Abstract

Introduction:

We report the case of a multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) with initial renal involvement. Although the renal involvement in this case was typical of MCD, it constitutes a rare presentation of the disease, and in our case the renal manifestations led to the haematological diagnosis.

Clinical Findings/Patient Concerns:

The patient was admitted for fever, diarrhea, anasarca, lymphadenopathies and acute renal failure. Despite intravenous rehydration using saline and albumin, renal function worsened and the patient required dialysis. While diagnostic investigations were performed, right hemiplegia occurred. There was no anemia or thrombocytopenia.

Diagnoses:

Kidney biopsy was consistent with glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Lymph node histology was consistent with hyalin-vascular variant of Castleman disease.

Outcomes:

Given the renal and neurological manifestations of this MCD-associated TMA, the patient was treated with plasma exchange during one month, and six courses of rituximab, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone. The evolution was favorable.

Conclusion:

Although rare, this diagnosis is worth knowing, as specific treatment has to be started as soon as possible and proved to be efficient in our case as well as in other reports in the literature.

Keywords: idiopatic multicentric castleman disease, renal failure, thrombotic microangiopathy

1. Introduction

Idiopatic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder associated with a wide clinical spectrum. Severe cases can be associated with vascular leak syndrome with anasarca, pleural effusions, and ascites, organ failure, and even death. Kidney involvement, as well as neurological involvement, is not typical. We herein report a case of thrombotic microangiopathy with kidney and neurologic involvement, without biologic manifestation, leading to the diagnostic of iMCD.

2. Consent

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

3. Case report

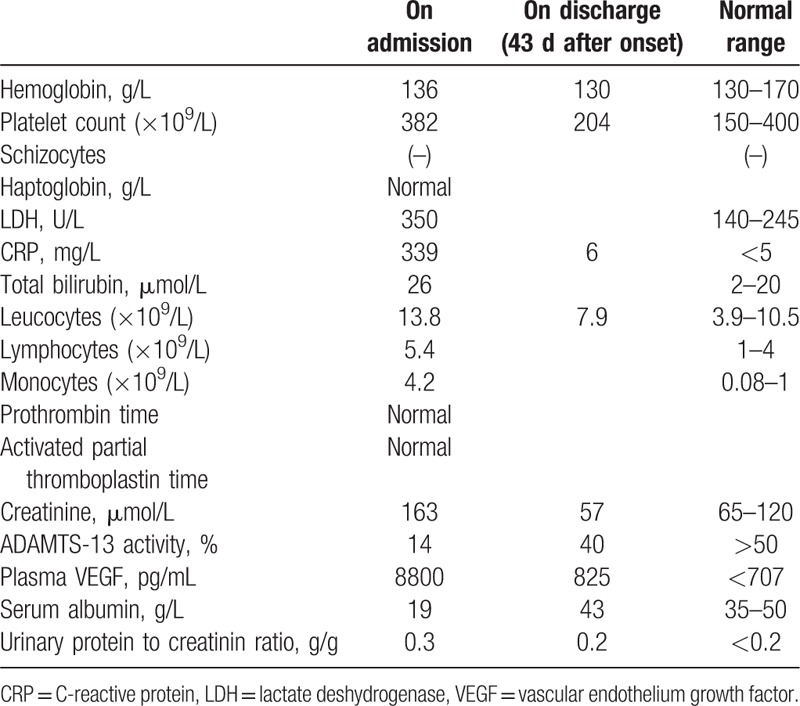

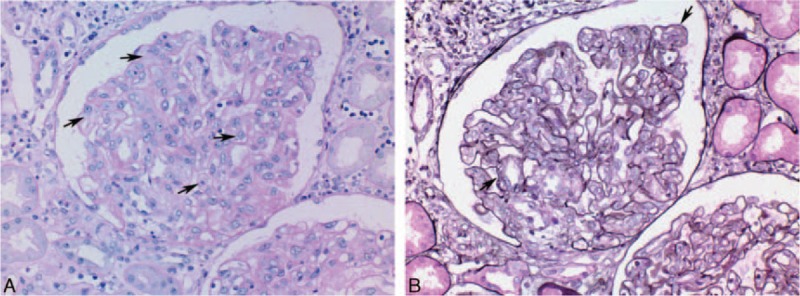

A 54-year-old patient was admitted for fever, diarrhea, and acute renal failure. He had no significant medical history, did not take any medication, and had not traveled recently. He had no relevant familial history. Fifteen days before his admission, he developed fever, fluctuant rash, diarrhea, and pain in the joints. On admission, blood pressure was 140/70 mm Hg, temperature 39°C. Physical examination showed severe edema involving both lower and upper limbs, as well as ascites and pleural effusion. Cervical and axillar infracentimetric lymphadenopathies were present, together with hepatosplenomegaly, confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan. Bilateral arthritis of the ankles resolved spontaneously. Blood analysis revealed (Table 1): leukocytosis, normal hemoglobin and platelet levels with no biologic sign of hemolysis, elevated C-reactive protein, low albumin, elevated serum creatinin, mild proteinuria and no hematuria. Despite intravenous rehydration using saline and albumin, renal function worsened and the patient required dialysis. While diagnostic investigations were performed, hemiplegia occurred: brain MRI showed multifocal ischemic lesions. Echographic and rythmologic studies ruled out any cardiologic cause for the stroke. A renal biopsy was performed (Fig. 1A and B). Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining showed endotheliosis in all glomeruli (Fig. 1A, arrows), associated with mesangiolysis and double contours on silver staining (Fig. 1B, arrows), and no arteriolar thrombus. A moderate CD20+ B lymphocyte infiltrate was present in the interstitium, with a peritubularcapillaritis. Immunofluorescence study did not show any deposit. Lymph node biopsy (Fig. 2A and B) showed abnormal follicles with hyalinization of germinal center, and an onion-skin aspect of the mantle zone.

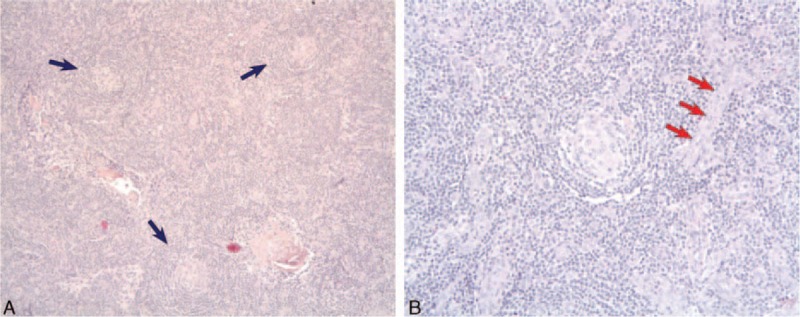

Table 1.

Laboratory results.

Figure 1.

A, Renal biopsy, PAS staining showing endotheliosis in all glomeruli (arrows). B, Renal biopsy, silver staining showing mesangiolysis and double contours (arrows). PAS = Periodic acid–Schiff.

Figure 2.

A, Lymph node histology shows 3 abnormal follicles with hyalinization of germinal center, and an onion-skin aspect of the mantle zone (blue arrows) consistent with hyalin-vascular variant of Castleman disease. B, Higher magnification, centered on the follicle. Blood vessels (red arrows) are visible and are also characteristic of the diagnosis.

Clinical presentation and lymph node histology were consistent with hyaline-vascular multicentric Castleman disease (MCD). HIV and HHV-8 serology, as well as HHV-8 lymph node tissue staining, were negative. Serum vascular endothelium growth factor (VEGF) was highly elevated. There was no biologic manifestation of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), but the renal biopsy and brain MRI were consistent with glomerular and neurologic TMA lesions. No other apparent cause of thrombotic microvascular involvement was noted. Notably, there was no evidence for infection with shiga toxin-producing germs, ADAMTS-13 activity was decreased up to 14% but remained above 5%, and the alternative complement pathway was normal.

Plasma exchange was initiated due to the kidney histological lesions and the multifocal ischemic brain lesions. It was discontinued after 1 month after the onset of the disease, since the patient's condition remained stable. Furthermore, chemotherapy including 6 courses of rituximab (375 mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2), and dexamethasone (40 mg/day from day 1 to day 4) was started together with plasma exchanges (chemotherapy was performed immediately after plasma exchanges). Courses were performed every 3 weeks. Clinical manifestations of vascular leak syndrome regressed, renal function normalized, and serum VEGF level decreased to 825 pg/mL after 1 course of chemotherapy. The patient was discharged 43 days after admission. No neurological event occurred after initiating the treatment. Thoraco-abdominal CT scan was performed after 6 courses of chemotherapy, showing a normal liver and spleen size and no lymph node enlargement. One year after the diagnosis, remission of MCD is persistent and plasma creatinine is 86 μmol/L, with no proteinuria.

4. Discussion

Castleman disease has been first reported by Benjamin Castleman, who described the typical angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia. CD may be unicentric, associated with local symptoms and a high cure rate with surgical excision, or multicentric, with systemic inflammation, vascular leak syndrome with anasarca, hypoalbuminemia, and multiple organ failure. MCD was recently separated into 2 types: HHV-8-induced MCD, usually diagnosed in HIV-infected patients, and HHV-8-negative MCD, referred to as idiopathic MCD (iMCD), which has an uncompletely understood pathophysiology.[1] A common feature of MCD is hypercytokinemia, notably IL6, which induces polyclonal B-cell and plasma cell proliferation, VEGF secretion, and angiogenesis. Human-IL6 transgenic mice produces a phenotype resembling human MCD.[1] Three different disease mechanisms have been hypothesized to be responsible for driving iMCD hypercytokinemia: autoinflammatory mechanisms, paraneoplastic ectopic cytokine secretion, and viral signaling by a non-HHV-8 virus. POEMS syndrome (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes) can also share clinical and histopathological overlap with iMCD, since 37% to 60% of POEMS cases have elements of CD histopathology.[1]

Treatment of iMCD relies on different strategies.[1] An anti-inflammatory therapy, using corticosteroids, is often useful during acute exacerbations of iMCD but is associated with frequent relapses during tapering.[2] Rituximab is frequently used as a first-line or second-line treatment for iMCD, and although has been shown to induce remission in this disease, it is frequently only partially effective.[3] Cytotoxic chemotherapies, such as cyclophosphamide, also induce response in the most severe cases, but side effects are severe with these agents.[4] More recently, monoclonal antibodies directly targeting IL-6 such as Siltuximab have been evaluated as a treatment for iMCD. A randomized, placebo-controlled study showed that in HIV and HH8-negative MCD, Siltuximab plus best supportive care was superior to best supportive care alone for patients with symptomatic iMCD and was well tolerated.[5] A long-term safety analysis showed that after a median period of 5 years, patients who continued to receive Siltuximab showed sustained disease control with no evidence of cumulative toxicity. This targeted therapeutic approach therefore constitutes a promising strategy in the treatment of iMCD.[6]

Renal involvement was reported in 25% to 54% of cases[7,8] of CD. Small vessel lesions with thrombotic microangiopathy features are typical of renal involvement in HIV-negative MCD. In 2 retrospective studies of renal biopsies in HIV-negative CD,[7,8] TMA accounted for 15 of 26 cases. This renal involvement was similar to the lesions seen in POEMS syndrome. The other renal histologic lesions of MCD included tubulointerstitial disease (3/26), crescentic glomerulonephritis (4/26), AA amyloidosis (3/26). Downregulation of podocyte VEGF expression has been observed in MCD-associated TMA,[7] and could be involved in the pathophysiology of these renal lesions. In fact, endothelial swelling and capillary-loop double contours observed in our patient are reminiscent of renal lesions seen in preeclampsia (relative to soluble Flt1 that blocks VEGF signaling) and during anti-VEGF antibody therapy.[9] Moreover, in mice, downregulation of podocyte VEGF is sufficient to induce renal TMA.[9] However, the exact link between CD and loss of glomerular VEGF expression remains to be elucidated. Besides, MCD-associated TMA may also be relative to thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. London et al[10] recently reported 4 cases with TMA, associated with HHV8-related MCD, 1 of them being HIV-negative. In all cases, ADAMTS-13 activity was below 5% and there were hematological manifestations of TMA.[10]

5. Conclusion

We herein report the case of a 54-year-old man who was diagnosed with MCD with initial renal involvement that led to the hematologic diagnosis. The renal involvement in this case was typical of MCD. Although rare, this diagnosis is worth knowing, as specific treatment has to be started as soon as possible and proved to be efficient in our case as well as in other reports in the literature.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CRP = C-reactive protein, CT = computed tomography, HHV8 = human herpes virus type 8, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, IL6 = interleukine 6, iMCD = idiopatic multicentric Castleman disease, LDH = lactate deshydrogenase, MCD = multicentric Castleman disease, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, TMA = thrombotic microangiopathy, VEGF = vascular endothelium growth factor.

AF, MV, MR, AH, L-HN, DC, BK, FS, KE-K performed the research, and AF, MV, KE-K wrote the paper.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Fajgenbaum DC, van Rhee F, Nabel CS. HHV-8-negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis, and therapy. Blood 2014; 123:2924–2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frizzera G, Peterson BA, Bayrd ED, et al. A systemic lymphoproliferative disorder with morphologic features of Castleman's disease: clinical findings and clinicopathologic correlations in 15 patients. JCO 1985; 3:1202–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ide M, Kawachi Y, Izumi Y, et al. Long-term remission in HIV-negative patients with multicentric Castleman's disease using rituximab. Eur J Haematol 2006; 76:119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chronowski GM, Ha CS, Wilder RB, et al. Treatment of unicentric and multicentric Castleman disease and the role of radiotherapy. Cancer 2001; 92:670–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rhee F, Wong RS, Munshi N, et al. Siltuximab for multicentric Castleman's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15:966–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fajgenbaum DC, Kurzrock R. Siltuximab: a targeted therapy for idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Immunotherapy 2016; 8:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Karoui K, Vuiblet V, Dion D, et al. Renal involvement in Castleman disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26:599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu D, Lv J, Dong Y, et al. Renal involvement in a large cohort of Chinese patients with Castleman disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27 (suppl 3):iii119–iii125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eremina V, Jefferson JA, Kowalewska J, et al. VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1129–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.London J, Boutboul D, Agbalika F, et al. Autoimmune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with HHV8-related multicentric Castleman disease. Br J Haematol 2016; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]