Abstract

Recent advances in follicular lymphoma (FL) have resulted in prolongation of overall survival (OS). Here assessed if early events as defined by event-free survival (EFS) at 12 and 24 months from diagnosis (EFS12/EFS24) can inform subsequent OS in FL. 920 newly diagnosed grade 1–3a FL patients enrolled on the University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma SPORE Molecular Epidemiology Resource (MER) from 2002–2012 were initially evaluated. EFS was defined as time from diagnosis to progression, relapse, re-treatment, or death due to any cause. OS was compared to age-and-sex-matched survival in the general US population using standardized mortality ratios (SMR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used a cohort of 412 FL patients from two Lyon, France hospital registries for independent replication. Patients who failed to achieve EFS12 had poor subsequent OS (MER SMR=3.72, 95%CI: 2.78–4.88; Lyon SMR=8.74, 95%CI: 5.41–13.36). Conversely, patients achieving EFS12 had no added mortality beyond the background population (MER SMR=0.73, 95%CI: 0.56–0.94, Lyon SMR=1.02, 95%CI: 0.58–1.65). Patients with early events after immunochemotherapy had especially poor outcomes (EFS12 failure: MER SMR=17.63, 95%CI:11.97–25.02, Lyon SMR=19.10, 95%CI:9.86–33.36; EFS24 failure: MER SMR=13.02, 95%CI:9.31–17.74, Lyon SMR=7.22, 95%CI:4.13–11.74). In a combined dataset of all patients from both cohorts, baseline FLIPI was no longer informative in EFS12 achievers. Reassessment of patient status at 12 months from diagnosis in follicular lymphoma patients, or at 24 months in patients treated with immunochemotherapy, is a strong predictor of subsequent overall survival in FL. Early event status provides a simple, clinically relevant endpoint for studies assessing outcome in FL.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common indolent and second most common lymphoma subtype in the western world with an incidence of 3.2 per 100,000 person-years in the United States.1 FL is a heterogeneous disease with varied presentation at diagnosis resulting in a wide range of initial management strategies ranging from observation (OBS) to anthracycline containing immunochemotherapy regimens. FL is considered an indolent, usually non-curable, lymphoma. Disease outcome is highly variable with some patients surviving decades without need of treatment while others have an aggressive course with rapidly progressive, treatment-resistant disease with increased mortality. In addition, FL can transform to a more aggressive form of lymphoma at a rate of 2–3% per year.2–4

Several reports have documented improvement in overall survival (OS) over a generation for patients with FL in the immunochemotherapy era5–13 and recent estimates from the National LymphoCare study describe 70–80% OS at 8 years.14 New management options are implicitly introduced with the goal of further improving outcomes in FL patients. Utilization of OS as an endpoint in studies of FL is challenging given the long time period before a sufficient number of death events occur and the uncertainty of how many deaths are lymphoma related. These concerns suggest a potential benefit to understanding OS in FL relative to expected survival for the general population.

Despite the long disease course, prognostic indices for FL are calculated at baseline and generally are not reassessed again during the lifetime of affected patients.15 Response to initial management as a surrogate marker for later outcomes in FL has been a topic of recent study. Depth of response to immunochemotherapy as assessed by FDG-Positron Emission Tomography (PET) predicts for longer progression-free survival (PFS).16 Others are investigating the relationship between durability of CR and OS17. Recent data show progression within 24 months of diagnosis predicts for shorter OS in FL patients treated with R-CHOP18. We have recently identified that patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who remain event-free 24 months from diagnosis after standard of care immunochemotherapy have an equivalent subsequent OS to the age and sex matched general population, while patients with refractory disease or those who relapse and require retreatment within the first 24 months have a very poor outcome19. The aims of the current study were to perform a similar analysis in FL to determine if early event status can inform subsequent survival. We assessed outcomes from FL patients enrolled in a large, dual center prospective observational cohort through our Lymphoma SPORE. A validation cohort of patients from two Lyon, France based hospital registries was used to confirm results.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was reviewed and approved by the human subjects institutional review board at the Mayo Clinic and the University of Iowa, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients were prospectively enrolled in the Molecular Epidemiology Resource (MER) of the University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE).20,21 Details on FL patients from this cohort have been previously reported3 and further information can be found in the supplemental material. Inclusion criteria for this analysis were initial diagnosis of grade 1–3a FL and enrolled from September 1, 2002 – December 31, 2012. Patients with primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, FL grade 3b subtype, a composite diagnosis including another (non-follicular) lymphoma subtype, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, or evidence of clinical or pathological transformation at the time of initial FL diagnosis were excluded.

Replication study

Data for replication were obtained from an independent set of FL patients diagnosed between September, 2002 and 2010 and enrolled in one of two Lyon, France based hospital registries at Centre Leon Berard (CLB) and Centre Hospitalier Lyon Sud (CHLS). The CLB dataset consisted of newly diagnosed patients with FL treated in routine clinical practice at the Leon Berard Cancer Center between 2002 and 2010.22 The CHLS dataset consisted of newly diagnosed patients with FL treated in routine clinical practice at the CHLS between 2002 and 2010.

Statistical methodology

Event free survival (EFS) was defined as time from diagnosis until relapse or progression, unplanned retreatment of lymphoma after initial management, or death due to any cause. EFS12 was defined as EFS status 12 months from diagnosis. OS from failing EFS12 was defined as time from EFS12 failure to death or last follow-up. OS from achieving EFS12 was defined as time from achieving EFS12 to death or last follow-up. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to display survival graphically. Expected survival accounting for age and sex was generated in R using the general United States (survexp.us)23 and French (survexp.fr)24 populations as reference groups for the US and French data, respectively.24–26 Observed vs. expected OS was plotted using a conditional approach27 and summarized using standardized mortality ratios (SMR) of observed to expected deaths.28 Further details, including assessment of other time points including EFS24, can be found in the supplemental materials.

Results

Patient characteristics

Nine-hundred twenty newly diagnosed grade 1–3a FL patients were enrolled in the MER from 2002–2012 and met the study eligibility criteria. The median age at enrollment was 60 years (range 23–93) and 52% were male (Table 1). Eight-hundred one patients (87%) had grade 1–2 FL and 119 patients (13%) had grade 3a FL. The most common initial management approaches were observation (n = 326, 33%), rituximab (R) monotherapy (n = 111, 12%), and alkylator or anthracycline-based immunochemotherapy (n = 349, 38%). In the immunochemotherapy treated patients, 165 were treated with R-CHOP or comparable anthracycline based chemotherapy, 130 were treated with R-CVP based chemotherapy, and 54 were treated with R-bendamustine based chemotherapy. At a median follow-up of 71 months (range 5–144), 453 patients (49%) had an event (death, progression, or retreatment) including 130 patients (14%) who died. Kaplan-Meier estimates for the percent of all patients achieving EFS12 and EFS24 were 83% (95% CI, 80%–85%) and 71% (95% CI, 68%–74%), respectively. EFS and OS from diagnosis are shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | MER N=920 | Lyon N=412 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No. | % | N | % | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Median | 60 | 59 | ||

| Range | 23–93 | 24–95 | ||

| > 60 | 440 | 48 | 172 | 42 |

| Male | 482 | 52 | 196 | 48 |

| ECOG Performance status ≥ 2 | 38 | 4 | ||

| Ann Arbor stage III/IV | 615 | 68 | 307 | 75 |

| LDH > ULN | 213 | 27 | 106 | 27 |

| B symptoms (any) | 94 | 10 | NA | NA |

| Bone marrow involvement | 342 | 43 | NA | NA |

| Hemoglobin < 12 g/dL | 105 | 13 | 55 | 15 |

| Grade | ||||

| 1–2 | 801 | 87 | NA | NA |

| 3a | 119 | 13 | NA | NA |

| More than four nodal groups | 315 | 36 | NA | NA |

| FLIPI | ||||

| 0–1 | 366 | 40 | 137 | 37 |

| 2 | 312 | 34 | 119 | 32 |

| 3–5 | 242 | 26 | 113 | 31 |

| Initial management | ||||

| Observation | 326 | 33 | 82 | 20 |

| Rituximab monotherapy | 111 | 12 | 43 | 10 |

| Immunochemotherapy | 349 | 38 | 243 | 59 |

| Chemotherapy without rituximab | 40 | 4 | * | |

| Radiation therapy only | 58 | 6 | * | |

| Other treatment | 36 | 4 | 44* | 11 |

Abbreviations: NA=Not available; FLIPI, Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal; % based on those with available data;

N=44 includes chemotherapy without rituximab and radiation therapy only

Replication cohort

To replicate findings, an external validation dataset of 412 newly diagnosed patients with FL was assembled from two Lyon, France based hospital registries, including 262 patients from CHLS and 150 from CLB. The median age at diagnosis was 59 years (range 24–95) and 48% were male (Table 1). The most common types of initial management were observation (n = 82, 20%), rituximab monotherapy (n = 43, 10%), and immunochemotherapy (n = 243, 59%). At a median follow-up of 63 months (range 4–135), 215 patients (52%) had an event and 39 (9%) died. Kaplan-Meier estimates for achieving EFS12 and EFS24 were 82% (95% CI, 78%–86%) and 67% (95% CI, 62%–72%), respectively. EFS and OS from diagnosis are shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

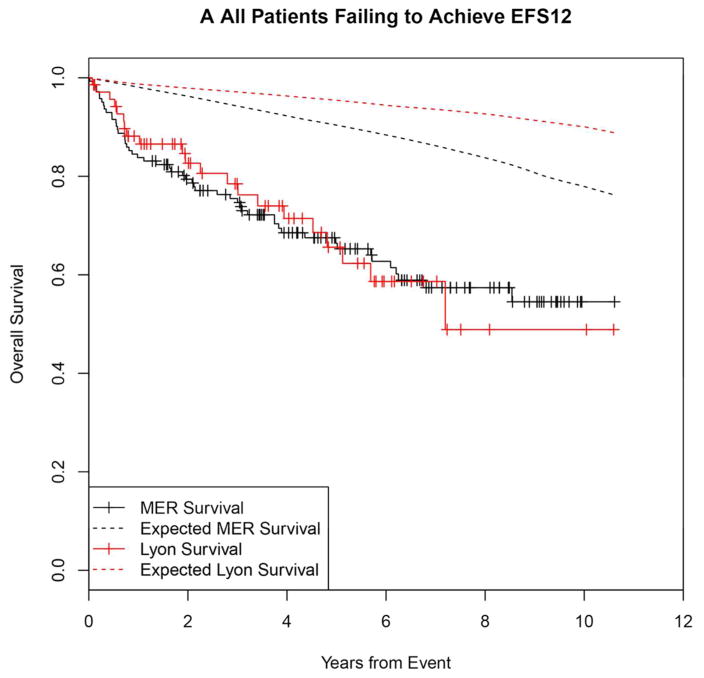

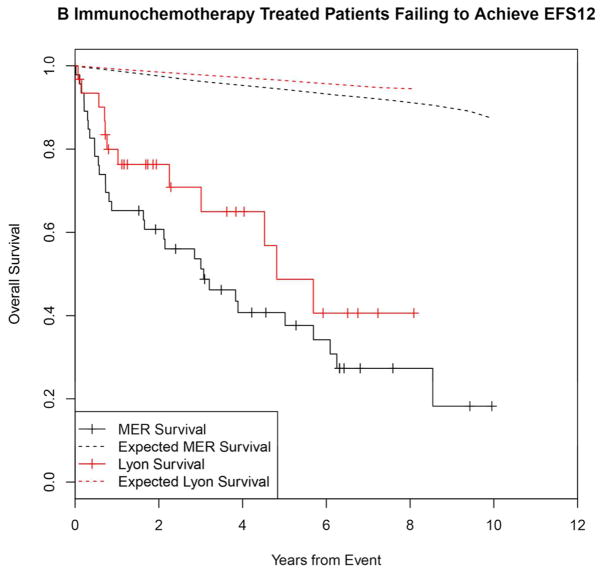

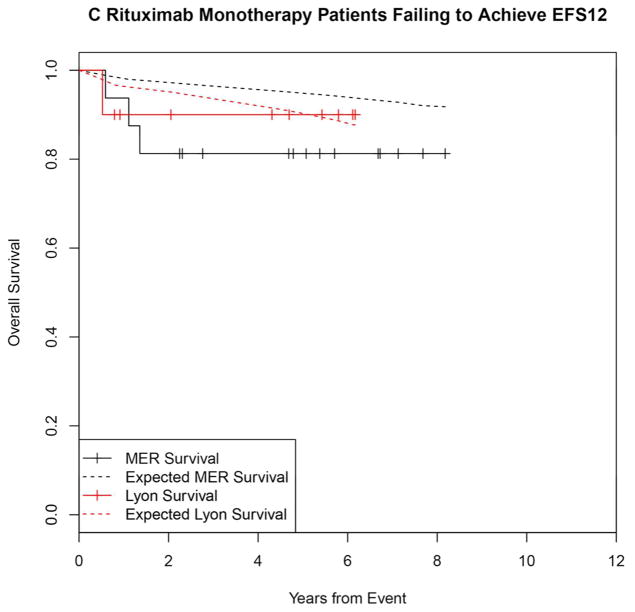

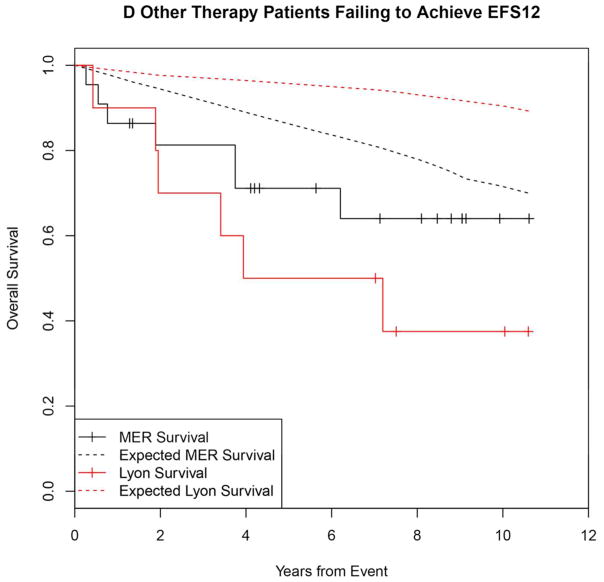

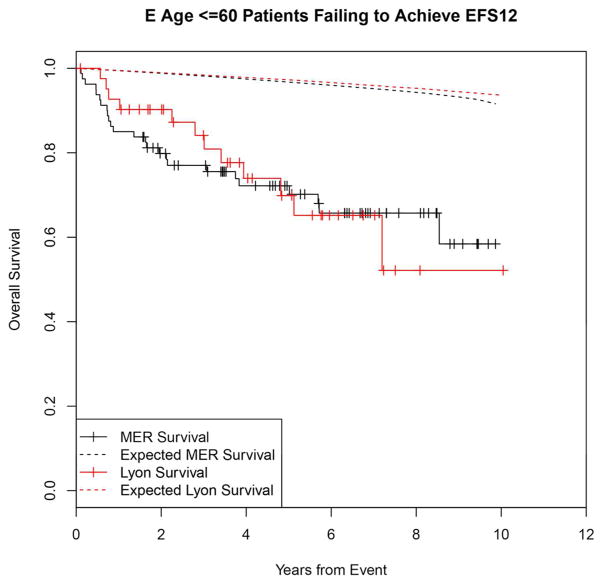

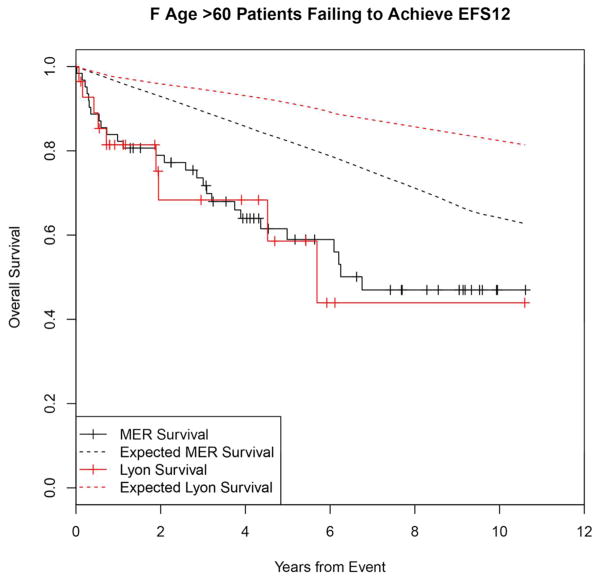

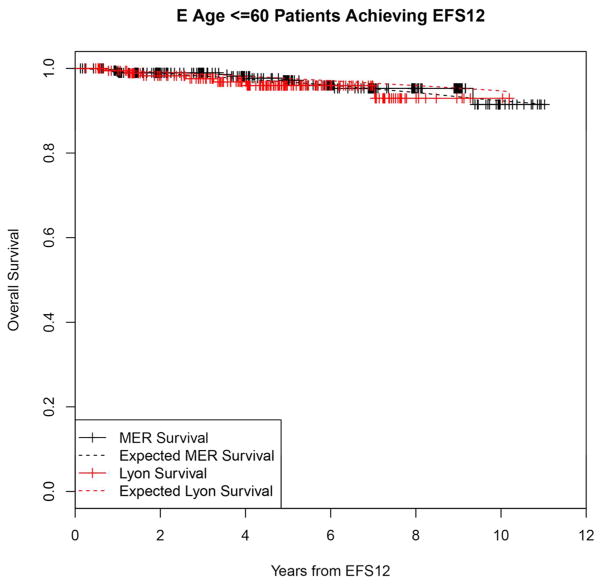

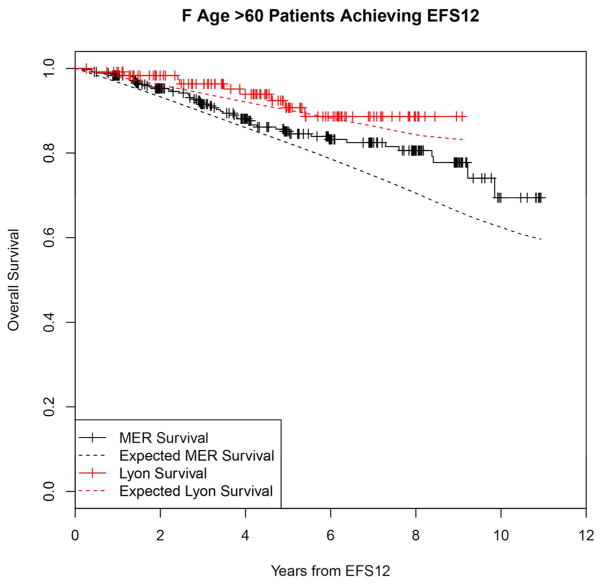

Outcomes after failing to achieve EFS12

Failing to achieve EFS12 was associated with significantly increased mortality based on rates from the age and sex matched general population (MER SMR = 3.72, 95% CI, 2.78–4.88, p<0.0001; Lyon SMR = 8.74, 95% CI, 5.41–13.36, p<0.0001, Figure 1A, Supplemental Table 1). The highest excess mortality was in immunochemotherapy treated patients (MER SMR = 17.63, 95% CI, 11.97–25.02, p<0.0001; Lyon SMR = 19.10, 95% CI, 9.86–33.36, p<0.0001, Figure 1B), and in patients 60 years or younger (MER SMR = 9.58, 95% CI, 6.20–14.15, p<0.0001; Lyon SMR = 12.33, 95% CI, 6.37–21.54, p<0.0001, Figure 1E). Excess mortality was observed in patients failing to achieve EFS12 in all treatment subgroups, although the observed number of deaths in these subsets, including rituximab monotherapy was small. Full details by initial treatment and subgroup can be found in Supplemental Table 1 and Figure 1.

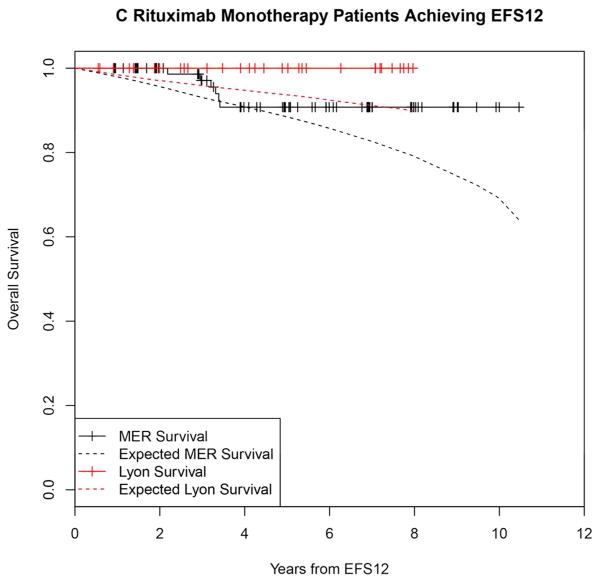

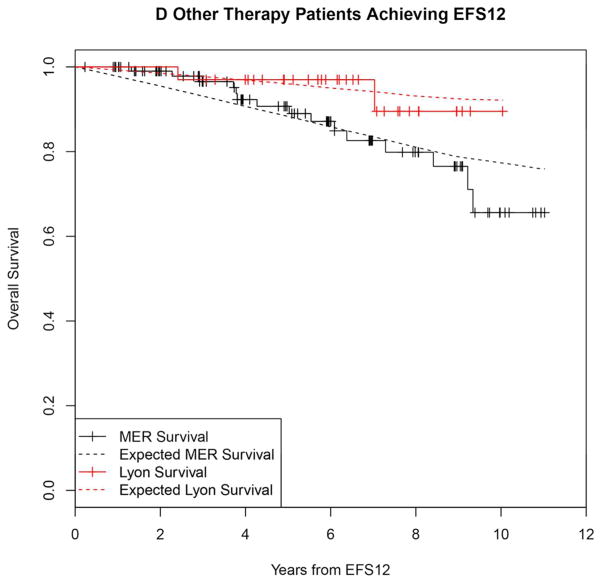

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of subsequent overall survival after event in FL patients failing to achieve EFS12 (black=MER, red=Lyon) with expected survival in the age and sex matched general population (black dashed=MER/US, red dashed=Lyon/France); A: All patients, B: Immunochemotherapy treated patients, C: Rituximab monotherapy treated, D: Other therapy treated, E: Younger patients (Age <=60) F: Older patients.

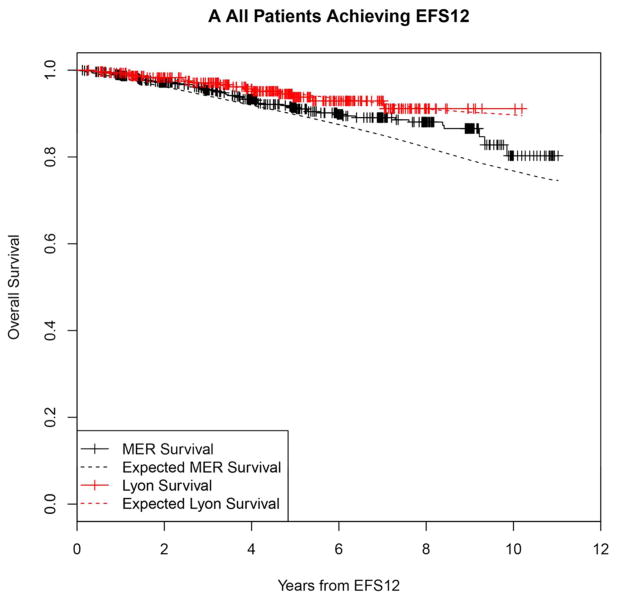

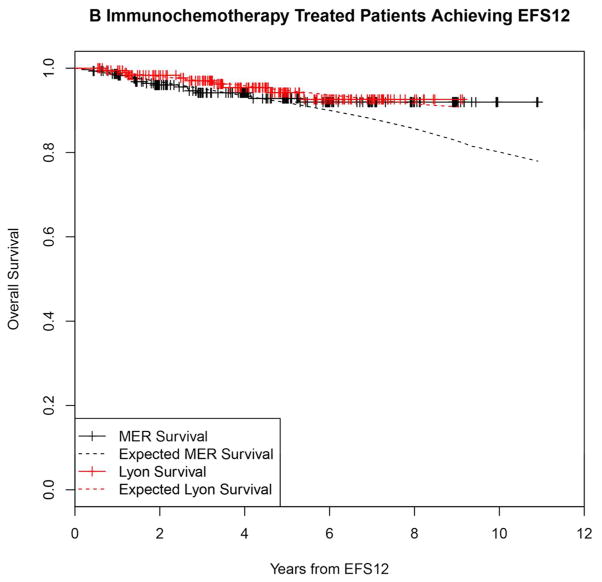

Outcomes after achieving EFS12

In contrast, patients achieving EFS12 had an excellent subsequent outcome, with no observed excess mortality beyond the age and sex matched general population (MER SMR = 0.73, 95% CI, 0.56–0.94, p=0.016; Lyon SMR = 1.02, 95% CI, 0.58–1.65, p=0.95, Figure 2A, Supplemental Table 2). Notably, excellent outcome was even observed in immunochemotherapy treated patients (MER SMR = 0.74, 95% CI, 0.43–1.15, p=0.22; Lyon SMR = 1.03, 95% CI, 0.47–1.96, p=0.99, Figure 2B). Again, this result was consistent across patient subgroups with the caveat of small observed numbers of deaths in some subsets. Full details by initial treatment and subgroup can be found in Supplemental Table 2 and Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of subsequent overall survival after achieving EFS12 in FL patients (black=MER, red=Lyon) with expected survival in the age and sex matched general population (black dashed=MER/US, red dashed=Lyon/France); A: All patients, B: Immunochemotherapy treated patients, C: Rituximab monotherapy treated, D:Other therapy treated, E: Younger patients (Age <=60) F: Older patients.

Significance of EFS12 vs. EFS24 in patients initially treated with immunochemotherapy

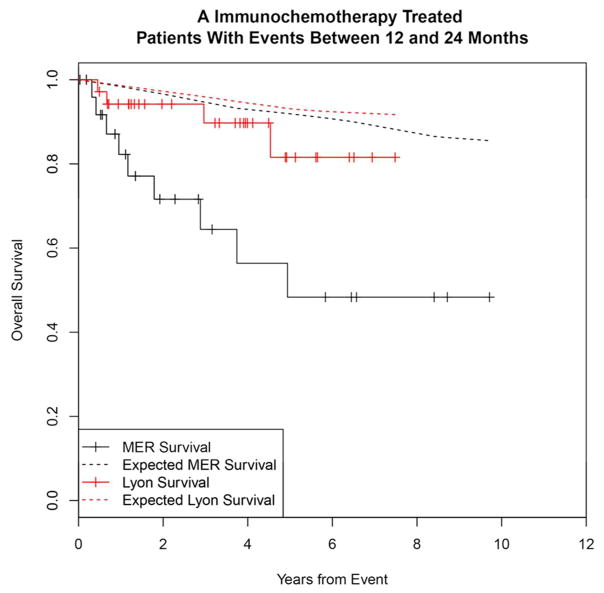

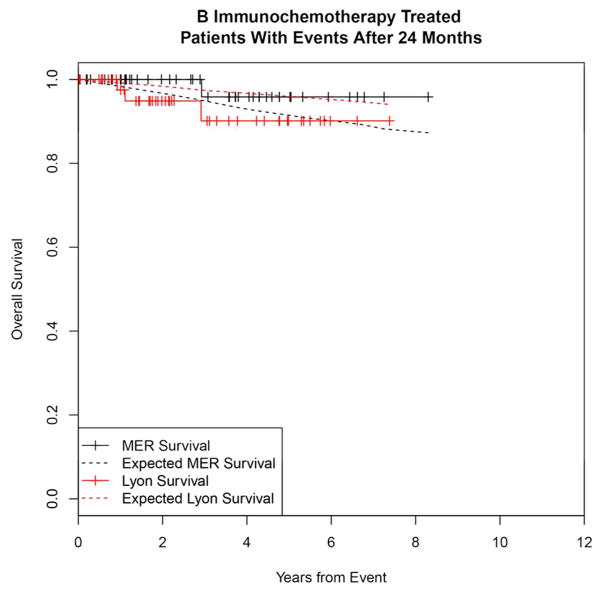

To contrast the significance of early vs. late events and determine the utility of EFS12 vs EFS24 in immunochemotherapy treated patients, we examined outcomes in patients with events occurring after 12 months. Events occurring between 13 and 24 months were more common in the Lyon cohort (14%) than the MER (8%); outcomes were mixed with MER survival more similar to patients with events in the first 12 months, while Lyon patients had better outcomes approaching the background population mortality (Figure 3A). Patients who had a first event beyond than 24 months from diagnosis had good subsequent prognosis after event in both the MER and Lyon cohorts, Figure 3B). Similar to EFS12, failing to achieve EFS24 was associated with significantly increased mortality based on rates from the age and sex matched general population (MER SMR = 13.02, 95% CI, 9.31–17.74, p<0.0001; Lyon SMR = 7.22, 95% CI, 4.13–11.74, p<0.0001, Supplemental Figure 2A), while patients achieving EFS24 had an excellent subsequent outcome (MER SMR = 0.37, 95% CI, 0.18–0.78, p=0.0086; Lyon SMR = 0.90, 95% CI, 0.38–2.17, p=0.82, Supplemental Figure 2B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve of subsequent overall survival in immunochemotherapy treated FL patients (black=MER, red=Lyon) with expected survival in the age and sex matched general population (black dashed=MER/US, red dashed=Lyon/France); A: Survival after event in patients with events between 12 and 24 months, B: Survival after event in patients with events after 24 months.

Outcomes by FLIPI after EFS12 assessment

At diagnosis, baseline FLIPI was prognostic for overall survival in the combined MER + Lyon dataset (FLIPI 2 vs. FLIPI 0–1 HR = 2.34, 95% CI, 1.51–3.62, p=0.0001; FLIPI 3–5 vs. FLIPI 0–1 HR = 3.53, 95% CI, 2.30–5.42, p<0.0001). After accounting for age and sex, the baseline FLIPI was no longer prognostic for survival in EFS12 achievers (FLIPI 2 vs. FLIPI 0–1 HR = 1.21, 95% CI, 0.66–2.23, p=0.53; FLIPI 3–5 vs. FLIPI 0–1 HR = 1.49, 95% CI, 0.82–2.72, p=0.15, Supplemental Figure 3A). Notably, the observed mortality in patients with high (3–5) risk FLIPI at baseline who achieved EFS12 was not significantly greater than the age and sex matched general population (MER SMR = 0.85, 95%CI, 0.53–1.28, p=0.50; Lyon SMR = 1.30, 95% CI, 0.52–2.67, p=0.59, Supplemental Figure 3B, Supplemental Table 2).

Outcomes in patients initially observed

Patients who failed EFS12 during observation had modest increase in mortality compared to the general population (MER SMR = 1.44, 95% CI, 0.72–2.57, p=0.30; Lyon SMR = 4.61, 95% CI, 0.52–16.65, p=0.14, Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Figure 4A) while patients who achieved EFS12 after initial management of observation had excellent subsequent prognosis (MER SMR = 0.70, 95% CI, 0.44–1.05, p=0.10; Lyon SMR = 1.47, 95% CI, 0.48–3.44, p=0.51, Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Figure 4B). In an a exploratory analysis we also examined outcomes in the 127 MER patients (39%) that were initially managed with observation and went on to initiate treatment during the follow-up period of the study. Outcomes by “secondary EFS12” status after the initiation of therapy in this group of patients were similar to outcomes by EFS12 in patients who received therapy at initial diagnosis (Supplemental Figure 4C–4F). Further details can be found in the supplemental materials.

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive evaluation of relative survival from landmark timepoints of event status in a population of patients with FL diagnosed and managed in the rituximab/immunochemotherapy era. We used a population-based approach that we had previously applied to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma19 to identify the time point of 12 months in follicular lymphoma and we identify that reassessment of patient status 12–24 months after diagnosis to be a powerful prognostic tool in follicular lymphoma – superseding baseline FLIPI score. Most treatment decisions in the lifetime of FL patients are made after the initial diagnosis and management plan. These results provide support for the re-assessment and updating of prognosis in FL patients at time points subsequent to diagnosis. Importantly, baseline FLIPI scores, which are powerful predictors of OS at diagnosis, no longer identify a subset of patients with increased mortality in the group of FL patients achieving EFS12. The current analysis further identifies that after 12 months free of events following initial management, follicular patients managed with different treatment strategies have survival comparable to expected rates based on the age and sex matched general population.

We confirm and extend previous observations that early events following initial immunochemotherapy identify a subset of patients who are at high risk for early mortality. Casulo et al. reported from the National LymphoCare Study with replication in this dataset that FL patients developing an event within 24 months of diagnosis after initial treatment with R-CHOP and R-CVP had inferior survival18. Immunochemotherapy-treated patients who have an event in months 12–24 had added mortality in the MER (SMR=6.86), though these events were relatively infrequent (8% of IC treated patients). While more common in the Lyon cohort (14%), the outcome in patients after events between 12 and 24 months was better than the MER, though still demonstrating some excess mortality above the background population. These results support the use of EFS24 as the definition of early event in IC treated FL. Importantly, we show that IC treated patients who relapse after 24 months had excellent outcomes during the follow-up period – further highlighting the clinical importance of early vs. late events in these patients.

This analysis also extends the observations by Casulo et al. to include the significance of early events after non-aggressive initial management, with the finding that an early event following rituximab monotherapy or after initiation of treatment following observation predicts poor subsequent survival. These results are based on smaller numbers of patients and should be validated in larger datasets, but also suggest the need for improved therapeutic options for patients with early events following any initial therapy.

This study design and execution offer many strengths for an observational study including the prospective cohort design of consecutively enrolled, newly diagnosed lymphoma patients; central pathology review; systematically collected clinical data; virtually complete follow-up of the cohort for disease progression, transformation, and death; and medical record validation of these events. All patients were managed in the rituximab treatment era. Validation with the population of French patients reduces the likelihood that these findings are serendipitous or unique to the US population, therapy regimens, or healthcare system. Limitations include modest follow-up (median of 71 months), which is insufficient to exclude impact of FL-related mortality in the second or subsequent decade following diagnosis, which cannot yet be addressed for the rituximab era. Although scan-based progression-free survival is the desired endpoint in prospective clinical trials comparing finite management options and is effective when there is controlled scheduling of progression assessment, including the clinical management of retreatment as an event in our EFS definition has the advantage in observational studies with uncontrolled and non-centralized progression surveillance. Finally, these results are in the setting of initial therapy; additional studies will be needed to assess how early relapse in second and subsequent lines of therapies informs prognosis.

There are several important implications from these findings. Patients afflicted with an incurable malignancy commonly fear the risk of death related to disease or treatment. These data should provide moderate reassurance in that regard to patients who achieve EFS12, though reassessment after 24 months from diagnosis provides more prognostic clarity for immunochemotherapy treated patients. For the treating physician, the refinement of prognosis based on presence or absence of events in the first 12 months (all patients) and 24 months (immunochemotherapy treated) from diagnosis may be used to inform subsequent management, treatment strategies, follow-up strategies including radiologic studies, and patient counseling. From the perspective of clinical and bench research, these insights provide an approach for utilizing early endpoints when assessing outcomes in FL. These results also strengthen the argument that the greatest need for new management strategies in FL lies in patients with early events following immunochemotherapy. For public health officials across various health delivery systems, these findings may provide important insights on utilization of clinical trials and newer and more expensive therapeutic interventions for patients whose outcome with available strategies might already be adequate.

In conclusion patient status 12 months after diagnosis via EFS12 is a strong prognostic indicator in follicular lymphoma overall, although EFS24 should be considered in patients initially treated with immunochemotherapy. Prognostic reassessment after early event status reveals that those who are event-free have an excellent prognosis, independent of initial prognostic indices or management strategies, while patients with early events have inferior subsequent survival, especially in patients initially treated with immunochemotherapy. Early event status as defined by EFS12 (non-aggressive therapy) and EFS24 (immunochemotherapy) can provide a simple endpoint for outcome in FL that does not require extended follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma SPORE (CA97274) and the Predolin Foundation

The authors thank Dr. Pierre Biron, Department of Onco-Hematology, and Thérèse Gargi, Statistics, for contributing to the Centre Leon Berard data and Katelyn Cordie, Mayo Clinic, for editorial assistance.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant No. P50 CA97274 to the University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Specialized Program of Research Excellence, and the Henry J. Predolin Foundation.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 56th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 6–9, 2014, and the 13th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma June 17–20, 2015, Lugano, Switzerland.

Declaration of Interests

We declare no competing financial interests.

Contribution: MJM, JRC, and BKL conceived and designed the study; JRC provided financial support; HG, SMA, EB, GSN, CAT, DI, CCC, ENV, CS, LL, CS, WRM, AF, SIS, ATG, BC, TEW, TMH, GS, JRC, and BKL provided study material or patients; MJM, HG, EB, CA, SLS, GS, JRC, and BKL collected and assembled the data; MJM, HG, SMA, EB, CA, SLS, TEW, TMH, GS, JRC, and BKL analyzed and interpreted the data; MJM, JRC, and BKL wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Weisenburger DD, Linet MS. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992–2001. Blood. 2006;107(1):265–276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Tourah AJ, Gill KK, Chhanabhai M, et al. Population-based analysis of incidence and outcome of transformed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5165–5169. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Link BK, Maurer MJ, Nowakowski GS, et al. Rates and outcomes of follicular lymphoma transformation in the immunochemotherapy era: a report from the University of Iowa/MayoClinic Specialized Program of Research Excellence Molecular Epidemiology Resource. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3272–3278. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3990. Prepublished on 2013/07/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ban-Hoefen M, Vanderplas A, Crosby-Thompson AL, et al. Transformed non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the rituximab era: analysis of the NCCN outcomes database. Br J Haematol. 2013;163(4):487–495. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12570. Prepublished on 2013/10/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochster H, Weller E, Gascoyne RD, et al. Maintenance Rituximab After Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, and Prednisone Prolongs Progression-Free Survival in Advanced Indolent Lymphoma: Results of the Randomized Phase III ECOG1496 Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(10):1607–1614. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.17.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A, et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105(4):1417–1423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salles G, Mounier N, de Guibert S, et al. Rituximab combined with chemotherapy and interferon in follicular lymphoma patients: results of the GELA-GOELAMS FL2000 study. Blood. 2008;112(13):4824–4831. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: …. Blood. 2005;106(12):3725–3732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herold M, Haas A, Srock S, et al. Rituximab Added to First-Line Mitoxantrone, Chlorambucil, and Prednisolone Chemotherapy Followed by Interferon Maintenance Prolongs Survival in Patients With Advanced Follicular Lymphoma: An East German Study Group Hematology and Oncology Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(15):1986–1992. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.06.4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keegan THM, McClure LA, Foran JM, Clarke CA. Improvements in Survival After Follicular Lymphoma by Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status: A Population-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(18):3044–3051. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.18.8052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Q, Fayad L, Cabanillas F, et al. Improvement of overall and failure-free survival in stage IV follicular lymphoma: 25 years of treatment experience at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(10):1582–1589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3696. Prepublished on 2006/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher RI, LeBlanc M, Press OW, Maloney DG, Unger JM, Miller TP. New Treatment Options Have Changed the Survival of Patients With Follicular Lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(33):8447–8452. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.03.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan D, Horning SJ, Hoppe RT, et al. Improvements in observed and relative survival in follicular grade 1–2 lymphoma during 4 decades: the Stanford University experience. Blood. 2013;122(6):981–987. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-491514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nooka AK, Nabhan C, Zhou X, et al. Examination of the follicular lymphoma international prognostic index (FLIPI) in the National LymphoCare study (NLCS): a prospective US patient cohort treated predominantly in community practices. Annals of Oncology. 2013;24(2):441–448. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds429. Prepublished on 2012/10/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al. Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index. Blood. 2004;104(5):1258–1265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trotman J, Luminari S, Boussetta S, et al. Prognostic value of PET-CT after first-line therpay in patients with follicular lymphonma: a pooled analysis of central scan review in three multicentre studies. Lancet Haematol. 2014;1:e17–27. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(14)70008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sargent Daniel J, Shi Qian, DeBedout Sabine, et al. Evaluation of complete response rate at 30 months (CR30) as a surrogate for progression-free survival (PFS) in first-line follicular lymphoma (FL) studies: Results from the prospectively specified Follicular Lymphoma Analysis of Surrogacy Hypothesis (FLASH) analysis with individual patient data (IPD) of 3,837 patients (pts) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl) abstr 8504. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, et al. Early Relapse of Follicular Lymphoma After Rituximab Plus Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone Defines Patients at High Risk for Death: An Analysis From the National LymphoCare Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(23):2516–2522. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.59.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurer MJ, Ghesquières H, Jais J-P, et al. Event-Free Survival at 24 Months Is a Robust End Point for Disease-Related Outcome in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Treated With Immunochemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(10):1066–1073. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.51.5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowakowski GS, Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, et al. Statin use and prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):412–417. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4245. Prepublished on 2009/12/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drake MT, Maurer MJ, Link BK, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency and prognosis in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4191–4198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolas-Virelizier E, Segura-Ferlay C, Ghesquieres H, et al. Impact of the introduction of rituximab in first-line follicular lymphoma: a retrospective study of 247 unselected patients referred to a single institution with a long-term follow-up. Hematological Oncology. 2015;33(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/hon.2130. Prepublished on 2014/02/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Therneau TM. A Package for Survival Analysis in S. version 2.38. 2015 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival. (ed version 2.38)

- 24.Jais J-P, Varet H. Survexp.fr: Relative survival, AER and SMR based on French death rates (R package version 1.0) 2013 http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survexp.fr/index.html.

- 25.Therneau T, Sicks J, Bergstralh EJO. Technical Report Series No. 52, Expected Survival Based on Hazard Rates. Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic; Rochester, Minnesota: Mar, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: Extending the Cox model. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verheul HA, Dekker E, Bossuyt P, Moulijn AC, Dunning AJ. Background mortality in clinical survival studies. Lancet. 1993;341(8849):872–875. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93073-a. Prepublished on 1993/04/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breslow NE, Lubin JH, Marek P, Langholz B. Multiplicative models and cohort analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78(381):1–12. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.