Abstract

We report here the largest study to date of adult AML patients tested for measurable residual disease (MRD) at the time of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT). Seventy-two adult patients transplanted between 2004–2013 at a single academic medical center (UCSF) were eligible for this retrospective study based on availability of cryopreserved GCSF mobilized autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell (PBPC) leukapheresis specimens (“autografts”). Autograft MRD was assessed by molecular methods (RQ-PCR for WT1 alone or a multigene panel) and by multi-parameter flow cytometry (MPFC).

WT1 RQ-PCR testing of the autograft had low sensitivity for relapse prediction (14%) and a negative predictive value of 51%. MPFC failed to identify MRD in any of 34 autografts tested. Combinations of molecular MRD assays however improved prediction of post auto-HCT relapse. In multivariate analysis of clinical variables, including age, gender, race, cytogenetic risk category, and CD34+ cell dose, only autograft multigene MRD as assessed by RQ-PCR was statistically significantly associated with relapse. One year after transplantation only 28% patients with detectable autograft MRD were relapse free, compared with 67% in the MRD negative cohort. Multigene MRD, while an improvement on other methods tested, was however suboptimal for relapse prediction in unselected patients with specificity of 83% and sensitivity of 46%. In patients with known chromosomal abnormalities or mutations, however, better predictive value was observed with no relapses observed in MRD negative patients in the first year after auto-HCT compared with 83% incidence of relapse in the MRD positive patients (HR 12.45, p=0.0016).

In summary, increased personalization of MRD monitoring by use of a multigene panel improved the ability to risk stratify patients for post auto-HCT relapse. WT1 RQ-PCR and flow cytometric assessment for AML MRD in autograft samples had limited value for predicting relapse following auto-HCT. We demonstrate that cryopreserved autograft material presents unique challenges for AML MRD testing due to masking effects of previous GCSF exposure on gene expression and flow cytometry signatures. In the absence of information regarding diagnostic characteristics, sources other than GCSF-stimulated PBSC leukapheresis specimens should be considered as alternatives for MRD testing in AML patients undergoing auto-HCT.

Keywords: AML, Auto-HCT, MRD, Measurable Residual Disease

INTRODUCTION

The role of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains controversial(1–16). While commonly used in other hematological malignancies, auto-HCT has not been widely adopted in AML due to concerns regarding high post-transplant relapse rates. These relapses may be due, in part, to autograft contamination with AML. High sensitivity methods to detect residual AML following treatment are now available and have demonstrated the ability to identify those patients in morphological complete remission (CR) but at increased risk of relapse(17–28). Such minimal, or more correctly measurable(29), residual disease (MRD) assessments are increasingly recognized as an important factor in risk-adapted AML therapy and may be particularly important for predicting which patients achieve long-term disease-free survival after auto-HCT. Early trials evaluating the efficacy of auto-HCT as post-remission therapy in AML did not, however, include assessment of MRD(30–33).

Measurement of WT1 transcript levels using RQ-PCR is a common method for detecting MRD in AML. However, due to heterogeneous expression levels in AML, such testing only has utility for the subset of patients with sufficient leukemia associated WT1 overexpression(34). Messina and colleagues recently assessed WT1 levels in the leukapheresis product of GCSF stimulated peripheral blood (“autografts”) from 30 consecutive AML patients undergoing auto-HCT(35). They reported that those with higher levels of WT1 in the autograft (n=9) had, as a group, inferior relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to those with lower levels. The authors correctly noted that the size of the cohort was insufficient to provide a strong recommendation about post-remission consolidation strategy. It has recently been suggested that MRD status might be used to help select AML patients who may achieve long-term freedom from relapse using auto-HCT(4).

In this study we performed MRD analysis on the largest cohort of AML auto-HCT autograft samples (n=72) to date using not only WT1 but also multigene RQ-PCR testing, including WT1, MSLN, PRAME, PRTN3, CCNA1, t(8;21), inv(16), t(15;17), and mutated NPM1. The heterogeneity of AML makes a multi-target approach for MRD attractive; we recently showed that a multigene panel for MRD assessment significantly improved sensitivity to predict relapse compared with using WT1 expression alone in patients undergoing allogeneic HCT (Allo-HCT) at the NIH(19). In addition, as there is no consensus as to the superiority of PCR-based or multi-parameter flow cytometry (MPFC)-based MRD detection, we evaluated a subset of these autografts via both MPFC and RQ-PCR.

METHODS

Autologous HCT

All patients age ≥18 with AML who underwent auto-HCT at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center between June 1988 and July 2013 with cryopreserved autologous stem cell aliquots were considered eligible for this study. All samples were collected on IRB approved research protocols. Disease classification was determined by the refined Medical Research Council cytogenetic classification system(36). Patients received peripheral blood progenitor cell (PBPC) grafts and underwent an in vivo purge as part of stem cell mobilization and collection which included IV cytarabine 16g/m2 cumulative dose and IV etoposide 40mg/kg cumulative dose over 4 days, as described previously(37, 38). The target CD34-positive hematopoietic progenitor cell dose was 5–10×106/kg, with a minimum dose of 2×106/kg required to proceed to auto-HCT. The preparative regimen consisted of busulfan 0.8mg/kg IV for 16 doses over 4 days, as well as a single dose of etoposide 60mg/kg IV given 3 days prior to stem cell infusion. Patients were treated with auto-HCT initially as part of an institutional research protocol and then as standard institutional practice starting in the early 2000s with the majority of patients receiving auto-HCT due to lack of an appropriate Allo-HCT donor. Five of the 72 patients were treated on cooperative group research studies (CALGB 10503 and CALGB 19808). Nine patients received targeted, dose-escalated busulfan on an institutional research protocol(39, 40).

MRD detection by MPFC

Flow cytometry was performed at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC). Immunophenotypic data from initial disease presentation was not available therefore attempts to detect MRD were made by identification of populations showing deviation from the normal patterns of antigen expression seen on specific cell lineages at specific stages of maturation as compared with either normal or regenerating marrow. When identified, the abnormal population was quantified as a percentage of the total CD45+ white cell events. MRD was assessed on cryopreserved autograft PBPC aliquots with up to 1 million events per tube acquired on an LSRII (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

MRD detection by RQ-PCR

RQ-PCR was performed at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). RNA was isolated from up to 10 million cells using the Qiagen Allprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quantity and integrity was assessed using a Nanodrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE, USA) and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Santa Clara, CA, USA). The RT2 Firststrand kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used for gDNA elimination and cDNA synthesis from 1µg of total RNA.

Previously validated assays for WT1(34), NPM1 mutations (type A, B, D)(22), and chromosomal translocations t(8;21) inv(16) and t(15;17)(41) were utilized and thermocycled in a RotorgeneQ thermocycler (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Cycling conditions described in detail elsewhere (see Supplemental Methods) were used with 100ng RNA equivalent cDNA in a 25µL reaction volume using Taqman universal mastermix(22, 34, 41). Overexpression of AML associated gene transcripts in the multigene MRD array were measured using custom-built RQ-PCR arrays as previously reported(19) with SYBR Green Mastermix (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and an ABI7900 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Further details on methods and analysis can be found in the Supplemental Methods.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Outcomes

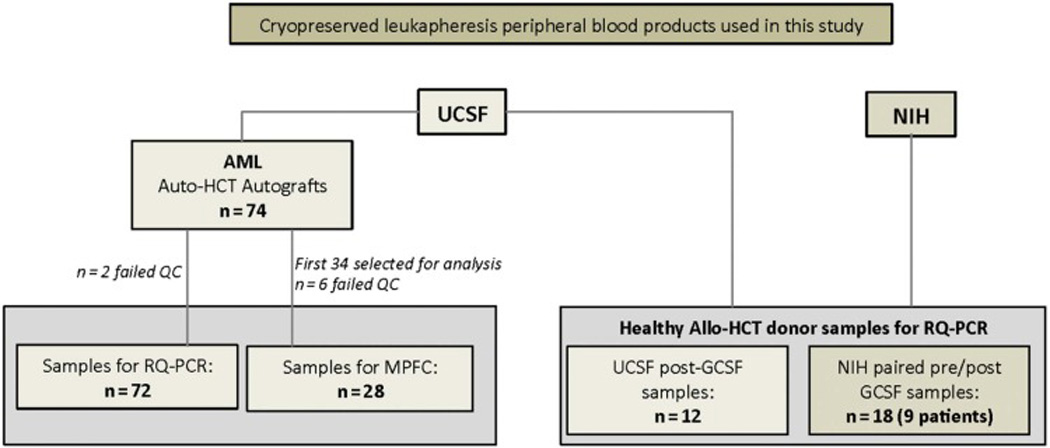

Of 334 consecutive adult AML patients who underwent auto-HCT for AML at UCSF between June 1988 and July 2013, 72 (22%) were eligible for this study based on availability of viably cryopreserved PBPC aliquots. An additional two samples were identified but rejected due to insufficient RNA quality (Figure 1). Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 48 (24–69) and 99% were in complete remission at the time of transplantation.

Figure 1. Cryopreserved leukapheresis peripheral blood products used in this study.

All samples were collected on IRB approved research protocols. Left) 74 autograft samples sent to NHLBI from UCSF, from AML patients who underwent auto-HCT at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center between June 1988 and July 2013. Two samples did not meet QC criterion set by ABL1 housekeeping gene copy number values and were rejected. The remaining 72 samples (See Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1) were used for RQ-PCR analysis at the NIH. The first 34 samples from this the RQ-PCR cohort were also analyzed at the FHCRC using multiparameter flow cytometry. Six of these 34 samples were judged insufficient quality for full analysis. Right) In addition, GCSF mobilized leukapheresis peripheral blood stem cell products from healthy donor samples (collected for Allo-HCT) were used as controls in this study. Twelve healthy donor samples (post GCSF) were sent from UCSF to NIH for evaluation. To study the effect of GCSF on peripheral blood cell composition in healthy individuals, paired cryopreserved leukapheresis samples from before and after GCSF stimulation where obtained from nine patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Cohort |

|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | 72 (100) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 33 (46) |

| Age at autoHCT, years | 48 (24–69) |

| Cytogenetic risk classification | |

| Favorable | 17 (24) |

| Intermediate | 47 (65) |

| Poor/Secondary | 4 (5) |

| Unknown | 4 (5) |

| Remission status at autoHCT | |

| CR1, n (%) | 64 (89) |

| CR2, n (%) | 6 (8) |

| CR3, n (%) | 1 (1) |

| PIF, n (%) | 1 (1) |

| CD34+ cell dose ×106/kg | |

| <5, n (%) | 8 (11) |

| ≥5–10, n (%) | 29 (40) |

| ≥10, n (%) | 27 (38) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 8 (11) |

| Treatment era | |

| Pre-2005, n (%) | 6 (8) |

| 2005–2009, n (%) | 42 (58) |

| 2010–2013, n (%) | 24 (33) |

| Length of post-autoHCT follow-up, years | 2.6 (0.3–10) |

AutoHCT = Autologous hematopoietic cell transplant; CR1 = First complete remission; CR2 = Second complete remission; CR3 = Third complete remission; PIF = Primary induction failure

Relapse free survival (RFS) at one year following auto-HCT was 50% with 31 of 37 observed relapses occurring in the first year following transplantation. Three and five year overall survival (OS) rates were 66% and 56% respectively. These outcomes are representative of the overall clinical experience at this center. The majority of patients in this cohort (65%) had intermediate cytogenetic risk, of whom 54% remained alive and 39% remained relapse-free at five years post transplant. These outcomes compare well with the 59% alive and 43% relapse-free outcomes recently reported for all 113 intermediate-risk AML patients transplanted with auto-HCT between 1998–2013 at this center(8).

For additional clinical information see Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 1.

Auto-HCT relapse is poorly predicted by WT1 in leukapheresis PBPC autograft

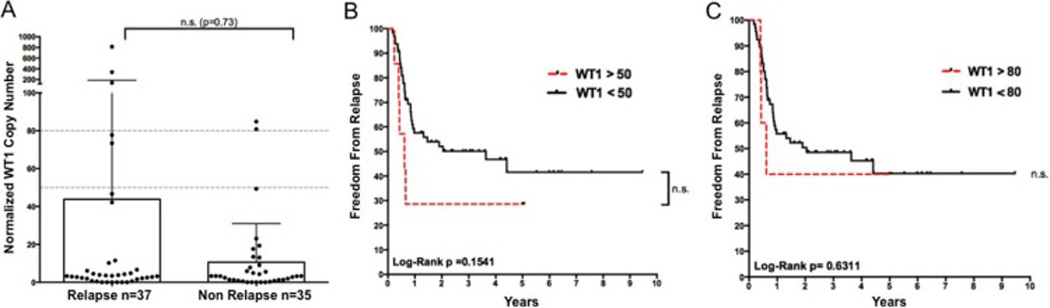

It has previously been reported that WT1 transcript detection in autograft samples could predict post-transplantation relapse in patients undergoing auto-HCT(35). Using the same assay(34, 35) on all 72 autograft samples, we found WT1 levels were not significantly greater in patients who relapsed (Figure 2A) or in those who relapsed within the first year (p=0.26, data not shown). WT1 MRD positivity defined either by using the established threshold described by Cilloni et. al.(34) (Figure 2B) or by the modified threshold used by Messina et. al.(35) (Figure 2C) failed to significantly discriminate patients for relapse risk following auto-HCT. WT1 transcript as a single MRD marker was a poor predictor of relapse within one year after (Sensitivity: 16%, Specificity: 95%, PPV 71%: NPV: 60%) or any time after auto-HCT (Sensitivity: 14%, Specificity: 94%, PPV 71%: NPV: 51%).

Figure 2. WT1 RQ-PCR of Autograft is not sufficient for MRD detection in auto-HCT.

A) WT1 copy number in patients experiencing relapse following auto-HCT did not differ significantly from those who did not relapse during this period (p=0.73 Mann Whitney test). Two non-relapsing patients (patients 8 and 45) experienced relapse-free survival greater than five years following transplantation despite high levels of autograft WT1 transcript. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of relapse vs. MRD status as assigned by WT1 copy number above B) the standard ELN threshold (50 WT1 copies/104 ABL1) and C) the threshold used by Messina et. al. (80 WT1 copies/104 ABL1).

Autologous transplant samples have WT1 and PRTN3 gene expression signatures suboptimal for MRD determination

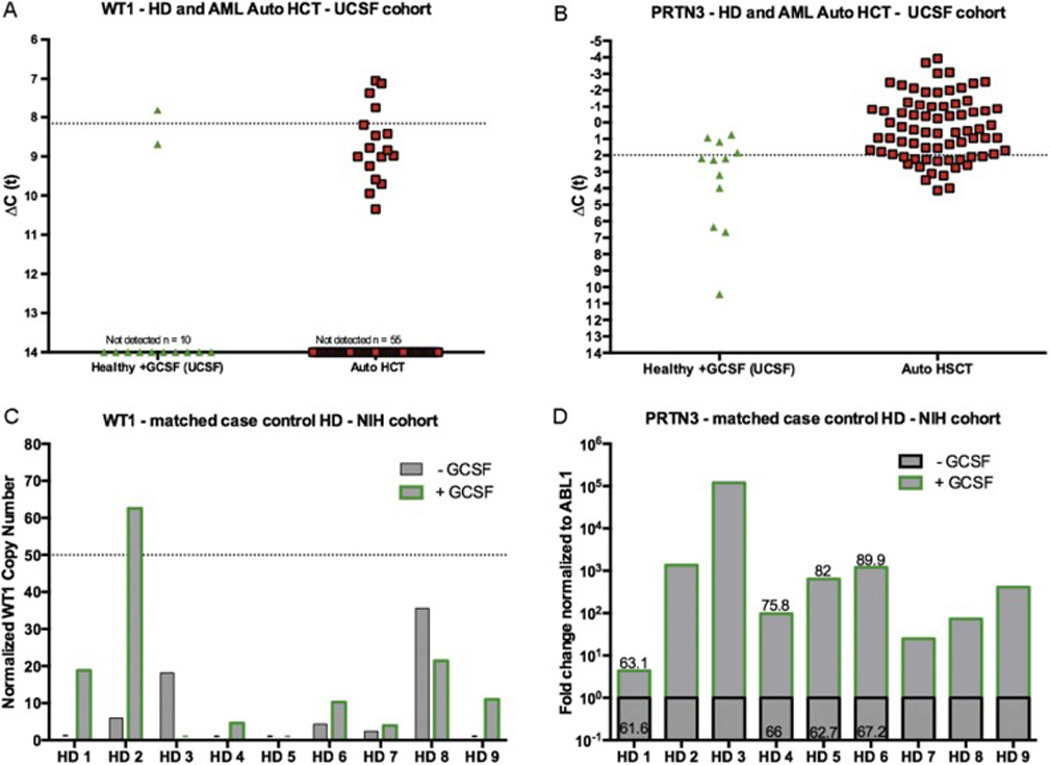

We previously reported multigene MRD detection using expression of WT1, CCNA1, MSLN, PRAME and PRTN3 in the context of AML patients receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (Allo-HCT) improved relapse risk prediction compared to the use of WT1 RQ-PCR alone. This work used thresholds based on gene expression in leukapheresis products (LP) from a cohort of 50 unmanipulated healthy donors(19). As autograft samples in the current study were from patients who had received a course of GCSF immediately prior to collection, we performed additional testing to confirm that previously established thresholds remained appropriate. Twelve healthy donor PBPC LP samples collected after GCSF administration from UCSF were tested using the multigene panel. Of note, 2 of 12 GCSF mobilized PBPC LP from healthy donors had WT1 levels above the 98th percentile seen for healthy donors in the prior study, with one healthy donor being found to have WT1 expression that would have been falsely described as AML MRD (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. GCSF treatment results in “MRD positive” levels of elevated gene expression in healthy donors.

Analysis on healthy donor (HD) allo-HCT and AML auto-HCT samples from UCSF: A) WT1 and B) PRTN3 mRNA expression found in 12 healthy allo-HCT donors post GCSF administration treated at UCSF (grey triangle), and post-chemomobilization GCSF stimulated PBPC AML patient autograft samples (red and black square). The dotted line indicates the previously calculated MRD positive threshold established using non-GCSF stimulated healthy leukapheresis samples as a baseline. Expression is normalized to expression of the ABL1 control gene. A ΔCt value of 14 indicates gene expression levels below the limit of detection of the assay (Ct >35). Analysis on paired samples from NIH healthy donors pre and post GCSF: C) WT1 mRNA measured with the ELN Ipsogen WT1 Profile Quant kit reveals reveals increased WT1 levels following GCSF administration including in one healthy donor above the validated ELN WT1 MRD threshold (50 copies/1×104 copies ABL). D) Multigene Array RQ-PCR normalized fold change expression of PRTN3 relative to baseline in match case control healthy donors pre and post GCSF shows increased expression following GCSF stimulation. Correlation with absolute neutrophil counts in match case control samples is shown as the % neutrophil count on the bar from available complete blood count data.

PRTN3 expression in autograft materials was not a useful marker of AML MRD. A third of GCSF mobilized healthy donors and 80% of patients on this study would have been considered MRD positive using our previously established threshold (Figure 3B). CCNA1 was also not useful for autograft AML MRD, with no patient showing expression above the level seen in healthy donors after GCSF (Supplemental Figure 3).

G-CSF mobilization enriches transcripts from leukemia-associated biomarkers WT1 and PRTN3 in matched case control healthy donors

To determine the impact of GCSF on gene expression based AML MRD RQ-PCR we tested paired peripheral blood leukapheresis samples from healthy donors at the NIH taken prior to and immediately after GCSF administration. WT1 levels assessed with the ELN assay(34) increased following GCSF in more than half of cases (Figure 3C). One healthy donor with initially undetectable WT1 had transcript enrichment to a level consistent with AML MRD following GCSF. Increased PRTN3 expression was also seen after GCSF stimulation, and was associated with increased neutrophil percentage in peripheral blood (Figure 3D) and CD34 dose. These findings highlight the difficulty in distinguishing residual leukemic clones from normal hematopoietic cells in the GCSF-mobilized auto-HCT graft.

Somatic mutation detection improves prediction of relapse in auto-HCT

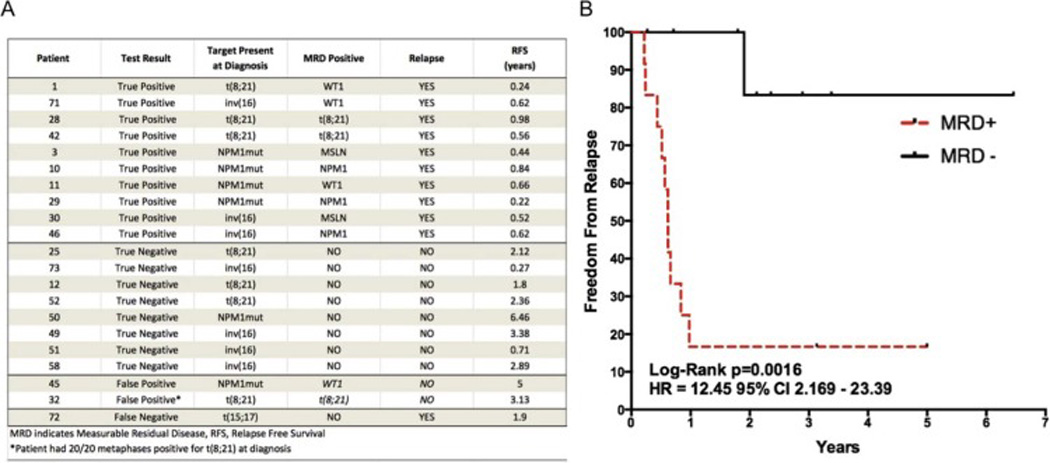

Given observed differences in WT1 and PRTN3 gene expression after GCSF stimulation, we next assayed leukemia-specific targets in the form of recurrent somatic mutations and chromosomal translocations in all patients. In total, 21 these patients had known leukemia specific mutations at diagnosis that were amenable to detection using previously validated RQ-PCR assays (Figure 4A)(22, 41). Of 7 patients with translocation (8;21) at diagnosis, 3 were found to have t(8;21) transcript in the autograft, of whom 2 relapsed within the first year post-transplant. Six patients had a known NPM1 mutation at diagnosis, which was detected in 2 patients who relapsed after 2.5 and 10 months respectively. A patient of unknown NPM1 status, screened for somatic mutations because of Inv(16) AML diagnosis, was also positive for NPM1 mutation autograft MRD and relapsed 7.5 months after transplant. Inv(16) (n=7) and PML-RARA (n=1) were not detected in any graft samples. Together, when 21 patients harboring a known mutation or chromosomal abnormality amenable to detection with RQ-PCR were screened for these mutations and gene expression biomarkers, MRD positivity effectively enriched a group of patients at high risk of relapse. In the first year, no MRD negative patients in this group relapsed whereas 84% of MRD positive patients relapsed, HR=12.45 Log-Rank p=0.0016 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Personalization of MRD monitoring allows for improved relapse risk stratification.

A) MRD analysis of the 21 cases in which diagnostic information on known somatic mutations amenable to RQ-PCR detection (NPM1 mutation, chromosomal translocations inv(16), t(8;21), or t(15;17)) was available. Samples are listed sorted by test result with the third column showing the target detected at diagnosis and the fourth column showing the marker for which the patient was MRD positive. B) Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of the 21 patients with a known mutation at diagnosis demonstrate significant survival benefits for multigene MRD negativity Log-Rank p=0.0016 HR=12.45. One case of early non-relapse mortality (51) was included in all analyses with censoring at time of death.

Predictors of Relapse after auto-HCT

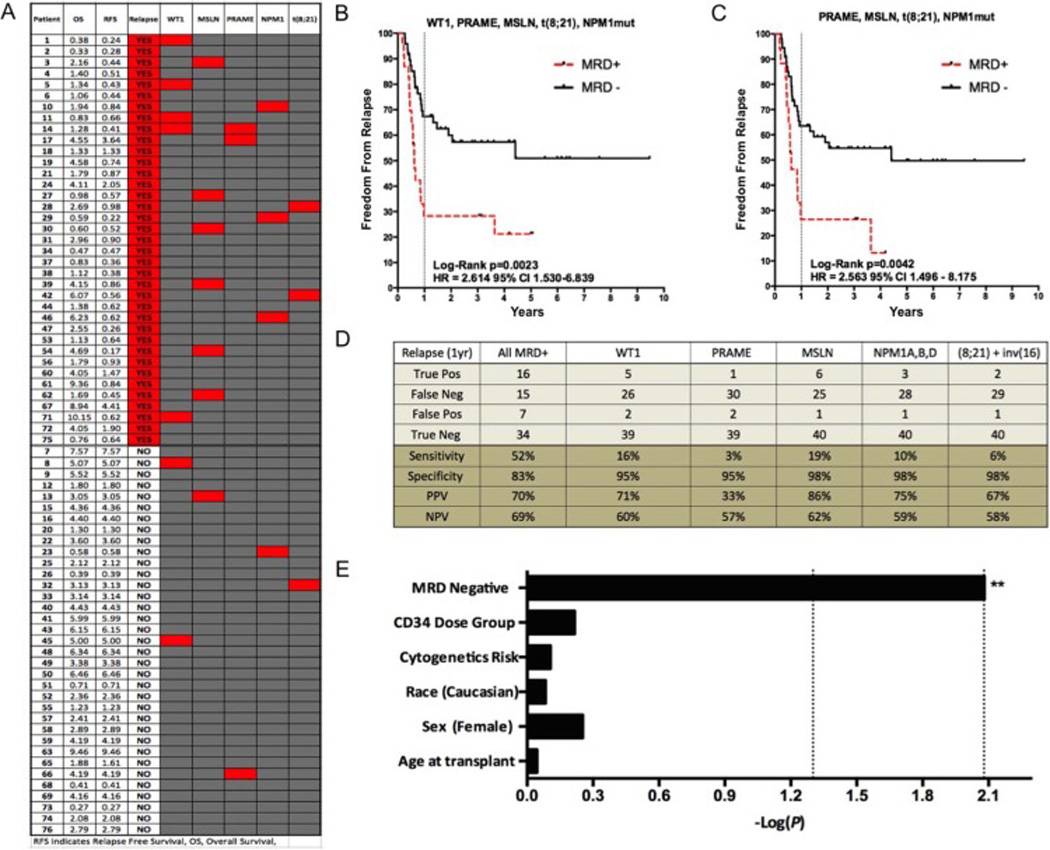

MRD detected with gene expression tests not affected by GCSF exposure, together with somatic mutation detection was highly complementary in nature when used in the full cohort (Figure 5). Only one patient was “double positive” for any of the MRD markers tested (patient 14). Using multigene detection on autograft samples with WT1, PRAME, MSLN, inv(16), t(8;21), and mutated NPM1 tests, we detected MRD in 16 patients who relapsed within the first year post auto-HCT and in an additional patient who relapsed after one year. Autograft MRD positivity significantly enriched for a group of patients at risk of early post-transplant relapse. One year after transplant only 28% of MRD positive patients had not relapsed compared with 67% in the MRD negative cohort (Figure 5B). Of 31 patients relapsing within one year of auto-HCT multigene MRD was detectable in the autograft of 16 (Sensitivity: 52%, Specificity: 83%, PPV 70%: NPV: 69%, see Figure 5D). In contrast, and consistent with our previous findings in Allo-SCT(19), MRD at the time of transplant was poorly predictive of late relapse (only 1 of 6 had a MRD positive autograft) resulting in marginally inferior ability to predict relapse at any time after auto-HCT (Sensitivity: 46%, Specificity: 83%, PPV 74%: NPV: 59%). Use of multigene MRD without the use of WT1 allowed similar stratification between cohorts (Figure 5C), but with fewer patients correctly classified in the MRD positive group (sensitivity 39% for 1 year post-transplant relapses).

Figure 5. Multigene MRD allows enrichment of AML patients with high risk of post Auto-HCT relapse.

A) Comparison between post auto-HCT relapse and detectable MRD in the autograft shows lack of redundancy between tests in the multigene panel. Red shaded squares signify “MRD” positive for the corresponding test (column). B) Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for patients with residual disease detected with WT1, PRAME, MSLN, NPM1mut (types A, B and D) and t(8;21). MRD positivity was associated with decreased freedom from survival, Log-Rank P=0.0023; HR, 2.614 [95% CI 1.530–6.839] C) If WT1 is removed from this analysis, patients are still effectively risk stratified but at the expense of fewer relapsing patients (n=13 vs. n=17) being correctly assigned to the high risk MRD positive group Log-Rank P=0.0042; HR, 2.563 [95% CI 1.496 – 8.175]. Two cases of early non-relapse mortality (23, 51) were included in all analyses with censoring at time of death. D) Statistical performance characteristics of each MRD assay reveals minimal efficacy for each test used on the entire cohort individually but complementarity when used in tandem (sensitivity 52%, specificity 83% for 1 year post auto-HCT relapse when all markers used to detect MRD in autograft). E) Multivariate maximum likelihood estimate reveals MRD negativity as only significant variable associated with post AutoHCT relapse (protective factor) in a multivariate analysis of cytogenetic risk group, CD34 dose, age at time of transplant, sex, and race. The first and second dotted lines represent significance at the 0.05 and 0.0083 (Bonferroni corrected) levels respectively. MRD negativity was protective from relapse (HR 0.349 CI 0.160–0.763). CD34 dose (HR 1.157 CI 0.662–2.020), cytogenetic risk group (HR 0.907 CI 0.455–1.810), race (HR 0.909 CI 0.389–2.122), sex (HR 1.273 CI 0.606–2.524) and age at transplant (HR 1.002 CI 0.973–1.031) were not predictive of relapse.

In a multivariate analysis with variables including sex, race, age at transplant, cytogenetic risk category, CD34-postive cell dose, and MRD status, the only significant predictor of freedom from relapse after auto-HCT was the absence of MRD in the autograft (Figure 5E).

Leukemia immunophenotype is indistinguishable from healthy cells in the autograft

Finally, replicate autograft aliquot samples from the first 34 patients on this study were also sent to FHCRC for MPFC analysis. In total, 20 of these patients experienced relapse post-auto-HCT (59%) with most occurring in the first year after transplantation (17/20). Multiparameter flow cytometry was performed in a laboratory with significant experience according to protocols previously described(42). The majority of frozen samples (82%) were evaluable by MPFC and consisted of a mixture of lymphocytes, mature monocytes and few plasmacytoid dendritic cells with a variable number of CD34-positive progenitors having a stem cell-like immunophenotype (bright CD34+, low to absent CD38) without maturation to lineage committed forms. Findings were typical of leukapheresis stem cell products of this type (Supplemental Figure 2). The median percentage of CD34 positive cells among PBPC mononuclear cells was 0.42% (range 0.05 – 12.5). The findings across the all samples were similar overall and no specimen contained definitive evidence of immunophenotypic MRD. The combination of regenerative or induced antigenic changes that overlap with leukemic immunophenotypes, limited internal control populations to judge relative intensity changes and variable sample quality were considered likely to account for these false negative results.

Discussion

For three decades there has been debate regarding the possibility that leukemic contamination of autologous stem cell grafts could contribute to the high post-transplant relapse rates observed in AML patients(43–45). The advent of highly sensitive methods for detection of measurable residual disease made this hypothesis testable. Early reports were limited by small cohort size (n=7, n=24) but showed non-significant trends for patients relapsing after transplant to have had higher WT1 levels in the autograft but with considerable overlap between the ranges observed in relapsing and non-relapsing patients (46, 47). A recent well-performed study on 30 AML patients undergoing auto-HCT reported that the median WT1 transcript level in the autograft of relapsing patients was significantly higher than those who did not relapse(35). Again however the median WT1 value of those relapsing (82 copies/104 ABL) was within the range observed of those not relapsing (4–109 copies/104 ABL) making the benefit of such testing to any individual patient questionable.

Our study represents a larger patient cohort than all three of these previous studies combined and shows no statistically significant difference between autograft WT1 transcript levels in patients who relapsed or did not relapse after auto-HCT. While we observed a non-significant trend for WT1 levels in the autograft to be, on average, higher in those patients who relapsed there was considerable overlap between the ranges observed. Seven patients in our study had WT1 levels above the ELN threshold(34), five of whom relapsed within one year (sensitivity: 16%, specificity: 95%). The differences in the performance of WT1 as a MRD assay in auto-HCT between our study and previous work are likely due to stochastic factors associated with differences in sample size. In addition to sample size effects, differences in numbers of cycles of consolidation chemotherapy and the use of in vivo purging in this cohort may have also decreased detectable WT1 expression levels in our study. False positive results were seen however in both the recent study by Messina and colleagues(35) and our study, using WT1 level of >50 copies/104 ABL threshold established by the ELN(34), two of 12 WT1 positive patients were false positives in that study (17%) as were two of seven WT1 positive patients in our study (29%).

The poor performance of traditional AML MRD methodologies, with proven utility in the conventional Allo-HCT setting, was likely due to the unique circumstance of the effects of GCSF mobilization in these auto-HCT patients. By assessing transcript levels in a cohort of nine NIH healthy donors before and after GCSF administration we show that WT1 transcripts can increase in the peripheral blood leukapheresis product following GCSF in even healthy subjects to a level compatible with AML MRD, thus potentially leading to false positive results. Similarly, the inability of MPFC to detect AML MRD was likely multifactorial but was due in part to the altered cell composition in the autograft in patients who had received GCSF. The use of a multigene panel of molecular markers not influenced by GCSF expression mitigated some of the weaknesses of using WT1 testing alone on autografts to predict relapse risk.

This study has limitations. Despite the fact that in this study 97% of samples had sufficient RNA integrity to be used for RQ-PCR testing, cryopreserved autograft material may not represent an ideal source for AML MRD testing for other reasons. In addition to effects of GCSF on RQ-PCR and MPFC signatures, it is not clear that an aliquot of the autograft is a fully representative sample of the total AML burden of a patient undergoing auto-HCT. Inadequate sampling rather than insufficient sensitivity of MRD testing may be the most important factor in detection of low levels of residual AML(48). MRD assessment of the bone marrow of these patients would have likely provided important additional information but unfortunately was not possible in this historical cohort. Unlike previous studies(49–53), we did not observe an association between CD34+ cell dose and post auto-HCT relapse risk. Our study may have been insufficiently powered to detect this effect, though we did observe a trend in univariate analysis for lower rates of freedom from relapse in those receiving CD34+ doses greater than 10 million per kilogram.

We also observed several false positive events when using a multigene testing approach. The positive predictive value for multigene MRD in predicting 1 year post auto-HCT relapse was 70% with seven false positive events. In addition to the two false positive WT1 tests described above, one patient with detectable NPM1 mutation had not relapsed at the time of follow-up at only 7 months and so was assigned as a “false positive”, which unfortunately may be a premature classification given the other three patients with NPM1 mutation positive MRD ultimately all relapsed within a year of auto-HCT. A fourth “false positive” patient had detectable t(8,21) in the autograft but did not relapse despite over three years of follow-up (Figure 5, patient 32). Bone marrow cytogenetics for this patient at diagnosis showed 20 out of 20 metaphases with a 45,X,-X,t(8;21)(q22;q22) karotype, suggesting the t(8;21) anomaly may have been present in the majority of bone marrow cells and not just the leukemic clone, suggesting presence of pre-leukemic clonal hematopoiesis. Such persistence after therapy has been described previously(54, 55). Finally, two positives were observed for PRAME in patients who did not relapse with one year (one of whom did relapse, but after 1 year) and one for MSLN. Finally, MRD analysis by flow cytometry found no interpretable signature in the first 34 autograft samples examined. It is likely that leukemia associated immunophenotype (LAIP) information from initial diagnosis would have improved the performance of MPFC.

While the detection of residual disease in the autograft product prior to transplantation to reduce relapse risk is a logical and highly appealing strategy(4, 35, 46, 47, 56) unfortunately the autograft, due to changes in peripheral blood composition following GCSF stimulation, is not optimal for AML MRD detection using gene expression RQ-PCR or multiparameter flow cytometry based methods. In summary we show here that testing of autograft samples using WT1 RQ-PCR alone is insufficient for optimal stratification for post-transplant relapse risk. Second, we show a mechanism for the observed overlapping ranges for WT1 levels in the auto-HCT setting due to effects of GCSF increasing baseline WT1 expression levels. The use of a multigene MRD panel mitigates some of these deficiencies and could identify a high-risk group of patients with only 28% chance of remaining in remission one year after auto-HCT. Finally, the proof of principle demonstration that patients could be highly effectively stratified into groups with high and low risks of relapse after Auto-HCT when a known mutation target was available for tracking was remarkable. Given the intrinsic heterogeneity of AML, such personalization may represent the future for MRD monitoring in this disease(57–59) and should be validated with additional studies. Ultimately, however, only randomized trials of transplant vs. non-transplant therapy in cohorts selected based on MRD status will clarify if such testing can identify AML patients who may benefit from auto-HCT(60). We show that GCSF-stimulated PBSC leukapheresis specimens have limitations for use in the detection of MRD and prediction of relapse risk following auto-HCT. Evaluation of alternative sample sources other than autografts for MRD testing, and/or novel technologies for detecting residual disease, in AML patients undergoing auto-HCT appears warranted.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Largest study to date of MRD in auto-HCT for AML

Autograft is suboptimal source for AML MRD detection

GCSF administration can lead to false positive WT1 MRD values

MRD detection by flow cytometry in post-GCSF autografts is challenging without LAIP

RQ-PCR for somatic mutations and translocations can improve autograft MRD detection.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and by NIH grant R01 CA 175008-01A1.

The authors thank Nancy Hensel, Minoo Battiwalla and John Barrett for the gift of healthy donor leukapheresis samples from healthy donors before and after GCSF, and Jingrong Tang and Meghali Goswami for technical advice and assistance (all NHLBI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT-OF-INTEREST DISCLOSURE

Authors report no relevant conflict of interest.

Presented, in part, at the 57th American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting & Exposition; December 5–8, 2015; Orlando, FL.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Supplementary information is available at BBMT's website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seshadri T, Keating A. Is there a role for autotransplants in AML in first remission? Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novitzky N, Thomas V, du Toit C, McDonald A. Is there a role for autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with acute myelogenous leukemia? A retrospective analysis. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17:875–884. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornelissen JJ, Blaise D. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with AML in first complete remission. Blood. 2016;127:62–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-604546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorin NC, Giebel S, Labopin M, Savani BN, Mohty M, Nagler A. Autologous stem cell transplantation for adult acute leukemia in 2015: time to rethink? Present status and future prospects. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50:1495–1502. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majhail NS, Farnia SH, Carpenter PA, et al. Indications for Autologous and Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Guidelines from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015;21:1863–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czerw T, Labopin M, Gorin NC, et al. Use of G-CSF to hasten neutrophil recovery after auto-SCT for AML is not associated with increased relapse incidence: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the EBMT. Bone marrow transplantation. 2014;49:950–954. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorin NC, Labopin M, Piemontese S, et al. T-cell-replete haploidentical transplantation versus autologous stem cell transplantation in adult acute leukemia: a matched pair analysis. Haematologica. 2015;100:558–564. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.111450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mannis GN, Martin TG, 3rd, Damon LE, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia treated with autologous hematopoietic cell transplant in first complete remission. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1088646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lashkari A, Lowe T, Collisson E, et al. Long-term outcome of autologous transplantation of peripheral blood progenitor cells as postremission management of patients > or =60 years with acute myelogenous leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagler A, Labopin M, Gorin NC, et al. Intravenous busulfan for autologous stem cell transplantation in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a survey of 952 patients on behalf of the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2014;99:1380–1386. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.105197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfirrmann M, Ehninger G, Thiede C, et al. Prediction of post-remission survival in acute myeloid leukaemia: a post-hoc analysis of the AML96 trial. The lancet oncology. 2012;13:207–214. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiPersio JF, Ho AD, Hanrahan J, Hsu FJ, Fruehauf S. Relevance and clinical implications of tumor cell mobilization in the autologous transplant setting. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung AS, Holman PR, Castro JE, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as an intensive consolidation therapy for adult patients in remission from acute myelogenous leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15:1306–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tallman MS, Perez WS, Lazarus HM, et al. Pretransplantation consolidation chemotherapy decreases leukemia relapse after autologous blood and bone marrow transplants for acute myelogenous leukemia in first remission. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:204–216. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornelissen JJ, Versluis J, Passweg JR, et al. Comparative therapeutic value of post-remission approaches in patients with acute myeloid leukemia aged 40–60 years. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2015;29:1041–1050. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vellenga E, van Putten W, Ossenkoppele GJ, et al. Autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:6037–6042. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-370247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araki D, Wood BL, Othus M, et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Time to Move Toward a Minimal Residual Disease-Based Definition of Complete Remission? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buccisano F, Maurillo L, Spagnoli A, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular diagnostic characterization combined to postconsolidation minimal residual disease assessment by flow cytometry improves risk stratification in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:2295–2303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goswami M, McGowan KS, Lu K, et al. A multigene array for measurable residual disease detection in AML patients undergoing SCT. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50:642–651. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hokland P, Ommen HB, Mule MP, Hourigan CS. Advancing the Minimal Residual Disease Concept in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2015;52:184–192. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hourigan CS, Karp JE. Minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2013;10:460–471. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kronke J, Schlenk RF, Jensen KO, et al. Monitoring of minimal residual disease in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the German-Austrian acute myeloid leukemia study group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2709–2716. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pigazzi M, Manara E, Buldini B, et al. Minimal residual disease monitored after induction therapy by RQ-PCR can contribute to tailor treatment of patients with t(8;21) RUNX1-RUNX1T1 rearrangement. Haematologica. 2015;100:e99–e101. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.114579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubnitz JE, Inaba H, Dahl G, et al. Minimal residual disease-directed therapy for childhood acute myeloid leukaemia: results of the AML02 multicentre trial. The lancet oncology. 2010;11:543–552. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walter RB, Gyurkocza B, Storer BE, et al. Comparison of minimal residual disease as outcome predictor for AML patients in first complete remission undergoing myeloablative or nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2014 doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu HH, Zhang XH, Qin YZ, et al. MRD-directed risk stratification treatment may improve outcomes of t(8;21) AML in the first complete remission: results from the AML05 multicenter trial. Blood. 2013;121:4056–4062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-468348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terwijn M, van Putten WL, Kelder A, et al. High prognostic impact of flow cytometric minimal residual disease detection in acute myeloid leukemia: data from the HOVON/SAKK AML 42A study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:3889–3897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hourigan CS, Goswami M, Battiwalla M, et al. When the Minimal Becomes Measurable. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:2557–2558. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.6395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman JM, Gale RP. What does MRD in leukemia really mean? Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2014;28:1131. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breems DA, Boogaerts MA, Dekker AW, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as consolidation therapy in the treatment of adult patients under 60 years with acute myeloid leukaemia in first complete remission: a prospective randomized Dutch-Belgian Haemato-Oncology Co-operative Group (HOVON) and Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) trial. British journal of haematology. 2005;128:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cassileth PA, Harrington DP, Appelbaum FR, et al. Chemotherapy compared with autologous or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in the management of acute myeloid leukemia in first remission. The New England journal of medicine. 1998;339:1649–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812033392301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harousseau JL, Cahn JY, Pignon B, et al. Comparison of autologous bone marrow transplantation and intensive chemotherapy as postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia. The Groupe Ouest Est Leucemies Aigues Myeloblastiques (GOELAM) Blood. 1997;90:2978–2986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zittoun RA, Mandelli F, Willemze R, et al. Autologous or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation compared with intensive chemotherapy in acute myelogenous leukemia. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) Leukemia Cooperative Groups. The New England journal of medicine. 1995;332:217–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cilloni D, Renneville A, Hermitte F, et al. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction detection of minimal residual disease by standardized WT1 assay to enhance risk stratification in acute myeloid leukemia: a European LeukemiaNet study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:5195–5201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Messina C, Candoni A, Carrabba MG, et al. Wilms' tumor gene 1 transcript levels in leukapheresis of peripheral blood hematopoietic cells predict relapse risk in patients autografted for acute myeloid leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:1586–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV, et al. Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood. 2010;116:354–365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borrello IM, Levitsky HI, Stock W, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-secreting cellular immunotherapy in combination with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) as postremission therapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2009;114:1736–1745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mannis GN, Logan AC, Leavitt AD, et al. Delayed hematopoietic recovery after auto-SCT in patients receiving arsenic trioxide-based therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia: a multi-center analysis. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50:40–44. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beumer JH, Owzar K, Lewis LD, et al. Effect of age on the pharmacokinetics of busulfan in patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation; an alliance study (CALGB 10503, 19808, and 100103) Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2014;74:927–938. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2571-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mannis GN, Andreadis C, Logan AC, et al. A phase I study of targeted, dose-escalated intravenous busulfan in combination with etoposide as myeloablative therapy for autologous stem cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia. Clinical lymphoma, myeloma & leukemia. 2015;15:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gabert J, Beillard E, van der Velden VH, et al. Standardization and quality control studies of 'real-time' quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of fusion gene transcripts for residual disease detection in leukemia - a Europe Against Cancer program. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2003;17:2318–2357. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walter RB, Buckley SA, Pagel JM, et al. Significance of minimal residual disease before myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for AML in first and second complete remission. Blood. 2013;122:1813–1821. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos GW, Yeager AM, Jones RJ. Autologous bone marrow transplantation. Annual review of medicine. 1989;40:99–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.40.020189.000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schultz FW, Martens AC, Hagenbeek A. The contribution of residual leukemic cells in the graft to leukemia relapse after autologous bone marrow transplantation: mathematical considerations. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 1989;3:530–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brenner MK, Rill DR, Moen RC, et al. Gene-marking to trace origin of relapse after autologous bone-marrow transplantation. Lancet. 1993;341:85–86. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92560-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siehl JM, Thiel E, Leben R, Reinwald M, Knauf W, Menssen HD. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR detects elevated Wilms tumor gene (WT1) expression in autologous blood stem cell preparations (PBSCs) from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients indicating contamination with leukemic blasts. Bone marrow transplantation. 2002;29:379–381. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osborne D, Frost L, Tobal K, Liu Yin JA. Elevated levels of WT1 transcripts in bone marrow harvests are associated with a high relapse risk in patients autografted for acute myeloid leukaemia. Bone marrow transplantation. 2005;36:67–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butturini A, Klein J, Gale RP. Modeling minimal residual disease (MRD)-testing. Leukemia research. 2003;27:293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feller N, Schuurhuis GJ, van der Pol MA, et al. High percentage of CD34-positive cells in autologous AML peripheral blood stem cell products reflects inadequate in vivo purging and low chemotherapeutic toxicity in a subgroup of patients with poor clinical outcome. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2003;17:68–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hengeveld M, Suciu S, Chelgoum Y, et al. High numbers of mobilized CD34+ cells collected in AML in first remission are associated with high relapse risk irrespective of treatment with autologous peripheral blood SCT or autologous BMT. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50:341–347. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keating S, Suciu S, de Witte T, et al. The stem cell mobilizing capacity of patients with acute myeloid leukemia in complete remission correlates with relapse risk: results of the EORTC-GIMEMA AML-10 trial. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2003;17:60–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Grunigen I, Raschle J, Rusges-Wolter I, Taleghani BM, Mueller BU, Pabst T. The relapse risk of AML patients undergoing autologous transplantation correlates with the stem cell mobilizing potential. Leukemia research. 2012;36:1325–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gorin NC, Labopin M, Reiffers J, et al. Higher incidence of relapse in patients with acute myelocytic leukemia infused with higher doses of CD34+ cells from leukapheresis products autografted during the first remission. Blood. 2010;116:3157–3162. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-252197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jurlander J, Caligiuri MA, Ruutu T, et al. Persistence of the AML1/ETO fusion transcript in patients treated with allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for t(8;21) leukemia. Blood. 1996;88:2183–2191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyamoto T, Nagafuji K, Akashi K, et al. Persistence of multipotent progenitors expressing AML1/ETO transcripts in long-term remission patients with t(8;21) acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1996;87:4789–4796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakasone H, Izutsu K, Wakita S, Yamaguchi H, Muramatsu-Kida M, Usuki K. Autologous stem cell transplantation with PCR-negative graft would be associated with a favorable outcome in core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14:1262–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hokland P, Ommen HB, Nyvold CG, Roug AS. Sensitivity of minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukaemia in first remission--methodologies in relation to their clinical situation. British journal of haematology. 2012;158:569–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ivey A, Hills RK, Simpson MA, et al. Assessment of Minimal Residual Disease in Standard-Risk AML. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;374:422–433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klco JM, Miller CA, Griffith M, et al. Association Between Mutation Clearance After Induction Therapy and Outcomes in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;314:811–822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gale RP. Measureable residual disease (MRD): much ado about nothing? Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50:163–164. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.