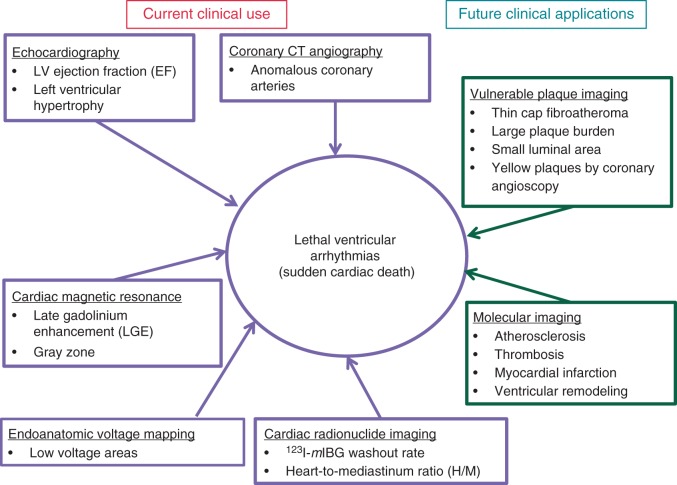

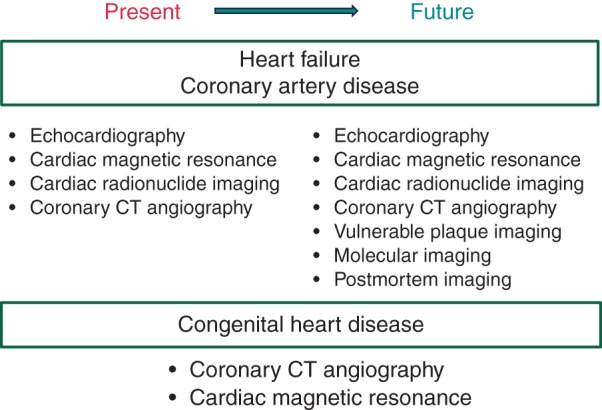

Sudden cardiac death (SCD), defined as a sudden and unexpected pulseless condition of cardiac etiology,1 remains a worldwide public health problem.2 Accurate statistics are not available at the global level, but crude estimates of annual worldwide incidence range from 4 to 5 million.3 In the USA, the annual SCD burden is estimated at 300 000–350 000.4 As the prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) and diabetes increases, especially in developing countries, the burden of SCD is likely to increase worldwide. From a clinical standpoint, measurement of the left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) remains the main risk stratification tool for SCD prediction, but is now recognized to be inadequate.2,5–7 In the vast majority of patients who receive implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), the device may never be utilized for the treatment of spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias.2,5 Primary prevention ICDs continue to be implanted in large numbers of patients based on identification of LVEF <35%,8 but in order to maximize their impact, new tools that will improve risk stratification are necessary.5,9,10 On the other hand, at the community level, almost half of all SCD cases had normal LVEF before SCD.7,11 This emphasizes the need to search for a new diagnostic tool to detect those at risk of SCD other than LVEF.7,11,12 Major advancements have occurred in the field of cardiac imaging, many currently employed in other areas of clinical practice, that could enhance the identification of substrates associated with ventricular arrhythmogenesis. This review will provide an update on the current status of how these imaging modalities may improve SCD risk stratification. The current and future applications of several imaging modalities are shown in Figures 1and 2.

Figure 1.

Framework of current and future imaging modalities for sudden cardiac death risk stratification.

Figure 2.

Current and future imaging modalities for sudden cardiac death risk stratification depending on aetiologies of heart disease. Vulnerable plaque imaging, molecular imaging, and postmortem imaging will be incorporated in future sudden cardiac death risk stratification.

Echocardiography

The left ventricular ejection fraction

Severe LV systolic dysfunction identified by measuring the LVEF is associated with an increased risk of SCD, and landmark randomized clinical trials have guided the use of ICDs for the prevention of SCD in such patients.13,14 The recently published ESC guidelines recommend echocardiography for the assessment of LV function and detection of structural heart disease in all patients with suspected and known ventricular arrhythmia as a class I recommendation.8 However, at the community level, this group comprises a small portion of overall SCD cases.15 In the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study, almost half of all SCD cases (48%) had normal LVEF (>55%), with less than a third having severely reduced LV systolic function.7 Similar findings were reported from a community-based study in Maastricht, the Netherlands. Among 200 cases of SCD with an assessment of LV function prior, 101 (51%) had normal LVEF.11,12 These findings indicate that reduced LVEF is a predictor of SCD in only a subgroup of patients, and that other predictors are necessary. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction is clearly a candidate as a clinical marker of SCD risk, especially since the majority of SCDs in the community (at least half) occur in patients with preserved LV ejection fraction. 7,11,12 At the present time, there is not enough information available to assess the importance of LV diastolic dysfunction in SCD risk assessment. Of note, in contrast with heart failure (HF) with depressed EF, HF with preserved EF was only modestly associated with risk of SCD. In the TOPCAT trial, only 3 patients (out of 1722 patients) in the spironolactone group (0.2%) and 5 patients (out of 1723 patients) in the placebo group (0.3%) experienced aborted cardiac arrest during a mean follow-up of 3.3 years.16

Left ventricular hypertrophy

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is an independent predictor of SCD. The LV myocardium can be dichotomized into its myocyte and interstitial compartments.17 Previous studies have shown that increased and abnormal interstitial remodelling impairs electrical conduction and promotes ventricular arrhythmogenesis.18–22 In the Framingham Heart Study, increased LV mass and hypertrophy, assessed by echocardiogram, were associated with SCD after being adjusted for known risk factors.23 Left ventricular hypertrophy, defined as LV mass (adjusted for height) >143 g/m2 in men and >102 g/m2 in women, was associated with an 116% increase in risk of SCD. Each 50 g/m2 increment in LV mass was associated with a 45% increase in risk of SCD during a mean follow-up of 10.3 years. In a more recent community-based study, consecutive SCD cases (n = 191) were compared with CAD controls (n = 203). This study reported that both reduced LVEF and increased LV mass were independently associated with an increased SCD risk.24 When combined together, reduced LVEF and increased LV mass additively increased the risk of SCD. Another recent study showed that identification of LVH by 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) may convey distinct risk information compared with echocardiographic LVH.25 One hundred and thirty-two sudden cardiac arrest cases were compared with 211 controls. Cases were more likely to have both ECG LVH (12.1 vs. 5.7%) and echocardiographic LVH (35.0 vs. 15.5%). However, there was poor agreement between ECG LVH and echocardiographic LVH (kappa statistic = 0.128), suggesting electrical and anatomical remodelling of the LV. These were retrospective case–control studies and additional prospective studies are likely to be needed to validate these findings. In fact, the role of LV mass as a risk marker was recently validated by a prospective study, which demonstrated that LV mass improved prediction of SCD beyond conventional cardiovascular risk factors in a sample of 905 middle-aged men in Finland.26 The top quartile (LV mass >120 g/m2) was associated with a higher risk of SCD compared with the bottom quartile (<89 g/m2). Further adjustment for LV function only modestly attenuated the risk of SCD among men with LV mass of >120 g/m2. Left ventricular hypertrophy has potential as an adjunct SCD risk stratifier when combined with measurement of the LVEF and can be easily identified via ECG or simultaneously with the LVEF.27

Novel echocardiographic parameters

There are accumulating data that associate LV global longitudinal strain with incidence of SCD/ventricular tachycardia.28,29 Mechanical dispersion measured with speckle tracking echocardiography was associated with sudden death or ventricular arrhythmia in patients with prior myocardial infarction30,31 and in those with lamin A/C mutations.32

Cardiac radionuclide imaging

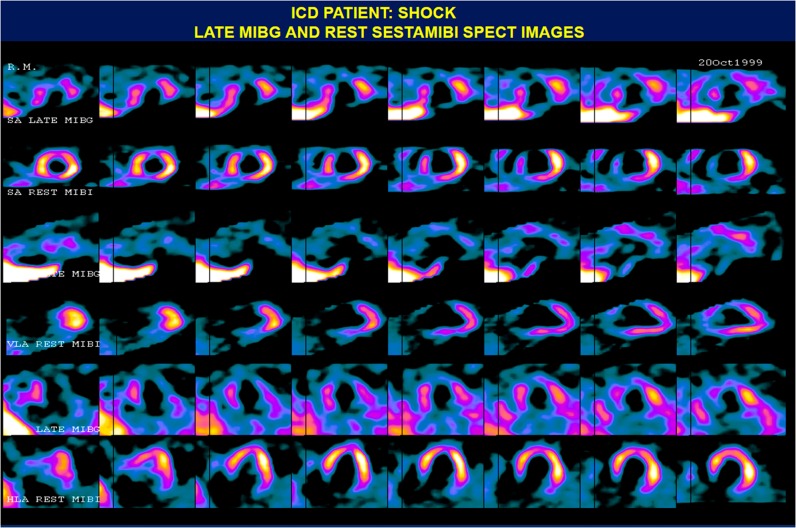

Myocardial abnormalities identified by cardiac radionuclide imaging have been associated with an increased risk of SCD.33–35 The majority of studies have been performed with the tracer Iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (123I-mIBG), a norepinephrine analogue. An example of 123I-mIBG single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in a patient with appropriate ICD discharge is shown in Figure 1. In this study of 17 subjects, those who experienced ICD discharges over time had a significantly lower 123I-mIBG heart-mediastinal tracer uptake ratio and higher 123I-mIBG defect scores compared with patients without ICD discharges.36 In another prospective study of 97 patients, 123I-mIBG washout rate, heart-to-mediastinum (H/M) ratio on the delayed image, and H/M on the early image were associated with SCD in patients with HF and LVEF <40%.35 Tamaki et al.37 reported that an abnormal cardiac 123I-mIBG washout rate was associated with the risk of SCD in 106 patients with HF and EF <40%. ADMIRE-HF, a prospective study with 961 subjects with HF and LVEF ≤35%, reported that H/M <1.60 was associated with an increased risk of the composite endpoint of HF progression, arrhythmic event, and cardiac death.38 There are limited data on the potential role of 123I-mIBG imaging in patients with mildly depressed or preserved LVEF. However, some data are emerging regarding an association between stress myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) and increased risk of SCD in patients with CAD and LVEF >35%.39 Single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging, therefore, may also provide utility as an adjunct SCD risk stratifier for patients with CAD and LVEF >35%. In a single-centre study with 6383 patients, SPECT myocardial perfusion defects were associated with SCD, independent of clinical history and LVEF.40 However, this study failed to show statistically significant net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination improvement,39 suggesting that more work is needed before cardiac radionuclide imaging can be utilized clinically for SCD risk prediction.

Positron emission tomography (PET) has been used for prediction of SCD risk in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy. In the PAREPET (Prediction of Arrhythmic Events with Positron Emission Tomography) study, sympathetic denervation assessed using 11C-metahydroxyephedrine [11C-HED] PET predicts SCD, independently of LVEF and infarct volume.41 Coronary flow reserve evaluated by PET was shown to be associated with major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with both ischaemic and non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy with EF ≤45%.42

Other studies indicate that 123I-mIBG imaging may assist the process of arrhythmia risk stratification in Brugada syndrome and other SCD-associated primary arrhythmia syndromes. A study of 17 patients with Brugada syndrome and 10 age-matched controls demonstrated an abnormal 123I-mIBG uptake in patients with Brugada syndrome.43 In a single patient with LV non-compaction, preserved LV systolic function, and exercise-induced non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, abnormalities were identified in 123I-mIBG washout rate.44 Therefore, there is evidence for significant associations between cardiac radionuclide imaging abnormalities and increased risk of SCD in a variety of cardiac disorders.

Cardiac magnetic resonance

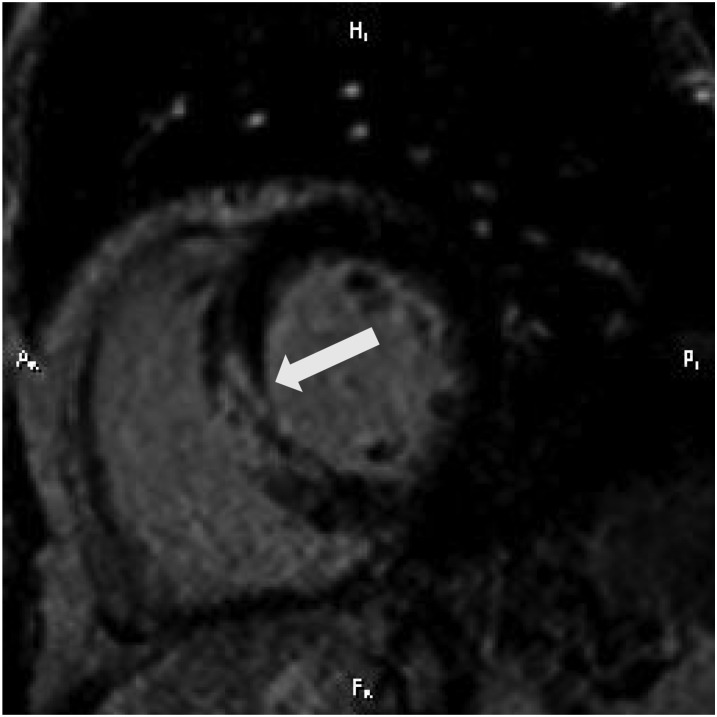

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is capable of providing detailed evaluations of LVEF and cardiac structure.45 Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE)-CMR can provide a comprehensive assessment of myocardial replacement fibrosis.46 However, abnormal myocardial interstitial remodelling is a complex phenomenon, likely related to multiple factors, both genetic and acquired. Late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance is a non-invasive alternative to histological evaluation of the myocardium for identification of areas with replacement fibrosis, and their extent. Tissue heterogeneity assessed by LGE-CMR is associated with higher inducibility of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in ischaemic,47,48 as well as non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy.49 Infarct size determined by LGE was associated with adverse arrhythmic cardiac events, including sudden deaths and ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF) and added prognostic information to LVEF derived by CMR in patients who had non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI).50 Extensive LGE measured by quantitative contrast-enhanced CMR provided additional information for assessing SCD event risk among hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), particularly patients otherwise judged to be at low risk.51 Grey zone, defined as a mixture of scar/fibrosis and viable myocytes in the infarct border zones, has been associated with increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmia.47,48 An example of grey zone in LGE-CMR is shown in Figure 2. In patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy, fibrosis of the mid-wall detected by LGE-CMR was associated with adverse cardiac events (hospitalization for HF, appropriate ICD firing, and cardiac death).52 Mid-wall fibrosis detected by LGE-CMR was also associated with all-cause mortality and SCD in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy.53 Patients with heart failure and myocardial fibrosis demonstrated by LGE-CMR were shown to have a high likelihood of appropriate ICD therapy.54,55 Additionally, no ICD discharges were reported in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy without LGE, suggesting a low risk for malignant ventricular arrhythmia in that subgroup. On the other hand, myocardial scar assessed by LGE-CMR predicted monomorphic VT, but not polymorphic VT/VF, in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy, suggesting that some patients without LGE on CMR remained at risk for potentially life-threatening arrhythmias.56 Several studies have investigated the association between LGE-CMR and endpoints including SCD in patients with HCM.57–60 Late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance has also been shown to have a prognostic value in predicting adverse cardiovascular events among HCM patients.61 A study by Dawson et al.62 showed that fibrosis detected by LGE-CMR was associated with adverse outcomes (cardiac death/arrest, new episodes of sustained VT, or appropriate ICD discharge) in patients with ventricular arrhythmia, and has the potential to improve risk stratification. The LGE technique has been used to detect myocardial infarction and myocardial necrosis at in-plane resolutions approaching 1 mm. An inherent limitation of LGE imaging, however, is the requirement to have a myocardial segment that can be considered as normal, and can be used to null the CMR signal intensity to highlight myocardial infarction and scar. A recent study by Andreu et al.63 suggested that different techniques to analyse the scar tissue could produce different results in terms of arrhythmogenic property of the scar. They showed that 3D delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance sequences improved delineation of conducting channels in patients undergoing VT ablation.

With diffuse interstitial fibrosis, which is often present throughout the LV in conditions such as pressure-overload syndromes, it becomes necessary to measure the T1 relaxation time after administration of an extracellular contrast agent to determine whether the uptake of contrast is diffusely above the normal range. Owing to the continuous clearance of contrast from blood, the myocardial T1 time depends on the delay after contrast administration, in addition to the contrast dosage, and renal function. To circumvent such potentially confounding effects, newer applications of CMR T1 mapping are based on determining the ratio of the change in the myocardial relaxation rate R1 (= 1/T1) between pre-contrast and post-contrast measurements, divided by the corresponding change of the R1 rate in blood. This coefficient, referred to as the partition coefficient for contrast in myocardium, when corrected by the blood haematocrit, provides a direct measure of the myocardial extracellular volume (ECV) fraction.64,65 The ECV parameter can be used as a marker of extracellular matrix expansion. Indeed, the histologically determined myocardial collagen volume fraction, the gold standard for quantification of myocardial fibrosis, and extracellular contrast distribution volume in gadolinium-enhanced CMR are highly associated with postmortem human myocardium samples.66 Several studies have validated the ECV measurement against histological measures of interstitial fibrosis (e.g. collagen volume fraction by picrosirius red staining) in aortic stenosis, HCM,67,68 and hypertensive heart disease.69,70 Refinements of the T1 mapping technique for evaluation of myocardial fibrosis are ongoing,71,72 and may have potential to better predict SCD in the future. Furthermore, T1 mapping could be used for detection of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.73 Cell size may play an important role during remodelling of gap junctions, and assessing both cell size changes and extracellular matrix expansion may be important aspects of arrhythmogenic myocardial remodelling.74 In a cohort of 793 patients without myocardial infarction, ECV expansion in myocardium without LGE predicted mortality75 as well as other composite endpoints (e.g. cardiac transplant or LV assist device implantation). The ECV had an incremental prognostic value after adjustment for age, history of CAD, and EF.

Myocardial ECV fraction can also be assessed by computed tomography (CT), using an iodinated contrast agent.76,77 The ECV measurements obtained by CT are consistent with parallel measurements using CMR. Computed tomography shows a slight (∼3%) bias towards a higher ECV,77 which may be of little practical concern. An important advantage of contrast-enhanced cardiac CT is the ability to scan patients with virtually any type of implanted device, such as pacemakers and ICDs. Despite significant advances in the development of safety protocols for conventional devices and the development of MR-conditional systems, many implantable devices (most pacemakers and ICDs) continue to represent exclusion criteria for CMR, a limitation that becomes most relevant in much-needed investigations evaluating prediction of recurrent ventricular arrhythmias in patients with primary prevention ICDs. The 2015 ESC guidelines recommend CMR in patients with ventricular arrhythmia when echocardiography does not provide accurate assessment of LV and RV function and/or evaluation of structural changes.8

Coronary computed tomography angiography

Coronary CT angiography has been shown to non-invasively identify anomalous coronary arteries with accuracy. In a study by Datta et al.,78 17 patients were referred for equivocal findings at cardiac catheterization or echocardiography, and in all subjects, the origins of the coronary arteries and their course in relation to the great vessels were successfully demonstrated by multidetector CT. Multidetector CT is currently held as a reference standard for evaluating anomalous coronary arteries.79 Computed tomography received a class IIa recommendation in the most recent ESC guidelines.8

Electroanatomical voltage mapping

Electroanatomical voltage mapping has been used in electrophysiological studies and shown to be useful in some particular situations such as arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C). Low-voltage areas, defined by a bipolar electrogram amplitude of <0.5 mV, were correlated with myocardial loss and fibrofatty replacement at endomyocardial biopsy.80 A normal bipolar endocardial voltage mapping characterized a low-risk subgroup of ARVD/C patients.81

Vulnerable plaque imaging

The vulnerable plaque refers to a plaque that is susceptible to ‘rupture’ and subsequent acute myocardial infarction.82 Virmani et al.83 showed that the thin cap fibroatheromas (TCFAs) are most frequently observed in patients whose deaths were associated with acute MI. While many plaque ruptures could lead to an acute coronary event, only a proportion of these are going to be associated with SCD. Therefore, the ultimate goal of imaging ‘vulnerable plaques’ would be to identify the coronary plaque that is vulnerable to ventricular arrhythmogenesis. However, there are fundamental challenges involved in designing feasible studies that will appropriately address this question. Even though the overall burden of SCD remains high, annual incidence is in the range of 60/100 000, which makes a cohort study even as large as 10 000 subjects unfeasible over any reasonable length of time. Therefore, studies of vulnerable plaque imaging to identify predictors of SCD may be more feasible in high-risk subsets of patients, for example those with known (and potentially) unstable CAD. Recently, the PROSPECT (Providing Regional Observations to Study Predictors of Events in the Coronary Tree) study showed that coronary lesions that led to major adverse cardiovascular events were characterized by TCFAs, large plaque burden, small luminal area, or a combination of these characteristics determined by radiofrequency intravascular ultrasonography.84 There are several imaging methodologies that can evaluate plaque characteristics invasively and non-invasively, that are worth exploring.85

Intracoronary imaging using the intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) methodology has been widely utilized to examine vessel size, plaque burden, and morphology.86 Radiofrequency analysis of the ultrasonographic signal (RF-IVUS) enables further characterization of plaque components based on tissue characteristics such as density, compressibility, concentration of various components, and size.87 Coronary angioscopy is another technique that can provide information regarding the luminal surface of plaque.88 Yellow plaques identified by coronary angioscopy were shown to be associated with an increased risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).89 Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), a catheter-based technique, is able to detect lipid core plaque (LCP)90 and LCPs detected by NIRS were associated with a high risk of peri-procedural MI.91 Optical coherence tomography (OCT) uses near-infrared light to generate cross-sectional blood vessel images.92 Optical coherence tomography can characterize plaque morphologies in vivo.93 A newer-generation OCT, known as frequency domain OCT, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in April 2010. These vulnerable plaque imaging modalities have potential for predicting risk of SCD associated with occurrence of MI.

There are several non-invasive imaging modalities that can characterize plaque morphology. Using computed tomography angiography, positive vessel remodelling and low-attenuation plaques are characteristics associated with culprit lesions in ACS, and these features predict a higher risk of ACS over time.94 Magnetic resonance imaging is used to characterize carotid atherosclerosis such as fibrous cap and lipid-rich necrotic core.95

Molecular imaging

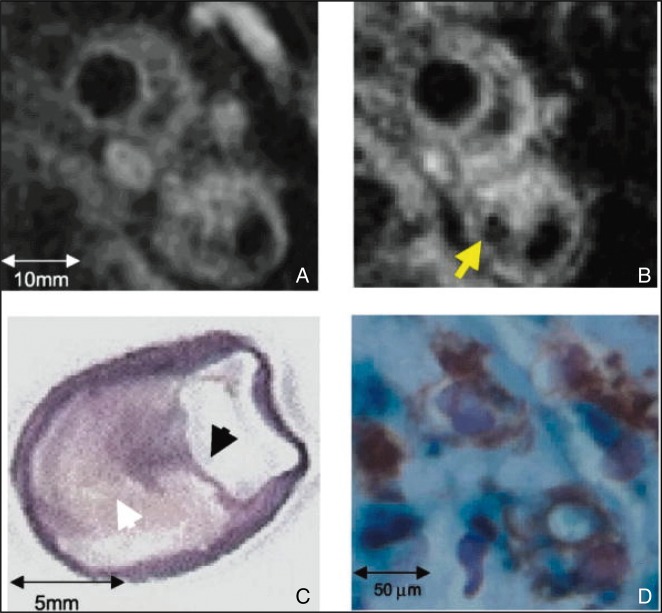

Molecular imaging refers to non-invasive visualization and measurement of biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels.96 This technique can provide valuable insights regarding biological mechanisms of diseases and is increasingly used in cardiovascular conditions.97–99 An example of molecular imaging is shown in Figure 3. Molecular imaging may detect early changes at the molecular level that may not otherwise be detectable by other modalities. Targets for molecular imaging include atherosclerosis, thrombosis, myocardial infarction, ventricular remodelling, and heart failure. With the potential to convert invasive diagnostic procedures to non-invasive studies, molecular imaging holds promise as a tool for enhancing SCD risk stratification.97 For example, cardiac biopsy is the gold standard for evaluation of myocardial fibrosis. However, gadolinium-enhanced CMR represents a non-invasive alternative to histological evaluation.66 While there is no available molecular imaging tool at the present time that could be directly utilized for SCD risk prediction, given the close relationship between SCD and atherosclerosis, and the fact that molecular imaging can detect early changes at the molecular and cellular levels, such tools are likely to be developed in the very near future. There are two components of molecular imaging that continue to witness rapid development: imaging agents and imaging modalities (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

123I-mIBG and 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT images of a patient who received ICD shocks. There are neuronal/perfusion mismatching defects involving the inferior, inferolateral, and apical walls; there is a matched defect in the anterior wall. HLA, horizontal long axis; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; mIBG, metaiodobenzylguanidine (123I-mIBG); MIBI, 99mTc-sestamibi; SA, short axis; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography. Reprinted from Ji and Travin.100

Figure 4.

A short-axis view of cardiac MR in a 50-year-old male with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction from thrombotic occlusion of a septal perforator. There is a very heterogeneous infarct (arrow). Grey zone, defined as a mixture of scar/fibrosis and viable myocytes in the infarct border zones, is associated with increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmia. MR, magnetic resonance.

Figure 5.

Non-invasive CMR of carotid plaque macrophages using dextran-coated iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs). (A) Preinjection CMR (axial 3-mm section) of a patient 4.5 months after presentation with amaurosis fugax. (B) Thirty-six hours after agent injection, focal signal loss evolves within the plaque (arrow). (C) After endarterectomy, a collagen van Gieson stain depicts a thin fibrous cap (black arrowhead) overlying a large lipid core (white arrowhead; ×1.5 magnification). (D) Perls stain for iron and an immunohistochemical stain for macrophages confirm colocalization of MNPs (blue) with macrophages (brown; ×40 magnification). Reproduced from Trivedi et al.107 (Copyright 2004). CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance.

Imaging agents

In general, agents for molecular imaging need two components: signal detection compounds and affinity ligands. In other words, modalities such as CMR need to be able to detect the agent, while binding to the target of interest through affinity ligands with high specificity at the molecular and cellular levels. A list of molecular imaging agents is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Agents used for myocardial molecular imaging

| Agent | Target | Modality |

|---|---|---|

| 123I-mIBG | Sympathetic neurotransmitter radionuclide analogue | SPECT |

| Atherosclerosis | ||

| MNPs (iron oxide) | Cellular inflammation | CMR |

| 18FDG | Glucose transporter-1, hexokinase | PET |

| 99mTc-annexin | Apoptosis/macrophages/intraplaque haemorrhage | SPECT |

| 99mTc-interleukin-2 | Lymphocytes | SPECT |

| Thrombosis | ||

| 99mTc-apcitide | Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor | SPECT |

| EP-2104R | Fibrin | CMR |

| Myocardial infarction | ||

| 99mTc-NC1100692 | Angiogenesis | SPECT |

| MNP, 111indium-oxine | Stem cells | CMR, SPECT |

Modified from Jaffer et al.97

123I-mIBG, iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine; MNPs, magnetic nanoparticles; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; PET, positron emission tomography.

Imaging modalities

A number of molecular imaging modalities are available that are the focus of active and ongoing investigation. These include CMR,99 nuclear imaging (SPECT and PET).101 Integrated nuclear/CT systems (PET/CT and SPECT/CT) are also available,102 and imaging with a combination of PET/CMR also holds promise.103,104

Postmortem imaging in sudden cardiac death

Postmortem imaging is increasingly more common in developed countries. Modalities such as CT angiography and CMR are typically used for this purpose, largely to evaluate the coronary anatomy and myocardium.105 Detailed autopsy with histological evaluation remains the gold standard, but postmortem imaging may lead to discovery of new findings that could be applied to SCD risk stratification while subjects are alive. For example, a study of histologically determined myocardial collagen volume fraction, the gold standard for quantification of myocardial fibrosis, compared with T1 mapping CMR in postmortem human myocardium samples, showed that the latter could be a novel, non-invasive alternative to histological evaluation, for the quantification of both interstitial and replacement myocardial fibrosis.66 While the generalizability of these techniques is currently limited, this is likely to improve based on ongoing use and investigation.

Potential clinical utility of imaging for sudden death risk assessment

We discussed various imaging options including echocardiography, cardiac radionuclide imaging, CMR, and coronary CT angiography. In clinical settings, these options are available and the 2015 ESC guidelines recommend echocardiography (class I, Level B), stress testing CMR or CT (class IIa, Level B) as non-invasive evaluation of patients with suspected or known ventricular arrhythmias.8 Echocardiography is the most commonly used imaging modality due to its inexpensive nature and easy accessibility for cardiologists. On the other hand, there are specific situations where these can be helpful. For example, in patients with structurally normal heart and potentially increased SCD risk, CMR and CT are advised if echocardiography does not provide accurate assessment. In structural heart disease such as ARVD or anomalous origin of coronary arteries, CMR or CT can be of particular value, respectively. In fact, CMR is incorporated into the Task Force Criteria.106 The recent guidelines also recommend stress testing (exercise vs. pharmacological) plus imaging (echocardiography, nuclear perfusion and SPECT) to detect silent ischaemia in patients with ventricular arrhythmias (class I, Level B). The level of evidence on these imaging modalities is ‘B’, meaning that data are derived from a single randomized clinical trial or large non-randomized studies. In summary, while the approach to multimodality imaging for SCD risk stratification has broadened, we are still awaiting prospective clinical trial data that further refine systematic use of imaging for risk assessment.

Conclusions

Sudden cardiac death is a significant public health problem and there is an urgent need to improve current methods of assessing risk with a view to enhancing prevention. Imaging modalities have been the subject of intense and ongoing investigational scrutiny in this regard. Sympathetic innervation, CMR, and molecular imaging techniques are quite promising for this purpose. These novel imaging modalities have the potential to be incorporated into risk stratification approaches for SCD in the future. In particular, there remains a need for more focused and hypothesis-driven evaluation of imaging modalities in subsets of patient populations that are at moderate risk of SCD. As novel imaging modalities continue to emerge, the appropriate prospective clinical studies and risk stratification-based trials to examine utility and cost-effectiveness need to be designed, so that these tools are applied appropriately and efficiently towards non-invasive SCD risk stratification in routine clinical practice, and more efficient use of the ICD.

Funding

This work was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (grants R01HL105170 and R01HL122492 to S.S.C.). S.S.C. holds the Pauline and Harold Price Chair in Cardiac Electrophysiology at the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA. S.N.'s work is also funded by the National Institute of Health (grants K23HL089333 and R01HL116280).

Conflict of interest: S.N. is a scientific advisor to, and a principal investigator for research funding to the Johns Hopkins University from Biosense-Webster, Inc. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

References

- 1. Chugh SS. Early identification of risk factors for sudden cardiac death. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7:318–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fishman GI, Chugh SS, Dimarco JP, Albert CM, Anderson ME, Bonow RO et al. Sudden cardiac death prediction and prevention: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Heart Rhythm Society Workshop. Circulation 2010;122:2335–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chugh SS, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Evanado A, Kehr E, Al Samara M et al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: clinical and research implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2008;51:213–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121:e46–e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldberger JJ, Basu A, Boineau R, Buxton AE, Cain ME, Canty JM Jr. et al. Risk stratification for sudden cardiac death: a plan for the future. Circulation 2014;129:516–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stecker EC, Chugh SS. Prediction of sudden cardiac death: next steps in pursuit of effective methodology. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2011;31:101–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stecker EC, Vickers C, Waltz J, Socoteanu C, John BT, Mariani R et al. Population-based analysis of sudden cardiac death with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: two-year findings from the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Europace 2015;17:1601–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Albert CM, Stevenson WG. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death: too little and too late? Circulation 2013;128:1721–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Narayanan K, Reinier K, Uy-Evanado A, Teodorescu C, Chugh H, Marijon E et al. Frequency and determinants of implantable cardioverter defibrillator deployment among primary prevention candidates with subsequent sudden cardiac arrest in the community. Circulation 2013;128:1733–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Vreede-Swagemakers JJ, Gorgels AP, Dubois-Arbouw WI, van Ree JW, Daemen MJ, Houben LG et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the 1990's: a population-based study in the Maastricht area on incidence, characteristics and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:1500–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gorgels AP, Gijsbers C, de Vreede-Swagemakers J, Lousberg A, Wellens HJ. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest—the relevance of heart failure. The Maastricht Circulatory Arrest Registry. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1204–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Klein H et al. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1933–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1882–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Myerburg RJ, Mitrani R, Interian A Jr, Castellanos A. Interpretation of outcomes of antiarrhythmic clinical trials: design features and population impact. Circulation 1998;97:1514–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moon JC, Messroghli DR, Kellman P, Piechnik SK, Robson MD, Ugander M et al. Myocardial T1 mapping and extracellular volume quantification: a Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) and CMR Working Group of the European Society of Cardiology consensus statement. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013;15:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McLenachan JM, Henderson E, Morris KI, Dargie HJ. Ventricular arrhythmias in patients with hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy. N Engl J Med 1987;317:787–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anderson KP, Walker R, Urie P, Ershler PR, Lux RL, Karwandee SV. Myocardial electrical propagation in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 1993;92:122–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kawara T, Derksen R, de Groot JR, Coronel R, Tasseron S, Linnenbank AC et al. Activation delay after premature stimulation in chronically diseased human myocardium relates to the architecture of interstitial fibrosis. Circulation 2001;104:3069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ, Tasseron S, Vermeulen JT, de Jonge N et al. Fractionated electrograms in dilated cardiomyopathy: origin and relation to abnormal conduction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:1071–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu TJ, Ong JJ, Hwang C, Lee JJ, Fishbein MC, Czer L et al. Characteristics of wave fronts during ventricular fibrillation in human hearts with dilated cardiomyopathy: role of increased fibrosis in the generation of reentry. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haider AW, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are associated with increased risk for sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:1454–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reinier K, Dervan C, Singh T, Uy-Evanado A, Lai S, Gunson K et al. Increased left ventricular mass and decreased left ventricular systolic function have independent pathways to ventricular arrhythmogenesis in coronary artery disease. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:1177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Narayanan K, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Uy-Evanado A, Chugh H, Gunson K et al. Electrocardiographic versus echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and sudden cardiac arrest in the community. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:1040–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laukkanen JA, Khan H, Kurl S, Willeit P, Karppi J, Ronkainen K et al. Left ventricular mass and the risk of sudden cardiac death: a population-based study. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e001285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Russo AM, Stainback RF, Bailey SR, Epstein AE, Heidenreich PA, Jessup M et al. ACCF/HRS/AHA/ASE/HFSA/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2013 appropriate use criteria for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation appropriate use criteria task force, Heart Rhythm Society, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Failure Society of America, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1318–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ng AC, Bertini M, Borleffs CJ, Delgado V, Boersma E, Piers SR et al. Predictors of death and occurrence of appropriate implantable defibrillator therapies in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:1566–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Diller GP, Kempny A, Liodakis E, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Inuzuka R, Uebing A et al. Left ventricular longitudinal function predicts life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia and death in adults with repaired tetralogy of Fallot. Circulation 2012;125:2440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haugaa KH, Grenne BL, Eek CH, Ersboll M, Valeur N, Svendsen JH et al. Strain echocardiography improves risk prediction of ventricular arrhythmias after myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:841–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leong DP, Hoogslag GE, Piers SR, Hoke U, Thijssen J, Marsan NA et al. The relationship between time from myocardial infarction, left ventricular dyssynchrony, and the risk for ventricular arrhythmia: speckle-tracking echocardiographic analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haugaa KH, Hasselberg NE, Edvardsen T. Mechanical dispersion by strain echocardiography: a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias in subjects with lamin A/C mutations. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:104–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kelesidis I, Travin MI. Use of cardiac radionuclide imaging to identify patients at risk for arrhythmic sudden cardiac death. J Nucl Cardiol 2012;19:142–52; quiz 153–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nishisato K, Hashimoto A, Nakata T, Doi T, Yamamoto H, Nagahara D et al. Impaired cardiac sympathetic innervation and myocardial perfusion are related to lethal arrhythmia: quantification of cardiac tracers in patients with ICDs. J Nucl Med 2010;51:1241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kioka H, Yamada T, Mine T, Morita T, Tsukamoto Y, Tamaki S et al. Prediction of sudden death in patients with mild-to-moderate chronic heart failure by using cardiac iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine imaging. Heart 2007;93:1213–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arora R, Ferrick KJ, Nakata T, Kaplan RC, Rozengarten M, Latif F et al. I-123 MIBG imaging and heart rate variability analysis to predict the need for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. J Nucl Cardiol 2003;10:121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tamaki S, Yamada T, Okuyama Y, Morita T, Sanada S, Tsukamoto Y et al. Cardiac iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine imaging predicts sudden cardiac death independently of left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with chronic heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction: results from a comparative study with signal-averaged electrocardiogram, heart rate variability, and QT dispersion. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:426–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jacobson AF, Senior R, Cerqueira MD, Wong ND, Thomas GS, Lopez VA et al. Myocardial iodine-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine imaging and cardiac events in heart failure. Results of the prospective ADMIRE-HF (AdreView Myocardial Imaging for Risk Evaluation in Heart Failure) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2212–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Piccini JP, Starr AZ, Horton JR, Shaw LK, Lee KL, Al-Khatib SM et al. Single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging and the risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with coronary disease and left ventricular ejection fraction >35%. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:206–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Piccini JP, Horton JR, Shaw LK, Al-Khatib SM, Lee KL, Iskandrian AE et al. Single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion defects are associated with an increased risk of all-cause death, cardiovascular death, and sudden cardiac death. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2008;1:180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fallavollita JA, Heavey BM, Luisi AJ Jr, Michalek SM, Baldwa S, Mashtare TL Jr et al. Regional myocardial sympathetic denervation predicts the risk of sudden cardiac arrest in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Majmudar MD, Murthy VL, Shah RV, Kolli S, Mousavi N, Foster CR et al. Quantification of coronary flow reserve in patients with ischaemic and non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy and its association with clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:900–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wichter T, Matheja P, Eckardt L, Kies P, Schafers K, Schulze-Bahr E et al. Cardiac autonomic dysfunction in Brugada syndrome. Circulation 2002;105:702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oliveira SM, Martins E, Oliveira A, Pinho T, Gavina C, Faria T et al. Cardiac 123I-MIBG scintigraphy and arrhythmic risk in left ventricular noncompaction. Rev Port Cardiol 2012;31:247–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Parsai C, O'Hanlon R, Prasad SK, Mohiaddin RH. Diagnostic and prognostic value of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2012;14:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hundley WG, Bluemke DA, Finn JP, Flamm SD, Fogel MA, Friedrich MG et al. ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SCMR 2010 expert consensus document on cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation 2010;121:2462–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schmidt A, Azevedo CF, Cheng A, Gupta SN, Bluemke DA, Foo TK et al. Infarct tissue heterogeneity by magnetic resonance imaging identifies enhanced cardiac arrhythmia susceptibility in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 2007;115:2006–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Roes SD, Borleffs CJ, van der Geest RJ, Westenberg JJ, Marsan NA, Kaandorp TA et al. Infarct tissue heterogeneity assessed with contrast-enhanced MRI predicts spontaneous ventricular arrhythmia in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nazarian S, Bluemke DA, Lardo AC, Zviman MM, Watkins SP, Dickfeld TL et al. Magnetic resonance assessment of the substrate for inducible ventricular tachycardia in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2005;112:2821–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Izquierdo M, Ruiz-Granell R, Bonanad C, Chaustre F, Gomez C, Ferrero A et al. Value of early cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the prediction of adverse arrhythmic cardiac events after a first noncomplicated ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:755–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Pencina MJ, Assenza GE, Haas T et al. Prognostic value of quantitative contrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2014;130:484–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wu KC, Weiss RG, Thiemann DR, Kitagawa K, Schmidt A, Dalal D et al. Late gadolinium enhancement by cardiovascular magnetic resonance heralds an adverse prognosis in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:2414–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gulati A, Jabbour A, Ismail TF, Guha K, Khwaja J, Raza S et al. Association of fibrosis with mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. JAMA 2013;309:896–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Iles L, Pfluger H, Lefkovits L, Butler MJ, Kistler PM, Kaye DM et al. Myocardial fibrosis predicts appropriate device therapy in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:821–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alexandre J, Saloux E, Lebon A, Dugué AE, Lemaitre A, Roule V et al. Scar extent as a predictive factor of ventricular tachycardia cycle length after myocardial infarction: implications for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming optimization. Europace 2014;16:220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Piers SR, Everaerts K, van der Geest RJ, Hazebroek MR, Siebelink HM, Pison LA et al. Myocardial scar predicts monomorphic ventricular tachycardia but not polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:2106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. O'Hanlon R, Grasso A, Roughton M, Moon JC, Clark S, Wage R et al. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:867–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bruder O, Wagner A, Jensen CJ, Schneider S, Ong P, Kispert EM et al. Myocardial scar visualized by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging predicts major adverse events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:875–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Maron MS, Appelbaum E, Harrigan CJ, Buros J, Gibson CM, Hanna C et al. Clinical profile and significance of delayed enhancement in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2008;1:184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rubinshtein R, Glockner JF, Ommen SR, Araoz PA, Ackerman MJ, Sorajja P et al. Characteristics and clinical significance of late gadolinium enhancement by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Green JJ, Berger JS, Kramer CM, Salerno M. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in clinical outcomes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dawson DK, Hawlisch K, Prescott G, Roussin I, Di Pietro E, Deac M et al. Prognostic role of CMR in patients presenting with ventricular arrhythmias. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:335–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Andreu D, Ortiz-Perez JT, Fernandez-Armenta J, Guiu E, Acosta J, Prat-Gonzalez S et al. 3D delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance sequences improve conducting channel delineation prior to ventricular tachycardia ablation. Europace 2015;17:938–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Miller CA, Naish JH, Bishop P, Coutts G, Clark D, Zhao S et al. Comprehensive validation of cardiovascular magnetic resonance techniques for the assessment of myocardial extracellular volume. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. aus dem Siepen F, Buss SJ, Messroghli D, Andre F, Lossnitzer D, Seitz S et al. T1 mapping in dilated cardiomyopathy with cardiac magnetic resonance: quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and comparison with endomyocardial biopsy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kehr E, Sono M, Chugh SS, Jerosch-Herold M. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for detection and quantification of fibrosis in human myocardium in vitro. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2008;24:61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Flett AS, Hayward MP, Ashworth MT, Hansen MS, Taylor AM, Elliott PM et al. Equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the measurement of diffuse myocardial fibrosis: preliminary validation in humans. Circulation 2010;122:138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Flett AS, Sado DM, Quarta G, Mirabel M, Pellerin D, Herrey AS et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis in severe aortic stenosis: an equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;13:819–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Messroghli DR, Nordmeyer S, Dietrich T, Dirsch O, Kaschina E, Savvatis K et al. Assessment of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in rats using small-animal Look-Locker inversion recovery T1 mapping. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:636–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Coelho-Filho OR, Mongeon FP, Mitchell R, Moreno H Jr, Nadruz W Jr, Kwong R et al. Role of transcytolemmal water-exchange in magnetic resonance measurements of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in hypertensive heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:134–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sibley CT, Noureldin RA, Gai N, Nacif MS, Liu S, Turkbey EB et al. T1 mapping in cardiomyopathy at cardiac MR: comparison with endomyocardial biopsy. Radiology 2012;265:724–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kawel N, Nacif M, Zavodni A, Jones J, Liu S, Sibley CT et al. T1 mapping of the myocardium: intra-individual assessment of post-contrast T1 time evolution and extracellular volume fraction at 3T for Gd-DTPA and Gd-BOPTA. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2012;14:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Coelho-Filho OR, Shah RV, Mitchell R, Neilan TG, Moreno H Jr, Simonson B et al. Quantification of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by cardiac magnetic resonance: implications for early cardiac remodeling. Circulation 2013;128:1225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Spach MS, Heidlage JF, Dolber PC, Barr RC. Electrophysiological effects of remodeling cardiac gap junctions and cell size: experimental and model studies of normal cardiac growth. Circ Res 2000;86:302–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wong TC, Piehler K, Meier CG, Testa SM, Klock AM, Aneizi AA et al. Association between extracellular matrix expansion quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and short-term mortality. Circulation 2012;126:1206–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nacif MS, Liu Y, Yao J, Liu S, Sibley CT, Summers RM et al. 3D left ventricular extracellular volume fraction by low-radiation dose cardiac CT: assessment of interstitial myocardial fibrosis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2013;7:51–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nacif MS, Kawel N, Lee JJ, Chen X, Yao J, Zavodni A et al. Interstitial myocardial fibrosis assessed as extracellular volume fraction with low-radiation-dose cardiac CT. Radiology 2012;264:876–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Datta J, White CS, Gilkeson RC, Meyer CA, Kansal S, Jani ML et al. Anomalous coronary arteries in adults: depiction at multi-detector row CT angiography. Radiology 2005;235:812–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Schmitt R, Froehner S, Brunn J, Wagner M, Brunner H, Cherevatyy O et al. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries: imaging with contrast-enhanced, multidetector computed tomography. Eur Radiol 2005;15:1110–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Corrado D, Basso C, Leoni L, Tokajuk B, Bauce B, Frigo G et al. Three-dimensional electroanatomic voltage mapping increases accuracy of diagnosing arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Circulation 2005;111:3042–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Migliore F, Zorzi A, Silvano M, Bevilacqua M, Leoni L, Marra MP et al. Prognostic value of endocardial voltage mapping in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6:167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1989;79:733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:C13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, de Bruyne B, Cristea E, Mintz GS et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011;364:226–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fleg JL, Stone GW, Fayad ZA, Granada JF, Hatsukami TS, Kolodgie FD et al. Detection of high-risk atherosclerotic plaque: report of the NHLBI Working Group on current status and future directions. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:941–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mintz GS, Nissen SE, Anderson WD, Bailey SR, Erbel R, Fitzgerald PJ et al. American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document on Standards for Acquisition, Measurement and Reporting of Intravascular Ultrasound Studies (IVUS). A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:1478–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. DeMaria AN, Narula J, Mahmud E, Tsimikas S. Imaging vulnerable plaque by ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:C32–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ishibashi F, Aziz K, Abela GS, Waxman S. Update on coronary angioscopy: review of a 20-year experience and potential application for detection of vulnerable plaque. J Interv Cardiol 2006;19:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ohtani T, Ueda Y, Mizote I, Oyabu J, Okada K, Hirayama A et al. Number of yellow plaques detected in a coronary artery is associated with future risk of acute coronary syndrome: detection of vulnerable patients by angioscopy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:2194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gardner CM, Tan H, Hull EL, Lisauskas JB, Sum ST, Meese TM et al. Detection of lipid core coronary plaques in autopsy specimens with a novel catheter-based near-infrared spectroscopy system. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2008;1:638–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Goldstein JA, Maini B, Dixon SR, Brilakis ES, Grines CL, Rizik DG et al. Detection of lipid-core plaques by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy identifies high risk of periprocedural myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:429–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. McCabe JM, Croce KJ. Optical coherence tomography. Circulation 2012;126:2140–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Jang IK, Tearney GJ, MacNeill B, Takano M, Moselewski F, Iftima N et al. In vivo characterization of coronary atherosclerotic plaque by use of optical coherence tomography. Circulation 2005;111:1551–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Motoyama S, Sarai M, Harigaya H, Anno H, Inoue K, Hara T et al. Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Cai J, Hatsukami TS, Ferguson MS, Kerwin WS, Saam T, Chu B et al. In vivo quantitative measurement of intact fibrous cap and lipid-rich necrotic core size in atherosclerotic carotid plaque: comparison of high-resolution, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and histology. Circulation 2005;112:3437–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Saraste A, Nekolla SG, Schwaiger M. Cardiovascular molecular imaging: an overview. Cardiovasc Res 2009;83:643–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Jaffer FA, Libby P, Weissleder R. Molecular imaging of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2007;116:1052–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Jaffer FA, Libby P, Weissleder R. Molecular and cellular imaging of atherosclerosis: emerging applications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1328–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Fuster V, Kim RJ. Frontiers in cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation 2005;112:135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Ji SY, Travin MI. Radionuclide imaging of cardiac autonomic innervation. J Nucl Cardiol 2010;17:655–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Phelps ME. PET: the merging of biology and imaging into molecular imaging. J Nucl Med 2000;41:661–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Di Carli MF, Dorbala S, Hachamovitch R. Integrated cardiac PET-CT for the diagnosis and management of CAD. J Nucl Cardiol 2006;13:139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Pichler BJ, Judenhofer MS, Catana C, Walton JH, Kneilling M, Nutt RE et al. Performance test of an LSO-APD detector in a 7-T MRI scanner for simultaneous PET/MRI. J Nucl Med 2006;47:639–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Majmudar MD, Nahrendorf M. Cardiovascular molecular imaging: the road ahead. J Nucl Med 2012;53:673–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Michaud K, Grabherr S, Jackowski C, Bollmann MD, Doenz F, Mangin P. Postmortem imaging of sudden cardiac death. Int J Legal Med 2014;128:127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Eur Heart J 2010;31:806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Trivedi RA, JM UK-I, Graves MJ, Kirkpatrick PJ, Gillard JH. Noninvasive imaging of carotid plaque inflammation. Neurology 2004;63:187–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]