Abstract

Therapeutic interpersonal relationships are the primary component of all health care interactions that facilitate the development of positive clinician–patient experiences. Therapeutic interpersonal relationships have the capacity to transform and enrich the patients’ experiences. Consequently, with an increasing necessity to focus on patient-centered care, it is imperative for health care professionals to therapeutically engage with patients to improve health-related outcomes. Studies were identified through an electronic search, using the PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and PsycINFO databases of peer-reviewed research, limited to the English language with search terms developed to reflect therapeutic interpersonal relationships between health care professionals and patients in the acute care setting. This study found that therapeutic listening, responding to patient emotions and unmet needs, and patient centeredness were key characteristics of strategies for improving therapeutic interpersonal relationships.

Keywords: health, acute care, therapeutic interpersonal relationships, relational care integrative review

Introduction

A therapeutic interpersonal relationship can be defined as one which is perceived by patients to encompass caring, and supportive nonjudgmental behavior, embedded in a safe environment during an often stressful period.1 These relationships can last for a brief moment in time or continue for extended periods.2 Typically, this type of relationship displays warmth, friendliness, genuine interest, empathy, and the wish to facilitate and support.3 Consequently, therapeutic interpersonal relationships engender a climate for interactions that facilitate effective communication.4 Therapeutic interpersonal relationships between health care professionals and patients are associated with improvements in patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment, quality of life, levels of anxiety and depression, and decreased health care costs.4–6 Conversely, increased psychological distress and feelings of dehumanization are associated with negative clinician–patient relationships.4

In the health care literature, numerous terms have been used to describe this type of relationship, including helping relationships, purposeful relationships, nurse–client relationships, and therapeutic alliances. For the purpose of this review, they have been grouped under the term “therapeutic interpersonal relationship” as they all relate to a focused relationship between the health professional and the patient directed at achieving the best patient outcome. The concept is also interrelated with that of patient-centered care. Patient-centered care (also known as person-centered or patient- and family-centered care) describes a standard of care that ensures the patient and their family are at the center of care delivery.7 Patient-centered care requires health care professionals to have the ability to form therapeutic interpersonal relationships that elicit patients’ true wishes and recognize and respond to both their needs and emotional concerns.8

Although therapeutic interpersonal relationships are widely acknowledged as being central to a constructive clinician–patient experience,9 achieving them in the acute care setting is extremely challenging.10,11 One of the main barriers is the fact that patient care in this setting is heavily grounded in a task-centered approach.12 McQueen13 argues that “if we are to realize the full benefits of therapeutic interpersonal relationships, then strategies to enhance them in the acute care setting are required”. Therefore, the aim of this review is to identify strategies to enhance therapeutic interpersonal relationships between patients and health care professionals in the acute care setting.

Methods

Integrative review process

An integrative review is a research strategy involving the review, synthesis, and critique of extant literature.14 Integrative reviews allow a comprehensive understanding of what is known and, therefore, has the capacity to identify gaps in existing knowledge.15,16 Compared to a systematic review, integrative reviews generate new insights about a phenomenon, allow the inclusion of diverse methodologies and differing levels of data, and have the ability to inform future research trajectories.15,17 The framework driving this integrative review was based on Whittemore and Knafl’s15 five stages encompassing problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data synthesis, and presentation.

Literature search

A systematic search was conducted of PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Psy-cINFO. Boolean connectors AND, OR, and NOT were used to construct a search strategy using search terms that included doctor - patient relations*, nurse-patient relations*, person centered care, therapeutic relationship*, therapeutic alliance, therapeutic communit*, interpersonal caring, patient centered care, hospital*, experienc* and encounter*. In addition, the reference lists of potential papers retrieved were examined to identify any further material that met the inclusion criteria. Both versions of British and American spellings were used to construct the search strategy as to reflect a systematic and comprehensive approach.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search criteria incorporated original peer-reviewed research and literature that explored or investigated strategies pertaining to the development/enhancement of positive therapeutic interpersonal relationships between health care professionals and adult patients in the acute care setting. The concept of therapeutic interpersonal relationships is not confined to any specific time period or type of peer-reviewed publication, and so no limitations were placed on these parameters to ensure a broad and diverse scope of knowledge. It is recognized that the family is a significant component of a patients’ psychosocial well-being;18 however, literature that centered on the carer or family was excluded as the focus of this review was the health care professional–patient relationship. Papers that focused on pediatrics and adolescence were also excluded as this review focused on adult patient–staff interaction. In addition, papers involving student cohorts were also excluded as were papers that reported solely on satisfaction surveys.

Data evaluation

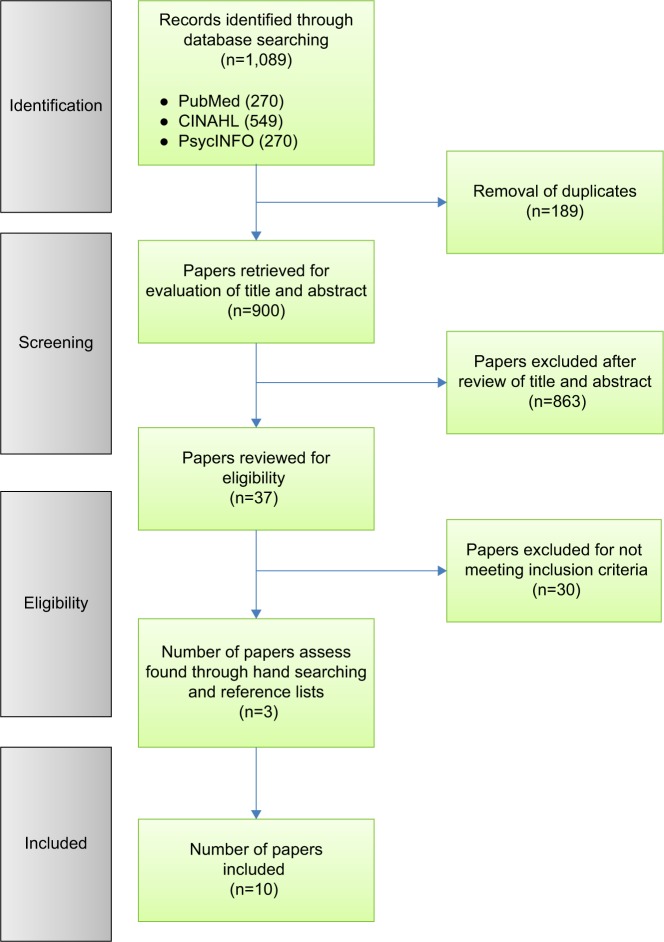

The search strategy initially identified 900 papers after removal of duplicates (Figure 1). The authors (RK and KW) independently identified 37 potential papers for inclusion based on titles and abstracts. The authors (RK, KW, and JD) independently appraised the 37 identified papers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements that arose were resolved by debate and consensus. Thirty studies were subsequently excluded, leaving a total of seven. The reference lists of the included studies were reviewed, which eventuated in the identification of three additional studies for inclusion with ten studies included in this integrative review.

Figure 1.

Decision trail of included studies.

Abbreviation: CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

Data extraction and synthesis

Initially, data from the ten studies were extracted and tabled accordingly: author, year, and country of origin, purpose, sample population, and significant findings/outcomes (Table 1 provides an abridged version of these). The findings were then integrated using a constant comparison method. Extracted data (qualitative and quantitative) were compared item by item, and similar data were categorized and grouped together into recurring themes. This approach to data analysis is used in integrative reviews because it is compatible with the use of varied data from diverse methodologies.15

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Author(s), year, and country | Design | Purpose | Sample and study population | Data collection method | Method of analysis | Significant findings and outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al,24 2012 (USA) | Qualitative | To understand how hospitalists respond to patients’ expressions of negative emotion and to identify how different types of responses influence further communication in the encounter | 79 patients, mean age 54 years: 36 males, 43 females; 27 physicians, mean age 35 years: 11 males, 16 females | Audio-recorded interviews | Thematic analysis | Clinicians should respond to expressions of negative emotion with statements that allow for or explicitly encourage further discussion of emotion |

| Greenberg,26 2003 (USA) | Qualitative | To explore humor within the context of nurse–patient relationships | Protracted data collection over 14 months; nurse–patient dyadic relationships; 3 nurses, 2 females, 1 male, 26–32 years in age, 1.5–5 years’ experience; 3 patients, 1 male, 2 females | 200 hours of observation, 25 hours of formal and informal interviews | Constant comparative method | Empowering clinicians involved in professional relationships a tactic for the development of humor as a caring strategy |

| Jagosh et al,23 2011 (Canada) | Qualitative | To convey attitudes, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings about experiences with physician care | 26 males, 32 females, ≥18–65 years | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis | Listening is an essential component of clinical data gathering and diagnosis; listening as a healing and therapeutic agent; listening as a means of fostering and strengthening the doctor–patient relationship |

| Jones et al,21 2011 (Australia) | Qualitative | To explore cancer patients’ perception of communication with their clinician during a supportive care screening and discussion process and the ways in which this process assisted communication | Convenience sample; 3 days after the supportive care discussion; 154 cancer patients: 72 men, 82 women, (4 patients) < 40 years, (128 patients) 40–79 years; (22 patients) >80 years; 36 clinicians conducted supportive care process | Semi-structured and open-ended questions | Thematic analysis | Screening and discussion through supportive care facilitated communication; a patient- centered process of supportive care can assist clinicians to meet the unmet needs of patients with cancer leading to an increased patient satisfaction |

| Lees,20 2014 (Australia) | Qualitative | To explore the experiences and needs that mental health care consumers have of suicidal crisis, the degree to which these needs are met, the role that mental health nurse engagement plays and the key factors suggested to impact on the quality of care | Survey population: mental health nurses (n=87); semi-structured interviews: mental health nurses 6 females, 5 males, average age of 48 years, average of 12 years’ mental health experience; consumers: 6 females, 3 males, average age of 41 years | Survey of mental health nurses, semi-structured interviews with subsection of nurses (n=11); semi-structured interviews with consumers recovering from suicidal crisis (n=9) | Survey: descriptive statistics; interviews: data analysis drew upon adapted forms of critical discourse, constant comparative and classical content analysis | Therapeutic interpersonal engagement between nurses and consumers is central to quality care; essential to consider educational preparation, workplace training, clinical supervision, and support available to nurses |

| Mitchell and McCance,22 2012 (UK) | Qualitative | To explore nurse–older person encounters and relationships within the context of person centeredness | Disproportionate stratified sampling; 50 inpatients >65 years | Interviews (conversational interviewing style) | Authentic Consciousness Framework | Nurses are often invisible to the patient unless they are delivering care to address a physical need, therefore a notion of “rolelessness” that deprives patients from actively participating in important decisions about their care; person- centered strategies must enhance the capacity of older patients and their ability to assert self; nurses must work to actively engage the patient in all decision making |

| Nørgaard et al,27 2012 (Denmark) | Quantitative | To investigate if adult orthopedic patients’ evaluation of the quality of care improves after communication skills training for health care professionals | 3,133 patients; hospitalized for >24 hours in two orthopedic wards: Ward A – primarily elderly patients; mean age of men 56.4 years; mean age of women 62.04 years; Ward B – trauma patients; mean age of men 46.68 years; mean age of women 65.92 years | Pre- and post- questionnaires | Statistical analysis STATA, version 11 | Increase in patient satisfaction with the quality of care received after attendance at communication skills training course (including attentive listening, silence, and summarizing skills); the necessity for clinicians to be trained in patient- centered communication across the health care spectrum |

| Sanghavi,25 2006 (USA) | Mixed method | “What makes for a compassionate patient-caregiver relationship?” | Multidisciplinary caregivers | Questionnaires and transcripts collected at 54 hospitals across 21 states | Theme development | Three major themes: communication, common ground, and respect for individuality; a prescription for change embracing support, regular guidance, repeated reinforcement, specific targeted outcomes, and more innovative care programs |

| Williams and Irurita,19 2004 (Australia) | Qualitative | To explore and describe, from the perspective of hospitalized patients, the perceived therapeutic effect of interpersonal interactions experienced during hospitalization | 40 recently hospitalized patients, 1 day to more than 15 days, 13 males, 27 females, age ranged from 29 to 93 years; 32 nurses | Semi-structured formal and informal interviews; 78 hours of field across two health care settings; relevant documentation pertaining to nursing care plans and patient notes | Constant comparative analysis; open, axial, and selective coding; NUD*IST software | Personal control is a central feature of emotional comfort, and accounts for the way in which patients interpret therapeutic and nontherapeutic interpersonal interactions encountered during hospitalization; identification of the characteristics of interpersonal interactions that facilitate emotional comfort allows direction for enhancing therapeutic potential in all interpersonal interactions experienced by hospitalized patients |

| Zandbelt et al,8 2007 (The Netherlands) | Mixed methods9,10 | To determine the association of specialists’ patient-centered communication with patient satisfaction, adherence, and health status | 30 physicians (15 staff physicians and 15 residents), 16 males, 14 females; mean years in practice 8.6 years; 330 patients, 138 males, 192 females, mean age 52 years | Questionnaires/scales and videotaped encounter | Coding behavior; statistical analysis | Patients were more satisfied when their medical specialist displayed more facilitating and less inhibiting behavior |

Abbreviation: NUD*IST, Nonnumerical Unstructured Data Indexing, Searching, and Theorizing.

Results

Study characteristics

Ten papers meeting the inclusion criteria were selected. These studies were conducted across seven countries, including Australia,19–21 the UK,22 Canada,23 the USA,24–26 Denmark,27 and the Netherlands.8 Papers predominately emanated from either Australia19–21 or the USA.24–26 The acute settings encompassed a broad area of health care including mental health, surgical, medical, trauma, gerontology, and oncology. Study participants primarily included patients, physicians, and nurses. Seven of the ten studies derived from a qualitative methodology with semi-structured interviews, and thematic analysis was the most frequently used data collection and analysis method. Two studies8,25 employed mixed methods including questionnaires, observations, and interviews; and one study19 had a qualitative design with a pre- and postintervention questionnaire.

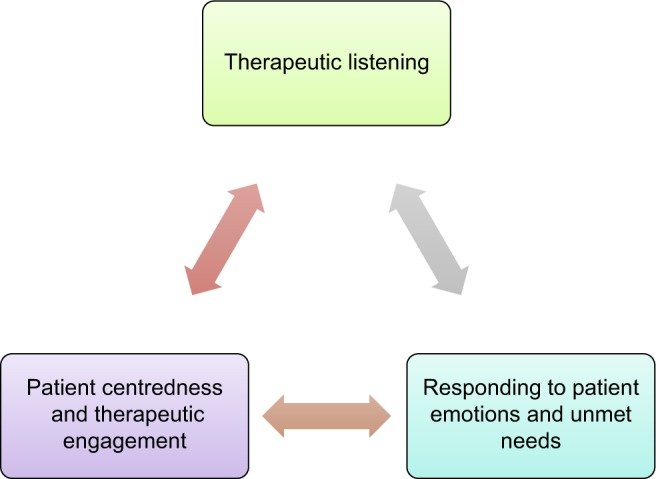

The strategies for therapeutic interpersonal relationships that emerged from the included studies were themed under the headings: “Therapeutic listening”; “Responding to patients’ emotions and unmet needs”; and “Patient centeredness and therapeutic engagement”. All three themes were interlinked and contributed to therapeutic interpersonal relationships (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual map of the relationships between the key strategies of therapeutic interpersonal relationships.

Therapeutic listening

In the course of an interpretative descriptive study of patients’ perspectives on improving patient-centered approaches to care delivery by physicians, Jagosh et al23 interviewed 58 patients from various backgrounds and with diverse care needs. During this study, it became apparent that physician listening was a recurring theme. Jagosh et al23 make the point that although listening is a skill emphasized in medical school curricula, there have been few studies that explore this from the patient’s perspective. In addition, much of the focus on listening has been with the intent of improving diagnostic accuracy. Although this theme was present in Jagosh et al’s23 study, two additional themes emerged: listening as an instrument to create and maintain good doctor–patient relationships and listening as a healing and therapeutic agent.

In the theme listening as a healing and therapeutic agent, listening was seen by patients as creating the conditions to promote healing and recovery:

Because if you listen to the patient and give the patient respect, what you are actually doing is helping that person take responsibility for their own health … they are also in control of the healing process and are involved somehow …23

Within the theme of listening as an instrument to create and maintain therapeutic interpersonal relationships, patients believed that listening helped physicians engage with their values and strengthen the therapeutic alliance:

The doctor needs to listen to you and to speak to you and it’s surprising, sometimes you can overcome some of your problems ….23

Jagosh et al23 conclude that listening can be an interpretive activity that contributes to a richer interpersonal dialogue, which can forge new understandings and meanings, especially in emotionally charged situations.

The development of the therapeutic interpersonal alliance relies on the use of high-quality communication skills. Nørgaard et al27 sought to investigate whether adult orthopedic patients’ evaluation of the quality of care improved after staff had undergone a communication skills training course. The course employed the Calgary-Cambridge Observation Guide in patient-centered communication as well as exercises in attentive listening, pausing, and summarizing. Participants were also involved in videotaped role play of simulated communication scenarios and follow-up sessions. Satisfaction of over 3,000 patients was assessed pre- and postintervention using the Interpersonal Skills Rating Scale. The study demonstrated statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction scores concerning the quality of information, continuity of information, and quality of care provided by health professionals after attending the 3-day course.

Responding to patients’ emotions and unmet needs

Adams et al24 study explored physicians’ responses to patients’ verbal expression of negative emotion to identify how different types of responses influence further communication. They state that although empathy is a key element of good patient–physician communication, physicians seldom respond with empathy to patients’ expression of negative emotions. Adams et al24 recorded 79 patient encounters with 27 physicians and examined physicians’ responses to patient expression of negative emotion that either focused the discussion away from the emotion, toward the emotion, or that did neither (neutral). The effect the response had on further communication was then examined.

Adams et al24 found that physicians’ responses that focused the discussion away from the negative emotion had the effect of distancing the physician and patient from each other and creating an antagonistic relationship. Neutral responses led to elicitation of the patient’s perspective and clarification of the goals of care. Toward responses tended to lead to the provision of emotional support, increased agreement about treatment, and facilitated the physician and patient alliance.

Similarly, a study by Zandbelt et al8 established that patient satisfaction was positively associated with doctors’ facilitating patients’ expression of their perspective and negatively associated with behaviors, which inhibited such expression, especially in patients who were less confident in communicating with their doctor. In addition, facilitating behaviors were positively related to adherence to treatment in patients with a language different to the health professional. Facilitative behaviors included attentive silence; verbal and nonverbal encouragements; summarizing patients’ words; and reflections of facts, emotions, and processes.

Jones et al21 found a formal process of supportive care that involved identifying unmet needs as identified by patients using a validated screening tool and a supportive care resource kit for clinicians, which improved communication between cancer patients and their clinicians. Patients in Jones et al’s21 study focused on the effectiveness of communication encompassing the areas of reflecting and clarifying needs; initiating discussions with clinicians; validating needs; seeking help and support; and focusing the clinicians’ attention and the therapeutic environment. The overall consensus of the participants was that the implementation of supportive care processes facilitated and, to an extent, enhanced therapeutic interpersonal communication.

Patient centeredness and therapeutic engagement

Patient centeredness and therapeutic engagement emerged as fundamental aspects of therapeutic encounters and relationships between health professionals and patients. Lees et al20 found that therapeutic interpersonal engagement between nurses and patients for suicidal crisis intervention was the central tenet in quality of care. Lees et al20 interviewed eleven nurses who had worked with suicidal clients and nine clients who had recently recovered from a suicidal crisis. Lees et al20 identified through these interviews that therapeutic engagement could facilitate a reduction in feelings of isolation, loss of control, and distress. Therapeutic engagement was seen by Less et al20 as incorporating rapport, listening, empathy, relating as equals, compassion, genuineness, trust, time responsiveness, and unconditional positive regard. Taking the opportunity to engage therapeutically was seen as crucial by one Registered Nurse in Lees et al’s20 study:

The opportunity to interact is the ultimate … it’s a really important interaction … It can be the difference between life and death.20

The importance of therapeutic engagement was made clear by a patient in Lees et al20 study who stated:

I wanted someone to sit down and talk with and go through it all … to just support me and ask me about it and how I was feeling … someone to make contact with me about it.20

Through a secondary analysis of interview data collected from older people, Mitchell and McCance22 explored encounters and relationships within the context of person-centered care. Mitchell and McCance22 identified that many older patients experience a sense of “rolelessness” and are deprived of active participation in their care. They state that nurse–patient encounters are largely dominated by task-orientated care, and therefore patients feel burdened by the perception that nurses are busy:

Well the nurses come in early in the morning and wash you … but apart from that, I just be in bed, you know. Nurses are supposed to look after you … I feel I’m just in here, I’m just left.22

These perceptions reinforce a culture of patient passivity within a health care climate that requires the implementation of strategies to enhance the capacity of person-centered care for both the patient and the nurses.

In contrast, Mitchell and McCance22 also identified five key aspects that defined person-centered care for elderly patients as encompassing informed mutuality – the opportunity for patients to be equal partners in decision making; transparency, making clear the intentions and motivations for actions and sympathetic presence; engagement with the patient that recognizes their value and uniqueness.

Respect for uniqueness or individuality was also one of the findings from a study by Sanghavi25 who reviewed the elements of compassionate patient–caregiver relationships. Sanghavi25 analyzed questionnaires and transcripts of rounds with patients, families, and staff conducted at 54 hospitals across 21 states in the USA. The analysis revealed communication, common ground, and respect for individuality as key aspects of compassionate relationships. Sanghavi25 states that traditional structures of health care delivery are inadequate to sustain a culture of compassionate care and that a new innovative approach to the delivery of health care is required. Aspects of the new paradigm (compassionate relationships) include activities such as the attendance at rounds that focus clinicians’ attention on the necessity for compassionate care, senior clinicians modeling behavior for junior health professionals, and teaching and reinforcement of compassionate interpersonal interactions throughout the career of the health professional to engender a culture of compassionate.

In a grounded theory study conducted in an acute care setting, Williams and Irurita19 explored the patients’ perception of the perceived therapeutic effect of interpersonal interactions with nurses. Interviews were conducted with 40 recently hospitalized patients, and participant observation and interviews were conducted with 32 nursing staff. The substantive theory of optimizing personal control to facilitate emotional comfort was developed. Emotional comfort was identified as an emotional state that enhanced patients’ recovery. During their admission, patients interpreted interpersonal interactions as either emotionally comforting or discomforting. Patients identified feeling insecure, uncertain, and devalued as of concern and feeling secure, valued, and informed as important for emotional comfort. In addition, the study identified six specific types of therapeutic interaction that contributed to emotional comfort. Patients felt emotional comfort when staff displayed ability and confidence in performing task; developed relationships through frequent contact and getting to know each other as people; were available and responded quickly to calls for assistance; provided information openly and honestly; used nonverbal interactions such as eye contact, touch, active listening, and positioning to enhance communication; and engaged in verbal interactions such as social chitchat and making encouraging comments.19

In a study on therapeutic play, Greenberg26 found that within the acute care setting, the use of humor facilitated emotional comfort and support and therapeutic engagement. Greenberg26 defined the use of humor as therapeutic play that enhances health and well-being by developing therapeutic interpersonal alliances in illness. Humor was used as an effective icebreaker and allowed the development of trust within the therapeutic interpersonal relationship. Greenberg26 states that mutual laughter is a powerful form of therapeutic interpersonal communication as it creates a culture of positive emotions between the patient and health professional as demonstrated by a participant nurse:

I use [humor] situationally. A lot of times you come into rooms and it is so confrontational because patients and families feel they are receiving some form of mistreatment. [Humor] tends to make you less threatening.26

Discussion

The catalyst for this review was the necessity to identify strategies that enhance therapeutic interpersonal relationships in the acute care setting. It was found that “Therapeutic listening”, “Responding to patient emotions and unmet needs”, and “Patient centeredness” were key characteristics of strategies for improving therapeutic interpersonal relationships. These three themes are depicted in Figure 2 as key interrelated components of therapeutic interpersonal relationships within the acute care setting.

The acute health care environment has been described as “dangerous, disconnecting, identity disaffirming, and without possibilities”.28 Shattell29 states that patients struggle to get health care professionals to listen and claim the necessity for an advocate such as a family member or friend present in the hospital with patients at all times to ensure high-quality care. Moreover, McCabe12 found that a lack of communication was a recurring theme related to staff being task-oriented leading to patients feeling frustrated and attributed nurses’ poor communications skills to the nurses being too busy. Given the challenging acute care environment, it is not surprising that building therapeutic interpersonal relationships is fundamental focus of current trends in patient care.29

The findings suggest that the act of developing therapeutic interpersonal relationships has the capacity to nurture and fortify relations between the clinician and the patient. Consequently, providing a supportive environment enhances clinician–patient engagement and communication. This is also echoed by Tabler et al30 who investigated patient care experiences and perceptions of clinician–patient relationships and concluded that communication underpins patients’ perception of interpersonal continuity. Fakhr-Movahedi et al31 also identified therapeutic interpersonal relationships as the essence of care and the development of trust as an enabler for patient engagement.

Literature on the health care environment in western countries has highlighted the awareness of the importance of developing therapeutic interpersonal relationships between the clinician and the patient.32 Morton et al33 suggest that implementation of nurse leader rounds has the capacity to increase patient satisfaction. Strategies such as rounds allow for real-time feedback concerning patients’ care and therefore allow coaching opportunities. Consequently, implementing education and training for the development of communication skills among health care professionals is linked to positive clinical outcomes,34 adherence to treatment, patient satisfaction,35 and positive therapeutic interpersonal relationships.2 Furthermore, those receiving personal coaching and training on the art of communication demonstrate vast improvements in patients’ perception of quality care activities.36

The findings highlight that cultural and therapeutic engagement influences interpersonal relationships. Increasing therapeutic engagement has been identified as a priority within health care.37 Consequently, therapeutic interpersonal relationships need to be recognized in clinical practice, education, and research.13 Cioffi,38 exploring culturally diverse patient experiences in the acute care setting, found the development of therapeutic interpersonal relationships difficult, and therefore nurses require greater capacity to develop a deeper consideration with educational support to enable effective and meaningful interactions. Within the acute care environment, however, increasing workloads, patient acuity, and a highly technological environment makes cultural engagement challenging.13 Given these challenges, humor was identified in the review of the literature as a means to enhance therapeutic interpersonal relationships. There is plentiful evidence to suggest the development of guidelines aimed to increase the cultural competence of clinicians, increases service utilization and promotes positive outcomes.39 Dowling40 identified how humor is an effective aspect of patients’ care experiences. Humor has been used to reduce tense circumstances,41 and so it has been suggested that the implementation of humor facilitates the development of clinician–patient therapeutic interpersonal relationships.42

The review has highlighted the lack of conceptual clarity and the confusion created by multiple terms used interchangeably when representing the same idea confounds a better understanding of the phenomenon under investigation here. Patient-centeredness is an equally diffuse and poorly circumscribed phenomenon, and this makes it difficult to measure the effect of strategies implemented to enhance such an ideal. Although there are clearly identified understandings of what a therapeutic encounter might embody, the literature is not easy to interpret and is at times conflicting in its reports of what and how nurses and other health professionals should enact such an encounter. Moreover, there appear to be a number of obstacles inherent in the way health care practice is able to be realized. These include ever-increasing complexity of the patients, a technologically sophisticated and demanding health care setting and health professional attitudes, and values about the nature of the work they are charged with doing.

Limitations and strength of evidence

This integrative review includes the use of a validated methodology15 and the use of three independent reviewers during data evaluation, data extraction, and synthesis. It is conceivable, however, that some papers may have been missed despite implementing a comprehensive and rigorous search strategy across key databases for published peer-reviewed literature.

Despite the geographical breadth captured in this review, the majority of papers included were from developed nations/regions including Denmark, the Netherlands, the UK, Australia, the USA, and Canada. Consequently, only one paper emanated from a developing region. Therefore, the themes and conclusion drawn upon is mainly representative of those from developed nations and may differ from those of the developing regions/countries. Furthermore, the primary clinical populations represented were physicians and nurses. Representation from other areas of health care including allied health is required for a holistic overview of therapeutic interpersonal relationships.

The review is limited to the adult population, and consequently experiences and strategies to enhance therapeutic interpersonal relationships concerning the pediatric and adolescent population are not represented. The definition of acute care for this review included medical, surgical, and mental health care, and it is acknowledged that these settings may have different communication styles and therapeutic patient-centered approaches, not captured in this review.

Conclusion

Therapeutic interpersonal relationships in health care within the acute care setting require clinicians to develop and sustain relationships that are geared toward best practice. The development of a therapeutic interpersonal relationship requires reflective practice and knowledge of how these influence relationships. Therefore, the process of therapeutic interpersonal relationships is critical to the basis of all practice having implications for cost burden and length of stay. It is through these therapeutic interpersonal relationships that health professionals can help the patient navigate their care.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Mottram A. Therapeutic relationships in day surgery: a grounded theory study. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(20):2830–2837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priebe S, McCabe R. The therapeutic relationship in psychiatric settings. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cousin G, Schmid Mast M, Roter DL, Hall JA. Concordance between physician communication style and patient attitudes predicts patient satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(2):193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Step MM, Rose JH, Albert JM, Cheruvu VK, Siminoff LA. Modeling patient-centered communication: oncologist relational communication and patient communication involvement in breast cancer adjuvant therapy decision-making. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(3):369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shay LA, Dumenci L, Siminoff LA, Flocke SA, Lafata JE. Factors associated with patient reports of positive physician relational communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolster D, Manias E. Person-centred interactions between nurses and patients during medication activities in an acute hospital setting: qualitative observation and interview study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(2):154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zandbelt LC, Smets EMA, Oort FJ, Godfried MH, de Haes HCJM. Medical specialists’ patient-centered communication and patient-reported outcomes. Med Care. 2007;45(4):330–339. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250482.07970.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross L. Facilitating rapport through real patient encounters in health care professional education. Australas J Paramed. 2014;10(4) [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connell E. Therapeutic relationships in critical care nursing: a reflection on practice. Nurs Crit Care. 2008;13(3):138–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2008.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster T, Hawkins J. The therapeutic relationship: dead or merely impeded by technology? Br J Nurs. 2005;14(13):698–702. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.13.18449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCabe C. Nurse-patient communication: an exploration of patients’ experiences. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(1):41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McQueen A. Nurse-patient relationships and partnership in hospital care. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9(5):723–731. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emeis C. Current resources for evidence based practice. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2012;57(2):196–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell CL. An overview of the integrative research review. Prog Transplant. (Aliso Viejo, Calif.) 2005;15(1):8–13. doi: 10.1177/152692480501500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torraco RJ. Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Hum Resource Dev Rev. 2005;4(3):356–367. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Sem Oncol Nurs. 2012;28(4):236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams AM, Irurita VF. Therapeutic and non-therapeutic interpersonal interactions: the patient’s perspective. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(7):806–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lees D, Procter N, Fassett D. Therapeutic engagement between consumers in suicidal crisis and mental health nurses. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2014;23(4):306–315. doi: 10.1111/inm.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones R, Regan M, Ristevski E, Breen S. Patients’ perception of communication with clinicians during screening and discussion of cancer supportive care needs. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):e209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell EA, McCance T. Nurse–patient encounters in the hospital ward, from the perspectives of older persons: an analysis using the Authentic Consciousness Framework. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(2):95–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jagosh J, Boudreau J, Steinert Y, MacDonald M, Ingram L. The importance of physician listening from the patients’ perspective: enhancing diagnosis, healing, and the doctor–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams K, Cimino JEW, Arnold RM, Anderson WG. Why should I talk about emotion? Communication patterns associated with physician discussion of patient expressions of negative emotion in hospital admission encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanghavi DM. What makes for a compassionate patient-caregiver relationship? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(5):283–292. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg M. Therapeutic play: developing humor in the nurse-patient relationship. J N Y State Nurses Assoc. 2003;34(1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nørgaard B, Kofoed P-E, Kyvik KO, Ammentorp J. Communication skills training for health care professionals improves the adult orthopaedic patient’s experience of quality of care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26(4):698–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shattell M. Eventually it’ll be over: the dialectic between confinement and freedom in the world of the hospitalized patient. In: Pollio HR, Thomas SP, editors. Listening to Patients: A Phenomenological Approach to Nursing Research and Practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. pp. 214–236. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shattell M. Nurse bait: Strategies hospitalized patients use to entice nurses within the context of the interpersonal relationship. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005;26(2):205–223. doi: 10.1080/01612840590901662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabler M, Scammon M, Debra L, et al. Patient care experiences and perceptions of the patient-provider relationship: a mixed method study. Patient Exper J. 2014;1(1):75–87. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fakhr Movahedi A, Salsali M, Negharandeh R, Rahnavard Z. A qualitative content analysis of nurse–patient communication in Iranian nursing. Int Nurs Rev. 2011;58(2):171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakken S, Holzemer WL, Brown M, et al. Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14(4):189–197. 189p. doi: 10.1089/108729100317795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morton J, Brekhus J, Reynolds M, Dykes A. Improving the patient experience through nurse leader rounds. Patient Exper J. 2014;1(2):53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chou CL, Cooley L, Pearlman E, White MK. Enhancing patient experience by training local trainers in fundamental communication skills. Patient Exper J. 2014;1(2):36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy M, Denise M, Fasolino M, John P, Gullen M, David J. Improving the patient experience through provider communication skills building. Patient Exper J. 2014;1(1):56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy D, Caselli R, Berry L. A roadmap for improving healthcare service quality. J Healthc Manag. 2011;56(6):385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cioffi J. Culturally diverse patient–nurse interactions on acute care wards. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12(6):319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tetley A, Jinks M, Huband N, Howells K. A systematic review of measures of therapeutic engagement in psychosocial and psychological treatment. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(9):927–941. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westerman T. Guest editorial: engagement of indigenous clients in mental health services: what role do cultural differences play? Australian e-journal for the Adv Ment Health. 2004;3(3):88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dowling M. The meaning of nurse–patient intimacy in oncology care settings: from the nurse and patient perspective. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(4):319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolton SC. Who cares? Offering emotion work as a ‘gift’in the nursing labour process. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(3):580–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savage J. Nursing Intimacy: An Ethnographic Approach to Nurse-patient Interaction. London, UK: Scutari Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]