Abstract

Background/Objectives

Depression, suicide ideation (SI) and suicide attempts (SA) are common among older adults, representing serious public health problems. Individuals with multiple comorbidities and frequent contact with hospital–based emergency departments (ED) may have elevated – but unrecognized – risk. To inform future interventions, we sought to estimate the prevalence of self-harm/SI/SA among older ED patients, including differences by age group, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Design

Quasi-experimental, multi-phase, 8-center study with prospective review of consecutive patient charts during enrollment shifts (November 2011–December 2014).

Setting

8 EDs located in 7 states, all with protocols for nurses to screen every patient for suicide risk (“universal screening”).

Participants

Adult (≥18 years) registered ED patients.

Measurements

Patient demographics, documented screening for self-harm/SI/SA, positive self-harm/SI/SA among those with screening performed.

Results

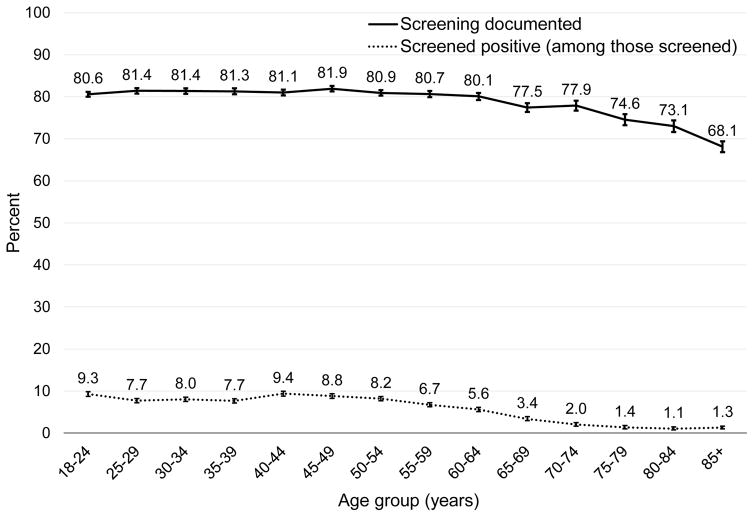

Among a total of 142,534 patient visits, 23.3% were by patients aged ≥60 years. Documented screening for self-harm/SI/SA declined with age, from approximately 81% in younger age groups to a low of 68% among those aged ≥85 years. The prevalence of positive screens for self-harm/SI/SA also declined with age, with peaks among young and middle-aged adults (9.0%) and a nadir among patients aged ≥75 years (1.2%).

Conclusion

Documented screening for suicide risk declined with patient age in this large sample of ED patients. Although the explanation for this finding is unclear, we hypothesize that at least part of the decline is related to increasing rates of altered mentation or other patient-level barriers to screening in the older population. Our findings support the need for more detailed examination of the best methods for identifying – and treating – suicide risk among older adults.

Keywords: suicide, emergency department, depression, screening, older adult

INTRODUCTION

Suicide prevention among older adults is difficult,1 in part because subtle presentations, high medical comorbidity, and concurrent cognitive impairment can complicate accurate assessment of suicidality diagnosis.2 Prior work also suggests that clinicians often under-diagnose or under-treat depression (a robust risk factor for suicide) and suicide ideation (SI) among older adults.3, 4 These findings might stem partly from difficulties in distinguishing between normal reactions to the vicissitudes of aging and suicidal thoughts triggered by hopelessness, social stressors, or physical or mental illness.5 In addition, older suicidal individuals are more likely to use advance planning and less likely to ask for help,6 with a suicide attempt (SA) to completion ratio among older adults of approximately 4 to 1, compared to ratios between 8 to 1 and 20 to 1 in the general population.5 Given the advance planning and high lethality of SA among older adults, primary suicide prevention – i.e., reaching those at risk before they become suicidal – is especially important in this age group.5, 6

Unfortunately, depression, SI and SA remain common among older adults, with an estimated 10–20% of older adults having significant depressive symptoms.7 Age-adjusted suicide rates are especially high among older men,8 and the suicide rate among the Baby Boom cohort appears higher than previous generations,9, 10 adding to the urgency to find ways to identify and help older adults at risk.

Identification, and intervention, would ideally occur in the full spectrum of clinical settings. Emergency departments (EDs) are an important location for such efforts, since almost half of older adults have at least one ED visit a year.11 In addition, ED patients may represent a particularly vulnerable population, relative to the general community, because of their higher rate of medical comorbidities, acute injuries, illnesses or psychosocial crises.11–13 Indeed, an ED visit is often a “sentinel event” for the older patient, in that it signifies acute illness or injury that increases subsequent risk for declining functional ability, independence, and health.13, 14 To compound matters, general and mental health-related ED visits by older adults are increasing.15

Whereas targeted interventions in primary care settings have been shown to improve screening and effective treatment for depression,1 less is known about these approaches in the ED. Older ED patients with mental health reasons for an ED visit are more likely to be admitted, compared to younger patients,16 but we do not know whether the general prevalence or patterns of SI/SA differ from younger or middle aged adult populations. To address this knowledge gap, we sought to estimate the prevalence of SI/SA among older ED patients, including differences by age group, sex, and race/ethnicity.

METHODS

Study Design

Data came from the Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) study, a quasi-experimental, eight-center study designed to test an approach to universal screening for suicide risk and post-visit telephone intervention among ED patients (see Boudreaux et al., 2013 for complete description).17 The ED-SAFE consisted of three phases of data collection: Treatment as Usual (Phase 1), Universal Screening (Phase 2), and Universal Screening + Intervention (Phase 3). The current study predominantly analyzed data from the screening log in phases 2 and 3 (collected from November 2011 through December 2014) to allow for a detailed description of the patterns of self-harm/SI/SA among older adults at EDs using universal screening. Specifically, after the introduction of universal screening, ED protocols directed nurses to screen all patients, regardless of reason for visit, for suicide risk using standardized screening questions.

Participating sites staffed their EDs with research assistants (RAs) at least 40 hours/week during peak volume hours (12:00 PM to 10:00 PM), with at least one weekend day per month. All adult patients who entered the ED during data collection shifts were documented on a screening log. RAs at the eight ED-SAFE sites prospectively reviewed the medical charts of consecutive adult (≥18 years) registered ED patients and recorded the presence of clinician documentation of self-harm/SI/SA on a screening log. Institutional review boards at each site approved all study procedures and protocols; overall study oversight and monitoring were conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

Measures

On the screening log, RAs recorded: triage time and date; patient demographics (age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, and race). They also recorded whether the ED visit was for a psychiatric complaint (Phase 3 only), whether any screening for intentional self-harm/SI/SA was documented anywhere on the patient’s ED medical record (primary clinician outcome), and whether self-harm was documented as present (positive screen) or absent (negative screen). In this limited screening database, RAs did not review other chart variables (such as Emergency Severity Index level of visit, disposition, or past medical or psychiatric history). Cases where the patient was unable to answer screening questions (e.g., cognitive impairment, acute alteration in mental status, critical illness, etc.) were marked as having no screening; in cases without screening, RAs did not attempt to identify or record the reason screening was not completed. The ED-SAFE study used the following definitions: self-harm, “thoughts of harming self in past week;” SI, “thoughts of ending life in past week;’ and SA, “suicide attempts in past 6 months or previously.” On the screening log, there was a single, grouped “self-harm” variable for whether there was screening for any one or all of these (self-harm or SI or SA). Response options included: “No screening documented;” “No self-harm present (patient screened but denied);” Yes, self-harm present (current, past or unclear timing).

Data Analysis

Prevalence rates of current self-harm/SI/SA among ED patients were estimated using percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A comparison of these prevalence estimates was completed by patient age (by 5-year increments). Based on an observed inflection point in rates at about age 60 years in our data, we analyzed older adults aged 60 years and older for differences in sex, race, and ethnicity.

RESULTS

The final screening database included 142,534 patient visits from the eight ED-SAFE EDs over 37 months (study phases 2 and 3). Of this group, 45.5% of visits (n=64,854) were by men, 58.8% (n=83,793) by whites, and 43.3% (n=61,690) by non-Hispanics. Nearly one quarter (n=33,167; 23.3%) of all visits were by patients aged ≥60 years. Among visits by older patients, 44.6% were by men, 70.8% by whites, and 43.6% by non-Hispanics.

Across age groups, 113,889 patients (79.9%) had documentation of completed screening for self-harm/SI/SA. There were significant differences in completed screening across age groups, with a decline in rates beginning at approximately 60 years (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1). This trend was present both before and after the introduction of the universal screening protocols (Supplemental Table 1). Among those aged ≥60 years, only 75.9% had documented screening for self-harm/SI/SA. Across age groups, screening rates did not significantly vary by the sex of patient (data not shown).

Figure 1. Screening rates and prevalence of self-harm/suicide ideation/suicide attempt among emergency department patients, by age group (n=142,543).

Bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Baseline data from Phase 1 (n=94,257).

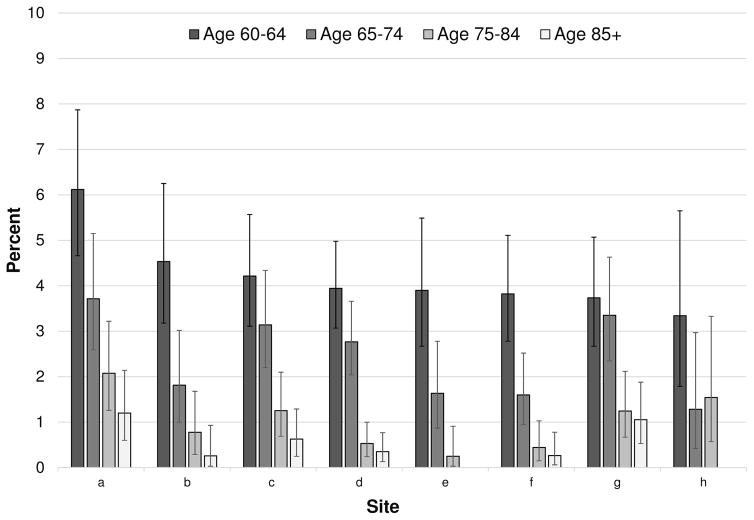

Among all patients with documented screening (n=142,543), 5.5% were identified as having self-harm/SI/SA. This rate varied greatly and significantly across age groups, with the lowest prevalence rates among adults aged 75 years or older (1.2%, 95%CI 1.0–1.4%) and the highest rates among those aged 18–24 (9.0%, 95%CI 8.6–9.5%) or 40–49 years (9.1%, 95%CI 8.7–9.5; Figure 1). Observed prevalence rates among screened patients also varied across the study sites, although the overall trends were similar (Figure 2). There were also differences by sex in the prevalence of self-harm/SI/SA among those screened. Self-harm/SI/SA was significantly more common in men than in women for those aged 45 to 49 years (9.8%, 95%CI 9.0–10.6; versus 8.3%, 95%CI 7.6–9.0%), but it was less common in men than in women for those aged 25 to 29 years (6.6%, 95%CI 6.0–7.4%; versus 8.1%, 95%CI 7.5–8.7%). Among the three older age groups (60–69 years of age; 70–70 years; 80+ years), self-harm/SI/SA was equally common among men and women, but it was more common among non-Hispanic Whites than other racial/ethnic groups (Table 1). Among older adults, self-harm/SI/SA was most commonly identified in non-Hispanic white men aged 60–69 years (17.0%).

Figure 2. Observed Prevalence of Self-Harm/Suicide Ideation/Suicide Attempt among Emergency Department patients who were Screened, by Age Group and Site (n=142,543).

Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Older Emergency Department Patients who Screened Positive for Self-Harm/Suicide Ideation/Suicide Attempt, by Age Group (n=7,584)

| Total | Age 60–64 | Age 65–74 | Age 75–85 | Age 85+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | n (%) | 95%CI | n (%) | 95%CI | n (%) | 95%CI | n (%) | 95%CI |

| Sex (P=.11) | |||||||||

| Male | 3,577 | 176 (4.9) | 4.2–5.7 | 93 (2.6) | 2.1–3.2 | 37 (1.0) | 0.7–1.4 | 14 (0.4) | 0.2–0.7 |

| Female | 4,274 | 155 (3.6) | 3.1–4.2 | 108 (2.5) | 2.1–3.0 | 37 (0.9) | 0.6–1.2 | 26 (0.6) | 0.4–0.9 |

| Race (P=.004) | |||||||||

| non-White | 1,543 | 51 (3.3) | 2.5–4.3 | 21 (1.4) | 0.8–2.1 | 5 (0.3) | 0.1–0.8 | 1 (0.1) | 0.0–0.4 |

| White | 5,556 | 251 (4.5) | 4.0–5.1 | 175 (3.1) | 2.7–3.6 | 64 (1.2) | 0.9–1.5 | 35 (0.6) | 0.4–0.9 |

| Not documented | 755 | 29 (3.8) | 2.6–5.5 | 5 (0.7) | 0.2–1.5 | 5 (0.7) | 0.2–1.5 | 4 (0.5) | 0.2–1.4 |

| Ethnicity (P=.21) | |||||||||

| non-Hispanic | 3,818 | 176 (4.6) | 4.0–5.3 | 100 (2.6) | 2.1–3.2 | 44 (1.2) | 0.8–1.5 | 26 (0.7) | 0.5–1.0 |

| Hispanic | 593 | 18 (3.0) | 1.8–4.8 | 5 (0.8) | 0.3–2.0 | 2 (0.3) | 0.0–1.2 | 2 (0.3) | 0.0–1.2 |

| Not documented | 3,443 | 137 (4.0) | 3.4–4.7 | 96 (2.8) | 2.3–3.4 | 28 (0.8) | 0.5–1.2 | 12 (0.3) | 0.2–0.6 |

P values from chi-square test.

DISCUSSION

In this review of over 140,000 visits to eight EDs across the United States, we found that rates of screening for self-harm/SI/SA – while quite high overall given the sites’ protocols for universal screening – decreased significantly with age, as did the prevalence of positive screens among those asked. Although the explanation for these findings is unclear, we hypothesize that at least part of the decline is related to an increased prevalence of conditions precluding questioning (e.g., dementia, severe confusion) among older adults. Nevertheless, the findings are striking enough that we suspect there are likely true age-related differences in screening practices among those patients able to answer. The low rate of positive self-harm/SI/SA among older adults is interesting, given high suicide rates among older adults1 and prior work demonstrating elevated risk of SI/SA after ED or hospital contact and among patients with physical impairments or declining health (both common among geriatric ED patients).18–20 Thus, our findings suggest the need for both improved provider awareness about risk of suicide in older adults (and the need to screen for it) as well as enhanced identification systems (such as possible adjustment of the screening questions used for older adults).

Our finding of an age-related decline in suicide screening by providers is consistent with prior work demonstrating that healthcare providers are prone to both under-recognize and under-treat depression, self-harm and SI in older versus younger patients.3, 4, 21 The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention specifically includes “improve the screening and treatment for depression of the elderly,”22 and the Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal encourages screening for suicide risk among patients of all ages who are being treated for emotional or behavioral disorders in general hospitals (including EDs).23 While not widely in practice, ED-based universal screening for suicide risk (where all patients, regardless of reason for visit, are questioned) does appear feasible when well-implemented.21, 24, 25 In settings without universal screening, patients with known psychiatric problems or substance abuse appear most likely to be questioned about suicide risk;21, 26 while these groups certainly do have elevated suicide risk, they are not the only patients at risk.27 A key advantage of universal screening is that it is aimed at enhancing detection among patients with more hidden risk factors,28, 29 for whom providers may have a low clinical suspicion of suicide risk and therefore a lower likelihood of screening.

The low observed prevalence of positive self-harm/SI/SA among older adults raises questions, however, about the best suicide screening domains or questions for this population—including whether universal screening is the best approach for older adults. To our knowledge, the differential accuracy of typical screening questions (e.g., “Have you had thoughts of killing yourself?”) among age groups is unknown; the brief “Patient Safety Screener” used at the eight ED-SAFE EDs was validated among adults aged 18 years or older.30 The highest observed prevalence of self-harm/SI/SA among older adults in our study was among white men aged 60–69 years, a demographic group with a particularly high suicide death rate.8 This suggests that at least some older men were responding to the screening questions, although we cannot know how many men at risk were missed. Older adults face different (and often more severe) social stressors compared to younger adults; particular stressors associated with suicide risk include social isolation, thwarted belongingness, perceived sense of being a burden on others (often related to physical impairments and need for assistance with activities of daily living), bereavement after loss of a spouse, multiple physical diseases, and declining health.18, 31 Thus, use of additional or alternative screening tools – like the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, or the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire32–34 – may yield better results among older adults. Screening for upstream stressors (e.g., isolation) may also allow for linkage of vulnerable older patients with community resources to mitigate these stressors and thereby reduce the risk of suicide.31 This approach has been suggested in primary care and community settings but might also be useful in ED settings. Such approaches might be integrated with other efforts to improve and standardize evidence-based care for geriatric ED patients.35 These important issues merit further investigation.

Limitations of this study include that we did not know the reason screening was not performed, so patients who were unable to answer questions could not be differentiated from those who could have answered but were not asked. For example, patients with altered mentation (from chronic conditions like dementia or from acute illnesses) would not have had screening completed, and altered mentation may be more common among older populations. Therefore the differences in rates of observed prevalence may reflect differences in screening completion or in true prevalence. In follow-up work, we plan to complete a more detailed retrospective chart review to better differentiate these groups. The ED-SAFE screening database had a small number of variables and was de-identified to address privacy concerns; as a result, we are not able to review individual patients’ charts for more details. The database also did not separate self-harm, SI and SA, so we could not characterize or compare patients across these three groups, but all three of these groups are at risk for future suicide and are therefore deserving of identification by providers. The eight ED-SAFE sites varied in size and availability of mental health consultants,21 but all of them implemented universal screening and used identical methodology for collection of ED-SAFE screening data. Because these eight sites are not representative of all EDs (especially smaller or rural EDs), our results may not generalize outside teaching hospital EDs.

In summary, early recognition and treatment of depression, as well as improved management of chronic health conditions, functional limitations and social stressors, can make a difference among older adults by improving quality of life and reducing morbidity and mortality. ED clinicians could play a critical role in the diagnosis of depression and self-harm/SI/SA and in guiding subsequent treatment, but we found that rates of both screening and prevalence of self-harm/SI/SA among ED patients declined with age. Our results suggest the need for both enhanced screening protocols (with provider training) and possibly modified screening questions for use with older adults. With persistently high rates of suicide among older adults and a growing older adult population, there is an urgent need to improve the identification of suicide risk among older adults in EDs, as well as in outpatient and non-clinical settings.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Screening rates and prevalence of self-harm/suicide ideation/suicide attempt among emergency department patients, by age group and study phase (n=236,791)

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by Awards U01MH088278 and R03MH107551 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the Paul Beeson Career Development Award Program [The National Institute on Aging; AFAR; The John A. Hartford Foundation; and The Atlantic Philanthropies; Betz-K23AG043123]. No sponsor had any direct involvement in data analysis or manuscript preparation.

Sponsor’s Role: This work was supported by Awards U01MH088278 and R03MH107551 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the Paul Beeson Career Development Award Program [The National Institute on Aging; AFAR; The John A. Hartford Foundation; and The Atlantic Philanthropies; Betz-K23AG043123]. No sponsor had any direct involvement in data analysis or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Presentations: None

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to report.

Author Contributions: CAC, IM, and EDB conceived, designed and supervised completion of the ED-SAFE study. MEB and SAA conceived, designed, and obtained funding for the analysis reported in this manuscript, with input and support from DS, CAC, IM, EDB. CAC, IM and EDB recruited the participating centers and, along with SAA, they managed the data, including quality control. MEB supervised data collection at one participating site. CAC, IM, and EDB serve on the ED-SAFE Steering Committee. MEB, SAA, and EDB designed the statistical analysis and SAA analyzed the data. MEB drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. MEB and EDB take responsibility for the paper as a whole.

References

- 1.Van Orden KA, Conwell Y. Issues in research on aging and suicide. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:240–251. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1065791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unutzer JPM. Older adults with severe, treatment-resistant depression. JAMA. 2012;308:909–918. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hustey FM, Smith MD. A depression screen and intervention for older ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M, Conwell Y, et al. Key Considerations for preventing suicide in older adults: Consensus opinions of an expert panel. Crisis. 2011;32:106–109. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szanto K, Gildengers A, Mulsant BH, et al. Identification of suicidal ideation and prevention of suicidal behaviour in the elderly. Drug Aging. 2002;19:11–24. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, et al. Age differences in behaviors leading to completed suicide. Am J Geriat Psychiat. 1998;6:122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laborde-Lahoz P, El-Gabalawy R, Kinley J, et al. Subsyndromal depression among older adults in the USA: Prevalence, comorbidity, and risk for new-onset psychiatric disorders in late life. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30:677–685. doi: 10.1002/gps.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (online); [Accessed April 26, 2016]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiat. 2002;52:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blazer DG, Bachar JR, Manton KG. Suicide in late life. Review and commentary. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:519–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb04244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emergency Department Visitors and Visits: Who Used the Emergency Room in 2007? National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services (online); [Accessed April 26, 2016]. NCHS Data Brief No. 38 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db38.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point 2007. [Accessed April 26, 2016];Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System, Institute of Medicine (online) Available at: http://books.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11621.

- 13.Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, et al. Older patients in the emergency department: A review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB. Older adults in the emergency department: A systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:238–247. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.121523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larkin GL, Claassen CA, Emond JA, et al. Trends in US Emergency Department visits for mental health conditions, 1992 to 2001. Psychiat Serv. 2005;56:671–677. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HCUP Statistical Brief #92. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (online); 2010. [Accessed April 26, 2016]. Mental health and substance abuse-related emergency department visits among adults, 2007. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb92.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boudreaux ED, Miller I, Goldstein AB, et al. The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE): Method and design considerations. Contemporary clinical trials. 2013;36:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erlangsen A, Stenager E, Conwell Y. Physical diseases as predictors of suicide in older adults: A nationwide, register-based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:1427–1439. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erlangsen A, Vach W, Jeune B. The effect of hospitalization with medical illnesses on the suicide risk in the oldest old: A population-based register study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:771–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP, et al. Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1179–1184. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caterino JM, Sullivan AF, Betz ME, et al. Evaluating current patterns of assessment for self-harm in emergency departments: A multicenter study. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:807–815. doi: 10.1111/acem.12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action 2001. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (online); [Accessed June 15, 2015]. Available at: http://www.sprc.org/sites/sprc.org/files/library/nssp.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (online); [Accessed April 26, 2016]. Hospital National Patient Safety Goal 15.01.01 2015. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2015_npsg_hap.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boudreaux ED, Camargo CA, Jr, Arias SA, et al. Improving suicide risk screening and detection in the emergency department. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Apr;50(4):445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boudreaux ED, Horowitz LM. Suicide risk screening and assessment: Designing instruments with dissemination in mind. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:S163–S169. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ting SA, Sullivan AF, Miller I, et al. Multicenter study of predictors of suicide screening in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betz ME, Schwartz R, Boudreaux ED. Unexpected suicidality in an older individual in an emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1044–1045. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claassen CA, Larkin GL. Occult suicidality in an emergency department population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:352–353. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boudreaux ED, Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Mood disorder screening among adult emergency department patients: A multicenter study of prevalence, associations and interest in treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boudreaux ED, Jaques ML, Brady KM, et al. The Patient Safety Screener: Validation of a brief suicide risk screener for emergency department settings. Arch Suicide Res. 2015;19:151–160. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1034604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conwell Y. Suicide later in life: Challenges and priorities for prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:S244–S250. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heisel MJ, Flett GL. The development and initial validation of the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:742–751. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000218699.27899.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parkhurst KA, Conwell Y, Van Orden KA. The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire with a shortened response scale for oral administration with older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:277–283. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.1003288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter CR, Bromley M, Caterino JM, et al. Optimal older adult emergency care: Introducing multidisciplinary Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1360–1363. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Screening rates and prevalence of self-harm/suicide ideation/suicide attempt among emergency department patients, by age group and study phase (n=236,791)