Abstract

Background

After spinal cord injury (SCI), people are confronted with abrupt discontinuity in almost all areas of life, leading to questions on how to live a meaningful life again. Global meaning refers to basic ideas and goals that guide people in giving meaning to their lives, in specific situations. Little is known about global meaning relating to SCI and whether global meaning changes after SCI.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was twofold: (i) to explore the content of global meaning of people with SCI, and (ii) to explore whether or not global meaning changes after SCI.

Methods

In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 people with SCI. Interviews were analyzed according to the method of grounded theory.

Results

(i) Five aspects of global meaning were found: core values, relationships, worldview, identity and inner posture. (ii) Overall, little change in the content of global meaning was found after SCI; specific aspects of global meaning were foregrounded after SCI.

Conclusion

Five aspects of global meaning were found in people with SCI. Global meaning seems hardly subject to change.

Keywords: Global meaning, Spinal cord injury, Rehabilitation, Qualitative research

Introduction

A traumatic life event, such as spinal cord injury (SCI), constitutes a major threat to the meaning people give to their lives.1 After SCI, people are confronted with abrupt discontinuity in almost all areas of life. Practical challenges have to be faced, together with questions on how to live a meaningful life again.2 In the rehabilitation process, people are trained to deal with the physical, psychological, and social consequences of life with SCI.3 In this process of adaptation and rehabilitation “global meaning” may be a source of direction and continuity.

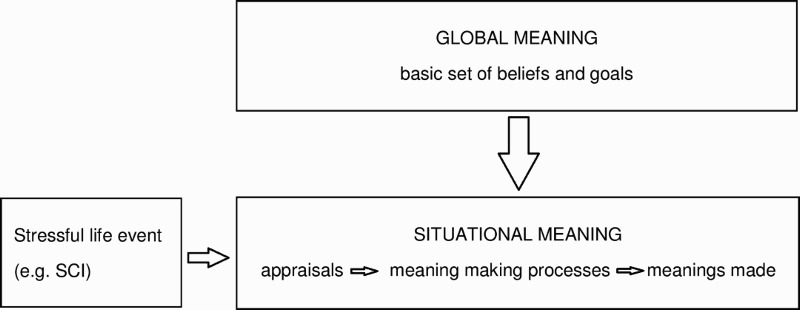

Park has reviewed the literature regarding meaning and its effect on adjustment to stressful life events.1,4 Park uses the term global meaning to refer to global beliefs (e.g. views regarding justice, coherence or control) and global goals (e.g. health or relationships), guiding people in living their lives. Global meaning provides individuals with cognitive frameworks, to interpret their experiences, and to motivate them in their actions. Global meaning is to be seen as the more fundamental level, and needs to be differentiated from situational meaning. Situational meaning refers to meaning in the context of a particular situation, e.g. a stressful life event like SCI. Situational meaning contains appraisals (specific beliefs about the stressful life event), which lead to meaning making processes (psychological processes aiming at giving meaning to the stressful life event), which result in meanings made (the outcome of these processes). Situational meaning is driven by a person's global meaning. This is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The relationship between global meaning and situational meaning.

The concept of global meaning has been described in several terms in various disciplines.1,4–9 Although different terms are used, there is clearly congruence among these authors on the concept of a basic set of beliefs and goals, that guides the way in which people give meaning to their lives (i.e. “global meaning”).

Psychological research on SCI focuses mainly on aspects of situational meaning or meaning making, e.g. adjustment or post traumatic growth.10–16 Psychological research on SCI includes studies on spirituality and purpose in life; although rarely studied, these factors have been shown to be associated with better mental health, higher quality of life and reduced mortality.15,17,18Although studies on spirituality or post traumatic growth in people with SCI mention aspects of global meaning, to the best of our knowledge, a more extensive exploration of the content of global meaning in people with SCI does not seem to be available. Furthermore, it is not known whether after SCI global meaning remains stable, or is subject to change. Park notes that global meaning tends to be stable after a stressful life event,1 however, none of the studies she reviewed regard SCI. Therefore, the purpose of this study was twofold: (i) to explore the content of global meaning of people with SCI, and (ii) to explore whether or not global meaning changes after SCI.

Methods

Design

To explore the concept of global meaning, interviews were conducted with people with SCI by the first author. Subsequently, the interviews have been analysed by the first and fourth author, using the qualitative research method of grounded theory. Interviews were held between 6–24 months after admission to the rehabilitation centre. It was expected that in this phase participants would be able able to reflect on their lives, their global meaning and possible changes. Presumably, they had had time to realize what had happened and to find a way to deal with their SCI, while still being able to remember how they thought and felt before they had to live with their disability. The study was approved by the accredited Medical Research Ethics Committee Slotervaart Hospital and Reade (METC-study number P1153).

Participants

Participants were recruited from clients who received treatment at Reade, centre for rehabilitation and rheumatology. They had been discharged from the rehabilitation centre, and were in outpatient rehabilitation. Clients with severe communication problems and psychiatric problems were excluded. Participants were purposively selected to include both men and women, younger and older clients, clients with or without a religious background, and clients with a more optimistic or a more pessimistic attitude (according to the physician in attendance). A letter was sent to potential participants, to which they could respond by returning a consent form.

Data collection

The main method of data collection was the conduct of semi-structured interviews with 16 participants, which, with permission of the participants, produced 16 audio-recordings. The majority of interviews took place at participants' homes. On average, interviews lasted one hour. They were conducted between August 2012 and July 2013. The interviewer minutely registered through field notes the observations she made before, during and after the interview, giving details on the broader interview situation, such as the occasional presence of a partner or friend, and nonverbal aspects of the communication.

Interviews were loosely structured using a topic list, based on literature concerning global meaning (see appendix 1). Starting with an open question: “What has happened?” subsequent questions were: “What has changed?”, and “What has not changed?” With the topic list in mind as a guideline, the interviewer followed the natural flow of the conversation. By summarizing and rephrasing what she heard, the researcher constantly tested her assumptions during the interview, getting to the deeper layers of global meaning. By asking the same question in different words, she tested if the respondent was telling about inner posture, for example.

The subjects on the topic list revolved around: change and continuity, a person's values, self-image, worldview, life-goals, and ideas on suffering. Based on the information revealed by interviews already administered, the topic list was continuously evaluated and adjusted. It was found, for example, that participants would say: “I am the kind of person that …” and talked about their identity. In subsequent interviews participants were asked to finish that sentence.

Data analysis

In order to analyse the data, verbatim transcriptions were made of the recorded interviews, which were then analysed by two researchers, using the method of grounded theory.19 Data were entered into a software program for qualitative data analysis and research, Atlas.ti (version 7.1.6, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development, GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The analysis was based on the transcribed interview recordings, using interviewer's impressions, reported in field notes, as background material. The actual recording was readily available through Atlas.ti, and used when listening to the tone of statements and remarks. The initial interviews were open coded in order to find aspects of global meaning, and change in global meaning. The codes found were grouped into concepts, and these concepts were gathered into larger categories, which the researchers suspected to be aspects of global meaning. When seven interviews had been conducted, transcribed and analyzed in this way, an overview was made of the aspects of global meaning found in each interview. On the basis of these overviews and categories the next interviews were analyzed, searching for these and deviant aspects of global meaning, continuity and change. When the analysis reached its saturation point at 16 interviews, five aspects of global meaning had been clearly identified from the data.

Results

Out of 29 invitations, 17 participants reacted positively, leading to 16 interviews, with one interview being cancelled due to medical reasons. 9 participants were male, 7 were female; the age ranged from 26 to 79 (Table 1). The participation of male–female respondents was 59–41%, while the whole population of newly admitted patients in the rehabilitation centre in that period was 74–26%. When 13 of the 16 interviews had been conducted, the researchers felt that a saturation point had been reached; an assumption confirmed by the fact that the last three interviews brought very little new information to light.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristics | Mean (range) |

|---|---|

| Average age (in years) | 57.25 (26–79) |

| Time post-injury (in months) | 16.19 (9–24) |

| Characteristics | No. |

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 |

| Female | 7 |

| Country of birth | |

| Netherlands | 13 |

| Morocco | 1 |

| Curaçao | 1 |

| Egypt | 1 |

| Social status | |

| Single | 5 |

| Single with children | 1 |

| Married/living together with children | 2 |

| Married/living together without children | 7 |

| Living apart together | 1 |

| Education | |

| Lower general professional training | 2 |

| High school | 6 |

| Community college | 2 |

| Undergraduate school | 4 |

| Graduate school | 2 |

| Religious background | |

| Christian | 4 |

| Muslim | 3 |

| Atheist | 1 |

| None | 6 |

| Other | 2 |

| Type of lesion | |

| Paraplegia | 11 |

| Tetraplegia | 5 |

| Completeness of lesion | |

| Complete | 3 |

| Incomplete | 13 |

Aspects of global meaning

The analysis of the interviews resulted in five aspects of global meaning: core values, relationships, worldview, identity and inner posture. These aspects are all relevant, but in different persons different aspects are more prominent. Although distinguished for reasons of clear presentation, in practice the different aspects of global meaning are often interwoven. One statement can show identity, core values, relationships and inner posture at the same time. In general people do not have a conscious, well formulated, idea of their global meaning. For example, they do not have a clear set of values, that they can easily sum up. However, this does not mean that they do not have values. People's core values can be found by exploring what is important to them, or what they value in other people.

Core values

Based on the narratives of the participants and literature on global meaning,9 we define core values as beliefs about what is right and worthwhile. Core values are self-evident, and guide behavior, and in this sense they are prescriptive. This is shown in the following example of a mother of four adult sons. It is important to her, that she does not become a nuisance now that she is disabled. In this quote she implicitly shows core values like care and responsibility for the people around her.

“It wouldn't help [being angry about the situation], because the boys also need to go on and pick up their lives again. And then there should not be some angry mother behind them.” “I would find it terrible, to become a bother. (…) You are a bother already a little in this situation, but that I can't help. What I can do about it, however, I will certainly do.” (Dutch woman, 65, married, Christian, undergraduate school, paraplegia, incomplete)

To another respondent, the core value of “showing interest in people” is important. This is how he finds or gives meaning, even though he is living in a nursing home as a consequence of SCI. The way he changes from “I” to “you” shows the self-evidence and the prescriptive element.

“I have a certain interest in people, yes. In (nursing home) there was a nurse, she struggled with her youngest child, with his health. Nothing serious, but it bothered her. Well, I ask … then you ask about him. “Is everything all right?” And then you ask a second time.” (Dutch man, 78, single, other religious background, high school, paraplegia, complete)

Relationships

When asked what makes life worthwhile, participants often answer in terms of relationships with significant others. Meaningful relationships and the experience of being connected are important goals in life. Spouses, children and friends, sometimes a pet, are often mentioned as giving meaning to life, being specifically important during rehabilitation and the difficult period after SCI.

Respondent: “Yes, I go on. Or I aim to, anyway. I try.”

Interviewer: “Can you tell me why?”

Respondent: “I have two daughters. And a wife, and a dog. And I still enjoy living.” (Dutch man, 67, married, no religious background, high school, paraplegia, incomplete)

When asked what is most important in his life, now that he is paralyzed and has to spend most of his time in bed as a result of SCI, a young man answers:

“Friendship. Because friends stand by me now. So yes, that is the best investment you can do in your life, isn't it?” (Dutch man, 26, married, Muslim, high school, tetraplegia, incomplete)

Worldview

When people look for explanations for the events that happen in life, their worldview will give structure to their ideas on how these are related. Worldview becomes pre-eminently clear when people express their view on suffering and their reaction to stressful life events. Compare these completely different views for example. However much different, they all provide structure and therefore meaning.

“Does suffering have meaning? No, no, it just happens to a person. Anything can happen to anyone.” (Dutch woman, 68, single, Christian, community college, tetraplegia, incomplete)

“Yes, that's what I always think: things happen for you to learn something.” (Curaçaoan woman, 61, single, Christian, high school, paraplegia, incomplete)

“I myself have always believed: Jesus has suffered for mankind, so suffering just shouldn't be necessary.” (Dutch woman, 57, married, Christian, graduate school, paraplegia, complete)

A person's view on suffering influences how she deals with traumatic life events. The same goes for ideas transcending life on earth, also part of one's worldview. The last quote comes from a participant, who contracted her SCI during a shooting accident in a shopping mall. Earlier in the interview she expresses her worldview of the kingdom of God breaking through, which gives her strength to go on, after this traumatic event.

“Well, I believe. In God. And also that the shooting accident does not have the last word, but that the kingdom of God breaks through.” (Dutch woman, 57, married, Christian, graduate school, paraplegia, complete)

Identity

People show a tendency to express who they are, by telling stories about themselves, about what kind of person they are. This is important to them because it structures their lives and describes their place in this world. It provides a sense of belonging, which gives meaning to their lives. At the same time it is a way of underlining their uniqueness, an expression of self-worth. When asked what has changed in his life, and if he himself has changed, after SCI, a young man answers:

“As a person I have become even more enthusiastic, even more positive. I am a party animal, so I like to chat around a little. (…) I grew up here in (big city), so I don't know anything else. So, yes, being positive, that's just part of our nature, here in the Netherlands. (…) My perseverance and my strength, that I am so strong, that is because of my childhood. Because, in my childhood, I have had my share of problems and, yes, that only makes you stronger, of course. I am a Moroccan boy, I am gay.” (Moroccan man, 42, single, Muslim, high school, paraplegia, incomplete)

This quote shows several aspects of this participant's identity. He expresses personal characteristics as well as his being part of larger groups.

Another example of identity providing meaning and self-worth, is found in the following quote. This woman always was someone who wanted to know, to learn, to examine, just a little deeper than other people. This helps her to deal with her SCI as well.

“Yes, I do want to know the cause [of the SCI], I do. That is who I am. (…) I am someone, who, when I want to know something, wants to know everything. Also what is at the bottom, under the bottom, preferably. Someone else may think ‘What do I care? It is written,’ but I go beyond what is written.” (Dutch woman, 68, single, Christian, community college, tetraplegia, incomplete)

Inner posture

When confronted with painful events in their lives, people tend to encourage themselves, or to calm themselves with prayer or meditation, or they remind themselves of what they have learned earlier in life. This helps people to bear what cannot be changed. Inner posture includes an element of acknowledgement and an element of choice and action. It involves acknowledging the facts and choosing how to relate to the facts.

A good example can be found in the next quote, where the participant refers to the tragedy of losing her sister at a young age.

“Should you give meaning to something like this? I would say: don't do it. Because, my mother, I still can hear her say … She didn't know what to do with it either, of course, and she said: whom God loves, he chastises. (…) Well. I think that is horrible. Well, then you think: yes, well, I will make it without meaning and just let it happen and make the best of it.” (Dutch woman, 65, married, Christian, undergraduate school, paraplegia, incomplete)

In contrast to what she had seen her mother do, when her sister died, this participant developed an inner posture of ‘not giving meaning to what is meaningless' and ‘making the best of it’. This is not just a philosophy of life, but it involves acting upon this philosophy. When confronted with suffering, she reminds herself and others, that this is how she sees things. This inner posture helps her to live with her SCI as well.

A young man with SCI expresses his inner posture of looking at the good things in life. He chooses to pay more attention to the good things than to the bad things:

“[People ask:] does it not gnaw at you? I say: no. No. I won't allow it to gnaw at me.” (Moroccan man, 42, single, Muslim, high school, paraplegia, incomplete)

Another respondent shows his inner posture as follows:

“Now, come on, keep going. And one more time, … keep going. I just want to keep going.” (Dutch man, 74, living apart together, other religious background, undergraduate school, paraplegia, incomplete)

This respondent wants to keep going. When things get difficult, he will cry, but not for too long. After a while he tells himself to “keep going.” This inner posture influences his behavior and his actions. For example: he did all he could, to be transferred from a nursery home where people were waiting for death to come, because he could not live among people that did not want to keep going. He chooses to live in an environment that empowers his own inner posture.

Continuity and change in global meaning

In general, continuity appears to be the tendency when it comes to continuity or change in global meaning.

“In my situation, the way I know myself … (own name) is still (own name). Nothing different about that. Yes, I have a … I am (own name) with a little extra.” (Moroccan man, 42, single, Muslim, high school, paraplegia, incomplete)

This respondent realizes that, as a result of his SCI, a lot has changed in his life, but he describes the changes as circumstantial. He himself, his identity, has not changed.

Even though the general tendency for global meaning is not to change, sometimes, after SCI, changes seem to occur in aspects that are part of global meaning. For example, in this respondent's identity, something seems to have changed.

“Are there things that have changed? Yes. I have always been a little bit of a loner. And of course you have to be careful with that, when something like this happens to you. You just need people much more. But also my attitude in this respect has changed. And also, I am, very strange to say, but much more … Most people talk more about themselves to me now. About their worries, their problems. Even in a way that now and then I get the feeling: I resemble the local Wailing Wall. Maybe it's because… I have more patience these days.” (Dutch woman, 63, single, atheist, high school, paraplegia, complete)

This respondent reports a change in her identity in relation to others, as a consequence of her SCI. The question remains whether this is really a change in her identity, or mainly a change in the way people react to her since her SCI.

Although no fundamental changes are found, aspects of global meaning are foregrounded in confrontation with a stressful life event like SCI. People become more aware of aspects of their global meaning, when they are confronted with vulnerability, and pain, and death.

“Got many reactions. Very many visitors. In (hospital) as well as in the rehabilitation centre. And that does surprise me.” (Dutch man, 71, married, no religious background, undergraduate school, paraplegia, incomplete)

This respondent has become more aware of the importance of relationships with family and other people in his life. Earlier in the interview, when talking about his work, he describes himself as a person that needs to have a “click” with other people to do business with them. Apparently relationships were always important to him, although he did not realize that at the time.

Especially inner posture becomes more prominent after SCI. When confronted with a life that has changed in many ways, people become more aware of the way they try and live with those changes. The inner posture of the woman that had been in the shooting accident, always was one of looking for boundaries and gradually trying to push them. After SCI, she becomes more aware that this is the way she always lived, but now she does it more deliberately and carefully.

Respondent: “That is how I explore the boundaries and I recognize that it is important to start close at hand. Because, when I go too far away and too far across, well … that is at the expense of things nearby. I rather push the boundaries, than that I just go overboard one or two times.”

Interviewer: “And is that how you were before the shooting accident and how you operated? Or has that changed afterwards?”

Respondent: “Well, I am more consciously pushing boundaries now.” (Dutch woman, 57, married, Christian, graduate school, paraplegia, complete)

Discussion

The scope of our study was global meaning, a concept not extensively studied in people with SCI before. Global meaning, being the more fundamental level of meaning, has to be differentiated from situational meaning. Situational meaning and the process of meaning making are driven by a person's global meaning. This can be illustrated looking at a quote we presented in the results:

“Yes, I do want to know the cause [of the SCI], I do. That is who I am. (…) I am someone, who, when I want to know something, wants to know everything. Also what is at the bottom, under the bottom, preferably. Someone else may think ‘What do I care? It is written,’ but I go beyond what is written.” (Dutch woman, 68, single, Christian, community college, tetraplegia, incomplete)

The situational meaning in this quote is, that the respondent wants to know everything there is to know about the cause of her SCI. This is how she finds meaning in this particular situation. This is, however, not only relevant for this situation, but part of her identity: she considers herself to be a person who wants to know, to learn, to examine, to dig deeper than other people. So she uses an element of global meaning, to explain and support the meaning making process in the specific situation.

We identified five aspects of global meaning in people with SCI: core values, relationships, worldview, identity and inner posture. The operationalizations of these aspects (Box 1) are based on the narratives of the participants, combined with the literature on global meaning.1,4–9 Four of these aspects – core values, relationships, worldview, identity – have been described in studies on global meaning in the broad area of stressful life events, but not specifically SCI.1,17,18,20 Core values are global beliefs about what is right and worthwhile. They give direction to thoughts and behavior. Relationships refer to a connection between a person and others, e.g. children, a spouse, a therapist or even a pet. Meaningful relationships and the experience of being connected are global goals in life.Worldview is a more or less coherent set of global beliefs about life, death, and suffering, that structure people's ideas on how life events are related. Identity refers to global beliefs about one's deepest self, about who, rather than what a person is. Expressing one's identity provides people with a sense of belonging, at the same time underlining their uniqueness and self-worth.The fifth aspect, inner posture, originates in Buddhism and is used in yoga and in the practice of spiritual counselling. Using a different terminology, the concept is also found in the fields of philosophy and psychotherapy: the stoics refer to inner posture as “attitude,”21 while Frankl describes the attitude a person can choose in the face of unavoidable suffering.6

Box 1.

Aspects of global meaning

| Core values | Relationships | Worldview | Identity | Inner posture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core values are global beliefs about what is right and worthwhile. They give direction to thoughts and behavior. | Relationships refer to a connection between a person and others. Meaningful relationships and the experience of being connected are global goals in life. | Worldview is a more or less coherent set of global beliefs about life, death, and suffering, that structure people's ideas on how life events are related. | Identity refers to global beliefs about one's deepest self, about who, rather than what a person is. Expressing one's identity provides people with a sense of belonging, at the same time underlining their uniqueness and self-worth. | Inner posture helps people to bear what cannot be changed. It includes an element of acknowledgement and an element of choice and action. It involves acknowledging the facts and choosing how to relate to the facts. |

The different aspects of global meaning are closely connected. For example, the 42-year-old man with the identity of the positive, strong, Moroccan, gay boy, has an inner posture of looking at the positive side of life, and a worldview in which you get what you give. In his view, positivity and goodness are part of life: do well and get well.

Psychological research on SCI includes studies on social support,22–25 sense of self,18,26,27 purpose in life,15,18,26 spiritual coping28 and spirituality.4,16,29,30 In studies on social support the importance of supportive relationships is widely recognized.22–25 However, these studies focus on the role relationships play in adapting to SCI, in other words: they focus on situational meaning. Our study addresses relationships as a global goal, i.e. relationships as an aspect of global meaning. The same applies to the studies on sense of self, purpose in life and spiritual coping. Sense of self is related to our concept identity; purpose in life and spiritual coping are related to worldview; however, studies on sense of self, purpose in life or spiritual coping mainly focus on psychological adaptation to SCI, i.e. situational meaning, while our study addresses identity and worldview as aspects of global meaning. Spirituality can indeed be seen as an element of worldview, but worldview is a more comprehensive concept.

We observed continuity rather than change in global meaning after SCI. This corresponds to what is found in literature on global meaning. Most researchers use the phrase “not likely to change” or “resistant to change,” relating to (aspects of) global meaning after a traumatic event.1,7–9,20 In our study, we also found little evidence of fundamental change: no fundamental changes in global meaning after SCI were reported. However, people did become more aware of specific aspects of their global meaning. Aspects of global meaning, which were already present prior to SCI, were foregrounded; after SCI, participants became more aware of these aspects of global meaning. This applied in particular to inner posture; people became aware of how they had dealt with difficulties in their lives prior to SCI, and used that inner posture to deal with SCI and its consequences.

It has been hypothesized that the process of adaptation to a traumatic event is guided by people's global meaning: global beliefs and goals guide the process of adaptation.1,13,20 Given its prominence and apparent stability, it can be hypothesized that this applies also to global meaning in people with SCI: core values, relationships, worldview, identity and inner posture can be hypothesized to guide the process and outcome of rehabilitation after SCI. People with SCI seem to be aware of their global meaning, and global meaning seems to be rather stable. Therefore, global meaning may be a source of direction and continuity during the rehabilitation process after SCI. In future research, we will explore this hypothesis.

Strengths and limitations of the study

In the analysis, it was not always easy to distinguish global meaning from situational meaning. People usually do not have a clearly formulated worldview or identity, and they are not able to sum up their core values. Indicators in the data, that the level of global meaning was reached, were sudden changes of subject, emotions, silences, and metaphors. If both researchers who analysed the interviews identified a quote as referring to global meaning, it was perceived as a strong clue that global meaning was actually referred to.

The interviews were all conducted after SCI. Obviously we were not able to interview the respondents before SCI. The interviews therefore reflect the view of the respondents in retrospect. As a result, we can not be sure if the reported change or continuity is, at least partly, a result of retrospective bias. It is possible that people were not able to recall their past view on global meaning, or that they changed more than they remembered. However, our results show, how the respondents reflect on their current and former global meaning.

The interviews in our study took place between 6 and 24 months after onset of SCI, and we found little change in global meaning. In other studies, it was found that between 2 and 5 years changes occur in the ratings persons with SCI give to their subjective QOL.18 Although these studies did not study global meaning, this can be an indication that after a longer period of time changes may be reported in global meaning as well.

In some interviews a spouse or a friend was present. This can be seen as both a limitation and a strength. On the one hand, the respondent may not have told everything, because he wanted to protect his spouse from certain ideas. On the other hand, the interaction between the respondent and the spouse or friend provided the interviewer with information about the relationship between the two, and sometimes the spouse stimulated the respondent, by reminding him of earlier actions or statements he himself did not think of telling.

Conclusion

In this study, five aspects of global meaning were found. Four have been previously reported in research on global meaning, whereas inner posture has been described in other disciplines, like philosophy and spiritual counselling. In the period between 6 to 24 months after onset of SCI, global meaning appears to be relatively insensitive to change. We expect it to be a possible source of motivation and continuity in the process of rehabilitation after SCI. However, the extent to which global meaning influences the process of rehabilitation has not yet been studied. Therefore, further research is recommended to study the influence of global meaning on the process and outcome of rehabilitation.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the cooperation of Reade and of course the participants, who generously welcomed us into their houses and lives.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors All authors have made a substantial contribution to this paper. The design was made by the first author, under supervision of the sixth author. The interviews were conducted by the first author. The analysis was conducted by the first and fourth author. The second, third, fifth and sixth author contributed substantially in writing the article and guiding the process of analysis. The sixth author was the overall supervisor.

Funding This study was financed by het Revalidatiefonds (projectnumber R2011192), and it won the Duyvensz-Nagel Stichting Fellowship 2012.

Conflicts of interest The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval The study was approved by the accredited Medical Research Ethics Committee Slotervaart Hospital and Reade (METC-study number P1153).

Appendix 1

Topiclist global meaning

Could you tell me what happened to you?

What has changed?

What has remained the same?

Do you think your SCI has a meaning or a purpose?

Do you think life in general has a meaning or a purpose?

What is really important to you in life?

When do you get annoyed?

What do you hope others will say or think about you?

If I ask you: “Who are you?” what would be your answer? (Please finish the sentence: I am … someone who …)

Could you share some of your thoughts about death with me?

How do you manage to live with your SCI?

Has what we have discussed so far affected your rehabilitation? In what way?

Is there anything else you would like to say, in reaction to the interview so far?

How did you experience this interview?

References

- 1.Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol Bull 2010;136(2):257–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen HY, Boore JR. Living with a spinal cord injury: a grounded theory approach. J Clin Nurs 2008;17(5A):116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer S, Kriegsman KH, Palmer JB. Spinal cord injury: a guide for living. 2nd ed Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park CL. The meaning making model: a framework for understanding meaning, spirituality, and stress-related growth in health psychology. European Health Psychologist 2013;15(2):40–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mooren JH. Trauma, coping and meaning of life. Praktische humanistiek 1998;7(3):21–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankl VE. Man's search for meaning. An introduction to logotherapy. 4th ed Boston: Beacon Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koltko-Rivera ME. The psychology of worldviews. Rev Gen Psychol 2004;8(1):3–58. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered assumptions: towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: The Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rokeach M. Understanding human values. New York: The Free Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dibb B, Ellis-Hill C, Donovan-Hall M, Burridge J, Rushton D. Exploring positive adjustment in people with spinal cord injury. J Health Psychol 2013;19(8):1043–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeRoon-Cassini TA, de St AE, Valvano A, Hastings J, Horn P. Psychological well-being after spinal cord injury: perception of loss and meaning making. Rehabil Psychol 2009;54(3):306–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeRoon-Cassini TA, de St AE, Valvano AK, Hastings J, Brasel KJ. Meaning-making appraisals relevant to adjustment for veterans with spinal cord injury. Psychol Serv 2013;10(2):186–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chun S, Lee Y. The experience of posttraumatic growth for people with spinal cord injury. Qual Health Res 2008;18(7):877–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalpakjian CZ, McCullumsmith CB, Fann JR, Richards JS, Stoelb BL, Heinemann AW, et al. Post-traumatic growth following spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2014;37(2):218–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson NJ, Coker J, Krause JS, Henry E. Purpose in life as a mediator of adjustment after spinal cord injury. Rehab Psychol 2003;48(2):100–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy P, Lude P, Elfstrom ML, Cox A. Perceptions of gain following spinal cord injury: a qualitative analysis. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2013;19(3):202–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peter C, Muller R, Cieza A, Geyh S. Psychological resources in spinal cord injury: a systematic literature review. Spinal Cord 2012;50(3):188–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Leeuwen CM, Kraaijeveld S, Lindeman E, Post MW. Associations between psychological factors and quality of life ratings in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2012;50(3):174–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed London: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma & transformation. Growing in the aftermath of suffering. London: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epictetus Enchirion. In: Negri P, Crawford T, editors. Epictetus Enchirion. Mineola: Dover Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller R, Peter C, Cieza A, Geyh S. The role of social support and social skills in people with spinal cord injury—a systematic review of the literature. Spinal Cord 2012;50(2):94–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Leeuwen CM, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, van der Woude LH, de GS, Lindeman E. Social support and life satisfaction in spinal cord injury during and up to one year after inpatient rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med 2010;42(3):265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whalley HK. Experience of rehabilitation following spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord 2007;45(4):260–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Hsieh JT, Wolfe DL. The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma 2012;29(8):1548–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peter C, Muller R, Cieza A, Post MW, van Leeuwen CM, Werner CS, et al. Modeling life satisfaction in spinal cord injury: the role of psychological resources. Qual Life Res 2014;23(10):2693–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lennon A, Bramham J, Carroll A, McElligott J, Carton S, Waldron B, et al. A qualitative exploration of how individuals reconstruct their sense of self following acquired brain injury in comparison with spinal cord injury. Brain Inj 2014;28(1):27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matheis EN, Tulsky DS, Matheis RJ. The relation between spirituality and quality of life among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehab Psychol 2006;51(3):265–71. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monden KR, Trost Z, Catalano D, Garner AN, Symcox J, Driver S, et al. Resilience following spinal cord injury: a phenomenological view. Spinal Cord 2014;52(3):197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weitzner E, Surca S, Wiese S, Dion A, Roussos Z, Renwick R, et al. Getting on with life: positive experiences of living with a spinal cord injury. Qual Health Res 2011;21(11):1455–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]