Abstract

The interaction of liposomal membranes composed of soybean phosphatidylcholine with the bile salts (BSs) cholate (Ch), glycocholate (GC), chenodeoxycholate (CDC), and glycochenodeoxycholate (GCDC) was studied. The BSs differed with regard to their lipophilicity, pKa values, and the size of their hydrophilic moiety. Their membrane interactions were investigated using Laurdan as a membrane-anchored fluorescent dye. The apparent membrane/water partition coefficient, D, at pH 7.4 was calculated from binding plots and compared with direct binding measurements using ultracentrifugation as a reference. The Laurdan-derived LogD values at pH 7.4 were found to be 2.10 and 2.25 for the trihydroxy BSs, i.e., Ch and GC, and 2.85 and 2.75 for the dihydroxy BSs, i.e., CDC and GCDC, respectively. For the membrane-associated glycine-conjugated GC and GCDC (pKa values of ∼3.9), no differences in the Laurdan spectra of the respective BS were found at pH 6.8, 7.4, and 8.2. Unconjugated Ch and CDC (pKa values of ∼5.0) showed pronounced differences at the three pH values. Furthermore, the kinetics of membrane adsorption and transbilayer movement differed between conjugated and unconjugated BSs as determined with Laurdan-labeled liposomes.

Introduction

Liposomes can be used as simple model systems to mimic biomembranes due to their structural similarity. This makes them useful for estimating membrane partition coefficients, which are biologically more relevant than such values obtained by means of the oversimplified octanol/buffer system (1, 2). As would be expected, these partition coefficients can differ by some orders of magnitude (3).

Several tools are available for estimating drug partitioning in model membranes (4). In direct methods, the membrane-bound drug must be separated from the free drug in equilibrium with the membrane and then quantified. Indirect methods detect changes in spectral or other properties of the drug or the liposomal membrane after drug binding. Thus, they offer the advantage of not requiring further separation and analytical steps.

The fluorescent probe 6-dodecanoyl-2-di-methylaminonaphthalene (Laurdan) has been extensively used as an optical sensor for monitoring structural changes and lipid order in membranes (5, 6, 7). The fluorophore of Laurdan is known to reside at the glycerol backbone in the phospholipid membrane. Its spectral behavior is very complex (8, 9). It has been reported to be mostly independent of the type of the lipids’ polar headgroup and pH, within the range of 4–10, but strongly affected by the polarity of its environment (7, 9, 10). The intensity and wavelength of the fluorescence maximum of the probe are also dependent on the packing density of the membrane, and therefore can be used to determine the gel to liquid-crystalline phase transition behavior (11, 12, 13).

Earlier studies introduced Laurdan to study the interaction of nonionic detergents with liposomal membranes (14, 15, 16, 17). Lipid/buffer partitioning was determined in membranes and mixed micelles. In this work, we used this method to detect the lipid/buffer partitioning of bile salts (BSs) as weakly acidic detergents at different concentrations and pH levels. The sodium salts of the bile acids used in this study—cholic acid (Ch), glycocholic acid (GC), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDC), and glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDC)—differ in their lipophilicity, pKa values, and the size of their hydrophilic moiety (Fig. 1). The results obtained with Laurdan for Ch, CDC, and GCDC at pH 7.4 were compared with those obtained using a direct method in which membrane-bound BSs were separated from free BSs by ultracentrifugation (18). Furthermore, Laurdan offers the possibility of following the kinetics of BS membrane adsorption and transbilayer movement (19). This is important for understanding the impact of the conjugation of BSs (e.g., with glycine) in the liver, lowering the pKa of the BSs, and preventing their reabsorption in the upper small intestine.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure and pKa values of the BSs used in this work. The trihydroxy compounds Ch and GC are more hydrophilic than the dihydroxy compounds CDC and GCDC. The pKa values depend only on conjugation.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals for the ultracentrifugation method

Pure egg phosphatidylcholine (EPC) was purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). Soybean PC (SPC) was a generous gift from Lipoid (Ludwigshafen, Germany). The sodium salt of Ch was obtained from Serva (Heidelberg, Germany), and the sodium salts of GCDC, CDC, and GC were obtained from Calbiochem (Bad Soden, Germany). Radioactively labeled PC [dipalmitoyl-1-14C]- and [2-palmitoyl-9,10-3H]-L-α-dipalmitoyl-phosphatidylcholine, as well as labeled BSs ([2,4-3H]-cholic acid and [carboxyl-14C]-chenodeoxycholic acid), were obtained from NEN (Dreieich, Germany). [3H]-glycochenodeoxycholic acid was obtained from Amersham (Braunschweig, Germany).

Experiments using the direct method were performed in a phosphate buffer with the following composition: Na2HPO4 10 mM; NaCl 150 mM, pH 7.4 (adjusted with HCl).

Chemicals used for the Laurdan method

SPC was a generous gift from Lipoid (Ludwigshafen, Germany). N,N-dimethyl-6-dodecanoyl-2-naphtylamine (Laurdan) was purchased from Fluka (Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland). Sodium GCDC, sodium CDC, sodium Ch, and sodium GC were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Chloroform (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), methanol (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), HEPES (Pufferan; Carl Roth), NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), and NaOH (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), as well as all other products utilized, were used without further purification.

Experiments using the Laurdan method were performed in a buffered solution with the following composition: HEPES, 10 mM and NaCl 150 mM, pH 6.8, 7.4, or 8.2 (adjusted with NaOH), depending on the experiment.

Liposome preparation

Preparation for the ultracentrifugation method

EPC liposomes that were exclusively unilamellar were prepared according to a previously described method for fast and controlled dialysis of mixed detergent/lipid micelles (20, 21) using sodium Ch as a detergent. Lipid and Ch at a molar ratio of 0.6 were dissolved together in methanol. For every 100 μmoles of lipid, 10 kBq (0.27 μCi) of 14C- or 3H-labeled lipids was added, depending on the radioactive BS used for double labeling. The solvent was removed completely under reduced pressure and the dry lipid/detergent mixture was dissolved in phosphate buffer. The final lipid concentration was 17 mmolal (see below). Next, 7.5 mL of each clear mixed micelle solution was dialyzed for 24 h against a continuous flow of phosphate buffer with the use of a Lipoprep apparatus (Dianorm, Munich, Germany) and a highly permeable dialysis cellulose membrane (Dianorm) with a cutoff of 10,000 Da.

Parallel experiments showed that the removal of detergent via dialysis was efficient. With 3H-labeled Ch, the residual concentration of detergents after 24 h was negligible (<1 molecule of detergent per 200 lipid molecules).

Preparation for the Laurdan method

Liposomes were prepared as described previously (22, 23) via the film method and successive extrusion. SPC and Laurdan (0.2 mol % of total lipid) were dissolved in methanol and chloroform, respectively. The solvents were removed with a rotary evaporator at 40°C, followed by fine vacuum for 1 h. The dried lipid film was dispersed at a molal concentration of 25 mmol·kg−1 HEPES buffer containing 10 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethansulfonic acid) and 150 mM NaCl (pH 6.8, 7.4, or 8.2 depending on the experiment). The dispersion was then extruded through polycarbonate membranes (Nuclepore, Pleasanton, CA) with pore sizes of 0.2 and 0.08 μm using a hand extruder (LiposoFast; Avestin, Ottawa, Canada).

The exact concentration of lipids was determined as inorganic phosphorus after the phospholipids of the samples were washed with H2SO4 and H2O2 (24). The size (z-average) and size distribution (polydispersity index) of the liposomes was measured by photon-correlation spectroscopy (Zetamaster S, automatic analysis option; Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The size of the liposomes was found to be between 95 and 108 nm, and the polydispersity was between 0.055 and 0.085. The average lamellarity was estimated with 31P-NMR using Pr(NO3) as a shift reagent (25, 26, 27) and the mean lamellarity was found to be 1.20–1.28. Since Laurdan is photosensitive, all experiments were performed under light protection.

Membrane binding of BSs

Ultracentrifugation and dialysis method (direct method)

At BS concentrations that were below the onset of membrane solubilization, the membrane-bound and free parts of BSs were separated via ultracentrifugation. To this end, 1.8 mL of radioactively labeled BS solutions of different concentrations and 0.2 mL of liposomes were well mixed to a final lipid concentration of 0.75 mM, mixed well, and ultracentrifuged in 4 mL polycarbonate tubes (140,000 × g, 210 min, 25°C; L5-75, rotor Ti 50.3 or 50.4; Beckman Coulter, Munich, Germany). The concentrations of the free BSs were determined in the supernatants by liquid scintillation counting.

As long as no membrane solubilization occurred, no radioactively labeled phospholipid (counterlabeled to BS) in the supernatant was detected, indicating no separation of smaller liposomes or mixed micelles from the initial liposomes. At BS concentrations high enough to lead to membrane solubilization, the separation of free BSs was performed by equilibrium dialysis at room temperature with cellulose membranes (Dianorm) that were impermeable to liposomes and mixed micelles (cutoff: 10,000 Da). The dialysis chamber was rotated for 4 h in an apparatus obtained from Dianorm, and the free BS concentration in one chamber was subtracted from the total BS concentration in the other chamber to obtain the bound portion.

Laurdan method (indirect method)

Fluorescence measurements were performed on an LS 50B luminescence spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Concentration-dependent BS-membrane interactions were determined by mixing 1 mL of the liposomal preparation with 1 mL of the corresponding BS dilution. To achieve high accuracy of the lipid and BS concentrations, samples were prepared by mixing the weighted stock solutions of liposomes, BSs, and buffer. Therefore, the resulting concentrations were first calculated as the molality b (moles per kilogram of solvent). In the highly diluted solutions and at constant temperature, the molal concentration was essentially equal to the molar concentration c (moles per liter of solution), which was used in the experiments described below.

The samples were incubated for 2 h at 25°C. Then the emission spectra were recorded at 25°C under slow magnetic stirring at an excitation wavelength (λexc) of 355 nm and emission wavelengths (λem) between 400 and 525 nm (scan speed 100 nm/min).

Each of five dilutions of the Laurdan-labeled liposomes with final lipid concentrations between 0.25 and 1.35 mM were incubated with various BS concentrations ranging from 0 mM to higher concentrations than their corresponding membrane-solubilizing concentration. Onset of solubilization was detected in parallel experiments by a decrease in light scattering using photon correlation spectroscopy (Zetamaster S; Malvern Instruments) after 2 h of incubation (rapid mode, one measurement, 200 μm aperture). The metered count rate was converted to the relative scattered light intensity.

For a kinetic analysis of changes in membrane structure, fluorescence was recorded at λexc = 355 nm and λem = 487 nm and 434 nm for 30–120 min (integration time: 0.5 s, shortest data interval) and the ratio of the two emission wavelengths (membrane state parameter (MSP); see below) was automatically calculated. For these experiments, 1 mL of the respective BS solution, at concentrations up to those that led to complete membrane solubilization, was added to 1 mL of the liposomal dispersion in the cuvette and thoroughly mixed, and the measurement was started directly. The final concentration of lipid in the cuvette was 1.0 mM.

Results

BS/membrane partitioning measured by radioactive labeling

Radioactive labeling of BSs and lipids offers the possibility of determining the binding parameters of BSs to lipids. By separating free from membrane-associated detergent by ultracentrifugation, equilibrium dialysis, or gel chromatography, one can obtain direct access to the association constants, binding sites, and partition coefficients in intact liposomes and in mixed micelles (18, 28, 29). Because the data for the membrane-bound BS portion can be acquired directly, we used this method as a reference in this study to evaluate the usefulness of the Laurdan fluorescence method.

3H or 14C radioactively labeled BSs at different concentrations were incubated with 14C- or 3H-labeled EPC liposomes (0.75 mM lipid) for 15 min at pH 7.4 and 25°C. Liposomes were then pelleted by ultracentrifugation for 3.5 h. The membrane-associated BS fraction could then be calculated from the known amount of total BS and lipid, and the measured free BS concentration in the supernatant:

| (1) |

where cb, ctot, and cfree represent the membrane-bound, total, and free molar concentrations of BSs, respectively, in one defined sample volume.

The membrane-bound fraction can be described by the effective molar ratio Re of bound detergent (30, 31):

| (2) |

where nb and nL represent the moles of bound detergent and lipid, respectively, and cL is the molar lipid concentration.

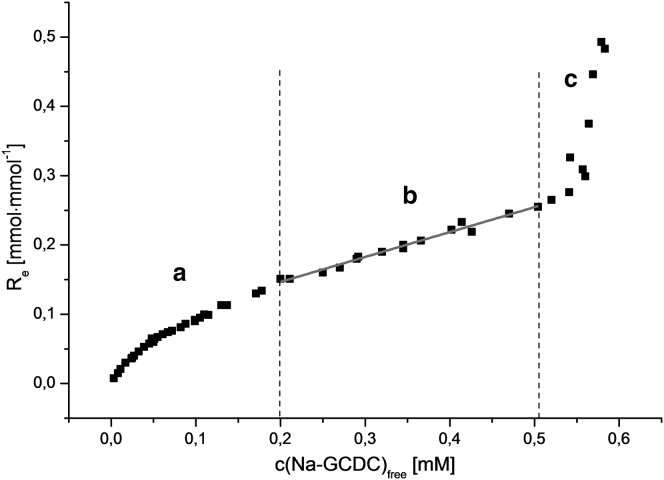

To determine the membrane/water partition coefficients of BSs, we focused on the detergent/lipid mixed membranes at detergent concentrations below the appearance of coexisting mixed micelles. Fig. 2 shows an example of a binding diagram for a concentration range of GCDC up to the point where membrane solubilization begins, as indicated by the occurrence of radioactively labeled phospholipid in the supernatant.

Figure 2.

Binding diagram of GCDC at pH 7.4, 25°C, measured by separating free and liposome-associated BS by ultracentrifugation and equilibrium dialysis. (a) Initial section from which the binding parameters were determined. (b) Linear section from which membrane partitioning was determined (R = 0.9904). (c) Coexistence of membranes and mixed micelles.

The binding behavior of BSs can be divided into three sections (29). From the initial binding to detergent-poor membranes (section a), a defined surface binding site can be determined by transferring the data to Scatchard plots. The association constant and the number of lipids involved in BS binding can be calculated from the essentially linear initial section of the Re/cfree versus Re if the data show only small levels of standard deviation. This was done elsewhere for particular combinations of BS species and lipid compositions (28). With increasing concentrations of BSs, the membrane-adsorbed detergent molecules insert deeper into the membrane and thus partition between the lipophilic phase and the buffer (section b). This is the essential section of the binding curve for determining the partition coefficient. In section c, after the onset of membrane solubilization, mixed membranes and mixed micelles coexist, until at high BS concentrations (not shown) all membrane lipids are solubilized into mixed micelles. The actual slope of the curve in section b is the lipid-normalized apparent membrane distribution coefficient, DL (L·mol−1), which is a measure for the partition coefficient of both protonated and deprotonated BSs between the membranes and the aqueous phase:

| (3) |

For better comparability with other definitions of distribution coefficients, DL can be converted (32) to a dimensionless apparent distribution coefficient, D:

| (4) |

where cw is the molar concentration of water at 25°C (55.4 mol·L−1), Mw is the molar mass of water (18.0 g·mol−1), and Ml is the mean molar mass of liposomal EPC or SPC (∼780 g·mol−1). Therefore, in this study, we calculated D from DL using a factor of 1.28 mol·L−1.

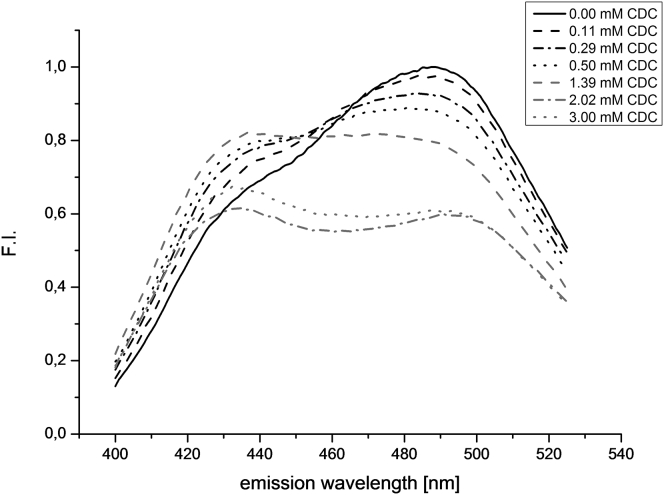

Emission spectra of Laurdan in plain and BS-containing liposomes

As shown in Fig. 3, the emission spectrum of Laurdan (0.2 mol %) in pure SPC vesicles at 25°C is asymmetric, characterized by a maximum at 487 nm and a shoulder at 434 nm. The standardized emission spectra of BS-free Laurdan liposomes at different pH values (pH 6.8–8.2) are identical, so the pH of the environment does not influence the spectral properties of Laurdan in mere SPC membranes (data not shown). The addition of a BS to the Laurdan-labeled liposomes leads to changes in the emission spectra, as can be seen in the example of CDC at pH 7.4 (0.25 mM lipid; Fig. 3). Upon addition of low BS concentrations, i.e., below the onset of membrane solubilization, the fluorescence intensity at the shoulder increases, whereas it decreases at the maximum. At ∼455 nm there is an isoemissive array where the fluorescence intensity remains essentially constant upon chemical and physical changes of the system. In the presence of very high BS concentrations, the isoemissive array disappears gradually and the fluorescence intensities at both the maximum and the shoulder show a decrease. At BS concentrations far above the onset of solubilization (see Fig. 3, CDC, mM), two maxima are found at 434 nm and 494 nm. Here, the emission spectrum seems to be influenced by the increasing occurrence of mixed micelles.

Figure 3.

Emission spectra of Laurdan-labeled SPC liposomes (0.24 mM lipid) upon increasing CDC concentrations below and above the point of onset of membrane solubilization between 1.4 and 2.0 mM CDC (pH 7.4, 25°C).

These fluorescence emission spectra indicate that Laurdan, which is anchored in either the lipid bilayer or in lipid/BS aggregates, shows a sensitive spectral response to an increasing phospholipid-associated detergent fraction Re (see Eq. 2), which causes changes in the polarity as well as the mobility of the probe environment.

Evaluation of the spectra

To quantify the spectral changes of Laurdan upon the absorption of BSs to lipid membranes, we use the MSP, which is defined as the ratio of the fluorescence intensities, F.I.487nm at the maximum and F.I.434nm at the shoulder (19):

| (5) |

The MSP assigns a given membrane condition in the headgroup region at a defined temperature to a numerical value. The value is governed by the amount of BS bound per lipid, as well as by the membrane association depth. A basic assumption for further calculations is that liposomes with identical MSP values at varying BS concentrations and lipid concentrations have the identical membrane composition at the respective pH.

To improve compatibility between the different experiments, the measured MSP is divided by the MSPf of detergent-free SPC-Laurdan liposomes. The standardized MSP, MSPstd, minimizes deviations of the MSP between the different experiments due to small differences in liposome size and lipid or Laurdan concentrations:

| (6) |

Determination of partition coefficients

The data were evaluated as previously described by Heerklotz et al. (15, 16) and Paternostre et al. (17) for nonionic detergents, with slight modifications. The binding parameters of the anionic BSs to membranes were determined using the lipid concentration series (Fig. 4). Each horizontal line of particular MSPstd values at a defined pH value represents the same ratio of bound BSs per lipid for different lipid concentrations.

Figure 4.

Calculated MSPstd values versus total CDC concentration (pH 7.4, 25°C). The vertical dotted lines show an MSPStd of 0.8 with the corresponding total CDC concentration for lipid concentrations of 0.24, 0.69, and 0.92 mM.

With Eqs. 1 and 2, a linear correlation between ctot and cL is given as

| (7) |

from which the effective molar ratio Re can be calculated from the slope, and the concentration of the free BS is calculated from the intercept at the y axis. The correlation coefficients of these linear fits varied from 0.90 to 0.999 for CDC (0.96–0.999 for GCDC), whereas the correlation coefficients of the trihydroxy BS were lower (0.75–0.99) due to their weaker binding to the lipids. Fig. 5 shows the evaluation of the data using an example of seven different MSPstd values for the binding of CDC to SPC membranes.

Figure 5.

Data evaluation for defined MSPstd values, reflecting identical BS/lipid ratios in the membranes. According to Eq. 7, the free CDC is given by the intercept at the y axis (total CDC) and the effective ratio Re is given by the slope (pH 7.4, 25°C).

BS concentrations that caused a certain MSP were calculated by linear interpolation of the actually measured MSP/BS concentration values.

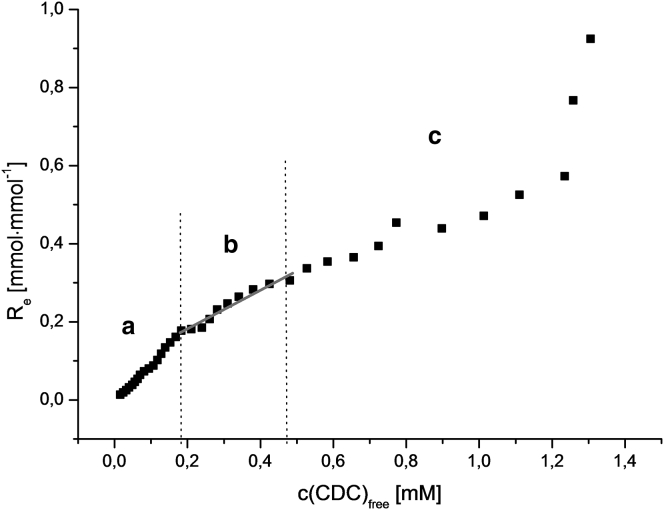

To create Fig. 6, from a large number of MSPstd values in Fig. 4 the corresponding lipid concentrations cL and total BS concentrations ctot were drawn as shown in Fig. 5. According to Eq. 7, Re and c(CDC)free were derived from the essentially linear plots and plotted in the binding diagram shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

Binding diagram of CDC at pH 7.4, determined with Laurdan-containing liposomes. The slope at each BS concentration is the lipid-standardized partition coefficient DL of the detergent between the membrane and buffer. (a) Initial section with very low BS bound to membrane. (b) Linear section from which membrane partitioning was determined (R = 0.9718). (c) Section of solubilization of membrane lipids to mixed micelles, as determined by the ultracentrifugation method.

The actual slope of the curve represents the lipid-normalized apparent membrane distribution coefficient DL (L·mol−1), as defined in Eq. 3. The three parts of BS membrane interaction correspond to the binding curve obtained by the direct method with radioactively labeled BSs (see Fig. 2). The upper limits of the linear part b of all BSs are based on solubilization experiments (light-scattering data not shown). The limits were set below the membrane-solubilizing concentrations of the respective BS.

Obviously, the direct method in Fig. 2 gives less noisy binding data than the indirect Laurdan method. Parallel experiments showed that the influence of the different buffer systems and different fluid PCs from egg yolk or soybean used was negligible. In the initial section (section a), the Laurdan data are not exact enough for a Scatchard analysis to calculate an association constant or the number of phospholipids surrounding one BS molecule in the membrane. In section c, a pronounced difference in the slopes found with the direct and Laurdan methods can be seen. With the equilibrium dialysis shown in Fig. 2, a steep increase of the slope above the onset of membrane solubilization was found. With the Laurdan fluorescence method, the slope is comparable to that obtained in section b up to higher BS concentrations. The differences between the two methods can be explained by the more complex changes that occur in the spectral behavior of Laurdan when mixed micelles and membranes coexist (see the emission spectra of Laurdan in Fig. 3).

In section b, which is the region of interest for determining the apparent BS partition coefficient in the intact membrane, the points of measurement received by the direct method show less deviation than the Laurdan method in the calculated linear regression. However, as shown in Table 1 for BSs that differ in lipophilicity (i.e., the number of hydroxy groups) and pKa values (with or without conjugated glycine) and the size of their hydrophilic moiety (i.e., the logD values) are comparable to, albeit somewhat lower than, those obtained with the Laurdan method.

Table 1.

Apparent Membrane/Buffer Partition Coefficients Determined with the Ultracentrifugation (Direct) or Laurdan (Indirect) Method

| BS | Direct Method (Ultracentrifugation) |

Indirect Method (Laurdan Method) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL [L·mol−1] | logDL | D | logD | DL [L·mol−1] | logDL | D | logD | |

| Ch | 51 ± 4 | 1.71 ± 0.03 | 66 ± 6 | 1.82 ± 0.04 | 98 ± 20 | 1.99 + 0.08/−0.10 | 126 ± 26 | 2.10 +0.08/−0.10 |

| CDC | 295 ± 25a | 2.47 ± 0.03a | 378 ±32a | 2.61 ± 0.03a | 547 ± 58 | 2.74 +0.04/−0.05 | 702 ± 74 | 2.85 +0.04/−0.05 |

| GC | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 137 ± 74 | 2.14 + 0.18/−0.34 | 176 ± 95 | 2.25 + 0.18/−0.34 |

| GCDC | 363 ± 11 | 2.56 ± 0.01 | 466 ± 14 | 2.67 ± 0.02 | 440 ± 43 | 2.64 ± 0.04 | 565 ± 55 | 2.75 ± 0.04 |

Values were obtained at pH 7.4, 25°C. DL, lipid-normalized apparent partition coefficient; D, dimensionless apparent partition coefficient; D = DL (L·mol−1) × 1.28 (mol·L−1) (see text); n.d., not determined.

Data from Möller (35).

According to Gouy-Chapman, electrostatic repulsion of anionic BS should contribute to the binding behavior to an increasingly negative membrane upon an increase in the membrane-associated BS fraction Re. This would result in a convex binding curve in part b. We could not find such repulsion with the ultracentrifugation method. However, with the charge-sensitive Laurdan, this effect may be more visible in the second part (part b). In this case, Fig. 6 could be alternatively fitted as a convex curve as well, in contrast to the calculated distribution coefficients in Table 1. The charge sensitivity of Laurdan may be one reason for the different binding curves obtained with the ultracentrifugation and fluorescence methods.

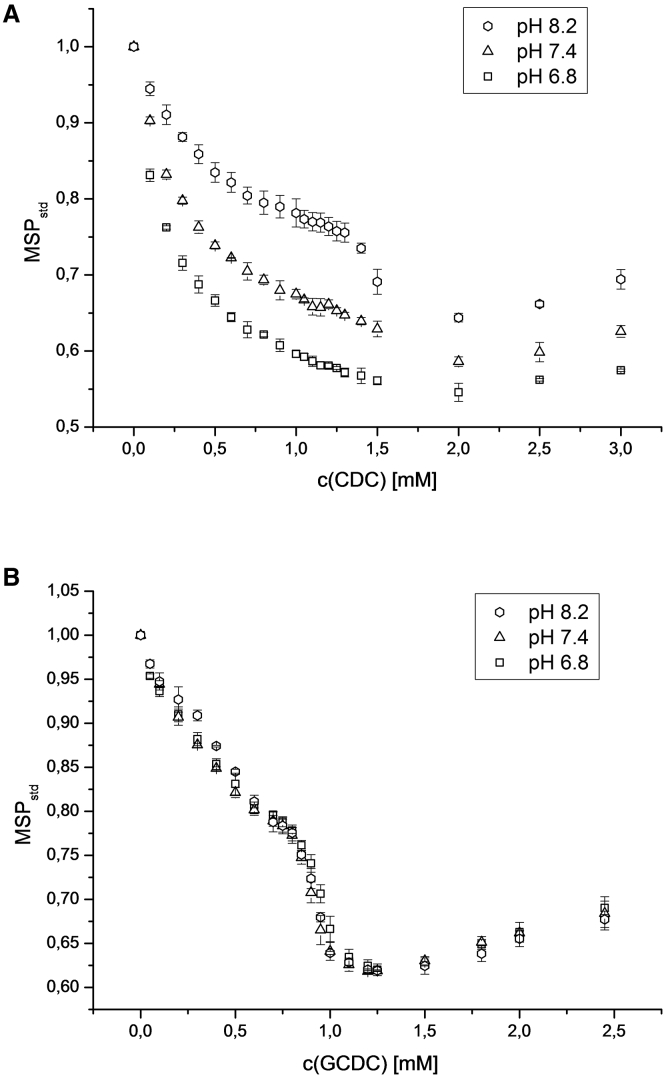

BS lipid association at different pH values

When the portions of the charged and uncharged BSs differ at a particular pH value, one expects to see different effects on the emission spectra of the membrane-anchored probe. Uncharged species will insert into deeper membrane regions and also insert into the membrane to a larger extent. For example, the different impacts on the MSPstd are shown in Fig. 7 for unconjugated CDC and the glycine-conjugated species GCDC at a constant lipid level of 0.25 mM. Although the nonconjugated BSs with pKa values of 5.0 ± 0.1 (33) exhibit only slight differences in their pH-dependent protonated, i.e., lipophilic, portion (0.063%, 0.40%, or 1.56% at pH 8.2, 7.4, or 6.8, respectively) when calculated according to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, they show pronounced differences in the course of the MSPstd values even at very low and increasing concentrations. This was also found to be true for unconjugated Ch (not shown) with approximately the same pKa value, with the difference that the onset of solubilization for this less lipophilic BS was found at concentrations above the onset for CDC. A direct influence of pH on the fluorescent probe could be excluded, as pointed out above. In this pH range, a difference in charge of the SPC membrane can also be considered to be negligible. Therefore, obviously only a small difference in the uncharged portion of the BSs is responsible for the pronounced differences in polarity of the membrane as seen when monitored by the Laurdan spectra. On one hand, this is caused by the much higher binding of uncharged species to lipid membranes. On the other hand, the binding depth of the BSs also has an influence on the Laurdan emission spectra. BSs that bind deeper into the membrane exert a greater influence on the fluorescent dye, which resides at the glycerol backbone of the phospholipids.

Figure 7.

MSPstd versus BS concentration at different pH values. (A) CDC. (B) GCDC. Lipid concentration of 0.25 mM, at 25°C.

In contrast, as shown in Fig. 7 B, the course of the MSPstd with increasing GCDC content in the membrane is essentially the same at the three pH values. This is explained by the fact that glycine conjugates with pKa values of 3.9 ± 0.1 have even lower and negligible protonated portions of these BSs at the respective pH values (0.005%, 0.03%, and 0.13% at pH 8.2, 7.4, and 6.8, respectively). The glycine-conjugated GC shows almost the same course for the curves (not shown) as in Fig. 7 B, but with an onset of solubilization occurring at higher concentrations.

The pronounced decrease of the slope at ∼0.7 mM GCDC correlates with the onset of solubilization determined via light-scattering measurements. The binding diagrams were normally examined above the solubilization concentration also in concentration areas where mixed micelles were assumed to predominate over intact liposomes (scattered light at 20–25% at 1 mM lipid).

An example of the binding curves obtained at different pH values and five different lipid concentrations is shown for CDC in Fig. 8. The values for the lipid-normalized apparent distribution coefficients of the dihydroxy BSs CDC and GCDC were calculated from the linear middle part (inset of the figure, representing section b in Fig. 6) of the curves and are summarized in Table 2. In contrast to the nonconjugated BS CDC, the lipid standardized partition coefficients remain essentially constant in the observed pH range of 6.8–8.2 for GCDC (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Binding diagrams of CDC at different pH values over a wide concentration range (at 25°C). Arrows: onset of membrane solubilization determined via scattered light measurements. Inset: enlarged version of the linear parts of the binding plots at different pH values, from which the apparent partition coefficients were calculated.

Table 2.

Apparent Partition Coefficients of CDC and GCDC at Different pH Values, Determined with the Laurdan (Indirect) Method

| CDC (pKa = 5.0) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Lipid-Normalized Apparent Distribution Coefficient |

Apparent Distribution Coefficient |

||

| DL [L·mol−1] | logDL | D | logD | |

| 6.8∗∗ | 912 ± 113 | 2.96 | 1170 ± 145 | 3.07 |

| +0.05/−0.06 | +0.05/−0.06 | |||

| 7.4∗∗ | 547 ± 58 | 2.74 | 702 ± 74 | 2.85 |

| +0.04/− 0.05 | +0.04/−0.05 | |||

| 8.2∗∗ |

559 ± 96 |

2.75 | 716 ± 123 |

2.85 |

| +0.07/− 0.08 | +0.07/−0.08 | |||

| GCDC (pKa = 3.9) | ||||

| 6.8∗ | 369 ± 59 | 2.57 | 472 ± 76 | 2.67 ± 0.07 |

| +0.06/−0.08 | ||||

| 7.4∗∗ | 440 ± 43 | 2.64 ± 0.04 | 563 ± 55 | 2.75 ± 0.04 |

| 8.2∗ | 435 ± 210 | 2.64 | 557 ± 269 | 2.75 |

| +0.17/−0.29 | +0.17/−0.29 | |||

n = 2.

n = 3.

Interestingly, even for the small portion of protonated CDC of 1.57% at pH 6.8, the apparent partition coefficient DL is ∼900 L⋅mol−1, which is much higher than that observed at pH 7.4 or 8.2. This is caused by the stronger and deeper binding of the neutral BS species to the lipid membrane.

Kinetics of the BS-liposome interaction

Influence of the BS concentration

It can be assumed that the association of BSs with the liposome bilayer occurs in two steps. First, the detergent molecules adsorb to the outer membrane monolayer, influencing the Laurdan probe in this layer or potentially in both lipid layers. In the second step, the BS molecules move through the membrane until an equilibrium between the two membrane leaflets is attained. Depending on the lipophilicity and/or charge of the BS, the rate of the transbilayer movement (flip-flop) varies, which can be followed by a spectral change of the probe molecules in the inner leaflet. Besides the flip-flop of the detergent, membrane destabilization, which starts to appear at concentrations below the onset of solubilization, is also indicated by a decrease of the MSP.

The adsorption and flip-flop kinetics for the different BSs were measured over a time period of 2 h. Without BSs, the MSPstd value remained constant at 1.0 over the whole time range, independently of the pH value (data not shown). Fig. 9 shows an example of the kinetics of the interaction of GCDC and CDC at pH 7.4 with increasing BS concentrations. Here, the first step of the initial membrane adsorption (i.e., the decrease of the MSP to the first detectable value) occurs very rapidly, within seconds, as can be seen by the sudden decrease of the MSPstd from 1.0 to a lower starting value for a further decrease. In the second step down to equilibrium, in the case of GCDC, the half-life of the essentially first-order kinetics of the MSPstd drops from ∼1 h at a low BS concentration of 0.4 mM to ∼2 min at the higher concentration of 2.0 mM (Fig. 9 A), which is far above the onset of membrane solubilization as detected by light scattering. This can be explained by the strong disturbance of the membrane upon an increase in the content of detergent, which facilitates the transbilayer movement. In the case of CDC, which has a higher amount of the protonated, lipophilic fraction and contains a smaller hydrophilic moiety than GCDC, the flip-flop of the BS through the membrane to an equilibrium situation occurs immediately after addition, even at low concentrations (Fig. 9 B).

Figure 9.

Time-dependent changes of the MSPstd of Laurdan-containing liposomes (1 mM lipid) at different BS concentrations (mM). (A) GCDC. (B) CDC. pH 7.4, 25°C.

Influence of pH

As shown in Fig. 10, the lipophilic CDC at a concentration of 0.8 mM reaches an equilibrium distribution between the monolayers within seconds at a pH of 7.4 and 6.8, and within minutes at pH 8.2. This difference in kinetics is due to the higher concentration of the hydrophilic species of CDC with increasing pH. In contrast, pH-dependent differences in the insertion and flip-flop kinetics cannot be seen for GCDC (not shown). The more hydrophilic BSs Ch and its conjugate GC behave very similarly to CDC and GCDC, respectively. The curve progressions of the trihydroxy BSs are analogous, appearing at higher BS concentrations than those obtained for the dihydroxy BSs, which is caused by their higher polarity and larger hydrophilic moiety (not shown).

Figure 10.

Time-dependent changes of the MSPstd of Laurdan-containing liposomes (1 mM lipid) at different pH values and 25°C in the presence of 0.80 mM CDC. The data represent 20 single measurements per minute of MSPstd.

Kinetics of BS/membrane partitioning

After detecting the time-dependent MSPstd changes, which were especially apparent for glycine-conjugated BSs such as GCDC, we investigated the influence of the incubation time on the binding behavior of GCDC at pH 7.4 (not shown). Compared with the 2 h incubation (DL = 440 ± 43 L⋅mol−1), the binding diagram is shifted parallel to higher Re values after 16 h. However, the lipid standardized distribution coefficient in the linear binding part does not change significantly (DL = 466 ± 81 L⋅mol−1), probably indicating a relocation of GCDC between the monolayers. At GCDC concentrations above 1.2 mM, the binding diagrams obtained after 2 h and 16 h incubations are congruent.

Discussion

The membrane interaction of BSs in vivo, especially in the liver, where they are actively secreted in high concentrations from hepatocytes into the canaliculus, is of great interest. In this case, it is important that they do not redistribute back into the hepatocytes due to passive diffusion. This is also true in the upper part of the small intestine, the duodenum, where BSs are needed at high concentrations to serve as emulsifiers; however, they should not be removed by passive permeation through the mucus of the small intestine into the portal blood. Therefore, studies of BS adsorption and bilayer permeation are of crucial importance.

Earlier studies have looked at the binding and partitioning of BS to liposomal membranes by directly measuring membrane-associated and free BSs using ultracentrifugation and equilibrium dialysis (32, 33). This direct method has advantages due to the accuracy of the binding data, but it is labor intensive and expensive to carry out.

In this study, based on preliminary work (25), we compared results obtained with Laurdan-labeled liposomes at pH 7.4 with those obtained using the direct method.

The Laurdan method, which is based on spectral changes of the probe that occur in the presence of increasing amounts of BS in the membrane, turned out to be more noisy than the direct method, as indicated by its higher standard deviations. Because of this, we were not able to obtain information about the binding site or binding strength at low BS concentrations. However, the linear part of the binding plot below the onset of membrane solubilization resulted in partition coefficients that were comparable to those obtained using the direct method. As expected, the more lipophilic dihydroxy BSs showed higher membrane partition coefficients than the trihydroxy BSs. The reason for the slightly higher partition coefficients obtained via the Laurdan method is unclear. An influence of 0.2 mol % of the label in the membrane on BS binding is unlikely. Possible explanations may include the particular sensitivity of the probe for the charge of the membrane-adsorbed BSs and/or the dependence of the Laurdan spectrum on the depth or modus of BS binding in the membrane. One advantage of the indirect Laurdan method for determining membrane partition coefficients is that it does not require expensive radioactive-labeled compounds of interest or time-consuming analytical methods for these compounds.

Another advantage of the Laurdan method is that it allows one to determine the kinetics of BS-membrane interactions. In this study, we found that adsorption of the BSs to the lipid membrane occurred very rapidly, within seconds. We were also able to measure the slow kinetics of the transbilayer movement (flip-flop) of BSs when they were conjugated with glycine, which enlarges the hydrophilic moiety and promotes hydration of the BSs, as well as lowers the pKa value of the molecules. Thus, the glycine-conjugated forms distribute into lipid bilayers and relocate between the single monolayers less rapidly than the more lipophilic unconjugated forms. Conjugation of BSs with glycine (or similarly with taurine, depending on the food supply) in the liver is therefore an important biochemical process that enables hepatocytes to inhibit transbilayer diffusion back into the cells after their secretion, and to keep the amount of protonated BSs in the duodenum (where the pH is still slightly acidic) low, thus keeping the BSs in the small intestine where they are needed.

Conclusions

We have shown that the use of Laurdan as a fluorescent probe in liposomes provides useful data regarding the interaction between BSs (as anionic detergents) and liposomes (as model membranes). Although the data obtained by ultracentrifugation to separate free from membrane-associated BSs are less noisy, the indirect fluorescence method is more rapid, is inexpensive, and provides additional information about the amount of charged detergent species at varying pH, as well as the kinetics of membrane adsorption and transmembrane diffusion (flip-flop). In general, Laurdan-labeled liposomes may be useful for determining the membrane interactions of various amphiphilic bioactive compounds, but their suitability for measuring the partitioning into lipid membranes has to be validated carefully, as was recently shown for different β-blockers (34).

Author Contributions

A.S. performed the major part of the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. G.F. complemented the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. P.T. designed, initiated, and performed research, and contributed analytic tools. R.S. designed research, performed part of the research, contributed analytic tools, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Editor: Heiko Heerklotz.

References

- 1.Pauletti G.M., Wunderli-Allenspach H. Partition coefficients in vitro: artificial membranes as a standardized distribution model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1994;1:273–282. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schubert R. Comparison of octanol/buffer and liposome/buffer partition coefficients as model for the in vivo behaviour of drugs. Proc. MoBBEL. 1994;8:20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leo A., Hansch C., Elkins D. Partition coefficients and their uses. Chem. Rev. 1971;71:525–616. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Balen G.P., Martinet Ca., Testa B. Liposome/water lipophilicity: methods, information content, and pharmaceutical applications. Med. Res. Rev. 2004;24:299–324. doi: 10.1002/med.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong P.L.G., Sugár I.P. Fluorescence studies of lipid regular distribution in membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2002;116:153–175. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris F.M., Best K.B., Bell J.D. Use of laurdan fluorescence intensity and polarization to distinguish between changes in membrane fluidity and phospholipid order. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1565:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00514-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parasassi T., De Stasio G., Gratton E. Quantitation of lipid phases in phospholipid vesicles by the generalized polarization of Laurdan fluorescence. Biophys. J. 1991;60:179–189. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klymchenko A.S., Duportail G., Mély Y. Bimodal distribution and fluorescence response of environment-sensitive probes in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2929–2941. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74344-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viard M., Gallay J., Paternostre M. Laurdan solvatochromism: solvent dielectric relaxation and intramolecular excited-state reaction. Biophys. J. 1997;73:2221–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78253-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parasassi T., Krasnowska E.K., Gratton E. Laurdan and Prodan as polarity-sensitive fluorescent membrane probes. J. Fluoresc. 1998;8:365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinic J., Biverståhl H., Parmryd I. Laurdan and di-4-ANEPPDHQ do not respond to membrane-inserted peptides and are good probes for lipid packing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolini C., Kraineva J., Winter R. Temperature and pressure effects on structural and conformational properties of POPC/SM/cholesterol model raft mixtures—a FT-IR, SAXS, DSC, PPC and Laurdan fluorescence spectroscopy study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parasassi T., De Stasio G., Gratton E. Phase fluctuation in phospholipid membranes revealed by Laurdan fluorescence. Biophys. J. 1990;57:1179–1186. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82637-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauet N., Artzner F., Paternostre M. Interaction between artificial membranes and enflurane, a general volatile anesthetic: DPPC-enflurane interaction. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3123–3137. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70037-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heerklotz H., Binder H., Klose G. Membrane/water partition of oligo(ethylene oxide) dodecyl ethers and its relevance for solubilization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1196:114–122. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heerklotz H., Binder H., Lantzsch G. Determination of the partition coefficients of the nonionic detergent C12E 7 between lipid-detergent mixed membranes and water by means of Laurdan fluorescence spectroscopy. J. Fluoresc. 1994;4:349–352. doi: 10.1007/BF01881454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paternostre M., Meyer O., Ollivon M. Partition coefficient of a surfactant between aggregates and solution: application to the micelle-vesicle transition of egg phosphatidylcholine and octyl beta-D-glucopyranoside. Biophys. J. 1995;69:2476–2488. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schubert R., Beyer K., Schmidt K.H. Structural changes in membranes of large unilamellar vesicles after binding of sodium cholate. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5263–5269. doi: 10.1021/bi00366a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waschinski C.J., Barnert S., Tiller J.C. Insights in the antibacterial action of poly(methyloxazoline)s with a biocidal end group and varying satellite groups. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1764–1771. doi: 10.1021/bm7013944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milsmann M.H.W., Schwendener R.A., Weder H.G. The preparation of large single bilayer liposomes by a fast and controlled dialysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;512:147–155. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schubert R. Liposome preparation by detergent removal. Methods Enzymol. 2003;367:46–70. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)67005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bangham A.D., Standish M.M., Watkins J.C. Diffusion of univalent ions across the lamellae of swollen phospholipids. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;13:238–252. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson F., Hunt C.A., Papahadjopoulos D. Preparation of liposomes of defined size distribution by extrusion through polycarbonate membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1979;557:9–23. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartlett G.R. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 1959;234:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theobald, A. 2009. Laurdan als Fluoreszenzsonde zur Quantifizierung der Wechselwirkungen von Gallensalzen mit Liposomenmembranen. PhD thesis. Albert Ludwig University, Freiburg, Germany.

- 26.Hope M.J., Bally M.B., Cullis P.R. Production of large unilamellar vesicles by a rapid extrusion procedure: characterization of size distribution, trapped volume and ability to maintain a membrane potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;812:55–65. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fröhlich M., Brecht V., Peschka-Süss R. Parameters influencing the determination of liposome lamellarity by 31P-NMR. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2001;109:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schubert R., Schmidt K.H. Structural changes in vesicle membranes and mixed micelles of various lipid compositions after binding of different bile salts. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8787–8794. doi: 10.1021/bi00424a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schubert R. Habilitation treatise. Eberhard Karls University; Tübingen, Germany: 1992. Gallensalz-Lipid-Wechselwirkungen in Liposomen und Mischmizellen. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lichtenberg D. Characterization of the solubilization of lipid bilayers by surfactants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;821:470–478. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schurtenberger P., Mazer N., Kanzig W. Micelle to vesicle transition in aqueous solutions of bile salt and lecithin. J. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:1042–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hellwich U., Schubert R. Concentration-dependent binding of the chiral beta-blocker oxprenolol to isoelectric or negatively charged unilamellar vesicles. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995;49:511–517. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00418-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fini A., Roda A. Chemical properties of bile acids. IV. Acidity constants of glycine-conjugated bile acids. J. Lipid Res. 1987;28:755–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Först G., Cwiklik L., Hof M. Interactions of beta-blockers with model lipid membranes: molecular view of the interaction of acebutolol, oxprenolol, and propranolol with phosphatidylcholine vesicles by time-dependent fluorescence shift and molecular dynamics simulations. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014;87:559–569. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Möller, D. 1988. Bindungsstudien von Chenodesoxycholat und Ursodesoxycholat an unilamellaren Ei-Lecithin-Liposomen. PhD thesis. Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany.