Abstract

Recent advancements in PET instrumentation have made the non-invasive assessment of cardiovascular function in small animals a reality. The majority of small animal PET systems use stationary detector gantries, thus affording high temporal resolution imaging of cardiac function. Systems designed to maximize spatial resolution and detection sensitivity employing rotating gantry designs are suboptimal when high temporal resolution imaging is needed. To overcome this limitation, the current work developed a novel view-sharing data analysis scheme suitable for dynamic cardiac PET imaging using 18F-NaF as the tracer and tracer kinetic model analysis. This scheme was tested in a rat model of cardiovascular function where the relationship between direct transonic flow measures of cardiac output were highly correlated (f(x) = 1.0216x − 24.233, R = 0.9158, p < 0.001) with the new model. Similarly, derived measures of stroke volume were also highly correlated (f(x) = 0.9655x − 0.0428, R = 0.9453, p < 0.001) with the current approach. Administration of xylazine caused a statistically significant increase in stroke volume (0.32 ± 0.07 ml, p = 0.003, n = 4) and a significant decrease in both heart rate (−155 ± 7.1 beats/min, p < 0.001, n = 4) and cardiac output (−75.9 ± 23.0 ml/kg min, p = 0.01, n = 4). These findings suggest that the new sinogram binning and kinetic modeling methods produce reliable cardiac function measures suitable for longitudinal monitoring of cardiovascular function.

Keywords: Cardiac output, PET, View-sharing, Kinetic modeling

Introduction

Determination of cardiovascular function in small animals has been well characterized using a number of in vivo model systems. In particular, the application of the direct Fick principle [1], employing electromagnetic flow meters [2], indicator dilution [3], and thermal [4] dilution methods have been used with great success. The invasive nature of these techniques makes them better suited for acute rather than longitudinal measurements of function. To overcome this limitation, non-invasive small animal quantitative PET methods have been developed for both rats [5–10] and mice [11]. Primary challenges in quantifying cardiac function via small animal PET include limited spatial resolution and suboptimal detection sensitivity of these devices. Currently, a majority of the small animal PET scanners in use have a fixed ring geometry and yield a spatial resolution at the center of the field of view (CFOV) in the range of 1.3–1.7 mm full width at half-maximum (FWHM) and a overall system sensitivity of 3–5 % [7, 12–14]. Kreissl et al. [11] acquired cardiac PET data in listmode and reconstructed the images into short-duration frames (0.3 s/frame) in order to measure the first pass kinetics of the radiotracer through the heart. In order to gain greater spatial resolution and system sensitivity, small animal PET scanners, like IndyPET3, have been developed with a slip-ring geometry which encodes all events spatially as the gantry rotates in order to increase spatial sampling by using 12 coincidence banks, thus yielding resolution at CFOV of <1 mm while simultaneously maximizing sensitivity (>7 %) with long detector crystal lengths [15]. Although these advances provide substantial benefit for cardiac PET imaging, the use of high temporal resolution frame rates [11] with a rotating gantry configuration will eliminate the resolution gain provided by the unique spatial sampling schemes employed in these systems. The objective of the current study was to develop a novel sinogram binning and data processing scheme that enables rapid cardiac function studies to be performed while maintaining the improved spatial resolution produced by small animal PET systems that incorporate a rotating gantry. To test this approach, we developed an animal model that enabled simultaneous measurement of cardiac function with a transonic flow meter and PET determination of function using tracer kinetic models which utilizes the sinogram binning.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

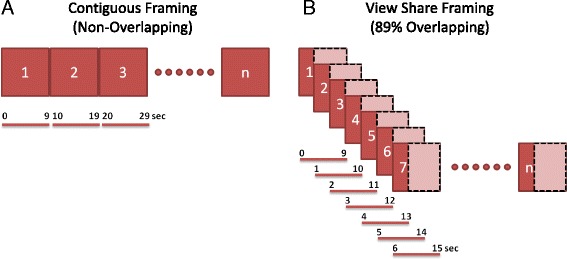

All procedures were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee prior to the start of the study and were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines on animal care and use [16]. Four adult Sprague-Dawley male rats were anesthetized using isoflurane (3–4 % isoflurane), balanced with medial grade oxygen at a flow rate of 2 l/h. Once anesthetized, animals were placed on custom carbon fiber bed and maintained at 1.5–2 % isoflurane during surgical preparation of the abdomen. A small incision was made over the midline, the skin retracted, and abdominal contents displaced laterally and sterile saline soaked gauze was placed over contents to ensure hydration. Using blunt dissection, the abdominal aorta was isolated from the surrounding nerve and vena cava, and a transonic flow probe (TFP;Transonic, Model # PRB3313) was placed as described previously [2, 17]. Abdominal contents were replaced into the cavity and the skin was closed. Animals were quickly transported to the imaging suite and positioned for the imaging studies (imaging bed mounted, flow probe, and ECG leads connected). Isoflurane (1–3 % isoflurane) anesthesia was maintained for the duration of the imaging session. Venous access was secured via tail vein catheterization, and baseline readings of cardiac output and heart rate were collected in triplicate. Immediately after starting PET data acquisition, animals were delivered a dose of 18F-NaF (14.8 ± 0.48 MBq/kg, n = 4) IV, followed by repeat collection of heart rate and cardiac output measurements in triplicate. 18F-NaF was selected due to its rapid vascular clearance (facilitated by hydroxyapatite binding in the bone), minimizing the cross-talk between the repeat 18F-NaF dose administrations. In all cases, dynamic PET images were acquired in listmode using the IndyPET3 scanner [18] with a gantry rotation rate of 3 rpm. With this configuration, a minimum rotation angle of 60°, which requires minimum scan duration (MSD) of 3.33 s, is required for acquisition of a uniformly sampled data set suitable for sorting into a high-resolution sinogram and application of analytical image reconstruction algorithms. Following the baseline scan, cardiac output was manipulated by administering the α2-agonist xylazine via constant rate infusion at 13.8 mg/kg min [19]. Once at steady state, animals were administered a second dose of 18F-NaF (15.5 ± 0.1.7 MBq/kg, n = 4) IV, followed by repeat collection of cardiac output and heart rate in triplicate. Dynamic listmode data (15 min/treatment) were reconstructed into 80 × 100 mm volumes using filtered back projection (FBP). In order to maintain the high intrinsic spatial resolution of the IndyPET3 system, with signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) yielding acceptable image quality, while capturing rapid tracer kinetic changes in the cardiac LV chamber, listmode data were binned using a temporal overlap design with 9 s (3*MSD) duration frames offset by 1 s. Using this schema, frames 1, 2, 3, through “n” would yield the following [start, stop] frame integration times: [0, 8], [1, 9], [2, 10], and [n, n + 8], respectively. The result is a 4D series with 89 % view-sharing per frame (see Fig. 1). In all cases, images were corrected for decay, random coincidence events, and dead-time loss [20]. Animal beds were transferred to the EVS R9 microCT, and images were acquired center over the heart using 80 kVp, 1000 mA, 200 ms/°, 1.08°/step, and reconstructed into an 40 × 65 mm volumes using vendor-supplied FBP reconstruction algorithm.

Fig. 1.

Visual representations of ultra-short contiguous (non-overlapping) frame reconstruction [11] (a) and view-sharing (89 % overlapping) frame reconstruction (b) used with stationary and rotating gantry PET systems, respectively

Image analysis

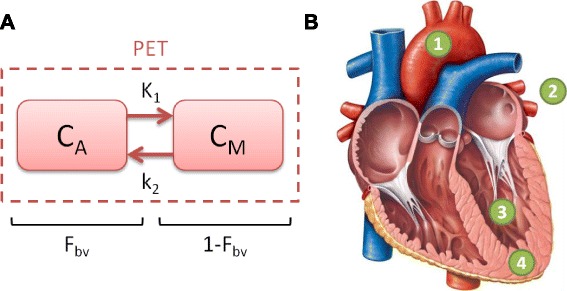

PET and CT images were imported, reoriented, and registered using a normalized entropy algorithm [21]. Using registered CT images, the left ventricular cavities were manually segmented avoiding the apex, septum, and free walls to limit the ventricular spillover. Regions of interest were then extracted from the PET time series, and a tracer kinetic model describing 18F-NaF kinetics in LV blood and myocardial tissue (Fig. 2a) was fit to the data. The 18F-NaF concentration measured in the LV VOI was described by the following equation.

| 1 |

Fig. 2.

a Schematic diagram of the 1 compartment 3 parameter tracer kinetic model. b Heart diagram indicating the points of reference as described in Eqns. 1–6 (reproduced with permission from Pearson Education Inc.)

where C PET(t(i)) is the measured 18F-NaF concentration in the LV VOI, C M(t(i)) is the myocardial tissue 18F-NaF concentration (Fig. 2b. marker 4, Eq. 5), C A(t(i)) is the arterial blood 18F-NaF concentration (Fig. 2b. marker 1, Eqs. 2, 3, and 4), F bv, is the fractional blood volume, and “i” represents the temporal frame number, respectively. The pulmonary artery C PA(t) (Fig. 2b. marker 2, Eq. 3) input to the LV and the LV response function (LVrf(t)) (Fig. 2b. marker 3, Eq. 4) determine the arterial blood concentration (Eq. 2)

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

where A, t 0, σ, , SV, fh, Vlv, K1, and k2 are the input amplitude, time offset, input width, total cardiac output (ml/g min), stroke volume (ml), heart rate (beats/min), left ventricular volume (ml), tissue perfusion times extraction fraction (ml/g min), and back flux rate constant (1/min), respectively. For Eqs. 2 and 5, ⊗ represents the convolution operator. As indicated in Eq. 1, each image frame (i) is constructed by integrating over the interval [t 1(i), t 2(i)]. For this study, t 2(i) = t 1(i) + 8.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed on direct measures of TFP and tracer kinetic model estimates of stroke volume (SV) and cardiac output (CO) parameters, where heart rates (HR) were collected simultaneously for both measures. Correlation analysis was performed on all measures of SV and CO using Pearson-product moment correlation analysis. Statistical analysis was performed as two-tailed paired T test pre- and post xylazine in fusion, where significance (*) was taken at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

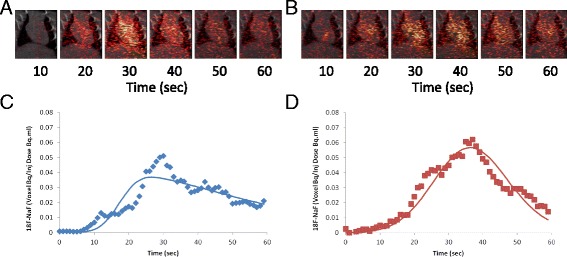

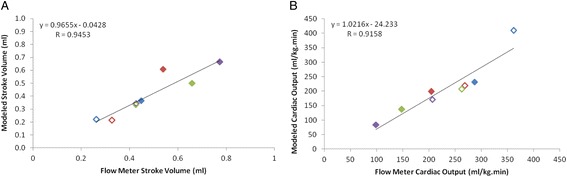

Images acquired over the first 60-s post 18F-NaF administration and reconstructed using the 89 % temporal view-sharing scheme, as described in Fig. 1, are shown in Fig. 3a-b. Segmentation of the PET/CT images produced dose normalized TACs consistent with the baseline and xylazine treatments (see Fig. 3c, d). These time courses when fit with the kinetic model described by Eqs. 1–6 yielded estimates of the left ventricular SV and total CO at baseline and following xylazine administration. To determine the relationship between the TFP measures and PET kinetically derived parameters, correlation analysis was performed for SV (Fig. 4a) and CO (Fig. 4b). The relationship between TFM measurements and PET estimated SV can be described by f(x) = 0.9655x − 0.0428, with a correlation coefficient of R = 0.9453 (p < 0.001, n = 4, groups = 2). Similarly, the correlation coefficient between TFM measurements and PET estimates was R = 0.9158 (p < 0.001, n = 4, groups = 2) and can be described by f(x) = 1.0216x − 24.233. When analyzed by treatment, SV significantly increased from 0.30 ± 0.05 ml to 0.62 ± 0.06 ml (p = 0.003, n = 4, groups = 2) when measured via TFM, while PET estimates yielded a similar increase from 0.30 ± 0.04 ml to 0.54 ± 0.04 ml (p = 0.003, n = 4, groups = 2). As expected, the infusion of xylazine resulted in a significant decrease in CO by (75.9 ± 23.0 ml/kg min (p = 0.017, n = 4, groups = 2) as measured by TFM, with PET showing a similar reduction over this same interval 84.1 ± 18.1 ml/kg min (p = 0.007, n = 4, groups = 2). Concomitantly, HR over this same interval decreased by 155 ± 7.1 beats/min (p < 0.001, n = 4, groups = 2)

Fig. 3.

Fused 18F-NaF PET/CT view-sharing reconstructed images with time of the heart prior to (a) and post (b)-xylazine infusion at 13.8 mg/kg min, where the corresponding kinetic time courses pre (c) and post (d) are shown below each image series, where solid line represent the fit of the described model. Reconstructions utilized a 9-s frame duration with a 1 s offset as described in Fig. 1

Fig. 4.

Comparison of flow meter and tracer kinetically modeled a stroke volume and b cardiac output at baseline and postxylazine infusion at 13.8 mg/kg min [19]. The equation in each chart represents the linear relationship between the measures, while the measure of fit is provided by the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (R). In all cases, unique colors represent individual animals at baseline (open symbols) and post xylazine (filled symbols) treatment

Discussion

Over the past decade, there is an emerging interest in dynamic cardiac PET as a tool to assess small animal cardiovascular function [5–11]. Spatial and temporal resolution presents a key challenge for quantifying cardiac function in rodents. Currently, the majority of the small animal PET scanners rely on a fixed ring geometry which yields a spatial resolution at CFOV of 1.3–1.7 mm FWHM and an overall system sensitivity of 3–5 % [7, 12–14]. Taking advantage of this fixed geometry, Kreissl et al. [11] acquired cardiac PET data in listmode and reconstructed these into short frame durations (0.3 s/frame), thereby permitting quantification of the first pass of the radiotracer through the heart. An important consideration of fixed ring geometry systems is that they cannot achieve the inherent spatial resolution of the PET detectors when employing traditional FBP algorithms due to limited spatial sampling constraints. Advancement in scanner design which employ a slip-ring geometry along with spatial encoding of events as the gantry rotates, resulting in resolution and sensitivity at CFOV of <1 mm and >7 % [15], respectively. These advances provide substantial benefit for small animal cardiac PET imaging; however, the use of high temporal resolution PET techniques as previously described [11] (i.e., 0.3 s/frame) will sacrifice the spatial resolution gain achieved through the rotating gantry design. Therefore, the current study builds upon the prior advancements in instrumentation and reconstruction [11] approaches and develops a novel view-sharing sinogram binning scheme that provides high temporal sampling of images for rotating gantry PET systems and while maintaining the spatial resolution advantages of a rotating gantry design.

This novel sinogram binning approach when used with listmode acquisitions provides high temporal resolution by overlapping the image frames, where the image projection content is a fixed proportion from prior and newly acquired projection data (Fig. 1b). Although this overlapping scheme permits high temporal resolution while maintaining high spatial resolution, the resulting image frames can be described as the convolution of the image series with a boxcar function specified by the overlap length. This resulting tissue VOIs curves are fit with a tracer kinetic model (Eqs. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6) using integration limits [t 1(i), t 2(i)] that are consistent with the data binning process. To test this reconstruction and analysis approach, we developed an animal model that enabled PET-based cardiac function estimates to be validated against a transonic flow meter. Estimates of SV and CO prior to and postxylazine infusion could be reliably estimated using the view-sharing PET methodology, as demonstrated by the strong correlation with the TFP measurements (Table 1). Our results were consistent with prior literature reports using the direct Fick method [1], thermal/indicator dilution [3, 4], and TFM [2] measures.

Table 1.

Tracer kinetic modeling statistics prior to and post xylazine. Data are presented as mean ± SEM

| Group | K1 (ml/g.min) | SEM | k2 (1/min) | SEM | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3.67 | 1.16 | 0.975 | 0.597 | 4 |

| Xylazine | 6.45 | 2.84 | 1.431 | 0.576 | 4 |

These data show for the first time that high temporal sampling of PET images, view-sharing sinogram binning scheme, and tracer kinetic analysis of PET series are feasible for monitoring dynamic cardiac functional changes in a rotating gantry PET scanner. Moreover, we demonstrated that over a broad range in SV and CO changes, the current method provides a rapid assessment of the heart function not previously possible with rotating gantry PET scanners. When coupled to a scanner with high sensitivity and spatial resolution [15], this approach provides a key opportunity to leverage the system features along with high temporal resolution imaging for assessment of cardiovascular function in small animals.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Dr. David Basile for the use of the transonic probe and meter. In addition, the authors would like to thank Pearson Education Inc. for permission to reproduce and annotate the heart diagram.

Funding

This study was funded in part by Indiana Institute for Biomedical Imaging Sciences Advanced Imaging Research Technology Development (AIRTD) grant to PRT. In addition, this work was partially supported by NIH/NCI grant R01CA202695.

Authors’ contributions

PRT conceived of the sliding-window sinogram binning, designed and oversaw the live phase conduct of the studies, co-developed the tracer kinetic models with GDH, and analyzed the tracer kinetic modeling with AAR. AAR developed the surgical model, conducted the live phase in collaboration with BRP and assisted PRT with the data analysis. BRP performed instrument calibrations, assisted AAR with the live phase, developed the listmode sorting scheme for sliding-window sinogram binning, and performed all the image reconstructions. GDH in collaboration with PRT developed the tracer kinetic modeling and implemented this into a software package for routine use by PRT and AAR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed as outlined in the “Materials and methods” section.

References

- 1.Walsh GM, Tsuchiya M, Frohlich ED. Direct Fick application for measurement of cardiac output in rat. J Appl Physiol. 1976;40:849–53. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.40.5.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen C, Li M, Whitworth JA. Validation of transonic small animal flowmeter for measurement of cardiac output and regional blood flow in the rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;27:482–6. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Profant M, Vyska K, Eckhardt U. The Stewart-Hamilton equations and the indicator dilution method. SIAM J Appl Math. 1978;34:666–75. doi: 10.1137/0134053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kissling G, Ross C, Brandle M. Validity of thermal dilution technique for measurement of cardiac output in rats. Am J Phys. 1993;265:H1007–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.3.H1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croteau E, Benard F, Bentourkia M, Rousseau J, Paquette M, Lecomte R. Quantitative myocardial perfusion and coronary reserve in rats with 13 N-ammonia and small animal PET: impact of anesthesia and pharmacologic stress agents. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1924–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croteau E, Benard F, Cadorette J, Gauthier ME, Aliaga A, Bentourkia M, et al. Quantitative gated PET for the assessment of left ventricular function in small animals. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2003;44:1655–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahey FH, Gage HD, Buchheimer N, Smith HC, Harkness BA, Williams RC, et al. Evaluation of the quantitative capability of a high-resolution positron emission tomography scanner for small animal imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:842–8. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200411000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inubushi M, Wu JC, Gambhir SS, Sundaresan G, Satyamurthy N, Namavari M, et al. Positron-emission tomography reporter gene expression imaging in rat myocardium. Circulation. 2003;107:326–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000044385.60972.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen L, Gambhir SS, Furukawa H, Stout DB, Linh Lam A, Laks H, et al. Noninvasive imaging of ex vivo intracoronarily delivered nonviral therapeutic transgene expression in heart. Mol Ther. 2005;12:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu JC, Inubushi M, Sundaresan G, Schelbert HR, Gambhir SS. Positron emission tomography imaging of cardiac reporter gene expression in living rats. Circulation. 2002;106:180–3. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000023620.59633.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreissl MC, Wu HM, Stout DB, Ladno W, Schindler TH, Zhang X, et al. Noninvasive measurement of cardiovascular function in mice with high-temporal-resolution small-animal PET. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2006;47:974–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tai YC, Ruangma A, Rowland D, Siegel S, Newport DF, Chow PL, et al. Performance evaluation of the microPET focus: a third-generation microPET scanner dedicated to animal imaging. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46:455–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schug D, Lerche C, Weissler B, Gebhardt P, Goldschmidt B, Wehner J, et al. Initial PET performance evaluation of a preclinical insert for PET/MRI with digital SiPM technology. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61:2851–78. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/7/2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato K, Shidahara M, Watabe H, Watanuki S, Ishikawa Y, Arakawa Y, et al. Performance evaluation of the small-animal PET scanner ClairvivoPET using NEMA NU 4-2008 standards. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61:696–711. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/2/696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rouze NC, Schmand M, Siegel S, Hutchins GD. Design of a small animal PET imaging system with 1 microliter volume resolution. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2004;51:757–63. doi: 10.1109/TNS.2004.829738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resources ILA. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. 8. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinemann A, Wachter CH, Holzer P. Differential regulation of mesenteric and femoral blood flow in the rat as revealed by computerized data acquisition and evaluation. J Auton Pharmacol. 1998;18:39–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2680.1998.1810039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchins GD, Miller MA, Soon VC, Receveur T. Small animal PET imaging. ILAR J. 2008;49:54–65. doi: 10.1093/ilar.49.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiley CR, Thomas GR. Effects of alpha-adrenoceptor agonists on cardiac output and its regional distribution in the pithed rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1987;90:61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb16825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soon VC, Miller LM, Hutchins GD. A non-iterative method for emission tomographic image reconstruction with resolution recovery. IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record. 2007;5(8):3468–73.

- 21.Studholme C, Hawkes DJ, Hill DLG. A normalized entropy measure for multimodality image alignment. Proc SPIE Med Imaging. 1998;3338:132–43. doi: 10.1117/12.310835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]