Abstract

Objective

The heightened risk of persons with serious mental illness to contract and transmit HIV is recognized as a public health problem. Persons with HIV and mental illness may be at risk for poor treatment adherence, development of treatment-resistant virus, and worse outcomes. The objective of this study was to test the effectiveness of a community-based advanced practice nurse (APN) intervention (PATH, Preventing AIDS Through Health) to promote adherence to HIV and psychiatric treatment regimens.

Methods

Community-dwelling HIV-positive participants with co-occurring serious mental illnesses (N=238) were recruited from community HIV provider agencies from 2004 to 2008 to participate in the randomized controlled trial. Participants in the intervention group (N=128) were assigned an APN who provided community-based care management at a minimum of one visit per week and coordinated clients’ medical and mental health care for one year. Viral load and CD4 cell count were evaluated at baseline and 12 months.

Results

Longitudinal models for continuous log viral load showed that compared with the control group, the intervention group exhibited a significantly greater reduction in log viral load at 12 months (d=−.361 log 10 copies per milliliter, p<.001). Differences in CD4 counts from baseline to 12 months were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

This project demonstrated the effectiveness of community-based APNs in delivering a tailored intervention to improve outcomes of individuals with HIV and co-occurring serious mental illnesses. Persons with these co-occurring conditions can be successfully treated; with appropriate supportive services, their viral loads can be reduced.

Persons with serious mental illnesses are at increased risk for contracting and transmitting HIV and have poor adherence to medication regimens. Estimates of the prevalence of HIV among persons with mental illnesses vary widely and range from 4% to 23%, compared to .4%–.6% in the general population (1,2). Although already high, such estimates still may be underestimated and signal a hidden epidemic. A number of recent studies have drawn attention to the issue of undetected cases of HIV in inpatient psychiatric populations that are missed even by care providers (3,4).

Early detection and treatment of HIV reduces the risk of its transmission and secondary infections, as well as treatment costs. Yet, the mentally ill population with HIV is one of the most difficult populations to treat because of cognitive dysfunction and poor adherence (5). Effective treatment of persons with HIV and comorbid mental illness is important from an individual clinical perspective as well as from a public health perspective. Persons with co-occurring HIV and mental illness are known to have higher rates of substance abuse and dependence as well as sexual risk behaviors (6). Finally, nonadherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) may pose an additional public health threat because of the increased risk of development of treatment-resistant HIV strains. HAART regimens are extremely complex to manage even among persons without a mental illness (7). Development of interventions for disease management among persons with both HIV infection and a mental illness is therefore a high priority for the health care system.

Treatment programs that offer integrated general health care and mental health care have shown promise for persons with comorbid HIV and mental illnesses (8). The assertive community treatment (ACT) model is one such example that has been used with the mentally ill population. ACT is a multidisciplinary model of care in which services are delivered in the community as opposed to clinics or offices. Advanced practice nurses (APNs) are particularly well suited to lead these programs. APNs have been found to provide care equivalent to or better than care from physicians on some dimensions of HIV care (9). The benefits of adding APNs to community-based treatment programs have been documented in mentally ill (10) and in HIV-positive populations (11–13) but not among HIV-positive persons with mental illnesses.

We designed a study of HIV treatment regimen management carried out by APNs who provided in-home services and coordinated participants’ care. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), an intervention cascade was used to determine the necessary intensity (and expense) of the intervention to realize adherence outcomes. Our hypothesis was that participants in the intervention group would have lower viral loads and subsequent improved immune functioning as indicated by higher CD4 cell counts.

Methods

Study design and sites

This study took place from September 2004 to April 2008 and was a longitudinal RCT with a control and intervention group design. Participants in the intervention group were assigned an APN who provided in-home services and coordinated care with the clients’ other health and mental health service providers over 12 months. Participants assigned to the control group received care as usual, participated in the research interviews, and provided blood samples for testing at the same intervals as those in the intervention group. Participants were recruited from community HIV provider agencies and were deemed eligible for the study if they currently had an active relationship with a case manager and if their treating physician could confirm a co-occurring diagnosis of a serious mental illness. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the trial was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board Committee on Human Subjects, as well by the City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Inclusion criteria for the study were that the participant was 18 or older, could understand spoken English, tested positive for HIV, had a diagnosed serious mental illness (defined as having a disability resulting from mental illness), and was actively involved with mental health services, including case management. There were no exclusion criteria. Advertisements were placed in mental health and HIV treatment facilities, and participants self-identified as being HIV positive and receiving case management for a serious mental illness.

After providing informed consent for participation, all participants received a standard HIV screen at baseline to confirm seropositive status. Receipt of case management with mental health treatment providers was also verified. Any participant who was not currently receiving treatment for HIV was referred to the outpatient clinic at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. All participants were paid $40 for each of four interviews over the 12-month study period, as well as for one 24-month follow-up. A bonus of $100 was paid to participants who provided data at all study time points.

Eligible consenting patient participants were randomly assigned to either the PATH intervention (Preventing AIDS Through Health program) or to the control group to ensure that approximately equal numbers of patients were assigned to each of the two groups, which were balanced with respect to observed and unmeasured baseline factors (14). Research interviews were conducted by trained research assistants who had no contact with the APNs in the study and were not told the assigned treatment of participants, although participants may have disclosed information that revealed assignment to PATH during the interview such as by discussing the APN visits. During the interviews at baseline, three months, six months, and 12 months, the research assistants collected participant behavioral data, including but not limited to the Colorado Symptom Index, 12-item Short Form of the Medical Outcomes Study health survey, alcohol and drug use, HIV knowledge, current medication use, relationship with the case manager, hospitalizations, sexual relationships, and condom use.

Study intervention

The PATH intervention consisted of assignment to an APN, who provided in-home consultations and coordinated medical and mental health services for one year according to a disease management model. The APNs collaborated with multiple prescribing providers, pharmacists, and case managers to organize medication regimens and help participants actively cope with barriers to medication adherence and promote the participant’s self-care abilities. The PATH intervention was developed with the use of a reasoned action model, which holds that health care behavior is driven by intentions to perform a behavior, which is driven in turn by the attitudes regarding the value of performing the behavior, some normative beliefs about the behavior, and self-efficacy regarding one’s ability to carry out that behavior (15,16). The PATH protocol minimally included a face-to-face meeting with the participant at least weekly in which he or she received the basic intervention, which consisted of psychoeducation, pillboxes, and beeping watches. This basic PATH intervention was provided to all participants in the intervention group and was intended to affect behavioral intentions to take medication and follow other treatment recommendations as prescribed. [A detailed manual describing PATH policies is available at www.med.upenn.edu/cmhpsr/links.html?3]

Adherence to treatment was conceptualized broadly, including adherence to HAART if prescribed, adherence to psychotropic medications, and fulfillment of scheduled clinic appointments. Adherence to HIV and psychotropic medications was calculated weekly. Nurses conducted separate pill counts for HIV and psychotropic medications, and these counts were validated by participants’ self-report. If either antiretroviral (ARV) or psychotropic indicators fell below 80%, the APN provided the next cascaded intervention. The intervention cascade was implemented until adherence was maintained equal to or above 80% for three weeks. The cascade represented a gradual increase in intensity and included activation of social networks, followed by use of beepers with alphanumeric displays, then prepaid cellular phones to encourage participants to follow their regimen. The final step in the PATH intervention cascade was directly observed therapy. In addition, the APN coordinated physician appointments for the client and would accompany the client when there was a problem with medication, communication, or other issues needing physician attention. Because treatment was cascaded to individually tailor the PATH intervention on the basis of adherence assessments, adherence rates informed the intervention but were confounded by level of the intervention cascade. Therefore, adherence rates were not used as a trial outcome. Because continuity of care can be crucial for persons with serious mental illness and HIV, we attempted to have the same nurse provide services to specific clients as often as possible.

Outcome measures

Viral load and CD4 counts were measured at baseline and at 12 months. Results of the blood tests at all time points were shared with all participants’ treating physicians.

Data analysis

The primary analyses of intervention effectiveness on biological outcomes were all intent-to-treat analyses. We intended to randomly assign participants to the intervention and control groups by using block randomization. We used block sizes of six, such that for every block of six participants, three would be randomly assigned to the control group, one would receive the intervention from nurse A, one from nurse B, and one from nurse C. This design ensured that each of the three APNs in our study would be equally utilized. However, when a fourth APN entered the study, we failed to change the block size to eight, such that each block would assign four participants to the control group and distribute the other four equally among each of the four APNs. Instead, we continued with block sizes of six, but now for every six participants, two went to the control group and each of the remaining four was paired with an APN. Although still a random sample, this process resulted in a few more participants in PATH than in the control group. To correct for the resulting unequal randomization probabilities and resulting imbalance, all of the analyses were adjusted with weights equal to the inverse of the randomization probabilities. For the log viral load and CD4 results, we present the estimated effects as group differences with confidence intervals and p values, based on the analytic methods described below.

Viral load

Viral load was analyzed with two approaches: first, for the full sample, we dichotomized viral load into detectable versus nondetectable; second, we took data from only the subset of participants who had a detectable viral load at baseline and applied a log 10 transformation to account for the skewed nature of the variable. Nondetectable viral loads were those where less than 75 copies per milliliter were found. For our analysis of detectable versus nondetectable viral load, we implemented a repeated-measures logistic model to examine the effect of condition on the changes in the risk of detectable viral load from baseline to 12 months. This model consisted of main effects for condition and visit (baseline or 12 months) and for the interaction between condition and visit. We took advantage of the interaction term between condition and visit in order to compare the relative odds of a person’s having a detectable viral load between the two groups. We controlled for patient characteristics, including age, race-ethnicity, and psychiatric diagnosis, and tested the model with generalized estimating equations to adjust standard errors in the correlations of detectable viral load between baseline and 12 months.

To test for the significance of changes in log 10 viral load for the subset of participants with a detectable viral loads at baseline, we used a repeated-measures mixed model, with fixed effects of condition (intervention or control group), month (baseline or 12 months), the interaction between condition and month, and the inclusion of a random intercept. The intent-to-treat (ITT) comparison of the randomized groups with respect to change in log 10 viral load was based on testing the significance of the interaction between condition and month. We used SAS version 9.2 Proc Mixed and Proc Genmod computations for these analyses.

CD4 count

We first examined the distribution of CD4 count differences over the 12-month period for the two groups. We then used the same mixed-effects analysis for CD4 as we did for continuous viral load.

Results

Study population

The study screened a total of 330 people, of whom 92 were screened out and not enrolled. Most of the 92 were treated for a mental illness in primary care but did not meet the criteria of having a mental health case manager and receiving ongoing care though a specialty mental health clinic. Several others declined participation during the informed consent process for other reasons, including the intensity of the in-home visits, and one person was excluded who self-identified as being HIV seropositive but whose laboratory results indicated no HIV antibodies in the blood sample. The clinical trial therefore enrolled 238 HIV-seropositive participants with a mental illness, of whom 128 were randomly assigned to the PATH intervention group and 110 to the control group. Study participants were similar in terms of age, gender, race and ethnicity, education level, and employment. The groups were also similar in terms of type of mental illness and number of years since HIV diagnosis. There were no statistically significant differences at baseline between the PATH intervention and control groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with HIV and co-occurring serious mental illness who received or did not receive a nursing intervention

| Intervention (N=128)a |

Control (N=110) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | p |

| Age (M±SD) | 43.9±6.6 | 43.2±7.7 | .421 | ||

| Gender | .984 | ||||

| Male | 67 | 52 | 58 | 53 | |

| Female | 57 | 45 | 49 | 45 | |

| Transgender | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Race | .475 | ||||

| Black or African American | 104 | 81 | 87 | 79 | |

| White | 13 | 10 | 11 | 10 | |

| American Indian | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Other | 8 | 6 | 10 | 9 | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 13 | 10 | 8 | 7 | .583 |

| Education | .688 | ||||

| Less than high school | 66 | 52 | 52 | 47 | |

| High school | 36 | 28 | 38 | 35 | |

| Post–high school training | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Some college | 16 | 13 | 16 | 15 | |

| College degree | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Graduate studies | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Current employment status | .303 | ||||

| Unemployed | 114 | 89 | 97 | 88 | |

| Competitive job | 8 | 6 | 7 | 6 | |

| Transitional employment | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Category of mental illness | .514 | ||||

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorder | 25 | 20 | 28 | 26 | |

| Affective disorder | 94 | 73 | 76 | 69 | |

| Other serious mental illness | 9 | 7 | 6 | 6 | |

| Number of years from HIV diagnosis to baseline interview date (M±SD) |

11.8±5.7 | 12.4±6.5 | .771 | ||

An advanced practice nurse provided community-based care management at a minimum of one visit per week and coordinated patients’ medical and mental health care for one year.

Intervention cascade level and adherence

Of the 128 intervention participants, 105 had complete data on the weekly cascade level they received. We calculated the highest cascade level reached (levels 1 to 5) by each of these participants throughout the 12-month study period and found that 17 participants (16%) reached level 1—the lowest level—as their highest cascade level, 32 (31%) reached level 2, 12 (11%) reached level 3, 15 (14%) reached level 4, and 29 (28%) reached level 5, the highest level. We then looked at the average and median lengths at which these study participants remained at their highest cascade level. We found that the participants in the intervention group remained at their cascade level for an average of 18.5 weeks, with a median duration of 16 weeks.

We found that from baseline to three months, 58% (N=61) of the intervention participants were at least 80% adherent to both psychotropic and ARV medication for every week during the time interval. In comparison, 80% (N=84) of the intervention participants were at least 80% adherent from three months to six months, and 70% (N=74) were adherent from six months to 12 months. We had 20 fewer intervention participants with complete psychotropic and ARV medication adherence data from the first time interval to the last time interval.

HAART outcomes

The PATH intervention group showed improvement in medication usage (Table 2). There were no significant differences in number of participants receiving HAART at baseline. At six months, 74% of intervention participants received HAART, compared with 58% of the control group participants (p=.03). At 12 months, there remained a significantly higher percentage of intervention participants on HAART relative to the control group, and 85% of intervention participants were receiving HAART at 12 months compared with 72% in the control group (p=.05).

Table 2.

Adherence to medication and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for participants with HIV and co-occurring serious mental illness who received or did not receive a nursing intervention

| Intervention (N=105)a |

Control (N=92) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | p |

| Received HAART | |||||

| Baseline | 79 | 75 | 72 | 78 | .57 |

| 3 months | 72 | 68 | 57 | 62 | .52 |

| 6 months | 78 | 74 | 53 | 58 | .03 |

| 12 months | 90 | 85 | 66 | 72 | .05 |

| Change in HAART use over time | |||||

| Started HAART | |||||

| Baseline to 3 months | 11 | 10 | 4 | 4 | |

| 3 months to 6 months | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 6 months to 12 months | 11 | 10 | 7 | 8 | |

| Stopped HAART | |||||

| Baseline to 3 months | 11 | 10 | 12 | 13 | |

| 3 months to 6 months | 8 | 7 | 5 | 5 | |

| 6 months to 12 months | 8 | 7 | 4 | 4 | |

| No change | |||||

| Baseline to 3 months | 79 | 74 | 76 | 83 | |

| 3 months to 6 months | 87 | 81 | 68 | 74 | |

| 6 months to 12 months | 85 | 79 | 71 | 77 | |

An advanced practice nurse provided community-based care management at a minimum of one visit per week and coordinated clients’ medical and mental health care for one year.

Biological outcomes

Table 3 reports the number of participants with a detectable viral load, the median HIV viral load for participants with a detectable viral load, and median CD4 count at each time point and for each study group. Among the 61 PATH intervention participants with a detectable viral load, the median HIV viral load was 9,647 copies per milliliter at baseline and 3,606 copies per milliliter at 12 months. In comparison, the 59 control participants with a detectable viral load at baseline had a median viral load of 7,385 copies per milliliter at baseline and 8,849 at 12 months.

Table 3.

Summary of biological measures at baseline and 12 months for participants with HIV and co-occurring serious mental illness who received or did not receive a nursing intervention

| Intervention (N=128)a | Control (N=110) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % |

| Detectable viral load | ||||

| Baseline | 61 | 48 | 59 | 54 |

| 12 months | 46 | 36 | 47 | 43 |

| Median HIV viral load (copies per milliliter)b |

||||

| Baseline | 9,647 | 7,385 | ||

| 12 months | 3,606 | 8,849 | ||

| Median CD4 absolute count | ||||

| Baseline | 433 | 408 | ||

| 12 months | 507 | 474 | ||

An advanced practice nurse provided community-based care management at a minimum of one visit per week and coordinated clients’ medical and mental health care for one year.

Includes only participants with a detectable viral load (≥75 copies per milliliter)

Viral load

Using the full sample, we first compared the changes in detectable viral load between the control and PATH intervention groups. Under the repeated-measures logistic model for detectable viral load, the control group experienced a nonsignificant reduction in risk of detectable viral load, whereas the intervention group had a 16% decrease in risk (odds ratio=1.16, χ2=7.2, df=1, p=.007). However, the overall intervention (ITT) effect comparing the reduction in detectable viral load between the intervention and control groups was not statistically significant, suggesting that the improvement experienced by the PATH intervention participants may have been due to chance alone.

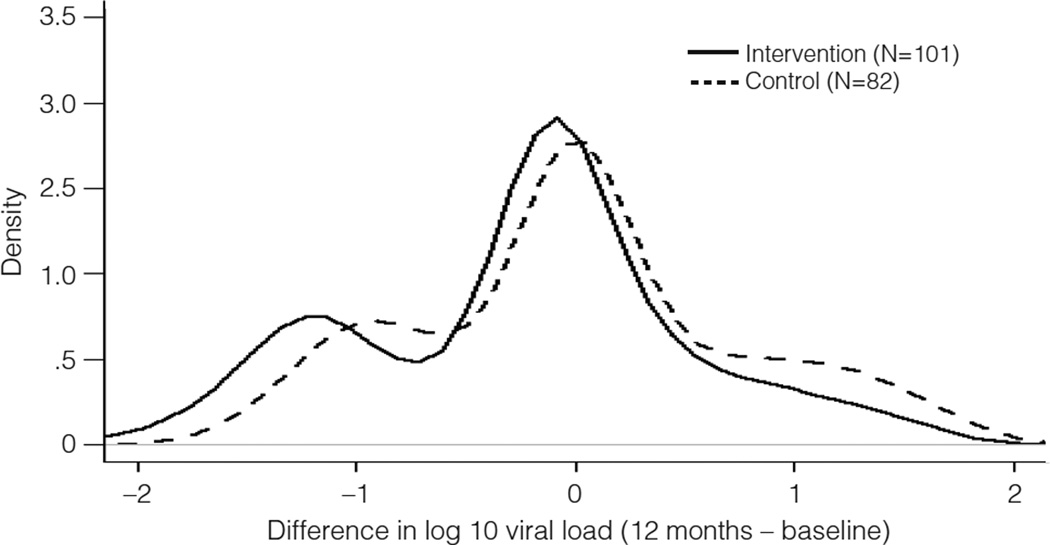

We then used the subset of participants with a detectable viral load at baseline to compare changes in log 10 viral load from baseline to 12 months. Figure 1 shows the change in log 10 viral load from baseline to 12 months for both groups. We had 61 intervention participants (48%) and 59 (54%) control participants who had detectable viral loads at baseline. Using a mixed-effects model for log 10 viral load, we found that the control group did not have a significant change in log 10 viral load from baseline to 12 months. In comparison, the intervention group experienced a significant reduction in log 10 viral load (d=−1.265, t=7.20, df=83, p≤.001), resulting in a net overall intervention (ITT) effect of a decrease in log 10 viral load of .361 (t=1.30, df=83, p<.001). There was no baseline difference in log viral load between the intervention and control arms of the trial.

Figure 1.

Density plot of difference in log 10 viral load for participants with HIV and a serious mental illness who received or did not receive a nursing intervention

CD4 count

CD4 counts for the intervention and control groups were assessed at baseline and 12 months. Results from the mixed-effects model for CD4 count showed no significant improvement in CD4 count for both the PATH intervention and control groups from baseline to 12 months and no significant difference when comparing the two groups.

Discussion

We found that the use of a community-based APN intervention to promote medication and disease management improved viral load outcomes of persons with HIV and a mental illness. The PATH intervention group exhibited greater reductions in mean log viral load but not in risk of detectable viral load from baseline to 12 months as compared with the control group. The PATH intervention group had no difference in CD4 count from baseline to 12 months, however. It is notable that at 12 months, more PATH intervention participants were on HAART than in the control group, which may indicate that clinicians were more willing to prescribe HAART for persons with mental illnesses when they knew that participants were receiving a nurse-led disease management intervention.

Very few studies have used an RCT design to examine the use of regimen management interventions for the HIV population (17), and even fewer have used a nurse-specific intervention and evaluated biological outcomes. Results of these prior studies are inconclusive. For example, Mannheimer and colleagues (18) found that patients assigned to a medication manager—who was often a research nurse—had a higher mean increase in CD4 count by an average of 22.4 at the end of 36 months, which is very consistent with our findings. Viral load differences were not statistically significant in their study. However, Holzemer and colleagues (19) found no significant effect of a nurse intervention on adherence, CD4 count, or viral load over a six-month period. Inconsistencies in intervention content and approach, differences in outcome time points, and the definition of adherence (80% versus 95%) in these and similar studies hinder the contextualization of our findings and reasonable comparison of effect sizes. We note, however, that the intervention tested here is multifaceted and individualized and includes didactic and cognitive components—all of which are characteristics of interventions that have been highly associated with improved adherence and outcomes (20,21).

As health care reform is implemented, an opportunity presents itself to ensure that system changes are made in the provision of care for complex patient populations, such as patients with HIV with co-occurring mental illness. In the current health care system, these persons would most likely be referred to an HIV medical provider in a location separate from their mental health care, requiring patients to be responsible for arranging and keeping their appointments, as well as finding transportation to and from them. This fragmented system does not promote optimal outcomes for this population. The concept of the “medical home” that promotes collaborative care among specialties could be translated into APN-led treatment centers in the community that provide cost-effective and quality care specifically to this population. These findings are supported by another recent report of a collaborative care model using nurses to improve outcomes for patients with poorly managed diabetes or heart disease and depression (22).

We note some limitations to our study. Because we intended this RCT as a phase II clinical trial in proving efficacy of the intervention for a wide variety of persons, we included HIV-positive persons who were not receiving ART. Also, we did not require a history of nonadherence for those who were receiving ART. As a result, 66% were receiving ART, and 40% of the study participants had undetectable viral loads at baseline. This created a ceiling effect for our results. Another consideration to note is that the APNs in this study were university based and had training in research. Therefore, results might be different for community-based nurses. The differences that we observed in viral load were due to changes in a relatively small number of participants who had detectable viral loads at baseline and managed to achieve undetectable viral loads at 12 months. The difference in CD4 counts of the control and intervention groups was not significant at 12 months, and we attribute this result in part to the lagged effect of CD4 count relative to viral load (23,24). In addition, we lacked HAART adherence data in the control group that would have allowed assessment of the extent to which the intervention’s impact on log viral load was due to improvement in HAART adherence relative to adherence in the control group or through another mechanism such as changes in provider willingness to prescribe HAART when additional supports were provided to these patients. The reason that HAART was initiated for more participants in the intervention group during the study may be due in part to physicians’ increased willingness to prescribe HAART when they knew sufficient support services were in place to manage a complex treatment regimen.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that persons with HIV and a mental illness can achieve lower viral load with appropriate supportive services, especially those of an APN. Implementation of community-based nurse disease management for this population and other complex patient populations may save significant health care costs. Consistent with new efforts toward case finding and early initiation of treatment, reductions in viral load in key subgroups of people who may be more likely to transmit the virus from one population to another can help stem this epidemic. We hope our findings inform the redesign of health care delivery to this vulnerable population and slow the spread of HIV.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grant RO1NR008851, awarded to Dr. Blank, principal investigator.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Blank MB, Mandell D, Aiken L, et al. Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:868–873. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg S, Goodman L, Osher F, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness (SMI) American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:31–37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brady KA, Berry S, Gupta R, et al. Seasonal variation in undiagnosed HIV infection on the general medicine and trauma services of two urban hospitals. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:324–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothbard AB, Blank MB, Staab JP, et al. Previously undetected metabolic syndromes and infectious diseases among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:534–537. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao X, Nau DP, Rosenbluth SA, et al. The relationship of disease severity, health beliefs and medication adherence among HIV patients. AIDS Care. 2000;12:387–398. doi: 10.1080/09540120050123783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tennille JA, Solomon P, Fishbein M, et al. Elicitation of cognitions related to HIV risk behaviors in persons with mental illnesses: implications for prevention. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2009;33:360–365. doi: 10.2975/33.1.2009.32.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, et al. Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011. CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parry CD, Blank MB, Pithey AL. Responding to the threat of HIV among persons with mental illness and substance abuse. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20:235–241. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280ebb5f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiken LH, Lake ET, Semaan S, et al. Nurse practitioner managed care for persons with HIV infection. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1993;25:172–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1993.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane CF, Blank MB. NPACT: enhancing programs of assertive community treatment for the seriously mentally ill. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40:549–559. doi: 10.1007/s10597-004-6128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson M, Smereck GAD, Hockman EM, et al. Nurses decrease barriers to health care by “hyperlinking” multiple-diagnosed women living with HIV/AIDS into care. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 1999;10:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holzemer WL, Henry SB, Portillo CJ, et al. The client adherence profiling–intervention tailoring (CAP-IT) intervention for enhancing adherence to HIV/AIDS medications: a pilot study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2000;11:36–44. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3290(06)60420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemppainen JK, Levine RE, Mistal M, et al. HAART adherence in culturally diverse patients with HIV/AIDS: a study of male patients from a Veteran’s Administration hospital in northern California. AIDS Patient Care. 2004;15:117–127. doi: 10.1089/108729101750123562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piantadosi S. Clinical Trials: A Methodological Perspective. New York: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fishbein M, Yzer M. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication Theory. 2003;13:164–183. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: A Reasoned Action Approach. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, et al. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-N1 RNA viral load. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43:S23–S35. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248342.05438.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannheimer SB, Morse E, Matts JP, et al. Sustained benefit from a long-term antiretroviral adherence intervention: results of a large randomized clinical trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43(suppl):S41–S47. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000245887.58886.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holzemer WL, Bakken S, Portillo CJ, et al. Testing a nurse-tailored HIV medication adherence intervention. Nursing Research. 2006;55:189–197. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simoni JM, Frick PA, Pantalone DW, et al. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: a review of current literature and ongoing studies. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2003;11:185–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walkup J, Blank M, Gonzalez JS, et al. Mental health and substance abuse factors having an impact on HIV prevention and treatment. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(suppl):S15–S19. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605b26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:2611–2629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller V, Phillips AN, Bonaventura C, et al. Association of virus load, CD4 cell count, and treatment with clinical progression in human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients with very low CD4 cell counts. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;186:189–197. doi: 10.1086/341466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunt PW, Deeks SG, Rodriguez B, et al. Continued CD4 count increases in HIV-infected adults experiencing 4 years of viral suppression on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003;17:1907–1915. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]