Abstract

Kidney transplantation is the preferred treatment for pediatric end stage renal disease (ESRD). Preemptive transplantation avoids the increased morbidity and mortality of dialysis. Yet, prior studies have not demonstrated significant graft or patient survival benefits for children transplanted preemptively versus non-preemptively. These previous studies were limited by small samples sizes and low rates of adverse events. Here, we compared graft failure and mortality rates, using Kaplan-Meier methods and Cox regression, among a large, national cohort of children with ESRD receiving preemptive versus non-preemptive kidney transplant between 2000 and 2012. Among 7,527 pediatric kidney transplant recipients in the United States Renal Data System, 1668 were transplanted preemptively. Over a median 4.8 years follow-up, 1314 experienced graft failure and over median 5.2 years of follow-up, 334 died. Dialysis exposure versus preemptive transplant conferred higher risk of graft failure (hazard ratio 1.32; 95% confidence interval: 1.10–1.56) and higher risk of death (hazard ratio 1.69; 95% confidence interval: 1.22–2.33) in multivariable analysis. Compared with children transplanted preemptively, children on dialysis for more than one year had 52% higher risk of graft failure and those on dialysis more than 18 months had 89% higher risk of death, regardless of donor source. Thus, preemptive transplantation is associated with substantial benefits in allograft and patient survival among children with ESRD, particularly when compared with children who receive dialysis for over one year. These findings support policies to promote early access to transplant and avoidance of dialysis for children with ESRD whenever feasible.

Keywords: pediatric kidney transplantation, preemptive, United States

Introduction

Preemptive renal transplantation, which is defined as transplantation prior to the initiation of dialysis, is well established as the optimal treatment for adults with end stage renal disease (ESRD),1 but the benefits of preemptive renal transplantation for children are less clear. For adults, renal transplant recipients have longer survival and improved quality of life, as compared to dialysis patients.2 The median waiting time to transplant for an adult on dialysis in the United States (US) is four to five years (1416–1813 days)3 and longer time on dialysis adversely impacts graft and patient survival.4,5 Preemptive transplantation avoids the morbidity and cost associated with dialysis as well as surgical dialysis access and its complications.6,7 In contrast, children with ESRD in the US experience much shorter waiting times to transplantation, with a median waiting time of less than one year for a child 1–17 years of age; although, wide geographic variability in pediatric waiting times has been noted, with a range of 14 to 1313 days across donor services areas.8

For children who are dependent on dialysis, there are well documented adverse effects on cognitive function, growth, anemia, bone-mineral regulation, cardiovascular disease and overall lifespan, as compared with transplant.9–14 However, the benefits of completely circumventing dialysis for children with ESRD have not been clearly demonstrated. Several studies have demonstrated no differences in patient or graft survival between children receiving preemptive vs. non-preemptive transplant15–21 and there is some evidence to suggest discrepancies in the graft survival benefits of preemptive transplants by donor source.22–24 Importantly, the majority of these studies have been limited by small sample size and few events.15–24 We hypothesized that given a large, national sample of children with ESRD followed over a decade, we would observe significant patient and graft survival benefits of preemptive vs. non-preemptive kidney transplantation and would be able to discern whether any differences exist across donor source.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Overall Study Cohort

Among the 7,527 pediatric transplant recipients included in the study population, 55.2% (N=4,157) received a deceased donor (DD) transplant and 44.8% (N=3,370) received a living donor (LD) transplant (Table 1). The majority of DD and LD recipients were white non-Hispanic (49.3%), male (58.9%) and aged 11–17 years (59.5%). The most common causes of ESRD were congenital anomalies of the kidney and urologic tract (CAKUT) (45.7%). Over half of transplant recipients (54.8%) had public insurance. The mean donor age was 28.7 years, although this was significantly higher in the LD recipients. More than half (61%) of patients were transplanted during the Share 35 Policy era (post September 2005). 28.4% of children with ESRD in this cohort lived in neighborhoods in which more than 20% of their ZIP code lived below the poverty level.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population of US Pediatric (0–17 yrs) Kidney Transplant Recipients by Donor Type: 2000–2012

| Total Study Population N=7,527 |

Deceased Donor (55.2%) (N=4,157) | Living Donor (44.8%) (N=3,370) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non- Preemptive N = 3,593 (86.4%) |

Preemptive N= 564 (13.6%) |

P-valueǂ | Non- Preemptive N = 2,266 (67.2%) |

Preemptive N=1,104 (32.8%) |

P- valueǂ |

||

| Patient-Level Characteristics | |||||||

|

Age, Mean (SD) years |

10.8 ± 5.3 | 11.7 ± 4.9 | 10.7 ± 5.0 | <0.0001 | 9.7 ± 5.6 | 10.3 ± 5.1 | 0.0013 |

| Age Category, N (%), yrs | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| ≤ 5 yrs | 1674 (22.2%) | 598 (16.6%) | 118 (20.9%) | 705 (31.1%) | 253 (22.9%) | ||

| 6–10 yrs | 1377 (18.3%) | 616 (17.1%) | 127 (22.5%) | 390 (17.2%) | 244 (22.1%) | ||

| 11–17 yrs | 4476 (59.5%) | 2379 (66.2%) | 319 (55.6%) | 1171 (51.7%) | 607 (55.0%) | ||

| Male, N (%) | 4433 (58.9%) | 2008 (55.9%) | 379 (67.2%) | <0.0001 | 1316 (58.1%) | 730 (66.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 3710 (49.3%) | 1336 (37.2%) | 269 (47.7%) | 1394 (61.5%) | 711 (64.4%) | ||

| White Hispanic | 1635 (21.7%) | 1011 (28.1%) | 92 (16.3%) | 438 (19.3%) | 94 (8.5%) | ||

| Black | 1299 (17.3%) | 914 (25.4%) | 59 (10.5%) | 266 (11.7%) | 60 (5.4%) | ||

| Other | 883 (11.7%) | 332 (9.2%) | 144 (25.5%) | 168 (7.4%) | 239 (21.7%) | ||

| BMI > 85%(kg/m2)1 | 1015 (13.5%) | 554 (15.4%) | 101 (17.9%) | 0.1315 | 216 (9.5%) | 144 (13.0%) | 0.0020 |

| Cause of ESRD, N (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| GN2 | 693 (9.2%) | 407 (11.3%) | 13 (2.3%) | 234 (10.3%) | 39 (3.5%) | ||

| Secondary GN | 448 (6.0%) | 220 (6.1%) | <10 (1.2%) | 191 (8.4%) | 30 (2.7%) | ||

| CAKUT | 3443 (45.7%) | 1398 (38.9%) | 358 (63.5%) | 988 (43.6%) | 699 (63.3%) | ||

| FSGS3 | 937 (12.5%) | 571 (15.9%) | 38 (6.7%) | 289 (12.8%) | 39 (3.5%) | ||

| Lupus Nephritis | 132 (1.8%) | 105 (2.9%) | <10 (<1%) | 21 (0.9%) | <10 (<1%) | ||

| Other | 1874 (24.9%) | 892 (24.8%) | 146 (25.9%) | 543 (24.0%) | 293 (26.5%) | ||

| Insurance Type | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Public | 4128 (54.8%) | 2483 (69.1%) | 296 (52.5%) | 1056 (46.6%) | 293 (26.5%) | ||

| Private | 3264 (43.4%) | 1061 (29.5%) | 243 (43.1%) | 1182 (52.2%) | 778 (70.5%) | ||

| Other | 135 (1.8%) | 49 (1.4%) | 25 (4.4%) | 28 (1.2%) | 33 (3.0%) | ||

| Blood Type (%) ** | <0.0001 | 0.3559 | |||||

| A | 2520 (33.5%) | 1068 (29.7%) | 195 (34.6%) | 835 (36.9%) | 422 (38.2%) | ||

| B | 918 (12.2%) | 450 (12.5%) | 67 (11.9%) | 281 (12.4%) | 120 (10.9%) | ||

| AB | 271 (3.6%) | 123 (3.4%) | 27 (4.8%) | 75 (3.3%) | 46 (4.2%) | ||

| O | 3744 (49.7%) | 1950 (54.3%) | 266 (47.2%) | 1036 (45.7%) | 492 (44.6%) | ||

| Cold Ischemia time (hrs) among deceased donors** | 0.5129 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| 0–12 | 1551 (42.3%) | 1331 (42.0%) | 220 (44.7%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 12.1–24 | 1732 (47.3%) | 1508 (47.6%) | 224 (45.5%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| > 24 | 380 (10.4%) | 332 (10.5%) | 48 (9.8%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

|

Donor Age, Mean (yrs)** |

28.7 ± 11.7 | 22.0 ± 9.6 | 21.0 ± 9.3 | 0.0211 | 36.0 ± 8.5 | 37.9 ± 8.5 | <0.0001 |

| PRA | 0.7327 | 0.0935 | |||||

| <20% | 5508 (73.2%) | 2450 (68.2%) | 392 (69.5%) | 1816 (80.4%) | 850 (77.0%) | ||

| 20–80% | 1404 (18.7%) | 792 (22.0%) | 116 (21.8%) | 314 (13.9%) | 182 (16.5%) | ||

| > 80% | 615 (8.2%) | 351 (9.8%) | 56 (9.9%) | 136 (6.0%) | 72 (6.5%) | ||

| HLA mismatch, N (%) ** | 0.0101 | 0.3780 | |||||

| 0 | 217 (2.9%) | 77 (2.1%) | 18 (3.2%) | 85 (3.8%) | 37 (3.4%) | ||

| 1 | 331 (4.4%) | 11 (0.3%) | <10 (<1%) | 210 (9.3%) | 106 (9.6%) | ||

| 2 | 1083 (14.4%) | 90 (2.5%) | <10 (1.1%) | 677 (29.9%) | 310 (28.1%) | ||

| 3 | 1785 (23.7%) | 368 (10.2%) | 64 (11.4%) | 895 (39.5%) | 458 (41.5%) | ||

| 4 | 1336 (17.8%) | 984 (27.4%) | 154 (27.3%) | 139 (6.1%) | 59 (5.3%) | ||

| 5 | 1672 (22.2%) | 1277 (35.5%) | 184 (32.6%) | 141 (6.2%) | 70 (6.3%) | ||

| 6 | 880 (11.7%) | 668 (18.6%) | 102 (18.1%) | 78 (3.4%) | 32 (2.9%) | ||

|

Share 35 Policy Era4 |

4589 (61.0%) | 2388 (66.5%) | 428 (75.9%) | <0.0001 | 1135 (50.1%) | 638 (57.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Neighborhood Poverty (% of ZIP code below poverty level) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0–4.9% | 786 (10.4%) | 228(6.5%) | 69 (12.7%) | 290 (13.0%) | 199 (18.3%) | ||

| 5–9.9% | 1651 (21.9%) | 614 (17.4%) | 126 (23.1%) | 596 (26.6%) | 315 (29.0%) | ||

| 10–14.9% | 1502 (20.0%) | 688 (19.5%) | 103 (18.9%) | 467 (20.9%) | 244 (22.5%) | ||

| 15–19.9% | 1311 (17.4%) | 681 (19.3%) | 98 (18.0%) | 392 (17.5%) | 140 (12.9%) | ||

| >20% | 2140 (28.4%) | 1311 (37.2%) | 149 (27.3%) | 493 (22.0%) | 187 (17.2%) | ||

Body Mass Index; 85% was 25.2 kg/m2 for this population

Glomerulonephritis

Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

Post-Sept. 2005 vs. Pre-Sept. 2005

p-values < 0.05 for each variable indicate that at least one variable level is significantly different across preemptive transplant status.

Missing data: 1.0% missing blood type; 13.5% missing cold ischemia time, 3.6% missing donor age; 3.0% missing HLA mismatch; 1.9% missing neighborhood poverty data; 14.4% of PRA data were missing and assumed to be a value of 0.

(Please note per USRDS policy, any cells with N<10 are denoted as such to promote patient confidentiality.)

Baseline Characteristics of Pediatric Transplant Recipients by Donor Type and Preemptive vs. Non-Preemptive

A total of 1668 (22.2%) pediatric transplant recipients received a preemptive donor transplant, of which the majority (66.2%) was LD vs. DD (33.8%) (Table 1). Of patients receiving DD transplants, 13.6% (N=564) were transplanted preemptively. As compared to the non-preemptively transplanted DD recipients, the preemptive DD transplant recipients were younger, more likely to be white non-Hispanic and male, to have CAKUT, to have private insurance and live in wealthier neighborhoods. Among the children receiving LD transplants, 32.8% (N=1,104) were transplanted preemptively. In the LD recipient group, preemptively transplanted patients (vs. non-preemptively transplanted patients) were slightly older but also more likely to be white non-Hispanic and male with a diagnosis of CAKUT, with private insurance and living in wealthier communities.

Characteristics Associated with Graft Failure among Preemptive vs. Nonpreemptive Pediatric Kidney Transplant Recipients

A total of 1314 patients (17.5%) experienced graft failure during the median follow-up of 4.8 years (IQR: 2.3, 7.8) (Table 2). There was a lower proportion of graft failure among patients who received a preemptive vs. non-preemptive transplant (9.5% vs. 19.7%, p<0.0001). Results were consistent across donor type; among patients who received a DD preemptive transplant, 12.9% experienced graft failure while 24% of non-preemptive DD transplant recipients experienced graft failure (p<0.0001). Among patients who received any LD transplant, there were fewer graft failure events overall compared to those who received a DD transplant (11.2% vs. 22.5%, p<0.0001), but LD recipients who received a preemptive LD transplant still had fewer graft failures compared to those who received pre-transplant dialysis (7.7% vs. 12.9%, p<0.0001). In both DD and LD transplant recipients, patients experiencing graft failure were older, with the majority in the 11–17 year age range. Black patients made up a disproportionate percentage of LD and DD transplant recipients experiencing graft failure, representing 33.6% of all graft failures but only 17.3% of the total study cohort. Similarly, patients with a body mass index > 85% made up only 13.5% of transplant recipients but 19.4% of the transplant recipients experiencing graft failure. In regards to etiology of ESRD, graft losses in patients who were not transplanted preemptively occurred more commonly in patients with glomerulonephritides, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) or lupus. Although these diagnoses were less common among patients transplanted preemptively, a greater proportion of preemptively transplanted patients with these diagnoses experienced graft loss. Patients who lost their grafts had public insurance more often. Interestingly, number of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch had no correlation with graft failure for preemptive transplant recipients but greater numbers of HLA mismatches were associated with increased graft failure among patients receiving non-preemptive transplants. Among the preemptively transplanted patients who experienced graft failure, the distribution of those living in poverty reflected the poverty distribution in the overall cohort. In contrast, among the non-preemptively transplanted group, graft failure was skewed toward patients living in higher poverty neighborhoods.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics associated with Graft Failure among USRDS Pediatric Kidney Transplant Recipients 2000–2012

| Total Study Population N=7,527 |

Preemptive Transplants (22.2%) (n=1668) |

Non-Preemptive Transplants (77.8%) (n=5859) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Graft Failure N= 1510 (90.5%) |

Graft Failure N=158 (9.5%) |

P-valueǂ | No Graft Failure N=4703 (80.3%) |

Graft Failure N=1156 (19.7%) |

P- valueǂ |

||

| Patient-Level Characteristics | |||||||

|

Age, Mean (SD) years |

10.8 ± 5.3 | 10.3 ± 5.0 | 12.0 ± 5.1 | <0.0001 | 10.5 ± 5.4 | 12.7 ± 4.6 | <0.0001 |

| Age Category, N (%), yrs | 0.0008 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0–5 yrs | 1674 (22.2%) | 345 (22.9%) | 26 (16.5%) | 1167 (24.8%) | 136 (11.8%) | ||

| 6–10 yrs | 1377 (18.3%) | 349 (23.1%) | 22 (13.9%) | 846 (18.0%) | 160 (13.8%) | ||

| 11–17 yrs | 4476 (59.5%) | 816 (54.0%) | 110 (69.6%) | 2690 (57.2%) | 860 (74.4%) | ||

| Male, N (%) | 4433 (58.9%) | 1015 (67.2%) | 94 (59.5%) | 0.0503 | 2735 (58.2%) | 589 (51.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 3710 (49.3%) | 890 (58.9%) | 90 (57.0%) | 2285 (48.6%) | 445 (38.5%) | ||

| White Hispanic | 1635 (21.7%) | 169 (11.2%) | 17 (10.8%) | 1237 (26.3%) | 212 (18.3%) | ||

| Black | 1299 (17.3%) | 92 (6.1%) | 27 (17.1%) | 765 (16.3%) | 415 (35.9%) | ||

| Other | 883 (11.7%) | 359 (23.8%) | 24 (15.2%) | 416 (8.9%) | 84 (7.3%) | ||

| BMI > 85%(kg/m2)1 | 1015 (13.5%) | 201 (13.3%) | 44 (27.9%) | <0.0001 | 559 (11.9%) | 211 (18.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Cause of ESRD, N (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| GN2 | 693 (9.2%) | 44 (2.9%) | <10 (5.1%) | 478 (10.2%) | 163 (14.1%) | ||

| Secondary GN | 448 (6.0%) | 35 (2.3%) | <10 (1.3%) | 351 (7.5%) | 60 (5.2%) | ||

| CAKUT | 3443 (45.7%) | 983 (65.1%) | 74 (46.8%) | 2024 (43.0%) | 362 (31.3%) | ||

| FSGS3 | 937 (12.5%) | 61 (4.0%) | 16 (10.1%) | 621 (13.2%) | 239 (20.7%) | ||

| Lupus Nephritis | 132 (1.8%) | 4 (0.3%) | <10 (1.3%) | 83 (1.8%) | 43 (3.7%) | ||

| Other | 1874 (24.9%) | 383 (25.4%) | 56 (35.4%) | 1146 (24.4%) | 289 (25.0%) | ||

| Insurance Type | 0.0241 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Public | 4128 (54.8%) | 518 (34.3%) | 71 (44.9%) | 2767 (58.8%) | 772 (66.8%) | ||

| Private | 3264 (43.4%) | 940 (62.3%) | 81 (51.3%) | 1866 (39.7%) | 377 (32.6%) | ||

| Other | 135 (1.8%) | 52 (3.4%) | <10 (3.8%) | 70 (1.5%) | <10 (<1%) | ||

| Blood Type (%) | 0.7220 | 0.3344 | |||||

| A | 2520 (33.5%) | 562 (37.2%) | 55 (34.8%) | 1522 (32.6%) | 381 (33.0%) | ||

| B | 918 (12.2%) | 170 (11.3%) | 17 (10.8%) | 569 (12.2%) | 162 (14.0%) | ||

| AB | 271 (3.6%) | 67 (4.4%) | <10 (3.8%) | 161 (3.5%) | 37 (3.2%) | ||

| O | 3744 (49.7%) | 678 (44.9%) | 80 (50.6%) | 2412 (51.7%) | 574 (49.7%) | ||

| Donor Source | 0.0005 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Deceased | 4157 (55.2%) | 491 (32.5%) | 73 (46.2%) | 2729 (58.0%) | 864 (74.7%) | ||

| Living | 3370 (44.8%) | 1019 (67.5%) | 85 (53.8%) | 1974 (42.0%) | 292 (25.3%) | ||

| Cold Ischemia time (hrs) among deceased donors** | 0.2020 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0–12 | 1551 (42.3%) | 195 (45.5%) | 25 (39.7%) | 1074 (44.3%) | 257 (34.4%) | ||

| 12.1–24 | 1732 (47.3%) | 196 (45.7%) | 28 (44.4%) | 1113 (45.9%) | 395 (52.9%) | ||

| > 24 | 380 (10.4%) | 38 (8.9%) | 10 (15.9%) | 237 (9.8%) | 95 (12.7%) | ||

|

Donor Age, Mean (yrs) |

28.7 ± 11.7 | 32.8 ± 11.8 | 29.7 ± 12.1 | 0.0022 | 27.8 ± 11.2 | 27.1 ± 12.3 | 0.0916 |

| HLA mismatch, N (%) | 0.7665 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0 | 217 (2.9%) | 50 (3.3%) | <10 (3.2%) | 143 (3.1%) | 19 (1.7%) | ||

| 1 | 331 (4.4%) | 101 (6.7%) | <10 (5.7%) | 198 (4.3%) | 23 (2.1%) | ||

| 2 | 1083 (14.4%) | 292 (19.3%) | 24 (15.2%) | 675 (14.7%) | 92 (8.2%) | ||

| 3 | 1785 (23.7%) | 475 (31.5%) | 47 (29.8%) | 1053 (23.0%) | 210 (18.8%) | ||

| 4 | 1336 (17.8%) | 189 (12.5%) | 24 (15.2%) | 857 (18.7%) | 266 (23.8%) | ||

| 5 | 1672 (22.2%) | 226 (15.0%) | 28 (17.7%) | 1081 (23.6%) | 337 (30.1%) | ||

| 6 | 880 (11.7%) | 120 (8.0%) | 14 (8.9%) | 574 (12.5%) | 172 (15.4%) | ||

|

Share 35 Policy Era4 |

4589 (61.0%) | 1002 (66.4%) | 64 (40.5%) | <0.0001 | 3050 (64.9%) | 473 (40.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Neighborhood Poverty (% of ZIP code below poverty level) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0–4.9% | 786 (10.4%) | 249 (16.9%) | 19 (12.3%) | 449 (9.7%) | 69 (6.1%) | ||

| 5–9.9% | 1651 (21.9%) | 412 (27.9%) | 29 (18.7%) | 1031 (22.3%) | 179 (15.8%) | ||

| 10–14.9% | 1502 (20.0%) | 307 (20.8%) | 40 (25.8%) | 928 (20.1%) | 227 (20.0%) | ||

| 15–19.9% | 1311 (17.4%) | 213 (14.4%) | 25 (16.1%) | 865 (18.7%) | 208 (18.3%) | ||

| >20% | 2140 (28.4%) | 294 (19.9%) | 42 (27.1%) | 1352 (29.2%) | 452 (39.8%) | ||

p-values < 0.05 for each variable indicate that at least one variable level is significantly different across preemptive transplant status.

Body Mass Index

Glomerulonephritis

Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

Post-Sept. 2005 vs. Pre-Sept. 2005

Missing data: 1.0% missing blood type; 13.5% missing cold ischemia time, 3.6% missing donor age; 3.0% missing HLA mismatch; 1.9% missing neighborhood poverty data

(Please note per USRDS policy, any cells with N<10 are denoted as such to promote patient confidentiality.)

Time to Graft Failure

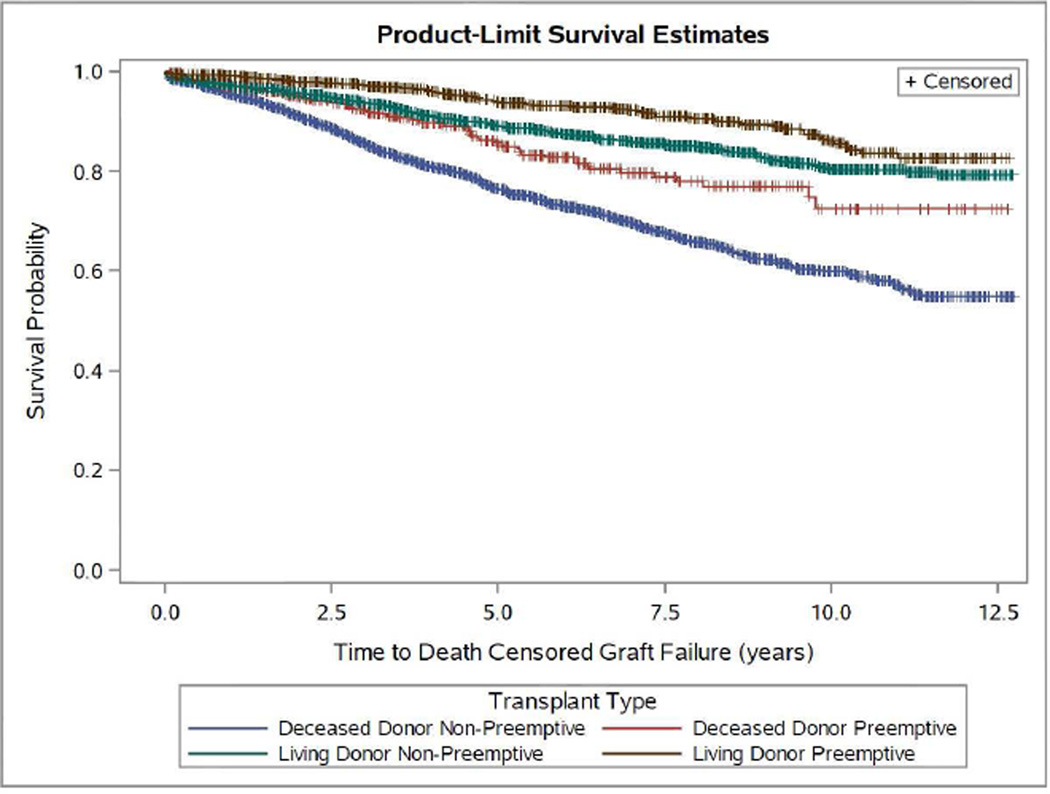

Examination of graft survival rates amongst DD transplant recipients indicated statistically significant benefits in graft survival for preemptive (vs. non-preemptive) transplant recipients as early as two years post-transplant (94.9% vs 91%; p<0.001), a benefit that trended to larger value and significance in a linear fashion, with the most marked difference noted at five years (85.4% vs 76.4%, p<0.0001) (Figure 1A and Table 3). In LD recipients, the graft survival differences between preemptive and non-preemptively transplanted patients were observed as early as 1 year post-transplant (99.2% vs 97.3%; p=0.0002), and, similar to DD recipients, the largest benefit of preemptive transplant was evident at five years (93.8% vs 89.2%; p<0.0001) (Figure 1A and Table 3).

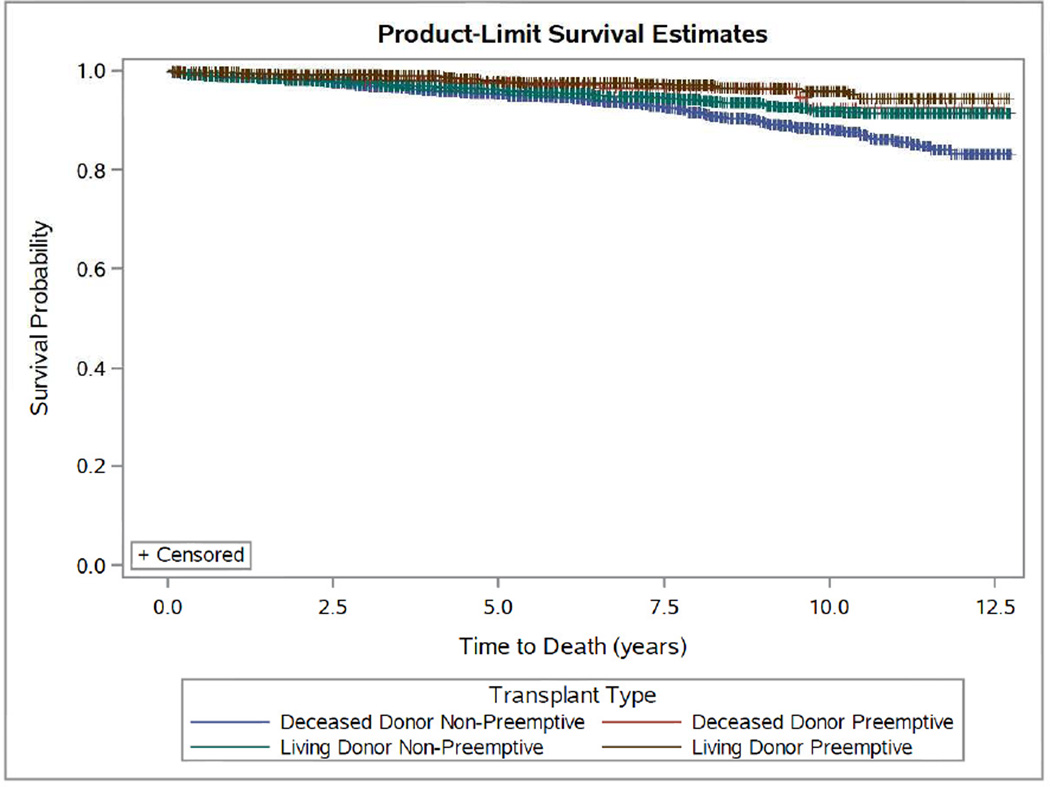

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Estimates for Time to Death-Censored Graft Failure (A) and Mortality (B) by Preemptive Living Donor, Non-Preemptive Living Donor, Preemptive Deceased Donor and Non-Preemptive Deceased Donor Pediatric Transplant Recipients: 2000–2012. (P<0.0001 for both outcomes.)

Table 3.

Comparison of Death-Censored Graft Survival among Pediatric Patients Receiving Preemptive Transplant vs. Transplant Following Dialysis

| Deceased Donor Transplant Recipients Survival (%) and 95% Confidence Interval |

Living Donor Transplant Recipients Survival (%) and 95% Confidence Interval |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Time |

Total N at Risk In Cohort |

Non- Preemptive |

Preemptive | Log-Rank P- valueǂ |

Non-Preemptive | Preemptive | Log- Rank P- valueǂ |

| 1 month | 7,438 | 98.5 (98.1–98.9) |

99.6 (99.0–99.9) |

0.2007 | 98.9 (98.3–99.2) |

99.7 (99.2–99.9) |

0.0786 |

| 6 months | 7,109 | 97.4 (96.8–97.9) |

98.4 (97.2–99.3) |

0.2112 | 98.1 (97.6–98.7) |

99.3 (98.7–99.7) |

0.1440 |

| 1 year | 6,727 | 95.5 (94.7–96.1) |

97.1 (95.5–98.3) |

0.0923 | 97.3 (96.6–97.9) |

99.2 (98.6–99.6) |

0.0002 |

| 2 years | 5,926 | 91.0 (90.0–92.0) |

94.9 (92.8–96.6) |

<0.001 | 95.6 (94.7–96.5) |

98.0 (97.0–98.7) |

<0.0001 |

| 3 years | 5,119 | 85.5 (84.2–86.7) |

92.1 (89.5–94.4) |

<0.001 | 93.8 (92.7–94.8) |

97.3 (96.1–98.2) |

<0.0001 |

| 5 years | 3,619 | 76.4 (74.8–78.1) |

85.4 (81.5–88.8) |

<0.001 | 89.1 (87.6–90.5) |

993.8 (92.0–95.3) |

<0.0001 |

p-values < 0.05 for each variable indicate that there are significant differences in graft survival across preemptive vs. non-preemptive transplant groups

Across the entire cohort, any dialysis exposure was associated with a 32% higher rate of graft failure (HR 1.32; 95% CI: 1.10–1.56) in multivariable analysis adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, age at time of transplant, etiology of ESRD, panel reactive antibody (PRA), cold ischemia time, insurance status at time of transplant, neighborhood poverty and donor type (Table 4). When we categorized the non-preemptive group by dialysis duration, significant graft survival benefits were observed between patients transplanted preemptively and those on dialysis for as little as 6 months. However, when stratified by donor source, the graft survival benefit of preemptive transplantation was statistically significant only compared with children who were on dialysis for more than one year. Compared with children transplanted preemptively with DD or LD, children on dialysis for more than 12 months had a 52% higher rate of graft failure (Table 4).

Table 4.

Crude and Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis of Graft Failure and Mortality Comparing Preemptive Transplant with Effect of Dialysis by Vintage: United States Renal Data System Pediatric Transplant Recipients 2000–2012

| Preemptive vs. Non-Preemptive Transplant | Crude Hazard Ratio | Multivariable-Adjusted Hazard Ratio 95% CI* |

|---|---|---|

| Graft Failure | ||

| All Transplant Recipients | 2.13 (1.82–2.50)ǂ | 1.32 (1.10–1.56)ǂ |

| Non-Preemptive vs. Preemptive | ||

| Deceased Donor Transplant Recipients | ||

| 0–6 months vs. Preemptive | 1.64 (1.23–2.22)ǂ | 1.25 (0.93–1.67) |

| 6–12 months vs. Preemptive | 1.79 (1.33–2.33)ǂ | 1.30 (0.97–1.72) |

| 12–18 months vs. Preemptive | 1.92 (1.45–2.50)ǂ | 1.47 (1.10–1.92)ǂ |

| >18 months vs. Preemptive | 1.92 (1.49–2.44)ǂ | 1.43 (1.11–1.85)ǂ |

| Living Donor Transplant Recipients | ||

| 0–6 months vs. Preemptive | 1.49 (1.11–2.04)ǂ | 1.27 (0.92–1.72) |

| 6–12 months vs. Preemptive | 2.70 (1.20–1.27)ǂ | 1.30 (0.93–1.82) |

| 12–18 months vs. Preemptive | 1.85 (1.33–2.56)ǂ | 1.56 (1.10–2.22)ǂ |

| > 18 months vs. Preemptive | 1.72 (1.27–2.33)ǂ | 1.56 (1.14–2.17)ǂ |

| All Transplant Recipients | ||

| 0–6 months vs. Preemptive | 1.69 (1.37–2.08)ǂ | 1.28 (1.03–1.59)ǂ |

| 6–12 months vs. Preemptive | 2.04 (1.64–2.50)ǂ | 1.32 (1.08–1.64)ǂ |

| 12–18 months vs. Preemptive | 2.27 (1.85–2.78)ǂ | 1.52 (1.22–1.89)ǂ |

| > 18 months vs. Preemptive | 2.56 (2.17–3.13)ǂ | 1.47 (1.22–1.79)ǂ |

| Mortality | ||

| All Transplant Recipients | 2.13 (1.54–2.86)ǂ | 1.69 (1.22–2.33)ǂ |

| Non-Preemptive vs. Preemptive | ||

| Deceased Donor Transplant Recipients | ||

| 0–6 months vs. Preemptive | 1.79 (0.97–3.33) | 1.59 (0.85–2.94) |

| 6–12 months vs. Preemptive | 1.69 (0.94–3.13) | 1.45 (0.78–2.63) |

| 12–18 months vs. Preemptive | 2.04 (1.15–3.70)ǂ | 1.82 (1.00–3.23) |

| > 18 months vs. Preemptive | 2.13 (1.25–3.57)ǂ | 1.75 (1.02–3.03)ǂ |

| Living Donor Transplant Recipients | ||

| 0–6 months vs. Preemptive | 1.82 (1.10–2.94)ǂ | 1.64 (0.98–2.70) |

| 6–12 months vs. Preemptive | 1.92 (1.14–3.23)ǂ | 1.67 (0.95–2.86) |

| 12–18 months vs. Preemptive | 1.92 (1.09–3.33)ǂ | 1.61 (0.90–2.86) |

| > 18 months vs. Preemptive | 2.27 (1.37–3.70)ǂ | 2.00 (1.18–3.33)ǂ |

| All Transplant Recipients | ||

| 0–6 months vs. Preemptive | 1.85 (1.27–2.70)ǂ | 1.67 (1.12–2.44)ǂ |

| 6–12 months Preemptive | 1.92 (1.32–2.86)ǂ | 1.59 (1.05–2.33)ǂ |

| 12–18 months vs. Preemptive | 2.17 (1.49–3.23)ǂ | 1.79 (1.20–2.70)ǂ |

| > 18 months vs. Preemptive | 2.50 (1.79–3.57)ǂ | 1.89 (1.32–2.70)ǂ |

Note p-value for Preemptive Transplant and Donor Type Interaction Not Significant in Crude and Multivariable-adjusted Analyses for either Graft Failure (p=0.6172) or Death (p=0.8470).

Multivariable model adjusts for Sex, Race/Ethnicity, Age at time of transplant, Etiology of ESRD, Panel Reactive Antibody, Insurance Status at the time of Transplant, Neighborhood Poverty, Donor Type (in combined donor type models), and Cold Ischemia Time (in deceased donor recipient models)

p-value<0.05

Mortality

A total of 334 patients (4.4%) in the study population died during a median follow-up time of 5.2 years. There were fewer deaths (N=37, 2.4%) among patients who received a preemptive transplant versus those who received a transplant following dialysis (N=297, 5.4%) (p<0.0001). In crude Kaplan-Meier survival models, when stratified by follow-up time, reduced mortality in patients receiving preemptive DD transplants was evident at 5 years post-transplant (97.5% preemptive vs 95.0% non-preemptive, p=0.0040) (Figure 1B and Table 5). In contrast, preemptive (vs. non-preemptive) LD transplant conveyed significant survival benefit as early as one year post-transplant and through five years, although with no direct linear cumulative effect was noted (Figure 1B and Table 5). In multivariable Cox models, across the entire cohort, dialysis exposure was associated with a 69% increase in mortality rate (HR 1.69; 95% CI: 1.22–2.33) (Table 4). When we analyzed preemptive transplant in comparison to varying time on dialysis, we observed clear and substantial survival benefits in multivariable analyses for both DD and LD preemptive transplants compared to children on prolonged dialysis. Compared with children transplanted preemptively with DD, we observed a 75% higher rate of mortality for DD transplant recipients on dialysis > 18 months (HR 1.75; 95% CI: 1.02–3.03) and 2-fold higher rate of mortality for LD transplant recipients on dialysis over 18 months (vs. preemptive LD) (HR 2.00; 95% CI: 1.18–3.33) (Table 4).

Table 5.

Comparison of Crude Mortality in Pediatric Patients Receiving Preemptive Transplant vs. Transplant Following Dialysis: United States Renal Data System Pediatric Transplant Recipients 2000–2012

| Follow-up Time |

Mortality Among Deceased Donor Transplant Recipients 95% CI |

Mortality Among Living Donor Transplant Recipients 95% CI |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N at Risk In Cohort |

Non- Preemptive |

Preemptive | Log-rank P-valueǂ |

N at Risk in Cohort |

Non- Preemptive |

Preemptive | Log- Rank P-valueǂ |

|

| 1 month | 4140 | 99.6 (99.4–99.8) |

99.8 (99.2–99.9) |

0.1188 | 3360 | 99.8 (99.5–99.9) |

99.8 (99.4–99.9) |

0.7256 |

| 6 months | 3970 | 99.1 (98.8–99.5) |

99.0 (97.9–99.7) |

0.7817 | 3258 | 99.2 (98.2–99.1) |

99.5 (99.0–99.8) |

0.0556 |

| 1 year | 3765 | 98.5 (98.1–98.9) |

98.3 (97.0–99.3) |

0.3432 | 3109 | 98.7 (98.1–99.1) |

99.5 (99.0–99.8) |

0.0020 |

| 2 years | 3379 | 98.0 (97.5–98.5) |

98.1 (96.6–99.1) |

0.3095 | 2848 | 98.1 (97.4–98.7) |

99.3 (98.8–99.8) |

0.0002 |

| 3 years | 2954 | 96.9 (96.2–97.5) |

97.5 (95.8–98.8) |

0.1222 | 2590 | 97.4 (96.6–98.0) |

99.3 (98.6–99.7) |

<0.0001 |

| 5 years | 2120 | 95.0 (94.1–95.8) |

97.5 (95.8–98.8) |

0.0040 | 2050 | 96.1 (95.2–97.0) |

97.9 (97.4–99.2) |

0.0004 |

| Study Period | 4157 | 84.0 (80.4–87.3) |

89.2 (78.0–96.7) |

0.0567 | 3370 | 91.3 (89.2–93.3) |

96.2 (94.2–97.7) |

0.0009 |

p-values < 0.05 for each variable indicate that there are significant differences in graft survival across preemptive vs. non-preemptive transplant groups

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, given that preemptive transplantation necessitates sufficient size and weight, we repeated our main analyses excluding children < 2 years of age at the time of ESRD. The results of these analyses (non-preemptive vs. preemptive) were similar to the main analyses for both graft failure (HR 1.35; 95% CI: 1.11–1.61) and patient mortality (HR 1.89; 95% CI: 1.30–2.70). Second, we recognize that children with glomerular disease generally progress more rapidly to ESRD25, allowing less time to prepare for preemptive transplant. For this reason, we conducted another sensitivity analysis in which we restricted the cohort to those with CAKUT diagnoses only. Restricting to CAKUT alone yielded even stronger findings for the negative impact of dialysis exposure (vs. preemptive transplant) for graft failure (HR 1.56; 95% CI: 1.19–2.00) and patient mortality (HR 1.82; 95% CI: 1.14–2.86), respectively.

Discussion

This study, comprised of a large national sample of pediatric patients with ESRD, demonstrated significant graft and patient survival benefits of preemptive transplantation, regardless of donor source. Among 7,527 pediatric kidney transplant recipients over the 13-year study period, 22.2% were transplanted preemptively, 17.5% of patients experienced graft failure and 4.4% died. Compared with children transplanted preemptively, children who received any dialysis prior to transplant experienced much higher rates of graft failure (HR 1.32; 95% CI: 1.10–1.56) and death (HR 1.69; 95% CI: 1.22–2.33), even when accounting for demographic, clinical, and transplant factors. In multivariable models, graft survival benefits among preemptive transplant recipients were most striking compared with children who were on dialysis for more than one year; these results remained statistically significant when stratified by donor source. Similarly, mortality benefits of preemptive transplantation remained substantial and statistically significant when preemptive transplant was compared with dialysis exposure > 18 months.

In the pediatric literature, various studies have documented equivalent outcomes or modest survival benefits for preemptively transplanted pediatric patients, although the majority have been small single institutional studies.16–22,24,26 Three larger studies demonstrated better outcomes with preemptive transplantation, but with mixed findings. In 2000, Vats et al published a study examining a group of 2495 North American pediatric renal transplant recipients, 625 of whom were preemptively transplanted, and found that pre-transplant dialysis did not alter outcomes in DD kidney transplant recipients but did shorten long-term graft survival in LD kidney transplant recipients.24 Cransberg et al examined a group of 1111 European pediatric patients, 156 of whom were preemptively transplanted from 1990–2000 and found the opposite effect: there was no benefit in avoiding dialysis prior to LD transplant but there was improved graft survival for preemptive DD transplant, although this effect disappeared in the second half of the study decade.17 Finally, in the largest study, Butani et al examined an OPTN database of 3606 pediatric renal transplants, 28% of which were preemptive (n=1003).22 The one-year acute rejection rate was lowest in the preemptive group, but avoiding dialysis only conferred a decreased risk of graft failure following LD transplant, not DD transplant. Our study is the largest to date, analyzing over 7,500 pediatric renal transplant recipients with over 1,600 receiving preemptive transplants. Here we show significant benefit for preemptively transplanted LD and DD allograft recipients for both graft longevity and decreased mortality. Although the adverse effects of dialysis are well recognized, only 22.2% of children in this cohort received preemptive transplantation. A recent USRDS Annual Data Report noted that only 37% of children overall received a kidney transplant within the first year of ESRD care.27

Although children with ESRD have significantly less exposure to dialysis than their adult counterparts with much shorter median waiting times, our study provides evidence that the impact of dialysis should not be minimized in children. Children with ESRD have mortality rates 30 times higher than children without ESRD.28 Given this substantial difference in life expectancy, dialysis exposure, however brief, has the potential for tremendous long-term cumulative negative effects. The five-year survival probability for children beginning dialysis is only 82% for both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis compared with 95% for transplantation.27 In addition, due to technical challenges of accessing vessels, 81% of incident pediatric ESRD patients start hemodialysis with a catheter, incurring higher risks of infection.27 Further, considering that current allograft half-life is 12–15 years,29 most patients transplanted in childhood will require re-transplantation during their lifetime. Thus, every effort should be made to ensure prolonged graft survival of a child’s initial transplant as well as preservation of vascular access for future dialysis and transplant opportunities.

In the history of transplantation in the US, both legislation and public opinion have supported priority allocation for children to reduce dialysis exposure and optimize the substantial health benefits of transplant in early life.30 In 1984, The National Organ Transplantation Act charged the Organ Procurement Transplantation Network to consider the unique healthcare needs of children in the design of the national allocation system.31 Prior to 2005, Children < 11 years of age received 4 additional points and 11–17 year olds received 3 additional points. In addition, allocation policies directly targeted minimizing dialysis exposure for children by providing additional allocation priority for children with extended waiting times.32 Extended waiting times were specified as: > 6 months after listing for pediatric candidates ≤ 5 years of age, > 12 months for those who were 6 to 10 years of age, and > 18 months for those 11 to 17 years of age. In 2005, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) altered the kidney allocation system again using the “Share 35” policy which prioritized pediatric candidates to receive organs from donors less than 35 years of age, however additional allocation priority based on extended pediatric waiting times was eliminated from the allocation scheme.33 More recently, the new Kidney Allocation System (KAS) was adopted in December 2014 in response to the growing disparity between organ supply and demand.34 KAS was intended to better align the quality of organs with quality of donors. In this system, pediatric patients are allocated organs in the groupings of higher quality organs (defined by Kidney Donor Profile Index, KDPI), however, once again no special consideration or weighting is given to children with extended dialysis waiting times. Although the KAS policy has not created a statistically significant disadvantage to pediatric access to transplant so far, pediatric transplant rates do appear to be declining.35 As organ demand continues to outpace supply, longer waiting times for children are likely inevitable unless policy modifications are adopted to specifically address minimizing pediatric dialysis exposure time.

Our study demonstrates substantial allograft and mortality benefits for children receiving DD or LD preemptive transplant compared with children who have any dialysis exposure, however benefits were most salient compared with dialysis exposure of 12–18 months. Clearly, the optimal treatment for children with ESRD is preemptive transplantation, however this is not always possible. Infants with ESRD must reach a reasonable weight (usually 10 kg) to successfully receive a transplant. Medical conditions, such as active nephrotic syndrome or lupus, may preclude preemptive transplantation. Although we are gaining insight into risk factors associated with renal disease progression in children with CKD25, evidence of nonlinear trajectories for disease progression make prediction models for optimal timing of RRT a remaining challenge.36 There are also no standardized criteria to guide transplant referral and evaluation practices specifically for children, creating tremendous practice variation with room for subjective interpretation of psychosocial “readiness”.37

The majority of pediatric preemptive kidney transplant occurs through living donation. Living donation enables more control over transplant timing. There have been widespread concerns that pediatric priority allocation for deceased donors has disincentivized living donation for children and indeed living donor rates for children have declined over time.27,38 The benefits of preemptive transplant noted in our study provide further evidence for providers to encourage living donation whenever possible. As deceased donor waiting times and the overall number of kidney transplant candidates increase, the benefits of living donation for timely preemptive transplantation will become even greater. Certainly children, just like adults, may not have eligible or willing donors. For those children who are unable to be preemptively transplanted with a LD, our study’s findings support clinical efforts and public policies to reduce waiting times for pediatric DD candidates.

These findings are an important step forward in understanding the benefits of preemptive transplantation and burdens of even short-term dialysis among children with ESRD. This is the largest national retrospective study examining preemptive pediatric renal transplantation to date. Although longer follow-up time and greater events will enable future studies to examine subgroup and stratified analyses, our results demonstrate a significant benefit to avoiding dialysis in pediatric ESRD patients both in terms of organ survival and mortality, regardless of donor source.

Methods

Study Population and Data Sources

Incident, pediatric (age < 18 years) ESRD patients identified from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) who entered the Medicare ESRD program between 2000 and 2012 were examined. Basic demographic data were obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence Form 2728, completed on all incident ESRD patients. Outcome data on transplantation were obtained from USRDS and are virtually 100% complete.39 Data on neighborhood poverty were obtained from Census 2000 by patient ZIP Code. There were a total of 8,552 pediatric (< 18 years) patients who received a transplant from January 1, 2000 through September 30, 2012. We excluded patients who had previously received a transplant (n=915), patients who received a multiple organ transplant during the study period (n=98), and those with a missing donor type (n=12). A total of 7,527 pediatric kidney transplant recipients were included in our analyses.

Study Variables

The primary outcomes of interest were death-censored graft failure, in which death with graft function was treated as graft failure, and mortality. The primary exposure variable was the receipt of a preemptive transplant (yes/no), defined as a transplant with no history of dialysis. Because recent studies have highlighted differences in pediatric recipients of living vs. deceased donor kidneys with respect to transplant access and general demographic and clinical characteristics, we also stratified analyses by donor source.40,41 In addition, since recent literature has suggested variation in pediatric waiting times, we examined time on dialysis (0–6 months, 6–12 months, 12–18 months, >18 months) 8. We considered the effects of race/ethnicity as a contextual and social, rather than a biologic determinant. 42 Demographic and clinical covariates examined included characteristics associated with both dialysis exposure and with the outcomes, including patient age, sex, race, etiology of ESRD, body mass index, insurance type, blood type, cold ischemia time, donor age, PRA calculated as the maximum of the peak PRA, calculated PRA, or class I or class II PRA values, HLA mismatch number and Share 35 policy era. We examined year of entry into the ESRD Medicare program to examine time trends over the decade. Health insurance at the time of transplant was categorized as private (employer), public (Medicaid, Medicare, Veteran’s Administration, or combination), other, or no health insurance.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests and t-tests (or non-parametric equivalents of the t-test) and exact statistics (when expected values of cell sizes were < 5) were used to examine differences between demographic and clinical characteristics of patients by race/ethnicity. To examine the multivariable-adjusted association of preemptive transplantation and outcomes of 1) death-censored graft failure and 2) mortality, Hazard Ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models separately by donor type. We tested for interaction between preemptive transplantation and donor type to determine whether the benefits of preemptive transplantation varied depending on whether a patient received either a DD or LD transplant. We performed a complete case analysis in the event of missing covariate data.

Secondary Analyses

We conducted several sub analyses. We excluded patients who were at risk of recurrence of kidney disease, including patients with FSGS and nephrotic syndrome, since these diagnoses are associated with a higher risk of graft failure compared to other etiologies of ESRD.43 We conducted a sub analysis in which we restricted the cohort to CAKUT only. We conducted a sub analysis in which we excluded patients < 2 years of age since those patients may have reduced ability to receive preemptive transplant. In addition, we further explored patients who received an early transplant by categorizing time on dialysis into fewer categories (0–6 months, 6–12 months, 12–18 months, and > 18 months) and compared outcomes among patients with preemptive and non-preemptive to reduce potential bias in classifying early transplant recipients with late transplant recipients (> 1 year dialysis). Finally, we analyzed transplantation pre- and post-Share 35, an allocation policy designed to earmark organs from younger donors to pediatric patients less than 18 years of age, to determine whether this would affect preemptive transplant rates or outcomes.44 Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant in analyses. All analyses were performed with SAS software (v9.2). The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Acknowledgments

S.A. is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K23DK083529 and R03DK099486. B.A.S. is partially supported by an American Society of Transplantation Translational Science Fellowship Award. R.E.P. is supported in part by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number ULl TR000454 and KL2TR000455 as well as R24MD008077 through the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The interpretation and reporting of the data presented here are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures.

None.

An early portion of this work was presented at the American Transplant Congress meeting in Seattle in May 2013.

References

- 1.Mange KC, Joffe MM, Feldman HI. Effect of the use or nonuse of long-term dialysis on the subsequent survival of renal transplants from living donors. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(10):726–731. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liem YS, Bosch JL, Arends LR, et al. Quality of life assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-Item Health Survey of patients on renal replacement therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2007;10(5):390–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation. [Accessed 7/7/13];Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov.

- 4.Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B. Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: a paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation. 2002;74(10):1377–1381. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier-Kriesche HU, Port FK, Ojo AO, et al. Effect of waiting time on renal transplant outcome. Kidney Int. 2000;58(3):1311–1317. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liem YS, Weimar W. Early living-donor kidney transplantation: a review of the associated survival benefit. Transplantation. 2009;87(3):317–318. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181952710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kallab S, Bassil N, Esposito L, et al. Indications for and barriers to preemptive kidney transplantation: a review. Transplant Proc. 42(3):782–784. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reese PP, Hwang H, Potluri V, et al. Geographic determinants of access to pediatric deceased donor kidney transplantation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2014;25(4):827–835. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavers BM, Solid CA, Daniels FX, et al. Hypertension in pediatric long-term hemodialysis patients in the United States. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2009;4(8):1363–1369. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01440209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shamszad P, Slesnick TC, Smith EO, et al. Association between left ventricular mass index and cardiac function in pediatric dialysis patients. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(5):835–841. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-2060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arbeiter AK, Buscher R, Petersenn S, et al. Ghrelin and other appetite-regulating hormones in paediatric patients with chronic renal failure during dialysis and following kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(2):643–646. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nissel R, Lindberg A, Mehls O, Haffner D. Factors predicting the near-final height in growth hormone-treated children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1359–1365. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasbury WC, Fennell RS, 3rd, Fennell EB, Morris MK. Cognitive functioning in children with end stage renal disease pre- and post-dialysis session. Int J Pediatr Nephrol. 1986;7(1):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Renal Data System. USRDS 2014 annual data report; Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harada H, Seki T, Nonomura K, et al. Pre-emptive renal transplantation in children. Int J Urol. 2001;8(5):205–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahmoud A, Said MH, Dawahra M, et al. Outcome of preemptive renal transplantation and pretransplantation dialysis in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11(5):537–541. doi: 10.1007/s004670050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cransberg K, Smits JM, Offner G, et al. Kidney transplantation without prior dialysis in children: the Eurotransplant experience. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(8):1858–1864. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flom LS, Reisman EM, Donovan JM, et al. Favorable experience with pre-emptive renal transplantation in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 1992;6(3):258–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00878362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nevins TE, Danielson G. Prior dialysis does not affect the outcome of pediatric renal transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 1991;5(2):211–214. doi: 10.1007/BF01095954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzwater DS, Brouhard BH, Garred D, Cunningham RJ, 3rd, et al. The outcome of renal transplantation in children without prolonged pre-transplant dialysis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1991;30(3):148–152. doi: 10.1177/000992289103000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuel SM, Tonelli MA, Foster BJ, et al. Survival in pediatric dialysis and transplant patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04920610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butani L, Perez RV. Effect of pretransplant dialysis modality and duration on long-term outcomes of children receiving renal transplants. Transplantation. 91(4):447–451. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318204860b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy SE, Mackie FE, Rosenberg AR, McDonald SP. Waiting time and outcome of kidney transplantation in adolescents. Transplantation. 2006;82(8):1046–1050. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000236030.00461.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vats AN, Donaldson L, Fine RN, Chavers BM. Pretransplant dialysis status and outcome of renal transplantation in North American children: a NAPRTCS Study North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study. Transplantation. 2000;69(7):1414–1419. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200004150-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Copelovitch L, Warady BA, Furth SL. Insights from the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):2047–2053. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10751210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Offner G, Hoyer PF, Meyer B, et al. Pre-emptive renal transplantation in children and adolescents. Transpl Int. 1993;6(3):125–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00336353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.USRDS. USRDS 2015 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States Renal Data System. Bethesda, MD: 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald SP, Craig JC Australian, New Zealand Paediatric Nephrology A. Long-term survival of children with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(26):2654–2662. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2013 Annual Data Report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2015;(15 Suppl 2):1–34. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ethical Principles of Pediatric Organ Allocation. Network OPaT, ed. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Organ Transplantation Act (NOTA) 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Policy 3.5.11.5: Pediatric Kidney Transplant Candidates. United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JM, Biggins SW, Haselby DG, et al. Kidney, pancreas and liver allocation and distribution in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(12):3191–3212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allocation of Kidneys. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massie AB, Luo X, Lonze BE, et al. Early Changes in Kidney Distribution under the New Allocation System. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015080934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong Y, Munoz A, Schwartz GJ, et al. Nonlinear trajectory of GFR in children before RRT. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2014;25(5):913–917. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shellmer D, Brosig C, Wray J. The start of the transplant journey: referral for pediatric solid organ transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18(2):125–133. doi: 10.1111/petr.12215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agarwal S, Oak N, Siddique J, et al. Changes in pediatric renal transplantation after implementation of the revised deceased donor kidney allocation policy. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(5):1237–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U S Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patzer RE, Sayed BA, Kutner N, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Pediatric Access to Preemptive Kidney Transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ajt.12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patzer RE, Amaral S, Klein M, et al. Racial disparities in pediatric access to kidney transplantation: does socioeconomic status play a role? Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones CP. Invited commentary: “race,” racism, and the practice of epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(4):299–304. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.299. discussion 305–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiffel J, Rahimzada Y, Trachtman H. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and chronic kidney disease in pediatric patients. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2011;18(5):332–338. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amaral S, Patzer RE, Kutner N, McClellan W. Racial disparities in access to pediatric kidney transplantation since share 35. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2012;23(6):1069–1077. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011121145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]